Translating Gaelic Scotland the culture of translation in the context of modern Scottish Ga

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:53.44 KB

- 文档页数:12

My hometown is a place of breathtaking beauty, where natures splendor unfolds in every corner. Nestled amidst rolling hills and lush greenery, it is a haven for those seeking tranquility and connection with the natural world.Growing up, I was fortunate to be surrounded by this picturesque landscape. The mornings were greeted by the soft hues of dawn as the sun peeked over the horizon, casting a warm glow on the dewkissed fields. The air was crisp and fresh, carrying the scent of damp earth and blooming wildflowers. As a child, I would often take early morning walks with my grandfather, marveling at the vibrant colors of the sunrise and listening to the melodious chirping of the birds.The heart of my hometown is a serene lake, its surface as smooth as glass, reflecting the azure sky and the surrounding mountains. On calm days, its not uncommon to see fishermen casting their lines, hoping to catch a glimpse of the shimmering scales of the fish that dwell beneath the waters surface. The lake is also a popular spot for families during the summer months, with children splashing and laughing as they play in the cool water, creating ripples that disrupt the mirrorlike reflection.Surrounding the lake are acres of fertile land, where farmers work tirelessly to cultivate a variety of crops. The sight of the golden wheat fields swaying in the breeze is a common one, as is the sight of the farmers faces, weathered by years of toil but always filled with pride and satisfaction. The fruits and vegetables grown here are renowned for their freshness and flavor, a testament to the rich soil and the dedication of the local farmers.As the seasons change, so too does the landscape of my hometown. In the autumn, the leaves on the trees transform into a palette of fiery reds, oranges, and yellows, creating a stunning contrast against the evergreen backdrop. The crisp air carries the scent of burning leaves and the sound of childrens laughter as they jump into piles of fallen leaves.Winter brings a blanket of snow, transforming the landscape into a pristine white canvas. The lake freezes over, and the hills are dusted with a layer of frost, creating a magical, fairytale like setting. The tranquility of winter is only broken by the occasional crack of ice as it forms on the lakes surface or the soft hush of snowflakes falling from the sky.One of the most striking features of my hometown is the abundance of wildlife. Deer can often be seen grazing in the fields, their graceful movements a testament to their natural elegance. Foxes and rabbits dart through the underbrush, their quick, agile bodies a blur of motion. The skies are filled with the calls of hawks and eagles as they soar high above, scanning the ground below for their next meal.Despite the passage of time and the inevitable changes that come with it, the beauty of my hometown remains undiminished. The landscapes, the wildlife, and the people who call this place home are all part of a tapestry of life that is as vibrant and colorful as the sunsets that paint the sky each evening.As Ive grown older and ventured out into the world, Ive come toappreciate the unique charm of my hometown even more. The memories of playing in the fields, exploring the forests, and watching the seasons change have become a source of comfort and inspiration. No matter where life takes me, the beauty of my hometown will always hold a special place in my heart.。

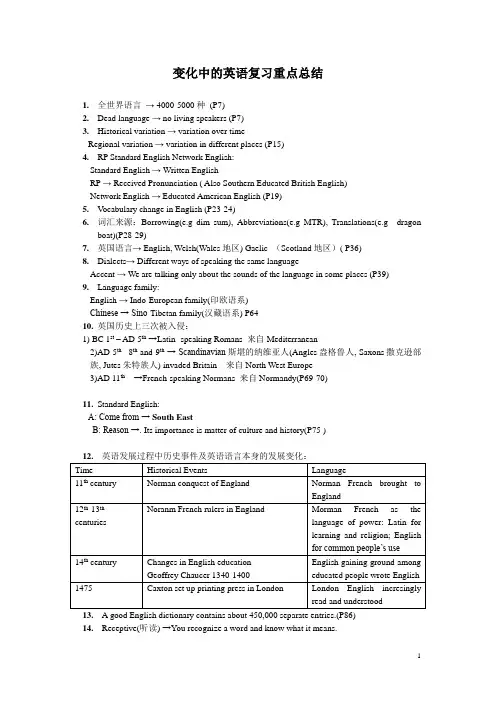

变化中的英语复习重点总结1.全世界语言→ 4000-5000种(P7)2.Dead language → no living speakers (P7)3.Historical variation → variation over timeRegional variation → variation in different places (P15)4.RP Standard English Network English:Standard English → Written EnglishRP → Received Pronunciation ( Also Southern Educated British English)Network English → Educated American English (P19)5.V ocabulary change in English (P23-24)6.词汇来源:Borrowing(e.g dim sum), Abbreviations(e.g MTR), Translations(e.g dragonboat)(P28-29)7.英国语言→English, Welsh(Wales地区) Gaelic (Scotland地区)( P36)8.Dialects→ Different ways of speaking the same languageAccent → We are talking only about the sounds of the language in some places (P39)nguage family:English →Indo-European family(印欧语系)Chinese → Sino-Tibetan family(汉藏语系) P6410.英国历史上三次被入侵:1) BC 1st– AD 5th→Latin- speaking Romans 来自Mediterranean2)AD 5th - 8th and 9th→ Scandinavian斯堪的纳维亚人(Angles盎格鲁人, Saxons撒克逊部族, Jutes朱特族人) invaded Britain 来自North West Europe3)AD 11th→French-speaking Normans 来自Normandy(P69-70)11.Standard English:A: Come from → South EastB: Reason →. Its importance is matter of culture and history(P75 )13. A good English dictionary contains about 450,000 separate entries.(P86)14.Receptive(听读) →You recognize a word and know what it means.Productive(说写)→You can say a word or you can write it.NOTE: 每个人的Receptive knowledge of vocabulary要大于Productive knowledge (P89-90)15.Prescriptive teaching(说明性教学) →correct students’ mistakesProductive teaching(输出性教学) → Practice students’ English by speaking and writing.Descriptive teaching(描述性教学) → Tell students how English has changed and come to beas it is now. P100 P10318.美国历史(The New World: the continent of America:)1584, 1585 Sir Walter Releigh’s two expeditions to the New World1620→English Puritan Playmouth Mayflower1775 → American war of Independence started1785 → End of the A set up1790 → First census人口普查held. About 90%of the population of British descent后裔P120-12119. The US A → The melting-potIn New York harbour → You ca n see the Statue of Liberty P122-12321. 印度英语发展历史:The East India Company → Started in 17 century, by 1813, it came toan end.19th century → The English man named Macaulay was called the President of theCommittee of Public Instruction,set up universities ofEnglish language P138-13922. 澳大利亚Australia 形成,Captain Cook lead the first exploration in 1770astronomical observation18th century: penal colony (罪犯流放地) (P140-141)23.Inner Circle, Outer Circle and Expanding Circle →Braj Kachru, from the sub-continent of Indiadeveloped the idea of classifying the internationaluse of English.Inner Circle: native speakers-users mother tongueBritain, North America, Australia New Zealand, South AfricaOuter Circle: taught in schools, international and official businessIndian Hong KongExpanding Circle: not an official language , international use P14724. Esperanto世界语→具有全球扩广的语言特征,且适合全球使用的理想语言What an ideal language for global use 理由P158-159Artificial language → The failed reason (p160-161)Simplify a natural language → Noah Webster made English spelling easier for the children Basic English →designed by C.K.Ogden in 1930, only 850 words P161-16225. Social Variation →speakers use English differently with their social and educational level.Languages are equal, no primitive or underdeveloped language p16626. Dead languages → Latin and Sanskrit(梵语)French, Spanish and Portuguese are descendants of Latin p17027. Pygmalion → He is a craftsmen from Greek empire, made a sculptor named Galatea. And heloves her and she came lived.My Fair Lady → Wrote by George Bernard Shaw, a famous Irish playwright. P182-183 28. False beginners → The students who have forgotten the early stages of learning a languageThe first stage of learning → Learning the rules of the sound system, the grammar, the writing system, and the vocabulary.The second stage of learning → Using English in a variety of ways. P187-18829. The rules of writing English → p202A. Always make sure your sentences are complete.B. Every sentence must hace a subject and a verb.C. Never put a preposition at the end of the sentence.D. Never use slang(俚语) or even informal words.30. T he components of a Trade Deal → p216A. a commodity(商品).B. a currencyC. a sellerD. a buyerE. a marketF. a means of communication.31. Lingua Franca(交际语/通用语) → used for trade deal p224-228Pidgin(混杂语/洋泾浜语) → It means a language,used for purpose of trade.Creoles(克利奥尔语) →是Pidgin进化后的语言p228-237Black English → P230-233Papua New Guinea → Adopted Tok PisinCreole can become a national language. ,but a pidgin can’t P23532. Present day international trade P24333. Faxed English → P249-250-25234. English in science P262 P265-26635. English in international transport P266-277Risks in air travel P271English in air traffic control →A. The language of Internetational Air Traffic Control is English.B. It is used by all ground control staff and flight crew.C. It is used in all parts of the world.D. It is twentieth century English: It is Standard English.E. It is spoken English and speakers know what they say will be recordedF. It is the English of a special area of knowledge.G. It is formal, but not polite or indirect.H. It is brief, clear, and direct. P 275Sea-speak → A special, restricted variety of English is now used internationally in ship-to-shore communication.Jargon行话→I t’s a special name for the selection that peole who have a common interest in machines and techniques use it.Slang俚语→ For the language used by young people to keep out the old.36. English and TV → P279 P28737. English and Information technology →P289English and IT → P296 P29838. ELT → English language teachingNative-speaker English language teacher 和Blingual teacher双语教师各自的优点和缺点→见P302表格Five important ELT terms: p307A.Pattern practice句型练习→Learning by constantly repeating correct Englishsentecnes.nguage laboratory语言实验室→ A classroom equipped with tape recorders and acontrol desk for the teacher.municative approach交际法| 交际教学法| 沟通式教学法| 传意形式的教学法→A view of ELT that puts first understanding and being understood by another person.D.Error analysis →Teaching in the belief that mistakes are necessary to learning and usefulto teachers.E.English for Specific Purposes →Courses designed to match the future work of andneeds of groups of leaners, very often groups with different occupations.39. ESL → English as a Second LanguageEFL → English as a Foreign LanguageL1 → English as a mother tongue见p314 表格40. New Standards → P315-31641. Hong Kong English deviates from Standard English. → P31842. Interlanguage语际语/中间语言/中介语/人工辅助语言→The languages of learners whohave only partial control of a language.Intro-national and International use →The difference between the use of English inside a country and between that country and the rest of the world. P32143. The advantages and disadvantages of Local standard and StandardEnglish:Advantages →A.They are easier and quicker to learn(so more learners will succeed)B.There are useful where there are many languages in use in a country and no commonlanguage.C.Only a minority of people need a language for international use.Disadvantages→A.Local standards change quickly and are not well regarded internationally.B.If they are use intenationally, they don’t do justice to the user or his ideas.C.Local Standards are emerging and changing, so there may not be enough suitableteachers, or teaching materials. P322-32345. Mono-lingual and Multi-lingual Societies → P34646. Opportunity cost →All learning is associated with an opportunity cost. Language learningrepresents a big investment of time and effort by individuals and by thesociety of which they are part.47. Shrinking world → P361-36248. Around the World in Eighty Days → Jules V erne (P362)49. Tower of Babel巴别塔| 通天塔| 巴比塔| 巴贝尔塔→ P365-36650. Cultural Imperialism文化帝国主义→ P38251. Proficient in English →Information about English → P394Support and reinforce each other → P407。

