The Progenitor Masses of Wolf-Rayet Stars and Luminous Blue Variables Determined from Clust

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:316.40 KB

- 文档页数:73

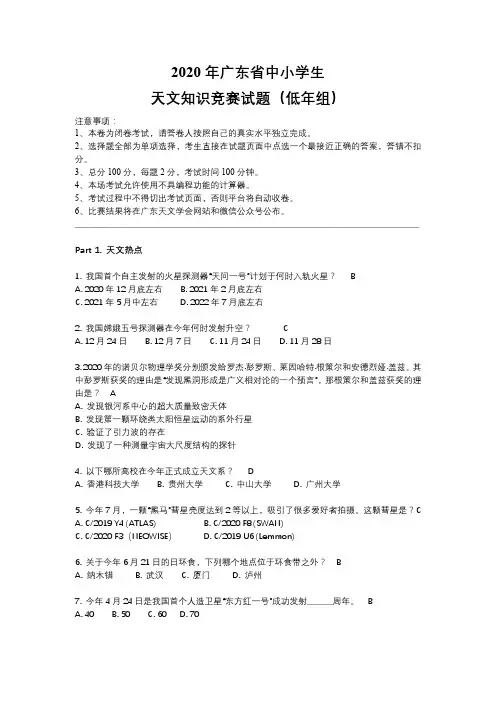

2020年广东省中小学生天文知识竞赛试题(低年组)注意事项:1、本卷为闭卷考试,请答卷人按照自己的真实水平独立完成。

2、选择题全部为单项选择,考生直接在试题页面中点选一个最接近正确的答案,答错不扣分。

3、总分100分,每题2分,考试时间100分钟。

4、本场考试允许使用不具编程功能的计算器。

5、考试过程中不得切出考试页面,否则平台将自动收卷。

6、比赛结果将在广东天文学会网站和微信公众号公布。

_______________________________________________________________________________________________ Part 1. 天文热点1. 我国首个自主发射的火星探测器“天问一号”计划于何时入轨火星? BA. 2020年12月底左右B. 2021年2月底左右C. 2021年5月中左右D. 2022年7月底左右2. 我国嫦娥五号探测器在今年何时发射升空? CA. 12月24日B. 12月7日C. 11月24日D. 11月28日3. 2020年的诺贝尔物理学奖分别颁发给罗杰·彭罗斯、莱因哈特·根策尔和安德烈娅·盖兹。

其中彭罗斯获奖的理由是“发现黑洞形成是广义相对论的一个预言”,那根策尔和盖兹获奖的理由是? AA. 发现银河系中心的超大质量致密天体B. 发现第一颗环绕类太阳恒星运动的系外行星C. 验证了引力波的存在D. 发现了一种测量宇宙大尺度结构的探针4. 以下哪所高校在今年正式成立天文系? DA. 香港科技大学B. 贵州大学C. 中山大学D. 广州大学5. 今年7月,一颗“黑马”彗星亮度达到2等以上,吸引了很多爱好者拍摄。

这颗彗星是?CA. C/2019 Y4 (ATLAS)B. C/2020 F8 (SWAN)C. C/2020 F3(NEOWISE)D. C/2019 U6 (Lemmon)6. 关于今年6月21日的日环食,下列哪个地点位于环食带之外? BA. 纳木错B. 武汉C. 厦门D. 泸州7. 今年4月24日是我国首个人造卫星“东方红一号”成功发射_______周年。

