THE ART OF ROMANTIC POETRY by William Blake

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:178.98 KB

- 文档页数:6

Chapter 9 Romanticism1. Romanticism refers to an attitude or intellectual orientation that characterizes many works of literature , painting, music, architecture, criticism, and historiography in western civilization over a period from the late 18th to the mid-19th century.浪漫主义指的是一种态度或知识取向,刻画出了许多作品的文学、绘画、音乐、建筑、批评和史学在西方文明在一段时间内从18世纪末到19世纪中叶。

2. The "Preface" to Lyrical Ballads by William Wordsworth, known as the manifesto of romanticism, addresses the subjects, aim and style of romantic poetry as well as the essential characteristics of a romantic poet.威廉·华兹华斯是一个浪漫的诗人,他写的抒情诗集的“卷首语”,被称为浪漫主义宣言,讨论了浪漫主义诗歌的主题,目的和风格以及基本特征的。

3. William Wordsworth was an early leader of Romanticism in English poetry, who ranks as one of the greatest lyric poets in the history of English literature.威廉·华兹华斯是英语诗歌中早期浪漫主义的领袖,他在英语文学的历史位列最伟大的抒情诗人之一。

浙江省2018年1月自学考试英国文学选读试题课程代码:10054PartⅠ. Blank-filling:Complete each of the following statements with a proper word or phrase according tothetextbook. (10 points in all, 1 point for each)1. Shakespeare’s plays have been traditionally divided into three categories: histories, ______ andtragedies.2. William Caxton was the first person who introduced ______ into England.3. Wyatt, in the Renaissance period, introduced the Petrarchan ______ into England, while Surreybrought in blank verse.4. The Enlightenment Movement brought about a revival of interest in the old classical works inthe field of literature. This tendency is known as ______.5. The three unities refer to those of time, place and ______.6.RegardedasThomasGray’sbestandmostrepresentativework,ElegyWritteninaCo untryChurchyardis more or less connected with the melancholy event of the death of ______.7. In 1704 Jonathan Swift published two powerful satires on corruption in religion and learning, ATale of a Tub andThe Battle of the Books, which established his name as a ______.8. InLady Chatterley’s Lover, Lawrence not only condemns the civilized world of mechanism fordistorting human relationships, but also advocates a return to ______.9.ThesocialDarwinism,underthecoverof“survivalofthefittest”,vehementlyadvoca tedcolonialism and ______.10.Dublinersis the first important work of Joyce’s lifelong preoccupation with______ life.PartⅡ. Multiple-choice questions:Select from the four choices A, B, C, D of each item the one that best answers the question orcompletes the statement. (30 points in all, 1 point for each)11. Marlowe gave new vigor to the blank verse with his “______”.1A. lyrical linesC. mighty linesB. soft linesD. religious lines12. Francis Bacon is not only the first important essayist but also the founder of modern ______ inEngland.A. poetryC. proseB. novelD. science13. Spenser’s masterpiece is ______, which is a great poemof the age.A.The Shepheardes CalenderC.The Rape of LucreceB.The Faierie QueeneD.The Canterbury Tales14.John Milton wrote ______ to expose the way of Satan and to “justify the ways of God to men”.A.Paradise LostC.LycidasB.Paradise RegainedD.Samson Agonistes15. According to the neoclassicists, all forms of literature were to be modeled after the classicalworks of the ancient Greek and ______ writers.A. ItalianC. GermanB. BritishD. Roman16. The romantic poets of the ______ peasant poet, Robert Burns and William Blake also joinedlamenting lyrics, paving the way for the flourish of Romanticism early the next century.A. BritishC. ScottishB. IrishD. Wales17.The Pilgrim’s Progressis the most successful religious ______ in the English language.A. allegoryC. fairy taleB. fableD. essay18. ______ once defined a good style as “proper words in proper places”.A. John DonneC. Daniel DefoeB. Jonathan SwiftD. John Bunyan19. Gray’s “Elegy written in a Country Churchyard” once and for all established his fame as theleader of the ______ poetry of the day.A. romanticB. historical2C. lyricalD. sentimental20. Marx once extolled ______ as “an instinctive defender of the masses of the people against theencroachmentof the bourgeoisie”.A. William GodwinC. William CobbetB. William BurkeD. William Fox21.______,definedbyColeridge,isthevitalfacultythatcreatesnewwholesoutofdispa rateelements.A. RationC. AlliterationB. ReasonD. Imagination22. According to the subjects, Wordsworth’s short poems can be classified into two groups: poemsabout nature and poems about ______.A. human lifeC. social activitiesB. urban lifeD. inner life of an individual23. Coleridge’s actual achievement as poet can be divided into two remarkably diverse groups: the______ and the conversational.A. naturalC. spiritualB. religiousD. demonic24. Shelley’s greatest achievement is his ______ poetic drama,Prometheus Unbound(1820).A. one-actC. two-actB. three-actD. four-act25.Endymion, published in 1818, was a poem based on the ______ myth of Endymion and themoon goddess.C. ItalianB. RomanD. British26.JaneAusten’sNorthangerAbbeysatirizesthosepopular______romancesofthela te18thcentury.A. sentimentalC. GothicB. lyricalD. rational27. Chronologically the Victorian period roughly conincides with the reign of Queen ______ who3ruled over England from 1836 to 1901.A. ElizabethC. MaryB. VictoriaD. Anne28. The aestheticists Oscar Wilde and Walter Pater are two notorious advocators of the theory of______.A. art for life’s sakeC. art for art’s sakeB. art for money’s sakeD. art for reader’s sake29. Brought up with strict orthodoxy, Charlotte would usually stick to the______ code.A. ChristianC. PuritanicalB. Islamic30. As far as Emily Bronte’s literary creation is concerned, she is, first of all, a______.A. novelistC. poetB. dramatistD. essayist31. Tennyson’s most ambitious work which took him over 30 years to complete is ______.A.In MemoriamC.Poems by Two BrothersB.Idylls of the KingD.Poems, Chiefly Lyrical32.ThePublicationof______finallyestablishedBrowning’spositionasoneofthegreat estEnglish poets.A.The Ring and the BookC.Men and WomenB.The Book and the RingD.Dramatic Lyrics33. Hardy’s best local-colored works are very known as“novels of character and ______.”A. personalityC. domestic lifeB. natureD. environment34. The French ______ , appearing in the late 19th century, heralded modernism.A. symbolismC. naturismB. futurismD. surrealism35.Inhisnovelofsocialsatire,H.G.Wellsmaderealisticstudiesoftheaspirationsandfru strations of the ______.A.Little ManB.Big Man4C.Social ManD.Jungle Man36. Modernist novels came to a decline in the ______ , though Joyce and Woolf continued theirexperiments.A. 1920sC. 1940sB. 1930sD. 1950s37. The most original playwright of the ______ is Samuel Beckett, who wrote about human beingsliving a meaningless life in an alien, decaying world.A.Theater of TraditionC.Theater of AngryB.Theater of ReasonD.Theater of Absurd38. Structurally and thematically, Shaw followed the great tradition of ______.A. romanticismC. symbolismB. realismD. humanism39. ______ is the first novel of the Forsyte trilogies written by John Galsworthy in 1920.A.The Man of PropertyC.To LetB.In ChanceryD.A Modern Comedy40.Ulysses ends with the famous monologue by ______, who is musing in a half-awake state overthe past experience.A. Leopold BloomC. MollyPartⅢ. Definition:Define the literary terms listed below. (20 points in all, 5 points for each)41. Humanism42. Gothic novel43. The red thirties44. SymbolismPart IV. Reading Comprehension:ReadthequotedpartscarefullyandanswerthequestionsinEnglish.