小学下册英语第2单元测验卷(含答案)英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.The capital of Japan is __________.2.Iron reacts with oxygen to form _______.3.The teacher is _____ (kind/strict) to us.4. A shooting star is actually a _______ that burns up in the atmosphere.5.The chemical symbol for francium is ______.6.My ______ loves to explore new technologies.7.I can use it to ______ (动词) new games. Sometimes, I pretend it is a ______ (角色).8.My dad loves __________ (历史) and shares stories with us.9.The ________ is a famous painting by Leonardo da Vinci.10.The Earth’s shape is not a perfect sphere; it is an ______.11.The _____ (种子) will grow into a new plant.12.The __________ is a famous beach destination in Florida. (迈阿密)13.The penguin is a flightless ______ (鸟) that swims well.14.I enjoy ______ with my friends at the mall. (hanging out)15.The __________ (洞穴) is dark and mysterious.16.I see a ___ (cloud/sky) above.17.The rabbit is ___ (nibbling) on some grass.18.My favorite food is _______.19.I can ________ my toys.20.The country known for its pyramids is ________ (埃及).21.The children are _____ in the classroom. (quiet)22._____ (环境) plays a big role in plant health.23. A __________ is a region known for its cultural heritage.24.The _______ (小狐狸) is quick and clever.25.Chemical engineering involves applying principles of chemistry to design processes for producing _____.26.I like to _____ (捡) shells.27.The chemical symbol for chlorine is __________.28.My grandparents love to ____.29.We need to ___ (clean) our room.30.On weekends, we often visit the _________ (玩具店) to look for new _________ (玩具).31.The chemical formula for ethanol is _____.32.The __________ is a zone of contact between two different rock types.33.Hydraulic systems use fluids to transmit ______.34.What is the name of the longest river in the world?A. AmazonB. NileC. MississippiD. Yangtze答案:B35.My favorite _________ (玩具) teaches me about science.36.We are learning about ___. (plants, eats, sleeps)37.The kitten plays with a _________. (球)38.What is the name of the process plants use to make food from sunlight?A. RespirationB. PhotosynthesisC. FermentationD. Decomposition答案:B39.I see a _____ (狮子) at the zoo.40.The _____ (花期) varies among different plants.41.The __________ (历史的图景) paints a broad picture.42. A ____(community newsletter) informs residents of events and resources.43.Mars has the largest volcano in the ______.44.The city of Honiara is the capital of _______.45.biogeography) studies the distribution of species. The ____46._____ (种植) vegetables is rewarding and fun.47.What is the opposite of "hot"?A. WarmB. CoolC. ColdD. Scorching答案: C48.My friend is a _____ (摄影师) who captures moments.49. A cat's whiskers help it sense ______ (环境).50.The chemical formula for copper(I) oxide is _____.51.Mulching helps to retain ______ in the soil. (覆盖物有助于保持土壤中的水分。

小学上册英语第二单元真题试卷英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1. A snail leaves a ______ (黏糊糊的) trail behind.2.My mom loves __________ (参与学校活动).3.Which vegetable is orange and long?A. PotatoB. CarrotC. BroccoliD. TomatoB4.The signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the _____ territories.5.The ostrich lays the largest _______ (鸟蛋).6.Which season is cold?A. SummerB. AutumnC. WinterD. SpringC7.What do you call a person who studies human cultures?A. AnthropologistB. SociologistC. ArcheologistD. All of the aboveD8.The ______ is a skilled architect.9.I enjoy playing ________ (视频游戏) on my console.10.I love to eat ______ at lunchtime.11.The __________ (历史的回响) reverberates through ages.12.The flower pot is ______ (colorful) and bright.13.My friend, ______ (我的朋友), has a pet rabbit.14.The bear eats berries and fish in the ____.15.What do you call a baby goose?A. GoslingB. DucklingC. ChickD. CalfA16.What do we call the uppermost layer of the Earth?A. CrustB. MantleC. CoreD. LithosphereA17.What is the term for a young cassowary?A. ChickB. CalfC. KitD. PupA18.What do you call an animal that is active at night?A. DiurnalB. NocturnalC. CrepuscularD. SeasonalB19.The _____ (农场) is far away.20.What do we call the part of a plant that attracts pollinators?A. PetalB. LeafC. StemD. RootA21.What do we call the young of a cow?A. CalfB. KidC. LambD. Foal22. A chemical that helps to speed up a reaction is called a ______.23.What is the opposite of sweet?A. SourB. BitterC. SpicyD. Salty24.The owl’s eyes are very ______ (大) and round.25.What do you call the protective covering of a seed?A. ShellB. HuskC. PodD. CoatD26.What is 50 - 25?A. 15B. 20C. 25D. 3027.What do we call a massive star that has exhausted its nuclear fuel?A. Red GiantB. White DwarfC. Neutron StarD. Black Hole28.What is the opposite of happy?A. SadB. AngryC. ExcitedD. Tired29.The pufferfish can inflate to protect itself from _______ (捕食者).30.What is the name of the famous shipwreck that became a movie?A. TitanicB. LusitaniaC. Andrea DoriaD. Britannic31.What is 20 15?A. 3B. 4C. 5D. 6C32.What is the capital of Thailand?A. BangkokB. PhuketC. Chiang MaiD. PattayaA33.The ________ loves to swim in the pond.34.I wear ______ (glasses) to see better.35.I have a __________ in my class. (朋友)36.I enjoy _______ (与家人一起)露营。

