396.full

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:6.65 MB

- 文档页数:15

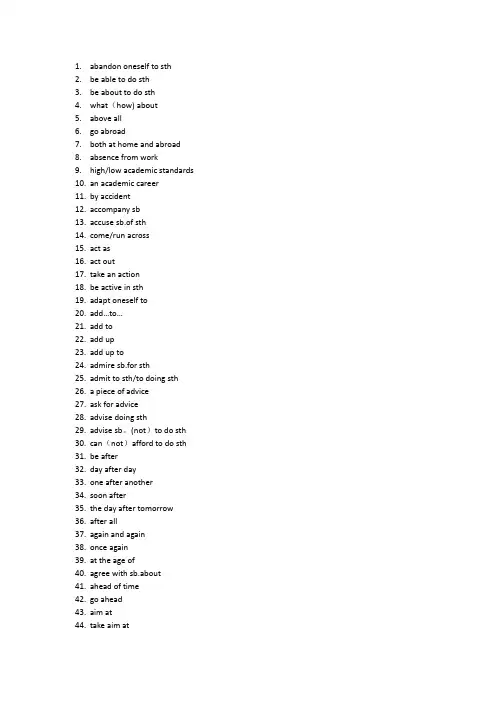

1.abandon oneself to sth2.be able to do sth3.be about to do sth4.what(how) about5.above all6.go abroad7.both at home and abroad8.absence from work9.high/low academic standards10.an academic career11.by accident12.accompany sb13.accuse sb.of sthe/run across15.act as16.act out17.take an action18.be active in sth19.adapt oneself to20.add…to…21.add to22.add up23.add up to24.admire sb.for sth25.admit to sth/to doing sth26.a piece of advice27.ask for advice28.advise doing sth29.advise sb。

(not)to do sth30.can(not)afford to do sth31.be after32.day after day33.one after another34.soon after35.the day after tomorrow36.after all37.again and again38.once again39.at the age of40.agree with sb.about41.ahead of time42.go ahead43.aim at44.take aim at45.by air46.in the air47.on the air48.on the air49.on the open air50.in the open air51.at the airport52.all along53.all at once54.all of a sudden55.all over56.all over the country/world57.all right58.all the time59.at all60.in all61.not at all62.allow sb。

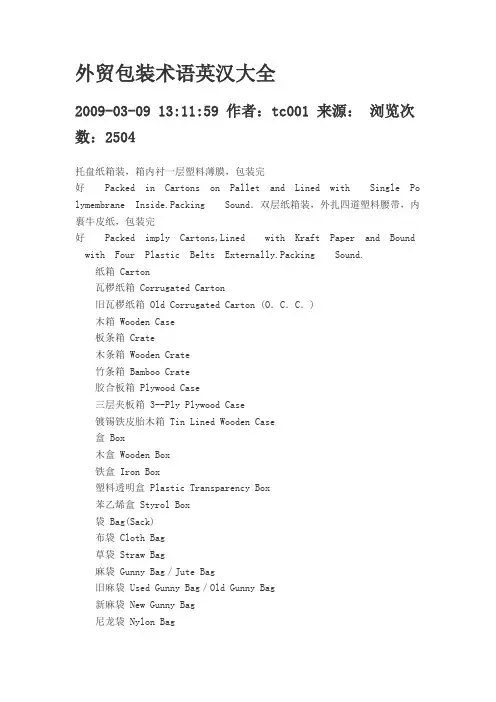

外贸包装术语英汉大全2009-03-09 13:11:59 作者:tc001 来源:浏览次数:2504托盘纸箱装,箱内衬一层塑料薄膜,包装完好Packed in Cartons on Pallet and Lined with Single Po lymembrane Inside.Packing Sound.双层纸箱装,外扎四道塑料腰带,内裹牛皮纸,包装完好Packed imply Cartons,Lined with Kraft Paper and Bound with Four Plastic Belts Externally.Packing Sound.纸箱 Carton瓦椤纸箱 Corrugated Carton旧瓦椤纸箱 Old Corrugated Carton (O.C.C.)木箱 Wooden Case板条箱 Crate木条箱 Wooden Crate竹条箱 Bamboo Crate胶合板箱 Plywood Case三层夹板箱 3--Ply Plywood Case镀锡铁皮胎木箱 Tin Lined Wooden Case盒 Box木盒 Wooden Box铁盒 Iron Box塑料透明盒 Plastic Transparency Box苯乙烯盒 Styrol Box袋 Bag(Sack)布袋 Cloth Bag草袋 Straw Bag麻袋 Gunny Bag/Jute Bag旧麻袋 Used Gunny Bag/Old Gunny Bag新麻袋 New Gunny Bag尼龙袋 Nylon Bag聚丙烯袋 Polypropylene Bag聚乙烯袋 Polythene Bag塑料袋 Poly Bag塑料编织袋 Polywoven Bag纤维袋 Fibre Bag玻璃纤维袋 Glass Fibre Bag玻璃纸袋 Callophane Bag防潮纸袋 Moisture Proof Pager Bag乳胶袋子 Emulsion Bag三层牛皮纸袋 3Ply Kraft Paper Bag锡箔袋 Fresco Bag特大袋 Jumbo Bag单层完整袋子 Single Sound Bag桶 Drum木桶 Wooden Cask大木桶 Hogshead小木桶 Keg粗腰桶(琵琶桶) Barrel胶木桶 Bakelite Drum塑料桶 Plastic Drum铁桶 Iron Drum镀锌铁桶 Galvanized Iron Drum镀锌闭口钢桶 Galvanized Mouth Closed Steel Drum 镀锌开口钢桶 Galvanized Mouth Opened Steel Drum 铝桶 Aluminum Drum麻布包 Gunny Bale (Hessian Cloth Bag)蒲包 Mat Bale草包 Straw Bale紧压包 Press Packed Bale铝箔包 Aluminium Foil Package铁机包 Hard-pressed Bale木机包 Half-pressed Bale覃(缸) Jar陶缸 Earthen Jar瓷缸 Porcelain Jar壶 Pot铅壶 Lead Pot铜壶 Copper Pot施 Bottle铝瓶 Aluminum Bottle陶瓶 Earthen Bottle瓷瓶 Porcelain bottle罐 Can听 Tin绕线筒 Bobbin笼(篓、篮、筐) Basket竹笼(篓、篮、筐) Bamboo Basket 柳条筐(笼、篮、筐) Wicker Basket 集装箱 Container集装包/集装袋 Flexible Container 托盘 Pallet件(支、把、个) Piece架(台、套) Set(Kit)安瓿 Amp(o)ule(药针支)双 Pair打 Dozen令 Ream匹 Bolt(Piece)码 Yard卷(Roll(reel)块 Block捆 Bundle瓣 Braid度 Degree辆 Unit(Cart)套(罩) Casing包装形状 Shapes of Packing圆形 Round方形 Square三角形 Triangular(Delta Type)长方形(矩形) Rectangular菱形(斜方形) Rhombus(Diamond)椭圆形 Oval圆锥形 Conical圆柱形 Cylindrical蛋形 Egg-Shaped葫芦形 Pear-Shaped五边形 Pentagon六边形 Hexagon七边形 Heptagon八边形 Octagon长 Long宽 Wide高 High深 Deep厚 Thick长度 Length宽度 Width高度 Height深度 Depth厚度 Thickness包装外表标志 Marks On Packing下端,底部 Bottom顶部(上部) Top(Upper)小心 Care勿掷 Don’t Cast易碎 Fragile小心轻放,小心装运 Handle With Care 起吊点(此处起吊) Heave Here易燃物,避火 Inflammable保持干燥,防泾 Keep Dry防潮 keep Away from Moisture储存阴冷处 Keep in a Cool Place储存干燥处 Keep in a Dry Place请勿倒置 Keep Upright请勿倾倒 Not to Be Tipped避冷 To be Protected from Cold避热 To be Protected from Heat在滚子上移动 Use Rollers此方向上 This Side Up由此开启 Open from This Side爆炸品 Explosive易燃品 Inflammable遇水燃烧品 Dangerous When Wet有毒品 Poison无毒品 No Poison不可触摩 Hand off适合海运包装 Seaworthy Packing毛重 Gross Weight (Gr.Wt.)六边形 Hexagon长六边形 Long Hexagon圆形 Circle/Round二等分圆 Bisected Circle双环形 Crossed Circle双圆形 Double Circle双带圆形 Zoned Circle长圆形 Long Circle椭圆形 Oval双缺圆形 Double Indented Circle圆内三角形 Triangle in Circle三角形 Triangle六角星形 Hexangular Star二重三角形 Double Triangle对顶三角形 Hourgrass Touching Triangle 内外三角形 Three Triangle十字形 Cross圆内十字形 Cross in Circle三角形 Angle义架形 Crotch直线 Line月牙形 Crescent心形 Heart星形 Star包装情况 Packing Condition散装 In Bulk块装 In Block条装 In Spear片装 In Slice捆(扎)装 In Bundle裸装 In Nude裸散装 Bare in Loose木托架立装 Straightly Stand on Wooden Shelf 传统包装 Traditional Packing中性包装 Neutral Packing水密 Water Tight气密 Air Tight不透水包 Water Proof Packing不透气包 Air Proof Packing薄膜 Film Membrane透明纸 Transparent Paper牛皮纸 Kraft Paper地沥青牛皮纸 Bituminous Kraft Paper腊纸 Waxpaper厚板纸 Cardboard Paper蒲、苇 Bulrush mat防水纸 Water Proof Paper保丽龙(泡沫塑料) Poly Foam(SnowBox)竹条 Bamboo Batten竹篾 Bamboo Skin狭木条 Batten铜丝 Brass Wire铁丝 Iron Wire铁条 Iron Rod扣箍 Buckle外捆麻绳 Bound with Rope Externally外裹蒲包,加捆铁皮 Bale Matted Iron-band-strapped Outside块装外加塑料袋 Block Covered with Poly Bag每件外套一塑料袋 Each Piece Wrapped in a Poly Bag机器榨包不带包皮 Press Packed Bale without Wrapper机器榨包以铁皮捆扎 Press Packed in Iron Hooped Bale用牢固的纸箱装运 Packed in Strong Carton适合于长途海洋运输 Suitable for Long Distance Ocean Transportation 适合出口海运包装 Packed in Seaworthy Carton for Export全幅卷筒 Full with Rolled on Tube每卷用素包聚乙烯袋装 Each Roll in Plain Poly Bag混色混码 With Assorted Colours Sizes每隔--码烫有边印 With Selvedge Stamped Internally at Every--Yards 用…隔开 Portioned with纸屑 Paper Scrap纸条 Paper Slip净重 Net Weight (Nt.Wt)皮重 Tare Weight包装唛头 Packing Mark包装容积 Packing Capacity包袋件数 Packing Number小心玻璃 Glass易碎物品 Fragile易腐货物 Perishable液体货物 Liquid切勿受潮 Keep Dry/Caution Against Wet怕冷 To Be Protected from Cold怕热 To Be Protected from Heat怕火 Inflammable上部,向上 Top此端向上 This Side Up勿用手钩 Use No Hooks切勿投掷 No Dumping切勿倒置 Keep Upright切勿倾倒 No Turning Over切勿坠落 Do Not Drop/No Dropping切勿平放 Not to Be Laid Flat切勿压挤 Do Not Crush勿放顶上 Do Not Stake on Top放于凉处 Keep Cool/Stow Cool干处保管 Keep in Dry Place勿放湿处 Do Not Stow in Damp Place甲板装运 Keep on Deck装于舱内 Keep in Hold勿近锅炉 Stow Away from Boiler必须平放 Keep Flat/Stow Level怕光 Keep in Dark Place怕压 Not to Be Stow Below Other Cargo 由此吊起 Lift Here挂绳位置 Sling Here重心 Centre of Balance着力点 Point of Strength用滚子搬运 Use Rollers此处打开 Opon Here暗室开启 Open in Dark Room先开顶部 Romove Top First怕火,易燃物 Inflammable氧化物 Oxidizing Material腐蚀品 Corrosive压缩气体 Compressed Gas易燃压缩气体 Inflammable Compressed Gas毒品 Poison爆炸物 Explosive危险品 Hazardous Article放射性物质 Material Radioactive立菱形 Upright Diamond菱形 Diamond Phombus双菱形 Double Diamond内十字菱形 Gross in Diamond四等分菱形 Divided Diamond突角菱形 Diamond with Projecting Ends斜井形 Projecting Diamond内直线菱形 Line in Diamond内三线突角菱形 Three Line in Projecting Diamond三菱形 Three Diamond附耳菱形 Diamond with Looped Ends正方形 Square Box长方形 Rectangle梯形 Echelon Formation平行四边形 Parallelogram井筒形 Intersecting Parallels五边形 Pentagon纸带 Paper Tape纸层 Paper Wool泡沫塑料 Foamed Plastics泡沫橡胶 Foamed Rubber帆布袋内充水 Canvas Bag Filled with Water包内衬薄纸 Lined with Thin Paper内衬锡箔袋 Lined with Frescobag内置充气氧塑料袋 Inner Poly Bag Filled with Oxygen内衬牛皮纸 Lined with Kraft Paper内衬防潮纸、牛皮纸 Lined with Moist Proof Paper &Kraft Paper 铝箔包装 In Aluminium Foil Packing木箱内衬铝箔纸 Lined with Aluminium Foil in the Wooden Case 双层布袋外层上浆 Double Cloth Bag with Outer Bag Starched外置木箱 Covered with Wooded Case外绕铁皮 Bound with Iron Bands Externally胶木盖 Bakelite Cover外绕铁丝二道 Bound with Two Bands 0f Metal Wires Outside标签上标有 Labels Were Marked with纸箱上标有 Cartons Were Marked with包装合格 Proper Packing包装完整 Packing Intact包装完好 Packing Sound正规出口包装 Regular Packing for Export表面状况良好 Apparently in Good Order& Condition包装不妥 Improper Packing包装不固 Insufficiently Packed包装不良 Negligent Packing包装残旧玷污 Packing Stained &Old箱遭水渍 Cartons Wet &Stained外包装受水湿 With Outer Packing Wet包装形状改变 Shape of Packing Distorted散包 Bales Off铁皮失落 Iron Straps Off钉上 Nailed on尺寸不符 Off Size袋子撕破 Bags Torn箱板破 Case Plank Broken单层牛皮纸袋内衬塑编布包装,25公斤/包 Packed in Single Kraft Paper Bag Laminated with PE Wovenbag 25Kgs Net Eash三层牛皮纸袋内加一层塑料袋装,25公斤/包 Packed in 3-ply Kraft Paper Bags with PE Liner,25Kgs/bag牛皮纸袋内压聚乙烯膜包装,25公斤/包 Packed in Kraft Paper Iaminated with Polyethylene Film of 25Kgs Net Each两端加纸条 With a Paper Band at Both Ends木箱装,***以螺栓固定于箱底,箱装完整 Packed inWoodencase,the***was(were)Mounted with Bolts on the Bottom of the Case.Packing Intact.木箱装,箱装箱装运,箱装完好 Packed in Woodencases with Container Shipment.Packing Sound.塑料编织集装袋装,内衬塑料薄膜袋,集装箱装运,每箱20袋 Packed in Plastic Woven Flexible Container,Lined with Plastic Film Bags,Shipped in Container,20Bags for Each.铁桶装,每桶净重190公斤 Packed in Iron Drums and Each Drum Net 190kgs 木箱包装,内装2卷。

