PET5 英语教程 Unit1 education

- 格式:doc

- 大小:140.00 KB

- 文档页数:9

北师大版(2019)选择性必修二Unit 5 EducationLesson 1 Enlightening a Mind 教学设计一、整体设计思路1. 《普通高中英语课程标准》(2017年版2020年修订)将高中英语核心素养凝练为语言能力、文化品格、思维品质和学习能力。

在日堂教学中分阶段、分层次、有侧重地培养学生的英语核心素养。

本节课定位于高二学年第一学期,学生通过参与对教材第五单元第一课教育·启迪心灵(海伦·凯勒接受教育的故事)作基于文本、深入文本和超越文本的阅读理解过程,实现从理解过渡到应用,最终达成迁移。

2. 内容分析本节课所使用的文本来自新北师大版选择性必修二第五单元第一课,主要是介绍海伦·凯勒如何从安娜·莎莉文老师那里学习知识的故事,文章中词汇虽一定的难度,但不影响学生理解,语篇结构和段落结构清晰。

通过文本解读,我们发现语篇表面上是对海伦·凯勒学习方式的介绍,但是深层次的发现是对其学习态度,学习动力,以及教育对一个人所产生的重大影响。

而这些暗含在文段背后的深层内涵非常有利于培养学生的思维品质。

3. 过程分析本节课采用语篇模式分析,分四个方面(结构、细节、情感、主题)对文本进行全面解读。

课堂设计按照“导入-读结构-读细节-读情感-思主题”的步骤进行,最后,通过在单元主题意义下的升华来让学生思考并迁移课堂内容。

(1) 通过作品《假如给我三天光明》的图片导入,自然而然引出文本的主人公海伦·凯勒,引发学生思考“是谁对海伦·凯勒的巨大成就做出了突出的贡献?”激活学生对文本主人公已有的相关知识。

(2) 要求学生浏览全文,理清文章的思路及结构,以及各部分的主旨大意,掌握获取主旨大意的能力。

(3) 通过语篇模式分析,从细节和情感两个维度对文章3-11段的内容进行全面解读,掌握字面意义和隐含意义,获取细节理解的能力。

(4) 在对文章的结构、细节、情感分析的基础上,通过单元主题的介绍,引导学生基于文本提出一些与单元主题和文本话题两者相结合的一些问题。

Unit 5 EducationLesson 1 Enlightening a Mind 教学设计科目:英语课题:Lesson 1 Enlightening a Mind 课时:1课时教学目标与核心素养:知识目标:Students can learn some new words and expressions and present participle.能力目标:Students can have a further understanding of the passage.情感目标:Students can think individually and learn cooperatively.教学重难点教学重点:How to learn the new words and expressions and present participle.教学难点:How to make students have a better understanding of the passage.课前准备:多媒体,黑板,粉笔教学过程:一、Pre-reading1. Greeting2. Leading-inACTIV ATE AND SHARE教师活动:(1) 学生活动。

Think of some possible ways to teach someone who is blind to read and write. Then think of ways to teach someone who is both blind and deaf to read and write.二、While- readingREAD AND EXPLORE1. 学生活动:Pair WorkRead paragraphs 1-2 of the story. Discuss Helen Keller and her teacher's characteristics and personalities.(Helen was frustrated, stubborn and troublesome. She got angry easily when she was not understood.Anne was a superb teacher who could understand Helen's difficulties. She was sympathetic.)2. 学生活动:阅读文章,回答问题。

