Research Article

Feasibility and efficiency of concurrent chemo-radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients

Imene Essaidi, Dalenda Hentati, Chiraz Nasr, Lotfi Kochbati, Mongi Maalej

Radio-Oncology Department Salah Azaiz Cancer Institute, boulevard du 9-Avril, 1006 Tunis, Tunisia

Citation: Essaidi I, Hentati D, Nasr C, Kochbati L, Maalej M. Feasibility and efficiency of concurrent chemo-

radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients. J Nasopharyng Carcinoma, 2015, 1(21): e21. doi:10.15383/jnpc.21.

Competing interests:The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Conflict of interest: None.

Copyright:2014 By the Editorial Department of Journal of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. This is an open-access article

distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution,

and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract:

Purpose: To evaluate the feasibility and efficiency of concurrent chemo-radiotherapy (CCRT) in nasopharyngeal

carcinoma (NPC) patients. Patients and Methods: We reviewed data of 33 non-metastatic NPC patients who had

been treated with CCRT between January 2004 and December 2006.The Median age of patients was 41 year-old

and the male/female ratio was 3.According to the 2002 TNM staging system, T3-T4 locally advanced tumors and

N2-N3 nodal status rates were 67% and 46%, respectively. All patients had undifferentiated carcinoma and received

conventional fractionated 2D conventional radiotherapy (RT)with a total dose of 70-74 Gyand concurrent weekly

intravenous cisplatin (40 mg/m2). Results: The acute toxicities were all manageable. Grade 3-4 mucositis and skin

reaction were seen in 6 patients (18%). RT interruption for a week occurred in 1 patient because of a Grade 3

dysphagia. All patients finished their planned RT. Four patients (12%) refused to complete the concurrent

chemotherapy (CT) and 5 other patients (15%) did not receive the planned cycles of CT because of renal and/or

hematologic toxicities. After a median follow-up of 58 months, 6 patients (18%) developed loco-regional relapse

associated with distant metastasis in 4 cases (12%), and 6 patients (18%) developed distant metastases alone. Five-

year overall survival and disease-free survival rates were 70 and 63%, respectively. A univariate analysis for

prognostic factors was also performed. Overall survive was affected by Stage T4, Stage N3, age >40 years, and

cycles of CT ≤ 5.Patients who received more than 5 cycles of cisplatin had also significantly better disease free

survival and metastasis free survival. Conclusion: The results of our study have shown that CCRT for loco

regionally advanced NPC is both feasible and effective, with acceptable toxic effects. On univariate analysis, the

age >40 years, Stage T4, Stage N3, and cycles of CT ≤ 5 had a significantly poor outcome.

Keyword s: chemo-radiotherapy; nasopharyngeal carcinoma; feasibility; efficiency; toxicities

BACKGROUND

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is distinct from other malignancies in the head and neck with respect to its epidemiology, pathology, clinical presentation and response to treatment [1, 2]. This neoplasm has a notable ethnic and geographic distribution with a high prevalence in Southeast Asian and North African

populations. It is relatively frequent in Tunisia with incidence rates of 3.4/ 100.000 population in males and 1.6/ 100.000 population in females [3]. NPC ishighlyradiosensitive.Although early-stage NPC is highly radiocurable, the cure rate with RT alone for locoregionally advanced NPC is low [4-6]. Because NPC is a chemosensitive tumor, CT added to RT in various manners should be a method to improve survival rates [7-17]. Since the early 1990s, more than 15 randomized clinical trials and 4 meta-analyses have been published on the use of induction, concurrent and adjuvant CT in the treatment of locoregionally advanced NPC [6-22].The predominant finding of these studies is a survival advantage associated with the use ofCCRTwith or without adjuvant CT (ACT)over RT alone.Since then, CCRT with or without ACT has become the standard treatment modality for patients with advanced NPC, although the rate of acute toxicities was significant especially when ACT was prescribed.