(20pointsinall,5p oints for each)45. “Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st;5B. Stephen DedalusD. FinnegansNor shall death bragthou wander’st in his shade,So long as men can breathe or eyes can see,So long live this, and this gives life to thee”.Questions:A. Identify the poem and the poet.B. Briefly interpret this part.46. “Behold her, single in the field,You solitary Highland lass!Reaping and singing by herself;Stop here, or gently pass!Alone she cuts and binds the grain,And sings a melancholy strain;O listen! for the Vale profoundIs overflowing with the sound.”Questions:A. Identify the poem and the poet.B. Comment the rime scheme.47. “Do I dareDisturb the universe?In a minute there is timeFor decisions and revisions which a minute will reverse.Questions:A. Which essay is this passage taken from? Who is the author?B. Briefly interpret this passage.48.“Ilingeredbeforeherstall,thoughIknewmystaywasuselesstomakemyinterestinh erwares seem the more real. Then I turned away slowly and walked down the middle of the bazaar. Iallowed the two pennies to fall against the sixpence in my pocket. I heard a voice call from oneend of the gallery that the light was out.Gazing up into the darkness I saw myself as a creature driven and derided by vanity; and my6eyes burned with anguish and anger”.Questions:A. Which essay is this passage taken from? Who is the author?B. Why the hero saw himself “as a creature driven and derided by vanity”?PartⅤ. Topic Discussion:Give brief answers to the following questions.(20 points in all, 10 points for each)49.Tennysonisagenuineartist.Heisquiteknownforhisartisticfeatures.Discussthem ajorartistic features of his poetry.50. What is the theme of G. B. Shaw’s play Mrs.Warren’s Profession?7。

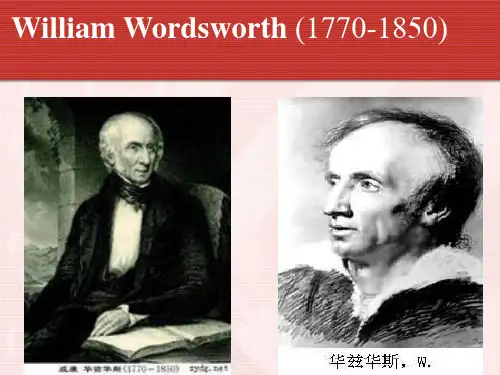

英国文学知识120题英国文学知识120题1._____is a folk legend brought to England by Anglo-Saxons from their continental homes, it isa long poem of over 3000 lines and the national epic of the English people.A.BeowulfB.Sir Gawain and the Green KnightC.The Canterbury T alesD.King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table2.The father of English poetry, the author of Troilus and Criseyde is also the one of the _____.A. Romeo and JulietB. The Faerie QueenC. TamburlaineD. The Canterbury Tales3. The group of Shakespeare plays known as “romance” or “reconciliantion plays” is _____.A. Merchant of Venice, As You Like ItB. The Tempest, Pericles, The Winter’s TaleC. Romeo and Juliet, Antony and CleopatraD. The Merry Wives of Winsor, Twelfth Night4. Which of the following are regarded as Shakespeare’s four great tragedies?A. Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Othello, King LearB. Romeo and Juliet, Hamlet, Othello, MacbethC. Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, MacbethD. Romeo and Juliet, Othello, Macbeth, Timon of Athens5. Which of the following is not the work of Francis Bacon?A. Advancement of LearningB. New InstrumentC. Songs of InnocenceD. Essays6. At the beginning of 17th century appeared a school of poets called metaphysics by Samuel Johnson, _____is the founder of metaphysical poetry.A. Ben JohnsonB. John MiltonC. John BunyanD. John Donne7. Daniel Defoe is a famous_____.A. poetB. novelistC. playwrightD. essayist8. “He has a servant called Friday.”“He” in the quoted sentence is a character in _____.A. Henry Fielding’s Tom JonesB. John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s ProgressC. Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The School for ScandalD. Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe9. Gulliver’s Travels was written by_____.A. Daniel DefoeB. Charles DickensC. Jonathan SwiftD. Joesph Addison10. William Wordsworth is generally known as a _____poet.A. romanticB. realisticC. naturalisticD. neo-classic1-10 A D B C C D B D C A11. “Ode to the west wind” was written by the author of _____.A. “I wandered lonely as a cloud”B. “Kubla Khan”C. “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage”D. “A Defence of Poetry”12. Which of the following poets does not belong to the school of romantic poets?A. William WordsworthB. Percy Bysshe ShelleyC. George Gordon ByronD. John Donne13. Charles Dickens wrote all of the following except _____.A. Oliver TwistB. David CopperfieldC. A Tale of Two CitiesD. Heart of Darkness14. “A Red, Red Rose” was written by _____.A. Alexandra PopB. Robert BurnsC. William BlakeD. John Keats15. Pip is the character of Charles Dickens’ novel _____.A. Oliver TwistB. David CopperfieldC. A Tale of Two CitiesD. Great Expectations16. Sense and Sensibility is a _____ by _____.A. play … Jane AustenB. novel… Jane Aus tenC. play … Emily BronteD. novel … Anne Bronte17. In reading Shakespeare, you must have come across the line “T o be or not to be---that is the question” by _____.A. Iago in OthelloB. Lear in King LearC. Shylock in the Merchant of VeniceD. Hamlet in Hamlet18. Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” is composed in the form of a(n) _____.A. dramatic monologueB. extended metaphorC. syllogistic argumentD. dialogue19. Thomas Hardy wrote novels of _____.A. character and environmentB. pure romanceC. “stream of consciousness”D. psychoanalysis20. “Wessex novels” refers to the novels written by _____.A. Charles DickensB. D. H. LawrenceC. James JoyceD. Thomas Hardy11-20 A D D B D B D A A D21. The sentence “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?”is the beginning line of one of Shakespeare’s _____.A. comediesB. tragediesC. sonnetsD. histories22. The three dialects spoken by _____ _____ and _____ mixed into a single language called Anglo-Saxon, or old English.A. Anglos, Saxons, JutesB. Anglos, Saxons, IrishC. Anglos, Saxons, ScottishD. Anglos, Saxons, Welsh23. _____ contribution to English lies chiefly in the fact that he introduced from France the rhymed stanza of various types, especially the rhymed couplet of 5 accents in Iambic meter--- the Heroic couplet-to English poetry.A. William Shakespeare’sB. Geoffrey Chaucer’sC. Thomas More’sD. Edmund Spenser’s24. Spenserian Stanza is a form of poetry first employed by Edmund Spenser in his long poetry _____.A. The Faerie QueeneB. The Shepher d’s CalendarC. EpihalamionD. Amoretti25. Francis Bacon is a _____.A. poetB. playwrightC. essayistD. novelist26. We can perhaps describe the west wind in Shelley’spoem “Ode to the West Wind” with all the following terms except _____.A. tamedB. swiftC. proudD. wild27. The novel starts with “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.” This novel is Jane Austen’s _____.A. EmmaB. PersuasionC. Sense and SensibilityD. Pride and Prejudice28. The major concern of _____ fiction lies in the tracing of the psychological development of his characters and in his energetic criticism of the dehumanizing effect of the capitalist industrialization on human nature.A. Charles Dicken s’sB. D. H. Lawrence’sC. Thomas Hardy’sD. John Galsworthy’s29. “Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain, and little, I am soulless and heartless? And if God had gifted me with some beauty, and much wealth, I should have made it as hard for you to leave me, as it is now for me to leave you.”The above quoted passage is most probably taken from _____.A. Pride and PrejudiceB. Jane EyreC. Wuthering HeightsD. Great Expectations30. Which of the Following is not one of the Bronte Sisters?A. Charlotte BronteB. Anne BronteC. Jenny BronteD. Emily Bronte21-30 C A B A C A D B B C31. John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress is a(n) _____.A. allegoryB. romanceC. comedy of mannersD. realistic novel32. Which of the following can not be used to describe John Dryden?A. poetB. playwrightC. essayistD. novelist33. “Conceit” was