MATERNAL INFECTION AND IMMUNE INVOLVEMENT IN AUTISM

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:265.50 KB

- 文档页数:10

Microbiota Modulate Behavioral and Physiological Abnormalities Associatedwith Neurodevelopmental DisordersElaine Y.Hsiao,1,2,*Sara W.McBride,1Sophia Hsien,1Gil Sharon,1Embriette R.Hyde,3Tyler McCue,3Julian A.Codelli,2 Janet Chow,1Sarah E.Reisman,2Joseph F.Petrosino,3Paul H.Patterson,1,4,*and Sarkis K.Mazmanian1,4,*1Division of Biology and Biological Engineering,California Institute of Technology,Pasadena,CA91125,USA2Division of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering,California Institute of Technology,Pasadena,CA91125,USA3Alkek Center for Metagenomics and Microbiome Research,Baylor College of Medicine,Houston,TX77030,USA4These authors contributed equally to this work*Correspondence:ehsiao@(E.Y.H.),php@(P.H.P.),sarkis@(S.K.M.)/10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.024SUMMARYNeurodevelopmental disorders,including autism spectrum disorder(ASD),are defined by core behav-ioral impairments;however,subsets of individuals display a spectrum of gastrointestinal(GI)abnormal-ities.We demonstrate GI barrier defects and micro-biota alterations in the maternal immune activation (MIA)mouse model that is known to display features of ASD.Oral treatment of MIA offspring with the hu-man commensal Bacteroides fragilis corrects gut permeability,alters microbial composition,and ame-liorates defects in communicative,stereotypic,anxi-ety-like and sensorimotor behaviors.MIA offspring display an altered serum metabolomic profile,and B.fragilis modulates levels of several metabolites. Treating naive mice with a metabolite that is increased by MIA and restored by B.fragilis causes certain behavioral abnormalities,suggesting that gut bacterial effects on the host metabolome impact behavior.Taken together,thesefindings support a gut-microbiome-brain connection in a mouse model of ASD and identify a potential probiotic therapy for GI and particular behavioral symptoms in human neurodevelopmental disorders.INTRODUCTIONNeurodevelopmental disorders are characterized by impaired brain development and behavioral,cognitive,and/or physical abnormalities.Several share behavioral abnormalities in socia-bility,communication,and/or compulsive activity.Most recog-nized in this regard is autism spectrum disorder(ASD),a serious neurodevelopmental condition that is diagnosed based on the presence and severity of stereotypic behavior and deficits in lan-guage and social interaction.The reported incidence of ASD has rapidly increased to1in88births in the United States as of2008(Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Sur-veillance Year2008Principal Investigators and CDC,2012),rep-resenting a significant medical and social problem.However, therapies for treating core symptoms of autism are limited. Much research on ASD has focused on genetic,behavioral, and neurological aspects of disease,though the contributions of environmental risk factors(Hallmayer et al.,2011),immune dysregulation(Onore et al.,2012),and additional peripheral dis-ruptions(Kohane et al.,2012)in the pathogenesis of ASD have gained significant attention.Among several comorbidities in ASD,gastrointestinal(GI) distress is of particular interest,given its reported prevalence (Buie et al.,2010;Coury et al.,2012)and correlation with symp-tom severity(Adams et al.,2011).While the standardized diag-nosis of GI symptoms in ASD is yet to be clearly defined,clinical as well as epidemiological studies have reported abnormalities such as altered GI motility and increased intestinal permeability (Boukthir et al.,2010;D’Eufemia et al.,1996;de Magistris et al.,2010).Moreover,a recent multicenter study of over 14,000ASD individuals reveals a higher prevalence of inflamma-tory bowel disease(IBD)and other GI disorders in ASD patients compared to controls(Kohane et al.,2012).GI abnormalities are also reported in other neurological diseases,including Rett syn-drome(Motil et al.,2012),cerebral palsy(Campanozzi et al., 2007),and major depression(Graff et al.,2009).The causes of these GI problems remain unclear,but one possibility is that they may be linked to gut bacteria.Indeed,dysbiosis of the microbiota is implicated in the patho-genesis of several human disorders,including IBD,obesity,and cardiovascular disease(Blumberg and Powrie,2012),and several studies report altered composition of the intestinal mi-crobiota in ASD(Adams et al.,2011;Finegold et al.,2010;Fine-gold et al.,2012;Kang et al.,2013;Parracho et al.,2005;Williams et al.,2011;Williams et al.,2012).Commensal bacteria affect a variety of complex behaviors,including social,emotional,and anxiety-like behaviors,and contribute to brain development and function in mice(Collins et al.,2012;Cryan and Dinan, 2012)and humans(Tillisch et al.,2013).Long-range interactions between the gut microbiota and brain underlie the ability of microbe-based therapies to treat symptoms of multiplesclerosis Cell155,1451–1463,December19,2013ª2013Elsevier Inc.1451and depression in mice (Bravo et al.,2011;Ochoa-Repa´raz et al.,2010),and the reported efficacy of probiotics in treating emotional symptoms of chronic fatigue syndrome and psycho-logical distress in humans (Messaoudi et al.,2011;Rao et al.,2009).Based on the emerging appreciation of a gut-microbiome-brain connection,we asked whether modeling some of the behavioral features of ASD in a mouse model also causes GI abnormalities.Several mouse models of genetic and/or environ-mental risk factors are used to study ASD.We utilize the maternal immune activation (MIA)model,which is based on large epide-miological studies linking maternal infection to increased autismrisk in the offspring (Atlado´ttir et al.,2010;Gorrindo et al.,2012).A number of studies link increased ASD risk to familial autoim-mune disease (Atlado´ttir et al.,2009;Comi et al.,1999)and elevated levels of inflammatory factors in the maternal blood,placenta,and amniotic fluid (Abdallah et al.,2013;Brown et al.,2013;Croen et al.,2008).Modeling MIA in mice by injecting preg-nant dams with the viral mimic poly(I:C)yields offspring that exhibit the core communicative,social,and stereotyped impair-ments relevant to ASD,as well as a common autism neuro-pathology—a localized deficiency in cerebellar Purkinje cells (Malkova et al.,2012;Shi et al.,2009).Furthermore,pregnant monkeys exposed to poly(I:C)yield offspring with symptoms of ASD (Bauman et al.,2013).Although several environmental and genetic risk factors for ASD have been investigated in pre-clinical models,GI abnormalities have not been reported.We show herein that offspring of MIA mice,which display behavioral abnormalities,have defects in intestinal integrity and alterations in the composition of the commensal microbiota that are analo-gous to features reported in human ASD.To explore the potential contribution of GI complications to these symptoms,weF I T C i n t e n s i t y /m l s e r u m (f o l d c h a n g e )Adult (8-10 weeks)F I T C i n t e n s i t y /m l s e r u mAdolescent (3 weeks)S O C S N O S I L 1T N F I L 1I L m R N A /A C T B (f o l d c h a n g e )*S PF G F -b a s iI F N -I L -1I L -I L -I L -I L -12p 40/p 7I L -1I P -1K M C P -M I M I P -1T N F -V E G 300350400450p g /m g p r o t e i nT J P T J P O C L C L D N C L D N C L D N C L D N C L D N C L D N 1C L D N 1m R N A /A C T B (f o l d c h a n g e )S PABCDFigure 1.MIA Offspring Exhibit GI Barrier Defects and Abnormal Expression of Tight Junction Components and Cytokines(A)Intestinal permeability assay,measuring FITC intensity in serum after oral gavage of FITC-dextran.Dextran sodium sulfate (DSS):n =6,S (saline+vehicle):adult n =16;adolescent n =4,P (poly(I:C)+vehicle):adult n =17;adolescent n =4.Data are normalized to saline controls.(B)Colon expression of tight junction components relative to b -actin.Data for each gene are normalized to saline controls.n =8/group.(C)Colon expression of cytokines and inflamma-tory markers relative to b -actin.Data for each gene are normalized to saline controls.n =6–21/group.