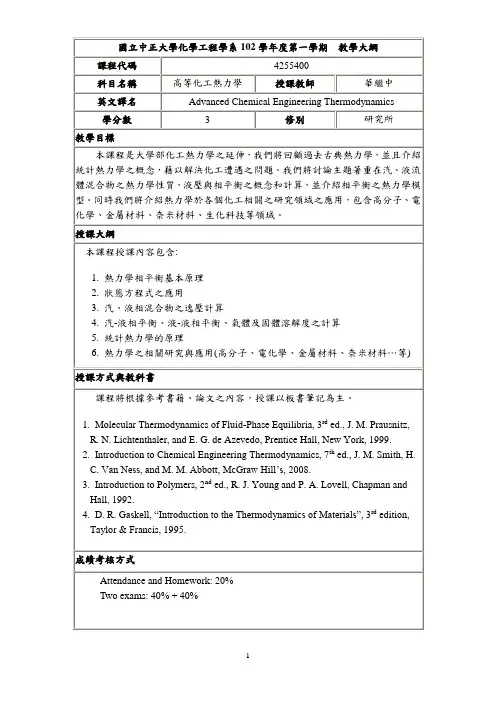

Lichtenthaler& Ernst

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:100.76 KB

- 文档页数:13

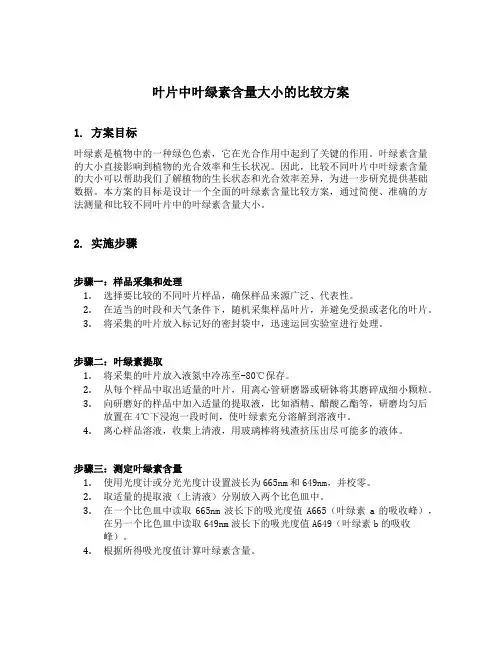

叶片中叶绿素含量大小的比较方案1. 方案目标叶绿素是植物中的一种绿色色素,它在光合作用中起到了关键的作用。

叶绿素含量的大小直接影响到植物的光合效率和生长状况。

因此,比较不同叶片中叶绿素含量的大小可以帮助我们了解植物的生长状态和光合效率差异,为进一步研究提供基础数据。

本方案的目标是设计一个全面的叶绿素含量比较方案,通过简便、准确的方法测量和比较不同叶片中的叶绿素含量大小。

2. 实施步骤步骤一:样品采集和处理1.选择要比较的不同叶片样品,确保样品来源广泛、代表性。

2.在适当的时段和天气条件下,随机采集样品叶片,并避免受损或老化的叶片。

3.将采集的叶片放入标记好的密封袋中,迅速运回实验室进行处理。

步骤二:叶绿素提取1.将采集的叶片放入液氮中冷冻至-80℃保存。

2.从每个样品中取出适量的叶片,用离心管研磨器或研钵将其磨碎成细小颗粒。

3.向研磨好的样品中加入适量的提取液,比如酒精、醋酸乙酯等,研磨均匀后放置在4℃下浸泡一段时间,使叶绿素充分溶解到溶液中。

4.离心样品溶液,收集上清液,用玻璃棒将残渣挤压出尽可能多的液体。

步骤三:测定叶绿素含量1.使用光度计或分光光度计设置波长为665nm和649nm,并校零。

2.取适量的提取液(上清液)分别放入两个比色皿中。

3.在一个比色皿中读取665nm波长下的吸光度值A665(叶绿素a的吸收峰),在另一个比色皿中读取649nm波长下的吸光度值A649(叶绿素b的吸收峰)。

4.根据所得吸光度值计算叶绿素含量。

步骤四:数据处理和结果分析1.计算叶绿素含量的方程为:叶绿素含量(mg/g)= 20.2 * (A665 - 0.057 *A649)(根据Lichtenthaler和Wellburn的方程)。

2.对每个样品进行重复测定,并计算平均值和标准差。

3.使用合适的统计方法(如t检验、方差分析等)比较不同样品之间的叶绿素含量大小。

4.绘制适当的图表(如柱状图、箱线图等)展示比较结果,并进行数据解读和分析。

荧光总结叶绿素中存在⼀定量的叶绿素蛋⽩复合物,其中影响光能吸收的因素是叶绿素蛋⽩复合物的含量和成分⽐例,捕光蛋⽩复合体中叶绿素a/b值较为关键,较⾼⽐例的捕光蛋⽩复合体(LHCP)有利于弱光下植物吸收和利⽤光能(Sane,1977)。

