膳食营养素参考摄入量:钙,磷,镁,维生素D和氟化物。

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:241.08 KB

- 文档页数:16

中国膳食营养素参考摄入量咱每天吃的饭啊,可不光是为了填饱肚子,这里面的学问可大了呢。

膳食营养素参考摄入量就是个特别重要的东西。

你想啊,咱身体就像一部超级精密的机器,而营养素就是让这部机器好好运转的各种小零件。

比如说蛋白质吧,这可是咱身体的建筑材料呢。

像那些健身的小伙伴们,对蛋白质的需求就比较高,因为肌肉的生长就靠它啦。

但也不是越多越好哦,吃太多肾脏会抗议的。

就像盖房子,材料够了就行,多了也没地儿放还添乱。

一般人每天吃多少蛋白质呢?这就得参考膳食营养素的摄入量啦。

对于成年人,每千克体重大概需要1克左右的蛋白质。

像个70千克的成年人,每天70克左右就挺合适。

这蛋白质从哪儿来呢?肉、蛋、奶、豆类都是很棒的来源。

再说说维生素吧。

维生素C就像个小卫士,能让咱皮肤好好的,还能增强免疫力。

要是缺了它,就容易生病,皮肤也变得粗糙。

咱平时吃的水果里就有好多维生素C呢,像橙子、柠檬之类的。

膳食营养素参考摄入量告诉咱,每天大概需要100毫克左右的维生素C。

可别小看这100毫克,它能让咱活力满满。

还有钙,钙是咱骨头的主要成分。

要是缺钙,年纪大了就容易骨质疏松。

好多人都知道喝牛奶补钙,这是对的。

膳食营养素参考摄入量里说,成年人每天大概需要800毫克的钙。

不过呢,除了牛奶,豆制品、绿叶蔬菜里也有钙。

铁也很重要啊,缺铁就容易贫血,人就没精神,脸色白白的。

女孩子每个月都有特殊时期,所以更要注意补铁。

膳食营养素参考摄入量里提到,成年男性每天需要12毫克左右的铁,女性因为有生理期,所以需要量会多一些,大概20毫克左右。

像动物肝脏、红肉都是很好的补铁食物。

咱老百姓过日子啊,每天做菜做饭的时候,要是心里有膳食营养素参考摄入量这个概念,就能把饭做得更健康。

不用精确到每一毫克,大概齐就行。

这就像做菜放盐,放多了咸得没法吃,放少了没味道,合适才好。

只要咱在日常饮食里把各种营养素都照顾到,身体这部大机器就能欢快地运转起来,咱也能健健康康、快快乐乐地过日子啦。

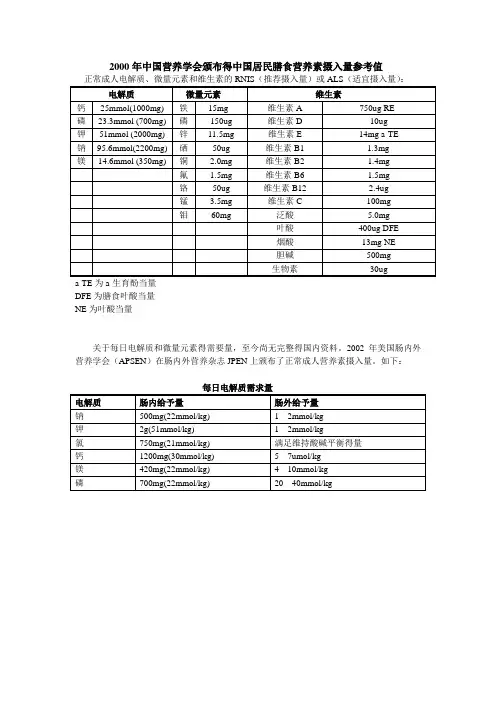

2000年中国营养学会颁布得中国居民膳食营养素摄入量参考值

正常成人电解质、微量元素和维生素的RNIS(推荐摄入量)或ALS(适宜摄入量):电解质微量元素维生素

钙25mmol(1000mg) 铁15mg 维生素A 750ug RE

磷23.3mmol (700mg) 磷150ug 维生素D 10ug

钾51mmol (2000mg) 锌11.5mg 维生素E 14mg a-TE

钠95.6mmol(2200mg) 硒50ug 维生素B1 1.3mg

镁14.6mmol (350mg) 铜 2.0mg 维生素B2 1.4mg

氟 1.5mg 维生素B6 1.5mg

铬50ug 维生素B12 2.4ug

锰 3.5mg 维生素C 100mg

钼60mg 泛酸 5.0mg

叶酸400ug DFE

烟酸13mg NE

胆碱500mg

生物素30ug

a-TE为a-生育酚当量

DFE为膳食叶酸当量

NE为叶酸当量

关于每日电解质和微量元素得需要量,至今尚无完整得国内资料。

2002年美国肠内外营养学会(APSEN)在肠内外营养杂志JPEN上颁布了正常成人营养素摄入量。

如下:

每日电解质需求量

电解质肠内给予量肠外给予量

钠500mg(22mmol/kg) 1---2mmol/kg

钾2g(51mmol/kg) 1---2mmol/kg

氯750mg(21mmol/kg) 满足维持酸碱平衡得量

钙1200mg(30mmol/kg) 5---7umol/kg

镁420mg(22mmol/kg) 4---10mmol/kg

磷700mg(22mmol/kg) 20---40mmol/kg。

我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量及老年人的钙摄入量一、引言在当今社会,随着人们生活水平的不断提高和医疗水平的不断进步,人们对健康的关注程度也越来越高。

膳食营养素的摄入量对人体健康有着至关重要的影响,而老年人由于身体功能的衰退和食欲减退等原因,更需要关注膳食营养素的摄入量。

本文将从我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量和老年人的钙摄入量两个方面展开讨论。

二、我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量是根据我国居民的膳食结构和生活习惯编制的,是我国卫生部门制定的标准。

根据我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量的标准,不同芳龄、性别、生理状态和身体活动水平的人群,对各种营养素的需求是不同的。

在日常饮食中,人们需要根据自己的实际情况,合理搭配食物,保证各种营养素的摄入量达到标准。

1. 碳水化合物:碳水化合物是人体最主要的能量来源,我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量建议,碳水化合物应占总能量的50%-65%。

2. 蛋白质:蛋白质是构成人体组织和细胞的重要成分,我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量建议,日粮蛋白质供给量为每日每公斤体重0.8克。

3. 脂肪:脂肪是人体重要的能量来源,我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量建议,脂肪应占总能量的25%-30%。

4. 矿物质和维生素:除了基本的碳水化合物、蛋白质和脂肪外,矿物质和维生素也是人体所需的重要营养素。

我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量对各种矿物质和维生素的需求量也有详细的标准。

根据我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量的标准,人们可以更科学地安排自己的膳食结构,保证膳食营养均衡,从而维持身体健康。

三、老年人的钙摄入量随着芳龄的增长,人体对某些营养素的需求量会发生变化,特别是钙这样的矿物质。

在老年人中,骨质疏松症是一种常见的疾病,而钙的摄入量不足是导致骨质疏松症的主要原因之一。

老年人对钙的摄入量需要特别关注。

根据我国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量的标准,老年人的钙摄入量应当增加。

建议60岁以上的老年人,每天的钙摄入量为800-1000毫克。

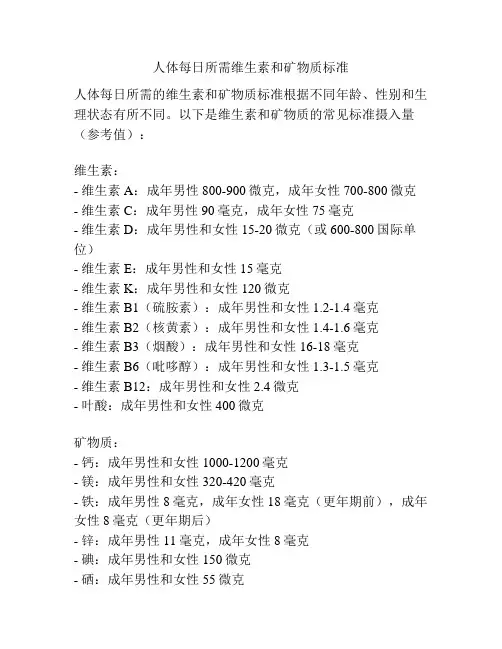

人体每日所需维生素和矿物质标准

人体每日所需的维生素和矿物质标准根据不同年龄、性别和生理状态有所不同。

以下是维生素和矿物质的常见标准摄入量(参考值):

维生素:

- 维生素A:成年男性800-900微克,成年女性700-800微克- 维生素C:成年男性90毫克,成年女性75毫克

- 维生素D:成年男性和女性15-20微克(或600-800国际单位)

