Student Personnel Point of View 1949

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:275.32 KB

- 文档页数:12

培养大学生信息素养的意义及途径(Meaning and methods of educating the students information literacy)Two thousand and nine point sixSignificance and ways of training university students' Information LiteracyLiang Jianguo - Zhang Bin Wang Xinwei(Qingdao Harbour Vocational and Technical College, Shandong, Qingdao 266404)[author's brief introduction]: Liang Jianguo (1981~), male, teacher of Qingdao Harbour Vocational and Technical College.Abstract: This paper introduces the definition and content of information literacy, and analyzes the cultivation of College Students' creative ability, self-learning ability and the formation of moral quality with information literacyIt points out the main ways to improve the information literacy level of college students in China: constructing new digital libraries and optimizing various information;To carry out the information literacy education that adapts to each other; to strengthen the collection construction of the library; to train a full-time high-level information teacher team.Key words: college students; information literacy; lifelonglearning; University LibrariesInformation literacy means that people acquire knowledge and information in the information societyInformation initiative and basic abilities. As we enter the 21 worldJi, the advent of the information age, has brought great changes to societyThe quality of information literacy is also getting higher and higher, and is responsible for the future of the nationTo set up a task for college students, information literacy is essential qualityFirst, information literacy education is related to the improvement of College Students' innovative ability,It is related to the cultivation of autonomous learning ability, which is related to quality education in Colleges and UniversitiesSuccess or failure. Therefore, it is new to train and improve the information literacy of College StudentsAn important task of educational reform in the 21st century.First, the definition and content of information literacyIn 1974, Paul Zekas, President of the Information Industry Association of the United StatesZurkowski (Paul) defines information literacy as "people are solving."Take advantage of information technology and skills when deciding a problem". Later, information literacyThe definition was constantly developed, and in 1992, the American Library Association raisedInformation literacy refers to the ability to determine when information is needed and canThe ability to retrieve, evaluate, and utilize information effectively. 1992The American Library Association and the American Educational Communications and Technology AssociationStep has formulated the student to study 9 big literacy standards, this standard from the letterInterest, skills, independent learning and social responsibility are described in three aspects,It further expands and enriches the connotation and extension of information literacy. This [1]It is the definition of authority put forward by foreigncountries, and there are dozens of scholars in ChinaYears of exploration, there has been no authoritative statement, but basically have been connectedThe following definition is made: information literacy is the individual catching in a purposeful wayOne of the processes in the process of catching, selecting, storing, processing, and utilizing informationThe composite quality is the individual's attitude towards information activities and informationAcquisition, analysis, processing, evaluation, innovation, communication and so onCombining ability. Information literacy should be defined as the way individuals treat informationDegree, and the synthesis in the process of carrying out information related activitiesAbility to combine and self-discipline.Information literacy is a comprehensive quality, is the original human cultureAn extension of the new era, it can include the following: (1) letterConcept of interest. The attitude of an individual to information includes how to recognize informationDoes the positive value and the negative influence of the society have the consciousness to obtain the letter?Interest,Understanding, insight, and observation of various types of information. (2)Information knowledge. Information knowledge is what people are using information technology tools,Expanding the ways of information dissemination and improving the efficiency of information exchangeThe nature and characteristics of information, the law of information movement, and the information systemAnd its principles, information technology and information methodsKnowledge constitutes the basis of information literacy. (3) information ability. informationThe core of literacy is whether an individual is able to achieve what he wantsTake, synthesize, analyze, evaluate information, and process informationOn the basis of information, innovate and form independent views and generate new onesInformation. (4) information morality. Information morality is the spirit of information literacyWithout information morality, information activities can not only take place for societyFortune, on the other hand, creates disaster, even though there is no actual workYes, but it's what information literacy calls literacy. letterInterest literacy is essentially a humanistic quality, can give technical divisionLearning to inject humanistic care.The United Nations Educational, scientific and Cultural Organization says that only lifelong learning can be achievedTrain qualified qualified personnel, and only those who have information literacy,In order to implement lifelong learning, it becomes a required learning in the era of knowledge economyFour hundred and two thousand and nine point sixInnovative and high quality talents. Comprehensive quality education should be implementedTherefore, we must educate the college students in information literacy.Two, the significance of university students' Information Literacy Education1. information literacy relates to the cultivation of innovative ability of College StudentsNow, our country's education is turning from examination oriented education to quality educationChange, and the ability to innovate is the core content of quality education.As the name suggests, innovation is the creation of new thingsBreakthrough. "Content" has a very wide range, including societyVarious aspects of the field, such as academic theoretical innovation, enterprise systemDegree innovation, state system innovation and so on. Precisely because there are always newReplace the old things, will have social development and progress.New things do not arise out of thin air. They need the knowledge they haveShield. Newton has modestly attributed his achievements to "because of me."Stand on the shoulders of giants". Because of this, information literacy can be achieved in innovationThe cultivation of force is the foundation, so to speak, there is no definite informationLiteracy is nothing new. This is especially true for College StudentsWith the reform of higher education, the demand for college students is from knowledgeThe memory into the importance of scientific research ability, scientific research is the goalInnovation, while scientific research capability is based on the accumulation of knowledge and sufficient informationMastery as premise. Have the right information concept and sufficient informationKnowledge and the necessary information ability, college students can achieve innovation. IfIt is difficult for college students to accept and preserve knowledge, but it is difficult to accomplish itAnd other institutions to become social development "gas station" mission. Information literacy isThe essential quality of creative talents is the catalyst of innovation activities.Constructivism is regarded as the latest theoretical foundation of modern educational technologyThink, knowledge is a learner in certain social background, with the aid of himHuman help,Make full use of all kinds of learning resources; think bigStudents are the main body of information processing, emphasizing that college students should study autonomously,Self discovery and active exploration; the most conducive to learning is divergentThinking, reverse thinking, divergent thinking. Therefore, information literacy educationInnovation education has a special position.2. information literacy relates to the improvement ofself-study ability of College StudentsOne of the goals of quality education in China is to cultivate students' AutonomyAbility to learn. From the point of view of students, from "want me to learn""To "I want to learn" changes; from the point of view of educators, that isRealize its role from "teach people to fish" to "teach people to fish". sinceThe cultivation of academic ability is largely related to the cultivation of information literacyThere is consistency, but the two are different angles. asToday, the process of social informatization is speeding up and social information resources are expanding constantly,The proportion of information outside the library's literature resources has been increasing and carrierForms also change constantly. Some people learn at CollegeAfter five years of knowledge, more than half will not be used, a lot of new knowledgeThe acquisition mainly depends on self-study. [2] therefore,higher education must be paid attention toThe cultivation of important students' self-study ability, and the cultivation of self-study abilityIn essence, through the cultivation of university students' information literacy, learn how to distinguishAbout information, how to collect and obtain information, in this sense,Information literacy is an important weapon to gain self-study ability. And information literacyEducation is the introduction of knowledge and the importance of information to the UniversityThe student sets up the correct information concept, obtains the enough information knowledgeThrough literature retrieval and the use of information skills and methods of training to make itHave excellent information skills and form good letters in the processInterest morality can use the network to seek scientific information and communicate with each otherCapable of carrying out search, selection, or application of information with purposeInnovation on the basis of information, and really get rid of the passive learning processThe recipient's status becomes lifelong independent with good information literacyLearner。