叶绿素a/b值,即叶绿素a与叶绿素b的⽐值,也与光合作⽤速率有密切关系:⽐值低,有利于吸收光能;⽐值⾼,在强光下的光合速率通常较⾼,抵抗光抑制能⼒较强(储钟稀等,1986)。

同时,叶绿素含量与该⽐值呈负相关,即叶绿素含量⾼,叶绿素a/b ⽐值较低,作物叶⾊较深。

也有⼈报道认为叶绿素a/b⽐值与光合作⽤速率呈显著的负相关,该⽐值也可能是影响光合作⽤速率的内在因⼦之⼀。

“光能被⾊素分⼦吸收以后,并不是全部⽤于光合作⽤:⼀部分光能被传递到光反应中⼼,⽤于光化学反应;⼀部分光能可以辐射成荧光的⽅式被耗散掉;另⼀部分光能以热辐射的⽅式耗散掉,⾊素发射荧光的能量与⽤于光合作⽤的能量相互竞争,这是以叶绿素a荧光通常被作为光合作⽤⽆效指标的依据”(植物⽣理学2003:123),此外分⼦的荧光特性是由该分⼦的化学性质和周围环境因素的相互作⽤所控制的,因此叶绿素荧光测量是以叶绿素a荧光作为探针,探测和研究植物光合⽣理状况及各种外界因⼦对其的影响,是⽆损伤研究光合作⽤过程的重要⼿段(林世青等1992; Krause and Weis 1988)。

植物叶⽚荧光动⼒学参数与光合特性的关系在⾃然条件下,叶绿素荧光和光合作⽤的关系⼗分密切(Bolhar-Nordenkampf H Ret al. 1989;Genty B et al. 1989;Schreiber U et al. 1994 ),⼀⽅⾯是当强光持续照射植物时,为了避免叶绿体吸收光能超过光合作⽤过程中光化学反应的消耗能⼒及过量的光能灼伤光合机构,荧光起到了重要的保护作⽤:⼀部分光能以荧光的⽅式被耗散掉(Gilmore A and Gofindjee,1999);另⼀⽅⾯,⾃然条件下叶绿素荧光和光合速率⼀般是呈负相关的,当荧光变弱时光合速率就⾼,反之亦然,植物的营养受胁程度与光合作⽤的荧光特性有着密切的关系(徐彬彬等2000;Krause G H and Weis E 1984;Liehtenthaler H K and Rinderle U 1984;Mefarlane J C er al. 1980;Sehreiber U and Bilger W 1987;),因此叶绿素荧光可作为营养诊断探测叶⽚光合功能的快速、⽆损伤探针(张⽊清2005)通过植物荧光特性探测可以了解植物的⽣长发育以及对逆境胁迫、病⾍害等的⽣理响应,与“表观性”的⽓体交换指标相⽐叶绿素荧光更具有反映“内在性”的特点(Lin S Q etal. 1992)。

外源一氧化氮供体硝普钠对番茄幼苗盐胁迫伤害的缓解作用孙德智;杨恒山;张庆国;范富;苏雅乐其其格;彭靖;韩晓日【摘要】以硝普钠(SNP)为NO供体,番茄品种秦丰保冠幼苗为材料,研究50~800μmol·L-1 SNP对100 mmol·L-1 NaCl下番茄幼苗生长、光合色素含量、气体交换参数、叶绿素荧光参数、膜脂过氧化及抗氧化酶活性的影响.结果显示:1)盐胁迫下,不同浓度SNP处理的番茄幼苗生长抑制均能得到有效缓解,同叶片叶绿素含量、光合速率(Pn)、气孔导度(Gs)、最大荧光(Fm)、PSⅡ最大光化学效率(Fv/Fm)、实际光化学效率(ΦPSⅡ)和光化学淬灭系数(qP)显著升高,初始荧光(Fo)和非光化学淬灭系数(qN)显著降低,且SNP浓度为100μmol·L-1变幅均达最大;2)番茄幼苗在盐胁迫下叶片过氧化氢酶(CAT)活性变化不显著,超氧化物歧化酶(SOD)和过氧化物酶(POD)活性显著升高,除400、800μmol·L-1 SNP处理抑制POD活性升高外,各浓度SNP处理均可促进上述3种酶活性的升高,并使叶片丙二醛含量和?解质渗出率显著降低,其中以100μmol·L-1 SNP处理变化最显著.研究表明,外源NO供体SNP主要通过增强番茄幼苗叶片的光合能力来缓解盐胁迫对其造成的氧化伤害,进而提高了番茄植株的耐盐性.【期刊名称】《浙江农业学报》【年(卷),期】2019(031)008【总页数】9页(P1286-1294)【关键词】f氧化氮;NaCl胁迫;番茄;光合特性;叶绿素荧光;抗氧化酶【作者】孙德智;杨恒山;张庆国;范富;苏雅乐其其格;彭靖;韩晓日【作者单位】内蒙古民族大学农学院,内蒙古通辽 028000;内蒙古民族大学农学院,内蒙古通辽 028000;内蒙古民族大学农学院,内蒙古通辽 028000;内蒙古民族大学农学院,内蒙古通辽 028000;内蒙古民族大学农学院,内蒙古通辽 028000;沈阳农业大学土地与环境学院,土肥资源高效利用国家工程实验室,辽宁沈阳110866;沈阳农业大学土地与环境学院,土肥资源高效利用国家工程实验室,辽宁沈阳110866【正文语种】中文【中图分类】S641.2盐害是限制作物生产潜力发挥的主要非生物逆境因子之一,是威胁生态安全、制约农业可持续发展的全球性问题。

