When Brokers May Not Work The Cultural Contingency of Social Capital in Chinese High-tech Firms

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:141.60 KB

- 文档页数:32

Unit 7 section A Woman at the management level 女性管理者1When Monica applied for a job as an administrative assistant in 1971, she was asked whether she would rather work for a male or a female attorney. "I immediately said a man," she says. "I felt that a male-boss/female-employee relationship was more natura l, needing no personal accommodation whatsoever." But 20 years later, when she was asked the same question, she said, "I was pleasantly surprised that female bosses are much more accessible to their employees; they're much more sensitive and intimate w ith their employees."1 当莫妮卡 1971 年申请一个行政助理的工作时,有人问她想与男律师共事还是与女律师共事。

“我马上说想与男律师共事,”她说。

“我认为男老板和女雇员的关系更自然,丝毫不需互相调整。

”但 20 年后,有人问她同样的问题时,她说:“令我感到惊喜的是,对员工来说,女上司更容易接近,她们更能理解人,员工更亲密。

”preclude, discard, abandon, eliminate, abolish, dismisspreclude 排除discard 丢弃,抛弃(可指人也可指物)abandon 放弃(某物)eliminate 消除,淘汰abolish (依法)废除dismiss 解雇2 Female bosses today are still finding they face subtle resistance. There is still a seg ment of the population, both men and, surprisingly, women who report low tolerance for female bosses. The growing presence of femalebosses has also provoked two major questions that revolve around styles: Do men and women manage differently, and, if so, is that a good thing?2 今天的女上司仍然发现,她们面临着不易察觉的阻力。

人教版选择性必修二Unit2 Bridging Cultures 单元词汇高考真题例句清单1.(2023全国新课标Ⅱ卷阅读填句)These small studies provide inspiration and may be a springboard for more plex works in the future.这些小型研究提供了灵感,可能是未来更复杂工作的跳板。

2.(2023年6月全国甲卷应用文)I started with easy items like scarves and gradually moved on to more plex ones like hats and sweaters.我从简单的东西开始,比如围巾,然后逐渐转向更复杂的东西,比如帽子和毛衣。

3.(2020·新高考Ⅱ卷·A)Follow all rules carefully to prevent disqualification.仔细遵守所有规则,以免被取消资格。

4.(2023全国甲卷听力)I think I’m well qualified for the accountant position here.我认为我能胜任这里的会计一职。

5.(2020· 天津高考·D)Together, these deep human urges(驱策力)count for much more than ambition. Galileo was not merely ambitious when he dropped objects of varying weights from the Leaning Tower at Pisa and timed their fall to the ground.总之,这些人类内心深处的欲望比野心重要得多。

当伽利略从比萨斜塔上扔下不同重量的物体并计算它们落地的时间时,他不仅仅是雄心勃勃。

Ⅰ.认阅读单词1.heritage n.遗产(指国家或社会长期形成的历史、传统和特色) 2.temple n.庙;寺3.relic n.遗物;遗迹4.clue n.线索;提示5.dam n.水坝;拦河坝6.protest n.抗议v i.&v t.(公开)反对;抗议7.committee n.委员会8.fund n.基金;专款9.document n.文件;公文;(计算机)文档v t.记录;记载(详情) 10.republic n.共和国11.archaeologist n.考古学家12.pyramid n.(古埃及的)金字塔;棱锥体13.sheet n.一张(纸);床单;被单14.parade n.游行;检阅v i.游行庆祝;游行示威15.digital adj.数码的;数字显示的16.cave n.山洞;洞穴17.quote v t.引用18.paraphrase n.,v i.&v t.(用更容易理解的文字)解释Ⅱ.记重点单词1.mount n.山峰v t.爬上;骑上v i.爬;登上2.former adj.以前的;(两者中)前者的3.preserve v t.保存;保护;维持n.保护区4.likely adj.可能的ad v.可能地5.department n.部;司;科6.within prep.&ad v.在(某段时间、距离或范围)之内7.issue n.重要议题;争论的问题v t.宣布;公布8.conduct n.行为;举止;管理方法v t.组织;安排;带领9.attempt n.&v t.企图;试图;尝试10.worthwhile adj.值得做的;值得花时间的11.download v t.下载n.下载;已下载的数据资料12.entrance n.入口;进入13.process n.过程;进程;步骤v t.处理;加工14.overseas adj.海外的ad v.在海外15.exit n.出口;通道v i.&v t.出去;离去16.mirror n.镜子17.roof n.顶部;屋顶18.dragon n.龙19.image n.形象;印象20.throughout prep.各处;遍及;自始至终21.quality n.质量;品质;素质;特征adj.优质的;高质量的22.further ad v.(far的比较级)更远;进一步23.opinion n.意见;想法;看法24.contrast n.对比;对照v t.对比;对照25.forever ad v.永远;长久地Ⅲ.知拓展单词1.creatively ad v.创造性地;有创造力地→creative adj.创造性的;有创造力的;有创意的→create v t.创造→creativity n.创造性;创造力→creation n.作品;创造2.promote v t.促进;提升;推销;晋级→promotion n.提升;推销;晋级3.application n.申请(表);用途;运用;应用(程序)→apply v t.&v i.申请;应用;涂;敷→applicant n.申请人→app n.应用程序;应用软件(application的缩略形式)4.balance n.平衡;均匀v t.使平衡→balanced adj.平衡的;均衡的5.proposal n.提议;建议→propose v t.提议;建议6.establish v t.建立;创立→establishment n.建立;创立7.limit n.限度;限制v t.限制;限定→limited adj.有限的;受限制的→limitless/unlimited adj.无限的;无尽的→limitation n.限制;局限;极限8.prevent v t.阻止;阻碍;阻挠→prevention n.防止;预防→preventive adj.预防性的;防备的9.loss n.丧失;损失→lose v t.丢失→lost adj.迷路的;失去的10.contribution n.捐款;贡献;捐赠→contribute v i.&v t.捐献;捐助11.investigate v i.&v t.调查;研究→investigation n.调查;研究12.donate v t.(尤指向慈善机构)捐赠;赠送;献(血)→donation n.捐赠物;捐赠;赠送→donor n.捐赠者;捐赠人13.disappear v i.消失;灭绝;消亡→disappearance n.消失;灭绝→(反义词)appear v i.出现→appearance n.出现;外表14.professional adj.专业的;职业的n.专业人员;职业选手→profession n.专业;职业→professor n.教授15.forgive v t.&v i.(forgave,forgiven)原谅;宽恕v t.对不起;请原谅→forgiveness n.原谅;宽恕16.tradition n.传统;传统的信仰或风俗→traditional adj.传统的17.historic adj.历史上著名(或重要)的;有史时期的→history n.历史→historian n.历史学家→historical adj.(有关)历史的;历史上的18.comparison n.比较;相比→compare v t.&v i.与……相比较19.identify v t.确认;认出;找到→identity n.身份;个性→identification n.识别;身份证明(文件)1.attendance n.出席人数;出席;参加2.awful adj.可怕的3.bacterium(复bacteria)n.细菌4.baggage n.行李5.banquet n.宴会,盛宴6.bare adj.空的;赤裸的7.bargain n.(经讨价还价之后)成交的商品;廉价货v i.讨价还价8.barrier n.障碍;隔阂Ⅳ.背核心短语1.take part in参与(某事);参加(某活动)2.give way to让步;屈服3.keep balance保持平衡4.lead to导致5.make a proposal提出建议6.turn to向……求助7.prevent...from...阻止;不准8.donate...to...向……捐赠……9.make sure确保;设法保证10.all over the world在世界各地Ⅴ.悟经典句式1.There comes a time when the old must give way to the new,and it is not possible to preserve everything from our past as we move towards the future.(There comes a time when...)新旧更替的时代已经到来,在走向未来的过程中,我们不可能将过去的一切都保存下来。

新视野大学英语第四册unit5B...Culture makes the business world go round文化推动商业世界的运转Edward Hall, a leader in the field of intercultural studies, famously said: "The single greatest barrier to business success is the one erected by culture." Can cultural differences have as big an impact on international business ventures as financial planning and visionary leadership? The surprising answer is: Yes!他曾说过一句名言:“商业成功的最大障碍是由文化竖立的障碍。

