Anderson-founding family ownership and performance

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:635.50 KB

- 文档页数:29

UNIT31.Which of the following statements was correct around the time of the American Revolution? The American had the mixed blood of Europeans or their descendants.2. Which of the following was NOT one of the three forces that led to the modern development of Europe?The spiritual leadership of the Roman Catholic Church.3. The following were the main Reformation leaders exceptMartin Luther King4. The following were some of the characteristics of Protestantism exceptsalvation through the church.5. Which of the following American values did NOT come from Puritanism?separation of state and church.6. Lord Baltimore's feudal plan failed becausethe English king did not like the plan.7. The following were the founding fathers of the American Republic exceptWilliam Penn.8. The theory of American politics and the American Revolution originated mainly fromJohn Locke.9. Which of the following was NOT a denomination of Protestantism?Catholics.10. "No taxation without representation" was the rallying cry of “the people of the 13 colonies on the eve of the American Revolution.UNIT41. Which of the following statements was NOT correct? When the War of Independence was over, the relationships between the states and the national government were clearly defined.2. According to the author, the Articles of Confederation failed because of the following reasons. Which is not true?Some new states wanted to be free from the Union.3. Which of the following states refused to participate in the Constitutional Convention?Rhode Island.4. Which of the following statements was NOT correct? When the Constitution was written,t here was a Bill of Rights in the Constitution.5. Which of the following is the only branch that can make federal laws, and levy federal taxes? The legislative.6.Which of the following is NOT a power of the president?The president can make laws.7. The Bill of Rights consists of10 amendments added to the Constitution in 1791.8. Which of the following is NOT guaranteed in the Bill of Rights?The freedom of searching a person's home by police.9. The following were NOT written into the Constitution in 1787 exceptthe powers of the president.10. The New Deal was started byFranklin Roosevelt.UNIT 51. The first factory in the United States was a cotton textile mill in Pawtucket, in the state of Rhode Island.2. The “American system” of mass production was first used in United States.firearms industry3. The United States had the first standard paper currency in 1863.4. In which year was the United States rated NO.1 in terms of production capacity in the world? 19455. Which of the following is NOT considered as part of the service industry?Steelmaking6. The United States was rated forth in the world in terms of land area and the size of population.7. The United States produces as much as half of the world’ssoybeans and corn.8. Which of the following is generally considered as an important institutional factor that contributed to the success of American business and industry?Laissez-faire9. Who has extolled the virtues of farmers?Thomas Jefferson10. The latest technology that farmers have adopted iscomputersUNIT61. Which of the following was NOT a Protestant denomination?The Catholics2. Which of the following is unconstitutional in the United States?Public money is provided to support religious schools.3. Which of the following is NOT regarded as one of the three basic religious beliefs?Islamic4. Which of the following is true?Liberal Protestants and Jews join non-believers in maintaining that abortion is a basic right for women,5. Which of the following continues to have an all-male clergy?The Catholic Church6. Which of the following features is NOT distinctively American?There has been very much concentration on doctrine or religious argument in the US. 7. In the United States, people go to church mainly for the following reasons except for finding a job in society.8. Which of the following statement is NOT correct according to the author?Protestant Church is an established church by law in the US.UNIT 71. Which of the following was a writer of the post-Revolutionary period?Washington Irving2. Which of the following is considered an American masterpiece?Moby Dick3. Which of the following was written by Henry David Thoreau?Walden4. Whitman’s poetry has the following characteristics exceptfragmented haunting images5. Mark Twain’s work are characterized by the following exceptegotism6. Three of the following are characteristics of Emily Dickinson’s poems. Which one is NOT? Her poems are very long and powerful.7. Henry James was mainly interested in writing about American living in Europe.8. Sherwood Anderson is NOT included in the group of naturalists.9. Three of the following authors are Noble Prize winners. Which one is NOT?F.Scott Fitzgerald.10. John Steinbeck does NOT belong to the ‘Lost Generation’.11. Lig ht in August was NOT written by Hemingway.12. Which of the following is NOT an African-American author?Alan Ginsberg13. The following author were women writers who wrote novels in the 19th and early 20th century with the exception ofWilla Cather14. The following writers represent new American voices exceptT.S.Eliot15. Among the following Native American writers, whose publications are regarded as sparking the beginning of the Native American Renaissance?Scott Momaday’sUNIT 81.Which of the following subjects are NOT offered to elementary school students?Politics and business education.2. The expenditure in American public schools is guided or decided by _______.boards of education3. In the United States school systems, which of the following divisions is true?Elementary school, secondary school.4. Which of the following is NOT mentioned in American higher education?Research institutions5. Three of the following factors have contributed to the flourishing of large universities in America, which is the exception?Large universities offer scholarships to all students.6. The most important reason for students wanting to get into more desirable institutions because they find it easy for them to get jobs after having graduated from one of them7. In order to go to university, secondary school students must meet the following requirements except that _______.they pass the college entrance examinations8. Three of the following universities have large endowments from wealthy benefactors. Which is the exception?The State University of New York9. Both public and private universities depend on the following sources of income except _______. Investment10. To get a bachelor's degree, an undergraduate student is required to do the following except taking certain subjects such as history, language and philosophyUNIT 91. Black American sang the anthem of the civil rights movement, ______affirming their commitment to fight racial prejudice.We Shall Overcome!2. The most notorious terrorist group against black civil rights workers in the South was known as Ku Klux Klan.3. The reason why many young people were involved in the social movements of the 1960s was thatthey resented traditional white male values in US society4. In addition to such tactics as sit-ins, young students also added ______to educate people about war in Vietnam.Teach-in5. According to the author, three civil rights groups provided the leadership, the tactics, and the people to fight against Southern segregation. Which is the exception?The students for a democratic society6. A historic moment of the civil rights movement was the March on Washington of August 28, 1963 when ______delivered his “I Have a Dream”Martin Luther King, Jr.7. In January 1965, President Johnson declared “_______” to eliminate poverty “by opening to everyone the opportunity to live in decency and dignity.”War on poverty8. Unlike Martin Luther King, _______the chief spokesperson of Black Muslins advocated violence in self defense and black pride.Malcolm X9.During the early stages of the civil rights movement, the major integration strategy initiated by the Congress of Racial Equality was known as _____to integrate interstate buses and bus station in the South.Freedom rides10. Due to his firm belief in nonviolent peaceful protest in the spirit of India’s leader Gandhi, _______was awarded the Noble Peace Prize in 1964.Martin Luther King,Jr.11. The one group within the counter culture best known for their pursuit of happiness as their only goal in life was called____the Hippies12. In the 1960s, feminism was reborn. Many women were dissatisfied with their lives, and in 1963, with the publication of _______by _________, they found a voice.The Feminine Mystique, Betty FriedanUNIT 101. Which of the following statement is NOT true about blacks after the 1960s?Blacks felt that they could be fully integrated into the mainstream of American life.2. the main factor contributing to the widening income gap between blacks and whites in the 1970s was _____black had low position and low pay in the workplace hierarchy3. Which of the following is NOT the reason for the higher arrest rates among minority groups? The aggressive nature of these groups.4. Which of the following does NOT belong to the white-collar crime?Robbery5. Which of the following statement is NOT true?The Northern states did not have racial discrimination.6. Accoding to the text, which of the following is NOT a dysfunction caused by drug abuse? Drug abuse is a major cause of unemployment.7. If white-collar crimes were included in the Crime Index, the profile of a typical criminal in the United States would be the following EXCEPTliving near city centers8. Which of the following used human beings as guinea pigs to test drugs like LSD?The CIAUNIT111. When did the word stereotype come into use in English?Early 17th century2. Which organization in the United States demonstrated strongly against any laws that might restrict gun ownership?The NRA (national Rifle Association)3. Which of the following websites are meant to cater to young tastes?Facebook4. Who was the author of the popular play The Melting Pot which was associated with life in America since the late 18th century?Israel Zangwill5. What was the major historical event that resulted in the separation of the Protestants from the Roman Catholic Church?The 16th-century Reformation6. Which of the following expressions represents the core value of the mainstream society in the USA?Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.7. Which of the following was President Franklin D.Roosevelt’s main concern?Social justice8. According to the author, the mosaic metaphor for American image has one fatal flaw. What is it?American is not open to change .9.The internet has several characteristics that reflect life in the USA today. Which one is NOT? People can freely download MP3 music10. Which of the following institution is responsible for the making of the Internet?The US military11. Free use of the Internet in the US responds to the basic American values, except that _____it doesn’t help create material wealth.12. Which of the following helps theorize the concept of Fraternity? Karl Marx。