- 维生素E:成年男性和女性15毫克

- 维生素K:成年男性和女性120微克

- 维生素B1(硫胺素):成年男性和女性1.2-1.4毫克

- 维生素B2(核黄素):成年男性和女性1.4-1.6毫克

- 维生素B3(烟酸):成年男性和女性16-18毫克

- 维生素B6(吡哆醇):成年男性和女性1.3-1.5毫克

- 维生素B12:成年男性和女性2.4微克

- 叶酸:成年男性和女性400微克

矿物质:

- 钙:成年男性和女性1000-1200毫克

- 镁:成年男性和女性320-420毫克

- 铁:成年男性8毫克,成年女性18毫克(更年期前),成年女性8毫克(更年期后)

- 锌:成年男性11毫克,成年女性8毫克

- 碘:成年男性和女性150微克

- 硒:成年男性和女性55微克

- 钠:成年男性和女性控制在2300毫克以内

- 钾:成年男性和女性2500-3500毫克

请注意,这只是一般成人的摄入参考值,具体的个体需求可能因个人身体状况、健康问题、孕期等因素而有所差异。

如果您有特殊的健康需求,请咨询医生或营养师以获得更准确的建议。

、中国居民膳食营养素参考摄入量表DRIsDRIs是在RDAs基础上发展起来的一组每日平均膳食营养素摄入量的参考值,包括4项内容:平均需要量(EAR)、推荐摄入量(RNI)、适宜摄入量(AI)和可耐受最高摄入量(UL)。

二、有关DRIs的基本概念1、平均需要量(EAR,Estimated Average Requirement)EAR是根据个体需要量的研究资料制订的;是根据某些指标判断可以满足某一特定性别,年龄及生理状况群体中50%个体需要量的摄入水平.这一摄入水平不能满足群体中另外50%个体对该营养素的需要。

EAR是制定RDA的基础。

入量(RNI,Recommended Nutrient Intake)2、推荐』RNI相当于传统使用的RDA,是可以满足某一特定性别,年龄及生理状况群体中绝大多数(97%〜98%)个体需要量的摄入水平。

长期摄入RNI水平,可以满足身体对该营养素的需要,保持健康和维持组织中有适当的储备。

RNI的主要用途是作为个体每日摄入该营养素的目标值。

RNI是以EAR为基础制订的。

如果已知EAR的标准差,则RNI定为EAR加两个标准差,即RNI 二EAR+2SD。

如果关于需要量变异的资料不够充分,不能计算SD时,一般设EAR的变异系数为10%,这样RNI = 1.2 X EAR。

3、适宜摄入量(AI,Adequate Intakes)在个体需要量的研究资料不足不能计算EAR,因而不能求得RNI时,可设定适宜摄入量&1)来代替RNI。

AI是通过观察或实验获得的健康人群某种营养素的摄入量。

例如纯母乳喂养的足月产健康婴儿,从出生到4—6个月,他们的营养素全部来自母乳。

母乳中供给的营养素量就是他们的AI值,AI的主要用途是作为个体营养素摄入量的目标。

AI与RNI相似之处是二者都用作个体摄入的目标,能满足目标人群中几乎所有个体的需要。

AI和RNI的区别在于AI的准确性远不如RNI,可能显著高于RNI。

中国居民膳食指南营养素参考摄入量

中国居民膳食指南是国家卫生健康委员会发布的一份指导人们健康饮食的重要文件。

其中,营养素参考摄入量是指人体在一定时间内所需的营养素摄入量,是保证人体正常生长发育和维持健康的基础。

下面我们来了解一下中国居民膳食指南中的营养素参考摄入量。

1能量:成年人每天需要的能量摄入量为2000-2500千卡,但具体摄入量还需根据个人身体情况、年龄、性别、体重、身高、体型、体力活动量等因素进行调整。

2.蛋白质:成年人每天需要的蛋白质摄入量为50-75克,其中动物蛋白质应占总蛋白质的30%左右。

3.脂肪:成年人每天需要的脂肪摄入量为25・30克,其中不饱和脂肪酸应占总脂肪的70%以上。

4.碳水化合物:成年人每天需要的碳水化合物摄入量为300-400克,其中应以复合碳水化合物为主。

5.膳食纤维:成年人每天需要的膳食纤维摄入量为25・30克,其中可溶性膳食纤维应占总膳食纤维的30%左右。

6.维生素:成年人每天需要的维生素摄入量为各种维生素的推荐摄入量,其中维生素C、维生素E、叶酸、维生素A、维生素D、维生素B1、维生素B2、维生素B6、维生素B12等为重要的维生素。

