Knowledge management literature review

- 格式:doc

- 大小:414.50 KB

- 文档页数:21

英文文献综述标准范文As the globalization of the world economy continues to deepen, English has become the most widely used language in the world. In academic research, English literature plays an important role in the dissemination of knowledge and the exchange of academic ideas. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive review of English literature in order to understand the latest research trends and developments in various fields.A standard English literature review should begin with a clear introduction to the topic of the review. This introduction should provide an overview of the research area, the purpose of the review, and the scope of the literature that will be covered. It is important to clearly define the research questions or objectives that the review aims to address, and to explain the significance of the topic in the broader academic context.The main body of the literature review should be organized thematically, rather than by individual works or authors. This means that the review should be structured around key themes or topics that are relevant to the research area, and should provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge in each ofthese areas. Each thematic section should begin with a brief introduction to the topic, followed by a critical analysis of the relevant literature. This analysis should include a discussion of the key theories, methodologies, and findings of the research in each area, as well as an evaluation of the strengths and weaknesses of the existing literature.In addition to organizing the literature thematically, it is also important to critically evaluate the quality of the research that is reviewed. This involves assessing the validity and reliability of the research methodologies that have been used, as well as the credibility and impact of the findings that have been reported. It is important to consider the strengths and limitations of the research that has been reviewed, and to identify any gaps or inconsistencies in the existing literature that may require further investigation.Finally, the literature review should conclude with a summary of the key findings and insights that have emerged from the review. This summary should highlight the most important contributions that have been made to the research area, and should also identify any areas where further research is needed. It is important to emphasize the implications of the review for future research, and to consider thebroader implications of the findings for the academic community.In conclusion, a standard English literature review should provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of knowledge in a particular research area, and should critically evaluate the quality and impact of the existing literature. By following a clear and systematic approach to reviewing the literature, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of the latest research trends and developments, and can identify new opportunities for further investigation.。

阅读文献资料进行调研的综述英文回答:Introduction:Literature review synthesis is a research method that involves the systematic and critical evaluation of existing literature on a particular topic. It allows researchers to synthesize and interpret findings from multiple studies to provide a comprehensive understanding of the current state of knowledge on a given subject.Steps in Conducting a Literature Review Synthesis:1. Formulate a research question: Clearly define the specific topic or issue to be investigated.2. Identify relevant literature: Conduct a comprehensive search using databases, academic journals, and other sources to locate relevant studies.3. Evaluate study quality: Assess the methodological rigor and reliability of the studies included in the synthesis.4. Extract and analyze data: Synthesize and interpret the key findings from each study, identifying patterns, inconsistencies, and gaps in the literature.5. Draw conclusions: Based on the synthesis of findings, draw conclusions about the current state of knowledge and identify areas for further research.Benefits of Literature Review Synthesis:Provides a comprehensive overview of existing research on a specific topic.Helps identify gaps in knowledge and areas for future research.Supports evidence-based decision-making.Facilitates the development of new theories and models.Enhances understanding of complex topics through the consolidation of findings from multiple studies.Methodological Considerations:Inclusion criteria: Establish clear criteria for selecting studies to ensure relevance and quality.Data synthesis: Use appropriate methods for synthesizing data, such as narrative synthesis, meta-analysis, or systematic review.Bias management: Minimize bias by following rigorous research procedures and conducting independent reviews.Transparency and replicability: Ensure transparency by providing detailed documentation of the research processand making findings reproducible.Applications of Literature Review Synthesis:Literature review synthesis is widely used in various research disciplines, including:Social sciences.Education.Health sciences.Policy analysis.Business and management.中文回答:综述:文献资料调研综述是一种研究方法,涉及对某个特定主题的现有文献进行系统和批判性的评估。

英文文献综述撰写要点Title: Key Points for Writing an English Literature ReviewIntroduction:A literature review is an essential component of academic research, providing a comprehensive overview of existing knowledge and research on a specific topic. Writing a literature review in English involves following certain key points to ensure its value and quality. This article will explore the important aspects of writing an English literature review, emphasizing structure, depth, and the writer's perspective.I. Understanding the Purpose and Scope of the Literature Review:1. Definition: Explain the purpose of a literature review, which is to identify and analyze the existing literature on a specific topic.2. Scope: Define the boundaries of your literature review, such as the time period, geographical location, or specific subtopics to be covered.3. Research Questions: Highlight the key research questions that your literature review aims to answer.II. Conducting a Systematic Search for Relevant Literature:1. Identify Relevant Databases: Discuss the selection of appropriate academic databases, libraries, and search engines to ensure a comprehensive collection of relevant literature.2. Search Techniques: Explain advanced search techniques, such as Boolean operators, truncation, and proximity searching, to optimize your literature search.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: Describe the criteria used to include or exclude specific literature from your review, ensuring relevance and quality.III. Organizing and Structuring the Literature Review:1. Introduction: Provide a concise introduction that outlines the purpose, scope, and relevance of the literature review.2. Main Body: Organize the literature review thematically, chronologically, or methodologically, depending on the research questions and available literature.3. Synthesis and Analysis: Critically evaluate and compare the findings of different studies and authors, identifying trends, debates, contradictions, and gaps in the literature.4. Conclusion: Present a summary of the main findings, emphasizing their significance and implications for futureresearch.IV. Evaluation of the Literature:1. Quality Assessment: Develop a framework to assess the quality and reliability of the included literature sources, such as peer-reviewed journals or reputable publishers.2. Critical Analysis: Analyze the strengths and limitations of each literature source, considering methodology, sample size, data analysis, and potential bias.3. Validity and Reliability: Discuss the validity and reliability of the key findings presented in the literature, highlighting any conflicting or inconclusive evidence.V. Writer's Perspective and Understanding:1. Impartiality and Objectivity: Emphasize the importance of maintaining an impartial and objective perspective throughout the literature review while acknowledging the writer's personal biases.2. Interpretation and Insights: Offer your perspectives and insights on the literature, discussing the implications of the findings, potential research directions, and unanswered questions.3. Future Recommendations: Provide recommendations forfurther research based on your understanding of the literature and identified knowledge gaps.Conclusion:Writing a high-quality English literature review requires a systematic approach and adherence to key points such as understanding the purpose and scope, conducting a comprehensive literature search, organizing the review effectively, evaluating the quality of sources, and providing a writer's perspective. By following these guidelines, you can produce a valuable literature review that contributes to the existing knowledge on your chosen topic.Word Count: 381。

