CHINESE CHRISTIANITY AND CHINA MISSIONS WORKS PUBLISHED SINCE 1970

- 格式:doc

- 大小:97.00 KB

- 文档页数:14

理雅各对中国文化的尊重与包容——从“译名之争”到中国经典翻译2012年第1期总第101期民俗研究FolkloreStudiesNo.1,2012SerialNo.101理雅各对中国文化的尊重与包容从"译名之争''到中国经典翻译王东波[摘要]理雅各以译介中国经典而成为19世纪欧洲着名的汉学家.理雅各翻译中国经典由"译名之争"肇始."译名之争"的核心问题是如何将God译为汉语.作为论争一方的主要人物,理雅各的观点也经历过由最初的译"神"到最后的译"帝"的重大转折.这其中理雅各深入中国经典,以大量的例证论证了将God译为"上帝"与《圣经》的并行不悖性,这也体现出他对中国文化的尊重与包容.[关键词]理雅各;"译名之争";中国文化;尊重与包容17世纪中期至18世纪中期发生的持续百年的"中国礼仪之争"是中西文化交流史上的重大事件,这其中的一大论题即"God"一词的"译名之争",引发了众多中西学者的积极参与,甚至牵动了中国朝廷和梵蒂冈教廷的中枢神经.英国伦敦会传教士理雅各(JamesLegge)在此论争中扮演了非常重要的角色.作为论争的一方,理雅各引据中国经典,力主从中国传统文化的角度处理译名的问题,反映了他在中西两种不同文化之间求同存异的努力.在之后的"四书","五经"为核心的儒家经典的翻译过程中,理雅各以客观,冷静,严肃,科学的方法来探寻中国经典的内涵,通过详尽的注释,力求真实表达中国经典的原义,使欧美人士得以准确了解东方文明和中国文化,充分体现了他对中国传统文化的尊重与包容.一,"中国礼仪之争''与"译名之争''"中国礼仪之争"(ChineseRitesControversy)是指17世纪中叶到18世纪中叶于在华传教士内部及传教士与罗马教廷之间展开的有关中国传统祭祀礼仪性质的讨论.这场以"译名之争"和"礼仪问题"为主要组成部分的争论实质上是中西文化和思想的一次交流和碰撞. "中国礼仪之争"的导火索是对《圣经》中God一词如何中译问题的争论以及从对于"尊孔祭祖"的态度开始的.最初入华传教的耶稣会教士利玛窦对此采取了灵活宽容的态度,他认为尊孔和祭祖具有"敬其为人师范","尽人子孝思之诚"的道德意义,只要不掺人祈求,崇拜等迷信成分就[作者简介]王东波,山东大学外国语学院教授(济南250100).[基金项目]本文系山东省社会科学规划重点研究项目"《论语》英译研究"(批准号:10BWXJ09)的阶段性成果.理雅各对中国文化的尊重与包容——从"译名之争"到中国经典翻译45只具有世俗性意义,而不是宗教崇拜行为,因而中国天主教徒可以参与尊孔祭祖的祭祀活动,这不违背基督教教义,并不是对自己的宗教不忠.另外,利玛窦援引中国古典文献,决定以"上帝"一词称呼天主教中的"God".利玛窦的观点得到了大多数人华耶稣会士的认可和奉行.但是,在当时的传教士中,并不是都如利玛窦那样对中国文化习俗给予应有的尊重,他们带着欧洲文化至上的思想,对利玛窦尊重中国传统文化的传教思想不以为然.在利玛窦死后,两派的分歧逐渐公开化,"中国礼仪之争"也愈演愈烈.而"译名之争"(TheTermQuestion)作为"中国礼仪之争"的重要组成部分,充分反映了这场长达百年的礼仪争论的全过程.西方传教士从明末清初时期就着手将《圣经》译为中文,天主教传教士翻译的《圣经》中译本只残留了其中的一部分,并未留下完整版本.而新教传教士的译经活动则始于19世纪初.1807年9月8日,英国伦敦会传教士马礼逊(RobertMorrison)来到中国,成为第一个来华新教传教士.1813年马礼逊完成了《新约全书》的中译工作,并在另一位传教士米怜(williamMilne)的协助下完成了《旧约》的翻译,1823年在马六甲出版,名为《神天圣书》.而在此前的一年,在印度赛兰坡(Se—rampore)的浸信会传教士马殊曼(JoshuaMarshman)和其助手拉撒(JohnLassar)也通力完成并出版了另一个《圣经》中文译本.马殊曼主要参考天主教传教士巴塞(JeanBasset)的译本,用"神"作为God一词的唯一译名.虽然马礼逊译本也主要参考巴塞译本,但其中并没有固定一词翻译God,而用"真神","神主","神天","主","上天"等来代指.马礼逊认为,翻译此词的最佳的方法是让这个字(神)继续被采用,直到传教士可以找到另一个基督徒广泛接受的固定用法为止.但这一译名不统一的问题遭到众多传教士的诟病.1835年马礼逊之子马儒翰(JohnRobertMorrison)与伦敦会传教士麦都思(WalterMedhurst)向英国与海外圣经会递交修订计划,要完成一部更符合中国语言习惯的《圣经》译本.此后,由麦都思,马儒翰,德国传教士郭实腊(CharlesGutzlaff)和美国公理会传教士裨治文(E.C.Bridgman)四人组成修订小组,翻译完成了新的《新约》,《旧约》,都是用"上帝"作为God的译名.修订译本仍然在译文与中文语言习惯的结合方面不尽如人意,因此1843年,麦都思重新召集来华新教传教士讨论重译《圣经》一事,其目标是完成一部符合汉语语言传统并具有权威性的通行译本.1847年6月28日,麦都思,文惠廉(WilliamBoone),娄理华(WalterLowrie),施敦力(JohnStronach),裨治文五人在上海举行翻译会议并正式开始修订工作.但随后,英美两国的传教士围绕着God一词如何中译发生分歧,各方就此问题进行了更为广泛的讨论.在此之前,英美两国的传教士就"译名之争"已经展开了辩论.包括麦都思,裨治文,文惠廉等在内的部分传教士在1845年出版的英文《中国丛报》(ChineseRepository)上就此问题针锋相对,各自撰文发表自己的意见.麦都思提出应该使用"上帝"作为God的唯一译名,并得到了伦敦会传教士的支持.而以裨治文为首的美国传教士则坚持使用"神"一词进行翻译.而在1847年的翻译会议上,这一无法回避的问题激发了两方的激烈探讨.在讨论,投票表决以及英美圣经公会决议等措施都无果的情况下,为了避免分歧,文惠廉作出决议:"由于在译名问题上无法取得一致意见,将留下空白的译本分寄欧洲和美国的圣经会,由将涉及此译本的各方对其采取的,他们认为对福音在中国的传播最有益处的行动(即印行时在空白处填上神或上帝)负完全的责任."①此次翻译会议所带来的"译名之争"的高潮过去后,争议逐渐趋于缓和,但译名的问题仍然困扰着在华传教±.1877年第一届全体在华新教传教士大会前夕,白汉理(H.Blodget)发文建议大会避开译名问题,将注意力集中于其他议题上.而他的观点随后遭到了包尔腾(J.S.Burdon)的①s.s.Williams,"V ersionoftheOldandNewTestamentsinChinese",ChineseRepository.V o1.19.P.54646民俗研究?2012年第1期反对,他认为应当公开讨论这一问题,而不应该回避,以促进传教士在译名问题上彼此宽容.①随后传教士们决定在大会上对God的翻译问题作出决议,由意见双方互相协商解决.