【ACCA】The Management of Tax Knowledge 税务知识管理

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:1011.76 KB

- 文档页数:60

acca p阶段选科ACCA(特许公认会计师)是欧洲最大的国际性会计师公会,也是全球最大的国际性会计师协会之一。

ACCA的学位是全球认可的,并且持有ACCA证书的会计师在全球范围内都享有很高的声望和就业机会。

在ACCA的职业道路上,学生需要通过三个不同的阶段,分别是知识阶段(F1至F9),技能阶段(P1至P7)和专业阶段(SBL、SBR和AFM等)。

在技能阶段,考生需要选择两门核心科目和两门选修科目,本文将为你介绍ACCA P阶段选科的相关内容。

ACCA P阶段的核心科目分为三个部分,分别是管理会计(Performance Management,P5)、财务报告(Financial Reporting,P2)和税务(Taxation,P6)。

管理会计主要涉及企业内部管理和决策,学生将学习成本分析、预算编制、投资评估等内容。

财务报告则着重于企业的财务报表,学生将学习国际财务报告准则(IFRS)和国际会计准则(IAS),以及如何分析和解读财务报表。

税务方面则涉及个人所得税、公司税等内容,学生将学习税务计算、税务规划和税务筹划等知识。

对于ACCA P阶段的选修科目,学生可以根据个人兴趣和职业规划选择。

以下是一些ACCA P阶段的选修科目供参考:1. 商业法(Corporate and Business Law,Pensions Law and Trust Law,International Law):该科目涉及商业法律的基本原则和实践。

学生将学习合同法、公司法、劳动法等内容,以及国际商法和养老金法等特定领域的法律规定。

2. 风险管理(Risk Management):风险管理主要关注企业的风险识别、评估和控制。

学生将学习风险管理的基本概念、方法和实践,以及如何制定和执行风险管理策略。

3. 多元专业实践(Multi-Choice Questions):这门科目涵盖了ACCA中各个领域的知识点,如财务管理、审计和内部审计、公司治理等。

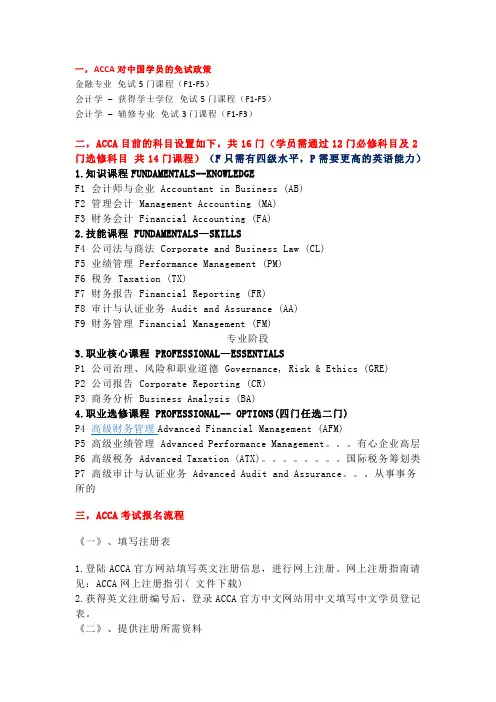

一,ACCA对中国学员的免试政策金融专业免试5门课程(F1-F5)会计学–获得学士学位免试5门课程(F1-F5)会计学–辅修专业免试3门课程(F1-F3)二,ACCA目前的科目设置如下,共16门(学员需通过12门必修科目及2门选修科目共14门课程)(F只需有四级水平,P需要更高的英语能力)1.知识课程FUNDAMENTALS--KNOWLEDGEF1 会计师与企业 Accountant in Business (AB)F2 管理会计 Management Accounting (MA)F3 财务会计 Financial Accounting (FA)2.技能课程 FUNDAMENTALS—SKILLSF4 公司法与商法 Corporate and Business Law (CL)F5 业绩管理 Performance Management (PM)F6 税务 Taxation (TX)F7 财务报告 Financial Reporting (FR)F8 审计与认证业务 Audit and Assurance (AA)F9 财务管理 Financial Management (FM)专业阶段3.职业核心课程 PROFESSIONAL—ESSENTIALSP1 公司治理、风险和职业道德 Governance, Risk & Ethics (GRE)P2 公司报告 Corporate Reporting (CR)P3 商务分析 Business Analysis (BA)4.职业选修课程 PROFESSIONAL-- OPTIONS(四门任选二门)P4 高级财务管理Advanced Financial Management (AFM)P5 高级业绩管理 Advanced Performance Management。

