Abscisic acid dynamics in roots detected with genetically encoded FRET sensors

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:4.78 MB

- 文档页数:30

拟南芥ABI5亚家族基因在植物生长发育过程中表达的时空特异性研究拟南芥ABI5亚家族基因在植物生长发育过程中表达的时空特异性研究摘要:拟南芥(Arabidopsis thaliana)是一种被广泛应用于植物研究的模式植物,其生长发育过程受到多种内外因素的调控。

ABI5(ABA Insensitive 5)亚家族基因在植物的逆境响应(如胁迫、水分和盐浓度等)中起着重要作用。

本研究旨在探究拟南芥ABI5亚家族基因在不同组织器官和发育时期的表达特点,进一步揭示ABI5基因在植物生长发育过程中的功能。

1. 引言拟南芥作为一种典型的模式植物,其基因组已经被完整测序,并且拥有丰富的遗传工具和生理研究方法。

在过去的研究中,被发现ABI5亚家族基因参与了拟南芥的植物生长发育,特别是在逆境响应中起到关键作用。

2. 研究方法本研究使用拟南芥WT(野生型)作为材料,通过RT-PCR和荧光素酶报告基因GUS(β葡萄糖苷酶)构建了ABI5基因的表达谱,以探究其在不同组织器官和发育时期的表达特点。

3. 结果与讨论(1)ABI5的组织特异性表达:结果显示,在根、茎和叶片等不同组织中,ABI5基因均表现出不同程度的表达。

而在根尖和侧根发育过程中,其表达量显著增加,表明ABI5可能在根部器官的生长和发育中发挥重要作用。

(2)ABI5的发育时期表达:通过GUS染色和实时荧光PCR等技术,我们发现ABI5基因主要在花和种子的发育阶段表达,显示了其在拟南芥生殖器官的发育过程中的重要性。

4. 结论本研究揭示了拟南芥ABI5亚家族基因在植物生长发育过程中的时空特异性表达。

结果表明,ABI5基因在根部器官的生长和发育以及花和种子的发育阶段具有重要功能,为进一步研究ABI5基因在逆境响应中的机制和作用提供了参考。

5. 局限性与展望本研究依然存在一些局限性,如只选取拟南芥WT进行表达分析,没有涉及基因功能验证等进一步研究。

今后的工作可以进一步探究ABI5基因的调控网络以及与其他基因间的相互作用,以更深入地解读其在植物生长发育中的重要功能。

维生素C与基因互作的研究摘要:维生素C(又称抗坏血酸)是一种动物机体所必需的营养素,它是电子供体,因此具有抗氧化性。

本文主要介绍维生素C的性质,维生素C在植物体和某些动物体内的合成途径,以及其在机体内对基因表达的作用,以及近年来对维生素C的研究进展。

关键词:维生素C、抗氧化性、基因表达、合成途径、作用正文:1 维生素C的简介中文名称:维生素C英文名称:vitamin C其他名称:抗坏血酸(ascorbic acid)维生素c键线式:定义:显示抗坏血酸生物活性的化合物的通称,是一种水溶性维生素,水果和蔬菜中含量丰富。

在氧化还原代谢反应中起调节作用,缺乏它可引起坏血病。

维生素C(维生素C),又称抗坏血酸(ascorbic acid, AsA),是普遍存在于植物组织中的高丰度小分子抗氧化物质。

某些动物如人类由于缺乏其合成关键酶L-古洛糖内酯氧化酶不能自身合成维生素C,并且其在人体内不能长久贮存,只能不断从食物中获取维生素C而作为主要维生素C来源的水果和蔬菜其维生素C水平差异较大。

因此维生素C 含量已成为衡量农产品品质的重要指标。

此外,植物中的维生素C 还在抗氧化和清除自由基、光合作用和光保护、细胞的生长和分裂以及参与某些次生代谢物和乙烯的合成等诸多方面起着非常重要的生理功能。

2 植物中维生素c合成的途径2.1 与动物合成途径类似的古洛糖途径Isherwood 等最早提出的类似于动物合成途径的高等植物维生素C生物合成途径,该途径认为植物由D-半乳糖经D-半乳糖醛酸和L-半乳糖内酯(L-GalL)等重要中间物质最终形成维生素C,其间发生了类似动物的碳链倒位。

支持该途径的证据为在植物体内确实存在天然L-GalL并可通过半乳糖内酯脱氢酶(GalLDH)氧化生成维生素C,同时D-半乳糖醛酸(甲酯)也可作为维生素C合成的底物。

但随后的同位素放射性示踪证明植物合成维生素C的过程并未发生碳链的倒位。

虽然有证据显示L-GalL是植物合成维生素C的底物,但D-半乳糖醛酸并不是植物合成维生素C2.2 邻酮醛糖途径为符合同位素放射性示踪实验结果,Loewus等提出的一条非倒位途径即临酮醛糖途径。