”对国际企业来说,文化差异难道真的和财务规划及前瞻性领导有着同样大的影响吗?答案是出人意料的:的确如此!A good example is the role of relationships in business dealings. While relationships play only a minor role in US business culture, they play a major role in Asian, African, and Middle Eastern countries. In these cultures, in varying degrees, relationship building is like a torch that lights and guides the way for business to occur.一个很好的例子,人际关系在生意往来中所起的作用。

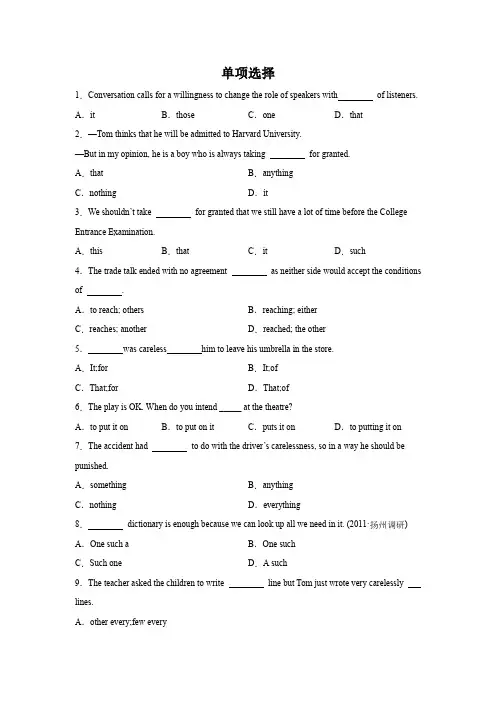

单项选择1.Conversation calls for a willingness to change the role of speakers with of listeners. A.it B.those C.one D.that2.—Tom thinks that he will be admitted to Harvard University.—But in my opinion, he is a boy who is always taking for granted.A.that B.anythingC.nothing D.it3.We shouldn’t take for granted that we still have a lot of time before the College Entrance Examination.A.this B.that C.it D.such4.The trade talk ended with no agreement as neither side would accept the conditions of .A.to reach; others B.reaching; eitherC.reaches; another D.reached; the other5.was careless him to leave his umbrella in the store.A.It;for B.It;ofC.That;for D.That;of6.The play is OK. When do you intend _____ at the theatre?A.to put it on B.to put on it C.puts it on D.to putting it on 7.The accident had to do with the driver’s carelessness, so in a way he should be punished.A.something B.anythingC.nothing D.everything8.dictionary is enough because we can look up all we need in it. (2011·扬州调研) A.One such a B.One suchC.Such one D.A such9.The teacher asked the children to write line but Tom just wrote very carelessly lines.A.other every;few everyB.other every;every a fewC.every other;every fewD.every other;every a few10.You must keep________in mind________you are a student in this school, so you should obey the school rules.A.it; thatB.such; asC.everything; whichD.something; because11.I admired the painting, and Ed said he would like me to have ______ as a gift from him. A.one B.it C.this D.some 12.Nowadays more and more people abroad find________ almost impossible for them to avoid buying products made in China.A.that B.themselves C.its D.it13.I like the house with a beautiful garden in front, but I don’t have enough money to buy______.A.it B.that C.one D.these14.Mrs. Green bought three pineapples, but she ate ________ of them. Her children ate them all. A.none B.all C.either D.neither15.I tried to make ________ clear to him that we were not responsible for his mistake.A.this B.that C.it D.one16.– Madam, the two pairs of shoes are the new arrival of the season.–Well, I want to try another pair, ________ fit my style.A.both of which B.neither of whichC.either of them D.neither of them17.They acknowledge ________, in a few cases, home schooling offers educational opportunities superior to ________ found in most public schools, but few parents can provide such educational advantages.A.where; ones B.that; those C.that; them D.what; which 18.________is really easy to get lost among the twisting and turning Hutongs near the PalaceMuseum in Beijing.A.It B.That C.This D.What19.The owner and captain discussed it with _______ colleagues.A.its B.their C.her D.him20.I’d like to buy a present for my father’s birthday, _______ at a proper price but of great use. A.the one B.that C.which D.one21.________ struck me that the little boy swimming alone in the pool was my neighbor. A.What B.That C.Which D.It22.Why don’t you bring _____ to his attention that you are too busy to do it?A.this B.what C.that D.it23.— Can I help you, sir?— Well, I intend to purchase a gift for my buddy’s wedding anniversary, ________ at a proper price, but of great value.A.which B.that C.one D.it 24.Students in Shuang Ling Middle School think ________ vital to learn English well, so they make good use ________ their spare time to study it hard.A.this; with B.that; of C.it; of D./; for 25.—What do you think of your English teacher?—In my opinion, her teaching is nothing like __________ of the teacher in Junior Three. A.this B.it C.that D.one 26.—What do you think of ________ Chinese teacher?—She is an excellent teacher. I’ve improved a lot since she taught _____ Chinese.A.our; us B.our; our C.ours; us D.ours; our 27.Kerry’s teaching experience in China is quite different from________ of other foreign teachers.A.one B.it C.this D.that 28.—How much water is there in the bottle?—________. You’d better come to fetch another one.A.A little B.Nothing C.No one D.None29.I turned to bookshops and libraries for information but found ______.A.none B.both C.one D.either30.I had warmly invited Jane and Mary to dinner this evening, but unfortunately ________of them came.A.neither B.both C.either D.none31.We find ________ more useful for students to do new eye exercises.A.it B.this C.one D.that32.There are two apples on the table. One is red and ________ is green.A.the other B.another C.others D.the others33.In the old days, stock brokers earned commissions every time________ bought or sold a stock on their client’s behalf.A.when they B.they C./D.that34.Our basketball team plans to hire a coach(教练), ________ with a strong will and a good sense of humor.A.who B.which C.one D.that35.—Is this red schoolbag your sister's?—No, it isn't. ____________is black.A.Mine B.Hers C.His36.—My mother bought me two pairs of shoes. ________ of them is made in China.—I prefer the ones made in China, which are nice but not expensive.A.Both B.None C.Neither37.—Is the black car the Smiths’ ?—I’m afraid not. ________ is the red one over there.A.Ours B.His C.Theirs38.Is that a book on computer technology? If so, I would like to borrow________.A.are B.it C.this D.some39.I am thirsty. Could you let me have ________ coke?A.little B.any C.some D.other40.Mike’s ideas are always different from_____,and we all like to ask him for advice.A.us B.we C.our D.ours41.No visitor would think _________ surprising that the island is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.A.that B.it C.this D.what42.—I don’t think ______ possible for little Julia to walk around without any assistance.—But she made it.A.this B.she C.that D.it 43.Adolescents need adults to guide them; otherwise, ______ is easy for them to get into trouble. A.that B.which C.it D.what 44.—Have you made clear when and where the meeting is to be held?—Not yet.A.them B.that C.this D.it45.—Can I come today or tomorrow?—_________is OK. I’m busy today and tomorrow.A.Either B.Neither C.Each D.None 46.Understanding the cultural habits of another nation, especially ________ containing as many different cultures as the United States is a difficult thing.A.which B.one C.that D.it47.To get a good education, ________.A.working hard is very important B.it is essential to work hardC.one must work hard D.it is needed to work hard48.To know more about the Summer Palace, you can use the Internet or go to the library, or______.A.neither B.some C.all D.both49.— Have you booked a table, madam?— Yes, we’ve booked ______ for two. The name is Morrison.A.it B.that C.this D.one50.The little boy bought two ball-pens, ________ writing well.A.none of them B.none of whichC.neither of them D.neither of which51.If something is wrong, fix it. Do not worry. Worry never fixes ________.A.something B.anything C.nothing D.everything 52.— Have you got any books on the differences between Chinese and Western festivals? I want to borrow one.— Yes, here you are. But you must return ________ by Sunday.A.one B.it C.this D.that53.Video footage circulated by state media showed gray smoke emerging from the crash site and ________appeared to be a wing fragment lying along the side of a mountain trail with the Chinese characters for “China Eastern” partly visible.A.which B.that C.what D.as54.It seemed so sad that the two, who had been lovers, pretended not to recognize ________ when they met in the street.A.neither B.the other C.each other D.another55.In fact ________ is a hard job for the police to keep order in an important football match. A.this B.that C.there D.it56.________ in the office had made a mistake, and the firm regretted causing the customers inconvenience.A.None B.Anyone C.One D.Someone 57.—Bob isn’t feeling very well today. He has caught a cold.—Everybody seems to have ______, owing to the sudden change of weather.A.one B.it C.that D.another58.We think _______ no use ________ with him.A.it; arguing B.it; to argue C.that; arguing D.that; to argue 59.Nine in ten parents said there were significant differences in their approach to educating their children compared with ____________of their parents.A.those B.that C.the ones D.these60.You think he's talking nonsense, but I believe there is __________in his words. A.something B.anything C.nothing D.everything61.________ didn’t seem worthwhile writing it all out again.A.This B.That C.Which D.It62.Tell_________about the Great Wall please.A.I B.my C.me D.mine63.—Is this dictionary _________?—No, it isn’t. I left my dictionary at home.A.your B.yours C.yourself D.you64.I really think ________ impossible to finish the work in such a short time.A.it B.this C.them D.that65.The goods ______on the Internet are cheaper than ______ we buy in shops.A.be bought; that B.bought; thoseC.bought; that D.be bought; those66.Many people expressed concern, but _______were willing to help.A.the other B.other C.others D.another67.He is a good leader who always thinks more of the public than of himself,________ we should follow the example of.A.which B.the one C.one D.whoever68.______ is no longer too difficult for women and minorities ______ roles in American film and television.A.What; to get B.It; to get C.That; getting D.Who; getting 69.A survey shows that senior high school students who are engaged in after-school activities are happier than ________ who are not.A.those B.that C.them D.they70.Is ______ necessary for you to buy so many gifts for your child?A.there B.this C.that D.It参考答案:1.D【详解】考查代词词义辨析。

