59. Cerebrovasc Dis 09

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:181.24 KB

- 文档页数:10

rehabilitation :patterns of disability scale usage in clinical trials 〔J 〕.Int J Rehabil Res ,2005;28(2):135-9.3Houlden H ,Edwards M ,McNeil J ,et al .Use of the Barthel index and the functional independence measure during early inpatient rehabilitation af-ter single incident brain injury 〔J 〕.Clin Rehabil ,2006;20(2):153-9.4de Los Ríos la Rosa F ,Khoury J ,Kissela BM ,et al .Eligibility for intrave-nous recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator within a population :the effect of the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS )ⅢTrial 〔J 〕.Stroke ,2012;43(6):1591-5.5Kleindorfer D ,Kissela B ,Schneider A ,et al .Eligibility for recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in acute ischemic stroke :a population-based study 〔J 〕.Stroke ,2004;35(2):e27-9.6Knickerbocker DL ,Lutz PL.Slow ATP loss and the defense of ion homeo-stasis in the anoxic frog brain 〔J 〕.J Exp Biol ,2001;204:3547-51.7Broadley SA ,Thompson PD.Time to hospital admission for acute stroke :an observational study 〔J 〕.Med J Aust ,2003;178(7):329-31.8Desseigne N ,Akharzouz D ,Varvat J ,et al .What are the crucial factors af-fecting the time to admission of patients with suspected stroke to the e-mergency department〔J 〕?Presse Med ,2012;41(11):e559-67.9毕齐,张茁,张微微,等.北京等15个城市脑卒中患者院前时间及影响因素研究〔J 〕.中华流行病学杂志,2006;27(11):996-9.10Boden-Albala B ,Quarles cation strategies for stroke prevention 〔J 〕.Stroke ,2013;44:S48-51.11Flaherty ML ,Kleindorfer D.Public stroke awareness and education pub-lic awareness of stroke is improving 〔J 〕.Semin Cerebrovasc Dis Stroke ,2004;4(3):130-3.12Li CH ,Khor GT ,Chen CH ,et al .Potential risk and protective factors for in-hospital mortality in hyperacute ischemic stroke patients 〔J 〕.Kaohsi-ung J Med Sci ,2008;24(4):190-6.13Lorravne N ,Graing LE ,Weir CJ ,et al .The Evidence-base for stroke ed-ucation in care homes 〔J 〕.Nurse Edu Today ,2008;28(7):829-40.14Davis SM ,Donnan GA.Secondary prevention after ischemic stroke ortransient ischemic attack〔J 〕.N Engl J Med ,2012;366(20):1914-22.15Pezzini A ,Grassi M ,Del Zotto E ,et al .Complications of acute stroke and the occurrence of early seizures 〔J 〕.Cerebrovasc Dis ,2013;35(5):444-50.〔2012-09-18收稿2013-02-19修回〕(编辑赵慧玲)塞来昔布治疗骨关节炎患者的有效性和安全性杨玉鹏田烨(广西医科大学第一附属医院骨关节外科,广西南宁530021)〔摘要〕目的探讨塞来昔布治疗骨关节炎的有效性和安全性。

氯吡格雷预防急性脑梗死复发的临床研究【关键词】氯吡格雷;急性脑梗死复发;预防doi:10.3969/j.issn.1004-7484(x).2012.06.056 文章编号:1004-7484(2012)-06-1257-02心脑血管疾病的发病率高,死亡率高,致残率高,而康复却及其缓慢,随着我国步入老龄化社会,这类疾病的发病人数明显的呈上升趋势,已经引起了人们的高度重视。