成本管理国内外文献综述英文回答:Cost Management: A Comprehensive Literature Review.Cost management is a critical aspect of business operations, as it enables organizations to optimize resource allocation, reduce expenses, and improve profitability. This literature review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of cost management research, exploring its various dimensions, methodologies, and best practices.Historical Evolution and Theoretical Foundations.The concept of cost management has evolved over time, from its roots in traditional accounting practices to its modern emphasis on strategic decision-making. Researchers have proposed numerous theories and frameworks to explain cost behavior and optimize cost management processes. Theseinclude activity-based costing (ABC), target costing, and value-based costing (VBC).Cost Classification and Estimation Techniques.Cost management requires a comprehensive understanding of cost classification systems and estimation techniques. Direct costs are directly attributable to specific products or services, while indirect costs are shared acrossmultiple activities. Estimation methods, such as time and motion studies, parametric modeling, and simulation, provide reliable estimates for various cost elements.Cost Reduction and Optimization Strategies.Organizations employ various strategies to reduce costs and optimize their operations. Value analysis, process mapping, and lean manufacturing principles help identify and eliminate waste and improve efficiency. Cost-benefit analysis and risk management techniques assess thepotential outcomes of cost-saving initiatives.Technology and Cost Management.Technological advancements have significantly influenced cost management practices. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems provide real-time data and analytics for better cost monitoring and decision-making. Cloud computing and machine learning algorithms automate cost analysis and forecasting tasks.International Perspectives on Cost Management.Cost management practices vary across countries due to differences in economic, regulatory, and cultural factors. International organizations face challenges in applying uniform cost management standards and achieving cost synergies across their global operations.Emerging Trends and Future Directions.Current trends in cost management include a focus on sustainability, digital transformation, and data-driven decision-making. Researchers are exploring the use ofartificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain technology to enhance cost management capabilities.中文回答:成本管理综述。

重庆科技学院学术英语课程论文文献综述题目:A Preliminary Exploration on theConstitutionalPrinciples andFormative Methods of Euphemism委婉语的构造原则和构成方式初探学生姓名:指导教师:院系:专业、班级:学号:完成时间:2015年6月说明:封面标题要用中英双语,英文题目在上.英文题目的实词首字母均须大写,字体:西文Arial;字号:3号;中文题目黑体三号。

段落安排:行距固定值28磅.对齐方式:两端对齐.学生姓名、教师姓名等一律用黑体三号,单倍行距Literature Review说明:标题Literature Review 首字母均须大写,字体:西文Arial;字号:3号;段落安排:段前24磅,段后18磅;单倍行距。

对齐方式:居中。

1。

IntroductionAs a widespread and popular rhetorical device,euphemisms came into people's life long time ago. …….And the research of euphemisms has a long history …………….。

建议:综述前写一导言,简介研究课题主要内容,概括研究现状,研究目的。

2。

The definition of euphemism说明:标题序号与标题名之间,加圆点,并空1个英文字符;标题第一个单词的首字母大写;字体:西文Arial;字号:小3号;段落安排:段前空24磅,段后空6磅;行距:固定值20磅.对齐方式:左对齐。

The word euphemism comes from Greek;the prefix eu—means good and the stem phemism means speech;the whole word‘s literal meaning is word of good omen. In early 1580s, the British writer George Blunt first created the word euphemism ‘and defined it as ‘a good or favorable interpretation of a bad word’. (Shu, 1995:17)(正文中直接引用原文,必须加引号并标出确切的页码)……………………………(正文字体:小四号罗马体,行距为固定值20磅,对齐方式:两端对齐;段首空四个英文字符)3。

企业财务风险管理外文文献Enterprise Financial Risk Management: A Literature ReviewAbstractThe enterprise financial risk management (EFRM) is a crucial tool applied by modern enterprise to manage their financial exposure and control risks. EFRM systems have become increasingly complex with time and one must have a thorough knowledge of the different facets of enterprise finance in order to effectively use them. This literature review briefly reviews existing literature and provides current understanding of the EFRM systems. Key topics discussed include the need for EFRM and the various risk management frameworks, regulations, and tools. Additionally, recent research efforts on areas such as Enterprise Risk Management Systems (ERM) and financial forecasts are discussed.1. IntroductionRisk management is an important aspect of corporate management and is extensively applied in modern enterprises. With the emergence of globalization, uncertainties, and complexity in the global business environment, effective risk management is a necessity for all corporations. Enterprises must manage different types of risks associated with inadequate financial results, including liquidity issues, treasury and debt management, insolvency or bankruptcy, and others. Enterprise Financial Risk Management (EFRM) has become an increasingly important tool to manage the risks associated with corporate financial activities. The purpose of this review is to explorethe most recent advances and research in the field of EFRM to providea comprehensive understanding of the current state of the field.2. Need for EFRMFinancial risks are a major concern in the management of any business. Inadequate risk management can lead to financial losses and even bankruptcy. The EFRM system helps to alleviate the associated financial risks. Financial risks can arise from various sources, such as external environment changes, inadequate financial planning, and insufficient internal control systems. Therefore, enterprises should implement proper EFRM strategies to protect their financial health and minimize the associated risks.EFRM systems provide the enterprise with a comprehensive risk management framework, allowing them to identify and address any existing and potential financial risks. This risk management system also enables the enterprise to analyze the short-term and long-term effects of different management decisions and to plan and implement adequate responses. Furthermore, EFRM systems facilitate financial forecasting and help management to make informed decisions. Proper risk management reduces uncertainty and increases the enterprises’ profitability.3. EFRM Risk Management FrameworksThe first step in EFRM is to identify different financial risks. Risks can be divided into two broad categories, namely, market risks and operational risks. Market risks are the risks associated with different types of financial markets, such as foreign exchanges, stocks,commodities, and interest rates. On the other hand, operational risks are the risks associated with the operations of the enterprise. These risks involve internal factors such as personnel, policies, and procedures.Once the financial risks have been identified, the enterprise should develop a risk management strategy and goals that cover the different types of risks. Different risk management tools and techniques can be used to address these risks. These tools and techniques include the use of financial analysis, financial simulation, portfolio management, financial derivatives, and enterprise risk management systems (ERM). Additionally, regulations and compliance must be taken into account when devising a risk management framework.4. Regulations and ToolsAnother important aspect of EFRM is the application of regulations. The enterprise should ensure compliance with all applicable regulators and laws and should develop a comprehensive risk management system that adheres to all the relevant laws and regulations. Furthermore, enterprise risk management systems (ERM) have become increasingly important in the management of financial risks. ERM systems are computer-based systems that allow enterprises to manage their financial risks in an efficient and integrated manner. These systems provide support in forecasting, reporting, and decision-making.5. Recent Research EffortsOver the past few years, there has been an increasing number of research studies in the field of EFRM. Some of the recent research efforts include the development of models for financial forecasts, the assessment of ERM systems, the design of financial derivatives and structured products, and the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning in financial forecasting. Further research is needed to identify new techniques and approaches that can be used to improve the effectiveness of the EFRM systems.6.ConclusionIn conclusion, effective EFRM is essential for a successful enterprise due to the increasing complexity of the global business environment. Risk management tools, techniques, and regulations must be applied to address the different types of financial risks. Additionally, research efforts in the field of EFRM are continuously increasing, and it is important to keep up to date with the latest developments.。

