presentation-order effects for aesthetic stimulus preference

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:334.74 KB

- 文档页数:13

Personalized information technology services have become a ubiquitous phenomenon. While there is a lot of hype about delivering personalized services over the web, little is known about the effectiveness of web personalization and the link between the IT artifact(the personalization agent) and the effects it exerts on a user’s information processing and decision making.W eb Personalization1.Goal: deliver the right content to the right person at the right time to maximize immediate andfuture business opportunitiesApproaches: user-driven /transaction-driven/ context-driven personalizationUser-driven: provides the user with tools and options to specify information requirements and presentation format.(My Y ahoo!)Transaction-driven: personalization is driven by previous transactions rather than specified by the user inadvance.()Context-driven: a very adaptive mechanism is employed to personalize content and layout for each individual user, click stream analysis and web mining have made it possible to understand the context and to infer user’s processing objective in real time, sensitive to the context of interaction.()2.Personalization Agent(PA):IT enabler of web personalizationA collection of software modules used to generate unique content to individual users.collect and analyze web activities and transactions to generate highly adaptive content for individual users(Mobasher et al. 2000)stimuli:text,images,audio, animations, video3.Model of personalization agentBased: social cognition & consumer decision research[social cognition: it involves the study of how an individual constructs his/her social reality, which is the result of the individual’s cognitive outcome in processing sensory stimuli; the focus of social cognition is on the cognitive mechanisms that mediate judgment and behavior(Wyer&Srull,1989); the cognitive perspective of information processing allows systematic investigation of the effectiveness of web personalizationconsumer decision research: a consumer’s choice is shaped by the way humans process information and the properties of the task environment]Web stimuli: whether a web stimuli catches the user’s attention depends on its saliency relative to its context(Chimera and Shneider-man 1994; Nielsen 2000)Cognitive processing: encoding & categorizing the stimulus based on prior knowledge(Knowledgeis organized in the form of schema in permanent memory).—a user retrieve relevant schema from permanent memory into working memory(Working memory is the location whererelevant schemas related to a particular processing goal residefor inferencing and judgment)Self schema: One schema that is particularly relevant to web personalization is the self schema (Wyer and Srull 1989)[it contains information about oneself, including perceptions, attributes, and experiences related to the self]Preference structure construction: (Dynamic Preference Construction)Understandingusers’ preferences and providing offers that fit those preferences is a basic premise of any personalization strategy.evidence is mounting that preferences are not staticand purchases are not necessarily driven by well-formedpreference structures (Bettman et al. 1998; Slovic 1995)preferences are fluid and are constructed on the fly by users,especially in situations where users are not knowledgeable about the choice options (Y aniv 2004)subject to influences: framing of alternatives, trust toward the seller/agent, user interface of the information systemunderstanding spontaneous preferences&factors that shape preferences will provide the merchant with significant competitive advantage over its rivals. Interactivity provided by IT at each touch point &the vast amount of data collected on customers allow online merchants to learn and influence their users’ spontaneous preferencesWeb Personalization as a Persuasion Strategy: Elaboration Likelihood ModelELM was originally developed to understand the processing of persuasive messages from a social psychology perspective.Originally, the model was developed to provide an organized framework to address issues related to information sources, personality, and context effects of persuasion(Areni et al.2000).rmation-Processing Model2 dimensions of information processing: the process & the level of cognitive effectStages(information side): attention, elaboration, behavior (Bargh 2002) [not every message detected will go through all the stages]Level of cognitive effect (receiver side):(MacInnis&Jaworski 1989)Preattention: attention of user is very low, stimuli are immediately analyzed and yield few or no effects(Greenwald and Leavitt 1984)Focal attention: is divided between the message and a secondary task, users transfer their attention from the secondary task to the personalized message, a process that resembles classical conditioningHeuristic assessment: when the motivation to process information is low to moderate, users direct their attention toward the message, but the cognitive capacity remains low and they use easy-to-process cuesCentral processing: moderately motivated and try to integrate the full information of the message, use prior knowledge and experienceRelate prior knowledge to message: users relate their own experience to the messageEmbellish message: adding either positive or negative attributes and uses not mentioned in the message(Mick 1992)2.Elaboration Likelihood ModelIt focuses on the second stage of information processing: elaborationPsychologist Petty &Cacioppo 1986Central route: message recipients have both the motivation(劝导信息与消费者个人需求的相关性)and the ability to consider detailed information in a given message, persuasion occurs(critical thinking , message is given due consideration, need more cognitive efforts, attitude change is driven by the careful consideration of relevant arguments supporting the advocated position,基于理性)Peripheral route: lack either the motivation or the ability to process the detailed information in the message content, they rely on simple cues for judgment formation(“This is a personalized product for me, so it shoule be good”, sex/money/celebrity产品包装、广告形象的吸引力、信息表达方式,与真实信息的内容无直接联系,基于感性)The central questions for a firm deploying personalization agents are whether these heuristic rules exist and how to trigger them in a web environment.Central route(motivation/ability/argument)Nature of arguments in the message:What is the message trying to say?If it is a strong message—if it is a well-constructed and convincing message, the receiver is more likely to receive it favorably. Persuasion may occur even if the message content is in contrast to the receiver’s initial attitude.If it contains false information there is likely to be a boomerang effect.This means that the receiver will reject the message and form negative thoughts and feelings about the message.Central and peripheral routes to persuasion. The figure depicts the two anchoring endpoints on the elaboration likelihood model continuum(adapted from Petty,1977;Petty&Cacioppo,1978,1981a)。