心脑血管疾病的基本病理变化是动脉粥样硬化,而动脉粥样硬化是可致残致死的全身性疾病,青少年开始发病,中老年发生致残致死,是人类健康和生命的头号杀手。

心脑血管疾病引发的心脑血管事件主要为缺血性事件,决定心脑血管事件不是动脉粥样硬化所致的血管狭窄程度,而是决定于动脉血栓形成。

缺血性事件是临床上动脉血栓形成性疾病患者的主要死亡原因,缺血性卒中患者年复发率可达14%[1],存活者常常遗留严重的功能缺损,要改善这类患者的预后,减少死亡率,防治血栓形成就显得极为重要。

而血小板活化在血栓形成中有着重要作用,故临床上常用包括抗血小板药在内的综合措施预防缺血性事件的发生。

1 资料与方法1.1 一般资料 2006年1月至2007年2月我院神经内科收治的首发缺血性脑血管病患者60例,年龄45-75岁,其局灶性神经功能缺损是由动脉血栓性原因引起,均符合第四届全国脑血管会议制定的诊断标准[2]。

经头颅ct或mri证实有严重心、肝、肾疾病、近期手术及活动性出血者排除在外。

随机分为氯吡格雷治疗组(氯吡格雷组)与阿司匹林治疗对照组(阿司匹林组)。

氯吡格雷组30例,男17例,女13例;阿司匹林组30例,男16例,女14例。

1.2 治疗方法 60例患者入院后均根据病情给予脑保护剂、改善脑循环等药物治疗及对症处理。

在此基础上氯吡格雷组给予氯吡格雷(泰嘉,深圳信立泰公司)50mg/d口服,每天1次;阿司匹林组给予肠溶阿司匹林75mg/d口服,每天1次;住院治疗2-3周后,门诊随访12个月。

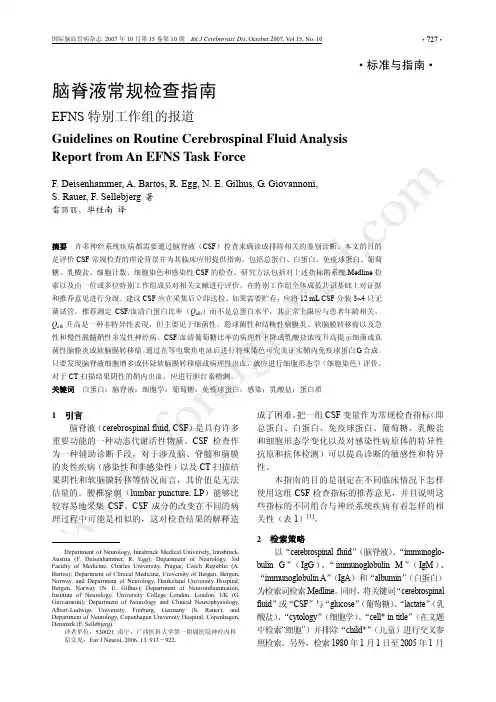

·标准与指南· 脑脊液常规检查指南EFNS特别工作组的报道Guidelines on Routine Cerebrospinal Fluid AnalysisReport from An EFNS Task Force表1 某些神经系统疾病CSF指标改变的典型表现总蛋白(g/L)葡萄糖比率(mmol/L)乳酸盐细胞计数典型的细胞学(每3.2 μL)正常值*<0.45>0.4~0.5<1.0~2.9<15MNC疾病急性细菌性脑膜炎↑↓↑>1 000PNC病毒性神经系统感染(脑膜炎/脑炎)=/↑=/↓=10~1 000PNC/MNC自身免疫性多发性神经病↑===感染性多发性神经病↑==↑MNC蛛网膜下腔出血↑==↑红细胞、巨噬细胞、含铁血黄素吞噬细胞、MNC多发性硬化====/↑MNC软脑膜转移瘤↑=/↓NA=/↑癌细胞、MNCCSF:脑脊液;MNC:单核细胞;PNC:多形核细胞;↑/↓:增高/降低;=:在正常范围内;NA:无证据*成年人腰穿CSF的正常值1日期间摘要中含有“cerebrospinal fluid”和“immunoglobulin”和“diagnosis”(诊断)和“electrophoresis”(电泳)或“isoelectric focusing”(等电聚焦)的英文文献(274篇文献)。