但最终大会仍然没有取得任何成果.直至1890年在华新教传教士大会时,《教务杂志》提出传教士大会应该注意着力解决的问题第一条即是关于God译名统一的问题.大会进行中对译名问题进行了激烈的争论,但最终决议同意各圣经公会可以根据自己的需要做出选择,出版不同的版本,传教士有选用的自由.此后,曾经讨论激烈的"译名之争"逐渐平息.二,"译名之争"中的理雅各理雅各是英国伦敦传教会传教士,它自小对于文学就有着浓厚的兴趣,而在大学期间,他又致力于学习哲学和宗教.1841年,理雅各出任英华书院院长.随后,英华书院迁至香港,理雅各仍担任院长一职.此时期,伦敦会理事会决定筹募庞大的基金,展开对华传教活动,理雅各作为英国伦敦会的传教士,于1843年开始来华传教.就在此时期,理雅各对于中国传统文化有了初步的认识和了解.作为一个非国教的新教教徒,理雅各强调教会独立和信仰自由的观念,因而在"译名之争"中强调从中国传统文化中寻求解释与突破,这也反映出他在中西两种截然不同的文化产生碰撞时求同存异的努力.对于如何翻译God一词,理雅各的观点也经历过巨大的转折.1843年理雅各参加了麦都思召集的会议,讨论联合重译《圣经》,并与麦都思共同负责研究God一词的翻译问题.二人就此问题产生了分歧,麦都思认为God应译为"上帝",而理雅各则倾向于译为"神",但他表明此意见实受乃师修德影响,而非其研究所得.②而后,理雅各对于此问题又进行了深入思考与研究,并阅读中国传统典籍《诗经》,《尚书》等,以探寻证据.经深思熟虑后,理雅各改变其最初的观点,转用"上帝"作为God的译名.在《关于将"God"汉译为"上帝"的论辩》(AnArgumentforShang —Teasthe ProperRenderingfortheWordsElohimandTheosinChineseLanguage,1850)一文中,理雅各从语言学角度出发阐释了此种译法的合理性.他认为,God是相对之词(Relativeterm)而非"属类名称".属类名称的名词不能在没有定冠词之类的限定词的情况下以单数形式出现,而英语中没有"theGod"的说法,因此证明God是相对于其创造物而言的专有名词.而后,理雅各引用牛顿的观点证实God一词确为相对之词,它并不仅仅指代其自身,还与其他存在之物相关.③经过对中国传统典籍的研究,理雅各将"上帝"或更为简单的"帝"认定为一种相对之词,认为可以通过这种翻译以教导《启示录》的真理,并通过上帝优雅而慈悲的赐予拯救我自己以及教徒.④更为重要的是,理雅各通过与文惠廉的论辩,证明了将"God"译为"上帝"的正确性.在"译名之争"中,美国圣公会主教文惠廉主张以"神"为God译名,与理雅各所执之见针锋相对,两人就此展开了激烈的讨论.文惠廉依据朱熹理气说认为中国人所言之创造起源是出于太极,理和气,而并非一人创世,因此认为"上帝"译名不妥.理雅各对于文惠廉之主张并不认同,并引用中国经典进行反驳.文惠廉依据《易?说卦》"帝出乎震"一句而认为所谓"帝"指代伏羲,并不是上帝.理雅各则根据孔安国之说"帝者,生物之主,①J.S.Burdon,"C0rrespondence",ChineseRecorder6(1875):PP.149一l50.②JamesLegge,"AnArgumentforShangTe",Piii,转引自龚道运:《近世基督教和儒教的接触》,上海人民出版社,2009年,第147页.③JamesLegge,TheNotionsoftheChineseConcervtingGodandSpirits.Hongkong:"Hongko ngRegister"Office,1852,P.86.④同上,P.113.理雅各对中国文化的尊重与包容——从"译名之争"到中国经典翻译47兴益之宗"以证实中国传统典籍中所言之上帝即为创世主.另一方面,使用中国传统文化中旧有的最高存在的概念可以促进中国人对于基督教的理解,通过这一方式告诉中国人,"只要皈依基督教,他们就回归到了祖先圣王的宗教概念中;要让他们相信基督教并非与他们的文化遗产,传统宗教截然不同;中国人相信了这种说法后,传教士就能通过《圣经》的教义把特别的信息传给他们"①.文惠廉认为"上帝"一译带有中国传统的多神崇拜之嫌,既有对道教,佛教,儒家等神系的崇拜,也包括祭祖和对于自然神的崇拜,而英文中的God为"属类术语"(genericterm).如前所述,理雅各首先从语言学角度驳斥了文惠廉关于God一词语言定位的观点,认为God 并非"属类术语",而是相对之词.而针对文惠廉对于中国古代多神崇拜一论,理雅各则通过对于先秦经典的研究发现中国古人实际上信奉一神论,即只尊崇至高无上的"上帝".在《诗经?大明》中有言:"殷商之旋,其会如林,矢于牧野,维子侯兴,上帝临汝,无二尔心."还有:"上帝临汝,日鉴在兹."此外,根据《易经体注》有如下论据:"天之生成万物而主宰之者谓之帝.其出其入,无不玉玉卦位间.彼位起于震,其即帝之出.""帝之神运无方,物之化成有序,故以物之出入明帝之出入.即物之成终,而知帝之宰其终,即物之成始,而知帝之肇其始矣."由此,理雅各得出结论:中国古代所言之上帝与《圣经》中的God相同,既是造物主,同时也是主宰,管理万物之神,二者完全吻合.而文惠廉的中国古人多神崇拜之言并非古已有之,而是随着历史发展及民间宗教与佛教东传而产生的.理雅各更进一步借用明王朝祭祀文献说明"上帝"这一至高无上神与其他诸神之间的从属关系.根据《大明会典》记载,明世宗于嘉靖十七年(1538)改变上帝称号.在进行改号盛典之前,世宗"谨文移告于大明之神,夜明之神,五星列宿周天星辰之神,云雨风雷之神,周天列职之神,五岳五山之神,五镇五山之神,基运翔圣神烈天寿纯德五山之神,四海之神,四渎之神,际地列职祗灵,天下诸神,天下诸祗,戊戌太岁之身,十月神将直日功曹之神,郊坛司土之神."在祭祀文献中还提及:"于来月朔旦,上尊'皇天上帝'泰号."②理雅各由此篇祭文证明其他所有神灵皆从属于至高无上的上帝,进而说明中国古人对于上帝之崇拜实与基督教吻合.他依此得出结论,人类心目中只有一位上帝,虽然目前各个种族对其称谓不同,但只是出于语言差异,人类信仰的上帝仍是同一的.通过中国古典文献的支持,理雅各充分证实了自己的观点,并且驳斥了文惠廉所提倡之以"神"为译名的观点.同时,这场辩论也促使理雅各开始进行深入的汉学学习研究,在对于中国传统文化和儒家经典研究的过程中,也逐渐受到了中国古代博大精深的文化传统的感召,为儒家典籍中所体现的中国古代经验和智慧所折服.于是,理雅各对于"有凭可查的历史可以追溯到什么时候","中国人起源何处","释道儒的真实面目是什么","华人崇拜什么","其伦理体系究竟是什么"等等一系列问题③追根探源.在日记中,理雅各写道:"我不是作为一个哲学家看中国,而是以哲学的眼光看中国.中国对我来说是伟大的故事,我渴望了解其语言,历史,文学,伦理和社会形态."理雅各于1852年发表论文《中国人的上帝观和神观》(TheNotionsoftheChineseConcerningGodandSpirits).理雅各在文中以中国古代儒家经典的《书经》与《诗经》为支持,又一次论证中国古人所言之"上帝"与God在实质上是对等的.