Arabidopsis EPSIN1Plays an Important Role in VacuolarTrafficking of Soluble Cargo Proteins in Plant Cells via Interactions with Clathrin,AP-1,VTI11,and VSR1WJinhee Song,Myoung Hui Lee,Gil-Je Lee,Cheol Min Yoo,and Inhwan Hwang1Division of Molecular and Life Sciences and Center for Plant Intracellular Trafficking,Pohang University of Scienceand Technology,Pohang790-784,KoreaEpsin and related proteins play important roles in various steps of protein trafficking in animal and yeast cells.Many epsin homologs have been identified in plant cells from analysis of genome sequences.However,their roles have not been elucidated.Here,we investigate the expression,localization,and biological role in protein trafficking of an epsin homolog, Arabidopsis thaliana EPSIN1,which is expressed in most tissues we examined.In the cell,one pool of EPSIN1is associated with actinfilaments,producing a network pattern,and a second pool localizes primarily to the Golgi complex with a minor portion to the prevacuolar compartment,producing a punctate staining pattern.Protein pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation experiments reveal that Arabidopsis EPSIN1interacts with clathrin,VTI11,g-adaptin-related protein(g-ADR),and vacuolar sorting receptor1(VSR1).In addition,EPSIN1colocalizes with clathrin and VTI11.The epsin1mutant,which has a T-DNA insertion in EPSIN1,displays a defect in the vacuolar trafficking of sporamin:greenfluorescent protein(GFP),but not in the secretion of invertase:GFP into the medium.Stably expressed HA:EPSIN1complements this trafficking defect.Based on these data,we propose that EPSIN1plays an important role in the vacuolar trafficking of soluble proteins at the trans-Golgi network via its interaction with g-ADR,VTI11,VSR1,and clathrin.INTRODUCTIONAfter translation in eukaryotic cells,a large number of proteins are transported to subcellular compartments by a variety of different mechanisms.Newly synthesized vacuolar proteins that are delivered to the endoplasmic reticulum(ER)by the cotrans-lational translocation mechanism are transported to the vacuole from the ER by a process called intracellular trafficking.Traffick-ing of a protein to the vacuole from the ER occurs through two organelles,the Golgi complex and the prevacuolar compartment (PVC)(Rothman,1994;Hawes et al.,1999;Bassham and Raikhel, 2000;Griffiths,2000).Transport of a protein from the ER to the Golgi complex is performed by coat protein complex II vesicles. Transport from the trans-Golgi network(TGN)to the PVC occurs via clathrin-coated vesicles(CCVs)(Robinson et al.,1998;Tang et al.,2005;Yang et al.,2005).Transport of a protein from the ER to the vacuole/lysosome requires a large number of proteins,including components of vesicles,factors involved in vesicle generation and fusion,reg-ulators of intracellular trafficking,adaptors for the cargo proteins, and other accessory proteins(Robinson and Kreis,1992;Bennett, 1995;Schekman and Orci,1996;da Silva Conceic¸a˜o et al.,1997;Kirchhausen,1999;Sever et al.,1999;Bassham and Raikhel, 2000;Griffiths,2000;Jin et al.,2001;Robinson and Bonifacino, 2001).Most of these proteins are found in all eukaryotic cells from yeast,animals,and plants,suggesting that protein traffick-ing mechanisms from the ER to the vacuole/lysosome may be highly conserved in all eukaryotic cells.Of the large number of proteins involved in intracellular traf-ficking,a group of proteins that have the highly conserved epsin N-terminal homology(ENTH)domain have been identified as playing a critical role at various trafficking steps in animal and yeast cells(Chen et al.,1998;De Camilli et al.,2002;Wendland, 2002;Overstreet et al.,2003;Legendre-Guillemin et al.,2004). The ENTH domain binds to phosphatidylinositols(PtdIns), although the lipid binding specificity differs with individual members of the epsin family.For example,epsin1binds to PtdIns(4,5)P2,whereas EpsinR and Ent3p bind to PtdIns(4)P and PdtIns(3,5)P2,respectively(Itoh et al.,2001).The ENTH domain is thought to be responsible for targeting these proteins to specific compartments and also for introducing curvature to the bound membranes to assist in the generation of CCVs(Legendre-Guillemin et al.,2004).However,the exact steps of intracellular trafficking in which ENTH-containing proteins play a role are complex.Epsin homologs can be divided into two groups based on the pathway in which they play a role.One group,which includes epsin1in animal cells and Ent1p and Ent2p in yeast cells,is involved in endocytosis from the plasma membrane (Chen et al.,1998;De Camilli et al.,2002;Wendland,2002).The other group,which includes EpsinR/clint/enthoprotin in animal cells and Ent3p and Ent4p in yeast cells,is involved in protein trafficking from the TGN to the lysosome/vacuole as well as1To whom correspondence should be addressed.E-mail ihhwang@postech.ac.kr;fax82-54-279-8159.The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to thefindings presented in this article in accordance with the policy describedin the Instructions for Authors()is:Inhwan Hwang(ihhwang@postech.ac.kr).W Online version contains Web-only data./cgi/doi/10.1105/tpc.105.039123The Plant Cell,Vol.18,2258–2274,September2006,ª2006American Society of Plant Biologistsretrograde trafficking from the early endosomes to the TGN (Kalthoff et al.,2002;Wasiak et al.,2002;Hirst et al.,2003; Chidambaram et al.,2004;Eugster et al.,2004;Saint-Pol et al., 2004).Another common feature of epsin-related proteins is that they play a role in CCV-mediated protein trafficking at both the TGN and the plasma membrane.These proteins can bind directly to clathrin through their multiple clathrin binding motifs;thus,they may recruit clathrin to the plasma membrane or the TGN to generate CCVs(Rosenthal et al.,1999;Wendland et al.,1999; Drake et al.,2000).In addition,these proteins interact with many other proteins,such as heterotetrameric clathrin adaptor complexes(APs),monomeric adaptor Golgi-localized,g-ear–containing Arf binding proteins(GGAs),and soluble NSF attach-ment protein receptors(SNAREs).Epsin1interacts with AP-2, Epsin15,and intersectin(Chen et al.,1998;Legendre-Guillemin et al.,2004),whereas EpsinR/enthoprotin/clint and Ent3p interact with SNAREs such as vti1b and vti1p,respectively (Chidambaram et al.,2004)and with adaptor proteins such as GGAs and AP-1(Duncan et al.,2003;Mills et al.,2003).In addition,epsin homologs have ubiquitin-interacting motifs and are ubiquitinated(Oldham et al.,2002;Shih et al.,2002).Protein ubiquitination acts as a signal for endocytosis from the plasma membrane and trafficking from the TGN through the endosome/ PVC to the lysosome/vacuole(Polo et al.,2002;Horak,2003; Raiborg et al.,2003;Scott et al.,2004).The binding of epsin homologs to ubiquitin raises the possibility that epsin homologs may bind directly to cargo proteins that are destined for the vacuole/lysosome from either the plasma membrane or the TGN (Chen and De Camilli,2005;Sigismund et al.,2005).In plant cells,sequence analysis of the entire Arabidopsis thaliana genome reveals several proteins with the highly con-served ENTH domains(Holstein and Oliviusson,2005).However, their biological roles have not been addressed.In this study,we investigate the functional role of EPSIN1,an Arabidopsis epsin homolog,at the molecular level.In particular,we focus on its possible role in protein trafficking in plant cells.We demonstrate that EPSIN1interacts with clathrin,AP-1,VSR1,and VTI11and plays an important role in the vacuolar trafficking of a soluble protein from the Golgi complex to the central vacuole.RESULTSEPSIN1,a Member of the Epsin Family,Is Ubiquitously Expressed in ArabidopsisThe Arabidopsis genome encodes three highly similar epsin-related proteins,EPSIN1,EPSIN2,and EPSIN3(Holstein and Oliviusson,2005).In this study,we investigated the biological role of EPSIN1.EPSIN1has the highly conserved ENTH domain at the N terminus.However,the rest of the molecule is less similar to other epsin-related proteins,although it has motifs,such as LIDL and DPF,that may function as clathrin and AP-1binding motifs,respectively.To understand the biological role of EPSIN1,its expression in various plant tissues was examined.An antibody was raised against the middle domain of EPSIN1(amino acid residues153to 337).The antibody recognized a protein band at90kD,which was much larger than the expected size,60kD,of EPSIN1 (Figure1A).It was shown previously that epsin-related proteins migrate slower than expected in SDS-PAGE(Chen et al.,1998). The control serum did not recognize any protein bands.This re-sult suggested that the antibody specifically recognized EPSIN1. To confirm this,protoplasts were transformed with EPSIN1 tagged with HA at the N terminus(HA:EPSIN1)and protein extracts from the transformed protoplasts were analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-HA and anti-EPSIN1antibodies. The anti-HA antibody specifically recognized a protein band from the transformed protoplasts,but not from the untransformed protoplasts,at90kD(Figure1B).In addition,the90-kD protein species was recognized by the anti-EPSIN1antibody,confirming that the90-kD band was EPSIN1.The expression of EPSIN1in various tissues was examined using the anti-EPSIN1antibody. Protein extracts were prepared from various tissues at different stages of plant growth and used for protein gel blot analysis. EPSIN1was expressed in all of the tissues examined,with the highest expression in cotyledons andflowers(Figure1C). EPSIN1Produces Both Network and PunctateStaining PatternsTo examine the subcellular distribution of EPSIN1,total protein extracts from leaf tissues were separated into soluble and membrane fractions and analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-EPSIN1antibody.EPSIN1was detected in both membrane (pellet)and soluble fractions(Figure2A).As controls for the fractionation,Arabidopsis aleurain-like protease(AALP)and Arabi-dopsis vacuolar sorting receptor(VSR)were detected with anti-AALP and anti-VSR antibodies,respectively(Sohn et al.,2003). AALP is a soluble protein present in the vacuolar lumen,and VSR is a membrane protein that is localized primarily to the PVC with a minor portion to the Golgi complex(da Silva Conceic¸a˜o et al., 1997;Ahmed et al.,2000).As expected,AALP and VSR were detected in the supernatant and pellet fractions,respectively. These results indicated that EPSIN1localized to multiple loca-tions,consistent with the behavior of other epsin-related proteins (Legendre-Guillemin et al.,2004).Next,we defined the subcellular localization of EPSIN1.Our initial attempts to localize the endogenous EPSIN1with the anti-EPSIN1antibody failed.Thus,we determined the localization of EPSIN1protein transiently expressed in protoplasts.EPSIN1 was tagged with the HA epitope,greenfluorescent protein(GFP), or redfluorescent protein(RFP).The amount of total EPSIN1 protein was determined using various amounts of HA:EPSIN1 plasmid DNA by protein gel blot analysis with anti-EPSIN1an-tibody and was found to be proportional to the amount of plasmid used(Figure2B).For the localization,we used a minimal amount(5to10m g)of EPSIN1plasmid DNAs.Protoplasts were transformed with HA:EPSIN1,and localization of EPSIN1 was determined by immunostaining with anti-HA antibody.HA: EPSIN1produced primarily a punctate staining pattern(Figure 2Ca).In addition to punctate stains,we occasionally observed weakly stained strings that connected punctate stains(Figure 2Cc,arrowheads).By contrast,the nontransformed controls did not produce any patterns(Figure2Ce).In protoplasts trans-formed with EPSIN1:GFP and EPSIN1:RFP,both EPSIN1fusionEPSIN1in Vacuolar Trafficking2259proteins produced a network pattern with punctate stains (Fig-ures 2Cg and 2Ch),whereas GFP and RFP alone produced diffuse patterns (Figures 2Dh and 2Di),indicating that EPSIN1produces the network pattern with punctate stains.These results were further confirmed by cotransforming the protoplasts with either EPSIN1:GFP and HA:EPSIN1or EPSIN1:GFP and EPSIN1:RFP .The punctate staining pattern of EPSIN1:GFP closely over-lapped that of HA:EPSIN1(Figures 2Da to 2Dc).In addition,the network and punctate staining patterns of EPSIN1:GFP closely overlapped those of EPSIN1:RFP (Figures 2De to 2Dg).However,the fine networks revealed by EPSIN1:GFP in the live protoplasts were nearly absent in the fixed protoplasts.Thus,the differences in the staining patterns between fixed and live protoplasts may be attributable to the fact that the network pattern of live protoplasts are not well preserved under the fixing conditions used.In addi-tion,the strings occasionally observed in the fixed protoplasts may represent the remnants of the network pattern revealed by HA:EPSIN1.These results strongly suggest that EPSIN1is re-sponsible for the network pattern as well as the punctate stains.The network pattern was reminiscent of the ER or actin pattern in plant cells (Boevink et al.,1998;Jin et al.,2001;Kim et al.,2005),whereas the punctate staining pattern suggested that EPSIN1may localize to the Golgi complex or endosomes,as observed previously with epsin homologs in animal and yeast cells (Wasiak et al.,2002;Chidambaram et al.,2004;Saint-Pol et al.,2004).Therefore,protoplasts were cotransformed with EPSIN1:RFP and GFP:talin ,a marker for actin filaments consist-ing of GFP and the actin binding domain of mouse talin (Kost et al.,1998;Kim et al.,2005).As expected,GFP:talin produced the network pattern (Figure 3A)(Kost et al.,1998;Kim et al.,2005).Furthermore,the red fluorescent network pattern of EPSIN1:RFP closely overlapped the green fluorescent network pattern of GFP:talin (Figure 3A),raising the possibility that EPSIN1:GFP bound to the actin filaments rather than to the ER.To confirm this,the EPSIN1:RFP pattern was examined after treatment with latrunculin B (Lat B),a chemical agent known to disrupt actin filaments (Spector et al.,1983).Lat B–treated protoplasts produced the diffuse green fluorescent pattern of GFP:talin (Figure 3A),an indication of solubilized actin filaments,as observed previously (Kim et al.,2005).In addition,the Lat B–treated protoplasts displayed a diffuse red fluorescent pattern of EPSIN1:RFP (Figure 3A),indicating that EPSIN1is associated with actin filaments but not with the ER.Furthermore,the punc-tate staining pattern of EPSIN1:RFP also was not observed in the presence of Lat B,indicating that actin filaments played a role in yielding the punctate staining pattern of EPSIN1.In the same conditions,BiP:GFP,an ER marker (Lee et al.,2002),produced a network pattern,indicating that Lat B does not disrupt the ER network patterns (Figure 3Ai).To identify the organelle responsible for the punctate staining pattern of EPSIN1,its localization was compared with that of ST:GFP and PEP12p/SYP21.ST:GFP,a chimericproteinFigure 1.EPSIN1Is Expressed in Various Arabidopsis Tissues.(A)Generation of anti-EPSIN1antibody.The middle domain,corresponding to amino acid residues 153to 337,was expressed as the Hisx6-tagged form in E.coli and used to raise antibody in a rabbit.Control serum was obtained from the rabbit before immunization.Total protein extracts were obtained from leaf tissues and used to test the anti-EPSIN1antibody.