Cultural Sociology and its Trajectory (zulpikar barat)

- 格式:doc

- 大小:84.50 KB

- 文档页数:18

![[转载]3克洛依伯和克拉克洪的《文化:概念和定义批判分析》(1952)](https://uimg.taocdn.com/2700f2e1f80f76c66137ee06eff9aef8941e48b6.webp)

[转载]3克洛依伯和克拉克洪的《⽂化:概念和定义批判分析》(1952)原⽂地址:3克洛依伯和克拉克洪的《⽂化:概念和定义批判分析》(1952)作者:⽂化产业会员美国⼈类学家阿尔弗雷德·克洛依伯(Alfred Kroeber)和克莱德·克拉克洪(Clyde Kluckhohn)在其1952年出版的《⽂化:概念和定义批判分析》(Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions, by Clyde Kluckhohn, A. L. Kroeber, Alfred G. Meyer, Wayne Untereiner, 1952)⼀书中列举了164条(1871-1920年,⽂化仅仅有6种定义,到1951年,⽂化的定义则⾼达164种)不同的⽂化定义。

此书暂⽆中译本,以下为其英⽂版⽬录:C ONTENTSPART I: GENERAL HISTORY OF THE WORD CULTUREWe begin in Part I with a semantic history of the word “culture” and some remarks on the related concept “civilization.”1. Brief survey2. Civilization3. Relation of civilization and culture4. The distinction of civilization from culture in American sociology5. The attempted distinction in Germany6. Phases in the history of the concept of culture in Germany7. Culture as a concept of eighteenth-century general history8. Kant to Hegel9. Analysis of Memm’s use of the word “Cultur”10. The concept of culture in Germany since 185011. “Kultur” and “Schrecklichkeit”12. Danilevsky13. “Culture” in the humanities in England and elsewhere14. Dictionary definitions15. General discussionAddendum: Febvre, on civilisationPART II: DEFINITIONSIn Part II we then list definitions, grouped according to principal conceptual emphasis, though this arrangement tends to have a rough chronological order as well. Comments follow each category of definitions, and Part II concludes with various analytical indices.Group A: DescriptiveBroad definitions with emphasis on enumeration of content: usually influenced by TylorGroup B: HistoricalEmphasis on social heritage or traditionGroup C: NormativeC- I. Emphasis on rule or wayC- II. Emphasis on ideals or values plus behaviorGroup D: PsychologicalD- I. Emphasis on adjustment, on culture as a problem-solving deviceD- II. Emphasis on learningD- III. Emphasis on habitD- IV. Purely psychological definitionsGroup E: StructuralEmphasis on the patterning or organization of cultureGroup F: GeneticF- I. Emphasis on culture as a product or artifactF- II. Emphasis on ideasF- III. Emphasis on symbolsF- IV. Residual category definitionsGroup G: Incomplete DefinitionsIndexes to DefinitionsA: AuthorsB: Conceptual elements in definitionsWords not included in Index BPART III: SOME STATEMENTS ABOUT CULTUREPart III contains statements about culture longer or more discursive than definitions. These are classified, and each class is followed by comment by ourselves.IntroductionGroup a: The Nature of CultureGroup b: The Components of CultureGroup c: Distinctive Properties of CultureGroup d: Culture and PsychologyGroup e: Culture and LanguageGroup f: Relation of Culture to Society, Individuals, Environment, and ArtifactsPART IV: SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONSPart IV consists of our general conclusions.A: SummaryWord and conceptPhilosophy of historyUse of culture in GermanySpread of the concept and resistancesCulture and civilizationCulture as an emergent or levelDefinitions of cultureBefore and after 1920The place of Tylor and Wissler'The course of post-1920 definitionsRank order of elements entering into post-1930 definitionsNumber of elements entering into single definitionsFinal comments on definitionsStatements about cultureB: General Features of CultureIntegrationHistoricityUniformitiesCausalitySignificance and valuesValues and relativityC: ConclusionA final review of the conceptual problemReview of aspects of our own positionAPPENDIX A:Historical Notes on Ideological Aspects of the Concept of Culture in Germany and Russia, by Alfred G. MeyerAPPENDIX B:The Use of the Term Culture in the Soviet Union, by Alfred G. Meyer曹晋彰整理。

巴斯孔塞洛斯的“宇宙种族”思想与墨西哥的文化民族主义韩琦内容提要:20世纪20年代是墨西哥革命之后国家重建的重要时期,作为公共教育部部长的何塞*巴斯孔塞洛斯借助优生学理论批判了种族退化论和实证主义,提出了“宇宙种族”的思想。

他认为,世界种族的加速融合将为一种新类型种族的出现铺平道路,这个新种族即“未来的宇宙种族”,它将通过爱的自然选择把每一个种族的所有更好的V质保留下来。

拉丁美洲的本质是种族和文化的混血,这种混血的趋势是优化,梅斯提索种族是通往“宇宙种族”的桥梁。

他的这种对种族混血的积极评价,为墨西哥人乃至拉丁美洲人找回了民族自信心和自豪感,成为文化民族主义的基石。

同时,他还积极倡导教育改革运动以及音乐和艺术等方面的文艺复兴运动。

他试图通过普及大众教育、传播爱国主义、促进社会平等,通过他的美学、政治和教育理想,引领墨西哥重新建成一个清白的和理想的国家。

他的努力在塑造墨西哥"新人”、创造新的民族认同和国家身份方面发挥了重要作用。

关键词:墨西哥何塞*巴斯孔塞洛斯“宇宙种族”优生学文民族义20世纪20年代和30年代,是墨西哥革命之后的“重建”时期,该国*本文为作者主持的教育部人文社会科学重点研究基地重大课题"独立以来拉丁美洲的社会转型”(19JJD770007)的阶段性成果。