以“cerebrospinal fluid”和“infectious”(感染性)作为检索词并限定时间(1980年1月1日至今)进行检索,得到560篇文献。

摘要未涉及诊断问题和感染性CSF(如非感染性炎性疾病、疫苗接种、CSF一般参数、病理生理学、细胞因子和治疗)的文献被排除在外,结果得到60篇摘要。

以“cerebrospinal fluid”和“serology”(血清学)作为检索词并限定时间(1980年1月1日至今)进行检索并排除与主题无直接联系的文献后得到35篇文献,以“cerebrospinal fluid”和“bacterial culture”(细菌培养)作为检索词并限定时间(1980年1月1日至今)检索后得到28篇摘要。

经颅多普勒发泡实验对卵圆孔未闭的诊断价值卵圆孔未闭(patentforamenovale,PFO)是房间隔的一种先天发育缺损。

人群中约有1/4存在PFO [1]。

一般情况下,卵圆孔未闭不引起心房间分流,不需外科手术,但近年来发现卵圆孔未闭引起反常栓塞机制与缺血性脑卒中的发生密切相关,卵圆孔未闭可导致脑栓塞的病因也渐有报告,两者之间有着重要的关联,尤其是小于55岁的青年卒中。

PFO与隐源性缺血性脑卒中有着密切的关系,PFO 可作为来自静脉循环”反常性栓子”的通道导致脑梗死[2]。

常用的PFO的检测方法有经胸超声心动图(TTE)、经食道超声心动图(TEE)以及经颅多普勒超声微泡实验(contrast enhanced transcranial Doppler,c-TCD)3种检查。

经食管超声心动图TEE是目前PFO诊断金标准,但TEE为侵人性操作,限制了其应用。

近来的研究表明,c-TCD可作为PFO的无创筛查手段,它具有无创、简单、易行等优点。

随着技术的完善,此种方法被认为可替代TEE[3]。

本综述探讨c-TCD 微泡实验的方法及对PFO的诊断作用价值。

1 卵圆孔未闭的形成在胎儿期的卵圆孔作为一个生理通道,允许血液自右心房流人左心房,维持胎儿血液循环。

出生后,随着肺循环的建立,左房血流和压力增高,引起卵圆孔功能性关闭。

多数人在出生后5~7个月左右,继发隔和原发隔互相融合在一起,原发隔从左房侧封闭卵圆孔形成永久性房问隔。

卵圆孔完全闭合者在1岁儿童只占18%,2岁时占50%。

成人尸检发现约25%~34%卵圆窝部两层隔膜未完全融合,中间存在一个永久性的裂缝样缺损,形成卵圆孔未闭。

2 卵圆孔未闭与反常栓塞反常栓塞被认为是:①无左侧血栓来源;②潜在的右向左分流;③静脉系统或右房检测到血栓等栓塞事件的原因。

临床已发现脑血栓、气体栓塞或脂肪栓塞和潜水时发生的神经减压病都与反常栓塞有关。

当存在导致右心房压力升高的疾病时,升高的右心房压力会使卵圆孔重新开放,产生右向左分流。

急性缺血性脑卒中大血管闭塞血管内治疗新进展郭旭1.缪中荣2专家简介:缪中荣,首都医科大学附属北京天坛医院神经介入中心主任,教授、主任医师、博士生导师。

北京市第十五届人大代表,享受国务院政府特殊津贴。

现任中国卒中学会常务理事,中国卒中学会神经介入分会主任委员,中国医师协会神经介入专业委员会副主任委员,中国抗衰老促进会神经系统疾病专业委员会副主任委员、中国老年学会脑血管病分会副主任委员、中华预防医学会卒中预防控制委员会介入治疗组组长、北京医学会神经介入分会主任委员、北京脑血管病临床研究中心首席专家、中国科协全国神经介入脑血管病介入治疗学首席科学传播专家、《神经介入在线》主编。

