Economic regulation of quality in electricity distribution networks

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:278.07 KB

- 文档页数:11

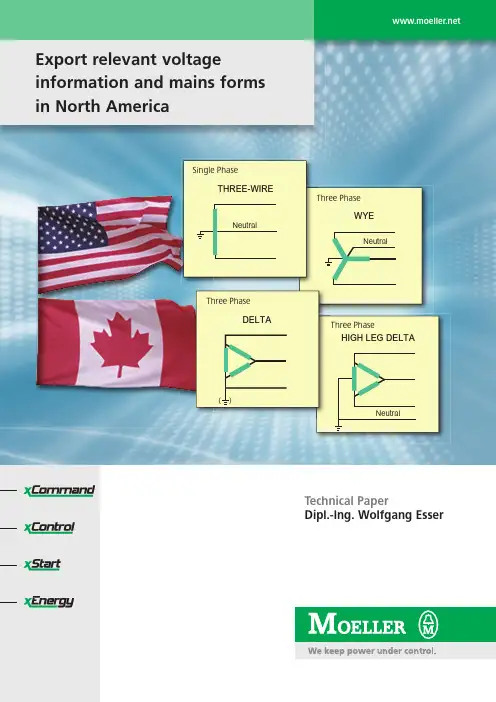

NeutralHIGH LEG DELTAThree PhaseNeutralWYEThree PhaseT NeutralTHREE-WIRESingle PhaseDELTAThree Phase( )Export relevant voltageinformation and mains forms in North AmericaAn earlier compilation of the normal mains forms and conventional voltages in North America show a multitudeof local variations. This is due to the historical structure, but also with the huge dimensions of the continent, the distances between energy resource locations and load centres and the high current demands and the individual needs of power suppliers. With sucha multiplicity it is impossible to deal economically as well as technically. The standard ANSI1 C84.1 has brought a large reduction in conventional voltages and is a clear example of the revising effects of standards. The standard had the task of coordinating the differing interests of the energy producers and distributors on the one side and the electricity consumer on the other side, e.g. by the determination of tolerances. Whereas the energy production, energy trading and distribution was in the past in one hand, today they are mostlythe responsibility of various company groups each with their own business interests.There are still today in America regional differences of energy production.The exporting supplier of machinesor systems (OEM2) with associated electrical equipment should quickly and bindingly discuss the network conditions with the final system user. The mains system voltage as well as the mains system form have an influence on the selection and use of the switching and protection devices. Delta mains systems or unearthed star-delta mains systems exclude some modern, European solutions. Specialist as well as non-experts are dependant upon the correct voltage details.Selection of the correct voltage in North America is not only too much for many holiday makers, but also with specialists there is often doubts with the exporting of machines and systems. This is due to the fact that different voltage details are often given (Service Voltage or Utilization Voltage, Nominal System Voltage or Rated Voltage and finally the Motor Nameplate Voltage), that we do not differentiate in the IEC world.In the IEC world, from production to1A NSI = American National Standards Institute, Inc, /2 OEM = Original Equipment Manufacturer use, we talk about operting voltageand assume the compliance with thetolerance for voltage drop. In Germanythe voltage is an electrical parameterthat we do not need to think too muchabout.This essay is concerned exclusively withlow voltages in public and industrialmains systems and their suppliedcommercial and industrial equipment.It details extracts of importantinformation for the project engineersof companies exporting to America.Binding information is detailed in…American National Standard forElectric Power Systems and Equipment– Voltage Ratings (60 Hertz), ANSIC84.1-2006“ or for Canada the CSA3Standard …CAN-3-C235-83“.Service Voltage andUtilization VoltageIn this essay only the low voltagerange is considered. In North Americathat includes all voltages with a valueof up to 1000 V (Increased to 1200 Vby ANSI C84.1-2006). Above 1000 V(1200 V) is called medium voltageand high voltage. Only AC voltagesare considered that can also appearas AC systems. The rated frequencyfor all voltages is uniformly 60 Hz.All described voltages and tolerancesare for continuous operation withoutconsideration of short-time alterationsdue to switching processes or thestart-up of large motors. Heavyor long start-up drives can lead inindividual cases to the necessity forspecial starting types and conductordimensions to maintain the specifiedtolerances.Whereas in the IEC world wework with the uniform descriptionoperating voltage (comparable inAmerica: Nominal System Voltage orRated Voltage), in North America itis differentiated between differentlynamed voltages in the distribution/supply network and in the consumersystem. The Service Voltage is thevoltage in the supply network.Their tolerances must be especially3C SA = Canadian Standards Association,/maintained at the delivery pointsof the energy supply company´sconductors and the conductors of theend user. That is, house connectionboxes (point of connection, point ofcommon coupling). The electricitysupply company is responsible forthe quality of this voltage. The actualService Voltage is normally between 95... 105 % of it´s nominal voltage. Whenconsidering the voltage tolerance itmust be taken into account that inlarge american states there are morespur conductor system instead ofcompact network mains systems thatallow a higher supply safety and ahigher voltage stability.The Utilization Voltage is the voltage inthe consumer´s mains system, especiallythe effective voltage at the connectionpoint of the equipment. The UtilizationVoltage can fluctuate in the worst casebetween 87 ... 106 % of the ratedvoltage. The difference between theminimum Service Voltage and theminimum Utilization Voltage is thepermitted value of the Voltage dropinside the consumer system. The systemoperator and the electrical installerare responsible for the quality of thisvoltage by his correct dimensioning ofthe conductors. The permissable 5 %maximum voltage drop according toNEC4(Feeder Circuit + Branch Circuit)is normally divided between a voltagedrop of 3 % up to the incomer (FeederCircuit) and 2 % for the consumerinstallation (Branch Circuit).With the tolerance of both voltages wedecide between an ideal level (Range A)and a still tolerable level (Range B).Voltages in the Range B should belimited in the frequency as well as theduration of their occurrance. There ishowever no binding specification forthis limitation as well as for theoccurrence of voltages outside Range B.The tolerances can be especiallycritical due to larger voltage drops orheavy load fluctuations in lightlyinterconnected networks with longspur connections.With AC systems there can, as well asthe tolerance of the voltage amplitude,appear a Voltage Unbalance between4 NEC = National Electrical Code23the individual phases or the phases and a possibly existing neutral conductor. The voltage unbalance without load must not be more than 3 % according to ANSI C84.1. It could be considered with a derating factor for the motor capacity according to Appendix D of ANSI C84.1, that for example, a 3 % voltage unbalance is rated with 0.9. The voltage unbalance is determined:Voltage unbalance [%] =100 ×(max. difference from the average voltage) (average voltage)Example:The measured voltage (phase to phase) is 230 V, 232 V and 225 V. The average is 229 V and the largest difference from the average is 4 V. In this example the voltage unbalance is 1.75 %.With motors, a voltage unbalance leads also to a current unbalance. Here the use of a device with IEC phase-failure sensitivity for the protection of the motor is especially attractive. Table 1 shows the principle effect of differences of the actually connected operating voltage from the rated voltage for AC motors.A survey of the EPRI 5 shows that most typical end consumers have daily voltage fluctuations of ≤ 3 %. At the same time more than 10 % of the end consumers has a voltage fluctuation of ≥ 7 % that can be outside RangeB [1]. In 98 % of the network the voltage unbalance is ≤ 3 % and in 66 % of the network is ≤ 1 %.The end consumer can, other than by energy awareness, have nearly no influence over the quality of the electrical supply. Load fluctuations, long supply cables and own power generation outside the influence of the electrical supply companies make voltage regulation, also for the supply companies, to a daily challenge. Frequent and longer differences should be reported to the electricity supply company so that they can have a better overview and can5EPRI = Electric Power Research Institutereact to the fluctuations. The energy supply company have their expansion planning and regulation measures aggravated by ever changing targets. Private voltage regulation equipment in consumer systems with sensitive equipment is often necessary. Thenormal division in America into Service Voltage and Utilization Voltage is also very much a question of competence and responsibility for the quality of the voltages.Nameplate VoltageAlso in North America it is normal that for motors and switching and protection devices for motors the operating voltage is given on therating plate for which the equipment is designed. This operating voltage is with motors known as Nameplate Voltage . It is noticable and confusing that this voltage does not agree with the nominal mains voltage. The Nameplate Voltage is equal to the minimum service voltage, this means that the motor equiment is nearly never operatedwith the nominal voltage of the mains. Therefore the operating currents of the protection devices can be better determined and the permissablevoltage tolerance can be better utilized. The catalogues of various switchgearmanufacturers and the rating plates of switching and protection devices give inconsistantly either the Nameplate Voltage (simpler for the user) or the nominal system voltage (mains voltage). Picture 1 shows a nameplate from a Moeller contactor. As well as the nominal mains voltage the Motor Nameplate Voltage is also given here. The power details correspond to the NEMA power of motors. The electrical testing of the switchgear is carried out with the higher nominal mains voltage = rated operating voltage, plus the specified tolerances. A degree of help with device selection is offered by the normal American NEMA sizes of the equipment and switchgear combinations. Table 2 shows the tolerances of the described network voltages.The Utilization Voltage (permissable voltage at the connection point of the equipment), according to Table 3, is not identical with the normal operating voltage of the motor (Nameplate Voltage s), nor withNEMA 6 permissable voltage tolerances on the equipment. Especially with small and sensitive AC equipment6N EMA = National Electrical Manufacturers Association, /Table 1: General effects of differences of the operating voltage from the rated voltage for AC motors. Neither undervoltage nor overvoltage has an especially positive effect, there-fore smallest possible tolerances should be strived for.4c dTable 2: Tolerances of Service Voltage and Utilization Voltage, with examples for the most important voltage in the USA, 480 V , 60 Hz.Table 3: The most important nominal mains voltages and the allocated Nameplate Voltages (operating voltages) of the equipment. Also the tolerance band width and the permissableabsolute voltage values are shown.