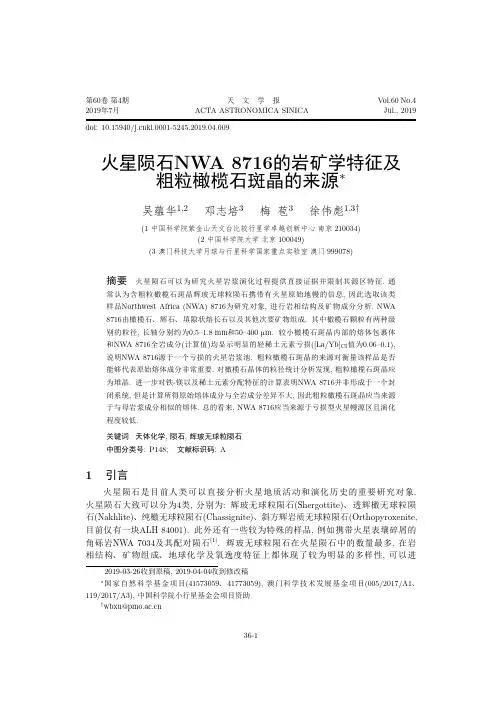

第60卷 第4期 2019年7月天文学报 ACTA ASTRONOMICA SINICAdoi: 10.15940/ki.0001-5245.2019.04.009Vol.60 No.4 Jul., 2019火星陨石NWA 8716的岩矿学特征及 粗粒橄榄石斑晶的来源∗吴蕴华1,2 邓志培3 梅 苞3 徐伟彪1,3†(1 中国科学院紫金山天文台比较行星学卓越创新中心 南京 210034) (2 中国科学院大学 北京 100049)(3 澳门科技大学月球与行星科学国家重点实验室 澳门 999078)摘要 火星陨石可以为研究火星岩浆演化过程提供直接证据并限制其源区特征. 通常认为含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石携带有火星原始地幔的信息, 因此选取该类 样品Northwest Africa (NWA) 8716为研究对象, 进行岩相结构及矿物成分分析. NWA 8716由橄榄石、辉石、填隙状熔长石以及其他次要矿物组成. 其中橄榄石颗粒有两种级 别的粒径, 长轴分别约为0.5–1.8 mm和50–400 µm. 较小橄榄石斑晶内部的熔体包裹体 和NWA 8716全岩成分(计算值)均显示明显的轻稀土元素亏损([La/Yb]CI值为0.06–0.1), 说明NWA 8716源于一个亏损的火星岩浆池. 粗粒橄榄石斑晶的来源对衡量该样品是否 能够代表原始熔体成分非常重要. 对橄榄石晶体的粒径统计分析发现, 粗粒橄榄石斑晶应 为堆晶. 进一步对铁-镁以及稀土元素分配特征的计算表明NWA 8716并非形成于一个封 闭系统, 但是计算所得原始熔体成分与全岩成分差异不大, 因此粗粒橄榄石斑晶应当来源 于与母岩浆成分相似的熔体. 总的看来, NWA 8716应当来源于亏损型火星幔源区且演化 程度较低.关键词 天体化学, 陨石, 辉玻无球粒陨石 中图分类号: P148; 文献标识码: A1 引言火 星 陨 石 是 目 前 人 类 可 以 直 接 分 析 火 星 地 质 活 动 和 演 化 历 史 的 重 要 研 究 对 象. 火星陨石大致可以分为4类, 分别为: 辉玻无球粒陨石(Shergottite)、 透辉橄无球粒陨 石(Nakhlite)、纯橄无球粒陨石(Chassignite)、斜方辉岩质无球粒陨石(Orthopyroxenite, 目前仅有一块ALH 84001). 此外还有一些较为特殊的样品, 例如携带火星表壤碎屑的 角砾岩NWA 7034及其配对陨石[1]. 辉玻无球粒陨石在火星陨石中的数量最多, 在岩 相结构、 矿物组成、 地球化学及氧逸度特征上都体现了较为明显的多样性, 可以进2019-03-26收到原稿, 2019-04-04收到修改稿 ∗国家自然科学基金项目(41573059、 41773059), 澳门科学技术发展基金项目(005/2017/A1、 119/2017/A3), 中国科学院小行星基金会项目资助 †wbxu@36-160 卷天文学报4期一步划分为玄武质辉玻无球粒陨石(Basaltic Shergottite)、 二辉橄榄质辉玻无球粒陨 石(Lherzolitic Shergottite)、 以及含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石(Olivine-phyric Shergottite)[2–4]. 这些差异可能是受到氧化的火壳物质不同程度的混染导致[5]; 或者是 继承于不均一的火幔源区[6–7]. 除少量样品外, 大多数玄武质辉玻无球粒陨石轻稀土元 素(LREE)相对富集, 含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石的LREE相对亏损, 而二辉橄榄 质辉玻无球粒陨石常介于二者之间[4, 8]. 最初的研究认为, 含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球 粒陨石与其他类型的辉玻无球粒陨石相比, 全岩的成分更为富镁, 并且含有核部非常富 镁的橄榄石, 通常形成于氧逸度较低的环境中, 可能直接来源于原始火幔的部分熔融, 例如样品Yamato 980459的成分可以反映原始火星幔的物质组成[9–10]. 但是也有一些样 品中粗粒的橄榄石斑晶是来源于其他成分熔体的捕掳晶, 例如Sayh al Uhaymir (SaU) 005[11], 在这样的情况下样品整体组成就不能代表原始火星幔的成分特征. 因此正确认 识橄榄石斑晶的地球化学特征对能否从样品中获取原始火星幔的成分特征至关重要.NWA 8716于2014年在西北非洲沙漠地区发现, 总重约168 g, 是一块较富镁的含粗 粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石. 本文主要通过对矿物成分以及岩石结构上的观察, 分析 橄榄石斑晶来源以及结晶过程, 探讨该样品是否携带原始火星幔的成分信息.2 实验方法本文主要开展对火星辉玻无球粒陨石NWA 8716的岩石结构与矿物化学成分特征 的研究(样品分析面积约为1.1 cm2). 利用扫描电子显微镜(Hitachi S3400N-II)获取样品 的背散射(BSE)图像, 加速电压为15 kV. 利用电子探针(JEOL JXA-8230)测试了矿物的 主量元素化学成分. 分析橄榄石、 辉石、磷酸盐及铁氧化物时采用的电流为20 nA; 分 析长石时采用的电流为10 nA、 束斑为10 µm. 一般情况下元素特征峰测量时间为20 s, 背景值测量时间为10 s, 而分析K与Na的特征峰测量时间为10 s, 背景值测量时间为5 s. 使用的标准矿物为美国SPI (Structure Probe, Incorperated)显微实验耗材供应公司 提供的天然矿物及合成化合物. 最终数据经过ZAF (Atomic number Z, Absorption, Fluorescence)校正. 以上实验在中国科学院紫金山天文台完成.稀土元素含量的分析工作在中国地质大学(武汉)地质过程与矿产资源国家重点实验 室利用LA-ICP-MS (Laser Ablation Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry)完 成. 激光剥蚀系统为GeoLas 2005, ICP-MS为Agilent 7500a. 激光剥蚀过程中采用氦气 作载气、 氩气为补偿气以调节灵敏度, 二者在进入ICP之前通过一个T型接头混合. 在 等离子体中心气流(Ar+He)中加入了少量氮气, 以提高仪器灵敏度、降低检出限和改善 分析精密度[12]. 激光剥蚀系统配置有信号平滑装置[13]. 每个数据的测试包括大约20– 30 s的空白信号和50 s的样品信号. 详细的仪器操作条件同Liu等[14]. 以USGS (United States Geological Survey)参考玻璃(BCR-2G, BIR-1G和BHVO-2G)为校正标准, 对于 硅酸盐稀土元素数据处理利用多外标、 无内标法[14], 而磷酸盐稀土元素数据处理采取 多外标、 内标法[15]. 每9个样品分析点后插入一个标准样品SRM (Standard Reference Material) 610的分析以便进行时间漂移校正. 对分析数据的离线处理(包括对样品和 空白信号的选择、 仪器灵敏度漂移校正、 元素含量计算)采用软件ICPMSDataCal进 行[14–15].36-260 卷吴蕴华等: 火星陨石NWA 8716的岩矿学特征及粗粒橄榄石斑晶的来源4期3 实验结果3.1 岩石学特征样品中主要矿物为橄榄石、 辉石及长石. 橄榄石有大小两种级别的粒径分布. 较 大的橄榄石斑晶长轴约为0.5–1.8 mm, 在背散射图像中可观察到明显的环带结构(图1 (a)). 虽然橄榄石较为自形, 但是部分颗粒仍呈现较破碎的外形, 如图1 (a)中左下方 的橄榄石, 原生形态不完整. 斑晶内部可见细粒铬铁矿(0.5–5 µm)和由细粒铬铁矿组 成的5–80 µm不等的粒状或线状铬铁矿集合体, 在同一个粗粒斑晶内部大致呈定向分 布(图1 (b)); 较小的橄榄石斑晶约为50–400 µm, 常为自形−半自形, 不具有明显环带 结构, 成分相对均一, 如图1 (c)所示, 在该类橄榄石内部可见由少量辉石雏晶与玻璃组 成的熔体包裹体. 辉石的粒径范围较大, 约为40–750 µm, 多为自形或半自形, 在所有 辉石中都可以观察到成分环带, 并且在较大的辉石颗粒中成分环带结构更为明显(图1 (d)). 熔长石呈它形填隙在橄榄石和辉石之间. 粒径为2–80 µm的铁硫化物与尖晶石颗 粒广泛分布在样品中. 样品整体BSE全貌图像见图2, 其中未见快速结晶形成的枝晶状 填隙物. 主要矿物模式丰度如表1所示, 副矿物白磷钙矿约占0.4%. 用于对比的Yamato 980459、Larkman Nunatak (LAR) 06319和SaU 005均为含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒 陨石[10–11, 16].(a)(b)Olivine megacrystOlivine megacrystMaskelynite (c)PyroxeneFine-grained chromite(d)Olivine phenocryst PyroxeneMaskelyniteMelt inclusionMaskelynite OlivineZonation Pyroxene图 1 样品NWA 8716背散射(BSE)图像. (a)粗粒橄榄石斑晶展现明显成分环带; (b)粗粒橄榄石斑晶中的细粒铬铁矿; (c)较小的橄榄石斑晶, 成分相对较均匀, 含有熔体包裹体; (d)几乎所有的辉石斑晶均呈现成分环带, 图像中部较大辉石颗粒成分环带非常明显.Fig. 1 Backscattered electron (BSE) images of NWA 8716. (a) Olivine megacrysts exhibiting distinct chemical zoning; (b) Fine-grained chromite within olivine megacrysts; (c) A relatively small and homogeneous olivine phenocryst with a melt inclusion; (d) Almost all pyroxene phenocrysts have chemical zoning, and the large grain in the center exhibits a strong zonation.36-360 卷天文学报4期Pyroxene1 mmOlivine megacrystOlivine phenocrystMaskelynite图 2 样品NWA 8716的BSE全貌图像 Fig. 2 The overview BSE image of NWA 8716表 1 NWA 8716的矿物模式丰度(vol%)以及与其他火星辉玻无球粒陨石的对比 Table 1 Mineral modal abundance (vol%) of NWA 8716 and comparison with otherMartian shergottitesMineralsNWA Yamato LAR SaU Olivine-Basa-Lherzo-8716 980459[10] 06319[16] 005[11] phyric[8, 11, 17] ltic[8, 11, 17] litic[8, 11, 17]Megacryst 14.6 6.2OlivinePhenocryst 3.05.824.4 21–297–290.3–435–60Pyroxene62.4 5855.0 ∼5648–7238–804–85Maskelynite 18.1-19.1 1512–2710–48< 10Minor phases 1.9 1–23.6-1–32–5<2Mesostasis-23-----3.2 矿物化学特征 橄榄石成分变化范围较大Fo82.7−52.2 (Fo为Mg/[Mg+Fe]摩尔比×100), 粗粒橄榄石斑晶相对富镁(晶核部最富镁), 较小斑晶相对富铁. 粗粒橄榄石斑晶成分环带结构明显, 图3展示一个典型粗粒橄榄石斑晶成分横剖面, 图3 (a)核部(Fo79.8−82.7)明显比边部(最边 部为Fo67.5)更为富镁, 并且核部成分相对较为均匀. 图3 (b)所示MnO含量也存在成分环 带, 核部的MnO含量相对较低, 边部MnO含量增加, 与MgO含量有较好的相关性. 通常 情况下粗粒斑晶的核部成分为Fo79.3−82.7, 边部成分则延续至Fo64.8. CaO含量不呈现明 显变化(平均值约为0.21 wt%). 较小的橄榄石斑晶成分相对更为均一, 且与粗粒橄榄石 斑晶相比FeO含量更高(Fo52.2−61.2), MnO含量也较高, 较小斑晶和粗粒斑晶MnO含量分 别为0.58–0.73 wt%和0.31–0.61 wt%, 而CaO含量未呈现明显差异. 粗粒橄榄石斑晶与36-460 卷吴蕴华等: 火星陨石NWA 8716的岩矿学特征及粗粒橄榄石斑晶的来源4期较小橄榄石斑晶的Fe/Mn比值分别为57.8 ± 2.4与51.1 ± 4.0.Fo value90 (a)85807570656000.2 0.4 0.6 0.811.2Distance /mm 1.0(b) 0.80.60.40.2MnO content /wt%00.2 0.4 0.6 0.811.2Distance /mm图 3 一个粗粒橄榄石斑晶的成分剖面图. (a) Fo值剖面图; (b) MnO含量剖面图.Fig. 3 Compositional profiles of an olivine megacryst. (a) The zoning profile of Fo value; (b) The zoning profile of MnO content.辉石以易变辉石为主(Fs17.7−35.3Wo6.7−16.3) (Fs为Fe/[Mg+Fe+Ca]摩尔比×100, Wo 为Ca/[Mg+Fe+Ca]摩尔比×100), 另有少量斜方辉石(Fs17.8−25.5Wo1.4−5.0), 在少数辉石 斑晶最边部可以观察到普通辉石(Fs19.1−21.9Wo31.6−33.4) (图4). 辉石斑晶的Fe/Mn比值 为32.4 ± 3.6. 几乎所有的辉石都具有成分环带结构, 部分辉石的环带较规则, 核部为 低钙且较富镁的古铜辉石, 边部CaO与FeO含量增加, 为相对较富铁的易变辉石, 如图1(d)中展示的较大辉石颗粒.(a) DiCrHd(b)0.10.90.3 LAR augite mantleNWA 5789 rimLAR Fe-richmantleNWA 5789 coreAl NWA 5789LAR core outermost rim and mesostasisEnFs0.60.32Ti0.60.9图 4 NWA 8716辉石与尖晶石成分示意图. (a)辉石端元成分示意图, 含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石LAR 06319 (图上标记为LAR)[18]以及NWA 5789[19]中辉石成分也标示在图上以作对比; (b)尖晶石端元成分示意图, 成分变化范围较大.Fig. 4 The composition of pyroxene and spinel in NWA 8716. (a) Pyroxene quadrilateral of NWA 8716. The composition of olivine-phyric shergottite LAR 06319 (noted as LAR)[18] and NWA 5789[19] pyroxene are also shown for comparison; (b) Ternary plot of spinel with a relatively wide compositional variation.36-560 卷天文学报4期NWA 8716中的长石几乎全部转变成为熔长石, 呈它形填隙于主要矿物之间, 成分均 一, 主要为拉长石(An53.4−66.8Ab32.9−46.0) (An为Ca/[K+Na+Ca]摩尔比×100, Ab为Na/ [K+Na+Ca]摩尔比×100), K2O含量较低(少于0.1 wt%), Or值小于1 (0.3–0.8) (Or为K/ [K+Na+Ca]摩尔比×100).