有心企业高层P6 高级税务 Advanced Taxation (ATX)。

acca 知识点总结As a globally recognized accountancy qualification, the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) offers an in-depth understanding of accounting, finance, and management. With its comprehensive syllabus and professional development opportunities, ACCA equips graduates with the knowledge, skills, and values required to build successful careers in the accounting industry. In this knowledge summary, we will explore the key topics covered in the ACCA qualification.Financial AccountingFinancial accounting is a fundamental aspect of the ACCA syllabus. It involves the preparation of financial statements, including the income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement. Candidates learn about the principles of double-entry accounting, accruals, and prepayments, as well as the accounting treatment of non-current assets, inventory, and financial instruments. They also gain an understanding of accounting regulations and standards, such as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).Management AccountingManagement accounting focuses on providing information to support decision-making within organizations. Candidates learn about cost classification, cost behavior, and cost-volume-profit analysis. They also study budgeting, variance analysis, and performance measurement techniques. In addition, they explore the role of management accounting in strategic planning, including the use of relevant costing and capital investment appraisal methods.Corporate and Business LawThis area of study covers the legal framework within which businesses operate. Candidates learn about contract law, company law, and employment law, as well as the regulations governing corporate governance and ethics. They also gain an understanding of the legal responsibilities of directors, shareholders, and creditors, and the implications of insolvency and liquidation.TaxationTaxation is a core component of the ACCA qualification, covering both personal and corporate taxes. Candidates learn about income tax, capital gains tax, and inheritance tax, as well as value-added tax and corporation tax. They also study the principles of tax planning, compliance, and ethical considerations in tax practice.Audit and AssuranceAuditing is a vital aspect of the accounting profession, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of financial information. Candidates learn about the principles of auditing, including theplanning, execution, and reporting phases. They also gain an understanding of internal control systems, risk assessment, and the ethical responsibilities of auditors.Financial ManagementFinancial management involves the strategic allocation of resources to maximize the wealth of shareholders. Candidates learn about the principles of investment appraisal, working capital management, and the cost of capital. They also study the theories of capital structure, dividend policy, and risk management, as well as the use of financial derivatives and hedging strategies.Performance ManagementPerformance management focuses on the measurement and evaluation of organizational performance. Candidates learn about key performance indicators (KPIs), balanced scorecards, and performance measurement frameworks. They also study the principles ofbehavioral aspects of performance management, including motivation, leadership, and team dynamics.Strategic Business ReportingStrategic business reporting involves the communication of financial and non-financial information to stakeholders. Candidates learn about the preparation and interpretation of financial statements, as well as the reporting requirements for sustainability and integrated reporting. They also gain an understanding of the ethical considerations in financial reporting and the implications of international developments in corporate reporting. Strategic Business LeadershipStrategic business leadership encompasses the skills required to lead and manage organizations effectively. Candidates learn about strategic management, including the development of corporate mission, vision, and values. They also study the principles of corporate governance, risk management, and business ethics, as well as the strategies for organizational change and transformation.Professional EthicsProfessional ethics is a fundamental aspect of the ACCA qualification, emphasizing integrity, objectivity, and ethical behavior in the accounting profession. Candidates learn about the fundamental principles of ethical behavior, as well as the application of ethical reasoning to real-world scenarios. They also gain an understanding of the ethical standards set by professional accounting bodies and the implications of ethical violations.In conclusion, the ACCA qualification provides a comprehensive understanding of accounting, finance, and management, preparing graduates for successful careers in the accounting industry. With its focus on technical knowledge, professional skills, and ethicalvalues, ACCA equips candidates with the expertise required to excel in the global business environment. Whether pursuing careers in public practice, industry, or the public sector, ACCA graduates are well-prepared to contribute to the success and sustainability of organizations worldwide.。