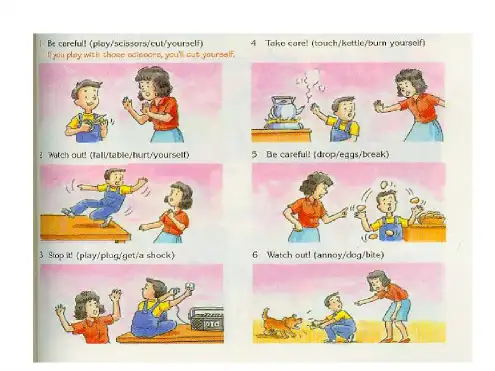

译林版九年级英语下册第二单元全套教学案设计译林版九年级英语下册第二单元全套教学案设计Unit 2 Great peopleWelcome to the unitTeaching aims:1. Learn some new words and expressions about describing great people.2. Introduce some great people in history and talk about them.Teaching procedures:Step 1 PresentationShow some pictures to introduce some great people and ask: Do you admire them?Why or why not?Step 2 PresentationIntroduce the six great people in history with pictures and captions.Peter Tchaikovsky was a Russian. He was a composer of classical.QianXueson was a great scientist. He was the pioneer of China’s space technology programme.William Shakespeare was English. He was a great writer of English literature. Nelson Mandela was once the president ofSouth Africa. He was a fighter for the rights of black Africans all his life.Thomas Edison was a great inventor who created over 1,000 inventions.Christopher Columbus was a great explorer. He was one of the first Europeans to discover America.Step 3 Write and matchComplete Part A& B on page 21.Mr Wu is showing the Class 1, Grade 9 students the pictures of some famous people. Help the students write the correct word under each picture.Keys: inventor explorer writer president scientist composer Mr Wu is telling the students about the famous people in Part A. Help the students match the names on the left with the correct information on the right.1. Christopher Columbus2. William Shakespeare3. QianXueson4. Thomas Edison5. Nelson Mandela6. Peter Tchaikovskya. Chinese, the pioneer of China’s space technology programmeb. South African, a fighter for the rights of black Africans allc. American, created over 1,000 inventionsd. Italian, one of the first Europeans to discover Americae. Russian, a composer of classical musicf. English, a great writer of English literatureKeys: 1-d 2-f 3-a 4-c 5-b 6-eStep 4 Listen and answerI. Listen to the conversation between Hobo and Eddie and answer the following questions:1. What are they talking about?2. Who does Eddie think is the greatest person in history?3. Why does Eddie think so?Keys: 1. They are talking about who is the greatest person in history.2. Paul Yum.3. Because he thinks Paul Yum invented his favourite food.II. Read and act out the conversation.Step 5 Explanation1. I’ve never heard of him.hear of … 听说hear 听见,听到e.g. 你能听到她在隔壁房间唱歌吗?Can you hear her singing in the next room?你以前听说过这首歌吗?Have you heard of this song before?2. He invented my favourite food.invent vt.发明inventor n. 发明家,发明者invention n.发明物,创意e.g. 托马斯·爱迪生,一位伟大的发明家,发明了1000多种发明Thomas Edison, a great inventor, invented over 1,000 inventions.3. Who do you think is the greatest person in history, Eddie?句中的do you think是该疑问句中的插入部分。

托福听力tpo48section1对话讲座原文+题目+答案+译文Conversation1 (1)原文 (1)题目 (3)答案 (5)译文 (5)Lecture1 (6)原文 (6)题目 (9)答案 (11)译文 (11)Lecture2 (13)原文 (13)题目 (16)答案 (18)译文 (18)Conversation1原文NARRATOR:Listen to a conversation between a student and a university employee at the campus employment office.FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Hi,can I help you?MALE STUDENT:I hope so.My name's Mark Whitman,I'm--FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Don't I remember you from last year?You worked in uh…where was it,the art library?MALE STUDENT:Yeah.You're good.That was me.And I really enjoyed the work.FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Right.Yeah,your supervisor gave us some really great feedback at the end of the year.“Oh,he’s so organized,always on time,helpful...”MALE STUDENT:Really?Well,I'm glad.It was a good job.FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Well,we usually try to match students'jobs with their academic interests...MALE STUDENT:Yeah,I'm not exactly sure what career I'm headed for,but librarian is a possibility.It was a great experience to learn how it works and,and meet some people working in the field.But for this year...well,that’s what I wanted to ask about.FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Oh.How come you waited so long to come in?You know how fast campus jobs fill up.If you’d come in earlier,you could probably have gotten the library job again--I mean,since you have the experience from last year,you don't need the training and all...but it's been filled now.MALE STUDENT:Yeah,I know.But I'd planned to get a job working at a restaurant off-campus this year.I really need to make more money than I did last year,and working as a waiter,there's always the tips.But…I've tried a ton of places and I haven't found anything.I know it’s really late,but well,uh,I was wondering…if maybe there was some job that hadn't been taken?Or maybe,umm,someone started a job and,ya know,had to drop it or something?FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Well,I doubt you'll find..MALE STUDENT:Could you,could you possibly check?I know it's a long shot but…My friend Suzanne,she takes photography classes in Harrison Hall.And,um,she sort of thought there might be an opening in the janitorial staff.FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Um,why does your friend,the photography student,think she has information about a janitorial staff opening?I'm pretty sure those jobs're filled. In fact,I remember taking lots of applications for them.Let me double check itonline…MALE STUDENT:She said the whole studio arts building and especially the photo lab have been kind of,uh…sort of messy lately?I mean,she says there's,uh,chemicals and stuff left out and,ya know,it's like no one's been cleaning up.But that could just be,ya know,students using the lab after hours or something.Like,after it's been cleaned.FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Hmm…hang on.There's…uh…there is um…an asterisk…uh, next to one of the job numbers here.There's a note.Let's see…Huh!…Your friend's right.Seems like one of the student janitors quit a couple weeks ago for some reason….Well,whatever.It looks like this is your lucky day.MALE STUDENT:Wow!That is so great!So who's the contact person?FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Check with the janitorial office.MALE STUDENT:Fine.Thanks so much.题目1.Why does the student go to the employment office?A.To get feedback from his previous supervisorB.To try to have his work hours reducedC.To find out about getting an on-campus jobD.To compare various job offers that he has received2.Why does the university employee seem surprised at the student's request for on-campus jobs?A.Because she knows he is interested in off-campus jobsB.Because she expected him to apply earlier in the semesterC.Because she knows he recently quit an on-campus jobD.Because she thought he already had an on-campus job3.What does the student imply about the job he had at the library last year?A.It did not require as much training as jobs in restaurants.B.It did not pay as well as jobs in restaurants.C.It offered a flexible work schedule for students.D.It convinced him to become a librarian in the future.4.Why does the student mention his friend Suzanne?A.To compare his restaurant job with her job at the photograph labB.To suggest that he wants to work with herC.To explain why students do not want to have janitorial jobsD.To explain why he thinks there is a job opening5.What can be inferred about the woman when she says this:FEMALE EMPLOYEE:Um,why does your friend,the photography student,think she has information about a janitorial staff opening?I'm pretty sure those jobs're filled.A.She believes that there is no way to confirm that information.B.She is concerned about information security.C.She doubts the accuracy of the information.D.She does not find the information helpful.答案C B BD C译文听一段一个学生和大学工作人员在校园职业介绍办公室的对话。