南京理工大学泰州科技学院毕业设计(论文)外文资料翻译学院(系):商学院专业:会计学姓名:林晟学号: 0706130352外文出处: IGOR FILATOTCHEV. OwnershipConcentration,‘PrivateBenefits of Control’ and DebtFinancing[J].Journal of CorporationLaw,2004,Vol.29.No.4,719-734 附件:1.外文资料翻译译文;2.外文原文。

附件1:外文资料翻译译文审股权集中度,“控制权私人收益”和债务融资IGOR FILATOTCHEV摘要:基于快速成长的'法律和经济’文献,本文分析了主要所有者在以牺牲小股东利益而获取“控制权私人收益”的环境中进行债务融资的公司治理。

这表明,所有权集中是与作为一个公司的负债比率和衡量投资的财政资源的使用效率较低有关,而这并不取决于最大股东的身份,固定的具有支配权的股东可以串通股权持有者进行控股溢价。

这个结论的其中一个可能的结果就是债务市场的企业信贷压缩,这有转型期经济体的证据支持。

关键词:所有权,控制权收益,债务引言有一个大量研究金融经济学和战略管理的文献显示获得控制权私人收益的方式和数量与管理行为和企业业绩有关。

(Gibbs, 1993;Hoskisson et al., 1994;Jensen and Warner, 1988)然而,大多以往的研究集中于大型、公开的在传统的美国/英国公司控制模型的框架范围内分散所有权的上市公司,很少是关于所有权集中的公司治理(Holderness and Sheehan, 1988;Short,1994)。

快速成长的企业所有制结构的优化取决于“控制权私人收益”的水平。

(e.g., Bennedsen and Wol fenzon, 2000; Grossman and Hart, 1988;Harris and Raviv, 1988)。

Point of viewSymbolismReading: Sherwood Anderson, The EggPoint of View: The Narrative Voice•A story must have a plot, characters, and a setting. It must also have a storyteller: a narrative voice, real or implied, that presents the story to the reader.•point of view is the method of narration that determines the position, or angle of vision, from which the story is told. The nature of the relationship between the narrator and the story, the teller and the tale, is always crucial to the art of fiction.First person point of view•He creates an immediate sense of reality. Because we are listening to the testimony of someone who was present at the events described, we are inclined to trust the narrator and to enter into the experience.•A story told in the first person is necessarily limited to what the narrator has seen, heard, or surmised(臆测).The first person narrative:The “I” personaThis narrator may be :•clear-minded or naïve,•reliable or unreliable,•conscious or unaware•is inside the story as a protagonist, or a participant, or an observer.•detached or concerned•close to or remote from the author’s understandingThe third person narrativeIf the narrator is not introduced as a character, and if everything in the work is described in the third person (that is, he, she, it, they), the author is using the third-person point of view. There are three variants: omniscient, limited omniscient, and objective or dramatic.•The surface understanding: or the narrative understanding•The deep understanding: or the authorial understanding•The epiphany: a sudden realization, a sudden manifestation of truththe surface understandingepiphany the narrative gapthe deep understandingSymbolism: A Key to Extended MeaningA symbol, is “something that stands for something else by rea son of relationship, association, convention, or accidental resemblance … a visible sign of something invisible.”•Through the use of symbols the author can achieve indirection in order to avoid being obvious. The symbol implies but does not develop meanings, and the effect is that of compression. •Symbolism is one of the devices that enrich short fiction and compensate for briefness in space. A symbol is a thing that suggests more than its literal meaning.Types of SymbolsUniversal or Cultural SymbolsThey are the common property of a society or culture and are so widely recognized and accepted that they can be said to be almost universal.Contextual, Authorial, or Private SymbolsThey are those symbols whose associations are neither immediate nor traditional; instead, they derive their meaning, largely if not exclusively, from the context of the work in which they are used.Reading: Sherwood Anderson, The EggSherwood Anderson(September 13, 1876 – March 8, 1941) was an American novelist and short story writer.Sherwood Anderson was born in the countryside of Ohio, in the Middle West, one of seven children of a poor laborer who eventually abandoned his family. When he was still a boy, his father moved the family to an ugly factory town. There young Anderson found emotional and cultural desolation; this laid for his later attitude of severe criticism against the “mechanization” of human beings in an industrial culture.Anderson wrote about lonely, sad people, deformed in their characters by frustrations imposed by their societies and environment. Anderson felt compassion for such emotionally stunted people, who were the victims of modern existence, and he made their strange behavior understandable, and exposed their inner sweetness or bitterness.悲剧将人生有价值的东西毁坏给人看。

