Technology regimes and new firm formation

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:164.02 KB

- 文档页数:18

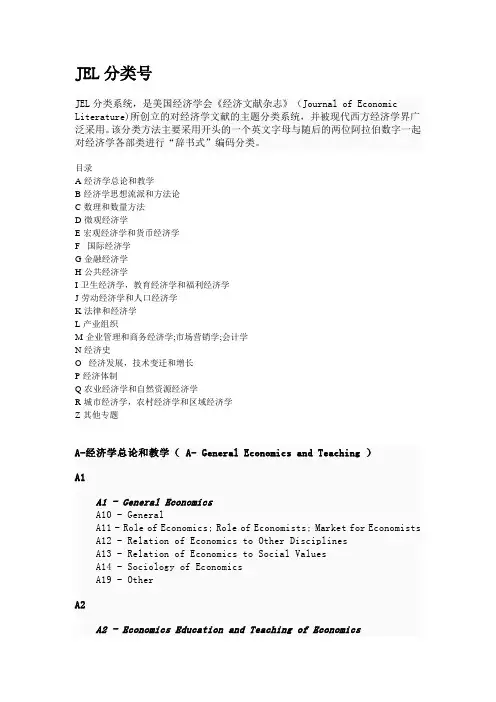

JEL分类号JEL分类系统,是美国经济学会《经济文献杂志》(Journal of Economic Literature)所创立的对经济学文献的主题分类系统,并被现代西方经济学界广泛采用。