(D)Colon protein levels of cytokines and chemo-kines relative to total protein content.n =10/group.For each experiment,data were collected simul-taneously for poly(I:C)+B.fragilis treatment group (See Figure 3).See also Figure S1.examine whether treatment with the gut bacterium Bacteroides fragilis ,demon-strated to correct GI pathology in mouse models of colitis (Mazmanian et al.,2008)and to protect against neuroinflam-mation in mouse models of multiple sclerosis (Ochoa-Repa´raz et al.,2010),impacts ASD-related GI and/or behavioral abnormalities in MIA offspring.Our study reflects a mechanistic investigation of how alterations in the commensal microbiota impact behavioral abnormalities in a mouse model of neurodeve-lopmental disease.Our findings suggest that targeting the microbiome may represent an approach for treating subsets of individuals with behavioral disorders,such as ASD,and comor-bid GI dysfunction.RESULTSOffspring of Immune-Activated Mothers Exhibit GI Symptoms of Human ASDSubsets of ASD children are reported to display GI abnormal-ities,including increased intestinal permeability or ‘‘leaky gut’’(D’Eufemia et al.,1996;de Magistris et al.,2010;Ibrahim et al.,2009).We find that adult MIA offspring,which exhibit a number of behavioral and neuropathological symptoms of ASD (Malkova et al.,2012),also have a significant deficit in intestinal barrier integrity,as reflected by increased translocation of FITC-dextran across the intestinal epithelium,into the circulation (Figure 1A,left).This MIA-associated increase in intestinal permeability is similar to that of mice treated with dextran sodium sulfate (DSS),which induces experimental colitis (Figure 1A,left).Defi-cits in intestinal integrity are detectable in 3-week-old MIA offspring (Figure 1A,right),indicating that the abnormality is established during early life.Consistent with the leaky gut phenotype,colons from adult MIA offspring contain decreased gene expression of TJP1,TJP2,OCLN ,and CLDN8and increased expression of CLDN15(Figure 1B).Deficient expres-sion of TJP1is also observed in small intestines of adult MIA1452Cell 155,1451–1463,December 19,2013ª2013Elsevier Inc.offspring(Figure S1A available online),demonstrating a wide-spread defect in intestinal barrier integrity.Gut permeability is commonly associated with an altered immune response(Turner,2009).Accordingly,colons from adult MIA offspring display increased levels of interleukin-6(IL-6) mRNA and protein(Figures1C and1D)and decreased levels of the cytokines/chemokines IL-12p40/p70and MIP-1a(Fig-ure1D).Small intestines from MIA offspring also exhibit altered cytokine/chemokine profiles(Figure S1C).Changes in intestinal cytokines are not accompanied by overt GI pathology,as as-sessed by histological examination of gross epithelial morphology from hematoxylin-and eosin-stained sections (data not shown).Overall,wefind that adult offspring of im-mune-activated mothers exhibit increased gut permeability and abnormal intestinal cytokine profiles.MIA Offspring Display Dysbiosis of the Gut Microbiota Abnormalities related to the microbiota have been identified in ASD individuals,including disrupted community composition (Adams et al.,2011;Finegold et al.,2010;Finegold et al., 2012;Parracho et al.,2005;Williams et al.,2011;Williams et al.,2012),although it is important to note that a well-defined ASD-associated microbial signature is lacking thus far.To eval-uate whether MIA induces microbiota alterations,we surveyed the fecal bacterial population by16S rRNA gene sequencing of samples isolated from adult MIA or control offspring.Alpha di-versity,i.e.,species richness and evenness,did not differ signif-icantly between control and MIA offspring,as measured by several indices(Figures S2A and S2B).In contrast,unweighted UniFrac analysis,which measures the degree of phylogenetic similarity between microbial communities,reveals a strong ef-fect of MIA on the gut microbiota of adult offspring(Figure2). MIA samples cluster distinctly from controls by principal coordi-nate analysis(PCoA)and differ significantly in composition(Ta-ble S3,with ANOSIM R=0.2829,p=0.0030),indicating robust differences in the membership of gut bacteria between MIA offspring and controls(Figure2A).The effect of MIA on altering the gut microbiota is further evident when sequences from the classes Clostridia and Bacteroidia,which account for approxi-mately90.1%of total reads,are exclusively examined by PCoA(R=0.2331,p=0.0070;Figure2B),but not when Clostri-dia and Bacteroidia sequences are specifically excluded from PCoA of all other bacterial classes(R=0.1051,p=0.0700;Fig-ure2C).This indicates that changes in the diversity of Clostridia and Bacteroidia operational taxonomic units(OTUs)are the pri-mary drivers of gut microbiota differences between MIA offspring and controls.Sixty-seven of the1,474OTUs detected across any of the samples discriminate between treatment groups,including those assigned to the bacterial families Lachnospiraceae, Ruminococcaceae,Erysipelotrichaceae,Alcaligenaceae,Por-phyromonadaceae,Prevotellaceae,Rikenellaceae,and un-classified Bacteroidales(Figure2D and Table S1).Of these67 discriminatory OTUs(relative abundance:13.3%±1.65%con-trol,15.93%±0.62%MIA),19are more abundant in the control samples and48are more abundant in MIA samples.Consistent with the PCoA results(Figures2A–2C),the majority of OTUs that discriminate MIA offspring from controls are assigned to theclasses Bacteroidia(45/67OTUs or67.2%;12.02%±1.62% control,13.48%±0.75%MIA)and Clostridia(14/67OTUs or 20.9%;1.00%±0.25%control,1.58%±0.34%MIA).Interest-ingly,Porphyromonadaceae,Prevotellaceae,unclassified Bac-teriodales(36/45discriminatory Bacteroidial OTUs or80%;4.46%±0.66%control,11.58%±0.86%MIA),and Lachnospir-iceae(8/14discriminatory Clostridial OTUs or57%;0.28%±0.06%control,1.13%±0.26%MIA)were more abundant in MIA offspring.Conversely,Ruminococcaceae(2OTUs),Erysipe-lotrichaceae(2OTUs),and the beta Proteobacteria family Alca-ligenaceae(2OTUs)were more abundant in control offspring (Figure2D and Table S1;0.95%±0.31%control,0.05%±0.01%MIA).This suggests that specific Lachnospiraceae,along with other Bacteroidial species,may play a role in MIA pathogen-esis,while other taxa may be protective.Importantly,there is no significant difference in the overall relative abundance of Clostridia(13.63%± 2.54%versus14.44%± 2.84%;p= 0.8340)and Bacteroidia(76.25%±3.22%versus76.22%±3.46%;p=0.9943)between MIA offspring and controls(Fig-ure2E,left),indicating that alterations in the membership of Clostridial and Bacteroidial OTUs drive major changes in the gut microbiota between experimental groups.Overall,wefind that MIA leads to dysbiosis of the gut microbiota,driven primarily by alterations in specific OTUs of the bacterial classes Clostridia and Bacteroidia.Changes in OTUs classified as Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae of the order Clostridiales parallel select reports of increased Clos-tridium species in the feces of subjects with ASD(Finegold et al.,2012).Altogether,modeling MIA in mice induces not only behavioral and neuropathological features of ASD(Malkova et al.,2012;Shi et al.,2009)but also microbiome changes as described in subsets of ASD individuals.Bacteroides fragilis Improves Gut Barrier Integrity in MIA OffspringGut microbes play an important role in the development,mainte-nance and repair of the intestinal epithelium(Turner,2009).To determine whether targeting the gut microbiota could impact MIA-associated GI abnormalities,we treated mice with the human commensal B.fragilis at weaning,and tested for GI abnormalities at8weeks of age.B.fragilis has previously been shown to ameliorate experimental colitis(Mazmanian et al., 2008;Round and Mazmanian,2010).Remarkably,B.fragilis treatment corrects intestinal permeability in MIA offspring(Fig-ure3A).In addition,B.fragilis treatment ameliorates MIA-associ-ated changes in expression of CLDNs8and15,but not TJP1, TJP2,or OCLN(Figure3B).Similar changes are observed in pro-tein levels of CLDNs8and15in the colon,with restoration by B.fragilis treatment(Figures3C and3D).No effects of B.fragilis on tight junction expression are observed in the small intestine(Figure S1B),consistent with the fact that Bacteroides species are predominantly found in the colon.Finally,the pres-ence of GI defects prior to probiotic administration(Figure1A, right)suggests that B.fragilis may treat,rather than prevent, this pathology in MIA offspring.B.fragilis treatment also restores MIA-associated increases in colon IL-6mRNA and protein levels(Figures3E and3F).Levels of other cytokines are altered in both colons and small intestines of Cell155,1451–1463,December19,2013ª2013Elsevier Inc.1453MIA offspring (Figures 1D and S1C),but these are not affected by B.fragilis treatment,revealing specificity for IL-6.We further find that recombinant IL-6treatment can modulate colon levels of both CLDN 8and 15in vivo and in in vitro colon organ cultures (data not shown),suggesting that B.fragilis -mediated restora-tion of colonic IL-6levels could underlie its effects on gut permeability.Collectively,these findings demonstrate that B.fragilis treatment of MIA offspring improves defects in GIbarrier integrity and corrects alterations in tight junction and cytokine expression.B.fragilis Treatment Restores Specific Microbiota Changes in MIA OffspringThe finding that B.fragilis ameliorates GI defects in MIA offspring prompted us to examine its effects on the intestinal microbiota.No significant differences are observedfollowingFigure 2.MIA Offspring Exhibit Dysbiosis of the Intestinal Microbiota(A)Unweighted UniFrac-based 3D PCoA plot based on all OTUs from feces of adult saline+vehicle (S)and poly(I:C)+vehicle (P)offspring.(B)Unweighted UniFrac-based 3D PCoA plot based on subsampling of Clostridia and Bacteroidia OTUs (2003reads per sample).(C)Unweighted UniFrac-based 3D PCoA plot based on subsampling of OTUs remaining after subtraction of Clostridia and Bacteroidia OTUs (47reads per sample).(D)Relative abundance of unique OTUs of the gut microbiota (bottom,x axis)for individual biological replicates (right,y axis),where red hues denote increasing relative abundance of a unique OTU.