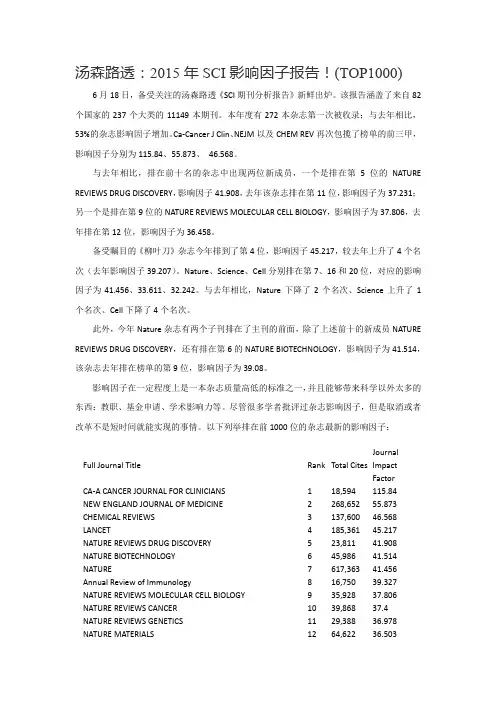

汤森路透:2015年SCI影响因子报告!(TOP1000) 6月18日,备受关注的汤森路透《SCI期刊分析报告》新鲜出炉。

该报告涵盖了来自82个国家的237个大类的11149本期刊。

本年度有272本杂志第一次被收录;与去年相比,53%的杂志影响因子增加。

Ca-Cancer J Clin、NEJM以及CHEM REV再次包揽了榜单的前三甲,影响因子分别为115.84、55.873、46.568。

与去年相比,排在前十名的杂志中出现两位新成员,一个是排在第5位的NATURE REVIEWS DRUG DISCOVERY,影响因子41.908,去年该杂志排在第11位,影响因子为37.231;另一个是排在第9位的NATURE REVIEWS MOLECULAR CELL BIOLOGY,影响因子为37.806,去年排在第12位,影响因子为36.458。

备受瞩目的《柳叶刀》杂志今年排到了第4位,影响因子45.217,较去年上升了4个名次(去年影响因子39.207)。

Nature、Science、Cell分别排在第7、16和20位,对应的影响因子为41.456、33.611、32.242。

与去年相比,Nature下降了2个名次、Science上升了1个名次、Cell下降了4个名次。

此外,今年Nature杂志有两个子刊排在了主刊的前面,除了上述前十的新成员NATURE REVIEWS DRUG DISCOVERY,还有排在第6的NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY,影响因子为41.514,该杂志去年排在榜单的第9位,影响因子为39.08。