(electric razors, computers, etc.) wide range adapters are especially sensible. Often, uninteruptable power supplies (UPS) are necessary for data safety for computers and automation systems.Note concerning the acceptance of European switchgear when exporting to North America:By export motors are often used that are dimensioned in kW. The inspector may then recalculate the kW value into HP and then dimension the conductor using the current of the next largest standard HP motor. This method can lead to the use of larger cross sections than is necessary for the actual current flowing.Short-circuit Power and Short-circuit current in North AmericaThe north American mains networks are mostly softer as the European mains networks, as the transformers often have a higher impedance voltage of up to 7 %. With the calculation for larger consumer systems the different impedance voltage should be taken into account with the short-circuit calculations. With higher impedance voltages of the power transformer the maximum short-circuit current is less than with smaller short-circuit voltages. In the IEC area normally only the secondary short-circuit current of the transformer is found in thetransformer short-circuit current tables. In american tables higher currents are given that take into account extra feedback currents from motors that are also connected to the short-circuited network. It is also normal to havedetails of values for differing, potential short-circuit currents that could appear on the transformor primary side. The american tables are more complex and contain more selection criteria. The table 4 shows, from a IEC basis, reference values for short-circuitcurrents for american voltages and with unlimited primary-side short-circuit power.Mains systems in North America Normally the type of network is not so important for the electrical consumerPicture 1: Example of the voltage details for North America on the rating plate of a Moeller contactor. The nominal mains voltage and the motor Nameplate voltages are given.5as the voltage. The type of network has a bearing on the possible use of differing protection measures against electrical shock and if there is at all a neutral conductor present. Therefore the type of mains determines thesingle phase voltage of the equipment that must, if necessary be connected between two phases. With the export of electrical systems it is alwayssensible, especially when the available mains configurations cannot be safely clarified (e.g. with serial machines) to install input transformers (power transformer) into the system so as not to be dependant upon the availability, or not, of a neutral conductor in the local mains system. Single phase equipment can then be connected in it´s own single phase system with neutral conductor. As described later, it must be considered with the selection of switching and protection devices for AC equipment that devices designed to IEC or EN are approved only for use in an earthed network with neutral conductor due to their clearance and creepage dimensions (e.g. UL 508 Type E motor starter, UL 508 Type F motorstarter). Also with AC networks an adapter transformer can be installed in the incoming conductor of the machine. The transformer allows, for example the construction of a star-delta network for the machine so that devices can be used that require such a network. However due to economic reasons this is only possible up to a certain rating.The mains types, in Picture 2, are also shown to make clear that in north America it is possible to come across interlinked voltages that areTable 4: Rated currents and reference values for short-circuit currents of North American power transformers.I k ‘‘ = Transformor start-short-circuit current when connected to a network with unlimited short-circuit power.not connected, as is normal in most countries, with the normal factor √ 3, for a 120° phase difference. Some mains types are only found in north America. Picture 1 doesn´t evaluate the quantitative distribution of the shown mains types, however today mostly earthed networks are found. (It should be considered that the earth potential is not always distributed from a cenral point but from several earthing points. This canlead to differing voltages between the earthing points.)➊ shows the predomanent form of single phase networks. Occasionlly unearthed single phase networks appear. The nominal mains voltage in single phase networks is mostly 120 V and the connected equipment should have an operating voltage or Nameplate Voltage of 115 V. Network ➋ gives two single phase systemswithout mutual phase difference, with normally twice 120 V or with 240 V between both phases.Earthed networks ease generally the use of protection measures that switch off the power (switching off protection measures). In consumer systems e.g. in the automobile industry, also in north America unearthed IT networks are found that ensure that the first isulation fault does not lead todisconnection due to the protection device (higher power availability and system availability in straight forward electrical installations). The first fault in the IT system is signalled by an insulation monitor and can be cleared during a break in operations.Picture 2: Network types in north America, without evalution of the frequency of use. Only the secondaries of the transformers are shown in this picture. With circuits 5 and 6 the earthing can take place in the middle of a winding (see diagram) or alternatively at a corner. Single phase equipment can be connected to a single phase system or on a three system between two phases or, when present, between phase and neutral con-ductor.6A further, second fault causes a normal disconnection of the power supply. A variant of this network is the earthing of the star point with a, sometimes settable, high ohmic impedance that limits the size of the earth-fault current. The presence and the size of the earth-fault current can, for example, be monitored with a current transformer for signalling and protection purposes.In the USA mostly networks up to 480 V 60 Hz are used and in Canada networks up to 600 V 60 Hz can be found. The machine exporter often has a problem determining the local mains system type. With some types of switchgear shown in the Moeller main catalog and the publication [1] it is important to note that these switching and protection devices are exclusively approved for use with earthed starnetworks. Therefore some devices must be used exclusively in networks with 600Y / 347 V AC or 480Y / 277 V AC (networks with slash voltages 7) (Picture 3). Information concerning this can also be found on the rating label of the product.7T he slash is the slash between the star and delta voltage – it gives the voltage it´s namePicture 3: Many of the switching and protection devices from Moeller have been especially designed for the requirments of the American markets. They can however be used also in countries where IEC standards must be used. Important project engineering information shows the usual voltage and type of network in the field of operation.When the mains system type is not clear an alternative must be used that can also be a delta network with the full voltage. When this limitation only applies to a few devices the following is possible:Use larger • NZM circuit-breaker instead of smaller FAZ-NA circuit-breakerUse • motor-protective circuit-breaker with group protection upstream protective device instead of compacter Type E or Type F motor starters.(then for example, with busbar systems the requirements of the assembly in branch are can be fulfilled)Use the larger • NZM2 circuit-breaker in certain current ranges instead of the more compact NZM1.Switchgear for export and for retroactive voltage conversion. Increasingly there is the problem that machines or total production lines are transfered to a location with completely different voltage and/or frequency relationships. Moeller offers contactors with different types of coils to simplifythe later conversion to alterations in voltage and frequency or to reduce the stocking levels and variants of the switchgear panel builder. Moeller recommends the solution that with a change of location the control voltage of the total system is supplied from control voltage transformer. At one time double frequency coils were offered that could be used for the same voltage at 50 and 60 Hz. Thiscompromise, due to a small over power in the contactor when used in 50 Hz networks, lead to a life span deduction of approx. 