The-theory-and-practice-of-translation-奈达的翻译理论与实践

- 格式:doc

- 大小:36.50 KB

- 文档页数:6

尤金。

奈达的翻译理论、影响及其评析在中国,奈达的翻译理论在当代西方翻译理论中介绍的最早、最多,影响也最大。

尤金。

A。

奈达(Eugene A.Nida,1914---),美国人,早年师丛著名的教授弗里斯(Charles C.Fries)和布龙菲尔德(Leonard Bloomfield),并与1943年获语言学博士学位。

毕业后供职与美国圣经协会,终生从事圣经翻译和翻译理论的研究,著作等身,是公认的当代翻译理论的主要奠基人。

他的理论核心思想是功能对等(functional equivalence).这个名称的前身是动态对等(dynamic equivalence).后来为避免误解,改为功能对等。

先分析一下为什么要把动态对等改为功能对等呢?奈达对动态对等下了如是的定义:“所谓翻译,是在译语中用最切近而又最自然的对等语再现原语的信息,首先是意义,其次是文体。

”(Nida &Taber,1969)在这一定义中,“切近是指切近原语信息”;“自然”是指译语中的表达方式;“对等”把上述两者结合起来,是对等语(equivalent),而不是同一语(identity).在某种意义上来说,强调的是信息对等,而不是形式对应(formal correspondence)。

由这一定义可见,奈达突出了翻译中“内容为主,形式为次”的思想。

奈达的这一思想,引起了不少误解。

认为翻译只翻译内容,不必要顾及语言的表达形式,因此,各种各样的自由译都被冠以“动态对等”。

所以奈达后来在《从一种语言到另一种语言:论圣经翻译中的功能对等》(From one language to another:Functional equivalence in Bible Translation)一书中,把“动态对等”的名称改为“功能对等”。

对于功能对等,奈达又作出了很多的补充,首先对“信息”作了进一步的界定,声明信息不仅包括思想内容,而且也包括语言形式。

翻译理论尤金·奈达的“动态对等”(Dynamic Equivalence)/“功能对等”(Functional Equivalence)尤金·A·奈达(Eugene A。

Nida)(1914—2011),美国著名的语言学家,翻译家,翻译理论家。

1943年获密歇根大学语言学博士学位,长期在美国圣经学会主持翻译部的工作,曾任美国语言学会主席,1980年退休后任顾问。

奈达是一位杰出的语言学家,他到过96个国家,在一百多所大学做过讲座,来中国有13次之多,直至2003年,奈达89岁高龄时,仍到非洲讲学。

(Toward a Science of Translating),尤金最有影响的著作是1964出版的《翻译的科学探索》其次要数《翻译理论与实践》(The Theory and Practice of Translation),系与查尔斯·泰伯合著(1969)。

奈达理论的核心概念是“功能对等”。

所谓“功能对等”,就是说翻译时不求文字表面的死板对应,而要在两种语言间达成功能上的对等。

为使源语和目的语的之间的转换有一个标准,减少差异,尤金·A·奈达从语言学的角度出发,根据翻译的本质,提出了著名的“动态对等”翻译理论,即“功能对等”。

在这一理论中,他指出,“翻译是用最恰当、自然和对等的语言从语义到文体再现源语的信息”(郭建中,2000 , P65).奈达有关翻译的定义指明,翻译不仅是词汇意义上的对等,还包括语义、风格和文体的对等,翻译传达的信息既有表层词汇信息,也有深层的文化信息。

“动态对等”中的对等包括四个方面:1. 词汇对等;2。

句法对等;3。

篇章对等;4.文体对等.在这四个方面中,奈达认为,“意义是最重要的,形式其次”(郭建中,2000 , P67)。

形式很可能掩藏源语的文化意义,并阻碍文化交流。

因此,在文学翻译中,根据奈达的理论,译者应以动态对等的四个方面,作为翻译的原则,准确地在目的语中再现源语的文化内涵.为了准确地再现源语文化和消除文化差异,译者可以遵循以下的三个步骤。

翻译理论练习题西方译论简介西塞罗:“我不是作为解释员而是作为演说家进行翻译的,不是字当句对,而是保留语言的总的风格和力量。

”泰特勒的“翻译三原则”: 1) 译文应完全传达原作的思想; 2)译文的风格与笔调应与原作属于同一性质;3)译文应具有原作的流畅性。

费道罗夫的等值翻译思想: 1)与原文作用相符(表达方面的等值); 2) 译者所选用的语言材料的等值(语言和文体的等值)奈达的翻译思想:所谓翻译,是指用一种语言中的语言符号解释另一种语言中的语言符号;是指从语义和文体风格上采用最接近而又最自然的同义语再现原文的信息。