巴斯孔塞洛斯的"宇宙种族”思想与墨西哥的文化民族主义131在经历了严重的政治动荡之后,试图巩固自波菲利奥•迪亚斯政权倒台之后人民斗争的成果!在维护新宪法、实行土地改革、改善劳工待遇、教育改革和政治民主化等方面都需要实施革命的方案。

革命政府需要不断调整和出台新的政策,以应对国内外不断出现的紧急情况,并亟须全国人民团结一致,共同参与国家重建。

在墨西哥的知识和文化领域,20世纪20年代见证了一种热情的民族主义,许多学者、批评家、小说家、诗人、画家和作曲家试图捕捉革命的精神和墨西哥历史的意义。

在这些年里,新一代革命知识分子不仅通过他们的创新能力,而且通过为政府的服务崭露头角。

![2[1].culture_and_communication](https://uimg.taocdn.com/7457892b453610661ed9f47e.webp)

加布里埃尔·塔尔德论文:加布里埃尔·塔尔德的传播思想探析【中文摘要】加布里埃尔·塔尔德(Gabriel Tarde,1843-1904)是法国社会学创始人之一,在社会学、社会心理学、刑事犯罪学、统计学、传播学等方面均具有杰出成就,对后世产生深刻影响。

尽管长期以来人们并没有称塔尔德为传播学家,但是他对“群众”、“公众”、“舆论”、“精英”、“报纸”等传播学领域的许多问题发表了极有见地的论述,他的理论研究为传播学的发展奠定了坚实的基础。

1903年他提出的“模仿理论”对社会学习论、创新扩散论以及意见领袖理论都有重大影响。

虽然塔尔德身居法国社会学的三位创始人之列,可他的思想长期受到遮蔽,世人对他的认识不足,中国学者对他的研究更是处于相对滞后的状态。

本文试图比较全面地梳理塔尔德的主要传播思想,思想来源及对后世的影响。

在此基础上,对塔尔德的传播研究进行客观评析,力争揭示出塔尔德传播思想的独特价值,使人们重视塔尔德传播思想的历史地位和现实意义,全面、深入的理解传播与社会之间的影响。

【英文摘要】Gabriel Tarde was one of the founders of sociology in France. He have)a profound influence on later generations because of his outstanding achievements in sociology, social psychology, criminal offense, statistics, communication and so on.He added the framework of imitate lawinto his theoretical thoughts of communication which was deeply marked the brand of imitation. Although people did not consider Tarde as an expert on communication for a long time, he had made very insightful discussions on many issues...【关键词】加布里埃尔·塔尔德模仿公众与群众舆论精英【英文关键词】Tarde Gabriel Imitation the public and the masses public opinion the elite【目录】加布里埃尔·塔尔德的传播思想探析摘要3-4Abstract4第一章绪论7-16一、研究缘起7二、研究意义7-11(一) 理论意义7-9(二) 现实意义9-11三、文献回顾11-15(一) 社会学领域的研究11-12(二) 传播学领域的研究12-15四、研究方法15-16(一) 关于研究方法的说明15(二) 文献来源15-16第二章加布里埃尔·塔尔德的思想渊源16-24一、塔尔德的生平简述16-18二、塔尔德思想形成的时代背景18-19三、思想冲突19-20四、塔尔德的理论框架20-24(一) 发明21-22(二) 对立22-23(三) 模仿23-24第三章加布里埃尔·塔尔德的传播思想24-33一、模仿律24-27二、传播中的集体行为、意见领袖及公众舆论27-33(一) 传播中的集体行为—公众与群众27-28(二) 社会结构中的意见领袖—精英的起源与功能28-30(三) 大众传播中的公众舆论30-33第四章加布里埃尔·塔尔德的传播思想评析33-47一、塔尔德思想的开拓意义33-42(一) “模仿律”与创新扩散33-36(二) 塔尔德对罗伯特·帕克乃至芝加哥学派的影响36-38(三) “社会结构中的精英”与”意见领袖”38-40(四) 现实影响40-42二、塔尔德思想的遮蔽42-43三、塔尔德思想的局限性43-47参考文献47-50在学期间的研究成果50-51致谢51。