影响因子在一定程度上是一本杂志质量高低的标准之一,并且能够带来科学以外太多的东西:教职、基金申请、学术影响力等。

尽管很多学者批评过杂志影响因子,但是取消或者改革不是短时间就能实现的事情。

以下列举排在前1000位的杂志最新的影响因子:Full Journal Title Rank Total Cites Journal Impact FactorCA-A CANCER JOURNAL FOR CLINICIANS 1 18,594 115.84 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 2 268,652 55.873 CHEMICAL REVIEWS 3 137,600 46.568 LANCET 4 185,361 45.217 NATURE REVIEWS DRUG DISCOVERY 5 23,811 41.908 NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY 6 45,986 41.514 NATURE 7 617,363 41.456 Annual Review of Immunology 8 16,750 39.327 NATURE REVIEWS MOLECULAR CELL BIOLOGY 9 35,928 37.806 NATURE REVIEWS CANCER 10 39,868 37.4 NATURE REVIEWS GENETICS 11 29,388 36.978 NATURE MATERIALS 12 64,622 36.503JAMA-JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION 13 126,479 35.289 NATURE REVIEWS IMMUNOLOGY 14 28,938 34.985 Nature Nanotechnology 15 34,387 34.048 SCIENCE 16 557,558 33.611 CHEMICAL SOCIETY REVIEWS 17 81,907 33.383 Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 18 8,462 33.346 Nature Photonics 19 23,499 32.386 CELL 20 201,108 32.242 NATURE METHODS 21 32,342 32.072 NATURE REVIEWS NEUROSCIENCE 22 32,989 31.427 Annual Review of Biochemistry 23 19,927 30.283 REVIEWS OF MODERN PHYSICS 24 39,402 29.604 NATURE GENETICS 25 85,481 29.352 PROGRESS IN MATERIALS SCIENCE 26 8,475 27.417 NATURE MEDICINE 27 62,572 27.363 PHYSIOLOGICAL REVIEWS 28 24,528 27.324 PROGRESS IN POLYMER SCIENCE 29 19,454 26.932 Nature Chemistry 30 16,973 25.325 LANCET ONCOLOGY 31 24,861 24.69 NATURE REVIEWS MICROBIOLOGY 32 18,866 23.574 CANCER CELL 33 27,283 23.523 Annual Review of Plant Biology 34 16,494 23.3 LANCET INFECTIOUS DISEASES 35 13,161 22.433 ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 36 53,349 22.323 Cell Stem Cell 37 17,720 22.268 TRENDS IN COGNITIVE SCIENCES 38 20,396 21.965 TRENDS IN COGNITIVE SCIENCES 38 20,396 21.965 LANCET NEUROLOGY 40 19,384 21.896 Annual Review of Psychology 41 13,101 21.81 Annual Review of Psychology 41 13,101 21.81 IMMUNITY 43 37,232 21.561 ENDOCRINE REVIEWS 44 13,143 21.059 ADVANCES IN PHYSICS 45 5,095 20.833 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES 46 7,562 20.771 BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES 46 7,562 20.771 Energy & Environmental Science 48 36,159 20.523 Nature Physics 49 21,732 20.147 PHYSICS REPORTS-REVIEW SECTION OF PHYSICS LETTERS 50 22,152 20.033 NATURE IMMUNOLOGY 51 35,403 20.004 NATURE CELL BIOLOGY 52 35,734 19.679 Cancer Discovery 53 4,605 19.453 Annual Review of Neuroscience 54 13,226 19.32 Living Reviews in Relativity 55 1,838 19.25 PROGRESS IN ENERGY AND COMBUSTION SCIENCE 56 6,443 19.22Annual Review of Pathology-Mechanisms of Disease 57 3,122 18.75 Annual Review of Physiology 58 8,693 18.51 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY 59 133,258 18.428 Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 60 7,561 18.365 ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE 61 48,356 17.81 ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS REVIEW 62 1,209 17.737 Living Reviews in Solar Physics 63 840 17.636 Cell Metabolism 64 18,502 17.565 ADVANCED MATERIALS 65 128,805 17.493 BMJ-British Medical Journal 66 89,031 17.445 CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY REVIEWS 67 13,982 17.406 ARCHIVES OF INTERNAL MEDICINE 68 38,021 17.333 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS 69 11,630 17.099 ALDRICHIMICA ACTA 70 1,097 17.083 REPORTS ON PROGRESS IN PHYSICS 71 12,463 17.062 Advances in Anatomy Embryology and Cell Biology 72 424 17 Annual Review of Physical Chemistry 73 7,749 16.842 Psychological Science in the Public Interest 74 685 16.833 GASTROENTEROLOGY 75 66,614 16.716 Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 76 9,301 16.66 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY 77 80,926 16.503 TRENDS IN ECOLOGY & EVOLUTION 78 28,654 16.196 Advanced Energy Materials 79 10,129 16.146 NATURE NEUROSCIENCE 80 50,204 16.095 JOURNAL OF PHOTOCHEMISTRY AND PHOTOBIOLOGY81 2,767 16.091 C-PHOTOCHEMISTRY REVIEWSScience Translational Medicine 82 13,031 15.843 EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL SUPPLEMENTS 83 977 15.8 Annual Review of Genetics 84 7,474 15.724 MATERIALS SCIENCE & ENGINEERING R-REPORTS 85 5,625 15.5 Annual Review of Biophysics 86 2,329 15.436 Nature Reviews Neurology 87 4,264 15.358 EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL 88 38,544 15.203 NEURON 89 77,446 15.054 ADVANCED DRUG DELIVERY REVIEWS 90 27,077 15.038 Nano Today 91 4,770 15 REVIEWS OF GEOPHYSICS 92 7,707 14.8 Annual Review of Condensed Matter Physics 93 1,159 14.786 SURFACE SCIENCE REPORTS 94 4,495 14.765 PSYCHOLOGICAL BULLETIN 95 36,794 14.756 PSYCHOLOGICAL BULLETIN 95 36,794 14.756 GUT 97 34,911 14.66 GENOME RESEARCH 98 33,977 14.63 MICROBIOLOGY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY REVIEWS 99 9,777 14.611Light-Science & Applications 100 1,042 14.603 Nature Climate Change 101 5,415 14.547 Nature Climate Change 101 5,415 14.547 MOLECULAR PSYCHIATRY 103 14,510 14.496 ARCHIVES OF GENERAL PSYCHIATRY 104 36,976 14.48 ARCHIVES OF GENERAL PSYCHIATRY 104 36,976 14.48 CIRCULATION 106 155,571 14.43 PLOS MEDICINE 107 18,649 14.429 SYSTEMATIC BIOLOGY 108 13,303 14.387 Annual Review of Marine Science 109 1,976 14.356 World Psychiatry 110 1,914 14.225 World Psychiatry 110 1,914 14.225 Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 112 3,859 14.211 Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 113 4,462 14.18 Materials Today 114 5,339 14.107 MOLECULAR CELL 115 53,786 14.018 EUROPEAN UROLOGY 116 21,495 13.938 Annual Review of Entomology 117 10,553 13.731 NANO LETTERS 118 118,534 13.592 TRENDS IN NEUROSCIENCES 119 19,082 13.555 NATURE STRUCTURAL & MOLECULAR BIOLOGY 120 26,673 13.309 Nature Reviews Endocrinology 121 3,661 13.281 STUDIES IN MYCOLOGY 122 1,660 13.25 FEMS MICROBIOLOGY REVIEWS 123 8,828 13.244 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL INVESTIGATION 124 98,555 13.215 JAMA Internal Medicine 125 2,934 13.116 Nature Chemical Biology 126 14,121 12.996 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF RESPIRATORY AND CRITICAL CARE126 51,902 12.996 MEDICINETRENDS IN PLANT SCIENCE 128 16,637 12.929 Annual Review of Medicine 129 5,612 12.928 ACS Nano 130 78,579 12.881 Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 131 2,980 12.674 Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 131 2,980 12.674 Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 133 3,345 12.61 JNCI-Journal of the National Cancer Institute 134 36,458 12.583 JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL MEDICINE 135 62,917 12.515 CELL RESEARCH 136 9,195 12.413 Alzheimers & Dementia 137 5,371 12.407 Cell Host & Microbe 138 9,206 12.328 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY 139 42,476 12.295 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY 139 42,476 12.295 COORDINATION CHEMISTRY REVIEWS 141 29,127 12.239 Annual Review of Microbiology 142 9,193 12.182JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 143 489,761 12.113 JAMA Psychiatry 144 1,886 12.008 JAMA Psychiatry 144 1,886 12.008 TRENDS IN CELL BIOLOGY 146 11,481 12.007 TRENDS IN BIOTECHNOLOGY 147 11,427 11.958 Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Computational Molecular148 2,014 11.885 ScienceAnnual Review of Materials Research 149 6,481 11.854 BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN METEOROLOGICAL SOCIETY 150 14,786 11.808 ADVANCED FUNCTIONAL MATERIALS 151 51,895 11.805 Autophagy 152 9,457 11.753 Nature Geoscience 153 12,258 11.74 TRENDS IN PHARMACOLOGICAL SCIENCES 154 10,743 11.539 JOURNAL OF ALLERGY AND CLINICAL IMMUNOLOGY 155 38,706 11.476 Nature Communications 156 39,396 11.47 JOURNAL OF HEPATOLOGY 157 27,739 11.336 ANGEWANDTE CHEMIE-INTERNATIONAL EDITION 158 242,023 11.261 Annual Review of Nuclear and Particle Science 159 2,464 11.256 TRENDS IN BIOCHEMICAL SCIENCES 160 15,782 11.227 ASTROPHYSICAL JOURNAL SUPPLEMENT SERIES 161 23,963 11.215 Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics 162 8,177 11.163 HEPATOLOGY 163 58,031 11.055 CIRCULATION RESEARCH 164 47,773 11.019 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF HUMAN GENETICS 165 34,816 10.931 Molecular Systems Biology 166 7,644 10.872 GENOME BIOLOGY 167 22,663 10.81 GENES & DEVELOPMENT 168 59,511 10.798 ACTA NEUROPATHOLOGICA 169 13,098 10.762 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY 170 30,570 10.755 ECOLOGY LETTERS 171 22,999 10.689 Annual Review of Ecology Evolution and Systematics 172 16,942 10.562 BLOOD 173 150,854 10.452 Kidney International Supplements 174 691 10.435 EMBO JOURNAL 175 72,583 10.434 LEUKEMIA 176 20,905 10.431 TRENDS IN IMMUNOLOGY 177 8,931 10.399 ANNALS OF THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES 178 33,400 10.377 Nano Energy 179 2,755 10.325 BIOLOGICAL PSYCHIATRY 180 40,812 10.255 MOLECULAR ASPECTS OF MEDICINE 181 4,050 10.238 HUMAN REPRODUCTION UPDATE 182 6,625 10.165 IMMUNOLOGICAL REVIEWS 183 12,935 10.12 NPG Asia Materials 184 1,145 10.118 Advances in Optics and Photonics 185 880 10.111NATURAL PRODUCT REPORTS 186 8,047 10.107 Lancet Global Health 187 457 10.042 Lancet Global Health 187 457 10.042 PROGRESS IN LIPID RESEARCH 189 4,825 10.015 Advances in Catalysis 190 1,455 10 PROGRESS IN NEUROBIOLOGY 191 11,430 9.992 ANNALS OF NEUROLOGY 192 32,934 9.977 TRENDS IN GENETICS 193 11,210 9.918 Nature Reviews Rheumatology 194 3,335 9.845 JOURNAL OF CELL BIOLOGY 195 71,695 9.834 PHARMACOLOGY & THERAPEUTICS 196 11,806 9.723 DEVELOPMENTAL CELL 197 23,646 9.708 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF198 586,144 9.674 THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICANature Protocols 199 24,589 9.673 BIOLOGICAL REVIEWS 200 7,868 9.67 Lancet Respiratory Medicine 201 925 9.629 Annual Review of Phytopathology 202 6,346 9.62 BRIEFINGS IN BIOINFORMATICS 203 3,679 9.617 JOURNAL OF PINEAL RESEARCH 204 6,906 9.6 CURRENT BIOLOGY 205 48,575 9.571 Perspectives on Psychological Science 206 4,439 9.546 Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 207 2,588 9.469 TRENDS IN MOLECULAR MEDICINE 208 7,186 9.453 TRENDS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY AND METABOLISM 209 6,457 9.392 PLOS BIOLOGY 210 25,729 9.343 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NEPHROLOGY 210 32,059 9.343 PLANT CELL 212 46,901 9.338 SEMINARS IN CANCER BIOLOGY 213 5,094 9.33 CANCER RESEARCH 214 142,659 9.329 eLife 215 3,179 9.322 ACS Catalysis 216 9,046 9.312 ISME Journal 217 10,314 9.302 Chemical Science 218 14,941 9.211 PSYCHOTHERAPY AND PSYCHOSOMATICS 219 2,866 9.196 BRAIN 219 44,379 9.196 PSYCHOTHERAPY AND PSYCHOSOMATICS 219 2,866 9.196 TRENDS IN MICROBIOLOGY 222 9,285 9.186 Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 223 710 9.185 Nature Reviews Cardiology 224 2,647 9.183 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF EPIDEMIOLOGY 225 16,999 9.176 DRUG RESISTANCE UPDATES 226 2,178 9.121 NUCLEIC ACIDS RESEARCH 227 136,883 9.112 MOLECULAR BIOLOGY AND EVOLUTION 228 37,529 9.105EMBO REPORTS 229 11,419 9.055 Physical Review X 230 2,364 9.043 BIOTECHNOLOGY ADVANCES 231 10,390 9.015 Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 232 2,516 8.957 CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES 233 51,710 8.886 Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry 234 1,478 8.833 NEUROSCIENCE AND BIOBEHAVIORAL REVIEWS 235 16,868 8.802 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON FUZZY SYSTEMS 236 8,581 8.746 PROGRESS IN RETINAL AND EYE RESEARCH 237 4,326 8.733 CLINICAL CANCER RESEARCH 238 72,155 8.722 Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 239 7,817 8.679 Annual Review of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering 240 852 8.676 EMBO Molecular Medicine 241 3,363 8.665 CEREBRAL CORTEX 241 26,191 8.665 Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 243 5,801 8.582 Physics of the Dark Universe 244 324 8.571 KIDNEY INTERNATIONAL 245 37,913 8.563 BIOMATERIALS 246 93,432 8.557 Nature Reviews Nephrology 247 2,345 8.542 SLEEP MEDICINE REVIEWS 248 3,919 8.513 INTERNATIONAL MATERIALS REVIEWS 249 2,949 8.5 CATALYSIS REVIEWS-SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING 250 2,986 8.471 CURRENT OPINION IN CELL BIOLOGY 251 13,844 8.467 ONCOGENE 252 64,071 8.459 SCHIZOPHRENIA BULLETIN 253 13,525 8.45 SCHIZOPHRENIA BULLETIN 253 13,525 8.45 MEDICINAL RESEARCH REVIEWS 255 3,542 8.431 DIABETES CARE 256 56,103 8.42 JOURNAL OF AUTOIMMUNITY 257 4,722 8.41 Small 258 26,638 8.368 Annual Review of Nutrition 259 4,699 8.359 Cell Reports 260 6,886 8.358 CHEMISTRY OF MATERIALS 261 86,283 8.354 ANNALS OF SURGERY 262 41,468 8.327 THORAX 263 19,426 8.29 NEUROLOGY 264 76,539 8.286 FISH AND FISHERIES 265 2,526 8.258 GONDWANA RESEARCH 266 7,772 8.235 CELL DEATH AND DIFFERENTIATION 267 16,082 8.184 Geochemical Perspectives 268 60 8.143 DIABETES 269 49,747 8.095 GLOBAL CHANGE BIOLOGY 270 25,578 8.044 Theranostics 271 1,850 8.022 GREEN CHEMISTRY 272 24,614 8.02Laser & Photonics Reviews 273 2,793 8.008 Obesity Reviews 274 7,580 7.995 BRITISH JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY 275 22,557 7.991 BRITISH JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY 275 22,557 7.991 BMC BIOLOGY 277 3,676 7.984 ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PERSPECTIVES 278 34,489 7.977 PSYCHOLOGICAL REVIEW 279 24,097 7.972 PSYCHOLOGICAL REVIEW 279 24,097 7.972 AUTOIMMUNITY REVIEWS 281 6,156 7.933 CLINICAL CHEMISTRY 282 26,550 7.911 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY & THERAPEUTICS 283 15,257 7.903 Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 284 11,534 7.896 EARTH-SCIENCE REVIEWS 285 8,594 7.885 CURRENT OPINION IN PLANT BIOLOGY 286 11,125 7.848 BIOCHIMICA ET BIOPHYSICA ACTA-REVIEWS ON CANCER 287 3,964 7.845 QUARTERLY REVIEWS OF BIOPHYSICS 288 2,345 7.81 ADVANCES IN COLLOID AND INTERFACE SCIENCE 289 8,997 7.776 Academy of Management Annals 290 1,148 7.769 ARTHRITIS AND RHEUMATISM 291 46,886 7.764 Seminars in Immunopathology 292 2,008 7.748 CRITICAL REVIEWS IN BIOCHEMISTRY AND MOLECULAR293 3,088 7.714 BIOLOGYMASS SPECTROMETRY REVIEWS 294 3,572 7.709 JOURNAL OF CONTROLLED RELEASE 295 35,437 7.705 NEW PHYTOLOGIST 296 33,918 7.672 ChemSusChem 297 10,725 7.657 EUROPEAN RESPIRATORY JOURNAL 298 28,687 7.636 CANCER TREATMENT REVIEWS 299 5,719 7.588 PROGRESS IN PHOTOVOLTAICS 300 7,188 7.584 CURRENT OPINION IN GENETICS & DEVELOPMENT 301 8,084 7.574 PLoS Pathogens 302 30,229 7.562 PLoS Genetics 303 33,624 7.528 PHYSICAL REVIEW LETTERS 304 387,635 7.512 Optometry-Journal of the American Optometric Association 305 440 7.5 CHEST 306 45,169 7.483 CURRENT OPINION IN IMMUNOLOGY 307 8,513 7.478 Physics of Life Reviews 307 950 7.478 ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW 309 19,739 7.475 Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters 310 20,052 7.458 Journal of Materials Chemistry A 311 18,266 7.443 FRONTIERS IN ECOLOGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT 312 6,205 7.441 APPLIED CATALYSIS