(E)Mean relative abundance of OTUs classified at the class level for the most (left)and least (right)abundant taxa.n =10/group.Data were simultaneously collected and analyzed for poly(I:C)+B.fragilis treatment group (See Figure 4).See also Figure S2and Table S1.1454Cell 155,1451–1463,December 19,2013ª2013Elsevier Inc.B.fragilis treatment of MIA offspring by PCoA (ANOSIM R =0.0060p =0.4470;Table S3),in microbiota richness (PD:p =0.2980,Observed Species:p =0.5440)and evenness (Gini:p =0.6110,Simpson Evenness:p =0.5600;Figures 4A,S2A and S2B),or in relative abundance at the class level (Fig-ure S2C).However,evaluation of key OTUs that discriminate adult MIA offspring from controls reveals that B.fragilis treatment significantly alters levels of 35OTUs (Table S2).Specifically,MIA offspring treated with B.fragilis display significant restoration in the relative abundance of 6out of the 67OTUs found to discriminate MIA from control offspring (Figure 4B and Table S2),which are taxonomically assigned as unclassified Bacteroidia and Clostridia of the family Lachnospiraceae (Figure 4B and Table S2).Notably,these alterations occur in the absence of persistent colonization of B.fragilis ,which remains undetectable in fecal and cecal samples isolated from treated MIA offspring (Figures S2D and S2E).Phylogenetic reconstruction of the OTUs that are altered by MIA and restored by B.fragilis treatment reveals that the Bacteroidia OTUs cluster together into a monophyletic group and the Lachnospiraceae OTUs cluster into two monophyletic groups (Figure 4C).This result suggests that,although treatment of MIA offspring with B.fragilis may not lead to persistent colonization,this probiotic corrects the relative abundance of specific groups of related microbes of the Lachnospiraceae family as well as unclassified Bacteriodales.Altogether,we demonstrate that treatment of MIA offspring with B.fragilis ameliorates particular MIA-associ-ated alterations in the commensalmicrobiota.C LD N 8/T U B B (f o l d c h a n g e )F I T C i n t e n s i t y /m l s e r u m (f o l d c h a n g e )*****CLDN8: -tubulin: CLDN15:-tubulin:I L 6 m R N A /A C T B (f o l d c h a n g e )**CLDN8T J PT J P O C L C L D N C L D N 1m R N A /A C T B (f o l d c h a n g e )n.s.n.s.*****P P+BFS I L -I L -12p 40/p 7I P -1M I M I P -1p g /m g p r o t e i n (f o l dc h a ng e )C LD N 15/T U B B (f o l d c h a n g e )ABCDEFFigure 3.B.fragilis Treatment Corrects GI Deficits in MIA Offspring(A)Intestinal permeability assay,measuring FITC intensity in serum after oral gavage of FITC-dextran.Data are normalized to saline controls.Data for DSS,saline +vehicle (S)and poly(I:C)+vehicle (P)are as in Figure 1.poly(I:C)+B.fragilis (P+BF):n =9/group.(B)Colon expression of tight junction components relative to b -actin.Data for each gene are normalized saline controls.Data for S and P are as in Figure 1.Asterisks directly above bars indicate significance compared to saline control (normalized to 1,as denoted by the black line),whereas asterisks at the top of the graph denote statistical significance between P and P+BF groups.n =8/group.(C)Immunofluorescence staining for claudin 8.Representative images for n =5.(D)Colon protein levels of claudin 8(left)and claudin 15(right).Representative signals are depicted below.Data are normalized to signal intensity in saline controls.n =3/group.(E)Colon expression of IL-6relative to b -actin.Data are normalized to saline controls.Data for S and P are as in Figure 1.P+BF:n =3/group.(F)Colon protein levels of cytokines and chemokines relative to total protein content.Data are normalized to saline controls.Data for S and P are as in Figure 1.n =10/group.See also Figure S1.Cell 155,1451–1463,December 19,2013ª2013Elsevier Inc.1455B.fragilis Treatment Corrects ASD-Related Behavioral AbnormalitiesStudies suggest that GI issues can contribute to the develop-ment,persistence,and/or severity of symptoms seen in ASD and related neurodevelopmental disorders (Buie et al.,2010;Coury et al.,2012).To explore the potential impact of GI dysfunc-tion on core ASD behavioral abnormalities,we tested whetherB.fragilis treatment impacts anxiety-like,sensorimotor,repeti-tive,communicative,and social behavior in MIA offspring.We replicated previous findings that adult MIA offspring display several core behavioral features of ASD (Malkova et al.,2012).Open field exploration involves mapping an animal’s movement in an open arena to measure locomotion and anxiety (Bourin et al.,2007).MIA offspring display decreased entries and time0.2LachnospiraceaeBFigure 4.B.fragilis Treatment Alters the Intestinal Microbiota and Corrects Species-Level Abnormalities in MIA Offspring(A)Unweighted UniFrac-based 3D PCoA plot based on all OTUs.Data for saline (S)and poly(I:C)(P)are as in Figure 2.(B)Relative abundance of key OTUs of the family Lachnospiraceae (top)and order Bacteroidales (bottom)that are significantly altered by MIA and restored by B.fragilis treatment.(C)Phylogenetic tree based on nearest-neighbor analysis of 16S rRNA gene sequences for key OTUs presented in (B).Red clades indicate OTUs of the family Lachnospiraceae and green clades indicate OTUs of the order Bacteriodales.Purple taxa indicate OTUs that are significantly elevated in P and corrected by B.fragilis (BF)treatment.n =10/group.See also Figure S2and Table S2.1456Cell 155,1451–1463,December 19,2013ª2013Elsevier Inc.spent in the center of the arena,which is indicative of anxiety-like behavior (Figure 5A;compare saline [S]to poly(I:C)[P]).The prepulse inhibition (PPI)task measures the ability of an animal to inhibit its startle in response to an acoustic tone (‘‘pulse’’)when it is preceded by a lower-intensity stimulus (‘‘prepulse’’).Deficiencies in PPI are a measure of impaired sensorimotor gating and are observed in several neurodevelopmental disor-ders,including autism (Perry et al.,2007).MIA offspring exhibit decreased PPI in response to 5or 15db prepulses (Figure 5B).The marble burying test measures the propensity of mice to engage repetitively in a natural digging behavior that is not confounded by anxiety (Thomas et al.,2009).MIA offspring display increased stereotyped marble burying compared tocontrols (Figure 5C).Ultrasonic vocalizations are used to mea-sure communication by mice,wherein calls of varying types and motifs are produced in different social paradigms (Grimsley et al.,2011).MIA offspring exhibit deficits in communication,as indicated by reduced number and duration of ultrasonic vocali-zations produced in response to a social encounter (Figure 5D).Finally,the three-chamber social test is used to measure ASD-P P I (%)5 db 15 dbS P P+BF**S P P+BF 0255075D u r a t i o n p e r c a l l (m s )****T o t a l c a l l d u r a t i o n (s )****S P P+BF200400600T o t a l n u m b e r o f c a l l s**S P P+BF ****S PP+BF 010203040D i s t a n c e (m )S o c i a l p r e f e r e n c e :c h a m b e r d u r a t i o n (%)***S o c i a b i l i t y :c h a m b e r d u r a t i o n (%)*Anxiety and locomotion: Open field exploration Sensorimotor gating: Pre-pulse inhibitionStereotyped behavior: Marble burying Communication:Ultrasonic vocalizationsSocial Interaction:SociabilitySocial Interaction: Social preference BDEF Figure 5.B.fragilis Treatment Ameliorates Autism-Related Behavioral Abnormalities in MIA Offspring(A)Anxiety-like and locomotor behavior in the open field exploration assay.n =35–75/group.(B)Sensorimotor gating in the PPI assay.n =35–75/group.(C)Repetitive marble burying assay.n =16–45/group.(D)Ultrasonic vocalizations produced by adult male mice during social encounter.n =10/group.S =saline+vehicle,p =poly(I:C)+vehicle,P+BF =poly(I:C)+B.fragilis .Data were collected simul-taneously for poly(I:C)+B.fragilis D PSA and poly(I:C)+B.thetaiotaomicron treatment groups (See also Figures S3and S4).related impairments in social interaction (Silverman et al.,2010).MIA offspringexhibit deficits in both sociability,or pref-erence to interact with a novel mouseover a novel object,and social preference (social novelty),or preference to interact with an unfamiliar versus a familiar mouse(Figures 5E and 5F).Altogether,MIA offspring demonstrate a number of be-havioral abnormalities associated with ASD as well as others such as anxiety and deficient sensorimotor gating.Remarkably,oral treatment with B.fragilis ameliorates many of these be-haviors.B.fragilis -treated MIA offspring do not exhibit anxiety-like behavior in theopen field (Figure 5A;compare poly(I:C)[P]to poly(I:C)+B.fragilis [P+BF]),as shown by restoration in the number of center entries and duration of time spent in the center of the arena.B.fragilis im-proves sensorimotor gating in MIA offspring,as indicated by increased combined PPI in response to 5and 15db prepulses (Figure 5B),with no significant effect on the intensity of startle to the acoustic stimulus (data not shown).B.fragilis -treated mice also exhibit decreased levels of stereotyped marble burying and restored communicative behavior (Figures 5C and 5D).Interestingly,B.fragilis raises the duration per call by MIA offspring to levels exceeding those observed in saline controls (Figure 5D),suggesting that despite normalization of the pro-pensity to communicate (number of calls),there is a qualitative difference in the types of calls generated with enrichment of longer syllables.Although B.fragilis -treated MIA offspring exhibit improved communicative,repetitive,anxiety-like,and sensorimotor behavior,they retain deficits in sociability and social preference (Figure 5E).Selective amelioration of ASD-related behaviors is also seen with risperidone treatment of CNTNAP2knockoutmice,a genetic mouse model for ASD (Pen˜agarikano et al.,2011),wherein communicative and repetitive,but not social,behavior is corrected.These data suggest that there may beCell 155,1451–1463,December 19,2013ª2013Elsevier Inc.1457。