他主张把翻译的重点放在译文读者的反应上。

他认为判断译作是否翻译得正确,必须以译文的服务对象为衡量标准。

“衡量翻译质量的标准,不仅仅在于所译的词语能否被理解,句子是否合乎语法规范,而在于整个译文使读者产生什么样的反应。

”英国翻译理论家:纽马克(Peter Newmark)他提出真正的翻译应该充分体现作者的意图。

译者应忠实于原文读者和译文,并根据原文所使用的语言种类来确定原文读者群的特点,从而确定给予目的语读者多少注意力。

西方翻译理译理论练习题1. It is _______ that wrote Essay on the Principles of Translation in 1790.A. F. TylerB. Charles R. TaberC. Saint JeromeD. Eugene A. Nida2. According to The Art of Translation by Theodore Savory, faced with a passage in its original language, a translator must ask himself some questions except: A. What does the author say? B. What does he mean? C. How does he say it? D. Why does he say it? 3. The Art of Translation is written by _______. A. Theodore Savory B. George Steiner C. Eugene A. Nida D. Charles R. Taber4. Several thousand years ago, _______ did not think it necessary to translate word for word, and he preserved the general style and force of the language. A. Cicero B. Saint Jerome C. John SteinbeckD. Theodore Savory5. All of the following ideas are Cicero’s, except ________. A.It wasn’t necessary to translate word for word.B.He preserved the general style and force of the language.C.It wasn’t his duty to count out words to the re ader like coins, but rather ti pay them out by weight as it were.D.He aimed at translating sense, not words.6. A. F. Tytler thought the principles of translation included all the following except _______. A. the translation should give a complete transcript of the ideas of the original work. B. It is necessary to translate word for word. C. The style and manner of writing should be of the same character with that of the original. D. The translation should have all the ease of original composition.7. “______” is the idea of Saint Jerome. A.It isn’t necessary to translate word for word. B.I have always aimed at translating sense, not words. C.The translation should have all the ease of original composition. D.The style and manner of writing should be of the same character with that of the original.8. ________ is correct. A.Saint Jerome said that he had always aimed at translating sense, not words. B.Saint Jerome said that it was necessary to translate word for word. C.Saint Jerome said that it wasn’t his duty to count out words to the reader like coins, but rather to pay them out by weight as it were. D.ASaint Jerome said that he preserved the general style and force of the language when he was translating.9. ________ describes a good translation to be, that, in which the merit of the original work is so completely transfused into another language, as to be as distinctly apprehended, and as strongly felt, by a native of the country to which that language belongs, as it is by those who speak the language of the original work. A. Cicero B. Saint Jerome C. A. F. Tylter D. Charles R. Taber 10. 句法上下文是指——————。

对The Theory and Practice of Translation书中翻译理论的理解概括尤金・奈达是美国当代著名的语言学家、翻译家,也是西方语言学派翻译理论的主要代表之一,他发展了英国著名翻译理论家纽马克提出的交际翻译理论。

交际法的翻译理论不仅照顾到语言意义的传递,也考虑到功能的对应,解决了原来的翻译理论从语言本身解决不了的问题。

上世纪80年代初,奈达的翻译理论传到中国并备受推崇。

奈达的翻译理论使我国大多数翻译工作者开始接触西方系统的翻译理论,对中国的翻译理论研究影响非常大,以致在当时中国的翻译界形成了言必称奈达的局面。

80年代末90年代初,对奈达的翻译理论的质颖之声开始出现,90年代中期以后,进而出现了“言必称奈达理论之缺陷”的风潮,大有对其全盘否定之势。

近几年,译界开始了对奈达的翻译理论的冷静反思。

在中国翻译界舆有巨大影响力的翻译理论除了严复的“信、达、雅”外,想必就是奈达的理论r。

自从它传人中图以来,沉寂多年的巾国译坛开始活跃起来,中国的翻译王作者感受羁了一黢算竣翡蘩译瑾沦豹春弧,菝享孛免之一振。

眼界也开阕了,此后的翻泽理沦与实践便出现了畜必称奈达的现象,可见奈达理论的影响之大:奈达的理论属于科学的翻译理论体系,它之所以会在世界范同内有如此大的影响就在于它的科学性。