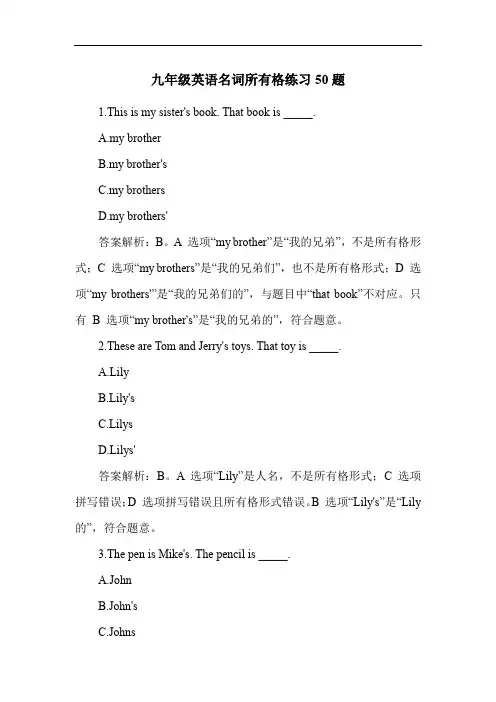

九年级英语名词所有格练习50题1.This is my sister's book. That book is _____.A.my brotherB.my brother'sC.my brothersD.my brothers'答案解析:B。

A 选项“my brother”是“我的兄弟”,不是所有格形式;C 选项“my brothers”是“我的兄弟们”,也不是所有格形式;D 选项“my brothers'”是“我的兄弟们的”,与题目中“that book”不对应。

只有B 选项“my brother's”是“我的兄弟的”,符合题意。

2.These are Tom and Jerry's toys. That toy is _____.A.LilyB.Lily'sC.LilysD.Lilys'答案解析:B。

A 选项“Lily”是人名,不是所有格形式;C 选项拼写错误;D 选项拼写错误且所有格形式错误。

B 选项“Lily's”是“Lily 的”,符合题意。

3.The pen is Mike's. The pencil is _____.A.JohnB.John'sC.JohnsD.Johns'答案解析:B。

A 选项“John”是人名,不是所有格形式;C 选项拼写错误;D 选项拼写错误且所有格形式错误。

B 选项“John's”是“John 的”,符合题意。

4.This is my father's car. That car is _____.A.my uncleB.my uncle'sC.my unclesD.my uncles'答案解析:B。

A 选项“my uncle”是“我的叔叔”,不是所有格形式;C 选项“my uncles”是“我的叔叔们”,不是所有格形式;D 选项“my uncles'”是“我的叔叔们的”,与题目中“that car”不对应。

黄檀硐之行:自然与历史的和谐交响Nestled amidst the serene greenery of Zhejiang’s mountainous region, Huangtang Cave stands as a testament to the intersection of nature and history. My journey to this enigmatic locale was a tapestry of breathtaking scenery, profound historical insights, and a profound appreciation for the harmony between man and nature.Upon arrival, the first thing that struck me was the serene atmosphere. The air was fresh and crisp, filled with the scent of pines and earth. The mountains loomed in the distance, their contours softened by the morning mist. As I walked towards the cave, I could hear the gentle trickle of a nearby stream, its melody adding to the serene ambiance. The entrance to Huangtang Cave was humble, but its interior was a different world altogether. The interior of the cave was vast, with stalactites and stalagmites of various shapes and sizes. The natural formations were breathtaking, each one a masterpiece of nature’s artistry. The soft glow of the lights illuminated the cave, casting mysterious shadows on the rocky walls.As I explored further, I discovered that Huangtang Cave was not just a natural wonder; it also bore the traces of human history. Carvings and inscriptions from ancient times were etched into the rock walls, telling tales of a bygone era. It was fascinating to imagine the lives of the people who once inhabited this place, and how they interacted with this natural marvel.Outside the cave, the village of Huangtang offered a glimpse into the traditional way of life. The houses, made of stone and wood, blended seamlessly with the surrounding landscape. The villagers were friendly and welcoming, eager to share their stories and culture with visitors.My journey to Huangtang Cave was not just a physical one; it was also a journey of discovery and understanding. It taught me about the interconnectedness of nature and history, and how humans have always been a part of the natural world, shaping it and being shaped by it in turn. The experience left me with a renewed sense of awe and respect for the natural world, and a deeper appreciationfor the cultural heritage that is intertwined with it. Huangtang Cave is not just a place; it is a symbol of theharmony that can exist between man and nature, a harmony that we should strive to preserve and cherish.**黄檀硐之行:自然与历史的和谐交响**隐匿于浙江群山环抱的静谧绿意之中,黄檀硐以其自然与历史的交汇之美,成为了历史的见证。

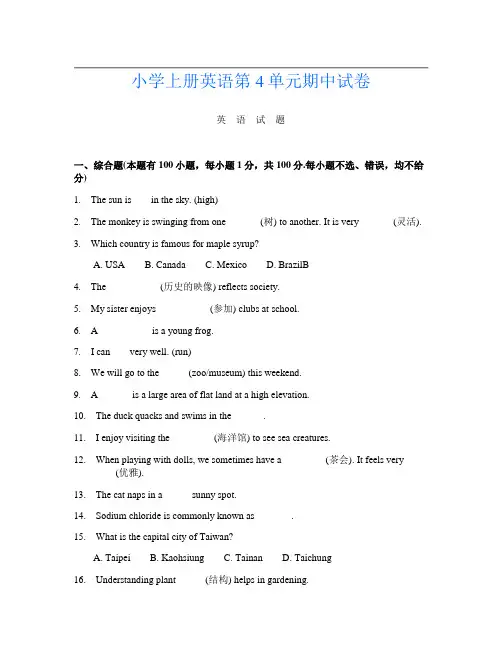

小学上册英语第4单元期中试卷英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.The sun is ___ in the sky. (high)2.The monkey is swinging from one ______ (树) to another. It is very ______ (灵活).3.Which country is famous for maple syrup?A. USAB. CanadaC. MexicoD. BrazilB4.The __________ (历史的映像) reflects society.5.My sister enjoys __________ (参加) clubs at school.6. A __________ is a young frog.7.I can ___ very well. (run)8.We will go to the _____ (zoo/museum) this weekend.9. A ______ is a large area of flat land at a high elevation.10.The duck quacks and swims in the ______.11.I enjoy visiting the ________ (海洋馆) to see sea creatures.12.When playing with dolls, we sometimes have a ________ (茶会). It feels very________ (优雅).13.The cat naps in a _____ sunny spot.14.Sodium chloride is commonly known as _______.15.What is the capital city of Taiwan?A. TaipeiB. KaohsiungC. TainanD. Taichung16.Understanding plant _____ (结构) helps in gardening.17.My dad is a ________.18.The _______ of a fern are usually delicate.19.What is 8 + 6?A. 14B. 15C. 16D. 1720.What is the name of the famous music festival held in the USA?A. CoachellaB. GlastonburyC. LollapaloozaD. BonnarooA21.Carbon dioxide is a gas produced by _____ respiration.22. A frog has smooth ______ (皮肤).23.What is the first month of the year?A. JanuaryB. FebruaryC. MarchD. April24. A molecule of carbon dioxide consists of one carbon and _______ oxygen atoms.25.Plants need ______ (水) to survive and grow.26. A chemical reaction can be described by a _____ equation.27.The capital of Japan is __________. (东京)28.The main component of starch is _____.29.The __________ is the capital city of Chile. (圣地亚哥)30.I need to ________ (buy) some groceries.31. A reaction that absorbs heat is called an _______ reaction.32.The ____ is known for its colorful feathers.33.The flowers smell ________.34.The kitten is _____ (cute/ugly).35.The _______ (Hellenistic period) followed the conquests of Alexander the Great.36.I enjoy ______ (看书) at the library.37.The discovery of ________ has drastically changed our approach to agriculture.38. A ______ is a large body of water surrounded by land.39.The ________ loves to splash in puddles.40.Mount Fuji is a famous ________ (富士山是著名的________) in Japan.41.The _______ (蝴蝶) flutters near flowers.42.My best friend is ______ (小明). We play together every day after ______ (学校).43.Space shuttles were used to transport astronauts to ______.44.The ancient Romans used ________ for building roads.45.What do we call the sound made by a duck?A. QuackB. MooC. BaaD. Roar46.I write poems for my ____.47.When I grow up, I want to travel around the _______ (世界). There’s so much to see.48.Acid and base can neutralize each ______.49.What do we call a person who speaks many languages?A. LinguistB. TeacherC. ScholarD. Professor50.My _____ (舅舅) loves to travel.51. A __________ is a type of reaction that creates new substances.52.My grandma teaches me how to ____ (knit).53.Which of these is a large body of water?A. RiverB. LakeC. OceanD. Pond54.I want to _____ (travel/stay) home this summer.55.I often ask for ________ (名词) for my birthday so I can buy new toys.56.What is the largest organ in the human body?A. HeartB. SkinC. LiverD. Brain答案:B57. A hawk has excellent ________________ (视力).58.What do you call the person who plays a musical instrument?A. ArtistB. MusicianC. PerformerD. ComposerB59.The ancient Chinese invented ________ to measure time.60. A sunflower follows the _____ (太阳).61.The chemical symbol for magnesium is ____.62.The _______ tells us the number of protons in an atom.63.Which animal is known for its black and white stripes?A. TigerB. ZebraC. LeopardD. PandaB64.I like to pick _____ (野花) in the field.65.If you drop a feather and a rock, the rock will fall _______.66.How do you say "elephant" in Spanish?A. ElefanteB. ÉléphantC. ElefantD. Elefanto67.George Washington was the first __________ of the United States. (总统)68.The __________ (历史的传承) shapes future identity.69.The train goes ______ (fast) on the tracks.70.Electrons are negatively charged _______ found in atoms.71.My _______ (狗) loves to play in the snow.72.What is the name of the famous museum in Paris that houses the Mona Lisa?A. Musée d'OrsayB. Louvre MuseumC. Pompidou CenterD. The MetB Louvre Museum73.The __________ (历史研究) is essential for understanding our place in the world.74.The rabbit has two big ______ (眼睛).75.We will go ______ tomorrow morning. (swimming)76. A fish swims in the _____.77.Gardeners often use ______ (肥料) to help plants grow.78.How many colors are in the American flag?A. 2B. 3C. 4D. 5B79.What is the largest land animal?A. RhinocerosB. GiraffeC. ElephantD. HippopotamusC80.The Earth's surface is subject to a variety of natural ______.81.What is the main ingredient in bread?A. SugarB. FlourC. RiceD. SaltB82.What is the capital of Jamaica?A. KingstonB. Montego BayC. NegrilD. Ocho RiosA83.Chemical reactions can either absorb or release ______.84.The butterfly begins as a ______ (幼虫).85.I see a _______ (buffalo) in the field.86. A cactus can survive in _____ (干旱) conditions.87.What do we call the central part of a story?A. BeginningB. MiddleC. EndingD. ClimaxB88.My favorite thing to do on holiday is ______.89.She likes to _____ books. (read/write/eat)90.The _____ (squash) plant is prolific in summer.91.The cake is ________ with candles.92.My ________ (玩具名称) is a fun way to learn about animals.93.What is the name of the famous American author known for writing about the American South?A. William FaulknerB. Harper LeeC. Tennessee WilliamsD. All of the aboveD94.Fossils are found in ______ rocks, which form from layers of sediment.95.I like to _______ (参加) workshops.96.The toy is _____ (expensive/cheap).97.The __________ is a famous city known for its art and architecture. (佛罗伦萨)98.My favorite place is the _______ (海滩).99. A ______ is a geographical feature that attracts scientists.100.I see a _____ in the park. (squirrel)。