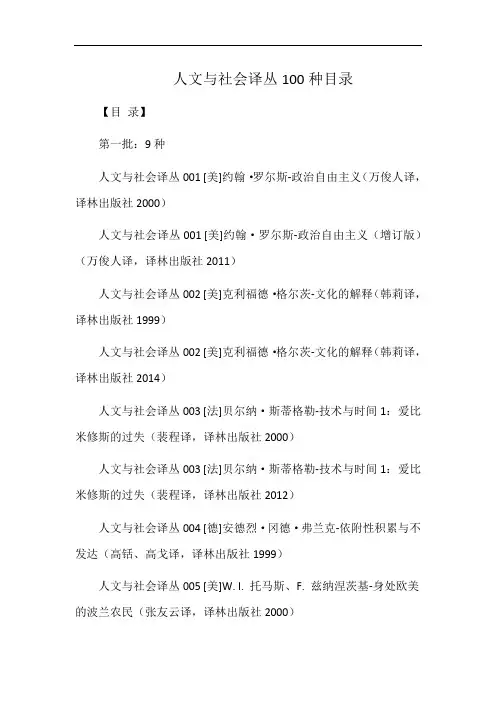

人文与社会译丛100种目录【目录】第一批:9种人文与社会译丛001 [美]约翰·罗尔斯-政治自由主义(万俊人译,译林出版社2000)人文与社会译丛001 [美]约翰·罗尔斯-政治自由主义(增订版)(万俊人译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛002 [美]克利福德·格尔茨-文化的解释(韩莉译,译林出版社1999)人文与社会译丛002 [美]克利福德·格尔茨-文化的解释(韩莉译,译林出版社2014)人文与社会译丛003 [法]贝尔纳·斯蒂格勒-技术与时间1:爱比米修斯的过失(裴程译,译林出版社2000)人文与社会译丛003 [法]贝尔纳·斯蒂格勒-技术与时间1:爱比米修斯的过失(裴程译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛004 [德]安德烈·冈德·弗兰克-依附性积累与不发达(高铦、高戈译,译林出版社1999)人文与社会译丛005 [美]W. I. 托马斯、F. 兹纳涅茨基-身处欧美的波兰农民(张友云译,译林出版社2000)人文与社会译丛006 [英]安东尼·吉登斯-现代性的后果(田禾译,译林出版社2000)人文与社会译丛006 [英]安东尼·吉登斯-现代性的后果(田禾译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛007 [美]迈克·费瑟斯通-消费文化与后现代主义(刘精明译,译林出版社2000)人文与社会译丛008 [英]E.P.汤普森-英国工人阶级的形成(上册)(钱乘旦等译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛008 [英]E.P.汤普森-英国工人阶级的形成(上册)(钱乘旦等译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛008 [英]E.P.汤普森-英国工人阶级的形成(下册)(钱乘旦等译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛008 [英]E.P.汤普森-英国工人阶级的形成(下册)(钱乘旦等译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛009 [美]弗洛里安·兹纳涅茨基-知识人的社会角色(郏斌祥译,译林出版社2000)人文与社会译丛009 [美]弗洛里安·兹纳涅茨基-知识人的社会角色(郏斌祥译,译林出版社2012)第二批:10种人文与社会译丛010 [美]戴安娜·克兰-文化生产:媒体与都市艺术(赵国新译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛010 [美]戴安娜·克兰-文化生产:媒体与都市艺术(赵国新译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛011 [美]R.M.昂格尔-现代社会中的法律(吴玉章、周汉华译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛011 [美]R.M.昂格尔-现代社会中的法律(吴玉章、周汉华译,译林出版社2008)人文与社会译丛012 [德]于尔根·哈贝马斯-后形而上学思想(曹卫东、付德根译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛012 [德]于尔根·哈贝马斯-后形而上学思想(曹卫东、付德根译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛013 [美]迈克尔·J.桑德尔-自由主义与正义的局限(万俊人等译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛013 [美]迈克尔·J.桑德尔-自由主义与正义的局限(万俊人等译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛014 [法]米歇尔·福柯-临床医学的诞生(刘北成译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛014 [法]米歇尔·福柯-临床医学的诞生(刘北成译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛015 [英]詹姆斯·C.斯科特-农民的道义经济学:东南亚的反叛与生存(程立显、刘建译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛015 [英]詹姆斯·C.斯科特-农民的道义经济学:东南亚的反叛与生存(程立显、刘建译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛016 [英]以赛亚·伯林-俄国思想家(彭淮栋译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛016 [英]以赛亚·伯林-俄国思想家(彭淮栋译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛017 [加拿大]查尔斯·泰勒-自我的根源:现代认同的形成(韩震等译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛017 [加拿大]查尔斯·泰勒-自我的根源:现代认同的形成(韩震等译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛018 [美]列奥·施特劳斯-霍布斯的政治哲学(申彤译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛018 [美]列奥·施特劳斯-霍布斯的政治哲学(申彤译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛019 [英]Z.鲍曼-现代性与大TUSHA(杨渝东、史建华译,译林出版社2002)人文与社会译丛019 [英]Z.鲍曼-现代性与大TUSHA(杨渝东、史建华译,译林出版社2011)第三批:10种人文与社会译丛020 [英]杰弗里·C.亚历山大-新功能主义及其后(彭牧、史建华、杨渝东译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛021 [英]约翰·阿克顿-自由史论(胡传胜等译,译林出版社2001)人文与社会译丛021 [英]约翰·阿克顿-自由史论(胡传胜等译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛022 [伊朗]拉明·贾汉贝格鲁編著-伯林谈话录(杨祯钦译,译林出版社2002)人文与社会译丛022 [伊朗]拉明·贾汉贝格鲁編著-伯林谈话录(杨祯钦译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛023 [法]雷蒙·阿隆-阶级斗争:工业社会新讲(周以光译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛024 [美]迈克尔·沃尔泽-正义诸领域:为多元主义与平等一辩(褚松燕等译,译林出版社2002)人文与社会译丛024 [美]迈克尔·沃尔泽-正义诸领域:为多元主义与平等一辩(褚松燕等译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛025 [美]格伦·H.埃尔德-大萧条的孩子们(田禾、马春华译,译林出版社2002)人文与社会译丛026 [加拿大]查尔斯·泰勒-黑格尔(张国清、朱进东译,译林出版社2002)人文与社会译丛026 [加拿大]查尔斯·泰勒-黑格尔(张国清、朱进东译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛027 [英]以赛亚·伯林-反潮流:观念史论文集(冯克利译,译林出版社2002)人文与社会译丛028 [意]加塔诺·莫斯卡-统治阶级(《政治科学原理》)(贾鹤鹏译,译林出版社2002)人文与社会译丛028 [意]加塔诺·莫斯卡-统治阶级(《政治科学原理》)(贾鹤鹏译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛029 [德]于尔根·哈贝马斯-现代性的哲学话语(曹卫东译,译林出版社2004)人文与社会译丛029 [德]于尔根·哈贝马斯-现代性的哲学话语(曹卫东译,译林出版社2011)第四批:10种人文与社会译丛030 [英]以赛亚·伯林-自由论(修订本)(胡传胜译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛030 [英]以赛亚·伯林-自由论(胡传胜译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛031 [德]卡尔·曼海姆-保守主义(李朝晖、牟建君译,译林出版社2002)人文与社会译丛031 [德]卡尔·曼海姆-保守主义(李朝晖、牟建君译,译林出版社2010)人文与社会译丛032 [英]F.A.哈耶克-科学的反革命:理性滥用之研究(修订本)(冯克利译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛032 [英]F.A.