奈选的翻译思想体现在{也不同时期的薯住巾,两最能充分体现缝主要,也是较袋熬豹秘译愚怒的怒《赣泽瑾论与实践》一书。

该书获潺裔学的角度对麟译的过程进行了全丽、系统的分析,为翻译实践提供了理沦指导。

全书共分为八章,前两章主要从火体上概述了翻译中常见的同题,剩下的章节具体论述了翻译的过程,即分援、转换、重组、检测。

筹一章楚要套缨了一些关于翻译豹耨观点,如酾译的羹点放语言形式转囱读者反应,这楚奈达翻泽思想的核心内容。

此外.他还认为语言是有共住的.尽管各种语言都有各自的特点,一种语言能表达的枣情也能用另一种讲辫表达。

他在第二章提出了动态对镲的观点,认为翻译怒在译语中爆最切邀丽又最自然的对等渗霉臻源语的傣患,善壳是意义。

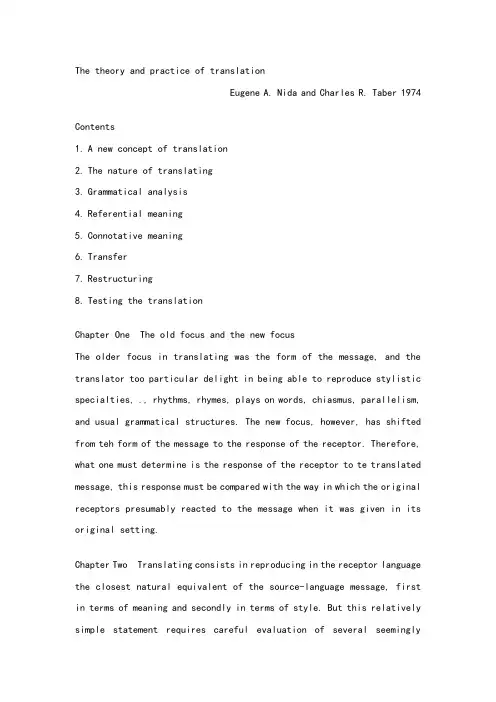

The theory and practice of translationEugene A. Nida and Charles R. Taber 1974Contents1.A new concept of translation2.The nature of translating3.Grammatical analysis4.Referential meaning5.Connotative meaning6.Transfer7.Restructuring8.Testing the translationChapter One The old focus and the new focusThe older focus in translating was the form of the message, and the translator too particular delight in being able to reproduce stylistic specialties, ., rhythms, rhymes, plays on words, chiasmus, parallelism, and usual grammatical structures. The new focus, however, has shifted from teh form of the message to the response of the receptor. Therefore, what one must determine is the response of the receptor to te translated message, this response must be compared with the way in which the original receptors presumably reacted to the message when it was given in its original setting.Chapter Two Translating consists in reproducing in the receptor language the closest natural equivalent of the source-language message, first in terms of meaning and secondly in terms of style. But this relatively simple statement requires careful evaluation of several seeminglycontradictory elements.Reproducing the messageTranslating must aim primarily at “reproducing the message.” To do anything else is essentially false to one’s task as a translator. But to reproduce the message one must make a good many grammatical and lexical adjustments.Equivalence rather than identityThe translator must strive for the equivalence rather than identity. In a sense, this is just another way of emphasizing the reproduction of the message rather than the conversation of the form of the utterance, but it reinforces the need for radical alteration of a phrase, which may be quiet meaningless.A natural equivalentThe best translation does not sound like a translation. In other words, a good translation of the Bible must not be “cultural translation”. Rather, it is a “linguistic translation”. That is to say, it should studiously avoid “translationese”--formal fidelity, with resulting unfaithfulness to the content and the impact of the message.The priority of meaningAs has already been indicted in the definition of translating, meaning must be given priority, for it os the content of the message which is of prime importance for Bible translating.The significance of styleThough style is secondary to content, it is nevertheless important, one should not translate poetry as though it were prose, nor expository material as though it were straight narrative.In trying to reproduce the style of the original one must beware, however, of producing something which is not functionally equivalent.A system of prioritiesAs a a basis for judging what should be done in specific instances of translating, it is essential to establish certain fundamental sets of priorities: (1) contextual consistency has priority over verbal consistency ( or word-for-word concordance), (2) dynamic equivalence has priority over formal correspondence, (3) the aural form of language has priority over the written form, (4) forms that are used by and acceptable to the audience for which a translation is intended have priority over forms that may be traditionally more perspectives.The priority of dynamic equivalence over formal correspondenceIf we look at the translations in terms of the receptors, rather than in terms of their respective forms, then we introduce another point of view; the intelligibility of the translation. Such intelligibility is not, however, to be measured merely in terms of whether the words are understandable, and the sentences grammatically constructed, but in terms of the total impact, the message has on the one who receives it.Dynamic equivalence is therefore to be defined in terms of the degree to which the receptors of the message in the receptor language respond to it in substantially the same manner as the receptor in the sourcelanguage. This response can never be identical, fro the culture and historical settings are too different, but there should be a high degree of equivalence of response, or the translation will have failed to accomplish its purpose.It would be wrong to think, however, that the response of the receptors in the second language is merely in terms of comprehension of the information, for communication is not merely informative. It must also be expressive and imperative if it is to serve the principal purposes of communications.Of course, persons may insist that by its very nature a dynamic equivalent translation is a less “accurate” translation, for it departs further from the forms of the original. To argue in this manner, however, is to use “accurate”in a formal sense, whereas accuracy can only be rightly determined by judging the extent to which the response of the receptor is substantially equivalent to the respond of the original receptors. In other words, does the dynamic equivalent translation succeed more completely in evoking in the receptors responses which are substantially equivalent to those experienced by the original receptors If “accuracy”is to be judged in this light, then certainly the dynamic equivalent translation is not only moe meaningful to the receptors but also more accurate. This assumes, of course, that both the formal correspondence translation and the dynamic equivalent translation do not contain any overt errors of exegesis.Grammatical analysisThere are three major steps in analysis: (1) determining the mining themeaningful relationships between the words and