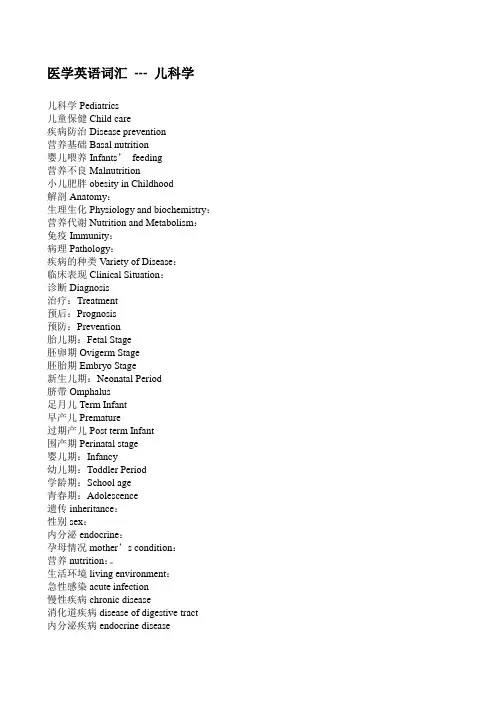

医学英语词汇--- 儿科学儿科学Pediatrics儿童保健Child care疾病防治Disease prevention营养基础Basal nutrition婴儿喂养Infants’feeding营养不良Malnutrition小儿肥胖obesity in Childhood解剖Anatomy:生理生化Physiology and biochemistry:营养代谢Nutrition and Metabolism:免疫Immunity:病理Pathology:疾病的种类Variety of Disease:临床表现Clinical Situation:诊断Diagnosis治疗:Treatment预后:Prognosis预防:Prevention胎儿期:Fetal Stage胚卵期Ovigerm Stage胚胎期Embryo Stage新生儿期:Neonatal Period脐带Omphalus足月儿Term Infant早产儿Premature过期产儿Post term Infant围产期Perinatal stage婴儿期:Infancy幼儿期:Toddler Period学龄期:School age青春期:Adolescence遗传inheritance:性别sex:内分泌endocrine:孕母情况mother’s condition:营养nutrition:。