光质对芹菜叶片光合色素和光合荧光特性的影响尹娟【摘要】以发光二极管(LED)为光源、荷兰西芹为试材探究红光、蓝光、红蓝(6∶1)、红蓝(2∶1)和白光(对照)对芹菜光合色素、光合特性及叶绿素荧光的影响.结果表明,芹菜的Fv/Fm和Fv/Fo趋势一致,表现为红蓝光(6∶1)>红蓝光(2∶1)>红光>白光>蓝光;ΦPSⅡ和qP在红蓝光(6∶1)下最高.光质对叶绿素a和叶绿素(a+b)的影响与Fv/Fm和Fv/Fo趋势一致,而叶绿素b含量在红蓝光(2∶1)下最高,红光下最低;类胡萝卜素在红蓝光(6∶1)下最高,蓝光下最低.不同光质下芹菜光合速率与蒸腾速率、气孔导度整体上呈正相关关系,与胞间CO2浓度呈负相关关系;除胞间CO2浓度在蓝光下最高外,光合速率、蒸腾速率和气孔导度均在红蓝光(6∶1)下最高.综合以上各光合指标,以红蓝光(6∶1)照射较佳.【期刊名称】《江苏农业科学》【年(卷),期】2018(046)004【总页数】4页(P116-119)【关键词】芹菜;光质;光合色素;光合特性;荧光【作者】尹娟【作者单位】信阳农林学院,河南信阳464000【正文语种】中文【中图分类】S636.301光质是植物生长发育的重要环境因子。

光合作用有效的可见光光谱在380~760 nm范围内,这一区间的波长对植物的形态建成、次生代谢、生理代谢、光周期及营养品质具有调节作用[1]。

高等植物的光系统及光信号转导系统,能够对光质、光照度、照射角度和时间、光质作出适应性反应[2]。

光质影响种子萌发,其中红光与远红光的比例对种子能否充分萌发起决定作用[3]。

叶片的形成与光合器官发育受光质调控,莴苣在红蓝绿组合光下叶面积最大[4],人参叶片在蓝膜下基粒排列松散,红膜下排列整齐[5]。

红光降低茎的生长速率,而远红光能解除这一效应[6]。

蓝光促进侧根生长,红光促进组培苗分化生长。

蓝光下植物蛋白质含量高,而红光下碳水化合物含量高[7]。

学院:生命科学学院专业:植物学姓名:乔亚飞学号:216021001 Overexpressionof SsCHLAPXs confersprotectionagain stoxidativestressinducedbyhighlightintransgenicArabidopsisthaliana盐地碱蓬CHLAPXs基因在拟南芥中过表达可以保护由强光引起的氧化应激作者:Cai-HongPang,KeLiandBaoshanWang期刊:PhysiologiaPlantarum影响因子:3.52摘要:为了研究抗坏血酸过氧化物酶(CHLAPX)在活性氧清除系统中的作用的重要性,本实验克隆了盐地碱蓬chlapx(sschlapx)编码基质APX(sAPX)和类囊体膜APX(tAPX)。