美高校学生事务管理对中国高校学生工作的启示解勇国(陕西师范大学学工部部长)一、美国高校学生事务管理的理念1、学生事务与学生事务管理学生事务(Student Affairs)与学生事务管理(Student Affairs Administration or Practice)是美国高等教育的产物,是典型美国式的用法和表达。

它是相对于学术事务(academic affairs)及其管理而言的,包括学生入学、新生适应、注册报到、咨询服务、住宿生活、经济资助、课外活动、职业发展、学生健康、纪律处理等所有非学术性学生事务的总称,基本对应于我国高校学生工作。

2、学生事务美国高校学生事务出现于美国高等教育发展和变化的时代,伴随美国高等教育发展变化的进程,学生事务在不同的历史阶段所表达的内涵也不断发展变化,而且具有鲜明的时代特征,从“学生人事”(student personnel )、“学生服务”(student service)到“学生发展”(student development),再到的“学生学习”(Student Learning)。

这几个概念除了学生人事之外,学生服务、学生发展和学生学习仍是当前美国学生事务的重要内容。

3、学生事务管理“学生事务管理”是个典型的美国术语,曾经受到过理性主义、新人道主义、实用主义和存在主义哲学思想的影响。

在美国,“学生事务习惯用来描述校园内对学生课外教育负责的组织结构或单位,学生事务管理一般被理解为这一职业领域的总称”。

学生事务管理,通俗一点来讲,就是对学生事务的管理。

与我国通行的校院系两级管理体制和条块结合运行机制有明显不同的是,美国高校学生事务管理的机构设置和权限分配只在学校一级,学生事务及其管理是直接面对学生及学生组织进行的管理。