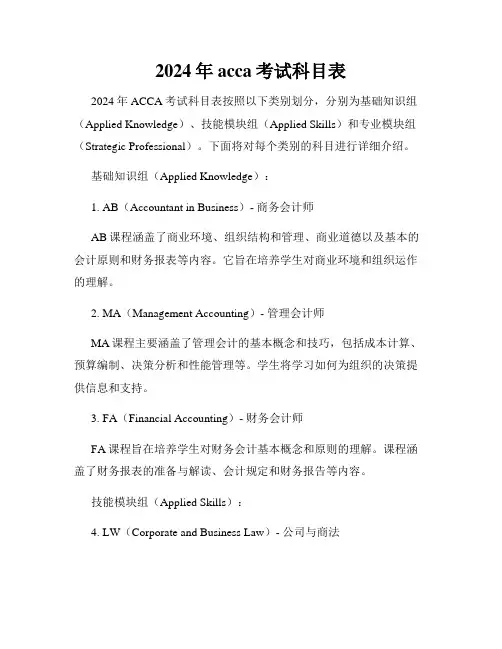

2024年acca考试科目表2024年ACCA考试科目表按照以下类别划分,分别为基础知识组(Applied Knowledge)、技能模块组(Applied Skills)和专业模块组(Strategic Professional)。

下面将对每个类别的科目进行详细介绍。

基础知识组(Applied Knowledge):1. AB(Accountant in Business)- 商务会计师AB课程涵盖了商业环境、组织结构和管理、商业道德以及基本的会计原则和财务报表等内容。

它旨在培养学生对商业环境和组织运作的理解。

2. MA(Management Accounting)- 管理会计师MA课程主要涵盖了管理会计的基本概念和技巧,包括成本计算、预算编制、决策分析和性能管理等。

学生将学习如何为组织的决策提供信息和支持。

3. FA(Financial Accounting)- 财务会计师FA课程旨在培养学生对财务会计基本概念和原则的理解。

课程涵盖了财务报表的准备与解读、会计规定和财务报告等内容。

技能模块组(Applied Skills):4. LW(Corporate and Business Law)- 公司与商法LW课程目标在于培养学生对公司法和商法的理解。

学生将学习相关法律及法规,并了解如何在商业环境中应用。

5. PM(Performance Management)- 绩效管理PM课程旨在培养学生运用管理会计工具和技术来评估和管理组织绩效的能力。

学生将学习如何进行预算和绩效评估等工作。

6. TX(Taxation)- 税务TX课程重点在培养学生理解税法和税务规定的能力,包括个人所得税、公司税和增值税等。

学生将学习税务计算和规划等技巧。

7. FR(Financial Reporting)- 财务报告FR课程涵盖了财务报告的准备和解读,涉及到国际财务报告准则(IFRS)的应用。

学生将学习编制复杂的财务报表和分析财务信息的方法。

acca f2考试大纲

ACCA F2考试大纲包括以下几个部分:

1、Management Accounting(管理会计):管理会计主要涉及企业内部的决策和绩效评估,包括成本会计、预算、绩效评估和业务决策等内容。

考试会考查考生对这些内容的理解、运用和分析能力。

2、Financial Accounting(财务会计):财务会计主要涉及企业对外报告的财务信息,包括财务报表的编制、财务报告和披露等。

考试会要求考生掌握这些规范,并能理解和评估企业对外发布的财务报表。

3、Taxation(税务):税务部分主要涉及企业税务的处理和合规问题,包括税法、税务规划和企业税务申报等内容。

考试将考查考生对税务法规、税务规划和企业税务处理的理解和应用能力。

4、Auditing(审计):审计部分主要涉及企业内部控制和外部审计的流程和标准,包括审计计划、风险评估和控制测试等内容。

考试会要求考生理解并掌握审计的流程和标准,并能理解和评估企业的内部控制和外部审计报告。

总体来说,ACCA F2考试大纲要求考生掌握管理会计、财务会计、税务和审计等方面的知识和技能,并能理解和应用这些知识解决实际问题。

考生需要全面了解各个部分的内容,并能够灵活运用所学知识进行案例分析和问题解决。

ACCA-F4知识要点汇总(精简版)1. 公司法律结构及管理公司的法律结构包括公司章程、股东协议、公司登记簿、董事会、股东大会、公司秘书等。

管理层需要遵守法律法规,同时也应该关注公司的社会责任和企业道德。

2. 公司财务及税务公司的财务部门需要负责编制财务报表、管理公司资金、进行预算和决策分析等。

税务部门需要负责申报税务、缴纳税款以及规划税务策略。

3. 合同法律框架合同是商业交易的基础,具有法律约束力。

合同的成立需要满足合同要素、合同内容的充分和明确、合同手续正确等条件。

合同的违约应该依法承担相应的法律责任。

4. 卖方和买方的权利与义务在商品的交易中,卖方需要履行交货、履行义务、提供货物信息等职责;买方需要履行付款、接收货物、检验货物、通知卖方等职责。

同时,卖方和买方也有权利保护自己的利益。

5. 银行融资银行融资是常见的企业融资方式,包括贷款、信用证、保函等。

企业在申请银行融资时需提供充分的资料和合理的担保措施,并在合同履行期内按期还款。

6. 国际贸易国际贸易的主体包括进出口商、代理商、货代、保险公司等。

在国际贸易中,涉及到的问题有贸易商信用、运输保险、海关手续等。

企业需要制定适应国际贸易的商业策略。

7. 合并与收购合并与收购是企业快速扩张的一种方式。

在进行合并与收购时,需要考虑战略目标、财务风险、员工合法权益等问题,并进行充分的财务、法律尽职调查。

8. 会计和审计会计和审计是公司财务管理的重要组成部分。

会计部门需要负责制定会计政策、编制财务报表等。

审计部门需要进行内部审核、外部审核等工作,并对财务报表的真实性和准确性进行评估。

acca afm单词手册以下是ACCA AFM(高级财务管理)中常用的一些英文单词和术语:1. Accounting:会计2. Finance:财务3. Management:管理4. Analysis:分析5. Reporting:报告6. Statement:报表7. Statement of Financial Position (Balance Sheet):财务状况表(资产负债表)8. Statement of Profit or Loss (Income Statement):利润表或损益表9. Statement of Changes in Equity:权益变动表10. Cash Flow Statement:现金流量表11. Notes to the Accounts:会计附注12. Audit:审计13. Assurance:保证14. Taxation:税务15. Valuation:估值16. Risk Management:风险管理17. Enterprise Risk Management (ERM):企业风险管理18. Internal Control:内部控制19. Governance:治理20. Shareholder Value:股东价值21. Enterprise Value:企业价值22. Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A):并购23. Divestiture:剥离24. Restructuring:重组25. Joint Venture:合资企业26. Private Equity:私募股权27. Initial Public Offering (IPO):首次公开发行28. Secondary Market Offering:二次市场发行29. Loan Facility:贷款融资30. Bond Issuance:债券发行31. Mutual Fund:共同基金32. Hedge Fund:对冲基金33. Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT):房地产投资信托基金34. Project Finance:项目融资35. Leveraged Buyout (LBO):杠杆收购36. Initial Coin Offering (ICO):首次代币发行37. Security Token Offering (STO):证券代币发行38. Contingency Planning:应急计划39. Pro forma Statements:预计报表40. Forecasting:预测41. Budgeting:预算编制42. Cost Management:成本管理43. Resource Allocation:资源配置44. Capital Expenditure (CapEx):资本支出45. Operating Expenditure (OpEx):运营支出46. Depreciation and Amortization:折旧和摊销47. Capital Structure:资本结构48. Dividend Policy:股息政策49. Shareholder Return on Investment (ROI):股东投资回报率50. Return on Equity (ROE):权益回报率。

ACCA F6知识点总结在2023年,ACCA F6考试将继续是很多学员的重要挑战。

F6考试侧重于税务方面的知识,涉及了许多复杂的税法和规定。

为了帮助考生更好地备战这一考试,下面将对ACCA F6的主要知识点进行总结和归纳。

一、纳税义务和居民身份1. 税务居民定义- 居住在国内的个人- 在国内有固定居所- 个人在国内居住180天以上的- 个人国内居住时间在2年以上的2. 纳税义务- 个人所得税- 营业税- 企业所得税- 增值税- 关税- 土地税二、个人所得税1. 个人所得税的计算- 确定税务居民身份- 计算应纳税所得额- 根据所得额确定纳税比例- 计算纳税金额- 申报纳税2. 税务减免- 公益捐赠- 教育支出- 医疗支出- 住房利息贷款三、公司税1. 企业所得税- 确定纳税所得额- 计算应纳税额- 申报纳税- 公司税务优惠政策2. 增值税- 税率和税基- 纳税申报- 增值税发票四、税务规划1. 个税规划- 个人所得税避税策略- 投资收益规划- 资产转移规划2. 公司税务规划- 利润转移- 投资资产安排- 跨国税务规划通过对以上知识点的总结和梳理,考生可以更清晰地了解ACCA F6考试所涉及的范围和重点。