B-ENVIRONMENTAL 313 33,001 7.435 JOURNAL OF PATHOLOGY 314 15,629 7.429 ARCHIVES OF NEUROLOGY 315 20,557 7.419ANTIOXIDANTS & REDOX SIGNALING 316 15,899 7.407 Nanoscale 317 30,888 7.394 Mucosal Immunology 318 3,141 7.374 Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 319 3,937 7.372 Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 319 3,937 7.372 ACTA NUMERICA 321 1,308 7.364 JACC-Cardiovascular Interventions 322 5,235 7.345 PSYCHOLOGICAL METHODS 323 7,617 7.338 GENETICS IN MEDICINE 324 5,496 7.329 BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY 325 2,583 7.316 Journal of Cachexia Sarcopenia and Muscle 326 713 7.315 JAMA Neurology 327 1,672 7.271 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD AND328 17,723 7.26 ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRYJOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF CHILD AND328 17,723 7.26 ADOLESCENT PSYCHIATRYBMC Medicine 330 5,708 7.249 Conservation Letters 331 1,701 7.241PROGRESS IN NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE332 2,127 7.237 SPECTROSCOPYCANCER AND METASTASIS REVIEWS 333 5,649 7.234 JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATIVE DERMATOLOGY 334 25,658 7.216 INTENSIVE CARE MEDICINE 335 16,128 7.214 CURRENT OPINION IN STRUCTURAL BIOLOGY 336 10,897 7.201 JACC-Cardiovascular Imaging 337 4,390 7.188 CRITICAL REVIEWS IN BIOTECHNOLOGY 338 1,735 7.178 JAMA Pediatrics 339 1,184 7.148 CURRENT OPINION IN BIOTECHNOLOGY 340 11,210 7.117 Particle and Fibre Toxicology 341 2,620 7.113PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY342 32,026 7.055 B-BIOLOGICAL SCIENCESNEUROPSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY 343 22,005 7.048 ANNALS OF ONCOLOGY 344 26,807 7.04 FRONTIERS IN NEUROENDOCRINOLOGY 345 3,146 7.037 INTERNATIONAL REVIEWS IN PHYSICAL CHEMISTRY 346 1,553 7.034 Nano Research 347 5,222 7.01 Advances in Organometallic Chemistry 348 791 7 ECOLOGICAL MONOGRAPHS 349 9,207 6.98 PLANT CELL AND ENVIRONMENT 350 17,291 6.96 CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY REVIEW 351 10,297 6.932 JOURNAL OF CATALYSIS 352 39,917 6.921 RADIOLOGY 353 48,908 6.867 PLANT PHYSIOLOGY 354 73,318 6.841 NEUROSCIENTIST 355 3,821 6.837CHEMICAL COMMUNICATIONS 356 160,408 6.834 JOURNAL OF BONE AND MINERAL RESEARCH 357 25,097 6.832 CURRENT OPINION IN CHEMICAL BIOLOGY 358 9,712 6.813 JOURNAL OF NEUROLOGY NEUROSURGERY AND PSYCHIATRY 359 25,650 6.807 IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials 360 2,788 6.806 mBio 361 4,529 6.786 Journal of Molecular Cell Biology 362 1,141 6.771 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL NUTRITION 363 51,613 6.77 METABOLIC ENGINEERING 364 3,929 6.767 Advances in Genetics 365 1,371 6.76 EMERGING INFECTIOUS DISEASES 366 24,477 6.751 ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 367 32,234 6.723 PERSONALITY AND SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY REVIEW 368 3,862 6.692 DRUG DISCOVERY TODAY 369 10,008 6.691 DIABETOLOGIA 370 26,260 6.671 EPIDEMIOLOGIC REVIEWS 371 3,063 6.667 QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ECONOMICS 372 17,890 6.654 JOURNAL OF HEART AND LUNG TRANSPLANTATION 373 8,562 6.65 CHEMISTRY & BIOLOGY 374 11,228 6.645 CURRENT OPINION IN NEUROBIOLOGY 375 12,732 6.628 PROGRESS IN SOLID STATE CHEMISTRY 376 1,635 6.6 MOLECULAR & CELLULAR PROTEOMICS 377 16,299 6.564 Molecular Neurodegeneration 378 2,058 6.563 Methods in Ecology and Evolution 379 2,906 6.554 GLOBAL ECOLOGY AND BIOGEOGRAPHY 380 6,957 6.531 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF HEART FAILURE 381 7,181 6.526 STEM CELLS 382 20,143 6.523 International Journal of Neural Systems 383 1,154 6.507 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON INDUSTRIAL ELECTRONICS 384 27,141 6.498 MOLECULAR ECOLOGY 385 32,977 6.494 HYPERTENSION 386 34,018 6.48 TRAC-TRENDS IN ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 387 9,058 6.472 Annual Review of Public Health 388 4,090 6.469 Annual Review of Public Health 388 4,090 6.469 DEVELOPMENT 390 54,140 6.462 JOURNAL OF CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY 391 15,504 6.459 JOURNAL OF CHILD PSYCHOLOGY AND PSYCHIATRY 391 15,504 6.459 CRITICAL REVIEWS IN SOLID STATE AND MATERIALS SCIENCES 393 1,052 6.45 ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL 394 22,351 6.448 Aging-US 395 2,583 6.432 NEW ASTRONOMY REVIEWS 396 865 6.429 Nanotoxicology 397 2,564 6.411 BIOSENSORS & BIOELECTRONICS 398 30,531 6.409 HUMAN MOLECULAR GENETICS 399 37,440 6.393REMOTE SENSING OF ENVIRONMENT 399 34,609 6.393 ORGANIC LETTERS 401 87,730 6.364 DIABETES OBESITY & METABOLISM 402 6,605 6.36 Oncotarget 403 3,908 6.359 NEUROIMAGE 404 78,028 6.357 JOURNAL OF NEUROSCIENCE 405 173,265 6.344 AGING CELL 406 5,793 6.34 Molecular Plant 407 4,214 6.337 JOURNAL OF MEDICAL GENETICS 408 11,382 6.335 Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms 409 5,799 6.332 CRITICAL CARE MEDICINE 410 33,132 6.312 Annual Review of Food Science and Technology 411 600 6.289 SPACE SCIENCE REVIEWS 412 7,430 6.283 Science Signaling 413 7,211 6.279 Reviews of Physiology Biochemistry and Pharmacology 414 779 6.273 OncoImmunology 415 2,080 6.266 SEMINARS IN CELL & DEVELOPMENTAL BIOLOGY 416 6,404 6.265 MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS 417 9,990 6.262 PSYCHOLOGICAL INQUIRY 418 2,700 6.25 CURRENT OPINION IN SOLID STATE & MATERIALS SCIENCE 419 3,068 6.235 Journal of Crohns & Colitis 420 2,946 6.234 Health Psychology Review 421 462 6.233 MOLECULAR THERAPY 422 13,077 6.227 Advances in Parasitology 423 1,702 6.226 FUNGAL DIVERSITY 424 2,441 6.221 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON SYSTEMS MAN AND CYBERNETICS425 7,317 6.22 PART B-CYBERNETICSCirculation-Cardiovascular Interventions 426 2,718 6.218 JOURNAL OF POWER SOURCES 427 83,937 6.217 CLADISTICS 427 3,643 6.217 MUTATION RESEARCH-REVIEWS IN MUTATION RESEARCH 429 2,740 6.213 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGY & METABOLISM 430 72,536 6.209 TRENDS IN PARASITOLOGY 431 5,287 6.204 ENVIRONMENTAL MICROBIOLOGY 432 16,493 6.201 EPIDEMIOLOGY 433 10,623 6.196 EPIDEMIOLOGY 433 10,623 6.196 CARBON 433 46,718 6.196 MODERN PATHOLOGY 436 11,797 6.187 JOURNAL OF NUCLEAR MEDICINE 437 22,620 6.16 Polymer Reviews 438 1,388 6.156 Nanomedicine-Nanotechnology Biology and Medicine 439 5,381 6.155 OPHTHALMOLOGY 440 29,035 6.135 PHYSICS LETTERS B 441 61,553 6.131 LAB ON A CHIP 442 21,499 6.115JOURNAL OF HIGH ENERGY PHYSICS 443 65,164 6.111 AMERICAN PSYCHOLOGIST 444 17,525 6.1 NUTRITION REVIEWS 445 5,837 6.076 JOURNAL OF MANAGEMENT 446 10,823 6.071 Current Opinion in Virology 447 1,829 6.064 JOURNAL OF INTERNAL MEDICINE 448 8,802 6.063 Biotechnology for Biofuels 449 3,026 6.044 Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 450 43,592 6.032 GLIA 451 11,659 6.031 ALLERGY 452 13,418 6.028 Acta Biomaterialia 453 18,776 6.025 CRITICAL REVIEWS IN MICROBIOLOGY 454 1,838 6.02 Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-RNA 455 1,305 6.019 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON POWER ELECTRONICS 456 21,131 6.008 ARTERIOSCLEROSIS THROMBOSIS AND VASCULAR BIOLOGY 457 32,864 6 JOURNAL OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES 458 44,607 5.997 ASTROPHYSICAL JOURNAL 459 195,795 5.993 ARCHIVES OF TOXICOLOGY 460 6,045 5.98 PLANT JOURNAL 461 38,130 5.972 HUMAN BRAIN MAPPING 462 16,505 5.969 GENETICS 463 44,722 5.963 Advances in Immunology 464 2,270 5.962 CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL 465 12,121 5.959 CARDIOVASCULAR RESEARCH 466 21,783 5.94 PSYCHOLOGICAL MEDICINE 467 19,189 5.938 PSYCHOLOGICAL MEDICINE 467 19,189 5.938 TOBACCO CONTROL 469 5,600 5.933 TOBACCO CONTROL 469 5,600 5.933 JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY-GENERAL 471 8,281 5.929 RENEWABLE & SUSTAINABLE ENERGY REVIEWS 472 21,901 5.901 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF KIDNEY DISEASES 473 19,397 5.9 CURRENT OPINION IN MICROBIOLOGY 473 8,080 5.9 Annual Review of Environment and Resources 475 2,122 5.892 Annual Review of Environment and Resources 475 2,122 5.892 Circulation-Heart Failure 477 3,540 5.891 BRAIN BEHAVIOR AND IMMUNITY 478 8,218 5.889 ANESTHESIOLOGY 479 23,780 5.879 Advances In Atomic Molecular and Optical Physics 480 766 5.875 JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY & NEUROSCIENCE 481 2,491 5.861 JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY & NEUROSCIENCE 481 2,491 5.861 IEEE SIGNAL PROCESSING MAGAZINE 483 5,989 5.852 CURRENT OPINION IN COLLOID & INTERFACE SCIENCE 484 5,702 5.84 HAEMATOLOGICA 485 12,975 5.814 JOURNAL OF COSMOLOGY AND ASTROPARTICLE PHYSICS 486 17,560 5.81CELLULAR AND MOLECULAR LIFE SCIENCES 487 19,985 5.808 MACROMOLECULES 488 101,504 5.8 Advanced Healthcare Materials 489 1,857 5.797 Open Biology 490 833 5.784 IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON PATTERN ANALYSIS AND MACHINE491 29,822 5.781 INTELLIGENCECLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY AND INFECTION 492 11,650 5.768 ACS Macro Letters 493 3,481 5.764 PLANT BIOTECHNOLOGY JOURNAL 494 4,031 5.752 BIOMACROMOLECULES 495 31,769 5.75 CURRENT ISSUES IN MOLECULAR BIOLOGY 495 555 5.75 FREE RADICAL BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE 497 33,783 5.736 CHEMISTRY-A EUROPEAN JOURNAL 498 77,915 5.731 ARCHIVES OF PEDIATRICS & ADOLESCENT MEDICINE 498 9,704 5.731 ALIMENTARY PHARMACOLOGY & THERAPEUTICS 500 16,005 5.727 STROKE 501 58,619 5.723 MEDICINE 501 4,912 5.723 Eurosurveillance 503 6,152 5.722 JOURNAL OF THROMBOSIS AND HAEMOSTASIS 504 14,764 5.72 Stem Cells Translational Medicine 505 1,253 5.709 PROGRESS IN SURFACE SCIENCE 506 1,876 5.696 Nanophotonics 507 301 5.686 MOLECULAR CANCER THERAPEUTICS 508 16,563 5.683 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF TRANSPLANTATION 508 18,092 5.683 MOVEMENT DISORDERS 510 18,803 5.68 CURRENT DIRECTIONS IN PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE 511 6,921 5.678 MRS BULLETIN 512 6,108 5.667 PRECAMBRIAN RESEARCH 513 12,318 5.664 ADVANCED SYNTHESIS & CATALYSIS 514 18,854 5.663 CURRENT OPINION IN LIPIDOLOGY 515 3,864 5.656 Circulation-Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 515 2,725 5.656 ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY 517 105,680 5.636 CANCER LETTERS 518 22,516 5.621 Translational Psychiatry 519 1,919 5.62 Brain Structure & Function 520 2,478 5.618 STRUCTURE 520 13,533 5.618 APPLIED ENERGY 522 23,996 5.613 ACTA PSYCHIATRICA SCANDINAVICA 523 11,769 5.605 ACTA PSYCHIATRICA SCANDINAVICA 523 11,769 5.605 CLINICAL SCIENCE 525 8,820 5.598 HEART 526 14,939 5.595 Scientific Reports 527 22,336 5.578 REVIEWS IN MEDICAL VIROLOGY 528 1,845 5.574 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PLASTICITY 529 7,364 5.567BLOOD REVIEWS 530 1,974 5.565 NEURO-ONCOLOGY 531 5,623 5.562 ENVIRONMENT INTERNATIONAL 532 12,067 5.559 AIDS 533 22,502 5.554 BRITISH JOURNAL OF SURGERY 534 20,540 5.542 Family Business Review 535 1,610 5.528 WATER RESEARCH 535 53,631 5.528 EXPERT OPINION ON INVESTIGATIONAL DRUGS 535 4,461 5.528 JOURNAL OF EXPERIMENTAL BOTANY 538 32,646 5.526 JOURNAL OF ECOLOGY 539 15,745 5.521 Polymer Chemistry 540 10,407 5.52 Cryosphere 541 2,467 5.516 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY 542 18,227 5.498 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY 542 18,227 5.498 Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 542 17,918 5.498 CHEMICAL RECORD 545 1,599 5.492 BREAST CANCER RESEARCH 546 8,885 5.49 DNA RESEARCH 547 2,456 5.477 PEDIATRICS 548 65,154 5.473 ALTEX-Alternatives to Animal Experimentation 549 815 5.467 CLINICAL REVIEWS IN ALLERGY & IMMUNOLOGY 550 1,925 5.463 JOURNAL OF MEDICINAL CHEMISTRY 551 63,060 5.447 CRITICAL REVIEWS IN PLANT SCIENCES 552 2,659 5.442 ANNALS OF FAMILY MEDICINE 553 3,556 5.434 JOURNAL OF CELL SCIENCE 554 42,808 5.432 Catalysis Science & Technology 555 5,419 5.426 JOURNAL OF FINANCE 556 23,535 5.424 IEEE WIRELESS COMMUNICATIONS 557 3,015 5.417 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CANCER 557 23,587 5.417 JOURNALS OF GERONTOLOGY SERIES A-BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES559 13,534 5.416 AND MEDICAL SCIENCESJOURNALS OF GERONTOLOGY SERIES A-BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES559 13,534 5.416 AND MEDICAL SCIENCESBASIC RESEARCH IN CARDIOLOGY 561 3,516 5.414 Molecular Autism 562 577 5.413 Nanomedicine 562 4,318 5.413 Journal of Neuroinflammation 564 5,318 5.408 JOURNAL OF CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW AND METABOLISM 565 15,903 5.407 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF NUCLEAR MEDICINE AND566 11,724 5.383 MOLECULAR IMAGINGBIOSCIENCE 567 13,169 5.377 GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY 568 19,228 5.369 Stem Cell Reports 569 461 5.365 ADDICTION BIOLOGY 570 2,830 5.359CYTOKINE & GROWTH FACTOR REVIEWS 571 4,708 5.357 DRUG METABOLISM REVIEWS 572 2,339 5.356 JOURNAL OF ECONOMIC LITERATURE 573 5,861 5.354 BIOCHIMICA ET BIOPHYSICA ACTA-BIOENERGETICS 574 10,387 5.353 Astrophysical Journal Letters 575 44,743 5.339 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF EPIDEMIOLOGY 575 5,316 5.339 Genome Medicine 577 1,660 5.338 Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 577 3,556 5.338 SOLAR ENERGY MATERIALS AND SOLAR CELLS 579 25,351 5.337 CARCINOGENESIS 580 22,394 5.334 Epigenetics & Chromatin 581 603 5.333 ACS Chemical Biology 582 6,223 5.331 Molecular Oncology 582 2,075 5.331 ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 584 116,924 5.33 Advances in Cancer Research 585 1,956 5.321 Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 586 3,566 5.318 Circulation-Cardiovascular Imaging 587 2,786 5.316 JOURNAL OF ANTIMICROBIAL CHEMOTHERAPY 588 23,616 5.313 MIS QUARTERLY 589 9,600 5.311 MIS QUARTERLY 589 9,600 5.311 CURRENT OPINION IN NEUROLOGY 591 4,789 5.307 PERSOONIA 592 824 5.3 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BIOETHICS 593 1,363 5.288 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BIOETHICS 593 1,363 5.288 Journal of Thoracic Oncology 595 8,883 5.282 JOURNAL OF BONE AND JOINT SURGERY-AMERICAN VOLUME 596 37,434 5.28 JOURNAL OF CONSULTING AND CLINICAL PSYCHOLOGY 597 21,076 5.279 PROCEEDINGS OF THE NUTRITION SOCIETY 598 4,458 5.273 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF EPIDEMIOLOGY 599 35,307 5.23 PAIN 600 31,705 5.213 WILDLIFE MONOGRAPHS 601 664 5.2 Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine 602 2,634 5.199 CRITICAL REVIEWS IN FOOD SCIENCE AND NUTRITION 603 5,935 5.176 OBSTETRICS AND GYNECOLOGY 604 26,836 5.175 SEMINARS IN IMMUNOLOGY 605 3,502 5.17 Advances in Geophysics 606 440 5.167 BIOCHIMICA ET BIOPHYSICA ACTA-MOLECULAR AND CELL607 7,312 5.162 BIOLOGY OF LIPIDSJOURNAL OF ABNORMAL PSYCHOLOGY 608 14,289 5.153 EXPERT REVIEWS IN MOLECULAR MEDICINE 609 1,736 5.152 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGICAL PATHOLOGY 610 18,910 5.145 HUMAN MUTATION 611 11,719 5.144 EXPERT OPINION ON THERAPEUTIC TARGETS 612 3,585 5.139 MOLECULAR NEUROBIOLOGY 613 4,012 5.137。