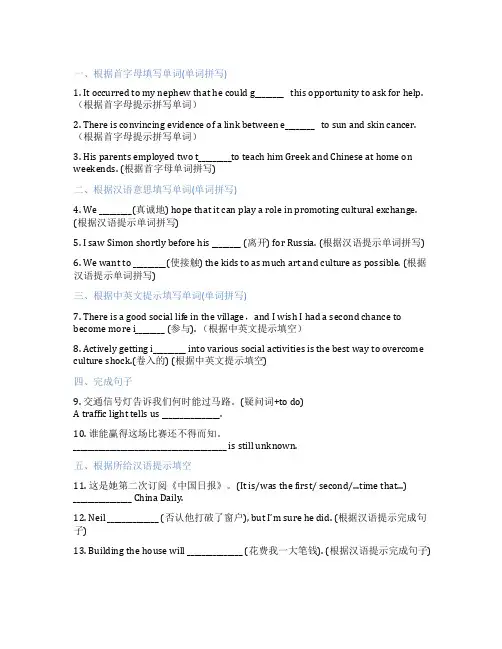

一、根据首字母填写单词(单词拼写)1. It occurred to my nephew that he could g________ this opportunity to ask for help. (根据首字母提示拼写单词)2. There is convincing evidence of a link between e________ to sun and skin cancer. (根据首字母提示拼写单词)3. His parents employed two t_________to teach him Greek and Chinese at home on weekends. (根据首字母单词拼写)二、根据汉语意思填写单词(单词拼写)4. We _________(真诚地) hope that it can play a role in promoting cultural exchange. (根据汉语提示单词拼写)5. I saw Simon shortly before his ________ (离开) for Russia. (根据汉语提示单词拼写)6. We want to _________(使接触) the kids to as much art and culture as possible. (根据汉语提示单词拼写)三、根据中英文提示填写单词(单词拼写)7. There is a good social life in the village,and I wish I had a second chance to become more i________ (参与). (根据中英文提示填空)8. Actively getting i_________ into various social activities is the best way to overcome culture shock.(卷入的) (根据中英文提示填空)四、完成句子9. 交通信号灯告诉我们何时能过马路。

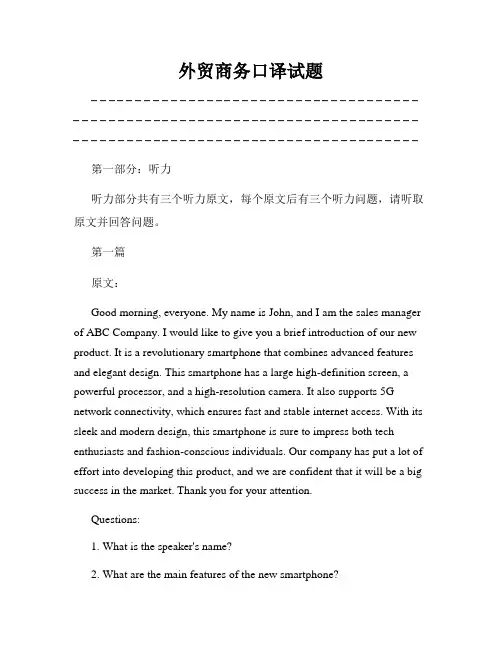

外贸商务口译试题⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯第一部分:听力听力部分共有三个听力原文,每个原文后有三个听力问题,请听取原文并回答问题。

第一篇原文:Good morning, everyone. My name is John, and I am the sales manager of ABC Company. I would like to give you a brief introduction of our new product. It is a revolutionary smartphone that combines advanced features and elegant design. This smartphone has a large high-definition screen, a powerful processor, and a high-resolution camera. It also supports 5G network connectivity, which ensures fast and stable internet access. With its sleek and modern design, this smartphone is sure to impress both tech enthusiasts and fashion-conscious individuals. Our company has put a lot of effort into developing this product, and we are confident that it will be a big success in the market. Thank you for your attention.Questions:1. What is the speaker's name?2. What are the main features of the new smartphone?3. What kind of individuals will be interested in this smartphone?第二篇原文:Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to today's conference on international trade. The topic of my speech is the potential impact of the recent trade tariffs on global economy. As you may know, several countries have imposed tariffs on imported goods in an attempt to protect their domestic industries. While these measures may benefit the domestic industries in the short term, they can also lead to negative consequences in the long run. Trade tariffs can escalate trade disputes between countries and hinder the growth of global trade. They can also increase the prices of imported goods, which may cause inflation and put a burden on consumers. Therefore, it is important for countries to consider the potential ramifications of trade tariffs and seek mutually beneficial solutions. Thank you.Questions:1. What is the topic of the speech?2. What are the potential consequences of trade tariffs?3. What should countries do in light of the potential ramifications of trade tariffs?第三篇原文:Good afternoon, everyone. My name is Lisa, and I am an interpreter specializing in business meetings. Today, I will share with you some tips for effective communication in international business settings. Firstly, it is essential to be well-prepared for the meeting by researching the business culture, customs, and etiquette of the target country. This knowledge will help you avoid misunderstandings and show respect to your counterparts. Secondly, always use clear and simple language to convey your ideas. Avoid using complex jargon or technical terms that might confuse non-native speakers. Thirdly, be attentive and actively listen to your counterparts. This not only demonstrates your respect but also helps you better understand their perspectives. And finally, be patient and flexible when facing cultural differences or language barriers. Remember that effective communication is key to building successful business relationships. Thank you.Questions:1. What is the speaker's occupation?2. What are some tips for effective communication in international business settings?3. Why is effective communication important in business relationships?⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯⎯第二部分:口语口语部分共有三个对话,每个对话后有三个问题,请根据对话内容回答问题。