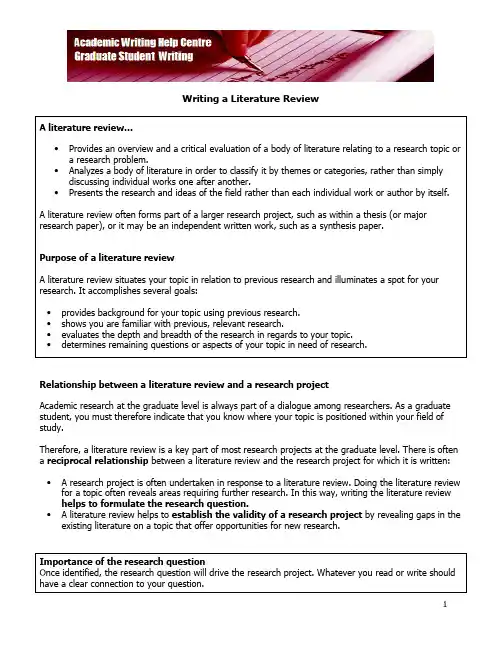

Writing a Literature ReviewA literature review…•Provides an overview and a critical evaluation of a body of literature relating to a research topic ora research problem.•Analyzes a body of literature in order to classify it by themes or categories, rather than simply discussing individual works one after another.•Presents the research and ideas of the field rather than each individual work or author by itself.A literature review often forms part of a larger research project, such as within a thesis (or major research paper), or it may be an independent written work, such as a synthesis paper.Purpose of a literature reviewA literature review situates your topic in relation to previous research and illuminates a spot for your research. It accomplishes several goals:•provides background for your topic using previous research.•shows you are familiar with previous, relevant research.•evaluates the depth and breadth of the research in regards to your topic.•determines remaining questions or aspects of your topic in need of research.Relationship between a literature review and a research projectAcademic research at the graduate level is always part of a dialogue among researchers. As a graduate student, you must therefore indicate that you know where your topic is positioned within your field of study.Therefore, a literature review is a key part of most research projects at the graduate level. There is often a reciprocal relationship between a literature review and the research project for which it is written:• A research project is often undertaken in response to a literature review. Doing the literature review for a topic often reveals areas requiring further research. In this way, writing the literature review helps to formulate the research question.• A literature review helps to establish the validity of a research project by revealing gaps in the existing literature on a topic that offer opportunities for new research.Importance of the research questionOnce identified, the research question will drive the research project. Whatever you read or write should have a clear connection to your question.How to write a strong literature reviewThere are several steps toward writing a strong literature review:1.Synthesize and evaluate information2.Identify the main ideas of the literature3.Identify the main argument of the literature reviewanize the main points of the literature review5.Write literature review1. Synthesize and evaluate informationA literature review requires critical thinking, reading, and writing. You will take the information that you have gathered through your research and synthesize and evaluate it by indicating important ideas and trends in the literature and explaining their significance.Strategies for reading•As soon as you begin reading, take note of the themes or categories that you see emerging. These may be used later to develop a structure for the literature review.•Take note of how other writers classify their data, the literature in their fields, etc. It can be helpful to read literature reviews in your discipline to see how they are structured.Categories for analysis and comparisonA strong literature review examines each work on its own and in relation to other works by identifying and then analyzing them with regards to a number of different research aspects and ideas. Here are some possible categories to use for comparison and analysis.topicargumentresults found and conclusions methodstheoretical approach key wordsOverall, a literature review seeks to answer the following questions:•What does the literature tell you?•What does the literature not tell you?•Why is this important?Questions for analyzing individual works-What is the argument? Is it logically developed? Is it well defended?-What kind of research is presented? What are the methods used? Do they allow the author to address your research question effectively? Is each argument or point based on relevant research?If not, why?-What theoretical approach does the author adopt? Does it allow the researcher to make convincing points and draw convincing conclusions? Are the author’s biases and presuppositions openlypresented, or do you have to identify them indirectly? If so, why?-Overall, how convincing is the argument? Are the conclusions relevant to the field of study? Questions for comparing works-What are the main arguments? Do the authors make similar or different arguments? Are some arguments more convincing than others?-How has research been conducted in the literature? How extensive has it been? What kinds of datahave been presented? How pertinent are they? Are there sufficient amounts of data? Do theyadequately answer the questions?-What are the different types of methodologies used? How well do they work? Is one methodology more effective than others? Why?-What are the different theoretical frameworks or approaches used? What do they allow the authors to do? How well do they work? Is one approach more effective than others? Why?-Overall, is one work more convincing than others? Why? Or are the works you have compared too different to evaluate against each other?The Academic Writing Help Centre offers more information on synthesis and evaluation in the discussion group and accompanying handout on Information Management for a Literature Review.2. Identify the main ideas of the literatureOnce you have begun to synthesize your research, you will begin to identify some main ideas and trends that pervade the topic or that pertain to your research question.Use these main ideas to classify the information and sources that you have read. Later, these ideas can be used as the main topics of discussion in the literature review, and if you have already organized your literature on these topics, it will be easy to summarize the literature, find examples, etc.3. Identify the main argument of the literature reviewJust like any academic paper, the literature review should have a main idea about the literature that you would like the readers to understand. This argument is closely related to your research question in that it presents a situation in the body of literature which motivates your research question.ExampleArgument from a literature review: “Although some historians make a correlation between the Ukrainian Catholic and Orthodox churches and the retention of Ukrainian culture and language by Ukrainian immigrants in Canada, little has been said of the role of the Roman Catholic Church in the development of Ukrainian communities in Canada.”Research question:“How has the Roman Catholic Church shaped Ukrainian-Canadian identity?”4. Organize the main points of the literature reviewAfter identifying the main ideas that need to be presented in the literature review, you will organize them in such a way as to support the main argument. A well-organized literature review presents the relevant aspects of the topic in a coherent order that leads readers to understand the context and significance of your research question and project.As you organize the ideas for writing, keep track of the supporting ideas, examples, and sources that you will be using for each point.5. Write the literature reviewOnce the main ideas of the literature review are in order, writing can flow much more smoothly. The following tips provide some strategies to make your literature review even stronger.Tips for Writing and PresentationGive structure to the literature review.Like any academic paper, a literature review should contain an introduction, a body and a conclusion, and should be centered on a main idea or argument about the literature you are reviewing.If the literature review is a longer document or section, section headers can be useful to highlight the main points for the reader. However, the different sections should still flow together.Explain the relevance of material you use and cite.It is important to show that you know what other authors have written on your topic. However, you should not simply restate what others have said; rather, explain what the information or quoted material means in relation to your literature review.•Is there a relevant connection between a specific quote or information and the corresponding argument or point you are making about the literature? What is it?•Why is it necessary to include this piece of information or quote?Use verb tenses strategically.•Present tense is used for relating what other authors say and for discussing the literature, theoretical concepts, methods, etc.“In her article on biodiversity, Jones stipulates that ….”In addition, use the present tense when you present your observations on the literature.“However, on the important question of extinction, Jones remains silent.”•Past tense is used for recounting events, results found, etc.“Jones and Green conducted experiments over a ten-year period. They determined that it was not possible to recreate the specimen.”BibliographyBell, Judith. Doing Your Research Project: A Guide for First-time Researchers in Education, Health and Social Science.Maidenhead, Berkshire: Open University Press, 2005.Boote, David N. and Penny Beile. “Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation.” Educational researcher, 34.6 (2005): 3-15.Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, and Joseph M. Williams. The Craft of Research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.Verma, Gajendra K. and Kanka Mallick. Researching Education: Perspectives and Techniques. London: Falmer Press, 1999.The Writing Center, University of North Carolina – Chapel Hill. Literature Reviews. Chapel Hill, NC. 2005. Available /depts/wcweb/handouts/literature_review.html.© 2007 Academic Writing Help Centre, University of Ottawawww.sass.uottawa.ca/writing 613-562-5601 cartu@uOttawa.ca。