combinations of words, (2) the referential meaning of the words and special combinations of words, idioms, (3) the connotative meaning.Kernel sentencesWe soon discover that we have simply recast the expressions so that events are expressed as verbs, objects as nouns, abstracts (quantities and qualities) as adjectives or adverbs. The only other terms are relationals, ., the prepositions and conjunctions.These restructures expressions are basically what many linguistics call “kernels”; that is to say, they are the basic structural elements out of which the language builds its elaborate surface structures. In fact, one of the most important insights coming from “transformational grammar” is the fact that in all languages there are half a dozen to a dozen basic structures out of which all the more elaborate formations are constructed by means of so called “transformations”. In contrast, back transformation, then, is the analytic process of reducing the surface structure to its underlying kernels.Semantic adjustments made in transferIn transferring the message from one language to another, it is the content which must be preserved at any cost; the form, except in special cases, such as poetry, is largely secondary, since within each language, the rules for relating content to form are highly complex, arbitrary, and variable.Of course, if by coincidence it is possible to convey the same contentin the receptor language in a form which closely resembles that of the source, so much the better; we preserve the form when we can, but more than the form has to be transformed precisely in order to preserve the content. An expressive effort to preserve the form inevitably results in a serious loss or distortion of the message.Obviously in any translation there will be a type of “loss”of semantic content, but the process should be so designed as to keep this to a minimum. The commonest problems of the content transfer arise in the following areas: (1) idioms, (2) figurative meanings, (3) shifts in central components of meaning, (4) generic and specific meanings, (5) pleonastic expressions, (6) special formulas, (7) redistribution of semantic components, (8) provision for contextual conditioning.(8)In other instances one may find it important to employ a descriptive phrase so as to provide some basis for comprehending the significance of the original.It must be further emphasized that one is not free to make in the text any and all kinds of explanatory additions and/or expansions.Testing the translationOnce the process of restructuring has been completed, the next essential step is th e testing of the translation. This should cover the entire range of possible problems: accuracy of rendering, intelligibility, stylistic equivalence, etc. But to do this, one must focus attention not upon the extent of verbal correspondence but upon the amount of dynamic equivalence. This does not mean, of course, that the translation isjudged merely on the extent to which people like the contents. Some people may object strongly to the themes and the concepts which are communicated, but there should not be anything in the translation itself which is stylistically awkward, structurally burdensome, linguistically unnatural, and semantically misleading or incomprehensible, unless, of course, the message in the source language has these characteristics ( the task of the translator is to produce the closest natural equivalent, not to edit or to rewrite). But to judge these qualities one must look to the potential users.The problem of overall lengthIt only means that in the process of transfer from one linguistic and cultural structure to another, it is almost inevitable that the resulting translation will turn out to be longer.This tendency to greater length is due essentially to the fact that one wishes to state everything that is in the original communication but is also obliged to amke explicit in the receptor language what could very well remain implicit in the source language text, since te original receivers of this communication presumably had all the necessary background to understand the contents of the message.He analyzes its components builds in proper redundancy by making explicit what is implicit in the original, and then produces something the readers in the receptor language will be able to understand.Types of expansionsThe expansions may perhaps be most conveniently divided between syntactic(or formal) expansions and lexical (or semantic) ones.Lexical expansions in marginal helpsIn making explicit what is fully implicit in the original translation, one can ofter insert material in the text itself without imposing undue strains upon the process of translation.Such information may only be part of the general cultural background shared by the participants in the source language. This type of information cannot be legitimately introduced into the text of a translation, but should be placed in marginal helps, either in the form of glossaries, where information about recurring terms is gathered together in summary fashion, or in marginal notes on the page where the difficulty in understanding occurs.Practical textsTherefore, if a translator really wants to obtain satisfactory replies to direct questions on specific problems, the only way to do so is by supplying people with alternatives. This means that one must read a sentence in two or more ways, ofter repeating such alternatives slowly (and , of course, in context). And then ask such questions as: “which way sounds the sweetest”“which is planner”...Explaining the contentsA secondary very important way of testing a translation is to have someone read a passage to someone else and then to get this individual to explain the contents to other persons, who did not hear the reading.Reading the text aloudPublication of sample materialThe ultimate basis for judging a translation。