长期从事缺血性脑血管病血管内治疗的临床工作。

从2000年开始专攻缺血性脑血管病介入治疗,迄今为止累计完成颅内外动脉血管内治疗手术8000余例,在缺血性脑血管病介入手术治疗方面具有丰富经验。

主持国家级和省部级科研课题多项,组织编写缺血性脑血管病专家共识及指南多个。

发表学术论著300余篇,其中SCI 收录50篇,累计影响因子156。

出版专著10余部,获国家专利4项。

获国家科学技术进步二等奖1项,中华医学科技奖三等奖1项,教育部科学技术进步一等奖1项,北京市科技进步奖3项。

撰写的科普读物《漫画脑卒中》获科技部2016年全国优秀科普作品奖、第四届中国科普作家协会优秀科普作品奖金奖、北京市科学技术三等奖,《熊猫医生和二师兄漫画医学1-6》获科技部2018年全国优秀科普作品奖。

在2016年“医药卫生界生命英雄推选活动”中被评选为“生命英雄”。

DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-816x.2020.01.011作者单位:100029 北京,首都医科大学附属北京安贞医院1;100070 北京,首都医科大学附属北京天坛医院2通讯作者:缪中荣,Email :zhongrongm@2019年6月,《Lancet Neurology 》杂志发布了1990~2017年中国及其各省急性缺血性卒中的死亡率、发病率和危险因素,2017年全球疾病负担研究的荟萃分析:与1990年相比,尽管中国卒中的每10万人年龄标准化残疾调整寿命年(disability-adjusted life-years, DAL Ys )降低了33.1%,但卒中是中国寿命损失年的第一位死因,与缺血性心脏病一样成为中国疾病负担最重的疾病[1]。

Review Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;27:280–289 DOI:10.1159/000199466

The Evaluation of Anosognosia in Stroke Patients

M.D.Orfei a C. Caltagirone a, b G. Spalletta a, b a IRCCS Santa Lucia Foundation and b Department of Neuroscience, University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome , Italy

Introduction Anosognosia is a self-awareness disorder which pre-vents brain-damaged patients from recognizing the pres-ence or appreciate the severity of deficits in sensory, per-ceptual, motor, behavioural or cognitive functioning, which are evident to clinicians and caregivers [1, 2].Inparticular, anosognosia following stroke [3]hasgainedimportance for its striking phenomenology, its incidence in the stroke population and because it is detrimental to the recovery and rehabilitation course [4–6].Thus,theassessment of anosognosia is fundamental. In fact, mod-ern conceptualizations of awareness deficits in brain-damaged patients highlight the complex and multilevel nature of these clinical phenomena [3] . For instance, the pyramidal model proposed by Crosson et al. [7] hypoth-esizes 3 possible levels of awareness deficits, with specific clinical and rehabilitative implications for each. In the last 30 years, a number of high-quality measures have been proposed, but most of them focus on specific as-pects, leaving other dimensions of anosognosia unex-plored. Thus, at present no single scale is able to fully explore all the components of poor awareness of deficit. This is a relevant issue from a clinical perspective, be-cause a lack of exhaustive diagnostic procedures may po-tentially affect the development of specific and efficient rehabilitation programmes. In addition, heterogeneous selection criteria and assessment modalities contribute to gather highly variable epidemiological data [3]andpre-vent a deeper knowledge of awareness processes and im-pairments.Key Words Anosognosia, assessment ؒ Stroke rehabilitation