尖晶石族矿物主要为铬铁矿和富钛尖晶石, 成分变化较大, 被包裹于橄榄石内部的 微米级尖晶石颗粒通常靠近富铬端元, 而稍粗粒的尖晶石颗粒成分逐渐富钛(图4 (b)). 白磷钙矿的成分则相对均一, FeO (1.2–1.9 wt%)、Na2O (1.0–1.8 wt%)、MgO (3.0–3.8 wt%). NWA 8716中主要矿物成分特征如表2所示.表 2 NWA 8716主要矿物成分特征(wt%) Table 2 Representative mineral chemistry (wt%) of NWA 8716Olivine megacryst OlivinePyroxeneMaskelynite Spinel Ilmenitecore mantle rim phenocryst core mantle rimTiO2 ----0.04 0.15 0.150.037.67 52.71FeO 16.15 23.28 27.96 38.12 12.64 13.45 19.05 0.4837.33 41.94SiO2 39.96 38.54 37.33 35.42 55.73 54.17 52.75 53.010.05 0.03MgO 43.26 37.13 33.53 25.49 27.91 25.03 20.29 0.202.20 2.80K2O 0.00 0.02 0.010.000.03 0.02 -0.07--CaO 0.14 0.22 0.210.151.25 3.52 4.79 12.310.00 0.24MnO 0.32 0.41 0.570.640.44 0.44 0.600.010.56 0.54Cr2O3 0.09 0.07 0.030.080.52 0.83 0.380.0143.70 0.44Na2O 0.30 0.31 0.090.020.06 0.47 0.174.71--Al2O3 0.04 0.11 0.000.010.55 1.27 1.35 29.217.59 0.02V2O3 ---Total 100.3 100.1 99.7499.92---99.16 99.34 99.54100.00.59 99.690.53 99.24Mg# 82.7 74.0 68.154.479.7 76.8 65.5---Fs----19.8 21.5 31.0---Wo ----2.5 7.2 10.0---An -------58.9--Or-------0.4--3.3 稀土元素含量特征 橄榄石整体的稀土元素(REE)含量很低( 2 × CI, CI为CI型球粒陨石的REE含量),呈现明显轻稀土(LREE)亏损的特征(La均值为0.01 × CI), 重稀土元素(HREE)由Dy至 Lu逐步富集(Lu均值为1.1 × CI). 粗粒橄榄石斑晶与较小橄榄石斑晶相比HREE含量更 低, 二者平均Lu含量分别约为0.3 × CI和1.7 × CI. 含量最低的部位为粗粒橄榄石斑晶的 富镁核部. 辉石LREE亏损特征明显, 含量由La (均值0.1 × CI)至Gd (均值1.9 × CI)逐36-660 卷吴蕴华等: 火星陨石NWA 8716的岩矿学特征及粗粒橄榄石斑晶的来源4期渐升高, HREE含量由Tb (均值2.2 × CI)至Lu (均值3.2 × CI)则呈现较为平坦的配分模 式. 熔长石Eu正异常特征明显(均值11.8 × CI), 除此之外其余稀土元素含量均非常低, 普遍低于0.2 × CI. 白磷钙矿极度富集稀土元素, La含量为70 × CI、Lu含量为396 × CI, LREE相对亏损, 含量由La至Sm逐渐增高, HREE相对较为平坦, 但由Gd至Lu含量轻微 下降. 在此基础之上Eu呈现较为明显的负异常, Eu/Eu* (Eu* = 0.5 × [Sm+Gd]CI, CI下 标表示该值经过CI球粒陨石含量标准化)值约为0.57. 主要矿物的REE含量以及利用 模式丰度(表1)和矿物平均含量(表3)计算出的全岩REE含量如图5所示. 计算得到NWA 8716全岩(La/Yb)CI值为0.1, 符合一般LREE亏损的辉玻无球粒陨石特征[4], 与含粗粒橄 榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石样品Yamato 980459特征相似[10]. 较小橄榄石斑晶中熔体包裹 体的稀土配分模式与计算的全岩配分模式大致平行, 但含量(La = 1.1 × CI)总体略高于 全岩含量(La = 0.3 × CI), (La/Yb)CI比值为0.06 (图5 (b)).100 (a)101000 (b)100CI-normalized value CI-normalized value1100.110.01PyroxeneOlivine phenocryst Olivine megacryst0.1REE range of pyroxeneMerrillite Calculated bulk rockYamato 9804590.001Maskelynite REE range of olivineMelt inclusion within olivine phenocryst 0.01La Ce Pr Nd Pm Sm Eu Gd Tb Dy Ho Er Tm Yb Lu La Ce Pr Nd Pm Sm Eu Gd Tb Dy Ho Er Tm Yb Lu图 5 NWA 8716中主要矿物与全岩经CI球粒陨石标准化的稀土元素含量. (a)辉石与橄榄石的REE含量范围及辉石、橄 榄石与熔长石的平均REE含量; (b)白磷钙矿、橄榄石斑晶内熔体包裹体以及计算得出的全岩REE含量, 含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石Yamato 980459[10]的成分也标示在图上用于对比.Fig. 5 CI-normalized REE concentration of major minerals and bulk rock of NWA 8716. (a) The REE concentration ranges of pyroxene and olivine, and the average REE concentration of pyroxene, olivine, and maskelynite; (b) REE concentration of merrillite, melt inclusion within olivine phenocryst, and thecalculated bulk rock. Olivine-phyric shergottite Yamato 980459[10] is also shown on the plot for comparison.3.4 粒径统计分析由于在不同的生长速率下形成的晶体颗粒大小与数量特征会有区别, Marsh[20]提 出了利用对矿物结晶颗粒的尺寸分布的统计(Crystal Size Distribution, CSD)来获取岩 浆的动力学或热力学环境信息. 这种统计分析在岩浆岩、 火山岩以及变质岩的研究上 均有应用[20–21]. 并且这种方法也成功用于对部分火星辉玻无球粒陨石结晶过程的研 究[11, 16, 22].36-760 卷表 3 NWA 8716硅酸盐矿物、白磷钙矿以及计算所得全岩稀土元素含量(ppm) Table 3 Rare Earth Element concentrations (ppm) of silicates, merrillite and calculated bulk of NWA 8716Olivine megacryst Olivine phenocrysta.v.a1σaa.v.1σMaskelynite a.v. 1σPyroxene a.v. 1σMerrillitea.v.1σMelt inclusionb Calculated bulkLa 0.001 0.002 0.001 0.003 0.016 0.009 0.014 0.012 16.750 2.1180.2590.079Ce 0.000 0.000 0.003 0.003 0.047 0.010 0.046 0.028 47.783 4.8090.7630.228Pr 0.002 0.001 0.001 0.002 0.003 0.003 0.014 0.009 9.477 1.0520.1890.048Nd 0.006 0.012 0.018 0.041 0.073 0.063 0.079 0.044 73.149 8.3671.5420.356天文学报Sm 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.010 0.017 0.107 0.054 59.457 5.5991.0490.306Eu 0.005 0.008 0.004 0.007 0.684 0.102 0.039 0.017 16.821 1.1370.7100.21636-8Gd 0.020 0.026 0.022 0.025 0.046 0.043 0.389 0.180 129.780 13.2883.2150.774Tb 0.002 0.002 0.003 0.003 0.005 0.002 0.084 0.039 24.528 2.0940.5270.152Dy 0.028 0.040 0.027 0.017 0.026 0.024 0.571 0.209 163.336 14.0354.8711.019Ho 0.004 0.006 0.012 0.007 0.006 0.002 0.151 0.056 34.266 2.6261.0090.233Er 0.027 0.016 0.051 0.013 0.014 0.016 0.455 0.154 89.068 5.6162.9930.648Tm 0.004 0.003 0.015 0.006 0.001 0.002 0.069 0.029 11.598 0.8810.4230.091Yb 0.030 0.026 0.132 0.048 0.000 0.000 0.432 0.207 73.037 5.7683.0220.570Lu 0.008 0.007 0.042 0.013 0.004 0.004 0.080 0.040 10.052 0.5780.4060.093a a.v. represents average, and 1σ represents standard deviation b Melt inclusion presents within olivine phenocryst4期60 卷吴蕴华等: 火星陨石NWA 8716的岩矿学特征及粗粒橄榄石斑晶的来源4期对于非等轴晶系的晶体来说, 对颗粒长轴的统计会由于晶体取向的差异而发生较 大的变化, 因此对宽度的统计更具有代表性. 利用背散射图像对NWA 8716中所有橄榄 石颗粒的大小进行统计, 可以看出颗粒宽度分布特征如图6 (a)所示, 有87%的颗粒粒径 集中于0–400 µm区间, 其中颗粒数量最多的区间为0–50 µm, 约占30%, 其余颗粒的宽度 为500 µm–1.2 mm不等, 数量分布并不连续. 通过计算dNV /dL(NV 为单位体积内颗粒 数量, L为颗粒大小)可以获得颗粒数量密度n, 从数量密度和粒径大小的相关性可以得 出CSD分布特征, 见图6 (b)所示, 计算过程参考文献[23]. 在0–400 µm区间颗粒数量密 度与颗粒宽度大致呈负相关, 而在颗粒宽度稍大的区间颗粒数量密度断续分布并大致呈 水平趋势.6(a)(b)30254Number of grains ln (n /mm−4)20 21510050 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 Grain size /mm−2 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 Grain size /mm图 6 NWA 8716中橄榄石粒径(宽度)特征. (a)橄榄石数量与粒径分布直方图; (b)橄榄石粒径分布特征(CSD)图.Fig. 6 Characteristics of olivine grain size (width) in NWA 8716. (a) Histograms of number of olivine versus grain size; (b) Crystal size distribution (CSD) diagram of olivine.4 讨论4.1 橄榄石斑晶来源从粒径分布分析结果可以看出, 橄榄石粒径分布并不是单一的线性关系. 在粒径较 小的范围内(< 400 µm), 粒径分布特征较为符合线性关系, 说明橄榄石曾在相对稳定的 环境下连续结晶生长; 在粒径较大的范围内颗粒数量密度有所上升. 这种偏离单一线性 分布的特征表明样品在结晶过程中发生了结晶环境的变化, 反映粒径较大的橄榄石斑晶 应当具有堆晶成因[22]. 这部分堆晶可能形成于样品结晶的原始母岩浆中[10, 16]; 也可能 来源于成分不同的其他岩浆, 或者由于混入带有斑晶的外部熔体导致[11]. NWA 8716粒 径分布特征与SaU 005较为相似[11], 但在粒径最小的区域并没有如SaU 005中呈现的颗 粒数量明显降低的现象, 说明NWA 8716在此期间的结晶环境相对更为稳定.从成分特征来看, 样品中的粗粒橄榄石斑晶核部成分相对较为均一(图3), 与LAR 06319中粗粒橄榄石斑晶成分特征相似, 从幔部开始铁含量增加, 说明粗粒橄榄石斑晶 内部可能经历过一定程度的再次平衡过程[24]. 并且粗粒橄榄石斑晶成分与较小橄榄石 斑晶成分具有差异, Fo值并不连续, 可能表明形成粗粒橄榄石斑晶的母岩浆成分与其余 相的母岩浆成分具有一定差异. 此外, 在讨论样品结晶过程时, 常用的方法是利用元素 分配系数计算出与矿物平衡的原始熔体成分, 如果熔体成分与全岩成分一致, 则说明结36-960 卷天文学报4期晶过程中没有明显外部物质加入. NWA 8716中最为富镁的粗粒橄榄石斑晶核部成分约 为Fo82.7, 基于橄榄石结晶过程铁-镁分配特征, 分配系数取Kd = 0.35[25], 计算获得与之 平衡的原始熔体中Mg#值为62.6, 与全岩Mg#值(约70)不一致, 但与SaU 005等样品相 比, 成分偏差不大(图7 (a)). 