通过对于儒家经典的深入研究,理雅各对东西方思想,历史,文化,哲学有了一定程度的理解,在"译名之争"的辩论中起到了更加重要的作用.而对于中国传统典籍的阅读研究也使他有别于其他传教士.从中国古典典籍中寻找观念,证据以表明汉语中的"上帝"与基督教教义中对于God的崇拜有着不谋而合之处,这也体现了理雅各本人对于①LaurenPfister,"TheLegacyofJamesLegge",InternationalBulletinofMissionaryResearch, vo1.22,No.2(April1998)P.80.②转引自龚道运:《近世基督教和儒教的接触》,上海人民出版社,2009年,第150页.③转引自岳峰,《架设东西方的桥梁》,福建人民出版社,2004年,第152页.48民俗研究?2012年第1期中国传统思想文化的尊重以及中西融合之观点.理雅各这种对于中国古典文化的尊敬心态,也使理雅各在传统典籍的翻译过程中能够更加贴近中国传统语境,而不再如其他传教士一样,带着西方优越论的眼光看待中国传统文化与儒家经典.三,"译名之争"后的中国经典翻译所体现的理雅各的思想在"译名之争"中,理雅各引据中国经典,力主将God译为"上帝",以使《圣经》与中国传统文化达成衔接,竭尽全力保持中国传统文化的特色,促使中西文化的融合,正如他在告诫西方传教士时所说的那样,要避免"驾着马车在孔夫子的墓地上横冲直撞"①."译名之争"之后,理雅各致力于中国经典的翻译,目的是使西方读者,思想家和政治家了解中国人民的道德规范和行为准则,理解中国传统思想,认识中国社会.正如英国人湛约翰在给理雅各的信中所写:"我越来越相信你做的事情对我们的传教工作的重要性.我们要把《中国经典》用到基督教的传教事业上.我们中的大多数人还是很不了解中国文化,我要在传教条例上加上一条:要到中国传教就要对中国古代诗人,哲学家的语言有所了解."在《中国经典》一,二卷再版前言中,理雅各明确指出,在读解诠释中国经典时,他一直将宋代理学家朱熹的观点奉为自己的榜样.在他看来,朱熹不仅是一个古代经典思想的伟大传承者,也是一个伟大的批评家,哲学家.以此为基础,理雅各还广泛参考其他注家的观点.对于此,曾经协助他进行翻译工作的王韬在《送西儒理雅各回国序55中说道,"先生独不惮其难,注全力于十三经,贯穿考覆,讨流溯源,别具见解,不随凡俗.其言经也,不主一家,不专一说,博采旁涉,务亟器通,大抵取材于孔郑而折中于程朱,于汉宋之学,两无偏袒."④这一点在《论语》译本的注释中,我们可以找到大量的例证.理雅各翻译的《论语》,许多章节离开注释有时是相当费解的,涉及到修辞用法,文化词语时,这种现象尤为突出.因此,他的译文在很大程度上借助了大量详尽的脚注,有时脚注的篇幅甚至超过了译文,从而确保原语文化精髓的准确的传递,以免引起歧义.在篇章主题上,理雅各给出各章主旨,用简明的语言概括各章的内容,便于读者从整体上理解把握各章的内涵.这一点在每一章脚注的开头大写体部分都可以看得出来.他还将经文中的关键词语,语法现象均加以解释说明.理雅各对词义的研究详细认真,他很清楚,中英两种语言的词汇都存在着一词多义的现象,对词义把握不准,将导致对经义的误解.另外,他根据汉字四声的特点,常注明汉字的发音,并与英语中的多个对应词比较,根据上下文选取对等词汇.他有时甚至引经据典,从词源学的角度探求,以准确地把握词义.《学而》第一章中的"学"与"习"即是一例.在其译本则脚注中,理雅各是这样解释"学"的:学,先前的评论者将其释为"诵",即"以唱歌的语调朗读","讨论".朱熹以"效"释之,即"模仿",认为"学"的结果是"明善而复初",即"明了善美,恢复原善".而对于"习",其阐释是:飞行中的鸟儿翅膀快速频繁的扇动,用于表示"重复","练习".④为了帮助外国读者更好地理解《论语》,理雅各还对《论语》中相关的背景知识进行了介绍.《论语》记录了2500多年以前孔子及其弟子就当时中国社会各种问题所发表的论述.由于时代的变迁以及中外在政治体制,历史沿革,习俗传统,思维方式和价值取向等各方面存在着差异,为外国读者理解《论语》造成了巨大的障碍.理雅各的脚注则尽可能多地为读者提供这些历史文化背景知识,以便他们结合译文理解《论语》各章的内容,把握其内涵.如《雍也》中"子见南子,子路不①HelenLegge,JamesLegge:MissionaryandScholar.London:TheReligiousTractSociety,19 05,P.37②王韬:《瞍园文录外编》,上海书店出版社,2002年,第181页.③JamesLegge,TheChineseClassics,V o1.I.NewY ork:DoverPublications,Inc.1971,P.137—138.理雅各对中国文化的尊重与包容——从"译名之争"到中国经典翻译49说",孔子见南子,子路为何不高兴?应该说译文准确无误,但外国读者仍然会感到纳闷.因此,理雅各在脚注中说明,南子生性淫荡.这样一来,读者的疑问也就释然了.理雅各研究翻译《论语》,并不等于他放弃了西方的文化概念.他时而在脚注中发表对孔子某些言行的不同看法,体现出他对中西文化冲撞的包容,如《雍也》中"孟之反不伐,奔而殿,将入门,策其马,日:'非敢后也,马不进也."'孔子是在宣扬功不独居,过不推诿的美德,而从西方人的价值取向而言,这并不是美德,而是不够实事求是.因此,理雅各在脚注中反问道:"偏离事实,何德之有?孔子怎么会以此来表扬他(孟之反)呢?"理雅各对中国人不喜张扬的处世之道提出了质疑,客观地反映了中西方文化的碰撞.综而论之,理雅各翻译中国经典最大的特点就是紧扣原文,语义翻译,从而在最大程度上保留原语的韵味,尊重原语的特点.纽马克认为,翻译权威作品和哲学着作应采用语义翻译法(seman—tictranslation).语义翻译是指"在译入语语义和语法结构允许的前提下,尽可能准确地再现原文的上下文意义"①.因为体现原作思维过程的语言形式和句法都是"神圣"的,所以语义翻译采用较小的翻译单位,力求保持原作的语言特色和独特的表达方式.译者首先要尊重作者,其次要尊重原语,最后才去考虑读者.德国着名古典语言学家,翻译理论家施莱艾尔马赫在《论翻译的方法》一文中也谈到,翻译的途径只有两种,一种是让作者安居不动,而引导读者去接近作者;另一种是尽可能让读者安居不动,而引导作者去接近读者.美国翻译理论家韦努蒂在其《论译者的隐身》中将前者称为"异化法",将第二种方法称为"归化法".这两种翻译方法分别与传统的直译和意译有着异曲同工之妙.理雅各的翻译方法即为异化法,或称语义翻译法,从比较文化的角度看,他的这种译法在最大程度上保持了原语文化的原汁原味,最大限度地保证了原语文化的正确传递,充分体现了他对中国文化的宽容态度.总之,作为西方来华传教士,不可否认,理雅各在"译名之争"过程中的一些论证有失粗疏,甚至有时是牵强附会的,在很大程度上是为传教服务的,但他在这一过程中引据中国传统典籍的理念以及在翻译中国经典过程中对自己的理念的充分体现无疑都反映出他对中国文化的尊重与包容.他忠实地向西方传播了中国传统文化,既不同于同时代其他传教士的西方文化优越论,更为以后的中西文化建构和交流带来深刻启示.正如他自己所说的那样:"真的,他们(中。