(B)Specificity of the anti-EPSIN1antibody.Protein extracts were obtained from protoplasts expressing EPSIN1tagged with the HA epitope at the N terminus and used for protein gel blot analysis using anti-HA and anti-EPSIN1antibodies.(C)Expression of EPSIN1in various tissues.Total protein extracts from the indicated tissues were analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-EPSIN1antibody.Leaf tissues were harvested 11and 20d after germination.Cotyledons were obtained from 5-d-old plants.The membranes were stained with Coomassie blue to control for protein loading.RbcL,large subunit of the ribulose-1,5-bis-phosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco)complex.2260The Plant CellFigure 2.EPSIN1Produces Both Network and Punctate Staining Patterns.(A)Subcellular fractionation of EPSIN1.Total (T)protein extracts of leaf tissues were separated into soluble (S)and pellet (P)fractions and analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-EPSIN1,anti-AALP,and anti-VSR antibodies.(B)Expression level of EPSIN1in transformed protoplasts.Protoplasts were transformed with various amounts of HA:EPSIN1DNA,and the level of EPSIN1was determined by protein gel blotting with anti-EPSIN1antibody.Protein extracts from untransformed protoplasts were used as a control.The membrane was also stained with Coomassie blue to control for loading.(C)Localization of EPSIN1.Protoplasts were transformed with the indicated constructs (5to 10m g),and the localization of EPSIN1was examined either by immunostaining with anti-HA antibody or by direct detection of the GFP or RFP signal.Untransformed protoplasts were immunostained with anti-HA antibody as a control.Bars ¼20m m.(D)Colocalization of EPSIN1proteins.The localization of EPSIN1protein was examined in protoplasts transformed with HA:EPSIN1and EPSIN1:GFP or with EPSIN1:GFP and EPSIN1:RFP .As controls,GFP and RFP alone were transformed into protoplasts.Bars ¼20m m.EPSIN1in Vacuolar Trafficking 2261亚细胞定位可以荧光观察也可以做western 检测Figure 3.Localization of EPSIN1in Protoplasts.2262The Plant Cellbetween rat sialyltransferase and GFP,localizes to the Golgi complex,and PEP12p,a t-SNARE,localizes to the PVC(da Silva Conceic¸a˜o et al.,1997;Boevink et al.,1998;Jin et al.,2001). Protoplasts were cotransformed with HA:EPSIN1and ST:GFP. The localization of these proteins was examined after staining with anti-HA antibody.ST:GFP was observed directly with the greenfluorescent signals.A major portion of the HA:EPSIN1-positive punctate stains closely overlapped with those of ST:GFP (Figures3Ba to3Bc).To further confirm the Golgi localization of HA:EPSIN1,protoplasts transformed with HA:EPSIN1were treated with brefeldin A(BFA),a chemical known to disrupt the Golgi complex(Driouich et al.,1993),and the localization of HA:EPSIN1was examined.In the presence of BFA,HA:EPSIN1 yielded a largely diffuse pattern with aggregates,but not the punctate staining pattern,indicating that BFA affects EPSIN1 localization(Figure3Be).In the same conditions,ST:GFP pro-duced a network pattern with large aggregates(Figure3Bg), confirming that the Golgi complex was disrupted.These results support the notion that EPSIN1localizes to the Golgi complex. Next,we examined the possibility of EPSIN1localizing to the PVC.Protoplasts were cotransformed with EPSIN1:GFP and PEP12p:HA.The localization of PEP12p:HA was examined after staining with anti-HA antibody.EPSIN1:GFP was observed di-rectly with the greenfluorescent signals.Only a minor portion of the EPSIN1:GFP-positive punctate stains overlapped with the PEP12p:HA-positive punctate stains(Figures3Bi to3Bk,ar-rows).These results indicated that EPSIN1localized primarily to the Golgi complex with a minor portion to the PVC.To obtain independent evidence for the localization,we ex-amined the colocalization of EPSIN1with VTI11,a v-SNARE that is distributed equally to both the TGN and the PVC(Zheng et al., 1999;Bassham et al.,2000;Kim et al.,2005).Protoplasts were cotransformed with EPSIN1:GFP and VTI11:HA,and the local-ization of these proteins was examined by immunostaining with anti-HA antibody.EPSIN1-positive punctate stains largely colo-calized with those of VTI11:HA(Figures3Bm to3Bo),confirming that EPSIN1localizes to both the Golgi complex and the PVC. EPSIN1Binds to and Colocalizes with ClathrinThe members of the epsin family have two clathrin binding motifs (Rosenthal et al.,1999;Wendland et al.,1999;Drake et al.,2000). Sequence analysis indicated that EPSIN1has a potential clathrin binding motif.To explore the possibility that EPSIN1binds to clathrin,glutathione S-transferase–fused EPSIN1(GST:EPSIN1) was constructed for a protein pull-down assay(Figure4A).GST: EPSIN1was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified from E. coli extracts(Figure4B).The purified GST:EPSIN1was mixed with protein extracts obtained from leaf tissues.Proteins pelleted with glutathione–agarose were analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-clathrin antibody.GST:EPSIN1,but not GST alone, precipitated from the plant extracts a180-kD protein species that was recognized by anti-clathrin antibody(Figure4C),indi-cating that EPSIN1bound to clathrin.To further examine its binding to clathrin,EPSIN1was divided into two regions,the ENTH and the remainder of the molecule (EPSIN1D N)(Figure4A).These regions were expressed in E.coli as GST fusion proteins,GST:ENTH and GST:EPSIN1D N,re-spectively(Figure4B).Protein pull-down experiments using leaf cell extracts were performed with purified GST:ENTH and GST: EPSIN1D N.GST:EPSIN1D N,but not GST:ENTH,precipitated clathrin from the plant extracts(Figure4C).To identify the clathrin binding motif,the C-terminal region containing the putative clathrin binding motif,LIDL(Lafer,2002),as well as GST:RIDL, which contained an Arg substitution of thefirst Leu residue in the motif,were expressed as GST fusion proteins in E.coli(Figures 4A and4B).GST:LIDL,but not GST:RIDL,precipitated clathrin from protein extracts(Figure4C),indicating that the LIDL motif functioned as a clathrin binding motif.The in vitro binding of EPSIN1with clathrin strongly suggested that EPSIN1was likely to colocalize with clathrin.Therefore, immunohistochemistry for the localization of EPSIN1and clathrin was performed.Protoplasts were transformed with HA:EPSIN1, and the localization of HA:EPSIN1and clathrin was examined by staining with anti-HA and anti-clathrin antibodies,respectively. The anti-clathrin antibody produced a punctate staining pattern (Figure4D).A majority(60to70%)of the HA:EPSIN1-positive punctate stains closely overlapped with a pool(40to50%)of clathrin-positive punctate stains(Figure4D),consistent with an interaction between EPSIN1and clathrin.There was also a pool of clathrin-positive punctate stains that lacked the HA:EPSIN1 signal,suggesting that clathrin also was involved in an EPSIN1-independent process.To further characterize the interaction between EPSIN1and clathrin,we examined whether or not EPSIN1is permanently associated with CCVs.Protein extracts from leaf tissues were first separated into soluble and pellet fractions by ultracentrifu-gation.The pellet fraction was treated with Triton X-100and further fractionated by gelfiltration,and the fractions were ana-lyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-clathrin,anti-EPSIN,and anti-VSR antibodies.Clathrin was detected in a peak between 443and669kD(see Supplemental Figure1online).Interestingly, VSR,the vacuolar cargo receptor,was eluted at the same posi-tion with clathrin.By contrast,EPSIN1was eluted at90kD. These results suggest that EPSIN1is not permanently associ-ated with CCVs.Figure3.(continued).(A)Colocalization of EPSIN1with actinfilaments.Protoplasts were transformed with the indicated constructs,and the localization of these proteins was examined in the presence(þLat B)and absence(ÿLat B)of Lat B(10m M).Bars¼20m m.(B)Localization of EPSIN1to the Golgi complex and the PVC.Protoplasts were transformed with the indicated constructs,and localization of the proteins was examined after immunostaining with anti-HA.The GFP signals were observed directly in thefixed protoplasts.For BFA treatment,BFA(30 m g/mL)was added to the transformed protoplasts at24h after transformation and incubated for3h.Arrows indicate the overlap between EPSIN1:GFP and PEP12p:HA.Bars¼20m m.EPSIN1in Vacuolar Trafficking2263Figure 4.EPSIN1Binds to and Colocalizes with Clathrin.(A)Constructs.GST was fused to the N terminus.ENTH,the epsin N-terminal homology domain.DLF and DPF motifs are similar to AP-1and AP-3binding motifs,respectively.Q11indicates a stretch of 11Glu residues.The clathrin binding motif (LIDL)and the Leu-to-Arg substitution in the clathrin binding motif (RIDL)are shown in the C-terminal region.The numbers indicate amino acid positions.(B)Expression of GST-fused EPSIN1proteins.Constructs were introduced into E.coli ,and their expression was induced by isopropylthio-b -galactoside.GST fusion proteins were purified from E.coli extracts with glutathione–agarose beads.Purified proteins were stained with Coomassie blue.(C)Interaction of EPSIN1with clathrin.GST-fused EPSIN1proteins were mixed with protein extracts from leaf tissues.EPSIN1binding proteins were precipitated using glutathione–agarose beads and analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-clathrin antibody.Supernatants also were included in the protein gel blot analysis.Subsequently,the membranes were stained with Coomassie blue.Bead,glutathione–agarose beads alone;P,pellet;S,supernatant (10%of total).(D)Colocalization of EPSIN1with clathrin.Protoplasts transformed with HA:EPSIN1were fixed with paraglutaraldehyde,and the localization of HA:EPSIN1and clathrin was examined by immunostaining with anti-HA and anti-clathrin antibodies,respectively.Bar ¼20m m.2264The Plant CellEPSIN1Interacts with VTI11Epsin-related proteins in animal and yeast cells are involved in either endocytosis or vacuolar/lysosomal protein trafficking(Chen et al.,1998;De Camilli et al.,2002;Wendland,2002;Overstreet et al.,2003;Legendre-Guillemin et al.,2004).To elucidate the pathway of EPSIN1involvement,binding partners of EPSIN1 were examined.In animal and yeast cells,epsin-like proteins have been shown to interact with SNAREs(Chen et al.,1998; Chidambaram et al.,2004).Because EPSIN1localized to the Golgi complex and the PVC,EPSIN1interactions with Arabidop-sis VTI11and VTI12(formerly At VTI1a and At VTI1b,respectively) were examined.VTI11is a v-SNARE that localizes to the TGN and travels to the PVC(Zheng et al.,1999;Bassham et al.,2000). VTI11and VTI12were tagged with HA at the C terminus and introduced into protoplasts.The expression of VTI11:HA and VTI12:HA in protoplasts was confirmed by protein gel blot analysis using anti-HA antibody.The anti-HA antibody detected protein bands at33and35kD(Figure5A),the expected positions of VTI11:HA and VTI12:HA,respectively.Purified GST:EPSIN1 from E.coli extracts was mixed with plant extracts from the VTI11:HA-or VTI12:HA-transformed protoplasts,and GST: EPSIN1-bound proteins were precipitated from the mixture using glutathione–agarose beads.The pellet fraction was analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-HA antibody.VTI11:HA,but not VTI12:HA,was detected from the pellet(Figure5A).GST alone did not precipitate VTI11:HA from the plant extracts.These results indicated that although VTI11and VTI12are highly similar to each other,EPSIN1specifically binds to VTI11:HA.To further confirm this interaction,we performed a reciprocal protein pull-down experiment(i.e.,pull-down of EPSIN1with VTI11)using protein extracts obtained from protoplasts transformed with VTI11:HA and EPSIN1:GFP.VTI11:HA-bound proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody,and the immunopre-cipitates were analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-HA, anti-GFP,and anti-calreticulin antibodies.Anti-calreticulin anti-body was used as a negative control.In addition to VTI11:HA, EPSIN1:GFP was detected in the immunoprecipitates(Figure 5B).However,calreticulin was not detected in the pellet.These results further confirm the interaction between VTI11and EPSIN1. To determine the VTI11binding domain of EPSIN1,proteinpull-down experiments were performed using GST:ENTH and GST:EPSIN1D N.GST:ENTH,but not GST:EPSIN1D N,precipi-tated VTI11:HA from the plant extracts(Figure5C),indicating that the ENTH domain contained the VTI11binding motif.Similarly,in animal and yeast cells,EpsinR and Ent3p have been shown to bind to vti1b and vti1p,respectively(Chidambaram et al.,2004). EPSIN1Binds to the Arabidopsis Homolog of g-Adaptinof AP-1Epsin homologs bind to adaptor proteins(APs)(Duncan et al., 2003;Mills et al.,2003).In animal cells,EPSIN1binds to the a-adaptin of AP-2via the D F F/W(where F indicates a hydro-phobic amino acid)and FXDXF motifs(Figure4A)(Brett et al., 2002).Arabidopsis EPSIN1has three DPF motifs to which a-adaptin of AP-2could bind.In addition,EPSIN1has two regions with motifs similar to the acidic Phe motif for binding AP-1and GGAs(Duncan et al.,2003).Therefore,the interactions of EPSIN1with AP complexes were examined.We isolated the Arabidopsis proteins g-adaptin related protein(g-ADR),a-ADR, and d-ADR,which were most closely related to g-adaptin, a-adaptin,and d-adaptin of AP-1,AP-2,and AP-3,respectively. These Arabidopsis proteins were tagged with GFP and ex-pressed transiently in protoplasts.Protein extracts from the transformed protoplasts were mixed with purified GST:EPSIN1, and the GST:EPSIN1-bound proteins were precipitated.The pellet was analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-GFP antibody.GFP:g-ADR,but not a-ADR:GFP or d-ADR:GFP,was detected in the pellet(Figure6A).The control for the protein pull-down assay,GST alone,did not precipitate any of these proteins. These results strongly suggested that EPSIN1interacts with g-ADR specifically.To further confirm the interaction between EPSIN1and g-ADR,we performed a reciprocal protein pull-down experiment(i.e.,pull down of EPSIN1proteins with Figure5.EPSIN1Binds to VTI11.(A)Protein extracts were prepared from VTI11:HA-and VTI12:HA-transformed protoplasts and mixed with GST alone or GST:EPSIN1. EPSIN1-bound proteins were precipitated from the mixture with gluta-thione–agarose beads and analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-HA antibody.(B)Coimmunoprecipitation of EPSIN1:GFP with VTI11:HA.Protein ex-tracts from protoplasts cotransformed with VTI11:HA and EPSIN1:GFP were used for immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody.The immuno-precipitates were analyzed by protein gel blotting with anti-HA,anti-GFP, and anti-calreticulin antibodies.P,immunoprecipitate;S,supernatant;T, total protein extracts(5%of the input).(C)For binding experiments,protein extracts from protoplasts trans-formed with VTI11:HA were mixed with GST alone,GST:ENTH,and GST:EPSIN1D N.Proteins were precipitated with glutathione-agarose beads and analyzed by protein gel blotting using anti-HA antibody.The amount of the input proteins is indicated.EPSIN1in Vacuolar Trafficking2265。

