Abstract Interest Management Middleware for Networked Games

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:279.12 KB

- 文档页数:7

17© Shreekant W Shiralkar 2016S. W. Shiralkar, IT Through Experiential Learning , DOI 10.1007/978-1-4842-2421-2_3C ontext:C ollaborative Learning and Collective Understanding of E RPDuring our school days, my friends and I frequently engaged in discussing specific topics from our textbooks. Each one of us comprehended a specific aspect of the larger subject, and when we shared understanding or knowledge of the topic, we found that our collective understanding helped us raise each individual’s understanding much faster and deeper than individually struggling to comprehend the subject. Later, we even formalized the process during the examination period as we found the process helping learn quickly. During my college days, we practiced the technique further by forming study groups, and when having difficulty understanding a topic, we broke it into subtopics and distributed among the group for learning parts individually and then collectively sharing it with the rest of the group. The process helped each one of us in comprehending knowledge which appeared difficult and complex to us as individuals. The results of learning through a process of discussion were impressive and gave me insight into a few aspects of the concept formally known as “cooperative learning,” which defines the process of learning together rather than being passive individual receivers of knowledge (e.g., teacher lecturing and students hearing). This process allows learners to use cognitive skills of questioning and clarifying, extrapolating and summarizing.I n one of my assignments, I was engaged to train the top management of an organization on ERP and the impact of its implementation. I anticipated that it would be a huge challenge to engage top executives in this training, as most would have had some understanding already, and applying a conventional training process risked losing their attention if my co-trainer or I fell short of their expectations. While individually each top executive may have had generic knowledge of ERP , they certainly lacked comprehensive knowledge, and more specifically a seamless collective understanding of the subject, without any gaps due to individual interpretations or exposures. The task, therefore, was multifaceted: on one hand, I had to get them interested in learning aspects of which they lacked knowledge, and on the other, I had to encourage them to share their individual understandings of the subject, facilitating development of a collective learning.CHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAME18F or a top executive, it is expected that he or she needs to take calculated risks inalmost every key decision, whether it’s bidding for a large contract or establishing price point while taking a privately held organization for public trading. The process of bidding involves awareness of collective knowledge of capability, assessment about competition, and expertise to apply judgment based on rational (and some irrational) criteria. In the knowledge-driven economy, the contributions of each employee, regardless of level, add up to the collective capability of the organization.W ith a view to facilitate collective learning in the shortest possible time for these top executives, I conceived a “Bidding Game” that leveraged cooperative learning to teach the ERP solution and the impact of its implementation in one session. The result in of Bidding Game was outstanding.T his is the premise of the game that will be explained in this chapter. The game also helps induce elements of social skills like effective communication and interpersonal and group skills in learning an otherwise abstract and complex subject.T he Bidding Game is a game played by all the participants divided into two or more teams. Teams compete on the strength of their collective knowledge of the subject. The game concludes after the collective learning on a specific subject is acquired to the appropriate level on all the essential aspects. The game format provides encouragement to each participant to contribute his or her knowledge of the subject and helps the team to win. A notional value attached to the correct and complete response helps measure the level of knowledge among participants. The competition is premised on the accuracy of the initial bid, which adds a flavor of bidding.F igure 3-1will help you visualize the setting created for the participants of the Bidding Game.F igure 3-1.I nstructor inviting b idsCHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAME19In a hall, participants will be seated in a U-shaped arrangement, facing the projector screen. The hall will have two whiteboards on either side of the projector screen. One of the whiteboards will be titled “Knowledge Bid” and will display the bids by participating t eams.T he second whiteboard will record the actual earnings or the SCORE for each of the teams. The projector screen will be used to publish the question for each of the bid, and the instructor will allow the teams to respond in sequence and will record the score on the whiteboard on the basis of the accuracy and completeness of response by the team (Figure 3-2).F igure 3-2.I nstructor inviting response to q uestion In designing the Bidding Game, the elements of competition and encouraging discussion on each aspect form the core theme. The competitive aspect triggers speed, the game element induces interest without force or pressure, and finally discussions and sharing of knowledge facilitate desired coverage of the subject—for instance, technical nuances and features offered by new technology and/or processes, channelling an accelerated Learning and Collective Understanding new technology and/or p rocesses .B idding Game Design To design the Bidding Game, I recommend ensuring that the pace of learning is accelerated gradually, and that learning begins with basic aspects and moves on to the advanced and complex aspects in sequence instead of beginning with complex subjects and then concluding with basics. In the design of the sequence, care has to be exercised in segregating the basic and must-learn aspects from the “nice-to-know” aspects, andCHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAME20design should ensure accomplishing learning of basic and must-learn ones whileprovisioning for nice-to-know types based on the interest and appetite of the participants. Design the sequence in such a way that initially the participant need to spend less time and are encouraged toward the game and competition, while later parts of the sequence should ensure that participants spend more time in discussions and staying ahead of competition.T he objective—rapid development of collective learning of technology and/or new processes—necessitates a short duration of the Bidding Game.L et us now examine the task-level details of the Bidding Game beginning with preparation/planning, recommended rules, and then the process for its execution,including steps to consolidate learning after conclusion. An overview of the entire game is depicted in Figure 3-3 .C omplete details of the activities in the process flow are described in detail in the following sections.P reparation/Planning •D ivide the subject into 20 subtopics that cover the subject comprehensively. • C reate a question for each of the subtopics.•C reate a sequence of questions in a way that gradually raises the level of knowledge. •S egment the questions into three levels: Rookie, Advanced, and Expert.•A ssign different values to questions from the three sets, for example, $100 per question from the Rookie level, $200 perquestion from the Advanced level, and $300 per question from the Expert level. •D evelop a clear rule set for the Bidding Game that can be used to explain the game to the participants.F igure 3-3.B idding Game p rocess flowCHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAME • H ave a scoreboard that displays the bid value of the team and alsotheir score during the progress of the game (use the whiteboardmarker pens).• H ave a large clock for monitoring time and identify assistants forkeeping time and recording the score.R ecommended Rules• T he winner is chosen on the basis of two parameters: high scoreas well as that which is closest to its bid.• E ach wrong or incomplete response has a loss of value (i.e.,negative marking); for example, a $50 penalty for each wrong orincomplete response.• $50 is deducted from the value of a passed-over question or apartly answered question.• T he completeness of the response to a question can be challengedby competing teams to apply penalty and reduce the score.• T here’s a limit of 5 minutes for responding to each question. Eachround could begin sequence in a way that provides a fair chanceto all the teams.O nce all the preparation is completed, the game can begin.E xecution1. A ll the participants are told the context and rationale for thegame (i.e., what ERP is and the importance of each of themhaving a collective understanding of the subject, which wouldmaximize benefit from its implementation). Also, it shouldbe explained how playing a game such as this can increaseindividual understanding much faster and more deeply thanindividually struggling to comprehend the subject in isolation.2. P articipants are divided into teams. Team formation canbe done in any way that generates nearly equal numbers ofparticipants for each team (dividing the room, counting off bytwos, etc.)3. T he instructor/quiz master (QM) invites bids from each of theteams, which are recorded on the whiteboard for everyone tosee.4. T he instructor launches the first question on the screen andinvites the first team to take its chance, while the timekeepermonitors the time taken by the responding team.21CHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAME225. O n the basis of correctness and completeness of the response,the instructor assigns a score to the team, which is recordedon the second whiteboard.6. I n case the question is passed to the second team and they areable to respond correctly and completely, the reduced score isrecorded.7. I n case the question is not answered or is incompletelyresponded by any of the teams, the instructor shares the correctand complete answer and the subject is discussed and clarified.8. T he process continues until the subject is completely covered.9. T he instructor tallies the scores for the teams and announcesthe winner on the basis of the high score and the bid a ccuracy .O nce the game is over, observations from experience are collected and crystallized inlearning in the next section.C onclusion• T he learning gained through the game needs to be articulatedand consolidated. Debrief is a process that will aid in articulatinglearning that participants gained during the game.• T he process of debrief begins with each participant sharinglearning, specifically something that has changed theirunderstanding about the subject during the game.• E ach participant would have learned something new, be it a verybasic addition to earlier knowledge of the subject or very complexinformation that the participant hadn’t ever known before.• T he individual learnings are recorded on a whiteboard, whichhelps in crystallizing and consolidating collective understandingon the subject.• O nce the game is over, the learning can be consolidated bypresenting additional material by way of slides, videos, and so on.S ample ArtifactsW ith a view to facilitate the immediate application of the approach in the chapter, a sample list of questions on ERP and Big Data along with an illustrative score sheet with result, are provided in the following section. The correct responses from multiple choices, are identified in bold.CHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAMES ample Question Cards:ERP1. W hat is the extended form of ERP?a. E nterprise Retail Processb. E nterprise Resource Planningc. E arning Revenue and Profitd. N one of the above2. R eal time in the context of ERP relates to which of thefollowing?a. T ime shown in the computer system synchs with yourwatchb. P rocesses/events happen per transaction at the sameinstantc. B oth of the aboved. N one of the above3. W hat does “SOA” stand for in relation to ERP systemarchitecture?a. S ervice-Oriented Architectureb. S ystem of Accountsc. S tatement of Accountd. N one of the above4. W hich of these is not a packaged ERP?a. S APb. O raclec. W indowsd. J D Edwards5. I n the context of packaged ERP, do “Customization” and“Configuration” refer to the same process, or are theydifferent?a. S ameb. D ifferentc.D on’t know23CHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAME246. M aterials Management in ERP helps to/esnure ?a. I ncrease of inventoryb. I nventory is well balancedc. B oth of the aboved. N one of the above7. S ales and Distribution Module in ERP helps in which of thefollowing?a. I ncreased customer serviceb. R educed customer servicec. B oth of the aboved. N one of the above8. F inancial and Controlling Module in ERP helps in which ofthe following?a. E valuating and responding to changing businessconditions with accurate, timely financial datab. E asy compliance with financial reporting requirementsc. S tandardizing and streamlining operationsd. A ll of the abovee. N one of the above9. G ain from implementation of ERP results in which of thefollowing?a. I mproved business performanceb. I mproved decision makingc. I ncreased ability to plan and growd. A ll of the aboveS ample Question Cards:B ig Data1. W hat is Big Data?a. D ata about big thingsb. D ata which is extremely large in size (in petabytes)c. D ata about datad. N one of the aboveCHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAME2. W hich are not characteristics of Big Data?a. V olumeb.V elocityc. V irtualityd.V ariety3. W hich are key inputs for Big Data?a.I ncreased processing powerb. A vailability of tools and techniques for Big Datac. I ncreased storage capacitiesd. A ll of the above4. W hich are applications of Big Data?a. T argeted advertisingb.M onitoring telecom networkc. C ustomer sentimentsd. A ll of the above5. W hich tools are used for Big Data?a. N oSQLb. M apReducec. H adoop Distributed File Systemd. A ll of the above6. S ocial media and mobility are key contributors to Big Data:true or false?a. T rueb. F alse7. W hich is not a term related to Big Data?a. D atabasesMongoDBb. D ata T riggerc. P igd. S PARK25CHAPTER 3 ■ BIDDING GAME26B enefit Assessment After consolidation of the learning, it’s recommended to conduct a benefit assessment exercise to measure the gains from application of the game-based approach. Theassessment could be in form of a written quiz on the subject with multiple-choice answers.。

