Decentralization and Local Governance in China’s Economic Transition

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:194.61 KB

- 文档页数:34

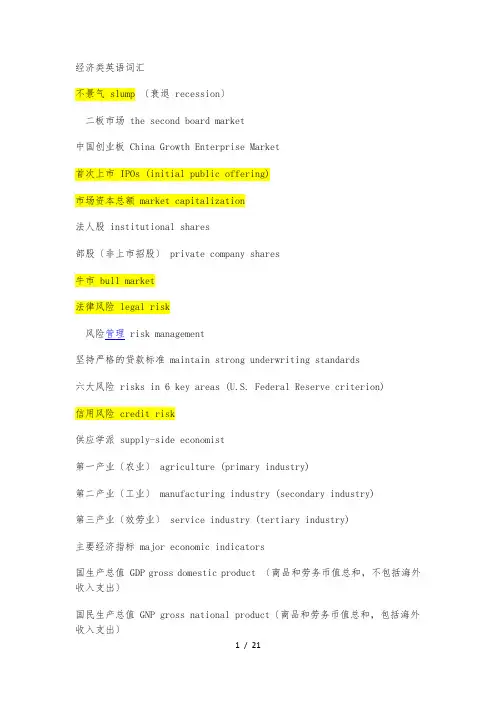

经济类英语词汇不景气 slump 〔衰退 recession〕二板市场 the second board market中国创业板 China Growth Enterprise Market首次上市 IPOs (initial public offering)市场资本总额 market capitalization法人股 institutional shares部股〔非上市招股〕 private company shares牛市 bull market法律风险 legal risk风险管理 risk management坚持严格的贷款标准 maintain strong underwriting standards六大风险 risks in 6 key areas (U.S. Federal Reserve criterion)信用风险 credit risk供应学派 supply-side economist第一产业〔农业〕 agriculture (primary industry)第二产业〔工业〕 manufacturing industry (secondary industry)第三产业〔效劳业〕 service industry (tertiary industry)主要经济指标 major economic indicators国生产总值 GDP gross domestic product 〔商品和劳务币值总和,不包括海外收入支出〕国民生产总值 GNP gross national product〔商品和劳务币值总和,包括海外收入支出〕人均国生产总值 GDP per capita宏观经济 macro economy互助基金 mutual fund扩大需 expand domestic demand改善居民心理预期 inspire the general public's confidence in the future needs鼓励增加即期消费 encourage more immediate consumption长期国债 long-term treasury bonds支付国债利息 to service treasury bonds财政赤字和债务 deficits and the national debt按原口径计算 calculate on the base line按不变价格计算 calculate at constant price按可比价格计算 calculate at comparable price列入财政预算支出 listed in the fiscal budget结售汇制度 the system of exchange, settlement and sales经常项目顺差 favorable balance of current account, surplus of current account开办人民币业务 engage in Renminbi (RMB) business出口退税制度 the system of refunding taxes on exported goods保证金台帐制度 Deposit account system for processing trade分期付款 pay by installment保值储蓄 inflation-proof bank savings抵押贷款 collateralised loans住房抵押贷款 residential mortgage loan货币主义者 monetarist计划经济 planned economy指令性计划 mandatory plan技术密集型 technology intensive大规模生产 mass production经济林 cash tree跟踪审计 follow-up auditing流动性风险 liquidity risk操作风险 operational risk部审计 internal audit抛售 bear sales配套政策 supporting policies中国人民银行〔中央银行〕The People’s Bank of China〔central bank〕四大国有商业银行 4 major state-owned commercial banks中国银行 Bank of china中国工商银行 Industrial and Commercial Bank of China〔〕and中国建立银行 Construction Bank of China中国农业银行 Agricultural Bank of China招商银行 China Merchants Bank疲软股票 soft stock配股 allotment of shares实际增长率 growth rate in real terms年均增长率 average growth rate per annum投资回报率 rate of return on investment外贸进出口总额 total foreign trade value实际利用外资 incoming overseas capital (investment) in place消费价格指数 consumer price index (CPI)零售价格指数 retail price index 〔RPI〕生活费用价格总指数 total price index of living cost生活费用 income available for living expenses扣除物价因素 in real terms / on inflation-adjusted basis居民储蓄存款residents’ bank s avings deposit恩格尔系数〔食品开支占总支出的比例〕 Engel coefficient基尼系数〔衡量地区差异〕 Gini coefficient购置力平价法 purchasing power parity (PPP) 〔衡量使用不同货币的两个国家或地区的经济水平、收入水平的一种计算法,用相等的汇率比拟两种货币各自的国购置力〕片面追求开展速度 excessive pursuit of growth泡沫经济 bubble economy 经济过热 overheating of economy通货膨胀 inflation实体经济 the real economy经济规律 laws of economics市场调节 market regulation优化资源配置 optimize allocation of resources规模经营优势 advantage of economies of scale劳动密集型 labor intensive市场风险 market risk收紧银根 tighten up monetary policy适度从紧的财政政策 moderately tight fiscal policy信用紧缩 credit crunch加强国有商业银行部资金调度 In state commercial banks, internal capital allocation should be improved.合理划分贷款审批权限 Limits of authority for examining and approving loans should be rationally defined.保证有市场、有效益、守信用企业的流动资金贷款 ensure floating capital loans for well-performing and trustworthy enterprises which turn out the right products for the right markets启动民间投资 attract investment from the private sector适销对路的产品 the right products / readily marketable products国有企业 state-owned enterprises (SOEs)集体企业 collectively-owned (partnership) enterprises私营企业 private businesses民营企业 privately-run businesses中小企业 small-and-medium-sized enterprises三资企业〔中外合资、中外合作、外商独资〕 overseas-invested enterprises; foreign-invested enterprises (Chinese-overseas equity joint ventures,Chinese-overseas contractual joint ventures, wholly foreign- owned enterprises)存款保证金 guaranty money for deposits货币回笼 withdrawal of currency from circulation吸收游资 absorb idle fund经常性贷款 commercial lending经常性支出 operating expenses再贷款 re-lending; subloan支持国有大型企业和高新技术企业上市融资 support large state-owned enterprises and high and innovative technology companies in their efforts to seek financing by listing on the stock market改制上市 An enterprise is re-organized according to modern corporate system so that it will get listed on the stock market.进一步规和开展证券市场 further standardize and develop the securities market增加直接融资比重 increase the proportion of direct financing完善股票发行上市制度 improve the system for IPO and listing on stock markets中国证监会 China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC)证券交易所市 Shenzhen Stock Exchange证券交易所 Shanghai Stock Exchange综合指数 composite index纳斯达克〔高技术企业板〕 NASDAQ 〔National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotation主板市场 the main board通货紧缩 deflation中国巨大的市场潜力将逐步转化为现实的购置力 The huge market potential that China enjoys will be turned into tangible purchasing power.适应市场经济需要的法律法规体系还不够健全 The regulatory and legal system is not well established as to adapt to the demand of market economy.经济管理体制可能会出现一些不适应 The economic management system may not be readily adapted to the changes.一些行业和企业可能会受到冲击 Some sectors of economy and some businesses may be adversely affected.立足中国国情,发挥自身优势 proceed from national conditions in China and bring our advantages into play扬长避短,趋利避害,迎接经济全球化的挑战 foster strengths and circumvent weaknesses and rise to the challenge of economic globalization瓶颈制约 bottleneck constraints放权让利 decentralization and interest concessions (in late 1980s and early 1990s)深化改革intensify reform; deepen one’s commit ment to reform配套改革 supporting (concomitant) reforms配套资金 counterpart funds; local funding of提高经济效益 improve economic performance; increase economic returns讲求社会效益 value contribution to society; pay attention to social effect加速国民经济信息化 develop information-based economy accelerate IT application in economy拉动经济增长 fuel economic growth利改税 substitution of tax payment for profit delivery费改税 transform administrative fees into taxes债转股 debt-to-equity swap头寸宽裕〔头寸紧缺〕 in an easy position (tight position)产业 sunrise industry招标投标制 the system of public bidding for project充分发挥货币政策的作用 give full play to the role of monetary policy实施积极的财政政策 follow a pro-active fiscal policy向银行增发国债,扩大投资 The government issued additional treasury bonds to banks to increase investment.再注资 recapitalization放松银根 to ease monetary policy信息经济 IT economy外向型经济 export-oriented economy信息时代 information age全球化 globalization 〔全球性globality〕信誉风险 reputational risk风险评级 risk rating到期不还贷 default on a loan资不抵债 insolvency; be insolvent亚洲金融危机 Asian financial crisis (1997-98)投资〔贷款〕组合 investment (loan) portfolio外汇储藏充足 sufficient foreign exchange reserves中国金融业问题 problems with financial sector in China储蓄比例过高 the excessively large proportion of savings in the money supply国有企业产负债率过高 high leverage ratio of the state-owned enterprises,国有独资商业银行不良资产比例过高 high ratio of non-performing loans of the state commercial banks少数中小存款金融机构不能支付到期债务 insolvency of a handful of small and medium-sized financial institutions不良贷款 non-performing loans防和化解金融风险 address financial risks提高企业借贷和行使民事责任的能力improve enterprises’ creditworthiness and ability to fulfil their civil liabilities监事会 supervisory board实行慎重会计制度 adopt prudential accounting standards五级分类法划分贷款质量 the five-category asset classification approach金融资产管理公司 financial asset management companies别离和收回不良资产 substantially reduce the ratio of non-performing assets分业管理、规模经营 business segregation, economy of scale规金融机构市场退出制度 improve the market exit mechanism for financial institutions政策性银行 state policy-related bank国家开展银行 State Development Bank知识经济 knowledge-based economy网络经济 Internet-based networked economy指导性计划 guidance plan社会主义市场经济〔中国〕 socialist market economy社会市场经济〔德国〕 social market economy新经济〔美国〕 new economy中国光大银行 Everbright Bank of China中国民声银行 China Minsheng Banking Corporation Ltd.实业银行 CITIC Industrial Bank中国进出口银行 China EXIM Bank汇丰银行 Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HKSBC)金融监管 financial supervision中国人民银行法Law of the People’s Bank of China商业银行法 Law of Commercial Banks保险法 Law of Insurance证券法 Law of Securities巴塞尔原那么 Basel Core Principles监管对象的行为有问题、管理机制不健全 problems of superv ised entities’ behavior and the unsound internal governance mechanism风险意识 consciousness of risk prevention事前监管 proactive regulation and supervisionaccount number 帐目编号depositor 存户pay-in slip 存款单a deposit form 存款单a banding machine 自动存取机to deposit 存款deposit receipt 存款收据private deposits 私人存款certificate of deposit 存单deposit book, passbook 存折credit card 信用卡principal 本金overdraft, overdraw 透支to counter sign 双签to endorse 背书endorser 背书人to cash 兑现to honor a check 兑付to dishonor a check 拒付to suspend payment 止付check 支票check book 支票本order check 记名支票bearer check 不记名支票crossed check 横线支票blank check 空白支票rubber check 空头支票check stub, counterfoil 票根cash check 现金支票traveler's check 旅行支票check for transfer 转帐支票outstanding check 未付支票canceled check 已付支票forged check 伪支票Bandar's note 庄票,银票banker 银行家president 行长savings bank 储蓄银行Chase Bank 大通银行National City Bank of New York 花旗银行Hongkong Shanghai Banking Corporation 汇丰银行Chartered Bank of India, Australia and China 麦加利银行Banque de I'Indo Chine 汇理银行central bank, national bank, banker's bank 中央银行bank of issue, bank of circulation 发行币银行commercial bank 商业银行,储蓄信贷银行member bank, credit bank 储蓄信贷银行discount bank 贴现银行exchange bank 汇兑银行requesting bank 委托开证银行issuing bank, opening bank 开证银行advising bank, notifying bank 通知银行negotiation bank 议付银行confirming bank 保兑银行paying bank 付款银行associate banker of collection 代收银行consigned banker of collection 委托银行clearing bank 清算银行local bank 本地银行domestic bank 国银行overseas bank 国外银行unincorporated bank 钱庄branch bank 银行分行trustee savings bank 信托储蓄银行trust company 信托公司financial trust 金融信托公司unit trust 信托投资公司trust institution 银行的信托部credit department 银行的信用部commercial credit company(discount company) 商业信贷公司〔贴现公司〕neighborhood savings bank, bank of deposit 街道储蓄所credit union 合作银行credit bureau 商业兴信所self-service bank 无人银行land bank 土地银行construction bank 建立银行industrial and commercial bank 工商银行bank of communications 交通银行mutual savings bank 互助储蓄银行post office savings bank 邮局储蓄银行mortgage bank, building society 抵押银行industrial bank 实业银行home loan bank 家宅贷款银行reserve bank 准备银行chartered bank 特许银行corresponding bank 往来银行merchant bank, accepting bank 承兑银行investment bank 投资银行import and export bank (EXI MBA NK) 进出口银行joint venture bank 合资银行money shop, native bank 钱庄credit cooperatives 信用社clearing house 票据交换所public accounting 公共会计business accounting 商业会计depreciation accounting 折旧会计computerized accounting 电脑化会计general ledger 总帐subsidiary ledger 分户帐cash book 现金出纳帐cash account 现金帐journal, day-book 日记帐,流水帐bad debts 坏帐investment 投资surplus 结余idle capital 游资economic cycle 经济周期economic boom 经济繁荣economic recession 经济衰退economic depression 经济萧条economic crisis 经济危机economic recovery 经济复inflation 通货膨胀deflation 通货收缩devaluation 货币贬值revaluation 货币增值international balance of payment 国际收支favorable balance 顺差adverse balance 逆差hard currency 硬通货soft currency 软通货international monetary system 国际货币制度the purchasing power of money 货币购置力money in circulation 货币流通量note issue 纸币发行量national budget 国家预算national gross product 国民生产总值public bond 公债stock, share 股票debenture 债券treasury bill 国库券debt chain 债务链direct exchange 直接〔对角〕套汇indirect exchange 间接〔三角〕套汇cross rate, arbitrage rate 套汇汇率foreign currency (exchange) reserve 外汇储藏foreign exchange fluctuation 外汇波动foreign exchange crisis 外汇危机discount 贴现discount rate, bank rate 贴现率gold reserve 黄金储藏money (financial) market 金融市场stock exchange 股票交易所broker 经纪人commission 佣金bookkeeping 簿记bookkeeper 簿记员an application form 申请单bank statement 对帐单letter of credit 信用证strong room, vault 保险库equitable tax system 等价税那么specimen signature 签字式样banking hours, business hours 营业时间share, equity, stock 股票、股权negotiable share 可流通股份treasury /government bond 国库券/政府债券closed-end securities investment fund 封闭式证券投资基金open-end securities investment fund 开放式证券投资基金market capitalization 市值mark-to-market 逐日盯市clearing and settlement 清算/结算put / call option 看跌/看涨期权rights issue/offering 配股ADR(American Depository Receipt)美国存托凭证/存股证GDR(Global Depository Receipt) 全球存托凭证/存股证institutional investor 机构投资者proprietary trading 自营market manipulation 市场操纵IPO(Initial Public Offering)新股初始公开发行securities 证券premium 溢价share capital 股本composite index 综合指数capital market 资本市场liquidity 流通性highly-leveraged institutions(HLI) 高杠杆交易机构subscribe 申购underwriter承销商road show 路演primary market 一级市场information disclosure 信息披露blue chips 蓝筹股gilt-edged bond 金边债券rating agency 评级机构credit trading 信用交易open/close a position 建/平仓bond, debenture, debts 债券convertible bond 可转换债券corporate bond 企业债券fund manager 基金经理/管理公司fund custodian bank 基金托管银行p/e (price/earning) ratio 市盈率payment versus delivery 银券交付commodity/financial derivatives 商品/金融衍生产品margins, collateral 保证金bonus share 红股dividend 红利/股息retail / private investor 个人投资者/散户broker/dealer 券商insider trading/dealing 幕交易prospectus招股说明书merger and acquisition收购兼并warrant 认股权证raised capital/proceeds 筹资component index 成份指数turnover rate 换手率monetary market 货币市场hedge fund 对冲基金self-regulatory organization(SRO)自律组织issuer 发行人intermediary 中介机构secondary listing 第二上市secondary market 二级市场controlling shareholder 控股股东red chips红筹股junk bond 立即债券securities loan 融券financing 融资(编辑:admin)21/ 21。