生物英语证书考试(PEC)常用词汇AA band A带abasic site 脱碱基位点,无碱基位点abaxia l 远轴的abequo se 阿比可糖aberra nt splici ng 异常剪接aberra tion象差;失常abioge nesis自然发生论,无生源论ablast in 抑殖素[抑制微生物细胞分裂或生殖的一种抗体]abnorm al distri butio n 非正态分布abnorm al 异常,失常;畸形,跨变abrin相思豆毒蛋白ABO bloodgroupsystem ABO 血型系统aborig inalmouse原生鼠aborti n 流产素aborti on 流产,败育aborti ve egg 败育卵aborti ve infect ion 流产(性)感染aborti ve transd uctio n 流产(性)转导abscis ic acid(ABA) 脱落酸sbscis sion脱落absolu te 绝对的absolu te config urati on 绝对构垄absolu te counti ng 绝对测量absolu te deviat ion 绝对偏差accept or site 接纳位点,接受位点accept or splici ng site (=splice accept or) 剪接受体accept or stem [tRNA的]接纳茎access ible可及的access ble promot er 可及启动子access iblesurfac e 可及表面access ory 零件,附件;辅助的access ory cell 佐细胞access ory chromo some(≈supenu memra ry chromo sume)副染色体access ory factor辅助因子access ory nucleu s 副核access ory pigmen t 辅助色素access ory protei n 辅助蛋白(质〕accide nt variat ion 偶然变异accomm odati on 顺应accumu latio n 积累,累积accura cy 准确度acenap bthen e 二氢苊acene并苯acentr ic 无着丝粒的acentr ic-dicent ric transl ocati on无着丝粒-双着丝粒易位acentr ic fragme nt(=kineti c fragme nt) 无着丝粒断片acentr ic ring 无着丝粒环acetal缩醛acetal dehyd e 乙醛acetal resin缩醛树脂acetam idase乙酰胺酶acetam ide 乙酰胺acetat e 乙酸盐acetic acid(AcOH,HAc) 乙酸,醋酸acetic acid bacter ia 乙酸菌,醋酸菌acetic anhydr ile 乙酸酐acetif icati on 乙酸化作用,醋化作用acetin乙酸甘油酯,三乙酰甘油酯acetoa cetic acid 乙酰乙酸acetob acter醋杆菌属acetog en 产乙酸菌aoetog enicbacter ia 产乙酸菌aceton e 丙酮aceton e body(=ketone body)酮体aceton e/butano l fermen tatio n丙酮-丁醇发酵aceton e powder丙酮制粉[在-30℃以下加丙酮制成的蛋白质匀浆物] aceton itril e 乙睛acetyl(Ac) 乙酰基acetyl- DL-aminoacid 乙酰-DL-氨基酸2-acetyl amino fluor ene 2-乙酰氨基芴acetyl choli ne(Ach) 乙酰胆碱acetyl choHn e agonis t 乙酰胆碱拮抗剂acetyl choli ne steras e(AchE) 乙酰胆碱酯酶acetyl choli ne recept or(AchR)乙酰胆碱受体acetyl coenzy me A乙酰辅酶 Aacetyl ene 乙炔acetyl ene reduct ion test 乙炔还原试验[检查生物体的固氮能力]N-acetyl galac tosam ine(GalNAc) N-乙酰半乳糖胺.N-acetyl gluco samin e(GlcNAc)N-乙酰葡糖胺acetyl gluco samin idase乙酰葡垮胺糖苷酶acetyl gluta matesynthe tase乙酰谷氨酸合成酶N-acetyl muram yl acid N-乙酰胞壁酸N-acetyl muram yl pentap eptil e N-乙酰胞壁酰五肽N-acetyl neura minic acid(NeuNAc) N-乙酰神经氨酸acetyl salic ylate乙酰水杨酸;乙酰水杨酸盐,酯,根acetyl salic ylicacid(AsA) 乙酰水杨酸acctyl sapir amyci n 乙酰螺旋霉素achira l 非手性的achole plasm a 无胆甾原体[属名用Ach olepl asma]achrom atic消色的;消色差的achrom aticco1or无色achrom aticlens 消色差透镜achrom itin非染色质A chromo someA染色体[二倍体染色体组中的正常染色体(不同于B染色体)] acid 酸acid-base balanc e 酸碱平衡acid-base cataly sis 酸碱催化acid-base cataly zed reacti on酸碱催化反应acid-base equili brium酸碱平衡acid-base indica tor 酸碱指示剂acid-base metabo lism酸碱代谢acid-base titrat ion 酸碱滴定acid-base transi tion酸碱转换acid cataly sis 酸催化acid-fast staini ng 抗酸染色法acid fibrob lastgrowth factor酸性成纤维细胞生长因子acid fuchsi n 酸性品红acid glycop rotei n 酸性糖蛋白acid hydrol yzedcasein酸水解酪蛋白acidic酸性的acidic aminoacid 酸性氨基酸acidif icati on 酸化(作用)acidic protei n 酸性蛋白质[有时特指非组蛋白]acidic transa ctiva tor 酸性反式激活蛋白acidic transc ripti on activa tor 酸性转录激活蛋白acidif ying酸化(作用)acid medium酸性培养基acid mucopo lysac chari de 酸性粘多糖acidol ysis酸解acidop hilia嗜酸性acidop hilic bacter ia 嗜酸菌acidop hilou s milk 酸奶acid phosph atase酸性磷酸酶acid-produc ing bacter ia 产酸菌acid protea se(=aspart ic protea se) 酸性蛋白酶acid solven t 酸性溶剂aclaci nomyc in 阿克拉霉素activa tingtransc ripti on factor(A TF) 转录激活因子activa tion激活;活化activa tionanalys is 活化分析activa tionenergy活化能activa tor 激活物,激活剂,激活蛋白activa tor dissoc iatio n system Ac-Ds system) 激活解离系统activa tor protei n(AP) 激活蛋白active absorp tion主动吸收active biomas s 活生物质active carbon活性炭active center(=active site) 活性中心active chroma tin 活性染色质active dry yeast活性干酵母active esterof aminoacid 氨基酸的活化酯active hydrog en 活性氢active hydrog en compou nds 活性氢化合物active immuni ty 主动免疫active oxygen活性氧active site 活性部位,活性中心active transp ort 主动转运active uptake主动吸收activi n 活化素[由垂体合成并由睾丸和卵巢分泌的性激素]activi ty 活性,活度,(放射性)活度actomy osin肌动球蛋白actoph orin载肌动蛋白[一种肌动蛋白结合蛋白]acute急性的acuteinfect ion 急性感染acutephase急性期acutephaseprotei n(= acutephasereacti ve protei n) 急性期蛋白,急相蛋白acutephasereacti on 急性期反应,急相反应[炎症反应急性期机体的防御反应]acutephasereacti ve protei n 急性期反应蛋白,急相反应蛋白acutephaserespon se(=acutephasereacti on) 急性期反应,急相反应ac ute-phaseserum急性期血清acutetoxici ty 急性毒性acycli c nucleo tide无环核苷酸acyclo guano sine无环鸟苷,9-(2-羟乙氧甲基)鸟嚓呤acyclo vir(ACV)(=acyclo gua-nosme)无环鸟苷acyl 酰基acylam ino acid 酰基氨基酸acylas e 酰基转移酶acylat ion 酰化acylat ing agent酰化剂acyl azide酰叠氮acyl bromid e 酰溴acyl carrie r protei n(ACP) 酰基载体蛋白acyl cation酰(基)正离子acyl chlori de 酰氯acyl coenzy me A(acyl CoA)脂酰辅酶Aacyl fluori de 酰氟acyl halide酰卤acyloi n 偶姻acyltr ansfe rase酰基转移酶affini ty column亲和柱affini ty coupli ng 亲和偶联affini ty ectron micros copy亲和电镜(术)affini ty extrat ion 亲和提取,亲和萃取affini ty ltrati on 亲和过滤affini ty-isolat ed antibo dy 亲和分离的抗体affini ty labeli ng 亲和标记affini ty ligand苯和配体affini ty matura tion亲和力成熟[见于体液免疫系统的发育]affini ty partio ning亲和分配affini ty precip itati on 亲和沉淀affini ty purifi catio n 亲和纯化(法)affini ty tag (附加)亲和标记物aflato xin 黄曲霉毒素after-effect后效agar 琼脂agaras e 琼脂糖酶agar diffus ion test 琼脂扩散试验agarfi tine伞菌氨酸agar gel 琼脂胶agaric in 蘑菇素agaric inicacid 蘑菇酸agarop ectin琼脂胶agaros e 琼脂糖agaros e gel 琼脂糖凝胶agaros e gel electr ophor esis琼脂糖凝胶电泳agaros e plate琼脂糖平板agar plate琼脂平板agar slant琼脂斜面[固化时斜放的,装有固体培养基的一种试管培养基;也指斜面培养基上生长出的菌苔]agent剂;介质age pigmen t 老年色素agglut inati on 凝集(作用)agglut inin凝集素agglut inoge n凝集原aggrec an 聚集蛋白聚糖[来自软骨]aggreg ate 聚集体,凝聚体aggreg ation聚集(作用)aggres sin 攻击素[细菌分泌的一种有助于侵染宿主细胞的化学物质]aggres sivit y 攻击力aging衰老,老化,陈化agitat ion 振荡,振摇,搅拌agitat or 振荡器,搅拌器aglyco n(e) 苷元,糖苷配基agonis t 兴奋剂,激动剂,刺激物;竞争剂;拮抗剂agranu1ocyt e 无粒细胞agravi tropi sm 无向重力性agreto pe [抗原]限制位[抗原上识别并结合Ⅱ类主要组织相容性复合体的部位]agricu ltura l alcoho l 农产品(制)酒精agricu ltura waste农业废物,农业垃圾ag rin 集聚蛋白,集聚素[由运动神经分泌并可诱导肌纤维的乙酰胆碱酯酶和乙酰胆碱受体发生聚集]arachn oid 蛛网膜ara operon阿(拉伯)糖操纵子arbitr arily primed PCR 任意引物PC Rarbitr ation analys is (=refere e analys is) 仲裁分析arbovi rus 虫媒病毒arc 弧;电弧archen teron原肠archeo bacte ria 古细菌arches poriu m(=sporog omum)孢原细胞archit ectur e 结构,构造arenav irus沙粒病毒[斛名用are navir idae]argini nase精氨酸酶argini ne(Arg,R) 精氨酸argini ne-fork 精氨酸叉[与RNA的识别有关]argini ne vasopr essin (A vP)精氨酸升压素,精氨酸加压素8-argini ne vasoto cin(AvT)(=vasoto cin) 8-精催产素,8-精加压催产素argini nosuc cinic acid 精氨(基)琥珀酸argul(Ar) 氩aril 假种皮arithm eticaverag e deviat ion 算术平均偏差arithm eticmean 算术均数arm 臂[如染色体臂,噬菌体臂,连接臂等]arm ratio[染色体]臂比anmywo rm 粘虫[如草地贪夜蛾]arnold steamsteril izer流通蒸汽灭菌器aromat ic 芳香(族)的aromat ic aminoacid 芳香(族)氨基酸aromat ic compou nd 芳香(族)化合物aromat ic hydroc arbon芳(香)烃aromat ic hydroc arbon recept or(Ah recept or) 芳(香)烃受体array数组;列阵;一批arrest抑制;扣留;停滞arrest in [视紫红质]抑制蛋白[可与视紫红质结合,使其受体与转导素解偶联]Arrhen ius equati on 阿伦尼乌斯方程Arrhen ius theory阿伦尼乌斯理论Bbackgr ound背景,本底backgr oundabsorp tion背景吸收backgr oundabsorp tioncorrec tion背景吸收校正backgr oundcorrec tion背景校正baekgr oundfactor背景因子backgr oundgenoty pe 背景基因型[与所研究的表型直接相关的基因以外的全部基因] backgr oundhybrid izati on 背景杂交backgr oundradiat ion 背景辐射,本底辐射backmi xing反向混合bacter iosta sis抑菌(作用)bacter iosta t 抑菌剂bacter iotox in细菌毒素bacter iotro pin 亲菌素bacter ium(复:bacter ia) 细菌batero id 类菌体bacto-gar细菌培养用琼脂baculo virus杆状病毒bag sealer封边机bkersyeast面包酵母baking soda 小苏打balanc e 天平;平衡balanc ed hetero karyo n 平衡异核体balanc e lethal平衡致死balanc ed lethal gene 平衡致死基因balanc ed linkag e 平衡连锁balanc ed pathog enici ty 平衡致病性balanc ed polymo rphis m 平衡多态性balanc ed salt soluti on(Bss) 平衡盐溶液balanc ed soluti on 平衡溶液balanc ed transl ocati on 平衡易位H[低精度的三维结构实体模型]ball