The aim of this retrospective study is to evaluate the feasibility and efficiencyof CCRT in locoregionally advanced NPC patients. PATIENTS AND METHODS

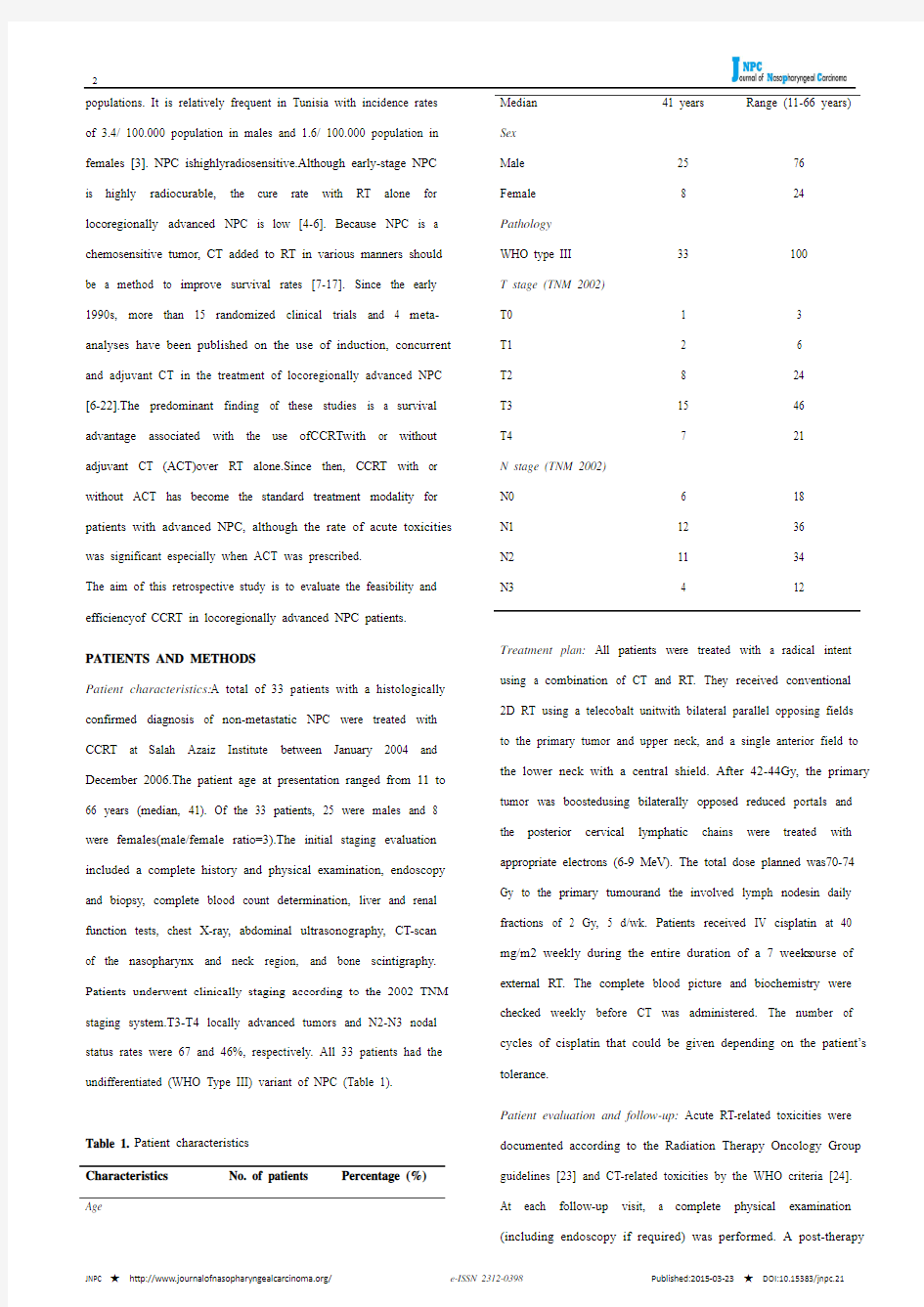

Patient characteristics:A total of 33 patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of non-metastatic NPC were treated with CCRT at Salah Azaiz Institute between January 2004 and December 2006.The patient age at presentation ranged from 11 to 66 years (median, 41). Of the 33 patients, 25 were males and 8 were females(male/female ratio=3).The initial staging evaluation included a complete history and physical examination, endoscopy and biopsy, complete blood count determination, liver and renal function tests, chest X-ray, abdominal ultrasonography, CT-scan of the nasopharynx and neck region, and bone scintigraphy. Patients underwent clinically staging according to the 2002 TNM staging system.T3-T4 locally advanced tumors and N2-N3 nodal status rates were 67 and 46%, respectively. All 33 patients had the undifferentiated (WHO Type III) variant of NPC (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics

Characteristics No. of patients Percentage (%) Age Median 41 years Range (11-66 years) Sex

Male

Female

25

8

76

24 Pathology

WHO type III 33 100

T stage (TNM 2002)

T0

T1

T2

T3

T4

1

2

8

15

7

3

6

24

46

21

N stage (TNM 2002)

N0

N1

N2

N3

6

12

11

4

18

36

34

12

Treatment plan: All patients were treated with a radical intent using a combination of CT and RT. They received conventional 2D RT using a telecobalt unitwith bilateral parallel opposing fields to the primary tumor and upper neck, and a single anterior field to the lower neck with a central shield. After 42-44Gy, the primary tumor was boostedusing bilaterally opposed reduced portals and the posterior cervical lymphatic chains were treated with appropriate electrons (6-9 MeV). The total dose planned was70-74 Gy to the primary tumourand the involved lymph nodesin daily fractions of 2 Gy, 5 d/wk. Patients received IV cisplatin at 40 mg/m2 weekly during the entire duration of a 7 weeks course of external RT. The complete blood picture and biochemistry were checked weekly before CT was administered. The number of cycles of cisplatin that could be given depending on the patient’s tolerance.

Patient evaluation and follow-up: Acute RT-related toxicities were documented according to the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group guidelines [23] and CT-related toxicities by the WHO criteria [24]. At each follow-up visit, a complete physical examination (including endoscopy if required) was performed. A post-therapy

CT scan or MRI of head and neck was obtained for all patients at 3 months after treatment.

Statistical methods: Study endpoints include acute toxicities, overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), loco-regional relapse-free survival (LRRFS) and metastasis relapse-free survival (MRFS). All survivals were calculated from the date of histologically confirmed diagnosis to the date of the observed endpoints or to the date of the last follow-up. Survival endpoints were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariateanalyse was performed for evaluation of the prognostic factors. The Log-rank test was used to compare the curves and p-values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. RESULTS

Toxicity and Compliance: The acute toxicities were all reversible and acceptable. The major side effects were mucositis (97%), skin reaction (94%), nausea and vomiting (76%), dysphagia (51%), and

leukopenia (45%). Most of these side effects were Grade 1-2.

Severemucositis and skin reaction (Grade 3-4) were seen in 6

patients (18%). RT interruption for a week occurred in 1 case

because of a Grade 3 dysphagia. Renal function impairment was

found in 4 cases (12%). All the 33 patients included in this study

finished their planned RT. The median number of cycle of

cisplatin administrated was 5 cycles (range, 2-7 cycles). Four-teen

patients (42%) received more than 5 cycles of cisplatin.

Fourpatients (12%) refused to complete the concurrent CT, while 5 other patients (15%) did not receive the planned cycles of CT because of renal and/or hematologic toxicities (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Acute toxicities Acute toxicities

Grade 1-2 (%) Grade 3 (%) Grade 4 (%)

Mucositis 26 (79%) 5 (15%) 1 (3%) Skin reaction 25 (76%) 4 (12%) 2 (6%) Dysphagia 16 (48%) 1 (3%) - Vomiting 21 (64%) 4 (12%) - Leukopenia 13 (39%) 2 (6%) - Anemia

6 (18%) 1 (3%) - Thrombocytopenia 1 (3%)

- -

Renal impairment 4 (12%)

Table 3. Compliancetotreatment Cycles of cisplatin No. of patients

Percentage (%)

> 5 cycles

14

42

Events and survival: After a median follow-up of 58 months

(range, 3-94 months), 6 patients (18%) developed loco-regional

relapse associated with distant metastasis in 4 cases (12%), and 6

patients (18%) developed distant metastases alone. Five-year

overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), loco-regional

relapse-free survival (LRRFS) and metastasis relapse-free survival

(MRFS) rates were 70, 63, 80, and 68%, respectively (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Overall survival (OS), Disease-Free Survival (DFS), Loco-regional Relapse-free Survival (LRRFS) and Metastasis Relapse-Free Survival (MRFS).