wildly used by the _____poets.A. metaphysicalB. romanticC. religiousD. realistic34. Of the many contemporaries and successors of Shakespeare, the most well known was Ben Johnson. He has been chiefly remembered for his _____. The best of which include “Every Man in His Humour”, “Volpone”, and “The Alchemist”.A. tragediesB. comediesC. historiesD. sonnets35. John Milton created Satan the real hero in his poem _____.A. Paradise Lost”B. “Paradise Regained”C. “Agonistes”D. Lycidas36. “University Wits” refers to a group of _____.A. poetsB. playwrightsC. essayistsD. novelists37. Marlowe’s best works includes three of his plays but _____.A. “Tamburlaine”B. “The Jew of Malta”C. “Doctor Faustus”D. “Julius Caesar”38. The author of “The Flea” was the representative of _____ poets.A. religiousB. romanticC. metaphysicalD. realistic39. “Studies serve for delight, for ornament, and for ability.”Is one of the epi grams found in _____.A. Bacon’s “Of Studies”B. Bunyan’s “The Pilgrim’s Progress”C. Fiedlding’s “T om Jones”D. Johnson’s “A Dictionary of the English Language”40. In the line “So long lives this, and this gives life to thee”of Sonnet 18, Shakespeare _____.A. meditates on man’s mortalityB. eulogizes the power of artistic creationC. satirizes human vanityD. presents a dream vision31-40 A D A B A B D C A B41. “Utopia” was written by _____.A. Thomas MoreB. Francis BaconC. Daniel DefoeD. Jonathan Swift42. William Blake wrote all the following except _____.A. Poetical SketchesB. Songs of InnocenceC. The Marriage of Heaven and HellD. The Tree of Liberty43. “Auld Lang Sygn” was written by the author of _____.A. A Red, Red RoseB. The Sick RoseC. A Rose for EmilyD. Tiger44. All of the following poets except _____ are called “Lake Poets”.A. William WordsworthB. Robert SoutheyC. Samuel Taylor ColeridgeD. Percy Bysshe Shelley45. Love for Love is a comedy written by _____.A. William ShakespeareB. Ben JohnsonC. William CongereD. Christopher Marlowe46. Which of the following group of writers are the playwrights of the 17th century?A. Ben Johnson and John Dryden.B. Christopher Marlowe and Daniel Defoe.C. John Milton and Oscar Wilde.D. Ben Johnson and George Bernard Shaw.47. “The poet’s poet” is _____.A. Geoffrey ChaucerB. Edmund SpenserC. Francis BaconD. John Donne48. “The founder of English poetry” is _____.A. Geoffrey ChaucerB. Edmund SpenserC. Francis BaconD. John Donne49. “The founder of English materialist philosophy ” is _____.A. Geoffrey ChaucerB. Edmund SpenserC. Francis BaconD. John Donne50. “The founder of metaphysical school” is _____.A. Geoffrey ChaucerB. Edmund SpenserC. Francis BaconD. John Donne41-50:A D A D C A B A D51. The representatives of the Enlightenment in Englishliterature were the following writers but _____.A. Joseph AddisonB. Richard SteeleC. William BlakeD. Alexander Pope52. Joseph Addison, Richard Steele and Alexander Pope belonged to the school of _____.A. classicismB. romanticismC. realismD. modernism53. _____ is a didactic poem written in heroic couplets by Alexander Pope. It sums up the art of poetry as taught by Aristotle, Horace, Boileau and the 18th century classicists. It tells the poets and critics to write and appreciate poetry according to the principles set up by the old Greek and Roman writers.A. The DunciadB. The Rap of the RockC. Essay on CriticismD. Essay on Man54. “The three Unities”, formulated by Renaissan ce dramatists, are the unities of the following elements but _____.A. timeB. placeC. actionD. character55. “The father of the English novel” is _____.A. Geoffrey ChaucerB. Edmund SpenserC. Francis BaconD. Henry Fielding56. “Tom Jones” was written by _____.A. Henry FieldingB. Daniel DefoeC. Jonathan SwiftD. Samuel Richardson57. Why is Samuel Johnson called “Dictionary Johnson”?A. Because he knows a lot more than other writers in words.B. Because he often consults an encyclopedia while writing.C. Because he is a master of English language.D. Because he is author of the first English dictionary.58. “The School for Scandal’ is a _____ written by _____.A. Tragedy…Richard Brinsley SheridanB. Comedy…Richard Brinsley SheridanC. Comedy…Sa muel JohnsonD. Tragedy…Samuel Johnson59. Oliver Goldsmith’s “The Deserted Village” is a poem of _____.A. transcendentalismB. romanticismC. sentimentalismD. realism60. Oliver Goldsmith’s “The Citizen of the World” was originally published as _____.A. English LettersB. Chinese LettersC. French LettersD. American Letters51-60: C A C D D A D B C B61. “Pamela” by Samuel Richardson is written in forms of_____.A. diaryB. letterC. autobiographyD. reminiscences62. “Clarissa Harlowe” by Samuel Richardson is written in forms of _____.A. diaryB. letterC. autobiographyD. reminiscences63. “The Adventure of Roderick Random” is written by _____.A. Samuel RichardsonB. Tobias SmollettC. Lawrence SterneD. Henry Fielding64. “The Life and opinions of Tristram Shandy” is written by _____.A. Samuel RichardsonB. Tobias SmollettC. Lawrence SterneD. Henry Fielding65. _____ named his own realistic novel as “comic epic in prose”.A. Henry FieldingB. Charles DickensC. Jack LondonD. Tobias Smollett66. “Lyrical Ballads” was written by _____ and Samuel T aylorColeridge.A. Robert BurnsB. Robert southeyC. William WordsworthD. Percy Bysshe Shelley67. George Gordon Byron was most famous for _____.A. Don JuanB. Ode to the West WindC. Kubla KhanD. Ode to a Nightingale68. George Gordon Byron created a “Byronic hero” firstly in his _____.A. Prometheus UnboundB. Childe Herold’s PilgrimageC. Kubla KhanD. Ode on a Grecian Urn69. Prometheus Unbound was written by _____ who also wrote _____.A. Geor ge Gordon Byron…Childe Herold’s PilgrimageB. Percy Bysshe Shelley… Ode to a NightingaleC. George Gordon Byron… Ode to the West WindD. Percy Bysshe Shelley…Ode to the West Wind70. John Keats is the author of _____.A. Ode to a Skylark and Ode to a NightingaleB. Ode on a Grecian Urn and Ode to the West WindC. Ode to a Nightingale and Ode on a Grecian UrnD. Ode to the West Wind and Ode to a Nightingale61-70: B B B C A C A B D C71. Percy Bysshe Shelley is famous for _____.A. Ode to a Skylark and Ode to a NightingaleB. Ode on a Grecian Urn and Ode to the West WindC. Ode to a Nightingale and Ode on a Grecian UrnD. Ode to the West Wind and Ode to a Skylark72. “Three or four families in a country village is something to work..”This statement was presen ted by _____.A. Emily BronteB. Jane AustenC. Mrs. GaskellD. George Eliot73. George Eliot wrote all the following except _____.A. The Mill of FlossB. Silas MarnerC. MiddlemarchD. Agnes Grey74. The novel Vanity Fair was written by _____.A. William Makepeace ThackerayB. Charles DickensC. O. HenryD. Henry James75. Vanity Fair was a novel written by William Makepeace Thackeray, and the term “vanity fair”firstly appeared in _____ by _____.A. Canterbury Tales…Geoffrey ChaucerB. The Pilgrim’s Progress…John BunyanC. Tome Jones…Henry FieldingD. Dubliners…James Joyce76. The novel Vanity Fair was written by William Makepeace Thackeray who also wrote _____.A. The Way of All LifeB. The History of Henry EsmondC. Sister CarrieD. Howards End77. Barchester Series is a series of novels written by _____.A. BarchesterB. Thomas HardyC. Anthony TrollopeD. Mark Twin78. Erehwon is a satiric novel written by _____.A. Samuel ButlerB. Henry FieldingC. Thomas MoreD. Mark Twin79. In “the Lake Isle of Innisfree” Willaim Butler Yeats express his _____?A. desire to escape from the materialistic societyB. fear caused by the impending warC. interest in the Irish legendD. Love for Maud Gonne, a beautiful Irish actress80. Walter Scott’s historical novels cover a long period of time, from the Middle Ages to 18th century. His work Ivanhoe deals with an epoch of _____ history.A. EnglishB. FrenchC. ScotlandD. Irish71-80: D B D A B B C A A A81. “The Graveyard Poets” got the name because _____.A. they chose to live near graveyardsB. they often wrote about death and melancholyC. they always wrote about dead people.D. they often use “graveyard” as the title.82. It is generally understood that the recurrent theme in many of Thomas Hardy’s novel is _____.A. man against natureB. love and marriageC. social criticismD. fate and destiny83. The Romantic Period in English literature began with the publication of _____.A. William Blake’s Songs of InnocenceB. Jane Austen’s Pride and PrejudiceC. Wordsworth’s and Coleridge’s Lyrical BalladsD. Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe84. It is generally regarded that Keats’ most important and mature poems are in the form of _____.A. odeB. elegyC. epicD. sonnet85. G..B. Shaw’s play Mrs. Warren’s Profession i s a realistic exposure of the _____ in the English society.A. slum landlordismB. inequality between men and womenC. political corruptionD. economic exploitation of women86. The Preface to Shakespeare and Lives of the Poets are the works of critic ______.A. G.B. Shaw B. Samuel JohnsonC. Ben JohnsonD.E.M. Foster87. The Ring and the Book is a masterpiece of _____.A. Alfred TennysonB. Robert BrowningC. Thomas HardyD. Ralph Waldo Emerson88. Matthew Arnold is the writer of _____.A. Dover BeachB. My last DuchessC. Break, Break, BreakD. The Eagle89. The writer of Heart of Darkness is also the one of _____.A. Time of MachineB. JimC. Lord JimD. A Passage to India90. Of Human Bondage is a novel by _____.A. Herbert George WellsB. Arnold BennettC. William Somerset MaughamD. John Galsworthy81-90: B D C A D B B A C C91. The Time Machine is a piece of _____.A. science fictionB. detective storyC. picaresque novelsD. historical story92. All of the following but _____ are the plays written by George Bernard Shaw.A. Mr. Warren’s ProfessionB. Saint JoanC. PygmalionD. A Doll’s House93. “The Drama of Ideas” or “The Discussion Play” refers to the plays written by _____.A. George Bernard ShawB. Oscar WildeC. Richard Brinsley SheridanD. Arthur Miller94. The only tragedy of George Bernard Shaw _____ won him the Nobel Prize.A. Mr. Warren’s ProfessionB. Heartbreak HouseC. Saint JoanD. The Doctor’s Dilemma95. The Importance of Being Earnest is a comedy by _____.A. George Bernard ShawB. Oscar WildeC. Richard Brinsley SheridandD. William Shakespeare96. Aspect of the Novel was originally a series of lectures delivered at Cambridge by _____. It was one of the most important books on the theory of novel.A. E.M. ForsterB. Mark TwainC. William FaulknerD. Henry James97. All the following writers are the great masters of “stream of consciousness” but ____.A. James JoyceB. Virginia WoolfC. William FaulknerD. Henry James98. The novel of Ulysses is a masterpiece of _____.A. James JoyceB. Virginia WoolfC. William FaulknerD. Henry James99. Possessions was written by _____.A. A. S. ByattB. Doris LessingC. Margaret DrabbleD. Anita Brookner100. Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse are novels of “stream of consciousness”written by _____.A. James JoyceB. Virginia WoolfC. William FaulknerD. Henry James91-100: A D A C B A D A A B101. T.S Eliot is most famous for _____A. The Waste LandB. A VisionC. The Unknown CitizenD. The North Ship102. William Butler Yeats is the writer of the following works but _____.A. A VisionB. The Waste LandD. Responsibilities103. Murder on the Orient Express is written by _____ a novelist of detective fiction.A. Arthur Conan DoyleB. Edgar Allan PoeC. Agatha ChristieD. John Fowels104. Death on the Nile is written by _____ a novelist of detective fiction.A. Arthur Conan DoyleB. Edgar Allan PoeC. Agatha ChristieD. John Fowels105. A Handful of Dust was _____ best novel and it took its title from T.S. Eliot’s The Waster Land (I have seen fear in a handful dust ) and it was a modern Gothic comic-tragedy.A. Graham Greene’sB. Evelyn Waugh’sC. Robert Graves’D. John Fowels’106. Robert Graves wrote all the following novels except _____.A. I, ClaudiusB. Claudius the God and His Wife MessalinaC. Count BelisariusD. The Power and the Glory107. The Power and the Glory was written by _____.A. Graham GreeneB. Evelyn WaughC. Robert Graves108. Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty Four were written by _____.A. George OrwellB. William GoldingC. Graham GreeneD. Robert Graves109. Which of the following group of authors is sometimes referred to as belonging to the “angry young man”?A. Ernest Hemingway, John SteinbeckB. Kingsley Amis, John WainC. Willaim Golding, John SteinbeckD. John Wain, Willaim Golding110. _____ is the representative work of the school of “the angry young man”.A. Lucky Jim by Kingsley AmisB. Jim by Rudyard KiplingC. Lord Jim by Joseph ConradD. Heart of Darkness101-110: A B C C B D A A B A111. As a literary figure, Stephen Dedalus appears in two novels by _____.A. D. H. LawrenceB. John GalsworthyC. George EliotD. James Joyce112. The French Lieutenants Woman is the masterpiece of _____.A. John FowlesB. Doris LessingC. Muriel SparkD. Joseph Conrad113. The Golden Notebook was written by _____.A. John FowlesB. Doris LessingC. Muriel SparkD. Joseph Conrad114. Waiting for Godot is a (an) _____ by Samuel Beckett.A. novelB. poemC. playD. essay115. “Kitchen sink realism” is referred to as the works of _____.A. novelB. poemC. playD. essay116. Seamus Heaney won the Nobel Prize of literature in 1995 and most of his poems focused on the _____.A. city lifeB. legendC. countryD. history117. An article on “the Observer” describes th e bursting of all these young _____as a kind of “the movement”.A. poetsB. playwrightC. novelistD. critic118. The novel _____ told a story of a Nazi war criminal. In this novel Martin Amis set the narrative clock in reverse.A. Money: a suicide NoteB. Time’s ArrowC. London FieldsD. Dead Bodies119. Satanic Verse was written by _____ who was born in a Muslin family in Bombay, India.A. Salman RushdieB. Kazuo IshguroC. Julian BarnesD. Grahm Swife120. The novel The Remains of the Day won the Booker Prize for its author_____ who was born in Japan.A. Salman RushdieB. Kazuo IshguroC. Julian BarnesD. Grahm Swife111-120: D A B C C C A B A B。

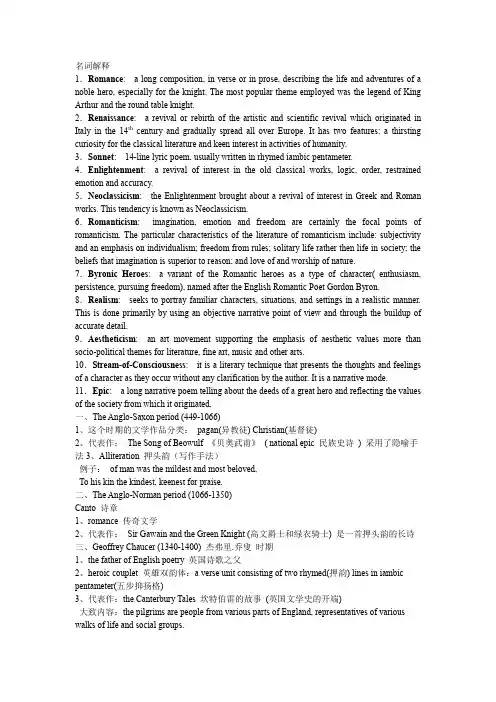

名词解释1.Romance: a long composition, in verse or in prose, describing the life and adventures of a noble hero, especially for the knight. The most popular theme employed was the legend of King Arthur and the round table knight.2.Renaissance: a revival or rebirth of the artistic and scientific revival which originated in Italy in the 14th century and gradually spread all over Europe. It has two features: a thirsting curiosity for the classical literature and keen interest in activities of humanity.3.Sonnet: 14-line lyric poem, usually written in rhymed iambic pentameter. 4.Enlightenment: a revival of interest in the old classical works, logic, order, restrained emotion and accuracy.5.Neoclassicism: the Enlightenment brought about a revival of interest in Greek and Roman works. This tendency is known as Neoclassicism.6.Romanticism: imagination, emotion and freedom are certainly the focal points of romanticism. The particular characteristics of the literature of romanticism include: subjectivity and an emphasis on individualism; freedom from rules; solitary life rather then life in society; the beliefs that imagination is superior to reason; and love of and worship of nature.7.Byronic Heroes: a variant of the Romantic heroes as a type of character( enthusiasm, persistence, pursuing freedom), named after the English Romantic Poet Gordon Byron. 