小学英语pep第五册第一单元教学设计英文版Unit 1 My New TeachersTeaching objectives of the whole unit:1 Ability Objectives(1) Learn how to describe teacher’s appearance and character, eg: We have a new English teacher. He’s tall and strong. He is very funny.(2) Finish ”Let’s try”.(3) Sing the song “My New Teacher”.2 Knowledge Objectives(1) Understand the dialogue in Read and Write.(2) Learn the new words and sentences in Let’s Learn and Read and Write.3 Emotion, tactics, culture objectives(1) Emotion manner: foster the students’ability to study on their own.(2) Study Tactics: foster the students’manner and method to cooperate with each other when studying.(3) Culture: find out the difference of calling names between China and the western country.Unit One My New Teachers教学内容Let’s start Main scene A Let’s learn Let’s find out C Let’s sing课时1教学目标1 Ss Can understand the sentences: Who’s your new teacher? What’s he like?2 Learn the new words: old short thin tall strong3 Finish Let’s Find Out.4 Ss can sing the song My New Teacher.教学重、难点1 All the words in Let’s Learn.2 The difficult point is Let’s Start.T can draw the new dialogue through Let’s Start.教具1 Teaching pictures and new word cards2 Figure picture3 The photos of the teachers and school4 The radio and tape教学过程1 Warm-up(1) Broadcast Let’s Start. Let the Ss guess the topic of this unit.Learn to sing the song My New Teacher.T: Hi, everyone. Nice to see you again. What grade are you in now?Ss: We’re in Grade 5.T: Do you like your new English books?Ss: Yes!T: What are we going to talk about in Unit 1? Guess! What’s the topic of Unit 1?(2) Practice the oral English.Broadcast the Let’s Chant, Let’s sing, Let’s do that the Ss had already learned. 2 Preview Review the words: strong tall short thin3 PresentationLet’s start and Let’s learn(1) Present the teaching picture of Let’s learn. The T describe the picture and let the Ss guess who is the new T.(2) Present the hanging picture of Let’slearnT: They are Sarah’s teachers (describe these teachers). Get the Ss review the words: strong tall short thin. And then present the new words: young kind old funny(3) Read the new words.(4) Listen to the radio and read the words after the radio.Teach the students how to write the words Finish Let’s Find Out.Sing the song My New Teacher.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do the work book: A Let’s learn(2) Read Let’s Learn to your friends and parents.Sing the songBlackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersYoung funny tall strong Who’s your art teacher/?Kind old short thin Mr Hu.What’s he like? He’s short and thin.教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容A Let’s try Let’s talk C Good to know课时2教学目标1 Ss can understand and say: Who’s your math teacher? Mr Zhao. What’s he like? He’s thin and short. He’s very kind. And Ss can replace the key words to make new sentences and use the sentence in true situation.2 Do Let’s Try3 Get to know the difference that how tocall names between China and the western country.教学重、难点1 The new sentence: Who’s your math teacher? Mr Zhao. What’s he like? He’s thin and short. He’s very kind.2 Let’s try教具1 the hanging pictures2 the figure pictures3 some photos and pictures of the teachers4 radio and tape教学过程1 Warn-up(1) Sing the song My New Teacher(2) Practice oral English2 PreviewReplace the key words in the sentence and review the new words that they learned last period.3 PresentationLet’s tryBroadcast Let’s try, get the Ss finish the exercise. Get the students listen to the voice of their familiar teachers and guess who they are.Learn the dialogue in Let’s talk.Let’s talk(1) Present the figure pictures. Let the Ss remember them quickly. And then get Ss to recall which subject they teach.(2) Listen to the radio and read after the tape. Get the Ss to replace the key words and make sentences. We can do the group works.(3) Let the Ss make figure cards anddescribe the figures using the sentences: Who’s this man\woman? What’s he\she like?Good to knowLet the Ss find out the differences of calling names between China and the western countries.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do A Let’s talk in work book.(2) Listen to the dialogue in Let’s talk and read them to your friends and parents.(3) Describe some photos with your partner.Blackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersWho’s your math teacher?Mr Zhao.What’s he like?He’s thin and short . He’s very kind.教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容A Read and write Pair work C Pronunciation课时3教学目标1 Understand the dialogues and use the dialogues in the situation.2 Learn the sentences: Who’s your English teacher? Mr Carter. What’s he like? He’s tall and strong.3 Understand the pronunciation rules of the letters ”ea, ee, br”.教学重、难点1 Learn the sentences and use them in the situation.2 Pronunciation.教具1 the teaching pictures2 the figure pictures3 some photos4 radio and tapes5 word cards and figure cards教学过程Warn-up(1) Show out different teachers’ pictures and let the Ss guess who they are.(2) Practice the oral English.2 PreviewSpell the words using the word cards3 PresentationRead and write(1) Tell a story: Zhang Peng has three new teachers this term. Let’s go and have a look!Who are they?(2) Read the dialogue in pairs and find out the difficult points(3) Raise some questions and let the Ss answer the questions and fill in the blanks(4) Teach the Ss how to write the sentences.Pair workDescribe the figures using the word cards.Pronunciation(1) Guide the Ss to find out the pronunciation rules of the letters “ea, ee”.(2) Listen to the tape and read the rhyme.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do work book: Read and write.(2) Listen to the tape of Read and write, Pronunciation.Blackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersWho’s that man?He’s our math teacher.What’s he like?He’s tall and strong. .教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容Let’s chant and B Let’s learn Let’s chant C Story timeUnit 1 My New TeachersTeaching objectives of the whole unit:1 Ability Objectives(1) Learn how to describe teacher’s appearance and character, eg: We have a newEnglish teacher. He’s tall and strong. He is very funny.(2) Finish ”Let’s try”.(3) Sing the song “My New Teacher”.2 Knowledge Objectives(1) Understand the dialogue in Read and Write.(2) Learn the new words and sentences in Let’s Learn and Read and Write.3 Emotion, tactics, culture objectives(1) Emotion manner: foster the students’ability to study on their own.(2) Study Tactics: foster the students’manner and method to cooperate with each other when studying.(3) Culture: find out the difference of calling names between China and the western country.Unit One My New Teachers教学内容Let’s start Main scene A Let’s learn Let’s find out C Let’s sing课时1教学目标1 Ss Can understand the sentences: Who’s your new teacher? What’s he like?2 Learn the new words: old short thin tall strong3 Finish Let’s Find Out.4 Ss can sing the song My New Teacher.教学重、难点1 All the words in Let’s Learn.2 The difficult point is Let’s Start.T can draw the new dialogue through Let’s Start.教具1 Teaching pictures and new word cards2 Figure picture3 The photos of the teachers and school4 The radio and tape教学过程1 Warm-up(1) Broadcast Let’s Start. Let the Ss guess the topic of this unit.Learn to sing the song My New Teacher.T: Hi, everyone. Nice to see you again. What grade are you in now?Ss: We’re in Grade 5.T: Do you like your new English books?Ss: Yes!T: What are we going to talk about in Unit 1? Guess! What’s the topic of Unit 1?(2) Practice the oral English.Broadcast the Let’s Chant, Let’s sing, Let’s do that the Ss had already learned. 2 Preview Review the words: strong tall short thin3 PresentationLet’s start and Let’s learn(1) Present the teaching picture of Let’s learn. The T describe the picture and let the Ss guess who is the new T.(2) Present the hanging picture of Let’s learnT: They are Sarah’s teachers (describe these teachers). Get the Ss review the words: strong tall short thin. And then present the new words: young kind old funny(3) Read the new words.(4) Listen to the radio and read the words after the radio.Teach the students how to write the wordsFinish Let’s Find Out.Sing the song My New Teacher.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do the work book: A Let’s learn(2) Read Let’s Learn to your friends and parents.Sing the songBlackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersYoung funny tall strong Who’s your art teacher/?Kind old short thin Mr Hu.What’s he like? He’s short and thin.教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容A Let’s try Let’s talk C Good to know课时2教学目标1 Ss can understand and say: Who’s your math teacher? Mr Zhao. What’s he like? He’s thin and short. He’s very kind. And Ss can replace the key words to make new sentences and use the sentence in true situation.2 Do Let’s Try3 Get to know the difference that how to call names between China and the western country.教学重、难点1 The new sentence: Who’s your math teacher? Mr Zhao. What’s he like? He’s thin and short. He’s very kind.2 Let’s try教具1 the hanging pictures2 the figure pictures3 some photos and pictures of the teachers4 radio and tape教学过程1 Warn-up(1) Sing the song My New Teacher(2) Practice oral English2 PreviewReplace the key words in the sentence and review the new words that they learned last period.3 PresentationLet’s tryBroadcast Let’s try, get the Ss finish the exercise. Get the students listen to the voice of their familiar teachers and guess who they are.Learn the dialogue in Let’s talk.Let’s talk(1) Present the figure pictures. Let the Ss remember them quickly. And then get Ss to recall which subject they teach.(2) Listen to the radio and read after the tape. Get the Ss to replace the key words and make sentences. We can do the group works.(3) Let the Ss make figure cards and describe the figures using the sentences: Who’s this man\woman? What’s he\she like?Good to knowLet the Ss find out the differences of calling names between China and the western countries.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do A Let’s talk in work book.(2) Listen to the dialogue in Let’s talk and read them to your friends and parents.(3) Describe some photos with your partner.Blackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersWho’s your math teacher?Mr Zhao.What’s he like?He’s thin and short . He’s very kind.教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容A Read and write Pair work C Pronunciation课时3教学目标1 Understand the dialogues and use the dialogues in the situation.2 Learn the sentences: Who’s your Englishteacher? Mr Carter. What’s he like? He’s tall and strong.3 Understand the pronunciation rules of the letters ”ea, ee, br”.教学重、难点1 Learn the sentences and use them in the situation.2 Pronunciation.教具1 the teaching pictures2 the figure pictures3 some photos4 radio and tapes5 word cards and figure cards教学过程Warn-up(1) Show out different teachers’ pictures and let the Ss guess who they are.(2) Practice the oral English.2 PreviewSpell the words using the word cards3 PresentationRead and write(1) Tell a story: Zhang Peng has three new teachers this term. Let’s go and have a look! Who are they?(2) Read the dialogue in pairs and find out the difficult points(3) Raise some questions and let the Ss answer the questions and fill in the blanks(4) Teach the Ss how to write the sentences.Pair workDescribe the figures using the word cards.Pronunciation(1) Guide the Ss to find out the pronunciation rules of the letters “ea, ee”.(2) Listen to the tape and read the rhyme.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do work book: Read and write.(2) Listen to the tape of Read and write, Pronunciation.Blackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersWho’s that man?He’s our math teacher.What’s he like?He’s tall and strong. .教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容Let’s chant and B Let’s learn Let’s chant C Story timeUnit 1 My New TeachersTeaching objectives of the whole unit:1 Ability Objectives(1) Learn how to describe teacher’s appearance and character, eg: We have a new English teacher. He’s tall and strong. He is very funny.(2) Finish ”Let’s try”.(3) Sing the song “My New Teacher”.2 Knowledge Objectives(1) Understand the dialogue in Read and Write.(2) Learn the new words and sentences in Let’s Learn and Read and Write.3 Emotion, tactics, culture objectives(1) Emotion manner: foster the students’ability to study on their own.(2) Study Tactics: foster the students’manner and method to cooperate with each other when studying.(3) Culture: find out the difference of calling names between China and the western country.Unit One My New Teachers教学内容Let’s start Main scene A Let’s learn Let’s find out C Let’s sing课时1教学目标1 Ss Can understand the sentences: Who’s your new teacher? What’s he like?2 Learn the new words: old short thin tall strong3 Finish Let’s Find Out.4 Ss can sing the song My New Teacher.教学重、难点1 All the words in Let’s Learn.2 The difficult point is Let’s Start.T can draw the new dialogue through Let’s Start.教具1 Teaching pictures and new word cards2 Figure picture3 The photos of the teachers and school4 The radio and tape教学过程1 Warm-up(1) Broadcast Let’s Start. Let the Ss guess the topic of this unit.Learn to sing the song My New Teacher.T: Hi, everyone. Nice to see you again. What grade are you in now?Ss: We’re in Grade 5.T: Do you like your new English books?Ss: Yes!T: What are we going to talk about in Unit 1? Guess! What’s the topic of Unit 1?(2) Practice the oral English.Broadcast the Let’s Chant, Let’s sing, Let’s do that the Ss had already learned. 2 Preview Review the words: strong tall short thin3 PresentationLet’s start and Let’s learn(1) Present the teaching picture of Let’s learn. The T describe the picture and let theSs guess who is the new T.(2) Present the hanging picture of Let’s learnT: They are Sarah’s teachers (describe these teachers). Get the Ss review the words: strong tall short thin. And then present the new words: young kind old funny(3) Read the new words.(4) Listen to the radio and read the words after the radio.Teach the students how to write the words Finish Let’s Find Out.Sing the song My New Teacher.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do the work book: A Let’s learn(2) Read Let’s Learn to your friends and parents.Sing the songBlackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersYoung funny tall strong Who’s your art teacher/?Kind old short thin Mr Hu.What’s he like? He’s short and thin.教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容A Let’s try Let’s talk C Good to know课时2教学目标1 Ss can understand and say: Who’s your math teacher? Mr Zhao. What’s he like? He’s thin and short. He’s very kind. And Ss can replace the key words to make new sentences and use the sentence in true situation.2 Do Let’s Try3 Get to know the difference that how to call names between China and the western country.教学重、难点1 The new sentence: Who’s your math teacher? Mr Zhao. What’s he like? He’s thin and short. He’s very kind.2 Let’s try教具1 the hanging pictures2 the figure pictures3 some photos and pictures of the teachers4 radio and tape教学过程1 Warn-up(1) Sing the song My New Teacher(2) Practice oral English2 PreviewReplace the key words in the sentence and review the new words that they learned last period.3 PresentationLet’s tryBroadcast Let’s try, get the Ss finish the exercise. Get the students listen to the voice of their familiar teachers and guess who they are.Learn the dialogue in Let’s talk.Let’s talk(1) Present the figure pictures. Let the Ss remember them quickly. And then get Ss to recall which subject they teach.(2) Listen to the radio and read after the tape. Get the Ss to replace the key words and make sentences. We can do the group works.(3) Let the Ss make figure cards and describe the figures using the sentences: Who’s this man\woman? What’s he\she like?Good to knowLet the Ss find out the differences of calling names between China and the western countries.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do A Let’s talk in work book.(2) Listen to the dialogue in Let’s talk and read them to your friends and parents.(3) Describe some photos with your partner.Blackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersWho’s your math teacher?Mr Zhao.What’s he like?He’s thin and short . He’s very kind.教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容A Read and write Pair work C Pronunciation课时3教学目标1 Understand the dialogues and use the dialogues in the situation.2 Learn the sentences: Who’s your English teacher? Mr Carter. What’s he like? He’s tall and strong.3 Understand the pronunciation rules of the letters ”ea, ee, br”.教学重、难点1 Learn the sentences and use them in the situation.2 Pronunciation.教具1 the teaching pictures2 the figure pictures3 some photos4 radio and tapes5 word cards and figure cards教学过程Warn-up(1) Show out different teachers’ pictures and let the Ss guess who they are.(2) Practice the oral English.2 PreviewSpell the words using the word cards3 PresentationRead and write(1) Tell a story: Zhang Peng has three newteachers this term. Let’s go and have a look! Who are they?(2) Read the dialogue in pairs and find out the difficult points(3) Raise some questions and let the Ss answer the questions and fill in the blanks(4) Teach the Ss how to write the sentences.Pair workDescribe the figures using the word cards.Pronunciation(1) Guide the Ss to find out the pronunciation rules of the letters “ea, ee”.(2) Listen to the tape and read the rhyme.4 Consolidation and extension(1) Do work book: Read and write.(2) Listen to the tape of Read and write, Pronunciation.Blackboard writing:Unit 1 My new teachersWho’s that man?He’s our math teacher.What’s he like?He’s tall and strong. .教学后记Unit 1 My New Teachers教学内容Let’s chant and B Let’s learn Let’s chant C Story time。

教学设计

Scan Para.5

What happened to the pump water?