介绍郑和与哥伦布的海外探索英语作文全文共3篇示例,供读者参考篇1IntroductionZheng He and Christopher Columbus were two prominent explorers who undertook significant sea voyages during the Age of Exploration. While they operated in different regions and pursued different goals, both individuals made significant contributions to the understanding of the world and the expansion of trade and cultural exchange.Background of Zheng HeZheng He was a Chinese explorer who lived during the Ming Dynasty in the 15th century. He was a eunuch and a trusted advisor to the emperor, tasked with leading a series of maritime expeditions to show the power and prestige of China. ZhengHe's voyages were massive in scale, involving a large fleet of ships and thousands of men. He traveled to Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian Peninsula, and the east coast of Africa, establishing trade relationships and spreading Chinese influence.Background of Christopher ColumbusChristopher Columbus was an Italian explorer who sailed for the Spanish crown in the late 15th century. He is best known for his expeditions to the New World, which he believed to be Asia. Columbus's voyages in 1492, 1493, and 1498 led to the first permanent European contact with the Americas, opening up a new era of exploration and colonization.Comparison of VoyagesWhile Zheng He and Columbus both conducted significant sea voyages, their motivations and methods were quite different. Zheng He's voyages were primarily diplomatic and commercial in nature, aimed at asserting Chinese power and expanding trade networks. He traveled to established civilizations and conducted diplomacy with foreign rulers. In contrast, Columbus's voyages were driven by the desire to find a new trade route to Asia and to spread Christianity. He had less diplomatic support and often used force to establish colonies in the Caribbean.Impact of ExplorationThe expeditions of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus had a lasting impact on world history. Zheng He's voyages helped to spread Chinese culture and influence across the Indian Ocean, paving the way for future trade relationships and diplomatic ties. Columbus's voyages led to the European colonization of theAmericas and the eventual establishment of a global trade network. While both explorers faced challenges and controversies in their time, their contributions to the exploration of the world cannot be denied.ConclusionZheng He and Christopher Columbus were two influential explorers whose sea voyages shaped the course of history. While their methods and motivations differed, both individuals played a crucial role in expanding trade networks, establishing diplomatic relationships, and promoting cultural exchange. Their legacies continue to be studied and celebrated today, serving as a reminder of the importance of exploration and discovery in human history.篇2Introduction:In the Age of Exploration, two significant figures emerged as key players in the expansion of global trade and the discovery of new lands: Zheng He and Christopher Columbus. Both individuals embarked on ambitious voyages that greatly impacted world history. While their motivations andaccomplishments differed, their legacy lives on as legends of maritime exploration.Zheng He:Zheng He was a Chinese admiral and diplomat who led seven major expeditions to Southeast Asia, South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa between 1405 and 1433. His voyages were part of the Ming Dynasty's efforts to establish Chinese dominance in the Indian Ocean trade network and project China's power abroad.Zheng He's fleet consisted of massive treasure ships, some reportedly as long as 400 feet, and encompassed hundreds of ships and thousands of men. He established diplomatic relations, exchanged gifts, and promoted trade with kingdoms and empires along the maritime Silk Road.Despite the grandeur of his expeditions, Zheng He's voyages were not primarily motivated by colonization or conquest. Instead, he sought to showcase Chinese civilization and strengthen diplomatic ties through the exchange of tributary gifts. His voyages were remarkable for their scale, organization, and peaceful interactions with foreign lands.Christopher Columbus:Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer who made four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean between 1492 and 1504. His first voyage, sponsored by the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, led to the European discovery of the Americas.Columbus set out to find a westward route to Asia in search of wealth and glory. On October 12, 1492, he landed in the Bahamas, believing he had reached the East Indies. Columbus's voyages marked the beginning of European colonization in the Americas and the initiation of the Columbian Exchange, which facilitated the transfer of goods, ideas, and diseases between the Old World and the New World.Columbus's legacy is complex and controversial, as his expeditions resulted in the decimation of Indigenous populations and the establishment of European empires in the Americas. While he is celebrated as a pioneer of transatlantic exploration, his actions have also been criticized for their negative impact on Indigenous peoples.Comparison:Zheng He and Christopher Columbus were both visionary explorers who undertook daring maritime voyages during the Age of Exploration. However, their motivations and methods differed significantly.Zheng He's expeditions were characterized by diplomacy, trade, and cultural exchange. He sought to showcase China's power and prestige through peaceful interactions with foreign lands. In contrast, Columbus's voyages were driven by a quest for wealth and conquest, leading to the European colonization of the Americas and the exploitation of Indigenous peoples.Despite these differences, Zheng He and Columbus were instrumental in expanding global trade networks and connecting distant lands. Their voyages laid the foundation for the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures that shaped the modern world.Conclusion:Zheng He and Christopher Columbus were pioneering figures in the history of maritime exploration, whose voyages had a profound impact on global trade and cultural exchange. While their motivations and legacies are complex, their expeditions mark a crucial period of exploration and discovery that continues to shape our understanding of the interconnectedness of the world.篇3Introduction:Exploration has always been an integral part of human history, with many famous explorers embarking on daring journeys to uncover new lands and cultures. Two such explorers who made significant contributions to the age of exploration were Zheng He and Christopher Columbus. While both men set out on sea voyages during the 15th century, their backgrounds, motivations, and impacts on history were vastly different. In this essay, we will explore the lives and voyages of Zheng He and Christopher Columbus, comparing and contrasting their achievements and legacies.Zheng He:Zheng He, also known as Cheng Ho, was a eunuch admiral of the Ming Dynasty in China. Born in 1371, Zheng He was a Muslim and a trusted advisor to the emperor of China. In his lifetime, he embarked on seven major voyages in the early 15th century, traveling as far as East Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Zheng He's fleet was composed of massive ships known as "treasure ships," which were the largest wooden ships ever built at the time.Zheng He's voyages were not motivated by conquest or colonization but instead by a desire to establish diplomatic and trade relations with other countries. His missions brought backexotic goods, animals, and treasures to China, boosting the country's economy and cultural exchange. Zheng He's journeys also showcased China's naval prowess and technological advancements to the world, solidifying the country's position as a maritime power.Despite his accomplishments, Zheng He's expeditions were abruptly halted after his death in 1433, and China turned inward, focusing on domestic affairs. Zheng He's voyages were largely forgotten until the 20th century when his exploits were rediscovered and celebrated as a remarkable feat of exploration and diplomacy.Christopher Columbus:Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer commissioned by the Spanish monarchy to find a new trade route to Asia by sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean. Columbus believed that reaching Asia by sailing west would be faster and more lucrative than the traditional land routes through the Middle East. In 1492, Columbus set sail with three ships, the Nina, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria, and landed in the Bahamas, opening the way for European exploration of the Americas.Columbus's voyages were driven by a quest for riches, fame, and the spread of Christianity. His discovery of the Americas hada profound impact on global history, leading to the Columbian Exchange, the transfer of goods, plants, animals, and diseases between the Old World and the New World. While Columbus's expeditions were marred by exploitation, slavery, and violence against indigenous peoples, his voyages paved the way for European colonization of the Americas and the globalization of trade and culture.Comparisons and Contrasts:Though Zheng He and Christopher Columbus were contemporaries who explored the seas during the 15th century, their motivations, methods, and legacies diverged significantly. Zheng He's voyages focused on diplomacy, trade, and cultural exchange, while Columbus's expeditions were driven by conquest, colonization, and the search for wealth. Zheng He's legacy emphasized China's peaceful engagement with other countries, while Columbus's legacy highlighted Europe's expansion and dominance over the Americas.In conclusion, Zheng He and Christopher Columbus were two of the most famous explorers of the age of exploration, each making significant contributions to the history of global exploration. While Zheng He's voyages showcased China's maritime power and diplomatic prowess, Columbus'sexpeditions opened the door to European colonization of the Americas and the globalization of trade and culture. Despite their differences, Zheng He and Columbus both left a lasting impact on world history, shaping the course of human civilization for centuries to come.。