ISSN1750-9653,England,UKInternational Journal of Management Scienceand Engineering ManagementV ol.2(2007)No.4,pp.278-288A thoretical review of knowledge management and teamworking in theorganizations∗Juan A.Marin-Garcia1†,Elena Zarate-Martinez21School of Industrial Engineering and School of Management.Universidad Politcnica de Valencia.Spain2Institute for Innovation and Knowledge Management(INGENIO/CSIC/UPV).Camino de Vera s/n.PolytechnicInnovation City(Received March62007,Accepted July82007)Abstract.Human Resource Management relevance in Knowledge M9anagement had been studied in the academic literature focuses mostly on recruitment,selection,wages and salaries and career development processes.We’ve found little publications taking in account the group of persons that generates,share and transfer that knowledge working in teams.The aim of this paper is to propose a framework that describes the relationship between knowledge management and teamworking,integrating proposals and to outline some considerations for further research.Keywords:knowledge management,team work,human resources management1IntroductionAs the literature shows,knowledge management(KM)is an important component for the maintenance of the organizations competitive advantage[8,10,19,24,48].Those KM programs should not be an isolated program supported by a particular individual,but should be regarded as an organizational initiative[9].For that,it must be consider the culture and the motivational practices as a successful keys.It seems that knowledge management without human resource management will not raise their objectives[22,23,43].On the other hand,human resources management(HRM)had been development since it was thought as an important matter within the organizations in the80’s,but begins to have relevance and be important for the strategic formulation and competitiveness.[3,13,16,36].If this is so and KM is important for the competitiveness too,the study of both disciplines is a growing actual matter.Another research in the literature analyses the relevance of HRM in KM,focuses mostly on recruitment, selection,wages and salaries and career development processes in specific organizations[11,15,34,39,42,45,50]. Oltra[34]bases his research in why KM initiatives are not so effectives as it is hoped and how human resources practices affects them successfully.The proposal of Tare[45]suggests that it’s important not only to convince the organization for lay the foundation for the success of a KM project,but also to consider other things about personal management that sometimes are ignored.We also found some references from the psychologist point of view which study individual’s and group’s capabilities and competences treating knowledge as an additional element of it performance[31].Any other references focuses,on one hand to the individual as a knowledge generating in a personal way(knowledge worker)[1,18,21,26,29,41,46]and on the other hand,to the group of individuals that generating,∗We would like to thank the R+D+i Linguistic Assistance Office at the Universidad Politecnica of Valencia for their help in translating this paper.†E-mail address:jamarin@omp.upv.es.Published by World Academic Press,World Academic UnionInternational Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management,Vol.2(2007)No.4,pp.278-288279 sharing and transmit this knowledge by teamworking[12,40].This last matter related with KM has not so much references in the literature.All those reflections mentioned above takes us to a probably fertilefield for the study of the relationship among these disciplines.In this sense,we’ll base on knowledge management frameworks that include a human resource variable,mostly specific,teamworking,in order to know what kind of relationship is between both disciplines.2Knowledge management(KM)Considering that knowledge has been taken as one of the most valuated resources in the actual society[8,20,32,33]and constitutes an important partner in the efficiently of the production and organizational methods in order to achieve the improvement of products and services[48],it’s necessary to research its man-agement.Some authors recommend checking the assumptions about information and knowledge because it tends to use the terms interchangeably[19].In the literature we can found references that make a distinction between what is knowledge and what is not.Some argues that information is data and knowledge allows people assign significance to the information[47];others coincide in that information must have relevance and purpose,but only is knowledge if it can be interpreted and become in valuable for decision making[8,44].In addition, information must consist in data and messagesflow that are organized to describe a condition or special situation,while knowledge is concepts,beliefs,judgements,methodologies and know-how that have been processed by individuals previously[32,48].Table1.KM descriptive frameworksPillars framework (Karl Wiig,1993)It’s about knowledge exploration and adaptation;estimation and evaluation of the knowledge value,the related activities and the leading activity in the KM.Capabilities Framework (Leonard-Barton,1995)It considers activities and capacities.The referenced activities are:problems resolution on a shared and creative way;implementation and integration of new tools and methods;experimentation,adoption and absorption of technologies from organisation outsides.About the capacities,it defines it like competitive advantage which was developed by the company during his own life and that can not be easily dropped.Organizational KMFramework(Arthur Andersen and The American Productivity and Quality Center, 1996)They identified six KM processes:creation,identification,collecting, adaptation,application and knowledge sharing.It identified also four boosters whom make easier the work of this processes:leadership,evaluation,culture and technology.Intelligent Organization Framework (Choo,1996)The organisation uses the information in a strategic way to create and understand knowledge,and to take decisions.This model speak about “decision taking”like a process in which the organisation process information to resolve situation uncertainty moments.Four KM Steps Framework(van der Spek and Spijkervet, 1997)Establish four step:conceptualization,included research,classification and modelling of existent knowledge;reflexion(evaluation of conceptualized knowledge);action,when it makes better the acquired knowledge and the retrospection stage,in which they recognize the effect of the action step.Taking this into account,there is not a general approximation about KM commonly accepted,so dispersed and divergent notions are in progress.Some focus on the management of explicit knowledge using technical focus(knowledge shared and transferred from information systems,using networks,etc).Others have directed to intellectual capital(structural capital,human capital);and another approximation,includes issues about relevant knowledge that effects the success of any organization.This is a complementary vision from the two below of knowledge management[25,44].MSEM email for subscription:info@280J.A.Marin-Garcia&E.Zarate-Martinez:A thoretical review of knowledge management and KM have been defined as an art in which information and intellectual assets are transformed in permanent value for the organization and its partners and clients;as a process that using information technologies seeks a synergy combination between data and information treatment and the creative and innovative capacity of human beings in a complex groups of dynamic abilities and know how that are in a permanent change[5,14,48]; and as a management tool focuses in determine,organized,leading,encourages and supervising practises and activities related with knowledge(intangible assets)important to reach the strategy and objectives planned that are valuables to the organization in the way to develop core competences and capacities[37].There are different frameworks that have helped to understand KM[27,37].These frameworks have been identified as descriptive frameworks(characterizing a phenomena’s nature)and prescriptive or specialized frameworks(that shows the methodology follow in KM).Tab.1and2shows some frameworks from the literature,following the classification mentioned above.Those frameworks have in common that characterizes knowledge asset that must be managed,identifies and explain the knowledge activities acting in KM and recognises the factors that affect it[37].Table2.KM prescriptive frameworksIntangible Assets Framework(Sveiby,1997)It assumes tree components as:external structures(relationship between clients, providers,trademarks,company image,etc.),internal structures as patents,concepts, frameworks,administrative systems and organizational culture and employees’competences that point out their skills.Intellectual Capital Framework(Petrash,1996)Involve tree types of organizational resources referring to intellectual capital:human capital(knowledge each person is able to create);organizational capital(knowledge that had been captures and institutionalized within the organization as culture,structures,processes)and the client capital that is the value perception the client have to make business with a goods and services provider.Knowledge Creation Framework(Nonaka y Takeuchi,1995)It introduces two knowledge dimensions(tacit and explicit knowledge)and knowledge creation levels(individual,group,organizational or interorganizational).They Developer a four stages framework:socialization(conversion of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge),externalization(knowledge linkage trough a dialogue or collectivereflection)combination(originating during information processing)and the internalization(organizational knowledge)Knowledge Transfer Framework (Szulanski,1996)It analyzing knowledge transfer barriers,pointed out the good practices.It identifies four stages in knowledge transfer:initiation,implementation,leverage and integration.These stages are affected by transfer ambiguity,lack of motivation or a false perception about irrelevant knowledge as a knowledge source;personal characteristics and context.Knowledge Management Process Framework (KPMG,1997).Includes six phases:knowledge acquisition,indexation,filtration,relation,distribution and application and emphasises tree main factors as top management commitment, assumes KM implications and apply KM to all the organization.Implies working on individual,team and organizational levels as a hole.So it is important to consider structure,strategy,leadership,human resources management,communication and information system and culture.Knowledge Management Participative Framework (Holsapple and Joshi,1998).It is about four phases:Acquisition:taking knowledge from outside the company and transform it in representations than can be use inside the organization.Selection:using organization own knowledge and present it in a right way.Internalization:Modifies organization knowledge assets to convert it in valuables e:manipulates existing knowledge to generate a new knowledge or the externalization of it.In Tab.3we summarize other recent frameworks[2,28]that show the importance of identify the relevant knowledge source and the assumption of KM as an strategy that comes from the company and goes beyond it..The frameworks described here,constitutes the context to facilitate the KM comprehension,showing their characteristic,elements and relationship between they[20].They may help help organizations in the im-plementation of programs that support the new knowledge parading’assumption as a main and very visible resource in the actual society.MSEM email for contribution:submit@International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management,Vol.2(2007)No.4,pp.278-288281Table3.KM prescriptive frameworksRastogi(2000) framework It assumes four stages:(I)identification and classified existing and available knowledge required for organizational strategy,including expert knowledge and employees competences.Storing existing acquired and created knowledge in knowledge repositories.(II)Share knowledge trough an easy access and distribution to the users.(III)Knowledge application to decision making and problem solving. (IV)Creating new knowledge trough R&D,learned lessons,creative thinking and innovation.Integer KM framework (Beijerse,2000).Includes tree main factors to encourage knowledge processes in organizations: strategy,structure and culture.Strategy matches with available and needed knowledge and the gap between them.Structure matches with the knowledge acquisition,development,and capture;and culture will determine how knowledge must be use and shared.Knowledge Flow framework (Heisig,2001)It is compound byfive processes(I)Identify important knowledge for organization strategy.(II)Create,that’s means the capability to learn and communicate making linkages with different matters(III)Store to seek in an right way the information needed and allows employees to access and shared their knowledge.(IV)Distribution by encourages a team spirit to that support knowledge sharing.