把权力关进制度的笼子(Cage with power in the system)Cage with power in the systemThe party's eighteen report pointed out, "to promote the operation of power, open, standardized, so that power in the sun."". General secretary Xi Jinping in the two plenary session of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection speech made it clear that the establishment of an effective disciplinary mechanism, prevention mechanisms and security mechanisms, the power into the system cage". In recent years, the municipal government started in key areas and key positions, innovation, mode of supervision to restrict reform power, explore a new path specification and power balance.Tighten the power "reins", regulate the volume rate change. In depth investigation and analysis of typical cases on the basis of the introduction of the "urban management of construction land volume rate adjustment management approach.". This is a way to increase the "threshold" provisions may apply for adjustment of volume rate was only involved in the public interest or policy adjustment situation; two is the strict procedures, to organize experts to conduct feasibility studies and trial, involving closely connected people, held public hearings, and then submitted to the government for approval without objection; three is tightening clear power, adjust the volume rate shall be discussed and decided by the executive meeting of the municipal government, any other units and individuals have the right to decide the change of planning. In view of the existing planning in risk management, municipal government further forward the control mark, the timely introduction of the "Regulations" urban planning managementtechnical specification, planning and design stage and construction stage project approval rate calculation rules and related building height control, construction area and volume calculation standard, effective control of discretion. In the planning departments of internal construction project is a copy of certification and approval, after the issuance volume of track inspection, the completion of planning verification work undertaken by different offices, so as to "double insurance" and mutual supervision and restriction on the volume rate of the verification checks. At the same time, the establishment of the volume rate management filing system, adjust the volume change rate must be detailed registration, and reported to the discipline inspection and supervision organs for the record.Clear operation process, "sunshine" sell land. Municipal government to regulate the land market as a breakthrough, creatively established the "net transfer, Yaohao host, live broadcast, tracking the transfer of land management, prior to listing, listed in the transaction, after three stages of implementation of process control. "Net transfer", refers to the plots listed before, first and then transfer to resettlement, the "hair" into the "net"; "Yaohao management", in the land auction, the auction host randomly selected from the library, produced by the host site by Yaohao; "live", is a video of the auction live recordings, and by the NPC deputies and CPPCC members and the public mission site supervision, city land market network television and broadcast; "tracking" refers to the plots listed transactions, the contract management, the completion of the application online,real-time supervision and tracking management of land development. In addition, the municipal government for landacquisition and sensitive issue stipulates: "net listing" in the "not tearing down", "how to dismantle" must have the consent of more than 90% residents agree; all must be listed plots of land compensation, resettlement, land use rights to recover, contradiction at the "four place", adjusting or firmly not listed.Weaving mechanism, "fence", scientific planning and approval. 2011,The municipal government promulgated the work regulations of the Municipal Planning Commission, and made clear new regulations for the planning committee members, planning review, design review and rules of procedure. The "Regulations" provisions, submit the plan to the system architecture design scheme optimization, public buildings, large buildings along the main road and the city landscape river must submit at least three sets by different creative designers' scheme than the election, plan must reflect the surrounding built environment, especially important projects should be made to model the spatial relationship the expression of the building. The name of the creative designer and design unit will be inscribed on the building. In project bidding, the owners of the exit mechanism, the project construction unit tendering, bidding registration, take back, judges the random, the owners do not send personnel to participate in the evaluation, make the evaluation process more standardized, more fair competition.Investigation and separation of checks and balances, law enforcement open and transparent. The city land department formulated the "on the further strengthening of urban landmanagement related work opinions", "land and resources law enforcement measures", focus on the establishment of "prevention first, find timely, effective and long-term mechanism to stop the investigation in place". "Opinions" on the batch before, during, after the regulatory requirements have been standardized, and clearly establish, investigate, separate and breach of administrative behavior handling mechanism.Standard practice of reform of public power restriction on tackling the problem, realized three source of Governance: one is for the prevention of corruption from the source for new institutional arrangements; two is provided to ensure the new mechanism for preventing and controlling the source of social contradictions; three is the city social management by law to provide the source to strengthen a new experience. Specification and balance of public power is an important means to promote the city social management of the rule of law, the innovation and practice a beneficial exploration for the social management of the city into the rule of law, but also provides a new experience for the entire administrative norms and balance of public power, bring us three inspirations:(1) the rule of law is the fundamental way to check and balance the public power. Decentralization and balance is an effective way to regulate public power operation of human society find, decentralization and balance is also a kind of power operation mode, in this mode of operation, the balance of decentralization is the premise, not decentralization can not be achieved to the restriction of power. The rule of law through decentralization and balance, to ensure that decision-making,execution and supervision of mutual restriction and mutual coordination and form a closed relationship, to ensure the people's supervision power and public power operation and standardization, effectively solve the powerful people how to exercise the right of the post.(two) the rule of law is the most reliable cage. Hold the key links and key positions, easy to breed corruption on the one hand, in accordance with the principle of the balance of powers, from horizontal and vertical respectively on the power of reasonable decomposition, the chief and Deputy between, between the upper and lower levels, between departments and between the staff according to the law to use power, do have the right to have the responsibility, right subject to supervision, prevent the excessive concentration of power; on the other hand, a clear division of responsibilities, the power holders should bear the responsibility and must abide by the law and ethics together, and establish accountability mechanisms. Simultaneous,Through the construction of the rule of law, established a reasonable structure, scientific configuration, strict procedures and effective control of power supervision mechanism, weaving a reliable cage.(three) rule of law is the most perfect image of a famous city. Throughout the world, with international competitiveness and influence of the city has become a city, a very important aspect, namely the rule of law has become the cornerstone of city operation, city citizens believe in the city, the spirit of the core pillar. It can be said that the world famous city is afamous cultural city, an ecological city, a powerful city and a famous city under the rule of law.。