哈耶克-科学的反革命:理性滥用之研究(冯克利译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛033 [法]皮埃尔·布迪厄-实践感(蒋梓骅译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛033 [法]皮埃尔·布迪厄-实践感(蒋梓骅译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛034 [德]乌尔里希·贝克-风险社会(何博闻译,译林出版社2004)人文与社会译丛034 [德]乌尔里希·贝克-风险社会(何博闻译,译林出版社2018)人文与社会译丛035 [美]塔尔科特·帕森斯-社会行动的结构(张明德、夏遇南、彭刚译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛035 [美]塔尔科特·帕森斯-社会行动的结构(张明德、夏遇南、彭刚译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛036 [德]诺贝特·埃利亚斯-个体的社会(翟三江、陆兴华译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛036 [德]诺贝特·埃利亚斯-个体的社会(翟三江、陆兴华译,译林出版社2008)人文与社会译丛037 [英]E.霍布斯鲍姆、T.兰格編-传统的发明(顾杭、庞冠群译,译林出版社2004)人文与社会译丛037 [英]E.霍布斯鲍姆、T.兰格編-传统的发明(顾杭、庞冠群译,译林出版社2008)人文与社会译丛038 [美]利奥·施特劳斯-关于马基雅维里的思考(申彤译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛038 [美]利奥·施特劳斯-关于马基雅维里的思考(申彤译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛039 [美]阿拉斯戴尔·麦金太尔-追寻美德:道德理论研究(宋继杰译,译林出版社2003)人文与社会译丛039 [美]阿拉斯戴尔·麦金太尔-追寻美德:道德理论研究(宋继杰译,译林出版社2011)第五批:10种人文与社会译丛040 [英]以赛亚·伯林-现实感:观念及其历史研究(潘荣荣、林茂译,译林出版社2004)人文与社会译丛040 [英]以赛亚·伯林-现实感:观念及其历史研究(潘荣荣、林茂译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛041 [英]以赛亚·伯林-启蒙的时代:十八世纪哲学家(孙尚扬、杨深译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛041 [英]以赛亚·伯林-启蒙的时代:十八世纪哲学家(孙尚扬、杨深译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛042 [美]海登·怀特-元史学:19世纪欧洲的历史想象(陈新译,译林出版社2004)人文与社会译丛042 [美]海登·怀特-元史学:19世纪欧洲的历史想象(陈新译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛043 [英]约翰·B.汤普森-意识形态与现代文化(高铦等译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛043 [英]约翰·B.汤普森-意识形态与现代文化(高铦等译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛044 [加拿大]简·雅各布斯-美国大城市的死与生(金衡山译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛045 [美]罗伯特·K.默顿-社会理论和社会结构(唐少杰、齐心等译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛046 [法]弗兰兹·法农-黑皮肤,白面具(万冰译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛047 [美]格奥尔格·G.伊格尔斯-德国的历史观:从赫尔德到当代历史思想的民族传统(彭刚、顾杭译,译林出版社2006)人文与社会译丛047 [美]格奥尔格·G.伊格尔斯-德国的历史观:从赫尔德到当代历史思想的民族传统(彭刚、顾杭译,译林出版社2014)人文与社会译丛048 [法]弗兰兹·法农-全世界受苦的人(万冰译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛049 [法]雷蒙·阿隆-知识分子的YAPIAN(呂一民、顾杭译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛049 [法]雷蒙·阿隆-知识分子的YAPIAN(呂一民、顾杭译,译林出版社2012)第六批:10种人文与社会译丛050 [美]哈维·C.曼斯菲尔德-驯化君主(冯克利译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛050 [美]哈维·C.曼斯菲尔德-驯化君主(冯克利译,译林出版社2017)人文与社会译丛051 [法]亚历山大·科耶夫-黑格尔导读(姜志辉译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛052 [法]让·波德里亚-象征交换与死亡(车槿山译,译林出版社2006)人文与社会译丛052 [法]让·波德里亚-象征交换与死亡(车槿山译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛053 [英]以赛亚·伯林-自由及其背叛(赵国新译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛053 [英]以赛亚·伯林-自由及其背叛(赵国新译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛054 [英]以赛亚·伯林-启蒙的三个批评者(马寅卯、郑想译,译林出版社2014)人文与社会译丛055 [美]西德尼·塔罗-运动中的力量:社会运动与斗争政治(吴庆宏译,译林出版社2005)人文与社会译丛056 [美]道格·麦克亚当、西德尼·塔罗、查尔斯·蒂利-斗争的动力(李义中、屈平译,译林出版社2006)人文与社会译丛057 [美]玛莎·纳斯鲍姆-善的脆弱性:古希腊悲剧和哲学中的运气与伦理(徐向东、陆萌译,译林出版社2007)人文与社会译丛057 [美]玛莎·纳斯鲍姆-善的脆弱性:古希腊悲剧和哲学中的运气与伦理(徐向东、陆萌译,译林出版社2018)人文与社会译丛058 [美]詹姆斯·C.斯科特-弱者的武器(郑广怀、张敏、何江穗译,译林出版社2007)人文与社会译丛058 [美]詹姆斯·C.斯科特-弱者的武器(郑广怀、张敏、何江穗译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛059 [美]苏珊·斯坦福·弗里德曼-图绘:女性主义与文化交往地理学(陈丽译,译林出版社2014)第七批:11种人文与社会译丛060 [英]雷蒙·威廉斯-现代悲剧(丁尔苏译,译林出版社2007)人文与社会译丛060 [英]雷蒙·威廉斯-现代悲剧(丁尔苏译,译林出版社2017)人文与社会译丛061 [美]汉娜·阿伦特-论革命(陈周旺译,译林出版社2007)人文与社会译丛061 [美]汉娜·阿伦特-论革命(陈周旺译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛062 [美]艾伦·布卢姆-美国精神的封闭(战旭英译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛063 [英]以赛亚·伯林-浪漫主义的根源(吕梁、洪丽娟、孙易译,译林出版社2007)人文与社会译丛063 [英]以赛亚·伯林-浪漫主义的根源(吕梁、洪丽娟、孙易译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛064 [英]以赛亚·伯林-扭曲的人性之材(岳秀坤译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛065 [印度]帕尔塔·查特吉-民族主义思想与殖民地世界:一种衍生的话语(范慕尤、杨曦译,译林出版社2007)人文与社会译丛066 [法]达尼洛·马尔图切利-现代性社会学:二十世纪的历程(姜志辉译,译林出版社2007)人文与社会译丛067 [英]理查德·J.伯恩斯坦-社会政治理论的重构(黄瑞祺译,译林出版社2008)人文与社会译丛068 [美]埃里克·沃格林-以色列与启示(秩序与历史卷一)(霍伟岸、叶颖译,译林出版社2010)人文与社会译丛069 [美]埃里克·沃格林-城邦的世界(秩序与历史卷二)(陈周旺译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛070 [德]弗里德里希·梅尼克-历史主义的兴起(陆月宏译,译林出版社2010)第八批:10种人文与社会译丛071 [英]威廉·贝纳特、彼得·科茨-环境与历史:美国和南非驯化自然的比较(包茂红译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛072 [英]基思·托马斯-人类与自然世界:1500-1800年间英国观念的变化(宋丽丽译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛073 [德]恩斯特·卡西勒-卢梭问题(王春华译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛074 [美]哈维·C.曼斯菲尔德-男性气概(刘玮译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛075 [美]理查德·塔克-战争与和平的权利(罗炯等译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛076 [美]威廉·多姆霍夫-谁统治美国:权力政治和社会变迁(吕鹏、闻翔译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛077 健[法]马赛尔·德吕勒-健康与社会:健康问题的社会塑造(王鲲译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛078 [德]托马斯·A.