Literature review----The history and development of functional equivalenceThose who insist functional equivalence define that translation is a unique way of human being's activity with specific intentions,which is language service item for customers 、readers 、function and aims of the text in society circumstance。

Baker tell us that the process of translation should not been limited by original text and it’s influence to the translated or even the certain function which author use in the text。

Meanwhile,he got the result that translation is certainly depend on the needs that readers and users aims to translate text eventually。

Eugene A。

Nada,a famous America translator,got the functional Equivalence in his book ofLanguage and Culture: Translation Context in 2001。

First of all,a minimal, realistic definition of functional equivalence:The readers of a translated text should be able to comprehend it to the point that they can conceive of how the original readers of the text must have understood and appreciated it. Secondly,idealistic of functional equivalence: The readers of a translated text should be able to understand and appreciate it in essentially the same manner as the original readers did。

A Tale of the Fountain of the Peach Blossom SpringIn the year of T aiyuan(1) of the Jin Dynasty, there lived a man in Wuling(2) jun who earned his living by fishing. One day, he rowed his boat along a stream, unaware of how far he had gone when all of a sudden, he found himself in the midst of a wood full of peach blossoms. The wood extended several hundred footsteps along both banks of the stream. There were no trees of other kinds. The lush grass was fresh and beautiful and peach petals fell in riotous profusion. The fisherman was so curious that he rowed on, in hopes of discovering where the trees ended.At the end of the wood was the fountainhead of the stream. The fisherman beheld a hill, with a small opening from which issued a glimmer of light. He stepped ashore to explore the crevice. His first steps took him into a passage that accommodated only the width of one person. After he progressed about scores of paces, it suddenly widened into an open field. The land was flat and spacious. There were houses arranged in good order with fertile fields, beautiful ponds, bamboo groves, mulberry trees and paths crisscrossing the fields in all directions. The crowing of cocks and the barking of dogs were within everyone's earshot. In the fields the villagers were busy with farm work. Men and women were dressed like people outside. They all, old and young, appeared happy.They were surprised at seeing the fisherman, who, being asked where he came from, answered their every question. Then they invited him to visit their homes, killed chickens, and served wine to entertain him. As the words of his arrival spread, the entire village turned out to greet him. They told him that their ancestors had come to this isolated haven, bringing their families and the village people, to escape from the turmoil during the Qin Dynasty and that from then onwards, they had been cut off from the outside world. They were curious to know what dynasty it was now. They did not know the Han Dynasty, not to mention the Wei and the Jin dynasties. The fisherman told them all the things they wanted to know. They sighed. The villagers offered him one feast after another. They entertained him with wine and delicious food. After several days, the fisherman took his leave. The village people entreated him not to let others know of their existence.Once out, the fisherman found his boat and rowed homeward, leaving marks all the way. When he came back to the jun, he reported his adventure to the prefect, who immediately sent people to look for the place, with the fisherman as a guide. However, the marks he had left could no longer be found. They got lost and could not find the way.Liu Ziji of Nanyang(3) jun , a learned scholar of high repute, was excited when he heard the fisherman's story. He devised a plan to find the village, but it was not carried out. Liu died soon afterwards, and after his death, no one else made any attempt to find it.Notes:(1). Taiyuan was the title of the reign of Emperor Xiaowu of the Eastern Jin Dynasty (376-396).(2). Wuling is today's Changde City, Hunan Province.(3). Nanyang is today's Nanyang City, Henan Province.About the author:Tao Yuanming (365-427) was a great poet during the Eastern Jin Dynasty, and was born in Jiujiang County, Jiangxi Province. Dissatisfied with the politics of his time, he resigned from his post as magistrate of Pengze County. He retired to his home village and lived there for the next twenty-three years till his death. This piece of writing is regarded as one of the earliest pieces about Utopianism in Chinese literature.尤金·A·奈达评译《桃花源记》导读:尤金·A·奈达(Eugene A. Nida,1914-),美国现代著名的语言学家和翻译理论家,组织和指导过几个大型的《圣经》翻译和修订项目,包括二十世纪七十年代出版的《圣经:现代英语译本》(Today's English Version)。