30 %. To be recommended are the double voltage coils that can be used for a 50 Hz standard voltage and are at the same time optimal for a second 60 Hz standard voltage. With a system designed for 230 V, 50 Hz the control transformer would be exchanged and the system would then be supplied with a control voltage of 240 V, 60 Hz (using Moeller contactors with double voltage coils). For use in north America Moeller recommends the use of a centrally produced control voltage of 120 V 60 Hz. For this contactors with the double voltage 110 V 50 Hz / 120 V 60 Hz are offered. Alternatively there are also singlevoltage coils for 115 V 60 Hz. Normally, approved control voltage transformers have an extra primary tapping so that the control voltage can be matched to the local voltage conditions. Moeller new generation contactors xStart [3] have additionally a minimum safe operating range between 0.8 and 1.1 x U c . As well as the mentioned adaption of the control voltage the complete machine switchgear must be investigated for necessary modifications (altered motor currents / protection devices, effect of altered motor speed, etc.)Especially according to the demands of the American semi-conductor manufacturer Moeller offers a range of contactors according to the specification SEMI F478 withincreased voltage safety for especially breakdown critical switchgear. These contactors drop out firstly at 30 % of the control voltage (picture 4) and can be used in other branches with an especially high demand on system availability.8Picture 4: The American semi-conductor industry demands an increased drop-out safety for contactor coils according to the guidelines SEMI F47. In the green area the contactor con-tacts must not open. These demands can be exceded with the special contactors DIL MF from the Moeller xStart system.However the voltage conversion is only a part of the conversion of a switchgear system. It must also be noted thata 50 Hz IEC switchgear system has other differences from a 60 Hz north American system that must be altered [2]. All components must be approved and also, for example, approved wiring material must be used. It must be checked that the equipment currents agree with the appropriate settings of the protection devices. The protection of the control voltage transformerand the control circuit is covered in a seperate essay [4].Literature:[1] P ower Quality Notes, Edition No. 7,February 2005h ttp://[2] W olfgang Esser“Besondere Bedingungen für denEinsatz von Motorschutzschalternund Motorstarten in Nordamerika”Moeller GmbH, Bonn, 2004V ER1210-1280-928D,Article No.: 267951D ownload: Quicklink ID:928de at WolfgangEsser“Special considerations governing theapplication of Manual Motor Controllersand Motor Starters in North America”Moeller GmbH, Bonn, 2004V ER1210-1280-928GB,Article No.: 267952D ownload: Quicklink ID:928en at [3] Wolfgang Esser“xStart – Die neue Generation:100 Jahre Moeller Schütze –konsequenter Fortschritt”Moeller GmbH, Bonn, 2004VER2100-937D, Article No. 285551D ownload: Quicklink ID:937de at WolfgangEsser“xStart – The new Generation:100 Years of Moeller contactors –Continuous Progress”Moeller GmbH, Bonn 2004VER2100-937GB, Article No. 285552D ownload: Quicklink ID:937en at [4] Wolfgang Esser“Motorstarter und ‘Special PurposeRatings, für den nordamerikanischenMarkt“Moeller GmbH, Bonn 2006VER1200+2100-953DDownload:QuicklinkID:953de at WolfgangEsser“Motor starters and ‘Special PurposeRatings, for the North American market”Moeller GmbH, Bonn 2006VER1200-2100-953GBDownload: Quicklink ID:953en at [5] Wolfgang Esser“Schutz von Steuertransformatorenund Stromversorgungsgeräten für denEinsatz in Nordamerika”Moeller GmbH, Bonn 2005VER1210-951D, Article No. 105221D ownload: Quicklink ID:951de at WolfgangEsser“Protection of Control Transformers foruse in North America”Moeller GmbH, Bonn 2005VER1210-951GB, Article No. 105222D ownload: Quicklink ID:951en at 7Moeller addresses worldwide:/addressE-Mail: info@Internet: Issued by Moeller GmbHHein-Moeller-Str. 7-11D-53115 Bonn© 2007 by Moeller GmbHSubject to alterationsVER4300-965en ip 02/08Printed in Germany (02/08)Artikelnr.: 116835X tra CombinationsXtra Combinations from Moeller offers a range of products and services, enabling the best possible combination options for switching, protection and control in power distribution and automation.Using Xtra Combinations enables you to find more efficient solutions for your tasks while optimising the economic viability of your machines and systems.It provides:■ flexibility and simplicity■ great system availability■ the highest level of safetyAll the products can be easily combined with one another mechanically, electrically and digitally, enabling you to arrive at flexible and stylish solutions tailored to your application – quickly, efficiently and cost-effectively.The products are proven and of such excellent quality that they ensure a high level of operational continuity, allowing you to achieve optimum safety for your personnel, machinery, installations and buildings.Thanks to our state-of-the-art logistics operation, our com-prehensive dealer network and our highly motivated service personnel in 80 countries around the world, you can count on Moeller and our products every time. Challenge us!We are looking forward to it!。

电力技术英语电力英语词汇(一)1 能源与动力导论电力工业构成 com position of electric power in2 dustry缺 电 electric-power shortage电气化程度 electrification rete清洁能源 clean energy res ources能源经济区划 regional economic programming based on energy res ources电力弹性系数 elasticity of demand for electricity 动力系统 combined power and heat system工业生产电气装备水平 degree of electrification of industrial production equipment2 电力系统概论统一电力系统 unified electric power system联合电力系统 interconnected power system主干网络 main grid网 架 netw ork frame电磁环网 ring netw ork with inter-trans former矿口电厂 mine-m outh power plant孤立电厂 is olated power plant腰荷电厂 cycling plant(unit),mid-range load capacity可切负荷 interruptible load负荷同时率 load coincidence factor备用容量和备用容量系数 reserve capacity and reserve margin热备用,运转备用 hot reserve,spinning re2 serve可控静止无功补偿 controllable static var com2 pensation非全相运行 open-phase operation系统失步 loss of system synchronism系统解列 power system splitting进相运行 under-excitation operation装机容量年利用小时和容量因数 installed ca2pacity utilization hours and capacity factor原则接线图 principal system connection diagram 3 电力系统调度运行电力系统调度及其分级管理 power system dis2 patch and its hierarchical administration可调小时(出力) feasible hours(capacity)年发电最大负荷利用小时 yearly maximum us2 able hours of unit发电厂最小技术出力 minimum load of power plant频率调差系数 frequency regulation coefficien第一(二)调频厂 main(auxiliary)frequency regulation plant等微增率准则 equal incrementel cost rule快速切速故障 fast fault-clearing切除负荷 load rejection切机和远方切机 switch off generator and rem ote switch off generator快速调相改发电 fast changing from condenser m ode to generator m ode电力系统中性点接地方式 power system neutral grounding单元接线方式 block connection冲击合闸 full v oltage switching on自同步并列 self-synchronizing准同步并列 synchronizing强送电 forced energization有名制 system of units标么制 per-unit system平均供电可用度指标 average service availability index网损电量(网损) transmission losses in energy (netw ork loss)功率强制分布 power flow forced distribution人工稳定区 artificial stability region(段一雄 编摘)75电力英语词汇© 1995-2004 Tsinghua Tongfang Optical Disc Co., Ltd. All rights reserved.。

regulation例句1. The new regulation aims to improve air quality in urban areas.2. There are strict regulations governing the use of pesticides in agriculture.3. Compliance with safety regulations is mandatory for all construction sites.4. The regulation restricts the amount of plastic waste produced by businesses.5. New financial regulations have been introduced to prevent fraud.6. The regulation requires companies to disclose their carbon footprints annually.7. He was fined for violating environmental regulations.8. The government is reviewing regulations related to data privacy.9. There is an ongoing debate about the effectiveness of the current regulation.10. The regulation was designed to enhance consumer protection in the marketplace.11. Many businesses struggle to adapt to the new regulations swiftly.12. Public health regulations enforce hygiene standardsin restaurants.13. The regulation was implemented to reduce the risk of workplace accidents.14. Changes to the regulation sparked protests from local communities.15. The organization advocates for more stringent animal welfare regulations.16. The regulation bans the sale of certain hazardous materials.17. A review of the regulation showed that it needed significant updates.18. The regulation provides guidelines for sustainable fishing practices.19. There are exemptions in the regulation for small businesses.20. The regulation has positive implications for the renewable energy sector.21. Stakeholders were invited to discuss the proposed changes to the regulation.22. The regulation's goal is to promote fair trade practices.23. Many citizens praised the new regulation for its environmental benefits.24. The regulation imposes penalties for non-compliance.25. The local council is working on a regulation to control noise levels.26. International regulations are necessary for preventing climate change.27. The regulation will come into effect starting next year.28. Compliance with the regulation is regularly monitored by authorities.29. The regulation seeks to balance economic growth and environmental sustainability.30. Legal experts are analyzing the implications of the new regulation.31. There’s a need for regulation in the rapidly evolving technology sector.32. The regulation encourages innovation while maintaining safety standards.。

