Monocyte activation in alcoholic liver disease

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:329.20 KB

- 文档页数:9

6 ·2022.04Experimental research | 试验研究0 引言金合欢素不但具有解郁安神、理气通络的作用,还具有抗氧化、消炎、抗菌、抗病毒、抗肿瘤等作用[1]。

酒精性脂肪肝是由肝脏负责代谢的,超过90%的酒精会在肝内被分解,使肝细胞膜内的脂质被氧化,从而损害肝细胞的膜,从而影响到脂肪酸的分解和代谢[2]。

本次课题研究实验将小鼠分为3组,分别为对照组、酒精组和金合欢素组。

通过构建金合欢素模型,用酒精溶液对小鼠进行干预,在无菌环境下取出小鼠肝脏进行肉眼观察及显微镜镜下观察。

实验过程中观察小鼠的身体状况的变化。

经解剖对小鼠的肝脏进行病理分析,观察小鼠肝脏是否有病变等特征,分析血清ALT 及AST ,探讨金合欢素对小鼠酒精性脂肪肝的影响。

结果表明酒精干预组的小鼠体重明显下降,肝脏表面出现大小不等的白色空泡,有明显的出血点,颜色变为暗红色,且质地变糟粕。

镜下观察可见酒精干预组小鼠的细胞核分布较分散,且边缘模糊,无明显界限。

而金合欢素药治组的小鼠体重无明显变化,肝脏表面颜色为鲜红色,并且光泽透亮。

镜下观察其细胞核分布密集且轮廓清晰,界限明显。

与对照组比较,酒精组和金合欢素组血清AST 、ALT 的差异性较显著,与酒精组比较,金合欢素组的指标明显降低。

在对小鼠灌胃金合欢素溶液后,小鼠的酒精性脂肪肝病变症状显著减轻,揭示了金合欢素抗肿瘤的一种机制,在治疗酒精性脂肪肝疾病方面有良好的应用价值。

1 材料与方法1.1 溶液的配置以PEG ∶蒸馏水=0.05 g ∶100 mL 的比例,用蒸馏水将PEG 颗粒溶解;取金合欢素最大溶解度为60 mg/kg ,用被溶解后的PEG 溶液将其分化,然后加入蒸馏水稀释;将浓度为100%的酒精以酒精∶蒸馏水=60∶40的比例配置成浓度为60%的酒精。

1.2 用药方式取ICR 级健康雌鼠15只,体重为18~22 g ,将其分为3组,1组5只。

分组后各组小鼠的体重无明显差异。

酒精性肝病发病机制研究进展论文:酒精性肝病发病机制研究进展嗜酒和肝炎病毒感染并列为肝病的两大病因。

酒精性肝病(alcoholic liver disease ,ald)是指长期大量饮用各种含乙醇的饮料所导致的肝脏损害性病变。

ald有四种表现形式:酒精性脂肪肝(alcoholic fatty liver,afl),酒精性肝炎(alcoholic hepatitis,ah),酒精性肝纤维化(alcoholic fibrosis,af)和酒精性肝硬化(alcoholic cirrhosis,ac )。

这四种表现形式可以单独或混合存在。

酒精性肝损伤是常见的致肝硬化原因,在西方国家,ald是导致肝硬化的最主要因素。

据统计,ac病人肝癌发病率大于50%,肝炎病毒感染率低的地区,嗜酒已成为肝癌发病的主要原因。

近年来,随着我国国民经济的发展,人民生活方式的改变,ald的发病率和死亡率在我国呈迅速增长趋势,成为仅次于病毒性肝炎的第二大肝病病种。

王辉等收集了1987-1997年间182例ald患者的临床资料,发现酒精性肝病占所有肝病的比重有逐年增加的趋势,1991年为4.2%,1995年为17.5%,到本世纪末996年则占21.3%。

厉有名等2000年在浙江省进行的18,237例流行病学调查发现,ald检出率为4.34%,其中afl为0.94%,ah为1.51%,ac为0.68%,提示ald在我国发病情况不容乐观。

ald的致病因素单一,即长期大量的酒精摄入。

但其发病机制相当复杂,本文主要对近年来ald发病机制的研究进展做一综述。

1 乙醇及其代谢产物对肝脏的损伤乙醇对肝脏的影响表现在:乙醇对组织和细胞的直接损伤作用;乙醇在肝脏代谢过程中,可使2分子的nad+(氧化型辅酶i)转变为nadh(还原型辅酶i),从而使nadh/ nad+ 的比值明显改变,对葡萄糖合成、脂质代谢及蛋白质的分泌有广泛的影响。

乙醇的主要代谢产物乙醛对肝脏的毒性作用更大,主要表现在:(1)降低肝脏对脂肪酸的氧化;(2)损伤线粒体,抑制三羧酸循环;(3)影响肝脏的微管系统,使微粒蛋白分泌减少,造成脂质和蛋白质在肝脏细胞中沉积;(4)与细胞膜结合,改变其通透性及流动性,从而导致肝细胞的损伤;(5)抑制dna的修复和dna中胞嘧啶的甲基化,从而抑制细胞的分化及损伤组织的再生、修复;(6)乙醛还能增加胶原的合成及mrna的合成,促进肝纤维化的形成。

丁二磺酸腺苷蛋氨酸治疗酒精性肝病临床疗效观察目的考察丁二磺酸腺苷蛋氨酸治疗酒精性肝病的临床疗效并探讨剂量与疗效的关系。

方法选择134例酒精性肝病患者(包括酒精性肝炎、酒精性脂肪肝和酒精性肝硬化)作为研究对象,随机分为三组。

治疗1组采用丁二磺酸腺苷蛋氨酸1.0 g,1次/d 静滴;治疗2组采用丁二磺酸腺苷蛋氨酸2.0 g,1次/d 静滴;对照组给予门冬氨酸钾镁针剂,15 d为一个疗程。

观测治疗前和治疗后TBIL、ALT、AST、GGT、ALP指标及临床症状的变化。

结果治疗组与对照组相比,TBIL、ALT、AST、GGT、ALP各指标均明显改善,治疗1组、治疗2组的总有效率分别为88.9%和93.5%,显著高于对照组58.1%,大剂量组总有效率优于低剂量组。

结论丁二磺酸腺苷蛋氨酸在治疗酒精性肝病方面疗效显著,无毒副反应,且大剂量比小剂量更加有效,为治疗酒精性肝病的理想选择,早期足量使用效果更佳。

[Abstract] Objective To investigate the clinical efficacy of S-adenomethionine in the treatment of alcoholic liver disease and to explore its relationship with dose. Methods A total of 134 cases with alcoholic liver disease(including alcoholic hepatitis,alcoholic fatty liver and alcoholic liver cirrhosis)were selected and were randomly divided into treatment group 1,treatment group 2 and control group. The treatment group 1 was treated with S-adenomethionine 1 g i. v./d,the treatment group 2 was treated with S-adenomethionine 2 g i.v./d,the control group was given aspartic acid potassium magnesium injection,the course of treatment was 15 days. TBIL、ALT、AST、GGT、ALP and other clinical symptoms were observed before and after treatment. Results Compared with the control group,TBIL,ALT,AST,GGT and ALP were significantly improved in the treatment group. The total effective rate of the treatment group 1 and treatment group 2 were 88.9% and 93.5%,respectively,significantly higher than that of the control group 58.1%. Conclusion S-adenomethionine had a significant effect in the treatment of alcoholic liver disease without toxic side effects,and a large dose was more effective than a small dose,It might be concluded that S-adenomethionine is an ideal choice for the treatment of alcoholic liver disease,the early use with sufficient does would be better.[Key words] Alcoholic liver disease;Intrahepatie biliary stasis;S-adenomethionine;High dose酒精性肝病(alcoholic liver disease,ALD)是由长期过度饮酒导致的肝脏疾病。