8.Realism: seeks to portray familiar characters, situations, and settings in a realistic manner. This is done primarily by using an objective narrative point of view and through the buildup of accurate detail.9.Aestheticism: an art movement supporting the emphasis of aesthetic values more than socio-political themes for literature, fine art, music and other arts.10.Stream-of-Consciousness: it is a literary technique that presents the thoughts and feelings of a character as they occur without any clarification by the author. It is a narrative mode. 11.Epic: a long narrative poem telling about the deeds of a great hero and reflecting the values of the society from which it originated.一、The Anglo-Saxon period (449-1066)1、这个时期的文学作品分类:pagan(异教徒) Christian(基督徒)2、代表作:The Song of Beowulf 《贝奥武甫》( national epic 民族史诗) 采用了隐喻手法3、Alliteration 押头韵(写作手法)例子:of man was the mildest and most beloved,To his kin the kindest, keenest for praise.二、The Anglo-Norman period (1066-1350)Canto 诗章1、romance 传奇文学2、代表作:Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (高文爵士和绿衣骑士) 是一首押头韵的长诗三、Geoffrey Chaucer (1340-1400) 杰弗里.乔叟时期1、the father of English poetry 英国诗歌之父2、heroic couplet 英雄双韵体:a verse unit consisting of two rhymed(押韵) lines in iambic pentameter(五步抑扬格)3、代表作:the Canterbury Tales 坎特伯雷的故事(英国文学史的开端)大致内容:the pilgrims are people from various parts of England, representatives of various walks of life and social groups.朝圣者都是来自英国的各地的人,代表着社会的各个不同阶层和社会团体小说特点:each of the narrators tells his tale in a peculiar manner, thus revealing his own views and character.这些叙述者以自己特色的方式讲述自己的故事,无形中表明了各自的观点,展示了各自的性格。

American Literature Lecture One 060511/2, 9th Nov. 2009Part I. IntroductionPart I: introduction questions1.Teaching schemes, examination, requirements, advice, contacts, and so on2.What is literature?3.How to define American Literature?4.How to study literature?1. What is literature?1)The definition of 14th century:It means polite learning through reading. A man of literature or a man of letters = a man of wide reading, “literacy”2)The definition of 18th century:practice and profession of writing3)The definition of 19th century:the high skills of writing in the special context of high imagination4)Robert Frost’s definition:performance in words5)Modern definition:We can define literature as language artistically used to achieve identifiable literary qualities and to convey meaningful messages. Literature is characterized by beauty of expression and form and by universality intellectual and emotional appeal.2. How to define the American literatureAmerican literature mainly refers to literature produced in American English by the people living in the United States.3. How to study literatureHistorical Perspectives: Biographical-Historical and Moral-Philosophical.(Diverse Types of Historicisms: including Feminist, Sociological or Marxian Studies of Language, Literature and Translation)Structuralist Perspectives: Looking for Systematic Deep Structures both in Form and Content.(Semiotics, TG Grammar, Systematic/Functional Grammar, Narratology, Freudian psycho-analysis, Russian Formalism, Anglo-American New Criticism, Archetypalism, Myth Criticism, Structural Marxism, Ideology)Poststructuralist or Postmodern Perspectives: Deconstructing Structuring Binaries (No Clear Distinction between Form and Content)[Postmodern Feminism, Postcolonialism, Postmodern Narratologies, New Historicism, Ideological Studies, Discourse Analysis, Reception Theories, Trauma Studies, Trans-Atlantic Studies, Transnationalism, Eco-criticism, Cultural Pathology, and other Postmodernisms]Approaches on Literature1. The Traditional Approaches:1)Analytical ApproachBe familiar with the elements of a literary work, eg: plot, character, setting, point of view, structure, style, atmosphere, theme, etc; answer some basic questions about the text itself.2)Thematic Approach“What is the story, the poem, the play or the essay about?”3)Historical - Biographical Approach4)Moral - Philosophical Approach.2.The Formalistic AppoachStructuralism, Poststructuralism, Semiotics3.The Psychological Approach: Freud4.Mythological and Archetypal Approach5.Feminist Approaches6.Sociological Approach7.Deconstruction8.Phenomenology, Hermeneutics, Reception Theory9.Cultural CriticismAmerican MulticultualismThe New Historicism, British Cultural Materialism10.Additional Approaches:①Aristotlian Criticism②Genre Criticism③Rhetoric, Linguistics, and Stylistics④The Marxist Approach⑤Ecological Criticism⑥Post ColonialismLecture Two 060511/2, 10th Nov. 2009Part II. The periods of American literature①The colonial period (约1607 - 1765)②The period of Enlightenment and the Independence War (1765 -1800)③The romantic period (1800 - 1865)④The realistic period (1865 - 1914)⑤The period of modernism (1914 - 1945)⑥The Contemporary Literature (1945 - 2000)1.The colonial period (约1607 - 1765)The main featuresPuritanism2.The period of Enlightenment and the Independence War (1765 -1800)Benjamin Franklin3.The romantic period (1800 - 1865)1)The early romanticismWashington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper2)“New England Transcendentalism” or “American Renaissance (1836 - 1855)”Emerson, Thoreau/ Whitman, Dickinson/ Hawthorne, Melville , Allan Poe3)“New England Poets” or “Schoolroom Poets”Bryant/ Longfellow/ Lowell/ Holmes/ Whittier4) The Reformers and AbolitionistsBeecher Stowe/ Frederick Douglass4.The realistic period (1865 - 1914)1)Midwestern RealismWilliam Dean Howells2)Cosmopolitan NovelistHenry James3)Local ColorismMark Twain4)NaturalismStephen Crane/ Jack London/ Theodore Dreiser5)The “Chicago School” of PoetryMasters/ Sandburg/ Lindsay/ Robinson6)The Rise of Black American LiteratureWashington/ Du Bois/ Chestnutt5.The period of modernism (1914 - 1945)1)Modern poetry: experiments in form (Imagism)Ezra Pound/ T.S.Eliot/ Robert Frost/ Wallace Stevens/ Carlos Williams2)Prose Writing: modern realism (the Lost Generation)F.Scott Fitzgerald/ Ernest Hemingway/ William Faulkner3)Novels of Social AwarenessSinclair Lewis/ Dos Passos/ John Steinbeck/ Richard Wright4)The Harlem RenaissanceLangston Hughes/ Zora Neals Hurston5)The Fugitives and New Criticism6)The 20th Century American DramaEugene O’ Neil6.The Contemporary Literature (1945 - 2000)I.American Poetry Since 1945: the Anti-traditionII.American Prose Since 1945: Realism and Experimentation.I. Poetry:1)Traditionalism2)Idiosyncratic poets3)Experimental poetry4)Surrealism and Existentialism5)Women and Multiethnic poets6)Chicano / Hispanic / Latino poetry7)Native American poetry8)African-American poetry9)Asian-American poetry10)New DirectionsExperimental Poetry:1)The Black Mountain School2)The San Francisco School3)Beat Poets4)The New York SchoolII. Prose:1.The Realist Legacy and the Late 1940s2.The Affluent but Alienated 1950s3.The Turbulent but Creative 1960s4.The 1970s and 1980s: New Directions1.The Realist Legacy and the Late 1940s1)Robert Penn Warren2)Arthur Miller3)Tennessee Williams4)Katherine Anne Porter5)Eudora Welty2.The Affluent But Alienated 1950s1)John O’Hara2) James Baldwin3) Ralph Waldo Ellison4) Flannery O’Conner5) Saul Bellow6) Bernard Malamud7) Isaac Bashevis Singer8) Vladimir Nabokov9) John Cheever10) John Updike11) J.D.Salinger12) Jack Kerouac3. The Turbulent but Creative 1960s1) Thomas Pynchon2) John Barth3) Norman Mailer4. The 1970s and 1980s: New Directions1) John