如何改善城市英语作文Title: Enhancing Urban Living: Comprehensive Measures for Improving CitiesIn the epoch of rapid urbanization, cities have become the lifeblood of economies, cultures, and societies. However, this unprecedented growth has also led to numerous challenges, including pollution, congestion, social inequality, and a decline in quality of life. To address these issues and foster sustainable urban development, a multifaceted approach is imperative. This essay outlines specific measures aimed at improving cities, encompassing environmental sustainability, infrastructure development, social equity, economic vitality, and technological innovation.1. Environmental Sustainabilitya. Promoting Green Spaces and Urban ForestryCities should prioritize the creation and maintenance of green spaces such as parks, community gardens, and rooftop gardens. Urban forestry initiatives can increase tree cover, which not only enhances aesthetic appeal but also provides ecological benefits like air purification, temperature regulation, and noise reduction. Governments can incentivize private landowners to plant trees and support community-led greening projects.b. Enhancing Public Transportation and Encouraging Active TransportReducing reliance on private vehicles is crucial for lowering emissions. Expanding and improving public transportation systems, including buses, trams, and metro networks, can make commuting more efficient and eco-friendly. Additionally, promoting cycling and walking through the development of dedicated bike lanes and pedestrian pathways can significantly cut down on carbon footprints.c. Implementing Waste Management SolutionsEffective waste management strategies, such as recycling programs, composting initiatives, and strict enforcement of anti-littering laws, are essential. Cities should also explore waste-to-energy technologies and encourage industries to adopt circular economy principles, minimizing waste generation and maximizing resource efficiency.2. Infrastructure Developmenta. Smart Grid and Renewable Energy IntegrationUpgrading to smart grids can optimize electricity distribution, reduce energy losses, and facilitate the integration of renewable energy sources like solar and wind. This transition is vital for achieving energy independence and reducing reliance on fossil fuels.b. Water Management and ConservationCities must invest in advanced water treatment facilities and efficient water distribution systems to ensure clean, reliable water supplies. Water conservation measures, such as rainwater harvesting, greywater recycling, and public awareness campaigns, can help mitigate water scarcity issues.c. Housing and Urban PlanningMixed-use developments that integrate residential, commercial, and recreational spaces can reduce the need for long commutes and promote vibrant, walkable communities. Affordable housing policies should be implemented to address housing unaffordability and social segregation.3. Social Equitya. Access to Education and HealthcareEquitable access to quality education and healthcare services is fundamental for social cohesion and human development. Cities should invest in public schools and hospitals, ensuring they are well-equipped and staffed. Programs to support vulnerable groups, such as scholarships and subsidized healthcare, should be expanded.b. Inclusive Economic OpportunitiesCreating job opportunities for all residents, particularly those from marginalized communities, is crucial. Vocational training centers, small business incubators, and public-private partnerships can foster entrepreneurship and employment growth.c. Community Engagement and SafetyActive community engagement through public consultations, citizen assemblies, and neighborhood watch programs can strengthen social bonds and enhance public safety. Cities should prioritize the safety of women and girls, implementing measures like better lighting, public transportation safety, and responsive law enforcement.4. Economic Vitalitya. Diversifying the EconomyDiversifying the economic base can protect cities from external shocks, such as global economic downturns or industry-specific crises. Supporting emerging sectors like digital economy, green technologies, and creative industries can drive innovation and job creation.b. Fostering Entrepreneurship and Small BusinessesCities should provide resources and incentives for entrepreneurs and small businesses, including access to funding, mentorship programs, and regulatory support. This can stimulate economic growth and contribute to local job markets.c. Attracting Foreign Investment and TourismImproving city branding, infrastructure, and regulatory environments can attract foreign direct investment and tourism, boosting the local economy. Cities should showcase their cultural heritage, modern amenities, and business-friendly policies to potential investors and tourists.5. Technological Innovationa. Smart City TechnologiesAdopting smart city technologies, such as IoT (Internet of Things), AI (Artificial Intelligence), and big data analytics, can optimize city operations, enhance citizen services, and improve resource management. Examples include smart lighting, waste management systems, and predictive maintenance for public infrastructure.b. Digital InclusionEnsuring universal access to high-speed internet and digital literacy programs can bridge the digital divide, empowering citizens to participate fully in the digital economy and society. Public libraries, community centers, and schools can serve as hubs for digital education and connectivity.c. Cybersecurity MeasuresAs cities become increasingly interconnected, cybersecurity threats also rise. Implementing robust cybersecurity frameworks, regular audits, and public awareness campaigns are essential to protect sensitive data and critical infrastructure.ConclusionImproving cities requires a holistic approach that addresses environmental, infrastructural, social, economic, and technological dimensions. By prioritizing sustainable practices, investing in infrastructure, promoting social equity, fostering economic vitality, and harnessing technological innovation, cities can become more livable, resilient, and prosperous. Governments, private sectors, and communities must collaborate to turn these aspirations into reality, ensuring that urbanization serves as a catalyst for progress rather than a source of problems. Through collective effort and vision, we can build cities that not only meet the needs of today but also pave the way for a sustainable and inclusive future.。

自动驾驶汽车的利与挑战英语作文Title: The Benefits and Challenges of Autonomous VehiclesIntroductionIn recent years, autonomous vehicles (AVs) have emerged as a transformative force in the automotive industry. Theseself-driving cars have the potential to revolutionize transportation, offering a host of benefits while also presenting a number of challenges. This essay explores the advantages and drawbacks of autonomous vehicles, highlighting their impact on society and the economy.Benefits of Autonomous VehiclesOne of the key benefits of AVs is their potential to improve road safety. Human error is a leading cause of traffic accidents, but AVs are designed to eliminate the risk of driver-related errors. By relying on advanced sensors and artificial intelligence, these vehicles can react to changing road conditions with unparalleled speed and accuracy, reducing the likelihood of collisions.Moreover, AVs have the potential to increase accessibility for individuals with disabilities and the elderly. These populations often face barriers to mobility, but autonomous vehicles could provide them with a safe and convenient means oftransportation. By offering door-to-door service and customizable features, AVs could enhance the quality of life for those who are unable to drive themselves.In addition, autonomous vehicles have the potential to reduce traffic congestion and emissions. Through coordinated networks and optimized routing, AVs could streamline traffic flow and minimize delays. Furthermore, by promoting the use of electric vehicles and alternative fuels, AVs could help mitigate the environmental impact of transportation and contribute to a more sustainable future.Challenges of Autonomous VehiclesDespite their potential benefits, autonomous vehicles also present a number of challenges that must be addressed. One of the primary concerns surrounding AVs is their cybersecurity vulnerabilities. As these vehicles rely on interconnected systems and data, they are susceptible to hacking and cyber attacks. Ensuring the security and integrity of AVs is crucial to prevent potential risks to passenger safety and privacy.Another challenge facing autonomous vehicles is regulatory and ethical issues. The development of AV technology is outpacing the establishment of clear guidelines and legal frameworks. Questions about liability, insurance, and dataprivacy remain unresolved, raising concerns about the accountability and ethical implications of autonomous vehicles. Policymakers and stakeholders must work together to establish comprehensive regulations that address these complex issues.Moreover, the widespread adoption of AVs could havefar-reaching implications for the economy and workforce. As self-driving technology becomes more prevalent, traditional jobs in the transportation sector may be at risk. Drivers, mechanics, and other industry professionals could face displacement or retraining as autonomous vehicles replace manual labor. Addressing the economic impact of AVs will require proactive strategies to support affected workers and industries.ConclusionIn conclusion, autonomous vehicles have the potential to revolutionize transportation and offer numerous benefits to society. From improved road safety to increased accessibility, AVs have the capacity to transform the way we travel and interact with our environment. However, realizing the full potential of autonomous vehicles will require addressing a range of challenges, including cybersecurity, regulation, and economic disruption. By collaborating across sectors and prioritizing safety and sustainability, we can harness the power of autonomousvehicles to create a safer, more efficient, and more inclusive transportation system for the future.。