在备战考试的过程中,考生需要特别关注每个知识点的细节和变化,同时也要结合实际情况进行深入理解和应用。

希望每一位考生都能够顺利通过ACCA F6考试,成为一名合格的财务税务专业人士。

祝各位考生取得优异的成绩,为自己的职业发展打下坚实的基础。

二、个人所得税3. 所得类别个人所得税的所得类别包括以下几种:- 工资薪金所得- 经营所得- 劳务报酬所得- 特许权使用费所得- 财产转让所得- 利息、股息、红利所得- 稿酬所得- 物业租赁所得- 财产保险所得- 税前抠除的养老金和退休金等4. 税前抠除在计算个人所得税时,个人可以享受税前抠除,降低应纳税所得额。

税前抠除主要包括以下项目:- 基本生活费、专项附加抠除和专项抠除- 子女教育、大病医疗等专项附加抠除- 购物商业健康保险的支出- 公积金、商业健康保险等社会保险的缴纳额。

ACCA考试共有15个考试科目,其中AB(F1)、MA(F2)、FA(F3)、LW(F4)、PM(F5)、TX(F6)、FR(F7)、AA(F8)、FM(F9)为F阶段课程,共9个科目,SBL、SBR、AFM(P4)、APM(P5)、ATX(P6)、AAA(P7)为P阶段课程,共6个科目。

ACCA课程中,F阶段科目全部为必修课,P阶段科目中SBL、SBR为必修课,其他为选修课(4选2参加考试),ACCA考试一共考过13科即可变成ACCA准会员。

考试之前一定要对ACCA有全面的了解,知己知彼方能百战不殆。

AB (F1)1英文名:Accountant in Business2中文名:会计师与企业3课程内容:主要是帮助无任何商业背景知识的学员初步建立人力资源、企业组织、商业环境及相互之间影响关系的相关知识内容。

内容涵盖:企业组织,公司管理,会计和报告体系,内部财务控制,人力资源管理,会计职业道徳。

4科目联系:AB(F1)是SBL课程中《公司治理,风险管理与职业道德》和《商务分析》的基础。

5考试时间:2小时(机考)6考试分值:A部分一一30道单选题(每题2分,共计60分)一一16道单选题(每题1分,共计16分)B部分一一情景为基础的6道多任务题(由单选、多选、判断题构成,每题4分,共计24分)7课程难度:☆☆8时间花费:☆☆☆2019年全球平均通过率:82.50%MA (F2)1英文名:Management Accounting2中文名:管理会计3课程内容:主要向学员介绍了管理会计体系的主要元素以及管理会计如何发挥支持企业决策, 制定企业决策的作用。

内容涵盖:管理会计,管理信息,成本会计,预算和标准成本,业绩衡量,短期决策方法。

4科目联系:MA(F2)《管理会计》是PM(F5)《业绩管理》和APM(P5)《高级业绩管理》的基础。

5考试时间:2小时(机考)6考试分值:A部分一一35道单选题(每题2分,共计70分)B部分一一3道多任务题(由计算、简单、论述题构成,每题10分,共计30分)7课程难度:☆☆8时间花费:☆☆☆2019年全球平均通过率:65.00%FA (F3)1英文名:Financial Accounting2中文名:财务会计3课程内容:主要向学员介绍了财务会计准则、相关会计科目账户建立以及准确财务信息的提供。