U NDERSTANDING I NTERNATIONAL T RADE INA GRICULTURAL P RODUCTS:O NE H UNDRED Y EARS OFC ONTRIBUTIONS BY A GRICULTURAL E CONOMISTST IM J OSLING,K YM A NDERSON,A NDREW S CHMITZ,AND S TEFAN T ANGERMANNThe study of international trade in agricultural products has developed rapidly over the pastfifty years.In the1960s the disarray in world agriculture caused by domestic price support policies became thefocus of analytical studies.There followed attempts to measure the distortions caused by policies alsoin developing countries and to model their impact on world agricultural markets.Tools were advancedto explain the trends and variations in world prices and the implications of market imperfections.Challenges for the future include analyzing trade based on consumer preferences for certain productionmethods and understanding the impact of climate change mitigation and adaptation on trade.Key words:agricultural trade;commodity prices;trade policy;agricultural trade distortions;measure-ment of agricultural protection;modeling agricultural trade.JEL Codes:F13,F55,Q17.The study of the economics of international trade in agricultural and food products is a rela-tively new area of specialization in the agricul-tural economics profession.Certainly the three mainstream areas that dominated thefirstfifty years of the American Agricultural Economics Association(AAEA)—production economics, marketing,and policy—each acknowledged the existence of international trade,but they largely ignored the analytical challenge of understanding the behavior of international markets and their role in resource-use effi-ciency and income distribution.By contrast, most agricultural economists trained since the1960s have been exposed to interna-tional trade theory and recognize the per-Tim Josling is Professor Emeritus,Food Research Institute,and Senior Fellow,Freeman Spogli Institute of International Studies, Stanford University.Kym Anderson is the George Gollin Professor of Economics and former executive director of the Centre for International Economic Studies at the University of Adelaide; Andrew Schmitz is the Ben Hill Griffin,Jr.Eminent Scholar and a professor of Food and Resource Economics,University of Florida,Gainesville;a research professor,University of California, Berkeley;and an adjunct professor,University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon.Stefan Tangermann is Professor Emeritus,University of Göttingen and former Director for Trade and Agriculture at OECD.We would like to thank the many members of the Inter-national Agricultural Trade Research Consortium(IATRC)who responded to an informal poll on the most influential writings in agricultural trade in their experience.vasive influence of international economic events on domestic markets and policies. Trade agreements have evolved to where they constrain domestic policy,and interna-tional commodity prices are usually trans-mitted at least to some extent back to the farm level.Even the“newer”areas of agri-cultural and applied economics,such as envi-ronmental and resource economics,develop-ment economics,and consumer economics,are influenced by the institutions of international trade.This review aims to document the growth of the study of international agricultural mar-kets and institutions by identifying some of the main contributions of the profession to our understanding of the key issues.It is a subjective assessment of the development of professional thinking on several of the main areas where contributions have been made to the understanding of the nature of inter-national trade in agriculture and food com-modities.Each of these advances illustrates the cumulative contributions made by economists working in universities and research agen-cies of national and international institu-tions.We apologize at the outset to the many whose work we have not been able to mention.Amer.J.Agr.Econ.92(2):424–446;doi:10.1093/ajae/aaq011Received December2009;accepted January2010©The Author(2010).Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Agricultural and Applied Economics Association.All rights reserved.For permissions,please e-mail:journals.permissions@ at Rijksuniversiteit Groningen on April 26, Downloaded fromJosling et al.Understanding International Trade in Agricultural Products425Changing Trade Issues over the Past Ten DecadesAgricultural economists,by the nature of their discipline,are attracted to the issues of the day. It follows that those who work on international trade issues in the main respond to emerg-ing trade situations that demand analysis and explanation.Theoretical developments and improvements in analytical technique often accompany these attempts to understand and explain current problems.As a backdrop to the more detailed discussion of the contributions of economists to the study of international agri-cultural trade,we therefore begin by tracing the evolution of trade issues over the100years since the founding of theAAEA.This will illus-trate the tumultuous nature of the changes that have called out to be addressed by economists, as well as the dramatic advances in theoretical and analytical tools that have been developed to understand these issues.Agricultural trade historically has been a significant share of total commerce,and for many countries has played a dominant role in determining foreign policy.As late as1890, agricultural exports accounted for75%of the total exports from the United States(Johnson 1977,p.298).By the time the AAEA came into existence in1909,the export share was about 50%,and that share fell steadily until the1940s before reviving in the immediate postwar era to about20%.For the world as a whole,agri-cultural trade has steadily declined as a share of total trade in goods and services and is now less than8%,even though it has been increas-ing faster than world agricultural production. Yet trade in agricultural products remains very important for both high-income and develop-ing countries,and agricultural trade policies typically are among the most sensitive in any international trade negotiations.Thefirst two decades of the AAEA,from 1909to1929,was a period of steady decline in trade from the high point of the nineteenth-century globalization period to the growth of protectionist movements and the collapse of European empires in the devastation of World War I.Though the founding fathers of the AAEA were well aware of the geopol-itics of the period and the impact on agri-cultural tradeflows,few books or articles by agricultural economists stand out as dealing systematically with trade issues during that ernment intervention in agricul-tural markets was not on the horizon,and agricultural tariffs were generally low relative to barriers to trade in manufactured goods and services.During the1920s,the situation began to change.With domestic farm policy emergingas a way to boost rural incomes,pressure grewto use trade policy as part of the strategy.The McNary-Haughen Act was an early attemptto use trade policy to influence domestic mar-kets,and the same trend toward protectionismwas occurring in other countries.1The book by Edwin Nourse(1924)introduced a more holis-tic view of world markets as well as a cogent explanation of their significance for U.S.agri-culture.At this time,trade theorists began to expand on the determinants of trade,and thesignificance of resource endowments emergedas a major factor in the explanation of tradeflows.By the third decade of the AAEA’s exis-tence,trade policy was a matter of high polit-ical interest and international contention.TheGreat Depression was widespread and pro-tracted in part because of increased trade pro-tection,and agricultural trade was not spared.The1930Smoot-Hawley tariff bill was origi-nally designed as an agricultural tariff increasebut ended up more generally applied to all goods.Did the profession sit idly by while theworld trade system disintegrated and economic autarchy reigned?It is not easy tofind sem-inal articles from this period on agriculturaltrade and the collapse of markets,with the notable exception of T.W.Schultz’s,who wroteon world agricultural trade and the serious implications for U.S.markets(Schultz1935).The fourth decade was not one of major contributions to the agricultural economics lit-erature in the area of trade.Wartime condi-tions were not conducive to academic pursuits,since many members of the profession wereco-opted into government posts and presum-ably made contributions that may never be revealed.2However,the postwar trading sys-tem was being constructed in the1940s,and agricultural issues were often at the heart of the discussion.3The debates between such notable economists as James Meade and Keynes and1Agricultural economists commented on these issues,in the con-texts of both domestic policy and the trade system.Afine exampleis the study by Black(1928),who warned of the consequences ofthis policy.2An exception was Henry C.Taylor’s book on world agriculturaltrade,emphasizing the importance of the European market(Taylorand Taylor1943).3The debate on managing commodity markets is an example;see the discussion below of the writings by Davis(1942)and Tsouand Black(1944).at Rijksuniversiteit Groningen on April 26, Downloaded from426April2010Amer.J.Agr.Econ.their American counterparts explicitly dealt with the inclusion of agricultural trade in the postwar system but were notable for their assumption that these issues were of such a high political importance that the arguments for freer markets were unlikely to prevail.Mean-while the theory of international trade took major steps forward:Samuelson’s(1948)arti-cle on factor price equalization appeared,and the basis was laid for modern trade theory. The decade of the1950s saw the start of a serious professional interest in agricultural and commodity