基质sapx 的cDNA 由1726个核苷酸组成,其中包括一个1137bp开放阅读框(ORF),编码378个氨基酸。

类囊体tapx 的cDNA由1561个核苷酸组成,包括1284bp的开放阅读框,编码427个氨基酸。

ss.sapx与ss.tapx 氮端378个氨基酸是相同的,而炭末端49种氨基酸不同。

通过农杆菌转化法将apx转入到拟南芥中,用高光(1000μmolm−2−1)处理转基因株系。

研究结果表明在强光下,转基因株系的Fv/Fm和叶绿素含量在正常光照下差异较小,但是在强光处理下过表株系均显著高于野生型。

这些结果表明,在强光胁迫下,SsCHLAPX对叶绿体中活性氧的清除起着重要的作用。

APX同工酶大致可以分为四类:细胞质型APX(cAPX)、叶绿体型APX(chlAPX)、线粒体型APX(mitAPX)和微体型APX(mAPX)。

chlAPX具有两种类型的同工酶:基质型(sAPX)和类囊体(tAPX)。

之前有报道称拟南芥tAPX和豌豆APX基因在烟草中过表达可以降低百草枯对其产生的氧化胁迫(Murgiaetal.2004,Yabutaetal.2002)。

叶绿素含量测定方法实验14 叶绿素a和b含量的测定(分光光度法)一、目的学会Chla、b含量的测定方法,了解叶片中Chla、b的含量。

二、材料用具及仪器药品菠菜叶片、721分光光度计、天平、研钵、剪刀、容量瓶(25ml)、漏斗、滤纸、乙醇(95%)三、原理叶绿素a、b在波长方面的最大吸收峰位于665nm和649nm,同时在该波长时叶绿素a、b的比吸收系数K为已知,我们即可以根据Lambert Beer定律,列出浓度C与光密度D之间的关系式:D=83.31Ca+18.60C…………………………….(1) 665bD=24.54Ca+44.24 C…………………………….(2) 649b(1)(2)式中的D66、D649为叶绿素溶液在波长665nm和649nm时的光密度。

5为叶绿素a、b的浓度、单位为每升克数。

82.04、9.27为叶绿素a、b在、在波长665nm时的比吸收系数。

16.75、45.6为叶绿素a、b在、在波长649nm时的比吸收系数。

1)(2),则得 : 解方程式(C=13.7 D—5.76 D………………………(3) A665649C=25.8 D—7.6 D……………………… (4) B649665G=C+C=6.10 D+20.04 D………(5) AB665649此时,G为总叶绿素浓度,C、CB为叶绿素a、b浓度,单位为每升毫克,利用上面(3)A(4)(5)式,即可以计算叶绿素a、b及总叶绿素的总含量。

四、方法步骤1(称取0.1克新鲜叶片,剪碎,放在研钵中,加入乙醇10ml共研磨成匀浆,再加5ml乙醇,过滤,最后将滤液用乙醇定容到25ml。

2(取一光径为1cm的比色杯,注入上述的叶绿素乙醇溶液,另加乙醇注入另一同样规格的比色杯中,作为对照,在721分光光度计下分别以665nm和649nm波长测出该色素液的光密度。

计算结果:251叶绿素a含量(mg/g. FW)= ,,CA10000.2251叶绿素b含量(mg/g.FW)= C,,B10000.2251叶绿素总量(mg/g.FW)=G,, 10000.2五、实验报告计算所测植物材料的叶绿素含量。