生活环境living environment:急性感染acute infection慢性疾病chronic disease消化道疾病disease of digestive tract内分泌疾病endocrine disease先天性疾病congenital disease体格生长:Physique growth摄入不足insufficiency of intake胎粪排出excretion of meconium水分丢失loss of moist生长高峰summit of growth卧位clinostatasm站立位erect position头顶vertex耻骨联合上缘superior margin of pubic symphysis 耻骨联合上缘superior margin of pubic symphysis 足底sole脐nave头围:Head Circumference胸围:Chest Circumference颅骨:Cranium颅缝cranial sutures:前囟anterior fontanel:后囟posterior:脊柱:Rachis ——生理弯曲的形成长骨:Long Bone干骺端Metaphysis软骨骨化Cartilaginous ossification骨膜下成骨Subperiosteum ossification乳牙deciduous teeth恒牙permanent teeth(乳牙)萌出eruption神经系统nervous system脊髓spinal cord:运动发育:Motor development发音器官organs of voicing听觉sense of hearing大脑语言中枢cerebral language center语言交流communication护理:Nursing计划免疫:Planned Immunity心理卫生:Mental Health生活习惯living habit:社会适应能力social adaptation:亲情parent-child relationship健康查体:Physical Examination随访follow-up户外活动open field activity:身体抚触stroking massage:窒息apnea:中毒intoxication外伤trauma预防接种:Vaccination主动免疫Active immunity:被动免疫passive immunity:预防接种vaccination小儿传染病infectious disease卡介苗Bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine, BCG vaccine脊髓灰质炎疫苗Polimyelitis Vaccine麻疹疫苗Measles Vaccine百白破三联疫苗Pertussis-Diphtheria-Tetanus triple vaccine 乙肝疫苗Hepatitis B vaccine初种primary vaccination:复种revaccination:不良反应reaction:热量的需要:Caloric Requirement基础代谢:Basal Metabolism排泄Excretion蛋白质:Protein碳水化合物:Carbohydrate脂肪:Fat维生素:Vitamins水溶性维生素:Water-soluble Vitamin脂溶性维生素:Fat-soluble Vitamin矿物质:Mineral膳食纤维:Dietary Fiber母乳喂养:Breast Feeding母乳的成分:Component of Mother’s Milk免疫物质:immune material免疫球蛋白:Immune Gloulin补体:Complement乳铁蛋白:Lactoferrin溶菌酶:Lysozyme双歧因子:Bifidus Factor细胞成分:Components of Cells慢性消耗性疾病:Chronic consumptions精神障碍:Mental disorders急性传染病:Acute infectious diseases断奶:Weaning人工喂养:Bottle-Feeding稀释:Dilution加糖:Add Sugar煮沸:Boiling定时定量:Time and rationed Feeding个体差异:Individual Difference混合喂养Mixed Feeding大小便:Defecation代授法:Breast-bottle-feeding补授法:Supplemental Feeding辅食添加:The Introduction of solid food营养不良Malnutrition代谢异常Developmental and Metabolic Disorder临床分型:Clinical typing消瘦型Marasmus Malnutrition浮肿型Edema Malnutrition消瘦-浮肿型Marasmus—Edema Malnutrition病因:Etiological Factor摄入不足:Deficiency of Intake辅食添加不及时:Introduction of Solid Food饮食结构不合理:Incorrect Components of Diet不良饮食习惯:Bad Eating Habit消化吸收障碍:Disorder of Digestion and Absorption消化道先天畸形:Congenital Anomaly of Digestive Tract先天性代谢障碍:Congenital Dysbolism消化功能紊乱:Disorder of Digestive Function需求增多:Requirement Increases生长发育迅速的时期:The period when children grow rapidly 疾病恢复期:Recovery Phase of diseases双胎或多胎:Twins or Multiplets早产:Premature消耗性疾病Consumptions病理生理:Pathophysiology代谢异常:Dysbolism体温调节:Thermoregulation机体各系统功能低下:Incapacity of Body Systems消化系统:Digestive System循环系统:Circulatory System泌尿系统:Urinary System神经系统:Nervous System免疫系统:Immune System临床表现:Clinical Situation皮下脂肪Subcutaneous Fat腹Abdomen躯干Trunk臀Breech四肢Extremities面颊Cheeks皮肤Skin干燥Dehydration苍白Pale;肌肉Muscles松弛Laxity萎缩Atrophy;精神状态Mental Status萎靡Dispirited反应差Low Response;全身症状General Symptoms并发症:Complication营养性贫血:Nutritional Anemia各种维生素缺乏症:Various Kinds of Avitaminosis感染:Infections低血糖:Hypoglycemia诊断标准:Standard of Dignosis分型:Types分度:Degrees实验室检查:Laboratory Examination鉴别诊断:Differential Diagnosis治疗原则:Therapeutic Principle综合治疗Comprehensive Treatment治疗方法:Therapeutic Method积极治疗原发病:Cure the Primary Disease饮食治疗:Diet Therapy药物治疗:Drug Treatment支持治疗:Supporting Therapy危重症处理:Treatment in Crises度营养不良伴腹泻时的治疗Severe Malnutrition companied by Diarrhea:营养不良性水肿的治疗Nutritional Edema:蛋白质缺乏综合症(恶心营养不良综合症)Kwashiorkor添加辅食:Instruction of solid food睡眠充足:Sufficient Sleeping防治先天性疾病和小儿急性传染病:Prevention and Treatment of Congenital Diseases and Acute Infectious Diseases孕期保健与产前诊断:Health Care in Pregnancy and Prenatal Diagnosis新生儿筛查:Neonatal Screening治疗先天性疾病:Cure Congenital Diseases按时预防接种:Vaccination on time定期体格检查:Regular Physical Examination营养障碍性疾病Dystrophy病因及病理生理:Etiological Factor and Pathophysiology 单纯性肥胖:Simple Obesity摄入过多:Excessive Intake活动过少:Lack of Movement家族遗传:Inheritance神经、精神因素:Nervous and Mental Factors继发性肥胖:Secondary Obesity膝外翻Genu Valgum扁平足Fallen arch性发育较早:Early Sexual Development实验室检查:Laboratory Examinations胆固醇Cholesterol甘油三酯Triglyceride:β脂蛋白Beta Lipoprotein:胰岛素Insulin:生长激素Growth Hormone:诊断标准:Standard of Diagnosis轻度Mild:制度Moderate:重度Severe:。