而学院和系一级没有对应的组织和分工要求。

当然,美国是一个典型的高等教育分权国家,学生事务与高校其他事务一样,主要是地方与大学的事情。

美国几乎所有高校都独立设置学生事务管理的组织机构,自主开展学生事务工作,大多数美国的学生事务工作者都是从本校出身,不同的学校又会有不同的特色。

CopyrightZEB-CAM™ User’s Manual © 2017 GeoSLAM Ltd. All rights reserved.CONTENTSIntroduction (5)1.1Specification (5)1.2Principal of operation (5)1.3List of parts (6)Safety (7)2.1General safety (7)2.2System Disposal (7)2.3Installation (7)2.4Further help and information (7)Data capture (9)3.1Mounting ZEB-CAM (9)3.2ZEB-CAM SETTINGS (9)3.3Capturing data with ZEB-CAM (10)Data Processing (11)GOPro Basics (14)5.1Charging the battery (15)5.2Inserting and removing the memory card (16)5.3Wireless settings (17)INTRODUCTIONThe ZEB-CAM is a colour camera accessory for GeoSLAM’s ZEB-REVO portable laser scanner. ZEB-CAM incorporates a GoPro Hero Session action video camera. The image data collected by the camera can be viewed alongside the 3D point cloud created by the ZEB-REVO and used to extract contextual information.1.1SPECIFICATIONCamera Type GoPro Hero SessionMode VideoVideo Resolution 1440pFrames per Second 30Image Resolution 1920 x 1440Field of View Ultra-wide (~120°x 90°)Logging Medium Internal SD cardPower Supply Internal BatteryBattery Life 2 hours continuous useImage Syncing Optical flow using integrated inertial sensor1.2PRINCIPAL OF OPERATIONThe operation of the camera on ZEB-CAM is independent from operation of the ZEB-REVO. The camera must be started and stopped manually at the start and end of each scan. The resulting video data is logged directly to an internal microSD card in the camera.The video data from ZEB-CAM and laser data from ZEB-REVO are combined in the GeoSLAM Desktop processing application. A unique optical flow algorithm is used to determine the relative timing between the video and laser data.The viewer in GeoSLAM Desktop can be used to view the video data alongside the point cloud data from the ZEB-REVO.1.3LIST OF PARTSSAFETY2.1GENERAL SAFETYThe ZEB-CAM camera accessory should only be used by trained operators. Always follow basic safety precautions when operating the ZEB-CAM to reduce the risk of personal injury and to prevent damage to the equipment. Do not operate the equipment with suspected defects or obvious mechanical damage. Please refer all servicing of the equipment to qualified service personnel. Only use the components and accessories supplied with your system or other accessories recommended by GeoSLAM Ltd. Before operating the system for the first time please read this manual.2.2SYSTEM DISPOSALWhen the ZEB-REVO Portable Mapping System reaches the end of itslife-cycle please dispose of the equipment in accordance withDirective 2002/96/EC on Waste Electrical and Electronic equipment(WEEE).GeoSLAM Ltd is prepared to take back the waste equipment andaccessories free of charge at the manufacturing unit in Bingham, UKfor proper treatment with the objectives of the WEEE.2.3INSTALLATIONThe ZEB-CAM can only be used with be used in conjunction with a GeoSLAM ZEB-REVO handheld laser scanner. For instructions how to mount ZEB-CAM see Section 3.1 Mounting ZEB-CAM2.4FURTHER HELP AND INFORMATIONContact GeoSLAM by any of the following methods:Phone: +44 1949 831814Email:****************Website:DATA CAPTUREThis chapter describes how to mount ZEB-CAM to the ZEB-REVO and how to operate ZEB-CAM during REVO data capture.3.1MOUNTING ZEB-CAMIf the ZEB-CAM is not already mounted on the ZEB-REVO, mount the camera by following these steps:1Remove the ZEB handle by unscrewing the orange knurled wheel at the top of the handle.2Fit the ZEB_CAM to the base of the REVO using the 3 x M4x8 caps screws supplied with the ZEB-CAM and tighten with the 3mm hex key. Do notovertighten or you risk stripping the threads in the base of the REVO, justnip the screws tight.3Refit the handle into the underside of the ZEB-CAM mount.4Connect the Micro-USB end of the ZEB-CAM cable into the socket on the side of ZEB-CAM mount.5Connect the other end of the ZEB-CAM cable to the AUX (blue) socket on the ZEB-DL2600 data logger.3.2ZEB-CAM SETTINGSThe GoPro Hero Session camera is delivered with configuration settings required for use in ZEB-CAM pre-set. If for any reason the camera settings are changed the settings listed in Table 3-1 must be reset to the values shown in order for the ZEB-CAM data to process correctly.3.3CAPTURING DATA WITH ZEB-CAM(real-time) users please refer to section 3.3.2Ensure the microSD card is inserted into the card slot behind the cover on the side of the camera (see 5.2 Inserting and removing the memory card).Ensure there is adequate free space on the SD card.Ensure the camera battery is adequately charged (see 5.1 Charging the battery). Connect the ZEB-REVO to the AUX port on the data logger, boot up the data logger. Once booted, he LED on the ZEB-REVO should pulse red twice per second to indicate that the ZEB-CAM has been detected and the system is in standby mode. Without the ZEB-CAM the LED will pulse once per second.Initiate a scan as described in the ZEB-REVO User Manual.After the system has initialised and the REVO LED has changed to green and before activating the rotation of the REVO head, [short} press the shutter/select button on the top of the camera. After approximately 2 seconds the camera emits three beeps, and automatically begins recording video. The camera status led flashes red while the camera is recording.Warning – do not hold down the shutter/select button [long press]. This will switch the camera from video to time lapse mode.Immediately after starting the video recording, start the REVO rotation by pressing the button on the side of the REVO, pick up the scanner and start the scan.Perform the scan following the guidelines set out in the ZEB-REVO User’s Manual.At the end of the scan, stop the REVO head rotation and immediately stop the video recording by [short] pressing the shutter/select button on top of the camera. The camera beeps several times and automatically powers off to maximize battery life.Ensure the microSD card is inserted into the card slot behind the cover on the side of the camera (see 5.2 Inserting and removing the memory card).Ensure there is adequate free space on the SD card.Ensure the camera battery is adequately charged (see 5.1 Charging the battery). Connect the ZEB-REVO to the USB socket on the REVO RT data processing unit, boot up the data processing unit and initiate the scan in the same way described in the ZEB-REVO RT User Manual.After the system has initialised and before activating the rotation of the REVO head, [short} press the shutter/select button on the top of the camera. After approximately 2 seconds the camera emits three beeps, and automatically begins recording video. The camera status led flashes red while the camera is recording.Warning – do not hold down the shutter/select button [long press]. This will switch the camera from video to time lapse mode.Immediately after starting the video recording, start the REVO rotation by pressing the button on the side of the REVO, pick up the scanner and start the scan.Perform the scan following the guidelines set out in the ZEB-REVO RT User Manual.At the end of the scan, stop the REVO head rotation and immediately stop the video recording by [short] pressing the shutter/select button on top of the camera. The camera beeps several times and automatically powers off to maximize battery life.DATA PROCESSINGThe ZEB-CAM records video data to internal microSD card in MP4 format. Remove the microSD card from the camera and copy the MP4 file(s)* to the processing computer using the microSD to SD or microSD to USB adapter.Select the corresponding video MP file(s)* when requested to do so by the GeoSLAM Desktop application.*ZEB-CAM video files are limited in files size to 4GB due to a limitation of the FAT32 disk format. Videos in excess of 4GB (approximately 9 minutes) are split into multiple MP4 files or chapters, each with a common file name plus index number to differentiate each chapter. All chapters must be selected at the start of processing in order for the data to process correctly.GOPRO BASICS1 Camera Status Screen2 Shutter/Select Button3 Microphone4 Camera Status LED (red) / Wireless Status LED (blue5 Micro-USB Port6 microSD Card Slot7 Info/Wireless Button5.1CHARGING THE BATTERYThe integrated battery comes partially charged. No damage occurs to the camera or battery if used before being fully charged. To Charge the Battery:1Open the side door.2Connect the supplied USB cable to the Micro-USB port.3Connect the other end to a 5V 1A USB power source, e.g. a standard USB port on a computer.The camera status led turns red during charging and turns off when charging is complete. When charging the camera with a computer, be sure that the computer is connected to a power source. If the camera status lights do not turn on to indicate charging, use a different USB port.5.2INSERTING AND REMOVING THE MEMORY CARDTo insert the memory card:1Ensure the camera is powered off.2Open the side door.3Insert the microSD memory card into the card slot at a downward angle with the label facing down.4Press the card in until it latches in placeTo remove the memory card1Ensure the camera is powered off.2Open the side door.3Gently press the memory card in to unlatch it.4Carefully extract the memory card5.3WIRELESS SETTINGSThe GoPro can be used remotely using the free GoPro App for Mobile via a WiFi connection. We do not recommend using in this mode since it significantly reduces the battery charge life.The camera WiFi settings have been pre-set to the last eight digits of the camera serial number. The serial number can be found on the inside of the side door:SSID NNNNNNNNPassword NNNNNNNNWhere NNNNNNNN is the last eight digits of the camera serial number.。

《大学英语Ⅱ》练习题适用层次:专升本Unit One Is There Life on Earth?ⅠExercisesDirection: Fill in the blanks with the words or expressions given below.proceed, pollute, originally, as to, base on,know as, indicate1.George Washington, the first President of the United States, is _______ the Fatherof His Country.2.The movie we are going to see is said to be _______ the life story of an Americangeneral.3.The doctor’s report _______ that her death was due to heart disease.4.My native town, which was _______ rather small, has now been built into one ofthe biggest cities in the province.5.The speaker said something about the actors first and then _______ to talk aboutthe film.Translations6.几天前,由三位医生和两名护士组成的医疗队出发到山区去了。