Innovation Intermediaries:Why Internet Marketplaces for Technology Have Not Yet Met the Expectations Ulrich Lichtenthaler and Holger ErnstA few years ago,internet marketplaces for technology,e.g.,,received great attention. In the light of open innovation processes,it was assumed that they could be an appropriate means to overcome the imperfections in the markets for technology.Little is known about the performance of these innovation intermediaries,and very limited information is provided by thefirms that run the marketplaces.Therefore,we have interviewed intellectual property and technology managers in25medium-sized and large industrial companies,who represent the potential licensees and licensors in the internet exchanges.The results show relatively limited success rates of internet marketplaces regarding the number of technology transactions that have been initiated,particularly in comparison with the hopes that had initially been placed in these tools.Moreover,important problems and recent trends in these web-enabled ex-changes are identified,and propositions are developed regarding major consequences for initiating and managing technology transactions.IntroductionI n recent years,the markets for technology have received great attention from research-ers and practitioners(Guilhon,2001;Gans& Stern,2003).In these markets,firms acquire and commercialize technological knowledge to complement and capitalize on their technology portfolios(Clarke&Rollo,2001;de Weerd-Nederhof&Fisscher,2003).In contrast to the markets for most products and services, the markets for technology have remained imperfect(Cesaroni,2004;Lichtenthaler& Ernst,2007).As technological knowledge is usually commercialized by selling products and services,the markets for technology are not common(Gans&Stern,2003;V an Looy, Martens&Debackere,2005).At the same time, there are many imperfections in these markets, which result in high transaction costs(Arora, Fosfuri&Gambardella,2001;Davis&Harri-son,2001).These two phenomena are mutually dependent because a reduction of the imperfec-tions would lead to a stronger use of the tech-nology markets,which would reduce some of their deficiencies(Lichtenthaler,2007).Along with the‘new economy’hype,many researchers and practitioners assumed that the internet could helpfirms to overcome these market imperfections.The examples of successful pioneering companies,e.g.,IBM, which have realized great benefits from technology licensing,further increased the great hopes(Kline,2003;Chesbrough, 2007).In particular,internet marketplaces for technology were expected to encourage inter-organizational technology transactions.A variety of companies,which were often backed by venture capital,have emerged to facilitate technology trade through internet platforms. Prominent examples are ,NineSigma, InnoCentive,and the Patent&Licenses Exchange(Bauman,2000;Huston&Sakkab, 2006).While their service offerings differ,most of thesefirms try to become the central web-enabled marketplace for trading technological knowledge(Bauman,2000;Chesbrough,2006). Because of these great hopes,there is now–several years later–also great interest in the performance of these marketplaces(Howells, 2006;Huston&Sakkab,2006).Very little is known about their success regarding the number of technology transactions that have been initiated,and hardly any information is distributed by thefirms that run the market-places.Therefore,we have asked the potentialVolume17Number12008 doi:10.1111/j.1467-8691.2007.00461.x ©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishingbeneficiaries of these marketplaces about their experiences.We have interviewed intellec-tual property and technology managers of technology-intensive companies,who repre-sent the potential licensees and licensors in these markets.Accordingly,this article addresses the following central questions. What are the experiences of industrialfirms regarding internet marketplaces for technol-ogy?Why have internet marketplaces for tech-nology not yet met the great expectations of researchers and practitioners?The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.In the next section,we provide a brief overview of previous research.Afterwards,the research design is described.Subsequently,the results of the study are presented before highlighting some recent trends in thefield.On this basis, we discuss theoretical and managerial impli-cations and develop propositions regarding major consequences for initiating and manag-ing technology transactions.Finally,opportu-nities for further research are presented.As such,this article offers several contribu-tions.It is among thefirst empirical studies on internet marketplaces for technology to analyse their managerial implications.In the light of increasing interest in technology transactions (Rivette&Kline,2000;Grant&Baden-Fuller, 2004),it deepens our understanding of the dis-crepancies between a few successful pioneer-ingfirms in trading technology and many others.Moreover,it contributes to overcom-ing the under-emphasis on empirical research into technology intermediaries(Spulber,1999; Howells,2006).Accordingly,this research deepens our understanding of managing technology transactions and realizing value from technology in open innovation systems (Gassmann,2006;van der Meer,2007).Finally, ourfindings have implications for emerging themes in knowledge management, e.g., organizational boundaries(Arora,Fosfuri& Gambardella,2001;Santos&Eisenhardt, 2005).These issues have been highlighted as areas ripe for further study in recent reviews of the literature on intermediaries(Howells, 2006),knowledge management(Argote, McEvily&Reagans,2003),technology exploi-tation(Lichtenthaler,2005),and open innova-tion(West,V anhaverbeke&Chesbrough,2006).Past ResearchInterest in the role of technology intermediar-ies has emerged from variousfields over the past20years(Spulber,1999;Chesbrough, 2006).Thesefields include:(1)literature on technology transfer and diffusion,(2)research into managing innovation processes,(3)litera-ture on systems and networks of innovation,and(4)research into service organizations(Howells,2006).Thefirst line of research hasidentified the role of intermediaries in iden-tifying partners,helping package technology,selecting suppliers and providing support indeal making(Watkins&Horley,1986;Seaton&Cordey-Hayes,1993).The second stream hasaddressed intermediaries as organizations,whose key function is their brokering role inthe technology transfer process(Hargadon&Sutton,1997;McEvily&Zaheer,1999).Thethird line of research has underscored the roleof public and private intermediaries that helpcompanies to adapt specialized solutions to theneeds of individual userfirms(Stankiewicz,1995;Lynn,Reddy&Aram,1996).The fourthstream has highlighted the bridging roles thatcertain types of servicefirms play in innovationsystems(Howells,1999;Miles,2000).Regarding more general research into inter-firm exchanges,transaction cost theory needsto be tailored to the specific characteristicsof the technology markets(Seely Brown&Duguid,1998).In particular,firms may influ-ence their transaction costs in the medium tolong term by developing dynamic capabili-ties of trading technology based on learningeffects.The examples of