Prognostic factors: On univariate analysis, the age >40 years, Stage T4, Stage N3, and cycles of CT ≤ 5 had a statistically

significant pejorative impact

on OS(Table

4

and Fig.2). On the other hand, Stage T4 had a statistically significant influence on

LRRFS, Stage N3had a statistically significant influence on MRFS and patients who received more than 5 cycles of cisplatin had significantly better DFSand MRFS than those who received less than or equal to 5 cycles of CT.

Table 4. Prognostic factors for clinical outcome.

Prognosticfactors OS DFS LRRFS MRFS

5-y (%) p 5-y (%) p 5-y (%) P 5-y (%) P

Age

≤ 40 years > 40 years 88

50

0.018

88

44

0.003

94

65

0.046

94

37

0.002

T stage

T0T1T2a T2bT3

T4 80

81

28

0.026

80

70

29

0.085

100

90

34

0.005

80

70

57

0.619

N stage

N0N1 N2

N3 82

67

25

0.028

74

58

25

0.03

88

73

67

0.491

79

67

25

0.018

Cycles of cysplatin

> 5 cycles ≤ 5 cycles 87

53

0.033 87

39

0.007 87

72

0.31 87

49

0.002 Figure 2. Overall survival (OS) stratified by prognostic factors: Age, T stage, N stage, and cycles of CT.

DISCUSSION

NPC is highly radiosensitive andchemosensitive, and an excellent disease control can be achieved using combined modality chemoradiation even in patients with locally advanced disease [25]. The American Intergroup 0099 study, using both concurrent cisplatin and RT followed by ACT with cisplatin and fluorouracil (FU) was the first randomized trial to show a survival benefit with CCRT.Its outcome established the treatment standard in the United States as standard of care for locally advanced NPC [7].Afterward, even in Asian countries where NPC is prevalent, the treatment efficacy of CCRT with or without ACT was confirmed in many clinical studies. Since then, we conclude that CCRT with or without ACT is also applicable to patients in endemic areas and should be standard of practice in locally advanced disease [8-10]. The overall magnitude of benefit of CCRT has been previously reported in the Meta-analysis of Chemotherapy in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (MAC-NPC) study [19]. This analysis demonstrated that CT led to asignificant benefit in overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). The effect was most significant for the concurrent group. Combined modality treatment using concurrent cisplatin-based CT is thus far the only strategy supported by several large randomized studies to improve survival. Since the publication of this meta-analysis, many clinical trials [13-17, and 22] and meta-analyses [20, 21] have clearly demonstrated that CT administered concurrently with RT as the most efficacious. The roles of neoadjuvantCT (NACT), and ACT in OS, and their impact on locoregional control and distant metastases still remain controversial.

At present, concurrent CT during the course of RT should be considered the standard of care. Weekly (30-40 mg/m2) as well as 3-weekly (100 mg/m2) cisplatin-based regimens are accepted as standard practice. Toxic effects are considerable with the 3-weekly schedule as revealed by the Intergroup study[7] in which only 63% of patients having received all three 3-weekly-courses of concurrent 100mg/m2 cisplatin. In the phase III randomized trial from Hong Kong, low-dose cisplatin (40 mg/m2) given in a weekly cycle during the entire course of RT has been shown to improve overall survival (OS), especially in the T3 to T4 subgroup(For the CCRT arm, the 5-year OS and PFS rates were 70.3 and 60.2%, respectively). In terms of toxicity and compliance to CT, the systemic and local toxicities were generally acceptable, 60% of patients completed at least 5 cycles of concurrent cisplatin, and only 44% completed the planned 6 cycles of concurrent cisplatin during RT [10]. Kim and al have retrospectively reviewed their experience of both weekly and 3-weekly regimens. They have found weekly scheduling practical and feasible for CCRT in NPC, resulting in decreased interruptions in radiation treatment and minimal acute toxic events without compromising local control [27]. There is a trend for centers in the endemic regions opting for the weekly regimen due to the more favorable toxicity profile and comparable efficacy. For these reasons, we adopted in our study a concurrent weekly cisplatin (40 mg/m2) protocol, all patients had relatively good compliance, and 58% of patients completed at least 5 cycles of concurrent cisplatin. No fatal toxicity related to planed treatment was observed. Although a high incidence of grade 1 or 2 mucositis, vomiting, and leukopenia, our CCRT protocol was more tolerable, with less severe grade 3 to 4 toxicities than many previous trials.