该分类方法主要采用开头的一个英文字母与随后的两位阿拉伯数字一起对经济学各部类进行“辞书式”编码分类。

目录A-经济学总论和教学B-经济学思想流派和方法论C-数理和数量方法D-微观经济学E-宏观经济学和货币经济学F- 国际经济学G-金融经济学H-公共经济学I-卫生经济学,教育经济学和福利经济学J-劳动经济学和人口经济学K-法律和经济学L-产业组织M-企业管理和商务经济学;市场营销学;会计学N-经济史O- 经济发展,技术变迁和增长P-经济体制Q-农业经济学和自然资源经济学R-城市经济学,农村经济学和区域经济学Z-其他专题A-经济学总论和教学( A- General Economics and Teaching )A1A1 - General EconomicsA10 - GeneralA11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists A12 - Relation of Economics to Other DisciplinesA13 - Relation of Economics to Social ValuesA14 - Sociology of EconomicsA19 - OtherA2A2 - Economics Education and Teaching of EconomicsA20 - GeneralA21 - Pre-collegeA22 - UndergraduateA23 - GraduateA29 - OtherA3A3 - Multisubject Collective WorksA30 - GeneralA31 - Multisubject Collected Writings of IndividualsA32 - Multisubject VolumesA39 - OtherB-经济学思想流派和方法论( B-Schools of Economic Thought and Methodology )B0B0 - GeneralB00 - GeneralB1B1 - History of Economic Thought through 1925B10 - GeneralB11 - PreclassicalB12 - ClassicalB13 - Neoclassical through 1925B14 - Socialist; MarxistB15 - Historical; InstitutionalB16 - QuantitativeB19 - OtherB2B2 - History of Economic Thought since 1925B20 - GeneralB21 - MicroeconomicsB22 - MacroeconomicsB23 - Econometrics; Quantitative StudiesB24 - Socialist; MarxistB25 - Historical; Institutional; Evolutionary; Austrian B29 - OtherB3B3 - History of Thought: IndividualsB30 - GeneralB31 - IndividualsB4B4 - Economic MethodologyB40 - GeneralB41 - Economic MethodologyB49 - OtherB5B5 - Current Heterodox ApproachesB50 - GeneralB51 - Socialist; Marxian; SraffianB52 - Institutional; EvolutionaryB53 - AustrianB59 - OtherC-数理和数量方法(C-Mathematical and Quantitative Methods)C0C0 - GeneralC00 - GeneralC1C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: GeneralC10 - GeneralC11 - Bayesian AnalysisC12 - Hypothesis TestingC13 - EstimationC14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric MethodsC15 - Statistical Simulation Methods; Monte Carlo Methods; Bootstrap MethodsC16 - Specific DistributionsC19 - OtherC2C2 - Econometric Methods: Single Equation Models; Single VariablesC20 - GeneralC21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect ModelsC22 - Time-Series ModelsC23 - Models with Panel DataC24 - Truncated and Censored ModelsC25 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice ModelsC29 - OtherC3C3 - Econometric Methods: Multiple/Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple VariablesC30 - GeneralC31 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect ModelsC32 - Time-Series ModelsC33 - Models with Panel DataC34 - Truncated and Censored ModelsC35 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice ModelsC39 - OtherC4C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special TopicsC40 - GeneralC41 - Duration AnalysisC42 - Survey MethodsC43 - Index Numbers and AggregationC44 - Statistical Decision Theory; Operations ResearchC45 - Neural Networks and Related TopicsC49 - OtherC5C5 - Econometric ModelingC50 - GeneralC51 - Model Construction and EstimationC52 - Model Evaluation and TestingC53 - Forecasting and Other Model ApplicationsC59 - OtherC6C6 - Mathematical Methods and ProgrammingC60 - GeneralC61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic AnalysisC62 - Existence and Stability Conditions of EquilibriumC63 - Computational TechniquesC65 - Miscellaneous Mathematical ToolsC67 - Input–Output ModelsC68 - Computable General Equilibrium ModelsC69 - OtherC7C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining TheoryC70 - GeneralC71 - Cooperative GamesC72 - Noncooperative GamesC73 - Stochastic and Dynamic Games; Evolutionary GamesC78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching TheoryC79 - OtherC8C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer ProgramsC80 - GeneralC81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic DataC82 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Macroeconomic DataC87 - Econometric SoftwareC88 - Other Computer SoftwareC89 - OtherC9C9 - Design of ExperimentsC90 - GeneralC91 - Laboratory, Individual BehaviorC92 - Laboratory, Group BehaviorC93 - Field ExperimentsC99 - OtherD-微观经济学(D-Microeconomics)D0D0 - GeneralD00 - GeneralD01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying PrinciplesD02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, and OperationsD1D1 - Household Behavior and Family EconomicsD10 - GeneralD11 - Consumer Economics: TheoryD12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical AnalysisD13 - Household Production and Intrahousehold AllocationD14 - Personal FinanceD18 - Consumer ProtectionD19 - OtherD2D2 - Production and OrganizationsD20 - GeneralD21 - Firm BehaviorD23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights D24 - Production; Capital and Total Factor Productivity; Capacity D29 - OtherD3D3 - DistributionD30 - GeneralD31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their DistributionsD33 - Factor Income DistributionD39 - OtherD4D4 - Market Structure and PricingD40 - GeneralD41 - Perfect CompetitionD42 - MonopolyD43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market ImperfectionD44 - AuctionsD45 - Rationing; LicensingD46 - Value TheoryD49 - OtherD5D5 - General Equilibrium and DisequilibriumD50 - GeneralD51 - Exchange and Production EconomiesD52 - Incomplete MarketsD57 - Input–Output Tables and AnalysisD58 - Computable and Other Applied General Equilibrium Models D59 - OtherD6D6 - Welfare EconomicsD60 - GeneralD61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost–Benefit AnalysisD62 - ExternalitiesD63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and MeasurementD64 - AltruismD69 - OtherD7D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-MakingD70 - GeneralD71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; AssociationsD72 - Economic Models of Political Processes: Rent-Seeking, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting BehaviorD73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; CorruptionD74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; AlliancesD78 - Positive Analysis of Policy-Making and Implementation D79 - OtherD8D8 - Information, Knowledge, and UncertaintyD80 - GeneralD81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty D82 - Asymmetric and Private InformationD83 - Search; Learning; Information and KnowledgeD84 - Expectations; SpeculationsD85 - Network FormationD86 - Economics of Contract LawD89 - OtherD9D9 - Intertemporal Choice and GrowthD90 - GeneralD91 - Intertemporal Consumer Choice; Life Cycle Models and Saving D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice and Growth, Investment, or FinancingD99 - OtherE-宏观经济学和货币经济学(E-Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics)E0E0 - GeneralE00 - GeneralE01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and WealthE1E1 - General Aggregative ModelsE10 - GeneralE11 - Marxian; Sraffian; Institutional; EvolutionaryE12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-KeynesianE13 - NeoclassicalE17 - Forecasting and SimulationE19 - OtherE2E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Employment, and Investment E20 - GeneralE21 - Consumption; SavingE22 - Capital; Investment (including Inventories); CapacityE23 - ProductionE24 - Employment; Unemployment; WagesE25 - Aggregate Factor Income DistributionE26 - Informal Economy; Underground EconomyE27 - Forecasting and SimulationE29 - OtherE3E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and CyclesE30 - GeneralE31 - Price Level; Inflation; DeflationE32 - Business Fluctuations; CyclesE37 - Forecasting and SimulationE39 - OtherE4E4 - Money and Interest RatesE40 - GeneralE41 - Demand for MoneyE42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary SystemE43 - Determination of Interest Rates; Term Structure of Interest RatesE44 - Financial Markets and the MacroeconomyE47 - Forecasting and SimulationE49 - OtherE5E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and CreditE50 - GeneralE51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money MultipliersE52 - Monetary Policy (Targets, Instruments, and Effects)E58 - Central Banks and Their PoliciesE59 - OtherE6E6 -Macroeconomic Policy Formation, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, Macroeconomic Policy, and General Outlook E60 - GeneralE61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy CoordinationE62 - Fiscal Policy; Public Expenditures, Investment, and Finance; TaxationE63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; StabilizationE64 - Incomes Policy; Price PolicyE65 - Studies of Particular Policy EpisodesE66 - General Outlook and ConditionsE69 - OtherF- 国际经济学(F-International Economics)F0F0 - General F00 - GeneralF01 - Global OutlookF02 - International Economic Order; Noneconomic International Organizations ·Economic Integration and Globalization: GeneralF1F1 - TradeF10 - GeneralF11 - Neoclassical Models of TradeF12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale EconomiesF13 - Commercial Policy; Protection; Promotion; Trade Negotiations; International OrganizationsF14 - Country and Industry Studies of TradeF15 - Economic IntegrationF16 - Trade and Labor Market InteractionsF17 - Trade Forecasting and SimulationF18 - Trade and EnvironmentF19 - OtherF2F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business F20 - GeneralF21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital MovementsF22 - International MigrationF23 - Multinational Firms; International BusinessF29 - OtherF3F3 - International FinanceF30 - GeneralF31 - Foreign ExchangeF32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and InstitutionsF34 - International Lending and Debt ProblemsF35 - Foreign AidF36 - Financial Aspects of Economic IntegrationF37 - International Finance Forecasting and SimulationF4F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance F40 - GeneralF41 - Open Economy MacroeconomicsF42 - International Policy Coordination and TransmissionF43 - Economic Growth of Open EconomiesF47 - Forecasting and SimulationF49 - OtherG-金融经济学(G-Financial Economics)G0G0 - GeneralG00 - GeneralG1G1 - General Financial MarketsG10 - GeneralG11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment DecisionsG12 - Asset PricingG13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures PricingG14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event StudiesG15 - International Financial MarketsG18 - Government Policy and RegulationG19 - OtherG2G2 - Financial Institutions and ServicesG20 - GeneralG21 - Banks; Other Depository Institutions; MortgagesG22 - Insurance; Insurance CompaniesG23 - Pension Funds; Other Private Financial InstitutionsG24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; BrokerageG28 - Government Policy and RegulationG29 - OtherG3G3 - Corporate Finance and GovernanceG31 - Capital Budgeting; Investment PolicyG32 - Financing Policy; Capital and Ownership StructureG33 - Bankruptcy; LiquidationG34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance G35 - Payout PolicyG38 - Government Policy and RegulationG39 - OtherH-公共经济学(H-Public Economics)H0H0 - GeneralH00 - GeneralH1H1 - Structure and Scope of GovernmentH10 - GeneralH11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of GovernmentH19 - OtherH2H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and RevenueH20 - GeneralH21 - Efficiency; Optimal TaxationH22 - IncidenceH23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and SubsidiesH24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies H25 - Business Taxes and SubsidiesH26 - Tax EvasionH27 - Other Sources of RevenueH29 - OtherH3H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic AgentsH30 - GeneralH31 - HouseholdH32 - FirmH39 - OtherH4H4 - Publicly Provided GoodsH40 - GeneralH41 - Public GoodsH42 - Publicly Provided Private GoodsH43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount RateH49 - OtherH5H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related PoliciesH50 - GeneralH51 - Government Expenditures and HealthH52 - Government Expenditures and EducationH53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare ProgramsH54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock H55 - Social Security and Public PensionsH56 - National Security and WarH57 - ProcurementH59 - OtherH6H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and DebtH60 - GeneralH61 - Budget; Budget SystemsH62 - Deficit; SurplusH63 - Debt; Debt ManagementH69 - OtherH7H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental RelationsH70 - GeneralH71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and RevenueH72 - State and Local Budget and ExpendituresH73 - Interjurisdictional Differentials and Their EffectsH74 - State and Local BorrowingH77 - Intergovernmental Relations; FederalismH79 - OtherH8H8 - Miscellaneous IssuesH80 - GeneralH81 - Governmental Loans, Loan Guarantees, and CreditsH82 - Governmental PropertyH83 - Public AdministrationH87 - International Fiscal Issues; International Public Goods H89 - OtherI-卫生经济学教育经济学和福利经济学(I-Health, Education and Welfare)I0I0 - GeneralI00 - GeneralI1I1 - HealthI10 - GeneralI11 - Analysis of Health Care MarketsI12 - Health Production: Nutrition, Mortality, Morbidity, Substance Abuse and Addiction, Disability, and Economic Behavior I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public HealthI19 - OtherI2I2 - EducationI20 - GeneralI21 - Analysis of EducationI22 - Educational FinanceI23 - Higher Education Research InstitutionsI28 - Government PolicyI29 - OtherI3I3 - Welfare and PovertyI30 - GeneralI31 - General Welfare; Basic Needs; Living Standards; Quality of Life; HappinessI32 - Measurement and Analysis of PovertyI38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs I39 - OtherJ-劳动经济学和人口经济学(J-Labour and Demographic Economics)J0 - GeneralJ00 - GeneralJ1J1 - Demographic EconomicsJ10 - GeneralJ11 - Demographic Trends and ForecastsJ12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family StructureJ13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth J14 - Economics of the Elderly; Economics of the Handicapped J15 - Economics of Minorities and Races; Non-labor Discrimination J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor DiscriminationJ17 - Value of Life; Foregone IncomeJ18 - Public PolicyJ19 - OtherJ2J2 - Time Allocation, Work Behavior, and Employment Determination and Creation; Human CapitalJ20 - GeneralJ21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and StructureJ22 - Time Allocation and Labor SupplyJ23 - Employment Determination; Job Creation; Demand for Labor; Self-EmploymentJ24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor ProductivityJ26 - Retirement; Retirement PoliciesJ28 - Safety; Accidents; Industrial Health; Job Satisfaction; Related Public PolicyJ29 - OtherJ3J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor CostsJ30 - GeneralJ31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials by Skill, Training, Occupation, etc.J32 - Nonwage Labor Costs and Benefits; Private PensionsJ33 - Compensation Packages; Payment MethodsJ38 - Public PolicyJ39 - OtherJ4 - Particular Labor MarketsJ40 - GeneralJ41 - Contracts: Specific Human Capital, Matching Models, Efficiency Wage Models, and Internal Labor MarketsJ42 - Monopsony; Segmented Labor MarketsJ43 - Agricultural Labor MarketsJ44 - Professional Labor Markets and OccupationsJ45 - Public Sector Labor MarketsJ48 - Public PolicyJ49 - OtherJ5J5 - Labor–Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective BargainingJ50 - GeneralJ51 - Trade Unions: Objectives, Structure, and EffectsJ52 - Dispute Resolution: Strikes, Arbitration, and Mediation; Collective BargainingJ53 - Labor–Management Relations; Industrial JurisprudenceJ54 - Producer Cooperatives; Labor Managed FirmsJ58 - Public PolicyJ59 - OtherJ6J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, and VacanciesJ60 - GeneralJ61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant WorkersJ62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational MobilityJ63 - Turnover; Vacancies; LayoffsJ64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant ClosingsJ68 - Public PolicyJ69 - OtherJ7J7 - Labor DiscriminationJ70 - GeneralJ71 - DiscriminationJ78 - Public PolicyJ79 - OtherJ8 - Labor Standards: National and International J80 - GeneralJ81 - Working ConditionsJ82 - Labor Force CompositionJ83 - Workers' RightsJ88 - Public PolicyJ89 - OtherK-法律和经济学(K-Law and Economics)K0K0 - GeneralK00 - GeneralK1K1 - Basic Areas of LawK10 - GeneralK11 - Property LawK12 - Contract LawK13 - Tort Law and Product LiabilityK14 - Criminal LawK19 - OtherK2K2 - Regulation and Business LawK20 - GeneralK21 - Antitrust LawK22 - Corporation and Securities LawK23 - Regulated Industries and Administrative Law K29 - OtherK3K3 - Other Substantive Areas of LawK30 - GeneralK31 - Labor LawK32 - Environmental, Health, and Safety LawK33 - International LawK34 - Tax LawK35 - Personal Bankruptcy LawK39 - OtherK4K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior K40 - GeneralK41 - Litigation ProcessK42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of LawK49 - OtherL-产业组织(L-Industrial Organization)L0L0 - GeneralL00 - GeneralL1L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance L10 - GeneralL11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of FirmsL12 - Monopoly; Monopolization StrategiesL13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect MarketsL14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; NetworksL15 - Information and Product Quality; Standardization and CompatibilityL16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics; Macroeconomic Industrial Structure; Industrial Price IndicesL19 - OtherL2L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and BehaviorL20 - GeneralL21 - Business Objectives of the FirmL22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure: Markets vs. Hierarchies; Vertical Integration; ConglomeratesL23 - Organization of ProductionL24 - Contracting Out; Joint VenturesL25 - Firm Performance: Size, Age, Profit, and SalesL29 - OtherL3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public EnterpriseL30 - GeneralL31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOsL32 - Public EnterprisesL33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises; Privatization; Contracting OutL39 - OtherL4L4 - Antitrust Issues and PoliciesL40 - GeneralL41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive PracticesL42 - Vertical Restraints; Resale Price Maintenance; Quantity DiscountsL43 - Legal Monopolies and Regulation or DeregulationL44 - Antitrust Policy and Public Enterprise, Nonprofit Institutions, and Professional OrganizationsL49 - OtherL5L5 - Regulation and Industrial PolicyL50 - GeneralL51 - Economics of RegulationL52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning MethodsL53 - Government Promotion of FirmsL59 - OtherL6L6 - Industry Studies: ManufacturingL60 - GeneralL61 - Metals and Metal Products; Cement; Glass; CeramicsL62 - Automobiles; Other Transportation EquipmentL63 - Microelectronics; Computers; Communications Equipment L64 - Other Machinery; Business Equipment; ArmamentsL65 - Chemicals; Rubber; Drugs; BiotechnologyL66 - Food; Beverages; Cosmetics; TobaccoL67 - Other Consumer Nondurables: Clothing, Textiles, Shoes, and LeatherL68 - Appliances; Other Consumer DurablesL69 - OtherL7 - Industry Studies: Primary Products and ConstructionL70 - GeneralL71 - Mining, Extraction, and Refining: Hydrocarbon FuelsL72 - Mining, Extraction, and Refining: Other Nonrenewable ResourcesL73 - Forest Products: Lumber and PaperL74 - ConstructionL78 - Government PolicyL79 - OtherL8L8 - Industry Studies: ServicesL80 - GeneralL81 - Retail and Wholesale Trade; Warehousing; e-CommerceL82 - Entertainment; Media (Performing Arts, Visual Arts, Broadcasting, Publishing, etc.)L83 - Sports; Gambling; Recreation; TourismL84 - Personal, Professional, and Business ServicesL85 - Real Estate ServicesL86 - Information and Internet Services; Computer SoftwareL87 - Postal and Delivery ServicesL88 - Government PolicyL89 - OtherL9L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and UtilitiesL90 - GeneralL91 - Transportation: GeneralL92 - Railroads and Other Surface Transportation: Autos, Buses, Trucks, and Water Carriers; PortsL93 - Air TransportationL94 - Electric UtilitiesL95 - Gas Utilities; Pipelines; Water UtilitiesL96 - TelecommunicationsL97 - Utilities: GeneralL98 - Government PolicyL99 - OtherM-企业管理和商务经济学;市场营销学;会计学(M-Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting)M0M0 - GeneralM00 - GeneralM1M1 - Business AdministrationM10 - GeneralM11 - Production ManagementM12 - Personnel ManagementM13 - EntrepreneurshipM14 - Corporate Culture; Social ResponsibilityM19 - OtherM2M2 - Business EconomicsM20 - GeneralM21 - Business EconomicsM29 - OtherM3M3 - Marketing and AdvertisingM30 - GeneralM31 - MarketingM37 - AdvertisingM39 - OtherM4M4 - Accounting and AuditingM40 - GeneralM41 - AccountingM42 - AuditingM49 - OtherM5M5 - Personnel EconomicsM50 - GeneralM51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions (hiring, firing, turnover, part-time, temporary workers, seniority issues)M52 - Compensation and Compensation Methods and Their Effects (stock options, fringe benefits, incentives, family support programs, seniority issues)M53 - TrainingM54 - Labor Management (team formation, worker empowerment, job design, tasks and authority, job satisfaction)M55 - Labor Contracting Devices: Outsourcing; Franchising; Other M59 - OtherN-经济史(N-Economic History)N0N0 - GeneralN00 - GeneralN01 - Development of the Discipline: Historiographical; Sources and MethodsN1N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Growth and FluctuationsN10 - General, International, or ComparativeN11 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N12 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N13 - Europe: Pre-1913N14 - Europe: 1913–N15 - Asia including Middle EastN16 - Latin America; CaribbeanN17 - Africa; OceaniaN2N2 - Financial Markets and InstitutionsN20 - General, International, or ComparativeN21 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N22 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N23 - Europe: Pre-1913N24 - Europe: 1913–N25 - Asia including Middle EastN26 - Latin America; CaribbeanN27 - Africa; OceaniaN3N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Income, and WealthN30 - General, International, or ComparativeN31 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N32 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N33 - Europe: Pre-1913N34 - Europe: 1913–N35 - Asia including Middle EastN36 - Latin America; CaribbeanN37 - Africa; OceaniaN4N4 - Government, War, Law, and RegulationN40 - General, International, or ComparativeN41 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N42 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N43 - Europe: Pre-1913N44 - Europe: 1913–N45 - Asia including Middle EastN46 - Latin America; CaribbeanN47 - Africa; OceaniaN5N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive IndustriesN50 - General, International, or ComparativeN51 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N52 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N53 - Europe: Pre-1913N54 - Europe: 1913–N55 - Asia including Middle EastN56 - Latin America; CaribbeanN57 - Africa; OceaniaN6N6 - Manufacturing and ConstructionN60 - General, International, or ComparativeN61 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N62 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N63 - Europe: Pre-1913N64 - Europe: 1913–N65 - Asia including Middle EastN66 - Latin America; CaribbeanN67 - Africa; OceaniaN7N7 - Transport, International and Domestic Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other ServicesN70 - General, International, or ComparativeN71 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N72 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N73 - Europe: Pre-1913N74 - Europe: 1913–N75 - Asia including Middle EastN76 - Latin America; CaribbeanN77 - Africa; OceaniaN8N8 - Micro-Business HistoryN80 - General, International, or ComparativeN81 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N82 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N83 - Europe: Pre-1913N84 - Europe: 1913–N85 - Asia including Middle EastN86 - Latin America; CaribbeanN87 - Africa; OceaniaN9N9 - Regional and Urban HistoryN90 - General, International, or ComparativeN91 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913N92 - U.S.; Canada: 1913–N93 - Europe: Pre-1913N94 - Europe: 1913–N95 - Asia including Middle EastN96 - Latin America; CaribbeanN97 - Africa; OceaniaO- 经济发展,技术变迁和增长(O-Economic Development, Technological Change, and Growth)O1O1 - Economic DevelopmentO10 - GeneralO11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic DevelopmentO12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic DevelopmentO13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary ProductsO14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of TechnologyO15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; MigrationO16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital InvestmentO17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements: Legal, Social, Economic, and PoliticalO18 - Regional, Urban, and Rural AnalysesO19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International OrganizationsO2O2 - Development Planning and PolicyO20 - GeneralO21 - Planning Models; Planning PolicyO22 - Project AnalysisO23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in DevelopmentO24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange PolicyO29 - OtherO3O3 - Technological Change; Research and DevelopmentO30 - GeneralO31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and IncentivesO32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&DO33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion ProcessesO34 - Intellectual Property Rights: National and International IssuesO38 - Government PolicyO39 - OtherO4O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate ProductivityO40 - GeneralO41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth ModelsO42 - Monetary Growth ModelsO47 - Measurement of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity O49 - OtherO5O5 - Economywide Country StudiesO50 - GeneralO51 - U.S.; CanadaO52 - EuropeO53 - Asia including Middle EastO54 - Latin America; CaribbeanO55 - AfricaO56 - OceaniaO57 - Comparative Studies of CountriesP-经济体制(P-Economic Systems)P0P0 - GeneralP00 - GeneralP1P1 - Capitalist SystemsP10 - GeneralP11 - Planning, Coordination, and ReformP12 - Capitalist EnterprisesP13 - Cooperative EnterprisesP14 - Property RightsP16 - Political EconomyP17 - Performance and ProspectsP19 - OtherP2P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional EconomiesP20 - GeneralP21 - Planning, Coordination, and ReformP22 - PricesP23 - Factor and Product Markets; Industry Studies; Population P24 - National Income, Product, and Expenditure; Money; Inflation。