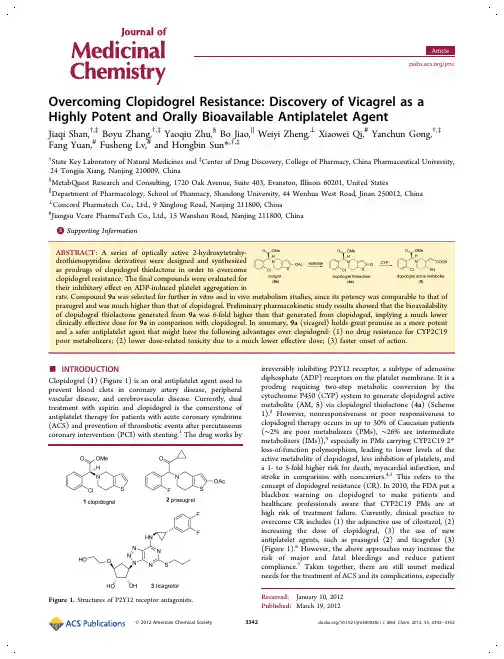

Overcoming Clopidogrel Resistance:Discovery of Vicagrel as a Highly Potent and Orally Bioavailable Antiplatelet AgentJiaqi Shan,†,‡Boyu Zhang,†,‡Yaoqiu Zhu,§Bo Jiao,∥Weiyi Zheng,⊥Xiaowei Qi,#Yanchun Gong,†,‡Fang Yuan,#Fusheng Lv,#and Hongbin Sun *,†,‡†State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines and ‡Center of Drug Discovery,College of Pharmacy,China Pharmaceutical University,24Tongjia Xiang,Nanjing 210009,China §MetabQuest Research and Consulting,1720Oak Avenue,Suite 403,Evanston,Illinois 60201,United States ∥Department of Pharmacology,School of Pharmacy,Shandong University,44Wenhua West Road,Jinan 250012,China ⊥Concord Pharmatech Co.,Ltd.,9Xinglong Road,Nanjing 211800,China #Jiangsu Vcare PharmaTech Co.,Ltd.,15Wanshou Road,Nanjing 211800,China*Supporting Information metabolism studies,since its potency was comparable to that of Preliminary pharmacokinetic study results showed that the bioavailability than that generated from clopidogrel,implying a much lower In summary,9a (vicagrel)holds great promise as a more potent advantages over clopidogrel:(1)no drug resistance for CYP2C19much lower effective dose;(3)faster onset of action.Clopidogrel (1)(Figure 1)is an oral antiplatelet agent used to prevent blood clots in coronary artery disease,peripheral vascular disease,and cerebrovascular disease.Currently,dual treatment with aspirin and clopidogrel is the cornerstone of antiplatelet therapy for patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS)and prevention of thrombotic events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)with stenting.1The drug works byirreversibly inhibiting P2Y12receptor,a subtype of adenosine diphosphate (ADP)receptors on the platelet membrane.It is a prodrug requiring two-step metabolic conversion by the cytochrome P450(CYP)system to generate clopidogrel active metabolite (AM,5)via clopidogrel thiolactone (4a )(Scheme 1).2However,nonresponsiveness or poor responsiveness to clopidogrel therapy occurs in up to 30%of Caucasian patients (∼2%are poor metabolizers (PMs),∼26%are intermediate metabolizers (IMs)),3especially in PMs carrying CYP2C192*loss-of-function polymorphism,leading to lower levels of the active metabolite of clopidogrel,less inhibition of platelets,and a 1-to 5-fold higher risk for death,myocardial infarction,and stroke in comparison with noncarriers.4,5This refers to the concept of clopidogrel resistance (CR).In 2010,the FDA put a blackbox warning on clopidogrel to make patients and healthcare professionals aware that CYP2C19PMs are at high risk of treatment failure.Currently,clinical practice to overcome CR includes (1)the adjunctive use of cilostazol,(2)increasing the dose of clopidogrel,(3)the use of new antiplatelet agents,such as prasugrel (2)and ticagrelor (3)(Figure 1).6However,the above approaches may increase the risk of major and fatal bleedings and reduce patient compliance.7Taken together,there are still unmet medical needs for the treatment of ACS and its complications,especiallyReceived:January 10,2012Published:March 19,2012Figure 1.Structures of P2Y12receptor antagonists.the clinical management of CR.Novel antiplatelet agents with fast onset of action,less interindividual variability,and low risk of bleeding are urgently needed.Given the fact that clopidogrel is among the most widely prescribed drugs worldwide and its long-term safety profile hasbeen established after14years of clinical use,new drug discovery based on this old drug would be highly desirable.As Nobel laureate James Black said,“The most fruitful basis for the discovery of a new drug is to start with an old drug.”We envisioned that,like the metabolic pattern of prasugrel,ester prodrugs9might be readily converted to clopidogrel thiolactone(4a)by esterase-mediated hydrolysis and sub-sequently to clopidogrel AM(5)through only one CYP-dependent step(Scheme1).In this regard,9could be ideal drug candidates for overcoming CR without increasing the risk of bleeding and other side effects associated with the new antiplatelet agents.Herein,we report the identification of a series of2-hydroxytetrahydrothienopyridine derivatives as novel antiplatelet agents.We also describe the detailed structure−activity relationships(SARs)of this series of compounds.Preliminary efficacy,toxicity,and pharmacokinetic studies led to the discovery of vicagrel(9a)as a highly potent and orally bioavailable antiplatelet agent.■RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONChemistry.Optically pure(R)-methyl2-(2-substitued-phenyl)-2-[(4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl)oxy]acetates7a−c were prepared via reaction of mandelic acid and2-substituted mandelic acids with4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride in the presence of triethylamine at low temperature(Scheme2).N-Alkylation of5,6,7,7a-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2(4H)-one hydrochloride(8)with7a−c in the presence of potassium bicarbonate afforded thiolactones4a−c.Reaction of4a−c with acyl anhydrides,acyl chlorides,chlorocarbonic acid esters,or N-substituted carbamic chlorides in the presence of triethylamine or sodium hydride gave optically active2-hydroxytetrahydro-thienopyridine derivatives9a−v with(S)-configuration.The enantiomer of9a((R)-9a)and the racemic mixture of9a ((R,S)-9a)were prepared starting from optically pure(S)-methyl2-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-[(4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl)oxy]-acetate and racemic methyl2-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-[(4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl)oxy]acetate,respectively.The optical purity(%ee)of compounds9a−v and(R)-9a was determinedby chiral HPLC.Inhibition of ADP-Induced Platelet Aggregation inRats and SAR Analysis.Twenty-five2-hydroxytetrahydro-thienopyridine derivatives were evaluated for their inhibitoryeffect on ADP-induced platelet aggregation in rats at dose of3mg/kg.Clopidogrel(1)and prasugrel(2)were used as positivecontrols.ADP-induced platelet aggregation was determined byBorn’s method.8The assay results are summarized in Table1.In our preliminary tests,although clopidogrel showed strongpotency at a dose of10mg/kg(data not shown),it was almostinactive at a dose of3mg/kg.Prasugrel was the most potentone among this set of test pound9a exhibitedvery strong inhibitory effect on platelet aggregation and wasonly slightly less potent than prasugrel.2-Chloro substitutionseemed to be critical for the potency(e.g.,9a−c,l−o),sinceboth2-hydrogen and2-fluoro substitution resulted insignificant loss of potency(e.g.,9u,9v).2-Hydroxy estermoiety of the tetrahydrothienopyridine ring also had asignificant impact on potency.Interestingly,when the size of2-hydroxy alkyl esters increased,the potency decreasedaccordingly(e.g.,potency in the order9a>9b>9c>9d>9e),suggesting that the hindrance at the2-ester groups mightreduce their hydrolysis rates and thus result in lowerconcentrations of clopidogrel AM.The same tendency wasalso observed with carbonic acid esters(e.g.,potency,9m>9n>9p>9q).It was notable that the potency of carbonic acidester9m was similar to that of alkyl ester9a,indicating thatcarbonic acid esters could also be converted to clopidogrel AMas well as alkyl esters.Not surprisingly,clopidogrel thiolactone(4a)was a potent antiplatelet agent,albeit less potent than its Scheme1.Metabolic Activation of Clopidogrel and ProdrugDesignScheme2.Synthesis of Optically Active2-Hydroxytetrahydrothienopyridine Derivatives9a−v aa Reagents and