7.矿物质:成年人每天需要的矿物质摄入量为各种矿物质的推荐摄入量,其中钙、铁、锌、硒、钾、镁等为重要的矿物质。

中国居民膳食指南中的营养素参考摄入量是人们健康饮食的重要依据,我们应该根据自身情况合理搭配食物,保证每天摄入足够的营养素,从而维持身体健康。

每日所需矿物质的摄取量矿物质是人体健康所必需的营养物质之一,它们在维持人体正常生理功能、促进新陈代谢、维持酸碱平衡等方面发挥着重要作用。

每日所需矿物质的摄取量因人而异,受年龄、性别、生理状态、健康状况等多种因素的影响。

本文将就不同矿物质的功能及每日所需摄取量进行介绍,帮助读者更好地了解如何科学合理地摄入矿物质,维护身体健康。

1. 钙(Calcium)钙是构成人体骨骼和牙齿的主要矿物质,同时也参与神经传导、肌肉收缩、血液凝固等生理过程。

成年人每日推荐摄入量为1000毫克,孕妇和哺乳期妇女为1200毫克。

富含钙的食物有奶制品、豆类、坚果等。

2. 镁(Magnesium)镁是人体内参与酶活性、神经肌肉功能、骨骼健康等的重要矿物质。

成年男性每日推荐摄入量为400-420毫克,女性为310-320毫克。

富含镁的食物包括绿叶蔬菜、全谷类食品、坚果等。

3. 钾(Potassium)钾是维持细胞内外液平衡、神经肌肉功能正常的必需矿物质。

成年人每日推荐摄入量为2000毫克。

富含钾的食物有香蕉、土豆、豆类等。

4. 磷(Phosphorus)磷是构成骨骼、维持酸碱平衡、参与能量代谢等重要功能的矿物质。

成年人每日推荐摄入量为700毫克。

富含磷的食物有肉类、鱼类、奶制品等。

5. 铁(Iron)铁是合成血红蛋白、运输氧气的必需矿物质,缺铁会导致贫血等问题。

成年男性每日推荐摄入量为8毫克,女性为18毫克。

富含铁的食物有瘦肉、豆类、全谷类食品等。

6. 锌(Zinc)锌是维持免疫功能、促进伤口愈合、参与DNA合成等重要功能的微量元素。

成年男性每日推荐摄入量为11毫克,女性为8毫克。

富含锌的食物有肉类、海鲜、豆类等。

7. 碘(Iodine)碘是甲状腺激素合成的必需元素,对维持甲状腺功能、促进大脑发育等至关重要。

成年人每日推荐摄入量为150微克。

富含碘的食物有海鱼、海带、碘盐等。

8. 锰(Manganese)锰是参与骨骼形成、抗氧化等生理过程的微量元素。

我国营养学会膳食钙及维生素D参考摄入量1. 前言我国营养学会一直致力于制定科学合理的膳食营养参考摄入量,其中包括膳食钙及维生素D的摄入。

膳食钙及维生素D是人体生长发育和维持健康所必需的营养素,而其参考摄入量的制定对于指导民众合理膳食、调整饮食结构具有重要意义。

2. 膳食钙摄入量的制定我国营养学会关于膳食钙的参考摄入量主要依据人体对钙的需求量以及不同芳龄、不同生理状态下的钙的吸收率而确定。

据了解,不同人群对膳食钙的需求量存在差异,比如儿童、青少年期、孕妇和老年人等特定人群对钙的需求更为突出。

我国营养学会在确定膳食钙的参考摄入量时,不仅考虑到了基本的生理需求,更加注重了人群的特殊需求。

3. 维生素D参考摄入量的调整随着研究的不断深入,人们对维生素D的了解也逐渐加深,发现其在骨骼健康、免疫调节和心血管健康等方面的作用是不可忽视的。

我国营养学会在最新的膳食营养参考摄入量中对维生素D的推荐摄入量进行了适度调整,以更好地满足人体对维生素D的需求。

4. 个人观点和理解从我个人的角度来看,我国营养学会关于膳食钙及维生素D的参考摄入量制定所依据的是严谨的科学研究和临床实践,这为民众提供了科学合理的膳食指导,有利于调整饮食结构,改善营养状况,促进健康。