Scan Para.6

What extra evidence did he find?

Scan Para.7

1. What did he suggest in order to prevent it from happening?

2. What happened finall y? 多,而有了小组的共同参与,个体的阅读压力能减小很多,而且也能让所有小组成员共同参与共同探讨,这本身就是

现;另外,读图能力也是科学能力当中非常重要的一种,因此,在这个过程中,笔者大胆采用了此方法,旨在提高学生的参与感和读图能力。

中文的句子和图片中的绘制相统一,让学生在寻找细节的同时也寻找原因所在,环环相扣,最后结论的给出也显得更加自然和流畅。

七、板书设计。

Unit1 My New Teachers1.Design ConceptAccording to the English Curriculum Standards, the revolution of new curriculum has attached much importance to transiting from the traditional way of paying most attention to grammar and vocabulary teaching to a new w ay of emphasizing students’ comprehensive language application ability. That is to say, English teaching has evolved from the teacher-centered way to the student-centered way, which is characterized in students’ autonomous research. According to the theory of constructivism, language acquisition is not achieved through teachers’ teaching, but naturally happens when students are under a certain circumstance, taking advantage of teachers’ help and necessary materials.On the basis of this concept, inspiring s tudents’ active research will be the main approach of this unit’s teaching. The teacher should at first lead the students to a visual and direct understand ing about the target knowledge by showing pictures and the text. Then some phasic questions and phasic task-based activities should be put forward. Through such a process, the meaning construction and practical application ability will be finally achieved.2.Main Information of the unitThe topic of this unit is “My New Teachers”, which requests students to use some adjectives like strong, thin, tall, short, old, young, funny, strict, etc. to describe the appearance and characteristics of their teachers. With a repeated presentation for sentences like “Who is…?”“What’s he/she like…”“Is he/she…”“He/she is…”, it’s beneficiary for students to remember the main sentence patterns naturally and consolidate their memory again and again. The reasonable layout of from easy to difficult, from simple to complicated also enables students to learn step by step. The transition from input to output is very natural. And the setup of task-based activities such as Pair Work and Group Work is a good way for students to express themselves.New term starts, students will meet some new teachers. This is an interesting and hot topic among students. Students’ passion for this unit will be certainly great.3.Students’ Conditions Before Studying this UnitIn Grade4, in the unit of “My Friends”, the students have already met some words to describe people’s appearance, including strong, thin, short, long, tall, big, small, quiet, cute, etc. They have got a basic impression about describing a person. However, due to the restriction of the learning experience and cogitation for English, these words may not be acquired for use among many students. So it’s advisable for the teacher to review the old materials and gain new knowledge by a further teaching. On the other hand, as Grade-5 students, through years of learning English, they have got some basic knowledge about English and become more curious and interested in English.And students at this age are willing to show themselves while not able to understand conceptual knowledge and form mechanical memory when learning English. Therefore, vivid materials andflexible methods are needed to inspire and keep students’ learning interest and to consolidate the acquired knowledge in various ways.4.Teaching Objectives of the whole Unit4.1Ability ObjectivesA. Students can simply describe the appearance and characteristics of their teachers, e.g. “We havea new English teacher. She is short and thin. She is very kind.”B. Students can ask questions about teachers and introduce their teachers, e.g. “Who's yourEnglish teacher? Mr. Carter.He's from Canada.What's he like? He's tall and strong. He’s very funny.C. Students can listen and understand simple dialogues about describing people’s features, andfinish the exercise in Let’s Try.D. Students can understand and sing the song “My New Teacher”. Furthermore, they can flexiblychange the subject name and adjectives related to people’s features in the lyrics.4.2Knowledge ObjectivesA. Students can understand the dialogues in Read and Write of both Part A and Part B, and fill inthe blanks in the sentences and answer some questions according to the text.B. Students can listen, speak, read and write four-can words (old, young, tall, short,strong, thin,funny, kind) and sentences (Who’s your…? What’s he /she like?) in Let’s Talk and Read and Write of both Part A and Part B, and properly use them in different situations according to their own experiences.C. Students can understand the pronunciation rules of the letter-groups “ea, ee, bl, br”.4.3Emotion ObjectivesA. Cultivate students’ emotions of loving their teachers and respecting their teachers through thediscussion. Help students to build good relations with their teachers.B. According to the features of senior primary students, help them to develop independent studyability, inspire their interests for English learning and improve their self-confidence in English learning4.4Tactics ObjectivesA. Develop students’interest, consciousness and approach for cooperative study by making themost use of Pair work, Group work, Talk and draw and Task time in the text book.B. Improve students’ ability and method of studying on their own.4.5Culture ObjectivesStudents can understand the deference in calling names between China and western countries.5.Keys and Difficulties5.1Key PointsA. Key Words: old, young, tall, short, strong, thin, funny, kindB. Key Sentences: Who’s your…? What’s he/she like? Is he/she… He/she is… Yes, he/she is. No,he/she isn’t.C. Topic: Talk about new teachers in both appearance and characteristics.5.2Difficult Points:Students should replace the key words in a sentence to make newsentences and use different sentences in different situation.6.Teaching ApproachCooperative learning, role-playing, task-based activities, CAI, chanting7.Period Arrangement: 6 periods in total8.Process of the Class8.1Period 1 (Section A: Let’s start, Let’s learn, L et’s find out)A. At first, the short dialogue in Let’s start is broadcast to lead to the topic.B. By doing the task in Let’s start, old words (strong tall short thin) and new words (young kindold funny) are presented for the first time.C. Then by listing, reading and spelling, the words are presented for the students again. InActivity1 “Let’s guess”, new sentence patterns ( Who’s your … teacher? What’s he /she like?) are presented.D. Activity2 “Chanting” is a good way for students to review what has learnt in previous steps in arelaxed atmosphere.E. The interesting Activity 3 “Introduce teachers by rolling a snowball” is really interesting and itfosters students’ ability of innovation and comprehensive language use.F. At last, some homework is assigned to consolidate what has learnt and servers for the nextperiod.Topic New teachersFunction Describe teachers with different adjectivesV ocabulary young, old, kind, funny, strong, thin, tall, shortStructure Who’s your … teacher? What’s he /she like ?Activity Guessing, listing, chanting, speakingGrammar The asking and answering of special questionsTeaching aids Multi-media, radio and tape, some pictures of different teachers8.2Period 2 (Section A: Let’s chant, Let’s try,Let’s talk, Good to know)A. Review the words and sentence patterns by asking questions to several students.B. B roadcast Let’s try, get the Ss finish the exercise.Do activity1 “Let’s guess”to have the students listen to the voice of their familiar teachers and guess who they are. This is a process of input, during which students may improve the ability to listen to native speakers and Chinese teachers.C. Present the figure pictures. Let the Ss remember them quickly. And then get them to recall which subject they teach. Ss shall make figure cards and describe the figures by answering the questions: Who’s this man\woman? What’s he\she like?D. Listen to the radio and read after the tape of the dialogue in Let’s talk. Get the Ss to replace the key words and make sentences with each other.E. Broadcast the song in Section A, and get Ss to chant together for a relaxation and a review for the words.F. Let the Ss find out the differences of calling names between China and the western countries through the learning of Good to know.Topic TeachersFunction Describe teachers by replacing different adjectivesV ocabulary young, old, kind, funny, strong, thin, tall, short, art, science, principal, Mr.Structure Who's your math teacher? Mr. Zhao.What's he like? He's thin and short.He's very kind.Activity Listing, guessing, chanting, speakingGrammar The difference of the position of family name and the given name between China and western countriesTeaching aids Multi-media, radio and tape, hanging pictures, figure pictures8.3Period 3 (Section A: Read and write, Pair work Section C: Pronunciation)A. Practice oral English.B. Spell the words, using the word cards to set up a basis for the next task.C. Tell a story: Zhang Peng has three new teachers this term. Let’s go and have a look! Who are they? Read the dialogue in pairs and find out the difficult points. Raise some questions and let the Ss answer the questions and fill in the blanks.D. Teach