介绍甘德尔山英语作文Gandalf Mountain, located in the heart of the picturesque countryside, stands tall and majestic, captivating all who behold its grandeur. Rising gracefully against the backdrop of azure skies, it is a beacon of natural beauty and a haven for adventure seekers and nature enthusiasts alike.Nestled within the rugged terrain, Gandalf Mountain boasts an array of breathtaking landscapes and diverse ecosystems. From lush green forests teeming with wildlife to cascading waterfalls that glisten in the sunlight, every corner of this majestic mountain exudes a sense of tranquility and wonder.One of the most enchanting features of Gandalf Mountain is its network of hiking trails that wind their way through the wilderness, offering visitors the opportunity to explore its hidden treasures. Whether you're an experienced hiker or a casual stroller, there's a trail for everyone,each offering its own unique challenges and rewards.At the summit of Gandalf Mountain, adventurers are rewarded with sweeping panoramic views that stretch as far as the eye can see. The sense of accomplishment that comes from conquering its lofty peaks is unparalleled, making ita favorite destination for mountaineers and thrill-seekers.But Gandalf Mountain is not just a playground for outdoor enthusiasts; it is also a place of cultural significance and historical importance. Throughout the ages, it has been a source of inspiration for artists, writers, and poets, who have immortalized its beauty in their works.In addition to its natural splendor, Gandalf Mountainis also home to a vibrant community of flora and fauna,each playing a vital role in the delicate ecosystem that thrives here. Rare and endangered species find sanctuary amidst its rocky slopes and verdant valleys, protected by dedicated conservation efforts.For those seeking a more leisurely experience, GandalfMountain offers a range of amenities and attractions, including cozy mountain lodges, quaint villages, and charming cafes where visitors can relax and unwind after a day of exploration.In conclusion, Gandalf Mountain is not just a geographical landmark; it is a symbol of resilience, beauty, and adventure. Whether you come to challenge yourself onits rugged trails, immerse yourself in its natural splendor, or simply escape the hustle and bustle of everyday life,you are sure to find something magical amidst its towering peaks and hidden valleys.。

The vast expanse of the grasslands is a sight to behold,a natural canvas painted with hues of green that stretch as far as the eye can see.The grasslands are a unique ecosystem, teeming with life and characterized by their flat terrain and minimal human intervention.The grasslands are home to a variety of flora and fauna.The grasses themselves are the primary vegetation,ranging from short,dense tufts to tall,swaying stalks that dance in the wind.They provide a habitat for numerous species of insects,birds,and small mammals.The occasional tree or shrub punctuates the landscape,offering a break from the monotony and a place for animals to rest or hide.Wildlife is abundant in the grasslands.Herds of grazing animals,such as bison or antelope,roam the open spaces,their numbers swelling in the spring and summer months. Predators,like wolves or foxes,stalk their prey across the plains,their stealthy movements a testament to their adaptation to this environment.The skies above are filled with the calls of birds of prey,circling high above in search of their next meal.The climate of the grasslands is typically temperate,with warm summers and cold winters.The change in seasons brings about a transformation in the landscape.In spring, the grasses begin to grow,their fresh green color a sign of renewal.Summer sees the grasslands at their most vibrant,with the plants reaching their peak height and providing a lush backdrop for the wildlife.Autumn brings cooler temperatures and a change in the color palette,with the grasses turning golden and the leaves on any trees taking on hues of red and orange.Winter blankets the grasslands in a layer of snow,creating a stark contrast against the browns and grays of the dormant landscape.The grasslands are also a place of human history and culture.Nomadic tribes have roamed these lands for centuries,relying on the grasses for their livestock and the wildlife for sustenance.The open terrain has also been a battleground for various conflicts,with armies taking advantage of the flat landscape for strategic maneuvers.Despite their beauty and importance,grasslands are under threat from various factors, including climate change,overgrazing,and conversion to agricultural land.Conservation efforts are crucial to preserving these unique ecosystems for future generations to appreciate and enjoy.In conclusion,the grasslands are a testament to the power and beauty of nature.Their diverse wildlife,changing seasons,and rich history make them a fascinating subject for study and exploration.As we continue to learn more about these ecosystems,it is our responsibility to protect and preserve them for the benefit of all living creatures that call them home.。

小学上册英语第1单元真题试卷英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.I enjoy ___ (gardening) with my grandma.2.The __________ is essential for understanding the Earth's climate system.3.What do we call a written record of someone's life?A. BiographyB. AutobiographyC. MemoirD. Journal4.The process of crystallization separates solids from ______.5.The ________ (种子) grows into a new plant.6.What is the name of the fictional cat who is known for being lazy?A. TomB. GarfieldC. FelixD. SylvesterB7.__________ change involves a change in state, not in composition.8.The cake is _____ for the party. (ready)9.How many continents are there?A. FiveB. SixC. SevenD. Eight10.My favorite activity is to ________ (参加活动).11.What do you call a young penguin?A. ChickB. PupC. CalfD. KitA12._____ (温带) plants can survive seasonal changes.13. A __________ is a reaction that produces new substances with different properties.14.My dad _____ a car to work. (drives)15.What do we call the process of changing from a caterpillar to a butterfly?A. TransformationB. EvolutionC. GrowthD. MetamorphosisD16.What is the smallest unit of life?A. CellB. TissueC. OrganD. Organism17.What is the largest organ in the human body?A. HeartB. BrainC. SkinD. LiverC Skin18.This ________ (玩具) opens doors to creativity.19.My dad teaches me . (我爸爸教我。