大城市过度发展的影响英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1The Detrimental Impacts of Unchecked Urban SprawlAs a student living in a major metropolitan area, I have witnessed firsthand the relentless march of urbanization. While economic growth and development are crucial for a city's prosperity, the pace at which our cities are expanding has become a cause for grave concern. Unrestrained urban sprawl, driven by a voracious appetite for land and resources, is exacting a heavy toll on our environment, public health, and overall quality of life.One of the most visible consequences of urban sprawl is the encroachment on natural habitats and green spaces. As cities spread their tentacles into previously undeveloped areas, vast swaths of forests, wetlands, and farmlands are being paved over to make way for residential complexes, commercial districts, and transportation infrastructure. This unbridled land consumption is not only robbing us of the ecological services provided by thesenatural environments but also contributing to a alarming loss of biodiversity.The impacts of urban sprawl extend far beyond the destruction of natural habitats. The dominance of car-centric urban planning and the ever-increasing distances between residential areas, workplaces, and amenities have given rise to a culture of heavy reliance on personal vehicles. The resultant surge in vehicular emissions has enveloped many cities in a noxious blanket of air pollution, posing severe risks to public health.As a student, I am deeply concerned about the long-term consequences of breathing polluted air. Numerous studies have established links between exposure to air pollutants and a range of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, as well as an increased risk of certain types of cancer. The situation is particularly dire for children and the elderly, whose developing and compromised respiratory systems, respectively, render them more vulnerable to the deleterious effects of air pollution.Beyond its environmental and health impacts, urban sprawl has also contributed to the erosion of community cohesion and social fabric. The sprawling, disconnected nature of modern cities has led to a fragmentation of neighborhoods and adiminution of public spaces where people can congregate and interact. This lack of social interaction and community engagement can breed a sense of isolation and disconnection, particularly among marginalized groups and the elderly.Moreover, the lengthening of commute times due to urban sprawl has eaten into the precious hours that could have been devoted to family, leisure, or personal growth. The stress and fatigue associated with long commutes can take a significant toll on mental and physical well-being, further compounding the public health challenges posed by urban sprawl.It is imperative that we acknowledge the gravity of these issues and take decisive action to curb the adverse effects of unchecked urban growth. One crucial step is to prioritize sustainable urban planning strategies that emphasize compact, mixed-use development and the integration of green spaces within the urban fabric. By creating walkable, transit-oriented communities, we can reduce our reliance on personal vehicles and foster a more environmentally friendly and socially cohesive way of living.Additionally, we must invest in robust public transportation systems that offer convenient and affordable alternatives to driving. Encouraging the use of mass transit not only alleviatestraffic congestion and air pollution but also promotes a sense of community and fosters social interactions among diverse groups of people.Furthermore, it is essential to protect and preserve existing natural areas within and around cities. These green spaces not only serve as critical habitats for wildlife but also provide invaluable recreational opportunities and contribute to better air quality and temperature regulation in urban environments.Ultimately, the path towards sustainable urban development requires a collective effort involving policymakers, urban planners, businesses, and citizens alike. We must embrace a mindset that prioritizes long-term sustainability over short-term gains and recognizes the intrinsic value of preserving our natural environments and fostering vibrant, cohesive communities.As students and future leaders, it is our responsibility to advocate for these changes and hold our elected officials accountable for implementing policies that promote responsible urban growth. We must raise awareness about the detrimental impacts of urban sprawl and inspire our peers to adopt more sustainable lifestyles and consumption patterns.The challenges posed by unchecked urban sprawl may seem daunting, but inaction is not an option. The future of our cities,and indeed our planet, hinges on our ability to strike a balance between development and environmental stewardship. By embracing sustainable urban planning principles and fostering a renewed appreciation for the natural world, we can create cities that are not only economically prosperous but also livable, healthy, and ecologically resilient for generations to come.篇2The Unchecked Growth of Metropolises: A Cause for ConcernAs a student residing in the heart of a bustling metropolis, I have witnessed firsthand the relentless expansion and development that has enveloped our city skylines. Towering skyscrapers have risen like concrete giants, casting shadows upon the remnants of our once-cherished urban landscapes. While progress is often heralded as a beacon of prosperity, the unchecked growth of our cities has given rise to a multitude of concerns that cannot be ignored.The insatiable appetite for urban development has led to the displacement of countless communities, uprooting families and shattering the fabric of long-standing neighborhoods. Gentrification has become a double-edged sword, revitalizingareas while simultaneously pricing out those who once called these spaces home. The pursuit of modernity has come at the cost of cultural heritage, as historic landmarks and architectural marvels have fallen victim to the wrecking ball, erasing the very essence that made our cities unique.Beyond the social implications, the environmental toll of our cities' expansion is staggering. The concrete jungle has encroached upon green spaces, diminishing the vital lungs that once provided respite from the urban cacophony. Parks and recreational areas have dwindled, depriving residents of the mental and physical rejuvenation that nature offers. Furthermore, the increased reliance on private transportation has choked our streets with gridlock, contributing to alarming levels of air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions.The strain on infrastructure is another pressing issue that accompanies rapid urbanization. Our cities' aging systems struggle to keep pace with the influx of new residents and the ever-increasing demand for resources. Water shortages, power outages, and overburdened public transportation networks have become commonplace occurrences, hampering our quality of life and hindering economic productivity.Perhaps most concerning is the impact on our mentalwell-being. The relentless pace of city life, coupled with the incessant noise and overcrowding, has fostered a breeding ground for stress, anxiety, and social isolation. The pursuit of a better life in the urban jungle has paradoxically led to a deterioration of our mental health, as the pressures of modern living mount.It is imperative that we acknowledge these pressing issues and take decisive action to curb the unchecked growth of our cities. Sustainable urban planning must become a priority, striking a delicate balance between development and preservation. Innovative solutions, such as vertical farming, green infrastructure, and energy-efficient buildings, offer promising avenues for reducing our environmental footprint while accommodating population growth.Furthermore, we must prioritize the revitalization of existing urban spaces over the relentless expansion into new territories. Adaptive reuse of abandoned buildings and the rejuvenation of neglected neighborhoods can breathe new life into our cities without compromising their cultural identity or displacing existing communities.Ultimately, the path forward lies in fostering a collective consciousness that recognizes the intrinsic value of our urban landscapes beyond mere economic gain. Our cities are not mere canvases for concrete and steel; they are living, breathing entities that shape our experiences and define our collective identity. By embracing sustainable practices, preserving our cultural heritage, and prioritizing the well-being of our communities, we can forge cities that are not only monuments to progress but also havens of comfort, inspiration, and unity.As students and the inheritors of this urban legacy, it is our duty to raise our voices and advocate for responsible development. We must engage in dialogue with policymakers, urban planners, and community leaders, lending our perspectives and collaborating on solutions that address the multifaceted challenges before us. Only through collective action and a shared commitment to sustainable growth can we ensure that our cities remain vibrant, resilient, and livable for generations to come.The path ahead is not without obstacles, but the pursuit of a harmonious coexistence between progress and preservation is a noble endeavor worthy of our unwavering dedication. Let us embrace the opportunity to reshape our urban landscapes,transforming them into beacons of sustainability, cultural richness, and human-centric design. For it is within the boundaries of our cities that the greatest stories of human resilience and innovation unfold, and it is our responsibility to ensure that these narratives continue to inspire and uplift for centuries to come.