acca考试科目acca考试科目主要分为两个阶段,共包含四个模块。

其中基础课程的科目主要包括商业与技术、管理会计、财务会计、公司法与商法等等;专业课程的科目主要包括战略商业报告、战略商业领袖、高级财务管理等等。

acca一共有15门课程,只需要通过13门即可获得证书。

acca考试科目主要分为两个阶段,共包含四个模块。

第一部分就是基础阶段:该阶段主要分成两个部分:科学知识课程和技能课程。

科学知识课程主要牵涉财务会计和管理财务会计的核心科学知识,并为下一技能阶段的详尽自学构建平台。

具体内容科目设置如下:商业与技术business and technology,简称为bt。

管理财务会计management accounting,缩写为ma。

财务会计financial accounting,简称为fa。

公司法与商法corporate and business law,缩写为lw。

业绩管理 performance management,简称为pm。

税务taxation,缩写为tx。

财务报告financial reporting,简称为fr。

审计工作与证书业务audit and assurance,缩写为aa。

财务管理financial management,简称为fm。

第二部分就是专业课程:该阶段主要分成核心课程和报读(afm,apm,atx,aaa四挑选二)课程。

此阶段的课程等同于硕士课程的难度,这是课程第一部分的扩展和发展。

此阶段的课程引进了作为高级会计师所需的更高级的职业技能和知识技能。

报读课程为专门从事高级管理咨询或顾问职业的学员,设计了化解更高级和更繁杂的问题的技能。

具体内容科目设置如下:战略商业报告strategic business report,简称为sbr。

战略商业领袖strategy business leader,缩写为sbl。

高级财务管理advanced financial management,简称为afm。

ACCA F阶段知识整理ACCA考试科目一共有13门,其中F阶段考试科目一共占了9门课程,其中的重要性不言而喻,那么F阶段和P阶段有什么关联呢?P阶段应该如何选择呢?带着这些疑问一起和高顿ACCA来看看吧。

给大家整理了一套电子版ACCA备考资料,里面有很多ACCA考试资料可供大家选择。

而且在对于上班族来说,电子版的也很适合在地铁上查阅:电子版ACCA 备考资料F1 Accountant in Business这一门倾向于管理方面,课程难度不大,很多常识性的知识点,但是毕竟是ACCA第一门考试,所以刚开始大多数同学都会对很多专业词汇的英文表述不熟悉,加上F1中的知识点比较细碎,因此加大了学习的难度。

建议大家把每章的知识点自己做一个梳理总结,每一章节整理出大框架,可以很好地帮助本科的学习。

F2 Mangement Accounting这一门课是管理会计,课体总体难度不大,差异分析的部分可能有些难度,另外一些财务比率的计算需要掌握,为以后的学习打好基础。

F3 Financial Accounting这一门课是财务会计,属于基础会计学,其中会涉及到会计科目、会计分录、丁字账、试算平衡表等等一系列会计基础知识,对于没有会计基础的同学一开始会觉得一头雾水,但是入了门之后这门课程难度并不算大。

这一门课程是之后F7和P2的学习基础,一定要掌握知识点,同时积累英语专业词汇。

F4 Corporate and Business Law英美法系和大陆体系的不同在于他们使用的是判例法,因此F4中涉及到不同年代各种法律案例,并且有很多专业词汇。

以判例法为主考试难度感觉是在上升,但是通过率在上升F5 Performance Management这门课是管理会计的进阶,对于F2基础打得好的同学拿下这门课应该不在话下。

这门课程总体难度不大,重点在于掌握不同成本法及业绩评价方法的应用。

F6 Taxation这门课90%以上都是计算,是中国考生最拿手的地方。

acca科目分类ACCA科目分类ACCA(Association of Chartered Certified Accountants,特许公认会计师协会)是一家提供国际专业会计资格认证的机构。