高考英语外刊时文精读专题:2023年高考英语外刊时文精读精练 (8)Perception: A rose by any other name文化认知:情人眼里出西施主题语境:人与社会主题语境内容:社会与文化【外刊原文】(斜体单词为超纲词汇,认识即可;下划线单词为课标词汇,需熟记。

)TO THE SWEDES, there are few smells more pleasant than that of surströmming(鲱鱼罐头). To most non-Swedes there are probably few smells more disgusting. In determining which scents(气味) people find pleasant and which they do not,surströmming suggests culture must play a large part. New research, however, suggests that might not be the case. Artin Arshamian, a neuroscientist at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, and Asifa Majid, a psychologist at the University of Oxford, began with the expectation that culture would play an important role in determining pleasant smells. They had noticed from their own previous work that people from different cultures described smells differently. They also knew from past experiments by other researchers that culture was important in determining which sorts of faces people found beautiful. Thus, they expected to see a similar phenomenon with smells. To study how scent and culture relate, Dr Arshamian and Dr Majid presented nine different groups of people with ten smell s. The cultures doing the smelling varied widely . They included hunter-gathere r communitiesalong the coast of Mexico, farmers living in the highlands ofEcuador, shoreline foragers, gardeners living in the tropical rainforests of Malaysia, and city folk from Thailand and Mexico City. All 235 participants were asked to rank smells according to pleasantness. The team compared their results to earlier work on New Yorkers who had been exposed to the same scents.Writing in Current Biology this week, the researchers noted that pleasantness rankings ofthe smells were remarkably consistent regardless of where people came from. The smell of isovaleric acid(异戊酸)was disliked by the vast majority of the participants, only eight giving it a score of 1 to 3 on thepleasantness scale (where 1 was very pleasant and 10 was very unpleasant). On the other hand, more than 190 people gave vanilla extract (香草精) a score of 1 to 3 and a tiny minority, only 12 people, found it disgusting enough to rate 8 to 10. Overall, the chemical composition of the smells that the researchers presented explained 41% of the reactions that participants had.In contrast, cultural factors accounted for just 6% of the results. Dr Arshamian and Dr Majid point out that this is very different from how visual perception of faces works—in that case a person’s culture accounts for up to 50% of the e xplanation for which faces they find beautiful.Even so, while culture did not shape perceptions of smells in the way that it is known to shape perceptions of faces, the researchers did find an “eye of the beholder” effect. Randomness, which Dr Arshamian and Dr Majid suggest has to be coming from personal preferences learned from outside individual culture, accounted for 54% of the difference in which smells people liked. “eye of the beholder” effectdoes not slip off the tongue so easily but it too appears to be a real phenomenon.【课标词汇】1.Disgusting令人反感的;令人愤慨的He had the most disgusting rotten teeth.他长着非常恶心的一嘴烂牙。