conditions:(a)4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride,CH2Cl2,Et3N,DMAP(cat.),0°C;(b)KHCO3,CH3CN,rt;(c)(R2CO)2O,CH3CN,Et3N,0°C to rt,or R2COCl,THF,Et3N orNaH.For R1and R2,see Table1.acetic ester 9a .Aromatic acid esters (e.g.,9f ,9g ,9h ,9i )were not as potent as alkyl esters,except for nicotinate ester 9l which exhibited strong potency.Substituted carbamate esters were inactive in this assay (e.g.,9s ,9t ).Preliminary tests had shown that 9a seemed to be the most promising drug candidate among this series of compounds,and thus,its enantiomer ((R )-9a )and racemic mixture ((R ,S )-9a )were synthesized and biologically evaluated in order to investigate the effect of configuration on potency.In contrast to 9a ,(R )-9a was almost inactive,while (R ,S )-9a had very weak activity.On the basis of the above results,9a was selected for further in vitro and in vivo metabolism studies.In Vitro Metabolic Activation Studies on Clopidogrel and 9a in Rat Liver Microsomes (RLMs).Clopidogrel (1)could be metabolically activated to form its active metabolite (AM,5)via the thiolactone intermediate (4a )under in vitro incubation conditions with liver microsomes 9or cDNA-expressed P450isozymes 10(Figure 2).The active metabolite (5)is chemically labile probably because of the reactive thiol function.Although it was reported that 5might be stable at 4°C for 24h in quenched incubation mixtures,10for theconvenience of LC −MS/MS-based qualitative and quantitative analyses as well as further purification for NMR studies,5was often derivatized in the incubation mixture with a variety of reagents that were reactive toward the thiol function including glutathione (GSH),acrylonitrile,3′-methoxyphenacyl bromide,N -ethylmaleimide,and dimedone.10,11In this study,glutathione was used to derivatize 5to form the active metabolite −glutathione disulfide adducts (AMGS,Figure 2).To test the metabolic activation of 9a and potential formation of the active metabolite (5),rat liver microsomal incubation was conducted for 9a in parallel with clopidogrel in the presence of NADPH and glutathione.After quenching and centrifugation,the supernatant was analyzed by LC −MS/MS.Incubation of clopidogrel with rat liver microsomes in the presence of GSH leads to NADPH-dependent formation of metabolites (Figure 3A)that exhibited a molecular ion at m /z of 661and a product ion spectrum that is in complete agreement with the formation of the clopidogrel AMGS disulfide adducts.LC −MS/MS analysis of the supernatant resulting from incubation of 9a with rat liver microsomes in the presence of GSH reveals NADPH-dependent formation of glutathione adducts at the same LCTable 1.Inhibitory Effect of 2-Hydroxytetrahydrothienopyridine Derivatives on ADP-Induced Platelet Aggregation in Rats at a Dose of 3mg/kgacompd R 1R 2%ee d platelet aggregation (%)1b99.073.7±5.22c 32.1±9.3**4a 98.148.6±14.6**9a Cl methyl 99.134.6±13.5**9b Cl ethyl 96.546.7±15.4**9c Cl n -propyl 96.352.8±7.7**9d Cl tert -butyl 99.163.4±16.2*9e Cl tert -amyl 99.570.0±23.09f Cl phenyl93.560.1±11.9**9g Cl 4-NO 2-phenyl 10075.6±7.09h Cl 4-MeO-phenyl 96.982.6±9.19i Cl 2-AcO-phenyl 96.077.9±4.99j Cl benzyl 93.553.8±10.4**9k Cl styryl98.784.7±8.79l Cl pyridine-3-yl 97.745.1±9.0**9m Cl methoxy 97.038.6±9.1**9n Cl ethoxy 97.353.0±11.6**9o Cl isopropoxy 97.550.2±9.3**9p Cl isobutoxy 95.565.6±23.29q Cl benzyloxy93.772.2±10.59r Cl phenoxymethyl 89.075.4±4.59s Cl dimethylamino 95.567.7±17.79t Cl pyrrolidine-1-yl 95.780.9±9.29u H methyl 72.081.1±6.09v F methyl86.962.9±12.8*(R )-9a 98.768.4±19.6(R ,S )-9a 63.7±8.0*vehicle75.7±7.7aAssay details are described in Experimental Section.Aggregation data refer to ex vivo measurements 2h after oral administration.(∗)P <0.05.(∗∗)P <0.01vs vehicle.Data are the mean ±SD,n =10.b Clopidogrel hydrogen sulfate was used as a positive control.c Prasugrel free base was used as a positive control.d ee refers to enantiomeric excess.Figure2.Proposed pathways of active metabolite and active metabolite−glutathione adduct formation via in vitro metabolic activation of clopidogrel and9a upon incubation with RLM in the presence of GSH and NADPH.Figure3.LC−MS-selective ion monitoring chromatogram(SIM,M+H+=661)of active metabolite−glutathione(AMGS−1/2/3/4)adducts in RLM incubation of clopidogrel(A)or9a(B)for30min.retention time as the AMGS adducts formed in clopidogrel incubation (Figure 3,B).The molecular ion (MS)spectrum (Figure 4,top)and product ion (MS2)spectrum (Figure 4,bottom)of the glutathione adducts detected in rat liver microsomal incubation of 9a were almost identical to those of the AMGS adducts in clopidogrel incubation (data not shown).The MS spectra of the glutathione adducts show the typical isotopic pattern that is in accordance with the monochloro-containing nature of the AMGS adducts.Fragmentation analysis (Figure 4,inserted)based on the exclusive product ions resulting from collision-induced dissociation (CID)of the molecular ion [M +H]+of m /z 661(MS2spectrum)confirms the formation of the AMGS adducts with the presence of both moieties of 9a and glutathione as well as the disulfide bond formation.The metabolic activation of 9a or clopidogrel confers on the structure of the active metabolite two additional stereochemical sites:one chiral center adjacent to the thio function and one geometric center of the ethylenic double bond,which provide the basis for the formation of four diastereomers.12Chromatographic separation resolved the four diastereomeric AMGS adducts formed from 9a into four peaks with retention times of 9.41min (AMGS −1),9.84min (AMGS −2),10.02min (AMGS −3),and 10.63min (AMGS −4)(Figure 3B).On the basis of the LC −MS/MS studies of in vitro rat liver microsomal incubation of 9a (see Supporting Information)paralleled to clopidogrel,the metabolic activation pathways of 9a are proposed in Figure 2.As shown in the first step,the acetate ester function of 9a undergoes hydrolysis probably by esterases presented in rat liver microsomes and gets deacetylated.The formed 2-hydroxytetrahydrothienopyr-idine (10)is a tautomer of thiolactone 4a ,which is the metabolic intermediate resulting from the first oxidative activation of clopidogrel (1).The metabolic activation pathways of clopidogrel and 9a converge after the first steps through this 2-hydroxytetrahydrothienopyridine −thiolactone tautomerization and share the subsequent pathways including the second step of NAPDH-dependent oxidative ring-opening of 4a that eventually lead to active metabolite formation (Figure 2).Pharmacokinetic Parameters of Clopidogrel Thiolac-tone after Oral Administration of Clopidogrel or 9a to Rats.The dose of clopidogrel or 9a at 24μmol kg −1was orally administered to SD male rats.Blood was collected at 0h (before dosing)and 0.25,0.5,1,2,4,6,8,24h postdose.The dose of clopidogrel thiolactone at 8μmol kg −1was intravenous administration to SD male rats to determine the conversion rate or bioavailability of clopidogrel or 9a to clopidogrel thiolactone.Blood was collected at 0h (before dosing)and 0.083,0.167,0.5,1,2,4,6,8,24h postdose.After sample cleanup,the plasma samples were subjected to LC −MS/MS analysis to determine the plasma concentrations of clopidogrel thiolactone (Figure 5).After oral dosing of clopidogrel,the C max ,T max ,t 1/2,and AUC 0−∞of clopidogrel thiolactone in plasma were 6.93±3.36μg L −1,0.583±0.382h,2.48±0.466h,and 32.2±10.9μg ·h L −1,respectively.After oral dosing of 9a ,the C max ,T max ,t 1/2,and AUC 0−∞of clopidogrel thiolactone in plasma were 67.2±42.3μg L −1,1.17±0.764h,2.19±1.68h,and 211±119μg ·h L −1,respectively.The aforementioned data proved that after oral administration,9a could be readily converted into clopidogrel thiolactone,and bioavailabilityofFigure 4.Averaged molecular ion (MS,top)spectrum and product ion (MS2,bottom)spectrum of the glutathione (AMGS)adducts detected in rat liver microsomal incubation of 9a in the presence of NADPH and glutathione.The inset is proposed fragmentation pathways of the molecular ion [M +H]+of AMGS at m /z of 661.clopidogrel thiolactone generated from 9a was 6-fold higher than that generated from clopidogrel at the same dose.Single-Dose Toxicity of 9a.Single-dose toxicity studies on 9a were performed in GLP laboratories.No mouse (n =10males,10females)died after receiving 5000mg/kg 9a by oral gavage in the 14-day observation period.Liver injury was observed,and no adverse effects were observed in other organs.After oral administration of 9a to beagle dogs,the no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL)was 300mg/kg and the maximal tolerance dose (MTD)was higher than 2000mg/kg.The above data indicate that 9a has very low acute toxicity.