六下语文二单元作文写二战战史The Second World War is a significant event in human history. It had a profound impact on the world and changed the course of history. 二战是人类历史上一个重大的事件。

它对世界产生了深远的影响,改变了历史的进程。

From a political perspective, the war was triggered by the expansionist policies of fascist regimes in Germany, Italy, and Japan. The aggressive actions of these countries led to a series of events that ultimately resulted in a global conflict.从政治角度来看,战争是由德国、意大利和日本法西斯政权的扩张政策引发的。

这些国家的侵略行为导致了一系列事件,最终导致了全球性的冲突。

From a military perspective, the war saw the use of new and devastating weapons, such as the atomic bomb. The scale and intensity of the fighting were unprecedented, leading to widespread destruction and loss of life.从军事角度来看,战争见证了新型和毁灭性武器的使用,如原子弹。

战斗的规模和强度前所未有,导致了广泛的破坏和生命的损失。

From a societal perspective, the war brought about significant changes in the roles of women and minorities. Many women joined the workforce in the absence of men, and minority groups made significant contributions to the war effort.从社会角度来看,战争带来了妇女和少数群体角色的显著变化。

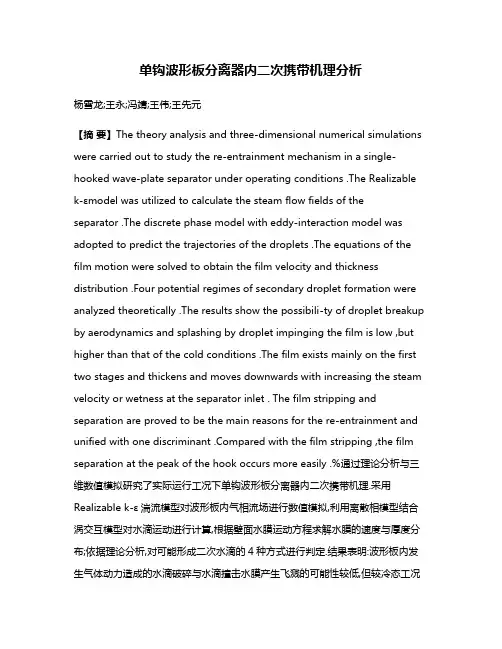

单钩波形板分离器内二次携带机理分析杨雪龙;王永;冯靖;王伟;王先元【摘要】The theory analysis and three-dimensional numerical simulations were carried out to study the re-entrainment mechanism in a single-hooked wave-plate separator under operating conditions .The Realizable k-εmodel was utilized to calculate the steam flow fields of the separator .The discrete phase model with eddy-interaction model was adopted to predict the trajectories of the droplets .The equations of the film motion were solved to obtain the film velocity and thickness distribution .Four potential regimes of secondary droplet formation were analyzed theoretically .The results show the possibili-ty of droplet breakup by aerodynamics and splashing by droplet impinging the film is low ,but higher than that of the cold conditions .The film exists mainly on the first two stages and thickens and moves downwards with increasing the steam velocity or wetness at the separator inlet . The film stripping and separation are proved to be the main reasons for the re-entrainment and unified with one discriminant .Compared with the film stripping ,the film separation at the peak of the hook occurs more easily .%通过理论分析与三维数值模拟研究了实际运行工况下单钩波形板分离器内二次携带机理.采用Realizable k-ε湍流模型对波形板内气相流场进行数值模拟,利用离散相模型结合涡交互模型对水滴运动进行计算,根据壁面水膜运动方程求解水膜的速度与厚度分布;依据理论分析,对可能形成二次水滴的4种方式进行判定.结果表明:波形板内发生气体动力造成的水滴破碎与水滴撞击水膜产生飞溅的可能性较低,但较冷态工况的可能性高;水膜主要集中在波形板的前两级,随入口蒸汽速度或湿度的增加,水膜增厚并向下游移动;将水膜剥落和水膜分离的判别式进行统一,并证实波形板二次携带主要由水膜的剥落和分离造成,且相较水膜剥落,钩峰处的水膜分离更易发生.【期刊名称】《原子能科学技术》【年(卷),期】2016(050)005【总页数】7页(P805-811)【关键词】波形板分离器;二次携带;水滴;水膜分离;水膜剥落【作者】杨雪龙;王永;冯靖;王伟;王先元【作者单位】核动力运行研究所,湖北武汉 430074;中核武汉核电运行技术股份有限公司,湖北武汉 430223;核动力运行研究所,湖北武汉 430074;中核武汉核电运行技术股份有限公司,湖北武汉 430223;核动力运行研究所,湖北武汉 430074;中核武汉核电运行技术股份有限公司,湖北武汉 430223;核动力运行研究所,湖北武汉430074;中核武汉核电运行技术股份有限公司,湖北武汉 430223;核动力运行研究所,湖北武汉 430074;中核武汉核电运行技术股份有限公司,湖北武汉 430223【正文语种】中文【中图分类】TK124波形板分离器能高效地分离出气(汽)流中的水滴,在核电蒸汽发生器内汽水分离[1]和油气分离[2]等工程中起着重要作用。

前后呼应的英语作文800Echoes of the Past: Historical Parallels in the Modern Age.History, as the adage goes, tends to repeat itself, not in the precise manner but in its underlying patterns and dynamics. Throughout the annals of human civilization, we witness the recurring echoes of past events resonating within the complexities of the present. By examining these historical parallels, we gain invaluable insights into the nature of humanity and the cyclical nature of human experience.One striking example of historical echo is the concept of crisis and renewal. From the fall of the Roman Empire to the chaos of the Dark Ages, history is replete with examples of societies collapsing under the weight of their own internal contradictions and external pressures. Yet, amidst the wreckage, seeds of renewal and rebirth often emerge. The Renaissance, for instance, emerged from theashes of medieval Europe, ushering in a period of intellectual and artistic flourishing that transformed Western civilization. Similarly, the post-World War II era witnessed an unprecedented economic and technological boom, laying the foundation for the modern globalized world.Another recurring theme in history is the struggle between liberty and authority. From the Athenian democracy to the American Revolution, societies have fought long and hard to secure their freedoms from the clutches of despotic regimes. However, this struggle is far from over. Even in established democracies, the balance between individual rights and the demands of the state remains a delicate and ever-evolving negotiation. The rise of surveillance technologies and the erosion of privacy laws in recent times are stark reminders that the battle for liberty is an ongoing one.The echoes of the past also manifest in the realm of conflict and war. From the Trojan War to the Cold War, history is a grim testament to the destructive potential of human aggression. Yet, within the horrors of war, thereoften lies the glimmer of hope and reconciliation. The stories of soldiers forging friendships across enemy lines, the acts of mercy and kindness displayed amidst the carnage, attest to the indomitable spirit of humanity. Moreover, war has often served as a catalyst for social change, leadingto the abolition of slavery, the expansion of civil rights, and the formation of international organizations dedicatedto peace and cooperation.Furthermore, history reminds us of the profound impactof technology on human society. From the invention of the printing press to the rise of the internet, technological advancements have reshaped our lives in countless ways. However, the echoes of the past also caution us about the potential dangers and pitfalls associated withtechnological progress. Concerns about job displacement, privacy violations, and the erosion of human connection in the digital age are all echoes of similar fears that accompanied earlier technological revolutions.The study of history, therefore, provides us with a valuable lens through which to examine the challenges andopportunities facing our world today. By understanding the patterns and echoes of the past, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the complexities of human nature and the cyclical nature of human experience. It allows us toidentify the pitfalls to avoid, the mistakes not to repeat, and the lessons that can guide us towards a brighter future.In an interconnected and rapidly changing world, it is more important than ever to draw upon the wisdom of the past. By listening to the echoes of history, we can make more informed decisions, navigate the challenges of the present, and work towards creating a better and more equitable future for all.。

外文翻译原文An Overview of Express Delivery ServicesMaterial Source: A Report By US-ASEAN Business Council,2005Author: James I. Campbell Jr.A. Characteristics of an Express Delivery CompanyFour major integrators – UPS, FedEx, TNT, and DHL – account for almost 85 percent of the world’s express shipments. The services that these companies provide generally share the following characteristics which differentiate them from other traditional forms of delivery services:- Door-to-door delivery: This includes the seamless transfer across multiple modes of transport. The “integrated” aspect of the service offered frees the customer from the need to make complex transportation arrangements for pick-up and delivery.- Close custodial control: Using sophisticated information systems that enhance security, EDS firms maintain close custodial and administrative control over all shipments. This is particularly important to reduce the risk of loss or damage to goods in transit.- Track and trace technology: Shippers and consignees may track the precise movement and location of their shipments and confirm delivery with the use of sophisticated ‘track and trace’ technology that an EDS firm provides.- Facilitation of customs clearance: EDS firms assist with customs clearance so that customers do not have to navigate bureaucratic customs regimes and the required paperwork.- High level of reliability: EDS firms promise that packages will arrive at the required destination, on time. This is particularly important for shipments of high-tech components due for production lines, as well as essential financial documents.- Global service: The major EDS firms offer their customers delivery to markets and cities worldwide through an intricate network of air hubs and stations. EDS is a network business.- Speed of delivery: Most importantly, Overnight and Second-day expressservices reduce overall inventory and warehousing needs, and maximize supply chain efficiency. The average shipping time from the U.S. to Southeast Asia is about 2-3 working days door-to door. Together, these characteristics bring businesses timely, secure, and guaranteed worldwide delivery of documents, products, components, and spare parts to assist with efficient supply chain management.B. Benefits to BusinessesAir cargo represents 40 percent of the value of global trade. The bulk of this is handled by EDS firms. Servicing the needs of both multinational corporations and the emergent small and medium enterprise (SME) sector in their manufacturing, import, and export activities, this industry has been an important engine for economic growth. Sectors which heavily rely on EDS to remain competitive are knowledge-based and technologically advanced, including that of pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, information technology and telecoms, textiles, automotive & transport, engineering, financial and business services, and traditional manufacturing.To remain competitive, companies today focus not only on product performance but also factor in how well costs can be managed and reduced through distribution and production, and how quickly parts can be brought together, assembled, and distributed to global markets. EDS firms help with the smooth orchestration of these activities and are therefore part of the critical infrastructure for efficient supply chain management.Reducing Inventory and Other Indirect CostsWith the support of EDS, companies no longer have to maintain large inventories and can therefore carry out better concentration, rationalization, and location of warehouses. In a study conducted by Gausch and Kogan (2001), companies in developing countries were found to have 2 - 5 times more inventory holdings in the manufacturing sector than companies in the U.S.Halving these inventories could consequently reduce unit production costs by 20 percent. In a typical Asian emerging market, logistics supply chain costs is as high as 22 - 24 percent of total production costs for manufacturers. In another study, it was found that for every $1 spent on express transportation, companies would save $1.50 in warehousing and inventory cost. For manufacturers, taking advantage of the availability of EDS allows for more efficient stock management and production techniques to be practiced, including the ability to respond more quicklyto stock outages, and production interruptions. These indirect costs are not always visible and often overlooked but are critical to SMEs in emerging economies. Other immediate cost savings can also be realized through greater flexibility in sourcing. The flexibility allows companies to source from a wider array of suppliers and reduce their input costs.Introducing Flexibility into Business StructureEDS allows for more flexible business solutions. Relying on EDS to bridge distances removes the traditionally important time-to-market consideration and allows companies to make strategic decisions on where to locate their business units based on factors of competition, proximity to supporting industries, and complementary industry hubs.This is particularly relevant for knowledge-based industries in the biomedical and pharmaceutical field. In a survey conducted of European companies in Germany on the usage of EDS, 80 percent of survey respondents reported the importance of being based in locations providing “maximum participation in leading research associations.” Decentralization of research & development units to hubs where these laboratories, testing centers, hospitals, patent registration offices, and research think tanks are located allows businesses to benefit from an environment of innovation important to product development. At the same time, product development units rely on EDS to ship samples to markets for clinical trials, deliver highly classified and proprietary legal documents and patent applications, ship urgently needed drugs to hospitals, and maintain “just-in-time” stock-management practices for its laboratories.C. Economic BenefitsIn many parts of the world, the EDS sector has been a catalyst to trade and investment growth, generating profound multiplier effects for the wider economy. For ASEAN countries looking to extend their reach to global markets, networks that EDS firms build are critical. These networks render supply chains more efficient and contribute greatly to export growth, stimulate foreign direct investment, and foster regional development and SME growth.Facilitating Export GrowthIn ASEAN, intra-regional trade accounts for about 20 percent of overall trade. This is considerably less than in most regions. The main reasons for the limited intra-regional trade are the “pattern of logistics costs and institutional barriers toland-based trade.”This phenomenon makes countries of the region effectively closer to industrial countries than to each other. To fully realize the benefits the ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (AFTA), bringing lagging economies and landlocked countries in the region up to median performance levels is key.There is a causal link between connectivity and overall growth in trade, and an even stronger correlation between transportation and logistics infrastructure and export performance.Transportation and logistics-related costs in ASEAN continue to represent a substantial percentage of the actual cost of goods. A country with high logistics costs is far, in an economic sense, from international markets. In the study “Towards a Geography of Trade Costs” (Hummel 1999) which compared sales by manufacturers of similar products, exporters with 1 percent lower shipping costs enjoy a 5 - 8 percent higher market share. In another study conducted by the McKinsey Group, annual GDP for one Asian country is forecasted to increase by 1.5 to 2 percent by 2010 if logistics costs are reduced by 15 to 20 percent (This is in contrast to an ongoing $10 billion infrastructure project which would only generate 0.7 to 1 percent GDP growth over the same period). Indeed, injecting competition into the industry to lower logistics costs can give a significant competitive edge to producers in an open economy. Efficient inter-modal transportation, including the use of EDS, would result in more efficient supply chain management.These efficiencies undoubtedly replicate gains in the export sector. A study conducted by the Economic Strategy Institute concluded that further development and liberalization in the air express industry could result in percentage gains for exports per year from 2004 - 2008 between 0.386 - 0.562 percent per year for Singapore; 2.895 – 4.215 percent per year for Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines; and 3.86 – 5.62 percent per year for Vietnam and Indonesia.Facilitating FDI and Promoting Regional DevelopmentEDS firms play a critical role in influencing company decisions on how much and where to invest.This is especially applicable to remote markets where EDS firms assist in overcoming problems of geography and weaker transportation infrastructure. Fifty-eight percent of participating companies in a survey conducted for the report “The Economic Impact of Express Carriers in Europe” (Oxford Economic Forecasting, 2004) consider easy access to markets, customers or clients, as “absolutely essential” when deciding where to locate. In the EU, the importance ofEDS is compelling – without EDS, 35 percent of those interviewed for a study in Portugal said they would have to relocate; 15 percent of the UK and 10 percent of the Italian companies surveyed would consider relocating abroad; and 30 percent of the French companies and 10 percent of the Belgian firms surveyed would consider outsourcing.The EDS industry now supports 530,000 direct and indirect jobs in the EU. Their presence has injected the much needed downstream investment for creating jobs in the 10 new EU member states. 12,000 employees work directly for the four main integrators in new EU countries, and countless more are employed in automotive manufacturing, warehousing, IT support, and service centers.The EDS industry is a dynamic instigator of regional development in two ways. First, it allows for businesses to be located in regions that are not close to their markets. Second, the clustering effect (businesses wanting to be near hubs to take advantage of the latest pick-up time possible) that major express hubs create stimulates regional development. For example, it is estimated that further liberalization of the industry in China will do much to assist with the regional development of its western provinces. Already, it is expected that growth in the industry will generate $84 billion in increased manufacturing output, and 800,000 jobs for China’s export industry over five years.Similar benefits can be expected in ASEAN. The experiences of FedEx and UPS in the Philippines provide an excellent example. FedEx has been located in Subic Bay since 1995, and UPS has had its intra-Asia hub in Pampanga Clark since 2002. Both hubs, with dynamic networks to all parts of Southeast Asia, have been successful in bringing about the clustering of industry, and stimulating development for regions in the Philippines vacated by the U.S. military.译文快递服务业概述资料来源: 美国——东盟商业协会2005年度报告作者:詹姆士·堪培尔1快递公司的特征四大巨头——UPS,FedEx,TNT和DHL几乎包揽了世界上85%的快递货物。