trade.D.Gale Johnson published a book on the inconsistency between U.S.trade and agricultural policies:the one advocating open markets,the other maintaining protec-tive barriers(Johnson1950).For twenty years Johnson refined this message and had a pro-found impact on the profession(if not on policy),as is detailed below.Condliffe(1951) included some insightful comments about agri-cultural trade in his book The Commerce of Nations,in addition to showing the complexi-ties of trade regulations at that time(Condliffe 1951).4The link between commodity trade and economic development and growth also began to be considered during this period.In fact this was the start of development economics as the colonial system disintegrated.Even the begin-nings of the political economy of agricultural trade can be traced to this period.Kindleberger (1951)introduced interest-group analysis into the explanation of national tariff policies,set-ting the stage for later political economy work on agricultural trade.By the start of the1960s the issue of agri-cultural commodity trade became a significant international concern.The1960s saw sharp increases in agricultural protection in indus-trial countries.The trade system staggered under the burden of the disposition of sur-pluses built up under high price supports. Developing countries saw a different side of this with their requests for market access(on concessional terms)rebuffed by strong domes-tic political forces and their export earnings depressed by low commodity prices in interna-tional markets.Much of the professional writ-ing in the United States on agricultural trade in 4Condliffe influenced a generation of students at Berkeley, including Hillman,who began to ask systematic questions about the issues facing agricultural trade.Hillman(1996)shows some frus-tration over the lack of earlier studies on trade,declaring:“[A]bout the only works relating to agricultural trade were a1920s book by Nourse and Gale Johnson’s work on the trade policy dilemma of US agriculture.”this period focused on how to increase exports,either commercially or through food aid.The1960s saw another development thathas had a profound impact on agricultural trade:the rebirth of regional economic integra-tion and somewhat less ambitious free trade areas.European economists,as well as theirNorth American counterparts,were intriguedby the bold experiment of the European Eco-nomic Community(EEC)but were concernedabout the protectionist Common AgriculturalPolicy(CAP)that formed an integral partof the agreement.The tensions between theEEC(later the EU)and the United Statesover agricultural trade were a major theme for economists during this period and indeed untilthe mid-1990s,when the World Trade Orga-nization(WTO)internalized some of theseconflicts.Both trade theory and the theory of eco-nomic integration were developing rapidly,asreal-world events challenged accepted expla-nations.In the1960s,trade theorists paid increasing attention to international capital movements within the context of standardtrade theory:Capital movements could be a substitute for product trade.5Agricultural eco-nomics as a whole stuck close to its microeco-nomic roots and to a“closed economy”viewof the agricultural sector.There was still a dis-connect between the teaching of agricultural marketing and domestic policy on the one handand teaching about the functioning of the inter-national trade and monetary system on the other.This meant that the profession was some-what slow in responding to the emerging tradeissues of the1960s.6By the1970s a host of new issues had arisenwhich emphasized the importance of external economic events.A sharp rise in oil prices, together with droughts in India,Africa,and the USSR,caused agricultural commodity marketsto spike upward.Two devaluations of the dollar5Schmitz and Helmberger(1970)then developed a modelin which they demonstrate that capital movements and producttrade can be complements,in that increased capital movementsbring about increased product trade.Their examples chosen werefor agriculture and natural resource industries and presaged thegrowth of agricultural and food trade linked to foreign direct investment that has continued to this day.6In an editorial introduction to the otherwise impressive col-lection of articles on agricultural economics published by theAmerican Economics Association(AEA)in1969,the editorsadmit that the“decision to emphasize a limited number of topicsresulted in the exclusion of a number of areas in which agricultural economists have specialized.Among the more importantfields thathave been excluded[is]...international trade”(AEA1969,p.xvi).D.Gale Johnson was on the selection committee for this volume,so presumably he found inadequate material in this area to include.at Rijksuniversiteit Groningen on April 26, Downloaded fromJosling et al.Understanding International Trade in Agricultural Products427and the virtual abandonment of the Bretton Woods monetary system added more shocks to markets.Increased macroeconomic instabil-ity and chaotic commodity market behavior showed up the dysfunctionality of domestic policies.D.Gale Johnson’s seminal bookWorld Agriculture in Disarray and his work on sugar markets encapsulated this situation(Johnson 1973,1974).G.Edward Schuh(1974)reminded the profession of the importance of macroeco-nomics to agricultural markets and the signif-icance of exchange rates to agricultural trade patterns.And,in an extensive survey of“tra-ditional”fields of agricultural economics from the1940s to the1970s(Martin1977),policies related to agricultural trade were deemed wor-thy of a full section,authored masterfully by D.Gale Johnson(Johnson1977).The1980s ushered in a remarkable period of conflicts over agricultural trade and of policy reform that sowed the seeds for their rec-onciliation.The reform of multilateral trade rules for agriculture had to await the neces-sary changes in domestic policy,but this reform eventually emerged from a mix of budget pressures and paradigm shifts.7The Interna-tional Agricultural Trade Research Consor-tium(IATRC,discussed in a later section) became a focus for work on trade.It was also a period when economists were becoming increasingly sophisticated in the art of building models of markets and estimating behavioral parameters.The international trade literature in general was changing over this period,with an examination of imperfect competition mod-els and of the importance of geography,the study of the political economy of protection, and the issue of regional integration.Agricul-tural economists became adept at translating and applying these new areas of exploration into the world of agricultural product trade and associated policies,as discussed below.The decade of the1990s saw a signifi-cant change in the international rules gov-erning national trade policies for agriculture makes.That set of changes made this an active decade for agricultural trade professionals. Despite the signing of the General Agree-ment on Tariffs and Trade(GATT)in1947 by the advanced industrial countries,and the progressive reduction of tariffs on imports of manufactures,there had been little progress on reducing agricultural trade barriers.The 7Policy dialogue in international bodies such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development contributed signifi-cantly to the paradigm shift,and this dialogue was an extension of the academic discussions of the time.changing paradigms of economic policy that started in the mid-1980s led eventually in1995to the full incorporation of agriculture intothe successor to the GATT,the World Trade Organization.8Multimarket and economy-wide models became still more sophisticated.This was an age of detailed empirical workon agricultural trade rather than one of con-ceptual improvements.But agricultural tradewas becoming mainstream in agricultural eco-nomics curricula,and domestic policy coursesin the United States and the EU began to include some“open economy”issues.Mean-while,agricultural trade itself was changingwith the globalization of the food industry, posing novel challenges for economists.It is clearly too early to judge the lasting nature of contributions since the beginning ofthe new millennium,but the expansion of the range of trade issues connected with environ-mental,consumer,animal welfare,water,and climate change issues has greatly broadenedthe focus of agricultural trade analysts.Recent concerns over the impact of price spikes onfood security and of the use of agriculturalcrops as biomass for fuel have kept agricul-tural trade issues high on the international agenda.Rapid growth in processed and high-value agricultural and food products,and a revolu-tionary spread of retail supermarkets accom-panied the“second wave”of globalization inthe modern era,so that it is no longer fancifulto talk of a global market for farm prod-ucts.Some economists focus on WTO issues, which have become a significant subfield of agricultural trade research and analysis.Oth-ers take a development view:Much empiricalwork on agricultural trade now is done by those examining developing-country issues,includ-ing questions such as the use of trade policyas an element in food security or antipoverty programs.Still others study regional or bilat-eral trade arrangements in all their glory, pondering the balance between the benefitsof partial liberalization and the costs of giv-ing preferred access to high-cost producers.Many contributions are now made by those working in(or with)multilateral institutions (such as the World Bank,the Organisationfor Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD],and the United Nations Confer-ence on Trade and Development[UNCTAD]),8However,trade negotiations have continued to pivot on thethorny issue of liberalization of farm