Interestingly, 2 retrospective reports revealed that the dose of cisplatin during the CCRT had a significant prognostic impact. They found that the number of cycles of concurrent cisplatin-based CT was significantly associated with OS in the stage III subgroup, but not in stage IV [28, 29]. A possible explanation for this may be the fact CCRT for these patients with such high-risk disease may not be enough to improve their outcome significantly. This will thus warrant further exploration of NACT or ACT as an additional treatment modality of this subset of patients. In our study, patients who received more than 5 cycles of cisplatin during CRT had betterprognosis than those who did not. This is consistent with the findings of the previous study [28, 29]. Limited by the fact that these were retrospective analyses, the causal relationship between cycles of cisplatin and improvement in OS is not clearly defined. However, until further confirmatory studies are available, these results should at least enable us to advise our patients that

compliance to CT during CCRT may influence prognosis. Despite patients included in our retrospective study did not receive ACTfollowing CCRT, a 5-year OS rate of 70% a 5-year DFS rate of 63% were obtained. These results are in line with published data [7-10] and highlight the need of further phase III trials to assess the role of ACT following CCRT.Recently, Chen and al have published the findings of their randomized phase III trial of CCRT and ACT versus CCRT alone involving over 500 patients with non-metastatic stage III-IV NPC. At a median follow-up for 38 months, there was no significant difference in the estimated 2-year failure free survival rate in the CCRT and ACT versus the CCRT alone arms. In terms of toxicity, 42% of the 205 patients on the ACT arm experienced grade 3-4 toxicities during ACT, with 17% of patients having experienced significant hematological toxicities[30].A recent meta-analysis hasshown similar findings[31].One possible way to select better patients suitable for an adjuvant approach may be assessment of plasma EBV DNA levels. An early post-CCRT detection of high EBV DNA levels may be an indication to administer ACT. Chan and al are conducting a clinical trial with the use of post-RT EBV DNA to select high-risk patients to be randomized to receive ACT versus observation. This study is ongoing and results expected in the coming 2 years [32].

Lin and al pointed out that CCRT was inadequate for high-risk patients (nodal size >6 cm, supraclavicular node metastases, 1992 AJCC stage T4N2, and multiple neck node metastases with 1 node >4 cm) with similar 5-year OS compared to RT alone (55.8% vs. 46.3%, p= 0.176) [33]. One strategy to further improve the efficacy of CT for high-risk NPC patients is to use more aggressive treatment with NACT in addition to CCRT. Induction CT is generally better tolerated than ACT and might provide early eradication of distant micro-metastases. In addition, NAC could shrink the primary tumor to give wider margins for irradiation. A several phase II clinical studies, using intensive NACT followed by CCRT, have shown encouraging toxicity profiles and disease control [34, 35].Liang and al have published the first meta-analysisto evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of the NACT followed by CCRT versus CCRT with or without AC for loco-regionally advanced NPC.They found that NACT followed by CCRT was well tolerated but could not significantly improve prognosis in terms of overall survival, loco-regional failure-free survival or distant metastasis failure-free survival [36]. Perhaps, this might be related with the fact that NACTdelayed the time of RT.