(V)Application, creating new knowledge from existing and applied knowledge.Building Blocksof Knowledge Management framework(Probst,Raub y Romhardt,2002).This framework assumes two knowledge cycles:(I)Internal Cycle that includes knowledge goals(identification,acquisition and development)and External Cycle related with KM evaluation(distribution,use and preservation)Knowledge Cycle framework(Mc Elroy,2002).Knowledge exists after had been captured,codified and shared.Knowledge creation cycle in two major processes:(I)Knowledge production(individual and group learning, knowledge demand,codification and share)and Knowledge integration(diffusion, training,communication and share).However,as literature says,the application of KM or associated frameworks,are frequently presented in business context,particularly in major companies[17,37],where the focus is targeted to how KM is installed and what kind of tools and methodologies are used to encourage it.On the other hand and unless common its publication,there are an extended cases that shows the great effort major companies,universities and research centers at all levels have carried out to develop.For example,excellent portals(or intranet)as knowledge supporters,so that people share what they know.Also there are publications that resumes a literature review where frameworks,terms,technologies and methodologies of KM are explained[4,16,35];but there is not ref-erences that make a depth study or establish a relationship between KM and other strategic resources of the organization,like for example,the human resources and their management[38].3Team workingConsidering human element in organizations in general,and particularly in business context,had a strong evolution from the Taylor’s conception where people were only a factor that perform their functions according to economic incentive,to actual vision according to people is a major and strategic resource and like so,have an influence in the competitiveness[4,11,30].The economy based on knowledge is changing the view that companies performs their human resources practices.Technology advance,globalization and more specialised work force and awarded respecting time value and market forces,encourages organizations to do more with less[6,7,49]making them redirect their strategies in a permanent way.More organizations are responding to this fact with very new strategies like total quality programs,[49], lean production or involvement/participation management programmes[7,40,60,63]in order to maximize,in those cases,their human capital and adapting to the market demands throughout a group of people that ac-complish complex functions will be impossible to reach working alone[4,11,49,59].However,even there are arguments that try to get into the human resource innovation[65],they are not so extensive as other in manyMSEM email for subscription:info@282J.A.Marin-Garcia&E.Zarate-Martinez:A thoretical review of knowledge management and other organization areas[11,67].In this sense the nature of this change,as some author refers,[66,68]can appreciate in Tab.4:anizational change natureFrom ToEnvironment Variable out knowable Complex and changingStrategic corporate design An assembly of individual whoexecute instructions throughstructures and functionsA knowledge community that drawson the strength of a collective socialmindBoundaries Fixed:the organization has anidentity relationship with itselfFluid:the organization is networkedwith various others at differenttimes,for different purposes.Managerial Focus Functions ProcessesAuthority/Power Hierarchical position,commandand controlProfessional influence,communication,collegialityControl of work Vested n the supervisory process Vested in the individualControl of work outcomes Remains with centralmanagementNegotiated between supervisorsand groups of knowledge workers.Source:D.Hiltrop[11](1995),pp.13.These transition seems to encourage more collective working than those that were developed in an in-dividual way,because,the terms used now are different:collective mind,flow,process,group of workers, etc that support what literature says about organizations that allows teamworking to reach their strategic objectives[54,63,67].We canfind diverse definitions about teamworking in literature,,showing that it is a tool that assists orga-nizational changes,give themflexibility,workers integration,work speed and innovation[54,63,64,67].Never-theless,not all researchers in this area agree with teamworking kindness,saying that this is not a magic potion because their contribution to the organization major goals will depend on the context and the human resources policies have their meanings,[54,61,63,71]and they consider teamworking is more than a fashion and rep-resent a powerful tool for organizations to manage their resources,it is not the definitive way because it needs time,commitment and a specific culture.Sometime these factors in most cases make difficult its implantation.Well thought-out teamworking exists because a group of persons,and its definition may focus from two perspectives:the sociological one,individual centred and his work well-being(tasks execution improvement time and task conditions)or the organization paradigm that conceives teamworking as a management pro-cesses supporting tool and of improvement of the development of the organization.In this sense are very interest in very interesting work makes a review,not only about the sources of teamworking,but the concept evolution throughout time,from its postulation in early50’s to our time,so the organization vision of the concept[54,67].According to Salas et al.[63],teamworking characteristics are related with the member’s skills, aptitudes and attitudes.This can be appreciated in Tab.5.Tranfield et al[67]based on a literature review make a contribution to the teamworking definition,adding the use organizations make of different types of it,as those to support the self develop andflexibility in permanent work team(semi-autonomous or self directed teams);lean teams that are the core structure of companies that work with lean production processes and teams focused on projects,often used in consultancy. Thefinal conclusion they reach pointed out that there is not consistency in the use of these different types of teamworking and that each organization uses them according to its own context.4Relationship between knowledge management and teamworkingSapsed et al.[40],realized a literature review where they found KM and teamworking as a source of competitiveness.Trough teamworking it is possible to establish a mechanism to coordinate the specialized knowledge of a certain quantity of individuals within an organization[16,56];convert personal knowledge(tacit MSEM email for contribution:submit@International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management,Vol.2(2007)No.4,pp.278-288283Table5.Teamworking characteristicsCharacteristics Meaning/comprised skillsFlexible and adaptive behaviors,cognitions and attitudes.General team competencies(knowledge, skills,attitudesFeel free to provide and accept feedback based on monitoring behavior.Mutual performance monitoring,constructive and timely feedback and shared situational awarenessMembers being willing and able to back fellow members up during operations.Back-up behavior(compensatory behavior) and adaptabilityTeamwork involves clear and concisecommunicationClosed-loop communicationCo-ordination of collective interdependent action.Co-ordination,shared mental models and interpersonal relationsLeadership skill that enables the direction, planning and co-ordination of activities Development of shared problem models,clear direction,enabling performance environment,decision making/problem solving,maintaining team coherenceAs all teams are not created equal,contextualfactors as well as the task that is facing the team must be considered when deciding the importance of the various competencies needed within a particular team.Importance of particular team competencies will vary by the nature of the teamSource:Salas et al[63].(2000),pp.352.knowledge)in explicit knowledge that then is embowered in new products,process and services[32].When teamworking is used,organizations can improve their deployment cycle in quality and efficiency in production, mostly if is a complex one[55].The growing importance of complex systems and products we canfind actually requires the integration of disparate technical and professional knowledge.These means that individuals cannot possibly absorb all the requisite knowledge domains for their team’s activities[40].This has forced many organizations to use outsourcing.Teams with high cohesion tend to be more insular,closed to the knowledge and influences outside the team[40].Sometimes team knowledge is not more than the sum of their parts.When the team member’s knowledge is similar or very close,teamworking is more efficient,because a tacit understanding is shared and there is less necessity of explanations or demonstrations.While where the knowledge base of the individuals is different,teamworking becomes slow and complicated[40].On the other hand,there is little literature that establishes metrics about KM and teamworking and their relationship.However,separately we canfind research where they are measured and analyzed,as an isolated issues related to others,basically of economic type.There are a variety of tools for the KM evaluation,diagnosis and results used generally in major compa-nies.Public organizations,as the European Centre of Standardization has created a guide that concentrates the steps companies must follow if they want to have KM.That guide is based on a recommendations and ques-tionnaire based on Heissig[57].The American Productivity&Quality Centre(APQC)and Arthur Andersen developed the Knowledge Management Assessment Tool(KMAT)to help companies to evaluate which of their strengths and opportunities lays on KM.It measure the KM processes itself,the leadership,the cul-ture and technology.On the other hand,Ayestaran[52]analyses the organizational issues that can mediate in KM process within universities.The analysis includes the organizational culture,leadership,organizational structure,human resources management and the system of information and communication.Related to teamworking,Levi and Slem[58]carried out a research using a30items questionnaire and leaded interviews where they evaluated workers’attitudes and beliefs about teamworking in a R&D areas. The questionnaire studied teamworking success,the factors that promote it(from the overall organizations and form human resources)and the ideas about self management.Wright and Edwards[70]accomplished and study using quantitative and qualitative data(they made interviews to shopfloor workers and specialized supervisors and a questionnaire that measured skills,job knowledge and effort)to know if teamworking functions and what were the reasons of its success.Winter and McCalla[69]used Belbin’s taxonomy to determine the individual’MSEM email for subscription:info@284J.A.Marin-Garcia&E.Zarate-Martinez:A thoretical review of knowledge management and skills respecting teamworking when working by projects.Generally most of the research in this area use team types to determine the relationships between job characteristics and the outputs in an teamworking environment.It seems there is a potential researchfield.As we said before,some KM frameworks include teamwork-ing as an important element.So Leonard-Barton[22]framework assumes as an important activity to consider a knowledge based organization,share and creative problem solving;including as an organizational capac-ity,employees knowledge and skills as well as the human resource management system(incentives,training, recognition,etc).Nonaka and Takeguchi[32]in their knowledge creation framework make a distinction be-tween individual and group level in order to facilitate the conversion from tacit to explicit knowledge;and in one of the framework stages(externalization),it is necessary for the articulation of this knowledge throughout a collective reflection.And,Heisig[57]framework outlines that to create knowledge it is necessary to share information,so a team is build it very important.The linkages of these two concepts seem to be done by teamworking characteristic and KM frameworks considering as a processes/tools that supports organizations to obtain its goals.However,the relationship be-tween both terms has been little approached in an explicit way and it seems that there is a general assumption that one is a part of a natural manifestation of the other.Based on this,this paper is aimed to look into the rela-tionship between both tools,considering KM frameworks and teamworking characteristics.This relationship is shown in Fig.1,that leaves from the conceptualization of KM made by several authors[22,32,57]and it’s linked with the teamworking characteristics proposed by Salas et al.[63].Fig.1.Linkages of KM and teamwork frameworkOne way to knowledge transfer is trough share problem solving[22],but individual differences as spe-cialization,cognitive style and preferred tools and methods may states as a barriers to problem solving or as a big opportunity to encourages creativity,so at the same time it can provide a new knowledge.Attempting MSEM email for contribution:submit@International Journal of Management Science and Engineering Management,Vol.2(2007)No.4,pp.278-288285 to this,the relationship with teamworking characteristics may be explained from the perspective of diverse knowledge and the team skills,methods and tools,in which it’s necessary to favour a context that encourage people to accept different points of view,even if it is not agreement,without favouring the division of the group.The specialization and the different cognitive styles found in a team need a strong leadership able to mediate over the interactions between opposites,not only to diminish the tension,but to lead the energies to make collaboration between specialities.For if we present the framework,and outlines that a team where problems are solve in a share way,there may exist the following characteristics:·Specific competences,according to context·Visible leadership that encourages a positive interaction environment·Clear communication·Adaptable andflexible attitudes and behaviours.Another part of the linkage we want to outline between KM and teamworking is Nonaka and Takeguchi knowledge creation framework[32].As we stated previously,to this author,knowledge is a dynamic element that is created trough social interactions between people and organization[62];and it is the collective reflection what facilitates knowledge,in it beginnings tacit becomes into explicit form supporting it transfer.The circle of knowledge creation proposed has four steps and according with Nonaka and Takeguchi[32]three of those have been studied from different organizational theory perspectives:socialization from group process theory; combination,from organization culture and internalization from organizational learning.However,external-ization has been little approached.In fact in this step,knowledge conversion(new explicit knowledge creation from existing tacit knowledge)is activated trough dialogue or collective reflection,because during people interaction process it may have perception and understanding differences.Likewise,the individualism is tran-scending to stables a commitment more general,making part of a group.The sum of particular intentions is now part of the team mind[62].Knowledge needs a context to be created,shared and used.Schermerhum et al.[64]argues that teamworking occurs when team members work together using their knowledge and skills to reach certain goals.So it may be said that those people,working together share a context where they interact to accomplish their goals,so our framework outlines that the following elements may be established:·Adaptable andflexible attitudes and behaviors.·Support to the team members during task development.·Clear communication·Interdependent coordination·Specific competences,according to the interaction contextThe European guide to good practices in KM[51]picks Heisig’s knowledgeflows framework[57]that is formed byfive main knowledge activities that must be aligned or integrated into the organization process and activities.The activities the framework refers are about knowledge identification,new knowledge creation, knowledge store,share and use.Each of this stages have to be balanced according with the organization specifications,so they cannot be treated on an isolated way or by pair of activities.New knowledge creation can exist at individual or group level(team)and it must be a social interaction result and it has to be integrated within the organization supported by other activities like sorting,organization, categorization,updating and beflexible to modify the knowledge companies has attending to the in-or-out circumstances.For our research,the step we analyzed is referred to knowledge exchange.When knowledge is shared by artifacts,it is name stock focus.But the major part of knowledge may be transfered from person to person by collaboration[57].This point of view may be supported by tools and methodologies that facilitate the knowl-edge transfer,like intranets/data bases,etc,but if it is not a personal bias to accept knowledge from others, it will be difficult to use/re-use.This may mean that some personal competences are required for knowledge exchange.So theseflow focus support our framework in sense of people that interact with others to knowledge transfer have a bias to·Adaptable andflexible attitudes and behaviors.·Support to the team members during task development·Clear communicationMSEM email for subscription:info@。