successful pioneeringfirms in out-licensing support this capability-based view of outward technology transfer(Davis&Harrison,2001;Kline,2003).More-over,the capability-based perspective hasreceived great attention in inward technologytransfer,above all in the literature on absorp-tive capacity(Cohen&Levinthal,1990;Zahra&George,2002).In conclusion,there arevarious lines of research that have deepenedour understanding of intermediaries in themarkets for technology,but the insights intotheir roles are limited,especially regardinginternet marketplaces for technology(Licht-enthaler,2005;Howells,2006).Research DesignIn the light of the limitations of previousresearch and increasing technology trade,it isthe goal of this study to gain insight into theintermediating role of internet marketplacesfor technology.The study’s focus is on theexperiences of medium-sized and large indus-trial companies whose main business is inter-nal technology exploitation.Accordingly,thesefirms focus on the application of technologiesin their own products and services(March,1991;Cesaroni,Di Minin&Piccaluga,2005).Thus,we have analysed the internet-basedtechnology exchanges neither of start-up com-panies nor offirms that provide mainly R&DVolume17Number12008©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishingservices.Nearly all of the companies in the sample have at least considered or have already realized technology transactions as the technology source and recipient.Therefore,all firms could be analysed regarding potential inward and outward technology transfer.A thorough review of previous research has shown that technology trade through internet marketplaces has not yet been examined in detail(Lichtenthaler,2005;Howells,2006). Accordingly,a qualitative research design was chosen to respond to the need for deep under-standing,local contextualization,and causal inference(Miles&Huberman,1994).Our dis-cussion of past research has demonstrated that these needs apply to the analysis offirms’experiences with internet marketplaces for technology.Hence,the case study method was chosen because of the study’s exploratory character.In the light of a highly complex research object,the case study method allowed for aflexible and comprehensive examination of the issues.The process of conducting case studies followed the suggestions that have been given in seminal works on case study research(Eisenhardt,1991;Yin,2003;Eisen-hardt&Graebner,2007).Thus,our approach was similar to the designs of case study-based works that have been published recently in leading journals(Schweizer,2005).Through the focused selection of medium-sized and large industrial companies,different experiences with internet marketplaces could be analysed(Miles&Huberman,1994).Tech-nology trade was studied at the organizational level and at the level of specific technology transfer projects.By applying thefirm-level view,the overall experiences were analysed. By examining specific projects,thefirms’tech-nology transfer processes were studied in the context of a specific project.Only the simul-taneous analysis of the micro level of projects and the macro level of corporate experiences allowed for drawing implications for managing technology trade(Miles&Huberman,1994). Besides analysingfirms from various indus-tries,the sample comprisesfirms where licensing plays different roles regarding its importance,objectives and management.Thus, the experiences of thesefirms provided differ-ent perspectives on technology marketplaces. Afterfive preliminary unstructured inter-views,questionnaires were used as a basis for semi-structured interviews in thefinal study. This procedure ensured comparability and ample opportunity for unobstructed narration. The data collection process followed Yin (2003).During the interviews,the interviewer took notes and typed them up each night. All data were included in writing up of the cases,even when not specifically requested in the questionnaire.Furthermore,additional documents,e.g.,company-internal analyses of licensing transactions and company-external publications,were studied.Next,the memoing process was followed to record patterns that the interviewer noted within and across cases (Yin,2003).Each interview was structured to facilitate within-case as well as subsequent cross-case analyses(Miles&Huberman,1994). After these analyses,the implications that are presented in this article were drawn.In companies with a dedicated licensing unit,this unit’s head was interviewed.In com-panies without a dedicated unit,we talked to the head of the corporate intellectual property department.In ten companies,a second person from the R&D department,who is not directly occupied with licensing,was interviewed.By drawing on the insights of this second person, a more detailed picture of afirm’s experiences could be gained.Altogether,35persons were interviewed in25German and Swiss compa-nies.Thefirms’average R&D intensity is about 6per cent.Seven of thesefirms are active in the chemical/pharmaceutical industry;nine are active in the automotive/machinery industry; and the other ninefirms are active in the semiconductors/electronics industry.With an average of8,457employees and average rev-enues of€2,135million,the companies in the sample are relatively large.We followed a sampling strategy in which we sought variance regarding the topics analy-sed in this study.In particular,the choice of industries was influenced by prior research, which reported different functions of technol-ogy licensing in these industries(Grindley& Teece,1997;Teece,1998;Rivette&Kline,2000). As the purpose of the study was deepening our understanding of internet marketplaces for technology,the sample was not selected to ensure representation of the population of all medium-sized and large industrialfirms. Instead,the sample was selected to include sufficient variation to explore factors relating to the internet marketplaces.Despite participa-tion being voluntary,the sample was not a self-selected group offirms.As the following section shows,there was sufficient variance in the managerial approaches offirms to internet marketplaces for technology.This sampling process followed prior works in leading jour-nals(e.g.,Edmondson,Bohmer&Pisano, 2001).ResultsCurrent PracticeAll companies are well aware of the potential benefits of internet marketplaces and have atVolume17Number12008©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishingleast studied the web pages of different service providers in detail.In various cases,however, no consideration had been given to actually putting technologies into the marketplaces because the strategy of thesefirms focused exclusively on the application of technologies in their own products.Similarly,various com-panies did not have any interest in licensing in technologies through these platforms because of their focus on internal R&D.By contrast, manyfirms have actively tried to use the mar-ketplaces by offering technologies or search-ing in detail for interesting technologies.In general,thefirms that addressed the internet marketplaces most actively are thefirms that also carry out internal activities of initiating technology transactions more actively.For instance,most of thefirms that offered various technologies