多用户MIMO-MEC网络中基于APSO的任务卸载研究顾敏;徐雅男;王辛迪;花敏;周雯【期刊名称】《无线电工程》【年(卷),期】2024(54)3【摘要】在移动边缘计算(Mobile Edge Computing,MEC)系统中引入多输入多输出(Multiple Input Multiple Output,MIMO)技术与数据压缩技术,能够降低数据冗余度和提高数据传输速率,从而降低任务的执行时延与能耗。

针对具备数据压缩功能的多用户MIMO-MEC网络,研究了多用户任务卸载问题。

通过联合优化任务卸载比例、数据压缩比例、发送功率、计算频率和信道带宽,来最小化系统总时延。

在能耗、功率和带宽等约束条件下,将任务卸载归纳为一个非凸优化问题。

由于能耗约束较为复杂,构造罚函数将其归并,得到一个相对简单的等价问题。

将所有优化变量视为一个粒子,基于自适应粒子群优化(Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization,APSO)框架提出多用户的任务卸载方法。

由于粒子更新时可能违反约束条件,提出的方法对粒子越界的情形进行了特别处理。

该方法能自适应地调整惯性权重来提高寻优能力和收敛性,通过不断迭代最终获得最优或者次优解。

仿真实验评估了所提卸载方法的性能,分析了用户数、任务计算强度等参数对系统性能的影响。

结果表明,提出的方法优于本地计算、传统粒子群优化(Particle Swarm Optimization,PSO)算法等对比方案,能够有效降低系统的任务执行时延。

【总页数】8页(P711-718)【作者】顾敏;徐雅男;王辛迪;花敏;周雯【作者单位】南京林业大学信息科学技术学院;安徽大学互联网学院【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TN929.5;TP18【相关文献】1.基于延迟接受的多用户任务卸载策略2.基于稳定匹配的多用户任务卸载策略3.基于深度强化学习多用户移动边缘计算轻量任务卸载优化4.基于深度强化学习的多用户边缘计算任务卸载调度与资源分配算法5.基于博弈论的多服务器多用户视频分析任务卸载算法因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