所以粗粒橄榄石斑晶来源的熔体可能与NWA 8716母岩浆 成分相近.Bulk Mg# CI-normalized value80 (a) Kd=0.35 NWA 871670Yamato 980459NWA 5789DaG 476 SaU 005RBT 0426160LAR 06319NWA 1068Dhofar 0191000 (b)10010501Kd=0.30NWA 2990Olivine megacryst (Mg#=82.1) Olivine phenocryst (Mg#=57.1)Bulk rockPyroxene core (Mg#=74.5)400.190 85 80 75 70 65 60 55La Ce Pr Nd PmSm Eu Gd Tb Dy Ho Er Tm Yb LuFo of olivine core图 7 原始熔体成分特征. (a)粗粒橄榄石斑晶核部Fo值与全岩Mg#值相关性, 参考曲线及其他含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无 球粒陨石样品成分数据来自文献[25]. 在分配系数Kd = 0.35曲线上的样品能够代表原始熔体成分(Yamato 980459、 NWA 5789、NWA 2990), NWA 8716偏离该曲线; (b)计算所得与富镁的粗粒橄榄石斑晶、较小橄榄石斑晶和辉石核部平衡的原始熔体REE成分与全岩成分对比.Fig. 7 Chemical signatures of primary melt. (a) The correlation of Fo content of olivine core and bulk Mg#. The reference curves and composition of other olivine-phyric shergottites are adopted from Ref.[25]. Samples plotted on the curve of Kd = 0.35 may represent primary melt compositions (Yamato 980459, NWA 5789, and NWA 2990), but NWA 8716 is deviated from this curve; (b) Calculatedcomposition of parent melt in equilibrium with Mg-rich cores of olivine megacryst and phenocryst, and pyroxene compared to bulk rock composition.计算得到的与粗粒橄榄石斑晶、 较小橄榄石斑晶以及富镁辉石斑晶平衡的原始熔 体成分如图7 (b)所示, 其中橄榄石REE分配系数取自Dunn和Sen[26], 低钙辉石分配系数 为Lundberg等[27]根据McKay等[28]中的参数与计算方法经过辉石Wo值修正后得到. 计 算得到的原始熔体REE含量均与全岩成分特征存在差异, 进一步证明NWA 8716并不形 成于一个封闭系统. 部分粗粒橄榄石斑晶较为破碎的外形可能正是由于捕掳过程导致.4.2 与其他辉玻无球粒陨石对比橄榄石、长石、辉石成分与其他部分辉玻无球粒陨石的成分对比如图8及图4 (a)所 示. 橄榄石成分与LAR 06319和EETA 79001A较为相似, 且靠近Yamato 980459中的 富镁端元. 但NWA 8716粗粒橄榄石斑晶与较小斑晶间成分不连续, 而在LAR 06319样 品中, 粗粒橄榄石斑晶与较小斑晶成分有重叠区域(图8 (a)). NWA 8716中不存在 如Yamato 980459以及NWA 5789中出现的填隙状辉石[19]. 与LAR 06319[18]和Yamato 980459[9]成分相比, NWA 8716中辉石CaO与MgO含量较低, 接近LAR 06319中辉石核 部成分以及Yamato 980459中辉石核部与幔部成分. 辉石整体成分富镁, 与DaG 476相 近[29]. 橄榄石与辉石均较缺失富铁端元. NWA 8716中的熔长石比LAR 06319与NWA36-1060卷吴蕴华等:火星陨石NWA8716的岩矿学特征及粗粒橄榄石斑晶的来源4期1068中的更富钙,与SaU005相近,靠近含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石中较为富CaO的端元,但成分变化范围更小(图8(b)).Or端元成分低于LAR06319(Or∼1−4),但与DaG476(Or0.3−0.9)相似[16,29].从全岩成分上看,NWA8716较为富镁,且REE含量较低,与DaG476以及SaU005相似[11,29].虽然NWA8716的成分不能完全代表其来源的母岩浆成分,但是从成分特征上看,NWA8716来源于亏损型源区,且演化程度较低.Fo of olivine An of maskelynite图8NW A8716成分与其他辉玻无球粒陨石对比.(a)橄榄石Fo值;(b)熔长石An值.其他辉玻无球粒陨石的成分来源于文献[8–9,11,16–17,30–38].Fig.8The composition of NW A8716compared to other shergottites.(a)The Fo content of olivine;(b) The An content of positions of other shergottites are from Refs.[8–9,11,16–17,30–38].5结论本文通过分析含粗粒橄榄石斑晶辉玻无球粒陨石NWA8716的岩石结构及矿物成分特征,得到如下结论:(1)从橄榄石斑晶的粒径大小及分布特征来看,NWA8716应当经历了两个结晶阶段,首先捕获粒径较大的橄榄石堆晶,然后在相对较稳定的环境下结晶出较小橄榄石斑晶.(2)全岩稀土元素含量较低,且全岩([La/Yb]CI值为0.1)以及较小橄榄石斑晶内熔体包裹体([La/Yb]CI值为0.06)均呈现明显LREE亏损的特征.(3)从粗粒橄榄石斑晶核部的成分与全岩的铁-镁以及稀土元素含量特征关系来看,这种斑晶应当结晶于外部熔体,该熔体与NWA8716母岩浆成分相似.(4)NWA8716的成分并不能完全代表原始熔体成分,但粗粒橄榄石斑晶与寄主岩石成因紧密,仍能反映该样品来源于相对富镁、演化程度较低的亏损型源区.60卷天文学报4期参考文献[1]Agee C B,Wilson N V,McCubbin F M,et al.Science,2013,339:780[2]Goodrich C A.M&PS,2002,37:B31[3]McSween Jr H Y,Treiman A H.Martian Meteorites//Papike J J.Planetary Materials.WashingtonDC:Mineralogical Society of America,1998[4]Papike J J,Karner J M,Shearer C K,et al.GeCoA,2009,73:7443[5]Herd C D K,Borg L E,Jones J H,et al.GeCoA,2002,66:2025[6]Borg L E,Draper D S.M&PS,2003,38:1713[7]Treiman A H,Filiberto J.M&PS,2015,50:632[8]Bridges J C,Warren P H.JGSoc,2006,163:229[9]Mikouchi T,Koizumi E,McKay G,et al.AMR,2004,17:13[10]Usui T,McSween Jr H Y,Floss C.GeCoA,2008,72:1711[11]Goodrich C A.GeCoA,2003,67:3735[12]Hu Z C,Gao S,Liu Y S,et al.Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry,2008,23:1093[13]Hu Z C,Liu Y S,Gao S,et al.Spectrochimica Acta Part B:Atomic Spectroscopy,2012,78:50[14]Liu Y S,Hu Z C,Gao S,et al.ChGeo,2008,257:34[15]Liu Y S,Gao S,Hu Z C,et al.JPet,2010,51:537[16]Sarbadhikari A B,Day J M D,Liu Y,et al.GeCoA,2009,73:2190[17]Taylor L A,Nazarov M A,Shearer C K,et al.M&PS,2002,37:1107[18]Peslier A H,Hnatyshin D,Herd C D K,et al.GeCoA,2010,74:4543[19]Gross J,Treiman A H,Filiberto J,et al.M&PS,2011,46:116[20]Marsh B P,1988,99:277[21]Cashman K V,Marsh B P,1988,99:292[22]Lentze R C F,McSween Jr H Y.M&PS,2000,35:919[23]Higgins M D.AmMin,2000,85:1105[24]Balta J B,McSween H Y.Are Megacrysts in Olivine-Phyric Shergottites Xenocrysts,Phenocrysts,orSomething Else?Proceedings of the42nd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference,The Woodlands, Texas,March7-11,2011[25]Filiberto J,Dasgupta R.E&PSL,2011,304:527[26]Dunn T,Sen C.GeCoA,1994,58:717[27]Lundberg L L,Crozaz G,McSween Jr H Y.GeCoA,1990,54:2535[28]McKay G,WagstaffJ,Yang S R.GeCoA,1986,50:927[29]Zipfel J,Scherer P,Spettel B,et al.M&PS,2000,35:95[30]Barrat J A,Jambon A,Bohn M,et al.GeCoA,2002,66:3505[31]McSween Jr H Y,Jarosewich E.GeCoA,1983,47:1501[32]Steele I M,Smith J V.JGRB,1982,87:A375[33]McSween Jr H Y,Taylor L A,Stolper E M.Science,1979,204:1201[34]Harvey R P,Wadhwa M,McSween Jr H Y,et al.GeCoA,1993,57:4769[35]Mikouchi T,Miyamoto M.AMR,1997,10:41[36]McSween Jr H Y,Eisenhour D D,Taylor L A,et al.GeCoA,1996,60:4563[37]Rubin A E,Warren P H,Greenwood J P,et al.Geology,2000,28:1011[38]Stolper E,McSween Jr H Y.GeCoA,1979,43:147560卷吴蕴华等:火星陨石NWA8716的岩矿学特征及粗粒橄榄石斑晶的来源4期Petrology,Mineralogy and Origin of Olivine Megacrysts of the Martian Meteorite NW A8716WU Yun-hua1,2TANG Chi-pui3MEI Bao3HSU Wei-biao1,3 (1Center for Excellence in Comparative Planetology,Purple Mountain Observatory,ChineseAcademy of Sciences,Nanjing210034)(2University of Chinese Academy of Sciences,Beijing100049) (3The State Key Laboratory of Lunar and Planetary Science,Macau University of Science andTechnology,Macau999078)A BSTRACT Martian meteorites provide direct evidence and critical constraints on the evolution of the Martian mantle.Olivine-phyric shergottites are suggested to carry geochemical information of the primitive Martian mantle.Detailed petrological and mineralogical analyses were made for the NWA(Northwest Africa)8716olivine-phyric shergottite which is composed of large olivine megacrysts(0.5–1.8mm)set in a matrix of relatively small olivine(50–400µm),and pyroxene with interstitial maskelynite,and other accessory minerals.Both the melt inclusion within olivine phenocryst and the calculated bulk rock display an LREE(Light Rare Earth Element)-depleted pattern ([La/Yb]CI0.06to0.1)which is in concordant with some other olivine-phyric shergot-tites.This indicates NWA8716is derived from a depleted Martian magma.The origin of olivine megacrysts is a crucial factor on whether NWA8716can be counted to rep-resent composition of a primitive,mantle-derived magma.The crystal size distribution analysis indicates excesses of large crystals which may be due to the entrainment of cu-mulates.Calculations of Fe-Mg and rare earth element partition reveal that NWA8716 did not crystallize in a closed system.But estimated compositions of the parent melt are not in large discrepancy with what observed,indicating the megacrysts crystallized from a magma similar to its parent melt.NWA8716should have derived from a less evolved depleted reservoir.Key words astrochemistry,meteorites,shergottite。