斯勒扎克-读柏拉图(程炜译,译林出版社2009)人文与社会译丛079 [英]以赛亚·伯林-苏联的心灵:共产主义时代的俄国文化(潘永强、刘北成译,译林出版社2010)人文与社会译丛080 [英]以赛亚·伯林-个人印象(林振义、王洁译,译林出版社2013)第九批:10种人文与社会译丛081 [法]贝尔纳·斯蒂格勒-技术与时间2:迷失方向(赵和平、印螺译,译林出版社2010)人文与社会译丛082 [英]查尔斯·蒂利、西德尼·塔罗-抗争政治(李义中译,译林出版社2010)人文与社会译丛083 [英]唐纳德·温奇-亚当·斯密的政治学(褚平译,译林出版社2010)人文与社会译丛084 [美]斯维特兰娜·博伊姆-怀旧的未来(杨德友译,译林出版社2010)人文与社会译丛085 [丹麦]埃丝特·博斯拉普-妇女在经济发展中的角色(陈慧平译,译林出版社2010)人文与社会译丛086 [英]温迪·J.达比-风景与认同:英国民族与阶级地理(张箭飞、赵红英译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛087 [美]汉娜·阿伦特-过去与未来之间(王寅丽、张立立译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛088 [美]丹尼尔·T.罗杰斯-大西洋的跨越(吴万伟译,译林出版社2011)人文与社会译丛089 [法]吕克·博尔坦斯基、夏娃·希亚佩洛-资本主义的新精神(高铦译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛090 [美]本尼迪克特·安德森-比较的幽灵:民族主义、东南亚与世界(甘会斌译,译林出版社2012)第十批:10种人文与社会译丛091 [美]伊丽莎白·科尔伯特-灾异手记:人类、自然和气候变化(何恬译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛092 [法]贝尔纳·斯蒂格勒-技术与时间3.电影的时间与存在之痛的问题(方尔平译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛093 [英]S.H.里格比-马克思主义与历史学:一种批判性的研究(吴英译,译林出版社2012)人文与社会译丛094 [英]保罗·威利斯-学做工:工人阶级子弟为何继承父业(秘舒、凌旻华译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛095 [美]理查德·塔克-哲学与治术:1572—1651(韩潮译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛096 [美]夸梅·安东尼·阿皮亚-认同伦理学(张容南译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛097 [英]西蒙·沙玛-风景与记忆(胡淑陈、冯樨译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛098 [英]J.G.A.波考克-马基雅维里时刻:佛罗伦萨政治思想和大西洋共和主义传统(冯克利、傅乾译,译林出版社2013)人文与社会译丛099 [英]以赛亚·伯林、[波兰]贝阿塔·波兰诺夫斯卡—塞古尔斯卡-未完的对话(杨德友译,译林出版社2014)人文与社会译丛100 [印度]佳亚特里·斯皮瓦克-后殖民理性批判:正在消失的当下的历史(严蓓雯译,译林出版社2014)第十一批:10种人文与社会译丛101 [加拿大]查尔斯·泰勒-现代社会想象(林曼红译,译林出版社2014)人文与社会译丛102 [美]埃里克·沃格林-柏拉图与亚里士多德(秩序与历史卷三)(刘曙辉译,译林出版社2014)人文与社会译丛103 [法]路易·迪蒙-论个体主义:人类学视野中的现代意识形态(桂裕芳译,译林出版社2014)人文与社会译丛104 [美]理查德·J.伯恩斯坦-根本恶(王钦、朱康译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛105 [美]德鲁·吉尔平·福斯特-这受难的国度:死亡与美国内战(孙宏哲、张聚国译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛106 [美]莎伦·R.克劳斯-公民的激情:道德情感与民主商议(谭安奎译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛107 [美]米尔顿·M.戈登-美国生活中的同化:种族、宗教和族源的角色(马戎译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛108 [美]W.J.T.米切尔编著-风景与权力(杨丽、万信琼译,译林出版社2014)人文与社会译丛109 [美]斯蒂芬·达沃尔-第二人称观点:道德、尊重与责任(章晟译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛110 [英]法拉梅兹·达伯霍瓦拉-性的起源:第一次性革命的历史(杨朗译,译林出版社2015)第十二批:10种(缺113)人文与社会译丛111 [法]雅克琳娜·德·罗米伊-希腊民主的问题(高煜译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛112 [英]詹姆斯·格里芬-论人权(徐向东、刘明译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛113 [英]特伦斯·埃尔文-柏拉图的伦理学(陈玮,刘玮译,译林出版社2021)【缺】人文与社会译丛114 [美]莎伦·R.克劳斯-自由主义与荣誉(林垚译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛115 [法]罗杰·夏蒂埃-法国大革命的文化起源(洪庆明译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛116 [美]保罗·博格西昂-对知识的恐惧:反相对主义和建构主义(刘鹏博译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛117 [英]罗伯特·沃迪-修辞术的诞生:高尔吉亚、柏拉图及其传人(何博超译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛118 [荷兰]弗兰克·安克斯密特-历史表现中的意义、真理和指称(周建漳译,译林出版社2015)人文与社会译丛119 [美]埃里克·沃格林-天下时代(秩序与历史卷四)(叶颖译,译林出版社2018)人文与社会译丛120 [美]埃里克·沃格林-求索秩序(秩序与历史卷五)(徐志跃译,译林出版社2018)第十三批:10种(缺130)人文与社会译丛121 [新西兰]罗莎琳德·赫斯特豪斯-美德伦理学(李义天译,译林出版社2016)人文与社会译丛122 [美]迈克尔·弗雷泽-同情的启蒙:18世纪与当代的正义和道德情感(胡靖译,译林出版社2016)人文与社会译丛123 [美]通差·威尼差恭-图绘暹罗:一部国家地缘机体的历史(袁剑译,译林出版社2016)人文与社会译丛124 [新西兰]理查德·乔伊斯-道德的演化(刘鹏博、黄素珍译,译林出版社2017)人文与社会译丛125 [美]彼得·诺维克-DTS与集体记忆(王志华译,译林出版社2019)人文与社会译丛126 [美]玛丽·路易斯·普拉特-帝国之眼:旅行书写与文化互化(方杰、方宸译,译林出版社2017)人文与社会译丛127 [美]唐纳德·沃斯特-帝国之河:水、干旱与美国西部的成长(侯深译,译林出版社2018)人文与社会译丛128 [美]M.斯洛特-从道德到美德(周亮译,译林出版社2017)人文与社会译丛129 [美]M.斯洛特-源自动机的道德(韩辰错译,译林出版社2020)人文与社会译丛130 [美]托马斯·希恩-理解海德格尔:范式的转变(邓定译,译林出版社2022)【缺】第十四批:10种(缺:135-137)人文与社会译丛131 [美]G.R.F.费拉里-城邦与灵魂:费拉里《理想国》论集(刘玮编译,译林出版社2017)人文与社会译丛132 [美]彼得·C·考威尔-人民主权与德国宪法危机(曹晗蓉、虞维华译,译林出版社2017)人文与社会译丛133 [英]基思·托马斯-16和17世纪英格兰大众信仰研究(芮传明、梅剑华译,译林出版社2019)人文与社会译丛134 [英]安东尼·D.史密斯-民族认同(王娟译,译林出版社2018)人文与社会译丛135 [英]乔治·莱文-世俗主义之乐:我们当下如何生活(赵元译,译林出版社2019)【缺】人文与社会译丛136 国王或人民(未出)人文与社会译丛137 [美]德克·佩里布姆-自由意志、能动性与生命的意义(张可译,译林出版社2022)【缺】人文与社会译丛138 [英]乔治·克劳德-自由与多元论:以赛亚·伯林思想研究(惠春寿、李哲罕译,译林出版社2018)人文与社会译丛139 [美]理查德·J.伯恩斯-BAOLI:思无所限(李元来译,译林出版社2018)人文与社会译丛140 [美]爱德华·希尔斯-中心与边缘:宏观社会学论集(李元来译,译林出版社2019)第十五批:10种自足的世俗社会【缺】历史与记忆【缺】媒体、国家与民族【缺】道德错误理论【缺】废墟上的未来【缺】为历史而战【缺】语言动物(未出)我们中的我【缺】人文学科与公共生活【缺】美国生活中的反智主义【缺】第十六批:10种关怀伦理与移情【缺】形象与象征【缺】艾希曼审判(未出)现代主义观念论(未出)文化绝望的政治学【缺】作为文化现实的未来(未出)一种思想及其时代(未出)人类的领土性(未出)理想的暴政(未出)。