篇3The Unchecked Growth of Megacities: A Looming CrisisAs a student living in a rapidly expanding metropolis, I can't help but feel concerned about the unbridled development happening all around me. The relentless construction of skyscrapers, highways, and residential complexes has transformed my city into an urban jungle, leaving me to grapple with the harsh realities of over-development.Everywhere I look, I see cranes dotting the skyline, their metallic arms reaching ever higher as if engaged in a constant battle for vertical supremacy. The once-familiar landscapes of my childhood have given way to a labyrinth of concrete and steel, obscuring the natural beauty that once defined our city.The consequences of this unchecked growth arefar-reaching and deeply troubling. One of the most pressingissues is the strain on our already overburdened infrastructure. The influx of people and vehicles has rendered our roads perpetually congested, turning my daily commute into asoul-crushing ordeal. The constant honking of horns and the thick haze of exhaust fumes have become an inescapable part of my daily reality.Moreover, the demand for housing has skyrocketed, leading to the construction of high-rise apartments that seem to sprout overnight like concrete mushrooms. These towering structures not only block out the sun and create wind tunnels, but they also contribute to the growing sense of isolation and disconnection within our communities.As our city expands outward, devouring the surrounding green spaces, I can't help but mourn the loss of the natural world that once served as a refuge from the chaos of urban life. The parks and open spaces that once provided respite have been paved over or overshadowed by towering edifices, robbing us of the opportunity to reconnect with nature and escape the concrete jungle, if only for a moment.The environmental toll of this rapid development is equally alarming. The construction process itself generates immense amounts of waste and pollution, while the influx of people andvehicles contributes to ever-increasing levels of air and noise pollution. The very air we breathe has become tainted, and the once-pristine waterways that crisscross our city now resemble open sewers, teeming with toxic runoff and discarded debris.But perhaps the most insidious impact of over-development is the erosion of our city's cultural identity. The relentless pursuit of modernity has led to the demolition of historic landmarks and the displacement of long-standing communities, severing our connection to the rich tapestry of our shared heritage. The unique character that once defined our city is rapidly giving way to a homogenized, globalized aesthetic, devoid of the cultural nuances that make a place truly special.As a student, I cannot help but feel a sense of despair at the prospect of inheriting a city that has sacrificed its soul in the name of progress. The constant noise, pollution, and overcrowding have taken a toll on my mental and physicalwell-being, leaving me longing for a more balanced and sustainable approach to urban development.It is imperative that we, as a society, reassess our priorities and find a way to strike a harmonious balance between growth and preservation. We must embrace sustainable developmentpractices that prioritize the environment, promote social cohesion, and respect our cultural heritage.This means investing in public transportation systems that reduce our reliance on private vehicles, implementing stricter regulations on construction and waste management, and preserving the remaining green spaces and historic sites that define our city's character.Furthermore, we must encourage the development of mixed-use neighborhoods that foster a sense of community and walkability, reducing the need for long commutes and promoting a healthier, more connected lifestyle.Ultimately, the solution lies in adopting a more holistic and long-term approach to urban planning, one that recognizes the interconnectedness of our social, environmental, and economic systems. By embracing sustainable practices and prioritizing the well-being of our citizens, we can create cities that are not only prosperous but also livable, vibrant, and resilient.As students and future leaders, it is our responsibility to raise our voices and demand change. We must hold our elected officials accountable and advocate for policies that promote responsible development and safeguard our city's unique identity.The path ahead will not be easy, but the alternative – a future defined by overcrowding, pollution, and the loss of our cultural heritage – is simply unacceptable. We must act now, before it is too late, and reclaim our city from the clutches of unchecked development.For it is only by striking a delicate balance between progress and preservation that we can ensure a future where our cities remain not just hubs of economic activity, but also places where we can truly thrive – physically, mentally, and spiritually.。

英语作文科技之城英语作文科技之城1Essay 1: The Vision of a Tech-Savvy CityIn the heart of the 21st century, the concept of a tech-savvy city, often referred to as a "Smart City," has emerged as a beacon of innovation and progress. This futuristic vision encompasses a metropolis where technology seamlessly integrates into every aspect of urban life, enhancing efficiency, sustainability, and quality of life for its residents. Imagine a city where intelligent transportation systems reduce traffic congestion, smart grids optimize energy usage, and digital platforms foster community engagement and governance.The cornerstone of a tech-savvy city lies in its infrastructure. High-speed internet and 5G networks blanket the urban landscape, enabling instant communication and real-time data exchange. Autonomous vehicles glide through the streets, guided by AI-powered traffic management systems that minimize accidents and delays. Public spaces are equipped with sensors that monitor air quality, noise levels, and pedestrian flow, ensuring a safe and pleasant environment for all.Sustainability is another key pillar. Smart buildings, equipped with IoT technology, adjust their lighting, heating, and cooling based on occupancy and weather conditions, reducing energy consumption. Renewable energy sources like solar and wind power are widely adopted, supported by advanced energy storage solutions. Waste management is revolutionized through recycling robots and smart bins that sort waste efficiently, contributing to a cleaner, greener city.Yet, the true spirit of a tech-savvy city goes beyond mere infrastructure. It is a place where technology empowers its citizens, fostering education, healthcare, and creativity. Virtual reality classrooms provide immersive learning experiences, while telemedicine platforms enable access to specialized healthcare regardless of one's location. Public libraries and innovation hubs become centers for digital literacy and entrepreneurship, nurturing the next generation of tech pioneers.In this vision of the future, the tech-savvy city is not just a place to live but a living, breathing ecosystem that evolves continuously, adapting to the needs and aspirations of its inhabitants. It stands as a testament to human ingenuity, demonstrating how technology, when used wisely, can create a more harmonious, efficient, and sustainable world.英语作文科技之城2Essay 2: The Impact of AI in a Tech-Driven CityArtificial Intelligence (AI) stands at the forefront of the transformation towards tech-driven cities, reshaping urban life in unprecedented ways. From optimizing public services to enhancing personal experiences, AI's influence is profound and multifaceted.In the realm of city management, AI-powered predictive analytics play a crucial role. By analyzing vast amounts of data collected from sensors and IoT devices, AI can forecast trends, detect patterns, and preemptively address issues such as traffic congestion, energy demand spikes, or public health crises. This proactive approach significantly enhances operational efficiency and resource allocation.Public safety is another area where AI makes a significant impact. Advanced surveillance systems, powered by machine learning algorithms, can detect suspicious activities, predict crime patterns, and facilitate rapid response from law enforcement agencies. Meanwhile, AI-driven chatbots and virtual assistants in emergency services provide instant support and guidance to citizens in distress.Healthcare, too, undergoes a revolution. AI algorithms analyze medical records, patient histories, and genetic data to personalize treatment plans, predict disease outbreaks, and accelerate drug discovery. Telemedicine platforms, integrated with AI for diagnostic accuracy, bring specialized care to remote areas, bridging the gap between urban and rural healthcare access.In daily life, AI-enabled services enhance convenience and personalization. Smart homes adjust to residents' preferences, while personal assistants manage schedules, order groceries, and control home security. AI-powered recommendation systems curate content, from news articles to dining options, based on individual interests.However, the integration of AI in tech-driven cities also necessitates a thoughtful approach to ethics, privacy, and inclusivity. Policies must be developed to ensure transparent AI usage, protect personal data, and prevent algorithmic biases that could exacerbate social inequalities. Ultimately, the integration of AI in tech-driven cities holds immense potential for improving quality of life, fostering innovation, and addressing global challenges. It requires a collaborative effort between governments, private sectors, and citizens to harness this power responsibly, ensuring that technology serves the best interests of all.