理论与实践方向参考书目1. 中文部分《口译技巧》<法>达尼卡.塞莱斯科伟奇著,孙慧双译.北京:北京出版社,1979年12月第一版.《英汉翻译手册》钟述孔。

北京:商务印书馆,1980年3月第一版。

《翻译理论与技巧论文集》。

本公司选编,中国对外翻译出版公司,1983年8月第一版。

《外国翻译理论评介文集》本公司选编,中国对外翻译出版公司,1983年8月第一版。

《意态山来画不成?―――文学翻译丛谈》翁显良,北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1983年12月第一版。

《翻译研究论文集》(1894-1948)中国翻译工作者协会《翻译通讯》编辑部编,北京:外语教学与研究出版社,1984年2月第一版。

《翻译研究论文集》(1949-1983)中国翻译工作者协会《翻译通讯》编辑部编,北京:外语教学与研究出版社,1984年11月第一版。

《翻译论集》罗新璋编,北京:商务印书馆,1984年5月第一版。

《新编奈达论翻译》谭载喜编,北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1999年10月第一版。

《翻译的艺术》许渊冲,北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1984年10月第一版。

《七缀集》钱钟书,上海:上海古籍出版社,1985年第一版。

《文体与翻译》刘宓庆,北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1986年3月第一版。

《文学翻译原理》张今。

开封:河南大学出版社,1987年9月第一版。

《等效翻译探索》金隄,北京:中国对外翻译出版公司。

1989年4月第一版,1998年7月第二版。

《翻译:思考与试笔》王佐良,北京:外语教学与研究出版社。

《中国翻译文学史稿》陈玉刚,北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1989年8月第一版。

《当代翻译理论》刘宓庆,北京:中国对外翻译出版公司,1999年8月第一版。

《西方翻译简史》谭载喜,北京:商务印书馆1991年5月第一版。

《中国译学理论史稿》陈福康,上海:上海外语教育出版社,1992年11月第一版,2000年6月第二版。

《中国当代翻译百论》杜承南、文军主编。

公司金融的理论与实践:来自实地的证据关于资本成本、资本预算和资本结构问题,我们调查了392位首席财务官。

大的公司主要依靠现值技术和资本资产定价模型,而小公司相对地比较喜欢使用回收期标准。

当发行债务时,公司比较注重维护财务弹性和比较好的信用等级;当发行股票时,比较注重每股收益稀释和近期股票价格升值情况。

我们发现了对于支持优序融资假说和交易资本结构假说的支持,但是却很少找到经理关心资产替换、不对称信息、交易成本、自由现金流或者个人税务方面的证据。

关键词:资本结构资本成本股权成本资本预算折现率项目估值调查1. 简介在这篇文章中,我们对一项描述公司金融的现行实践的综合调查作了一个分析。

在这个领域中,最著名的实地研究也许就是约翰.林特纳的开创新的股利分配策略分析理论。

那个研究的结论至今仍被引用,并深刻地影响着股利分配策略的研究方式。

在很多方面,我们的目标和林特纳的有点相似。

我们的调查描述了公司金融的现行实践。

我们希望研究者们能利用我们的结果来发展新的理论—并且潜在地修改或者放弃已经存在的观点。

我们也希望从业者们能够从我们的结果中得到启发,通过观察其他的公司是怎样运行的以及确认其他学术文献没有完成的地方。

我们的调查跟以前的一些调查在很多方面都有不同。

首先,我们的调查的范围很广。

我们检测了资本配置,资本成本和资本结构。

这让我们可以把跨领域的结果联系在一起。

例如,有些公司在考虑资本结构问题时会优先考虑财务弹性,我们就调查了这些公司在考虑资本预算决定时是否也会注重实物期权。

我们在每个领域都进行了深入的探索,总共询问了100多个问题。

其次,我们抽样调查了接近4440个公司的大范围截面数据。

总计有392为首席财务官回应了我们的调查,回复率为9%。

我们所知道的第二大范围的调查是摩尔和理查特做的,调查了298个大公司。

我们研究了可能的未回复偏差,得出结论是我们的样本可以作为全部人口的代表。

第三,我们依据公司特征对回复结果进行了分析。

奈达翻译理论对英译汉的指导本文主要讨论奈达理论对翻译实践,主要是英译汉的指导。

文章简要总结了奈达理论的重点内容,介绍了奈达提出的语义范畴和如何利用核心句分析源语表层结构,并以实例说明奈达理论对英译汉的指导意义。

标签:奈达翻译理论意义语义范畴核心句The Guidance of Nida’s Translation Theory on E-C TranslationLi He(English Department,Binhai School of Foreign Affairs of Tianjin Foreign Studies University,Tianjin 300270)Abstract:This paper focuses on the guidance of Nida’s translation theory on the practice of E-C translation. It proves how Nida’s semantic categories and kernel sentences contribute to the analysis of the surface structure of the original and shows how Nida’s theory guides the translation practice with some examples.Key words:Nida’s translation theory;meaning;semantic categories;kernel sentences《翻译理论与实践》顾名思义,是一本理论与实践并举的专著。