mill 球磨ball millin g 球磨研磨ball mill pulver izer球磨粉碎机balloo n cathet er 气囊导管[用于基因送递,如将DNA导人血管壁]BAL 31 nuclea se BAI,核酸酶banana bond 香蕉键band 条带,带[于电泳,离心等]band broade ning条带加宽bandin g patter n 带型bandin g techni que 显带技术,分带技术band sharpe ning条带变细,条带锐化band width带宽barbit urate巴比妥酸盐barium(Ba) 钡barlystripmosaic virus(BSMv)大麦条纹花叶病毒barlyyellow dwarfv irus(BYDv)大麦黄矮病毒barnas e 芽胞杆菌RN A酶[于解淀粉芽胞杆菌]baroph ilicbacter ia 嗜压菌barore cepto r 压力感受器barota xis 趋压性barotr oplis m 向压性bidire ction al promot er 双向启动子bidire ction l replic ation双向复制bidire ction l transc ripti on 双向转录bidire ction al transl ocati on 双向运输bienni al plant二年生植物bifunc tiona l agent双功能试剂bifunc tiona l antibo dy 双功能抗体bifunc tiona l cataly st 双官能催化剂,双功能催化剂bifunc tiona l initia tor 双官能引发剂,双功能引发剂bifunc tiona l interc alato r 双功能嵌人剂,双功能插入剂bifunc tiona l linker双功能接头bifunc tiona l vector双功能载体bifurc atedhydrog en bond 分叉氢键biglyc an 双糖链蛋白聚糖[有两条糖胺聚糖链] bibter al symmet ry 两侧对称,左右对称bilaye r 双层[时特指脂双层]bile acid 胆汁酸bile pigmen t 胆汁色素bile salt 胆汁盐bile salt micell e 胆汁盐微团,胆汁盐胶团,胆汁盐胶束Bili-[头]胆汁bilin胆汁三烯bilino gen 胆汁烷bilino gens后胆色素原类bilins后胆色素类biliru bin 胆红素biliru bin glucur onide胆红素葡糖苷酸bilive rdin胆绿素bimeta llicenzyme双金属酶bimole cular lipidmembra ne 双分子脂膜bimole cular reacti on 双分子反应bimole cmlar reduct ion 双分子还原(反应)Binary fissio n 二分裂bindin结合蛋白bindin g site 结合位点,结合部位binocu lar micros cope双目显微镜binoda l curve双结点曲线binomi al distri butio n 二项(式)分布binomi al nomenc latur e 双名法bioact ive molecu le 生物活性分子bioact ive peptid e 生物活性肽bioact ive polyme r 生物活性高分子,生物活性聚合物bioact ivity生物(学)活性bioami ne 生物胺bioass ay 生物测定,生物学鉴定(法)bioast ronau tics生物航天学bioaut ograp hy 生物自显影(法)BioBea ds resin[商] BioBea ds树脂[Bio-rad公司商品,可用于层析及多肽合成]BioBre ne soluti on [商] BioBre ne溶液[由Appli ed Bio-system s公司生产的一种Po ly-brene类聚卤化季铵盐的溶液biocab ina 生物舱biocat alysi s 生物催化biocat alyst生物催化剂biocer amic生物陶瓷bioche mical生化试剂,生化药品bioche mical engine ering生化工程bioche mical fuel cell 生化燃料电池bioche mical medium生化培养基bioche mical mutant生化突变体,生化突变型bioche mical oxygen demand(BOD) 生化需氧量bioche mical polymo rphis m 生化多态性bioche mistr y 生物化学biochi p 生物芯片biochr onome try 生物钟学biocid e 抗微生物剂,抗生剂biocli mate生物气候bioloc k 生物钟bicoen osis生物群落biocom munit y(=biocoe nosis) 生扬群落biocom puter生物计算机biocon trol=biolog icalcontro l)生铂防治;生物控制biocon trolsystem生物控制系统biocon versi on 生物转化[如利用微生物酶改造有机化合物的分子结构]biocos monau tics生物宇航学biocyb ernet ics 生物控制论biocyt in 生物胞素,ε-N-生物素-L-赖氨酸biodeg radab le (可被)生物降解的biodeg radab le plasti cs (可被)生物降解(的)塑料biodeg radat ion 生物降解(作用)biodeg radat ion pathwa y 生物降解途径biodet erior ation生物致劣(作用)[生物体的生命活动而造成物质的物理或化学性质改变及质量降低]biodiv ersit y 生物多样性Bio-Dotmic rofil trati on appara tus [商] Bio-Dot微置过滤装置[Bio-Rad公司商品,可用于蛋白质或核酸溶液的抽滤,并能使样品在滤膜上形成规则的斑点或狭线]bioele ctrem istry生物电化学bioele ctron ics 生物电子学bioene rgeti cs 生物能学bioeng ineer ing 生物工程(学)bioeth ics 生物伦理学[讨论生物学研究(如基因工程,器官移植等)所涉及的伦理问题]biofee dback生物反馈biofil ter 生物滤器Bonded phase键合相Bonded-phasechroma togra phy键合相层析bodedsilica键合硅bonded statio naryphase键合固定相Bondin g orbita l 成键轨道bondin g region键(合)区bond length键长bond moment键矩bond order键级bond srengt h 键强度bond valenc e 键价bond valenc e bond length corre-lation键长关联bone 骨,骨骼bone marrow骨髓bone marrow ceIl 骨髓细胞bone marrow stem cell 骨髓干细胞bone marrow transp lanta ion骨髓移植bone morpho genet ic protei n(BMP) 骨形态发生蛋白,骨形成蛋白booste r imuniz ation加强免疫borax硼砂bordet ella包特菌属bordet ellapertss is 百日咳杆菌boron(B) 硼borrel idin疏螺体素botany植物学bottle neck 瓶颈bott1e neck effect瓶颈效应bottom fermen tatio n 下面发酵bottom phase下相bottom yeast下面酵母botu1i nus toxin肉毒杆菌毒素bounda ry 边界;界面bounda ry elemen t 边界元件bounda ry layer边界层bounda ry lipid界面脂′bounda ry zone 界面区boundauxin束缚生长素boundwater结合水,束缚水bouque t stage花束期bovine牛bovine leukem ia virus(BLV)牛白血病病毒bovine pancea tic ribonu cleas e 牛胰RNA酶bovine pancre atictrypsi n inhibi ttor(BPTI) 牛胰胰蛋白酶抑制剂bovine papill omavi rus[BPV)牛乳头瘤病毒bovine serumalbumi n(BSA)牛血清白蛋白bovine spleen phosph odies teras e 牛脾磷酸二酯酶bovine viraldiarrh ea virus(BVDV) 牛病毒性腹泻病毒[归于黄病毒科瘟病毒属] Bowman-Birk protea se inhibi torBowman—Birk蛋白酶抑制剂[见于豆科植物种子]box 箱;匣,盒;框brachi onect in(= tenasc in) 臂粘连蛋白brady[词头] 缓慢bradyk inin缓激肽bradyk ininpotent iatin g peptid e缓激肽增强肽Braggangle布拉格角bulldo g clamp动脉夹bumble bee venom熊蜂毒bumpin g 暴沸,进沸bundle束bundle sheath (维管)束鞘bungar otoxi n 银环蛇毒紊Bunsen burner本生灯Bunsen cone 本生焰锥Bunsen eudiom eter本生量气管Bunsen f1ame本生焰bunyav irus布尼乎病毒[科名用Bun yavir idae]Bunyam weravirus布尼奥罗病毒buoyan t densit y 浮力密度buoyan t densit y centri fugat ion浮力密度离心buret滴定管buried residu es 隐蔽残基Burkit t lympho ma 伯基特淋巴瘤bursaof Fabric ius 法氏囊,腔上囊bursin法氏囊肽bursop oieti n(=bursin) 法氏囊生成素Ccalcit onin(CT) 降钙素alciut ouin-gene- relate d peptid e(CGRP)降钙素基因相关calici um(Ca) 钙calciu m bindin g protei n 钙结合蛋白(质)calciu m bindin g site 钙结合部位calciu m/calmod ulin—depend entprotei n kinase依赖(于)钙-钙调蛋白的蛋白激酶calciu m channe l 钙通道alcium chloHd e 氯化钙calciu m—depend ent neutra l protea se (=calpai n) 依赖(于)钙的中性蛋白酶calciu m-depend ent protei n 依(赖于)钙(的)蛋白(质)calciu m influx钙流入calciu m mediat ory protei n 钙中介蛋白(质)calciu m phoqha te 磷酸钙calciu m phosph ate prcipi tatio n磷酸钙沉淀calciu m phosph ate—DNA copre-cipita te 磷酸钙一DN A共沉淀物calciu m phosph ate-DNA copre-cipita tion磷酸钙→DNA共沉淀calciu m pump 钙氟calciu m sensor protei n 钙传感蛋白(质)calciu m seques trath n 集钙(作用)calcyc lin 钙(细胞)周期蛋白calcyp hosin e 钙磷蛋白[是依赖于cA MP的蛋白激酶的磷酸化底物]caldes mon 钙调(蛋白)结合蛋白[主要见于平滑肌,可与钙调蛋白及肌动蛋白结合]calele ctrin(=annexi nⅥ) 钙电蛋白[最初发现于鳗鱼电器官的一种钙结合蛋白Cal f intest inalalkali ne phosph atase(CIP)(小)牛小肠碱性磷酸酶calf serum小牛血清calfth ymus小牛胸腺calgra nulin钙粒蛋白calibr ation校准,标准calibr ation curve校正曲线calibr ation filter校准滤光片calibr ation protei n 校准蛋白calich eamyc im 刺孢霉素[来自刺孢小单胞菌的抗肿瘤抗生素,带有二炔烯官能团]calici virus杯状病毒[科名用Cal icivi ridae]callos e 胼胝质,愈伤葡聚糖,capsom er(e) (病毒)壳粒capsul ar polysa cchar ide 荚膜多糖capsul ation包囊化(作用),胶囊化(作用)capsul e 荚膜capsul e swelli ng reacti on 荚膜肿胀反应captur e 捕捉,俘获captur e antige n(=coatin g antige n) 捕捉抗原[酶免疫测定中用于捕捉抗体的抗原] captur e assay捕捉试验carbam yl 氨甲酰基carbam ylati on 氨甲酰化carbam yl ornith ine 氨甲酰鸟氨酸carbam ylpho sphat e 氨甲酰磷酸carbam yl phosph ate synthe tase氨甲酰磷酸合成酶carbam yl transf erase氨甲酰(基)转移酶carban ion 碳负离子carban yl group羰基cirben e 卡宾carben icill in 羧苄青霉素carben oid 卡宾体carboc ation碳正离子carbod iimid e 碳二亚胺carboh ydrat e 糖类,碳水化合物carboh ydrat e bindin g protei n糖结合蛋白carboh ydrat e finger print ing 糖指纹分析carboh ydrat e mappin g 糖作图,糖定位Carboh ydrat e-protei n intera cttio n 糖-蛋白质相互作用carboh ydrat e sequen cing糖测序carbol fuchsi n 石炭酸品红carbol ine 咔啉,二氮芴cirbon(C) 碳carbon assimi htion碳同化carbon ate 碳酸盐,碳酸酯carbon atedplant碳化植物carbon balanc e 碳平衡carbon cyclin g 碳循环carbon dioxid e 二氧化碳carbon dioxid e compen satio npoin t 二氧化碳补偿点carbon dioxid e fertil iatio n 二氧化碳施肥carbon dioxid e fixati on 二氧化碳固定carbon dioxid e tensio n 二氧化碳张力carbon fiber碳纤维carbon fixath n 碳固定carbon ic anhydr ase 碳酸酐酶carbon isotop e 碳同位素carbon isotop e analys is 碳同位素分析carbon isotop e compos ition碳同位素组成carbon ium ion 碳正离子carbon monoxi de 一氧化碳carbon source碳源carbon yl 羰基carbon ylati on 羰基化carbox ydism utase羧基歧化酶,核酮糖二磷酸羧化酶Carbox ydotr ophic bacter ia 二氧化碳营养菌基质相互作用Cell-mediat ed immuni nity(CMI)细胞(介导)免疫Cell mediat ed lympho cytot oxity细胞介导的淋巴细胞毒性cll membra ne (细)胞膜cll migrat ion 细胞迁移cll mobili ty 细胞运动性cell motili ty(= cell mobili ty)细胞运动性cell moveme nt 细胞运动cell mutati on 细胞突变cellob iose纤维二糖酶celloi se 纤维二糖cellob iuron ic acid 纤维二糖醛酸cello-oligos accha ride纤维寡糖cellos