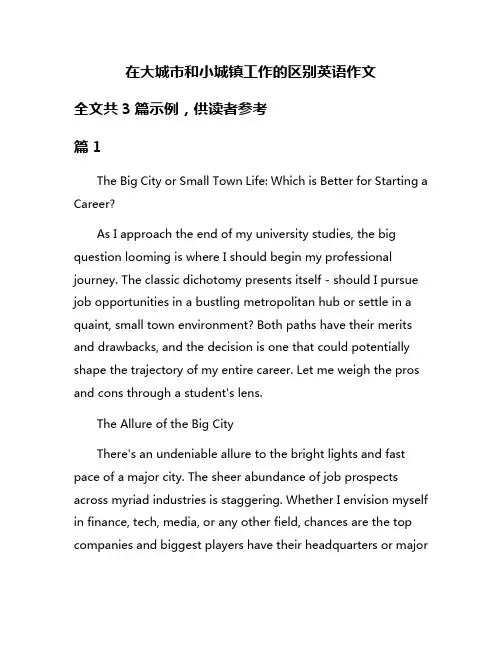

在大城市和小城镇工作的区别英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1The Big City or Small Town Life: Which is Better for Starting a Career?As I approach the end of my university studies, the big question looming is where I should begin my professional journey. The classic dichotomy presents itself - should I pursue job opportunities in a bustling metropolitan hub or settle in a quaint, small town environment? Both paths have their merits and drawbacks, and the decision is one that could potentially shape the trajectory of my entire career. Let me weigh the pros and cons through a student's lens.The Allure of the Big CityThere's an undeniable allure to the bright lights and fast pace of a major city. The sheer abundance of job prospects across myriad industries is staggering. Whether I envision myself in finance, tech, media, or any other field, chances are the top companies and biggest players have their headquarters or majoroffices in cities like New York, Los Angeles, Chicago or San Francisco.This translates to more options straight out of college, giving me a wider net to cast as I scout for that ideal entry-level position. The competition is undoubtedly fiercer in these talent pools, but the potential rewards are immense – from higher starting salaries to rapid career growth and skill development under the tutelage of industry leaders.Beyond the professional sphere, the energy and diversity of a cosmopolitan city are immensely appealing to a young, culturally-curious mind like my own. The food scene, the arts, the nightlife – all shine brighter under the city's brilliant marquees. As someone craving a smorgasbord of experiences in this pivotal stage of life, it's hard not to be infatuated with the city's boundless potential for exploration and self-discovery.The Comforts of Small Town LivingYet the relentless pace and fast-tracked lifestyle of the city can exact a toll, particularly in those formative early career years. Perhaps the biggest sell of small-town living is the easing of certain pressures – the lower cost of living, the short commutes, the slower and more grounded rhythms of daily life.While job opportunities may be fewer in number, the responsibilities and expectations are likely more manageable starting out. This could allow for more work-life balance and the mental breathing room to find one's footing. There's something immensely attractive about being a bigger fish in a smaller pond, shouldering pivotal roles early on rather than being just another cog in a giant corporate machine.Finances are a perennial concern for young professionals, and stretching an entry-level paycheck goes much further in a small town setting compared to the often exorbitant living costs of major cities. Suddenly, goals like home ownership or starting a family don't seem like mere pipe dreams postponed into the distant future.And while small towns may lack the glamor and trendiness of metropolitan hubs, they more than make up for it with an inherent sense of community, security and local charm. Having grown up in a close-knit suburb myself, I can attest to the simpler joys of knowing your neighbors, feeling a part of the fabric of your town, and being able to fully disconnect from the frenzy of urban life whenever you please.A Hybrid Solution?Of course, the realities and preferences vary from person to person. For some, the fast-track of the big city is the only path that inspires them, while others crave the sanctity of a quieter existence from day one. Fortunately, in our age of remote work, the binary is no longer so absolute. Increasingly, young graduates can secure city jobs and salaries while retaining a small-town quality of life.I know several people who landed plum positions with major tech companies, for instance, but opt to live in cheaper locales. They simply commute into the office once or twice a week as needed, reaping the benefits of both worlds. Talk about having your cake and eating it too!Ultimately, as is often the case, moderation and balance may be the ideal path forward for me. My plan is to start out in a major metro area like New York or San Francisco, fully immersing myself in the hustle and upward mobility of the city in those critical early career years. Gaining that foundation and making the industry connections could pay massive dividends.Once I've accumulated the requisite experience and capital, however, I could see myself embracing a more laid-back lifestyle in the suburbs or even a secondary city. There, I could start a family, enjoy a lower cost of living, and not have to sacrifice myhard-earned career trajectory thanks to our increasingly connected world.Striking this balance is easier envisioned than executed, of course. There are no guarantees or certainties, only the constant weighing of priorities篇2The Stark Contrasts of the Urban vs Rural Work LifeAs a student about to graduate and enter the workforce, one of the biggest decisions I face is whether to pursue job opportunities in a bustling metropolitan area or a quaint small town. This choice will undoubtedly shape my quality of life, career trajectory, and overall life experiences. Through speaking with professionals from both realms, as well as rigorously researching the advantages and drawbacks, I've come to realize that the disparities between the big city and small town work environments are quite stark.The most obvious distinction lies in the sheer pace and level of activity. Major cities like New York, London, or Tokyo are veritable powerhouses of productivity and commerce. The streets teem with a relentless flow of pedestrians, taxis whizzing by carrying high-powered executives and professionals. Apalpable buzz of urgency permeates the air as billions in capital change hands each day. For the ambitious career-driven individual, this kinetic atmosphere can be incredibly stimulating and motivating. One feels a part of something huge, a tiny cog in the great machine that powers the world's economy.In stark contrast, life in a rural town feels almost suspended in time, moving at a languid and sedate rhythm. Main streets are populated not with power brokers but with familiar friends and neighbors chatting idly, perhaps pausing to share the latest town gossip. Stores and businesses open late, close early, and move at an unhurried snail's pace. While some may find this ambiance suffocating, others view it as a much-needed respite from the frenetic rat race of city life.Beyond the difference in pace, the availability of career opportunities and potential for professional growth are major considerations. Large cosmopolitan centers are rich with possibility, home to corporate headquarters, startups, nonprofits, and virtually every industry one篇3The Contrast Between the City Hustle and Small Town LifeAs a student, I've had the opportunity to experience working in both a major metropolitan area and a quaint, rural town. While each environment offers its own unique advantages and challenges, the stark contrast between the two has been truly eye-opening. In this essay, I'll delve into the distinct experiences of working in a big city versus a small town, drawing upon my personal observations and insights.The Big City GrindWorking in a city like New York or Los Angeles is an exhilarating, fast-paced adventure. The sheer density of people, buildings, and opportunities can be both electrifying and overwhelming. One of the most notable aspects of city life is the constant buzz of activity that permeates the air. From the moment you step out onto the bustling sidewalks, you're immersed in a whirlwind of sights, sounds, and energy.In the city, the job market is vast and diverse, offering a multitude of career paths to explore. Whether you're interested in finance, technology, media, or any other industry, there's a wealth of companies and organizations to choose from. This abundance of options can be both empowering and daunting, as the competition for coveted positions is often fierce.The pace of work in the city is relentless, with a constant pressure to perform and meet tight deadlines. Multitasking and time management become essential skills as you navigate the demands of your job while also dealing with the logistical challenges of commuting, finding affordable housing, and juggling a myriad of other responsibilities.Despite the intensity, there's an undeniable allure to the city's vibrant cultural scene. World-class museums, theaters, restaurants, and nightlife are just a stone's throw away, offering endless opportunities for exploration and entertainment. The diversity of the city's population also adds richness to the experience, exposing you to a melting pot of cultures, perspectives, and lifestyles.The Small Town CharmIn stark contrast to the city's frenetic pace, working in a small town offers a slower, more relaxed way of life. The sense of community and familiarity is palpable, with friendly faces greeting you at every turn. The job market in a small town may be more limited, but there's often a stronger sense of loyalty and camaraderie among colleagues.One of the most appealing aspects of small-town living is the shorter commute times and the ability to truly disconnectfrom work once you're home. Instead of battling traffic jams and crowded public transportation, you can enjoy a leisurely drive through picturesque landscapes or even walk or bike to your workplace.The work environment in a small town tends to be more intimate and collaborative. With smaller teams and a closer-knit community, there's often a greater sense of accountability and personal investment in your work. Colleagues may become more like an extended family, sharing not only professional goals but also personal milestones and interests.While the cultural offerings in a small town may not be as vast as those in a major city, there's a charm in the local festivals, community theaters, and family-owned restaurants that dot the landscape. The slower pace of life allows for a deeper appreciation of the simple pleasures, such as enjoying a quiet evening on the porch or exploring the nearby hiking trails.The Cost of Living EquationOne of the most significant differences between working in a big city and a small town is the cost of living. In major metropolitan areas, the expenses for housing, transportation, and basic necessities can be staggering. Rent for a modest apartment can easily consume a substantial portion of yourpaycheck, leaving little room for savings or discretionary spending.In contrast, the cost of living in a small town is often significantly lower. Housing is more affordable, and everyday expenses like groceries and utilities tend to be less expensive. This financial breathing room can alleviate some of the stress associated with making ends meet and allow for a more comfortable lifestyle.The Pros and ConsAs with any life decision, there are pros and cons to consider when choosing between working in a big city or a small town. The city offers unparalleled career opportunities, cultural richness, and a constant stream of excitement and stimulation. However, it also comes with higher costs, longer commutes, and a more frenetic pace that can be draining over time.On the other hand, small-town living provides a sense of community, a slower pace, and a more affordable cost of living. Yet, the job market may be more limited, and the cultural offerings may not be as diverse as those found in a major metropolitan area.Ultimately, the choice between the city hustle andsmall-town life comes down to personal preferences and priorities. Some thrive on the energy and ambition of the city, while others find solace in the tranquility and familiarity of a close-knit community.Striking a BalanceFor many, the ideal scenario may lie in finding a balance between the two worlds. Perhaps living in a smaller city or suburb, within commuting distance of a major metropolitan area, could offer the best of both worlds. This compromise allows for access to the job opportunities and cultural amenities of the city, while still providing a more affordable and relaxed living environment.Alternatively, some individuals may choose to embrace the nomadic lifestyle, alternating between stints in the city and periods of respite in a quieter, rural setting. This approach can help to avoid burnout and maintain a sense of balance and perspective.ConclusionWhether you find yourself drawn to the pulsating energy of the city or the serene charm of a small town, the contrastbetween these two environments is undeniable. Each offers its own unique rewards and challenges, shaping our experiences and perspectives in profound ways.As a student, exploring these contrasting worlds has been an invaluable learning experience, providing insight into the diverse lifestyles and work cultures that exist within our society. Ultimately, the choice between the city hustle and small-town life is a deeply personal one, shaped by our individual values, goals, and definitions of success and fulfillment.。