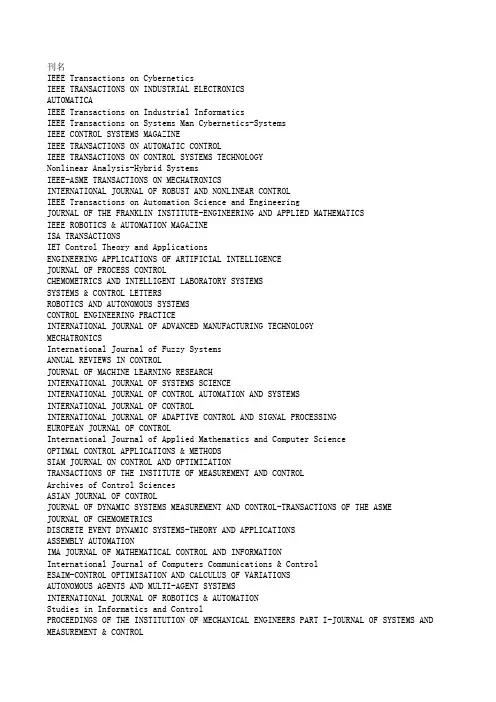

刊名IEEE Transactions on CyberneticsIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INDUSTRIAL ELECTRONICSAUTOMATICAIEEE Transactions on Industrial InformaticsIEEE Transactions on Systems Man Cybernetics-SystemsIEEE CONTROL SYSTEMS MAGAZINEIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AUTOMATIC CONTROLIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON CONTROL SYSTEMS TECHNOLOGYNonlinear Analysis-Hybrid SystemsIEEE-ASME TRANSACTIONS ON MECHATRONICSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ROBUST AND NONLINEAR CONTROLIEEE Transactions on Automation Science and EngineeringJOURNAL OF THE FRANKLIN INSTITUTE-ENGINEERING AND APPLIED MATHEMATICSIEEE ROBOTICS & AUTOMATION MAGAZINEISA TRANSACTIONSIET Control Theory and ApplicationsENGINEERING APPLICATIONS OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCEJOURNAL OF PROCESS CONTROLCHEMOMETRICS AND INTELLIGENT LABORATORY SYSTEMSSYSTEMS & CONTROL LETTERSROBOTICS AND AUTONOMOUS SYSTEMSCONTROL ENGINEERING PRACTICEINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVANCED MANUFACTURING TECHNOLOGYMECHATRONICSInternational Journal of Fuzzy SystemsANNUAL REVIEWS IN CONTROLJOURNAL OF MACHINE LEARNING RESEARCHINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SYSTEMS SCIENCEINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONTROL AUTOMATION AND SYSTEMSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF CONTROLINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADAPTIVE CONTROL AND SIGNAL PROCESSINGEUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CONTROLInternational Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computer ScienceOPTIMAL CONTROL APPLICATIONS & METHODSSIAM JOURNAL ON CONTROL AND OPTIMIZATIONTRANSACTIONS OF THE INSTITUTE OF MEASUREMENT AND CONTROLArchives of Control SciencesASIAN JOURNAL OF CONTROLJOURNAL OF DYNAMIC SYSTEMS MEASUREMENT AND CONTROL-TRANSACTIONS OF THE ASME JOURNAL OF CHEMOMETRICSDISCRETE EVENT DYNAMIC SYSTEMS-THEORY AND APPLICATIONSASSEMBLY AUTOMATIONIMA JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICAL CONTROL AND INFORMATIONInternational Journal of Computers Communications & ControlESAIM-CONTROL OPTIMISATION AND CALCULUS OF VARIATIONSAUTONOMOUS AGENTS AND MULTI-AGENT SYSTEMSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ROBOTICS & AUTOMATIONStudies in Informatics and ControlPROCEEDINGS OF THE INSTITUTION OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERS PART I-JOURNAL OF SYSTEMS AND MEASUREMENT & CONTROLMATHEMATICS OF CONTROL SIGNALS AND SYSTEMSInformation Technology and ControlControl Engineering and Applied InformaticsJOURNAL OF DYNAMICAL AND CONTROL SYSTEMSMODELING IDENTIFICATION AND CONTROLINTELLIGENT AUTOMATION AND SOFT COMPUTINGJournal of Systems Engineering and ElectronicsAUTOMATION AND REMOTE CONTROLAT-AutomatisierungstechnikRevista Iberoamericana de Automatica e Informatica Industrial AutomatikaSLAS DiscoveryINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF COMPUTER VISIONIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PATTERN ANALYSIS AND MACHINE INTELLIGENCE IEEE Transactions on CyberneticsIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON FUZZY SYSTEMSIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON EVOLUTIONARY COMPUTATIONIEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems NEURAL NETWORKSInformation FusionIEEE Computational Intelligence MagazineMEDICAL IMAGE ANALYSISIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON IMAGE PROCESSINGIEEE Transactions on Affective ComputingInternational Journal of Neural SystemsKNOWLEDGE-BASED SYSTEMSNEURAL COMPUTING & APPLICATIONSPATTERN RECOGNITIONAPPLIED SOFT COMPUTINGSwarm and Evolutionary ComputationARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE REVIEWEXPERT SYSTEMS WITH APPLICATIONSINTEGRATED COMPUTER-AIDED ENGINEERINGJOURNAL OF INTELLIGENT MANUFACTURINGDECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMSCognitive ComputationINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INTELLIGENT SYSTEMSADVANCED ENGINEERING INFORMATICSNEUROCOMPUTINGARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCEACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and TechnologyIEEE Transactions on Autonomous Mental Development ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN MEDICINEENGINEERING APPLICATIONS OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCEIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE AND DATA ENGINEERING CHEMOMETRICS AND INTELLIGENT LABORATORY SYSTEMSInternational Journal of Machine Learning and CyberneticsROBOTICS AND AUTONOMOUS SYSTEMSFrontiers in NeuroroboticsIEEE INTELLIGENT SYSTEMSIEEE Transactions on Human-Machine SystemsDATA MINING AND KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERYMECHATRONICSInternational Journal of Fuzzy SystemsCOMPUTER VISION AND IMAGE UNDERSTANDINGEVOLUTIONARY COMPUTATIONSOFT COMPUTINGSIAM Journal on Imaging SciencesJOURNAL OF MACHINE LEARNING RESEARCHInternational Journal of Bio-Inspired ComputationKNOWLEDGE AND INFORMATION SYSTEMSAUTONOMOUS ROBOTSSemantic WebIMAGE AND VISION COMPUTINGFuzzy Optimization and Decision MakingInternational Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems APPLIED INTELLIGENCEIEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental SystemsPATTERN RECOGNITION LETTERSWiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICAL IMAGING AND VISIONMemetic ComputingMACHINE LEARNINGIET BiometricsNEURAL PROCESSING LETTERSCOMPUTER SPEECH AND LANGUAGEINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF APPROXIMATE REASONINGINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY & DECISION MAKING International Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science NEURAL COMPUTATIONJOURNAL OF INTELLIGENT & ROBOTIC SYSTEMSJournal of Real-Time Image ProcessingSwarm IntelligenceJOURNAL OF CHEMOMETRICSDATA & KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERINGGenetic Programming and Evolvable MachinesEXPERT SYSTEMSJOURNAL OF INTELLIGENT & FUZZY SYSTEMSCognitive Systems ResearchJournal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized ComputingIET Image ProcessingCOMPUTATIONAL INTELLIGENCEJournal of Web SemanticsJOURNAL OF AUTOMATED REASONINGCOMPUTATIONAL LINGUISTICSMACHINE VISION AND APPLICATIONSInternational Journal on Document Analysis and Recognition PATTERN ANALYSIS AND APPLICATIONSJOURNAL OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE RESEARCHACM Transactions on Autonomous and Adaptive SystemsAUTONOMOUS AGENTS AND MULTI-AGENT SYSTEMSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF UNCERTAINTY FUZZINESS AND KNOWLEDGE-BASED SYSTEMS Journal on Multimodal User InterfacesJOURNAL OF HEURISTICSJOURNAL OF INTELLIGENT INFORMATION SYSTEMSIET Computer VisionKNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING REVIEWAI EDAM-ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE FOR ENGINEERING DESIGN ANALYSIS AND MANUFACTURING AI MAGAZINEINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PATTERN RECOGNITION AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL & THEORETICAL ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCEADAPTIVE BEHAVIORCONNECTION SCIENCEANNALS OF MATHEMATICS AND ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCEARTIFICIAL LIFEIEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in GamesJournal of Ambient Intelligence and Smart EnvironmentsStatistical Analysis and Data MiningNatural ComputingMINDS AND MACHINESInformation Technology and ControlNatural Language EngineeringInternational Journal on Semantic Web and Information SystemsBiologically Inspired Cognitive ArchitecturesApplied OntologyNETWORK-COMPUTATION IN NEURAL SYSTEMSAdvances in Electrical and Computer EngineeringIntelligent Data AnalysisCONSTRAINTSINTELLIGENT AUTOMATION AND SOFT COMPUTINGMalaysian Journal of Computer ScienceAPPLIED ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCETurkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer SciencesInternational Journal on Artificial Intelligence ToolsJOURNAL OF COMPUTER AND SYSTEMS SCIENCES INTERNATIONALJournal of Logic Language and InformationNeural Network WorldInternational Arab Journal of Information TechnologyAI COMMUNICATIONSJOURNAL OF MULTIPLE-VALUED LOGIC AND SOFT COMPUTINGCOMPUTING AND INFORMATICSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOFTWARE ENGINEERING AND KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERINGACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing Traitement du SignalIEEE Transactions on CyberneticsIEEE Transactions on Systems Man Cybernetics-SystemsIEEE Transactions on Affective ComputingHUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTIONUSER MODELING AND USER-ADAPTED INTERACTIONIEEE Transactions on Human-Machine SystemsINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMAN-COMPUTER STUDIESIEEE Transactions on HapticsBIOLOGICAL CYBERNETICSBEHAVIOUR & INFORMATION TECHNOLOGYMACHINE VISION AND APPLICATIONSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTIONCYBERNETICS AND SYSTEMSUniversal Access in the Information SocietyJournal on Multimodal User InterfacesKYBERNETESACM Transactions on Computer-Human InteractionINTERACTING WITH COMPUTERSMODELING IDENTIFICATION AND CONTROLKYBERNETIKAJOURNAL OF COMPUTER AND SYSTEMS SCIENCES INTERNATIONALPRESENCE-TELEOPERATORS AND VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENTSIEEE WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONSIEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning SystemsIEEE NETWORKIEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure ComputingJOURNAL OF NETWORK AND COMPUTER APPLICATIONSIEEE-ACM TRANSACTIONS ON NETWORKINGCOMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACMIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTERSJournal of Optical Communications and NetworkingIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON RELIABILITYVLDB JOURNALComputer NetworksMOBILE NETWORKS & APPLICATIONSIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-AIDED DESIGN OF INTEGRATED CIRCUITS AND SYSTEMS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HIGH PERFORMANCE COMPUTING APPLICATIONSCOMPUTERIEEE MICROIEEE MULTIMEDIAPERFORMANCE EVALUATIONCOMPUTERS & ELECTRICAL ENGINEERINGIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VERY LARGE SCALE INTEGRATION (VLSI) SYSTEMSJOURNAL OF THE ACMACM Journal on Emerging Technologies in Computing SystemsIEEE Design & TestJOURNAL OF SUPERCOMPUTINGIEEE Computer Architecture LettersAdvances in ComputersJOURNAL OF COMPUTER AND SYSTEM SCIENCESCOMPUTER STANDARDS & INTERFACESIEEE Consumer Electronics MagazineSustainable Computing-Informatics & SystemsDISPLAYSACM Transactions on Embedded Computing SystemsACM Transactions on Architecture and Code OptimizationNETWORKSMICROPROCESSORS AND MICROSYSTEMSACM Transactions on Reconfigurable Technology and SystemsCANADIAN JOURNAL OF ELECTRICAL AND COMPUTER ENGINEERING-REVUE CANADIENNE DE GENIEIBM JOURNAL OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENTACM Transactions on StorageJOURNAL OF SYSTEMS ARCHITECTUREINTEGRATION-THE VLSI JOURNALJOURNAL OF COMPUTER SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMSCOMPUTER SYSTEMS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERINGANALOG INTEGRATED CIRCUITS AND SIGNAL PROCESSINGCOMPUTER JOURNALNEW GENERATION COMPUTINGIET Computers and Digital TechniquesJOURNAL OF CIRCUITS SYSTEMS AND COMPUTERSDESIGN AUTOMATION FOR EMBEDDED SYSTEMSIEICE TRANSACTIONS ON FUNDAMENTALS OF ELECTRONICS COMMUNICATIONS AND COMPUTER SCIENCES IEEE Communications Surveys and TutorialsIEEE WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONSIEEE Transactions on Cloud ComputingIEEE NETWORKIEEE Internet of Things JournalMIS QUARTERLYJOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGYIEEE Transactions on Services ComputingIEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure ComputingIEEE Systems JournalJOURNAL OF STRATEGIC INFORMATION SYSTEMSINFORMATION SCIENCESJOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL INFORMATICS ASSOCIATIONIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MOBILE COMPUTINGIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIAJournal of CheminformaticsINFORMATION & MANAGEMENTIEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health InformaticsInternet ResearchJournal of Chemical Information and ModelingIEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in ComputingACM SIGCOMM Computer Communication ReviewDECISION SUPPORT SYSTEMSIEEE AccessINFORMATION PROCESSING & MANAGEMENTIEEE Transactions on Network and Service ManagementINFORMATION SYSTEMS FRONTIERSEUROPEAN JOURNAL OF INFORMATION SYSTEMSAd Hoc NetworksFoundations and Trends in Information RetrievalIEEE Wireless Communications LettersIEEE PERVASIVE COMPUTINGPervasive and Mobile ComputingACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and TechnologyINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MEDICAL INFORMATICSIEEE Cloud ComputingJournal of the Association for Information SystemsJournal of the Association for Information Science and TechnologyJournal of Grid ComputingIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE AND DATA ENGINEERINGJOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT INFORMATION SYSTEMSJournal of Optical Communications and NetworkingVLDB JOURNALCOMPUTERS & SECURITYINFORMATION AND SOFTWARE TECHNOLOGYCOMPUTER COMMUNICATIONSBusiness & Information Systems EngineeringACM Transactions on Information and System SecurityElectronic Commerce Research and ApplicationsINFORMATION SYSTEMSComputer NetworksMOBILE NETWORKS & APPLICATIONSDATA MINING AND KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERYINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GEOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION SCIENCEACM Transactions on Sensor NetworksKNOWLEDGE AND INFORMATION SYSTEMSSemantic WebScience China-Information SciencesIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION THEORYInternational Journal of Critical Infrastructure Protection GEOINFORMATICAACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing Communications and Applications WIRELESS NETWORKSHuman-centric Computing and Information SciencesJOURNAL OF INFORMATION SCIENCEPersonal and Ubiquitous ComputingIEEE MULTIMEDIAJOURNAL OF VISUAL COMMUNICATION AND IMAGE REPRESENTATIONInternational Journal of Distributed Sensor NetworksDigital InvestigationACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY & DECISION MAKINGJournal of Network and Systems ManagementREQUIREMENTS ENGINEERINGJOURNAL OF THE ACMACM Transactions on Internet TechnologyMULTIMEDIA SYSTEMSEnterprise Information SystemsONLINE INFORMATION REVIEWInternational Journal of Information SecurityIT ProfessionalCluster Computing-The Journal of Networks Software Tools and Applications JOURNAL OF COMPUTER INFORMATION SYSTEMSMULTIMEDIA TOOLS AND APPLICATIONSMETHODS OF INFORMATION IN MEDICINEPeer-to-Peer Networking and ApplicationsACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from DataInformation Retrieval JournalDATA & KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERINGAslib Journal of Information ManagementJournal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized ComputingJOURNAL OF ORGANIZATIONAL COMPUTING AND ELECTRONIC COMMERCE INFORMATICATSINGHUA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYJournal of Web SemanticsInternational Journal of Network ManagementJournal of Internet TechnologyInternational Journal of Computers Communications & ControlSIGMOD RECORDINFORMATION SYSTEMS MANAGEMENTJOURNAL OF COMMUNICATIONS AND NETWORKSIEEE SECURITY & PRIVACYACM Transactions on Autonomous and Adaptive SystemsPHOTONIC NETWORK COMMUNICATIONSSustainable Computing-Informatics & SystemsPROGRAM-ELECTRONIC LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SYSTEMSACM Transactions on the WebWORLD WIDE WEB-INTERNET AND WEB INFORMATION SYSTEMSOptical Switching and NetworkingJOURNAL OF INTELLIGENT INFORMATION SYSTEMSFrontiers of Computer ScienceJournal of Signal Processing Systems for Signal Image and Video Technology International Journal of Web and Grid ServicesACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMSNew Review of Hypermedia and MultimediaACM Transactions on Computer-Human InteractionINFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND LIBRARIESIBM JOURNAL OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENTMobile Information SystemsDISTRIBUTED AND PARALLEL DATABASESFrontiers of Information Technology & Electronic EngineeringSecurity and Communication NetworksIET Information SecurityACTA INFORMATICAInternational Journal of Sensor NetworksJournal of Ambient Intelligence and Smart EnvironmentsWIRELESS COMMUNICATIONS & MOBILE COMPUTINGInformation Technology and ControlINFORMATION PROCESSING LETTERSInternational Journal on Semantic Web and Information SystemsCOMPUTER JOURNALApplied OntologyAd Hoc & Sensor Wireless NetworksJournal of Organizational and End User ComputingInternational Journal of Ad Hoc and Ubiquitous ComputingComputer Science and Information SystemsKSII Transactions on Internet and Information SystemsIEEE Latin America TransactionsIEICE TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEMSInternational Arab Journal of Information TechnologyACM Transactions on Privacy and SecurityInternational Journal of Web Services ResearchRAIRO-THEORETICAL INFORMATICS AND APPLICATIONSIEICE TRANSACTIONS ON FUNDAMENTALS OF ELECTRONICS COMMUNICATIONS AND COMPUTER SCIENCES JOURNAL OF INFORMATION SCIENCE AND ENGINEERINGINFORJOURNAL OF DATABASE MANAGEMENTINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF COOPERATIVE INFORMATION SYSTEMSJournal of Statistical SoftwareARCHIVES OF COMPUTATIONAL METHODS IN ENGINEERINGIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MEDICAL IMAGINGCOMPUTER-AIDED CIVIL AND INFRASTRUCTURE ENGINEERINGIEEE Transactions on Industrial InformaticsMEDICAL IMAGE ANALYSISCOMPUTERS & EDUCATIONJOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL INFORMATICS ASSOCIATIONENVIRONMENTAL MODELLING & SOFTWAREJOURNAL OF NETWORK AND COMPUTER APPLICATIONSAPPLIED SOFT COMPUTINGJournal of CheminformaticsNEUROINFORMATICSIEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health InformaticsJournal of Chemical Information and ModelingCOMPUTER PHYSICS COMMUNICATIONSINTEGRATED COMPUTER-AIDED ENGINEERINGJournal of InformetricsROBOTICS AND COMPUTER-INTEGRATED MANUFACTURINGSOCIAL SCIENCE COMPUTER REVIEWADVANCES IN ENGINEERING SOFTWARECOMPUTERS & INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERINGCOMPUTERS AND GEOTECHNICSCOMPUTERS & CHEMICAL ENGINEERINGCOMPUTERS & OPERATIONS RESEARCHINDUSTRIAL MANAGEMENT & DATA SYSTEMSCOMPUTERS & STRUCTURESJOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL INFORMATICSSTRUCTURAL AND MULTIDISCIPLINARY OPTIMIZATIONJOURNAL OF COMPUTATIONAL PHYSICSCOMPUTERS IN INDUSTRYAstronomy and ComputingCOMPUTATIONAL GEOSCIENCESCOMPUTER METHODS AND PROGRAMS IN BIOMEDICINEElectronic Commerce Research and ApplicationsMATCH-COMMUNICATIONS IN MATHEMATICAL AND IN COMPUTER CHEMISTRYCOMPUTERS & GEOSCIENCESIEEE-ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and BioinformaticsCOMPUTERS AND ELECTRONICS IN AGRICULTURESOFT COMPUTINGJOURNAL OF COMPUTER-AIDED MOLECULAR DESIGNSAR AND QSAR IN ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCHCOMPUTERS & FLUIDSSCIENTOMETRICSCOMPUTERS IN BIOLOGY AND MEDICINESIMULATION MODELLING PRACTICE AND THEORYIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-AIDED DESIGN OF INTEGRATED CIRCUITS AND SYSTEMS INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HIGH PERFORMANCE COMPUTING APPLICATIONSInternational