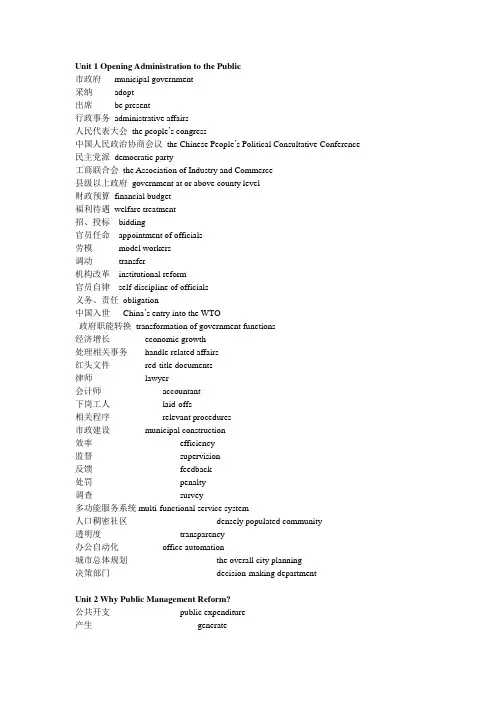

Unit 1 Opening Administration to the Public市政府municipal government采纳adopt出席be present行政事务administrative affairs人民代表大会the people’s congress中国人民政治协商会议the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference 民主党派democratic party工商联合会the Association of Industry and Commerce县级以上政府government at or above county level财政预算financial budget福利待遇welfare treatment招、投标bidding官员任命appointment of officials劳模model workers调动transfer机构改革institutional reform官员自律self-discipline of officials义务、责任obligation中国入世China’s entry into the WTO政府职能转换transformation of government functions经济增长economic growth处理相关事务handle related affairs红头文件red-title documents律师lawyer会计师accountant下岗工人laid-offs相关程序relevant procedures市政建设municipal construction效率efficiency监督supervision反馈feedback处罚penalty调查survey多功能服务系统multi-functional service system人口稠密社区densely populated community透明度transparency办公自动化office automation城市总体规划the overall city planning决策部门decision-making departmentUnit 2 Why Public Management Reform?公共开支public expenditure产生generate监督成本monitoring costs均衡equilibrium现状status quoUnit 3 Reform of the Administration and Local Public Services: Introduction decentralization 分权化centralization 集权化liberalization 自由化devolution权力下放regional authorities 地方当局integration一体化instability 不稳定local tax revenue 地方税收municipal 市政的private enterprise 私营企业democracy 民主local autonomy地方自治conventional practice 传统做法public sector公共部门privatization私有化governance治理empowerment放权augment扩大、增加、增长accountability负责任Unit 4 State and MarketI. Words and expressionsMacroeconomic宏观经济的Microeconomic微观经济的Judicial司法的;法院的new entry 初入,新进入entrepreneur 企业家gross national income(GNI) 国民收入总值per capita人均per capita gross national income: gross national product divided by the number of people living in the country.gross national product(GNP)国民生产总值: the total value of goods and services produced in a country’s economy, including income from abroad.gross domestic product(GDP)国内生产总值: the total value of goods and services produced in a country’s economy, not including income from abroad.rating 考核、定级levy 征收incentive 刺激、鼓励marginal tax rate边际税率: the amount by which tax revenue increase per unit increase invalue in a taxed activity.Distance education远程教育monopoly垄断generate 产生;导致access to接近;进入;接近(进入)的方法(权利、机会等)dramatically 大幅度地account for说明(原因等)impose on 强加meet the requirement/ the need/ the demand…on average 平均enhance提高、增加、增强stagnant停滞的、不流动的;萧条的、不景气的vibrant活跃的、充满活力的present:a.1)existing or happening now 现在的、目前的e.g.The present situation is quite unfavourable to us.2)at an event, or in a place 出席的、在场的e.g.When it happened, I was not presentn.1)gift 礼物e.g.The boy was asked to wait for a present.2)the period of time时间段e.g.We must learn to live in the presentv.1)give sb. sth. formally or officially 赠送、呈献e.g.John was the guest of honour and presented the awards.2)offer sth for people to consider or judge递交、呈递e.g.The commission presented its report in April.3)show sb.or sth. in a particular way so that people have a particular opinion about them 上演e.g.The film presents a disturbing image of youth culture.take over: He took over the company at the death of his father.take in: It’s easy for children to take in milk.This shirt is too long for me, please take it in.Why is it so easy for people to be taken in?take to: He took to the girl/ smoking when he was only sixteen.take up: He took up stamp-collecting as his hobby.Reading takes up 20 percent of his time at home at night.be critical to 关键的comparable/ comparativeensure: We can ensure that the project will be finished in time.insure sth. against sth.: You can insure your house against fire.assure sb. of sth: I can assure you of the security of the information.take responsibility forUnit 6 Developing and Designing Performance Management Performance绩效Effectiveness有效Efficiency有效Morale士气Forge打造Integrative整合的,整体的Holistic总体的,全部的Intent 意图,目的Bring sth. into line with sth. else使协调起来,使一致Unitarist一元论Be at odds with与有争执;与不一致Accommodate使适应;容纳,接纳Plurality众多,许多Deficient缺乏的,不足的Predominant占优势;主要的,突出的In essence实质上Appraisal评估Be mindful of留心,注意,不忘记Implementation贯彻,履行Be consistent with 与一致Stance姿态,态度Allow for考虑到Incorporate结合;体现Encompass围绕,包围;包含Infuse向……注入,向……灌输;泡制,浸渍Implicit含蓄的;内含的,固有的Intensive加强的,集中的;深入细致的Articulate能说话的,表达地清楚有力At large未被捕,逍遥自在;详尽地;普遍的,一般的,代表整个的Unit 8 The Economic Perspective for the People’s republic of China disparity 不一致,不同coastal 沿海的interior内陆的financial sector 经济部门surge 汹涌澎湃,冲浪buoyant有浮力的,轻快的fixed asset investment 固定资产投资housing mortgage loan住宅抵押贷款western region development strategy西部开发战略disposable income 可分配收入,税后收入trigger 激发,引起ameliorate 改善,改进,改良consecutive 连续的integrated一体化的,完整的jurisdiction 权限procurement 获得the general tariff level关税总水平rebate 回扣,折扣aggravate deflationary pressure加重通货紧缩压力fiscal stimulus 财政激励constrain抑制contemplate 期待,反复打算bailout应急贷款,紧急援助fledge缺乏经验的,初出茅庐的tapers逐渐减少,逐渐停止offset抵消momentum力量,动量,势头project 规划,设计excess capacity产能过量entrant进入者,新加入者resource-extensive 资源粗放型labour-intensive劳动密集型honoring contracts执行合同auditing standard 审计准则,审计标准disclosure揭发address提到,提出degradation品质下降pro-亲exacerbate 加剧vulnerability易受攻击,脆弱institute 实行,建立,开始,创立regulatory规章制度conform to使一致,使符合resilient有弹性的regime政体,政治,统治Unit 9 China seeks Peaceful Growth Holistically全面地shake off摆脱multiplication scenario乘法情境negligible微不足道的mega大的(兆)provoking使人烦恼的abundant丰富的,充裕的magnitude大cohesion粘着力,结合slacken放松,松懈make further strides更进一步blaze用光照耀detach from分开,分离foster养育,促进initiative首创精神,积极性,主动usher引领wrestle斗争,搏斗weigh up估量tap开发hefty异常大的bring into play发挥adhere to坚持hegemony霸主contend for竞争,斗争testify证明,证实strive for努力,奋斗,力求unswerving直的,不偏离的draw on利用Unit 10 The Largest Recipient of Foreign Capital conglomerate联合大企业stipulation条款,项目franchise特许overhaul详细检查sluggish缓慢的hamper妨碍,阻碍given假设disposal income税后收入。