免疫学与生殖健康免疫对生育的影响免疫系统是一个复杂而精确的机制,它在维护机体免受外来病原体侵害的同时,也与机体其他系统密切相关。

免疫学作为研究免疫系统的学科,对生育健康和生育过程产生着重要的影响。

本文将探讨免疫学在生殖健康与生育过程中的作用及其影响因素。

一、“自身免疫疾病对生育的影响”免疫系统的正常功能对于维持生殖健康至关重要。

而自身免疫疾病是一类免疫系统异常反应导致的疾病,如系统性红斑狼疮、抗磷脂抗体综合征等。

这些疾病会导致机体产生自身抗体,攻击自身抗原,从而影响生育能力。

研究发现,自身免疫疾病患者不仅存在生殖激素水平异常,还易患有不孕症、习惯性流产等问题,甚至会增加围产儿的发生病风险。

二、“免疫细胞在生育过程中的作用”免疫细胞在生育过程中发挥着重要的调节作用。

具体而言,子宫内膜和胚胎在生育过程中会受到免疫细胞的调控。

细胞因子在胚胎植入、子宫内膜腺泡发育等过程中扮演重要角色。

它们作为免疫介质,调节着子宫内膜的免疫适应性,促进胚胎植入和胚胎发育。

一旦免疫细胞的功能异常或者数量异常,就会影响生育过程,导致不可预期的结果,如流产、胎盘早剥等。

三、“免疫耐受对胎儿发育的影响”免疫耐受是指机体对胚胎抗原的容忍性。

在妊娠过程中,胚胎携带父亲的抗原,对母体来说是一种异物,免疫系统在这个过程中会经历一系列的调节。

如果免疫系统无法适应这一过程,就会导致排斥反应,对胎儿发育产生不良影响。

因此,免疫耐受对于保障胎儿健康发育至关重要。

四、“免疫调节对生育健康的干预”了解免疫对生育的影响后,我们可以运用相应的干预方法来维护生育健康。

一方面,对于某些免疫异常相关的不孕症或习惯性流产,可以通过免疫调节的方法来调整机体的免疫功能,提高生育能力。

另一方面,通过调节免疫耐受,控制排斥反应,保障胎儿的健康发育。

总结起来,免疫学与生殖健康有着密不可分的关系。

了解免疫系统在生育过程中的作用及其影响因素,对于保障生育健康具有重要的意义。

● 研究背景●目前的研究表明多种病因学通路与孤独症患病风险增加是相关的。

例如,很多单基因综合征和其他罕见新生突变已经被证实在孤独症儿童中有很高的外显性,当然现在还有很多未发现的遗传因素。

一些罕见的高置信度的基因突变显著发生在参与突触功能、转录调控和染色质重塑功能的基因中。

早前的双胞胎研究表明,尽管遗传因素在孤独症的病因学中起着重要的作用,但是环境因素也不容忽视。

最近的证据也表明遗传、环境因素及其相互作用可能在胎儿大脑发育的早期起作用,通过影响一些重要通路蛋白质或基因的表达,使孤独症儿童表现出差异性。

因此,研究者认为可以通过构建环境因素影响模型来研究环境因素在胎儿大脑发育早期阶段的影响。

早前临床研究已经证实母亲孕期病毒或细菌感染会使胎儿大脑早期发育发生变化,并增加后代患孤独症的风险。

欲研究母亲孕期感染对胎儿大脑发育的影响,可以构建母体免疫激活模型。

目前常用的方法有在大鼠或小鼠孕期注射poly(I:C)和脂多糖来诱导母体免疫激活状态。

研究已表明poly(I:C)和脂多糖会影响母体通过胎盘的细胞因子信号,进而影响胎儿大脑的发育,也会阻断一些对神经元有保护作用的关键通路,从而诱导出存在孤独症样行为的动物模型。

尽管目前已经知道母体免疫激活与孤独症病理学间存在关联,但母体免疫激活如何在基因组和表观遗传学水平上对发育中的胎儿大脑产生影响还不明确。

因此研究者开展了此研究,欲探寻母体免疫激活对孤独症相关遗传风险机制的影响。

●泰和国医孤独症中心研究结果●1. 早前的研究对SD大鼠在孕期第15天经腹腔注射脂多糖以诱导母体免疫激活状态,之后分别在4小时和24小时后采集胎鼠的大脑组织开展转录组测序。

本研究的研究者下载了这部分数据进行分析,发现在母体免疫激活4小时后,胎鼠的转录组失调,与对照组胎鼠相比,母体免疫激活的胎鼠中有4959个基因显著下调,有4033个基因显著上调(q<0.01)。

与母体免疫激活4小时影响不同的是,在母体免疫激活24小时后,胎鼠大脑的差异表达基因减少,只有一个基因(MAIN)显著下调,有两个基因(LCP2, RPL39)显著上调。

孩子有自闭症与母亲怀孕有关吗文章目录*一、孩子有自闭症与母亲怀孕有关吗*二、孩子自闭症怎么办*三、孩子自闭症的表现孩子有自闭症与母亲怀孕有关吗1、研究人员宣布一项最新研究成果:母亲孕期出现发烧症状,或者罹患糖尿病、慢性高血压、孕前肥胖症等,都会增加孩子患自闭症的风险。

2、研究人员发现,母亲在孕期任何阶段罹患感冒不会提高孩子罹患自闭症或其他发育障碍的风险,但如果母亲在孕期因病而出现发烧症状,那么她们的孩子今后患自闭症的几率是在孕期没有发烧的母亲所生孩子的两倍,特别是当母亲在孕中期出现发烧症状的话,孩子罹患自闭症的几率会更高。