小学上册英语第5单元真题(有答案)英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.The process of breaking down food in our bodies releases _____.2.What is the opposite of "fast"?A. QuickB. SlowC. SpeedyD. Rapid答案:B3. A __________ can indicate the presence of oil or gas beneath the surface.4.What is the capital of Chile?A. SantiagoB. ValparaísoC. ConcepciónD. La Serena答案: A5.What is the name of the famous ancient city in Jordan?A. PetraB. BabylonC. UrD. Nineveh答案: A6.The __________ (历史的象征) can carry deep meaning.7.I enjoy cooking with my mom. We make delicious ______ (晚餐) together.8.The ________ is a charming little insect.9.What is the capital of Azerbaijan?A. BakuB. TbilisiC. YerevanD. Bishkek答案:A.Baku10.The bee works hard to make _______ (蜂蜜).11.I saw a _______ (小狗) playing in the park.12.The _____ (daisy) is blooming.13.The _______ (Titanic) sank after hitting an iceberg in the North Atlantic.14.During winter, we have snowball fights and make ________ (雪人). It’s a fu n________ (活动).15.The __________ is a famous mountain in the Andes. (马丘比丘)16.I have a toy _______ that can zoom really fast.17.We will have a picnic in the _______ (park/school).18.I want to _______ (学习) how to swim.19.I like to ______ (参加) workshops.20. A ______ is a cold-blooded animal.21.My sister enjoys __________ (参加) workshops.22.ng Rebellion was a massive civil war in ________ (中国). The Taj23. A ____ is a friendly pet that often wags its tail.24.Some _______ can be very large and impressive.25.Listen and number.听录音排序。

The vast expanse of the grasslands is one of the most enchanting landscapes in the world.The beauty of the grasslands is not only in their size but also in the rich biodiversity they support and the unique cultural heritage they embody.Geographical WondersGrasslands are typically found in regions with moderate rainfall,which is not too abundant to support dense forests,yet sufficient to maintain a carpet of lush grasses.The most famous grasslands include the Serengeti in Africa,the Pampas in South America, the Eurasian Steppe,and the Great Plains of North America.Each of these regions has its own unique characteristics that contribute to their beauty.Flora and FaunaThe grasslands are home to a variety of plant species,including different types of grasses that sway in the wind,creating a mesmerizing effect.Wildflowers add splashes of color to the green canvas,blooming in different seasons.The fauna of the grasslands is equally diverse,with large herbivores like bison,antelope,and zebras grazing peacefully,and predators such as lions,wolves,and cheetahs maintaining the balance of the ecosystem. Cultural SignificanceGrasslands have been the cradle of many civilizations.Nomadic tribes have roamed these lands for centuries,developing a deep connection with the land and its wildlife.The traditional ways of life,including horse riding,herding,and the construction of unique dwellings like yurts and tipis,are part of the cultural tapestry of the grasslands. Natural PhenomenaOne of the most spectacular sights on the grasslands is the migration of animals.In the Serengeti,for example,the annual wildebeest migration is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of life on the grasslands.This event,driven by the search for fresh grazing lands,is a breathtaking display of natures rhythm.Conservation EffortsDespite their beauty,grasslands are under threat from various factors such as climate change,overgrazing,and conversion to agricultural land.Conservation efforts are crucial to preserve these ecosystems.Establishing protected areas,promoting sustainable grazing practices,and educating the public about the importance of grasslands are some of theways to ensure their survival.Economic ValueGrasslands also have significant economic value.They are vital for livestock farming, providing grazing lands for cattle,sheep,and other animals.The produce from these farms,such as meat and dairy products,contributes to the local and global economy. ConclusionIn conclusion,the beauty of the grasslands lies in their ecological richness,cultural depth, and the aweinspiring spectacles they offer.They are a reminder of the interconnectedness of life and the importance of preserving our natural heritage for future generations. Whether its the rolling hills of the Great Plains,the endless horizons of the Pampas,or the vibrant wildlife of the Serengeti,the grasslands are truly one of the worlds most beautiful landscapes.。

蕨类植物英文诗Ferns: A Poetic ExplorationAmidst the verdant tapestry of the earth, a hidden wonder lies, a testament to the enduring resilience of nature. Ferns, those ancient and enigmatic plants, have captivated the hearts and minds of poets and naturalists alike, weaving a tapestry of beauty and intrigue that spans the ages. In this poetic exploration, we shall delve into the captivating world of these botanical marvels, uncovering their timeless allure and the profound insights they offer.Unfurling from the shadows, ferns stand as silent sentinels, their delicate fronds a symphony of emerald hues, each leaf a masterpiece in its own right. These primeval plants, whose lineage can be traced back to the Devonian period, have weathered the ebb and flow of time, adapting and thriving in the face of countless challenges. Their very existence is a testament to the power of resilience, a reminder that even in the most unforgiving of environments, life finds a way to flourish.As we gaze upon the intricate patterns of their fronds, we are drawn into a world of enchantment, where the boundaries between thetangible and the ethereal blur. The fern, with its graceful arches and delicate lace-like structures, invites us to pause and surrender to the rhythms of nature, to find solace in the timeless dance of growth and renewal.In the quiet moments, when the world seems to hold its breath, the fern whispers its secrets, sharing the wisdom of the ages. Its very presence evokes a sense of reverence, a reminder that we are but guests in a realm that predates our own existence. The fern, a living link to the distant past, beckons us to reflect on our place in the grand tapestry of life, to appreciate the fragility and resilience that coexist in the natural world.Through the lens of poetry, we can capture the essence of these botanical marvels, translating their silent language into a symphony of words that resonate within the human soul. The fern, with its delicate fronds and its ability to thrive in the most challenging of environments, becomes a metaphor for the human experience, a symbol of strength, adaptability, and the power of renewal.In the verdant cathedrals of the forest, where sunlight filters through the canopy, the fern stands as a living testament to the enduring beauty of the natural world. Its fronds, like the outstretched arms of a silent guardian, offer a gentle embrace, inviting us to connect with the rhythms of the earth, to find solace in the timeless cycles ofgrowth and decay.As we immerse ourselves in the poetic exploration of the fern, we are reminded that true beauty is not found in the grand and the ostentatious, but in the delicate and the understated. The fern, with its humble yet captivating presence, reminds us to slow down, to observe, and to appreciate the wonders that surround us, even in the most unassuming of forms.In the end, the fern, with its ancient lineage and its enduring resilience, becomes a metaphor for the human experience, a reminder that even in the face of adversity, we too can find the strength to thrive, to adapt, and to grow. Through the power of poetry, we can celebrate the fern's timeless beauty, and in doing so, find inspiration to cultivate our own inner resilience, to embrace the cycles of life, and to find solace in the timeless rhythms of the natural world.。

Chocolate,a delicacy cherished by many,is a versatile ingredient that can be found in a variety of forms,from sweet treats to rich beverages.Here are some aspects of chocolate that one might explore in an English essay:1.Historical Origins:Delve into the history of chocolate,tracing its roots to the ancient Mesoamerican civilizations who first cultivated cacao trees.Discuss how it was consumed as a bitter beverage by the Mayans and Aztecs and how it evolved into the sweet treat we know today.2.Cultural Significance:Explore the cultural significance of chocolate in different societies.For instance,how it became a symbol of luxury in Europe after its introduction by the Spanish and how it is associated with celebrations and gifts in modern times.3.Types of Chocolate:Describe the different types of chocolate,such as dark,milk,and white chocolate,and their varying compositions.Discuss the impact of the percentage of cocoa solids on the flavor and health benefits.4.Production Process:Elaborate on the process of chocolate production,from the harvesting of cacao pods to the fermentation,drying,roasting,and grinding of the beans, and finally the conching and tempering processes that give chocolate its smooth texture.5.Health Benefits:Discuss the potential health benefits of chocolate,particularly dark chocolate with high cocoa content,which is rich in antioxidants and has been linked to heart health and cognitive function.6.Chocolate in Cuisine:Highlight the use of chocolate in various culinary creations, from desserts like chocolate cake and brownies to savory dishes and even in molecular gastronomy.7.Ethical Considerations:Address the ethical issues surrounding chocolate production, such as fair trade and child labor,and how consumers can make informed choices to support ethical practices.8.Chocolate Art and Craftsmanship:Appreciate the artistry involved in chocolate making, from handcrafted truffles to intricate chocolate sculptures,and the skill of chocolatiers who create edible works of art.9.Global Impact:Examine the global impact of the chocolate industry,including its economic influence,environmental considerations,and the role of multinational corporations versus artisanal chocolate makers.10.Personal Experiences:Share personal experiences with chocolate,such as favorite childhood memories associated with chocolate treats,or a memorable visit to a chocolate factory or shop.When writing an essay on chocolate,its important to choose a specific angle or a combination of angles that interest you e descriptive language to engage the readers senses and provide a rich,nuanced exploration of the topic.。