7.他病了一个月左右,这使他在学习上耽误了很多。

ⅡKeys1.known as2.based on3.indicated4.originally5.proceeded6.The medical team, composed of three doctors and two nurses set off for themountain area a few days ago.7.He was ill for about a week, which has really set him back in his studies.Unit Two The Dinner PartyⅠExercisesDirection: Fill in the blanks with the words or expressions given below.widen, emerge, make for, impulse, unexpected,at the sight of, outgrow1.New problems _______ when old ones are solved.2.At the first light of dawn the warships _______ the open sea.3.The attack on Perl Harbor on December 7, 1941 was a(n) _______ event whichbrought American into World War Ⅱ.4.The coat fits the boy perfectly now, but he will _______ it in a year’s time.5.Johnny’s mouth watered _______ the big pudding.Translations6.出席晚宴的客人对那个美国人威严的语气感到有点意外。

写国庆的英语作文带翻译National Day is one of the most important holidays in China. It is celebrated on October 1st every year to commemorate the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949. On this day, people all over the country come together to celebrate with various activities and events.国庆节是中国最重要的节日之一。

它每年的10月1日庆祝,以纪念1949年中华人民共和国的成立。

在这一天,全国各地的人们聚集在一起,通过各种活动和事件来庆祝。

The day usually starts with a grand flag-raising ceremony in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. Thousands of people gather to watch the national flag being raised, and the national anthem being sung. It is a very patriotic and moving moment for everyone present.这一天通常以在北京的天安门广场举行盛大的升旗仪式开始。

成千上万的人聚集在一起观看国旗的升起和国歌的奏唱。

对于在场的每个人来说,这是一个非常爱国和感人的时刻。

After the flag-raising ceremony, there is usually alarge parade featuring military personnel, vehicles, and weaponry. It is a display of the country's militarystrength and a way to honor the men and women who serve in the armed forces.升旗仪式之后,通常会有一场大型的阅兵式,其中有军事人员、车辆和武器。

依法治校进程中我国高校学生事务管理的路径——基于美国经验的分析视角摘要:学生事务管理工作作为高校管理的一个重要组成部分,对高校培养什么人、如何培养人具有不可替代的保障和支撑作用。

研究依法治校进程中的学生事务管理,是高校在如今科学发展日新月异、社会发展加速转型、学生群体急剧变化的背景下,面对原有理念、体系、结构、模式与现实的诸多不适应和与学生发展需求的不相符,通过管理转型,产生管理创新,从而有效提高管理绩效、实现教育目的不可或缺的重要环节。

关键词:依法治校;高等教育管理;学生事务依法治校的实质对学校管理者的法制意识提出了更高的要求。

构建高校和谐校园是高校当前的一项重要课题,因此必须加强和完善依法治校的措施。

在西方发达国家,高校学生事务管理与我国沿用至今的“高校学生工作”相对应,已逐步规范化、制度化和专业化。

国外高校学生事务管理体制和运行机制都较为成熟,具有专门化的组织机构和职业化的管理人员。

本文以美国高校学生事务管理的发展历程为视角,通过分析我国目前高校学生事务管理中的不足,借鉴美国高校学生事务管理经验,构建与设计我国高校学生事务管理的新框架。

一、美国高校学生事务管理的理念与发展历程学生事务(Student Affairs),是一个20世纪早期在高等教育中出现的、被称为“学生人事”或“学生工作”(Student Personnel)的新领域。

亚当·勒罗伊·琼斯在载于《有影响的学院》的《人事技巧》一文中解释说,“学生人事”主要致力于解决大学生的一系列问题,使他们调整自己以适应大学的生活和工作而制定的规定,关注学生的健康、经济需要、治理发展、道德和宗教生活。

他认为,这些问题以前由教师管理,但随着大学的发展,这些问题变得更加复杂,需要专家的帮助。

1.美国高校学生事务的雏形(1900-1949年)1937年美国教育委员会(American Council on Education)委任的研究小组经过数年的研究形成了《学生人事纲领》(Student Personnel Point of View)这一具有里程碑意义的报告。

美国大学一年级学生事务管理管窥与启示作者:谭超闻继威俞滨李萌来源:《亚太教育》2016年第30期作者简介:谭超(1977—),女,汉族,江西安福人,讲师,硕士,浙江大学地球科学学院,主要从事大学生事务管理和学生思想政治教育研究。

闻继威(1964—),男,汉族,浙江台州人,副教授,博士,浙江大学地球科学学院,主要从事大学生事务管理和学生思想政治教育研究。

俞滨(1987—),女,汉族,浙江新昌人,硕士,浙江大学化学系,主要从事大学生事务管理和高校校园文化研究。

李萌(1988—),女,汉族,山东青岛,硕士,浙江大学求是学院,主要从事大类招生大类培养中一年级学生事务管理研究。

摘要:本文试图从介绍分析美国大学生一年级学生事务管理的历史发展和目前现状,列举哈佛大学、斯坦福大学等一流大学的一年级学生事务管理实例,重点分析了美国相关经验对我国实施大类招生大类培养政策的大学的一年级学生事务管理的启示。

关键词:美国;大学一年级;学生事务管理;启示中图分类号:G623.2文献标志码:A文章编号:2095-9214(2016)10-0216-03美国大学普遍重视对一年级大学生的教育和管理,这是一年级大学生教育的基础性和战略性地位决定的。

由于美国的大学实行全开放式的招生入学政策,学分制实施得很彻底,如大学之间互认学分,学生有很大的自权利决定是否留在本校继续学习还是转学或退学。

在美国教育史上,学习是大学生的中心任务,也是大学教育的中心所在,这是一个普遍共识。

而关于学生事务管理及管理者对学习的促进作用越来越受到学生事务管理研究的重视和青睐。

一、美国大学一年级学生事务管理的管窥一年级大学生的保留率是美国大学之间竞争中非常重要的一个数据,也是一年级学生事务管理的导向标。

以下是二十世纪八九十年代美国针对大一新生的一些调研数据:入学的时候就打定主意要修什么专业的学生,仅有不到10%的学生知道他们欲将学修的专业情况,即90%的学生并不了解专业。

新世纪研究生公共英语教材阅读A翻译及答案Unit 1 ............................................................................................................................ 错误!未定义书签。

Unit 2 ............................................................................................................................ 错误!未定义书签。

Unit 3 ............................................................................................................................ 错误!未定义书签。

Unit 4 ............................................................................................................................ 错误!未定义书签。

Unit 5 ............................................................................................................................ 错误!未定义书签。