on the internet market-places also have a dedicated internal organiza-tional unit that is directed towards managing technology licensing activities.Thisfinding points to the complementary character of internet marketplaces and afirm’s internal activities of identifying technology transfer opportunities.Finally,these complementary activities may result in a portfolio of inter-firm technology transactions that comprises various contractual forms,e.g.,licensing agree-ments,strategic alliances and joint ventures. Some of these technology-based relations even ended up in a transfer of parts of organiza-tional units beyond the transfer of technolo-gical knowledge,i.e.,acquisitions in inward technology transfer and spin-offs in outward technology transfer.For example,one contact evolved into a strategic alliance that eventually resulted in the acquisition of a part of a rela-tively smallfirm by one of the large chemical firms in the sample.In general,the success rate of relying on internet marketplaces for technology has been relatively low with regard to the number of technology transactions that have been ini-tiated,particularly in comparison with the hopes that had initially been placed in the mar-ketplaces.Many industrialfirms have invested substantial time and resources in preparing and documenting technologies for the internet exchanges and in searching for suitable tech-nologies.For instance,severalfirms have set up internal projects with participants from dif-ferent organizational units to decide on their technology offerings.However,most compa-nies have not realized any technology transac-tion by means of web-enabled platforms.The maximum of transactions for a single company has been one out-licensing agreement and one in-licensing agreement.As a result,most industry experts have rela-tively reserved attitudes to these marketplaces,which sharply contrast the euphoria thatexisted several years ago.Nearly allfirms thathave not actively tried to realize technologydeals are informed surprisingly well aboutthe unsuccessful activities of other companiesregarding the number of technology transac-tions that have been initiated through the mar-ketplaces.The limited success of thesefirmshas been communicated through informalinter-firm networks.On this basis,only two ofthe25companies wanted to give the internetmarketplaces another chance in the shortto medium term by offering a considerableportion of their technology portfolios on and closely screening furthermarketplaces.Onefirm even plans to assigna person exclusively to the co-ordinationof its technology offerings on andother internet marketplaces,particularly withregard to an adequate preparation and docu-mentation of the technologies.Regarding tech-nology acquisition,most companies still planto search the internet platforms or post a noticeof a technology need when trying to identifypotential technology sources in the future.However,thesefirms do not expect to realizemany licensing transactions by means of themarketplaces.Licensors’PerspectiveAccording to the industry experts,the mostsevere deficit of internet marketplaces is thatthe commercialization of technology throughthese platforms constitutes a relatively unsys-tematic approach because it does not add-ress specific technology customers.Instead,thefirm’s intention to license technologicalknowledge is communicated very broadly.Furthermore,offering a technology throughthe internet is a relatively passive approach.This offer merely constitutes an invitationto treat because the initiative for the actualtechnology transaction has to come from thepotential licensee.An additional reason why afirst inquiry has often not occurred is inherentin the technologies that have been offered.Inmany cases,the sourcefirms have put rela-tively unattractive technologies in the data-bases.The main aim behind these offers wasthe optimization of the technology portfolio byexternally leveraging technologies of relativelylimited value.Accordingly,the success rate of commercial-izing technology through these marketplacesmeasured by the number of technology trans-actions that have been initiated is relativelylow.Thus,it is necessary to offer a substantialportion of the technology portfolio to arrive ata single technology transaction.However,thisopen approach is often impossible because ofVolume17Number12008©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishingthe concerns of top management and high-ranking R&D employees.While these reluc-tant attitudes are partly based on rational arguments following corporate strategy,they are often complemented by irrational feelings of individuals,who are resistant to the idea of transferring afirm’s technology assets.This resistance is particularly strong if the technolo-gies are of relatively high value or close to a firm’s core technologies.Furthermore,offer-ing a large number of technologies requires substantial resources.A thorough presentation of the technologies is essential to generate interest from potential licensees.Because of these resource requirements,manyfirms argue that the time needed to identify tech-nology customers can be put to better using other–more proactive–commercialization channels.This is particularly true in cases where a firm may describe possible applications of a technology in relative detail.If these ideas exist,potential licensees may be identified in a more direct way by relying on thefirm’s exist-ing business relationships,i.e.,buyers,suppli-ers and competitors,or on its contacts in other industries through formal and informal net-works.As a result,internet marketplaces cur-rently do not seem to be an appropriate means to significantly reduce the transaction costs in the markets for technology from the perspec-tive of potential licensors.Moreover,the chal-lenge of identifying interesting applications before actively commercializing technology is not overcome.Because of the interdependen-cies between the limited use of the technology markets and the problems inherent in them, which may not directly be offset by web-enabled exchanges,this vicious circle is likely to persist in the future–at least to a certain degree.Licensees’PerspectiveSimilar to the licensors’perspective,industry experts consider the unsystematic approach to be the main disadvantage of identifying and acquiring technology by means of internet ually,it is difficult or impos-sible tofind an appropriate technology for a specific technology need.Despite containing large numbers of technologies,one reason for this problem is the limited number of tech-nologies that are offered in the marketplaces. While this limitation is inherent in a database approach,it is aggravated by the fact that many of the technologies represent residual knowl-edge,which is of relatively low value and unused in the sourcefirms.Moreover,the number of technologies that are offered in one particular technologicalfield is often limited.In many cases,the focus of the internet exchanges is still on the technologicalfields of the websites’founding members.If a particular technology need exists,it may therefore be easier to direct the resources for identifying potential technology sources to other channels.Examples of more systematic approaches are patent analyses and