Journal of Computational Intelligence SystemsINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF COMPUTER INTEGRATED MANUFACTURINGCOMPUTER METHODS IN BIOMECHANICS AND BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERINGMEDICAL & BIOLOGICAL ENGINEERING & COMPUTINGMolecular InformaticsENGINEERING WITH COMPUTERSJournal of Computational ScienceJOURNAL OF MOLECULAR GRAPHICS & MODELLINGIEEE Transactions on Learning TechnologiesJOURNAL OF COMPUTING IN CIVIL ENGINEERINGJOURNAL OF HYDROINFORMATICSDigital InvestigationINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY & DECISION MAKINGCOMPUTERS & ELECTRICAL ENGINEERINGINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR NUMERICAL METHODS IN FLUIDSComputers and ConcreteEarth Science InformaticsJOURNAL OF COMPUTING AND INFORMATION SCIENCE IN ENGINEERINGSPEECH COMMUNICATIONJOURNAL OF MOLECULAR MODELINGBig DataMATHEMATICS AND COMPUTERS IN SIMULATIONCONCURRENT ENGINEERING-RESEARCH AND APPLICATIONSJOURNAL OF ORGANIZATIONAL COMPUTING AND ELECTRONIC COMMERCECOMPUTATIONAL BIOLOGY AND CHEMISTRYINFORMS JOURNAL ON COMPUTINGVIRTUAL REALITYR JournalCOMPUTATIONAL LINGUISTICSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RF AND MICROWAVE COMPUTER-AIDED ENGINEERINGJournal of SimulationJOURNAL OF COMPUTATIONAL BIOLOGYCOMPUTATIONAL STATISTICS & DATA ANALYSISENGINEERING COMPUTATIONSQUEUEING SYSTEMSCOMPUTER APPLICATIONS IN ENGINEERING EDUCATIONCOMPUTING IN SCIENCE & ENGINEERINGCIN-COMPUTERS INFORMATICS NURSINGAI EDAM-ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE FOR ENGINEERING DESIGN ANALYSIS AND MANUFACTURING JOURNAL OF NEW MUSIC RESEARCHJOURNAL OF VISUALIZATIONSIMULATION-TRANSACTIONS OF THE SOCIETY FOR MODELING AND SIMULATION INTERNATIONAL ACM Transactions on Modeling and Computer SimulationJOURNAL OF COMBINATORIAL OPTIMIZATIONINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MODERN PHYSICS CJOURNAL OF STATISTICAL COMPUTATION AND SIMULATIONStatistical Analysis and Data MiningCurrent Computer-Aided Drug DesignComputer Supported Cooperative Work-The Journal of Collaborative Computing Language Resources and EvaluationComputational and Mathematical Organization TheoryMATHEMATICAL AND COMPUTER MODELLING OF DYNAMICAL SYSTEMSCOMPUTER MUSIC JOURNALInternational Journal on Artificial Intelligence ToolsCOMPEL-THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR COMPUTATION AND MATHEMATICS IN ELECTRICAL AND ACM Journal on Computing and Cultural HeritageAPPLICABLE ALGEBRA IN ENGINEERING COMMUNICATION AND COMPUTINGIEEE Transactions on Services ComputingIEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure ComputingACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICSJOURNAL OF NETWORK AND COMPUTER APPLICATIONSIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIAIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SOFTWARE ENGINEERINGADVANCES IN ENGINEERING SOFTWAREIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON VISUALIZATION AND COMPUTER GRAPHICSCOMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACMCOMPUTER-AIDED DESIGNEMPIRICAL SOFTWARE ENGINEERINGACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWAREIEEE SOFTWAREIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON RELIABILITYMATHEMATICAL PROGRAMMINGINFORMATION AND SOFTWARE TECHNOLOGYINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ELECTRONIC COMMERCESIAM Journal on Imaging SciencesJOURNAL OF SYSTEMS AND SOFTWAREIMAGE AND VISION COMPUTINGSIMULATION MODELLING PRACTICE AND THEORYCOMPUTER GRAPHICS FORUMACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing Communications and ApplicationsACM TRANSACTIONS ON SOFTWARE ENGINEERING AND METHODOLOGYCOMPUTERIEEE INTERNET COMPUTINGJOURNAL OF MATHEMATICAL IMAGING AND VISIONIEEE MICROIEEE MULTIMEDIACOMPUTER LANGUAGES SYSTEMS & STRUCTURESJOURNAL OF VISUAL COMMUNICATION AND IMAGE REPRESENTATIONAutomated Software EngineeringREQUIREMENTS ENGINEERINGJOURNAL OF THE ACMACM Transactions on Internet TechnologySoftware and Systems ModelingInternational Journal of Information SecurityIEEE COMPUTER GRAPHICS AND APPLICATIONSIT ProfessionalSOFTWARE QUALITY JOURNALSOFTWARE TESTING VERIFICATION & RELIABILITYMULTIMEDIA TOOLS AND APPLICATIONSCOMPUTER AIDED GEOMETRIC DESIGNAdvances in ComputersACM Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from DataMATHEMATICS AND COMPUTERS IN SIMULATIONCOMPUTER STANDARDS & INTERFACESBIT NUMERICAL MATHEMATICSVIRTUAL REALITYTSINGHUA SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYJournal of Web SemanticsScientific ProgrammingSOFTWARE-PRACTICE & EXPERIENCESIGMOD RECORDIEEE SECURITY & PRIVACYCOMPUTERS & GRAPHICS-UKOPTIMIZATION METHODS & SOFTWAREJournal of Software-Evolution and ProcessACM Transactions on the WebACM Transactions on Embedded Computing SystemsWORLD WIDE WEB-INTERNET AND WEB INFORMATION SYSTEMSCONCURRENCY AND COMPUTATION-PRACTICE & EXPERIENCEFrontiers of Computer ScienceInternational Journal on Software Tools for Technology TransferInternational Journal of Web and Grid ServicesJOURNAL OF UNIVERSAL COMPUTER SCIENCEVISUAL COMPUTERGRAPHICAL MODELSACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMSRANDOM STRUCTURES & ALGORITHMSJOURNAL OF VISUAL LANGUAGES AND COMPUTINGACM Transactions on Applied PerceptionIBM JOURNAL OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENTIET SoftwareSIMULATION-TRANSACTIONS OF THE SOCIETY FOR MODELING AND SIMULATION INTERNATIONAL ACM Transactions on StorageInformation VisualizationJOURNAL OF SYSTEMS ARCHITECTUREFrontiers of Information Technology & Electronic EngineeringIEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in GamesJOURNAL OF COMPUTER SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGYTHEORY AND PRACTICE OF LOGIC PROGRAMMINGACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMSFORMAL ASPECTS OF COMPUTINGCOMPUTER JOURNALInternational Journal of Data Warehousing and MiningACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMSSCIENCE OF COMPUTER PROGRAMMINGFUNDAMENTA INFORMATICAEJOURNAL OF FUNCTIONAL PROGRAMMINGCOMPUTER ANIMATION AND VIRTUAL WORLDSALGORITHMICAComputer Science and Information SystemsDISCRETE MATHEMATICS AND THEORETICAL COMPUTER SCIENCEInternational Journal of Wavelets Multiresolution and Information Processing DESIGN AUTOMATION FOR EMBEDDED SYSTEMSIEICE TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEMSPRESENCE-TELEOPERATORS AND VIRTUAL ENVIRONMENTSInternational Journal of Web Services ResearchINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SOFTWARE ENGINEERING AND KNOWLEDGE ENGINEERING ICGA JOURNALJournal of Web EngineeringPROGRAMMING AND COMPUTER SOFTWAREJOURNAL OF DATABASE MANAGEMENTIEEE TRANSACTIONS ON EVOLUTIONARY COMPUTATIONIEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning SystemsIEEE Transactions on Cloud ComputingInformation FusionIEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and SecurityACM COMPUTING SURVEYSFuture Generation Computer Systems-The International Journal of eScience IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PARALLEL AND DISTRIBUTED SYSTEMSSwarm and Evolutionary ComputationHUMAN-COMPUTER INTERACTIONINFORMATION SYSTEMS FRONTIERSIEEE-ACM TRANSACTIONS ON NETWORKINGCOMMUNICATIONS OF THE ACMFOUNDATIONS OF COMPUTATIONAL MATHEMATICSINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF GENERAL SYSTEMSIEEE Cloud ComputingJournal of Grid ComputingFUZZY SETS AND SYSTEMSCOMPUTER METHODS AND PROGRAMS IN BIOMEDICINEEVOLUTIONARY COMPUTATIONJOURNAL OF SYSTEMS AND SOFTWAREInternational Journal of Bio-Inspired ComputationSemantic WebINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SYSTEMS SCIENCEIMAGE AND VISION COMPUTINGMULTIDIMENSIONAL SYSTEMS AND SIGNAL PROCESSINGACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing Communications and Applications INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HIGH PERFORMANCE COMPUTING APPLICATIONSWiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Data Mining and Knowledge DiscoveryJournal of Computational ScienceIEEE MULTIMEDIASTATISTICS AND COMPUTINGJOURNAL OF PARALLEL AND DISTRIBUTED COMPUTINGPERFORMANCE EVALUATIONACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMSJOURNAL OF THE ACMMULTIMEDIA SYSTEMSInternational Journal of Information SecurityCOMPUTINGCluster Computing-The Journal of Networks Software Tools and Applications QUANTUM INFORMATION & COMPUTATIONREAL-TIME SYSTEMSMULTIMEDIA TOOLS AND APPLICATIONSJOURNAL OF SUPERCOMPUTINGJOURNAL OF COMPUTER AND SYSTEM SCIENCESBig DataGenetic Programming and Evolvable MachinesEXPERT SYSTEMSACM Transactions on Autonomous and Adaptive SystemsCryptography and Communications-Discrete-Structures Boolean Functions and Sequences ACM Transactions on Architecture and Code OptimizationJOURNAL OF HEURISTICSCONCURRENCY AND COMPUTATION-PRACTICE & EXPERIENCEDESIGNS CODES AND CRYPTOGRAPHYFrontiers of Computer ScienceMATHEMATICAL STRUCTURES IN COMPUTER SCIENCEINFORMATION AND COMPUTATIONJOURNAL OF UNIVERSAL COMPUTER SCIENCEJOURNAL OF CRYPTOLOGYMICROPROCESSORS AND MICROSYSTEMSInternational Journal of Unconventional ComputingIBM JOURNAL OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENTPARALLEL COMPUTINGCONNECTION SCIENCEDISTRIBUTED AND PARALLEL DATABASESSIAM JOURNAL ON COMPUTINGARTIFICIAL LIFEINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PARALLEL PROGRAMMINGIET Information SecurityTHEORY AND PRACTICE OF LOGIC PROGRAMMINGNatural ComputingCOMPUTER SYSTEMS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERINGDISTRIBUTED COMPUTINGFORMAL METHODS IN SYSTEM DESIGNCOMPUTER JOURNALApplied OntologyTHEORETICAL COMPUTER SCIENCEJOURNAL OF SYMBOLIC COMPUTATIONJOURNAL OF LOGIC AND COMPUTATIONINTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF QUANTUM INFORMATIONACM Transactions on Computational LogicNEW GENERATION COMPUTINGCOMBINATORICS PROBABILITY & COMPUTINGDISCRETE & COMPUTATIONAL GEOMETRY。