恒星的演化§主序星的演化1、恒星演化的基本原理:恒星在一生的演化中总是试图处于稳定状态(流体静力学平衡和热平衡)。

当恒星无法产生足够多的能量时,它们就无法维持热平衡和流体静力学平衡,于是开始演化。

引力在其中起了关键的作用。

恒星从星云中诞生,这个结果是引力造成的,因为引力使得星云中的物质聚集成了恒星。

但是另一方面,引力会使得它在体积上不断收缩,为了使得引力作用在某种程度上达到平衡,恒星需要在内部产生能量,产生能量的目的是为了抗衡引力,否则它会持续收缩。

在达到平衡的过程里,恒星要付出代价,恒星要不断消耗自身物质,产生新的元素,元素在转化的过程中能量释放出来,内部结构也会发生变化,最终有一天恒星没有任何能源可以供给,它的生命就结束了。

所以说恒星的一生是一部与引力斗争的历史。

2、Russel-Vogt原理如果恒星处于流体静力学平衡和热平衡,而且它的能量来自内部的核反应,它们的结构和演化就会完全唯一地由初始质量和化学丰度决定。

这个原理在实际上可能不是非常符合,因为恒星的质量会不可避免地发生变化,但是初始质量和化学丰度仍然是决定恒星结构和演化的重要因素。

这里我们主要谈质量的影响。

3、恒星演化时标核时标(Nuclear Timescale):恒星内部通过核心区(约占恒星质量的十分之一)核反应的产能时间。

比如太阳,它并不是把所有的质量都烧光了,它其实只有0.1倍太阳质量作为可用的燃料。

我们有下面的结果:t n=EL=ηΔMc2L≈0.7%0.1Mc2L≈(1010yr)(MM⊙)LL⊙E是它总的能量,L是光度,也就是它能量消耗的速率,E可以写成ΔMc2,,其中ΔM是恒星核心区的质量,并不是恒星的总质量,η是能量转换的效率。

上式是以太阳质量和太阳光度作为单位的。

一旦恒星的核燃料烧光了,它会快速地变化,进入新的平衡状态,新的平衡状态转变的时标比核反应时标要快得多。

热时标(Thermal Timescale):恒星辐射自身热能的时间,或光子从恒星内部到达表面的时间,是指恒星把自身能量或热量全部辐射光了。

恒星的一生作者:傅煜铭来源:《百科探秘·航空航天》2017年第08期任晴朗无云、没有月亮的夜晚,我们抬头仰望星空时,总会被那璀燦的繁星深深震撼。

古时候的人们发现,相对于行星、彗星等位置会变化的天体,天上为数最多的星星相互之间的位置几乎没有改变,于是把它们叫作“恒星”。

现代的天文学家把受自身引力束缚、自己发先发热的由等离子体组成的球状天体叫作恒星。

太阳也是恒星六家庭的一员,是离我们最近的恒星。

实际上,人类真正认识到太阳也是一颗恒星,是最近几百年间的事情。

哥白尼、布鲁诺等科学家作为日心说的开创者,认为地球并非世界的中心,而是绕着太阳旋转的。

同时,他们相信恒星也和太阳一样,只是因为距离遥远,所以看上去只是一个个的亮点。

1838年,德国天文学家弗里德里希·贝塞尔首次通过视差法较为精确地测量了一颗恒星到我们的距离。

在此之后,许多恒星的距离都被测量出来。

科学家们使用观测到的恒星亮度,修正它们所在距离对于亮度的影响(光源距离观测者越远,看上去就会越暗)后,发现这些恒星几乎都和太阳差不多亮!科学家们还通过对比太阳和其他恒星的光谱,证实了它们在表面温度和化学成分上都十分相似。

按照恒星的光谱分类方法,太阳是一颗G2型的主序恒星。

宇宙中一共有多少颗恒星呢?“不计其数”可以说是对这个问题最为准确的回答。

限于我们所处的位置和恒星、星系到我们的距离,我们在夜晚可以用肉眼看到的恒星,几乎全都位于银河系内。

我们的肉眼无法分辨遥远星系中的单个恒星。

因此,许多星系在我们看来都是一个个很小的亮斑或者模糊的小亮点,它们是这些星系所有恒星发光的总和。

粗略地估计一下,我们所能观测到的宇宙中有大约千亿个银河系这样的星系,而每一个这样的星系中,又有数千亿颗恒星,宇宙中恒星的数目是多么巨大!这些恒星从何处来,又将到何处去?一颗普通的恒星——这个在宇宙中沧海一粟般的平凡存在,究竟又会演绎出何等波澜壮阔的诗篇?恒星诞生记——我们来自星尘近代的康德和拉普拉斯提出了“星云说”来解释太阳系的形成,“星云说”认为太阳系内的天体诞生于原始星云中。

1泡利不相容原理具体指的是同一体系内的任意两个()不可能有完全相同的运动状态。

(1.0分)1.0?分•A、电子•B、质子•C、中子•D、原子核我的答案:A2花样滑冰运动员在冰上旋转时,哪种动作可以获得更快的转速?()(1.0分)1.0?分•A、下蹲和直立、双臂向上双腿向下并拢•B、下蹲和单足点地,其余三肢全部横向伸展•C、张开双臂和直立、双臂向上双腿向下并拢•D、张开双臂和单足点地,其余三肢全部横向伸展我的答案:A3中国古人记载的公元185年超新星爆发的文字中,有可能反映了恒星化学组成的变化的语句是()。

(1.0分)1.0?分•A、客星出南门中•B、大如半筵•C、五色喜怒•D、至后年六月消我的答案:C4太阳的寿命预计还有()亿年。

(1.0分)1.0?分•A、46•B、50•C、100•D、700我的答案:B5理论上应该出现的在各个不同波段,辐射强度分布的情况,这种分布被称为( )。

(1.0分)1.0?分•A、正太分布•B、普朗克分布•C、t分布•D、泊松分布我的答案:B6黑洞二字分别指的是()。

(1.0分)1.0?分•A、这个天体是黑色的和天体存在洞穴结构•B、这个天体是黑色的和所有的物质在视界内都往中心奇点坠落•C、任何电磁波都无法逃出这个天体和天体存在洞穴结构•D、任何电磁波都无法逃出这个天体和所有的物质在视界内都往中心奇点坠落我的答案:D7以下哪位华裔科学家对暗物质探索的贡献最大?()(1.0分)1.0?分•A、杨振宁•B、李政道•C、丁肇中•D、朱棣文我的答案:C8太阳系的6重物质界限中,没有太“大块”的天体物质的是哪一重?()(1.0分)1.0?分•A、小行星带•B、柯伊伯带•C、奥尔特云•D、太阳风的最远范围我的答案:C9暗物质的特征不包括()。

(1.0分)1.0?分•A、总量比亮物质多10倍以上•B、不发出任何辐射,但存在引力•C、质量大,寿命长,作用弱•D、主体应该是已知重粒子以外的物质我的答案:A10银河在星空中的“流域”没有涵盖哪个星座?()(1.0分)1.0?分•A、天鹅座•B、天蝎座•C、南十字座•D、狮子座我的答案:B11假如冥王星上有智慧生命,则“他们”对飞掠而过的“新视野”号做出的反应可能会是()。

67

特殊光谱

有一些罕用的光谱分类,只适用在少数的恒星上:

W:25000~50000K - 沃夫-瑞叶星。

L:1,500 - 2,000 K – 恒星的质量不足以让氢的核聚变持续进行的棕矮星。L代表锂,在恒

星内会很快的蜕变。

T:1,000 K – 比棕矮星温度更低的恒星,在光谱中有甲烷的谱线。

C:碳星.