Published:August30,2011r2011AmericanChemicalSociety15312dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja206525x|J.Am.Chem.Soc.2011,133,15312–15315

COMMUNICATIONpubs.acs.org/JACS

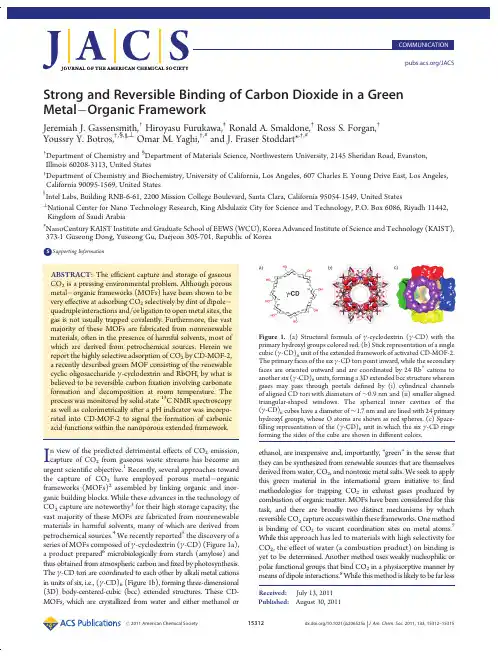

StrongandReversibleBindingofCarbonDioxideinaGreenMetalÀOrganicFramework

JeremiahJ.Gassensmith,†HiroyasuFurukawa,‡RonaldA.Smaldone,†RossS.Forgan,†YoussryY.Botros,†,§,||,^OmarM.Yaghi,‡,#andJ.FraserStoddart*,†,#

†DepartmentofChemistryand§DepartmentofMaterialsScience,NorthwesternUniversity,2145SheridanRoad,Evanston,

Illinois60208-3113,UnitedStates‡DepartmentofChemistryandBiochemistry,UniversityofCalifornia,LosAngeles,607CharlesE.YoungDriveEast,LosAngeles,

California90095-1569,UnitedStates)IntelLabs,BuildingRNB-6-61,2200MissionCollegeBoulevard,SantaClara,California95054-1549,UnitedStates

^NationalCenterforNanoTechnologyResearch,KingAbdulazizCityforScienceandTechnology,P.O.Box6086,Riyadh11442,

关于媒体的英语作文Title: The Impact of Media on Society。

In today's interconnected world, media plays a pivotal role in shaping our perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors. From traditional newspapers to digital platforms, media channels have become integral parts of our daily lives, influencing how we think, interact, and make decisions. This essay explores the multifaceted impact of media on society.First and foremost, media serves as a crucial source of information. Through newspapers, television, radio, and online news portals, people access news from around the globe instantly. This rapid dissemination of information facilitates awareness and understanding of current events, societal issues, and global developments. However, the credibility and accuracy of media content are paramount. With the proliferation of fake news and biased reporting, discerning audiences must critically evaluate sources todistinguish fact from fiction.Furthermore, media shapes public opinion and influences societal norms. Through news coverage, documentaries, and social media discussions, media platforms contribute to the formation of collective attitudes and values. For instance, the portrayal of certain groups or individuals in the media can either perpetuate stereotypes or challenge existing biases. Likewise, the representation of social issues such as gender equality, environmental conservation, and racial justice can spark public discourse and advocacy for change.Moreover, media has a significant impact on consumer behavior and popular culture. Advertising, product placements, and celebrity endorsements shape consumer preferences and purchasing decisions. By strategically promoting certain products or lifestyles, media channels contribute to consumerism and materialism in society. Additionally, the entertainment industry influencescultural trends, fashion, and social norms through movies, television shows, and viral content. As a result, media plays a pivotal role in shaping the cultural landscape andcollective identity of communities.However, alongside its benefits, media also poses challenges and risks to society. One notable concern is the potential for misinformation and propaganda to spread rapidly through digital platforms. With the rise of social media algorithms and echo chambers, individuals may be exposed to biased or misleading information that reinforces their existing beliefs and polarizes society. Moreover, the digital age has ushered in new forms of media addiction and mental health issues, as people become increasingly reliant on technology for entertainment and communication.Furthermore, media censorship and control by governments or corporations can limit freedom of expression and hinder democracy. In authoritarian regimes, media censorship is used as a tool to suppress dissent and manipulate public opinion. Even in democratic societies, media consolidation and corporate influence raise concerns about journalistic integrity and independence. Thus, ensuring media plurality and safeguarding press freedom are essential for a healthy democratic society.In conclusion, media plays a multifaceted role in shaping society, influencing everything from information dissemination to cultural norms and consumer behavior. While media has the power to inform, educate, and empower individuals, it also poses challenges such as misinformation, propaganda, and censorship. Therefore, promoting media literacy, ethical journalism, and regulatory frameworks are essential for harnessing the positive potential of media while mitigating its negative impact on society.。