Unit 6 ............................................................................................................................ 错误!未定义书签。

美国大学生事务管理的特点裴学梅;胡叶青【摘要】从美国大学生事务管理历史发展、结构模式、主要职责、目的以及专业化发展等方面,介绍和分析美国学生事务管理工作的法制化和规范化、系统化和专业化、人性化和自主化等特点,指出学生事务管理工作的主要职责是以学生的全面发展为最终目的,促进学生的学习和发展,提高学生的管理工作效能,强化服务意识.【期刊名称】《高校辅导员学刊》【年(卷),期】2011(003)002【总页数】3页(P93-95)【关键词】美国大学生;事务管理;结构模式【作者】裴学梅;胡叶青【作者单位】安徽师范大学外国语学院,安徽芜湖,241003;安徽师范大学外国语学院,安徽芜湖,241003【正文语种】中文【中图分类】G641美国在校大学生的全部活动基本分为两类:学术事务和学生事务。

学术事务涉及学生学习、课程、课堂及认知发展等,而学生事务则涉及学术指导和后勤服务,如课外活动、食宿、学习资源、各种咨询。

[1]美国高等教育的成功离不开高效的学生事务管理工作系统。

一、法治化和规范化18至19世纪初的殖民时期,美国高等教育基本沿袭英国传统的牛津剑桥办学模式,即所谓的“替代父母制” (In Loco Parentis) ,教学任务为宗教教育,学生管理模式为严格监督学生,学生事务和学术事务融为一体。

这一阶段是学生事务管理工作的雏形期。

20世纪后出现的“学生人事工作”(Student Personnel Work)和“学生服务”(Student Services),分离了学术事务和学生事务,标志着学生事务管理工作的形成和发展。

20世纪中期后,“学生发展”(Student Development)有机结合了学生事务与学术事务,并将重点落实在“学生学习”上, 这意味着学生事务管理工作日趋成熟。

[2]美国教育委员会(ACE)在1937年和1949年发布了学生事务纲领性文献《学生人事工作宣言》(The Student Personnel Point of View),在随后的70年里,大学生事务管理领域不断发表、出版了诸多文献和报告, 充分展现了美国高等教育的核心价值,且从学生事务管理的发展阶段、目标、职责及专业化发展等角度指明了高等教育的主要责任,即接纳与欣赏学生的差异,满足学生集体和个体的需求,帮助其发展所有潜能,为社会培养‘全人’ (the whole person)。