英语作文科技之城3Essay 3: Green Tech in the Heart of a Smart CityIn the pursuit of sustainable urban development, green tech has become a cornerstone of the smart city movement. By integrating eco-friendly technologies into urban planning and infrastructure, smart cities are paving the way for a more environmentally conscious future. At the forefront of green tech innovation are renewable energy sources. Solar panels and wind turbines, strategically placed across rooftops, parks, and even roads, generate clean, renewable energy that powers homes, businesses, and public services. Complementing these are energy storage systems, such as battery packs and pumped hydro storage, which balance supply and demand, ensuring reliable and consistent energy access.Smart grids, the backbone of modern energy distribution, utilize IoT technology to monitor, control, and optimize electricity usage. They adapt to real-time conditions, reducing waste and enhancing efficiency. Through demand-response programs, consumers can be incentivized to reduce energy consumption during peak hours, further balancing the grid and lowering costs.In the realm of transportation, electric vehicles (EVs) and public transit systems powered by renewable energy are becoming the norm. EV charging stations, integrated into the urban landscape, make it convenient for drivers to switch to cleaner modes of transportation. Autonomous buses and shuttles reduce traffic congestion and carbon emissions, while bike-sharing programs and pedestrian-friendly zones encourage active transportation.Waste management is also revolutionized through green tech. Smart bins and recycling robots use sensors and machine learning to sort waste efficiently, minimizing landfill usageand enhancing recycling rates. Composting systems convert organic waste into nutrient-rich soil, promoting urban agriculture and closing the loop of resource utilization.Moreover, green tech plays a crucial role in urban planning. Green roofs and walls, urban forests, and parks not only beautify the city but also provide ecological benefits such as air purification, temperature regulation, and biodiversity conservation. Smart irrigation systems ensure that these green spaces are maintained with minimal water waste.The integration of green tech into smart cities demonstrates a commitment to environmental stewardship and sustainable development. It not only mitigates the negative impacts of urbanization but also fosters a resilient, healthy, and thriving urban environment for future generations.英语作文科技之城4Essay 4: Digital Governance in a Smart CityDigital governance, the application of digital technologies to public administration and decision-making, is a defining characteristic of a smart city. It enhances transparency, efficiency, and citizen participation, transforming how cities are governed and services are delivered.At the core of digital governance is the smart city platform, a centralized digital hub that integrates data from various city services and departments. This platform facilitates seamless communication and collaboration between municipal authorities, businesses, and residents. Through data analytics and visualization tools, city leaders can gain real-time insights into urban operations, making informed decisions that are both data-driven and citizen-centric. Open data initiatives play a crucial role in fostering transparency and accountability. By making public datasets accessible and easy to understand, citizens can monitor government performance, identify inefficiencies, and engage in policy discussions. This empowers citizens to become active participants in governance, driving innovation and social change.E-governance services, such as online permit applications, tax payments, and public service bookings, streamline administrative processes, reducing paperwork and wait times. Mobile apps and digital platforms enable citizens to access services remotely, enhancing convenience and accessibility, particularly for those in rural or underserved areas.Digital democracy initiatives further enhance citizen participation. Online surveys, public consultations, and digital deliberative forums provide platforms for citizens to voice their opinions and influence policy decisions. Blockchain technology can ensure the integrity and transparency of these processes, fostering trust in public institutions.However, the implementation of digital governance requires careful consideration of data privacy and security. Robust cybersecurity measures must be implemented to protect sensitive information from breaches and misuse. Policies must also address digital divides, ensuring equitable access to technology and digital literacy programs for all residents.In summary, digital governance is instrumental in achieving the smart city vision. It fosters a culture of transparency, efficiency, and inclusivity, empowering citizens to actively participate in the governance of their city. As cities continue to evolve, the integration of digital technologies will be crucial in addressing urban challenges and enhancing the quality of life for all residents.英语作文科技之城5Essay 5: The Future of Work in a Tech-Centric CityThe rise of tech-centric cities heralds a transformative shift in the world of work. With the proliferation of digital technologies, automation, and artificial intelligence, the future of work is becoming increasingly dynamic, flexible, and interconnected.In tech-centric cities, the traditional office setup is evolving. Coworking spaces and innovation hubs have emerged as vibrant centers of collaboration and creativity, catering to the needs of startups, freelancers, and remote workers. These flexible work environments foster a sense of community, enabling professionals to share resources, ideas, and networks.Automation and AI are transforming job roles and skill requirements. Repetitive tasks are increasingly being handled by machines, freeing up humans to focus on more complex, creative, and strategic work. This shift necessitates a re-skilling and up-skilling of the workforce, with a focus on digital literacy, data analytics, AI, and soft skills such as adaptability and critical thinking.The gig economy is thriving in tech-centric cities. Platforms like Uber, Airbnb, and Upwork provide opportunities for individuals to monetize their skills and assets, creating flexible and diverse income streams. This on-demand economy caters to the needs of both employers and workers, fostering a more dynamic and responsive labor market.。

推动交通发展重要因素英语作文Transportation is a critical factor in the development of any society. The efficiency and reliability of transportation systems directly impact various sectors, including economy, social integration, and quality of life. In this essay, we will explore some key factors that play a significant role in driving the development of transportation.Firstly, infrastructure is a crucial element in promoting transportation advancement. Well-maintained road networks, bridges, tunnels, airports, seaports, and railway lines are essential for facilitating smooth movement of people and goods from one place to another. Investing in modern infrastructure helps to reduce travel times and costs while enhancing connectivity between different regions.Another important consideration is technological advancements. Innovations such as high-speed trains, electric vehicles, autonomous drones for deliveries, and digital traffic management systems have revolutionized theway we commute and transport goods. Embracing technological advancements not only improves the efficiency of transportation but also reduces environmental impacts through sustainable solutions.Furthermore, policy and regulation have a significant impact on shaping transportation development. Governments need to implement favorable policies and regulations that encourage investment in transportation infrastructure, promote clean energy usage, develop public transit systems, and ensure safety standards. Effective policies can stimulate private sector participation while addressing issues such as congestion and pollution.In addition to this, economic factors play a crucial rolein driving transportation development. Investments in transportation projects create job opportunities and stimulate economic growth by boosting trade activities. Efficient logistics and supply chain management contribute to cost savings for businesses while enabling them to reach wider markets.Moreover, environmental sustainability is an increasingly important factor in transportation development. As the world faces climate change challenges, there is a growing emphasis on reducing carbon emissions from transport activities. Promoting alternative fuels, improving fuel efficiency standards, developing eco-friendly modes of transport like cycling lanes or walking paths contribute to sustainable transportation growth.Equally important are social considerations such as accessibility and inclusivity. A well-developed transport system should cater to the needs of all community members regardless of their age or physical abilities. Accessible public transit options ensure equal opportunities for employment, education, healthcare access while promoting social cohesion through enhanced mobility.Furthermore, global connectivity plays a vital role in advancing transportation systems. International cooperation among nations facilitates cross-border trade and tourism which calls for standardized regulations on customs clearance procedures, permits for international roadtransport carriers among others ensuring seamless movement across borders.In conclusion -inter-connectedness exceeding just physical links- the development journey of any modern society cannot be realized without addressing key elements such as robust infrastructure investment complemented with enabling technologies favoring green approaches; facilitated by effective policies reinforcing economic upliftment within an ambit fostering inclusive mobility ideas across global psychic webs as vital intersections steering touching everyday lives around us!。