While results of numerous randomized clinical trials have confirmed efficacy of CCRT over RT alone for loco-regionally advanced NPC, the question arises as to whether the CCRT has an impact on the outcome of early stage disease. Chen and colleagues published their randomized phase III prospective study of stage II NPC patients. Patients were randomized to either conventional RT alone (n = 114) or CCRT (n = 116) with concurrent weekly cisplatin at 30 mg/m2. At a median follow-up at 60 months, the addition of CT statistically improved the 5-year OS rate (94.5 vs 85.8%, p= 0.007), PFS (88 vs 79%, p=0.017, and MRFS (95 vs 84%, p=0.007). Surprisingly, there was no statistically significant difference in the 5-year LRRFS rate (93 vs 91.1%, p= 0.29) [37]. The intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) is widely employed as an alternative to conventional RT in NPC patients with stage I-II disease, but its role in association with CT is still unknown. Thamet al evaluated the treatment outcome of 107 patients with stage IIB NPC after IMRTwith or without CT. They found that IMRT without concurrent CT provides good treatment outcome with acceptable toxicityand without significant difference in patients treated with CT [38].As there are no published prospective data on the impact of CCRT in stage II NPC patients treated with IMRT, a defining conclusion of CCRT in the IMRT-era for early stage NPC patients cannot be drawn. The practice of CCRT in stage II disease is acceptable as long as a balance is taken with the associated short and long-term toxicities of concurrent CT.In anothertrial, 868 non-metastatic NPC patients treated by IMRT were analyzed retrospectively. With a median follow-up of 50 months, the 5-year estimated disease specific survival (DSS), local recurrence-free survival (LRFS), regional recurrence-free survival (RRFS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) were 84.7%, 91.8%, 96.4% and 84.6%, respectively. The toxicity profile was very low. Concurrent chemotherapy failed to improve survival rates for patients with advanced locoregional disease and increased

the severity of acute toxicities [39].

CONCLUSION

Our study confirms that weekly cisplatin concurrent with RT for locally advanced nasopharyngeal cancers was found tolerable with a high efficiency and provides further evidence on the prognostic significance of CT dosing during the concurrent phase with RT.

REFERENCES

1. Boussen H, Bouaouina N, Gamoudi A, Mokni N, Benna F, Boussen I, Ladgham A. EMC oto-rhino-laryngologie : Cancers du nasopharynx. Elsevier Masson, 2007.

2. Altun M, Fandi A, Dupuis O, et al: Undifferentiated nasopharyngeal cancer (UCNT): Current diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Int J RadiatOncolBiol Phys. 1995; 32:859-77.

3. Registre des cancers Nord-Tunisie. Données 1999-2003. Evolution 1994-2003. Projections à l’horizon 202

4.

4. Yeh SA, Tang Y, Lui CC, Huang YJ, Huang EY. Treatment outcomes and late complications of 849 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma treated with radiotherapy alone. Int J RadiatOncolBiol Phys. 2005;62:672-9.

5. Lee AW, Poon YF, Foo W, Law SC, Cheung FK, Chan DK, Tung SY, Thaw M, Ho JH. Retrospectiveanalysis of 5037 patients with nasopharyngealcarcinoma treated during 1976-1985:Overall survival and patterns of failure. Int JRadiatOncolBiol Phys. 1992; 23:261-270,

6.

6. Teo P, Yu P, Lee WY, Leung SF, Kwan WH, Yu KH, Choi P, Johnson PJ. Significant prognostic factorsafter primary radiotherapy in 903 non-disseminated nasopharyngealcarcinoma evaluated by computed tomography.Int J RadiatOncolBiol Phys. 1996;36:291-304.

7. Al-Sarraf M, LeBlanc M, Giri PG, Fu KK, Cooper J, Vuong T, Forastiere AA, Adams G, Sakr WA, Schuller DE, Ensley JF.Chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy in patients with advanced nasopharyngeal cancer: phase III randomized Intergroup study 0099. J ClinOncol. 1998;16:1310-7.

8. Lin JC, Jan JS, Hsu CY, Liang WM, Jiang RS, Wang WY.Phase III study of concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: positive effect on overall and progression-free survival. J ClinOncol. 2003;2:631-7.

9. Kwong DL, Sham JS, Au GK, Chua DT, Kwong PW, Cheng AC, Wu PM, Law MW, Kwok CC, Yau CC, Wan KY, Chan RT, Choy DD.Concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a factorial study. J ClinOncol. 2004;22:2643-53.