理论述评全球范围内行政区划调整实证研究的述评———主题、理论与发现何鉴孜【摘要】战后世界各国频繁出现的地方政府合并和拆分现象为理解中国的行政区划调整提供了重要的背景和参照。

当前,基于这些现象而开展的国外实证研究呈现出怎样的理论图景?关于行政区划调整所带来的影响,国外研究者都在争论哪些理论命题?论文系统收集了2000—2020年间发表在英文学术期刊上的相关实证研究,从区划调整对政府内部、对经济社会以及对政府-社会关系三个方面的影响出发,归纳和对比了既有的研究。

文章发现,国外研究总体上并不支持区划合并能够推动地方经济发展的假说,同时对于规模经济效应在地方财政和公共服务效率上的体现意见不一。

相对而言,研究者较为一致地认为区划合并容易带来更疏远的政府-社会关系,使经济体量和政治地位相对弱势的被合并地区进一步边缘化,还可能引发地方政府在财政上“搭便车”的行为。

文章最后对比了中外研究在兴趣和结论上的异同,主张研究者把更多精力放在区划调整如何对不同区域、不同对象产生差异性影响的问题上,同时呼吁行政区划调整的决策过程应更加重视利益的平衡与协调。

【关键词】行政区划调整 实证研究 述评【中图分类号】D63 【文献标识码】A【文章编号】1674-2486(2022)04-0175-20行政区划调整不仅是中国公共管理学界的热点,也是全球其他国家所普遍面临的问题。

从一级行政区的数量看,战后世界除了拉美国家整体相对稳定外,其余多数国家都曾经历或正在经历不同幅度的变动。

其中,撒哈拉以南的非洲国家所出现的“政府碎片化”(governmentfragmentation)趋势在国际上尤为引人何鉴孜,复旦大学全球公共政策研究院青年副研究员。

感谢复旦大学为本研究提供的科研启动经费,感谢学生助理徐艺丹、宋学彬、陈懿人、李若愚为文章写作提供的帮助,同时感谢匿名评审专家和编辑部提供的宝贵修改意见。

◆公共行政评论·2022·4关注(Grossmanetal ,2017;Pierskalla,2019)。

分散主义英语Decentralism, also known as decentralization, is a political and socio-economic ideology that advocates the dispersion or distribution of power, authority, and decision-making processes away from a central authority or government. It emphasizes the importance of local control and autonomy, promoting the idea of self-governance and grassroots democracy.In a decentralized system, power and responsibilities are shared among multiple smaller units or local communities rather than concentrated in a single authority. This allows for better representation of diverse interests and needs of different regions or groups within a society. Decentralism aims to empower individuals and local communities, enabling them to have a greater say in matters that directly affect them.One of the key advantages of decentralism is that it helps to foster innovation and creativity. By empoweringlocal communities to make decisions and solve problems on their own, there is greater potential for experimentation and the development of unique solutions that are tailored tolocal contexts. Decentralized systems can encourage entrepreneurship and local economic development by providing opportunities for individuals and communities to take charge of their own affairs.Decentralism also promotes accountability and transparency. When power is distributed among multiple units, it becomes easier to hold decision-makers accountable for their actions. Local communities have a better understanding of their own needs and can closely monitor the actions of their representatives. This helps to prevent corruption and ensure that decisions are made in the best interest of the community.Furthermore, decentralism can foster social cohesion and harmony. By giving individuals and local communities greater control over their own affairs, it encourages active participation in the decision-making process and promotes a sense of ownership and responsibility. This can enhancesocial bonds and cooperation among community members, leading to stronger and more resilient societies.However, it is important to strike a balance between decentralization and the need for coordination and unity at higher levels. While decentralism promotes local autonomy, it should not undermine the overall functioning of a larger system. Cooperation and collaboration between different units are necessary to address issues that require collective action, such as national defense, environmental protection, and economic stability.In conclusion, decentralism promotes the dispersion of power and decision-making, empowering local communities andindividuals. It fosters innovation, accountability, social cohesion, and participation in the decision-making process. However, it should be implemented with care, ensuring that coordination and cooperation are maintained at higher levels to address common challenges and ensure the smooth functioning of the overall system.。

China in Transition in Management Leadership StyleChina is a country of old and new and one that is in transition. In every sector,it is now in the process of blending its tradition, customs and practices with Western concepts and ideas. In the business world, it is the blending of itswisdom and Western practices.Frank Gallo, the retired Greater China Managing Consultant of Watson Wyatt Worldwide, recently published an interesting book ``Business Leadership in China.''The 220-page book sheds light on the uniqueness of China's business leadership, the clash of old and new generation leaders and its transition to hybrid management leadership practices. Michael Barbalas, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in China, said, ``Frank GalloFrank Gallohas addressed one of the most pressing and complex issues for companies in China ― business leadership. By sharing his own experiences of consulting in China, he provides practical advise and examples of how Chinese business leaders think and act.He listed many cases that Western CEOs may encounter in doing business unless they fully study the delicacy of China's management practices.The following are some features of China's unique business leadership that foreigners should learn before doing business in the world's fastest-growingeconomy. The features come from the executive summary made in each chapter of the book.(1) It is naive to think that the best Western leadership practices can just be described and applied in China. China's cultural differences with the West make some practices very difficult to work with in China.(2) Westerners usually have their eyes on the ends while Chinese leaders focus more on the means.(3) One reason that China has special leadership needs is demographic. An entire generation of potential business leaders languished during the Cultural Revolution. Only a small percentage of that generation became businessleaders. The result was a relatively young work population compared to that in the West. Another reason for China's inability to quickly develop leaders is cultural. Many of today's senior managers in China got their positions through personal struggle. They see this as the best way to get ahead and are not keen on developing special programs to develop new leaders.(4) The Chinese sometimes see Western independence as ``showiness.'' Some Chinese have referred to the typical Westerner as a peacock ― flashy and beautiful to look at but without much strength or substance. Standing alone is an anathema to Chinese thinking.(5) Chinese culture is deeply founded in Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. They were all suppressed during the Cultural Revolution but none were eradicated.(6) Chinese leaders are expected to be nationalistic. While their bosses require allegiance to the firm, Chinese society also expects allegiance to the country.(7) Leaders in China are expected to express themselves much less directly than those in the West. Indirectness implies thoughtfulness and also allows room for renegotiation after the fact.(8) Face-saving has a deeper meaning in China than in the West. Many Chinese will go to great lengths either to save face or to save someone else's face.(9) Leaders in China need to find the right balance between truth and courtesy and encourage employees to use both in a harmonious way. (10) Both external experts and local business leaders define China as a low trust society. Chinese people are slow to trust their leaders.(11) The Western concept of empowerment has been introduced to China without properly recognizing the inherent conflict with Confucian hierarchy. Inorder to make empowerment successful in China, a leader needs to learn to integrate these disparate concepts.(12) Since China is historically both a family-run and a rural country, thetheme of collectivism is strong. Unlike Western culture, which breedsindividualists, Chinese culture breeds collectivists.(13) Western legal systems are based on the rule of law. The Chinese systemis primarily a rule of man.(14) The Chinese are often accused of not being risk-takers or innovators dueto the ``fear factor'' evident during the Cultural Revolution.(15) Westerners believe in the value of making quick decisions and thentaking action. Chinese want to be sure that all angles of an issue are reviewedfirst and all matters are thought through before coming to a conclusion. This process often involves going back to the beginning and starting the thinkingand the discussion again. These two different approaches are sources offrustration for both parties.(16) In China's short business history, using military discipline andpunishment for mistakes, thus instilling a fear of humiliation, has been a typical approach to keep people motivated. The rewarding style of Western management is a bit alien to the Chinese way of thinking in business.(17) Chinese teams are very strong. Team members are loyal to the team and committed to its success. There is a clear analogy with the Chinese family, the foundation of Chinese society.Available from:http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/nation/2010/01/257_31110.html。