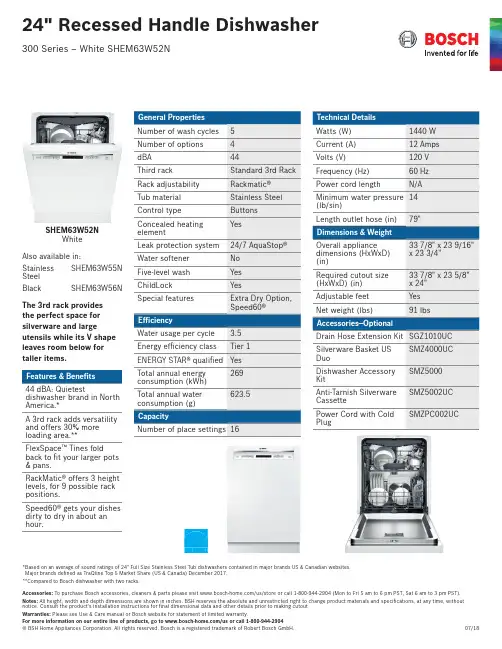

Accessories: To purchase Bosch accessories, cleaners & parts please visit /us/store or call 1-800-944-2904 (Mon to Fri 5 am to 6 pm PST, Sat 6 am to 3 pm PST).SHEM63W52NWhiteAlso available in:Stainless Steel SHEM63W55N BlackSHEM63W56NThe 3rd rack provides the perfect space for silverware and largeutensils while its V shape leaves room below for taller items.44 dBA: Quietestdishwasher brand in North America.*A 3rd rack adds versatility and offers 30% more loading area.**FlexSpace™ Tines foldback to fit your larger pots & pans.RackMatic® offers 3 height levels, for 9 possible rack positions.Speed60® gets your dishes dirty to dry in about anhour.* B ased on an average of sound ratings of 24" Full Size Stainless Steel Tub dishwashers contained in major brands US & Canadian websites. Major brands defined as TraQline Top 5 Market Share (US & Canada) December 2017.**Compared to Bosch dishwasher with two racks.Accessories: To purchase Bosch accessories, cleaners & parts please visit /us/store or call 1-800-944-2904 (Mon to Fri 5 am to 6 pm PST, Sat 6 am to 3 pm PST).Installation DetailsPower cordInstallation DetailsAccessories: To purchase Bosch accessories, cleaners & parts please visit /us/store or call 1-800-944-2904 (Mon to Fri 5 am to 6 pm PST, Sat 6 am to 3 pm PST).。

常用英语n句--设备安装379 Erection of the equipment will be carried out according to the specifications and drawings. 设备安装将按照说明书和图纸进行。

380 All site erection works will be performed by the Buyer under the technical instruction of the Seller.所有的现场安装工作都应在卖方的技术指导下由买方完成。

381 The construction company is fully in charge of the administration of all erection work. 建设公司完全负责全部安装工程的行政管理。

382 Our company cover all construction activities, that is : piling , civil engineering, mechanical erection, piping, electrical,instrumentation, painting and insulation work. 我们公司涉及所有施工活动,包括:打桩、土建工程、机械安装、配管、电气、仪表、油漆和保温绝缘工作。

383 What is the feature of this 学习版er (学习版ing furnace, heating furnace, reactor, mixer, centrifuger, belt-conveyer) ?这台裂解器(裂解炉、加热炉、反应器、搅拌器、离心机、皮带输送机)的特点是什么?384 The spherical tank (gas holder, container) will be shipped in the condition of edge prepared and bent plates.球罐(气柜、容器)将以板加工和弯板的条件发货。

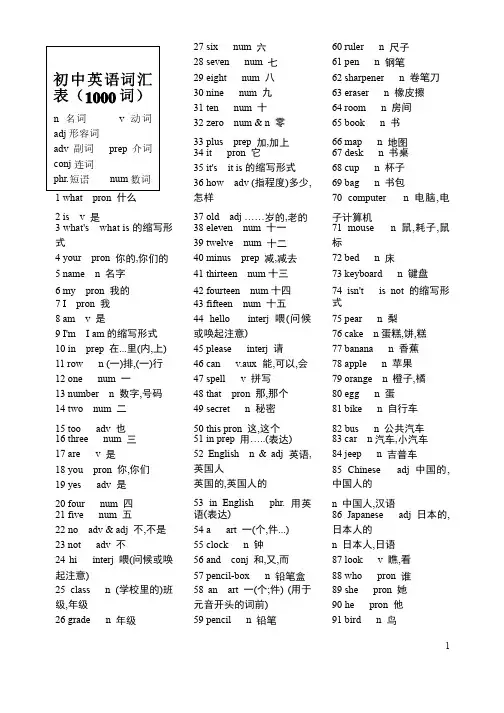

11 what pron 什么2 is v 是3 what's what is 的缩写形式4 your pron 你的,你们的5 name n 名字6 my pron 我的7 I pron 我8 am v 是9 I'm I am 的缩写形式 10 in prep 在...里(内,上) 11 row n (一)排,(一)行 12 one num 一 13 number n 数字,号码 14 two num 二 15 too adv 也 16 three num 三 17 are v 是 18 you pron 你,你们 19 yes adv 是 20 four num 四 21 five num 五 22 no adv & adj 不,不是 23 not adv 不 24 hi interj 喂(问候或唤起注意) 25 class n (学校里的)班级,年级 26 graden 年级 27 sixnum 六 28 seven num 七 29 eight num 八 30 nine num 九 31 ten num 十 32 zero num & n 零 33 plus prep 加,加上 34 it pron 它 35 it's it is 的缩写形式 36 how adv (指程度)多少,怎样37 old adj adj …………岁的,老的 38 eleven num 十一 39 twelve num 十二 40 minus prep 减,减去 41 thirteen num 十三 42 fourteen num 十四 43 fifteen num 十五 44 hello interj 喂(问候或唤起注意)45 please interj 请 46 can v.aux 能,可以,会 47 spell v 拼写 48 that pron 那,那个 49 secret n 秘密 50 this pron 这,这个 51 in prep 用…..…..((表达) 52 English n & adj 英语,英国人英国的,英国人的 53 in English phr. 用英语(表达) 54 a art 一(个,件...) 55 clock n 钟 56 and conj 和,又,而 57 pencil-box n 铅笔盒 58 an art 一(个;件) (用于元音开头的词前) 59 penciln 铅笔 60 rulern 尺子 61 pen n 钢笔 62 sharpener n 卷笔刀 63 eraser n 橡皮擦 64 room n 房间 65 book n 书 66 map n 地图 67 desk n 书桌 68 cup n 杯子 69 bagn 书包 70 computer n 电脑,电子计算机 71 mouse n 鼠,耗子,鼠标72 bed n 床 73 keyboard n 键盘 74 isn't is not 的缩写形式75 pear n 梨 76 cake n 蛋糕,饼,糕 77 banana n 香蕉 78 apple n 苹果 79 orange n 橙子,橘 80 egg n 蛋 81 bike n 自行车 82 bus n 公共汽车 83 car n 汽车,小汽车 84 jeep n 吉普车 85 Chinese adj 中国的,中国人的 n 中国人,汉语 86 Japanese adj 日本的,日本人的n 日本人,日语 87 look v 瞧,看 88 who pron 谁 89 she pron 她 90 he pron 他 91 birdn 鸟 初中英语词汇表(1000词)n 名词 v 动词 adj 形容词形容词 adv 副词副词 prep 介词介词 conj 连词连词 phr.短语短语num 数词数词92 its pron 它的93 do v.aux (构成否定句和疑问句的助动词)94 don't (do not的缩写形式)95 know v知道,懂得96 think v 想,认为97 Mr=mister n 先生(用于姓名前)98 very adv 很,非常99 picture n 图画,照片 100 Mrs n 夫人101 boy n 男孩102 girl n 女孩103 woman n妇女,女人 104 man n 男人,人 105 cat n 猫106 his pron 他的 107 teacher n 教师 108 her pron 她的109 everyone pron 每人,人人110 here adv 这里,这儿 111 today adv & n 今天 112 at prep 在113 school n 学校114 at school phr. 在学校115 sorry adj 对不起,抱歉的116 where adv在哪里 117 home n 家118 at home phr.在家 119 How are you? 你(身体)好吗120 fine adj (身体)好 121 thanks n 谢谢(只用复数)122 OK adv (口语)好,对,不错,可以123 thank v 谢谢124 goodbye interj 再见,再会125 bye interj 再见126 parrot n 鹦鹉127 sister n 姐,妹128 father n 父亲129 mother n 母亲130 box n 盒子,箱子131 excuse v 原谅132 me pron 我133 Here you are给你。

方舟进化生存秘籍代码大全分类整理The Standardization Office was revised on the afternoon of December 13, 2020直接输入:GOD 无敌、取消无敌Fly 飞行模式Walk 取消飞行模式Ghost 穿墙setcheatplayer true 作弊选单开setcheatplayer false 作弊选单关giveengrams 所有制作蓝图解锁settimeofday <time> 改变时间输入PLAYERSONLY指令,冻结所有龙的行动冻结龙之后,来到需要强制驯服的龙的跟前,输入FORCETAME指令后,面前的龙即可以被强制驯服。