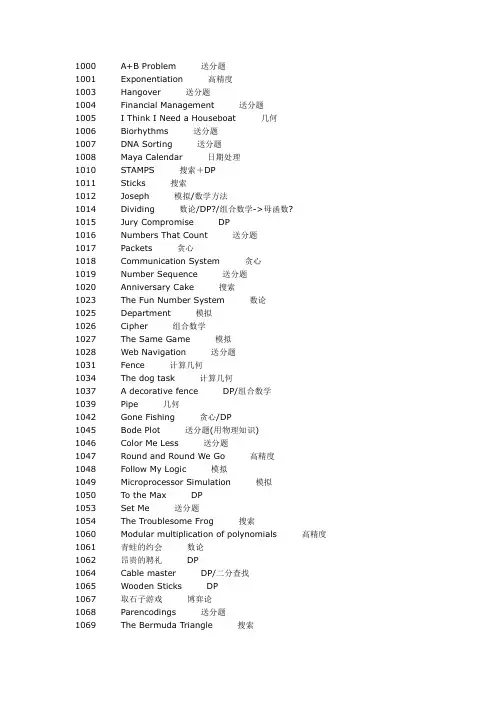

1000 A+B Problem 送分题1001 Exponentiation 高精度1003 Hangover 送分题1004 Financial Management 送分题1005 I Think I Need a Houseboat 几何1006 Biorhythms 送分题1007 DNA Sorting 送分题1008 Maya Calendar 日期处理1010 STAMPS 搜索+DP1011 Sticks 搜索1012 Joseph 模拟/数学方法1014 Dividing 数论/DP?/组合数学->母函数?1015 Jury Compromise DP1016 Numbers That Count 送分题1017 Packets 贪心1018 Communication System 贪心1019 Number Sequence 送分题1020 Anniversary Cake 搜索1023 The Fun Number System 数论1025 Department 模拟1026 Cipher 组合数学1027 The Same Game 模拟1028 Web Navigation 送分题1031 Fence 计算几何1034 The dog task 计算几何1037 A decorative fence DP/组合数学1039 Pipe 几何1042 Gone Fishing 贪心/DP1045 Bode Plot 送分题(用物理知识)1046 Color Me Less 送分题1047 Round and Round We Go 高精度1048 Follow My Logic 模拟1049 Microprocessor Simulation 模拟1050 To the Max DP1053 Set Me 送分题1054 The Troublesome Frog 搜索1060 Modular multiplication of polynomials 高精度1061 青蛙的约会数论1062 昂贵的聘礼DP1064 Cable master DP/二分查找1065 Wooden Sticks DP1067 取石子游戏博弈论1068 Parencodings 送分题1069 The Bermuda Triangle 搜索1070 Deformed Wheel 几何1071 Illusive Chase 送分题1072 Puzzle Out 搜索1073 The Willy Memorial Program 模拟1074 Parallel Expectations DP1075 University Entrance Examination 模拟1080 Human Gene Functions DP->LCS变形1082 Calendar Game 博弈论1084 Square Destroyer 搜索?1085 Triangle War 博弈论1086 Unscrambling Images 模拟?1087 A Plug for UNIX 图论->最大流1088 滑雪DFS/DP1090 Chain ->格雷码和二进制码的转换1091 跳蚤数论1092 Farmland 几何1093 Formatting Text DP1094 Sorting It All Out 图论->拓扑排序1095 Trees Made to Order 组合数学1096 Space Station Shielding 送分题1097 Roads Scholar 图论1098 Robots 模拟1099 Square Ice 送分题1100 Dreisam Equations 搜索1101 The Game 搜索->BFS1102 LC-Display 送分题1103 Maze 模拟1104 Robbery 递推1106 Transmitters 几何1107 W's Cipher 送分题1110 Double Vision 搜索1111 Image Perimeters 搜索1112 Team Them Up! DP1113 Wall 计算几何->convex hull1119 Start Up the Startup 送分题1120 A New Growth Industry 模拟1122 FDNY to the Rescue! 图论->Dijkstra 1125 Stockbroker Grapevine 图论->Dijkstra 1128 Frame Stacking 搜索1129 Channel Allocation 搜索(图的最大独立集)1131 Octal Fractions 高精度1135 Domino Effect 图论->Dijkstra1137 The New Villa 搜索->BFS1141 Brackets Sequence DP1142 Smith Numbers 搜索1143 Number Game 博弈论1147 Binary codes 构造1148 Utopia Divided 构造1149 PIGS 图论->网络流1151 Atlantis 计算几何->同等安置矩形的并的面积->离散化1152 An Easy Problem! 数论1157 LITTLE SHOP OF FLOWERS DP1158 TRAFFIC LIGHTS 图论->Dijkstra变形1159 Palindrome DP->LCS1160 Post Office DP1161 Walls 图论1162 Building with Blocks 搜索1163 The Triangle DP1170 Shopping Offers DP1177 Picture 计算几何->同等安置矩形的并的周长->线段树1179 Polygon DP1180 Batch Scheduling DP1182 食物链数据结构->并查集1183 反正切函数的应用搜索1184 聪明的打字员搜索1185 炮兵阵地DP->数据压缩1187 陨石的秘密DP(BalkanOI99 Par的拓展)1189 钉子和小球递推?1190 生日蛋糕搜索/DP1191 棋盘分割DP1192 最优连通子集图论->无负权回路的有向图的最长路->BellmanFord 1193 内存分配模拟1194 HIDDEN CODES 搜索+DP1197 Depot 数据结构->Young T ableau1201 Intervals 贪心/图论->最长路->差分约束系统1202 Family 高精度1209 Calendar 日期处理1217 FOUR QUARTERS 递推1218 THE DRUNK JAILER 送分题1233 Street Crossing 搜索->BFS1245 Programmer, Rank Thyself 送分题1247 Magnificent Meatballs 送分题1248 Safecracker 搜索1250 T anning Salon 送分题1251 Jungle Roads 图论->最小生成树1271 Nice Milk 计算几何1273 Drainage Ditches 图论->最大流1274 The Perfect Stall 图论->二分图的最大匹配1275 Cashier Employment 图论->差分约束系统->无负权回路的有向图的最长路->Bellman-Ford1280 Game 递推1281 MANAGER 模拟1286 Necklace of Beads 组合数学->Polya定理1288 Sly Number 数论->解模线性方程组1293 Duty Free Shop DP1298 The Hardest Problem Ever 送分题1316 Self Numbers 递推同Humble Number一样1322 Chocolate 递推/组合数学1323 Game Prediction 贪心1324 Holedox Moving BFS+压缩储存1325 Machine Schedule 图论->二分图的最大匹配1326 Mileage Bank 送分题1327 Moving Object Recognition 模拟?1328 Radar Installation 贪心(差分约束系统的特例)1338 Ugly Numbers 递推(有O(n)算法)1364 King 图论->无负权回路的有向图的最长路->BellmanFord1370 Gossiping (数论->模线性方程有无解的判断)+(图论->DFS)2184 Cow Exhibition DP2190 ISBN 送分题2191 Mersenne Composite Numbers 数论2192 Zipper DP->LCS变形2193 Lenny's Lucky Lotto Lists DP2194 Stacking Cylinders 几何2195 Going Home 图论->二分图的最大权匹配2196 Specialized Four-Digit Numbers 送分题2197 Jill's Tour Paths 图论->2199 Rate of Return 高精度2200 A Card Trick 模拟2210 Metric Time 日期处理2239 Selecting Courses 图论->二分图的最大匹配2243 Knight Moves 搜索->BFS2247 Humble Numbers 递推(最优O(n)算法)2253 Frogger 图论->Dijkstra变形(和1295是一样的)2254 Globetrotter 几何2261 France '98 递推2275 Flipping Pancake 构造2284 That Nice Euler Circuit 计算几何2289 Jamie's Contact Groups 图论->网络流?2291 Rotten Ropes 送分题2292 Optimal Keypad DP2299 Ultra-QuickSort 排序->归并排序2304 Combination Lock 送分题2309 BST 送分题2311 Cutting Game 博弈论2312 Battle City 搜索->BFS2314 POJ language 模拟2315 Football Game 几何2346 Lucky tickets 组合数学2351 Time Zones 时间处理2379 ACM Rank T able 模拟+排序2381 Random Gap 数论2385 Apple Catching DP(像NOI98“免费馅饼”)2388 Who's in the Middle 送分题(排序)2390 Bank Interest 送分题2395 Out of Hay 图论->Dijkstra变形2400 Supervisor, Supervisee 图论->二分图的最大权匹配?2403 Hay Points 送分题2409 Let it Bead 组合数学->Polya定理2416 Return of the Jedi 图论->2417 Discrete Logging 数论2418 Hardwood Species 二分查找2419 Forests 枚举2421 Constructing Roads 图论->最小生成树2423 The Parallel Challenge Ballgame 几何2424 Flo's Restaurant 数据结构->堆2425 A Chess Game 博弈论2426 Remainder BFS2430 Lazy Cows DP->数据压缩1375 Intervals 几何1379 Run Away 计算几何->1380 Equipment Box 几何1383 Labyrinth 图论->树的最长路1394 Railroad 图论->Dijkstra1395 Cog-Wheels 数学->解正系数的线性方程组1408 Fishnet 几何1411 Calling Extraterrestrial Intelligence Again 送分题1430 Binary Stirling Numbers 日期处理1431 Calendar of Maya 模拟1432 Decoding Morse Sequences DP1434 Fill the Cisterns! 计算几何->离散化/1445 Random number 数据结构->碓1447 Ambiguous Dates 日期处理1450 Gridland 图论(本来TSP问题是NP难的,但这个图比较特殊,由现成的构造方法)1458 Common Subsequence DP->LCS1459 Power Network 图论->最大流1462 Random Walk 模拟+解线性方程组1463 Strategic game 贪心1466 Girls and Boys 图论->n/a1469 COURSES 贪心1475 Pushing Boxes DP1476 Always On the Run 搜索->BFS1480 Optimal Programs 搜索->BFS1481 The Die Is Cast 送分题1482 It's not a Bug, It's a Feature! 