olve溶纤剂,纤溶剂cellot riose纤维三糖cell parame ters(=lattic e parame ters)晶胞参数cell permea biliz ntion细胞透化(作用)[使细胞的通透性增加lcell polari ty 细胞极性cell recogn ition细胞识别cell recycl e 细胞再循环[如见于发酵工艺]cell reposi tory(=cell bank) 细胞库cell respir ation细胞呼吸cell ruptur e 细胞破裂,细胞破碎cell rhythm细胞节律cell satter ing factor细胞分散因子cell scrape r 细胞刮棒cell senesc ence(=cell aging)细胞衰老cell shape细胞形状cell signal ing 细胞信号传导,细胞信号发放cell sociol ogy 细胞社会学cell sorter细胞分选仪cell sortin g 细胞分选cell strain细胞株[从原代培养或细胞系获得,具有特定性质或标志并在晦后培养期间始终保持]cell substr ain 细胞亚株cell substr ate attach ment细胞基底附着cell substr ate intera ction细胞-基底相互作用cell surfac e 细胞表面cell surfac e recept or 细胞表面受体cell surfac e recogn ition细胞表面识别cell target ing 细胞寻靶cell theory细胞学说cell therap y 细胞治疗[如LAK,TIL等方法]cell transf omati on 细胞转化cell tropis m 细胞嗜性cell typing细胞分型cellul ar 细胞的;微孔的cellul ar compar tment细胞区室cellul ar immuni ty 细胞免疫cellul ar immuno logy细胞免疫学cellul ar locali zatio n 细胞定位cellul ar materi al 微孔材料cellul ar oncoge ne(c-oncoge ne)细胞癌基因chemil umino metry化学发光分析(法)chemio smosi s 化学渗透chemio smoti c hypoth esis化学渗透假说chemio smoti c theory化学渗透理论chemis orpti on 化学吸附chemis try 化学chemo- [词头] 化学chemoa ttrac tant化学引诱物,化学吸引物,趋化物chemoa ttrac tingcytoki ne 趋化demilu minom etry化学发光分析(法)chemio smosi s 化学渗透chemio smoti c hypoth esis化学渗透假说chemio smoti c theory化学渗透理论chemis orpti on 化学吸附chemis try 化学chemo- [词头] 化学chemoa ttrac tant化学引诱物,化学吸引物,趋化物chemoa ttrac tingcytoki ne 趋化chemoo rgano troph y 化能有机营养chemor ecept ion 化学感受(作用)chemor ecept or 化学感受器chemor epell alt 化学排斥物chemos ensor y neuron感化性神经元chemos ensor y transd ucer感化性传导物chemos mosis(=chemio smosi s)化学渗透chemos tat 恒化器chemos tat cultur e 恒化培养(物)chemos ynthe sis 化能合成chemot actic cytoki ne 趋化细胞因子chemot actic factor趋化因子chemot actic lipid趋化脂质chemot actic peptid e 趋化肽chemot actic repell ant 化学拒斥剂chemot axin趋化因子,趋化物che motax is 趋化性[(细胞)随环境中化学物质的分布梯度作定向运动]chemot herap eutan t 化疗剂chemot herap eutic agent化疗剂chemot herap eutic s 化疗药物chemot herap y 化疗,化学疗法ch emotr ophy化能营养chemot ropis m 向化性[因环境中化学物质的浓度梯度而引起细胞的定向生长]chemot ype 化学型chemov ar 化学变型chromo somal disord er 染色体病chromo somal DNA染色体DNAchromo somal domain染色体结构域chromo somal elimin ation染色体丢失,染色体消减chromo somal locali zatio n 染色体定位chromo somaI mutati on 染色体突变chromo somaI patter n 染色体型chromo somal poIymo rphis m 染色体多态性chromo somal puff 染色体胀泡,染色体疏松chromo somal rearra ngeme nt染色体重排chromo somal scaffo ld 染色体支架chromo some染色体chromo someaberra tion染色体畸变chromo someabnorm alty染色体异常chromo somearm 染色体臂chromo someband 染色体带chromo somebandin g techni que染色体显带技术chromo someblotti ng 染色体印迹[通过脉冲电场凝胶电泳分离染色体D NA并进行South ern印迹]chromo somebreaka ge 染色体断裂chromo somebridge染色体桥chromo somecenter(=chromo cente r) 染色中心chromo somecoilin g 染色体螺旋chromo somecomple ment染色体组chromo somecore 染色体轴chromo somecrawli ng 染色体缓移chromo somecycle染色体周期c hromo somedamage染色体损伤chromo somedeleti on 染色体缺失chromo somedoubbl ing 染色体加倍chromo somedublic ation染色体重复chromo someelimin ation染色体丢失,染色体消减chromo someengine ering染色体工程(学)chromo someevolut ion 染色体进化chromo someexchan ge 染色体交换chromo someflow sortin g 染色体流式分选(法)chromo somefragme ntati on 染色体断裂chromo somefusion染色体融合chromo somegap 染色体间隙,染色体裂隙chromo someinterc hange染色体互换chromo somejumpin g 染色体跳查conden ser 冷凝器;聚光器conden singagent凝聚剂[大分子群集作用的促进剂]缩合剂[缩合反应的催化剂];冷凝剂condit ion 条件condit ional cytoto xic 条件致细胞毒condit ional lethal条件致死condit ional lethal mutant条件致死突变体,条件致死突变型condit ional lethal mutati on 条件致死突变condit ional mutant条件突变体,条件突变型,条件突变株condit ional mutati on 条件突变condit ioned medium条件培养基,条件培养液condit iomdpathog en 条件致病菌,条件致病病原体condit ionin g 调节,调理,再生conduc tion传导conduc tivit y 电导率,导电率;导电性;传导率;传导性conduc tivit y detect or 电导率检测器conduc tivit y water电导水comduc tomet er 电导计conduc tomet ric titrat ion 电导滴定(法)conduc tomet ry 电导分析(法)cone 锥,圆锥体cone and plateviscom eter锥板式粘度计confde nce coefti cient置信系数confde ng interv al 置信区间confid encelimit置信限config urati on 构型confgu ratio nal disord er 构型无序confgu ratio nal unit 构型单元confir mator y sequen cing确证性测序,证实性测序confir mator y test 确证试验,证实试验conflu ent 汇合的,融合的,连生的,铺满的conflu ent cultiv ation铺满培养conflu ent cultur e 铺满培养物,铺满培养conflu ent monola yer cells(汇合)成片的单层细胞,铺满的单层细胞confor matio n 构象confor matio nal analys ls 构象分析confor matio nal change构象变化confor matio nal detemi nant构象(性)决定簇confor matio nal disord er 构象无序confor matio nal epitop e 构象(性)表位confor matio nal invers ion 构象反转confor matio nnl repeat ing unit构象重复单元confor matio nal restri ction构象限制(性)confor matio nal simila rity构象相似性confor matio nal switch构象转换(器),构象开关confor matio nal witchi ng 构象转换crosslink 交联;交联键cross-linked交联的cross-linked gel 交联凝胶cross-linked networ k 交联网络coss-linked polyme r(=threedimens ional polyme r) 交联聚合物crossl inker交联剂crossl inkin g 交联crosdi nking agent交联剂crossl inHng densit y 交联密度crossl inkin g group交联基crossl inkin g index交联指数crossmatchi ng 交叉配血(试验)crossneutra1izat ion 交叉中和crossv er flixat ion交换固定crossv er suppre ssor交换抑制因子crossv er unit 交换单位crossv er value交换值coss phosph oryla tion交叉磷酸化crosspollin ation异体受粉,异花传粉crossprotec tion交叉保护cross-reacti ng antibo dy 交叉反应抗体cross-reacti ng antige n 交叉反应抗原cross-reacti ng determ inant(CRD) 交叉反应决定簇crossreacti on 交叉反应crossreacti vatio n 交叉复活crossregula tion交叉调节,交互调节crosssectio n 截面,横切面cross-steril ity 杂交不育,杂交不育性crosst alk 串话,通讯crotap olin(= crotox in A) 响尾蛇毒素Acrotin巴豆毒蛋白crotox in 响尾蛇毒素crowngall 冠瘿crowngall nodule冠瘿瘤crucib le 坩埚crucif oml 十字形,十字形结构crucif oml loop 十字形环[双股反向重复序列的每一股分别自我配对而形成] crucif orm struct ure 十字形结构crude粗的,粗制的crudeextrac t 粗提物crudeproduc t 粗制品crusta cyani n 虾青蛋白,甲壳蓝蛋白cryo-[词头]冷,冻cryobi o1ogy低温生物学cryoco ncent ratio n 低温浓缩cryocr ystal1ogra phy 低温晶体学cryoel ectro n micros copy冷冻电(子显微)镜术cryofi xatio n 冷冻固定cryoge n 冷冻剂,制冷剂cryoge nic g1ove低温防护手套cryoge nic purifi catio n 深低温纯化cryoge nic refrig erato r 低温冰箱cryoge nics低温实验法cryoge nic separa tion深低温分离cytopl asmic region胞质区[如指跨膜蛋白的胞内区]cytopl asmic stream ing(=cyclos is) 胞质环流cytopl asmic tall 胞质尾区[如指跨膜蛋白的胞内小区]cytopl asm IgM 胞质IgM,胞质免疫球蛋白Mcytopl ast 胞质体cytorh eolog y 细胞流变学cytoso l 胞质溶胶cytoso lic locali zatio p. 胞质定位cytoso lic space胞质腔cytoso l recept or 胞质受体cytoso me(=cytopl ast) 胞质体cytost aticfactor细胞静止因子cytota ctin(=tenasc in) 腱生蛋白cytoto xic 细胞毒的cytoto xicit y 细胞毒性cytoto xic T cell(Tc)(=cytoto xic T lympho cyte)细胞毒性T细胞cytoto xic T lympho cyte(CTL,Tc) 细胞毒性Υ淋巴细胞cytoto xin 细胞毒素cytotr opism细胞向性cytovi llin细胞绒毛蛋白[见于微绒毛,可作用于肌动蛋白丝]Ddalton道尔顿[符号D,Da]dammar ane 达玛烷dammar anety pe 达玛烷型Dane partic le 丹氏粒[型肝炎病毒的完整毒粒]danger ous 危险的dansyl丹(磺)酰,l-二甲氨基萘—5-磺酰dansyl chlor ide 丹磺酰氯dansyl method丹磺酰法dantro lene硝苯呋海因[肉松弛剂]dark curren t 暗电流dark field暗视野,暗视场dark-fieldmicros cope暗视野显微镜,暗视场显微镜dark-fieldmicros copy暗视野显微术,暗视场显微术dark reacti on 暗反应dark repair暗修复dark respir ation暗呼吸dark room 暗室,晴房dark seed 需暗种子data(单:datum)数据,资料data accumu latio n 数据累积data acquis ition数据获取decidu ous leaf 落叶declin e phase细胞生长曲线的衰亡期decoag ulant(= antico agula nt)抗凝剂decodi ng 译码,解码decomp oser分解者指具有分解动植物残体或其排泄物能力的微生物: decomp ressi on 降压,减压decond ensat ion 解凝(聚)decont amina nt 净化剂,去污剂decont amina tingagent(=decont amina nt) 净化剂,去污剂decont amina tion净化,去污decori n 核心蛋白聚糖[一种基质蛋白聚糖,又称为PG-40]dediff erent iatio n 去分化,脱分化deep∞lony深层菌落deep etchin g 深度蚀刻deep refrig erati on 深度冷冻deep—shaftairlif t fermen tor 深井气升式发酵罐deep shaftsystem深井系统dretio latio n 去黄化,脱黄化defect ive interf ering(DI) 缺损干扰defect ive mufant缺损突变体,。