Gardner2) Toni Morrison3) Alice WalkerPart II. Early American and Colonial Period to 17651. Introduction1. Instead of beginning with folk tales and songs the American literature began with abstractions and proceededfrom philosophy to fiction because there were no written literature among the more than 500 different Indian languages and tribal cultures that existed in North America before the first Europeans arrived there and set up the first colony Jamestown in about 1607.2. American writing began with the work of English adventurers and colonists in the New World chiefly for thebenefit of readers in the mother country. Some of these early works reached the level of literature, as in the robust and perhaps truthful account of his adventures by Captain John Smith and the sober, tendentious journalistic histories of John Winthrop and William Bradford in New England. From the beginning, however, the literature of New England was also directed to the edification and instruction of the colonists themselves, intended to direct them in the ways of the godly.3. Therefore the writing in this period was essentially two kinds: (1) practical matter-of-fact accounts of farming,hunting, travel, etc. designed to inform people “at home” what life was like in the new world, and, often, to induce their immigration; (2) highly theoretical, generally polemical, discussions of religious questions.4. Furthermore, the influential Protestant work ethic, reinforced by the practical necessities of a hard pioneer life,inhibited the development of any reading matter designed simply for leisure-time entertainment.It is the belief that work itself is good in addition to what it achieves; that time saved by efficiency or goodfortune should not be spent in leisure but in doing further work; that idleness is always immoral and likely to lead to even worse sin since “the devil finds work for idle hands to do”. This belief late r developed into the American philosophic idea Puritanism.5. divines who wrote furiously to set forth their views was to defend and promote visions of the religious state. They set forth their visions —in effect the first formulation of the concept of national destiny —in a series ofimpassioned histories and jeremiads from Providence (1654) to Cotton Mather ’s epic Magnalia Christi Americana6. Even Puritan poetry was offered uniformly to the service of God. Michael Wigglesworth ’s Day of Doom (1662) wasuncompromisingly theological, and Anne Bradstreet ’s poems, issued as The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America (1650), were reflective of her own piety. The best of the Puritan poets, Edward Taylor , whose work was not published until two centuries after his death, wrote metaphysical verse,Sermons and tracts poured forth until austere Calvinism found its last utterance in the words of Jonathan Edwards . In the other colonies writing was usually more mundane and on the whole less notable, though the journal of the Quaker John Woolman is highly esteemed, and some critics maintain that the best writing of the colonial period is found in the witty and urbane observations of William Byrd , a gentleman planter of Westover, Virginia.2. The Main Features of this period1) American literature grew out of humble origins. diaries, histories, journals, letters, commonplace books, travelbooks, sermons, in short, personal literature in its various forms, occupy a major position in the literature of the early colonial period.2) In content these early writings served either God or colonial expansion or both. In form, if there was any format all, English literary traditions were faithfully imitated and transplanted.3) The Puritanism formed in this period was one of the most enduring shaping influences in American thought andAmerican literature.3. Puritanism1) Simply speaking, American Puritanism just refers to the spirit and ideal of puritans who settled in the NorthAmerican continent in the early part of the seventeenth century because of religious persecutions. In content it means scrupulous moral rigor, especially hostility to social pleasures and indulgences, that is strictness,sternness and austerity in conduct and religion.2) With time passing it became a dominant factor in American life, one of the most enduring shaping influences inAmerican thought and American Literature. To some extent it is a state of mind, a part of the national cultural atmosphere that the American breathes, rather than a set of tenets.3) Actually it is a code of values, a philosophy of life and a point of view in American minds, also a two-facetedtradition of religious idealism and level-headed common sense.Part III. The period of Enlightenment and the Independence War (1765 -1800)I. Introduction1) The 18th-century American enlightenment as a movement marked by an emphasis on rationality rather thantradition, scientific inquiry instead of unquestioning religious dogma, and representative government in place of monarchy.2) Enlightenment thinkers and writers, such as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine, were devoted to the idealsof justice, liberty, and equality as the natural rights of man.3) In these period with the exception of outstanding political writing, such as Common sense, Declaration ofIndependence, The Federalist Papers and so on, few works of note appeared. Even if there appeared poetry and fiction, they were full of imitativeness and vague universality. So most Americans were painfully aware of their excessive dependence on English literary models. The search for a native literature became a national obsession.4) Despite these we should pay attention to several points in this period:William Hill Brown (1765-1793) published the first American novel The Power of Sympathy in 1789.Charles Brockden Brown (1771-1810) was the first American author to attempt to live from his writing. Hedeveloped the genre of American Gothic.The Dictionary edited by Noah Webster (1758-1843) based the American lexicography. Updated Webster’sdictionaries are still standard today.Philip Freneau’s (1752-1832) was known as "the poet of the American Revolution". His major themes are death, nature, transition, and the human in nature. All of these themes become important in 19th century writing. All the while...in romanticizing the wonders of nature in his writings...he searched for an American idiom in verse. II. Benjamin Franklin1706 - 1790(An Extraordinary Life and An Electric Mind)1. His Life1)Born the tenth of fifteen children in a poor candle and soap maker’s family, he had to leave school before he waseleven.2)At twelve he was apprenticed to an older brother, James, a printer in Boston.3)As a voracious reader he managed to make up for the deficiency by his own effort and began at 16 to publishessays under the pseudonym, Silence Dogood, essays commenting on social life in Boston.4)When he was 17 he ran away to Philadelphia to make his own fortune marking the beginning of a long successstory of an archetypal kind.5)He set himself up as an independent printer and publisher, found the Junto Club and subscription library,issued the immensely popular Poor Richard’s Almanac.6)Retired around forty-two, he did what was to him a great happiness: read, make scientific experiments and dogood to his fellowmen. He helped to find the Pennsylvania Hospital, an academy which led to the University of Pennsylvania, and the American Philosophical Society.7)At the same time he did a lot of famous experiments and invented many things such as volunteer firedepartments, effective