搜索->BFS1483 Going in Circles on Alpha Centauri 模拟1484 Blowing Fuses 送分题1485 Fast Food DP(似乎就是ioi2000的postoffice)1486 Sorting Slides 图论->拓扑排序1505 Copying Books DP+二分查找1510 Hares and Foxes 数论1512 Keeps Going and Going and ... 模拟1513 Scheduling Lectures DP1514 Metal Cutting 几何1515 Street Directions 图论->把一个无向连通图改造成为有向强连通图1517 u Calculate e 送分题1518 Problem Bee 几何1519 Digital Roots 送分题(位数可能很大)1520 Scramble Sort 排序1547 Clay Bully 送分题1555 Polynomial Showdown 送分题(非常阴险)1563 The Snail 送分题1601 Pizza Anyone? 搜索1604 Just the Facts 送分题1605 Horse Shoe Scoring 几何1606 Jugs 数论/搜索1631 Bridging signals DP+二分查找1632 Vase collection 图论->最大完全图1633 Gladiators DP1634 Who's the boss? 排序1635 Subway tree systems 图论->不同表示法的二叉树判同1637 Sightseeing tour 图论->欧拉回路1638 A number game 博弈论1639 Picnic Planning 图论->1641 Rational Approximation 数论1646 Double Trouble 高精度1654 Area 几何1657 Distance on Chessboard 送分题1658 Eva's Problem 送分题1660 Princess FroG 构造1661 Help Jimmy DP1663 Number Steps 送分题1664 放苹果组合数学->递推1677 Girls' Day 送分题1688 Dolphin Pool 计算几何1690 (Your)((Term)((Project))) 送分题1691 Painting A Board 搜索/DP1692 Crossed Matchings DP1693 Counting Rectangles 几何1694 An Old Stone Game 博弈论?1695 Magazine Delivery 图论->1712 Flying Stars DP1713 Divide et unita 搜索1714 The Cave 搜索/DP1717 Dominoes DP1718 River Crossing DP1719 Shooting Contest 贪心1729 Jack and Jill 图论->1730 Perfect Pth Powers 数论1732 Phone numbers DP1734 Sightseeing trip 图论->Euler回路1738 An old Stone Game 博弈论?1741 Tree 博弈论?1745 Divisibility DP1751 Highways 图论->1752 Advertisement 贪心/图论->差分约束系统1753 Flip Game 搜索->BFS1755 Triathlon 计算几何?1770 Special Experiment 树形DP1771 Elevator Stopping Plan DP1772 New Go Game 构造?1773 Outernet 模拟1774 Fold Paper Strips 几何1775 Sum of Factorials 送分题1776 T ask Sequences DP1777 Vivian's Problem 数论1870 Bee Breeding 送分题1871 Bullet Hole 几何1872 A Dicey Problem BFS1873 The Fortified Forest 几何+回溯1874 Trade on Verweggistan DP1875 Robot 几何1876 The Letter Carrier's Rounds 模拟1877 Flooded! 数据结构->堆1879 Tempus et mobilius Time and motion 模拟+组合数学->Polya定理1882 Stamps 搜索+DP1883 Theseus and the Minotaur 模拟1887 Testing the CATCHER DP1889 Package Pricing DP1893 Monitoring Wheelchair Patients 模拟+几何1915 Knight Moves 搜索->BFS1916 Rat Attack 数据结构->?1936 All in All DP?1946 Cow Cycling DP1947 Rebuilding Roads 二分1985 Cow Marathon 图论->有向无环图的最长路1995 Raising Modulo Numbers 数论->大数的幂求余2049 Finding Nemo 图论->最短路2050 Searching the Web 模拟(需要高效实现)2051 Argus 送分题(最好用堆,不用也可以过)2054 Color a Tree 贪心2061 Pseudo-random Numbers 数论2080 Calendar 日期处理2082 Terrible Sets 分治/2083 Fractal 递归2084 Game of Connections 递推(不必高精度)2105 IP Address 送分题2115 C Looooops 数论->解模线性方程2136 Vertical Histogram 送分题2165 Gunman 计算几何2179 Inlay Cutters 枚举2181 Jumping Cows 递推2182 Lost Cows ->线段树/=============================================1370 Gossiping (数论->模线性方程有无解的判断)+(图论->DFS)1090 Chain ->格雷码和二进制码的转换2182 Lost Cows ->线段树/2426 Remainder BFS1872 A Dicey Problem BFS1324 Holedox Moving BFS+压缩储存1088 滑雪DFS/DP1015 Jury Compromise DP1050 To the Max DP1062 昂贵的聘礼DP1065 Wooden Sticks DP1074 Parallel Expectations DP1093 Formatting Text DP1112 Team Them Up! DP1141 Brackets Sequence DP1157 LITTLE SHOP OF FLOWERS DP1160 Post Office DP1163 The Triangle DP1170 Shopping Offers DP1179 Polygon DP1180 Batch Scheduling DP1191 棋盘分割DP1293 Duty Free Shop DP2184 Cow Exhibition DP2193 Lenny's Lucky Lotto Lists DP2292 Optimal Keypad DP1432 Decoding Morse Sequences DP1475 Pushing Boxes DP1513 Scheduling Lectures DP1633 Gladiators DP1661 Help Jimmy DP1692 Crossed Matchings DP1712 Flying Stars DP1717 Dominoes DP1718 River Crossing DP1732 Phone numbers DP1745 Divisibility DP1771 Elevator Stopping Plan DP1776 T ask Sequences DP1874 Trade on Verweggistan DP1887 Testing the CATCHER DP1889 Package Pricing DP1946 Cow Cycling DP1187 陨石的秘密DP(BalkanOI99 Par的拓展)1485 Fast Food DP(似乎就是ioi2000的postoffice) 2385 Apple Catching DP(像NOI98“免费馅饼”) 1064 Cable master DP/二分查找1037 A decorative fence DP/组合数学1936 All in All DP?1505 Copying Books DP+二分查找1631 Bridging signals DP+二分查找1159 Palindrome DP->LCS1458 Common Subsequence DP->LCS1080 Human Gene Functions DP->LCS变形2192 Zipper DP->LCS变形1185 炮兵阵地DP->数据压缩2430 Lazy Cows DP->数据压缩1067 取石子游戏博弈论1082 Calendar Game 博弈论1085 Triangle War 博弈论1143 Number Game 博弈论2311 Cutting Game 博弈论2425 A Chess Game 博弈论1638 A number game 博弈论1694 An Old Stone Game 博弈论?1738 An old Stone Game 博弈论?1741 Tree 博弈论?2083 Fractal 递归1104 Robbery 递推1217 FOUR QUARTERS 递推1280 Game 递推2261 France '98 递推2181 Jumping Cows 递推1316 Self Numbers 递推同Humble Number一样2084 Game of Connections 递推(不必高精度) 1338 Ugly Numbers 递推(有O(n)算法)2247 Humble Numbers 递推(最优O(n)算法)1322 Chocolate 递推/组合数学1189 钉子和小球递推?1947 Rebuilding Roads 二分2418 Hardwood Species 二分查找2082 Terrible Sets 分治/1001 Exponentiation 高精度1047 Round and Round We Go 高精度1060 Modular multiplication of polynomials 高精度1131 Octal Fractions 高精度1202 Family 高精度2199 Rate of Return 高精度1646 Double Trouble 高精度1147 Binary codes 构造1148 Utopia Divided 构造2275 Flipping Pancake 构造1660 Princess FroG 构造1772 New Go Game 构造?1005 I Think I Need a Houseboat 几何1039 Pipe 几何1070 Deformed Wheel 几何1092 Farmland 几何1106 Transmitters 几何2194 Stacking Cylinders 几何2254 Globetrotter 几何2315 Football Game 几何2423 The Parallel Challenge Ballgame 几何1375 Intervals 几何1380 Equipment Box 几何1408 Fishnet 几何1514 Metal Cutting 几何1518 Problem Bee 几何1605 Horse Shoe Scoring 几何1654 Area 几何1693 Counting Rectangles 几何1774 Fold Paper Strips 几何1871 Bullet Hole 几何1875 Robot 几何1873 The Fortified Forest 几何+回溯1031 Fence 计算几何1034 The dog task 计算几何1271 Nice Milk 计算几何2284 That Nice Euler Circuit 计算几何1688 Dolphin Pool 计算几何2165 Gunman 计算几何1755 Triathlon 计算几何?1379 Run Away 计算几何->1113 Wall 计算几何->convex hull1434 Fill the Cisterns! 