横断位t2 英语The Transverse Tectonic Zone: A Geologic EnigmaThe Earth's surface is a dynamic canvas, sculpted by the relentless forces of plate tectonics. Amidst the grand tapestry of mountain ranges, deep ocean trenches, and volcanic islands, one particular feature stands out as a geologic enigma – the transverse tectonic zone. This enigmatic structure, known as the Transverse Tectonic Zone or simply the Transverse Zone, has captivated the attention of geologists and geophysicists alike, as it challenges our understanding of the fundamental processes that shape our planet.The Transverse Zone is a complex network of faults, fractures, and lineaments that cut across the traditional boundaries of tectonic plates. Unlike the well-understood convergent and divergent plate boundaries, where plates collide or drift apart, the Transverse Zone defies the conventional model of plate tectonics. It represents a zone of oblique or transverse motion, where the movement of tectonic plates is neither purely parallel nor perpendicular to the plate boundary.This unique configuration has profound implications for the Earth'sgeology and geodynamics. The Transverse Zone is often associated with a range of tectonic and seismic phenomena, including the formation of complex fault systems, the development of unique geological structures, and the occurrence of devastating earthquakes.One of the most remarkable aspects of the Transverse Zone is its global distribution. While the specific manifestations of the Transverse Zone may vary from region to region, it is a feature that has been observed on multiple continents and in various tectonic settings. From the western United States, where the Transverse Ranges of California disrupt the otherwise relatively simple trend of the Pacific-North American plate boundary, to the Sumatran Fault Zone in Indonesia, where the Transverse Zone intersects the Sunda Trench, the Transverse Zone has left its mark on the Earth's surface.The scientific community has long grappled with the origins and evolution of the Transverse Zone. Numerous theories have been proposed to explain its formation and the processes that sustain its existence. Some researchers suggest that the Transverse Zone may be a remnant of ancient plate boundary configurations, while others believe that it is the result of the interaction between multiple tectonic forces acting on the Earth's crust.One intriguing hypothesis posits that the Transverse Zone may be a manifestation of the Earth's deep-seated mantle dynamics. Themantle, the thick layer of semi-molten rock that lies beneath the Earth's crust, is believed to play a crucial role in shaping the surface features of our planet. The Transverse Zone, with its complex network of faults and lineaments, may be a surface expression of deep-seated mantle convection patterns or the interaction between different mantle flow regimes.Another line of investigation suggests that the Transverse Zone may be linked to the Earth's magnetic field and the way it interacts with the planet's internal structure. The Transverse Zone is often associated with regions of anomalous magnetic field patterns, leading some scientists to hypothesize that there may be a connection between the Transverse Zone and the Earth's core-mantle boundary, where the planet's magnetic field is generated.Regardless of the specific mechanisms behind its formation, the Transverse Zone remains a captivating subject of scientific inquiry. Its study has led to advancements in our understanding of plate tectonics, seismology, and the complex interactions between the Earth's interior and its surface features.As geologists and geophysicists continue to explore the Transverse Zone, new discoveries and insights are likely to emerge. The quest to unravel the mysteries of this enigmatic feature may not only deepen our knowledge of the Earth's geological history but also providevaluable clues about the dynamic processes that shape our planet's future.In the end, the Transverse Tectonic Zone stands as a testament to the enduring mysteries of our Earth. It serves as a reminder that even in an age of advanced scientific understanding, there are still profound questions waiting to be answered, and that the pursuit of knowledge is an endless journey of exploration and discovery.。

1.万物并育而不相害,道并行而不挬。

All things exist together but never harm each other; all ways function together but never go against each other.2.刀子嘴豆腐心。

Her bark was worse than her bite.一个唱红脸一个唱白脸。

One coaxes while the other coerce.3.The Nobel prize for literature in 2012 is awarded to Chinese writer Mo Y an” who withhallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and contemporary.诺贝尔委员会的演讲词:莫言将魔幻现实主义与民间故事,历史与当代社融合在一起。

4. The joy of true joys is the joy that joys in the joy of others.独乐乐,众乐乐,孰乐?5.Summer merges into autumn.夏去秋来。

6. She was sentimental over a leaf that has been blown into her room.见一叶飘零,随风入室,边愁绪满怀,难以自解。

11.She has beauty still, and if it be not in its heyday, it is not yet in its autumn.她美丽依旧,若非风华正茂,也未到迟暮之年。

7.也可以去桂林,沿着漓江顺水而下到阳朔,“桂林上水甲天下,阳朔山水甲桂林”这个旅游项目不会使你失望。

Alternatively, you may proceed to Guilin .Where you can sail down the Lijiang River to Y angshuo. As an old saying goes” The landscape of Guilin ranks first in Guilin.” Thistourist program will not disappoint anyone.8.在整个改革开放过程中都要反对腐败。

关于电竞发言稿英文Ladies and gentlemen, distinguished guests, fellow gamers, and esteemed members of the gaming community,I stand here today in front of you to discuss one of the most exciting and rapidly growing industries of our time - esports. With its exponential popularity and economic significance, it is crucial that we recognize and appreciate the impact that esports is having on our lives, our society, and our economy.First and foremost, let us address the question of what exactly esports is. Esports, short for electronic sports, refers to competitive video gaming. It involves organized, multiplayer video game competitions between professional players or teams. These competitions can take place in various formats, from individual skirmishes to team-based battles. And just like traditional sports, esports has its own set of rules, regulations, and referees.The rise of esports can be attributed to the convergence of technology, accessibility, and the innate human desire for competition. With the advent of high-speed internet connectivity, gamers from across the globe can now connect and compete in real-time. The accessibility of gaming platforms, such as PCs, consoles, and mobile devices, has further contributed to the growth of esports. This convergence has opened up a whole new world of opportunities for both players and spectators.Esports has already had a profound impact on our society and culture. For one, it has brought gaming out of the confines of bedrooms and basements and into the mainstream. It haschallenged the stigmatization of gamers as antisocial or lazy, showcasing the dedication, skill, and teamwork required to succeed in the world of esports. Professional gamers are now regarded as athletes, admired for their talent and commitment.Furthermore, esports has fostered a sense of community and camaraderie among gamers. Online gaming platforms and social media have provided a virtual space for gamers to connect, communicate, and collaborate. This has led to the formation of esports teams and fan bases, creating a sense of belonging and shared purpose.Not only has esports impacted our society, but it has also had a significant economic impact. The esports industry is projected to reach a market value of over $1.5 billion by 2023. This growth is fueled by various revenue streams, including sponsorships, advertising, merchandise sales, ticket sales for live events, and media rights. Major brands have recognized the value of esports and have invested heavily in partnerships and sponsorships. This not only provides financial support to players and teams but also promotes the growth and recognition of the industry.In addition to the economic impact, esports has also created numerous job opportunities. Beyond the players, there is a need for coaches, managers, commentators, analysts, event organizers, and many other roles. This industry has provided employment opportunities for passionate individuals who have a deep understanding and love for gaming.However, there are still challenges that need to be addressed forthe sustainable growth of esports. One such challenge is ensuring the well-being and mental health of players. The intense competition, rigorous training regimes, and long hours of gameplay can take a toll on individuals. Establishing supportive structures and resources, such as mental health counseling, is essential to ensure the welfare of players.Another challenge lies in combating cheating and ensuring fair competition. Cheating and match-fixing are issues that need to be tackled head-on to maintain the integrity and credibility of esports. Implementing strict regulations, employing dedicated anti-cheat software, and educating players about the consequences of cheating are crucial steps to ensure a level playing field.Lastly, inclusivity and diversity deserve attention within the esports industry. The gaming community should strive to create an environment that is inclusive of all genders, races, and backgrounds. Efforts must be made to provide equal opportunities and representation for underrepresented groups. With a diverse and inclusive industry, we can truly unlock the full potential of esports. In conclusion, esports has emerged as a force to be reckoned with. Its impact on society, culture, and the economy cannot be denied. It has shattered stereotypes, fostered community, and created opportunities like never before. However, we must also recognize the challenges that lie ahead and work together to overcome them. By doing so, we can ensure that esports continues to thrive and evolve, captivating audiences and shaping the future of gaming.Thank you for your attention, and here's to the bright future of esports!。

