wiki 百科美国文化 31页 - 副本

- 格式:doc

- 大小:292.00 KB

- 文档页数:33

美国文化美国文化美国各州有哪些有意思的习俗? (2)美国各州的比较 (9)美国各州有哪些有意思的习俗美国各州有哪些有意思的习俗??美国作为一个heterogeneous 的移民国家,相对来说各个族裔的融合度比较高,“普世价值”称霸主流文化;相对其他homogeneous 的民族国家,“习俗”这种概念并不常见。

题主所指可能是生活习惯上的差异,aka.「独特的地方」。

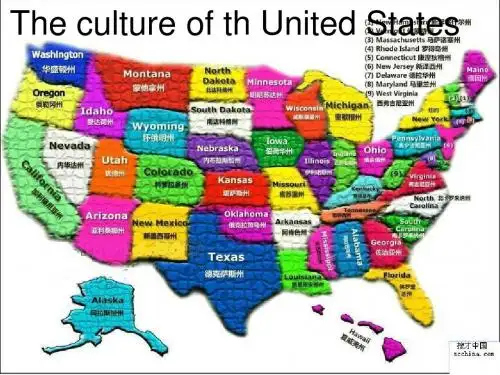

根据地区差异(Regional variations),美国分为如下几个地区:新英格兰地区(New England),中大西洋地区(the Mid-Atlantic states),南部地区(the Southern United States),中西部地区(the Midwestern United States),西海岸地区(the Western United States)。

其中西海岸地区还可以分为太平洋沿岸各州(Pacific States)和山地各州(the Mountain States)。

国内的文化差异主要是区域差异,但区域内部的文化和生活习惯大致相同(就好像中国分为东北、华北、西北、华南、东南、西南等区域)。

1、“圣经带圣经带””(Bible Belt):指的是美国东南及中南部各州,包括德克萨斯、俄克拉荷马、路易斯安那、阿肯色、田纳西、密西西比、肯塔基、亚拉巴马、佐治亚、南卡罗来纳、北卡罗来纳等黑人比例较高的州。

由于该地区有大量的福音派新教徒,民风非常保守,对宗教十分狂热,日常行事都要以圣经作为基本准则,去教堂做礼拜的人数比例(church attendance)要远远高于美国其它地区。

在美剧TBBT(生活大爆炸)中,Sheldon 就因为来自保守的南方Texas 而常被大家取笑他家乡和他妈妈的生活习惯。

(上图为2000年美国主要教堂的数量与分布,下方图例从左至右依次为Baptist浸信会-1302座,Catholic天主教-1164座,Christian基督教-72座,Latter-Day Saints末世圣徒教-80座,Lutheran路德教-250座,Mennonite门诺派-10座,Methodist卫理公会-219座,Reformed改革派-9座,其它-35座)2、每年3月17日的爱尔兰节日圣帕特里克节(St.Patrick's Day),芝加哥市内的芝加哥河都会被染成绿色,纽约的第五大道也会举行大游行,全国各地的人们也都会穿上至少一件绿色的衣服、裤子、鞋子、包甚至帽子= =。