the Ss how to write the sentences by analyzing the differences between declarative sentence and interrogative sentence.E. Do the pair work. Describe the figures to each other, using the word cards and replace key words in the sample given in the text book.F. Listen to the tape and read the rhyme. Guide the Ss to find out the pronunciation rulesTopic People’s appearance and featuresFunction Describe people with different adjectives and sentencesV ocabulary young, old, kind, funny, strong, thin, tall, short, art, science, CanadaStructure Who’s that man/ woman? Who’s your …? What’s he/she like? He’s…Activity Practicing, reading, talking, writingGrammar The correct structure of a question. Differences between a declarative sentence and a interrogative sentence.Teaching aids Multi-media, radio and tape, figure picture8.4Period 4(Section B: Let’s learn, Let’s chant, Section C: Story time)A. Broadcast the rhyme in Let’s chant and get the Ss to be familiar with the content and rhythm. Sing the song and guide the Ss to replace the words and read it in front of the class.B. Finish Let’s learn. Show out the photo of our principal: “ Who’s this lady?” Ss: “…”T: She’s our principal. Present the new word: principal. And then describe: She’s strict. Guide the students to describe the characters of other teachers or other people by using new words such as smart, active, funny, strict, etc. Pay attention to the pronunciation of the word: university, strict.C. Read the mew words after the tape and learn to write.D. Story time: Listen to the radio and watch the VCD. Try to get some students to play a role.Topic People’s charactersFunction Describe people’s characters with different adjectivesV ocabulary Strict, principal, kind, university, smart, funny, activeStructure Who’s that young lady? Is she …? Y es, she is … No, she isn’t…Activity Practicing, reading, talking, chantingGrammar The assertive and negative answer to a general questionTeaching aids Multi-media, radio and tape, figure pictures8.5Period 5 (Section B: Let’s try, L et’s talk, Group work Section C Let’s s ing,Let’s checkA. Review the sentence: “ Who’s your principal? Miss Lin. Is she young? No, She’s old. She’s very kind.”Replace the key words and make sentences, using the photos and pictures. Go over the words we learned in the last period.B. Listen to the tape and finish the exercise in Let’s try.C. Watch the VCD and at the same time describe our principal. And then learn the dialogue in Let’s talk. Teach the new words: strict, active, quiet. Show out the teaching pictures and describe one figure. Let the Ss guess who he is. The figures’ respective characters are: smart, kind, and funny. Listen to the radio and read the dialogue. Practice the sentence: Is he\she…? Y es, he\she is. No, he\she isn’t.D. Group work. When the Ss grasp the sentences like “ She’s our teacher. She’s kind. Who’s she? Guess.”, let the Ss use “ Is she young? Is she pretty?” to get more information about the teachers. Let’s guess who the teacher is.E. Broadcast the song “My New Teavhers”, and the whole class sing the song together.F. Let’s check. Listen to the tape and give the right order.Topic People’s charactersFunction Get information about people’s characters by asking general questions.V ocabulary Lady, principal, strict, active, quiet, kind, young, oldStructure Who’s that young lady? Is he\she…? Y es, he\she is. No, he\she isn’t.Activity Practicing, talking, listeningGrammar The structure of a general questionTeaching aids Multi-media, radio and tape, figure picture8.6Period 6 (Section B: Read and write, Talk and draw Section C: Task time)A. Go over the new words, using the word cards. Let the students have a competition of spelling words.B. Show out the pictures and ask the students to describe the teacher in the picture.C. Read and write. Let the students read the dialogue, and find out the words and sentences they don’t understand. Read after the tape and then finish filling the blanks.D. Talk and draw. Practice the dialogue as pair work when drawing.E. Task time. Let students design a card for their favorite teachers and describe it to others.Topic People’s appearance and charactersFunction Describing a person’s appearance and characters with various adjectivesV ocabulary University, fun, pretty, young, quiet, active ,strict .kind, cool, tall, short, thin Structure Is she quiet? No, she isn’t. She’s very active.Is she strict? Y es, she is, but she’s very kind.Activity Reading, speaking, drawingGrammar The structure of a general question and the answer to a general questionTeaching aids Multi-media, radio and tape, figure picturesDetailed teaching design for Period 1Step 1: W arming upBroadcast the short dialogue in Let’s start. Let the Ss guess the topic of this unit.T: Hi, everyone. Nice to see you again. What grade are you in now?Ss: We’re in Grade 5.T: Do you like your new English books?Ss: Y es!T: Please listen to the tape. Guess! What are we going to talk about in Unit 1?Ss: My new teachers!Design illustration: This is a very natural opening for a new class. In the new semester, students get new books and meet new teachers. Through the short dialogue, they can quickly understand the topic of this unit.Step 2: Presentation1. Present the hanging picture of Let’s learn and find out who is Sarah’s new art teacher by describing these teachers. Get the Ss review the words: strong tall short thin. And then present the new words: young kind old funny. At last, let them guess who Sarah’s art teacher is.T: They are Sarah’s teachers. Her music teacher is tall and strong. He is young and kind. Her math teacher is short and thin. He is very funny. Her art teacher is tall and thin. He is old. Who is Sarah’s art teacher?Ss: The man in the middle.Design illustration: Via the guessing activity, many new words are presented, which is considered as an input.2. Read and spell those words.(1) Listen to the radio and read the words after the radio.(2) List those words on the blackboard and get the students to read and spell after the teacher.T: Please look at the blackboard. Read after me. Tall, tall, t-a-l-l, tall.Ss: Tall, tall, t-a-l-l tall.T: Short, …Ss: Short, …T: …Ss: …Design Illustration: Through the recognizing, reading and spelling the new words in the blackboard, the students will get a direct impression for the new words, which contributes to a further study as input.3. Activity 1:Let’s Guess(1)The teacher show his/her own pictures whose face has been concealed by an animal in the PPT and get students to guess who he/she is. When the students give the right answer, guide them to know the sentence pattern “Who’s your…teacher?Mr./Miss.T:Hi,boys and girls. Can you guess who is he/she?Ss:She is Miss A,our English teacher.T:Who’s your English teacher?Ss:Mr./Miss A,,(2)Show another three teachers’ pictures in the same way and let student guess, one by one, that who is the person in the picture and give the sentence pattern the same way. And ask what he/she is like.T: V ery good. How about this one? Who is he?S1: He is Mr. B, our math teacher.T: Who’s your math teacher?S1: Mr. B.T: What’s he like?S1: He is tall and thin.T: Who is this man?S2: He is Mr. C, our Chinese teacher.T: Who is your Chinese teacher?S2: Mr. CT: What’s he like?S2: He is short and strong.T: …S3: …Design illustration: Starting from the English teacher himself/herself, and then to other others, this activity is very interesting and students’motivation for English learning and speaking shall be greatly improved by the process of satisfying their curiosity. All thewords learnt previously will be used at once, naturally transiting from input to output. Themain sentence patterns “Who is your … teacher? What’s … like?” are also presented inthis game.Step 3: Practicing.1. Activity2: Let’s chantWho’s your English teacher?Miss Chen,Miss Chen.What’s she like?Thin,thin,thin,English teacher is thin.Who’s your Chinese teacher?Miss Liu, Miss Liu.What’s she like?Old, old, old,Chinese teacher is short.Who’s your math teacher?Mr. Zhou,Mr. Zhou.What’s he like?Strong,strong,strong,math teacher is strong.Who’s your music teacher?Miss Qiu, Miss Qiu..What’s she like?Y oung,young,young,music teacher is young.Funny,funny,kind,they’re funny and kind.This activity should be started by the whole class with their hand clasping, and then between deskmates by one asking and the other answering.Design illustration: A rhythmic chant can make the atmosphere more active and relaxed.Students can remember and consolidate the words and sentence during the shortest time.What’s more, this is an activity that involves all the students in the class.2. Activity 3: Introduce teachers by rolling a snowballS1:She’s my English teacher.S2:She’s my English teacher. She’s tall.S3:She’s my English teacher. She’s tall and funny.S4:She’s my English teacher. She’s tall and funny. She has long hair.S5:She’s my English teacher. She’s tall and funny. She has long hair. She likes music.Design Illustration: through the practice step by step, from easy to difficult, when the snowball becomes bigger and bigger, students’ speaking ability shall be certainly trained and they will accumulate more vocabularies, including old and new ones.4. HomeworkFinish the relative exercises in the text book and the activity brochure.Write a short article named My Favorite Teacher.。