feature of literature reviewA literature review is a critical analysis of existing research on a particular topic. It involves the examination and evaluation of previous studies, theories, and concepts related to the subject under investigation. The following are some key features of a literature review:1. Comprehensive coverage: A literature review provides an overview of the existing body of knowledge on a specific topic. It encompasses various sources such as academic journals, books, conference proceedings, and government reports. The review should cover both seminal and recent works to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the subject.2. Critical evaluation: Unlike a simple summary, a literature review goes beyond describing the research; it critically evaluates and synthesizes the information. The reviewer assesses the strengths, weaknesses, and methodological limitations of each study, highlighting areas of agreement and controversy within the literature.3. Thematic organization: Literature reviews often organize the reviewed literature around themes or topics. This structuring helps to identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research, enabling the reviewer to develop a coherent and cohesive analysis.4. Time frame: The literature review may focus on a specific time period, depending on the research question. It can cover the historical development of a topic or concentrate on recent advancements to provide context and identify areas for further investigation.5. Reference to primary sources: A literature review cites and references the original studies and sources it draws upon. This demonstrates the reviewer's engagement with the literature and allows readers to access the cited materials for further reading and verification.6. Identification of gaps and recommendations: By analyzing the literature, a literature review identifies gaps in the existing knowledge or areas where furtherresearch is needed. It may suggest directions for future studies or recommend methodological improvements.In summary, a literature review is a comprehensive, critical examination of existing research that provides an understanding of the current state of knowledge on a particular topic. It offers insights, identifies gaps, and informs the development of new research in the field.。