■CONCLUSIONSAlthough in 2010,the FDA issued a “boxed warning ”of reduced effectiveness of clopidogrel in patients carrying CYP2C19loss-of-function alleles,there is still debate on whether there is a significant association between CYP2C19genotype and cardiovascular events in patients receiving clopidogrel.5,13,14Nevertheless,it seems no doubt that CYP2C19loss-of-function alleles lead to clopidogrel resistance.In this regard,the cardiovascular risk associated with clopidogrel resistance would be definitely an unnegligible factor,especially for severe ACS patients with PCI,since platelet-mediated thrombotic events might be amplified in the presence of both plaque disruption and interventional procedures.15On the other hand,most of the study population involved in the large-scale clinical trials on clopidogrel were Caucasians among whom the percent of CYP2C19poor metabolizers is only about 2%.By contrast,the percent of CYP2C19poor metabolizers in East Asians is much higher at 15−23%.16That is,the meta-analysis results 13,14based on those clinical trials may not truly reflect the risk associated with clopidogrel resistance,especially for East Asian rge-scale clinical trials addressing clopidogrel resistance are warranted to define the risk of major adverse cardiovascular outcomes among CYP2C19poor metabolizers treated with clopidogrel.In the present study,prodrug design based on clopidogrel thiolactone metabolite was mainly aimed at overcoming clopidogrel resistance.Therefore,252-hydroxytetrahydrothie-nopyridine derivatives were synthesized and evaluated for their inhibitory effect on ADP-induced platelet aggregation in rats.The animal study results showed that some compounds (e.g.,9a ,9b ,9j ,9l ,9m ,9n ,9o )exhibited potent activity as antiplatelet pound 9a was selected for further studies,since its potency was comparable with that of prasugreland was much higher than that of clopidogrel.In vitro metabolism studies revealed that,like clopidogrel,9a could be readily converted to clopidogrel active metabolite by rat liver microsomes.Preliminary pharmacokinetic study results showed that the bioavailability of clopidogrel thiolactone generated from 9a was 6-fold higher than that generated from clopidogrel,implying a much lower clinically effective dose and thus lower dose-related toxicity for 9a in comparison with clopidogrel.In summary,9a holds great promise as a more potent and a safer antiplatelet agent that might have the following advantages over clopidogrel:(1)no drug resistance for CYP2C19poor metabolizers;(2)lower dose-related toxicity due to a much lower effective dose;(3)faster onset of action due to its metabolic activation mechanism.From our point of view,the bleeding risk of 9a should be manageable,since under a proper dosing range,the efficacy of 9a would be equal to that of clopidogrel,and thus,in theory,the bleeding risk of 9a should not be higher than that of clopidogrel.Further preclinical trials on 9a (vicagrel)are currently being conducted in our laboratories to prove the above predictions.■EXPERIMENTAL SECTIONChemistry.Materials and General Methods.All commercially available solvents and reagents were used without further purification.Melting points were determined with a Bu c hi capillary apparatus and were not corrected.1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on an ACF *300Q Bruker or ACF *500Q Bruker spectrometer in CDCl 3,with Me 4Si as the internal reference,or in DMSO-d 6.Low-and high-resolution mass spectra (LRMS and HRMS)were recorded in electron impact mode.Reactions were monitored by TLC on silica gel 60F254plates (Qingdao Ocean Chemical Company,China).Column chromatography was carried out on silica gel (200−300mesh,Qingdao Ocean Chemical Company,China).The purity of all final compounds was determined to be ≥95%by analytical HPLC (equipment:Agilent 1100system with a VWD G1314A UV detector;column,Chiralpak IC,4.6mm ×250mm).Detailed analytical HPLC conditions for each final compound are described in the following section.(R )-M e t h y l 2-(2-C h l o r o p h e n y l )-2-(4-nitrophenylsulfonyloxy)acetate (7a).To a stirred mixture of (R )-2-hydroxy-2-(2-chlorophenyl)acetate (98.4g,0.49mol,99.0%ee)and Et 3N (91mL,0.65mol)in CH 2Cl 2(500mL)at 0°C was slowly added a solution of 4-nitrobenzenesulfonyl chloride (120g,0.54mol)in CH 2Cl 2(500mL).After being stirred for 4h at the same temperature,the mixture was quenched with water.The organic layer was separated,dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate,and concentrated under reduced pressure.The residue was recrystallized in MeOH to afford the title compound as a light yellow solid (154.5g,82.0%yield),98.1%ee (Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:Chiralpak IC,4.6mm ×250mm,eluting with 50%n -hexane +50%i -PrOH,flow rate 0.5mL/min,oven temperature 25°C,detection UV 220nm).1H NMR (300MHz,CDCl 3):δ8.30(d,2H,J =8.9Hz),8.07(d,2H,J =8.9Hz),7.39−7.21(m,4H),6.39(s,1H),3.57(s,3H).ESI-MS m /z 408.0[M +Na]+.(S )-Methyl 2-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-(2-oxo-7,7a-dihydrothieno-[3,2-c ]pyridin-5(2H ,4H ,6H )-yl)acetate (4a).To a solution of (R )-methyl 2-(2-chlorophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenylsulfonyloxy)acetate (58.1g,0.15mol)in CH 3CN (500mL)were added 5,6,7,7a-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c ]pyridin-2(4H )-one hydrochloride (32.3g,0.17mol)and potassium bicarbonate (37.8g,0.38mol).After being stirred at room temperature for 26h under N 2atmosphere,the mixture was filtered and the liquid was concentrated under reduced pressure.The residue was purified by column chromatography to give a yellow oil,which was recrystallized in EtOH to afford the title compound as a white solid (35.4g,70%yield),mp 146−148°C,98.1%ee (determined after conversion to 9a ).[α]D19+114.0°(c 0.5,MeOH).1H NMR (300MHz,CDCl 3):δ7.54−7.51(m,1H),7.44−Figure 5.Plasma concentrations of clopidogrel thiolactone after oral administration of clopidogrel or 9a to SD rats at a dose of 24μmol kg −1.7.41(m,1H),7.32−7.26(m,2H),6.02(s,1H),4.91(s,1H),4.16 (m,1H),3.92(m,1H),3.73(s,3H),3.25(d,1H,J=12.3Hz),3.03 (d,1H,J=12.7Hz),2.65−2.59(m,1H),2.37−2.31(m,1H),1.93−1.79(m,1H).13C NMR(75MHz,CDCl3):δ198.4,170.7,167.1, 134.8,132.8,130.0,129.7,127.1,126.7,67.2,52.2,51.5,51.0,49.6, 33.8.ESI-MS m/z338.1[M+H]+.HRMS calcd for C16H17NO3SCl [M+H]+m/z338.0618,found338.0626.