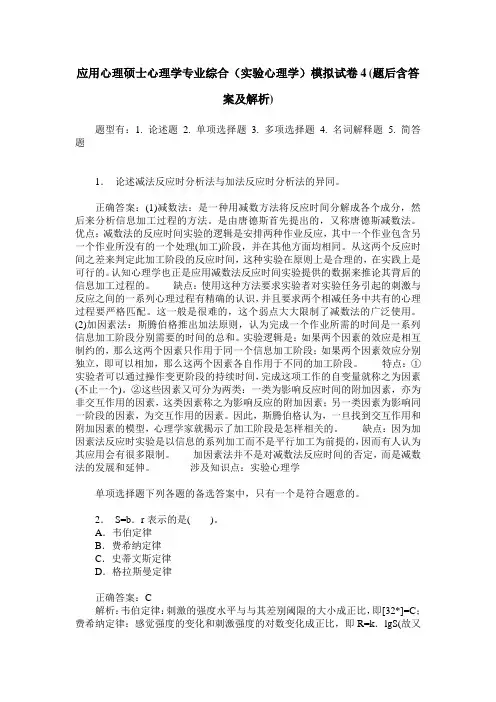

应用心理硕士心理学专业综合(实验心理学)模拟试卷4(题后含答案及解析)题型有:1. 论述题 2. 单项选择题 3. 多项选择题 4. 名词解释题 5. 简答题1.论述减法反应时分析法与加法反应时分析法的异同。

正确答案:(1)减数法:是一种用减数方法将反应时间分解成各个成分,然后来分析信息加工过程的方法。

是由唐德斯首先提出的,又称唐德斯减数法。

优点:减数法的反应时间实验的逻辑是安排两种作业反应,其中一个作业包含另一个作业所没有的一个处理(加工)阶段,并在其他方面均相同。

从这两个反应时间之差来判定此加工阶段的反应时间,这种实验在原则上是合理的,在实践上是可行的。

认知心理学也正是应用减数法反应时间实验提供的数据来推论其背后的信息加工过程的。

缺点:使用这种方法要求实验者对实验任务引起的刺激与反应之间的一系列心理过程有精确的认识,并且要求两个相减任务中共有的心理过程要严格匹配。

这一般是很难的,这个弱点大大限制了减数法的广泛使用。

(2)加因素法:斯腾伯格推出加法原则,认为完成一个作业所需的时间是一系列信息加工阶段分别需要的时间的总和。

实验逻辑是:如果两个因素的效应是相互制约的,那么这两个因素只作用于同一个信息加工阶段;如果两个因素效应分别独立,即可以相加,那么这两个因素各自作用于不同的加工阶段。

特点:①实验者可以通过操作变更阶段的持续时间,完成这项工作的自变量就称之为因素(不止一个)。

②这些因素又可分为两类:一类为影响反应时间的附加因素,亦为非交互作用的因素,这类因素称之为影响反应的附加因素;另一类因素为影响同一阶段的因素,为交互作用的因素。

因此,斯腾伯格认为,一旦找到交互作用和附加因素的模型,心理学家就揭示了加工阶段是怎样相关的。

缺点:因为加因素法反应时实验是以信息的系列加工而不是平行加工为前提的,因而有人认为其应用会有很多限制。

加因素法并不是对减数法反应时间的否定,而是减数法的发展和延伸。

涉及知识点:实验心理学单项选择题下列各题的备选答案中,只有一个是符合题意的。

As a student of adversity, I've been struck over the years by how some people with major challenges seem to draw strength from them, and I've heard the popular wisdom that that has to do with finding meaning. And for a long time, I thought the meaning was out there, some great truth waiting to be found.我从逆境中学习:这些年来,我一次又一次被人们如何从极大的挑战中得到力量而震撼,人们说,这和找寻生命的意义有关。

很长一段时间,我以为生命的意义在某一处它是等待被发掘的真理。

Since the outbreak of an infectious disease in Wuhan in December 2019, the Chinese government has decisively closed down the city to prevent the spread of the disease. At the same time, although cases have been found throughout the country, the Chinese people actively face it, together with Wuhan to fight the epidemic.At this particular time, we should go out as little as possible, isolated. If we go out, we must wear protective masks to prevent ourselves from getting infected. In addition, we should keep good healthy habits and keep our body clean.Now during the most crucial time for all humankind.It’s time to pay back with our prayers for the world around us. The novel corona virus epidemic is sweeping the world,clearly, there is something deeply rooted about it, something which scares us and fascinates us more than other diseases. But what is it, exactly? If the global epidemic is a dragon, the countries that help each other are the heroes of light and hope,morning and glory.But if you banish the dragons, you banish the heroes, and we become attached to the heroic strain in our own lives. That's what disaster makes for life.现在在全人类最艰难的时刻,是时候我们投桃报李向世界人民祈福。