ACCA 认证是会计和财务领域的国际金字招牌,被公认为国际上最具影响力和公信力的会计师资格之一。

ACCA考试分为基础阶段和专业阶段,基础阶段主要是财务与管理会计的基础知识,而专业阶段则涵盖了更加深入和专业的会计领域。

下面将对ACCA科目进行详细分类和介绍。

基础阶段1. F1 - Accountant in Business该科目主要涵盖了会计专业人士所需的商业理解和组织管理的基本知识。

学习者将了解组织结构、管理层决策、财务管理等方面的基础知识。

2. F2 - Management Accounting管理会计是管理层通过分析和评估各种会计数据来支持管理决策的过程。

学习者将学习成本估算、预算编制、组织绩效评估等管理会计的基本原理。

3. F3 - Financial Accounting财务会计是一门重要的会计学科,专注于公司财务报表的准备和分析。

学习者将学习资产负债表、利润表和现金流量表等财务报表的编制和解读。

4. F4 - Corporate and Business Law该课程主要涵盖商法和公司法方面的内容。

学习者将了解法律对商业和公司运营的影响,以及相关法律规定下的商业伦理问题和道德要求。

专业阶段1. Essentials Module - 必修科目F5 - Performance Management该科目主要涵盖了管理会计和业绩管理的高级概念和技术。

学习者将学习如何使用会计数据和管理信息来评估和改善组织的绩效。

F6 - Taxation税务是一个重要的财务领域,涉及到纳税义务和税务计划。

学习者将学习不同国家的税法、个人和公司的税务义务以及相应的优化措施。

F7 - Financial Reporting财务报告为公司和利益相关方提供了有效的财务信息。

Chapter 1 Introduction to the UK tax system1.HMRC:Her Majesty ’s Rvenue and Customs 英国税务海关总署2.factors affect tax policies:①econmic:whole;factors;behavior(donation,investment,saving,build own business,drink,fuel);②social:缩小贫富差距;③environment3.progressive taxation:income tax 随财富增加税率变高Regressive taxation:fuel duty 随财富减少税率变高Proportional taxation:财富增加比率不变,是固定数 Ad Valorem :增值税4.direct and indirect (VAT) taxes .5.treasure(财政局),chancellor of the exchequer,HMRC,Tribunal(first,upper),遵从欧盟规则6.避收两次税:避收两次;避免歧视;避免逃税漏税7.tax evasion(illegal) and tax avoidance(legal:abusive arrangement,tax mitigation)8.出现违反:告知;不改的话不予受理;报告单不能透露信息9.ISA :限额15000,存款投资股票免税(利息不用交个人所得,资产利得不用交税),亏损不能抵减。

Chapter 2 Introduction to Crporation Taxpany residence:place of incorporation 注册地:①UK;②Overseas(central management in UK)2.period of account(会计期,可长于/短于12个月) and chargeable accounting period(应税会计期,不能超过12个月,会计期大于12月时拆分)★3.financial year:FY 2014 01/04/2014-31/03/2015▲4.proforma of corporation tax computationFII:免税投资收入:①dividend(另一UK 公司,海外公司,unconected company(<50% share holding);②FII=dividends received from unconnected companies/90%★5.MR=standard fraction*(upper limit-augmented profit)*TTP/augmented profit6.大于12个月的拆分:①按期间:trading profit,property business income②按具体发生日期:interest income,chargeable gain,qualifying charitable donation,FIICapital allowance:计算每一个期间的capital allowance 后加总7.小于12个月:按比例:upper limit and lower limit 同样按比例减小8. associatied company:>50% share capital,>50% voting rights,>50% profit pr netAsset on winding up(结束).注意:Both UK and overseas,dormant companies excluded,一段时间为associated company 视为整个期间都是associated;Associated company dividend is not include FIIChapter 3 trading profit▲1.proforma for tax adjusted trading profits★2.decutible and non-decuctible(完全,唯一) 两个目的中有一个目的与金融无关,不可扣 ①fine 罚款(停车除外);②depreciation;③capital expenditure(性能有提升,不可扣),revenue expenditure(无提升,可扣)买破房,不翻新无法使用,CE;翻新前也可以使用RE,换烟囱,RE④lease car(租车):≤130g/km 全可扣,>130:15%不可扣⑤entertain and gift:employee deductible;customer(不可扣,除非:一年一人不超过50磅/不是实务研究代金券/gift 有给公司打广告⑥donation:可扣减三要素:trading purpose,local,给教育宗教文化慈善组织不满足三条件时,放在QCD 里面扣掉政治捐款不可扣,也不能放在QCD 里面扣★⑦legal fee:可扣:应收账款的催付,贷款用于经营,商标注册,短租续租,保护域名,起诉违约,会计审计费,版税不可扣:发行股票,被别人起诉,初次短期租约,与capital expenditure 相关的⑧debt:only 赊销未还可扣(即staff 不行),确认坏账又收到了算在other income 里⑨other:培训,商业会费,经营前7年内,裁员补偿,咨询服务3.Capital allowance:a businesstax relief for capital expenditure on qualifying asset.It coverd for expenditure on plant and machinery,and is given to the net cost of asset(original cost-disposal value)4.plant and machinery:land building and structures are not plant.so as walls,floors,ceilings,doors,gates,shutters,windows.①main pool:大多数资产,car with CO2 96g/km-130g/km②special rate pool :long life asset(≥25years,total cost of at least 100000 for 12 month),房间自带体系,cars with CO2>130g/km③short-life asset:预备8年内出售;购买资产的accounting period结束后两年内去税务局做认定(对unincorporate business,会计期结束后的1年内的1月31日之前);计算CA时单列,使用结束后计算balancing charge or balancing allowance;8年后仍在用转化为main pool;AIA5.WDA(writing down value.for still use,reducing balance basis余额递减法)Main pool-18% special pool-8% short life asset-18%(年折旧比率)6.AIA(annual investment allowance,for newly required) exception of motor carsProvide alloance of 100% for the first 500000 of expenditure(针对12个月)抵减顺序:SP→MP→SLA★7.motor car:针对于低排量(≤95g/km)汽车。