(S)-Methyl2-(2-Acetoxy-6,7-dihydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-5(4H)-yl)-2-(2-chlorophenyl)acetate(9a).To a stirred mixture of 4a(6.5g,19mmol,97.5%ee)and Et3N(5.4mL,38.5mmol)in CH3CN(100mL)at0°C was slowly added acetic anhydride(3.6mL, 38.5mmol).The mixture was stirred for2h at room temperature and quenched with water.Then AcOEt(100mL)was added to the mixture and the organic layer was washed with saturated sodium bicarbonate solution,brine and dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. The organic layer was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by column chromatography to afford a light yellow oil,which was recrystallized in EtOH to afford the title compound as a white solid(6.8g,93.2%yield),mp73−75°C,99.1% ee(Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:Chiralpak IC,4.6mm×250 mm,eluting with92%n-hexane+8%THF+0.1%Et2NH,flow rate 0.5mL/min,oven temperature25°C,detection UV254nm).[α]D23 +45.00°(c1.0,MeOH).1H NMR(300MHz,CDCl3):δ7.70−7.24 (m,4H),6.26(s,1H),4.92(s,1H),3.72(s,3H),3.60(ABq,2H,J =14.2Hz),2.90(s,2H),2.79−2.65(m,2H),2.26(s,3H).13C NMR (75MHz,CDCl3):δ170.7,167.2,149.1,134.2,133.3,129.4,129.3, 128.9,128.8,126.6,125.3,111.5,67.3,51.6,49.8,47.6,24.5,20.2.ESI-MS m/z380.0[M+H]+.HRMS calcd for C18H19NO4SCl[M+H]+ m/z380.0723,found380.0737.(S)-5-(1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl Propionate(9b).Following a procedure similar to that described for the preparation of9a except that an equivalent amount of propionic andydride was used in place of acetic anhydride,the title compound was obtained as a colorless oil in 66.0%yield,96.5%ee(Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:Chiralpak IC,4.6mm×250mm,eluting with90%n-hexane+10%i-PrOH+ 0.1%Et2NH,flow rate0.5mL/min,oven temperature25°C, detection UV254nm).[α]D20+36.00°(c0.50,MeOH).1H NMR(300 MHz,CDCl3):δ7.69−7.26(m,4H),6.26(s,1H),4.91(s,1H), 3.72(s,3H),3.59(ABq,2H,J=14.2Hz),2.88−2.87(m,2H), 2.78−2.76(m,2H),2.55(q,2H,J=7.7Hz),1.23(t,3H,J=7.4 Hz).13C NMR(75MHz,CDCl3):δ171.2,149.8,123.7,130.0,129.8, 129.5,129.1,127.2,125.6,111.7,106.2,67.8,52.2,50.3,48.2,27.4, 25.0,21.1,8.8.ESI-MS m/z394.1[M+H]+.HRMS calcd for C19H21NO4SCl[M+H]+m/z394.0883,found394.0880.(S)-5-(1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl Butyrate(9c).Following a procedure similar to that described for the preparation of9a except that an equivalent amount of butyric anhydride was used in place of acetic anhydride,the title compound was obtained in41.0%yield, 96.3%ee(Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:same as those for9b). [α]D20+32.00°(c0.50,MeOH).1H NMR(300MHz,CDCl3):δ7.69−7.24(m,4H),6.25(s,1H),4.90(s,1H),3.72(s,3H),3.58(ABq,2 H,J=14.3Hz),2.89−2.86(m,2H),2.78−2.76(m,2H),2.52−2.47 (m,2H),1.74(q,2H,J=5.2Hz),1.00(t,3H,J=5.2Hz).13C NMR(75MHz,CDCl3):δ171.2,170.4,149.7,134.7,133.8,130.0, 129.8,129.4,129.2,127.1,125.7,111.8,67.9,52.1,50.3,48.2,35.8, 25.0,18.2,13.5.ESI-MS m/z408.1[M+H]+.HRMS calcd for C20H23NO4SCl[M+H]+m/z408.1035,found408.1036.(S)-5-(1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl Pivalate(9d).To a solution of4a(337.5mg,1.0mmol,97.5%ee)in THF(15mL)was added Et3N(836μL,5.9mmol).After being stirred for10min,the mixture was cooled to0°C and pivaloyl chloride(738μL,6.1mmol)was added.After being stirred at25°C for4h,the mixture was poured into saturated sodium bicarbonate solution(60mL)and extracted with EtOAc(30mL).The organic layer was washed with brine,dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate,and concentrated under vacuum.The residue was purified by column chromatography to give the title compound in85%yield,99.1%ee(Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:same as those for9a).[α]D20+38.00°(c0.50,MeOH).1H NMR(300 MHz,CDCl3):δ7.69−7.23(m,4H),6.26(s,1H),4.90(s,1H),3.72 (s,3H),3.59(ABq,2H,J=14.1Hz),2.88−2.87(m,2H),2.79−2.77 (m,2H),1.30(s,9H).13C NMR(75MHz,CDCl3):δ175.1,171.2, 150.0,134.6,133.7,129.9,129.7,129.3,129.0,127.1,125.5,111.3, 67.7,52.0,50.2,48.1,39.0,26.9,24.9.ESI-MS m/z422.2[M+H]+. HRMS calcd for C21H25NO4SCl[M+H]+m/z422.1198,found 422.1193.(S)-5-(1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl2,2-Dimethylbutanoate (9e).Following a procedure similar to that described for the preparation of9d except that an equivalent amount of2,2-dimethylbutanoyl chloride was used in place of pivaloyl chloride,the title compound was obtained as a white solid in74.9%yield,mp98−100°C,99.5%ee(Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:same as those for9a).[α]D20+36.00°(c0.50,MeOH).1H NMR(300MHz,CDCl3):δ7.69−7.22(m,4H),6.25(s,1H),4.90(s,1H),3.71(s,3H),3.59 (ABq,2H,J=14.3Hz),2.88−2.87(m,2H),2.78−2.76(m,2H), 1.64(q,2H,J=7.3Hz),1.26(s,6H),0.88(t,3H,J=7.4Hz).13C NMR(75MHz,CDCl3):δ174.7,171.2,150.0,134.7,133.7,129.9, 129.7,129.4,129.1,127.1,125.5,111.4,67.8,52.1,50.3,48.1,43.1, 33.3,24.9,24.4,9.2.ESI-MS m/z436.2[M+H]+.HRMS calcd for C22H27NO4SCl[M+H]+,m/z436.1352,found436.1349.(S)-5-(1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl Benzoate(9f).Following a procedure similar to that described for the preparation of9a except that an equivalent amount of benzoic anhydride was used in place of acetic anhydride,the title compound was obtained as a white solid in 52.0%yield,mp84−86°C,93.5%ee(Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:same as those for9b).[α]D20+34.00°(c0.50,MeOH).1H NMR(300MHz,CDCl3):δ8.17−7.26(m,9H),6.42(s,1H),4.95 (s,1H),3.73(s,3H),3.68−3.57(m,2H),2.93−2.82(m,4H).13C NMR(75MHz,CDCl3)δ163.5,149.9,134.7,133.9,130.2,130.0, 129.8,129.5,128.6,128.5,127.2,125.9,112.1,67.8,52.2,50.4,48.2, 25.0.ESI-MS m/z442.1[M+H]+.HRMS calcd for C23H21NO4SCl [M+H]+m/z442.0891,found442.0880.(S)-5-(1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl4-Nitrobenzoate(9g).Fol-lowing a procedure similar to that described for the preparation of9d except that an equivalent amount of4-nitrobenzoyl chloride was used in place of pivaloyl chloride,the title compound was obtained as a yellow solid in26.0%yield,mp100−102°C,100%ee(Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:Chiralpak IC,4.6mm×250mm,eluting with 50%n-hexane+50%i-PrOH+0.1%Et2NH,flow rate0.5mL/min, oven temperature25°C,detection UV254nm).[α]D20+30.00°(c 0.50,MeOH).1H NMR(300MHz,CDCl3):δ8.18(s,4H),7.70−7.26(m,4H),6.47(s,1H),4.95(s,1H),3.73(s,3H),3.70−3.57 (m,2H),2.95−2.91(m,2H),2.84−2.82(m,2H).13C NMR(75 MHz,CDCl3):δ171.3,161.7,151.0,149.2,134.8,133.9,133.6,131.3, 130.0,129.8,129.5,127.2,126.6,123.8,112.6,67.8,67.3,52.2,51.6, 51.1,50.3,49.7,48.1,29.7,25.1.ESI-MS m/z487.0[M+H]+.HRMS calcd for C23H20N2O6SCl[M+H]+m/z487.0736,found487.0731. (S)-5-(1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl4-Methoxybenzoate(9h). Following a procedure similar to that described for the preparation of 9d except that an equivalent amount of4-methoxybenzoyl chloride was used in place of pivaloyl chloride,the title compound was obtained as a yellow oil in30.0%yield,96.9%ee(Chiral HPLC analytical conditions:same as those for9g).[α]D20+26.00°(c0.50,MeOH).1H NMR(300MHz,CDCl3):δ8.09−8.06(m,2H),7.68−7.26(m,4H),6.95−6.92(m,2H),6.38(s,1H),4.92(s,1H),3.85(s,5H),3.71−3.59(m,5H),2.90−2.79(m,4H).13C NMR(75MHz, CDCl3):δ171.2,164.5,163.1,149.9,134.6,133.7,132.7,132.3,129.9, 129.7,129.4,127.1,125.7,121.2,120.6,114.1,113.6,111.8,67.8,55.4, 52.0,50.3,48.1,25.0.ESI-MS m/z472.2[M+H]+,494.2[M+Na]+. HRMS calcd for C24H23NO5SCl[M+H]+m/z472.0993,found 472.0985.(S)-5-(1-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2-methoxy-2-oxoethyl)-4,5,6,7-tetrahydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridin-2-yl2-Acetoxybenzoate(9i). Following a procedure similar to that described for the preparation。