product trade,as evidencedby the current problems in the WTO’s Doha Round.at Rijksuniversiteit Groningen on April 26, Downloaded from428April2010Amer.J.Agr.Econ.often in collaborative studies.This seems to reflect a shift in the way in which agricultural trade research has been organized,a topic to which we return at the end of the paper.As a way of highlighting the ways in which the profession has responded to these chang-ing events,we organize our subjective survey around six areas.Each area is an example of a cumulative advance in understanding,starting with one or two articles and books and devel-oping into a body of more or less accepted wisdom.Contribution#1:Understanding the behavior of international commodity pricesOne of the most persistent questions in agri-cultural trade is whether there are consistent long-run trends in international market prices for agricultural commodities.On the one hand, supply constraints(limited land area)in the face of demand growth(population and per capita income)could push farm product prices ever higher.On the other hand,as consumers spend a high share of rising incomes on non-food items(the Engel effect),economic growth will cause a shift in demand away from basic foods.Relatively rapid agricultural productiv-ity growth will lower the costs of farm produc-tion and hence tend to lower farm prices.The evidence for much of this century appeared to point to a declining price trend.9However,the significance of this trend became a matter of considerable controversy in the1960s.The variability of prices has also been a major topic for investigation over the years. High prices in the early1970s brought this issue to the fore,and a more recent price spike in 2007–8has renewed concerns about the corro-sive economic impact of market instability.Pri-mary product prices in international markets are notoriously more volatile than prices for other products.How much of the price volatil-ity is due to the characteristics of markets(e.g., supply shocks from weather or disease)and how much to government intervention became a subject for study in the1970s and1980s. Commodity Prices and the Terms of Trade The behavior of prices of agricultural com-modities on world markets has been an understandable obsession with economists.Of specific interest to agricultural trade analysis is 9This is in contrast to recent evidence for the period from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century(Williamson2008).the trend in the relative price of agricultural products compared with nonagricultural prod-ucts.The terms of trade for agricultural(andother primary)products have featured promi-nently in debates about the possible bias ofthe trade system toward particular groups of countries.The debate on whether the economic system generated outcomes that were stacked against developing countries was highly visiblein the1960s.Prebisch(1950)and Singer(1950)had come independently to the conclusion thatthere was a structural reason for the observed decline in the price of agriculture relativeto manufactured goods,reinforcing the ten-dency due to the different income elasticities. Imperfect markets in industrial goods allowed manufacturers to retain much of the benefitsfrom productivity increases rather than pass-ing them on to consumers,whereas agricultural productivity gains were passed directly to con-sumers(or at least processors)in the formof lower prices.As a consequence,the termsof trade turned progressively against the rural “periphery”in favor of the industrial“center.”The concept proved powerful in political termsand was a major motivation for the foundingof UNCTAD in1964and the calls for a New International Economic Order by developing countries in the1970s.The Prebisch/Singer hypothesis has donebetter as a political call to arms than as a statis-tical conclusion.A major revision of the datathat had originally been used was publishedby Grilli and Yang(1988),which broadly con-firmed a downward trend.10But other analysts disagreed with the interpretation of the data: Trends in prices over the past100years areby no means smooth.There have indeed beensharp declines in agricultural prices(particu-larly in1920)but also periods where the trendis upward(over thefirst part of the twenti-eth century),when it disappears(from1920until the late1970s),and when a strong down-ward trend begins(until1990)(Ocampo andParra2002).Cashin and Mc Dermott(2002, 2006)confirm these results and reject boththe existence of a long-run trend and the evidence of structural changes in the series used.The past decade has seen a recovery of prices,and many argue that the trend maybe upward for at least a few more years to come.Moreover,the link between terms oftrade and economic development has become10Their data have since been updated to2000by Pfaffenzeller, Newbolt,and Rayner(2007).at Rijksuniversiteit Groningen on April 26, Downloaded fromJosling et al.Understanding International Trade in Agricultural Products429more blurred.Identification of“primary prod-uct exporters”with“developing countries”looks increasingly dated:For many key farm commodities,high-income countries are the major exporters,and for many developing countries—especially in Asia—manufactured goods now dominate their exports.The recent revival of the idea that agricul-tural prices may be on a long-term upward trend owes much to three phenomena:rapid growth in emerging countries,particularly in China,India,and Brazil,with its implication for dietary improvements;the extraordinary increase in oil prices in2007,which raised energy costs in agriculture and led to gov-ernmental mandates and subsidies for biofu-els;and the apparent stagnation in technical advance in agriculture as a result of declin-ing research expenditures.Contributions to the understanding of these price movements have been somewhat contradictory.Somefind a sig-nificant role for speculation(Gilbert2008); others for biofuel policies(OECD and Food and Agriculture Organization[FAO]2008). But what seems generally agreed is that agri-cultural commodity prices now have a direct link with the price of petroleum,once it exceeds a threshold level at which biofuels become a privately profitable substitute for fossil fuels. International Price ShocksThe importance of commodity pricefluctua-tions and of the domestic policy responses to them was made apparent in the1970s.The quadrupling of petroleum prices in1973–74 and their doubling again in1979–80,when the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Coun-tries(OPEC)coordinated major reductions in supply,triggered a renewed focus on analyzing the consequences of such nonfarm shocks for the agricultural sector.Initially the focus of this literature was on analyzing the impact on con-sumers andfirms,as producers faced sharply higher energy costs.But the magnitude of the petroleum price stimulated massive and rapid exploration for and exploitation of new energy reserves.Such supply reactions were incorpo-rated in the analysis of price impacts,leading to what became known as the“Dutch Disease”literature that sought initially to explain the effects on other sectors of the Dutch economy following the discovery and exploitation of nat-ural gasfields off the coast of the Netherlands. Gregory(1975)made an early contribution to this literature on the impact of nonfarm sector booms:He found that the direct effect is a rise in the demand for labor in the booming nonfarm sector that will initially draw workersfrom other sectors to the booming sector butthat this is followed by an indirect impact on agriculture and other sectors as the change inreal income in the economy affects the demandfor all products.The same core theory has been used to ana-lyze the inter-and intrasectoral and tax policy impacts of agricultural commodity price boomsand busts.In the context of sub-SaharanAfrica,it was common practice for governments totax away windfalls from export price booms, either for depositing in a stabilization fund tobe drawn on to support farmers during periodsof price collapses or to boost treasury coffersso as to allow the boom to be shared withthe rest of the society,including nonboomingfarm industries.But recent analysis has castdoubt upon the ability of governments to effectsuch transfers.Trade economists have also been concernedwith the impact of storage policies on inter-national market price stability and on the optimal storage policy for an open economy.The early theoretical work on stabilization was stimulated by Hueth and Schmitz(1972),who showed the distributional effects in both a closed and an open economy from price stabi-lization brought about through storage.Feder, Just,and Schmitz(1977)analyzed storage poli-cies under trade uncertainty and showed cases where trade would be greatly reduced under ahigh degree of uncertainty.Just et al.(1978) analyzed the welfare implications of storagefrom an international perspective using non-linear assumptions,and Newberry and Stiglitz (1981)expanded the framework for optimal policy intervention under instability for open economies.The persuasive nature of their argu-ments,that private and public storage are code-termined and so the latter might just take theplace of the former,together with the return tolower prices in world markets,has effectively dropped the topic of intergovernmental stor-age agreements from the policy agenda sincethe1980s.11Domestic Policies and Market InstabilityThe argument that governments may exac-erbate international marketfluctuations bytheir own attempts to stabilize domestic prices11The topic did not totally disappear:Williams and Wright (1991),for instance,added additional insights into the welfareimpacts of commodity storage in both trade and no-trade situations.at Rijksuniversiteit Groningen on April 26, Downloaded from。