afirm’s networks.These networks not only encompass formal relationships with otherfirms, e.g., strategic alliances,but also informal personal relationships,e.g.,inter-firm contacts between technology or intellectual property experts. Furthermore,potential licensors may be observed in many cases as a part of regular technology intelligence processes.If no spe-cific technology need exists,the search for technologies in internet marketplaces is a random approach with limited chances of ini-tiating a technology transaction.Because of increasing technology convergence,the tech-nology descriptions on the web pages often do not include the specific application for which the technology need exists.Thus,the identifi-cation of a technology still requires a creative element by matching the particular technology with the application that the person who is searching the marketplace has in mind.For this challenge,posting a technology need does not represent a solution because it merely transfers the need to establish a link from the potential licensee to the potential licensor. An additional problem of externally acquir-ing technological knowledge is the fact that a firm will be continually observed by the poten-tial licensor regarding infringements of its intellectual property rights if no agreement is reached between the parties.This may happen for a number of reasons,e.g.,inappropriate prices or characteristics of the technologies. Finally,this process may lead to infringement lawsuits.In this context,one intellectual prop-erty expert frankly stated:‘Nobody likes to pay license fees’.In addition to these practical dif-ficulties,these factors are also brought forward to justify the‘Not Invented Here’syndrome, i.e.,negative attitudes to the acquisition of external technology.In particular,this bias may be found among R&D experts,who often tend to invent around the intellectual property rights of otherfirms instead of attempting to get a licence for these technologies.Integrated PerspectiveA comparison of the licensors’and licensees’perspectives shows major similarities between these views.The main problem of internet exchanges is the unsystematic nature of partner identification.Because of the limited success rate in identifying and realizingVolume17Number12008©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishingtransactions,the search process requires con-siderable resources.As technology transfer through web-based exchanges constitutes only one of a number of channels,the alternative ways appear more promising to manyfirms, particularly if a detailed idea exists for apply-ing a technology.Thus,internet marketplaces may only mitigate the difficulty of linking technologies to appropriate applications or vice versa,but this still represents the critical managerial challenge.In addition,the impor-tance of cultural barriers has to be highlighted, although they are not a problem specific to internet-based exchanges.These cultural bar-riers often prevent a more active approach to trading technology.In many cases,they may therefore be considered the underlying cause of refraining from technology transactions. An integrated perspective also points to some industry differences.Firms from the chemical/pharmaceutical industry appear to have initially attributed a higher importance to technology licensing through internet market-places thanfirms from the other industries. However,chemical/pharmaceutical compa-nies also seem to internally manage their licensing activities more proficiently than firms from the other industries.Thus,the data support prior research,which has underlined the high importance of licensing transactions in this sector.Accordingly,thesefirms are now relatively reluctant to use internet market-places for technology because alternative chan-nels,e.g.,informal inter-firm networks,seem to have provided an essential avenue for initi-ating technology transactions in this sector in the past.Similarly,the importance of internet marketplaces appears to be surprisingly low in the electronics/semiconductors industry although the relevance of licensing in this industry has been described in relative detail in prior research.By contrast,the potential of internet marketplaces for technology is con-sidered surprisingly high in the automotive/ machinery industry.As technology licensing in this sector has received limited attention in prior research,it deserves further study to offer a better understanding tofirms aiming at optimally utilizing their technologies in this field.DiscussionRecent TrendsVery recently,major changes have occurred in the strategic approach of various internet mar-ketplaces.While these developments could be observed in various marketplaces,they appear to have influenced in particular .At the beginning, focused on itsinternet-based infrastructure(Bauman,2000).Potential licensors put their offers online,whereas potential licensees could search fortechnologies in the database.Recently,how-ever, seems to have realized thatthe complexity of technological knowledgerequires a more active approach to exchangingtechnology.This new understanding of tech-nology transactions has led to sub-stantially transform its business model(Jahn,2005).Before this reorientation, hadabout80employees,who were occupiedmainly with marketing and acquiring newusers of its internet platform.After redirectingthe business model, employs about20people,who are not primarily occupiedwith marketing but with actively facilitatingtechnology transactions.Thus, nolonger focuses exclusively on its internet data-base.The internet platform still constitutes animportant feature,but attempts toplay a more active role in connecting licensorsand licensees.Thus,the business model hasbeen transformed from focusing on the web-enabled infrastructure towards concentratingon a more active approach to technologybrokering.Therefore,the20employees at comprise mainly scientists and engineers,often with PhD degrees in their technologicalfields.Their knowledge is used to facilitatedeals on technology packages instead of focus-ing on patent rights(Jahn,2005).These newservice offerings led to approximately ten tech-nology transfers in2004.Thisfigure is con-trasted with the90,000registered users,whichunderlines the difficulties in facilitating tech-nology transactions.As a result of the newstrategic approach,however, expectsto strongly increase the number of deals thatare closed as a result of its brokering activitiesin the coming years(Jahn,2005).Similar to thestrategic changes at ,various otherinternet marketplaces for technology thatwere created in recent years,e.g.,NineSigma,pursue a more active approach to facilitatingtechnology exchanges.Thus,a major portionof their service offerings refers to active bro-kering,whereas databases only representadditional infrastructure to facilitate deals.Thus,’s reorientation is not a singulardevelopment.Instead,it may represent a newapproach to internet marketplaces,which linksthem to active forms of technology brokering.Theoretical and Managerial ImplicationsThe limited success rates of internet exchangeswith regard to the number of technologytransactions that have been initiated haveVolume17Number12008©2008The AuthorsJournal compilation©2008Blackwell Publishing。