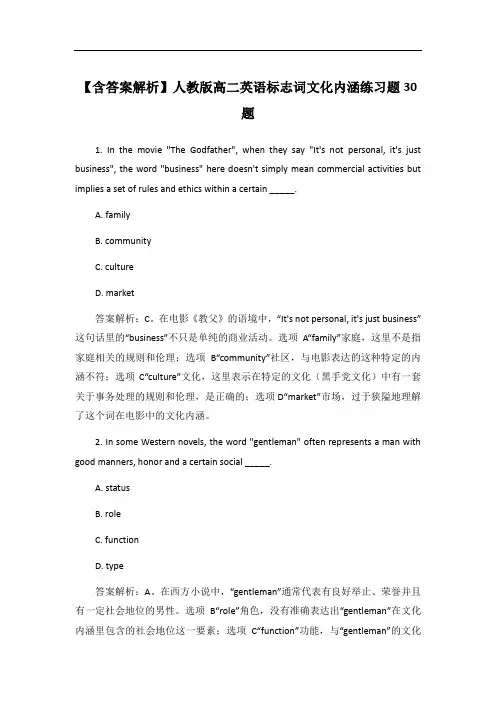

【含答案解析】人教版高二英语标志词文化内涵练习题30题1. In the movie "The Godfather", when they say "It's not personal, it's just business", the word "business" here doesn't simply mean commercial activities but implies a set of rules and ethics within a certain _____.A. familyB. communityC. cultureD. market答案解析:C。

在电影《教父》的语境中,“It's not personal, it's just business”这句话里的“business”不只是单纯的商业活动。

选项A“family”家庭,这里不是指家庭相关的规则和伦理;选项B“community”社区,与电影表达的这种特定的内涵不符;选项C“culture”文化,这里表示在特定的文化(黑手党文化)中有一套关于事务处理的规则和伦理,是正确的;选项D“market”市场,过于狭隘地理解了这个词在电影中的文化内涵。

2. In some Western novels, the word "gentleman" often represents a man with good manners, honor and a certain social _____.A. statusB. roleC. functionD. type答案解析:A。

在西方小说中,“gentleman”通常代表有良好举止、荣誉并且有一定社会地位的男性。

选项B“role”角色,没有准确表达出“gentleman”在文化内涵里包含的社会地位这一要素;选项C“function”功能,与“gentleman”的文化内涵无关;选项D“type”类型,比较宽泛,不能确切体现“gentleman”所蕴含的社会地位的文化内涵,所以A正确。