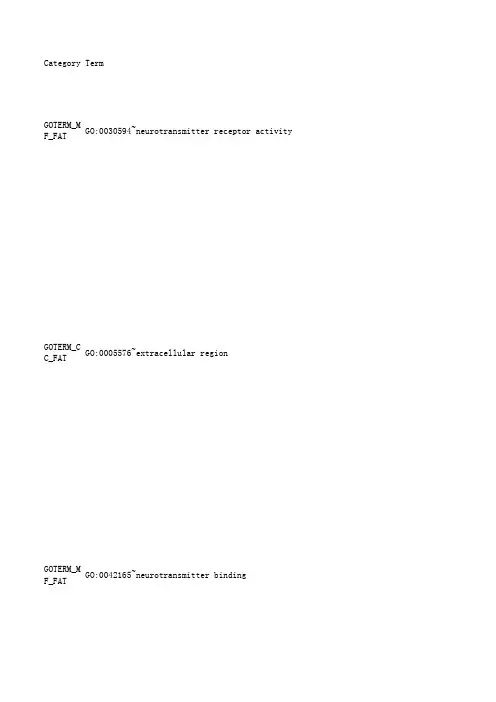

Category TermGOTERM_MF_F GO:0030594~neurotransmitter receptor activityGOTERM_CC_F GO:0005576~extracellular regionGOTERM_MF_F GO:0042165~neurotransmitter bindingGOTERM_MF_F GO:0008188~neuropeptide receptor activityGOTERM_MF_F GO:0042923~neuropeptide bindingGOTERM_CC_F GO:0044421~extracellular region partGOTERM_MF_F GO:0032403~protein complex bindingKEGG_PATHWA hsa04080:Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction GOTERM_CC_F GO:0005615~extracellular spaceGOTERM_CC_F GO:0005886~plasma membraneGOTERM_CC_F GO:0045177~apical part of cellGOTERM_BP_F GO:0042981~regulation of apoptosisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0010033~response to organic substanceGOTERM_BP_F GO:0043067~regulation of programmed cell death GOTERM_BP_F GO:0010941~regulation of cell deathGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005319~lipid transporter activityGOTERM_CC_F GO:0044459~plasma membrane partGOTERM_BP_F GO:0043434~response to peptide hormone stimulusKEGG_PATHWA hsa04960:Aldosterone-regulated sodium reabsorption GOTERM_BP_F GO:0010876~lipid localizationGOTERM_BP_F GO:0006111~regulation of gluconeogenesisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0032868~response to insulin stimulusGOTERM_BP_F GO:0048585~negative regulation of response to stimulus GOTERM_MF_F GO:0005200~structural constituent of cytoskeleton GOTERM_BP_F GO:0060173~limb developmentGOTERM_BP_F GO:0048736~appendage developmentGOTERM_BP_F GO:0051094~positive regulation of developmental process GOTERM_BP_F GO:0001501~skeletal system developmentGOTERM_BP_F GO:0042445~hormone metabolic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0007155~cell adhesionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0022610~biological adhesionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0009719~response to endogenous stimulusGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005158~insulin receptor bindingGOTERM_BP_F GO:0006869~lipid transportGOTERM_MF_F GO:0008528~peptide receptor activity, G-protein coupled GOTERM_MF_F GO:0001653~peptide receptor activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0009991~response to extracellular stimulusGOTERM_BP_F GO:0006790~sulfur metabolic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0040008~regulation of growthGOTERM_BP_F GO:0010817~regulation of hormone levelsGOTERM_BP_F GO:0007610~behaviorGOTERM_BP_F GO:0060429~epithelium developmentGOTERM_BP_F GO:0030326~embryonic limb morphogenesisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0035113~embryonic appendage morphogenesisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0007242~intracellular signaling cascadeGOTERM_BP_F GO:0048598~embryonic morphogenesisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0034754~cellular hormone metabolic processGOTERM_MF_F GO:0043168~anion bindingGOTERM_BP_F GO:0019932~second-messenger-mediated signaling GOTERM_BP_F GO:0031667~response to nutrient levelsGOTERM_BP_F GO:0010906~regulation of glucose metabolic process KEGG_PATHWA hsa00980:Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 GOTERM_BP_F GO:0015698~inorganic anion transportGOTERM_CC_F GO:0005887~integral to plasma membraneGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005496~steroid bindingGOTERM_CC_F GO:0016324~apical plasma membraneGOTERM_BP_F GO:0002366~leukocyte activation during immune responseGOTERM_BP_F GO:0002263~cell activation during immune responseGOTERM_BP_F GO:0019218~regulation of steroid metabolic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0008202~steroid metabolic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0045321~leukocyte activationGOTERM_MF_F GO:0015247~aminophospholipid transporter activityGOTERM_MF_F GO:0004012~phospholipid-translocating ATPase activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0051240~positive regulation of multicellular organismal process GOTERM_MF_F GO:0003700~transcription factor activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0010675~regulation of cellular carbohydrate metabolic process GOTERM_BP_F GO:0032870~cellular response to hormone stimulusGOTERM_BP_F GO:0035107~appendage morphogenesisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0035108~limb morphogenesisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0006109~regulation of carbohydrate metabolic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0010627~regulation of protein kinase cascadeGOTERM_BP_F GO:0048568~embryonic organ developmentGOTERM_BP_F GO:0048732~gland developmentGOTERM_CC_F GO:0031226~intrinsic to plasma membraneGOTERM_MF_F GO:0043565~sequence-specific DNA bindingGOTERM_BP_F GO:0006955~immune responseGOTERM_BP_F GO:0050796~regulation of insulin secretionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0030855~epithelial cell differentiationKEGG_PATHWA hsa04115:p53 signaling pathwayGOTERM_BP_F GO:0042493~response to drugGOTERM_BP_F GO:0007584~response to nutrientGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005179~hormone activityGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005275~amine transmembrane transporter activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0046631~alpha-beta T cell activationGOTERM_BP_F GO:0006952~defense responseGOTERM_MF_F GO:0008509~anion transmembrane transporter activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0043408~regulation of MAPKKK cascadeGOTERM_BP_F GO:0046626~regulation of insulin receptor signaling pathway GOTERM_BP_F GO:0008206~bile acid metabolic processGOTERM_MF_F GO:0031404~chloride ion bindingGOTERM_BP_F GO:0046890~regulation of lipid biosynthetic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0046942~carboxylic acid transportGOTERM_BP_F GO:0015849~organic acid transportGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005198~structural molecule activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0043066~negative regulation of apoptosisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0002791~regulation of peptide secretionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0019216~regulation of lipid metabolic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0045597~positive regulation of cell differentiationGOTERM_BP_F GO:0043069~negative regulation of programmed cell deathGOTERM_BP_F GO:0030900~forebrain developmentGOTERM_MF_F GO:0050698~proteoglycan sulfotransferase activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0045927~positive regulation of growthGOTERM_BP_F GO:0060548~negative regulation of cell deathGOTERM_BP_F GO:0043255~regulation of carbohydrate biosynthetic process GOTERM_BP_F GO:0016337~cell-cell adhesionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0015837~amine transportGOTERM_BP_F GO:0035136~forelimb morphogenesisGOTERM_BP_F GO:0009725~response to hormone stimulusGOTERM_BP_F GO:0015718~monocarboxylic acid transportGOTERM_BP_F GO:0032102~negative regulation of response to external stimulus GOTERM_CC_F GO:0034702~ion channel complexGOTERM_BP_F GO:0042127~regulation of cell proliferationGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005184~neuropeptide hormone activityGOTERM_MF_F GO:0008083~growth factor activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0007398~ectoderm developmentGOTERM_BP_F GO:0050864~regulation of B cell activationGOTERM_BP_F GO:0032101~regulation of response to external stimulus GOTERM_MF_F GO:0042277~peptide bindingGOTERM_BP_F GO:0009954~proximal/distal pattern formationGOTERM_CC_F GO:0034707~chloride channel complexGOTERM_BP_F GO:0001775~cell activationGOTERM_BP_F GO:0006469~negative regulation of protein kinase activity GOTERM_BP_F GO:0048015~phosphoinositide-mediated signalingGOTERM_CC_F GO:0070161~anchoring junctionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0007160~cell-matrix adhesionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0050810~regulation of steroid biosynthetic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0051048~negative regulation of secretionKEGG_PATHWA hsa04510:Focal adhesionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0033673~negative regulation of kinase activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0045893~positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent GOTERM_BP_F GO:0007586~digestionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0030166~proteoglycan biosynthetic processGOTERM_BP_F GO:0010565~regulation of cellular ketone metabolic process GOTERM_MF_F GO:0030674~protein binding, bridgingGOTERM_BP_F GO:0051254~positive regulation of RNA metabolic process GOTERM_BP_F GO:0008283~cell proliferationGOTERM_CC_F GO:0031224~intrinsic to membraneGOTERM_MF_F GO:0015294~solute:cation symporter activityGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005178~integrin bindingGOTERM_MF_F GO:0015171~amino acid transmembrane transporter activityKEGG_PATHWA hsa05110:Vibrio cholerae infectionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0048562~embryonic organ morphogenesisGOTERM_MF_F GO:0015184~L-cystine transmembrane transporter activity GOTERM_MF_F GO:0004994~somatostatin receptor activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0051348~negative regulation of transferase activity GOTERM_MF_F GO:0015293~symporter activityGOTERM_MF_F GO:0005548~phospholipid transporter activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0035295~tube developmentGOTERM_BP_F GO:0040014~regulation of multicellular organism growth GOTERM_BP_F GO:0006821~chloride transportGOTERM_CC_F GO:0005925~focal adhesionGOTERM_CC_F GO:0044437~vacuolar partGOTERM_BP_F GO:0051272~positive regulation of cell motionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0031589~cell-substrate adhesionGOTERM_BP_F GO:0005996~monosaccharide metabolic processGOTERM_CC_F GO:0032839~dendrite cytoplasmGOTERM_BP_F GO:0030879~mammary gland developmentKEGG_PATHWA hsa04910:Insulin signaling pathwayGOTERM_BP_F GO:0009952~anterior/posterior pattern formationGOTERM_MF_F GO:0022803~passive transmembrane transporter activityGOTERM_MF_F GO:0000099~sulfur amino acid transmembrane transporter activityGOTERM_BP_F GO:0008285~negative regulation of cell proliferation GOTERM_BP_F GO:0048537~mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue development GOTERM_BP_F GO:0048541~Peyer's patch developmentGOTERM_BP_F GO:0032148~activation of protein kinase B activity GOTERM_BP_F GO:0045471~response to ethanolCount%PValue Genes List Total P op Hits Pop TotalFold Enrich Bonferroni90.309278 2.18E-04SSTR4, SSTR2239512983 5.5155530.1011154 1.85567 3.28E-04F2RL3, OBP2214201012782 1.6046590.07239590.309278 3.80E-04SSTR4, SSTR223103129835.0871610.16936760.206186 5.65E-04SSTR4, SSTR22340129838.732960.24089360.206186 6.34E-04SSTR4, SSTR22341129838.5199610.26624830 1.0309280.001284MIA, IL19, 