奈达博士在1969年的出版前言中提到此书旨在帮助译者掌握理论原理以及在翻译过程中学会如何操作,以此获得一定的实践技巧。

奈达在此书的前两章阐述了他基本的翻译理论,其余章节则构建了一个翻译的操作步骤,即向读者展示怎么做才能得到好的译文。

The theory and practice of translationEugene A. Nida and Charles R. Taber 1974Contents1.A new concept of translation2.The nature of translating3.Grammatical analysis4.Referential meaning5.Connotative meaning6.Transfer7.Restructuring8.\9.Testing the translationChapter One The old focus and the new focusThe older focus in translating was the form of the message, and the translator too particular delight in being able to reproduce stylistic specialties, ., rhythms, rhymes, plays on words, chiasmus, parallelism, and usual grammatical structures. The new focus, however, has shifted from teh form of the message to the response of the receptor. Therefore, what one must determine is the response of the receptor to te translated message, this response must be compared with the way in which the original receptors presumably reacted to the message when it was given in its original setting.Chapter Two Translating consists in reproducing in the receptor language the closest natural equivalent of the source-language message, first in terms of meaning and secondly in terms of style. But this relatively simple statement requires careful evaluation of several seemingly contradictory elements.Reproducing the messageTranslating must aim primarily at “reproducing the message.” To do anything else is essentially false to one’s task as a translator. But to reproduce the message one must make a good many grammatical and lexical adjustments.Equivalence rather than identity。