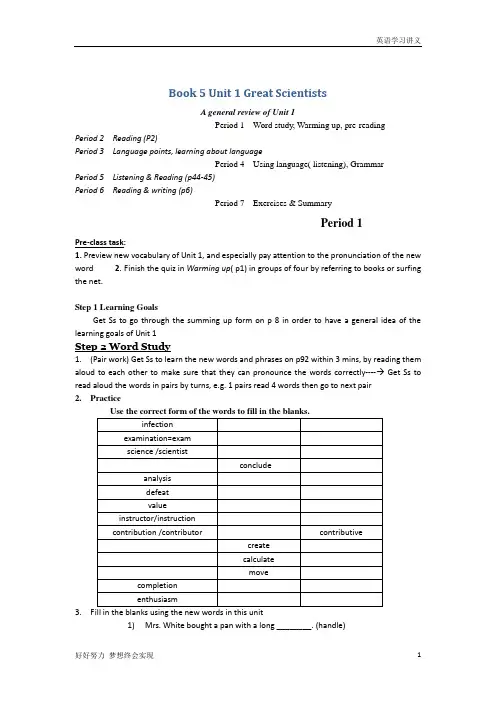

Book 5 Unit 1 Great ScientistsA general review of Unit 1Period 1 Word study, Warming up, pre-readingPeriod 2 Reading (P2)Period 3 Language points, learning about languagePeriod 4 Using language( listening), GrammarPeriod 5 Listening & Reading (p44-45)Period 6 Reading & writing (p6)Period 7 Exercises & SummaryPeriod 1Pre-class task:1. Preview new vocabulary of Unit 1, and especially pay attention to the pronunciation of the new word2. Finish the quiz in Warming up( p1) in groups of four by referring to books or surfing the net.Step 1 Learning GoalsGet Ss to go through the summing up form on p 8 in order to have a general idea of the learning goals of Unit 1Step 2 Word Study1. (Pair work) Get Ss to learn the new words and phrases on p92 within 3 mins, by reading them aloud to each other to make sure that they can pronounce the words correctly---- Get Ss to read aloud the words in pairs by turns, e.g. 1 pairs read 4 words then go to next pair2. Practice3.1)Mrs. White bought a pan with a long ________. (handle)2)The pollution is so ________ that we have to take some measures to stop it.(severe)3)He has a big nose that is a ________ of his family. (characteristic)4)Water and salt are ________ into our blood stream every day. (absorbed)5)If a doctor or a medical treatment ________ someone’s illness, they make theperson well again. (cure)6) A ________ is a kind of germ that can cause disease. (virus)Step 3. Warming up(Group competition) Check the answers to the quiz to find out which group know the most . Show pictures to introduce some scientists while Ss giving the correct answers-- congratulations to the winning groupStep 4 Pre-reading1. (Pair work) What five most important qualities do you think a scientist should have? Give reasons.clever/talented strict patient creative determined/strong-willed positivehonest energetic intelligent/hard-working ambitious careful co-operativeconfident brave2. (Group work) Ex2, p1Do you know how to prove a new idea in scientific research? Discuss in groups the stages in examining a new scientific idea. What order would you put them in?Draw a conclusion Think of a method Collect results Make up a question Find a problem Analyse the results Repeat if necessaryStep 5. Summary1.Seeing much, suffering much, and studying much are three pillars (支柱,要素) of learning.2.learning without thought is a labour lost; thought without learning is perilous(危险的)3. To know the disease is half the cure. 找出病根等于医治了一半。

Unit OneTEXT I Hit the Nail on the Head(恰到好处;一语中的)•III. Library Work•1. 1) Gustave Flaubert (1821 –1880), French novelist, was associated with, though not representative of, the movement of naturalism and known as one of the greatest realists of 19th-century France. He devoted his life to long hours spent in heavy toil over his work. His writing is marked by exactness and accuracy of observation, extreme impersonality and objectivity of treatment, and precision and expressiveness in style, or the principle of the mot juste.•1. 2) Mrs. Malaprop is a famous character in Sheridan’s comedy The Rivals(1775). She is noted for her blunders in the use of words. ―As headstrong(不受管束的)as an allegory(比方;寓言)(alligator) on the banks of the Nile‖ is one of her grotesque(荒唐的)misapplications. She also requests that no delusions(欺骗;迷惑)(allusions) to the past be made. She has given us the word malapropism(用词错误,尤指误用发音相似而意义全非的词)as a name for such mistakes. •2. Hindi(印地语)is a literary and official language of northern India. Swahili(斯瓦希里语)is a Bantu(班图) language that is a trade and governmental language over much of East Africa and in the Congo region. Bantus are people belonging to a group of tribes found in equatorial and southern Africa.•IV. Organization of the Text•1. An analogy between the unskilled use of the hammer and the improper choice of words (Paragraph 1)•2. The significance of finding the right words (Paragraphs 2 --- 3)•3. Semantic differences between words having the same root (Paragraphs 4 --- 7) •(1). Example 1 (human vs. humane) (Paragraph 4)•(2). Example 2 (anxiety vs. eagerness) (Paragraph 5)•(3). Example 3 (singularity vs. singleness) (Paragraphs 6 – 7)•4. Wrong choice of words caused by failure to recognize their connotations (Paragraph 8) •Examples: imprison, contain, sum up, epitomize and distill•5. Stylistic differences between synonyms (Paragraph 9)•Examples: in my childhood vs. when I was a child; love to watch vs. love watching; die vs. expire; poor vs. in indigent circum-stances•6. The abundance of specific words in English for general notions (Paragraph 10)•7. Conclusion (Paragraph 11): the importance of a good control and command over known words (A good writer is not measured by the extent of his vocabulary, but by his skill in finding the word that will hit the nail cleanly on the head. )•V. Key Points of the Text•Paragraph 1•knock over: hit … to fall 捶翻•drive something home: force (the nail) into the right place; make something unmistakably clear 把(钉子等)打入;使明确无误•E.g. (1). He slammed the door and drove the bolt home. 他砰地关上门,把门闩插好。

U5L1 Enlightening A Mind教案【学习主题】本课属于“人与社会”主题群中的“教育”子主题。

本文主要讲述了幼年时期因病丧失视觉和听觉的海伦·凯勒的励志故事。

海伦·凯勒两岁的时候,不幸患上了“猩红热”病,这种病很可能危机生命。

经过一段时间的治疗,小海伦的生命保住了,但是她却成了一个又聋又哑又盲的小姑娘。

后来,小海伦通过靠她的家庭教师莎莉文的循循教导和自己的顽强毅力终于走出黑暗、学业有成的故事。

其主题意义在于让学生加深对学生对当代西方作家的文学作品中语言的应用的理解,理解传记类记叙文的特点;并通过欣赏传记故事,激发学生对故事背后折射出的在本单元主题下的道理进行感悟---教育在改变命运方面所发挥的重大意义以及教师对个人成长、启迪心灵所启的关键作用。