苏格兰单词单词:haggis1. 定义与释义1.1词性:名词1.2释义:一种传统的苏格兰菜肴,通常由羊杂(心、肝、肺等)、燕麦、洋葱等混合制成,煮在羊胃袋里。

1.3英文释义:A traditional Scottish dish made from minced sheep's offal (heart, liver, lungs, etc.), oatmeal, onions, etc., cooked ina sheep's stomach.1.4相关词汇:neeps(芜菁)、tatties(土豆),派生词:haggis - maker(制作哈吉斯的人)。

---2. 起源与背景2.1词源:源于苏格兰盖尔语。

2.2趣闻:哈吉斯是苏格兰的传统美食,在彭斯之夜(Burns Night)上是必不可少的菜肴。

这一夜晚是为了纪念苏格兰诗人罗伯特·彭斯(Robert Burns),人们会一边诵读彭斯的诗歌,一边享用哈吉斯,在享用前还会有专门的仪式,例如吹奏风笛等。

---3. 常用搭配与短语3.1短语:(1) haggis supper:哈吉斯晚餐例句:We had a delicious haggis supper last night.翻译:我们昨晚吃了一顿美味的哈吉斯晚餐。

(2) haggis neeps and tatties:哈吉斯配芜菁和土豆例句:Haggis neeps and tatties is a classic Scottish mealbination.翻译:哈吉斯配芜菁和土豆是经典的苏格兰餐食组合。

---4. 实用片段(1). "I'm going to Scotland next week. I really want to try the haggis there." My friend said excitedly. "Well, you should. It's a very unique taste." I replied.翻译:“我下周要去苏格兰。

小学上册英语第六单元期末试卷英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.My favorite toy is a ________ (玩具名). It makes me feel very ________ (形容词) when I play with it. Every time I take it out, I can’t help but ________ (动词) with joy.2.Chemical reactions can be initiated by a ______.3.I love my teddy _______ with a red bow tie.4.The ______ (小鱼) swims around the tank.5.What is the color of the sky on a clear day?A. GreenB. BlueC. YellowD. RedB6.They are _____ (climbing) the tree.7.I saw a _____ (小羊) grazing in the field.8.I call my friend’s dog __________. (狗狗的名字)9.The __________ is a large area of land that is not covered by water.10.What is the name of the famous American holiday celebrated on July 4th?A. Independence DayB. ThanksgivingC. Memorial DayD. Labor DayA Independence Day11.What is the capital of Estonia?A. TallinnB. TartuC. NarvaD. PärnuA12.I have a _____ (球) that bounces high. I love to play with it outside. 我有一个弹得很高的球。