street lighting, the Franklin Stove, bifocal glasses, efficient heating devices, lightning-rod and so on.8)Beginning his public career in the early fifties, he became a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly, the DeputyPostmaster-General for the colonies, and for some eighteen years served as representative of the colonies in London.9)During the War of Independence, he was made a delegate to the Continental Congress and a member of thecommittee to write the Declaration of Independence. One of the makers of the new nation, he was instrumental in bringing France into an alliance with America against England, and played a decisive role at the Constitutional Convention.2. Major Works1)Poor Richard’s AlmanacMaxims(谚语,格言)and axioms(哲理,格言)a)Lost time is never found again.b) A penny saved is a penny earned.c)God help them that help themselves.d)Fish and visitors stink in three days.e)Early to bed, and early to rise, makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.f)Ale in, truth out.g)Eat not to dullness. Drink not to elevation.h)Diligence is the Mother of Good Luck.i)One Today is worth two tomorrow.j)Industry pays debts. Despair encreaseth them.2)Autobiographya.It is perhaps the first real post-revolutionary American writing as well as the first real autobiography in English.b.It gives us the simple yet immensely fascinating record of a man rising to wealth and fame from a state ofpoverty and obscu rity into which he was born, the faithful account of the colorful career of America’s first self-made man.c.First of all, it is a puritan document. The most famous section describes his scientific scheme of self-examinationand self-improvement.d.It is also an eloquent elucidation of the fact that Franklin was spokesman for the new order of eighteenthcentury enlightenment, and that he represented in America all its ideas, that man is basically good and free, by nature endowed by God with certain inalienable rights of liberty and the pursuit of happiness.e.It is the pattern of Puritan simplicity, directness, and concision. The plainness of its style, the homeliness ofimagery, the simplicity of diction, syntax and expression are some of the salient features we cannot mistake.3. Evaluation1)He was a rare genius in human history. Nature seemed particularly lavish and happy when he was shaped.Everything seems to meet in this one man, mind and will, talent and art, strength and ease, wit and grace, and he became almost everything: a printer, postmaster, citizen, almanac maker, essayist, scientist, inventor, orator, statesman, philosopher, political economist, ambassador, musician and parlor man.2)He was the first great self-made man in America, a poor democrat born in an aristocratic age that his fineexample helped to liberalize.3)Politically he brought the colonial era to a close. For quite some time he was regarded as the father of allYankees, even more than Washington was. He was the only American to sign the four documents that created the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the treaty of alliance with France, the treaty of peace with England, and the constitution.4)Scientifically, as the symbol of America in the Age of Enlightenment, he invented a lot of useful implements. Hisresearch on electricity, his famous experiment with his kite line and many others made him the preeminent scientist of his day.5)Literally, he really opened the story of American literature. D. H. Lawrance agreed that Franklin waseverything but a poet. In the Scottish philosopher David Hume’s eyes he was America’s “first great man of letters”.Assignment: Please read the material by Ralph Waldo EmersonLecture Three 060511/2, 16th Nov. 2009The American Romanticism(I)I. What is RomanticismSimply speaking, Romanticism is a literary movement flourished as a cultural force throughout the 19th C and it can be divided into the early period and the late period. Also it remains powerful in contemporary literature and art.Romanticism, a term that is associated with imagination and boundlessness, as contrasted with classicism, which is commonly associated with reason and restriction. A romantic attitude may be detected in literature of any period, but as an historical movement it arose in the 18th and 19th centuries, in reaction to more rational literary, philosophic, artistic, religious, and economic standards.... The most clearly defined romantic literary movement in the U. S. was Transcendentalism.The representatives of the early period includes Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper, and those of the late period contain Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Walt Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe.II. The reasons on the rise of American RomanticismInternal causes:1)American burgeoned into a political, economic and cultural independence. Democracy and political equalitybecame the ideals of the new nation. Radical changes came about in the political life of the country. Parties began to squabble and scramble for power, and new system was in the making.2)The spread of industrialism, the sudden influx of immigration, and the pioneers pushing the frontier furtherwest, all these produced something of an economic boon and, with it, a tremendous sense of optimism and hope among the people.3)Ever-increasing magazines played an important role in facilitating literary expansion in the country.External causes:1)Foreign influences added incentive to the growth of romanticism in America.2)The influence of Sir Walter Scott was particularly powerful and enduring.III. Characteristics of American Romanticism (b)1)Sentimentalism, primitivism and the cult of the noble savage2)Political liberalism3)The celebration of natural beauty and the simple life4)Introspection5)The idealization of the common man, uncorrupted by civilization6)Interest in the picturesque past and remote places7)Antiquarianism8)Individualism9)Morbid melancholy10)Historical romanceIV. The Representatives of the early American romanticismA. Washington Irving(1783-1859 )1. About the Author1)Washington Irving was born in New York City on April 3, 1783 as the youngest of 11 children. His parents,Scottish-English immigrants, were great admirers of General George Washington, and named their son after their hero.2)Early in his life Irving developed a passion for books. He studied law privately but practiced only briefly. From1804 to 1806 he travelled widely in Europe. After returning to the United States, Irving was admitted to the New York bar in 1806.3)He was a partner with his brothers in the family hardware business and representative of the business inEngland until it collapsed in 1818. During the war of 1812 Irving was a military aide to New York Governor Tompkins in the U.S. Army.4)Irving's career as a writer started in journals and newspapers. His success in social life and literature wasshadowed by a personal tragedy because his engaged love died at the age of seventeen. So he never married or had children.5)After the death of his mother, Irving decided to stay in Europe, where he remained for seventeen years from1815 to 1832.6)In 1832 Irving returned to New York to an enthusiastic welcome as the first American author to have achievedinternational fame. Between the years 1842-45 Irving was the U.S. Ambassador to Spain.7)Irving spent the last years of his life in Tarrytown. From 1848 to 1859 he was President of Astor Library, laterNew York Public Library. Irving's later publications include Mahomet And His Successors(1850), Wolfert's