changes in china作文Title: Changes in China: A Journey of Progress and Transformation China, a land of ancient civilization and profound traditions, has undergone remarkable changes in recent decades. Once a closed-off country, it has now emerged as a global powerhouse, reshaping its landscape and society.Technological advancements have been at the forefront of these changes. From high-speed railways crisscrossing the country to futuristic cities like Shenzhen, China has showcased its prowess in infrastructure and innovation. The rise of digital technologies, such as mobile payments and e-commerce, has transformed daily life, making it more convenient and connected.Moreover, China's economic growth has been nothing short of astonishing. It has become the world's second-largest economy, lifting millions out of poverty. This economic boom has been accompanied by significant improvements in education, healthcare, and living standards. Socially, China has also seen significant shifts. The younger generation is more open to new ideas and ways of life, embracing diversity and individuality. Cultural exchanges with the world have led to a richer and more vibrant cultural landscape.However, these changes have not been without challenges. Environmental degradation and social inequality remain pressing issues.Balancing economic growth with sustainability and inclusivity is a key challenge for the future.In conclusion, China's transformation is a story of progress, innovation, and resilience. It stands as a testament to the power of determined effort and vision. As it continues to evolve, China remains a fascinating and inspiring nation on the global stage.。

对国家治理体系的启示英文The Chinese governance system has been effective in managing the country's development over the past few decades. It has also provided valuable insights and inspiration for the developmentof governance systems globally. Here are some of the key lessons from China's governance system:。

1. Emphasis on development: The Chinese governance system focuses on development as the primary objective. The government works towards facilitating growth and providing basic necessities to its citizens.4. Technological innovation: China has invested heavily in technological innovation, which has driven its growth. The government has provided support to innovation by providing a favorable environment, including investments in research & development.5. Environmental sustainability: The Chinese governance system has recognized the importance of environmental sustainability and is working towards mitigating environmental challenges such as pollution.6. Public participation: The Chinese governance system encourages public participation in decision-making processes. The public is allowed to provide feedback, criticism, and suggestions to government policies and programs.8. Decentralization: The Chinese governance system has a decentralized structure where local governments have significant autonomy. This promotes innovation and allows for customized solutions for different regions.In conclusion, the Chinese governance system provides valuable insights and inspiration for global governance. Working towards development, leadership, and innovation while promoting public participation, sustainable development, and a focus on results are essential principles that can be adapted to suit different countries.。

我与北京大学的周黎安教授联袂编辑这部文集,并取了《为增长而竞争:中国经济增长的政治经济学》这样的书名,可谓煞费苦心。

我们编辑这个文集的目的是为了能够总结和体现这些年来中国经济学家对财政分权、地方竞争与经济增长的经验研究成果。

我们认为这将会是转型经济学文献中的重要内容。

1985年以来的财政分权体制演变至今,判定中国已是一个高度分权的国家,应该没有什么疑问的。

即使1994年的分税制使得中央的收入更加集中了,但依然没有改变由地方担当经济发展和组织投资活动的分块结构。

如果用地方政府支出的相对比重来衡量的话,中国可能算是当今世界上最分权的国家了。

1997年的世界发展报告《变革世界中的政府》提供的数据显示,在发达国家,省(州)级政府财政支出占各级政府支出总额的平均比重只有30%左右,最分权的加拿大和日本也只有60%[1]。

在1990年代,发展中国家的平均比重是14%,转型经济是26%,美国也不到50%。

从图3我们看到,中国的省级财政支出十几年来一直维持了占全国财政支出的将近70%[2]。

因此,高度的分权体制就成为观察改革后中国经济增长的一个重要的特征性现象。

中国不是一个政治上实行联邦制的国家。

但是从1950年代实行了中央集权计划经济模式之后不久,中央与地方之间围绕计划管理权力与财政收支管理的制度就一直处于政策和理论争论的焦点,导致中央与地方之间反复不断进行权力的划分、调整与妥协,也导致毛泽东在1956年发表著名的《论十大关系》。

这种现象并不典型,在中央集权计划经济模式下是不多见的。

苏联式的集权计划模式一直都是依赖中央的专业部对生产者进行垂直的计划控制,在财政上地方政府并没有自主的权力。

但中国的计划经济模式一开始就烙上了分权的烙印。

即使中央有多次重新集权尝试,地方政府的权力也始终没有受到削弱。

每一次的集权努力都是短暂的,不成功的,而且都是以过渡到更大程度的分权而收场的。

政治学家王绍光教授曾经说,毛泽东本人从骨子里不喜欢苏联的集权计划模式。

The medieval period, commonly referred to as the Middle Ages, spans approximately from the 5th to the late 15th century. This era represents a crucial transitional phase in European history, marked by distinctive cultural, social, and political developments. The medieval period is often divided into three subperiods: the Early Middle Ages, the High Middle Ages, and the Late Middle Ages.### Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th Century):#### **Historical Context:**The Early Middle Ages began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, a pivotal event that led to the fragmentation of political and social structures. Barbarian invasions, economic decline, and the disintegration of centralized authority characterized this tumultuous period.#### **Feudalism:**Feudalism emerged as a dominant social and economic system during this time. The feudal structure was based on a hierarchical relationship between lords, who owned land, and vassals, who pledged loyalty and military service in exchange for protection. This decentralized system provided a semblance of order in a time of political instability.#### **Role of the Church:**The Catholic Church played a significant role in shaping the social fabric of the Early Middle Ages. Monasteries and convents became centers of learning and culture, preserving classical knowledge and contributing to the spread of Christianity.### High Middle Ages (11th to 13th Century):#### **Economic Revival and Urbanization:**The High Middle Ages witnessed an economic revival, marked by increased agricultural productivity and the growth of trade and commerce. This prosperity contributed to the rise of towns and cities, leading to the development of a nascent urban culture.#### **The Crusades:**The Church's influence extended beyond Europe through the Crusades, a series of religious wars aimed at reclaiming the Holy Land from Muslim control. Although the Crusades had political and economic motivations, they also had profound cultural implications, facilitating the exchange of ideas and goods between the East and West.#### **Scholasticism and Intellectual Revival:**The High Middle Ages saw a resurgence of intellectual activity with the rise of scholasticism. Scholars like Thomas Aquinas sought to reconcile faith and reason, fostering an environment conducive to academic pursuits.#### **Gothic Architecture:**One of the most enduring legacies of the High Middle Ages is the development of Gothic architecture. Cathedrals such as Chartres and Notre-Dame de Paris showcase the innovative use of pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses, reflecting both technological and aesthetic advancements.### Late Middle Ages (14th to 15th Century):#### **Challenges and Crisis:**The Late Middle Ages brought a series of challenges, including the Black Death, a devastating pandemic that swept through Europe and caused significant demographic and economic disruptions. This period also witnessed political instability, social upheavals, and the Hundred Years' War between England and France.#### **Rise of Nation-States:**Amidst the turmoil, the Late Middle Ages saw the emergence of powerful nation-states. Monarchs began to consolidate power, centralize authority, and diminish the influence of feudal lords. This marked a shift toward more centralized forms of governance.#### **Cultural and Artistic Developments:**Despite the challenges, the Late Middle Ages fostered remarkable cultural and artistic achievements. The Renaissance, characterized by renewed interest in classical art and humanism, began to take root, paving the way for the cultural transformations of the following centuries.#### **Decline of Feudalism:**The Late Middle Ages also witnessed the gradual decline of feudalism. Economic changes, technological advancements, and shifts in political power contributed to the erosion of the feudal system, setting the stage for the societal transformations of the Renaissance and the early modern period.### Conclusion:The medieval period, with its distinct phases and multifaceted developments, laid the groundwork for the subsequent evolution of European civilization. From the fragmentation and decentralization of the Early Middle Ages to the economic prosperity and intellectual flourishing of the High Middle Ages, and finally, to the challenges and transformations of the Late Middle Ages, this era was characterized by a complex interplay of social, political, and cultural forces. The legacy of the medieval period endures in the institutions, art, and ideas that shaped the course of European history and influenced subsequent epochs.。