10. Chan AT, Leung SF, Ngan RK, Teo PM, Lau WH, Kwan WH, Hui EP, Yiu HY, Yeo W, Cheung FY, Yu KH, Chiu KW, Chan DT, Mok TS, Yau S, Yuen KT, Mo FK, Lai MM, Ma BB, Kam MK, Leung TW, Johnson PJ, Choi PH, Zee BC.Overall survival after concurrent cisplatin-radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:536-9.

11. Lee AW, Lau WH, Tung SY, Chua DT, Chappell R, Xu L, Siu L, Sze WM, Leung TW, Sham JS, Ngan RK, Law SC, Yau TK, Au JS, O'Sullivan B, Pang ES, O SK, Au GK, Lau JT; Hong Kong Nasopharyngeal Cancer Study Group. Preliminary results of a randomized study on therapeutic gain by concurrent chemotherapy for regionally-advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: NPC-9901 Trial by the Hong Kong Nasopharyngeal Cancer Study Group. J ClinOncol. 2005;23:6966-75.

12. Chua DT, Ma J, Sham JS, Mai HQ, Choy DT, Hong MH, Lu TX, Min HQ. Long-term survival after cisplatin-based induction chemotherapy and radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a pooled data analysis of two phase III trials.J ClinOncol. 2005;23:1118-24.

13. Wee J, Tan EH, Tai BC, Wong HB, Leong SS, Tan T, Chua ET, Yang E, Lee KM, Fong KW, Tan HS, Lee KS, Loong S, Sethi V, Chua EJ, Machin D. Randomized trial of radiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer/International Union against cancer stage III and IV nasopharyngeal cancer of the endemic variety. J ClinOncol. 2005;23:6730-8.

14. Lee AW, Tung SY, Chua DT, Ngan RK, Chappell R, Tung R, Siu L, Ng WT, Sze WK, Au GK, Law SC, O'Sullivan B, Yau TK, Leung TW, Au JS, Sze WM, Choi CW, Fung KK, Lau JT, Lau

WH. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1188-98.

15. Lee AW, Tung SY, Chan AT, Chappell R, Fu YT, Lu TX, Tan T, Chua DT, O'sullivan B, Xu SL, Pang ES, Sze WM, Leung TW, Kwan WH, Chan PT, Liu XF, Tan EH, Sham JS, Siu L, Lau WH.Preliminary results of a randomized study (NPC-9902 Trial) on therapeutic gain by concurrent chemotherapy and/or accelerated fractionation for locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int J RadiatOncolBiol Phys. 2006;66:142-51.

16. Lee AW, Tung SY, Chan AT, Chappell R, Fu YT, Lu TX, Tan T, Chua DT, O'Sullivan B, Tung R, Ng WT, Leung TW, Leung SF, Yau S, Zhao C, Tan EH, Au GK, Siu L, Fung KK, Lau WH.A randomized trial on addition of concurrent-adjuvant chemotherapy and/or accelerated fractionation for locally-advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma.RadiotherOncol. 2011;98:15-22.

17. Zhang L, Zhao C, Peng PJ, Lu LX, Huang PY, Han F, Wu SX.Phase III study comparing standard radiotherapy with or without weekly oxaliplatin in treatment of locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: preliminary results. J ClinOncol. 2005;23:8461-8.

18. Huncharek M, Kupelnick https://www.doczj.com/doc/ca19021965.html,bined chemoradiation versus radiation therapy alone in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: results of a meta-analysis of 1,528 patients from six randomized trials. Am J ClinOncol. 2002;25:219-23.

19. Baujat B, Audry H, Bourhis J, Chan AT, Onat H, Chua DT, Kwong DL, Al-Sarraf M, Chi KH, Hareyama M, Leung SF, Thephamongkhol K, Pignon JP; MAC-NPC Collaborative Group.Chemotherapy in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an individual patient data meta-analysis of eight randomized trials and 1753 patients.Int J RadiatOncolBiol Phys. 2006;64:47-56.

20. Zhang L, Zhao C, Ghimire B, Hong MH, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Huang YJ, Guan ZZ. The role of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in the treatment of locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma among endemic population: a meta-analysis of the phase III randomized trials. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:558.

21. Yang AK, Liu TR, Guo X, Qi GL, Chen FJ, Guo ZM, Zhang Q, Zeng ZY, Chen WC, Li QL.Concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. ZhonghuaEr Bi Yan HouTou Jing WaiKeZaZhi. 2008;43:218-23.