3、另外一项最新研究发现,如果母亲罹患糖尿病(包括II型糖尿病和妊娠糖尿病)、慢性高血压、孕前肥胖症,她们的孩子罹患自闭症的风险也比较高。

4、铁对人体早期的大脑发育同样也起着重要的作用,铁元素参与了神经递质产生、髓鞘形成和免疫功能的运行,然而儿童自闭症恰恰与这三者有着密切的关系。

有关专家介绍,铁质对胎儿的大脑发育是起着相当重要的作用,同时这也就意味着胎儿缺铁会导致自闭症的可能性。

5、经科学研究表明,孩子患上自闭症与妈妈孕期缺铁有关,同时还证明了如果孩子出生时妈妈的年龄在35岁以上时,因为年里大,这个风险将会增加5倍。

如果孕妇患有高血压或是肥胖等疾病的话,那么孩子就很可能患有自闭症。

孩子自闭症怎么办1、创造愉快的家庭氛围在孩子小的时候,父母的行为往往会对孩子产生很深远的影响,那么创造一个健康愉快的家庭氛围是必不可少的。

2、多培养孩子兴趣父母的引导对孩子发展至关重要,给孩子讲故事、和孩子一起做游戏、教画画等,多参与孩子的生活,开发孩子的心智,加强情感。

3、结交小朋友,发展交友圈对孩子来说,世界往往很好奇,那么结交朋友往往不可或缺,家长应该让孩子多结交朋友,这对孩子百无害处。

还可以避免孩子出现自闭。

4、增加新鲜感声音和色彩往往对孩子的影响比较大,可以转移孩子的注意力。

孩子往往对那些彩色的东西感到好奇,所以多多培养孩子对事物的感知也是很有必要的。

自闭症的遗传和生态因素分析引言:自闭症是一种常见的神经发育障碍,其特征为社交互动缺陷、沟通困难和刻板重复行为。

自闭症的发病原因至今仍然不明确,但遗传因素和环境因素被认为在其发展中起着重要作用。

本文将对自闭症的遗传和生态因素进行分析,以期加深我们对该疾病的了解。

一、遗传因素对自闭症的影响1. 主要基因突变与自闭症的关联通过大量家系和孪生子调查,科学家已经确定自闭症具有明显的遗传倾向。

近年来的基因筛查表明,多个基因异常与自闭症存在联系。

例如,在儿童期出现较高频率基本置换突变(CNV)的染色体区域可导致高风险患上自闭。

此外,部分单核苷酸多态性(SNP)也与该疾病相关。

2. 基因-环境互动研究表明,基因突变可能与环境因素相互作用,导致自闭症风险增加。

例如,孕期暴露于污染物、药物或感染等环境因素,可能通过干扰胎儿的大脑发育过程,与部分基因突变相互作用从而增加了自闭症的风险。

二、生态因素对自闭症的影响1. 孕期和早期生活环境孕期和早期生活环境可能对自闭症的发生起到决定性影响。

一些研究表明,孕期暴露于气候异常、化学物质以及压力等不良环境因素会增加婴儿患上自闭症的风险。

此外,早期生活中遭受到家庭创伤经历和抚养方式等影响均与该疾病相关。

2. 社交互动和认知刺激自闭症患者社交互动缺陷可能与其生态环境中缺少社交机会及认知刺激有关。

正常情况下,婴幼儿通过与父母和同龄人的互动来学习社交技巧并培养注意力等认知能力。

然而,自闭症患者可能面临社交能力和认知刺激不足的挑战,这可能影响了他们的神经发育。

三、遗传和生态因素相互作用对自闭症的影响研究表明,遗传因素和生态因素在自闭症中相互作用以及共同贡献着其发展。

遗传倾向使得某些个体更易受到环境因素的影响。

例如,一项研究发现特定基因突变与孕期接触细菌感染相关,从而增加了自闭症的风险。

此外,基因-环境互动还可能通过调整特定信号途径(如免疫反应)来导致神经发育异常。

结论:自闭症是一种由遗传和生态因素共同作用引起的神经发育障碍。

基础医学与临床㊀㊀Basic&ClinicalMedicine2019 39(12)37:1261 ̄1269.[4]王皓毅ꎬ李劲松ꎬ李伟.基于CRISPR ̄Cas9新型基因编辑技术研究[J].生命科学ꎬ2016ꎬ8:867 ̄870. [5]谢一方ꎬ王永明.基因编辑技术的原理及其在癌症研究中的应用[J].中国肿瘤生物治疗杂志ꎬ2017ꎬ24:815 ̄827.[6]王大勇ꎬ马宁ꎬ惠洋ꎬ等.CRISPR/Cas9基因组编辑技术在癌症研究中的应用[J].遗传ꎬ2016ꎬ12:1 ̄8. [7]ChenXꎬZhengPꎬXueZꎬetal.CacyBP/SIPenhancesmultidrugresistanceofpancreaticcancercellsbyregula ̄tionofP ̄gpandBcl ̄2[J].Apoptosisꎬ2013ꎬ18:861 ̄869. [8]FengSꎬZhouQꎬYangBꎬetal.TheeffectofS100A6onnucleartranslocationofCacyBP/SIPincoloncancercells[J].PLoSOneꎬ2018ꎬ13:e0192208.doi:10.1371/jour ̄nal.pone.0192208.[9]ZhaiHꎬMengJꎬJinHꎬetal.RoleoftheCacyBP/SIPproteiningastriccancer[J].OncolLettꎬ2015ꎬ9:2031 ̄2035.[10]KilańczykEꎬGwoz'dzińskiKꎬWilczekEꎬetal.Up ̄regu ̄lationofCacyBP/SIP/SIPduringratbreastcancerdevel ̄opment[J].BreastCancerꎬ2014ꎬ21:350 ̄357. [11]王燕ꎬ王宁菊ꎬ李少林.siRNA下调CacyBP/SIP/SIP基因对人乳腺癌细胞增殖㊁凋亡㊁侵袭的影响[J].肿瘤ꎬ2013ꎬ33:670 ̄675.新闻点击1型糖尿病可能会伤害幼儿大脑发育2019 ̄06 ̄14在旧金山举行的美国糖尿病协会上发表的一项新的研究表明ꎬ在早期被诊断出患有1型糖尿病的儿童ꎬ其脑部区域的生长速度减缓ꎬ与轻度认知缺陷有关ꎮ该研究比较了患有1型糖尿病的儿童脑部MRI和没有这种情况的年龄匹配的儿童ꎮ研究人员还发现ꎬ大脑生长缓慢的区域与较高的血糖水平相关ꎮ该研究的首席研究员佛罗里达州杰克逊维尔Nemours儿童健康系统小儿内分泌科主任NellyMauras博士说: 我们发现参与大量认知功能的不同脑区的体积存在显著的可检测和持续差异ꎬ大脑中的整体生长速度较慢ꎮ 研究人员还测试了儿童的思维和记忆能力(认知功能)ꎬ并发现智商得分有5~7分的差异ꎮ怀孕时摄入加工食品可能与儿童自闭症有关2019 ̄06 ̄19在线发表在«科学报告»上一篇来自奥兰多中佛罗里达大学(UCF)医学院的研究人员发现ꎬ高水平的丙酸(PPA)(用于加工食品以延长保质期)改变了胎儿大脑中神经系统的发育ꎮ这项由SalehNaser博士领导的研究将母体PPA暴露与 可能的自闭症前体 联系起来ꎬ研究人员指出ꎬ有充分的理由认为自闭症患者的肠道是一个潜在的诱因ꎮNaser想了解为什么患有自闭症的儿童经常患上胃肠道疾病ꎮ在实验中ꎬUCF团队发现ꎬ将人类胎儿神经系统干细胞暴露于高PPA水平会通过减少转变为神经元的细胞数量和通过增加成为神经胶质细胞的数量来破坏脑细胞之间的自然平衡ꎬ这是神经系统关键的一部分ꎮ虽然神经胶质细胞有助于发育和保护神经元ꎬ但如果胶质细胞太多ꎬ它们可能会影响神经元之间的联系并导致炎性反应ꎬ这在自闭症儿童的大脑中可见ꎮ研究人员认为:神经元减少和受损通路阻碍了大脑的交流能力ꎬ导致自闭症儿童经常出现的行为ꎬ包括重复行为㊁行动不便和无法与他人互动ꎮ以前的研究已经提出自闭症与环境和基因之间的联系ꎬ但UCF研究人员指出ꎬ他们的研究首次表明高水平的PPA与神经胶质细胞的生长㊁神经系统功能紊乱和自闭症之间存在联系ꎮ刘晓荻㊀译薛惠文㊀编8861。