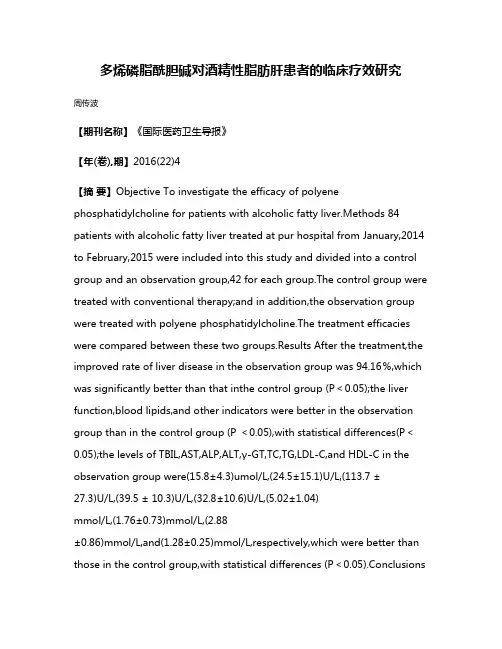

多烯磷脂酰胆碱对酒精性脂肪肝患者的临床疗效研究周传波【期刊名称】《国际医药卫生导报》【年(卷),期】2016(22)4【摘要】Objective To investigate the efficacy of polyene phosphatidylcholine for patients with alcoholic fatty liver.Methods 84 patients with alcoholic fatty liver treated at pur hospital from January,2014 to February,2015 were included into this study and divided into a control group and an observation group,42 for each group.The control group were treated with conventional therapy;and in addition,the observation group were treated with polyene phosphatidylcholine.The treatment efficacies were compared between these two groups.Results After the treatment,the improved rate of liver disease in the observation group was 94.16%,which was significantly better than that inthe control group (P<0.05);the liver function,blood lipids,and other indicators were better in the observation group than in the control group (P <0.05),with statistical differences(P<0.05);the levels of TBIL,AST,ALP,ALT,γ-GT,TC,TG,LDL-C,and HDL-C in the observation group were(15.8±4.3)umol/L,(24.5±15.1)U/L,(113.7 ±27.3)U/L,(39.5 ± 10.3)U/L,(32.8±10.6)U/L,(5.02±1.04)mmol/L,(1.76±0.73)mmol/L,(2.88±0.86)mmol/L,and(1.28±0.25)mmol/L,respectively,which were better than those in the control group,with statistical differences (P<0.05).ConclusionsPolyene phosphatidylcholine can effectively improve the clinical symptoms of patients with alcoholic fatty liver disease and protect the patients' liver function so as to improve the patients' condition.It is worth for clinical application.%目的探讨多烯磷脂酰胆碱对酒精性脂肪肝患者的临床疗效.方法回顾性分析本院2014年1月至2015年2月收治的84例酒精性脂肪肝患者的临床资料,对照组42例患者采用常规治疗,而观察组42例患者在常规治疗基础上加用多烯磷脂酰胆碱,比较两组患者的治疗效果.结果两组患者进行治疗后,观察组的肝病改善情况(94.16%)显著优于对照组(P<0.05),且肝功能和血脂等指标,好转情况亦优于对照组(P<0.05),组间差异均具有统计学意义;两组患者治疗后,观察组的肝功能指标TBIL(15.8±4.3)μmol/L、AST(24.5±15.1)U/L、ALP(113.7±27.3) U/L、ALT(39.5±10.3) U/L、γ-GT(32.8±10.6) U/L,同对照组相比,有显著改善,且组间差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);两组患者治疗后,观察组的血脂水平TC(5.02±1.04)mmol/L、TG(1.76±0.73) mmol/L、LDL-C(2.88±0.86)mmol/L、HDL-C(1.28±0.25) mmol/L,同对照组相比,明显好转,且组间差异有统计学意义(P<0.05).结论多烯磷脂酰胆碱可有效改善酒精性脂肪肝患者的临床症状,保护患者的肝脏功能,从而促进患者病情改善,值得临床应用.【总页数】3页(P532-534)【作者】周传波【作者单位】252000 聊城市第三人民医院内科【正文语种】中文【相关文献】1.多烯磷脂酰胆碱联合非诺贝特片治疗44例老年中重度非酒精性脂肪肝患者的临床研究 [J], 李佳佳2.胆宁片联合多烯磷脂酰胆碱对非酒精性脂肪肝患者肝功能的改善\r效果观察 [J], 向芳菲;陈彬彬3.恩替卡韦联合多烯磷脂酰胆碱对慢性乙型肝炎合并非酒精性脂肪肝患者平均血小板体积血尿酸及TGFβ1的影响 [J], 李潇;时洁;张立伟4.加减清肝化湿活血汤联合多烯磷脂酰胆碱在酒精性脂肪肝患者中的应用 [J], 张冬5.二甲双胍联合多烯磷脂酰胆碱治疗非酒精性脂肪肝患者的效果 [J], 马华因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

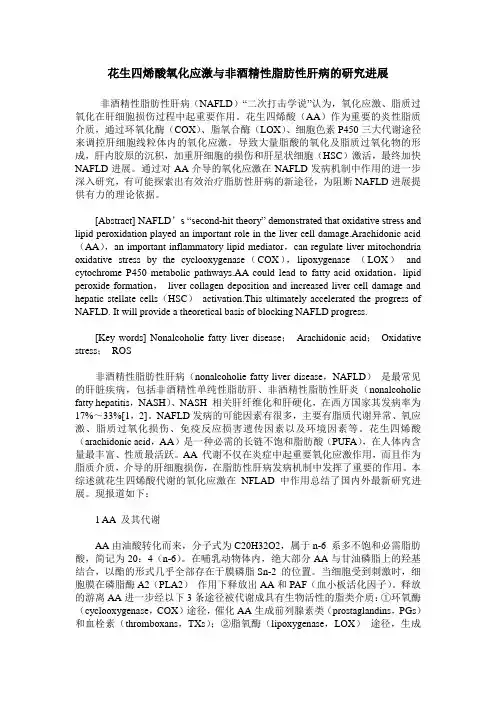

花生四烯酸氧化应激与非酒精性脂肪性肝病的研究进展非酒精性脂肪性肝病(NAFLD)“二次打击学说”认为,氧化应激、脂质过氧化在肝细胞损伤过程中起重要作用。

花生四烯酸(AA)作为重要的炎性脂质介质,通过环氧化酶(COX)、脂氧合酶(LOX)、细胞色素P450三大代谢途径来调控肝细胞线粒体内的氧化应激,导致大量脂酸的氧化及脂质过氧化物的形成,肝内胶原的沉积,加重肝细胞的损伤和肝星状细胞(HSC)激活,最终加快NAFLD进展。