格特鲁特•凯塞比亚Gertrude Käsebier (1852–1934) was one of the most influential American photographers of theearly 20th century. She was known for her evocative images of motherhood, her powerful portraits of Native Americans and her promotion of photography as a career for women."Portrait of the Photographer" -manipulated self-portrait by Gertrude KäsebierPortrait of photographers Frances Benjamin Johnston and Gertrude Käsebier on the patio of a hotel in Venice, Italy, 1905●Miss N●(Portrait of Evelyn Nesbit), 1903●Clarence White Sr.,●1897-1910Blessed Art Thou among Women, ca.1899Auguste Rodin, 1905Chester Beach, 1910Portrait of George Luks (American painter), ca.1910●The Clarence White Family in Maine●(American photographer), 1913John Murray Anderson, ca.1914-1916Yoked and Muzzled Marriage, ca.1915On her twenty-second birthday, in 1874, she married twenty-eight year old Eduard Käsebier, a financially comfortable and socially well-placed businessman in Brooklyn.[1] The couple soon had three children, Frederick William (1875-?),Gertrude Elizabeth (1878-?) and Hermine Mathilde (1880-?). In 1884 they moved to a farm in New Durham, New Jersey, in order to provide a healthier place to raise their children.Käsebier later wrote that she was miserable throughout most of her marriage. She said, "If my husband has gone to Heaven, I want to go to Hell. He was terrible…Nothing was ever good enough for him.”[1] At that time divorce was considered scandalous, and the two remained married while living separate lives after 1880. This unhappy situation would later serve as an inspiration for one of her most strikingly titled photographs –two constrained oxen, entitled Yoked and Muzzled –Marriage (c1915).Rose O'Neill, ca.1907Portrait of Robert Henri (American painter), ca.1907Dorothy, ca.1900Indian Chief, ca.1901The Manger, ca.1899The Red Man, 1903弗里德里克•H•伊万斯Frederick H. Evans (June 26, 1853 –June 24, 1943) was a noted British photographer, primarily of architectural subjects.He is best known for his images of English and Frenchcathedrals. Evans began his career as a bookseller, but retired from that to become a full-time photographer in 1898, when he adopted the platinotype technique for his photography. Platinotype images, with extensive and subtle tonal range, non glossy-images, and better resistance to deterioration than other methods available at the time, suited Evans' subject matter. Almost as soon as he began, however, the cost of platinum -and consequently, the cost of platinum paper for his images -began to rise. Because of this cost, and because he was reluctant to adopt alternate methodologies, by 1915 Evans retired from photographyaltogether.Evans' ideal of straight-forward, "perfect" photographic rendering -unretouched or modified in any way -as an ideal was well-suited to the architectural foci of his work: the ancient, historic, ornate and often quite large cathedrals, cloisters and other buildings of the English and French countryside. This perfectionism, along with his tendency to exhibit and write about his work frequently, earned for him international respect and much imitation. He ultimately became regarded as perhaps the finest architectural photographer of his, or any, era -though some professionals privately felt that the Evans' philosophy favoring extremely literal images was restrictive of the creative expression rapidly becoming available within the growing technology of thephotographic field.Evans was also an able photographer of landscapes and portraits, and among the many notable friends and acquaintances he photographed was George Bernard Shaw, with whom he also often corresponded.The movable hut in the garden of Shaw's Corner, where Shaw wrote most of his works after 1906, including Pygmalion.安妮•布里克曼Anne Wardrope (Nott) Brigman (1869–1950) was an American photographer and one of the original members of the Photo-Secession movement in America. Her most famous images were taken between 1900 and 1920, and depict nude women in primordial,naturalistic contexts.Self-portrait of Anne Brigman published in The San Francisco Call in 1908."Soul of the Blasted Pine," a self-portrait of AnneBrigman taken in 1908.爱丽丝•伯顿Alice Boughton (1866 or 1867-1943) was an early 20th century American photographer known for her photographs of many literary and theatrical figures of her time. She was a Fellow of Alfred Stieglitz's Photo-Secession, a circle of highlycreative and influential photographers whose artistic efforts succeeded in raising photography toa fine art form."Dawn", by Alice Boughton. Photogravure published in Camera Work, No 26, 1909阿尔文•兰顿•柯本Alvin Langdon Coburn (June 11, 1882 –November 23, 1966) was an early 20th century photographer who became a key figure in the development of American pictorialism. He became the first major photographer to emphasize the visual potential of elevated viewpoints and latermade some of the first completely abstractphotographs.Coburn in 1922, Self-portrait"Spider-webs", by Alvin Langdon Coburn. Photogravure published in Camera Work, No 21,1908"Bernard Shaw", by Alvin Langdon Coburn. Photogravure published in Camera Work, No 21,1908"Rodin", by Alvin Langdon Coburn. Photogravure published in Camera Work, No 21, 1908Blue plaque on his home in Harlech, North WalesIn 1890 the family visited his maternal uncles in Los Angeles, and they gave him a 4 x 5 Kodak camera. He immediately fell in love with the camera, and within a few years he had developed a remarkable talent for both visual composition and technical proficiency in the darkroom. When he was sixteen years old, in 1898, he met hiscousin F. Holland Day, who was already aninternationally known photographer with considerable influence. Day recognized Coburn’s talent and both mentored him and encouraged him to take up photography as a career.At the end of 1899 his mother and he moved to London, where they met up with Day. Day had been invited by the Royal Photographic Society to select prints from the best American photographers for an exhibition in London. He brought more than a hundred photographs with him, including nine by Coburn –who at this time was only 17 years old. With the help of his cousin Coburn’s career took a giant first step.弗莱德•荷兰德•迪Fred Holland Day (Boston July 8, 1864 -November 12, 1933) was an American photographer and publisher. He was the first in the U.S.A. to advocate that photography should be considered a fine art.Day was the son of a Boston merchant, and was a man of independent means for all his life. He first trained as a painter.Day's life and works had long been controversial, since his photographic subjects were often nude male youthsYouth Sitting on a Stone, by F. Holland Day (1907)Portrait of Edward Carpenter, the early gay rights activist, by F. Holland Day卡尔•斯特劳斯Karl Struss, A.S.C. (November 30, 1886 —December 15, 1981) was a photographer and a cinematographer of the 1920s through the 1950s. He was also one of the earliest pioneers of 3-D films. While he mostly worked on films, he was also one of the cinematographers for thetelevision series Broken Arrow.。