五年级下册英语书第67页翻译In the long history of human society, our brave, intelligent and industrious ancestors created a rich and colorful civilization With the passage of time, some of these civilizations have become history, some have continued forever, and some have blended with each other to produce new civilizations Today, human civilization is undergoing profound changes Scientific and technological progress and economic and cultural exchanges have shortened the distance between civilizations No matter in the Champs Elysees in Paris or in Chang'an Street in Beijing, people with different clothes, different skin colors and different mother tongues can be seen walking one after another Whether in the east or the west, people's communication has never been as close as today, and the factors affecting people's daily life are no longer limited to a certain culture Culture is the soul of a nation and the basis for its survival and continuation For both the Chinese nation and the French nation, the culture we inherit and carry forward is the root of the nation and the soul of the country Cultural diversity is an important feature ofhuman civilization Cultural diversity is an objective reality to human society, just as biological diversity is to nature Only by respecting cultural diversity can human civilization developIn the final analysis, how to make different civilizations coexist and develop lies in "harmony" This is peace between countries, harmony between people, and harmony between man and nature Standing at the height of the development of human civilization, we should put peace first Is it possible for countries of different civilizations to live in peace? The answer is yes On this planet where we live, there are more than 6 billion people, more than 200 countries, more than 2500 nationalities, more than 6000 languages, Christianity, Catholicism, Islam, Buddhism, Taoism and other religions It is the interdependence, mutual exchange, mutual reference and mutual brilliance of these different civilizations that constitute today's rich and colorful world Since ancient times, China has had the idea of valuing harmony, harmony with differences, and harmony with real creatures "Peace is precious" means that unity, mutual assistance and friendly coexistence should be the highest realm among countries, nations and people; "Harmony butdifference" means that a country or a nation can not only accommodate the existence of different civilizations, but also retain its own excellent civilization tradition; "Harmonious living things" means that only when different civilizations absorb and learn from each other can they turn cultural relics into new ones and promote the progress of civilization "Harmony" is the basic spirit of Chinese cultural tradition and the ideal realm pursued by the Chinese nation As early as a thousand years ago, China's Tang Dynasty was very active in foreign exchanges There are more than 70 countries in the world that have contacts with the Tang Dynasty There were an endless stream of peaceful missions and caravans on the silk road At that time, Chinese culture spread to the Eastern Roman Empire and Arab countries. At the same time, dance, music, painting, food, clothing and religion in the Tang Dynasty also absorbed the essence of foreign culture, pushing Chinese civilization to a new peak 在人类社会的历史长河中,我们勇敢、智慧和勤劳的祖先创造了丰富多彩的文明.随着时间的推移,这些文明有的成为了历史,有的生生不息地一直延续下来,有的相互交融产生了新的文明.今天,人类文明正在发生深刻的变革.科技进步和经济文化交往缩短了各种文明之间的距离.无论在巴黎的香榭丽舍大街还是在北京的长安街,都可以看到不同服装、不同肤色、不同母语的人们接踵而行.无论在东方还是西方,人们的交往从来没有像今天这样密切,影响人们日常生活的因素已不再局限于某一种文化.文化是一个民族的灵魂,是她赖以生存和延续的基础.无论对中华民族还是对法兰西民族来说,我们各自继承和发扬的文化都是民族之根、国家之魂.文化多样性是人类文明的重要特征.文化多样性之于人类社会,就如同生物多样性之于自然界一样,是一种客观现实.只有尊重文化的多样性,才能使人类文明得以发展.如何才能使不同文明共存和发展,归根到底在于“和”.这就是国与国之间的和平,人与人之间的和睦,人与自然之间的和谐.站在人类文明发展的高度上,我们应该把和平放在第一位.不同文明的国家之间有没有可能和平相处?答案是肯定的.我们生活的这个星球上,有60多亿人口,200多个国家,2500多个民族,6000多种语言,有基督教、天主教、伊斯兰教、佛教和道教等多种宗教.正是这些不同文明的相互依存、相互交流、相互借鉴、相映生辉,才构成今天这个丰富多彩的世界.中国自古就有以和为贵、和而不同、和实生物的思想.“以和为贵”就是说国家之间、民族之间、人与人之间要以团结互助、友好相处为最高境界;“和而不同”就是说一个国家、一个民族既能容纳不同的文明存在,又能保留自己的优秀文明传统;“和实生物”就是说只有不同文明之间相互吸收借鉴,才能文物化新,推进文明的进步.“和”是中国文化传统的基本精神,也是中华民族不懈追求的理想境界.早在一千多年前,中国的唐代对外交流就非常活跃.世界上与唐朝交往的国家有七十多个.丝绸之路上和平的使团、商队络绎不绝.中国文化那时就传播到了东罗马帝国、阿拉伯国家,同时唐代的舞蹈、音乐、绘画、食品、服装、宗教也吸纳了外来文化的精华,将中华文明推向一个新的高峰.。