通过对AA介导的氧化应激在NAFLD发病机制中作用的进一步深入研究,有可能探索出有效治疗脂肪性肝病的新途径,为阻断NAFLD进展提供有力的理论依据。

[Abstract] NAFLD’s “second-hit theory” demonstrated that oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation played an important role in the liver cell damage.Arachidonic acid (AA),an important inflammatory lipid mediator,can regulate liver mitochondria oxidative stress by the cyclooxygenase(COX),lipoxygenase (LOX)and cytochrome P450 metabolic pathways.AA could lead to fatty acid oxidation,lipid peroxide formation,liver collagen deposition and increased liver cell damage and hepatic stellate cells(HSC)activation.This ultimately accelerated the progress of NAFLD. It will provide a theoretical basis of blocking NAFLD progress.[Key words] Nonalcoholie fatty liver disease;Arachidonic acid;Oxidative stress;ROS非酒精性脂肪性肝病(nonalcoholie fatty liver disease,NAFLD)是最常见的肝脏疾病,包括非酒精性单纯性脂肪肝、非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(nonalcoholic fatty hepatitis,NASH)、NASH 相关肝纤维化和肝硬化,在西方国家其发病率为17%~33%[1,2]。

美他多辛论文:美他多辛对酒精性脂肪肝大鼠CYP2E1影响的研究【中文摘要】美他多辛是在国内上市不久,专一治疗酒精性脂肪肝病药物。

临床上使用美他多辛主要用于治疗酒精性脂肪肝,对其预防作用考察的不多。

通过调研文献发现CYP2E1与酒精性脂肪肝密切相关,但国内未有美他多辛与CYP2E1之间联系的研究。

本课题欲通过构建酒精性脂肪肝大鼠模型,研究美他多辛对酒精性脂肪肝大鼠的预防作用,并探索其作用机制,研究美他多辛与CYP2E1的关系,分析CYP2E1是否是美他多辛的治疗靶点。

方法:清洁级Wistar雄性大鼠30只,体重(200±20)g,每日给予大鼠标准食物和饮用水各2次,保持光照和避光循环饲养各12 h。

将所有大鼠随机分为3组,分别为模型组10只,预防组10只,对照组10只。

采用乙醇灌胃法建立酒精性脂肪肝大鼠模型:给予大鼠40%乙醇(剂量为乙醇8 g·kg-1·d-1)灌胃,每日2次,间隔8 h,至4 wk末。

5 wk开始,将乙醇浓度增至50%(剂量为乙醇10 g·kg-1·d-1),至8wk末。

对照组:不灌服乙醇,每日2次给予等体积灭菌注射用水;模型组:1-8 wk建立酒精性脂肪肝大鼠模型的同时,在每次灌服乙醇1h后给予等体积灭菌注射用水;预防组:1-8 wk建立酒精性脂肪肝大鼠模型的同时,每次灌服乙醇1h后给予美他多辛(300 mg·kg-1·d-1)。

给大鼠超声检查,采用全自动生化仪来检测血清指标,ELISA测定脂蛋白脂酶,HE染色观察肝组织病理学变化,油红O染色观察肝脂肪沉积,天狼星红染色染色观察肝胶原染色,蒽酮法测定肝糖原含量,肝组织免疫组化检测TNF-α、IL-6、CYP2E1的蛋白表达,蛋白印记法检测肝组织中CYP2E1蛋白含量,所得数据使用SPSS17.0统计分析软件。

结果:大鼠酒精性脂肪肝模型建立成功,模型组有1只大鼠死亡,为酒精误吸入气管所致,其他组无大鼠死亡。

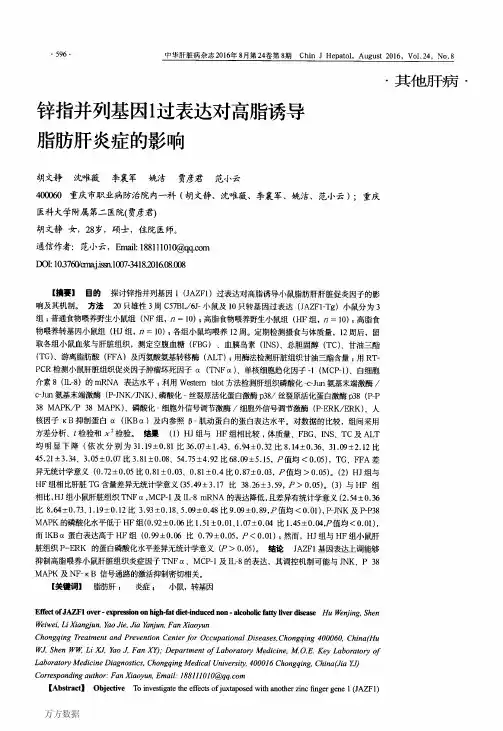

113 Kupffer cell number is normal, but their lysozyme content is reduced in alcoholic liver disease

A quan!.itative immunohistochemical study of Kupffer cells in liver biopsies from alcoholics was carried out. Two markers were compared. lysozymr and an andmacrophage monoclonal antibody ERWll. The results showed that there is no signi’icant reduction in Kupffer cell numbers in acute and chronic alcoholic liver disease but that there is a reduction in the number of Kupffer cells staining positively for lysozyme. Thus, those clinical phenomena such as endotaxaemia in alcoholic liver disease are not due to reduction in Kupffer cell number but perhaps to a functional deficit in these cells.

Intmtluf!ion There is abundar.t evidence of disordered functicn of the mont;nuclear phagucy;e systems (MPS) in hu- man chronic liver disease (11. Underlying this, a vari- ety of disorders of peripheral blood monocyte func- tion ixluding defective chemotaxis 121, reduced ?ha- gocytosis alnd killing of micmorganisms 13.41 has been demonstrated. While some of these defects IT ay be secondary to cirrhosis itself [5], they have al o been demonstrated in non-cirrhotic alcoholics 161 These defects are not limited to peripheral bloa! monocyss but a;e also found in hepatic MPS ce!!r the Kupffer cells (KG) [7]. KCs are a major CO~I~W nest of the MPSconst~tuting up to 90% of MPScells in direct contact with the blood stream 181, with up to 50% of cmxlating monocytes ultimate:y sett!ing in the liver wusoids and differentiating into KCs [9], although in certain conditions local pmliferation may also conrrlbute to numbers [lo]. One of the major functions of KCs is to clear intestinal bacterial enda- toxinr [ll] and bacteria from the portal blood [12]. Systemic endotoxaemia may account for many of tb extrahepati: complications m patients with chronic liver disease Il3]. Impairment of KC activity has been shown in chronic alcoholics [14]. In rats, it has been demonstrated that alcohol ingestion itself leads to depression in KC clearance of gut-derived 174 endotoxins [7] but it is unclear whether the effect is direct or indirect. Humans without evidence of chrouic liver disease also developed systemi: cndo- toxaemia after ingestion of large quantities of alcohol [IS]. The implication of this is that cndotoxaemia cannot be attributed solely to porto-systemic shunt- iog of blood, hut that the liver is unable to c-icxcndo- toxin effertiurly. In chronic alcoholics the jejunal mi- croflora is abnormal with overgmwth, especially of auaerobes and coliforms [16]. In man, alcohol inges- tion increases permeability of the upper small intesti- nal mucos~ to macromolcculcs [IS]. These findings imply that an increased porrsl venous load of endo- toxin resulting from such inneastd permeability may overload KC function and/or damage them, the rc- suit being that endotoxins ‘spill over’ into the systcm- ic circulation !!7]. KC number> and disrrtbution in chronic liver dis- ease have been studied by in situ histological studies [I8,19] using lysozyme as an immunohistochemical mariw [20-22). These studies have show a reduc- tion in numbers of lysozyme-positive sinusoid-lining cells (SLC) in a variety of chmnic liver diseases (181 and specifically in alcoholic liver disease 1191. They have failed to show whetlo: there is an actual reduc- tion in KC numbers, although in one a population of lysozyme-negative SLC has been recognized [19]. If there is indeed a reduction, the implicatioo. may bc important, as depletion of KCs m chronic liver dis. case may he partially responsible, per se, for endo- tosneiuia. However, the validity of this conclusion is diminished by the non-specificity of lyrozyme as an MI’S marker. It is found in granulocytes and in a vari- ety of epithelia [ZO-221. In an attempt ;o resolw the question of whether KC numbers are actually reduced in alcoholic liver disease, we have undertaken a quantitative immuno- histochemical study of KC in alcoholic liver disease in which we have compared two markers for cells of the MPS, lysozyme and a mouse monoclonal antibody EBMllI which has a high specitXty for cells of the human MPS 123,243. At the Third International Workshop on Human lxucocyte Differentiation An- tigens. EBM/ll was assigne.l to Group i !. :itc mixed airti-macrophagc group. Within this group, it is in- eluded in subgroup A txhich iwludes those antibodies with broad specificity [25]. Unlike many of the acti- bodies in this goop, EEM/ll show strong reactivity with peripheral blood monocytes [23].