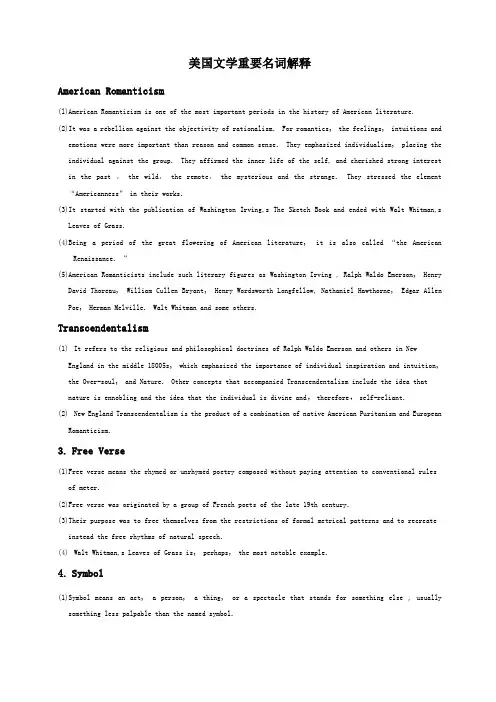

美国文学重要名词解释American Romanticism(l)American Romanticism is one of the most important periods in the history of American literature. (2)It was a rebellion against the objectivity of rationalism. For romantics, the feelings, intuitions andemotions were more important than reason and common sense. They emphasized individualism, placing the individual against the group. They affirmed the inner life of the self, and cherished strong interest in the past ,the wild,the remote,the mysterious and the strange. They stressed the element “Americanness” in their works.(3)It started with the publication of Washington Irving,s The Sketch Book and ended with Walt Whitman,sLeaves of Grass.(4)Being a period of the great flowering of American literature, it is also called “the AmericanRenaissance. ”(5)American Romanticists include such literary figures as Washington Irving , Ralph Waldo Emerson, HenryDavid Thoreau, William Cullen Bryant, Henry Wordsworth Longfellow, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Edgar Allen Poe, Herman Melville. Walt Whitman and some others.Transcendentalism(1)It refers to the religious and philosophical doctrines of Ralph Waldo Emerson and others in NewEngland in the middle 18005s, which emphasized the importance of individual inspiration and intuition, the Over-soul, and Nature. Other concepts that accompanied Transcendentalism include the idea that nature is ennobling and the idea that the individual is divine and,therefore,self-reliant.(2)New England Transcendentalism is the product of a combination of native American Puritanism and EuropeanRomanticism.3.Free Verse(1)Free verse means the rhymed or unrhymed poetry composed without paying attention to conventional rulesof meter.(2)Free verse was originated by a group of French poets of the late 19th century.(3)Their purpose was to free themselves from the restrictions of formal metrical patterns and to recreateinstead the free rhythms of natural speech.(4)Walt Whitman,s Leaves of Grass is, perhaps, the most notable example.4.Symbol(1)Symbol means an act, a person, a thing, or a spectacle that stands for something else , usuallysomething less palpable than the named symbol.(2)The relationship between the symbol and its referent is not often one of simple equivalence. Allegoricalsymbols usually express a neater equivalence with what they stand for than the symbols found in modern realistic fiction.5.Theme(1)Theme means the unifying point or general idea Of a literary work.(2)It provides an answer to such question as “What is the work about?”(3)Each literary work carries its own theme or themes. For example, King Lear has many themes, amongwhich are blindness and madness6.American Naturalism(1)The American naturalists accepted the more negative interpretation of Darwin's evolutionary theory andused it to account for the behavior of those characters in literary works who were regarded as more or less complex combinations of inherited attributes, their habits conditioned by social and economic forces.(2)American Naturalism is evolved from realism when the author,s ton e in writing becomes less serious andless sympathetic but more ironic and more pessimistic. It is no more than a gloomy philosophical approach to reality, or to human existence.(3)Dreiser is a leading figure of his school.7.Darwinism(1)Darwinism is a term that comes from Charles Darwin,s evolutionary theory.(2)Darwinists think that those who survive in the world are the fittest and those who fail to adaptthemselves to the environment will perish.They believe that man has evolved from lower forms of life.Humans are special not because God created them in His image, but because they have successfully adapted to changing environmental conditions and have passed on their survival.making characteristics genetically.(3)Influenced by this theory, some American naturalist writers apply Darwinism as an explanation of humannature and social reality.8.Local Colorists(1)Generally speaking, the writings of local colorists are concerned with the life of a small, well-defined region or province. The characteristic setting is the isolated small town.(2)Local colorists were consciously nostalgic historians of a vanishing way of life, recorders of a presentthat faded before their eyes. Yet for all their sentimentality, they dedicated themselves to minutely accurate descriptions of the life of their regions. They worked from personal experience to record the facts of a local environment and suggested that the native life was shaped by the curious conditions of the Locale.(3)Major local colorists include Hamlin Garland, Mark Twain, Kate Chopin, etc.9.The Lost Generation(1)The Lost Generation is a term first used by Gertrude Stein to describe the post-World War Igeneration of American writers :men and women haunted by a sense of betrayal and emptiness brought about by the destructiveness of the war.(2)Full of youthful idealism, these individuals sought the meaning of life, drank excessively, had loveaffairs and created some of the finest American literature to date.(3)The three best ——known representatives of Lost Generation are F Scott Fitzgerald . Ernest Hemingwayand John Dos Passos.(4)Others usually included among the list are Sherwood Anderson, Kay Boyle, Hart Crane, Ford MaddoxFord and Zelda Fitzgerald.10.Imagism(1)Imagism came into being in Britain and U. S. around 1910 as a reaction to the traditional Englishpoetry to express the sense of fragmentation and dislocation.(2)The imagists.with Ezra Pound leading the way, hold that the most effective means to express thesemomentary impressions is through the use of one dominant image.(3)Imagism is characterized by the following three poetic principles :i1 direct treatment of subjectmatter;ii)economy of expression;iii)as regards rhythm, to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase, not in the sequence of metronome.(4)Ezra Pound's In a Station of the Metro is a well-known imagist poem.11.The Beat Generation(1)The members of the Beat Generation were new bohemian libertines, who engaged in aspontaneous,sometimes messy, creativity.(2)The beat writers produced a body of written work controversial both for its advocacy of non—conformityand for its non——conforming style.(3)The major beat writings are Jack Kerouac,s On the Road and AIlen Ginsberg,s Howl. Howl became themanifesto of the Beat Generation.12.American Dream(1)American Dream refers to the dream of material success, in which one, regard1ess of socialstatus,acquires wealth and gains success by working hard and good luck.(2)In literature, the theme of American Dream recurs . In The Great Gatsby. Gatsby comes from the west to the east with the dream of material success. By bootlegging and other illegal means he fulfilled his dream but ended up being killed. The novel tells the shattering of American Dream rather than its Success.13.Expressionism(1)Expressionism refers to a movement in Germany early in the 20th century, in which a number of painters sought to avoid the representation of external reality and , instead, to project a highly personal or subjective vision of the world.(2)Expressionism is a reaction against realism or naturalism , aiming at presenting a post 一war world violently distorted. (3)Works noted for expressionism include:Eugene O' Neill's The Emperor Jones,James Joyce’s Ulysses and Finnegan,s Wake, and T S . Eliot,s The Waste Land, etc.. (4)In a further sense, the term is sometimes applied to the belief that literary works are essentially expressions of their authors, moods and thoughts;this has been the dominant assumption about literature since the rise of Romanticism14.Feminism(1)Feminism incorporates both a doctrine of equal rights for women and an ideology of social transformation aiming to create a world for women beyond simple social equality.(2)In general, feminism is the ideology of women,s liberation based on the belief that women suffer injustice because of their sex . Under this broad umbrella various feminisms offer differing analyses of the causes,or agents,of female oppression.