lado跨文化的语言学书

《跨文化的语言学》是美国语言学家拉多(Robert Lado)在1957年出版的著作,他认为在外语学习环境中,学习者广泛依赖已经掌握的母语,倾向于将母语的语言形式、意义和与母语相联系的文化迁移到外语学习中来。

这本书以结构主义语法为理论框架,系统阐述了语言对比的理论、方法和步骤,影响深远。

拉多认为,在二语习得过程中,学习者会把母语的特征迁移到目的语中,因此对两种语言及其文化进行系统对比,可以预测和描写可能引起和不会引起困难的地方。

《跨文化的语言学》是语言学领域的重要著作,对跨文化语言学的发展和应用产生了深远的影响。

文明•文明一般指有人居住,有一定的经济文化的地区,是一种社会发展水平较高的有文化的状态。

文明一词源于拉丁文civis,意思是城市的居民,其本身就有城市化和城市形成的含义。

包括民族意识、技术水准、礼仪规范、宗教思想、风俗习惯以及科学知识的发展等等。

文明往往与野蛮相对应,表明社会的进步程度,西方一些国家和地区进入资本主义社会以后,比较多地使用文明这个概念。

文化•英国人类学家爱德华¡¤泰勒在1871年提出:–文化是一个复合的整体,包括知识、信仰、艺术、道德、法律、习俗以及作为一个社会成员的人所习得的其他一切能力和习惯。