315打假英语作文700字英文回答:Consumer Protection Day: Combating Counterfeit and Substandard Products.3.15 Consumer Protection Day is a significant event in China, dedicated to safeguarding consumer rights and promoting fair trade practices. This day serves as a stark reminder of the prevalence of counterfeit and substandard products in the market, highlighting the need for stringent measures to protect consumers from fraudulent and harmful goods.The Chinese government has taken several initiatives to address this issue, including establishing the State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR), a dedicated agency responsible for enforcing product quality standards and cracking down on counterfeiting. In recent years, SAMR has conducted numerous inspections and raids, resulting inthe confiscation of vast quantities of counterfeit goods and the imposition of severe penalties on violators.However, despite these efforts, counterfeit and substandard products continue to permeate the market, posing serious threats to consumers' health, safety, and financial well-being. Consumers must remain vigilant and exercise caution when purchasing goods, especially from unauthorized or untrustworthy sources.Strategies to Combat Counterfeiting and Substandard Products.To effectively combat counterfeiting and substandard products, a multi-faceted approach is required, involving collaboration among government agencies, businesses, and consumers:Strengthening Regulations and Enforcement: Governments must enact and enforce stringent laws and regulations that deter counterfeiting and impose harsh penalties on violators. They should also establish independent testingand certification bodies to ensure product quality and safety.Promoting Transparency and Traceability: Businesses should adopt transparent supply chain practices and implement measures to trace the origin and movement oftheir products. This enhances accountability and makes it easier to identify and eliminate counterfeit goods.Educating Consumers: Consumers play a crucial role in fighting counterfeiting by being informed and cautious when making purchases. They should only buy from reputable sources, check product labels and packaging carefully, and report any suspected counterfeit or substandard products to relevant authorities.International Cooperation: Counterfeiting is a global problem that requires international collaboration. Governments and regulatory bodies worldwide should share information, coordinate enforcement efforts, and work together to disrupt counterfeit networks and protect consumers.Conclusion.3.15 Consumer Protection Day is an important reminder of the dangers posed by counterfeit and substandard products. While governments and businesses have a responsibility to protect consumers, individuals must also take an active role in combating these harmful practices. By working together, we can create a safer and fairer marketplace for all.中文回答:315打假日,打击假冒伪劣产品。

介绍大学宁夏大学的英语作文带翻译Ningxia University, established in 1958, has experienced almost half a century’s development and now becomes the key provincial comprehensive university run by both the Ministry of Education and Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region after two mergers since 1997.Ningxia University is located in the Xixia District of Yinchuan City. Surrounded by lush lawns and wide lakes, with the magnificent buildings and comprehensive facilities, it provides a beautiful environment for students. Ningxia University shows its vitality through the devoted faculty members and energetic students, multipurpose centers, a modern library with rich collections, advanced laboratories, regulation sports ground and stadium, wide-spread information networks and fully equipped students’dorms.In almost 50 years, Ningxia University has cultivated more than 60,000 qualified graduates in various fields and specialties, making great contributions to the local economic and social development.Currently, holding the concept of Scientific Development and carrying out important thoughts of "Three Represents", Ningxia University emphasizes its educational philosophy of “cultivating talents in combination with the spirit of humanities and science”, and placing the individual as its highest priority. It comprehensively focuses on quality education with unique characteristics and educational style so asto continuously improve teaching quality and strengthen scientific technology innovation and achievements. In addition, by carrying out the strategy of open development and strengthening the cooperation and exchanges with domestic and foreign universities and colleges, Ningxia University raises its impact both at home and abroad.In the "Eleventh Five-year" plan, Ningxia University will focus on the principles of "preserve, deepen, improve and develop”, pursue the balanced development of internal and external force and continue to deepen the reforms of education, scientific technology system, personnel regulations and administration. Following the motto of "Be Moral, Diligent, True and Creative”, and emphasizing the spirit of “Devotion and Development”, we are making Ningxia University a comprehensive university with the highest academic prestige in Western China.翻译:宁夏大学成立于1958年,经过近半个世纪的发展,自1997年起两次合并,现已成为教育部和宁夏回族自治区两手办的省级重点综合性大学。

电气专业课英文名称Electrical Engineering: A Comprehensive Overview.Electrical engineering is a vast and diverse field that encompasses the study, design, and application of electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. Electrical engineers play a crucial role in shaping the modern world, as they are responsible for developing and maintaining the electrical systems that power our homes, businesses, and transportation networks.History of Electrical Engineering.The origins of electrical engineering can be tracedback to the early 19th century, with the work of scientists such as Alessandro Volta, who invented the electric battery, and Michael Faraday, who discovered electromagnetic induction. However, it was not until the late 19th century that electrical engineering became a recognized profession, with the establishment of the first electrical engineeringprograms at universities such as the MassachusettsInstitute of Technology (MIT) and the University ofIllinois at Urbana-Champaign.Fundamentals of Electrical Engineering.The fundamental principles of electrical engineering include:Electricity: The flow of electric charge.Electronics: The study of electronic devices and circuits.Electromagnetism: The interaction between electricity and magnetism.Electrical engineers use these principles to design and build a wide range of electrical systems, including:Power systems: The generation, transmission, and distribution of electricity.Control systems: The regulation of electrical systems to maintain desired performance.Electronic systems: The use of electronic devices to perform specific tasks.Types of Electrical Engineering.There are many different types of electrical engineering, each with its own focus and area of expertise. Some of the most common types of electrical engineering include:Power engineering: The design and operation of power systems.Electronics engineering: The design and development of electronic devices and circuits.Control engineering: The design and implementation of control systems.Computer engineering: The design and development of computer systems.Telecommunications engineering: The design and operation of telecommunications systems.Applications of Electrical Engineering.Electrical engineering is used in a wide variety of applications, including:Power generation: Electrical engineers design and operate power plants that generate electricity from various sources, such as coal, natural gas, nuclear energy, and renewable energy sources.Power transmission and distribution: Electrical engineers design and maintain the electrical grids that transmit and distribute electricity to homes, businesses, and industries.Industrial automation: Electrical engineers design and implement control systems that automate industrial processes, such as manufacturing and assembly.Consumer electronics: Electrical engineers design and develop electronic devices that are used in everyday life, such as smartphones, computers, and televisions.Medical technology: Electrical engineers design and develop medical devices and systems, such as MRI machines and pacemakers.Education and Career Paths in Electrical Engineering.To become an electrical engineer, one typically needs to earn a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from an accredited university. Some electrical engineers also choose to pursue a master's degree or doctorate inelectrical engineering or a related field.Electrical engineers can work in a variety of industries, including:Utilities: Electric utilities, water utilities, and gas utilities.Manufacturing: Automotive, aerospace, and consumer electronics manufacturing.Construction: Electrical contractors and consulting engineers.Government: Federal, state, and local government agencies.Academia: Universities and research institutions.Conclusion.Electrical engineering is a challenging and rewarding field that offers a wide range of opportunities for career growth and advancement. Electrical engineers play a vital role in shaping the modern world, as they are responsiblefor developing and maintaining the electrical systems that power our homes, businesses, and transportation networks.。