英语国家概况(1)课程第2次形成性考核答案和讲评英语国家概况(1)课程形成性考核题英语国家概况(1)课程第2次形成性考核答案和讲评(Unit 06-10)The United Kingdom (II)I. T rue or False:Unit 6 British Literature(T) 01. The early British literature was concerned with Christianity, and Anglo-Saxons produced many versions of the Bible. (Unit 6)(F) 02. There was a general flowering of culture and intellectual life in Europe during the 17th and18th century which is known as “The Renaissance”. (Unit 6) There was a general flowering of culture and intellectual life in Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries which is known as “The Renaissance”. (T)(T) 03. Keats, Shelley and Byron brought the Romantic Movement to its height. (Unit 6)(T) 04. Robinson Crusoe tells the story of a shipwreck and a solitary survival. (Unit 6)(F) 05. Writers of romantic literature are more concerned with the power of reason than withimagination and feeling. (Unit 6)Writers of romantic literature are more concerned with imagination and feeling than with the power of reason. (T)(F) 06. Thomas Hardy, t he author of Tess of the D’Urbervilles, was a first-class novelist but asecond-class poet. (Unit 6)Thomas Hardy, the author of Tess of the D’Urbervilles, wasnot only a first-classnovelist but also a first-class poet. (T)Unit 7 British Education System(F) 07. The purpose of British education is to provide children with literacy and the other basicskills. (Unit 7)The purpose of British education is not only to provide children with literacy and the other basic skills but also to socialize the children. (T)(T) 08. The 1944 Education Act made entry to secondary schools and universities “meritocratic”.(Unit 7)(F) 09. British universities are mainly private bodies which collect funds by themselves. (Unit 7)British universities are mainly public bodies which receive funds from the central government. (T)(T) 10. In Oxford and Cambridge, the BA converts to an MA several years later, upon payment ofa fee. (Unit 7)(F) 11. Grammar schools in Britain select children at the age of 11 and provide them with alanguage education. (Unit 7)Grammar schools in Britain select children at the age of 11 and provide them with a general education. (T)(T) 12. Comprehensive schools admit children without reference to their academic abilities. (Unit7)Unit 8 British Foreign Relations(F) 13. When the Second World ended, Britain no longer was the largest military power in WesternEurope. (Unit 8)When the Second World ended, Britain was the largest military power in Western Europe.(T)(F) 14. According to Unit 8, the most single important factor which influences Britishcontemporary foreign policy is its history. (Unit 8)According to Unit 8, the contemporary foreign policy of the UK is greatly influenced by its imperial history and also by its geographical traits. (T)(T) 15. The Prime Minister and Cabinet decide on the general direction of Britain’s foreign policy.(Unit 8)(F) 16. Britain is a parliamentary monarch. (Unit 8)Britain is a parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarch. (T)(T) 17. Britain hosts a large military American presence and there are some American military bases in the UK. (Unit 8)(F) 18. Britain is not a member of the NA TO due to its disagreement with some Europeancountries on defence policy. (Unit 8)Britain is a member of the NA TO despite its disagreement with some European countries on defence policy. (T)Unit 9 The British Media(T) 19. On an average day, an overwhelming majority of Britons over the age 15 read a national or local paper. (Unit 9)(F) 20. The British media play an important role in shaping a national education. (Unit 9)The British media play an important role in shaping a national culture. (T)(T) 21. Free press has the function of keeping an eye on the government, and therefore it is called the watchdog of parliamentary democracy. (Unit 9)(F) 22. The tabloids are larger format newspapers with colour photos and catchy headlines. (Unit9)The tabloids are smaller format newspapers with colour photos and catchy headlines. (T) (T) 23. The British Broadcasting Corporation is funded by licence fees and viewers must buy a licence each year for their TV set. (Unit 9)(F) 24. The BBC World Service, the international branch of the BBC, broadcasts in English and 24other languages throughout the world. (Unit 9)The BBC World Service, the international branch of the BBC, broadcasts in English and42 other languages throughout the world. (T)Unit 10 Sports, Holidays and Festival in Britain(F) 25. The tradition of having Sunday off derived from the Buddhism. (Unit 10)The tradition of having Sunday off derived from the Christian Church. (T)(F) 26. The origin of Bowling lies in the victory celebration ceremony by the modern soldiers.(Unit 10)The origin of Bowling lies in the victory celebration ceremony by the ancient warriors. (T) (F) 27. The game of Golf was invented by the Irish. (Unit 10)The game of Golf was invented by the Scottish. (T)(T) 28. The extremist animal-lovers’ group wou ld like to have horse-racing banned. (Unit 10) (T) 29. Christmas Pantomimeis one of the three Christmas traditions that are particularly British.(Unit 10)(T) 30. In Ireland, New Y ear’s Eve called Hogmanay (December 31st) is the major winter celebration. (Unit 10) II. Choose the best answer:Unit 6 British Literature01. Which of the following books is written by Geoffrey Chaucer? (Unit 6) Key AA. The Canterbury Tales.B. Beowulf.C. King Lear.D. Le Morte D’Arthur.02. Which literary form flourished in Elizabethan age more than any other form of literature?(Unit 6) Key CA. Novel.B. Essay.C. Drama.D. Poetry.03. Which of the following did NOT belong to Romanticism? (Unit 6) Key DA. Keats.B. Shelley.C. Wordsworth.D. Defoe.04. Which of the following is a tragedy written by Shakespeare? (Unit 6) Key BA. Dr. FaustusB. Macbeth.C. Frankenstein.D. The Tempest.05. Which of the following writers was NOT associated with Modernism? (Unit 6) Key CA. D. H. Lawrence.B. E. M. Foster.C. Charles Dickens.D. V irginal Woolf.06. Which of the following writers wrote the book “1984” that began “Postmodernism” in Britishliterature”? (Unit 6) Key AA. George Orwell.B. Robert L. Stevenson.C. D. H. Lawrence.D. V irginia Woolf.Unit 7 British Education System07. In Britain, the great majority of parents send their children to ______. (Unit 7) Key CA. private schoolsB. independent schoolsC. state schoolsD. public schools08. In Britain, children from the age 5 to 16 ______. (Unit 7) Key BA. can legally receive partly free educationB. can legally receive completely free educationC. can not receive free education at allD. can not receive free education if their parents are rich09. Which of the following is a privately funded university in Britain? (Unit 7) Key DA. The University of Cambridge.B. The University of Oxford.C. The University of Edinburgh.D. The University of Buckingham.10. Which of the following is NOT a characteristic of the Open University? (Unit 7)Key CA. It’s open to everybody.B. It requires no formal educational qualifications.C. No university degree is awarded.D. University courses are followed through TV, radio, email and internet, etc.11. In the examination called “the 11 plus”, students with academic potential go to ______. (Unit7) Key AA. grammar schoolsB. comprehensive schoolsC. public schoolsD. technical schools12. Which of the following is NOT true about the British education system? (Unit 7) Key DA. It’s run by the state.B. It’s funded by the state.C. It’s supervised by the state.D. It’s dominated by the state.Unit 8 British Foreign Relations13. Britain had a big influence on the post-World War II international order because ______.(Unit 8) Key BA. it used to be a great imperial powerB. it used to be a great imperial powerC. it defeated Hitler’s armyD. it got support from its former colonies.14. Which countries are the permanent members of the UN Security Council? (Unit 8) Key CA. France, China, Germany, Russia and Britain.B. The United States, France, Britain, Germany and Russia.C. China, Russia, France, Britain and the United States.D. Britain, China, France, the United States and Japan.15. How much of the globe did Great Britain rule in its imperial prime? (Unit 8) Key BA. One fourth of the globe.B. One fifth of the globe.C. One third of the globe.D. Two thirds of the globe.16. Which of the following is not involved in making British foreign policy? (Unit 8) Key AA. The Queen of the UK.B. The Foreign Commonwealth Office.C. The Prime Minister.D. The Cabinet.17. Which of the following countries does not have nuclear weapon capabilities? (Unit 8)Key CA. BritainB. The United StatesC. GermanyD. France.18. The Commonwealth is an organization of ______ that were once part of the British Empire.(Unit 8) Key BA. about 40 countriesB. about 50 countriesC. about 60 countriesD. about 70 countriesUnit 9 The British Media19. Which of the following is the world’s oldest national newspaper? (Unit 9)Key CA. The Times.B. The Guardian.C. The Observer.D. The Financial Times.20. Which of the following is the British oldest daily newspaper? (Unit 9) Key DA. The Telegraph.B. The News of the World.C. The Guardian.D. The Times21. A free press is considered very important to the functioning of parliamentary democracybecause ______. (Unit 9) Key AA. it plays a watchdog function, keeping an eye on the governmentB. it informs people to current affairs in the worldC. it provides people with subjective reportsD. it publishes short pamphlets for Parliament22. How many newspapers are there in Br itain? (Unit 9) Key DA. About 100.B. About 140.C. About 150.D. About 150.23. Which of the following about the BBC is NOT true? (Unit9) Key CA. There is no advertising on any of the BBC programmes.B. The BBC is funded by licence fee paid by people who possess television sets.C. The BBC has four channels.D. The BBC provides the World Service throughout the world.24. Which of the following newspapers is a tabloid? (Unit 9) Key AA. The News of the World.B. East Enders.C. The Telegraph.D. The Guardian.Unit 10 Sports, Holidays and Festival in Britain25. Which of the following was NOT invented in Britain? (Unit10) Key CA. Football.B. Tennis.C. Basketball.D. Cricket.26. Where is the International tennis championships held? (Unit 10) Key BA. Wembley.B. Wimbledon.C. London.D. Edinburgh.27. Which of the following is truly a sport of the royal family? (Unit 10) Key DA. Cricket.B. Skiing.C. GolfingD. Horse racing.28. Easter commemorates ______. (Unit 10) Key CA. the birth of Jesus ChristB. the Crucifixion of Jesus ChristC. the Crucifixion and Resurrection of Jesus ChristD. the coming of spring29. Which celebration particularly happens on the Queen’s birthday? (Unit 10) Key CA. Bonfires.B. The Orange March.C. Trooping the Colour.D. Masquerades.30. On which day is Halloween celebrated? (Unit 10) Key AA. October 31st.B. November 5th.C. March 17th.D. December 25th.III. E xplain the following terms:Unit 6 British Literature61. The Renaissance (Unit 6)The Renaissance is the period of time in Europe between 14th and 17th centuries, when art, literature, philosophy, and scientific ideas became very important and a lot of new art etc. was produced.62. Romanticism (Unit 6)Roughly the first third of the 19th century makes up English literature’s romantic period. Writers of romantic literature are more concerned with imagination and feeling than with the power of reason. A volume of poems called Lyrical Ballads writtenby William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge is regarded as the romantic poetry’s “Declaration of Independence”. Keats, Byron and Shelley, the three great poets, brought the Romantic Movement to its height. The spirit of Romanticism also occurred in the novel.63. Modernism (Unit 6)Modernism refers to a form of literature mainly written before World War II. It is characterised by a high degree of experimentation. It can be seen s a reaction against the 19th century forms of Realism. Modernist writers express the difficulty they see in understanding and communicating how the world works. Often, Modernism writing seems disorganized, hard to understand. It often portrays the action from the viewpoint of a single confused individual, rather than from the viewpoint of an all-knowing impersonal narrator outside the action. One of the most famous English Modernist writers is V irginia Woolf.Unit 7 British Education System64. Independent schools (Unit 7)Independent schools are commonly called public schools which are actually private schools receive their funding through the private sector and tuition rates, with some government assistance. Independent schools are not part of national education system, but quality of instruction and standards are maintained through visits from Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Schools. These schools are restricted to the students whose parents are comparatively rich.65. The Open University (Unit 7)The Open University was founded in Britain in the 1960’s for people who might not get the opportunity for higher education for economic and social reasons. It’s open toeverybody and does not demand the same educational qualifications as the other universities. University courses are followed through TV, radio, videos and a net work of study centres. At the end of their studies at the Open University, successful students are awarded a university degree.Unit 8 British Foreign Relations66. The foundation of British foreign policy (Unit 8)The contemporary foreign policy of the UK is greatly influenced by its imperial history and also by its geographical traits. As Britain lost its empire recently, British policy-makers frequently forget that Britain is not as influential as it used to be in world affairs. Another decisive influenceupon the way Britain handles its external affairs is geopolitical attitude to Europe.67. Britain and the EU (Unit 8)Britain joined the European Community in 1973 which is now called the EU. Britain’s participation in the EU remains controversial. At the centre of the controversy is the fact that it is not clear about what the EU is and what it will become. The UK has always been interested in encouraging free trade between countries and is therefore very supportive of the EU as a free trade area. Britain likes to regard the EU as a place where economic cooperation is possible and where a flow of trained personnel and goods are possible. But Britain has always been less enthusiastic about giving up its national sovereignty to the EU.68. Britain and the United States (Unit 8)The British foreign policy is also affected by its relationship with the United States. During World War II, the two countries were closely allied and continued to work together closely in thepostwar years, because they had many things in common about the past and the world situation. Even today, Britain and American policy-makers share the general ideas in many respects. The British are beginning to realize that their own foreign policy action can be limited by the U.S., but both sides worked hard to maintain the “special relationship”.69. The Commonwealth (Unit 8)The Commonwealth is a voluntary association of states which is made up mostly of former British colonies. There are about 50 members of the Commonwealth: many of these are developing countries like India and Cyprus; others are developed countries like Australia, Canada and New Zealand. The Commonwealth was set up a forum for continued cooperation and as a sort of support network.Unit 9 The British Media70. Quality papers (Unit 9)The quality papers belong to one of the categories of the national dailies. They carry more serious and in-depth articles of particular political and social importance. They also carry reviews, such as book reviews, and feature articles about high culture. These papers are also referred to as “the broadsheets” because they are printed on lar ge size paper. The readers of such newspapers are generally a well-educated middle class audience.71. Tabloids (Unit 9)A tabloid is a small format newspaper with colour photos and catchy headlines. T abloids are interested in scandals and gossip usually about famous people. They also carry lots of crime, sports and sensational human interest stories so as to attract readers. Stories are short, easy to read and often rely more on opinions than fact. They belong to a catalogue of national papers differentfrom quality papers.Unit 10 Sports, Holidays and Festival in Britain72. Cricket and “fair play” (Unit 10)Cricket was one of the very first team sports in Britain to have organised rules and to be played according to the same rules nationally. The reason that fixed rules were applied to cricket so early on was a financial one: aristocrats loved betting on cricket matches and if people were going to risk money on a game, they wanted to ensure that the game would be played fairly. In Britain people from all walks of life play cricket, but in the 19th century, cricket was a sport playedmainly by the upper class. It was a kind of a “snob” game played by boys who attended public schools. As generations of public school boys grew up to become the civil servants and rulers of the UK and its colonies, cricket became associated with a set of moral values, in particular, the idea of “fair play” which supposedly characterised British government.73. Wimbledon (Unit 10)Wimbledon is the name of a London suburb. In Wimbledon, the world’s best players gather to compete on grass courts. It is one of the major events of the British sporting calendar and probably the most famous tennis event in the world. Besides actually watching the tennis matches, other activities clo sely associated with the “Wimbledon fortnight” are eating strawberries and cream, drinking champagne and hoping that it doesn’t rain.。