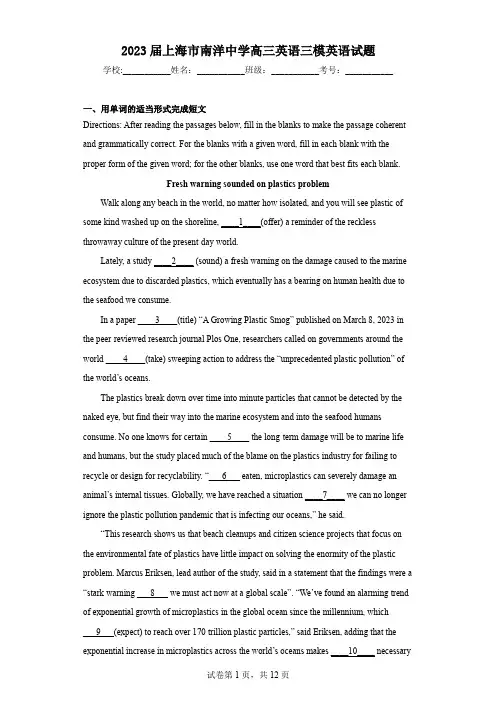

2023届上海市南洋中学高三英语三模英语试题学校:___________姓名:___________班级:___________考号:___________一、用单词的适当形式完成短文Directions: After reading the passages below, fill in the blanks to make the passage coherent and grammatically correct. For the blanks with a given word, fill in each blank with the proper form of the given word; for the other blanks, use one word that best fits each blank.Fresh warning sounded on plastics problemWalk along any beach in the world, no matter how isolated, and you will see plastic of some kind washed up on the shoreline, ____1____(offer) a reminder of the reckless throwaway culture of the present-day world.Lately, a study ____2____ (sound) a fresh warning on the damage caused to the marine ecosystem due to discarded plastics, which eventually has a bearing on human health due to the seafood we consume.In a paper ____3____(title) “A Growing Plastic Smog” published on March 8, 2023 in the peer-reviewed research journal Plos One, researchers called on governments around the world ____4____(take) sweeping action to address the “unprecedented plastic pollution” of the world’s oceans.The plastics break down over time into minute particles that cannot be detected by the naked eye, but find their way into the marine ecosystem and into the seafood humans consume. No one knows for certain ____5____ the long-term damage will be to marine life and humans, but the study placed much of the blame on the plastics industry for failing to recycle or design for recyclability. “___6___ eaten, microplastics can severely damage an animal’s internal tissues. Globally, we have reached a situation ____7____ we can no longer ignore the plastic pollution pandemic that is infecting our oceans,” he said.“This research shows us that beach cleanups and citizen science projects that focus on the environmental fate of plastics have little impact on solving the enormity of the plastic problem. Marcus Eriksen, lead author of the study, said in a statement that the findings were a “stark warning ___8___ we must act now at a global scale”. “We’ve found an alarming trend of exponential growth of microplastics in the global ocean since the millennium, which___9___(expect) to reach over 170 trillion plastic particles,” said Eriksen, adding that the exponential increase in microplastics across the world’s oceans makes ____10____ necessaryto “bring in an age of corporate responsibility for the entire life of the things they make”.二、选用适当的单词或短语补全短文Directions: Complete the following passage by using the words in the box. Each word canHuizhou heritage comes to lifeIt was a natural choice for veteran Huang Yu, after serving in the army and owning a business in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, for years, to go back to his hometown in Xidi village, Huangshan, Anhui province, in 2016. He took over the homestay his parents opened when he was a middle school student.In 2000, Xidi and the nearby Hongcun village were declared World Heritage sites by UNESCO for their outstanding _____11_____ of rural architecture dating to the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. Now, walking along the bluestone streets in Xidi or Hongcun, visitors can appreciate the distinctive Huizhou-style houses, _____12_____ white walls, dark tiles and layered horse-head gables, and feel like they are immersed in a traditional Chinese ink painting.This level of preservation could not be achieved without the participation of local residents. According to Huang, this awareness is not new - since all streets and alleys in Xidi are paved with bluestone, ____13____, street dealers carrying wares on shoulder poles were forbidden from letting their poles touch the ground in order to protect the bluestone.A local folk _____14_____ says: “One is not lucky to be born in Huizhou. At 13 or 14 he is kicked out of his hometown to make a living.” It _____15_____ at the struggles onceendured by the people of Huizhou. Toward the end of the Ming Dynasty, a group of Huizhou merchants became famous, trading in salt, wood and tea, and working as pawnbrokers (当铺老板) with a reputation for _____16_____ and honesty.“Some folk customs have been retained and newly _____17_____ toward tourism, offering glimpses into the lives of the ancient Huizhou people.”These customs are revived as a demonstration for tourists, and to maintain the _____18_____ of traditional culture. Zhang Wangnan, director of the China Huizhou Culture Museum in Huangshan says “This____19____ the combination of intangible with tangible cultural heritage.”He further suggests that the old Huizhou villages explore and find their own unique, marketable themes. “Each of them should find a _____20_____local feature, whether it is tea, chrysanthemum or rapeseed flowers, and then make it the theme of the village, so that they can give full play to their distinctive cultural charm.”三、完形填空Most forms of conventional advertising — print, radio and broadcast television — have been losing ground to online ads for years; only billboards, dating back to the 1800s, and TV ads are holding their own. Such out-of-home advertising, as it is known, is anticipatedincludes the LCD screens found in airports and shopping malls, by 16%. Such ads draw viewers’ attention from phones and cannot be skipped or _____22_____, unlike ads online.Billboard owners are also _____23_____ the location data that are pouring off people’s smartphones. Information about their owners’ locations and online browsing gets collected and sold to media owners. They then use these data to work out when different groups — “business travellers”, say — walk by their ads. That_____24_____ is added to insights into traffic, weather and other external data to produce highly relevant ads. DOOH _____25_____ can deliver ads for coffee when it is cold and iced drinks when it is warm.Such _____26_____ works particularly well when it is combined with “programmatic” advertising methods, a term that describes the use of data to automate and improve ads. In the past year billboard owners such as Clear Channel and jcDecaux have _____27_____ programmatic platforms which allow brands and media buyers to select, purchase and place ads in minutes, rather than days or weeks. It is said that outdoor ads will increasingly bebought like online ones, based on audience and views as well as_____28_____.That is possible because billboard owners claim to be able to _____29_____ how well their ads are working, even though no “click-through” rates are involved. Data firms can tell advertisers how many people walk past individual advertisements at particular times of the day. Advertisers can estimate how many individuals _____30_____ to an ad for a handbag then go on to visit a nearby shop (or website) and buy the product. Such metrics make outdoor ads more_____31_____, automated and measurable, argues Michael Provenzano, co-founder of Vistar Media, an ad-tech firm in New York.However, the outdoor-ad revolution is not free of _____32_____ . The collection of mobile-phone data raises privacy concerns. And _____33_____ of the online-ad business for being vague, and occasionally dishonest, may also be targeted at the DOOH business as it becomes bigger and more complex. The industry is ready to_____34_____ such concerns, says Jean-Christophe Conti, chief executive of VIOOH, a media-buying platform. One of the_____35_____ of following the online-ad pioneers, he notes, is learning from their mistakes.21.A.shrink B.grow C.strand D.emerge 22.A.obtained B.blocked C.separated D.arranged 23.A.making progress in B.getting engaged in C.becoming part of D.taking advantage of24.A.value B.record C.knowledge D.intervention 25.A.opponents B.providers C.learners D.instructors 26.A.adding B.collecting C.targeting D.producing 27.A.profiled B.forbidden C.cleared D.launched 28.A.marketing B.evolution C.location D.branding 29.A.measure B.wonder C.notice D.mount 30.A.devoted B.opposed C.related D.exposed 31.A.concept-based B.data-driven C.customer-driven D.research-based 32.A.stress B.conflict C.injury D.problem 33.A.aspects B.demands C.criticisms D.details 34.A.address B.install C.reflect D.emphasize 35.A.benefits B.difficulties C.challenges D.conditions四、阅读理解Cathy and Wayne N. who have been married five years are in their late 20’s and childless. The last time a member of Cathy’s family asked, “When are you going to start a family?” Her answer was “We are a family!”Cathy and Wayne belong to a growing number of young married couples who are deciding not to have children. A recent survey showed that in the last five years the percentage of wives aged 25 to 29 who did not want children had almost doubled and among those 18 to 24 it had almost tripled. What lies behind this decision which seems to fly in the face of biology and society?Perhaps the most public outspoken childless couple are Ellen Peck, author of The Baby Trap, and her husband, William, an advertising executive who is president of the National Organization for Non-parents. The Pecks insist neither they nor the organization is against parenthood, just against the social pressures that push people into parenthood whether it is what they really want and need or not.“It’s a life-style choice,” Ellen says. “We chose freedom and spontaneity (自发性), privacy and leisure. It’s also a question of where you want to give your efforts — within your own family or in the larger community. This generation faces serious questions about the continuity of life and as well as its quality. Our grandchildren may have to buy tickets to see the last redwoods or line up to get their oxygen ration. There are men who complain about being caught in a traffic jam for hours on their home to their five kids but can’t make the association between the children and the traffic jam. In a world seriously threatened by the consequences of overpopulation we’re concerned with making life without children acceptable and respectable. Too many children are born as a result of cultural pressure. And the results show up in the statistics on divorce and child-abuse.”Her husband adds, “Every friend, relative and business associate is pressuring you to have kids ‘and find what you’re missing.’ Too many people discover too late that what they were missing was something they were totally unsuited for.”And Ellen again, “From the first doll to soap operas to cocktail parties, the pressure is always there to be parents. But let’s take a 1ook at the rate of parental failure. Perhaps parenthood should be regarded as a specialized occupation like being a doctor. Some people are good at it and they should have children; others aren’t, and they should feel they haveother alternatives.”36.By asking “When are you going to start a family”, the member of Cathy’s family meant “_______”.A.when are you going to move into a new houseB.when are you going to buy a houseC.when are you going to get marriedD.when are you going to have a child37.In the second paragraph, the phrase “to fly in the face of” most probably means _______. A.to popularizeB.to followC.to go againstD.to strengthen38.According to the third paragraph, the Pecks hold that _______.A.all young couples should not give in before the social pressuresB.no pressure should be imposed on couples about parenthoodC.strong measures should be taken to help childless couplesD.childless couples face no problems of divorce or child-abuse39.According to Ellen,what has caused many of the problems we face today? A.Overpopulation.B.Environmental pollution.C.Cultural progress.D.Life-style choice.What is PayQwiq?PayQwiq is a fast and secure payment service that helps you go quickly through the Tesco checkout. It lets you add your credit or debit card details to the app so you can use your smartphone to pay for your shopping with just one scan. Not only that but it collects your Clubcard points automatically. This means you can now go wallet-free in all UK Tesco stores. So why not give it a go? It only takes a moment to download and you will receive these benefits:Collect your Clubcard points automaticallyPay for your weekly shop up to £250Use payQwiq offline, even with no signalTrack your spending in TescoSign up to PayQwiq and collect 100 extra Clubcard points for each week you pay with the app, for up to 5 weeks—that’s up to 500 extra points.Available to new customers who sign up by 3 September 2018 and make all payments by 31 October 2018. One offer per customer. Only one qualifying deal per week will collect the extra points. Additional payments in the same week will not receive extra points. Clubcard points will be added to a future Clubcard statement.How does it work?Head to the App Store or Google Play to download the PayQwiq app.As soon as you’ve added your card details, you’ll be ready to shop using just your phone.And there’s no need to worry about your bank details being stored on your phone—they’re all securely protected in our data centers. So not only it is quicker and easier, it’s safer too.40.If customers use PayQwiq in UK Tesco stores, they can _______.A.get Clubcard points automatically B.pay for their weekly shop without limit C.budget their everyday spending D.win 500 extra points at a time 41.From the passage we can learn that _______.A.users must sign up by 3 September 2018B.users needn’t add their payment card informationC.PayQwiq can guarantee both convenience and safetyD.PayQwiq can be downloaded only from the App Store42.What is the purpose of this passage?A.To stress the importance of PayQwiq.B.To popularize the use of PayQwiq. C.To describe the feasibility of PayQwiq.D.To ensure the safety of PayQwiq.The most important determining factor of success or failure—at work and in life—is self-awareness, the ability to understand who we are, how others see us, and how we fit into the world.For millions of years, the ancestors of humans evolved painfully slowly. However, about 150,000 years ago there was an explosive development in the human brain where, amongother things, we gained the ability to examine our own thoughts, feelings and behaviors, as well as to see things from another’s point of view. Not only did this transformation create the foundation for art, spiritual practices and language, but it came with a survival advantage for our ancestors, who had to work together in order to survive.Though we may not face the same day-to-day threats to our existence, self-awareness is no less critical. There is strong scientific evidence that people who know themselves and how others see them are happier. They are smarter, superior students. They raise more mature children. They also tend to be more creative, confident and less aggressive.But for most people it is easier to choose self-delusion (自我欺骗) rather than the cold hard truth. Our increasingly “me” focused society makes it easier to fall into this trap. Recent generations have grown up in a World obsessed with self-esteem (自负), constantly being reminded of their special qualities. Not only are our assessments often flawed (有缺陷), but we are usually terrible judges of our own performance and abilities—from leadership skills to achievements at school and work. What’s scary is that the least competent people are usually the most confident in their abilities.How can we avoid this fate? We must work on two specific types of insight. Internal self-awareness is an inward understanding of our passions and aspirations, strengths and weaknesses and so on. And external self-awareness, knowing how others see you, means understanding yourself from the outside in.For those looking to gain true insight, remember that other people often see us more objectively than we see ourselves and that self-examination can have hidden trap that make insight actually impossible.43.The first three paragraphs mainly talk about _______.A.the significance of self-awareness in human survival and advancementB.the sharp contrast between self-awareness of today and the pastC.the necessity of a shift in self-awareness to satisfy the needs todayD.the intelligence gap between modern men and their ancestors44.What’s the problem with “me” focused society nowadays?A.People’s performance and abilities are overlooked.B.Competent people tend to be unconfident of their leadership skills.C.It’s difficult to obtain an objective assessment of ourselves.D.Modern people fail to bring their special qualities into full play.45.Which of the following is an example of external self-awareness?A.You listen to the comments about you from others.B.You are fully aware of your strengths and weaknesses.C.You reflect your behaviors thoroughly every day.D.You carefully compare your behavior with that of others.46.In the last paragraph, the author suggests that we should _______.A.develop true insight to judge people more objectively B.try to avoid the trap set by othersC.gain more insight by means of self-examination D.pay more attention to externalself-awareness五、六选四Why Do Cats Love Boxes So Much?There is an object that’s pretty much guaranteed to arouse your cat’s interest. That object, as the Internet has so thoroughly documented, is a box. Any box, really. Like many other really strange things cats do, science hasn’t fully cracked this particular feline (猫科的) mystery.____47____ In fact, when you look at all the evidence together, it could be that your cat may not just like boxes, he may need them.The box-and-whisker plotUnderstanding the feline mind is extremely difficult. Still, there’s a sizable amount of behavioral research on cats who are, well, used for other kinds of research. These studies have been taking place for more than 50 years and they make one thing quite clear:____48____This is likely true for a number of reasons, but for cats in stressful situations, a box or some other type of separate enclosure can have a strong impact on both their behavior and physiology.Ethologist Claudia Vinke of Utrecht University in the Netherlands is one of the latest researchers to study stress levels in shelter cats. Working with domestic cats in a Dutch animal shelter, Vinke provided hiding boxes for a group of newly arrived cats while keeping another group from them entirely. ____49____ In effect, the cats with boxes got used to theirnew surroundings faster, were far less stressed early on, and were more interested in interacting with humans.The ‘If it fits, I sits’ principleSome feline observers will note that in addition to boxes, many cats seem to pick other odd places to relax. Some curl up in a bathroom sink. ____50____ This brings us to the other reason why your cat may like particularly small boxes: It’s really cold out.So there you have it: Boxes are insulating, stress-relieving, comfort zones—places where cats can hide, relax, sleep, and occasionally launch a surprise attack against the huge, unpredictable apes they live with.A.Your furry companion obtains comfort and security from enclosed spaces.B.Others prefer shoes, bowls, shopping bags, coffee mugs, empty egg cartons, and other small, enclosed spaces.C.She found a significant difference in stress levels between cats that had the boxes and those that didn’t.D.A box, in this sense, can often represent a safe zone, a place where sources of anxiety, hostility (恶意), and unwanted attention simply disappear.E.So rather than work things out, cats tend to simply run away from their problems or avoid them altogether.F.Thankfully, behavioral biologists and veterinarians have come up with a few interesting explanations.六、概要写作51.Directions: Read the following passage. Summarize the main idea and the main point(s) of the passage in no more than 60 words. Use your own words as far as possible.The Crucial Role of Early Childhood EnvironmentThe environment we are in affects our moods, ability to form relationships, effectiveness in work or play — even our health. In addition, the early childhood environment has a very crucial role in children’s learning and development for two important reasons.First, young children are in the process of rapid brain development. In the early years, the brain develops more synapses (神经元的突触) or connections than it can possibly use. Those that are used by the child form strong connections, while the synapses that are not usedgradually disappear. Children’s experiences help to make this determination. The National Scientific Council of the Developing Child compares the development of the brain to constructing a house, stating, “Just as a lack of the right materials can result in blueprints that change, the lack of appropriate experiences can lead to alterations in genetic plans.” Because children’s experiences are limited by their surroundings, the environment we provide for them has a crucial impact on the way the child’s brain develops.The second reason that the early childhood environment has such a strong role in children’s development is because of the amount of time children spend in these environments. Many children spend a large portion of their wakeful hours in early childhood setting. For example, a baby beginning child care will spend up to 12,000 hours in the program. This is more time than he will spend in both elementary and secondary schools. Children will typically spend another 4,000 hours in kindergarten through third grade classrooms.Anita Rui Olds, a well-known environmental designer, believes that we should design our early childhood environments for miracles, not minimums. She states: “Children are miracles. Believing that every child is a miracle can transform the way we design for children’s care. When we invite a miracle into our lives, we prepare ourselves and the environment around us. We make it our job to create, with great respect and gratitude, a space that is worthy of a miracle!___________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________________________________ _____七、汉译英(整句)52.建议家长们尽量多花点时间陪伴孩子。