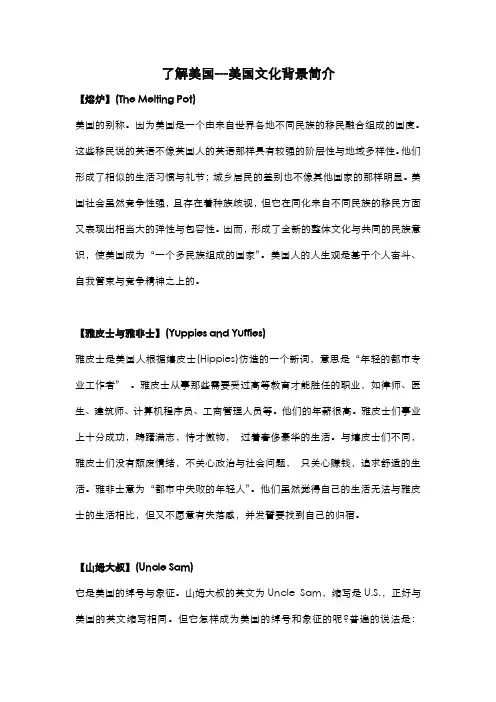

了解美国---美国文化背景简介【熔炉】(The Melting Pot)美国的别称。

因为美国是一个由来自世界各地不同民族的移民融合组成的国度。

这些移民说的英语不像英国人的英语那样具有较强的阶层性与地域多样性。

他们形成了相似的生活习惯与礼节;城乡居民的差别也不像其他国家的那样明显。

美国社会虽然竞争性强,且存在着种族歧视,但它在同化来自不同民族的移民方面又表现出相当大的弹性与包容性。

因而,形成了全新的整体文化与共同的民族意识,使美国成为“一个多民族组成的国家”。

美国人的人生观是基于个人奋斗、自我管束与竞争精神之上的。

【雅皮士与雅非士】(Yuppies and Yuffies)雅皮士是美国人根据嬉皮士(Hippies)仿造的一个新词,意思是“年轻的都市专业工作者”。

雅皮士从事那些需要受过高等教育才能胜任的职业,如律师、医生、建筑师、计算机程序员、工商管理人员等。

他们的年薪很高。

雅皮士们事业上十分成功,踌躇满志,恃才傲物,过着奢侈豪华的生活。

与嬉皮士们不同,雅皮士们没有颓废情绪,不关心政治与社会问题,只关心赚钱,追求舒适的生活。

雅非士意为“都市中失败的年轻人”。

他们虽然觉得自己的生活无法与雅皮士的生活相比,但又不愿意有失落感,并发誓要找到自己的归宿。

【山姆大叔】(Uncle Sam)它是美国的绰号与象征。

山姆大叔的英文为Uncle Sam,缩写是U.S.,正好与美国的英文缩写相同。

但它怎样成为美国的绰号和象征的呢?普遍的说法是:1812年,美英战争期间,美国特罗城有一个专门供应军用牛肉的商人(也有的说是军事订货的官员)名叫山姆尔〃威尔逊(Samuel Wilson,1776—1854),人们平时都叫他山姆大叔(Uncle Sam)。

美国政府收购他的牛肉箱上都盖U.S.字样。

人们遂开玩笑说这些盖有U.S.字样的箱子都是山姆大叔的。

后来“山姆大叔”便成了美国的绰号。

19世纪30年代,美国画家又将“山姆大叔”画成一个留有山羊胡子的瘦长老人,帽子和裤子都有星条旗的标志。

中文维基百科中文维基百科是维基百科协作计划的中文版本,自2002年10月24日正式成立,由非营利组织──维基媒体基金会负责维持,截至2010年6月30日14:47,中文维基百科已拥有314,167条条目,累计编辑次数达13,708,705次。

此外还设有其他独立运作的中文方言或版本,包括闽南语维基百科、粤语维基百科、文言文维基百科、吴语维基百科、闽东语维基百科、赣语维基百科及客家语维基百科等。

名称来源在这个网站启用时,仅以“中文Wikipedia”为名。

直到2003年10月21日,Wikipedia的中文名,经过13人投票,命名为“维基百科”。

首先“维基”二字符合中国大陆的译名标准,另外“维”字意为系物的大绳,也做网解释,可以引申为因特网,“基”是事物的根本,或是建筑物的底部。

“维基百科”合起来可引申为因特网中装载人类基础知识的百科全书。

中文维基百科的副题是“海纳百川,有容乃大”。

这是中国清朝大臣林则徐(1785年——1850年)于1839年为广州越华书院所创作的对联的上联,下联原为“壁立千仞,无欲则刚” 。

“海纳百川”语出《管子·形势解》,意指海洋之所以广大,是因为它不分你我地容纳了数以百计的河流。

“有容乃大”则语出《尚书·周书·君陈》。

对联的上联勉励待人接物应仿效海洋,以宽大的胸襟和宽容的态度去接纳不同的人事地物。

这同时也配合了维基百科自由开放的宗旨。

主要特点中文维基百科正如维基百科本身,有三个引人注意的特点。

正是这些特点使中文维基百科与传统的中文百科全书有所区别:首先,中文维基百科将自己定位为一个包含人类所有知识领域的百科全书,而不是一本词典、在线的论坛或其他任何东西。