学科述评怎样写范文## How to Write a Literature Review.A literature review is a critical analysis of a body of research on a specific topic. It provides a comprehensive overview of the existing knowledge on the topic,identifying key themes, theories, and gaps in the literature. Writing a literature review involves several steps:Identifying a research question or topic.Searching and gathering relevant sources.Critically evaluating sources.Organizing and synthesizing information.Writing and revising the review.Building Blocks of a Literature Review.1. Introduction: Introduce the topic of the review and state the research question or problem.2. Body Paragraphs: Discuss the existing literature on the topic, organizing it into themes or subtopics. Critically evaluate the sources, identifying their strengths and weaknesses.3. Discussion: Synthesize the findings of theliterature review, identifying key themes, theories, and gaps in the literature. Discuss the implications of the findings and suggest directions for future research.4. Conclusion: Summarize the main points of the literature review and restate the research question or problem.Tips for Writing a Literature Review.1. Be clear and concise: Write in a clear and concisestyle, using precise language and avoiding jargon.2. Be critical: Critically evaluate the sources you use, identifying their strengths and weaknesses.3. Be objective: Present the information in anobjective and unbiased manner, avoiding personal opinionsor biases.4. Cite your sources: Properly cite all sources used in the literature review using a consistent citation style.5. Proofread carefully: Proofread your literaturereview carefully to ensure it is free of errors.## 如何撰写学科述评。