酒精性肝病白细胞介素6的检测及意义王瑞科1,刘秀珍2,张谷运2,李 红3,孙兆翠2,张金安2(11济宁医学院附属医院,山东济宁272029;21济宁传染病医院,山东27200;31济宁市中医院,山东272000)收稿日期:2004-03-18 修订日期:2004-05-11基金项目:济宁科技局科研项目(济科成鉴字[2003]第29号)作者简介:王瑞科(1969—),男,山东省济宁人,主治医师,学士。

【摘要】探讨酒精性肝病患者I L -6的活性改变与酒精性肝病肝纤维化的临床意义。

测定了120例酒精性肝病患者和30例健康成年人(对照组)的I L -6、H A 、LN 、PC -Ⅲ、Ⅳ-C 。

酒精性肝病患者,血清I L -6明显高于对照组,有显著性差异(P <0105~0101)。

酒精性肝病患者血清中H A 、LN 、PC -Ⅲ、Ⅳ-C 的改变明显高于对照组(P <0101~01001)。

I L -6的活性改变与酒精性肝病的肝纤维化呈正相关性。

【关键词】酒精性肝病;白细胞介素6;肝纤维化【中图分类号】R575 【文献标识码】B 【文章编号】1001-5256(2005)02-0100-02Monitoring the ch ange of interleukin -6in the alcoholic liver disease and its clinical significance WANG Rui -ke ,LIU Xiu -zhen ,ZH ANG Gu -yun ,et al (Affilated hospital o f Jining Medical college ,Jining 272029,Shandong Province ,China ).Abstract :T o study the relationship between the change of interleukin -6(I L -6)activity and the level of hepatic fibrosis in alco 2holic liver disease (A LD ).Am ong the 120patients with A LD ,the level of interleukin -6(I L -6)、hyaluronic acid (H A )、laminin (LN ),type Ⅲprocollagen (PC -Ⅲ)and type Ⅳcollagen (Ⅳ-C )in serum is m onitored.The same items are m onitored in the control group with 30healthy people.The in acase of I L -6in A LD group (P <0105~01001).The changes of H A 、LI V 、PC -Ⅲand Ⅳis marked nigher than the control group (P <01001~010001).The changes of I L -6activity is P osilive correlaled with the level of hepatic fibrosis in A LD.K ey w ords :alcoholic liver disease ;interleukin -6;hepatic fibrosis 于2001年1月至2002年12月,我们对120例酒精性肝病患者血清中的I L -6的活性改变进行了相关研究,另外选择了30例健康成年人作为对照组进行了对比研究,现报道如下:1 资料与方法111 临床资料 按梁扩寰主编肝脏病学(1995)的诊断标准[1],选取符合诊断标准的120例患者作为观察组,30例健康查体成年人作为对照组。

Alcohol 27 (2002) 53–61 0741-8329/02/$ – see front matter © 2002 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.PII: S0741-8329(02)00212-4

Monocyte activation in alcoholic liver disease Craig J. McClain a,b, *, Daniell B. Hill a , Zhenyuan Song a , Ion Deaciuc c , Shirish Barve a a Department of Medicine, University of Louisville Medical Center, the b Veterans Administration, Louisville, KY 40292, USA

c Department of Medicine, University of Kentucky Medical Center, Lexington, KY 40536, USA

Received 18 December 2001; received in revised form 25 January 2002; accepted 9 February 2002

Abstract Activated monocytes and macrophages have been postulated to play an important role in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease(ALD). Monocyte activation can be documented by measurement of neopterin, adhesion cell molecules, and certain proinflammatory cy-tokines and chemokines. We first became interested in the role of monocytes and monocyte-derived cytokines in ALD in relation to al-tered zinc metabolism that occurs regularly in ALD. Patients with ALD have hypozincemia, which responds poorly to oral zinc supple-mentation. We have shown that in ALD monocytes make a low-molecular-weight substance that, when injected into rabbits, causesprominent hypozincemia. Subsequently, multiple cytokines [especially tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin (IL)-8] have beenshown to be overproduced by monocytes in ALD. We initially showed that monocytes in ALD spontaneously produce TNF and overpro-duce TNF in response to a lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulus, and this could be attenuated by antioxidants in vitro and in vivo. Alter-ations in the endotoxin-binding protein LPS-binding protein, in CD14, and in the endotoxin receptor Toll-like receptor 4 all may playroles in enhanced proinflammatory cytokine signaling in ALD. Moreover, several groups have documented increased TNF receptor den-sity in monocytes in ALD. Inadequate negative regulation of TNF occurs at multiple levels in ALD. This includes decreased monocyteproduction of the important antiinflammatory cytokine IL-10 and blunted response to the antiinflammatory properties of adenosine. Fi-nally, generation of reactive oxygen species (which occurs during alcohol metabolism) and products of lipid peroxidation induce produc-tion of cytokines, such as TNF and IL-8. In conclusion, there are multiple overlapping potential mechanisms for enhanced proinflamma-tory cytokine production by monocytes in ALD. We postulate that activation of monocytes and macrophages with subsequentproinflammatory cytokine production plays an important role in certain metabolic complications of ALD and is a component of the liverinjury of ALD.© 2002 Elsevier Science Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Alcoholic liver disease; Cytokines; Oxidative stress; Monocytes

1. Introduction The research focus of our laboratory for more than 15years has been the activation of monocytes, macrophages,and Kupffer cells in alcoholic liver disease (ALD), subse-quent production of proinflammatory cytokines such as tu-mor necrosis factor (TNF), and consequent production ofmany of the metabolic complications and the liver injury ofALD (McClain et al., 1999). In this review, we will focuson the role of monocyte activation in ALD and thus the roleof monocytes in the pathogenesis of systemic and clinicalcomplications of ALD. Three components will be ad-dressed: (1) evidence for monocyte activation in ALD, (2)potential mechanisms for monocyte activation in ALD, and(3) role of secreted monocyte products (e.g., cytokines) inthe systemic sequelae of ALD. For this symposium, wehave not addressed the role of other cell types, such as neu-trophils and lymphocytes, in the pathogenesis of liver in-jury, nor the role of Kupffer cells in liver injury. These areashave been reviewed extensively in other participants’ pa-pers in these proceedings.

2. Monocyte activation There are several ways in which monocyte activation canbe documented. One of the most widely used markers is theserum or urinary neopterin level (a nonspecific indicator ofmonocyte activation). Neopterin is a pyrazino-pyrimidinecompound that is produced in large amounts by macro-phages after stimulation with interferon-gamma (IFN- ␥ ).Neopterin levels are consistently elevated in ALD (Luna-

*Corresponding author. Department of Internal Medicine, Universityof Louisville Medical Center, 550 S. Jackson St., ACB 3rd Floor, Louis-ville, KY 40292, USA. Tel.: ϩ 1-502-852-6991; fax: ϩ 1-502-852-0846. E-mail address : craig.mcclain@louisville.edu (C.J. McClain).Editor: T.R. Jerrells