giveitemnum 2 1 9 false【龙奶代码】Cheat giveitem"Blueprint'/Game/PrimalEarth/CoreBlueprints/Items/Consumables/BaseBPs/'" 10 1 0滑翔翼cheat giveitem "Blueprint'/Game/Aberration/CoreBlueprints/Items/Armor/'" 1 100 0武器1 Simple Pistol简易手枪2 Assault Rifle 突击步枪3 Rocket Launcher火箭发射器4 Simple Bullet简单子弹5 Bow弓6 Genade手榴弹32 Stone Arrow石箭33 Stone Pick石镐34 Stone Hatchet石斧35 Metal Pick铁镐36 Metal Hatchet铁斧32 Stone Arrow石箭33 Stone Pick石镐34 Stone Hatchet石斧35 Metal Pick铁镐36 Metal Hatchet铁斧37 Torch火把42 Remote Detonator遥控雷管43 C4 Charge C4控制器44 Blood Extraction Syringe采血器45 Blood Pack血包46 Improvised Explosive Device简易爆炸装置57 Spear长矛70 Tranq Arrow麻醉箭71 Pistol Hat Skin手枪皮服108 Sparkpowder火花粉109 Gunpowder火药132 Longneck Rifle长管步枪138 Scope Attachment瞄准镜139 Slingshot弹弓140 Pike铁矛144 Simple Rifle Ammo简易步枪弹药205 Flashlight Attachment手电筒挂件206 Silencer Attachment消音器219 Holo-Scope Attachment全息瞄准镜220 Laser Attachment激光瞄准镜222 Flak Leggings防弹护腿223 Flak Chestpiece防弹衣224 Flak Helmet防弹头盔225 Flak Boots防弹靴226 Flak Gauntlets防弹护手245 Advanced Bullet高级子弹246 Advanced Rifle Bullet高级步枪子弹247 Rocket Propelled Grenade火箭弹267 Shotgun散弹枪268 Simple Shotgun Ammo简易散弹361 连发散弹362 弩376 铁弓377 铁箭434 木质球棒(俗称闷棍)435 毒气手榴弹436 新半自动步枪(自带镜头)451电击棒452手铐衣服15 Water Jar水瓶16 Water Jar (Full) 水瓶(满)17 Cloth Pants布裤18 Cloth Shirt布衬衫19 Cloth Hat布帽20 Cloth Boots布靴21 Cloth Gloves布手套22 Hide pants皮裤23 Hide Shirt皮衬衫24 Hide Hat皮帽25 Hide Boots皮靴26 Hide Gloves皮手套27 Chitin Leggings甲壳护腿28 Chitin Chestpiece甲壳胸甲29 Chitin Helmet甲壳头盔30 Chitin Boots甲壳靴31 Chitin Gauntlets甲壳护手47 Waterskin水袋48 Waterskin(Full) 水袋(满)72 GPS全球定位系统137 Compass指南针187 Parachute降落伞281 Hunter Skin Hat猎人皮帽子283 Spyglass望远镜299 霸王龙头盔300 眼镜305 矿工帽308 恐龙老花镜372 恐龙定位373 恐龙gps378 水壶379 水壶满387 氧气瓶388 潜水眼睛389 脚蹼429 御寒毛皮腿裤,430 御寒毛皮胸甲,431 御寒毛皮帽子432 御寒毛皮鞋子433 御寒毛皮手套437嘟嘟霸王龙面具皮肤446防爆护腿447防爆护胸448防爆护手449防爆靴450防暴头盔材料7 Wood木材8 Stone石头9 Metal金属10 Hide兽皮11 Chitin甲壳73 Flint燧石74 Metal Ingot金属锭75 Thatch茅草76 Fiber纤维77 Charcoal木炭78 Crystal水晶123 Narcotic麻醉剂124 Stimulant兴奋剂142 Obsidian黑曜石158 Argentavis Talon阿根廷巨鹰的爪159 Megalodon Tooth巨齿鲨的牙齿160 Tyrannosaur Arm暴龙的爪161 Sauropod Vertebra雷龙的脊椎162 Oil石油163 Silica Pearls珍珠164 Gasoline汽油166 Polymer聚合物183 Super Test meat超级实验肉184 Flare Gun信号枪216 Chitin/Keratin角质素217 Keratin角蛋白363 绿色364 微黄365 粉366 紫367 白368 淡蓝369 淡黄370 深黄371 彩色蛋挞385 三角龙头骨406~412 各色染料413 洗点水420 洗点水配方424 毛皮房建38 Paintbrush漆刷39 Campfire篝火40 Standing Torch立式火把58 Red Coloring红色染料59 Green Coloring绿色染料60 Blue Coloring蓝色染料61 Yellow Coloring黄色染料62 Purple Coloring紫色染料63 Orange Coloring橙色染料64 Black Coloring黑色染料65 White Coloring白色染料66 Brown Coloring褐色染料67 Cyan Coloring青色染料68 Purple Coloring紫色染料79 Thatch Roof茅草屋顶80 Thatch Door茅草屋的门81 Thatch Foundation茅草地基82 Thatch Wall茅草墙83 Thatch Doorframe茅草屋的门框84 Wooden Catwalk木制小道85 Wooden Ceiling木制天花板86 Wooden Hatchframe木制天窗门框87 Wooden Door木门88 Wooden Foundation木地基89 Wooden Ladder木梯90 Wooden Pillar木支柱91 Wooden Ramp木坡道92 Wooden Trapdoor木制天窗活动门93 Wooden Wall木墙94 Wooden Doorframe木制门框95 Wooden WindowFrame木制窗框96 Wooden Window木窗97 Wooden Sign木制指示牌98 Blueprint: Note蓝图:注释105 Storage Box小存储箱106 Large Storage Box大储物箱107 Mortar and Pestle研磨器皿125 Refining Forge精炼炉126 Smithy工作台127 Compost Bin堆肥箱128 Cooking Pot烹调锅136 Wooden Fence Foundation木篱笆141 Radio无线电143 Dinosaur Gateway木制中型恐龙大门门框145 Summon Broodmother召唤巨型蜘蛛-育母蜘蛛传送门146 Cementing Paste水泥147 Dinosaur Gate木制中型恐龙大门148 Artifact of the Hunter召唤物品149 Artifact of the Pack召唤物品150 Artifact of the Massive召唤物品151 Artifact of the Devious召唤物品152 Artifact of the Clever召唤物品153 Artifact of the Skylord召唤物品154 Artifact of the Devourer召唤物品155 Artifact of the Queen召唤物品156 Artifact of the Strong召唤物品157 Artifact of the Flamekeeper召唤物品165 Electronics电路板167 Metal Catwalk金属小道168 Metal Ceiling金属天花板169 Metal Hatchframe金属天窗门框170 Metal Door金属门171 Metal Fence Foundation金属围栏172 Metal Foundation金属地基173 Behemoth Gate巨型恐龙大门174 Behemoth Gateway巨型恐龙大门门框175 Metal Ladder金属梯子176 Metal Pillar金属立柱177 Metal Ramp金属斜坡178 Metal Trapdoor金属天窗活动门179 Metal Wall金属墙180 Metal Doorframe金属门框181 Metal Windowframe金属窗框182 metal Window金属窗185 Fabricator制作间186 Water Tank储水池188 Air Conditioner空调189 Electrical Generator发电机190 Electrical Outlet电源插座191 Inclined Electrical Cable斜电缆192 Electrical Cable Intersection十字电缆193 Straight Electrical Cable电缆194 Vertical Electrical Cable垂直电缆195 Lamppost灯柱196 Refrigerator冰箱197 Auto Turret自动炮塔198 Remote Keypad远程遥控面板199 Metal Irrigation Pipe – Inclined斜切面金属管道200 Metal Irrigation Pipe – Tap金属水龙头201 Metal Irrigation Pipe – Intersection十字金属管道202 Metal irrigation Pipe – Straight金属直管203 Metal Irrigation Pipe – Tap金属水龙头204 Metal Irrigation Pipe – Vertical垂直金属管道218 Metal Sign金属指示牌221 Wooden Billboard木制告示牌243 Metal Billboard金属告示牌264 Wall Sign木制墙标265 Metal Dinosaur Gateway金属恐龙大门门框266 Metal Dinosaur Gate金属恐龙大门269 Metal Wall Sign金属墙标280 Flag旗帜284 Spider Flag蜘蛛的旗帜295 烘干箱296 铁刺306 保险柜307 木刺309 蓝图柜310 石围墙地基311 石墙312 铁水箱315 石屋顶316 石狗洞顶317 石门318 石地基319 石龙门320 石龙门框321 石柱322 石门框323 石窗框324 独立日烟花326 警报器325 毒气陷阱357 石窗358 石狗洞顶门359 多向路灯360 大烤炉374 白旗375 饲料槽380 镰刀381 石巨兽门框382 石巨兽门383 捕兽夹384 大捕兽夹392 喷漆枪394 斜茅草屋顶395 茅草左墙396 茅草右墙397 斜木屋顶398 木左墙399 木右墙400 斜石屋顶401 石左墙402 石右墙403 斜金属屋顶404 金属左墙405 金属右墙414 木筏421 油画画布438温室墙壁439温室天花板440温室门框441温室门442温室左斜墙443温室右斜墙444温室斜屋顶445温室窗户食物12 Raw Meat生肉13 Spoiled Meat变质肉14 Cooked Meat熟肉51 Bingleberry Soup51 Bingleberry Soup52 Medical Brew医疗补酒53 Energy Brew能量补酒99 Citronal柠檬117 Amarberry黄色浆果118 Azulberry蓝色浆果119 Tintoberry红色浆果120 Mejoberry紫色浆果121 Narcoberry黑色浆果122 Stimberry白色浆果227 Enduro Stew耐力炖汤228 Lazarus Chowder拉撒路杂烩229 Calien Soup卡里安清新汤230 Fria Curry弗里亚咖喱231 Focal Chilli聚神辣椒232 Savoroot土豆233 Longgrass玉米234 Rockarrot胡萝卜250 Rare Flower稀有花朵251 Rare Mushroom稀有蘑菇252 Raw Prime Meat生大腿肉253 Cooked Prime Meat熟大腿肉254 Battle Tartare战斗神丸255 Shadow Steak Saute暗影煎牛排256 Rockwell Recipes: Enduro Stew罗克韦尔食谱:耐力炖汤257 Rockwell Recipes: Lazarus Chowder罗克韦尔食谱:拉撒路杂烩258 Rockwell Recipes: Calien Soup罗克韦尔食谱:卡里安清新汤259 Rockwell Recipes: Fria Curry罗克韦尔食谱:弗里亚咖喱260 Rockwell Recipes: Focal Chilli罗克韦尔食谱:聚神辣椒261 Rockwell Recipes: Battle Tartare罗克韦尔食谱:战斗神丸262 Rockwell Recipes: Shadow Steak Saute罗克韦尔食谱:暗影煎牛排263 Notes on Rockwell Recipes罗克韦尔食谱说明书297 肉干298 腿肉干304 菜单肉干301 菜谱medical brew302 菜谱 energy brew356 菜谱 egg-based kibble453启蒙肉汤饲料327 kibble (ankylo egg)甲龙蛋饲料328 kibble(argentavis egg)阿根廷巨鹰蛋饲料329 kibble(titanboa egg)泰坦巨蟒蛋饲料330 kibble(carno egg)牛龙蛋饲料331 kibble(dilo egg)双棘龙蛋饲料332 kibble(dodo egg)渡渡鸟蛋饲料333 kibble(parasaur egg)副栉龙蛋饲料334 kibble(pteranodon egg无齿翼龙蛋饲料335 (rapator egg)迅猛龙蛋饲料336 (rex egg)霸王龙蛋饲料337 (sarco egg)鳄鱼蛋饲料338 (bronto egg)雷龙蛋饲料339 蝎子蛋饲料340 (araneo egg)蜘蛛蛋饲料341 (spino egg)棘背龙蛋饲料342 (stego egg)剑龙蛋饲料343 (trike egg)三角龙蛋饲料344 龟蛋饲料419 肿头龙蛋饲料配方426 Kibble(Dimorph Egg)双齿翼龙蛋饲料种植49 Berrybush Seeds浆果种子50 Fertilizer肥料54 Dinosaur Feces小型恐龙粪便55 Human Feces人类粪便110 Stone Irrigation Pipe – Intake石灌溉管道入水管111 Stone Irrigation Pipe - Straight石灌溉管道直管112 Stone Irrigation Pipe - Inclined石灌溉管道斜切面管113 Stone Irrigation Pipe - Intersection石灌溉管道十字管114 Stone Irrigation Pipe - Vertical石灌溉管道垂直管115 Stone Irrigation Pipe - Tap石灌溉管道出水龙头116 Amarberry Seed黄色浆果种子130 Small Crop Plot小型种植地133 Citronal Seed柠檬种子134 Specimen Implant样本植入体235 Azulberry Seed蓝色浆果种子236 Tintoberry Seed红色浆果种子237 Mejoberry Seed紫色浆果种子238 Narcoberry Seed黑色浆果种子239 Stimberry Seed白色浆果种子240 Savoroot Seed土豆种子241 Longgrass Seed玉米种子242 Rockarrot Seed胡萝卜种子248 Medium Crop Plot中型种植田249 Large Crop Plot大型种植田270 Amarberry Seed黄色浆果种子271 Azulberry Seed蓝色浆果种子272 Tintoberry Seed红色浆果种子273 Narcoberry Seed黑色浆果种子274 Stimberry Seed白色浆果种子275 Mejoberry Seed紫色浆果种子276 Citronal Seed柠檬种子277 Savaroot Seed土豆种子278 Longgrass Seed玉米种子279 Rockarrot Seed胡萝卜种子286 Medium Dinosaur Feces中型恐龙粪便287 Large Dinosaur Feces大型恐龙粪便386 稀有肥料390 X物种子391 X物种子(即时生长)床41 Hide Sleeping Bag睡袋129 Simple Bed简易床蛋56 Stegosaurus Egg剑龙蛋288 Brontosaurus Egg雷龙蛋289 Parasaur Egg副栉龙蛋290 Raptor Egg迅猛龙蛋291 T-Rex Egg暴龙蛋292 Triceratops Egg三角龙蛋294 Dodo Egg渡渡鸟蛋345 ankylo egg甲龙蛋346 argentavis egg阿根廷巨鹰蛋347 titanboa egg泰坦巨蟒蛋348 carno egg牛龙蛋349 dilo egg双棘龙蛋350 pteranodon egg副栉龙蛋351 sarco egg鳄鱼蛋352 蝎子蛋353 araneo egg蜘蛛蛋354 spino egg棘背龙蛋355 turtle egg龟蛋418 肿头龙蛋425 dimorph egg 双齿翼龙蛋鞍69 Rex Saddle暴龙鞍100 Parasaur Saddle副栉龙鞍101 Raptor Saddle迅猛龙鞍102 Stego Saddle剑龙鞍103 Trike Saddle三角龙鞍104 Pulmonoscorpius Saddle帝王蝎鞍131 Pteranodon Saddle无齿翼龙鞍135 Bronto Saddle雷龙鞍207 Carbonemys Saddle碳龟鞍208 Sarco Saddle帝鳄鞍209 Ankylo Saddle甲龙鞍210 Mammoth Saddle猛犸象鞍211 Megalodon Saddle巨齿鲨鞍212 Sabertooth Saddle剑齿虎鞍213 Carno Saddle牛龙鞍214 Argentavis Saddle阿根廷巨鹰鞍215 Plesiosaur Saddle蛇颈龙鞍282 Rex Stomped Glasses Saddle暴龙眼镜鞍285 Phiomia Saddle渐新象鞍303 spino saddle 棘背龙的鞍313 plesiosaur saddle蛇颈龙的鞍314 海豚鞍393 星尾兽鞍415 雷龙平台鞍417 肿头龙鞍422 巨蜥鞍423 巨蜥鞍平台427 魔鬼蛙的鞍428 大角鹿的鞍。

User manual使用手册目录1 欢迎 61.1 产品特点 62 重要须知 82.1安全 83 您的智能录音笔 9供货范围 9 概览 103.1开/关机 113.2录音 123.3播放 143.4设置模式 163.5状态指示说明173.6 连接电脑 173.7安装下载APP 183.8连接使用 194 APP操作指南 224.1 APP操作录音/实时翻译 224.2 文件 244.3 设置 254.4 同步文件操作 265 技术参数 281 欢迎欢迎来到飞利浦世界!您能选择和购买飞利浦的产品,我们非常高兴。

您可在我们的官方网站上获得飞利浦公司的全方位技术支持,如:使用手册、软件下载、保修信息等。

1.1 产品特点• 高灵敏麦克风;• 智能同步翻译;• 实时分享;• 语音转文本;6 ZH10 ZH开机:长按“能自动打开,分享图标闪,5关机:在开机状态下,长按“”键2~312 ZH3.2录音当你第一次使用录音笔录音时,请注意本节中的录音说明:录音前,请先设置好录音场景以及存储的文件夹,方便您查找;• 每个文件夹能存储 99 个录音文件,总共可容纳 396 个文件。

当一个录音文件夹存满 99 个后,系统会把随后录入的文件自动存储在下一个文件夹中,如果四个文件夹全部录满,录音会提示目录满,此时,请删除部分录音文件或将文件移至电脑后再进行录音。