第44卷 第8期 包 装 工 程2023年4月 PACKAGING ENGINEERING81收稿日期:2023–02–19基金项目:国家重点研发计划项目(2022YFB3303300);国家自然科学基金(62207024,62107035) 作者简介:孙凌云(1981—),男,教授,主要研究方向为智能设计、交互设计等。

通信作者:陈培(1996—),女,博士后,主要研究方向为设计智能、人机协作等。

孙凌云1,2,王可幸1,2,陈培1,2,周子洪1,2,杨昌源3,杨光3(1.浙江大学 计算机科学与技术学院,杭州 310013;2.阿里巴巴-浙江大学前沿技术联合研究中心,杭州 310027;3.阿里巴巴集团,杭州 311121)摘要:目的 对多通道人机交互中感觉刺激模拟方法的研究现状进行梳理,总结现有研究中的相关技术原理与方法,为后续的相关研究和实践提供参考。

方法 利用文献调研和典型案例分析方法,梳理了触觉、嗅觉及味觉三种单通道感觉刺激模拟的相关技术;概述了多通道感觉刺激融合的认知学理论,并以视听触融合、视听嗅融合为例,总结了多通道感觉刺激融合的具体实现方法;介绍了多通道感觉刺激融合在医疗康复、虚拟购物、智能教育等典型场景中的应用。

结论 多通道人机交互中感觉刺激的模拟方法研究有望支持低负荷、高效率的新型人机交互方式,甚至带来超越真实的交互体验,具备广泛的应用潜力。

关键词:多通道人机交互;感觉刺激模拟;感觉刺激融合中图分类号:TB472 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1001-3563(2023)08-0081-14 DOI :10.19554/ki.1001-3563.2023.08.008Review of Sensory Feedback Simulation Methods in Multi-modalHuman-computer InteractionSUN Ling-yun 1,2, WANG Ke-xing 1,2, CHEN Pei 1,2, ZHOU Zi-hong 1,2,YANG Chang-yuan 3, YANG Guang 3(1. College of Computer Science and Technology, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310013, China; 2. Alibaba-Zhejiang University Joint Institute of Frontier Technologies, Hangzhou 310027, China;3. Alibaba Group, Hangzhou 311121, China)ABSTRACT: The work aims to sort out the research status of sensory feedback simulation methods in multi-modal hu-man-computer interaction and summarize the principles and implementation methods of related techniques in existing re-search, so as to provide references for the subsequent research and practice. Firstly, the techniques used to simulate haptic, olfactory, and gustatory feedback were summarized respectively by reviewing literature and studying typical cases. Then, the cognitive theories about multi-modal sensory integration were outlined and the specific implementation methods were introduced by taking visual-aural-haptic and visual-aural-olfactory feedback integration as examples. Finally, the applica-tion of multi-modal sensory feedback in typical scenarios such as medical rehabilitation, virtual shopping, and intelligent education was expounded. The research of sensory feedback simulation methods in multi-modal human-computer interac-tion is expected to support a new type of human-computer interaction with low load and high efficiency. It can even de-liver an interactive experience that goes beyond reality, representing a wide range of application potential.KEY WORDS: multi-modal human-computer interaction; sensory feedback simulation; multi-modal sensory integration人机交互界面是人与机器之间的沟通接口。

心理学报 2018, Vol. 50, No.4, 363Acta Psychologica Sinica DOI: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2018.00363收稿日期: 2017-05-03* 国家社科基金(12BSH055)、国家自然科学基金(31540024)、宁波大学研究生科研创新基金(G17007)资助。