R:以前是光谱中有碳星谱线的K型恒星。

N:以前是光谱中有碳星谱线的M型恒星。

S:原本是M型的恒星,但正常的氧化锑谱线被氧化锌谱线取代。

D:白矮星,例如,天狼 B

白矮星的分类

D 代表的是白矮星,为低质量恒星在结束它们生命时的终点。白矮星的光谱可以细分为DA, DB,

DC, DO, DX, DZ, 和DQ。要注意的是附加的字母并不是用在恒星本身,只是在说明在白矮星外

围大气层的状况。

白矮星的分类如下:

DA:外围或大气层有丰富的氢,光谱中有巴尔曼系列的谱线。

DB:外围或大气层有丰富的氦,光谱中有中性氦原子的谱线。

DO:光谱以氦离子谱线为主,也可能有微弱的氢与氦原子谱线。

DQ:外围或大气层有丰富的碳,光谱中有碳原或分子的谱线。

DZ:外围或大气层有丰富的金属,光谱中有钙离子的谱线。

DC:光谱中没有上述各型特征的谱线,也就是说光谱几乎是连续光谱。

DX:谱线的特征不明确,不能确切分类的。

A,B,O,Q等谱线的特征如果出现在同一颗白矮星的光谱中,也可以同时列出。

【单选题】以太阳为中心,从内到外地球的位置在太阳系中排第几位? 答案:3A、5B、4C、3D、2【单选题】下列哪一颗行星是太阳系中体积最大的行星?答案:木星A、金星B、火星C、地球D、木星【判断题】夏季大三角包括织女星、牛郎星和天津四。

答案:√【判断题】在地球上,人类无法通过肉眼直接观测到人造卫星。

答案:×【单选题】“知七政谓日月与五星也”这句话出自于哪一本著作?答案:《尚书》A、《尚书》B、《春秋》C、《论语》D、《孟子》【单选题】在古代中国,火星在哪个星之间徘徊被认为是大凶的天象? 答案:帝星A、木星B、水星C、帝星D、谷神星【判断题】行星的逆行使得地球中心说收到了很大的挑战。

答案:√【单选题】创立日心说的是下列哪一位人物?答案:尼古拉·哥白尼A、尼古拉·哥白尼B、伽利略C、牛顿D、达尔文【多选题】下列哪些关于开普勒定律的内容描述是√ 的?答案:行星沿着椭圆轨道运行|| 相等时间内,行星运动扫过的面积是相等的A、行星沿着正圆轨道运行B、行星沿着椭圆轨道运行C、相等时间内,行星运动扫过的面积是不相等的D、相等时间内,行星运动扫过的面积是相等的【判断题】伽利略是利用望远镜观察天体取得大量成果的第一人。

答案:√【多选题】下列哪几个定律成功解释了开普勒定律?答案:万有引力定律|| 牛顿运动定律A、牛顿运动定律B、万有引力定律C、奇点定律D、以上选项都是【判断题】牛顿是英国著名的物理学家,提出万有引力定律、牛顿运动定律等。

答案:×【单选题】目前发现的小行星带中最大的一颗天体是()。

答案:谷神星A、天王星B、海王星C、谷神星D、木星【单选题】下列选项中哪一项关于地球,谷神星,月球之间质量大小比较是√ 的? 答案:地球>月球>谷神星A、谷神星>地球>月球B、谷神星=地球>月球C、地球>谷神星>月球D、地球>月球>谷神星【判断题】小行星带处于木星与火星轨道之间。