其次,计划本身是一个wiki,这允许了大众的广泛参与。

中文维基百科是第一个使用wiki系统进行百科全书编撰工作的中文协作计划。

还有一个重要的特点,那就是中文维基百科是一部内容开放的百科全书。

内容开放的材料允许任何第三方不受限制地复制、修改及再发布材料的任何部分或全部。

AfterwordGrowing up on the Great Plains, I learned my history in scattered patches. There was a photograph of an antique threshing machine hanging on Grandfather‟s wall. There was prime-time television, which for a while was devoted to stories of cattle drives and cow towns. My parents took me to notorious Dodge City where gunfighters were buried with their boots on and to Pawnee Rock where wary Indians watched the white man‟s caravans moving down the Santa Fe Trail. Later I found in books a more coherent but no more critical saga of frontier settlement: the coming of railroads, homesteaders, and winter wheat. Nobody, however, ever explained the significance of grass.It took me a while to discover that the Great Plains were by nature a grassland. They had been so for millions of years—one of nature‟s winning designs. Evolution had equipped the grasses to survive all but the most prolonged droughts. Above ground they might look scraggly and dead, but underground they maintained tangled, deep-reaching, perennial root systems with remarkable recovery potential. For resilience in the face of natural adversity nothing matched the grasses. Before the coming of the steel plow all other forms of life depended on this resilience; it was the grasses that made ecological community possible.Seeing my region‟s history from a grassy point of view came only after I had left home, left Kansas, and even wandered outside the normal boundaries of the discipline of history. I learned from ecologists like Paul Sears, Rachel Carson, and Aldo Leopold. Captivated by their visionary knowledge, I undertook to write my first book on the history of ecology in Britain and the United States.1 During that project I discovered notonly the Dust Bowl, which had almost never figured in the stories I had been told as a child, but also that some of the world‟s pioneering ecologists had lived on the Great Plains and studied native prairies even before the white man finished plowing them up. In the minds of farmers, there was “nothing here but grass.” But for scientists, what was “here” was a remarkable story in the evolution of life on the planet—a history of ecological interdependence and complexity.Evolution was a dirty word where I grew up. It is still a forbidden word, still associated with the infidel Charles Darwin, whose science is not accepted as valid by many plains people almost a century and a half after its first publication. Indeed, among a large portion of the citizenry all those infamous “e” words—evolution, ecology, and environment--are spoken with a sneer or a whisper. They are regarded as part of some pagan doctrine that devout minds must relentlessly oppose. But how could anyone truly understand the grasses or the deeper history of the Great Plains without acknowledging ecology, evolution, and Darwinian biology?If growing up on the Plains left me ignorant about the natural realities of the region, it also left me ignorant about another “e” word: economy. To be sure, we constantly talked about economic topics in my youth --making a living, exploiting one‟s opportunities, accumulating wealth. But few of us ever gained a truly systematic, comprehensive, or critical understanding of the economic system in which we were embedded. We were as naïve about economic as about ecological complexity.God, we knew, had put us here to subdue the earth. He had given us one of the toughest assignments in His created universe, but we knew that we were up to the job of turning dreary wasteland into gritty profit and did not require any further instruction.Leaving home and getting a formal education at a renowned graduate school, unfortunately, did not altogether remedy my shallow understanding of the past. Up until a few decades ago most professional historians were not well schooled in either ecology or economics, and they seldom thought about their interaction. What they commonly taught about economics was partial and unsystematic. Being on the whole “progressives” in politics, they understood that “business” had made p ossible an enormous increase in national wealth along with intensified social costs, dislocation, and injustice. Assiduously they had combed through archives to tell the history of challenges to America‟s business civilization, the history of various refo rm movements. They had written plenty on the politics of regulation and control. But the parallel workings of that economic system in environmental terms—the story of human relationships with the natural world in contrast to relationships within society—had received little attention.Here again I had to wander away on my own to find the writings of great economic thinkers like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, or Max Weber, who could offer a more comprehensive understanding. This book opens with a bit of bravado--a quotation from Karl Marx on soil exploitation and capitalism. It was like opening a fundamentalist Sunday school class with a quotation from Charles Darwin! But I intended more