丝绸之路介绍作文英语The Silk Road, historically significant for its role in connecting the East and West, remains a symbol of cultural exchange and trade spanning centuries. Stretching across vast regions of Asia, Europe, and Africa, this ancient network of trade routes facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures between the civilizations of the Eastern and Western hemispheres.The origins of the Silk Road date back to the Han Dynasty of China, around 206 BCE to 220 CE. It was during this time that the Chinese Emperor Wu Di initiated diplomatic and trade missions westward, seeking alliances and access to valuable goods such as silk, spices, and other luxury items. The term "Silk Road" itself was coined much later, in the 19th century by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen, highlighting the importance of silk as one of the most coveted commodities traded along the route.The Silk Road was not merely a single route but rather a complex network of interconnected pathways that branched out from China to Central Asia, the Middle East, and eventually reaching as far as the Mediterranean region. These routes were traversed by merchants, travelers, scholars, and adventurers, facilitating not only the exchange of goods but also the transmission of ideas, religions, languages, and cultures.One of the most iconic goods traded along the Silk Road was silk, a highly prized fabric produced exclusively in China at the time. The secret of silk production wasclosely guarded by the Chinese for centuries, and its introduction to the West via the Silk Road brought about a revolution in luxury trade. However, silk was just one among many commodities exchanged; other goods included spices, precious metals, gemstones, ceramics, textiles, and exotic animals.The Silk Road also played a crucial role in the exchange of knowledge and ideas between the East and the West. Alongside merchants, Buddhist monks, scholars, andtravelers traveled the route, carrying with them not only goods but also religious beliefs, philosophical teachings, scientific discoveries, and artistic influences. It was through these interactions that Buddhism, Islam, Christianity, and other religions spread across Eurasia, leaving a profound impact on the cultural and religious landscape of the regions it touched.Furthermore, the Silk Road facilitated the exchange of technologies and innovations, contributing to advancements in agriculture, metallurgy, astronomy, medicine, and architecture. For instance, the introduction of papermaking techniques from China revolutionized the way information was recorded and disseminated in the West. Similarly, the spread of gunpowder and compass technology from China to the Islamic world and eventually to Europe had transformative effects on military tactics, navigation, and exploration.The decline of the Silk Road began with the rise of maritime trade routes in the Age of Exploration, which offered faster and safer passage for goods between the Eastand the West. Additionally, geopolitical shifts, such as the fall of the Mongol Empire and the rise of powerful nation-states, further contributed to the diminishing importance of overland trade routes.However, the legacy of the Silk Road continues to resonate in the modern world. Today, efforts are underway to revive and reinvigorate the ancient routes through initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative proposed by China, which aims to promote economic cooperation, infrastructure development, and cultural exchange across Asia, Africa, and Europe.In conclusion, the Silk Road stands as a testament to the enduring human desire for connection, exploration, and exchange. Beyond its economic significance, it fostered a rich tapestry of cultural diversity, intellectual exchange, and technological innovation that continues to shape our world today. As we look to the future, the spirit of the Silk Road serves as a reminder of the potential for cooperation and collaboration across borders, fostering a more interconnected and prosperous global community.。