22. Chen Y, Liu MZ, Liang SB, et al. Preliminary results of a prospective randomized trial comparing concurrent chemoradiotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy with radiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma in endemic regions of China. Int J RadiatOncolBiol Phys.2008;71:1356-64.

23. Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF: Toxicity criteriaof the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group(RTOG) and the European Organization for Researchand Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int JRadiatOncolBiol Phys. 1995;31:1341-6.

24. Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, et al:Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47:207-214.

25. Perri F, Bosso D, Buonerba C, Lorenzo GD, Scarpati GD.Locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Current andemerging treatment strategies. World J Clin Oncol.2011;2:377-383.

26. Chan AT, Gregoire V, Lefebvre JL, et al. Nasopharyngeal cancer: EHNS-ESMOESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl. 7) [vii83-85].

27. Kim TH, Ko YH, Lee MA, et al. Treatment outcome of cisplatin-based concurrent chemoradiotherapy in the patients with locally advanced nasopharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2008;40:62-70.

28. Lee AW, Tung SY, Ngan RK, et al. Factors contributing to the efficacy of concurrent-adjuvant chemotherapy for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: combined analyses of NPC-9901 and NPC-9902 Trials. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:656–66.

29. Loong HH, Ma BB, Leung SF, et al. Prognostic significance of the total dose of cisplatin administered during concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. RadiotherOncol. 2012;104:300-4. 30. Chen L, Hu CS, Chen XZ, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy plus adjuvant chemotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a phase 3 multicentrerandomised

controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:163-71.

31. Liang ZG, Zhu XD, Zhou ZR, Qu S, Du YQ, Jiang https://www.doczj.com/doc/ca19021965.html,parison of concurrent chemoradiotherapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy alone in locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a meta-analysis of 793 patients from 5 randomized controlled https://www.doczj.com/doc/ca19021965.html,n Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13:5747-52.

32. Chan A, Ngan RK, Hui EP, et al. A multicenter randomized control trial (RCT) of adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) in nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) with residual plasma EBV DNA (EBV DNA) following primary radiotherapy (RT) or chemotherapy (CRT). J ClinOncol.2012;30.

33. Lin JC, Liang WM, Jan JS, Jiang RS, Lin AC.Another way to estimate outcome of advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma--is concurrent chemoradiotherapy adequate? Int J RadiatOncolBiol Phys. 2004;60:156-64.

34. Hui EP, Ma BB, Leung SF, et al. Randomized phase II trial of concurrent cisplatin-radiotherapy with or without neoadjuvantdocetaxel and cisplatin in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J ClinOncol. 2009;27:242-9.

35. Ferrari D, Chiesa F, CodecàC, Calabrese L, Jereczek-Fossa BA, Alterio D, Fiore J, Luciani A, Floriani I, Orecchia R, Foa P. Locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: induction chemotherapy with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil followed by radiotherapy and concurrent cisplatin: a phase II study. Oncology. 2008;74:158-166.

36. Liang ZG, Zhu XD, Tan AH, Jiang YM, Qu S, Su F, Xu GZ. Induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy versus concurrent chemoradiotherapy with or without adjuvant chemotherapy for locoregionally advanced nasopharyngealcarcinoma: meta-analysis of 1,096 patients from 11 randomized controlled trials. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:515-21.

37. Chen QY, Wen YF, Guo L, et al. Concurrent chemoradiotherapy vs radiotherapy alone in stage II nasopharyngeal carcinoma: phase III randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:1761-70.

38.Tham IW, Lin S, Pan J, Han L, Lu JJ, Wee J.Intensity-modulated radiation therapy without concurrent chemotherapy for stage IIb nasopharyngeal cancer.Am J ClinOncol. 2010;33(3):294-9.

39. Sun X, Su S, Chen C, Han F, Zhao C, Xiao W, Deng X, Huang S, Lin C, Lu T.Long-term outcomes of intensity-modulated radiotherapy for 868 patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: an analysis of survival and treatment toxicities.RadiotherOncol. 2014;110(3):398-403.