李玥和韩尚锋同为第一作者。

通信作者: 张林,E-mail:*****************.cn;刘燊,E-mail:*******************.cn美在观察者眼中:陌生面孔吸引力评价中的晕轮效应与泛化效应*韩尚锋1 李 玥1,2 刘 燊1,3 徐 强1 谭 群1 张 林1(1 宁波大学心理学系暨研究所, 宁波 315211) (2 云南商务职业技术学院, 昆明 650000)(3 中国科学技术大学人文与社会科学学院, 合肥 230022)摘 要 本研究旨在探讨陌生面孔吸引力的知觉加工过程, 采用“学习−评价”任务考察晕轮效应和泛化效应在其中的作用。

结果发现, 陌生面孔吸引力的加工有两条路径:(1)熟悉面孔的积极特质先发生晕轮效应进而出现泛化, 即相比于具有消极特质的熟悉面孔, 具有积极特质的熟悉面孔更有吸引力, 与其相似的陌生面孔也更有吸引力; (2)熟悉面孔的积极特质先发生泛化进而出现晕轮效应, 即相比于那些消极的熟悉面孔, 与积极熟悉面孔相似的陌生面孔特质评价更为积极, 且其吸引力评价也更高。

这表明晕轮效应和泛化效应在陌生面孔吸引力评价中发挥着重要的作用。

关键词 相似性; 晕轮效应; 泛化效应; 陌生面孔吸引力; 印象形成 分类号 B849:C911 引言面对没有任何交往经验的陌生人, 人们会有似曾相识或一见如故的感觉, 异性之间甚至会出现“一见钟情”的现象。

虽然人们常说“人不可貌相”, 但面孔在印象形成过程中却发挥着至关重要的作用。

研究表明, 人们会基于面孔特征快速、自动化地形成印象(Klapper, Dotsch, van Rooij, & Wigboldus, 2016)。

Presentation-ordereffectsforaestheticstimuluspreferenceMatsP.Englund&ÅkeHellström

Publishedonline:4July2012#PsychonomicSociety,Inc.2012

AbstractForpreferencecomparisonsofpairedsuccessivemusicalexcerpts,Koh(AmericanJournalofPsychology,80,171–185,1967)foundtime-ordereffects(TOEs)thatcorrelatednegativelywithstimulusvalence—thefirst(vs.thesecond)oftwounpleasant(vs.twopleasant)excerptstendedtobepreferred.Wepresentthreeexperimentsdesignedtoinvestigatewhethervalence-level-dependentor-dereffectsforaestheticpreference(a)canbeaccountedforusingHellström’s(e.g.,JournalofExperimentalPsycholo-gy:HumanPerceptionandPerformance,5,460–477,1979)sensation-weighting(SW)model,(b)canbegeneralizedtosuccessiveandtosimultaneousvisualstimuli,and(c)vary,inaccordancewiththestimulusweighting,withinterstimu-lusinterval(ISI;forsuccessivestimuli)orstimulusduration(forsimultaneousstimuli).Participantscomparedpairedsuccessivejingles(Exp.1),successivecolorpatterns(Exp.2),andsimultaneouscolorpatterns(Exp.3),selectingthepre-ferredstimulus.TheresultswerewelldescribedbytheSWmodel,whichprovidedabetterfitthandidtwoextendedversionsoftheBradley–Terry–Lucemodel.Experiments1and2revealedhigherweightsforthesecondstimulusthanforthefirst,andnegativelyvalence-level-dependentTOEs.InExperiment3,therewasnolateralityeffectonthestimulusweightingandnovalence-level-dependentspace-ordereffects(SOEs).IntermsoftheSWmodel,thevalence-level-dependentTOEscanbeexplainedasaconsequenceofdiffer-entialstimulusweightingincombinationwithstimulusvalencevaryingfromlowtohigh,andtheabsenceofvalence-level-dependentSOEsasaconsequenceoftheabsenceofdifferentialweighting.Forsuccessivestimuli,therewerenoimportant

effectsofISIonweightingsandTOEs,and,forsimultaneousstimuli,durationhadonlyasmalleffectontheweighting.