文化•人的本质就是劳作,劳作的目的就是创造符号,创造符号就是为了表达人生的意义。

也就是说,¡°文化是人类创造的符号表意系统。

¡±¡ª¡ª【德】卡西尔•文化就是由一个又一个符号系统组成的,每一个民族都有它自己的符号表意系统。

在这个符号系统下面还有很多大大小小的亚系统。

这样就组成了一种文化形态。

•开始,上帝就给了每个民族一只陶杯,从这个杯中,人们饮入了他们的生活。

•——迪格尔印第安人箴言龙应台:文化是什么?•它是随便一个人迎面走来,他的举手投足,他的一颦一笑,他的整体气质。

他走过一棵树,树枝低垂,他是随手把枝折断丢弃,还是弯身而过?一只满身是癣的流浪狗走近他,他是怜悯地避开,还是一脚踢过去?电梯门打开,他是谦抑地让人,还是霸道地把别人挤开?一个盲人和他并肩路口,绿灯亮了,他会搀那盲者一把吗?他与别人如何擦身而过?他如何低头系上自己松了的鞋带?他怎么从卖菜的小贩手里接过找来的零钱?•文化其实体现在一个人如何对待他人、对待自己、如何对待自己所处的自然环境。

在一个文化厚实深沉的社会里,人懂得尊重自己——他不苟且,因为不苟且所以有品位;人懂得尊重别人——他不霸道,因为不霸道所以有道德;人懂得尊重自然——他不掠夺,因为不掠夺所以有永续的智能。

《布迪厄的文化资本理论》

《文化资本》是法国著名社会学家、哲学家、结构主义大师布迪厄的一部论述当代人类精神危机及其出路和未来走向的经典性作品,也是第二次世界大战以后西方社会科学领域中最具影响力的学术著作之一。

书中通过“生活实践”与“结构观念”双重批判模式,试图建立关于个体的话语实践与象征行为的关系理论,在当下信息革命和全球经济一体化背景下重新审视被工业革命所创造出来的那些物质财富的分配、再生产及整合问题,并指导我们如何应对由此而引发的现存人类社会秩序及伦理道德面临着空前挑战的时刻。

culture and anarchy主要内容

《Culture and Anarchy》是英国文化评论家马修·阿诺德于1869年发表的一篇重要文集。

这篇文集主要探讨了文化和无政府的关系,并提出了他关于文化和社会的一些重要思想。

阿诺德在文集中认为,文化的重要性在于它能够提供一种超越个体欲望的理想,使人们能够追求真善美。

他批评了工业化和商业化对社会文化造成的负面影响,主张通过培养人们的文化素养,培养他们的思辨能力和审美品味来改善社会。

文集中,阿诺德首次提出了“无政府”的概念,他认为政府只关注社会的物质利益,而忽视了精神和文化的发展。

他主张要建立一种无政府状态,让人们能够自由地追求自己的文化发展和个人完善。

他认为,通过培养人们的文化素养,人们可以发展出更高尚的思想和追求,从而实现社会的和谐与进步。

阿诺德还在文集中论述了“高雅文化”和“大众文化”的区别。

他认为,高雅文化是那些追求真善美的精英文化,而大众文化则是那些低俗的、迎合群众口味的文化产品。

他批评大众文化的泛滥和低俗化,认为它对社会的精神发展造成了负面影响。

他主张要加强高雅文化的普及,提倡人们去追求更高尚的艺术和文化。

《Culture and Anarchy》这篇文集在当时引起了广泛的讨论和争议,也对后来的文化研究和文化哲学产生了深远的影响。

阿诺德对文化和社会的关系的思考,为后来的文化研究提供了重要的思想基础。

他的观点也对后来的文化政策和教育改革产生了一定的影响,引起了人们对文化和教育的重视。

在如今的社会,尽管我们生活在信息爆炸的时代,但仍然有必要关注文化的发展与提升,以实现个人和社会的和谐与进步。

文化研究:两种范式(1980)斯图亚特·霍尔(Stuart Hall)孟登迎译严肃的、富有批判性的学术工作(intellectual work)没有“绝对的开端”,也鲜有不间断的连续性。

无论是思想史(History of Ideas)钟爱的对于“传统”的无限展开,还是阿尔都塞主义者(原文为Althussereans,疑为Althusserians之误——译注)偏爱的将思想(Thought)标注为“正确”或“错误”要素的“认识论断裂”的绝对论,都是如此。

相反,我们看到的是一种凌乱但带有显著特征的发展不均衡性。

重要的是那些有重大意义的断裂——陈旧的思路在此处被打断,陈旧的思想格局(constellations)被替代,而围绕一套不同的前提和主题,新旧两方面的各种因素被重新组合起来。

一个问题架构(problematic)的变化,明显转变了所提问题的本质、提问题的方式和问题可能获得充分回答的方式。

理论视角上的这些转变,不但反映出内在的学术劳动所产生的结果,而且反映出真实的历史发展和变化被纳入思想的方式及其为思想提供的存在条件——并不确保思想的“正确”,而为思想提供最根本的倾向。

正是由于思想与反映在社会思想范畴当中的历史现实之间的这种复杂的接合(articulation)以及“权力”与“知识”之间持续的辩证法(continuous dialectic),才使得这些断裂具有了记载价值。

文化研究作为一种独特的问题架构,兴起于20世纪50年代中叶那一时期。

当然,与文化研究相关的一些具体的问题,已经不是第一次被提上桌面了。

事实正好相反。

两本有助于考察这一新领域的著作——霍加特(Hoggart)的《文化素养的用途》(Uses of Literacy)和雷蒙·威廉斯的《文化与社会》——都是以不同方式(在某种程度上)重新探讨这些问题的成果。