Abstract Background: Anosognosia in stroke patients showed a rel-evant detrimental effect on the rehabilitation course andpatients’ quality of life, especially in those with brain injury. Although a number of reliable scales for the assessment of anosognosia in stroke and traumatic brain injury have been developed, at present no single measure fully explores the multifaceted nature of the phenomenon. Method: A Pub-Med search with appropriate terms was carried out in order to critically review the issue. Results: The main dimensions to consider in the investigation of anosognosia in brain-in-jured patients are (a) awareness of deficit and related func-tional implications, (b) modality specificity, (c) causal attribu-tion, (d) expectations of recovery, (e) implicit knowledge and (f) differential diagnosis with psychological denial. Time elapsed from stroke, aetiology, laterality, aphasia and clinical complications may influence all these characteristics and must be taken into consideration. Finally, an adequate asso-ciation of the anosognosia evaluation with other neuropsy-chological and behavioural aspects is relevant for a modern holistic approach to the patient. Conclusions: This review is meant to stimulate the development of a new comprehen-sive assessment procedure for anosognosia in brain injury and particularly in stroke, in order to catch the multidimen-sionality of the phenomenon and to shape rehabilitation programmes suitable to the specific clinical features of every single patient. Copyright © 2009 S. Karger AG, Basel

Received: December 17, 2007 Accepted: October 21, 2008 Published online: February 6, 2009

Gianfranco Spalletta, MD, PhD IRCCS Santa Lucia Foundation, Laboratory of Clinical and Behavioural Neurology Via Ardeatina 306IT–00179 Rome (Italy) Tel./Fax +39 06 5150 1575, E-Mail g.spalletta@hsantalucia.it

© 2009 S. Karger AG, Basel1015–9770/09/0273–0280$26.00/0

Accessibleonlineat:www.karger.com/ced Assessment of Anosognosia in Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2009;27:280–289281

This paper aims to draw attention to a number of is-sues to be considered in the assessment of anosognosia and to encourage the development of new and more ef-ficient diagnostic procedures able to fit modern knowl-edge on awareness phenomena. Thus, on the basis of the recent studies in this area, the most remarkable method-ological issues and specific clinical factors are listed and debated. For our purposes, the database was selected using Pubmed Services utilizing the key words ‘stroke’, ‘trau-matic brain injury’ and ‘anosognosia’. The bibliographies of all related articles were searched. All the pertinent lit-erature considered to be of relevant scientific interest by MDO and GS concerning the assessment of diagnosis and severity of anosognosia was selected. We chose a sample of studies, spanning from 1986 to 2007, to exam-ine some salient methodological issues ( table 1 ). Classical versus More Recent Approach to the Assessment of Anosognosia in Stroke The modern concept of anosognosia concerns a mul-tidimensional phenomenon which includes a wider range of related factors. This is quite evident in research on im-paired self-awareness in other medical conditions. For instance, causal attribution of the deficit, evaluation of functional implications in activities of daily living, ex-pectations of recovery, changes in various ability domains (sensorimotor, but also cognitive, behavioural and inter-personal) and adherence to the treatment are part and parcel of the definition of poor awareness of illness in traumatic brain injury (TBI), dementia and schizophre-nia, and as such they are commonly investigated [50].Incontrast, these dimensions are mostly disregarded in stroke, where the best-known questionnaires for anosog-nosia in stroke, such as Cutting’s questionnaire [51],Bisi-ach’s Scale [43] , the Anosognosia Questionnaire [8] ,the Anosognosia for Hemiplegia Questionnaire [52] and the Structured Awareness Interview [18] , are polarized on the awareness of sensorimotor deficit per se, consistently with the original definition of anosognosia [53] . In addi-tion, the complexity of an awareness deficit is supported by neuro-anatomic studies, which suggest that anosog-nosia is due to the impairment of a wide neural net in-cluding a number of cerebral circuits [54–57] . Thus, the development of a wider diagnostic perspec-tive on anosognosia in stroke, consistent with the recent evolution of the concept of anosognosia, is required. To date, the measures for anosognosia in stroke, although quite reliable, are not very diversified, as they are all based on the clinician’s judgement, provide very similar items