5. 总结回顾我国营养学会制定的膳食钙及维生素D的参考摄入量充分考虑到了人体的生理需求和不同人群的特殊需求,是一项科学的、有益于健康的举措。

我们应该根据这些科学的指导,合理搭配膳食,保证身体获得足够的膳食钙及维生素D,从而保持健康。

总结:本文围绕着我国营养学会关于膳食钙及维生素D的参考摄入量展开论述,从膳食钙摄入量的制定、维生素D参考摄入量的调整、个人观点和理解以及总结回顾等方面进行了深入探讨。

文章旨在通过科学系统地介绍这一主题,帮助读者更全面、深入地了解膳食营养中的重要营养素,从而指导大家更科学、合理地调整自己的膳食结构,保持身体健康。

膳食营养是维持人体健康的基础,其中膳食钙和维生素D作为重要的营养素,对于保持骨骼健康、免疫调节和心血管健康等方面起着不可替代的作用。

PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS 19

3 Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride1

Two university researchers presented information about Dietary Ref-erence Intake (DRI) research recommendations contained in the Calcium and Related Nutrients Report (IOM, 1997). Bess Dawson-Hughes of Tufts University, who served on the panel for the report, highlighted a number of research recommendations that were considered to be of ma-jor importance for each of the five nutrients covered in the report and then made some comments about progress in those areas. Bruce W. Hollis of Medical University of South Carolina focused on the dietary requirement for vitamin D, which is his area of research.

DRI REPORT ON CALCIUM AND RELATED NUTRIENTS Presenter: Bess Dawson-Hughes

Calcium Major research recommendations for calcium included defining (1) the impact of calcium intake on mineral metabolism and peak bone mass; (2) genetic and calcium intake interactions; (3) the impact of calcium intake by adults on skeletal end points and on nonskeletal end points

1This chapter is an edited transcript of remarks and slides by Drs. Bess Dawson-

Hughes and Bruce Hollis at the workshop. Comments made by Dr. Dawson-Hughes rep-resent a composite of input from many of the panel members including Stephanie Atkin-son, Steve Abrams, Bob Heany, Robert Rude, Connie Weaver, and Gary Whitford, and from James Penland (regarding magnesium). 20 DIETARY REFERENCE INTAKES

PREPUBLICATION COPY: UNCORRECTED PROOFS such as blood pressure, cancer risk, and diabetes; and (4) the impact of calcium intake on the risk of developing a first or recurrent kidney stone. The most notable progress is a much better understanding of the link between calcium intake and absorption, particularly in adolescents. In addition, data now relate some of the vitamin D polymorphisms to min-eral metabolism in children. Information from Goulding and others (1998) indicates that milk intake in childhood influences fracture rates both in childhood and later in life in women. The longest of several recent calcium intervention trials is a 7-year intervention study conducted by Matkovic et al. (2005). That study found that the bone mineral density of girls who were taller at the end of the 7-year interval benefited from supplementation. The results raise the ques-tion as to whether calcium intake should be set on the basis of body size, at least in children and adolescents. Racial differences in bone turnover and calcium metabolism have been described. Over the last nine years, numerous randomized con-trolled trials of adults have been published. The studies that had a pla-cebo group with a low calcium intake and a reasonable level of compliance generally have shown beneficial effects of calcium supple-mentation on bone. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) Study has looked at dairy food intakes to reduce blood pressure. Several studies identify a small (3% to 5%) inverse effect of calcium on weight. That is controversial, but there seems to be a low-level association. Data on the effect of high calcium intake on the occurrence of first kidney stone now are available from approximately 36,000 women in the Women’s Health Initiative. Reportedly, a comprehensive analysis of the stone risk is underway. The report by Borghi et al. (2002) provides data on associations of calcium intake and recurring stones. One recent 5-year calcium intervention trial (Prince et al., 2006) was conducted in western Australia. The trial included approximately 1,500 women with a mean age of 75 years. Usual calcium intakes averaged approximately 900 milligrams per day. This was a placebo-controlled trial in which the supplement provided 1,000 mg of calcium in the form of calcium carbonate. Table 3-1 shows that only about 57 percent of the subjects in the cohort had an adherence rate of 80 percent or higher. This actually is a fairly good degree of adherence for a very long intervention study. The subset of adherents had a statistically significant reduction in all fracture risk. Those in the intent-to-treat group had a similar trend, but it was not significant.