21496012782 1.866530.254915110.3780070.002009PDPK1, LAMB223196129833.2674340.625121 130.4467350.002026CCKAR, F2RL9325650852.7765880.208053 230.7903780.002411MIA, LY96, 214685127822.0054980.42467383 2.8522340.002953F2RL3, KCNC2143777127821.3125510.491962100.3436430.003091SLC26A4, MU214179127823.3368140.507811 260.8934710.003409GRIK2, STAT236804135281.8536980.998133 240.8247420.003618STAR, LYN, 236721135281.9080840.998731 260.8934710.003874GRIK2, STAT236812135281.8354350.999208 260.8934710.004061GRIK2, STAT236815135281.8286780.9994460.2061860.004392STAR, ATP1022363129835.5447360.88327153 1.8213060.004614CCKAR, KCNC2142203127821.4369660.653290.3092780.005479LEP, PDPK1,236154135283.3499890.99995950.1718210.006094PDPK1, INS,934150856.6679780.50488790.3092780.00614SOAT2, STAR236157135283.2859760.99998830.1030930.007853LEP, INS, N23681352821.495760.99999970.240550.007916LEP, PDPK1,236100135284.012542170.240550.007916LEP, GRB10,236100135284.012542160.2061860.008658TNNT2, CYLC22374129834.7205190.9856470.240550.009099MSX1, RAX, 236103135283.895672170.240550.009099MSX1, RAX, 236103135283.8956721120.4123710.009414LEP, MYOD1,236278135282.4743321 130.4467350.009834HOXD12, IGF236319135282.336008170.240550.010403LEP, UGT1A6236106135283.7854171220.7560140.010459MIA, ICAM4,23670013528 1.801551 220.7560140.010621MIA, ICAM4,23670113528 1.798981 150.5154640.011321LYN, STAR, 236405135282.123038140.1374570.011792PDPK1, GRB122328129838.3171040.99693880.2749140.013349SOAT2, STAR236145135283.162595170.240550.013507SSTR4, SSTR223114129833.5748960.99868870.240550.013507SSTR4, SSTR223114129833.5748960.998688100.3436430.014702LEP, MUC1, 236220135282.605547170.240550.015105GAL3ST3, GG236115135283.4891671130.4467350.016195MYOD1, SOCS236341135282.185297180.2749140.01636LEP, UGT1A6236151135283.0369291160.5498280.017162CCKAR, PRLH236469135281.9555491 100.3436430.017644PSPN, KRT5,23622713528 2.5252160.2061860.017706MSX1, HOXD123687135283.953244160.2061860.017706MSX1, HOXD123687135283.953244133 1.1340210.017786CCKAR, F2RL2361256135281.5060731120.4123710.018564MSX1, ALDH123630713528 2.240601150.1718210.019177UGT1A6, AKR2365913528 4.857799160.2061860.020689SLC26A4, FX2239212983 3.7969390.999963100.3436430.021541SSTR4, SSTR23623513528 2.439235190.3092780.021594LEP, MUC1, 23619713528 2.618773140.1374570.022508LEP, INS, I2363513528 6.55109150.1718210.022643UGT1A6, AKR93605085 4.5564520.92819660.2061860.022927SLC26A4, FX2369313528 3.698196130 1.0309280.023479KCNC1, CCKA214118812782 1.5083070.995664 50.1718210.023795SOAT2, STAR2236412983 4.5484160.999992 70.240550.02388SLC26A4, MU21413312782 3.143630.996053 40.1374570.024247LYN, TICAM123636135286.3691151 40.1374570.024247LYN, TICAM123636135286.3691151 40.1374570.024247LEP, STAR, 23636135286.3691151 90.3092780.024696LEP, SOAT2,236202135282.5539521 100.3436430.02566DOCK2, SPAC236242135282.3686791 30.1030930.0264ATP10A, ATP223151298311.643950.999998 30.1030930.0264ATP10A, ATP223151298311.643950.999998 100.3436430.026524IL27RA, GRI236244135282.3492641 260.8934710.027175MYOD1, ELF5223975129831.5525260.999999 40.1374570.027937LEP, INS, I23638135286.0338981 70.240550.028558PDPK1, GRB1236133135283.0169491 60.2061860.029056MSX1, HOXD123699135283.4740631 60.2061860.029056MSX1, HOXD123699135283.4740631 40.1374570.029887LEP, INS, I23639135285.8791831 100.3436430.030289LEP, LYN, G23624913528 2.302091 80.2749140.030383ALDH1A3, HO236172135282.6661411 70.240550.03042SLC6A3, ALD236135135282.9722541 30 1.0309280.030497KCNC1, CCKA2141215127821.4747890.999169 180.6185570.031472MYOD1, RAX,22360712983 1.726451 200.6872850.031889GBP6, IL27R236690135281.6615081 40.1374570.031908LEP, SSTR5,23640135285.7322031 70.240550.032361KRT5, UPK1B236137135282.9288631 50.1718210.033932SERPINB5, C936850854.0203980.981124 90.3092780.034702UGT1A6, STA236216135282.3884181 70.240550.03542MUC1, SOAT2236140135282.8661021 60.2061860.037789LEP, PENK, 223108129833.2344291 50.1718210.037825SLC6A3, SLC22374129833.9337661 30.1030930.038294DOCK2, INS,23618135289.5536721 180.6185570.039646SPACA3, IL2236615135281.6777181 70.240550.040545SLC26A4, FX223147129832.7723681 60.2061860.041391LEP, GRIK2,236109135283.1553411 30.1030930.042319GRB10, SOCS23619135289.0508471 30.1030930.042319LEP, STAR, 23619135289.0508471 50.1718210.042789SLC26A4, FX22377129833.7805021 40.1374570.043048LEP, STAR, 23645135285.0952921 70.240550.043265AKR1C4, SLC236147135282.7296211 70.240550.044468AKR1C4, SLC236148135282.7111771 180.6185570.044518GFAP, CLDN6223634129831.6529261 120.4123710.045237CDH13, MSX123635413528 1.943121 40.1374570.045481LEP, SSTR5,23646135284.9845251 60.2061860.045623LEP, STAR, 236112135283.0708231 90.3092780.046272LEP, STAR, 236229135282.2528311 120.4123710.048926CDH13, MSX1236359135281.9160571 70.240550.049487SALL3, CCKA23615213528 2.6398311 20.0687290.05043GAL3ST3, CH22331298338.813151 50.1718210.050468MYOD1, INS,2368013528 3.5826271 120.4123710.050662CDH13, MSX123636013528 1.9107341 30.1030930.050814LEP, INS, N23621135288.1888621 100.3436430.05144CDH8, CDH1323627613528 2.0768851 60.2061860.054838LYN, SLC6A323611813528 2.914681 30.1030930.055271HOXA9, ALX423622135287.8166411120.4123710.055727LEP, UGT1A623636713528 1.87429140.1374570.055872AKR1C4, SLC2365013528 4.585763140.1374570.055872LEP, INS, S2365013528 4.5857631 80.2749140.05613KCNC1, FXYD214205127822.3308870.999998 210.7216490.056536TP53I11, LY236787135281.5295591 30.1030930.058206PENK, IGF1,22323129837.5938781 70.240550.058289LEP, MIA, P223161129832.5312931 80.2749140.058352LAMB3, KRT1236199135282.3044031 40.1374570.058632IL27RA, STA23651135284.4958461 70.240550.059079LEP, MYOD1,236159135282.5236121 80.2749140.059787SSTR4, SSTR223203129832.2943741 30.1030930.059859HOXA10, HOX23623135287.4767871 40.1374570.063673FXYD3, GABR21455127824.3439251 100.3436430.064492DOCK2, SPAC236287135281.9972831 50.1718210.0648CBLC, PDPK12368713528 3.294371 50.1718210.067004F2RL3, CCKA23688135283.2569341 70.240550.067994TNS4, ARHGA21417212782 2.430831 50.1718210.069246MIA, PDPK1,23689135283.2203391 30.1030930.069408LEP, STAR, 23625135286.8786441 40.1374570.070294INS, TRH, K23655135284.1688751 80.2749140.070485PDPK1, LAMB9320150852.1762160.999776 50.1718210.071527CBLC, PDPK123690135283.1845571 140.48110.073482MYOD1, UTF1236477135281.6824081 50.1718210.073846SOAT2, CCKA23691135283.1495621 30.1030930.074357GAL3ST3, IG23626135286.6140811 40.1374570.076487LEP, INS, F23657135284.0225991 50.1718210.07745ARHGAP4, SH22394129833.0967941 140.48110.077868MYOD1, UTF1236481135281.6684171 130.4467350.078951MIA, SOX11,236436135281.7091431 103 3.5395190.079701KCNC1, F2RL214548512782 1.121621 50.1718210.079825SLC6A3, SLC22395129833.0641961 40.1374570.079917ICAM4, LYN,2235912983 3.94711 40.1374570.079917SLC6A6, SLC2235912983 3.94711 40.1374570.080017KDELR2, CFT93565085 3.905530.999932 60.2061860.082235ALDH1A3, HO236133135282.5859561 20.0687290.082634SLC3A1, SLC22351298323.287891 20.0687290.082634SSTR4, SSTR22351298323.287891 50.1718210.086003CBLC, PDPK123696135282.9855231 60.2061860.086016SLC6A3, SLC223137129832.5497691 30.1030930.087449ATP10A, ATP22329129836.0227311 80.2749140.088577TNS3, PSPN,236220135282.0844381 40.1374570.08956LEP, SLC6A323661135283.7588221 40.1374570.08956FXYD3, SLC123661135283.7588221 50.1718210.090722TNS4, ARHGA214102127822.9278911 40.1374570.090919CD1B, SLC3A21464127823.7330611 50.1718210.091123CDH13, LYN,23698135282.924594150.1718210.091123MIA, PDPK1,2369813528 2.924594180.2749140.091661LEP, GAL3ST23622213528 2.065659120.0687290.095928GRIK2, ADA21461278219.90966140.1374570.096424SLC6A3, STA2366313528 3.639494160.2061860.096698CBLC, PDPK1931355085 2.4301080.99999260.2061860.097105HOXD4, GATA23614013528 2.4566591 120.4123710.097719KCNC1, FXYD22341312983 1.691614120.0687290.098327SLC3A1, SLC22361298319.406581110.3780070.098867SSTR4, SSTR23636113528 1.7466551 20.0687290.099823STAT5A, ADA23661352819.107341 20.0687290.099823STAT5A, ADA23661352819.107341 20.0687290.099823PDPK1, INS23661352819.107341 40.1374570.099934UGT1A6, STA23664135283.5826271BenjaminiFDR0.101110.312985 0.0723950.419542 0.0886090.544235 0.0877770.807252 0.0744770.906301 0.136817 1.632758 0.178177 2.844165 0.208053 2.283971 0.168291 3.045419 0.155744 3.717749 0.132187 3.888317 0.998133 5.648121 0.964382 5.985058 0.907493 6.394447 0.846179 6.694047 0.300916 6.121242 0.161802 5.752565 0.867578.929442 0.296358 6.726075 0.8487329.9548110.874112.56065 0.8392712.65639 0.8392712.65639 0.45457311.73161 0.84568914.41237 0.84568914.41237 0.82455614.87464 0.80853615.48624 0.79881116.30995 0.77421316.39046 0.75422516.6227 0.75257617.62194 0.51498315.65308 0.7867820.45138 0.52162717.72979 0.52162717.72979 0.79873222.2892 0.78897922.82763 0.79427124.26952 0.78075724.48558 0.78057325.52647 0.77436526.1461 0.76048926.22545 0.76048926.22545 0.74738926.32854 0.7482127.31526 0.74597828.08446 0.63948725.92044 0.77327230.97879 0.76178531.04273 0.76412132.13175 0.58436222.96278 0.7589132.62540.5403326.24218 0.65643729.22134 0.49935326.62952 0.7670534.15834 0.7670534.15834 0.7670534.15834 0.76256834.67236 0.76529435.76273 0.66311631.88416 0.66311631.88416 0.76654636.72509 0.644532.6585 0.77453638.27121 0.7725638.93899 0.76923339.46982 0.76923339.46982 0.76990140.34639 0.76569140.76557 0.75811840.86349 0.75002940.90207 0.54526932.75244 0.67197436.80361 0.75824242.40802 0.7503342.42676 0.74732842.88399 0.6293432.51192 0.76405245.19173 0.76366745.88172 0.71441942.46801 0.69150942.49939 0.7831748.56256 0.78790249.77953 0.69520844.78815 0.79553251.31058 0.79633252.10741 0.79633252.10741 0.69443746.61256 0.79557252.72446 0.79091752.90634 0.79385353.90424 0.6895247.98001 0.79347954.53175 0.78928154.7293 0.784454.84424 0.78332755.36418 0.79635957.43234 0.79460557.85764 0.7170852.41304 0.79568758.59205 0.79158558.73565 0.7872658.84802 0.7861359.30771 0.8023961.71953 0.80000962.016980.79781562.32829 0.79380562.4267 0.79380562.4267 0.73362652.2922 0.7929462.87396 0.75181157.71037 0.73609757.76379 0.79876864.07198 0.79570964.2534 0.79364664.54166 0.72964458.7174 0.79349565.03866 0.74579956.9527 0.81368767.8587 0.81096368.03841 0.81758869.29695 0.73914259.42996 0.82401670.52953 0.82074670.6166 0.82082371.08925 0.81383456.50736 0.82245671.7353 0.82716372.73165 0.82494672.9135 0.82338673.16673 0.82863774.19883 0.80585368.55407 0.83064274.84767 0.83141175.34599 0.76847565.49526 0.80287269.69636 0.7905669.73976 0.7905669.73976 0.79780161.32573 0.84054976.80077 0.78962770.99732 0.78962770.99732 0.8507278.37023 0.79144872.49446 0.78559973.10672 0.85619379.38419 0.85626779.75944 0.85626779.75944 0.78894670.43071 0.76665470.51248 0.85820480.34287 0.85820480.34287 0.85685280.54014 0.76386972.52784 0.86838882.20633 0.81189668.60206 0.86747982.43333 0.8122677.13887 0.80394177.358730.86967983.00799 0.86956283.31227 0.86956283.31227 0.86956283.31227 0.8670883.34731。