银河系铝元素丰度研究马文娟; 李宏杰; 张波【期刊名称】《《天文学报》》【年(卷),期】2019(060)005【总页数】7页(P15-21)【关键词】恒星:银河系; 元素:铝元素; 恒星:元素丰度【作者】马文娟; 李宏杰; 张波【作者单位】沧州师范学院物理与信息工程学院沧州 061001; 河北科技大学理学院石家庄 050018; 河北师范大学物理科学与信息工程学院石家庄 050024【正文语种】中文【中图分类】P1441 引言自然界中的许多元素都来自于恒星,宇宙中恒星既有单星,也有很多由于引力作用聚在一起,形成双星、聚星甚至星团,例如球状星团.通常,球状星团中的大多数恒星比较年老.星系是比星团更大的恒星系统,包含椭圆星系、旋涡星系、棒旋星系和不规则星系等多种形态[1].银河系是旋涡星系,从内而外分为核球、银盘和银晕,银盘又可细分为薄盘和厚盘,银河系包含了大约两千亿颗恒星[2–6].恒星中某种元素的多少用“丰度”来表示,某一元素X的丰度定义为包含1012个氢原子的物质中所含元素X原子个数ε(X)的对数值,即lg ε(X)=lg(NX/NH)+12,式中NX为恒星中元素X的原子个数, NH为恒星中元素H的原子个数.恒星中元素X、Y的丰度比定义为[X/Y]=lg(NX/NY)∗ − lg(NX/NY)⊙,式中下标“∗”代表恒星,“⊙”代表太阳.银河系形成早期诞生的恒星的金属丰度(通常用[Fe/H]表示)很低,称为极贫金属星[6–7],一般分布在银晕,而形成时间比较晚的恒星则是金属丰度较高的富金属星,研究不同恒星的元素丰度可以为探索星团和星系化学演化提供重要线索.铝元素为奇Z (质子数)元素,其天体物理来源非常复杂,研究不同恒星系统中铝元素的增丰情况可以为探索铝元素的天体物理来源提供参考.随着观测技术的不断进步和发展,恒星元素丰度的观测数据越来越丰富[2–13],为系统研究元素天体物理来源提供了观测依据.天文观测发现某些恒星系统中铝元素和镁元素、钠元素丰度之间有相关性[14–16],同一星团内的恒星之间铝、镁、钠等轻元素的丰度存在差异,不同星团之间铝元素丰度的差异可以很大,即元素丰度存在离散.本文对银河系不同恒星中铝元素的观测丰度、铝元素与其他元素相对丰度进行系统分析,研究了银河系中不同恒星铝元素丰度的特点以及铝元素丰度随恒星金属丰度的变化趋势; 分析讨论了银河系恒星[Al/Fe]与[Mg/Fe]、[Na/Fe]的相关性.2 银河系恒星中铝元素丰度随金属丰度的变化趋势为探求恒星铝元素丰度随恒星金属丰度的变化特点,我们收集了包括银河系薄盘星、厚盘星、核球恒星、晕星和7个球状星团恒星在内的600余颗恒星观测数据.恒星中元素丰度的确定会受非局域热动平衡(NLTE)效应的影响,尤其对贫金属恒星而言,这种效应比较大[4–5,17].NLTE效应对不同元素的影响是不一样的,比如对Na和对Mg、Al的影响不同[4–5],所以我们对薄盘、厚盘和晕星做了局域热动平衡(LTE)和NLTE丰度之间的对比.对于星团恒星,能够做LTE和NLTE丰度对比的观测结果比较少,且大部分球状星团恒星的元素丰度是基于LTE的,所以7个球状星团的恒星丰度都采用了LTE丰度,没有做LTE和NLTE丰度的比较.所选银河系薄盘、厚盘、核球、晕星、球状星团中样本星的[Al/Fe]随恒星金属丰度[Fe/H]的变化如图1所示.其中银河系薄盘星元素丰度的观测数据取自文献[2–5],共221颗星; 厚盘星元素丰度观测数据取自文献[3–5],共有126颗星; 晕星中元素丰度取自文献[3–6],共有76颗星;核球恒星元素丰度取自文献[7–8],共有25颗星;球状星团M4中恒星元素丰度取自文献[9],共12颗星; 星团M5中恒星元素丰度取自文献[10],共16颗星; 星团M3中恒星元素丰度取自文献[11],共21颗星; 星团M22中恒星元素丰度取自文献[12],共35颗星; 星团NGC 6139中恒星元素丰度取自文献[13],共45颗星; 星团NGC 4833中恒星元素丰度取自文献[14],共27颗星; 星团NGC 2808中恒星元素丰度取自文献[14],共42颗星.为了方便比较,图中用实线表示[Al/Fe]=0.由图中观测数据分析得出:(1)对比图1 (a)和图1 (b),薄盘恒星的[Al/Fe]NLTE明显高于[Al/Fe]LTE,[Al/Fe]NLTE的离散约为0.8 dex,比[Al/Fe]LTE的离散(约为0.6 dex)稍大.从图1 (a)和图1 (b)中都可以看到随着[Fe/H]增大,[Al/Fe]的值缓慢下降,但恒星HD73087的[Al/Fe]极度超丰([Fe/H]= −0.11,[Al/Fe]=1.3),其原因还有待进一步研究.薄盘星[Al/Fe]离散小,主要是因为随着银河系演化,各种金属元素不断增丰,星际介质混合趋于均匀; 由于Ia型超新星对Fe元素的贡献逐渐增大导致薄盘恒星[Al/Fe]随[Fe/H]的变化趋势逐渐减弱[18].(2)对比图1(c)和图1(d)可以看出,得到的厚盘星的[Al/Fe]NLTE明显高于[Al/Fe]LTE.对厚盘星来说,不论是[Al/Fe]NLTE还是[Al/Fe]LTE,其平均值都比薄盘星高,离散也比薄盘星稍大.当[Fe/H]在−1.2到−0.5之间时,[Al/Fe]LTE随[Fe/H]的变化趋势比较平坦,但当[Fe/H]在−0.5到0.2之间时,[Al/Fe]LTE略有下降,[Al/Fe]NLTE则无明显变化.恒星HIP74033的[Al/Fe]LTE呈现超丰的反常现象([Fe/H]= −0.85,[Al/Fe]LTE=1.6).厚盘星的[Al/Fe]在金属丰度比较高时略有下降,也有Ia型超新星对银河系盘星Fe元素的贡献逐渐增多的因素; 而变化趋势整体较平缓说明在Fe元素增丰的同时Al元素的增丰也有较大提高,使得Al元素和Fe元素的增丰比例比较接近.图1 银河系薄盘、厚盘、核球、晕星、球状星团恒星中[Al/Fe]随着[Fe/H]的变化.其中银河系薄盘星数据取自文献[2–5],分别用黑色、红色、蓝色、洋红色三角表示.厚盘星数据取自文献[3–5],分别用红色、蓝色、洋红色五星表示.晕星数据取自文献[3–6],分别用红色、蓝色、洋红色、黑色菱形表示.核球恒星数据取自文献[7–8],分别用红色和黑色方块表示.球状星团中M4、M5、M3、M22、NGC 6139数据取自文献[9–13],分别用黑色、红色、蓝色、橄榄绿、橙色圆点表示; NGC 4833、NGC 2808数据取自文献[14],分别用洋红色、紫色圆点表示.Fig.1 [Al/Fe]of Galactic thin disc,thick disc,bulge,halo,and the globular cluster stars as a function of[Fe/H].Thin disk stars from Refs.[2–5]are shown asblack,red,blue,and magenta triangles,respectively.Thick disk stars from Refs.[3–5]are shown as red,blue,and magenta stars,respectively.Halo stars from Refs.[3–6]are shown as red,blue,magenta,and blackdiamonds,respectively.Bulge stars from Refs.[7–8]are shown as red and black squares,respectively.Globular cluster M4,M5,M3,M22,and NGC 6139 stars from Refs.[9–13]are shown as black,red,blue,olive,and orange filled circles,respectively.NGC 4833,and NGC 2808 stars from Ref.[14]are shown as magenta and purple filled circles,respectively.(3)晕星的[Fe/H]分布范围比较大,从−3.8一直到−0.5.从图1 (e)和图1 (f)可以看出[Al/Fe]LTE和[Al/Fe]NLTE随着[Fe/H]的增大稍有上升趋势.文献[6]给出的28颗极贫金属晕星的[Al/Fe](图1 (e)中黑色菱形)整体比盘星和核球恒星的[Al/Fe]低很多,平均值约为−0.8,但是离散较大,约为0.6 dex,这说明在金属丰度很低的情况下,大质量星对星际介质贡献的Fe元素相对于Al元素的比例比金属丰度较高情况下的比例要高.(4)从图1 (g)可以看出,核球样本恒星的[Fe/H]在−1.3到0.7之间变化,其中[Fe/H] >−0.3时[Al/Fe]略有下降,[Fe/H]在0.2到0.6之间时[Al/Fe]有一些离散,约为0.4 dex.(5)从图1 (h)可以看出,球状星团M4恒星的[Fe/H]从−1.3到−1.1,差别只有0.2 dex,平均值为−1.23.球状星团M5恒星的[Fe/H]从−1.82到−1.28,有0.54 dex的差别,平均值为−1.49.M4中恒星的[Al/Fe]从0.63到0.84,离散很小,仅为0.2 dex.M5中恒星的[Al/Fe]从−0.12到0.7,离散较大,有0.8 dex.对于铝元素丰度来说,M4的离散明显小于M5的离散,尽管M4和M5的金属丰度比较接近,但M5的演化特点显然与M4不同,M4离散小,是典型球状星团的演化特征.另外,M4和M5两个球状星团恒星与厚盘星相比其[Al/Fe]比厚盘星稍大.M3和NGC 6139有相近的[Al/Fe]和[Fe/H],[Al/Fe]离散较大,随[Fe/H]无明显变化趋势.M22与M3和NGC 6139有相近的[Al/Fe]的丰度比,但M22的[Fe/H]比这两个星团低,而且[Fe/H]的离散比M3和NGC 6139大.NGC 4833的金属丰度比NGC 2808低,但它们的[Al/Fe]比较接近,而且NGC 2808的[Al/Fe]有随[Fe/H]的增大下降的趋势,说明该球状星团的丰度可能有Ia型超新星的贡献,这在其他6个球状星团中未见.3 银河系恒星[Al/Fe]和[Mg/Fe]、[Na/Fe]的相关性分析3.1 银河系恒星[Al/Fe]和[Mg/Fe]的相关性为研究银河系各恒星系统中[Al/Fe]和[Mg/Fe]的相关性,图2给出了银河系中薄盘、厚盘、银晕、核球以及球状星团中恒星的[Al/Fe]随[Mg/Fe]的变化,图中各符号含义与图1相同.由图2可见,LTE和NLTE对[Mg/Fe]的影响不太大,远小于对[Al/Fe]的影响.薄盘恒星[Al/Fe]NLTE随着[Mg/Fe]的增大从−0.1缓慢上升到0.54,厚盘恒星的[Al/Fe]也随[Mg/Fe]的增大而增大.对于晕星,文献[3](图中红色菱形)和文献[6](图中黑色菱形)中样本星虽然[Fe/H]不同,文献[3]中−1.5<[Fe/H]<−0.5,文献[6]中−3.8<[Fe/H]<−2.4,但它们[Al/Fe]的变化趋势相同,都是随[Mg/Fe]增大呈现明显上升趋势,即样本星中[Al/Fe]与[Mg/Fe]正相关.核球恒星中[Al/Fe]随[Mg/Fe]增大呈现明显上升趋势(从0.02到0.47),这表明薄盘、厚盘、银晕、核球中恒星的[Al/Fe]和[Mg/Fe]呈正相关性.Carretta等[15]与Pancino等[14]对球状星团的[Al/Fe]与[Mg/Fe]的相关性进行了研究,他们认为[Al/Fe]与[Mg/Fe]反相关出现在贫金属球状星团和大质量的富金属球状星团之中.从图中可见,NGC 4833([Fe/H]~−2.0)和NGC 2808([Fe/H]~−1.1)的[Al/Fe]与[Mg/Fe]反相关,其他星团的[Al/Fe]与[Mg/Fe]未见明显相关性,这与Carretta等[15]、Pancino等[14]的研究结论一致.图2 银河系薄盘、厚盘、核球、晕星、球状星团恒星中[Al/Fe]随着[Mg/Fe]的变化Fig.2 [Al/Fe]of Galactic thin disc,thick disc,bulge,halo,and the globular cluster stars as a function of[Mg/Fe]3.2 银河系恒星[Al/Fe]和[Na/Fe]的相关性图3给出了银河系中薄盘、厚盘、核球、银晕以及球状星团中恒星的[Al/Fe]随[Na/Fe]的变化情况,图中各符号含义与图1相同,除了图3 (h)中NGC 4833 (丰度取自文献[16],用洋红色圆圈表示)和NGC 2808 (丰度取自文献[15],用紫色圆圈表示).由图分析,薄盘星和厚盘星的[Al/Fe]随[Na/Fe]的增大呈现上升趋势,即[Al/Fe]和[Na/Fe]有正相关性,但核球恒星中[Al/Fe]与[Na/Fe]未见明显相关性.对薄盘星和厚盘星,NLTE和LTE两种情况的[Al/Fe]随[Na/Fe]的变化趋势一样.晕星情况较为复杂,对极贫金属晕星(−3.8 < [Fe/H] < −2.4),[Al/Fe]LTE与[Na/Fe]LTE未见明显相关性,而金属丰度较高的晕星(−1.5 < [Fe/H] < −0.5),其[Al/Fe]LTE与[Na/Fe]LTE 表现出明显正相关,[Al/Fe]NLTE与[Na/Fe]NLTE始终表现出明显正相关.除了M4恒星的[Al/Fe]随[Na/Fe]的变化比较缓慢以外,其他球状星团的[Al/Fe]与[Na/Fe]都有明显正相关性.图3 银河系薄盘、厚盘、核球、晕星、球状星团恒星中[Al/Fe]随着[Na/Fe]的变化Fig.3 [Al/Fe]of Galactic thin disc,thick disc,bulge,halo,and the globular cluster stars as a function of[Na/Fe]4 结论研究各种恒星系统中Al元素丰度的增丰特点可为探索恒星、星团和星系化学演化提供重要线索.基于银河系不同恒星Al元素的观测丰度分析,本文研究了银河系中不同恒星[Al/Fe]随恒星金属丰度的变化,并对[Al/Fe]与[Mg/Fe]和[Na/Fe]的相关性做了探讨.(1)对于银河系薄盘、厚盘和核球恒星,[Al/Fe]随[Fe/H]变化的趋势相似,表现为[Al/Fe]随[Fe/H]的增加而缓慢下降,在[Fe/H]等于零时,[Al/Fe]约为零.但与场星不同,球状星团M4和M5都具有局域性演化特征,[Al/Fe]不随[Fe/H]变化呈现缓慢下降趋势,这暗示Ia超新星对M4和M5元素增丰的贡献可能比较小.(2)薄盘、厚盘、核球以及银晕恒星的[Al/Fe]和[Mg/Fe]都呈现正相关性.而球状星团NGC 4833和NGC 2808的[Al/Fe]与[Mg/Fe]反相关,其他星团未见明显相关性.(3)薄盘星和厚盘星的[Al/Fe]和[Na/Fe]有正相关性.核球恒星中[Al/Fe]与[Na/Fe]未见明显的相关性.对于晕星,−3.8<[Fe/H]<−2.4的极贫金属晕星中[Al/Fe]与[Na/Fe]未见明显相关性,而−1.5 < [Fe/H] < −0.5的较高金属丰度晕星中[Al/Fe]和[Na/Fe]有明显正相关性.除了M4恒星的[Al/Fe]随[Na/Fe]的变化比较缓慢以外,其他球状星团的[Al/Fe]与[Na/Fe]都有明显正相关性.(4)对薄盘星和厚盘星,[Al/Fe]NLTE明显高于[Al/Fe]LTE,但没有明显改变[Al/Fe]随[Fe/H]、[Mg/Fe]和[Na/Fe]的变化趋势.极贫金属晕星的[Al/Fe]LTE与[Na/Fe]LTE 未见明显相关性,而金属丰度较高的晕星的[Al/Fe]LTE与[Na/Fe]LTE表现出明显正相关,[Al/Fe]NLTE与[Na/Fe]NLTE始终表现出明显正相关.参考文献【相关文献】[1]向守平.天体物理概论.合肥: 中国科学技术大学出版社,2008: 195-212[2]Reddy B E,Tomkin J,Lambert D L,et al.MNRAS,2003,340: 304[3]Reddy B E,Lambert D L,Prieto C A.MNRAS,2006,367: 1329[4]Gehren T,Liang Y C,Shi J R,et al.A & A,2004,413: 1045[5]Gehren T,Shi J R,Zhang H W,et al.A & A,2006,451: 1065[6]Lai D K,Bolte M,Johnson J A,et al.ApJ,2008,681: 1524[7]Bensby T,Ad´en D,Mel´endez J,et al.A & A,2011,533: A134[8]Bensby T,Feltzing S,Johnson J A,et al.A & A,2010,512: A41[9]Yong D,Lambert D L,Paulson D B,et al.ApJ,2008,673: 854[10]Lai D K,Smith G H,Bolte M,et al.AJ,2011,141: 62[11]Sneden C,Kraft R P,Guhathakurta P,et al.AJ,2004,127: 2162[12]Marino A F,Sneden C,Kraft R P,et al.A & A,2011,532: A8[13]Bragaglia A,Carretta E,Sollima A,et al.A & A,2015,583: A69[14]Pancino E,Romano D,Tang B,et al.A & A,2017,601: A112[15]Carretta E,Bragaglia A,Gratton R,et al.A & A,2009,505: 139[16]Carretta E,Bragaglia A,Gratton R G,et al.A & A,2014,564: A60[17]Nordlander T,Lind K.A & A,2017,607: A75[18]Maeda K,Ropke F K,Fink M,et al.ApJ,2010,712: 624。