5352012,24(4):535-540DOI: 10.1016/S1001-6058(11)60275-8NUMERICAL STUDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN APPARENT SLIP LENGTH AND CONTACT ANGLE BY LATTICE BOLTZMANN METHOD*ZHANG Ren-liang, DI Qin-feng, WANG Xin-liang, DING Wei-peng, GONG WeiShanghai Institute of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics and Shanghai Key Laboratory of Mechanics in Energy Engineering, Shanghai University, Shanghai 200072, China, E-mail: zhrleo@(Received December 9, 2011, Revised March 1, 2012)Abstract: The apparent slip between solid wall and liquid is studied by using the Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) and the Shan-Chen multiphase model in this paper. With a no-slip bounce-back scheme applied to the interface, flow regimes under different wall wettabilities are investigated. Because of the wall wettability, liquid apparent slip is observed. Slip lengths for different wall wettabilities are found to collapse nearly onto a single curve as a function of the static contact angle, and thereby a relationship between apparent slip length and contact angle is suggested. Our results also show that the wall wettability leads to the formation of a low-density layer between solid wall and liquid, which produced apparent slip in the micro-scale.Key words: Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM), wettability, apparent slip, contact angle, nano-particles adsorbing methodIntroductionThe no-slip boundary condition, which states that the fluid velocity at a fluid-solid interface equals that of the solid surface has been proven valid at macro- scopic scales, but is not fulfilled at microscopic scales[1]. A series of experiments[2,3] and numerical results[4,5] have found fluid slip at the boundaries of the flow channels in microfluidics. As the typical length scale of the micro-fluid flows gets smaller, the effect of boundary slip becomes more prominent, and has been paid more attention in engineering applica- tions[6]. Based on this slip boundary effect, artificial super-hydrophobic surfaces have been widely used in industrial production and daily life. For example, self- *Project supported by the National Natural Science Foun- dation of China (Grant No. 50874071), the National High Technology Research and Development of China (863 Program, Grant No. 2008AA06Z201), the Key Program of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (Grant No. 071605102) and the Leading Talent Funding of Shanghai. Biography: ZHANG Ren-liang (1982-), Male,Ph. D. CandidateCorresponding author: DI Qin-feng,E-mail: qinfengd@ cleaning paints, roof tiles, fabrics and glass windows that can be cleaned by a simple rainfall and the nano- particles adsorbing method[2] in improving oil reco- very are all in practice.Slip length is of great importance in calculation of drag and other hydrodynamic properties of fluid flowing through micro-channels or over nano-scale patterned surfaces, but it is very difficult to directly measure the apparent slip length accurately in experi- ments. In 1823, Navier proposed a slip boundary con- dition that the fluid velocity at a point on a surface is proportional to the shear rate at the same point, but the value of slip length is hard to be determined. Chen et al.[7] investigated the Couette flows by means of a two-phase mesoscopic Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM), and the results showed that there is a strong relationship between the magnitude of slip length and the solid-fluid interaction, but it is a very difficult or even impossible task to compute the exact slip length in dependence of interaction and it is also difficult to be applied to engineering.In this work, we focus on investigating the effe- cts of wall wettabilities on the slip length in order to get a slip length model governed by contact angle. Using this model, it is easy to estimate the slip length because the contact angle is a parameter that can be536 easily measured.1. Numerical modelTo simulate non-ideal multiphase fluid flows, the attractive or repulsive interaction among molecules, which is referred to as the non-ideal interaction, should be included in the LBM. There are many app- roaches to incorporate non-ideal interactions, such as the color-fluid model, interparticle-potential model, free-energy model, mean-field theory model and so on. The interparticle-potential model proposed by Shan and Chen [8,9] is to mimic microscopic interaction forces between the fluid components. This model modified the collision operator by using an equili- brium velocity that includes an interactive force. This force guarantees phase separation and introduces sur- face-tension effects. This model has been applied with considerable success in measuring contact angles [10] and examining the effect of wall wettabilities, topo- graphy and micro-structure on drag reduction of fluid flow through micro-channels [11]. As an extension of the Shan-Chen model, Benzi et al.[12] first derived an analytical expression for the contact angle and the sur- face energy between any two of the liquid, solid and vapor phases.The LBM, which involves a single relaxation time in the Bhatnagar-Gross-Krook (BGK) collision operator, is used here. The time evolution of this model can be written as+,+,i i i =f t t t f t '' x c x1(,)(,)eq i i f t f t W ª ¬x x º¼(1) herew (,)i f t x r fluid p i is the single-particle distribution fun-ction fo articles moving in the direction i c at (,)t x , (,)eq f t x the equilibrium distribution un- ' e step of simulation, and parameter f ction, t the tim W the relaxation time characterizing the collision pro- sses by which the distribution functions relax to- wards their equilibrium distributions.In the two-dimensional (2-D) squ ce are lattice with nine velocities model [13], the equilibrium distribution function, (,)eq i f t x , d pends only on local density and veloci n be chosen as the following forme ty and ca 224()=1++22i i eqii s s f c c c Z U ªº«» «»¬¼c u c u u u 2s (2)rewhe=0,0i c c (= 0)i 1)1)=cos ,sin 22i i i c S S ªº«»¬¼c (3b) (=1,...,4)i2-92-9=cos ,sin 44i i i c S S º»¼c(=5,...,8)i (3c)4=9i Z (=0)i(4a)1=9i Z (=1,2,3,4)i (4b)1=36i Z (=5,6,7,8)i (4c)221=3s c c (5)t =/c x '' is the lattice velocity, x ' the lattice dis- tance, and t ' the time step of simulation, and U the fluid density, which can be ned from obtai =Uiif¦.The macroscopic velocity u is given by=++i i ads if U W ¦u c F F (6)Eq In .(6), F and ads F are th d-fluid interact e flui ionforce and fluid-solid inter y. The fluid-fluid interaction is obtained by using an ctive short-range force [8]action force, respectivel attra()=(,)+,i i i iG t t t \ 'w \¦F x x x c c (7)where G is the interaction strength, which is used to ontrol the two-phase liqui in c d teraction, and is nega- tive for icle attraction, part \ is the in ntial, which is defined as [14]teraction pote-/0(,)e t =UU\\ x (8)0\ and 0U are constants As in Ref.[14] i w istaken as 1/9 for =1,2,4i , (3a). as 0 fo It is simple to and a wall by introducing an extra force, and thise as T to induce hase separatio in this pape ond equation is [14],3i w 1/36 for i =5,6,7,8, and r =0i .describe the interaction between a luid f m thod w first used by Martys and Chen [15].he idea is to create an analogue to the particle-particle in- teraction force used p n, and r the corresp ing537()=(,)(+,)ads ads i i i iG t w s t t \ '¦x x x c c (9)Here =0,1s for the fluid and the solid phase, respe- ctively, and the adhesion parameter ads G is used to control the wettability behavior of the li u F q surfaces. I t can be seen that Eq.(9) incor dhesive interaction between fluid and surfaces.nd the as id at solid porates an a A relaxation time tunes the kinematic vis- cosity21=2s v c t W §· '¨¸©¹ (10)The equation of state in the Shan-Chen model s [14] i>@2,)=+(36G P t U \x (11)where P isthe pressure.ig erent value.in a 2-D o simula- on-sl sche s employed for the solid-fluid interfaces, nd periodic boundary conditions were applied at both let and outlet ends along the horizontal direction. A he middle betwFig.1 Static contact angleF .2 Contact angles as a function of absG for diff of GNumerical simulation of contact angleThe LBM simulations were carried out main. The grid mesh used is 50×200. In the2d tion, as in Ref.[11], the general n ip bounce-back me [16] wa a in droplet with the diameter of 30, is set at t een two ends. After 30 000 time steps, the result tends to be stabilized. Figure 1 shows an example ofstatic contact angle, which is 127.6o when =120G , =130abs G and 200/(,)=4e x t U \ in Eqs.(7) and (9). The values of parameters G and abs G and the simulated contact angles for each case are listed in Fig.2.As is shown in Fig.2, abs G and G determine the value of contact angle. abs G represen - action d solid surface andG the strength of interaction tweenparticles. A negative abs G indicates attractive interaction. When ts fluid e ma the stre gnitude of ngth of inter G between fluid an be ven, the greater th is gi abs G , the stronger the reac , thus resulting in smaller contact angle. The act angle is a static parameter of measuring the wettability of a liquid on a lid surface, and it can be easily measured. I n our simulation, we also change the parameter abs G to simulat rbitrary contact angle, and then easily obtain ent wall wettabilities. Form Fig.2, we also see that both parameters of abs G and G have signifi- cant impact on the simulated contact angle.tion cont n ed in Figs.3 and 4 (g so diff ca e a er ig.3 V ig.4 . Nu wettabi- ti mu- ti ensity Poiseuilleows are displayF elocity profiles with different contact anglesF Density profiles with different contact anglesmerical simulation of slip lengthIn order to investigate the effects of wall es on the slip length, we conducted numerical si ons for the 2-D Poiseuille flows. Typical d3li la and velocity profiles of the pressure-driven fl iven G =120 ).538 The ordinate in both figures represents the distanceto the other. The from one of the solid surface boundary abscissa in Fig.3 is the normalized velocity, where 0v is the max velocity measured at the center in the channel for the case of no slip. The abscissa in Fig.4 is the normalized fluid density, where 0U is the liquid density for the case of no slip. The pressure gra- dient is specified as 5×10–3 in lattice unit for both cases. Different contact angles (as shown in both Figs.3 and 4) can be simulated by specifying different values of the adhesion parameter (abs G ). All simula- tions were run until static equilibrium was nearly attained, and then a pressure gradient of 5×–3 was applied in the x -direction (flow direction).10ary d at y i e bo ig.5 V A pproa-hes ) or nt with e bo the o bo daries. However, the flu locit ncrea- th undary. he l the b plotted in Fig.3 e obtained from LBM i the contact the intera-t ter ). s, mb of reseF elocity profiles of simulated and fitteds is shown in Fig.3, the fluid velocity a zero as 24.5y o (the lower bound (the upper boundary), which is consiste unce-back boundary condition specifiec y o th tw un id ve ses dramatically in a very thin layer near T ayer is so thin that it is hard to see its details nearoundary, and velocity at the boundary looks likenon-zero when a larger scale, as shown in . I n a macro-scale, velocity at a boundary is nearly zero, but in a micro-scale, the velocity appears non-zero (so called apparent slip). Plots shown in Fig.3 clearly indicate that the slip velocity at the boun- dary increases as contact angle increases. I n order to understand the physical mechanism of such kind ofphenomenon, the density profiles of fluid with diffe-rent contact angles is drawn in Fig.4. One should notethat the density of the fluid with zero contact angle isconstant (as shown by the circle symbol vertical linein Fig.4). However, a sharp reduction of fluid densitynear the boundary is observed for a fluid with non-zero contact angle, which clearly indicates a layer ofmuch less dense fluid (most probably gas) is inducedbetween the dense liquid and solid surface. Fitting forthe velocity data points where the density is approxi- mately constant, we can get a parabolic of velocity profiles, and extrapolating the fitted profiles to zerovelocity yields a slip length as shown in Fig.5. Given an interaction strength (G ), different slip lengths can be obtained by using a series values of the adhesion parameter (abs G ), as shown in Fig.6. As was discussed above, the parameter of abs G controls the interactionbetween the fluid and solid surface. I ncreasing abs G decreases the attraction (or increases the repulsion) between the liquid and solid surface, and thus attracts more gas to the surface. The less dense of the fluid at the surface, less viscous shear force, and the more significant slippage appeaFrom Figs.3 and 4 one can see that the wetting properties of the wall have an important influenc the velocity profile, especially the slip velocity at the boundary. There is a low-density layer between the bulk liquid and the wall, and the more hydrophobic the wall is, the lower density of fluid is (see Fig.4). This result is similar to thos the rs. e onother simulation [17] and observed in MDS [18]. Compa- red with the macroscopic flow, the ratio of the low- density layer region to the inner region is larger in the microscopic flow, and this is the main difference between micro-flow and macro-flow. Thus, the slip cannot be ignored in the micro-flow.F g.6 Slip length as a function of absG for different From Figs.2 and 6, we can see that ngle and slip length are associated with ion strength (G ) and adhesion parame umerical results of contact angles and slip lengt G a c (abs G h Fig.7,N represented by different sy ols shown in orrespond to different values G , respectively, re-c p nted by squares (=120G ), circle (=125G ),delta (=130G ) and gradient (=135G ). The numerical results shown in Fig.7 cover a wide range of contact angles, ranging from 18o to 150o . Results shown in Fig.7 clearly indicate that slip length is a function of contact angle. The relationship between slip length and contact angle can b easily obtained by fitting those numerical Eq.(12)) a y the solid Fig.7.e data (see s shown b curve in539/56.06=0.1441e 1L T G (12)where T is contact angle and L G is slip length.i on i o a gle h ed above, the slip length is the result of interaction ace, and it depe- ds on the properties of the liquid (e.g., ) and the lu n fluid articles (controlled by a parameter of ) and the in- raction between a fluid and a soli ontrolled by al ng, SHEN Chen and WANG Zhang-hong et al.Experimental research on drag reduction of flow in micro-channels of rocks using nano-particle adsorption . Acta Petrolei Sinica, 2009, 30(1): 125- ese).[4] [5] AT T. and WANG Y. Slip effects on[6] 2008, 25(1): [8] [9] [10] ., THORNE D. T. Jr and SCHAAP M. G. et07, 76(6): on drag reduction effect in micro-channel flow [12] of boundaries: The contact angle[J]. Physical [14] [15] lation of multicompo-F g.7 The slip length against contact angleForm Fig.7 we can see that the slip lengths fferent surfaces are found to collapse nearly ont ngle curve as a function of the static contact an aracterizing the surface wettability. As was discu-d si c ss between the liquid and the wall surf n G wall surface (e.g., abs G ). So the simulation of slip length should take into account all parameters of the interaction objects, but it is a very hard task [19] to do this. I n fact, the contact angle is a more comprehe- nsive expression of interactions between liquid and solid surface, and the weaker the solid-f id intera- ction is, the larger the contact angle is. So it may be a feasible and advisable way to use contact angle as control parameter to simulate the slip length.4. ConclusionThe LBM has been successfully applied in this work to simulate contact angle of a fluid on a solid surface and slip length of a fluid flowing over a solid surface. Both the non-ideal interaction betwee p G d (c te another parameter of abs G ) have significant impact on the contact angle and slip length. However, they have little influence on the relationship between the contact angle and slip length. Our numerical results confirm that there is a low-density layer between the bulk liquid, and that the wetting properties of the wall have an important influence on the velocity profile. The more hydrophobic the w l is, the lower density of fluid is. Thus, the slip cannot be ignored in the micro- flow.References[1] HYVALUOMA J., HARTI NG J. Slip flow over stru-ctured surfaces with entrapped microbubbles[J]. Physi- cal Review Letters, 2008, 100(24): 246001.[2]DI Qin-fe method[J]128(in Chin [3] BURTON Z., BHUSHAN B. Hydrophobicity, adhesion,and friction properties of nanopatterned polymers and scale dependence for micro-and nanoelectromechanical systems[J]. Nano Letters, 2005, 5(8): 1607-1613.ZHANG J. Lattice Boltzmann method for microfluidics:Models and applications[J]. Microfluidics and Nano- fluidics, 2010, 10(1): 1-28.KHAN M., HAY shearing flows in a porous medium[J]. Acta Mechan- nic Sinica, 2008, 24(1): 51-59.WANG Xin-liang, DI Qin-feng and ZHANG Ren-lianget al. Progress in theories of super-hydrophobic surface slip effect and its application to drag reduction techno- logy[J]. Advances in Mechanics, 2010, 40(3): 241- 249(in Chinese).[7] CHEN Yan-yan, YI Hou-hui and LI Hua-bing Boun-dary slip and surface interaction: A lattice Boltzmann simulation[J]. Chinese Physics Letters,184-187.SHAN X., CHEN H. Lattice Boltzmann model for simu-lating flows with multiple phases and components[J]. Physical Review E, 1993, 47(3): 1815-1819.SHAN X., CHEN H. Simulation of nonideal gases andliquid-gas phase transitions by the lattice Boltzmann equation[J]. Physical Review E, 1994, 49(4): 2941- 2948.HUANG H al. Proposed approximation for contact angles in Shan- and-Chen-type multicomponent multiphase lattice Boltzmann models[J]. Physical Review E, 201-6.[11] ZHANG Ren-liang, DI Qin-feng and WANG Xin-liang,et al. Numerical study of wall wettabilities and topo- graphy by lattice Boltzmann method[J]. Journal of Hydro- dynamics, 2010, 22(3): 366-372.BENZI R., BIFERALE L. and SBRAGAGLIA M. et al.Mesoscopic modeling of a two-phase flow in the pre- sence Review E, 2006, 74(2): 021509.[13] QIAN Y. H., DމHUMIERES D. and LALLEMAND P.Lattice BGK models for Navier-Stokes equations[J]. Europhysics Letters, 1992, 17(6): 479-484.SUKOP M. C., THORNE D. T. Lattice Boltzmannmodeling: An introduction for geoscientists and engineers [M]. Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer- Verlag, 2006.MARTYS N. S., CHEN H. Simu nent fluids in complex three-dimensional geometries by the lattice Boltzmann method[J]. Physical Review E, 1996, 53(1): 743-750.[16] GUO Zhao-li, ZHENG Chu-guang. The principle andapplication of the method [M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2009(in Chinese).540[17]04, 70(5): 1-4.06, 55(10): 5305-5310(in Chinese). 9] HARTI NG J., KUNERT C. and HERRMANN H. J.Lattice Boltzmann simulations of apparent slip in hydrophobic microchannels[J]. Europhysics Letters,2006, 75(2): 328-334.ZHANG J., KWOK D. Y. Apparent slip over a solid-liquid interface with a no-slip boundary condition[J].Physical Review E, 20[18] CAO Bing-Yang, CHEN Min and GUO Zeng-Yuan.Velocity slip of liquid flow in nanochannels[J]. ActaPhysica Sinica, 20[1。