(3)Definitions of feminism by feminists tend to be shaped by their training, ideology or race. So, for example, Marxist and Socialist feminists stress the interaction within feminism of class with gender and focus on social distinctions between men and women.Black feminists argue much more for an integrated analysis which can unlock the multiple systems of oppression.15.Hemingway Code Hero(1)Hemingway Hero, also called code hero, is one who, wounded but strong, more sensitive, enjoys the pleasures of life (sex, alcohol, sport) in face of ruin and death, and maintains, through some notion of a code, an ideal of himself.(2)Barnes in The Sun Also Rises, Henry in A Farewell to Arms and Santiago in The Old Man and the Sea aretypical of Hemingway Hero.16.Harlem Renaissance(1)Harlem Renaissance refers to a period of outstanding literary vigor and creativity thatoccurred in the United States during the 1920s.(2)The, Harlem Renaissance changed the images of literature created by many black and white American writers .New black images were no longer obedient and docile , instead they showed a new confidence and racial pride.(3)The center of this movement was the vast black ghetto of Harlem, in New York City. (4)The leadingfigures are Langston Hughes, James Weldon Johnson, Wallace Thurman, etc..17.Impressionism(1)Impressionism is a style of painting that gives the impression made by the subject on the artist without much attention to details.Writers accepted the same conviction that the personal attitudes and moods of the writer were legitimate elements in depicting character or setting or action.(2)Briefly, it is a style of literature characterized by the creation of general impressions and moods rather than realistic moods.18.Puritanism(1)Puritanism refers to the practices and beliefs of the Puritans. The Puritans are the people who wantedto purify the Church of England and was persecuted in England. The first settlers who became the founding father of the American nation were quite a few of them Puritans. They came to America out of various reasons, but because they were a group of serious and religious people, they carried a code of values, a philosophy of life, a point of view which, in time took root in the New World, and became what is popularly known as American Puritanism.(2)The American Puritans, like their brothers back in England, were idealists, believing that the Churchshould be restored to “purity” of the first century Church. To them religion was a matter of primary importance. They accepted the doctrine of predestination, original sin and total depravity, and limited atonement through a special infusion of grace from God. It was this kind of religious belief that they brought with them into the wilderness. There they meant to prove that they were God ’s chosen people enjoying His blessings on this earth as in heaven.(3)In the grim struggle for survival that followed immediately after their arrival in America, thecharacter of the people underwent a significant change. They became more practical, as indeed they had to be. Gradually a set of Puritan values came into being. They believe in hard working, piety, and sobriety.(4)In a word, American Puritanism was one of the most enduring shaping influences in American thoughtand American literature. It has become, to some extent, a state of mind,rather than a set of tenets, so much a part of the national cultural atmosphere that the American breathes.We can say that, without some understanding of Puritanism, there can be no real understanding of America and its literature.19.Gothic RomanceIt refers to the Romantic novels with the settings of the ancient castles or old houses and descriptions of supernatural elements like ghosts and specters, usually horror-provoking, like Poe's "The Fall of the House of Usher” and some of Irving,s tales.20.Psychological RealismIt is the realistic writing that probes deeply into the complexities of characters , thoughts and motivations. Henry James, novel The Ambassadorsis considered to be a masterpiece of psychological realism.And Henry James is considered the founder of psychological realism. He believed that reality lies in the impressions made by life on the spectator, and not in any facts of which the spectator is unaware. Such realism is therefore merely the obligation that the artist assumes to represent life as he sees it, which may not be the same life as it “really” is.21.Waste Land Painters“Waste Land Painters” refers to such writers as F. Scott Fitzgerald, T.S. Eliot, Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner. With their writings, all of them painted the postwar Western world as a waste land, lifeless and hopeless. Eliot,s The Waste Land paints a picture of modern social crisis. In this poem, modern civilized society turns into a waste deathly land due to ethical degradation and disillusionment with dreams. His aThe Hollow Men” exhibited a pessimism no less depressing than The Wa ste Land.Fitzgerald,s The Great Gatsby wrote about the frustration and despair resulting from the failure of the American dream. Hemingway,s works, such as The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, portrayed the dilemma of modern man utterly thrown upon himself for survival in an indifferent world, revealing man's impotence and his despairing courage to assert himself against overwhelming odds. Faulkner made the history of the Deep South the subject of the bulk of his work, and created a symbolic picture of the remote past. His fictional Yoknapatwpha represents a microcosm of the whole macrocosmic nature of human experience.22.ConflictThe conflict in a work of fiction is the battle that the main character must wage against an opposing force. Usually the events of the story are all related to the conflict, and theconflict is resolved in some way by the story,s end.A battle with nature is a common conflict in literature, particularly Naturalist literature. Othercommon types are conflict between two characters; conflict between a character and the laws of society;conflict between a character and chance or fate; the inner conflict, in which a character struggles with personal weakness, illusions, or desires.23.StyleBroadly speaking, style is the way a literary work is created of a writer writes his literary works.In a narrow sense it refers to the typical linguistic feature and specific literary techniques and devices for a literary work or a writer.24.Point of viewThe angle from which a story or a novel is written is the point of view. Generally speaking, fiction is written in the omniscient point of view, the third person point of view or the first-person point of view.25.Black HumorOriginally it refers to a type of course humor in which tragic events like death and serious wounds are made fun of. In American literature it refers to the novels which employ this type of humor.26.The Jazz AgeTo many, World War I was a tragic failure of old values, of old politics, of old ideas. The social mood was often one of confusion and despair. Yet, on the surface the mood in American during the 1920s did not seem desperate. Instead, Americans entered a decade of prosperity and exhibitionism that prohibition, the legal ban against alcoholic beverages, ded more to encourage than to curb. Fashions were extravagant; More and more automobiles crowded the roads, advertising flourished; and nearly every American home had a radio in it. Fads swept the nation. People danced the Charleston, and they sat upon the flagpoles. This was t he Jazz Age, when New Orleans musicians moved “up the river” to Chicago and the theater of New York,s Harlem pulsed with the music that had become a symbol of the times. These were the Roaring Twenties. The roaring of the decade served to mask a quiet pain, the sense of loss that Gertrude Stein had observed in Paris. F. Scott Fitzgerald portrays the Jazz Age as a generation of “the beautiful and damned”, drowning in their pleasures.。