爱考机构-人大考研-法学院研究生导师简介-刘俊海刘俊海民商法博士教授,博士生导师中国人民大学商法研究所所长中国人民大学法律顾问。

兼任中国消费者协会副会长、中国法学会消费者权益保护法研究会副会长兼秘书长、中国国际经济贸易仲裁委员会仲裁员、北京仲裁委员会仲裁员、中华全国总工会法律顾问委员会委员、中宣部司法部与中国法学会“六五”普法国家中高级干部学法讲师团成员、国家法官学院兼职教授、商务部电子商务专家咨询委员会委员、深圳证券交易所博士后工作站博士后导师、深圳证券交易所第二届上诉复核委员会委员、中国法学会理事、中国法学会商法学研究会常务理事、中国法学会证券法研究会常务理事、中国工商行政管理学会常务理事、中国个体劳动者协会常务理事、中国注册会计师协会会计师事务所内部治理委员会副主任、海峡两岸法学交流促进会常务理事、北京市人民检察院民事行政专家咨询委员会委员、厦门仲裁委员会仲裁员、《中国资本市场法治评论》主编、《资本市场法治网》()主编、中国政法大学与河北大学等多所大学兼职教授等。

新闻'>1989年毕业于河北大学法律系,获法学学士学位。

1992年毕业于中国政法大学研究生院,获经济法硕士学位。

1995年毕业于中国社科院研究生院,获民商法博士学位。

1995年入中国社会科学院法学所从事商法经济法研究工作。

主要研究专长为公司法、证券法和其他商法经济法前沿问题。

作为核心咨询专家或起草工作小组成员,参加了《公司法》、《证券法》、《证券投资基金法》、《合伙企业法》、《政府采购法》、《企业国有资产法》《和《消费者权益保护法》等商事经济法律的研究、起草和修改工作。

多次参加立法机关组织的专家座谈会,并多次向立法机关提供咨询建议,多项立法建议被采纳。

独立承担或主持了国家社会科学基金项目《规范、健全、发展资本市场的法律问题研究》等多项课题研究项目。

1.中国消费者协会副会长;2.中国法学会消费者权益保护法研究会副会长兼秘书长;3.中宣部、司法部、中国法学会“六五”普法国家中高级干部学法讲师团成员;4.中国法学会理事;5.中国国际经济贸易仲裁委员会仲裁员;6.北京仲裁委员会仲裁员;7.吉隆坡区域仲裁中心仲裁员(KLRCA);8.维也纳国际仲裁中心仲裁员(VIAC);9.全国总工会法律顾问委员会委员;10.全国人大法工委专家库专家;11.商务部电子商务专家咨询委员会委员;12.海峡两岸法学交流促进会常务理事;13.中国法学会商法学研究会常务理事;14.中国法学会证券法研究会常务理事;15.中国工商行政管理学会常务理事;16.国家工商行政管理局培训中心兼职教授;17.中国个体劳动者协会常务理事;18.深圳证券交易所博士后工作站博士后导师;19.深圳证券交易所第三届上市委员会委员;20.深圳证券交易所第二届上诉复核委员会委员;21.中国社会科学院民营经济研究中心特邀研究员;22.中国法律咨询中心专家委员会委员;23.中国注册会计师协会会计师事务所内部治理委员会委员;24.《中国证券报》专家学术顾问;25.《法制日报》法学专家顾问团成员;26.《检察日报》学术指导委员会委员;27.《中央人民广播电台》经济宣传顾问;28.中央电视台《今日说法》点评嘉宾;29.第一届中国法学会商法学研究会副秘书长;30.国家法官学院兼职教授;31.中国政法大学兼职教授;32.河北大学兼职教授;33.华侨大学兼职教授;34.乌克兰《公司所有权与控制》(CorporateOwnershipandControl)杂志编委;35.《环球法律评论》编委(2002-2006)36.中国人民大学民商事法律科学研究中心研究员;37.中国人民大学法律顾问;38.教育部科研基金和科技奖励评审专家;39.中国市场学会信用学术委员会委员40.北京市人民检察院民事行政专家咨询委员会委员41.北京市消费者协会专家委员会委员;42.北京市评标专家1.2006年,被中国法学会评选为第五届“全国十大杰出青年法学家”;2.2008年,入选教育部新世纪优秀人才支持计划;3.2008年,被中央宣传部、中央政法委员会、司法部和中国法学会评为“百名法学家百场报告会”最佳宣讲奖;4.2008年,入选“2008中国杰出人文社会科学家”(2009年1月14日中国校友会网大学评价课题组《2008(第二届)中国杰出人文社会科学家研究报告》);5.2006年,刊登于《中国社会科学院要报:领导内参》2005年第27期的《妥善解决股权分置改革中涉及外资股东的难点法律问题》获中国社会科学院(省部级)优秀信息一等奖。

行政发包制与帝国逻辑周黎安《行政发包制》读后感周雪光【摘要】In this short commentary ,I discuss the theoretical significance of the“administrative subcontract” model developed by Professor Zhou Li‐An . I clarify some implicit assumptions in the proposed model and develop an alternative model to contrast modes of governance between centralization and decentralization .Finally ,I discuss the placeof“administrative subcontract”as a mode of governance in the larger context of Imperial China .%本文讨论周黎安“行政发包制”一文的研究风格和理论模型的前提假设,并提出进一步推进的意见和建议。

在周黎安模型基础上,笔者针对效率与统治风险的目标冲突,提出了执政者在集权与分权间抉择的一个模型。

最后,将“行政发包制”这一治理模式放在帝国逻辑的大历史背景上讨论其定位和意义。

【期刊名称】《社会》【年(卷),期】2014(000)006【总页数】13页(P39-51)【关键词】行政发包制;帝国逻辑【作者】周雪光【作者单位】斯坦福大学社会学系【正文语种】中文有关中国国家治理的诸多制度和机制,社会科学文献中多有讨论,近年来已成热点。

《社会》本期专辟这一主题的专栏,其中周黎安(2014)的《行政发包制》一文,立意清晰,逻辑严谨,文笔明快,讨论充分,可谓力作。

下面笔者就该文作者的研究风格、模型的改进及其在国家治理整体性视角下的位置谈谈感想,求教于作者和读者。

S e m i n a r o n t h e G o v e r n m e n t a n d P o l i t i c s o f C h i n a当代中国政府与政治研究2008年春,研究生31人Instructor: 宋迎法Email: p o l i p s y@s i n a.c o mW e b s i t e:h t t p://p o l i p s y.v i p.s i n a.c o m B B S:h t t p://c l u b.x i l u.c o m/s c u m tOffice: Room 2308, Office Building at Wenchang Campus Telephone: 83995021课程描述(Course Description)本课程综合运用政治学(political science)、行政学(public administration)基本理论分析当代中国政治组织与政府机构及其运转过程和特点,从中央和地方两个层面剖析中国政府与政治,从静态的制度设置和动态的现实运行双重视角观察中国政府与政治。

试图思考和回答“中国是如何治理的?”这一重大问题。

内容安排(Outline)第一讲绪论第二讲党中央第三讲全国人大第四讲国务院第五讲全国政协第六讲国家主席、中央军委、最高人民法院、最高人民检察院第七讲省级政府与政治(省、直辖市、自治区、特别行政区)第八讲地级政府与政治(地区、地级市、自治州)第九讲县级政府与政治(县、县级市、自治县)第十讲乡级政府与政治(乡、镇)考核要求(Requirement)最终成绩B:B= B1+ B2资料翻译B1(50分):在课程学习的前半段翻译To Serve and to Preserve: Improving Public Administration in a Competitive World一书,每位同学翻译一定篇幅的英文资料,在第六次课之前将译文的电子文档发至老师的邮箱。