①录音:长按“”键2~3秒开机,在开机状态下,长按红色“〇”录音键2~3秒进入录音,在录音状态下,短按“〇”键录音暂停,再按一下取消暂停,录音继续,长按“〇”键保存录音。

14 ZH3.3播放本机播放:在语音界面,按“”播放当前的录音文件,在播放的过程中,按“”暂停播放,再按一次取消暂停并继续播放。

可按上下曲键切换文件。

3.3.1音乐播放在主菜单界面,可按上下曲键切换至音乐菜单,按“”键,进去音乐播放界面。

音乐文件需要拷至音乐文件夹才能“播放”。

3.3.2音量调整在播放状态下,按音量键会弹出音量调整界面,再按上下曲键调整音量大小。

联合国A /CN.9/SER.C/DIGEST/CISG/4 大 会Distr.: General8 June 2004Chinese Original: English ____________________________ * 本摘要汇编使用了《贸易法委员会法规的判例法》(《法规的判例法》)摘要中所引用的判决书全文和脚注中所列的其他引文。

这些摘要原意仅作为基本判决提要,可能不反映汇编中表述的所有观点。

建议读者查阅所列法院判决书和仲裁裁决书全文,而不只依靠《法规的判例法》摘要。

V.04-54736联合国国际贸易法委员会贸易法委员会关于《联合国国际货物销售合同公约》判例法摘要汇编*第四条本公约只适用于销售合同的订立和卖方和买方因此种合同而产生的权利和义务。

特别是,本公约除非另有明文规定,与以下事项无关:(a) 合同的效力,或其任何条款的效力,或任何惯例的效力;(b) 合同对所售货物所有权可能产生的影响。

1.第四条第一句列出了本公约的条款优先于国内法适用的一些事项,即合同的订立和双方当事人的权利和义务,1第二句则包含了一个非详尽性的列举,列举了本公约不涉及的事项,即合同的有效性,或其任何条款的有效性,或任何惯例的1 《法规的判例法》判例 241 [法国最高法院,1999年1月5日]。

贸易法委员会关于《销售公约》判例法的摘要有效性以及合同对所售货物所有权可能产生的影响。

本公约未规定第四条第二部分所提到的事项,是因为这会延迟本公约的缔结。

22.本公约不涉及的事项应当根据所适用的一套统一的规则来处理,3或者根据适用的国内法来处理。

4本公约所涉及的事项3.就合同的订立而言,本公约仅仅规范了订立合同的客观要求。

5相反,合同是否有效成立,这一问题则由适用的国内法规范,本公约给出详尽性规则的问题除外6。

因此,订立合同的能力7以及错误的后果,欺诈和胁迫等问题都留待国内法去解决8。

但是,如果一方当事人在所要交付的货物的质量方面犯有错误,或对另一方当事人的清偿能力认识错误,适用的国内法规则要让位于本公约的规定,因为本公约详尽地涉及到这些问题。

UNPACKING INSTRUCTIONSStep 1: C ut all straps located at both front and back of package.Step 2: C ut front panel of box along left and right edges with utility knife. Caution should be used when cutting. Step 3: O pen top 4 panels of box.Step 4: F old front panel down to bottom of the box without tearing any pieces off. You will need to use the front panel in step 6.Step 5:Unlock the 2 visible castors located at the bottom of the sink by flipping the lock up on the caster.Step 6: Roll your sink out of the box using front panel as a ramp.Warning:Do not attempt to lift the unit off skid or use a forklift. Doing this may cause damage to valves underneath unit. I f sink has been unpacked during winter, it m ust climatize to room temperature for 24 hours before usage. When the portable sink is not being used, it m ust be stored at room temperature. Storing the unit in cold temperatures without using a Cold Storage Kit will cause any water to freeze in the lines, water heater and pump. T his will cause damage and will void all applicable warranty. See Cold Storage Instructions for more details.START UP INSTRUCTIONSStep 1: E nsure both freshwater and wastewater drainage valves (located on the bottom left side of the units) are in the closed position.Step 2:Turn the water heater off by turning the temperature dial counterclockwise to the lowest temperature setting. W arning: A lways disconnect unit from supply circuit before opening door. N ever connect water heater to power source unless the hot water tank is full of water.Step 3:Ensure both the heater and pump are securely plugged into the outlet inside the cabinet.Step 4: T urn on both the hot and cold taps to release air through the lines.Step 5: U sing either t he side filling point (Fill location 1) or by removing the hose on the lid (Fill location 2), fill the freshwater tank.Step 6: P lug the sink into a dedicated electrical outlet. The pump will turn on and water will start to pass through the pump and into the heater. This will allow the heater to fill up with water. Note that when the water pressure reaches the faucet, it may create a sputtering noise. This is normal as air is being pushed from the water lines. Step 7: W hen a steady stream of water passes through the faucet and the air bubbles are no longer present, turn the taps off.Step 8:Turn the heater temperature up to your preferred setting. The heater will take approximately 10 minutes to produce hot water.Step 9:Once the wastewater tank is full, drain it by opening the wastewater drainage valve on the bottom of the sink. If drainage access is unavailable, an optional wastewater Drainage Pump is available through Ancaster Food Equipment. See Optional Water Drainage Pump Instructions for more information.DIRECT WASTEWATER HOOKUP TO DRAINIf a sanitary drain is located on the ground near the portable sink, the sink’s wastewater can be routed directly to the drain to avoid manual draining of the water tank. This can be done by following these steps:Step 1: A t a local hardware store, obtain a vinyl hose that is long enough to reach the sanitary drain. Note: This hose must have an inside diameter of ¾” to connect properly.Step 2: O nce the vinyl hose has been purchased, connect the hose to the wastewater drainage valve located on the left side, underneath the portable sink unit.Step 3: T he opposite end of the hose should be secured and should run towards the drain.Step 4: T urn the wastewater drainage valve to the open position and leave it open. As water enters the wastewater tank, it will immediately drain through the hose, towards the designated area.OPTIONAL WATER DRAINAGE PUMP INSTRUCTIONSNo space to drain the sink’s wastewater tank? No worries! Ancaster Food Equipment’s WaterDrainage Pump sucks all the water flowing from the wastewater drainage valve and pumps itthrough a clear PVC tube a llowing users to drain the water wherever is most accessible to them. The water drainage pump is sold separately and is available through Ancaster Food Equipment for $199.00. This is especially useful if the desired drain location is elevated above ground level.Step 1:Hook the end of the wired PVC pipe from the pump to the wastewater valve.Step 2:Place the clear PVC tube in the desired spot to drain b efore you plug i n the pump.Step 3:After adhering the suction cup to the sink or drainage area, it should hold the clear PVC pipe securely in place.Step 4:Open wastewater valve.Step 5: Plug pump in and observe first-hand the water flow through the clear PVC pipe into the desired location. Warning:Ensure pump is u nplugged when the wastewater container is empty so the pump does not run dry. Running the water pump dry will result in damaging the water pump and will void any warranty.DIRECT FRESHWATER HOOKUP TO CITY LINEEach portable sink includes a garden hose adapter attached to the paper towel dispenser. This adapter allows the user to bypass filling the freshwater tank, providing a constant freshwater connection from the city line. This can be done by following these steps:Step 1: E nsure the portable sink is not connected to a power source. Unplug the water pump’s power cord from the GFCI receptacle inside the unit.Step 2: L ocate the flex hose attached to the water heater. Note: The flex hose should have been sticking out of the cabinet on the right side of the unit when delivered.Step 3:Connect the flex hose directly to the city line.Step 4: O pen both taps allowing water to flow freely out. Turn the garden hose water line on. Only cold water will come out. For hot water tank usage, plug the portable sink into a power source.OPTIONAL COLD STORAGE INSTRUCTIONSIn order to keep a portable sink in working condition, it m ust be stored correctly when not in use. This should be done at the end of summer, or early autumn to prepare for winter. Storing the unit in cold temperatures without proper care will cause any water in the lines, water heater and/or pump to freeze. T his will cause damage and will void any applicable warranty. To prevent this from happening, users will need to purchase b oth a Cold Storage Kit sold trough Ancaster Food Equipment for $99.00, a nd an air compressor which can be found at a local hardware store. Both are necessary to move forward with the next steps and neither are included with purchase of the sink.Step 1: Unplug the sink and open both taps.Step 2:Untwist the ¾” steel braided hose from the freshwater tank, ensuring not to lose the gasket. This braided hose can be found in the Cold Storage Kit.Step 3: S crew the ¾” steel braided hose with the gasket onto the Cold Storage tube, also found in the Cold Storage kit.Step 4:Plug the ¼” air adapter into an air compressor. Once plugged in, compressed air will blow water directly out of the heater, pump and lines. As the tank begins to empty, the water will begin to spit out of the hose and into the desired landing location. This is normal and should be no cause for concern.Warning: I t is crucial that the compressor air pressure m ust not exceed 40 PSI.OPTIONAL FOOT PEDAL SETUP & OPERATIONEach portable sink h as the option to operate with a foot pedal to allow the user to leave the taps open in order to avoid touching the faucet handles, and control water flow using just the pedal. T his foot pedal should be ordered and/or purchased separately through Ancaster Food Equipment.Note: This option is n ot for use when connected directly to a garden hose line.Step 1: F ollow steps 1 through 9 of provided S tart-Up Instructions.Step 2:Unplug the sink.Step 3: P lace the foot pedal on the ground near the sink, feeding the attached power cord into the cabinet through the hole in the bottom of the sink.Step 4: Unplug the pump’s power cord from the GFCI receptacle inside the sink cabinet.Step 5: P lug the foot pedal cord into the GFCI receptacle. This is where the pump was o riginally plugged into. Step 6: P lug the pump’s power cord into the Foot Pedal plug.Step 7: Plug the sink back into an outlet.Step 8: T urn taps on and to desired temperature, depressing the pedal by foot to operate water flow.SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONSWhen the faucets are turned off, the water pump will automatically shut off and turn back on when re-opened, unless there are air bubbles in the water line. To correct this, simply run more water until the air bubbles are no longer visible, double-checking that there are no kinks in the water lines.When the freshwater tank is empty, the water pump will draw air bubbles into the system, and the freshwater tank must be refilled. To do this, disconnect the wastewater pump’s power cord from the GFCI electrical outlet located inside the unit. Only then should the user refill the freshwater tank.Do not let the water pump run without water in the freshwater tank. Running the water pump dry will result in damaging the water pump and will v oid any warranty.When refilling the freshwater tank, it is recommended that the wastewater tank is emptied at the same time. The wastewater drainage valve is located just under the unit on the left side. Dispose of the waste water in a sanitary drain.No power? U se the reset button located on the GFCI electrical outlet located in the cabinet. It is important that the receptacle is tested monthly.。