第50卷第12期表面技术2021年12月SURFACE TECHNOLOGY·233·电连接器微动腐蚀损伤行为与机理研究综述郁大照1,刘琦1,2,冯利军3,程贤斌1,4(1.海军航空大学 航空基础学院,山东 烟台 264000;2.92279部队,山东 烟台 264000;3.西南技术工程研究所,重庆 400039;4.92095部队,浙江 台州 318000)摘要:电连接器在服役期间,其电接触界面很容易受到振动和微位移的影响,并在腐蚀气氛的作用下,产生微动腐蚀损伤。

当接触电阻值(Electrical contact resistance,ECR)超过一定阈值时,即判定为接触失效。

人们对电接触微动腐蚀问题的认识过程是随着工业社会的发展和研究手段的进步而不断逐步深入的,因此从行为和机理两个方面综述了微动腐蚀研究的发展和现状。

为了降低ECR,提高电接触的耐久性,研究人员围绕材料、镀层种类和厚度、接触力、振幅、频率、温度、相对湿度、气体氛围等因素对微动腐蚀的影响做了大量的试验和分析工作,介绍了其中比较活跃的研究团队以及他们的主要工作。

分别详细介绍了Antler和Bryant描述的微动腐蚀模型,4种不同微动滑移状态的产生机制和微观形貌分析,进而对ECR 产生的影响。

由于电连接器受到振动应力、温度应力和电应力的综合作用,在内部接触件上发生电-热-机械多物理场耦合作用,故综述了材料性能与行为、接触条件和环境条件3个方面10个因素的影响作用。

还归纳总结了应用于电接触微动腐蚀研究的主要方法,最后从多因素耦合作用、海洋环境影响和射频连接器应用3个角度探讨了未来研究的重点方向。

关键词:电连接器;电接触;微动;微动腐蚀;ECR中图分类号:TG172 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1001-3660(2021)12-0233-13DOI:10.16490/ki.issn.1001-3660.2021.12.023Review on the Behavior and Mechanism of Fretting CorrosionDamage of Electrical ConnectorsYU Da-zhao1, LIU Qi1,2, FENG Li-jun3, CHENG Xian-bin1,4(1.School of Basic Sciences for Aviation, Naval Aviation University, Yantai 264000, China;2.Unit 92279 of the PLA, Yantai 264000, China;3.Southwest Institute of Technology and Engineering,Chongqing 400039, China; 4.Unit 92095 of the PLA, Taizhou 318000, China)ABSTRACT: During the service period of electrical connectors, the electrical contact interface is subjected to vibration and micro displacement easily, and under the action of corrosive atmosphere, fretting corrosion damage will occur. When the value of Electrical Contact Resistance (ECR) exceeds a certain threshold, it is determined to be a contact failure. With the development of industrial society and the progress of research methods, people’s understanding of electrical contact fretting corrosion has收稿日期:2021-01-18;修订日期:2021-04-28Received:2021-01-18;Revised:2021-04-28基金项目:国家自然科学基金(51375490)Fund:Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51375490)作者简介:郁大照(1976—),男,博士,教授,主要研究方向为腐蚀防护与控制。