明清时期来华传教士的西学中译研究作者:董方峰杨洋来源:《外国语文研究》2020年第01期内容摘要:明清时期入华的西方传教士在西学中译方面做了大量工作,其译介成果对中国近现代科学技术、社会思想、语言、文学以及中西交流都起到了促进作用。

本文从西学汉译、《圣经》汉译、西方文学汉译几个方面进行回顾,揭示了传教士翻译活动对于中国近现代历史和中西交流的贡献及翻译学科史的价值。

关键词:传教士;翻译;明清时期;中西交流基金项目:国家社科基金项目“明清传教士对中国语言学的贡献研究”(12CYY002)。

作者简介:董方峰,博士,华中师范大学外国语学院副教授,主要从事语言学理论、中外语言思想史研究。

杨洋,华中师范大学外国语学院讲师,主要从事语言学及语言哲学研究。

Title:A Study of Foreign Missionaries’ Translation of Western Works into Chinese during the Ming and Qing DynastiesAbstract: During the Ming and Qing dynasties, Western missionaries to China translated large amounts of books from western languages into Chinese. Their work promoted the development of modern science and technology, society and thoughts, language and literature in modern China, and also enhanced Sino-western communications. In retrospect of their work from such aspects as western-Chinese translation, Bible translation, literature translation, this paper expounds the western missionaries’ co ntributions to modern Chinese history and the value of their work to the history of translation studies.Key words: missionaries, translation, Ming and Qing dynasties, Sino-western communicationAuthors: Dong Fangfeng is associate professor at the School of Foreign Languages, Central China Normal University (Wuhan 430079, China). His academic interests are linguistic theories and linguistic historiography. E-mail: dongff@. Yang Yang is lecturer at the School of Foreign Languages, Central China Normal University (Wuhan 430079, China). Her academic interests are linguistics and philosophy of language. E-mail: yang.y@一、引言在中國历史上,出现过几次翻译高潮。

On Missionaries and the Translation of Chinese Confucian Classics from the Perspective of the History of Translated Literature 作者: 杨国强[1] 王正英[2]

作者机构: [1]山东枣庄学院大学英语教学部,山东枣庄277160 [2]山东枣庄科技职业学院,山东枣庄277160

出版物刊名: 安庆师范学院学报:社会科学版

页码: 31-34页

年卷期: 2012年 第3期

主题词: 翻译文学史 传教士 儒家经典 译介

摘要:西方传教士翻译了大量儒家经典,传播了儒家文化,促进了中西文化交流。

西方传教士的翻译选题动机是为了调和中西文化,将基督教根植于中国社会的肌体。

代表译者主要有利玛窦、理雅各和卫礼贤等,主要译介成就是对"四书五经"的外译。

传教士对儒家经典的译介与研究引起很大的反响,参与并影响了西方社会发展的进程,也深深影响了许多艺术家与学者。

在译介儒家经典的过程中也出现了歪曲儒家经典原意的现象,对此学术界应有清醒的认识。

翟理思(Herbert Allen Giles,英国,1845-1935)作品大致可以分为四大类,即语言教材、翻译、工具书和杂论四大类。 《汉言无师自明》(Chinese without a Teacher: Being a Collection of East and Use Sentences in the Mandarin Dialect, with a Vocabulary) 这本书最大的特点就是使用简单的

英语给汉语注音。 《字学举隅》( Synoptical Studies in Chinese Character)。这是一个辨析同形异义或同形异音字的汉语学习教材。 《汕头方言手册》( Handbook of the Swatow Dialect, with a vocabulary ), 《百个最好的汉字》( The Hundred Best Characters)。他的用意在于,“有了这些词汇表,我们根据相关的情境造了一些新的句子。所以,学生们就可以随心所欲地说汉语了,而不必事先在头脑里装满了那些他可能从来都用不着的词汇。” 《两首中国诗》( Two Chinese Poems),其中收录了韵体《三字经》和《千字文》英译文。 《闺训千字文》或《女千字文》(A Thousand-Character Essay for Girls ) 《洗冤录》(Hsi Yuan Lu, or Instructions to Coroners)。英国皇家医学会(Royal Society of Medicine )《皇家医学会论文集》第17卷“医学史”专章(Section of the History of Medicine )

《佛国记》CA Record of the Buddhistic Kingdoms ),又称《法显传》。 《佛国记》新译本,新译本的英文书名为“The Travels of Fa-hsien (399-414 A. D.), or Record of the Buddhistic Kingdoms, Retranslated by\' N. A. Giles, With an Illustration and a Map”。 《古文选珍》( Gems of Chinese Literature)总体文学 ( general literature) 《古今诗选》( Chinese Poetry in English Verse),其中选译了大量中国古诗。 。第二版《古文选珍》是在修订、增补第一版的《古文选珍》和《古今诗选》的基础上完成的。新版的《古文选珍》分为两卷:散文卷和诗歌卷。 《庄子:神秘主义者、伦理学家、社会改革家》( ChuangTzu, Mystic, Moralist, and Social Reformer)译本分为三大部分:引言、庄子哲学札记、译文。