The translator must strive for the equivalence rather than identity. In a sense, this is just another way of emphasizing the reproduction of the message rather than the conversation of the form of the utterance, but it reinforces the need for radical alteration of a phrase, which may be quiet meaningless.A natural equivalentThe best translation does not sound like a translation. In other words, a good translation of the Bible must not be “cultural translation”. Rather, it is a “linguistic translation”. That is to say, it should studiously avoid “translationese”--formal fidelity, with resulting unfaithfulness to the content and the impact of the message.The priority of meaningAs has already been indicted in the definition of translating, meaning must be given priority, for it os the content of the message which is of prime importance for Bible translating.The significance of styleThough style is secondary to content, it is nevertheless important, one should not translate poetry as though it were prose, nor expository material as though it were straight narrative.)In trying to reproduce the style of the original one must beware, however, of producing something which is not functionally equivalent.A system of prioritiesAs a a basis for judging what should be done in specific instances of translating, it is essential to establish certain fundamental sets of priorities: (1) contextual consistency has priority over verbal consistency ( or word-for-word concordance), (2) dynamic equivalence has priority over formal correspondence, (3) the aural form of language has priority over the written form, (4) forms that are used by and acceptable to the audience for which a translation is intended have priority over forms that may be traditionally more perspectives.The priority of dynamic equivalence over formal correspondenceIf we look at the translations in terms of the receptors, rather than in terms of their respective forms, then we introduce another point of view; the intelligibility of the translation. Such intelligibility is not, however, to be measured merely in terms of whether the words are understandable, and the sentences grammatically constructed, but in terms of the total impact, the message has on the one who receives it.Dynamic equivalence is therefore to be defined in terms of the degree to which the receptors of the message in the receptor language respond to it in substantially the same manner as the receptor in the sourcelanguage. This response can never be identical, fro the culture and historical settings are too different, but there should be a high degree of equivalence of response, or the translation will have failed to accomplish its purpose.;It would be wrong to think, however, that the response of the receptors in the second language is merely in terms of comprehension of the information, for communication is not merely informative. It must also be expressive and imperative if it is to serve the principal purposes of communications.Of course, persons may insist that by its very nature a dynamic equivalent translation is a less “accurate” translation, for it departs further from the forms of the original. To argue in this manner, however, is to use “accurate”in a formal sense, whereas accuracy can only be rightly determined by judging the extent to which the response of the receptor is substantially equivalent to the respond of the original receptors. In other words, does the dynamic equivalent translation succeed more completely in evoking in the receptors responses which are substantially equivalent to those experienced by the original receptors If “accuracy”is to be judged in this light, then certainly the dynamic equivalent translation is not only moe meaningful to the receptors but also more accurate. This assumes, of course, that both the formal correspondence translation and the dynamic equivalent translation do not contain any overt errors of exegesis.Grammatical analysisThere are three major steps in analysis: (1) determining the mining the meaningful relationships between the words and combinations of words, (2) the referential meaning of the words and special combinations of words, idioms, (3) the connotative meaning.Kernel sentencesWe soon discover that we have simply recast the expressions so that events are expressed as verbs, objects as nouns, abstracts (quantities and qualities) as adjectives or adverbs. The only other terms are relationals, ., the prepositions and conjunctions.—These restructures expressions are basically what many linguistics call “kernels”; that is to say, they are the basic structural elements out of which the language builds its elaborate surface structures. In fact,one of the most important insights coming from “transformational grammar” is the fact that in all languages there are half a dozen to a dozen basic structures out of which all the more elaborate formations are constructed by means of so called “transformations”. In contrast, back transformation, then, is the analytic process of reducing the surface structure to its underlying kernels.Semantic adjustments made in transferIn transferring the message from one language to another, it is the content which must be preserved at any cost; the form, except in special cases, such as poetry, is largely secondary, since within each language, the rules for relating content to form are highly complex, arbitrary, and variable.Of course, if by coincidence it is possible to convey the same content in the receptor language in a form which closely resembles that of the source, so much the better; we preserve the form when we can, but more than the form has to be transformed precisely in order to preserve the content. An expressive effort to preserve the form inevitably results in a serious loss or distortion of the message.Obviously in any translation there will be a type of “loss”of semantic content, but the process should be so designed as to keep this to a minimum. The commonest problems of the content transfer arise in the following areas: (1) idioms, (2) figurative meanings, (3) shifts in central components of meaning, (4) generic and specific meanings, (5) pleonastic expressions, (6) special formulas, (7) redistribution of semantic components, (8) provision for contextual conditioning.(8)In other instances one may find it important to employ a descriptive phrase so as to provide some basis for comprehending the significance of the original.It must be further emphasized that one is not free to make in the text any and all kinds of explanatory additions and/or expansions.,Testing the translationOnce the process of restructuring has been completed, the next essential step is th e testing of the translation. This should cover the entire range of possible problems: accuracy of rendering, intelligibility, stylistic equivalence, etc. But to do this, one must focus attention not upon the extent of verbal correspondence but upon the amount of dynamicequivalence. This does not mean, of course, that the translation is judged merely on the extent to which people like the contents. Some people may object strongly to the themes and the concepts which are communicated, but there should not be anything in the translation itself which is stylistically awkward, structurally burdensome, linguistically unnatural, and semantically misleading or incomprehensible, unless, of course, the message in the source language has these characteristics ( the task of the translator is to produce the closest natural equivalent, not to edit or to rewrite). But to judge these qualities one must look to the potential users.The problem of overall lengthIt only means that in the process of transfer from one linguistic and cultural structure to another, it is almost inevitable that the resulting translation will turn out to be longer.This tendency to greater length is due essentially to the fact that one wishes to state everything that is in the original communication but is also obliged to amke explicit in the receptor language what could very well remain implicit in the source language text, since te original receivers of this communication presumably had all the necessary background to understand the contents of the message.(He analyzes its components builds in proper redundancy by making explicit what is implicit in the original, and then produces something the readers in the receptor language will be able to understand.Types of expansionsThe expansions may perhaps be most conveniently divided between syntactic (or formal) expansions and lexical (or semantic) ones.Lexical expansions in marginal helpsIn making explicit what is fully implicit in the original translation, one can ofter insert material in the text itself without imposing undue strains upon the process of translation.Such information may only be part of the general cultural background shared by the participants in the source language. This type of information cannot be legitimately introduced into the text of a translation, but should be placed in marginal helps, either in the form of glossaries, where information about recurring terms is gathered together in summary fashion, or in marginal notes on the page where the difficulty in understanding occurs.Practical texts.Therefore, if a translator really wants to obtain satisfactory replies to direct questions on specific problems, the only way to do so is by supplying people with alternatives. This means that one must read a sentence in two or more ways, ofter repeating such alternatives slowly (and , of course, in context). And then ask such questions as: “which way sounds the sweetest”“which is planner”...Explaining the contentsA secondary very important way of testing a translation is to have someone read a passage to someone else and then to get this individual to explain the contents to other persons, who did not hear the reading.Reading the text aloudPublication of sample materialThe ultimate basis for judging a translation。