maternal词根-回复Maternal, Derived from the Latin word "mater" meaning mother, the term maternal relates to aspects of motherhood, including nurturing, caregiving, and the unique bond between a mother and her child. While motherhood is a natural instinct for many women, the concept of being maternal extends beyond biological ties and encompasses the qualities that reflect loving care and protection towards others.Humans have long observed the maternal instinct in various species, but it is most prominently associated with the role of a mother in rearing and raising her offspring. From the moment a woman discovers she is expecting, a cascade of emotions floods her, bonding her to the miraculous life growing within her. Throughout history, this maternal connection has been revered, celebrated, and studied by scientists, psychologists, and sociologists alike.The maternal instinct encompasses a spectrum of characteristics, including love, compassion, protectiveness, and selflessness. For many, the maternal bond is deepened through the biological processes of pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. Theresponsibilities of motherhood shape a woman's life, as she takes on the role of a caregiver, nurturer, supporter, and teacher. The maternal bond encourages a sense of closeness and emotional attachment like no other.However, being maternal is not solely limited to biological mothers. Many women who have chosen the path of adoption or become stepmothers have exemplified the utmost love and care for their children, even without the shared biological connection. Women who have struggled with infertility may find alternative means of nurturing, such as becoming foster parents or contributing to the lives of children in other meaningful ways.Additionally, the maternal role can extend beyond humans. In the animal kingdom, examples of maternal behavior can be observed in various species. From the fierce protection of a mother lioness over her cubs to the diligent care provided by a mother bird to her hatchlings, these acts of maternal instinct showcase the powerful bond between a mother and her offspring.Neuroscience has also shed light on the biological basis of the maternal instinct. Studies have revealed the release of oxytocin,commonly known as the "love hormone," during instances of maternal caregiving. This hormone promotes the bonding between a mother and her child, fostering feelings of warmth and affection.Furthermore, societal influences play a significant role in shaping maternal behavior. Cultures around the world have varying expectations and norms surrounding motherhood. These societal constructs can influence women's understanding of and approach to being maternal. From traditions and rituals to support systems and social expectations, the cultural backdrop shapes the experiences of motherhood.The concept of being maternal expands beyond the realm of caregiving for children. Women often display maternal qualities in their interactions with others, such as nurturing friendships, mentoring younger individuals, or taking care of family members in need. This broader interpretation emphasizes the innate capacity within women to provide guidance, support, and care to those around them.In conclusion, the maternal instinct encompasses the qualities oflove, compassion, protectiveness, and selflessness. From the biological ties of pregnancy and childbirth to the unconditional love shared between adoptive mothers and their children, the maternal bond is universal. The role of a mother extends beyond the biological sense and encompasses the nurturing, caregiving, and loving actions of women towards others. Whether observed in humans or across various species, the maternal instinct is a remarkable testament to the power of love and the enduring bond between a mother and her child.。

孕妇病原微生物感染对早产影响的研究进展

孕妇病原微生物感染对早产的影响是一个备受关注的研究领域。

早产是指孕妇怀孕20周-37周之间分娩的情况,它是新生儿死亡和儿童发育障碍的主要原因之一。

病原微生物感染是导致早产的一个重要因素,其中包括细菌、病毒、寄生虫和念珠菌等。

以下是近年来关于孕妇病原微生物感染对早产影响的研究进展。

细菌感染被认为是导致早产最常见的原因之一。

多个研究表明,孕妇阴道感染细菌,如大肠埃希菌、金黄色葡萄球菌和链球菌等,与早产的发生率显著增加相关。

细菌通过破坏子宫内膜和胎膜的完整性,导致炎症反应和子宫收缩,进而引发早产。

病毒感染也被发现与早产相关。

巨细胞病毒感染被认为是引发早产的一个重要因素。

巨细胞病毒感染可以导致子宫肌肉收缩和胎膜破裂,从而引发早产。

流感病毒、风疹病毒和单纯疱疹病毒等也被发现与早产风险增加相关。

寄生虫感染也可能导致早产。

一些研究发现,孕妇患有寄生虫感染,如弓形虫和毛滴虫等,与早产的发生率增加有关。

寄生虫感染可能通过导致子宫内膜炎症和胎膜破裂等机制来引发早产。

念珠菌感染在孕妇中也较为常见,并与早产有关。

念珠菌感染可以导致宫颈炎症和胎膜破裂等情况,从而诱发早产。

一些研究发现,孕妇生殖道中存在念珠菌感染,与早产的发生显著相关。

孕妇病原微生物感染对早产的影响是一个复杂而多样的过程。

病原微生物感染通过破坏子宫内膜和胎膜的完整性,引发炎症反应和子宫收缩,从而导致早产。

当前的研究进展仍在不断进行中,以进一步阐明孕妇病原微生物感染与早产之间的关系,为早产的预防和治疗提供更好的策略和指导。

MATERNAL INFECTION AND IMMUNE INVOLVEMENT INAUTISM

Paul H. PattersonBiology Division, California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91125 USA

AbstractRecent studies have highlighted a connection between infection during pregnancy and increasedrisk for autism in the offspring. Parallel studies of cerebral spinal fluid, blood, and postmortembrains reveal an ongoing, hyper-responsive inflammatory-like state in many young as well as adultautism subjects. There are also indications of gastrointestinal problems in at least a subset ofautistic children. Work with animal models of the maternal infection risk factor indicate thataspects of brain and peripheral immune dysregulation can be begin during fetal development andbe maintained through adulthood. The offspring of infected, or immune-activated dams alsodisplay cardinal behavioral features of autism, as well as neuropathology consistent with that seenin human autism. These rodent models are proving useful for the study of pathogenesis and gene-environment interaction, as well as for the exploration of potential therapeutic strategies.

Maternal infection and autismThere is little public awareness that infection during pregnancy significantly increases theprobability of the offspring becoming schizophrenic. In fact, it has been estimated that ifviral (influenza, Herpes simplex virus, rubella), bacterial (urinary tract) and parasitic(toxoplasma) infections could be prevented in pregnant women, >30% of schizophreniacases could be eliminated (1). The public health implications are enormous, but not widelyrecognized (2). Similarly, there is little public or scientific awareness that maternal infectionalso increases the risk for development of autism in the offspring. An extraordinary recentstudy of over 10,000 autism cases in the Danish Medical Register found a strong associationwith maternal viral infection in the first trimester and a less robust, but significantassociation with maternal bacterial infection in the second trimester (3). These new resultsgreatly extend prior work on the connection between maternal infection and autism (4).Supporting the epidemiology, recent results with rodent models of the maternal infectionrisk factor reveal that the offspring display features of autism, as well as immune-relateddisruptions in the brain and periphery. Moreover, new work on human autism spectrumdisorders (ASD) reinforces this immune connection.

© 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.Corresponding author: php@caltech.edu.Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to ourcustomers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review ofthe resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may bediscovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

NIH Public AccessAuthor ManuscriptTrends Mol Med. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 July 1.Published in final edited form as:Trends Mol Med. 2011 July ; 17(7): 389–394. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2011.03.001.

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author ManuscriptNIH-PA Author ManuscriptImmune-related abnormalities in autismA variety of organ systems exhibit inflammatory-like changes in autism. The evidencecomes from quantifying immune-related proteins and RNAs, as well asimmunohistochemistry. Findings from epidemiology are also relevant.

Brain and CSFA groundbreaking paper by Carlos Pardo and colleagues (5) revealed an inflammatory-likestate in post-mortem autism brains as indicated by elevated cytokines and activatedmicroglia and astrocytes. Importantly, these changes were found in subjects ranging in agefrom 5 to 44 years old, indicating that this immune-activated state is established early andappears to be permanent. Moreover, cytokine elevation was also found in the cerebral spinalfluid (CSF) of living autistic children ages 3 to 10 years old. Recent results from studies ofsome of the same postmortem brains and new autism brain samples, as well as CSF, havesupported these conclusions (6, 7). Consistent with these findings are results from a varietyof microarray studies that show dysregulation of immune-related genes (e.g. cytokines andchemokines) in autistic brains (8). It is also clear that there is considerable heterogeneityamong the autism samples, as might be expected from the extreme disparities in behavioralsymptoms among ASD subjects.