专业英语单词1.bulk mud components storage散装泥浆药品储备罐2.mud return line架空槽3.reserve pit储备罐4.weight indicator指重表5.driller′s console司钻控制台6.accumulator unit储能器组7.choke manifold节流管后汇8.mud-gas separator泥气分离器9.power generating plant发电机组10.conductor pipe 导管11.surface casing表层套管12.intermediate casing技术套管13.production casing生产套管14.pipe racks钻杆架15.cat walk跑道16.pipe ramp斜跑道17.rathole 大鼠洞.口袋18.mouse hole小鼠洞19.tong counter weight吊钳平衡器20.stairways梯子21.gin pole大腿22.rock(cone) bit牙轮钻头23.blade bit刮刀钻头24.serves conduit泥浆通道(罐连接)25.slough=cave in坍塌26.contaminate使污染27.rig up安装28.v-door大门29.lead tong外钳30.back up tong内钳31.slip 卡瓦32.control panel控制板33.electrical magnetic电磁刹车34.auxiliary辅助刹车35.BOP stack防喷器组36.blind盲板37.shear ram剪切闸板38.variable ram变径39.open hole 空井40.nitrogen氮气41.water-bearing含水层42.oil-bearing含油层pay sand生产层43.cutting岩屑44.triplex double acting三缸双作用泵45.gel切力46.woc=wait on cement候凝47.wow=wait on weather等候天气48.consist of组成49.supplement增补、补偿50.tugger气葫芦51.foam泡沫52.one way value=check单向阀53.principle原理54.muddy泥泞的55.fastening钳尾绳56.make a round trip全程起下钻57.wiper trip短起58.dummy trip短起59.consultant顾问bor saver动力滑轮组61.wear off磨损62.wear out磨坏63.IU=internal upset内加厚64.EU=external upset外加厚65.IEU=internal external upset内外加厚66.remove清除67.brake band刹带68.overfull上提阻力69.tight hole缩径70.gauge hole大井径71.washout冲蚀72.hole enlargement井径扩大73.main brake主刹车74.means 方法、手段75.kick井涌76.weight mud重泥浆77.eliminate清除78.effect on对---有影响79.short-sighted近视眼80.far-sighted远视眼81.cyclone旋流器82.lost cone捞牙轮83.weight up mud 加重泥浆84.water loss失水85.filtration loss滤失量86.tricone三牙轮87.wildcat well初探井88.injection well注水井89.in fill well加密井90.highly deviated well大斜度井91.displacement well大位移井92.multiple well分支井93.cluster well丛式井94.appraisal评价井95.flowing well自喷井96.geothermal well地热井97.sidetracked侧钻98.liner钢套99.liner hanger尾管悬挂器100.overlap重叠段101.choke kill(line)放喷管线102.kick井涌103.blowout井喷104.sand trap锥形罐105.percussion顿钻106.artificial lift机械采油107.jack-up rig自升式钻机108.semi submersible半潜式109.stuck pipe 卡钻110.skid撬装式111.ECD=equivalent circulationdensity当量泥浆密度112.NU=nipple up安装113.spot oil注油114.coupling接箍115.rig-down拆卸116.rig-up安装117.SCR可控硅118.guy line绷绳119.drag磨阻120.shaft 传动轴bine组合、联合122.align对齐123.rational合理的124.interchangeable可交换的125.tooth bit铣齿钻头126.insert bit镶齿钻头127.master bushing方瓦128.stabbing board对扣129.tool joint钻杆接头130.drum滚筒131.cat shaft猫头轴132.fiber rope棕绳133.deadline anchor死绳固定器134.reserve pits沉沙池135.finger board支架136.overturning moment力矩137.setback立拄排放138.condition the mud调整处理泥浆139.wellbore井壁140.mud press失水仪141.salinity矿化度142.days off修班143.down fish井下落物144.flow check检查液面145.synthetic mud合成基泥浆146.ester脂基147.explosive炸药148.permeability渗透率149.sticking卡钻150.differential sticking压差卡钻151.packed off stuck沉沙卡钻152.bridge off沉沙卡钻153.wall sticking粘卡154.oil-in-water水包油155.water-in-oil油包水156.drill rate钻速157.solve溶解158.saturated饱和物159.gage hole井壁规则160.tight hole缩径161.swab抽吸压力162.surge pressure激动压力163.hydrostatic head静液子柱压力164.shackle绳卡165.tolerance=endurance允许误差166.trip tank计量罐167.sand tank锥形罐168.set=hard=solidify凝固169.bit balling钻头泥包l铣床the车床172.cast锻造173.make full use充分利用174.reciprocate drillstring(work pipe)活动钻具175.plugging nozzle堵水眼176.unplug nozzle通水眼177.extended nozzle加长水眼178.jet drilling喷射钻井179.big eye jet喷射造斜180.curved jet斜水眼181.take point靶点(坐标)182.hit target中靶183.azimuth=direction方位角184.inclination=holeangle=drift angle井斜角185.BUR=build up rate造斜率186.curvature曲率187.KOP=kick off point造斜点188.hold section稳斜段189.drop section降斜段190.tool face工具面191.dogleg severity狗腿度严重192.high side高边193.low side低边194.trajectory=wall path轨迹195.straight hole drilling打直井196.pumping unit抽油机197.horse head驴头198.ESP=electric submersiblepump电潜泵199.tubing油管200.casing hanger套管挂201.Christmas tree采油树202.surface obstacle地面障碍203.single shot survey单点照相测系斜仪204.multishot survey多点照相测斜205.gyro陀螺206.MWD=measurement whiledrilling随钻测量207.LWD=logging while drilling随钻录井208.water drive水驱209.closure azimuth闭合方位g time迟到时间211.packer封塥器212.down-hole motor井下动力钻具213.induction log感应测井214.nut shell核桃壳215.total loss完全漏失216.piston effect抽吸作用217.squeeze cementing挤水泥218.lost circulation井漏219.drilling program钻井设计220.casing program井深结构221.keyseat键槽222.consultant顾问223.infield内部井224.supplier=vendor供货商225.bidder投标人226.wait on order等待指令227.stiff drill collar assembly刚性钻具组合228.BHA=bottom hole assembly下部钻具组合229.alternating软硬交错230.dip倾角231.crooked-hole formation易斜地层232.pack hole drilling assembly满眼钻具组合233.limber drilling collarassembly光钻铤钻具组合234.hold assembly稳斜钻具组合235.sidertracking侧钻236.sidewall coring井壁取芯237.reamed划眼238.up-reaming(backreaming)倒划眼239.reaming扩眼240.hole operner=reamer扩孔器241.cement plug水泥塞242.hardened凝固243.pendulum钟摆244.keyseat wiper破键器245.back off倒扣246.free point卡点247.jar震击器248.bumper减震器249.chemical cutting化学切割250.jet cutting水力切割251.never run anything in the hole that is not needed不需要的东西切勿入井252.TD=total depth最终井深253.tensile抗拉254.torsion抗扭255.collapse抗外挤256.burst抗内压257.safety factors安全系数258.release stuck pipe解卡259.tight section缩径井段260.washout 井径扩大(冲蚀)261.washed over套铣262.fracture pressure破裂压力263.pore pressure空隙压力264.plastic viscosity塑像265.apparent表观粘度266.filtrate滤液267.offset邻井268.turnkey大包269.remote BOP control远程控制台270.under balance欠平衡271.thief zone漏失层272.pay zone油层273.gypsum石膏274.quartz石英275.apatite磷灰岩276.topaz黄玉277.corundum钢玉278.limestone灰页层279.filtration loss失水280.filter cake泥饼281.coring取芯282.reservoir rock储集岩283.porosity空隙度284.permeability渗透率285.water saturation水饱和度286.core barrel取芯筒287.inner barrel内筒288.outer barrel外筒289.core catcher岩心爪290.core gripper with slip卡瓦式岩心爪291.core gripper with slipcollar卡箍式岩心爪292.core gripper with slipcollar spring卡簧式岩心爪293.core recovery岩心收获率294.core footage取芯进尺295.overshot打捞筒296.tungsten碳化钙297.cobalt钴298.molybdenum钼299.alloy合金pleting the well完井301.DST=drill stem testing中途测试302.perforating射孔303.resistivity电阻率304.SP=self potential自然电位305.acoustic声波306.a suite of logs组合测井307.insulators绝缘体308.conductive导电性309.dolomites白云岩310.radioactive elements放射性元素311.gamma-ray伽玛射线312.neutron中子313.acoustic velocity log=soniclog声速测井314.drift 通径315.(jack)rabbit通径规316.rigid centralizer钢性扶正器317.links吊环318.stick-up转盘面以上的套管长度319.ring gasket密封钢圈320.riser overshot升高短节321.space spool四通322.bell nipple喇叭口323.MD=measure depth测深D=total vertical depth总垂深325.AFF=authorization forexpenditure投资授权书326.take totco survey测斜327.ring测斜座328.shallow gas浅层气329.make short trip短起330.drop totco survey投测331.spacer隔离液332.rig up安装333.float shoe浮鞋334.flange法兰335.diverter分流器336.tag cement at ----m探水泥面在----米337.recover survey tool取出阅读测斜仪nding string联顶节339.mud line hanger泥浆管线悬挂器340.preflush前置液341.wash ports冲洗孔342.ND=nipple down卸掉343.rough cut粗割344.make final细割345.casing head=casing hanger套管头346.DSAF=doable stud adaptorflange双面转换法兰347.MWD=measure while drilling随钻测斜348.LOT=leaking off test破裂压力实验349.pump slug打重泥浆压井口350.make bit trip起钻换钻头351.log as per geologic program按地质设计电测352.BTC=butter threaded coupled具有梯形螺纹带接箍353.float collar 浮箍354.CBU=circulate bottom up循环一周355.build angle增斜356.make wiper trip通井357.pipe ram半封358.LTC=long threaded coupling 长圆扣359.drilling break快钻时360.restivity spike电阻率突变361.geological sample地质取样362.liner钢套363.drop ball投球364.ensure release确保钻杆脱开365.TOL=top of liner尾管顶部366.variable变径的367.scraper刮泥器368.recover出芯369.box core岩心装盒370.service core barrel保养取芯筒371.turbine涡轮372.CBL=cement bond log水泥交接测试373.CET=cement evaluation tool 水泥评价测试仪374.DST=drilling stem testing中途测试375.carbonate碳酸岩376.lower zone下部油层377.TCP=tubing conveyed perforation油管传输射孔378.short flowback短期回流379.initial build up初始压力恢复380.final build up最终压力恢复381.bullhead to kill well强行压井382.reverse out反循环383.open ended光钻杆384.cement retainer水泥桥塞385.x/over=cross配合接头386.make up torque上扣扭距387.IF=internal flush内平式388.tally丈量389.slurry水泥浆390.thickening time稠化时间391.lightly weighted低密度392.well shut-in procedure关井程序y out排好、布局394.safety clamp安全恰瓦395.slowly break circulationwith drilling fluid andmonitor the returns forlosses缓慢开泵循环,并注意观察是否有漏失396.retarder缓凝剂397.accelerator促凝剂398.bump the plug碰压399.bleed the pressure offslowly漫漫放压400.wing valves旁通阀401.grease gun黄油枪402.gate valves轮阀403.nonmagnetic drill collar无磁钻铤404.pony collar短钻铤405.VSP=vertical seismicprofile垂直地震剖面406.remedial directional扭方位407.core points取心井段408.open nozzles不装水眼409.bottom up gas后效410.gas block封气剂411.weighting agent加重剂412.directional correction纠斜413.tendering招标414.high bid中标价格高415.low bid /cheapest bid中标价格低416.standby time待命时间417.lump sum总数418.accessories附件419.misc=miscellaneous杂项420.mud saver防喷盒421.mud reclamation泥浆回收422.purification system净化系统423.drill in钻开油气层424.drill out钻穿水泥塞425.adhesive粘着的426.eccentric bit偏心钻头427.vacuum degasser真空除气器428.walkie-talkie步话机429.angle build up增斜430.angle drop off降斜431.throttle脚踏油门432.stepless speed change无及变速433.breathing apparatus防毒面具434.windward上风面435.formation pressurecoefficient地层压力系数436.double ram type prevent双闸板型防喷器437.up-hole time上返时间438.up-hole velocity上返速度439.upper Kelly cock方钻杆上旋塞440.upper pickup游车上升最高点441.upward annular velocity环空钻井液上返速度442.vapor-proof derrick light井架防爆灯443.thread lock丝扣密封444.thread compound丝扣密封脂。

Molecular Plant • Volume 6 • Number 2 • Pages 396–410 • March 2013RESEARCH ARTICLEThe RdDM Pathway Is Required for Basal Heat Tolerance in Arabidopsis

Olga V. Popova, Huy Q. Dinh, Werner Aufsatz and Claudia Jonak1

GMI-Gregor Mendel Institute of Molecular Plant Biology, Austrian Academy of Sciences, Dr. Bohr-Gasse 3, 1030 Vienna, Austria

ABSTRACT Heat stress affects epigenetic gene silencing in Arabidopsis. To test for a mechanistic involvement of epige-netic regulation in heat-stress responses, we analyzed the heat tolerance of mutants defective in DNA methylation, his-tone modifications, chromatin-remodeling, or siRNA-based silencing pathways. Plants deficient in NRPD2, the common second-largest subunit of RNA polymerases IV and V, and in the Rpd3-type histone deacetylase HDA6 were hypersensi-tive to heat exposure. Microarray analysis demonstrated that NRPD2 and HDA6 have independent roles in transcriptional reprogramming in response to temperature stress. The misexpression of protein-coding genes in nrpd2 mutants recover-ing from heat correlated with defective epigenetic regulation of adjacent transposon remnants which involved the loss of control of heat-stress-induced read-through transcription. We provide evidence that the transcriptional response to temperature stress, at least partially, relies on the integrity of the RNA-dependent DNA methylation pathway.

Key words: heat stress; RNA-directed DNA methylation; transposons; read-through transcription.

INTRODuCTIONPlants frequently encounter unfavorable environmental conditions such as heat, cold, drought, and pathogen infec-tions. Adaptive strategies of plants to cope with stress are complex and depend on the precise and timely regulation of stress-responsive gene networks (Chinnusamy et al., 2007; Larkindale and Vierling, 2008; Cramer et al., 2011; Mittler et al., 2012). In response to stress, genome-wide transcrip-tional reprogramming includes the induction of genes involved in direct stress protection (e.g. osmoprotectants, detoxifying enzymes) and of genes that encode regulatory proteins (e.g. transcription factors, protein kinases), whereas genes involved in growth are generally repressed. However, after a period of stress (e.g. heat), and when environmental conditions are again favorable, plants need to terminate the transcriptional stress response and to reinitiate the develop-mental program in order to successfully recover and resume growth and development.The transcriptional capacity of genes is intimately connected to their epigenetic states (Bonasio et al., 2010; Gibney and Nolan, 2010). Triggered by developmental or environmental cues, genes can adopt alternate epigenetic states, which result in differences of gene expression without changes in the primary DNA sequence (Lukens and Zhan, 2007; Schmitz and Amasino, 2007; Chinnusamy and Zhu, 2009). The induction of these states is associated with modifications of DNA (e.g. cytosine methylation) and histones (e.g. acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation,

ubiquitination), which together modulate chromatin architecture, and hence the accessibility of particular regions of the genome to the transcriptional machinery (Henderson and Jacobsen, 2007; Feng et al., 2010). In plants, chromatin states can be modulated by double-stranded RNA and derived 24 nucleotide (nt) short RNAs in a process called RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) (Huettel et al., 2007; Pikaard et al., 2008; Law and Jacobsen, 2010; Zhang and Zhu, 2011). Briefly, in Arabidopsis, these short RNAs are produced from double-stranded RNA precursors generated by the combined action of the plant-specific DNA-dependent RNA polymerase IV (Pol IV) and RDR2 (RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE 2). DCL3 (DICER-LIKE3) mediates processing of dsRNA to siRNAs, in conjunction with their loading onto AGO4 (ARGONAUTE 4) effector complexes (Li et al., 2006; Pontes et al., 2006). Loaded AGO4, together with other numerous protein factors, subsequently assembles on nascent transcripts produced by

1 To whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail claudia.jonak@gmi.oeaw.ac.at, tel. +43 1 790449850, fax +43 1 790449001.

© The Author 2013. Published by the Molecular Plant Shanghai Editorial Office in association with Oxford University Press on behalf of CSPB and IPPE, SIBS, CAS.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and repro-duction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact journals.permissions@oup.com.