中考英语文化产业发展策略单选题40题1. The Hollywood in the United States is famous for its movie industry. Which of the following is a major part of the movie - making process in Hollywood?A. Only actingB. Acting, directing and special effectsC. Just writing scriptsD. Only filming答案解析:B。

好莱坞的电影制作是一个复杂的过程,包含多个重要部分。

选项A只提到表演,这只是电影制作的一部分,不够全面。

选项C仅仅是编写剧本,这虽然是电影制作的前期重要环节,但不是全部。

选项D只强调拍摄,而忽略了其他重要部分。

而选项B提到了表演、导演和特效,这三者都是好莱坞电影制作过程中的主要部分,涵盖了从表演呈现到幕后创作以及视觉效果制作等多方面,能全面地体现电影制作过程。

2. Manga is an important part of Japanese culture industry. Which of the following is a characteristic of Manga?A. Only black - and - white picturesB. Real - life stories without any imaginationC. Vivid characters and diverse storylinesD. Only for children答案解析:C。

日本漫画(Manga)的特点是有生动的人物形象和多样的故事情节。

选项A说只有黑白图片是不准确的,现在有很多彩色的漫画。

选项B说没有任何想象的现实生活故事不符合漫画的特点,漫画往往充满想象力。

选项D说只适合儿童也是错误的,日本漫画受众广泛,有适合不同年龄段的作品。

中考英语文化创意产业的创新驱动单选题40题1. In the cultural and creative industry, a music concert is a popular form. Which of the following words can best describe the atmosphere of a lively music concert?A. SilentB. BoringC. EnergeticD. Sad答案:C。

解析:本题考查对文化创意产业中音乐演唱会氛围的理解以及形容词的含义。

A选项“Silent”表示安静的,音乐演唱会通常是热闹的,所以A不符合。

B选项“Boring”是无聊的,与热闹的演唱会氛围相悖。

C选项“Energetic”表示充满活力的,能很好地描述音乐演唱会的热闹氛围,符合题意。

D选项“Sad”是悲伤的,也不符合音乐演唱会的氛围。

同时这也考查了学生对这几个形容词基本含义的掌握。

2. Art exhibitions are an important part of the cultural and creative industry. What do people usually do in an art exhibition?A. Sing loudlyB. Dance happilyC. Appreciate artworksD. Play sports答案:C。