Translating Gaelic Scotland: the culture of translation in the context of modernScottish Gaelic literatureCorinna Krause (University of Edinburgh)With this paper I would like to take a closer look at the ‘culture of translation’ as it appears to flourish in the context of modern Scottish Gaelic literature. As the Gaelic literary scene does not exist in a local literary vacuum, it is continuously involved in the process of negotiating its literary and cultural identity within the realms of a global reality. The quest for the wider audience is very present amongst those involved with Gaelic literature and has indeed been viewed in positive progressive lights as the following remark by Gaelic poet and scholar Donald MacAulay reveals:The publication of translations along with the verse has allowed access to it for non-Gaelic speakers and there is no doubt that, as a result, the status of Gaelic poets and poetry has risen in the eyes of non-Gaels. Gaelic literature has becomea more acceptable commodity for mainstream publishers and culturalentrepreneurs, and indeed for all who see themselves as connoisseurs of literary forms. And this has enhanced the status of Gaelic culture, which is a highly desirable development. (MacAulay 1994: 53)Award winning Gaelic poet Aonghas MacNeacail goes even further arguing that ‘the mere act of writing in Gaelic, no matter how instinctive or involuntarily, is a political act, a gesture of defiance against a history that has conspired relentlessly against the language. And why shouldn’t we argue that translation is also, and overtly, a political act, in that it offers a reminder to the outside world that “We are still here”?’ (MacNeacail 1998: 155).Turning the phrase ‘translation of culture’ around, arriving at the very revealing phrase ‘the culture of translation’, is very enabling in that it provides the opportunity to redress the balance of the argument by shifting the perspective from ‘out of’ Gaelic towards ‘inside’ Gaelic as literature and language. In terms of translation studies theory, we are taking the ‘cultural turn’ by moving the focus of examination from translation as text towards ‘translation as culture and politics’ (Munday, p. 127). Consequently, as Anthony Pym puts it, ‘we would like to know more about who is doing the mediating, for whom, within what networks, and with what social effects’ (p. 3). These, then, are the very questions which allow for theperspective I will adopt with this paper to view the translation dynamics that inform the existence of Gaelic literature as it is lived today.With Gaelic, it is the prevailing practice of self-translation into English published along the Gaelic texts in en-face bilingual editions which dominates and shapes literature publications most significantly, particularly Gaelic poetry publications. Research into self-translation has in the past concentrated very much on the author as a bilingual person and his or her attitude towards the texts. It is, therefore, a rather inspirational experience to read an article by Maria Fillippakopoulou in this summer’s issue of In Other Words, an issue dedicated to the subject of self-translation, in which she argues towards an historicizing approach towards the study of self-translation focusing on questions addressing what she calls:pressures relating to constraints of systematic nature, related, for instance, to languages of limited diffusion and their role vis-à-vis majority languages; [to] power differentials, shorthand for the real differences in prestige and impact between major and minor languages and literatures. (Fillipakopoulou 2005: 24) Yet, before looking closer at the specific phenomenon of self-translation in combination with the bilingual edition I consider it fruitful to take a little time to consider translation as a general phenomenon. Here I would like to draw attention to the skopos theory of translation, as established by Hans J. Vermeer, which aims to be a general theory of translation. It defines translation as purpose driven action with the translator as responsible performer of translational action who is conscious of what skopos (i.e. purpose) underlies each translation activity, since different translation choices will have different impacts on the reception of the translated text (Vermeer 1996). Let me therefore consult the active ‘agents’ of literary translation in a Gaelic context.Questionnaire-based research has shown that it is indeed the concern to widen the audience for Gaelic texts, that primarily leads authors, editors and publishers of Gaelic poetry to provide English translations.1 Interestingly, translations are also deemed helpful both for learners of Gaelic and for Gaelic native speakers who might not necessarily be confident in reading their own language. Concerning self-1 This questionnaire based research is part of my research towards a forthcoming PhD thesis on the influence of translation on Gaelic literature (Krause forthcoming).translation, some authors expressed a strong sense of ownership over their work along with a desire to keep the emphasis on the original Gaelic texts. Others are concerned to save the translation from misinterpretation, and therefore mistranslation. For many it is a pragmatic choice considering the lack of knowledge of Gaelic amongst the Scottish literary community and the lack of financial support specifically for translation. Finally, some authors view self-translation as a reflection of their bilingual existence both in creative ways (seeing the same idea expressed in the other language) and in external social ways (to allow the work to be shared by those who do not have a command of Gaelic, named in some cases as friends and family).That such a bilingual existence is not necessarily a balanced one becomes apparent in a reply by a highly acclaimed author who translates his Gaelic poetry into English almost as a matter of fact. In his reply to the questionnaire he states that ‘I would, however, not translate my own poems in English into Gaelic’ whilst pointing towards the ‘fact that I had already been writing in English before ever writing a poem in Gaelic.’ Only a small number of poets, mainly of a younger generation and not yet widely published, voiced concerns regarding translation and self-translation specifically. One poet stated that ‘the difficulty of translating not just the meaning of the words but the range of referents inherent within the culture is for me insurmountable.’ For another ‘translation into English would have meant becoming a poet in another language.’ There was also the somewhat laconic yet rather thought-provoking reply that ‘there is a large canon of English material, so why add to it.’ Finally, a poet of considerable reputation for whom Gaelic is a second language, has decided to abandon self-translation, resorting to monolingual publication or collaborative work where translations are required, as the practice of self-translation undermines the credibility of the original writing process (Whyte 2000: 183). Recent Gaelic poetry has indeed been described as ‘English poetry in Gaelic’ (MacInnes 1998: 342), yet, on the whole, translation in a Scottish Gaelic literary context curiously remains an activity performed without much reflection on its impact on Gaelic as living language and literature.What then are the conditions surrounding Gaelic literature? We have a community twice removed from state power with a minority language at its core which (finally having secured official status this year) has frequently been doomed adying language, thus demanding measures that go far beyond mere language maintenance towards pro-active language development. In a letter to Douglas Young dated 27 May 1943, just before the publication of his acclaimed poetry collection Dàin do Eimhir (1943), Sorley MacLean contemplates creative yet sensitive approaches towards the development of Gaelic vocabulary to ensure the language’s relevance to all areas of modern life (MacLean, Acc. 6419: 27 May 1943). By June of the same year, his mood had dramatically deteriorated:The whole prospect of Gaelic appals me, the more I think of the difficulties and the likelihood of its extinction in a generation or two. A … language with … no modern prose of any account, no philosophical or technical vocabulary to speak of, no correct usage except among old people and a few university students, colloquially full of gross English idiom lately taken over, exact shades of meanings of most words not to be found in any of its dictionaries and dialectally varying enormously (what chance of the appreciation of the overtones of poetry, except amongst a handful?). (MacLean, Acc. 6419: 15 June 1943)Half a century later we have an even smaller Gaelic population, and what is highly important for Gaelic as literary medium, we find that most of the native Gaelic speakers are actually English readers due to the continuous lack of presence of Gaelic as natural medium for reading and writing in education and in Gaelic society on the whole. In an article discussing publication activities in twentieth century Gaelic Scotland Joan MacDonald notes that ‘although most Gaelic speakers could, if pressed, read any Gaelic text, most are not sufficiently at ease with the written word in Gaelic to enjoy the experience’ (MacDonald 1987: 77). Yet, Gaelic is not naturally an oral language with inherent qualities which resist participation in the written medium, but rather it is simply underdeveloped with regard to the written medium particularly in terms of its reception.As a result of the social history surrounding Gaelic communities,2 Gaelic as a language has been actively minoritised and marginalized, preventing it from developing its full potential according to the needs (i.e. modern vocabulary) and opportunities (i.e. the written medium) of modern life.With regard to minority languages then, Michael Cronin, author of Translating Ireland, argues that ‘translation is both predator and deliverer, enemy and friend’2 Amongst potent social forces conditioning the existence of Gaelic communities were the Highland Clearances in late 18th/early 19th century, the Education Acts from 1872 onwards which actively suppressed Gaelic as medium for education and subsequently the overwhelming influence of Anglophone education and media.(Cronin 1998: 148) He illustrates his point referring to the example of bilingual Irish/English publications of modern Irish poetry:The translators and editors of translation anthologies defended their work on the grounds that the translations would bring the work of Irish-language poets to a wider audience […]. The acceptance of translation by many prominent poets in the Irish language could be seen as an endorsement of a policy of openness, delivering poets in a minority language from the invisibility of small readerships. However, the target-language, English, was not innocent. In a situation of diglossia where the minority language is competing for the attention of the same group of speakers, Irish people, then translation cannot be divorced from issues of power and cultural recuperation. (Cronin 1995: 92) Considering that, as identified above, Scottish Gaelic is a language which struggles in its efforts towards vocabulary maintenance and development and which is only slowlydeveloping as a language that is read by its speech community, we could conclude that the English version in bilingual Gaelic/English poetry publications faces little competition.Yet, we are not merely in the presence of translation but rather we are in the firm presence of self-translation. As research conducted in a variety of cultural environments has found, self-translation is more likely to undermine the status of the original than translation done by somebody other than the author (Fitch 1985; Grutman 1997; Jung 2002). In his article ‘The Status of Self-Translation’, Brian Fitch argues that:the writer-translator is felt to have been in a better position to recapture the intentions of the author of the original than any other ordinary translator for the very good reason that those intentions were, in fact, his own. If no distinction is made between the two versions of a given work, it is because they appear to share a common authorial intentionality. (Fitch 1985: 112)He then asks the logical question ‘does this mean then that with the abandonment of the by now wholly discredited notion of intentionality as a pertinent factor in any account of the literary text […] the activity of self-translation thereby becomes indistinguishable from that of any other form of translation’ (Fitch 1985: 112)? Does it matter then whether the translation is provided by the author or by somebody else? Fitch suggests that ‘in order to begin to clarify the situation, the basic distinction between the reception and the production of the text must be made’ (Fitch 1985: 113).As for Gaelic poetry, Stakis Prize for Scottish Writer of the Year winner in 1997 Aonghas MacNeacail explains that ‘[the judges] took the translation at face value and read them as workable poetry’ (McLeod 1998: 149). Similar dynamics are highlighted by Christopher Whyte who points out that none of the contributions to the publication Sorley MacLean - Critical Essays states whether it was the original Gaelic texts or his own English translations which served as basis for critical analysis (Whyte 2002: 70; refers to Ross and Hendry 1986). Translations, given they have been produced by the author of the original Gaelic text, have apparently acquired canonical status. Thus, the fact that the English version is in most cases the outcome of self-translation by the Gaelic author (and as such, as should be noted, is rarely referred to as translation within the publication) adds to the dominant status of the English facing text.With the bilingual edition, such dominant status seems further reiterated. Considering reading patterns with regard to the bilingual en-face edition in a special edition of Visible Language dedicated to bilingualism in literature, Lance Hewson observes that with the bilingual edition “[the] translation … is taken to be the translation of a work.” (Hewson 1993: 150). Furthermore, he reminds us that ‘it should not be forgotten that such a edition contrasts directly with the source text published by itself in its original culture, and the target text published without reference to the source text’ (Hewson 1993: 155). Arguing that with the text published in its original format only, it is firmly embedded in the source culture it sprang from, inviting the reader to appreciate the text from within such a perspective (and this I consider of crucial importance in the context of Gaelic literature), Hewson contrasts that the bilingual edition ‘is, in Meschonnic’s terminology, “decentered” towards the second language-culture, seen in the light of the translation it has undergone’ (refers to Meschonnic 1973: 30). He arrives at the conclusion that:in the bilingual edition, the very presence of a target text on the facing page acts as a magnet attracting the target language reader back towards his or her own culture, thus biasing the reader and presenting him or her with a version of the text which will inevitably have adopted some of the target language norms.