2002年3月第6卷第1期扬州大学学报(高教研究版)J ournal of Yangzhou Uni versity(Higher Education Study Edition)Mar12002Vol16No11美国高校学生事务管理专业化的发展及其特征蔡国春(南京师范大学教育科学学院,江苏南京210097)摘要:美国高校学生事务管理先后在/替代父母制0、/学生人事工作0、/学生服务0和/学生发展0理论影响下,在20世纪完成了专业化的历程。

学生事务管理专业化,以学生事务及其管理在高等教育中具有相对独立的地位、专门设置的机构、职业化的工作岗位和专业化的管理人员等为标志特征。

学生事务和学术事务紧密联系共同致力于/学生学习0,是美国高校学生事务管理发展的新动向。

关键词:美国高等教育;学生事务管理;学生发展;学生服务中图分类号:G6491712文献标识码:A文章编号:1007-8606(2002)01-0073-041899年美国芝加哥大学的校长哈珀(Ha rper)致信布朗大学,信中第一次提出/对学生的科学研究0的说法,并断言它/将会成为美国大学工作的不可分割的一部分0[1](p.195)。

以此为起点,美国高校学生事务管理先后经历了学生人事工作(stude nt pe rsonnel work)、学生服务(student se rvices)、学生发展(student development)等多种模式,终于实现了专业化。

一、历史渊源与专业化的发轫学生事务及其管理是相对于教学和学术性事务及其管理而言的,它是指学生课外活动或非学术性事务及其管理。

在早期,美国的高等学校对学生事务和学术事务是不加区分的,现今所说的学生事务及其管理从无到有经历了200多年的漫长历程。

在此之前,高校对学生及其校园生活实行的是严格的寄宿制、道德监督和行为控制,沿用的仍然是/替代父母制0(in loco pare ntis)的管理模式。