Roost(1855), and his five-volume The Life of George Washington(1855-59). Irving died in Tarrytown on November 28, 1859.2. His Major Works1)His earliest work was a sparkling, satirical History of New York (1809) under the Dutch, ostensibly written byDiedrich Knickbo cker (hence the name of Irving’s friends and New York writers of the day, the “Knickbocker School”.)2)The Sketch Book (1819-20 as Geoffrey Crayon) - contains 'Rip Van Winkle' and 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow'3)The Life of George Washington (1855-59, five volumes)3. Evaluation to him1)American author, short story writer, essayist, poet, travel book writer, biographer, and columnist. Irving hasbeen called the father of the American short story. He is best known for 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,' in which the schoolmaster Ichabold Crane meets with a headless horseman, and 'Rip V an Winkle,' about a man who falls asleep for 20 years.2)The first American writer of imaginative literature to gain international fame, so he was regarded as father ofAmerican literature.3)The short story as a genre in American literature probably began with Irving’s The Sketch Book, ACOLLECTION OF ESSAYS, SKETCHES, AND TALES. It also marked the beginning of American Romanticism.B. James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851)1. His Major WorksIn his life Cooper wrote over thirty novels which can be divided into frontier novels, detective novels and reference novels. He considered The Pathfinder (1840) and The Deerslayer (1841) his best works.The unifying thread of the five novels collectively known as the Leather-Stocking Tales is the life of Natty Bumppo. Cooper’s finest achievement, they constitute4 a vast prose epic with the North American continent as setting. Indian tribes as Characters, and great wars and westward migration as social background. The novels bring to life frontier America from 1740 to 1804.1)The Pioneers(1823): Natty Bumppo first appears as a seasoned scout in advancing years, with the dyingChingachgook, the old Indian chief and his faithful comrade, as the eastern forest frontier begins to disappear and Chingachgook dies.2)The Last of the Mohicans(1826): An adventure of the French and Indian Wars in the Lake George county.3)The Prairie(1827): Set in the new frontier where the Leatherstocking dies.4)The Pathfinder(1840): Continuing the same border warfare in the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario county.5)The Deerslayer(1841): Early adventures with the hostile Hurons on Lake Otsego, NY.2. Contributions of CooperThe creation of the famous Leatherstocking saga has cemented his position as our first great national novelist and his influence pervades American literature. In his thirty-two years (1820-1851) of authorship, Cooper produced twenty-nine other long works of fiction and fifteen books - enough to fill forty-eight volumes in the new definitive edition of his Works. Among his achievements:1)The first successful American historical romance in the vein of Sir Walter Scott (The Spy, 1821).2)The first sea novel (The Pilot, 1824).3)The first attempt at a fully researched historical novel (Lionel Lincoln, 1825).4)The first full-scale History of the Navy of the United States of America (1839).5)The first American international novel of manners (Homeward Bound and Home as Found, 1838).6)The first trilogy in American fiction (Satanstoe, 1845; The Chainbearer, 1845; and The Redskins, 1846).7)The first and only five-volume epic romance to carry its mythic hero - Natty Bumppo - from youth to old age. 3. His Skills1)He is good at making plots.2)All his novels are full of myths.3)He had never been to the frontier and among the Indians and yet could write five huge epic books about them isan eloquent proof of the richness of his imagination.4)He created the first Indians to appear in American fiction and probably the first group of noble savages.5)He hi t upon the native subject of frontier and wilderness, and helped to introduce the “Western” tradition intoAmerican literature.V. American Renaissance1. The Concept1)It also called New England Renaissance period from the 1830s roughly until the end of the American CivilWar in which American literature, in the wake of the Romantic movement, came of age as an expression of a national spirit.2)The literary scene of the period was dominated by a group of New England writers, the “Brahmins”. They werearistocrats, steeped in foreign culture, active as professors at Harvard College, and interested in creating a genteel American literature based on foreign models.3)One of the most important influences in the period was that of the Transcendentalists, including Emerson,Thoreau and so on.4)The Transcendentalists contributed to the founding of a new national culture based on native elements. Theyadvocated reforms in church, state, and society, contributing to the rise of free religion and the abolition movement and to the formation of various utopian communities, such as Brook Farm. The abolition movement was also bolstered by other New England writers, including the Quaker poet Whittier and the novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) dramatized the plight of the black slave.5)Apart from the Transcendentalists, there emerged during this period great imaginative writers—NathanielHawthorne, Herman Melville, and Walt Whitman—whose novels and poetry left a permanent imprint on American literature. Contemporary with these writers but outside the New England circle was the Southern genius Edgar Allan Poe, who later in the century had a strong impact on European literature.Lecture Four The American Romanticism(II)TranscendentalismIt is a 19th-century movement of writers and philosophers in New England who were loosely bound together by adherence to an idealistic system of thought.Emerson defined it as “idealism” simply. In reality it was far more complex collection of beliefs: that the spark of divinity lies within man; that everything in the world is a microcosm of existence; that the individual soul is identical to the world soul, or Over-Soul. By meditation, by communing with nature, through work and art, man could transcend his senses and attain an understanding of beauty and goodness and truth.In application, American transcendentalism urged a reform in society, and that such a reform may be reached if individuals resist customs and social codes, and rely rather on reason to learn what is right. Ultimately, transcendentalists believed that one should transcend society's code of ethics and rely on personal intuition in order to reach absolute goodness, or Absolute Truth.It was indebted to the dual heritage of American Puritanism. That is to say, it was in actuality romanticism on the puritan soil.Transcendentalism dominated the thinking of the American Renaissance, and its resonance reverberated through American life well into the 20th century. In one way or another American most creative minds were drawn into its thrall, attracted not only to its practicable messages of confident self-identity, spiritual progress and social justice, but also by its aesthetics, which celebrated, in landscape and mindscape, the immense grandeur of the American soul.The Representativesof American RenaissanceI. The Essayists1)Ralph Waldo Emerson2)Henry David ThoreauRalph Waldo Emerson(1803 - 1882)1.His philosophy:1)Strongly he felt the need for a new national vision.2)He firmly believes in the transcendence of the Oversoul and thought that the universe was composed of Nature。