竭诚为您提供优质文档/双击可除literature,review,模板篇一:打印版literaturereview模板nuclearRadiationanditslong-termhealtheffect(yourtitle)thereisaconstantcontroversyastotheapplicationofnucl earpowerandrisksfromnuclearradiationeversincetheche rnobyldisaster.especiallythereleaseofsubstantialamo untsofradiationintotheatmospherefromjapan’sFukushimadaiichinuclearpowerplantin20xxhastriggere dthewidespreadfearandconcernsoverrisksofradiationle aks,radiationexposure,andtheirimpactonpeople’shealth.thecommonsensicalandintuitiveresponseofthep ublicisthatnuclearradiationismostlikelytocauseacanc erorgeneticdiseases.manyresearchers,however,assured thepublicthatthereisnosubstantialdangerasassumed,andnuclearpowerisnotasfearfulormenacingasitseemstobe. cohen(20xx),blumenthal(20xx)andbai(20xx),forexample ,citednumericalevidenceandresortedtoscientificfacts toillustratethatacertainlevelofnuclearradiationrisk swon’tposerealdangerifhandledproperlywiththecurrenttechn ologyavailableorbyfollowingtheprescribedrules.theyd oadmitthepossibilityofradiationinitiatingcertainkin dsofdiseases,though.onlyexposuretohighdosesofradiat ionorlong-termlowdoseexposurecouldleadtoacutehealth problems(bai20xx).nevertheless,noteveryoneagrees.co rnelio(20xx),ontheotherhand,holdsthatnuclearradiati onismostlikelytothreatenpeople’shealthbycontaminatingmilk,vegetables,andrainwater. theliteratureontherelationshipbetweenradiationandhe althlargelyfocusedonthemanageabilityofnuclearrisksa ndplayeddownthedamagethatnuclearradiationislikelyto cause.theresearchesgenerallytookadetourastowhetherthereis anysolidevidencetobearoutthelong-termhealthimpactof nuclearradiation.thereneedstobemorewell-groundedstudiesonthecorrelationbetweenradiationandhealth,andon thepossiblelong-termhealtheffectsinordertoaddressth econcernsofthegeneralpublic.besides,wealsoneedtoans werquestionslike “whyisthereadisparitybetweenthecommonsensicalfeeli ngofthepublicandtheexplicationofferedbyexpertsconce rningnuclearradiationandhealth”“,arescientistsbiasedandusethefactsandstatisticsto theirfavor”and“istherealong-termnegativehealthimpactifonetakesmo deratedosesofnuclearcontaminatedfoodoveralongperiod”题目小二字体小四如果是400字数刚好,最下面还有一点空间写下名字。