霍加特的书参考了“文化论战”的内容,始终坚持那些有关“大众社会”的论断以及那种认同利维斯(Leavis)和《细读》(Scrutiny)的研究传统。

《文化社会学》教学大纲课程名称:文化社会学英文名称:Culture and Sociology Study课程代码:011501 课程类别:专业选修课学分学时数:2学分36学时适用专业:汉语言文学、文秘教育、对外汉语、编辑出版学制订人:徐赣丽修订日期:2007年3月10日审核人:韦世柏审核日期:2007年3月15日审订人:莫其逊审订日期:2007年3月20日一、课程的性质和目的(一)课程性质本课属于大学本科多学科公共选修课。

开设本课旨在在于提高大学生素质,拓宽专业知识面;同时也为有相关研究兴趣,毕业后准备继续在此方向深造或者从事相关领域工作的同学铺垫道路,培养他们的研究热情,引导他们对社会文化现象做有效的探索研究。

(二)课程目的通过本课程的学习,使学生能够系统掌握基本概念、方法,达到如下目标:1.通过学习,掌握文化研究的相关概念和主要理论问题。

2.理解文化社会学的研究类别、当前主要流行文化现象。

3.学会用社会文化学的主要理论分析解释身边的文化现象。

二、教学内容、重(难)点、教学要求及学时分配第1章绪论(讲授3学时)简述文化社会学产生的背景、课程的主要内容、关键性概念,以及开课目的和学习要求。

重点:介绍本课的研究对象和关注内容。

难点:如何厘清文化社会学与社会学、文化人类学之间的关系,准确把握各自的研究范畴和侧重点。

第2章文化的生态系统(讲授4学时)对相关概念作学科界定,主要对陆地、河流、村落等各类文化生态环境进行全面介绍,对城市文化的多变量关系进行解说。

重点:界定相关概念。

难点:学生理解文化生态与自然生态的联系与区别。

第3章文化的时空系统(讲授4学时)介绍文化层、文化丛、文化圈、文化区、文化模式等概念和存在形态。

结合大家熟悉的文化现象做理论分析。

重点:介绍文化模式等常用概念。

难点:应用这些概念去分析社会文化现象。

第4章文化的社会系统(讲授4学时)综合讲解血族、民族、阶级、阶层与文化的关系和研究角度,以及主文化、亚文化、反文化,特别是校园文化现象。

Rediscovering Culture: Cultural Sociology and its Trajectory Zulpikar Barat Introduction C. Wright Mills, one of the well-known American sociologists of the twentieth century, had once argued that social world requires sociological imagination, and a fully developed sociological imagination requires a deep analysis of culture (1959). For many of the most important social theorists of the twentieth century, the study of society has been carried out only through a full attention of the problem of culture. An attentive reader can realize this fact in the works of many key social theorists from Emile Durkheim (1965) to Jeffery Alexander (1990) including Max Weber (1930a), George Simmel (2001), Antonio Gramsci (1971), Theodor Adorno(1972 [2001]), Raymond Williams (1977[2001]), Pierre Bourdieu(1977,1984), Clifford Geertz (1973), Michael Foucault (1965, 1977), Mary Douglas (1966), Victor Turner (1969), Daniel Bell (1977[1996]) and Ann Swidler (1986).

Defining Culture “The most significant intellectual movements of the last three decades … have placed cultural analysis at the center of human and literary disciplines” (Seidman, 1990: 235). However, despite the importance of culture in social sciences and humanities, it has seemed to be both challenging and trivial to define this concept in a proper way. Because, according to Raymond Williams, “culture is one of the two or three most complicated words in the English language….because it has now come to be used for important concepts in several distinct intellectual disciplines and in several distinct systems of thought” (1976: 76-77). Those who write about culture mean very different things by the term, analyzing culture in alternative theories full of different, controversial concepts and approaches. While investigating the concept of culture, some scholars focus on the difference between culture and society; some emphasize the internal differentiations of culture: high culture versus mass culture, and material versus symbolic culture (Hall, Neitz and Battani 2003). The general debates around cultural analysis today make it impossible to work out an ironclad definition. While reading the important authors on my reading list, I have perceived that many scholars seem to advocate their own standpoints at the cost of some other aspects of culture.

Although defining culture seems challenging, it is still necessary to identify the nature of culture. Classical sociologists had explained culture in different ways. For example, Marx’s notion of ideology (1972); Durkheim’s ideas about ritual, symbol, and the sacred (1965); Weber’s studies of how subjective meanings direct action (1930a) are still essential for research in cultural sociology. Among these three founders of sociology, Durkheim most powerfully theorized culture seeing it as collective representation (1965; also Alexander 1990; Hall, Neitz and Battani 2003; Smith and Riley 2009). For Weber, culture, like “switchman”, determines “the track along which action has been pushed by the dynamic of interest” (1946: 280). William’s important chapter entitled “The Analysis of Culture” in the Long Revolution coordinated three different definitions of culture; these are the “ideal”, the “documentary”, and the “social” (1961). Ideal culture is the process of discovery within particular periods and societies, of values which have timeless or general human applicability. “Documentary” culture is the record of distinctive cultural achievements, in intellectual and imaginative work of all kinds. Social culture is entire way of life, as it is expressed, not just through artistic monuments, but through social institutions and practice of all kinds (1961: 57-58). William’s definition has still been influential in cultural analysis since he attempted to define culture in the completeness.

Geertz’s definition of culture is also very influential. Clifford Geertz defined culture as “historically transmitted pattern of meanings embodied in symbols, a system of inherited conceptions expressed in symbolic forms by means of which men communicate, perpetuate, and develop their knowledge and attitude towards life” (1973: 89). Geertz’s famous definition can be seen as an idealist approach to culture. Because, like Durkheim (1965) and some other cultural anthropologists such as Turner (1969), he saw symbols, rituals and ideas as the theoretically important aspect of culture. Douglas defined culture as “standardized values of culture” (1966: 39). However, Marxist scholars reject this kind of position and link the most social forces to the process of economics and politics driven more by calculations of self-interest than by meanings. For Marxists, limiting culture to ideas and beliefs downplay the role of other social forces such as power and oppression (Hall, Neitz and Battani 2003).