(Hewson 1993: 155)Considering that with both Gaelic native speakers and Gaelic learners, it will most likely be a reader more used to reading and inevitably better read in English who comes to the bilingual edition, thus being firmly embedded within the sensibilities ofan Anglophone literary world, such publication practice reveals itself as highly dangerous to the development of Gaelic as a read language and literature in that it reinforces a reading pattern that is already there.Let me seek help from postcolonial literary criticism at this point. Contemplating the coming into being of meaning Homi Bhabha argues that ‘the pact of interpretation is never simply an act of communication between the I and the You designated in the statement’ (Bhabha 1995: 208). Rather, as Bill Ahscroft explains:the written text is a social situation. That is to say, it has its existence in something more than the marks on the page, namely in the participations of social beings whom we call writers and readers, who constitute the writing as communication. (Ashcroft 1995: 298)Meaning thus occurs at the point of a voicing and a perception of the utterance at a real moment in time conditioned by historical and social forces. With regard to the social conditioning of such an utterance as such Ania Loomba emphasises that ‘the sign, or words, need a community with shared assumptions to confer them with meaning’ (Loomba 1998: 35). With the Gaelic text in Gaelic poetry publications, then, such community is easily lost, with the Gaelic native speaker and learner (who is increasingly part of the Gaelic speech community) likely to follow established reading habits, thus relying heavily, if not entirely, on the English text. In that, Gaelic poetry could be argued to be a Gaelic flavoured extension of the English language literary canon.Moreover, the continuous presentation of their ‘native’ literature along with the English back up version, particularly in its modern appearance which on the whole is moving away from traditional literary conventions quite considerably, poses a threat to the very willingness on the part of the Gaelic reader to make sense of the text in Gaelic. This in turn prepares the path for native Gaels to condemn what is presented as a Gaelic text as not Gaelic in nature at all, thus denying the development of Gaelic literature as natural in the light of cultural exchange both within the world of Gaelic literature with its close proximity to an Anglophone world and in a world wide context of urbanisation and globalisation. In the introduction to An Tuil – a bilingual anthology of 20th century Gaelic verse - editor Ronald Black states that‘items like ‘Fontana Maggiore’ [by Christopher Whyte] […] happened to read beautifully in English, but sprang entirely from non-Gaelic models and sensitivities, and appeared not to have an independent Gaelic existence, to the extent that the Gaelic versions could not easily be understood without reference to the English.’ (Black 1999: lxiv) Offering ‘Fontana Maggiore' to a Gaelic native speaker in a close reading session as part of my PhD research, the first instinct was to consult the English translation. Having covered the English translation, I asked my informant to stay with the original. Having read through the Gaelic text he described it as ‘convoluted in parts’ acknowledging, nevertheless, a ‘very clever use of words’ in a poem that, once engaged with, ‘reads well’. It could therefore be argued that the illusion of one-to-one equivalence created by facing translations provided by the author succeeds in rendering the differences between the two texts virtually invisible, thus hiding the poetic dynamics as they unfold in the Gaelic text from the sight of the majority of readers given the prevailing reading patterns.The combination of self-translation and bilingual en-face edition thus provides a highly rigid format for Gaelic as literature and language, leaving little space for flexibility for the original to live its literary life to the full and, what is more, in its own right.Such combination is therefore a potent drug that cannot help influencing the nature of modern Gaelic literature. Witness the following statement by Iain Galbraith about a forthcoming anthology of twentieth century Scottish poetry in German:Gaelic poetry from ‘Hallaig’ to ‘cùnntas’, as it were, has existed in a permanent state of tension with the English language. To remove that tension in an anthology which purports to translate Gaelic poems not only as individual texts, but as texts that exist or have originated in a Scottish context, would be to remove them to a convenient utopia – a non-place or un-reality – whose isolation from the current polyvocal site of their primary engagement would seem to add to rather than resolve their history of displacement.(Galbraith 2000: 162-3)Besides the fact that the inevitable conclusion appears to be that there is no chance for Gaelic to be positively ‘placed’, this argument highlights the homogenising effect the culture of translation as prevailing in a Gaelic literary context has on the reception of Gaelic literature. First of all, it denies the fact that in the case of Sorley MacLean, the author of ‘Hallaig’, the majority of his early work was published in the first placewithout English translations in 1943 (MacGhillEathain 1943). Yet, more importantly, an significant aspect in the development of Gaelic poetry remains unmentioned. With MacLean, we have a poet who consciously placed his creative impulse with his Gaelic original writing, resorting to what could be described as ‘faithful’ translation after the writing of the originals, with a clear understanding that the translations are not poetry in their own right. With MacNeacail, the author of ‘cùnntas’, and other more recent authors, close reading of both the Gaelic and the English texts reveals a movement of the creative impulse between the two (Krause 2005).I would like to offer the cocnlusion that the ‘culture of translation’ as present in a Gaelic literary context carries the potential of preventing the translation of culture, in that it suggests equivalence as well as hindering the development of Gaelic as literature and language from within therefore showing bilingualism’s ‘uglier face’ resulting in ‘some kind of double monolingualism’ as Rainer Grutman puts it (Grutman 1993: 224). In that, I am observing a clash between the individual acts of creativity performed by writers and the effects such individual acts have on the collective medium that is Gaelic verse. Here I would like to recall skopos theory which defines translation as action with the actor deciding upon the strategies according to the particular purpose (i.e. skopos) of translation. I would like to argue for skopos theory to be an important translation theory to be considered in this context in that it raises consciousness about translational actions whilst highlighting the fact that translational action inevitably has an impact on the literature in question, with different approaches serving different purposes. With regard to choices, on the one hand, we might ask whether translation and publication practices surrounding Gaelic poetry fit the purpose of, as has been argued, promoting the development of literacy amongst learners and native speakers, or indeed of keeping the emphasis on the original poetry. On the other hand, if not informed about the purpose of a particular translation, readers can nevertheless draw conclusions with regard to the underlying purpose of the translation by noting particular publication approaches – to allow for smooth consumption through the medium of English suitable to raise the profile of individual authors and Gaelic poetry on the whole in an English speaking world.Prevailing translation and publication practices are very much a reflection and a result of language hierarchies surrounding Scottish Gaelic, yet, at the same time,they support and strengthen such hierarchies, thus functioning as marginalizing and therefore minoritizing forces in shaping the existence of Gaelic as literature and language. I would, therefore, like to argue towards the re-evaluation of translation in a Gaelic context as a site of friction and differences between languages and cultures which is in need of translation and publication practices which resist the illusion of one-to-one equivalence, such as non-translation, collaborative translation with clear reference to the translation process or indeed multiple translation. We might also want to note that there are choices with regard to the languages involved in the translation process. As well as having a fruitful impact on the development of Gaelic literature, translations form a variety of languages into Gaelic as well as translations of Gaelic texts into languages other than English could lead to creative collaborations between authors and translator which would ensure an active engagement with the Gaelic language in terms of actual communication, which is a vital consideration for any ‘lesser used’ language.BibliographyAshcroft, B., 1995. ‘Constitutive Graphonomy’ in Ashcroft, B., G. Griffiths and H.Tiffin (eds.), 1995. The Post-colonial Studies Reader. London and New York:Routledge, pp. 298-302.Bhabha, Homi. 1995. ‘Cultural Diversity and Cultural Differences’ in Ashcroft, B., G.Griffiths and H. Tiffin (eds.), 1995. The Post-colonial Studies Reader.London and New York: Routledge. 206-209.Black, Ronald. 1999 . ‘Introduction’ in R. Black (ed.), An Tuil.Edinburgh: Polygon, pp. xxi-lxx.Cronin, Michael. 1995. ‘Altered States: Translation and Minority Languages’ in TTR: Traduction, Terminology, Rédaction, vol. 8, part 1: 85–103.Cronin, Michael. 1998. ‘The Cracked Looking Glass of Servants: Translation and Minority Languages in a Global Age’ in The Translator, vol. 4, no 2: 145–62. Fillippakopoulou, Maria. 2005 (Summer). ‘Self-Translation: Reviving the Author?’ in In Other Words. 23-27.Fitch, Brian. 1985. ‘The Status of Self-Translation’ in Texte– revue critique at littéraire no. 4: 111–25.Galbraith, Iain. 2000 ‘To Hear Ourselves as Others Hear Us: Towards an Anthology of Twentieth-Century Scottish Poetry in German’ in Translation andLiterature, vol. 9, part 2: 153-170.Grutman, Rainer. 1997. ‘Auto-translation’ in Baker, Mona (ed.).Routledge Encyclopaedia of Translation. London and New York: Routledge. 17-20.Grutman, Rainer. 1993. ‘Mono versus Stereo: Bilingualism’s Double Face’ in Visible Language, vol. 27, pt 1/2: 206-227.Hewson, Lance. 1993. “The Bilingual Edition” in Visible Language, vol 27, part 1: 138–60.Jung, Verena. 2002. English-German Self-Translation of Academic Texts and its Relevance for Translation Theory and Practice. Frankfurt am Main: PeterLang.Krause, Corinna. 2005 (Autumn). ‘Finding the Poem - Modern Gaelic Verse and the Contact Zone’ in Forum 1 ‘Origins and Originality’. Edinburgh University./issue1/Krause_Gaelic.pdf. (3 December 2005)Krause, Corinna. (Forthcoming). Translating Gaelic Scotland: the Influence of Translation on Modern Gaelic Verse. PhD thesis. University of Edinburgh. Loomba, Ania. 1998. Colonialism/Postcolonialism. London and New York: Routledge.MacAulay, Donald. 1994. ‘Canons, myths and cannon fodder’ in Scotlands 1: 35-54.MacDonald, Joan. 1997. ‘Scottish Gaelic Publishing in the Twentieth Century’ in Celtic Literature and Culture in the Twentieth Century. The InternationalCeltic Congress: 77–84.MacGhillEathain, Somhairle. 1943. Dàin do Eimhir agus Dàin Eile. Glasgow: William MacLellan.MacInnes, John. 1998. Review of Fax and Other Poems and All my Braided Colours in Aberdeen Review, vol. 58: 342-343.MacLean, Sorley. Acc. 6419. Letters to Douglas Young, held at the National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.McLeod, Wilson. 1998. ‘The Packaging of Gaelic Poetry’, Chapman, 89-90: 149-151.MacNeacail, Aonghas. 1998. ‘Being Gaelic and Otherwise’ in Chapman, no. 89-90: 152-157.Meschonnic, Henri. 1973. Pour la poétique II. Paris: Gallimard.Munday, Jeremy. 2001. Introducing Translation Studies: Theories and Applications.London and New York: Routledge.Pym, Anthony. 2004 (10 January). ‘On the Social and the Cultural in Translation Studies’. http://www.fut.es/~apym/on-line/sociocultural.pdf. (27 November 2005).Ross, Raymond J. and Joy Hendry (eds.). 1986. Sorley MacLean: Critical Essays.Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press.Vermeer, Hans J. 1996. A Skopos Theory for Translation. Heidelberg: TEXTconTEXT.Whyte, Christopher. 2000. ‘Translation as Predicament’, Translation and Literature, vol. 9, part 2: 179-187.Whyte, Christopher. 2002. ‘Against Self-Translation’, Translation and Literature, vol. 11, part 1: 64-71.。