acca管理会计内容

ACCA管理会计的内容主要涵盖管理会计、管理信息、成本会计、预算和标准成本、业绩衡量、短期决策方法等内容。

这些内容通过ACCA的考试科

目《管理会计》进行考查。

ACCA的考试分为三个阶段,分别是应用知识模块、应用技能模块和战略专业模块。

在应用知识模块中,《商业与科技》、《管理会计》和《财务会计》是重要的科目。

此外,ACCA的专业课程内容通常包括财务会计和管理会计,涉及财务报告、财务管理、审计、税务、成本控制和预算等不同领域。

这些课程还涵盖了业务沟通和沟通技能、信息技术、战略和投资决策、商业法律和伦理等多个方面。

如需获取更详细的信息,建议查看ACCA官方网站或者咨询相关专业的教师。

npo acca知识点ACCA是全球性的财务会计职业资格证书,该证书为财务和会计领域的专业人士提供了广泛的知识和技能,有助于他们在全球范围内寻求职业发展和提升职业水平。

下面将会介绍ACCA考试中的知识点。

1. 会计原则及概念会计原则是指财务会计领域的基本规则,包括货币计量原则、确认实现原则、相对性原则、谨慎原则和连续性原则。

会计概念则包括企业实体概念、会计期间概念、会计基础概念、会计报表稳健性概念。

这些概念和原则是财务会计的基础,它们有效地确保了财务报表的精确性和透明度。

2. 财务报表财务报表包括资产负债表、利润表和现金流量表。

资产负债表显示企业的资产、负债和股东权益的状态。

利润表显示企业在会计期间的营业额、成本、费用和净收益。

现金流量表显示企业在会计期间现金流入和现金流出的情况。

这些报表是企业的关键财务信息来源,对于管理、投资和决策都至关重要。

3. 税收ACCA考试也涉及许多税收问题,包括企业税收和个人税收。

其中,涉及到的主要税种有:所得税、增值税、消费税、遗产税和赠与税等。

纳税人需要了解不同税种的纳税规则、计算和申报过程,以及相关税收法律的各项规定等。

4. 预算与成本管理预算和成本管理是企业的关键管理工具,涉及到企业的预算编制、绩效评估、成本分析和控制等方面。

ACCA考试中,还会重点考察预算及其编制、成本分类、成本控制、成本核算等内容,这些知识点对于企业的经营决策和管理都至关重要。

5. 风险管理风险管理是指在不确定的环境下,有效地管理和控制企业面临的各种风险。

ACCA考试中会涉及到的相关知识点有风险评估、风险识别、风险控制和风险管理策略等。

这些知识点对于企业稳健发展和风险防范至关重要。

总之,ACCA考试的知识点非常广泛,主要涵盖了财务和管理领域的各个方面。

ACCA的职业资格证书主要是面向财务和会计专业人士,全球化的认可度极高。

对于想要在财务和会计领域发展的人来说,取得ACCA资格证书是非常有价值的。