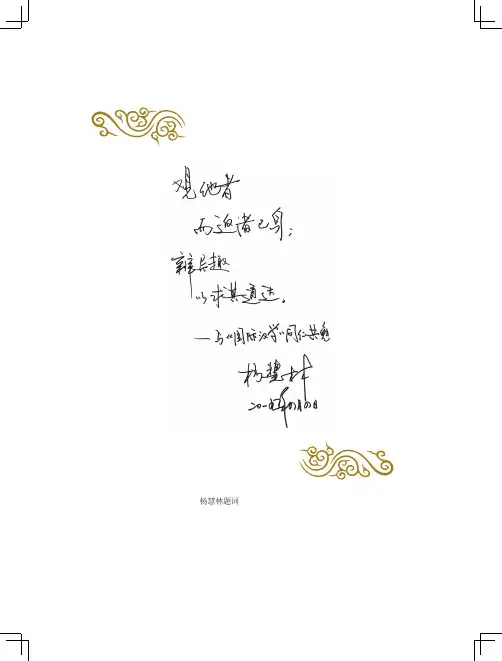

杨慧林题词

杨慧林,中国人民大学教授,第七届国务院学科评议组成员,中国人民大学学术委员会副主任,主要从事比较文学和宗教学研究。

近年出版的学术著作有《意义:当代神学的公共性问题》(北京大学出版社,2013年、2018年)、《圣言·人言:神学诠释学》(福建教育出版社,2018年修订版)、《西方文论概览》(中国人民大学出版社,合著,2013年)、《在文学与神学的边界》(复旦大学出版社,2012年)以及英文论文集China, Christianity and the Question of Culture(Baylor University Press, 2014)。

1999年以来主编学术刊物《基督教文化学刊》,自2005年9月起该刊物被列入CSSCI核心期刊数据库,2016年被列入ESCI期刊索引数据库(Emerging Sources Citation Index)。

2010年以来主持国家社科基金重大课题“中国古代经典英

译本汇释汇校”,其五卷本成果《论语英译本汇释汇校丛书》近期将由南京大学出版社出版。

CHINESE CHRISTIANITY AND CHINA MISSIONS: WORKS PUBLISHED SINCE 1970

Authors: Lutz, Jessie G. Source: International Bulletin of Missionary Research, Jul96, Vol. 20 Issue 3, p98, 8p

http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail?vid=4&hid=10&sid=ebfc33c2-f75a-40b4-9151-d80c505d9ba4%40sessionmgr14&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=rlh&AN=9608091091

Contents

1. Contribution of Women Missionaries 2. Examining Mission Methodology 3. Roman Catholic Missions 4. The Church under the People's Republic 5. Anti-Christian Movements 6. Missionary and Chinese Biographies 7. Two-Way Transfer of Knowledge and Values 8. Long-term Impact of Christian Education and Social Service 9. Indigenization and the Chinese Church 10. Research Aids

The study of Chinese Christianity and China missions is attracting increasing attention both in China and the West, with the focus shifting toward Chinese Christians rather than Western missionaries. The following bibliography represents a selection from among the many books that have been published on the topic during the last quarter century.

An excellent overall survey of China missions during the nineteenth century is Paul A. Cohen, "Christian Missions and Their Impact to 1900," in The Cambridge History of China, vol. 10, Late Ching, 1800-1911, ed. John K. Fairbank (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1978), pp. 543-90. Still useful also is the collection of essays edited by John Fairbank and containing his introductory remarks on the significance of missions in intercultural relations between China and the West: The Missionary Enterprise in China and America (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1974). The compilation American Missions in Bicentennial Perspective, edited by R. Pierce Beaver (Pasadena, Calif.: Wm. Carey Library, 1977), is worth consulting as well. A recent collection focusing on the Chinese Christian church and issues of indigenization is Daniel H. Bays, ed., Christianity and China, the Eighteenth Century to the Present: Essays in Religious and Social Change (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford Univ. Press, 1996).

More specific historical studies of merit are Alvyn J. Austin, Saving China: Canadian Missionaries in the Middle Kingdom, 18881959 (Toronto: Univ. of Toronto Press, 1986); George Hood, Mission Accomplished? The English Presbyterian Mission in Lingtung, South China: A Study of the Interplay Between Mission Methods and Their Historical Context (Frankfurt am Main: Verlag Peter Lang, 1986); Gerald F. DeJong, The Reformed Church in China, 1842-1951 (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1992); Herbert Hoi-Lap Ho, Protestant Missionary Publications in Modern China, 1912-1949: A Study of Their Programs, Operations, and Trends (Hong Kong: Chinese Church Research Center, 1988); Fernandos Mateos, S.J., China Jesuits in East Asia: Starting from Zero, 1949-1957 (Taipei: n.p., 1995); and T'ien Ju-k'ang, Peaks of Faith: Protestant Missions in Revolutionary China (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1993).

In The Liberating Gospel in China: The Christian Faith Among China's Minority Peoples (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 1995), Ralph R. Covell argues that missionaries missed an opportunity in neglecting China's minorities, many of whom responded more positively to Christianity than did most Han Chinese. He employs a contextual approach to explain why some minorities were resistant while others enthusiastically embraced Christianity. Ellsworth C. Carlson, in The Foochow Missionaries, 1847-1880 (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1974), discusses the expectations of American missionaries as they departed for China and their reactions to the Chinese and the Chinese environment; he also includes detail on the "poison scare" of 1871 and the Wushishan Incident of 1878. Illustrated in Sidney A. Forsythe, An American Missionary Community in China, 1895-1905 (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1971) is the tendency for Protestant missionaries to congregate in the treaty ports in insulated Western enclaves, a practice that is in many ways understandable but that has often been sharply criticized.

Earthen Vessels: American Evangelicals and Foreign Missions, 1880-1980, edited by Joel A. Carpenter and Wilbert R. Shenk (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1990), though not confined to China, is a welcome addition to mission literature. Until recently, evangelicals have shown little interest in historical or methodological studies, and it has sometimes been assumed that the era of expanding Protestant missions has passed. Though such may be true of the mainstream denominations, Earthen Vessels demonstrates that the same is not true for evangelicals, who today constitute the great majority of American missionaries. See also Leonard Bolton, China Call: Miracles Among the Lis u People (Springfield, Mo.: Gospel Publishing House, 1984).