a rXiv:as tr o-ph/1654v131Oct2The Progenitor Masses of Wolf-Rayet Stars and Luminous Blue Variables Determined from Cluster Turn-offs.II.Results from 12Galactic Clusters and OB Associations Philip Massey 1,2Kitt Peak National Observatory,National Optical Astronomy Observatory 3P.O.Box 26732,Tucson,AZ 85726-6732massey@ Kathleen DeGioia-Eastwood 4and Elizabeth Waterhouse 4,5Department of Physics and Astronomy,Northern Arizona University P.O.Box 6010,Flagstaff,AZ 86011-6010.kathy.eastwood@ waterh@ ReceivedABSTRACTIn a previous paper on the Magellanic Clouds we demonstrated that coeval clusters provide a powerful tool for probing the progenitor masses of Wolf-Rayet stars(W-Rs)and Luminous Blue Variables(LBVs).Here we extend this work to the higher metallicity regions of the Milky Way,studying12Galactic clusters. We present new spectral types for the unevolved stars and use these,plus data from the literature,to construct H-R diagrams.Wefind that all but two of the clusters are highly coeval,with the highest mass stars having formed over a period of less than1Myr.The turn-offmasses show that at Milky Way metallicities some W-Rs(of early WN type)come from stars with masses as low as20–25M⊙. Other early-type WNs appears to have evolved from high masses,suggesting a large range of masses evolve through an early-WN stage.On the other hand, WN7stars are found only in clusters with very high turn-offmasses,>120M⊙. Similarly the LBVs are only found in clusters with the highest turn-offmasses, as we found in the Magellanic Clouds,providing very strong evidence that LBVs are a normal stage in the evolution of the most massive stars.Although clusters containing WN7s and LBVs can be as young as1Myr,we argue that these objects are evolved,and that the young age simply reflects the very high masses that characterize the progenitors of such stars.In particular we show that the LBVηCar appears to be coeval with the rest of the Trumpler14/16complex. Although the WCs in the Magellanic Clouds were found in clusers with turn-offmasses as low as45M⊙,the three Galactic WCs in our sample are all found in clusters with high turn-offmasses(>70M⊙);whether this difference is significant or due to small-number statistics remains to be seen.The BCs of Galactic W-Rs are hard to establish using the cluster turn-offmethod,but are consistent with the“standard model”of Hillier.Subject headings:open clusters and associations:individual—stars:early-type—stars:evolution—stars:Wolf-Rayet1.Introduction1.1.BackgroundMassive,luminous stars begin their H-burning lives as hot,O-type stars.During their main-sequence evolution(2.5–8Myr for stars with initial masses of120–20M⊙)they may lose a significant amount of their mass due to strong stellar winds.The observed mass-loss rates suggest that the highest-mass stars will lose as much as half their mass during the H-burning stage.Since these winds are driven by radiation pressure through highly-ionized metal lines,the mass-loss rates will increase with stellar luminosity,metallicity,and effective temperature.It was Conti(1976)whofirst suggested that mass-loss provided a simple explanation for how Wolf-Rayet(W-R)stars form.In the modern version of the“Conti scenario”(Maeder&Conti1994),this mass loss results in a stripping offof the H-rich outer layers of the star,resulting in a WN-type W-R star,in which the H-burning products(He and N)are enriched at the surface,with strong,broad emission lines indicative of enhanced stellar winds forming an extended atmosphere.Most WNs are presumed to be He-burning objects,although there is evidence that a few H-rich late-type WNs are still near the end of the core-H burning phase(Conti et al.1995).Further mass-loss and evolution reveals the products of He-burning(C and O)at the surface,and the star is spectroscopically identified as a WC-type W-R.Possibly the highest mass stars also go through a Luminous Blue Variable(LBV)stage on their way to becoming W-Rs,with the large,episodic mass loss that characterizes LBVs aiding the process.Stars of slightly lower luminosity(mass)will not have an LBV phase,but recent observations(Massey1998a)suggest that they do go through an intermediate red supergiant(RSG)phase,even at high metallicities,albeit for a short time.At some lower luminosity one expects that the mass-loss rates are sufficient to produce a WN-type W-R,but not a WC.And,at even lower luminosities,mass-loss rates are so low that the He-burning stage is spent entirely as a red supergiant(RSG)and not as a W-R star.In this version of the“Conti scenario”we thus might expect the following“paths”to be followed,in order of decreasing luminosities:O−→LBV−→WN−→WC(1)O−→RSG−→WN−→WC(2)O−→RSG−→WN(3)OB−→RSG(4)The masses corresponding to these paths are unknown(and indeed we are unsure even of the qualitative correctness of these paths),but“standard guesses”for characteristic values would be1:≥80M⊙,2:60M⊙,3:40M⊙,and4:20M⊙.We emphasize that these are purely speculative values,and that the actual ranges should depend upon metallicity. Indeed it is to address this issue that the present series of papers has come about.Between the initial O-type stage(of luminosity class“V”)and the He-burning stage (LBVs,W-Rs,RSGs)the star will become a B-type supergiant;most,but not all,of these are expected to still be H-burning objects(Massey et al.1995b).The luminousA-F supergiants are very short-lived intermediate stages during He-burning for stars of intermediate high-mass,depending upon the metallicity.The precursor to SN1987A is believed to have been a“second-generation”B-type supergiant,a He-burning object of somewhat lower mass than those being discussed here.In addition to the question of whether or not the above paths are correct,and what masses to assign to each as a function of metallicity,we are also interested in the evolutionary significance,if any,to the Wolf-Rayet spectral subtypes.WN-type W-R stars are classified as“early”(WNE)or“late”(WNL)depending on whether NVλλ4602,19 or NIIIλλ4634,42dominates;e.g.,WNEs correspond to numerical subtypes WN2,WN3, WN4,while WNLs consist of subtypes WN6,WN7,WN8,and WN9,with the WN5stars split between the two groups.Similarly WC-type W-R stars are classified as WCE or WCL depending upon whether CIIIλ5696dominates over CIVλ5808;e.g.,corresponding to spectral subtypes WC4through WC6and WC8-9,with some WC7s falling into each camp(Conti&Massey1989).Do these subtypes mean anything in an evolutionary sense? Various authors have claimed so(see,for example,Moffat1982),but this conjecture does not seem borne out by either observational or theoretical studies.Our understanding of massive star evolution is limited,in part,because of thedifficulty of constructing stellar models fromfirst principles.The physics of massive stars is complicated by strong stellar winds,and the choice of the functional dependence of mass-loss rates on stellar parameters(luminosity,temperature,mass,and metallicity) greatly influences the theoretical tracks(e.g.,Meynet et al.1994),particularly in the later stages of evolution.In addition,the models are sensitive to the amount of mixing.However, there is little agreement on the treatment of the relevant processes of semi-convection and overshooting(Maeder&Conti1994),while the most recent work has emphasized the significant role that rotation may play in this regard(Maeder1997,1999).Nevertheless, empirical studies of massive star evolution provide confidence that the above pictureis correct,and are beginning to provide quantitative information on the mass ranges corresponding the various paths.These studies provide an observational basis against which the models can be evaluated and refined.(For a humorous rendering of this process,the reader is referred to Fig.5in Conti1982.)1.2.An Observational Approach1.2.1.Global StudiesThe galaxies of the Local Group provide perfect laboratories for pursing these studies observationally,as the metallicity differs by almost an order of magnitude(SMC to M31) among the galaxies currently active in forming stars.During the past few years there have been a number of studies of mixed-age populations,the relative number of this and that. The implicit assumption of these studies are that the IMF slopes are identical and cover regions that provide a good sampling of stellar stages over time.The number ratios provide quantitative criterion for the models to attempt to match.These studies have found the following:(1)The relative number of RSGs to W-Rs decreases with increasing metallicity(Massey 1998a;Massey&Johnson1998).Histograms of the number of RSGs vs.luminosity reveal that there are proportionately fewer high luminosity RSGs at higher metallicity,while the lack of a sharp luminosity cut-offsupports the interpretation that as Z increases,massive stars spend a greater fraction of their He-burning phase as W-Rs,and a smaller fraction as RSGs,rather than there being a difference in the actual mass ranges that go through a RSG phase.This is why we indicated a RSG phase at high luminosities(path2above). Possibly even LBVs will go—or have gone—through a RSG phase,but this is unknown. We also do not know if massive stars go through a RSG phase at the highest metallicity: the relation between the RSG/W-R ratio and metallicity appears toflatten below the high metallicity that characterize M31,but only a few regions have been surveyed in that large galaxy,and more data are being gathered to resolve this.(2)The relative number of WCs to WNs increases with increasing metallicity,with the notable exception of the star-burst galaxy IC10(Fig.8in Massey&Johnson1998).Thistrend is also in accord with the predictions of the Conti scenario,as increased mass-loss makes it possible for a star of a given luminosity to reach the WC stage sooner,spending more of its W-R stage as a WC than a WN.(The explanation for IC10’s peculiarly high WC/WN ratio remains a mystery at present.See discussion in Massey&Johnson1998.)(3)Significant differences in the spectral subtypes found in the Magellanic Clouds compared to the Milky Way were noted by Smith(1968):no WCLs are found in the LMC or SMC,and most of the ones known in the Milky Way are found inwards of the solar circle.Similar differences are seen for the WNs.Armandroff&Massey(1991)showed that the WC line widths(which are correlated with spectral subclass)change systematically with metallicity,extending an importantfinding by Willis,Schild,&Smith(1992)to other galaxies of the Local Group.Massey(1996)proposed that the WC spectral subtypes are nothing more than an atmospheric effect due to metallicity.(See also Massey&Johnson 1998).Recently Crowther(2000)has demonstrated from W-R model atmospheres that the WN subtypes may similarly be a reflection of metallicity rather than other stellar parameters,at least in terms of WN3through WN6.1.2.2.Coeval AssociationsA more direct way exists to attack the problem of understanding massive star evolution. By using coeval associations that contain evolved,massive stars,we can in fact directly measure the mass ranges that correspond to the above evolutionary paths as a function of metallicity.This is the subject of the current series of papers.In Paper I of this series(Massey,Waterhouse,&DeGioia-Eastwood2000)we established that many Magellanic Cloud OB associations and young clusters are sufficiently coeval(∆τ<1Myr)that we can measure a meaningful cluster turn-offmass;e.g.,themass of the most massive star on the main-sequence.These turn-offmasses then place a lower-limit on the mass of the progenitors of the evolved stars in the cluster,to the extent that star-formation proceeded coevally.If the cluster is well populated,than the initial mass of the turn-offstar is a good approximation to the initial mass of the progenitor of the W-R star.In addition,the bolometric luminosity of the cluster turn-offsets useful limits on the bolometric corrections for the evolved stars,allowing tests of Wolf-Rayet model atmospheres,such as Hillier’s“standard model”(Hillier1987,1990).The results were quite revealing.In a study of19OB associations in the Magellanic Clouds,we found that at the low metallicities that characterize the SMC,only the highest-mass stars(>70M⊙)become Wolf-Rayet stars,although the sample is small.This is equivalent to saying that path(3)above occurs only for M>70M⊙for Z≤0.005.6 At the higher metallicity of the LMC(Z=0.008),WN W-R stars come from stars with masses as low as30M⊙.We also found that WC stars are found in the same clusters as WNEs;e.g.,the lowest turn-offmass found for a cluster containing WC stars was45M⊙, suggesting that stars with masses from30–45M⊙might correspond to path(3),while stars with masses45-85M⊙correspond to path(2).The rare“Ofpe/WN9”stars7,once thought to be a transition type between“Of”stars and Wolf-Rayet stars,are only found in clusters and associations with the lowest turn-offmasses,25-35M⊙.Recently the Ofpe/WN9stars were implicated in the LBV phase of massive stars,after one Ofpe/WN9star(R127)underwent an“LBV-like”outburst.But, the classical LBVs in our LMC sample,including the archetype itself S Doradus,are found in clusters with the very highest turn-offmasses,>85M⊙.(Similarly the SMC W-R star HD5980,which many consider to be a“true”LBV[Barb´a et al.1995]is found in a cluster with a very high turn-offmass.)We conclude that the Ofpe/WN9stars are just the lowest-mass versions of Wolf-Rayet stars.True LBVs,on the other hand,are found only in the clusters with the highest mass turn-offs,suggesting that they are indeed stars near their Eddington limit and are a normal stage of the most massive stars.Our study also shed light on the origin of the different W-R classes and subtypes,at least at the modest metallicity that characterizes the LMC.The early-type WN stars (WNEs)in the LMC are found in clusters with a large range of turn-offmasses(from30M⊙to100M⊙or more),suggesting that these are a stage that most massive stars go through at LMC-like metallicities.We turn now to the higher metallicity of our own Milky Way,and pose the question of where do LBVs and Wolf-Rayets of various types come from at a metallicity considerably higher than that of the Magellanic Clouds.2.The SamplePrevious attempts to use Galactic OB associations and clusters to measure the progenitor masses of W-R stars have been made by Schild&Maeder(1984),Humphreys, Nichols&Massey(1985),and Vazquez&Feinstein(1990);Smith,Meynet,&Mermilliod (1994)also discuss the issue but primarily with an emphasis on using the data for bolometric corrections.These studies relied upon results from the literature and did not obtain new spectroscopy of the cluster stars.Our experience,even in nearby young clusters,is that many of the high mass stars have been overlooked.8In this paper we draw upon the literature,but also obtain new spectroscopy for the regions where this is required.We note that few of these regions have modern photometry. This is largely irrelevant for our purposes,as discussed further in Section2.2.2below,but does affect any attempts to use the distances as probes of Galactic structure.2.1.SelectionFor our sample,we began with the lists of W-Rs believed to be likely members of clusters and associations given by Lundstrom&Stenholm(1984)and Schild&Maeder (1984).We eliminated the many regions that lacked UBV photometry(unfortunately this excludes manyfine southern regions),were too big(NGC2439,Vul OB2),or were too sparse(the“HD155603Group”).This left us with12associations for which we either obtained new spectroscopy,or adequate data existed in the recent literature.We list these regions in Table1.Two regions not listed in the table require special comment.First,we have excluded the region NGC3603from our study.NGC3603is the Milky Way’s answer to R136,in that this is a young(1-2Myr),rich region that is so highly populated that the IMF extends up to very high masses.In both cases HST was needed for spatially resolving a single“WN+abs”star into multiple objects,and for obtaining spectra of the individual components.NGC3603contains several stars with WN6-like features,but whose individual luminosities are much higher than that of normal W-Rs of their type,and whose spectra show unmistakable evidence of hydrogen,also not in accord with their type.(This can be inferred from Fig.2in Drissen et al.1995,although the significance at the the time was not apparent.)Massey&Hunter(1998)found the same thing in R136,and realized that these WN stars were simply“super Of”stars—core-H burning objects whose very large luminosities(corresponding to masses well above the120M⊙limits of published evolutionary tracks)result in such strong stellar winds that their spectral appearance mimics that of Wolf-Rayet stars.(The same conclusion is reached by de Koter,Heap,&Hubeny1997.)An excellent comparison between the NGC3603and R136objects is provided by Crowther&Dessart(1998).We ignore these objects here,primarily as we do not consider them true Wolf-Rayet stars.We also call attention to the cluster NGC6231(the nucleus of the large Sco OB1 association),which contains two Wolf-Rayet stars,the WN7star HD151932,and the WC7+O5-8binary HD155720.Although the cluster has received recent photometric attention(Perry,Hill,&Christodoulou1991;Sung,Bessell,&Lee1998;Baume,Vazquez &Feinstein1999),there is no modern spectroscopic study of this highly interesting region. Such a study would bolster or refute claims of large age spreads and peculiar mass functions in this cluster,as well as potentially providing additional information on the progenitor masses of Wolf-Rayet stars.2.2.New Data:Spectral Types and Improved Distances and Reddenings2.2.1.Spectral Types:New Data and ClassificationOwing to the recent study of a number of northern hemisphere OB young clusters and OB associations(Massey et al.1995a and references therein),most of our new spectroscopy was obtained for stars in interesting southern OB associations.The majority of the new spectra were obtained on the CTIO1.5-m telescope with the Loral1K CCD(1200×800 pixels)spectrometer on1998Mar19(UT)with grating47in second order and a CuSO4 blockingfilter.The dispersion was0.56˚A pixel−1,and the100µm slit(1.8arcsec)yielded a resolution of1.5˚A(2.5pixels)with coverage from4035˚A to4700˚A.Data were also obtained from Kitt Peak telescopes of the northern clusters(Berkeley87 and Ma50),as well as critical data for some stars in the southern associations,admittedly at very low elevations.Most of these were obtained on the Mayall4-m during1998Sept 11-14.The RC Spectrograph was used with the T2KB detector(2048×2048pixels),with grating KP-22used in second order and a CuSO4blockingfilter.The dispersion was0.72˚A pixel−1,and the300µm(2.0arcsec)slit yielded a resolution of1.8˚A(2.5pixels),withcoverage from3750˚A to5000˚A being in good focus.A few data were also obtained on the Kitt Peak2.1-m telescope1998July19and21, and on2000Mar17,using the“GoldCam”spectrometer with its Loral3K x1K CCD. Grating47was used in second order with a dispersion of0.47˚A pixel−1,and the250µm(3 arcsec)slit provided a resolution of1.9˚A(4pixels).The wavelength coverage was3800˚A to4800˚A.Thus in all cases the wavelength range covered the important classification linesSi IVλ4089to He IIλ4686,at resolutions of1.5–1.9˚A.Goodflat-fielding was provided by exposures of an illuminated white spot.Wavelength calibration was by means of He-Ar(CTIO)or He-Ne-Ar(KPNO)lamps.The customary IRAF optimal-extraction routines were used.We usually achieved a S/N of80per spectral resolution element.We classified the stars based upon the criterion given in Walborn& Fitzpatrick(1990).We list in Table2the brightest stars in each of these associations,including our new spectral types plus any from the literature.We have measured accurate coordinates from the Space Telescope Science Institute’s Digitized Sky Survey images,and include these in Table2to facilitate exact identification.We describe the most interesting spectra here.Two Newly Discovered O3Stars.The“O3”class was introduced by Walborn(1971) as an extension of the MK classes to hotter effective temperatures.At modest resolution and signal-to-noise(S/N),the spectra show no He I lines,but rather strong He II.The class is clearly degenerate,as higher resolution and better S/N shows He Iλ4471with equivalent widths as large as120-250m˚A in some stars(Kudritizki1980;Simon et al.1983),and less than75m˚A in others(i.e.,Paper I).Since the O3class represents the hottest class,all members are of high mass,and stars of type O3III and O3I must be of extremely highmass.Such stars are correspondingly rare,with onlyfive possible examples in the Milky Way(e.g.,the four mentioned by Walborn1994plus one other possible example discovered by Massey&Johnson1993in Tr14/16).Thus,our discovery here of two additional such stars,both in the poorly studied cluster Pis24(Sec.2.3.6)is of some interest.We illustrate the spectra of these two stars, Pis24-1and Pis24-17in Fig.1.In the case of HDE319718=Pis24-1,we do detect He I λ4471with an equivalent width of85m˚A,comparable to that seen in the most extreme of Carina stars which originally defined the class.Pis24-1is clearly of type O3If*:the “f”as both N IIIλλ4634,42and He IIλ4686are seen in emission,and the“*”signifying N IVλ4058emission stronger than N III.Both features are luminosity indicators,thus resulting in the“I”luminosity class.Note also the strong N Vλλ4603,19absorption,which also appears to be stronger in O3stars of high luminosity,although one might expect there is also a strong temperature dependence for this line,which is not seen in O4stars,except at high luminosities.The star had been previously classified as“O4(f)”by Lorret,Testor, &Niemela(1984),although in fact Vijapurkar&Drilling(1993)had suggested an“O3III”designation.In the case of Pis24-17,we do not detect He I.We would argue that its luminosity class is intermediate between“III”and“I”:on the one hand,He IIλ4686is strongly in absorption while N III is in emission,suggesting an O3III(f*)classification,given that the N IV emission is comparable in strength to that of N III.However,there is incredibly strong N V absorption,which would argue either for higher luminosity(or higher effective temperature?).Rather than attempt to introduce a II(f*)into the nomenclature,we classify the star as O3III(f*).We are indebted to Nolan Walborn for his insightful comments on this spectrum.This star was labeled”N35B”by Lortet et al.(1984),and classified asO4-5V.Doubtless the strong nebular He Iλ4471emission disguised the O3nature of thisand Pis24-1on their photographic spectra.Other Early O-type Supergiants.We show in Fig.2a few of our other earlyO-type supergiants.The spectra here can be compared to those illustrated in Walborn& Fitzpatrick(1990).These spectra,and the new types listed in Table2,emphasize the need for modern spectroscopic studies of early-type stars even within modest distances of the Sun.2.2.2.Reddenings and DistancesIn order to locate the stars in the H-R diagram and assign masses,we need to know their luminosities;for this,we need to know their distances and reddenings.We have photometry(from the literature),and good spectral types(mostly new),for only the brightest dozen or so stars in each cluster(e.g.,Table2),with the exception of the clusters previously studied in order to determine their initial mass function.Main-sequence fitting is of little use when dealing with stars this hot,as color information(even in the absence of reddening)provides little information about effective temperature.Instead, we derive distances and reddenings through the spectral types,adopting the absolute magnitude calibration discussed in Paper I,as well as the same intrinsic color calibration.For each star with a spectral type in Table2,we computed the reddening and true distance modulus,and then eliminated any obvious outliers.Discrepant distances can be due either to misclassification by a luminosity class(relatively easy for the early B stars) or non-membership;multiplicity must also play an occasional role.The results are given in Table1,along with the other data on the clusters.We have also included an estimate of thesize of the region.In general,the determination of the distance moduli is good to0.1mag9.2.3.Discussion of Individual Clusters2.3.1.Ruprecht44(C0757−284)The Ru44cluster has been described by Moffat&FitzGerald(1974),FitzGerald&Moffat(1976),Havlen(1976),and Turner(1981);see also McCarthy&Miller(1974). The cluster is a condensation in the Pup OB2association.The WN4.5star WR10 (HD65865=MR11)is listed by Moffat&FitzGerald as a member,although it lies well outside the central part of the cluster.(The“core”as shown in Fig.1of Moffat& FitzGerald has a radius of6.4arcmin;the W-R star lies14arcmin to the SE of its center.) Distance estimates have ranged from the large values of Moffat&FitzGerald(1974)and FitzGerald&Moffat(1976)who proposed distance moduli of14.1–14.2mag(6.6–6.8kpc), to the smaller value of13.2mag(4.3kpc)found by Havlen(1976).The most recent and complete study is that of Turner(1981),whofinds a distance modulus of13.3mag(4.7kpc) from main-sequencefitting,in accord with the Hβvalue of Havlen.Many of the existing spectral types in the cluster are listed by Moffat&FitzGerald (1974)and Turner(1981)as uncertain,and we obtained new spectral information for eight stars.Wefind that the stars described as O-type are generally no earlier than B-type;for instance the star LSS909described as“O6:e”by Moffat&FitzGerald,and revised to“O8”by Turner,is actually a B1V according to our CCD spectroscopy,and is likely a foreground object.(It was included as one of the outlying possible members by Turner.)Similarly, the star LSS899(Ru44-182)was classified by Moffat&FitzGerald(1974)as“O8V”,but subsequently reclassified as B0V by Reed&FitzGerald(1983).On the other hand,the star LSS891(Ru44-183)was called“O9.5”by FitzGerald&Moffat(1976)is actually an O8III(f)according to our spectroscopy,similar to the O8V classification by Reed& FitzGerald(1983).Our derived distance modulus of13.35mag is in excellent accord with that found by Turner(1981).2.3.2.Collinder228(C1041−597)Cr228is just south of theηCarinae clusters Tr14and Tr16,and Cr232;see Figure1 in Massey&Johnson(1993).An excellent spectroscopic study of this region was conducted by Walborn(1973a,1982).In constructing our list of members,we began with the UBV photometry of Feinstein,Marraco,&Forte(1976).(The photometry of HD93146comes from Turner&Moffat1980.)Spectral types are from Walborn(1973a,1982),as well as Levato&Malaroda(1981),with a few additional types from Tapia et al.(1988)based upon unspecified sources.To this we add our own16new spectral types,mostly of stars with previous spectroscopy;the agreement between different sources is generally very good. We eliminate stars thought to be non-members based on spectra or color,as indicated by Tapia et al.We also ignore the plethora of stars with late-B or early-A dwarf spectral types in determining the distance modulus or constructing the HRD.The resulting true distance modulus is12.45mag(3.1kpc)and the average color excess E(B−V)=0.37. (Our apparent distance modulus,13.6mag,is identical with that found by Tapia et al.but the true distance modulus is somewhat greater since they derive a higher average reddening for Cr228based upon calculating E(B−V)from their measured E(V−K)values.)Our distance modulus would place the cluster at essentially the same distance as the rest of the ηCar complex;see Massey&Johnson1993).A few of the stars have luminosity classes or reddenings inconsistent with the adopted distance,but the corrections are minor and probably all of these stars with spectral types are members.The W-R member is WR24,of type WN7.2.3.3.Trumpler14/16The LBV starηCarinae is part of the Tr14/16complex,as is the W-R starHD93162=WR25(WN7+abs).Massey&Johnson(1993)provide a modern CCD study。