经济发展论坛工作论文FED Working Papers SeriesNo. FE20050095Decentralization and Local Governance in China’s Economic TransitionJustin Yifu Lin Ran Tao Mingxing LiuDecentralization and Local Governance in China’s EconomicTransitionJustin Yifu Lin* Ran Tao** Mingxing Liu***AbstractThis chapter will focus on the decentralization and governance issues at local level, and strive to illustrate the structure and evolution of inter governmental arrangements at higher levels that constitute the institutional background in China. We argue that the centralization-decentralization cycle is endogenous to the traditional plan system, which featured heavy industrialization. Although decentralization in market-oriented reforms helped to promote economic growth by hardening local budget constraints and promoting local incentives to foster economic growth, it has led to lower central redistributive power and enlarging spatial inequality. Without clear and appropriate intergovernmental expenditures, responsibility division and equalizing transfer arrangements, the recentralization in 1994 has significantly impaired the local capacity to provide decent public goods and services in less developed regions and brought about serious local-governance issues in China.Keywords: Decentralization, Transition, Unfunded Mandate.* China Center for Economic Research, Peking University, e-mail: jlin@; ** Institute for Chinese Studies, the University of Oxford, Center for Chinese Agriculture Policy, China Academy of Sciences, e-mail: ran.tao@;*** School of Government, Peking University, e-mail: mxliu@.IntroductionIn any discussion of China’s decentralization and local governance, three aspects deserve special attention. First, China is a large country with five levels of government. Below the central government are 31 provincial level units (42 million population on average), 331 prefecture level units (3.7 million people on average), 2,109 counties (580,000 people on average), and 44,741 townships (27,000 people on average). Furthermore, there are about 730, 000 more or less self-governed villages in rural areas below the township level (World Bank, 2002). The multi level nature of Chinese bureaucracy frequently causes confusion when people talk about decentralization and local governance in China, since the level can range from provincial to village.Second, the fact that China is still a transitional economy in a process of marketization makes the existing literature on China’s decentralization somewhat different from the general decentralization literature. Since China used to be a planned economy and most of the economic activities were under center’s control in the plan period, the reforms initiated since the late 1970s can be viewed as a process of delegating more decision-making powers in investment approval, firm entry, revenue mobilization, and expenditure responsibilities to lower levels of government and granting more autonomy in production and marketing to state-owned enterprises. As a result, much of the literature on China’s decentralization actually dealt with China’s economic transition and liberalization (see Qian and Weingast, 1996, as an example), compared to the general literature of decentralization that focuses on the transfer of public functions to lower-level governments.Third, China is still a party state with all levels of government officialsappointed from above by the ruling Communist Party. Unlike many countries of Africa or Latin America that are often plagued by bureaucracies that lack experience or organizational capacity, the Chinese bureaucracy is an elaborate network that extendsto all levels of society, down to the neighborhood and working unit, and exhibits a high degree of discipline by international standards (Parish and White, 1978, 1984). Within each level, an impressive organizational apparatus is able to transmit state policies down to lower-level government agencies step-by-step through several layers of government bureaucracy (Oi, 1995). In the 1990s, grass root elections took place extensively at the village level, which is not formally a level of government. Therefore, the concepts of constitutional decentralization and political decentralization do not quite fit in the case of China since there are no institutionalized rights of local governments in the central decision-making procedures and no widely accepted genuine elections at and above the township level.This chapter focuses on a limited number of topics considered essential to an understanding of China’s decentralization and local governance by the authors. Considering the multi level nature of Chinese bureaucracy, we focus on the decentralization and governance issues at local level, and strive to illustrate the structure and evolution of inter governmental arrangements at higher levels that constitute the institutional background. Since China is still a transitional economy, the Chinese state is involved in some competitive sectors and intervenes in its citizens’ social and economic lives on many fronts. The decentralization process in China has been accompanied by institutional changes, such as the granting of more power in nonpublic functions (such as investment approval and entry of non state firms) to localgovernments. Given that the decentralization of nonpublic functions constitutes an important element in China’s economic transition and in many cases took place simultaneously with the decentralization of public functions, both dimensions are explored here. Furthermore, the centralized political system has shaped the administrative and fiscal decentralization process, and also constitutes the basis for understanding major local-governance issues in China, such as unfunded mandates, farmer’s tax burdens, and ineffectiveness in antipoverty programs.The chapter begins with a review of the centralization-decentralization cycles in the plan period before 1978 and the logic for such cycles. We discuss administrative and fiscal decentralization in China’s market-oriented reforms since the late 1970s; their impacts on economic growth, spatial inequality, and poverty reduction; the recentralization since 1994 and its affect on local public finance and public goods provision; and based on analyses of China’s intergovernmental fiscal and political arrangements, explore two major local governance issues in China, unfunded mandates and ineffectiveness in antipoverty efforts.The Centralization-Decentralization Cycle in the Plan PeriodThe founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 marked a new era in Chinese history. Government leaders believed that to defend the new socialist system and to keep pace and even overtake Western industrial countries, rapid industrial development, especially the establishment of a complete set of heavy industries, was essential. Learning mainly from the Soviet experiences, the Chinese government began toformulate and implement the first five-year plan which gave priority to heavy industrial development beginning in 1953.However, the development of capital-intensive industries would have been extremely costly if the free market had been allowed to operate in a capital-scarce economy. To mobilize resources for such a heavy industrialization, a plan system was established that was characterized by a trinity of a macro-policy environment of distorted prices for products and essential factors of production such as trained personnel, funds, technologies and resources, highly centralized planned resource allocation, and a micro-management mechanism in which firms and farmers had no decision-making power (Lin, Cai, and Li, 2003).i For instance, a commune system was set up in the rural areas in the late 1950s to guarantee a state monopoly on grain procurement. Besides supplying grain at depressed prices, the communes and production brigades were also responsible for mobilizing financial and human resources for local public goods provision by organizing farmers for compulsory labor.Under the plan system, a heavily centralized fiscal system was established. The accounting systems of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were incorporated directly into the government’s budget, and major resources were controlled by the center. The State Planning Commission determined local revenue and expenditure plans on an annual basis, known as unified revenue and unified expenditure (tongshou tongzhi). Local governments (at the province, prefecture, county, and commune levels) did not have independent budgets.ii As to expenditure assignment, the central government was responsible for national defense, economic development (capital spending, R&D, universities, and research institutes), industrial policy, and administration of nationalinstitutions such as the judicial system. Responsibility for delivering day-to-day public administration and social services, such as education (except universities), public safety, health care, social security, housing, and other local and urban services, was delegated to local governments.However, in a country of the size of China, formulating, administrating, coordinating, and monitoring the central plans were time-consuming and became more and more so as the economic system became larger and more complicated. For example, the number of state-owned enterprises(SOEs) subordinated to the central government increased from 2,800 in 1953 to 9,300 in 1957, and the number of items in material allocation under central planning increased from 55 in 1952 to 231 in 1957(Qian and Weingast, 1996). The classical problem of control and monitoring under information asymmetry emerged soon after the planned system was set up. As the economy grew larger with more projects initiated and enterprises started, the plan system became increasingly unmanageable. To make things worse, a highly centralized planned system inevitably undermined the incentives of local governments when local coordination in industrial development was essential.Under this background, China initiated its first decentralization within the planned framework by delegating more powers to local governments in 1957. The policies then included (1) delegating nearly all SOEs to local governments, such that the share of industrial output by the enterprises subordinated to the central government shrank from 40 percent to 14 percent of the national total; (2) changing central planning from a national to a provincial basis, with decisions about fixed investment to be made by local governments rather than the central government; and (3) fixing the revenuesharing schemes for five years, and granting local governments some authority over taxes. The share of central revenue decreased from 75 percent to around 50 percent within two years.Indeed, local incentives responded quickly to decentralization. Local small industries boomed in this period. This program, however, did not succeed because of serious coordination failures caused by the radical decentralization. The soft-budget constraint faced by local governments and SOEs soon led to excessive investment expansion and inefficient interregional duplication of production. Recentralization began in 1959, when all large and medium-sized industrial enterprises were again subordinated to the center. However, centralization again brought about the incentive problem and economic stagnation in the 1960s. Thus a second wave of decentralization followed in the late 1960s, when local governments gained more authority over fixed investment and local revenue. Afterwards, a similar but less serious investment boom led to yet another round of recentralization in the mid-1970s.In retrospect, it is easy to see that decentralization under a plan system was not able to alleviate the inefficiency problem since it could neither improve micro efficiency through market discipline nor change the heavy-industry development strategy inconsistent with China’s comparative advantage. Under the soft-budget constraints faced by local government and SOEs, a cycle of decentralization leading to disorder, disorder leading to centralization, centralization leading to stagnation, and stagnation leading to decentralization was inevitable.Decentralization under Market-Oriented Reforms, 1978 to 1993Low efficiency in the plan system was considered to be a serious problem as early as the 1950s before the first round of decentralization was initiated(Mao, 1956), but not until 1978 were some fundamental reforms undertaken. What was evident to policy makers in the late 1970s was the correlation between production inefficiency of enterprises and communes and lack of stimulus for workers and farmers. That explains why the reforms began with the micro management system in the late 1970s in an attempt to improve work incentives. In rural areas, the household responsibility system (HRS) emerged in 1978. In just a few years, the system became a dominant form of microeconomic organizations in rural areas. In cities, reforms in SOEs were initiated in the early 1980s, centering on power delegation and profit sharing. Such reforms rendered rural households and SOEs de facto residual claimers of their production and thus greatly promoted work incentives.Administrative and Fiscal DecentralizationAccompanying the micro reforms in rural areas and SOEs was a process of administrative and fiscal decentralization, which was deemed necessary in a large country like China to induce local coordination in market-oriented reforms.Administrative Decentralization From the administrative perspective, the reform period witnessed a significant strengthening of local governments’ role in local economic management, such as investment approval, entry regulation, and resource allocation. A particularly striking example is the opening-up policy initiated in thecoastal regions. Starting from 1979, many provinces were allowed to set up their own foreign-trade corporations. From then on, regional