【文本分析】What海伦·凯勒在十九个月的时候,因患急性胃充血、脑充血而丧失视力和听力。

自此,小海伦坠入了孤独和黑暗之中,性格也变得乖张暴戾,犹如一匹无法驯服的野马。

小海伦快到7岁的时候,一位名叫安妮的家庭教师来到了她的身边,传授给海伦知识,重塑海伦·凯勒的人生。

莎莉文老师开始用独特的方法打开了海伦的眼界,教海伦摸盲文,拼单词。

她们在花园闻紫罗兰的花香,享受温暖阳光,学习'love' 的含义,有时通过做手工项链,领悟'think' 的意义,小海伦在生活情境和脑海想象中感知着这个世界。

学习和教育增强了海伦面对生活的勇气和信心,走向人生成功之路。

海伦与莎莉文老师之间,是人间罕见的师生至情的传奇。

How本课文体属于传记类记叙文。

语篇由安妮·莎莉文成为海伦·凯勒的老师的背景以及安妮·莎莉文教与海伦·凯勒师生间展开的教与学的具体方法及过程两个部分组成。

第一部分陈述海伦·凯勒小时候有耳目失聪的艰难状况和暴躁脾气;海伦的父母经人推荐聘请来了安妮·莎莉文作为海伦·凯勒的家庭教师。

ComprehensionI. Judge which of the following best summarizes the main idea of the article.A. To be able to use the right word is an important component of one’s mastery of the English language.B. To facilitate one’s own process of cognition and one’s communication with others, one must be able to choose the right word from the extensive vocabulary of the English language.C. It is more important to know exactly the meaning and use of a relatively small number of words than to know vaguely a larger number.II. Determine which is the best choice for each of the following questions.1. “Clean English” in the first paragraph means .A. English of a dignified styleB. English free from swear wordsC. English which is precise and clear2.The word “realization” in the sentence “Choosing words is part of the process of realization…” means .A. articulating soundsB. fulfilling one’s goalsC. becoming aware of what one thinks and feels3. The example given in para. 3 of a man searching for the right word for his feelings about his friend illustrates the function words perform in .A. defining out thoughts and feelings for ourselvesB. defining our thoughts and feelings for those who hear usC. both A and B4. The word “cleanly” in the last sentence means .A. squarelyB. clearlyC. neatly5.The examples of the untranslatability of some words given in para. 11 best illustrate which sentence of the paragraph?A. The first sentence.B. The second sentence.C. The third sentence.III. Answer the following questions.1. Which sentence in the first paragraph establishes the link between the driving of a nail and the choice of a word?2. What does the word “this” in sent ence 1, para. 2, refer to?3. Do you agree with the author that there is a great deal of truth in the seemingly stupid question “How can I know what I think till I see what I say”?Why or why not?4. Explain why the word “imprison” in the example given in para. 9, though not a malapropism, is still not the right word for the writer’s purpose.5. What is the difference between “human” and “humane”? And the difference between “human action” and “humane action”, and also that between “human killer” and “humane killer”?6. What does the word “alive” in the sentence “a student needs to be alive to these differences” (para. 9) mean?7. Why is it difficult and sometimes even impossible to translate a word from one language into another as illustrated in para. 11? Supply some such examples with English and Chinese.8. The writer begins his article with an analogy between the unskilled use of the hammer and the improper choice of words. Identify the places where the analogy is referred to in the rest of the article.Language WorkI. Read the following list of words and consider carefully the meaning of each word. Then complete each of the sentences below using the correct form of an appropriate word from the list.Creep Loiter March Meander Pace Patrol Plod Prowl Ramble Roam SaunterShuffle Stagger Stalk Step Stride Strut Stroll Toddle Tramp Tread Trudge Walk1. After the maths examination Fred, feeling exhausted, across the campus.2. The soldiers reached their camp after 15 miles through the deep snow.3. It is pleasant to in the park in the evening.4. After the cross-country race Jack to the changing room.5. Last night when he sleepily to the ringing telephone, he accidentally bumped into the wardrobe.6. We saw him towards the station a few minutes before the train’s departure.7. The old couple through the park, looking for a secluded bench to sit on and rest.8. The newly-appointed general about the room like a latter-day Napoleon.9. Peter whistled happily as he along the beach.10. These old people liked to about the antique ruins in search of a shady picnic spot.11. Many tourists about the mall, windowshopping.12. We were fascinated by the view outside the room----a beautiful verdant meadow and brooks through it.13. Mary used to about the hills and pick wild flowers for her mother.14. Eager to see the pony in the stable, the children down the staircase, their hearts pounding violently.15. The lion had the jungle for a long time before it caught sight of a hare.16. My brother began to when he was ten months old.17. The farmers often let their horses freely in the meadow so that they could eat their fill of grass.18. The patrols were along through the undergrowth when the bomb exploded.19. The thugs were reported to be the streets for women workers who were on their way home after the afternoon shift.20. The first-year students not only learned how to , they were also taught how to take aim and shoot when they had military training.21. Sometimes Tom, our reporter, would up and down the study, deep in thought.22. When he was Third Street, Fred found the little match girl lying dead at the street corner.23. Secretaries hated seeing their new manager in and out of theoffice without even casting a glance at them.24. Mother asked us to lightly so as not to wake Granny.25. The refugees for miles and miles all day hunting for a place to work.26. When the pop singer out of the car, his fans ran to him, eager to get his autograph.27. The laborers on their way home after working in the plantation the whole day.28.The lion was feeling pretty good as he (A) through the jungle. Seeing a tiger, the lion stopped it.“Who is the King of the jungle?” the lion demanded.“You, O lion, are the King of the jungle,” replied the tiger.Satisfied, the lion (B) on, until he came across a large, ferocious-looking leopard.“Who is the King of the jungle?” asked the lion, and the leopard bowed in awe. “You, mighty lion, you are the King of the jungle,” it said humbly and (C) off.Feeling on top of the world, the lion proudly (D) up to a huge elephant an d asked the same question. “Who is the King of the jungle?”Without answering, the elephant picked up the lion, swirled him round in the air, smashed him to the ground and jumped on him.“Look,” said the lion, “there’s no need to get mad just because you didn’t know the answer.”II. Make a list of more specific words for each of the following general terms. For example, for WALK, you could list stride, stroll, saunter, plod, toddle and so on. Give sentences to illustrate how the words may be used.1. SAY2. SEE3. BEVERAGE4. EXCITEMENT5. DELIGHT6. SKILFULIII. In the following sentences three alternatives are given in parentheses for the italicized words. Select the one which you think is most suitable in the context.1. A clumsy (heavy, stupid, unskillful) workman is likely to find fault with his tools.2. As John was a deft (skillful, clever, ready) mechanic, he was hired by the joint-venture in no time.3. The writer made a point of avoiding using loose(vague, unbound, disengaged) terminology in his science fiction.4. We didn’t appreciate his subtle(delicate, tricky, profound) scheme to make money at the expense of the customers.5. Annie Oakley became famous as one of the world’s most precise (accurate, scrupulous, rigid) sharpshooters.6. The government in that newly-independent country has decided to make ashift (alteration, turn, transference) in its foreign policies.7. Misunderstanding arose on account of the vague(undetermined, confused, ambiguous) instructions on the part of the manager.8. If soldiers do not pay scrupulous (exact, vigilant, conscientious) attention to orders they will not defeat the enemy.9. In some areas, the virgin forest has been cut through ignorance (blindness, want of knowledge, darkness) of the value of trees.10. Since many pure metals have such disadvantages (harm, unfavourableness, drawbacks) as being too soft and being liable to rust too easily, they have little use.11. My colleague, Mr. Hill, has a small but well-chosen library, where it is said he spends most of his spare time cultivating(nourishing, tilling, developing) his mind.12. If you think photography is my hobby, your belief is quite mistaken (fraudulent, erroneous, deceitful).13. What appears to the laymen as unimportant (minute, trivial, diminutive) and unrelated facts is often precious to the archaeologist.14. The lounge has a seating capacity of 30 people but it is too dark (dim, dingy, gloomy) to read there.15. These career-oriented women are used to flexible (adaptable, willowy, docile) working hours in the office.16. Only experts with a professional eye can tell the fine(fair, pleasant,subtle) distinction between the two gems.17. The goose quill pen has a great sentimental (tender, emotional, soft) appeal to Emily as it was a gift from her best friend.18. Being thoughtful of and enthusiastic towards others is the essence (gist, kernel, quintessence) of politeness.19. When Iraq destroyed some of its nuclear and chemical weapons, it acted under coercion (repression, concession, compulsion).20. My uncle’s oft-repeated anecdotes of his adventures in Africa were fascinating (catching, pleasing, absorbing ) to listen to.IV. Give one generic term that covers each of the following groups of words.1. artificer, turner, joiner, carpenter, weaver, binder, potter, paper-cutter2. volume, brochure, pamphlet, treatise, handbook, manual, textbook, booklet3. painter, sculptor, carver, poet, novelist, musician, sketcher4. grin, smirk, beam, simper5. donation, subscription, alms, grant, endowment6. bandit, poacher, swindler, fraud, embezzler, imposter, smuggler7. nibble, munch, devour, gulp8. drowse, doze, slumber, hibernate, coma, rest, nap9. manufacture, construct, weave, compose, compile10. ancient, antique, old-fashioned, obsolete, archaic11. slap, tap, pat, thump, whack12. alight, descend, dismount, disembarkV. Fill in each blank with an appropriate word.In discussing the relative difficulties of analysis which the exact and inexact sciences face, let me begin with an analogy. Would you agree that swimmers are (1) skilful athletes than runners (2) swimmers do not move as fast as runners? You probably would (3) . You would quickly point out (4) water offers greater (5) to swimmers than the air and ground do to (6) Agreed, that is just the point. In seeking to (7) their problems, the social scientists encounter (8) resistance than the physical scientists. By (9) I do not mean to belittle the great accomplishments of physical scientists who have been able, for example, to determine the structure of the atom (10) seeing it. That is a tremendous (11) yet (12) many ways it is not so difficult as what the social scientists are expected to (13) . The conditions under which the social scientists must work would drive a (14) scientist frantic. Here are five of (15) conditions. He can perform (16) experiments; he cannot measure the results accurately; he (17) control the conditions surrounding (18) experiments; he is of the expected to get quick results(19) slow-acting economic forces; and he must work with people,(20) with inanimate objects…VI. Following Warner’s model of establishing an analogy between two dissimilar things, write a passage, discussing the learning of a foreign language. You are supposed to use an analogy to help you explain. For instance, you may compare the learning of a foreign language to that of swimming, bike-riding, etc.UNIT 1 TEXT 1Exercises KeysComprehension:I. B ;II. 1.C 2.C 3.C 4.A 5.C ;III. 1. “So with language; …firmly and exactly.”2. Getting the word that is completely right for the writer’s purpose.3. Yes, I do. It sounds irrational that a person does not know what he himself thinks before he sees what he says. But as a matter of fact, it is quite true that unless we have found the exact words to verbalize our own thoughts we can never be very sure of what our thoughts are; without words, our thoughts cannot be defined or stated in a clear and precise manner.4. “Malapropism” means the unintentional misuse of a word by confusing it with one that resembles it, such as human for humane, singularity for singleness. But the misuse of “imprison” is a different case. It is wronglychosen because the user has failed to recognize its connotation.5. human=of, characterizing, or relating to manhumane=characterized by kindness, mercy, sympathyThus: human action=action taken by man; humane action=merciful action; human killer=person that kills humans ; humane killer=that which kills but causes little pain6. sensitive, alert7. Those are words denoting notions which are existent only in specific culture, not universally shared by all cultures. English words difficult to be turned into Chinese: privacy, party, lobby (v.), etc. Chinese words difficult to be turned into English: 吹风会,粽子,五保户,etc.8. “We don’t have to look far afield to find evidence of bad carpentry.”“It is perhaps easier to be a good craftsman with wood and nails than a good craftsman with word s.”“A good carpenter is not distinguished by the number of his tools, but by the craftsmanship with which he uses them. So a good writer is not measured by the extent of his vocabulary, but by his skill in finding the ‘mot juste’, the word that will hit t he nail cleanly on the head.”Language Work:I. 1. shuffled/trudged 2. trudging 3. stroll 4. staggered 5. staggered 6. striding 7. strolled 8. strutted 9. sauntered/strolled 10. ramble/roam 11.loitered 12. meandering 13. roam 14. crept 15. prowled 16. toddle 17. roam 18. creeping 19. prowling 20. march 21. pace 22. patrolling 23. stalking 24. tread 25. tramped 26. stepped 27. plodded 28. A. prowled/strutted B. strolled/sauntered C. walked/crept D. marched/struttedII.1.SAY: speak, tell, declare, pronounce, express, state, argue, affirm, mention, allege, recite, repeat, rehearse2. SEE: behold, look at, glimpse, glance at, view, survey, contemplate, perceive, notice, observe, discern, distinguish, remark, comprehend, understand, know3. BEVERAGE: liquor, wine, beer, tea, coffee, milk drink, soft drink4. EXCITEMENT: agitation, perturbation, commotion, disturbance, tension, bustle, stir, flutter, sensation5. DELIGHT: joy, gladness, satisfaction, charm, rapture, ecstasy, pleasure, gratification6. SKILFUL: apt, ingenious, handy, ready, quick, smart, expert, capable, able, gifted, talented, dexterous, cleverIII. 1. clumsy----unskillful 2. deft----skillful 3. loose----vague 4. subtle----tricky 5. precise----accurate 6. shift----alteration 7. vague----ambiguous8. scrupulous----conscientious 9. ignorance----want of knowledge 10. disadvantages----drawbacks 11. cultivation----developing 12.mistaken----erroneous 13. unimportant----trivial 14. dark----dim 15. flexible----adaptable 16. fine----subtle 17. sentimental----emotional 18. essence----quintessence 19. coercion----compulsion 20. fascinating----absorbingIV. 1. craftsman 2. book/publication 3. artist 4. smile 5. contribution 6. law-breaker 7. eat 8. sleep 9. make 10. old 11. hit 12. get offV. 1. less 2. because/since/as 3. not 4. that 5. resistance 6. runners 7. solve 8. greater/more 9. that 10. without 11. achievement/feat 12. in 13. do 14. physical 15. those 16. few 17. cannot 18. the 19. with 20. not。

pepBook5Unit1教案unit 1 my new teachers第一课时教学目标与要求1、能听、说、认、读,并理解本课的五个新单词:young, heavy, old , funny, kind;2、能掌握句型:who’s your…? what’s he /she like? 并能在具体的语境中运用;3、培养学生热爱、尊敬老师的情感。