解析:本题考查文化创意产业中艺术展览相关的行为以及对词汇的理解。

A选项“Sing loudly”是大声唱歌,通常不在艺术展览中进行。

B选项“Dance happily”是快乐地跳舞,也不是艺术展览中的常见行为。

C选项“Appreciate artworks”表示欣赏艺术作品,这是人们在艺术展览中通常做的事,符合题意。

D选项“Play sports”是做运动,与艺术展览毫无关系。

这题主要涉及对这些动词短语含义的掌握。

巴菲特英文名言沃伦·巴菲特,全球著名的投资商,在2008年的《福布斯》排行榜上财富超过比尔盖茨,成为世界首富。

下面店铺为大家带来巴菲特英文名言,欢迎大家阅读!巴菲特英文名言1、我只做我完全明白的事。

i only do i fully understand。

2、今天的投资者不是从昨天的增长中获利的。

investors today are not profit from yesterday's growth。

3、如果发生了核战争,请忽略这一事件。

in the event of a nuclear war, please ignore this event。

4、利率就像是投资上的地心引力一样。

interest rates is like the gravity on the investment。

5、任何不能永远发展的事物,终将消亡。

any things cannot forever development, will eventually die。

6、用我的想法和你们的钱,我们会做得很好。

with my thoughts and your money, we can do well。

7、永远不要问理发师你是否需要理发。

don't ever ask the barber whether you need a haircut。

8、在别人恐惧时我贪婪,在别人贪婪时我恐惧。

when others fear i greed, the greedy when i fear。

9、如开始就成功,就不要另觅他途。

success, such as start, do not have to find his way。

10、投资对于我来说,既是一种运动,也是一种娱乐。

investment for me, is not only a sport, is also a kind of entertainment。

Unit 2 Bridging Cultures*注意:有时需要对单词加以变化。

1.Decide if the sentence is compound (look for and, but, or, etc.) or (复杂的)(look forwho, when, where, etc.).2.“I was very excited but also quite nervous. I didn’t know what to expect,” Xie Lei(记起;忆起).3.Xie Lei is studying for a business (资格) at a university in China.4.My (野心;抱负) is to set up a business in China after graduation.5.Xie Lei chose to live with a host family, who can help with her (适应;改编) to thenew culture.6.When I miss home, I feel (安慰;抚慰) to have a second family.7.Her (导师) explained that she must acknowledge what other people had said if she(引用;引述) their ideas.8.Xie Lei also found many courses included students’ (参加) in class as part of thefinal result.9.Students need to generate ideas, offer examples, apply concepts, and raise questions, as wellas give (报告;陈述).10.What surprised her was that she found herself (大声说;明确表态) in class after justa few weeks.11.Now halfway through her exchange year, Xie Lei (舒服自在;如在家里) in the UK.12.(参加;从事) in British culture has helped.13.As well as studying hard, I've been (包含;涉及) in social activities.14.While I’m learning about business I'm also acting as a cultural (信使) building abridge between us.15.We will follow Xie Lei’s progress in later (版次;一期), but for now we wish her allthe best.16.Actively getting involved in various social activities is the best way to overcome (文化冲击).17.Adaptation to a new culture can be difficult. However, you need to step out of your comfort(地带;区域).18.The first few weeks there were absolutely (无法抗拒的) because everything was sodifferent.19.I felt confused and lost. I also suffered from (思乡病).20.I became more (积极的) and I’m also a lot more ambitious.21.The (顾问) talked about maintaining (合情理的) (期望) whenstudying abroad.22.Who will be the successful (申请人) for the summer job at the law (公司)?23.(暴露) to another culture and its people can give exchange students great (洞察力) into the world.24.He had made great friends here -- friends that he will still remember long after his(离开).25.Understanding the (背景) will help you understand the type and content of thecommunication more clearly.26.I suppose it was difficult to (抓紧) the tones at first.27.In the past few decades, there has been a (巨大的;突然的) increase in the number ofpeople studying abroad.28.Tuition fees and living (花费) are much more expensive than at home.29.Another important factor to consider is the (巨大的) pressure that comes withstudying abroad.30.Some may struggle and suffer from culture shock when learning how to (表现) innew (环境).31.Other students are not (成熟的) enough to handle the challenges by themselves andmay become (沮丧的).32.As China has (繁荣;大爆发), the educational environment has improvedsignificantly.33.Helping to educate young people will contribute to the economy and further (加强)our country.34.To sum up, one cannot (否认) the fact that studying abroad has its disadvantages.35.There are no great difficulties for a person who is brave, (乐观的), and willing towork hard!36.The education you (获得) and the experiences you have will change you for thebetter.37.Studying abroad also helps you to gain a global (角度)and improve your general(能力).38.Chinese students can be seen as cultural (使者) promoting friendship betweennations.39.(合作) with people from diverse cultural backgrounds helps us view the world fromdifferent (角度).40.China’s global (前景), with projects such as the (腰带;地带) and Road(倡议;新方案), has helped us make connections across the world.41.S tudents who want to study abroad must consider their parents’ (预算).42.(一般来说), if you care for others (真诚地), they will trust yougradually.43.(依我看来), he is still not mature enough to how to behave on suchoccasions.44.(据我所知), she considered the current situation (合逻辑地) anddecided to be optimistic about the (结果).45.(总之), I don’t deny that social activities took up too much time.答案:complex,recalled,qualification,ambition,adaptation,comforted,tutor,cited,participation,presentations,speaking up,feels at home,Engaging,involved,messenger,editions,culture shock,zone,overwhelming,homesickness,motivated,advisor,reasonable,expectations,applicant,firm,Exposure,insights,departure,setting,grasp,dramatic,expenses,tremendous,behave,surroundings,mature,depressed,boomed,strengthen,deny,optimistic,gain,perspective,competence,envoy,Cooperating,angles,outlook,Belt,Initiative,budget,Generally speaking,sincerely,As far as I am concerned,As far as I know,logically,outcome,In summary。

商务综合英语二学习通课后章节答案期末考试题库2023年1.the amount of something参考答案:volume2.应受,应得,值得参考答案:deserve3.The new drug will not be put on the market it has proved safe onhumans.参考答案:until4.Not until the day before yesterday _________to give a speech at the meeting.参考答案:did he agree5.The Great Wall ________ all over the world. It attracts lots of tourists fromabroad each year.参考答案:is known6.the transfer from one conveyance to another for shipment参考答案:transshipment7.Mary says this is the( ) decision she has ever made in her career life.参考答案:worst8.By the time you came back, all the letters _________.参考答案:had been typed out9.It is required that anyone applying for a driver's license __________ a set oftests.参考答案:take10.There is no evidence he was on the site of the murder.参考答案:that11.It is reasonable for people to pursue a career in fields related theirfavorite hobbies.参考答案:to12.样品,试样参考答案:sample13.适用的参考答案:applicable14.It was because of his good performance at the interview he got the jobwith the big company.参考答案:that15.填好参考答案:fillout;fillin16.According to the time table, the train for Beijing at 9:10 p.m. fromMonday to Friday.参考答案:leaves17.天然的,未加工的参考答案:crude18.The proposal at the meeting now is of great importance to ourdepartment.参考答案:being discussed19.choosable; not compulsory参考答案:optional20.Scientists should be kept __________ of the latest developments in theirresearch areas.参考答案:informed21.Immigrants have to adapt themselves culturally and physically to the newsurroundings ____ they have move参考答案:into which22.快速的,专门的参考答案:express23.以。

矿产资源开发利用方案编写内容要求及审查大纲

矿产资源开发利用方案编写内容要求及《矿产资源开发利用方案》审查大纲一、概述

㈠矿区位置、隶属关系和企业性质。

如为改扩建矿山, 应说明矿山现状、

特点及存在的主要问题。

㈡编制依据

(1简述项目前期工作进展情况及与有关方面对项目的意向性协议情况。

(2 列出开发利用方案编制所依据的主要基础性资料的名称。

如经储量管理部门认定的矿区地质勘探报告、选矿试验报告、加工利用试验报告、工程地质初评资料、矿区水文资料和供水资料等。

对改、扩建矿山应有生产实际资料, 如矿山总平面现状图、矿床开拓系统图、采场现状图和主要采选设备清单等。

二、矿产品需求现状和预测

㈠该矿产在国内需求情况和市场供应情况

1、矿产品现状及加工利用趋向。

2、国内近、远期的需求量及主要销向预测。

㈡产品价格分析

1、国内矿产品价格现状。

2、矿产品价格稳定性及变化趋势。

三、矿产资源概况

㈠矿区总体概况

1、矿区总体规划情况。

2、矿区矿产资源概况。

3、该设计与矿区总体开发的关系。

㈡该设计项目的资源概况

1、矿床地质及构造特征。

2、矿床开采技术条件及水文地质条件。