experimentation with opening-up began, which includes the “one-step-ahead” policies implemented in Guangdong and Fujian in 1978, the establishment of four special economic zones (Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Shantou, and Xiamen) in 1980, and the declaration of fourteen coastal cities as "coastal open cities” in 1984. Not only did these areas enjoy lower tax rates and a higher share of revenues, but perhaps more important, they enjoyed special institutional and policy environments and gained more authority over local economic development and the establishment of special economic zones and economic-development zones.Another dimension of administrative decentralization was the delegation of more state-owned enterprises to local governments at the provincial, municipality, and county levels beginning in the early 1980s. By 1985, the state-owned industrial enterprises controlled by the center accounted for only 20 percent of the total industrial output at or above the township level, while provincial and municipality governments controlled 45 percent and county governments 35 percent (Qian and Xu, 1993). With an ownership shift from central to local, local governments were provided with incentives in taxes and profits to step up their effort in revenue collection. At the same time, the spending of the fixed investment for local-government-owned-enterprises fell naturally on the shoulders of local government. Since SOEs had provided a wide range of social services to their employees, more local ownership implied that local governments would take primary and final responsibilities for these expenditures.Fiscal Decentralization The fiscal dimension of decentralization was no less dramatic. In 1980, the inter governmental fiscal system shifted away from unified revenue and unified expenditures and toward a "cooking in separate kitchens” (fenzhao chifan) that divided revenue and expenditure responsibilities between the central and the provincial governments.iii After that, the central-provincial fiscal arrangement experienced further changes, such as the proportional-sharing system in 1982 and the fiscal-contracting system in 1988. In the 1988 fiscal-contracting system, the center negotiated different contracts with each province on revenue remittances to the center and permitted most provincial governments to retain the bulk of new revenues. There were six basic types of sharing schemes in 1988, and they continued through 1993 (Bahl and Wallich, 1992). Besides fixed subsidies from the center (in fourteen provinces), fixed-quota deliveries to the center (in three provinces), fixed sharing with the center(in three provinces), and quota deliveries with a pre specified growth(in two provinces), other provinces adopted either an incremental sharing(a certain share is retained locally up to a quota, and then a higher share is retained in excess of the quota in three provinces), or a sharing up to a limit with growth adjustment (ten provinces retained a share within a specific percentage of revenue from the previous year and then retained all revenues above that quota).At the lower level, the provinces had substantial flexibility in setting the rules for subordinate levels. Each province specifies the sharing system with its prefectures, the prefecture for its counties, and so on. Expenditure assignments were structured in a similar way: the central government sets the division of expenditure responsibilitiesbetween the center and the provinces, and the intermediate layers decide how they share responsibilities with subordinate levels.Decentralization and Economic Performance, 1978 to 1993In general, with the decentralization of 1978 to 1993, political powers were still heavily centralized, but local governments began to enjoy more autonomy in local economic management, to control a larger share of fiscal resources, and at the same time to assume primary responsibilities for local public-goods provision. This implies a very decentralized fiscal-expenditure arrangement in which local government assumed greater responsibility for providing education, health, housing, social security, local infrastructure, and so forth. In the context of marketization reforms (deregulation), the decentralization in this period was associated with significant economic growth as well as mixed performances in spatial inequality and poverty reduction.Economic Growth and TVE Development Decentralization in this period played an important role in promoting national as well as local economic growth. From 1978 to 1993, China's per capita gross national product (GNP) increased in real terms by around 280 percent. National absolute poverty was reduced by more than 50 percent in the first half of the 1980s, dropping from 17.9 percent of the population in 1982 to 6.1 percent in 1984 (World Bank, 2001). This downward trend corresponds to the growth of real income and real GNP. China also witnessed an across-the-board growth in both coastal and inland regions. Indeed, if each China’s province were taken as an economy, abouttwenty out of the top thirty growth regions in the world in the period would be provinces in China.Much of the economic growth in the period could be attributed to a spectacular entry and expansion of non state enterprises, especially the township and village enterprises (TVEs), which actually have been one of the most distinctive features in China’s economic development and transition (Qian and Xu, 1993). Nationally, the output of TVEs grew more than six fold in real terms between 1985 and 1997, leading China’s rapid industrial and overall growth. By 1993, TVEs already accounted for 36 percent of the national industrial output, up from 9 percent in 1978. Within the rural sector, the TVEs accounted for three-quarters of rural industrial output (Che and Qian, 1998).The rise of TVEs was closely related to administrative and fiscal decentralization from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s. Local governments actively supported market-oriented, non state enterprises to expand their revenue base under competition between jurisdictions for getting rich first. With the decollectivization of agricultural production, local governments had to seek further revenue sources, and the fiscal reform that gave higher shares of revenue (TVE tax or profits) to local governments and granted them the rights to use the fiscal surplus paved the way for local governments to support the TVE developments under a better incentive system. The decentralization policies granted local officials large autonomy over their economies, including the autonomy to set prices, to make investment with self-raised funds, and to restructure their firms, and to issue licenses to newly established firms.iv By delimiting better the property rights between governments at different levels,decentralization rendered governments at each level the residual claimant and controller of its own public enterprises.vIn the transitional process, local governments at the county, township, and village levels played unique roles in fostering local economic development, especially in supporting the TVEs. In the early to mid-1980s, when the TVEs started their golden period of growth, private entrepreneurs were still uncertain about the directions of central policy regarding private enterprises. Local governments assumed the entrepreneurial role and started rural industrial development.According to empirical investigations carried out by Byrd and Gelb (1990) and Oi (1995), although most TVEs enjoyed a considerable degree of enterprise autonomy, the community government made strategic decisions in investment and finance, manager selection, and the use of after-tax profits for public expenditure. The community governments usually initiated internal fund raising, either from collective accumulation or from individual contributions to start up the community-owned enterprises. The community governments were also pivotal in securing loans from either the Agricultural Bank of China (ABC) or rural credit cooperatives (RCCs), two major external sources of financing, using the community assets as collateral and providing loan guarantee for TVEs. Using information and contacts that they developed beyond the locality through a government network, local officials could usually provide many essential services to local enterprises, such as raw materials and information about new products, technology, and markets for TVE products. vi Local officials also often tried their best to circumvent government regulations to allow TVEs to receive the maximum tax advantages and exemptions so that more revenues could be keptwithin the locality to further the competitive advantages of TVEs, and they provided local governments with more funding for local public goods and service provision.Fiscal Decline and Impacts on Spatial Inequality and Poverty Reduction Though decentralization was correlated to high economic growth in the 1980s, it also led to significant fiscal decline of the state. The total budget revenues fell from 35 percent of GDP in 1978 to below 12 percent in the mid-1990s. This was because the old revenue mechanism became unsustainable as central planning was dismantled. Profitability in industry fell as prices adjusted to market forces, sharply cutting the government revenue intake through state-owned enterprises. The emergence of non state enterprises competing for profits also contributed to revenue decline. Since the enterprise reforms required profit-sharing schemes to provide incentives, it reduced revenue flows to the budget, while creating extra budgetary funds that were managed independently by enterprises.The decentralization also led to fiscal decline of the center. In most instances, the revenue-sharing contracts between the center and provinces were regressive, since they allowed richer localities to keep a larger portion of collected revenue. The contracting system tended to favor richer localities with more local enterprises since local firms were the richest sources of extra budgetary or off-budgetary revenue. Taking extra budgetary revenue into account, poor regions with few local enterprises had to share an even larger proportion of total collected revenue with the center. As similar contracts were made between the provinces and sub provincial units, the bias against poor localities extended to the grass roots levels (World Bank, 2002). As aresult, local shares of budget revenue rose steadily from 54 percent of the total government revenue in 1978 to 61 percent in 1988 and rose further to 78 percent in 1993.With fiscal declines of the state as a whole and the central government, the center’s redistributive power was seriously damaged. Fiscal stress and declining central revenues had already led to dwindling inter governmental transfers and a de facto devolution of responsibilities to local governments. With the introduction of fiscal contracts in 1988, the central government formally ended its responsibility for financing local expenditures. The role of local governments was thereby shifted from providing services to financing them, a decentralization of responsibilities.vii While these levels of government had always provided such services, they had previously provided them as agents of the central government, that is, the center always subsidized the financial gap when necessary. By the end of the 1980s, fiscal decentralization, which tied budgetary expenditures more closely to local revenues, had created a budgetary crisis in nearly all poor counties that they experienced difficulties even in paying basic salaries (Park, Rozelle, Wong, and Ren, 1996). In these regions, high nondiscretionary outlays for personnel on the government payroll, including local officials, teachers, health workers, and other social-services personnel generally account for well over half of local budgetary revenues. Educational spending, most of which goes for teachers' salaries, often accounts for 40 to 50 percent of local budgetary revenues in poor counties. Poor-county governments had to employ a range of creative mechanisms to cope with their persistent and accumulating fiscal deficits. These mechanisms include deferring wages, borrowing from the budgets of various local-government bureaus, and borrowing against the next year's budgeted fiscal transfers from higher levels of government (Park et al., 1996). Local governments in less developed regions had to cut spending on social development and let individuals share more health-care and education expenses (West and Wong, 1995).Partly because of the limited redistributive power of the state, especially that of the center, China witnessed an increasing spatial inequality and stagnation in poverty reduction. Spatial inequality began to rise after an initial decline of urban-rural as well as inter provincial inequality from 1978 to the mid-1980s (Chen and Wang, 2001; Kanbur and Zhang, 1999). Such initial decline can be accounted for largely by increased agricultural prices as well as by rapid rural growth in this period. However, when China further decentralized, opened up, and experienced an explosion of trade and foreign direct investment in the mid-1980s, spatial inequality began to rise steadily. The Gini index of provincial per capita income declined from 29.3 percent in 1978 to 25.6 percent in 1984, but then rose to 32.2 percent in 1993 (Kanbur and Zhang, 1999). At the same time, the urban-rural average income ratio declined from 2.87 in 1978 to 1.86 in 1985, then increased to 2.5 by 1993 (SSB, 2004). After the mid-1980s, the poverty rates even increased—reaching 14.7 percent in 1989—and then stagnated, hovering around 10 percent in the early 1990s. This was despite continuous growth in national income and GNP, indicating that in these years the poor did not share the benefits of overall economic growth.Recentralization since 1994。