KeywordsAestheticpreference.Presentationorder.Time-ordererrors.Space-ordererrors.Visualperception.Audition.Mathmodeling

Fechner(1860)wasthefirsttonoticetheubiquitousandenigmaticsystematicerrorsthatoccurincomparisonsofsuccessiveandsimultaneousstimuli,whichmaketwophys-icallyequalstimulisubjectivelydifferentwhencompared:theZeitfehler(time-ordererror)andtheRaumfehler(space-ordererror).Thetime-ordereffect(TOE)andspace-ordereffect(SOE)weredefinedaspositive(vs.negative)foroverestimation(vs.underestimation)ofthefirstorleftstim-ulus,respectively,relativetothesecondorrightstimulus.Fechner(1876)alsointroducedexperimentalaesthetics,withscalingofaestheticappreciation.However,henevercombinedthosetwosubjects,whichweattempttodointhepresentarticle.SinceFechner’s(1860)discovery,TOEshavebeenfoundforawiderangeofmodalities,includingheaviness,toneloudness,linelength,duration(see,e.g.,Guilford,1954;Hellström,1985,forreviews),andbrightness(Maeda,1959).SOEshavebeenfoundincomparisonsof,forexam-ple,linelength(Hellström,2003;Masin&Agostini,1991)andbrightness(Kellogg,1931;Mattingley,Bradshaw,Nettleton,&Bradshaw,1994).Thesepresentation-ordereffectsare,however,notrestrictedtocomparisonsofstimulivariedonawell-definedphysicalcontinuum.TOEshavealsobeenfoundforpreferencejudgmentsofvisualstimuli(McLaughlin&Kermisch,1997),auditorystimuli(Beebe-Center,1932/1965;Koh,1967;Koh&Hedlund,1969),andodors(Beebe-Center,1932/1965).Forexample,Koh(1967)

M.P.Englund:Å.Hellström(*)DepartmentofPsychology,StockholmUniversity,SE-10691Stockholm,Swedene-mail:hellst@psychology.su.se

AttenPerceptPsychophys(2012)74:1499–1511DOI10.3758/s13414-012-0333-9investigatedthepossibleexistenceofTOEsformusicalpleasantness.Shehadparticipantsratethepleasantnessoftape-recordedvocalexcerpts(eachlasting60s)andpianoexcerpts(eachlasting15s)ona9-stepscalefrommostpleasant(1)tomostunpleasant(9).Pairsofexcerptswithequalmeanratingswerethenselectedandpresentedsuc-cessively,withaninterstimulusinterval(ISI)andaninter-trialinterval(ITI)ofabout6and10s,respectively,toanothersampleofparticipants;theseparticipantsweretojudgethedirectionanddegreeofthepleasantnessdifferencebetweentheexcerptsineachpair,usinga7-stepscale.Forthevocalaswellasthepianoexcerpts,largeTOEsoccurredthatwerehighlycorrelatedwiththemeanpleasantnessrating:Participantsconsistentlytendedtopreferthesecond(anegativeTOE)outoftwopleasantexcerptsandthefirst(apositiveTOE)outoftwounpleasantones.Onaverage,therewasaslighttendencytowardanegativeTOE.KohandHedlundobtainedsimilarresults.Otherexperiments,reportedbyBeebe-Center(1932/1965),inwhichthepleas-antnessofauditorystimuliwascompared,showedTOEsvaryingwiththelengthoftheISI;TOEswerepositivewithanISIof1.5s,butnegativewithISIsof2sandlonger.Theresultsofthesepleasantnesscomparisonsresemblethoseofmagnitudecomparisonsontraditionalpsychophysicalcon-tinua—forinstance,loudness(Hellström,1979;Needham,1935),heaviness(Hellström,2000;Woodrow,1933),andauditoryandvisualduration(Hellström,2003).Analogousmagnitude-dependentSOEshavebeenfoundincompari-sonsoflinelengths(Hellström,2003).AlthoughnegativeTOEshavebeenfoundmoreoftenthanpositiveones,aconsistentfindinghasbeenthatTOEsvarysystematicallywiththeintensityormagnitudelevelofthestimulation(see,e.g.,Hellström,1985).ThiswasthebasisforHellström’s(1979)sensation-weighting(SW)mod-el.Hellströmstudiedindetailtheeffectsofstimulusmag-nitudeontheTOEforloudnessunderdifferenttemporalstimuluspresentationconditions.ThisledtotheexplanationoftheTOEasasideeffectofsensationweighting:Thescaledsubjectivedifference,d12,betweentwocompared