教学建议ⅰ.warm-up1、show a picture of some classrooms. (采用图片或cai的形式呈现,根据不同学校的条件而定)music room /art room /computer room / lab2、点击cai,各个教室出现不同的老师或继续采用图片的形式:将各个教师贴到相应的教室里。

who is he/she?he /she ‘s our music / art / computer / science teacher.3、根据以前学过的描述人物的形容词,结合呈现的教师自编一个chant,营造课堂气氛,激发学生的积极性,同时也为下面引出新词作铺垫。

chant: tall, tall, tall, computer teacher. is tall.short , short ,short , science teacher. is short.thin , thin ,thin , art teacher. is thin.fat , fat ,fat ,music teacher. is fat.funny , funny, funny ,they’re so funny!ii. presentation1、采用cai 的形式设计一位转学来校就读的新朋友:zip让他做一个有趣的动作.t: this is zip, he is….s: funny!t: yes, he is funny, do you like him ? this term he will be our new classmate.2、cai点击zip,让zip自己介绍:hello! i’m zip .i’m glad to be your new classmate. this is a picture of my former school.(cai出示主情景图)3、cai: zip介绍自己的老师:(a) look! this is my math teacher (教师拿出一本数学书解释).he’s tall and thin.t: who is your chinese teacher? zip假装听不清,教师适时让全班学生一起问他:who is your chinese teacher?t:miss zhang. what’s she like? (学生read,教师用态势语帮助学生理解)can you tell me ?ss: he’s short and fat!zip: yes, he’s short and heavy . (read 用夸张的的体态语描述) practice: “heavy”. (出示一些卡通胖人物的图片:zoom, zhu bajie , etc) (b) ss:(教师启发学生问) who is your music teacher and who is your art teacher?zip:guess !ss guess.ss: what’s he /she like ?(compare)zip: she is young and he is old(长着胡须). (read)practise: t:i ’m old ,you are young.让学生逐个说:i’m young , you are old.(c) ss :who is your computer teacher?zip:m r li.t:(出示这位老师和蔼可亲的笑脸)what’s he like?ss: he’s…(让学生随意描述,之后教师导出kind)播放常识老师悉心辅导zip的一个片段,zip:my science teacher is kind ,too.t: let’s see, in our school, who is kind? am i kind?practise: my …teacher is kind./ xx is kind.(让学生说说自己的老师和同学)ⅲ. practice/consolidation●活动设计①:make a new chant. (cai)共7页,当前第1页1234567 my grandma is old, my mother is young.my father is tall, my little brother’s short.zoom is heavy, zip is funny.they are all very kind. and i’m kind, too.活动目的:综合呈现新学单词,在歌谣中得以巩固,避免机械地朗读。

Unit 1 Great scientistsTeaching aims1.To help students learn to describe people2.To help students learn to read a narration about John Snow3.To help students better understand “Great scientists”4.To help students learn to use some important words and expressions5.To help students identify examples of “The Past Participle (1) as the Predicative & theattribute”Period 1 Warming up and readingTeaching ProceduresI. Warming upStep I Lead inTalk about scientist.T: Hi, morning, class. Nice to see you on this special day, the day when you become a senior two grader. I am happy to be with you helping you with your English. Today we are to read about a certain scientist. But first let’s define the word “scientist”. What is a scientist?A scientist is a person who works in science, trying to understand how the universe or other things work.Scientists can work in different areas of science. Here are some examples: Those that study physics are physicists. Those that study chemistry are chemists. Those that study biology are biologists.Step IIAsk the students to try the quiz and find out who knows the most.T: There are some great scientific achievements that have changed the world. Can you name some of them? What kind of role do they play in the field of science? Do these achievements have anything in common? Match the inventions with their inventors below before you answer all these questions.1. Archimedes, Ancient Greek (287-212 BC), a mathematician.2. Charles Darwin, Britain (1808-1882). The name of the book is Origin ofSpecies.3. Thomas Newcomen, British (1663-1729), an inventor of steam engine.4. Gregor Mendel, Czech, a botanist and geneticist.5. Marie Curie, Polish and French, a chemist and physicist.6. Thomas Edison, American, an inventor.7. Leonardo da Vinci, Italian, an artist.8. Sir Humphry Davy, British, an inventor and chemist.9. Zhang Heng, ancient China, an inventor.10. Stepper Hawking, British, a physicist.II. Pre-readingStep IGet the students to discuss the questions on page 1 with their partners. Then ask the students to report their work. Encourage the students to express their different opinions.1.What do you know about infectious diseases?Infectious diseases can be spread to other people. They have an unknown cause and need public health care to solve them. People may be exposed to infectious disease, so may animals, such as bird flu,AIDS, SARS are infectious diseases. Infectious diseases are difficult to cure.2.What do you know about cholera?Cholera is the illness caused by a bacterium called Vibrio cholerae. It infects people’s intestines(肠), causing diarrhea and leg cramps (抽筋).The most common cause of cholera is by someone eating food or drinking water that has been contaminated(污染) with the bacteria. Cholera can be mild(不严峻的) or even without immediate symptoms(病症), but a severe case can lead to death without immediately treatment.3. Do you know how to prove a new idea in scientific research?Anybody might come out with a new idea. But how do we prove it in scientific research? There are seven stages in examining a new idea in scientific research. And they can be put in the following order. What order would you put the seven in? Just guess.Find a problem→ Make up a question→ Think of a method→ Collect results→Analyse the results→ Draw a conclusion→ Repeat if necessaryIII. ReadingStep I Pre-reading1.Do you know John Snow?John Snow is a well-known doctor in the 19th century in London and he defeated “King Cholera”.2.Do you know what kind of disease is cholera?It is a kind of terrible disease caused by drinking dirty water and it caused a lot of deaths in the old times and it was very difficult to defeat.L e t’s g e t t o k n o w h o w D r.J o h n S n o w d e f e a t e d“K i n g C h o l e r a”i n1854i n L o n d o n i n t h i s r e a d i n g p a s s a g e:Step II SkimmingRead the passage and answer the questions.1.Who defeats “King Cholera“? (John Snow)2.What happened in 1854? (Cholera outbreak hit London.)3.How many people died in 10 days? (500)4.Why is there no death at No. 20 and 21 Broad Street as well as at No. 8 and 9Cambridge Street?(These families had not drunk the water from the Broad Street pump.)(Optional)Skim the passage and find the information to complete the form below.Step III ScanningRead the passage and number these events in the order that they happened.2 John Snow began to test two theories.1 An outbreak of cholera hit London in 1854.4 John Snow marked the deaths on a map.7 He announced that the water carried the disease.3 John Snow investigated two streets where the outbreak was very severe.8 King Cholera was defeated.5 He found that most of the deaths were near a water pump.6 He had the handle removed from the water pump.Step IV Main idea and correct stageRead the passage and put the correct stages into the reading about research into a disease.Step V Group discussionAnswer the questions (Finish exercise 2 on Page 3)1. John Snow believed Idea 2 was right. How did he finally prove it?(John Snow finally proved his idea because he found an outbreak that was clearly relatedto cholera, collected information and was able to tie cases outside the area to the polluted water.)2. Do you think John Snow would have solved this problem without the map?(No. The map helped John Snow organize his ideas. He was able to identify those households that had had many deaths and check their water-drinking habits. He identified those houses that had had no deaths and surveyed their drinking habits. The evidence clearly pointed to the polluted water being the cause.)3. Cholera is a 19th century disease. What disease do you think is similar to cholera today?(Two diseases, which are similar today, are SARS and AIDS because they are both serious, have an unknown cause and need public health care to solve them.)Step VI Using the stages for scientific research and write a summary.Period 2&3 Language focusStep I Warming up1.characteristic①n. a quality or feature of sth. or someone that is typical of them and easy to recongnize.特点;特性What characteristics distinguish the Americans from the Canadians.② a. very typical of a particular thing or of someone’s characer 典型性的,Such bluntness is characteristic of him.Windy days are characteristic of March.[辨析]characteristic与charactercharacteristic是可数名词,意为“不同凡响的特点“character表示(个人、集体、民族特有的)“性格、品质”,还意为“人物;文字”What you know about him isn’t his real character.2. put forward: to state an idea or opinion, or to suggest a plan or person, for other people to consider提出He put forward a new theory.The foreigners have put forward a proposal for a joint venture.An interesting suggestion for measuring the atmosphere around Mars has been put forward.☆ put on穿上;戴上;增加put out熄灭(灯);扑灭(火) put up with…忍受put down写下来;放下;put off 延误; 延期put up成立; 建造,put up举起,搭建,粘贴3. analyze: to examine or think about something carefully in order to understand it vt.分析结果、检讨、细察A computer analyses the photographs sent by the satellite.The earthquake expert tried to analyze the cause of the earthquake occurred on May 12,2020.Let’s analyze the problem and see what went wrong.He analyzed the food and found that it contained poison.We must try to analyze the causes of the strike.☆ analysis n.分析,解析,分解4. conclude: decide that sth. is true after considering al the information you have 得出结论;推论出to end sth. such as a meeting or speech by doing or saying one final thing vt. & vi终止,终止;We concluded the meeting at 8 o’clock with a prayer.From his appearance we may safely conclude that he is a heavy smoker.What do you conclude from these facts?We conclude to go out / that we would go out.conclusion n.结论arrive at a conclusion; come to a conclusion; draw a conclusion; reach a conclusionWhat conclusion did you come to / reach / draw / arrive at?From these facts we can draw some conclusions about how the pyramids were built.Step 2 Reading1. defeat① vt. to win a victory over someone in a war, competition, game etc.打败,战胜,使受挫I’ve tried to solve the problem, but it defeats me!Our team defeated theirs in the game.② n.失败,输failure to win or succeedThis means admitting defeat.They have got six victories and two defeats.[辨析]win, beat与defeat①win “博得”赛事、战事、某物;后接人时,意为“争取博得…的好感或支持;说服”②beat “战胜”“击败”竞赛中的对手,可与defeat互换We beat / defeated their team by 10 scores.They won the battle but lost many men.The local ball team won the state championship by beating / defeating all the other teams.I can easily beat /defeat him at golf.He is training hard to win the race and realize his dream of becoming a champion at the 2020 Olympic Games.2. expert①n. someone who has a special skill or special knowledge of a subject专家,能手an expert in psychology an agricultural expert② a. having special skill or special knowledge of a subject熟练的,有专门技术的an expert rider an expert job需专门知识的工作He is expert in / at cooking.3. attend vt. &vi 参加,注意,照料① be present at参加attend a ceremony / lecture / a movie / school / class / a meetingI shall be attending the meeting.Please let me know if you are unable to attend the conference.② attend to (on): to look after, care for, serve伺候, 照顾,看护The queen had a good doctor attending on her.Dr Smith attended her in hospital. 医治Are you being attended to?接待Mother had to attend to her sick son.③ attend to处置,注意倾听attend to the matterA nurse attends to his needs.Can you attend to the matter immediately?I may be late – I have got one or two things to attend to.Excuse me, but I have an urgent matter to attend to.[辨析]attend, join, join in与take part in①attend指参加会议、上课、上学、听报告等②join 指加入某组织、集体,成为其中一员③join in指加入某种活动;表示与某人一路做某事join sb. in sth.④take part in指参加正式的、有组织的活动,切在活动中起踊跃作用Only 2 people attended the meeting.He joined the Communist Youth League in 2007.Will you join us in the game?We often tale part in the after-class activities.4. expose : to show sth. that is usually covered暴露expose sth. to the light of day 把某事暴露于青天白日之下I threatened to expose him ( to the police). 我要挟要(向警察)揭发他.He exposed his skin to the sun.他把皮肤暴露在阳光下.The old man was left exposed to wind and rain.When he smiled he exposed a set of perfect white teeth.5. cure vt. & n. to make someone who is ill well agian医治,痊愈When I left the hospital I was completely cured.①cure sb of a diseaseWhen you have a pain in your shoulders, you will go to see a doctor. The doctor will cure you.The only way to cure backache is to rest.He will cure the pain in your shouldersWhen I left the hospital I was completely cured.The illness cannot be cured easily.Although the boy was beyond cure, his parents tried to cure him of bad habits.②a cure for a diseaseAspirin is said to be a wonderful cure for the pain.There is still no cure for the common cold.Is there a certain cure for cancer yet?③a cure for sth.: to remove a problem, or improve a bad situation解决问题,改善窘境The prices are going up every day, but there is no cure for rising prices.[辨析]cure与treat①cure要紧指痊愈,强调的是结果②treat强调医治进程,指通过药物、专门的食物或运动医治病人或疾病,不强调结果。