计算几何->离散化/1151 Atlantis 计算几何->同等安置矩形的并的面积->离散化1177 Picture 计算几何->同等安置矩形的并的周长->线段树2419 Forests 枚举2179 Inlay Cutters 枚举1025 Department 模拟1027 The Same Game 模拟1048 Follow My Logic 模拟1049 Microprocessor Simulation 模拟1073 The Willy Memorial Program 模拟1075 University Entrance Examination 模拟1098 Robots 模拟1103 Maze 模拟1120 A New Growth Industry 模拟1193 内存分配模拟1281 MANAGER 模拟2200 A Card Trick 模拟2314 POJ language 模拟1431 Calendar of Maya 模拟1483 Going in Circles on Alpha Centauri 模拟1512 Keeps Going and Going and ... 模拟1773 Outernet 模拟1876 The Letter Carrier's Rounds 模拟1883 Theseus and the Minotaur 模拟2050 Searching the Web 模拟(需要高效实现)1012 Joseph 模拟/数学方法1086 Unscrambling Images 模拟?1327 Moving Object Recognition 模拟?1893 Monitoring Wheelchair Patients 模拟+几何1462 Random Walk 模拟+解线性方程组2379 ACM Rank T able 模拟+排序1879 Tempus et mobilius Time and motion 模拟+组合数学->Polya定理1520 Scramble Sort 排序1634 Who's the boss? 排序2299 Ultra-QuickSort 排序->归并排序1008 Maya Calendar 日期处理1209 Calendar 日期处理2210 Metric Time 日期处理1430 Binary Stirling Numbers 日期处理1447 Ambiguous Dates 日期处理2080 Calendar 日期处理2351 Time Zones 时间处理1770 Special Experiment 树形DP1916 Rat Attack 数据结构->?1197 Depot 数据结构->Young T ableau1182 食物链数据结构->并查集2424 Flo's Restaurant 数据结构->堆1877 Flooded! 数据结构->堆1445 Random number 数据结构->碓1023 The Fun Number System 数论1061 青蛙的约会数论1091 跳蚤数论1152 An Easy Problem! 数论2191 Mersenne Composite Numbers 数论2381 Random Gap 数论2417 Discrete Logging 数论1510 Hares and Foxes 数论1641 Rational Approximation 数论1730 Perfect Pth Powers 数论1777 Vivian's Problem 数论2061 Pseudo-random Numbers 数论1014 Dividing 数论/DP?/组合数学->母函数?1606 Jugs 数论/搜索1995 Raising Modulo Numbers 数论->大数的幂求余2115 C Looooops 数论->解模线性方程1288 Sly Number 数论->解模线性方程组1395 Cog-Wheels 数学->解正系数的线性方程组1000 A+B Problem 送分题1003 Hangover 送分题1004 Financial Management 送分题1006 Biorhythms 送分题1007 DNA Sorting 送分题1016 Numbers That Count 送分题1019 Number Sequence 送分题1028 Web Navigation 送分题1046 Color Me Less 送分题1053 Set Me 送分题1068 Parencodings 送分题1071 Illusive Chase 送分题1096 Space Station Shielding 送分题1099 Square Ice 送分题1102 LC-Display 送分题1107 W's Cipher 送分题1119 Start Up the Startup 送分题1218 THE DRUNK JAILER 送分题1245 Programmer, Rank Thyself 送分题1247 Magnificent Meatballs 送分题1250 T anning Salon 送分题1298 The Hardest Problem Ever 送分题1326 Mileage Bank 送分题2190 ISBN 送分题2196 Specialized Four-Digit Numbers 送分题2291 Rotten Ropes 送分题2304 Combination Lock 送分题2309 BST 送分题2390 Bank Interest 送分题2403 Hay Points 送分题1411 Calling Extraterrestrial Intelligence Again 送分题1481 The Die Is Cast 送分题1484 Blowing Fuses 送分题1517 u Calculate e 送分题1547 Clay Bully 送分题1563 The Snail 送分题1604 Just the Facts 送分题1657 Distance on Chessboard 送分题1658 Eva's Problem 送分题1663 Number Steps 送分题1677 Girls' Day 送分题1690 (Your)((Term)((Project))) 送分题1775 Sum of Factorials 送分题1870 Bee Breeding 送分题2105 IP Address 送分题2136 Vertical Histogram 送分题1555 Polynomial Showdown 送分题(非常阴险) 2388 Who's in the Middle 送分题(排序)1519 Digital Roots 送分题(位数可能很大)1045 Bode Plot 送分题(用物理知识)2051 Argus 送分题(最好用堆,不用也可以过) 1011 Sticks 搜索1020 Anniversary Cake 搜索1054 The Troublesome Frog 搜索1069 The Bermuda Triangle 搜索1072 Puzzle Out 搜索1100 Dreisam Equations 搜索1110 Double Vision 搜索1111 Image Perimeters 搜索1128 Frame Stacking 搜索1142 Smith Numbers 搜索1162 Building with Blocks 搜索1183 反正切函数的应用搜索1184 聪明的打字员搜索1248 Safecracker 搜索1601 Pizza Anyone? 搜索1713 Divide et unita 搜索1129 Channel Allocation 搜索(图的最大独立集)1190 生日蛋糕搜索/DP1691 Painting A Board 搜索/DP1714 The Cave 搜索/DP1084 Square Destroyer 搜索?1010 STAMPS 搜索+DP1194 HIDDEN CODES 搜索+DP1882 Stamps 搜索+DP1101 The Game 搜索->BFS1137 The New Villa 搜索->BFS1233 Street Crossing 搜索->BFS2243 Knight Moves 搜索->BFS2312 Battle City 搜索->BFS1476 Always On the Run 搜索->BFS1480 Optimal Programs 搜索->BFS1482 It's not a Bug, It's a Feature! 搜索->BFS 1753 Flip Game 搜索->BFS1915 Knight Moves 搜索->BFS1017 Packets 贪心1018 Communication System 贪心1323 Game Prediction 贪心1463 Strategic game 贪心1469 COURSES 贪心1719 Shooting Contest 贪心2054 Color a Tree 贪心1328 Radar Installation 贪心(差分约束系统的特例)1042 Gone Fishing 贪心/DP1752 Advertisement 贪心/图论->差分约束系统1201 Intervals 贪心/图论->最长路->差分约束系统1097 Roads Scholar 图论1161 Walls 图论1450 Gridland 图论(本来TSP问题是NP难的,但这个图比较特殊,由现成的构造方法)2197 Jill's Tour Paths 图论->2416 Return of the Jedi 图论->1639 Picnic Planning 图论->1695 Magazine Delivery 图论->1729 Jack and Jill 图论->1751 Highways 图论->1122 FDNY to the Rescue! 图论->Dijkstra1125 Stockbroker Grapevine 图论->Dijkstra1135 Domino Effect 图论->Dijkstra1394 Railroad 图论->Dijkstra1158 TRAFFIC LIGHTS 图论->Dijkstra变形2395 Out of Hay 图论->Dijkstra变形2253 Frogger 图论->Dijkstra变形(和1295是一样的)1734 Sightseeing trip 图论->Euler回路1466 Girls and Boys 图论->n/a1515 Street Directions 图论->把一个无向连通图改造成为有向强连通图1635 Subway tree systems 图论->不同表示法的二叉树判同1275 Cashier Employment 图论->差分约束系统->无负权回路的有向图的最长路->Bellman-Ford1274 The Perfect Stall 图论->二分图的最大匹配1325 Machine Schedule 图论->二分图的最大匹配2239 Selecting Courses 图论->二分图的最大匹配2195 Going Home 图论->二分图的最大权匹配2400 Supervisor, Supervisee 图论->二分图的最大权匹配?1637 Sightseeing tour 图论->欧拉回路1383 Labyrinth 图论->树的最长路1094 Sorting It All Out 图论->拓扑排序1486 Sorting Slides 图论->拓扑排序1149 PIGS 图论->网络流2289 Jamie's Contact Groups 图论->网络流?1192 最优连通子集图论->无负权回路的有向图的最长路->BellmanFord 1364 King 图论->无负权回路的有向图的最长路->BellmanFord1985 Cow Marathon 图论->有向无环图的最长路1087 A Plug for UNIX 图论->最大流1273 Drainage Ditches 图论->最大流1459 Power Network 图论->最大流1632 Vase collection 图论->最大完全图2049 Finding Nemo 图论->最短路1251 Jungle Roads 图论->最小生成树2421 Constructing Roads 图论->最小生成树1026 Cipher 组合数学1095 Trees Made to Order 组合数学2346 Lucky tickets 组合数学1286 Necklace of Beads 组合数学->Polya定理2409 Let it Bead 组合数学->Polya定理1664 放苹果组合数学->递推。