课题Unit 1 第1课时设计者教学要点能听懂问句Who’s your art teacher? Is he young?并能做出正确回答;能听、说、读、写单词old,young,funny,kind,strict,并能在上下文中理解其意思;能理解描述人物外貌特征。

教学设计:(一)热身/复习(Warm-up/Revision)1、教师播放四年级上册Unit 2 Let’s do 录音,要求学生一边做动作一边说,让学生复习与本单元教学话题有关联的知识。

Put your Chinese book in your desk.Put your pencil box on your English book.Put your math book under your schoolbag.Put your eraser near your pencil box.2、教师出示各学科的课本,要求学生按听到的顺序分别展示自己的课本:Show me your math book.……看谁反应最快3、播放三下Unit 3 Let’s do录音,一起做动作一起说Big,big,big! Make your eyes big!……然后出示可用于描述人物特征的单词卡片,复习学过的形容词:tall, short, thin, long, big, small等,要求学生看卡片快速说出单词并拼写(二)呈现新课(Presentation)1、教学单词old,young展示课本上插图,并解释:This is our music teacher, Mr Young. He’s old. This is our art teacher, Mr Jones. He’s young.然后教师对学生说:I’m old. You are young.操练这两个单词2、同上教学funny,kind,strict3、多媒体展示Let’s learn 部分中五位教师的图片,教师指着其中一张,与一生进行示范对话:-Who’s your art teacher?-Mr Jones.-Is he young?-Yes, he is.Work in pairs(三)Consolidation & extension1)画一画某个学科的老师,并夸一夸(四)Homework:1.本课时的四会单词抄写四遍修改:教后反思:课题Unit 1 第2课时设计者教学要点能听懂、会说Who’s he? He’s our music teacher. Is he young? No, he isn’t. He’s old.等;能够运用这些巨型讨论新教师、新同学;能够听懂Let’s try 的录音内容并勾出你所听到的图片;了解中西方称呼上的差异。

人教版英语必修五 Unit 1 教案教学目标本单元的教学目标主要包括以下几个方面:1. 帮助学生掌握本单元的词汇和短语;2. 培养学生的听、说、读、写等语言技能;3. 培养学生的跨文化交际能力;4. 培养学生独立思考和解决问题的能力;5. 培养学生对英语研究的兴趣和积极性。

教学内容本单元的教学内容主要包括以下几个方面:1. 课文《Growing Pains》的研究和理解;2. 词汇和短语的研究;3. 听力、口语、阅读、写作等技能的训练;4. 跨文化交际的研究。

教学步骤1. 导入新课,介绍本单元的主题和目标;2. 学生自主研究课文,并进行听力练;3. 进行课文的理解和讨论,引导学生思考和表达观点;4. 研究和掌握本单元的词汇和短语;5. 进行听说训练,提高学生的口语表达能力;6. 进行阅读和写作训练,培养学生的阅读理解和写作技能;7. 进行跨文化交际的研究,增进学生对英语和其他文化的认识。

教学评价本单元的教学评价主要以以下方式进行:1. 各种形式的课堂练和作业,检测学生对知识的掌握程度;2. 口语和写作表现的评价,评估学生语言运用的能力;3. 学生参与课堂讨论和发言的情况,评估学生的思维能力和表达能力。

教学资源本单元的教学资源包括以下几个方面:1. 课本《人教版英语必修五》;2. 音频材料;3. 多媒体设备;4. 教学课件和作业练册。

以上为《人教版英语必修五 Unit 1 教案》的简要内容,旨在帮助教师设计和安排本单元的教学活动。

具体的教学步骤和细节应根据实际情况进行调整和完善。

PEP5 Unit1 What’s he like?B Let’s learn一、教学目标:1. 学生能听、说、读、写单词“polite”, “hard-working”, “helpful”, “clever”和“shy”。

2. 学生能灵活运用句型“What’s ... like?”, “He’s/She’s ...”谈论人物的性格特征。

3. 能完成“Match and say”部分的连线和对话任务。

教学重点:掌握三会单词。

二、教学重点:1. 能听、说、读、单词“polite”,“hard-working”,“helpful”,“clever”和“shy”。

2. 能灵活运用句型“What’s ... like?”,“He’s/She’s...”谈论人物的性格特征。

三、教学难点:1. 问句“What’s ... like?”的理解和运用。

2. 新词汇的学习。

3. 了解具有不同性格特征人的日常行为表现。

四、教学准备:课件、词卡、光盘五、教学过程:Step1 Warm up1.Free talkWhat’s the wheather like today? It’s……T: This term I am your new English teacher. Let’s say something about me.What’s Mr. Li like?Ss: Mr. Li is thin/tall/cute/strict/funny/friendly/kind...Step2 Presentation1.出示Oliver图片,引出politeT: Who’s he?Ss: He’s Oliver.T: Is he friendly?Ss: Yes, he is.T: Is he polite?Ss: Yes, he is.(板书polite,拆音拼读单词po-lite)用“Pat and say”游戏巩固单词,教师出示词卡,学生拍打词卡并大声读出。