than shock. Just as Darwin remains the single most important student of how the biological world works and changes over time, so Marx endures as our most profound analyst of how capitalism functions.I never intended, however, to offer a “Marxist” interpretation of Great Plains history, for after all Marx missed quite a few things and turned out to be a bad prophet. He tried to force history into a rigid framework of “dialectics” and class struggle. He ignored themoral and philosophical vision behind capitalism (a failure that Weber helped remedy). Above all he did not fully anticipate the ecological point of view that would emerge out of Darwinism. He came too early for that and was too absorbed in the plight of Europe‟s industrial workers to appreciate the massive environmental impact of the modern global economy. I found in Marx a flawed if profound economic analysis, and was left with the task of how one might integrate economic analysis into a new ecological sense of history.Achieving that integration was the purpose behind this book. Such a mission undoubtedly required a much longer work than this one is. I should have discussed more fully the natural science of grasslands—not only ecology, but climatology, soil physics, environmental geology, and hydrology--while at the same time giving a more thorough account of markets, technologies, and risk and investment strategies that had come to the prairies in the period immediately prior to the 1930s. Because of time constraints on a beginning professor‟s life, the book could not offer the full-blown synthesis that I sensed was required to start historians down a new path.This book did succeed in laying out a provocative (and, apparently for a few more hostile reviewers, a provoking) hypothesis that the causes of the Dust Bowl lay in economic invasion and destruction of grasslands. It did raise relatively new questions about how the modern market economy brought unprecedented environmental transformation, how it taught a new set of values toward the natural world, and how it not only deliberately risked capital for gain but also risked an already shaky ecological stability for short-term private advantage.2I was not alone in searching for a new history that would integrate the various “e” words. From this book and others such a history has emerged, an ambitious field ofstudy that we call “environmental history.” Far more than a mere sub-discipline, environmental history radically shifts our perspective to see the past as a constantly shifting relationship between people and the natural world, with immense social ramifications. Environmental history tells stories of how people have interacted with nature over time. By now the new history has worked its way into universities throughout the world, from Sweden to India to Panama, and my domestic and international colleagues are writing some of the most vital and path-breaking books of our time.As it has attracted a more diverse array of talent and imagination, environmental history has changed, as all fields inevitably do. Some of the change has been positive, some not so positive. Under pressure from social historians, with their procrustean demand that every past event be reduced to terms of ethnicity, class, and gender, environmental historians have responded by focusing more and more on cultural differences within society‟s environmental attitudes rather than on economic and ecological externalities and commonalties. Recently many scholars have become preoccupied with who defined what nature meant or whose environmental problems got noticed. Questions of social ju stice have tended to overshadow questions of our species‟ treatment of the earth. To a point, this has been good for environmental history, bringing us down from overly broad generalizations and abstractions about the causes of change while expanding our moral awareness.While writing about the Dust Bowl, I was aware of those social differences despite what might seem to be a very homogeneous population on the plains. Women and men, Hispanics and Anglos, Mennonites and other religious groups were all part of prairie life in the 1930s, creating a cultural mosaic that must be understood as a key part of theequation. All those groups faced the same tragedy, but it could affect them differently. Their different attitudes and their different positions within society could determine whether they left or stayed, whether they experienced the tragedy as farmers or as cowhands, as tenants or landowners, whether they had to fight blowing dust indoors or outdoors. The dirty thirties did not have the same outcome for everyone.Although few African Americans ever lived in the region‟s rural countryside, it was they who gave observers a name to apply to those who fled in poverty and desperation—one of the book‟s most important, if unwitting, paradoxes. A newspaper or two called the refugees of the 1930s “exodusters, ” probably not realizing where the name originated. Where the original “exodusters” had been former slaves leaving the South for prairie homesteads, in a spirit of hope, the new exodusters were overwhelmingly whites who had lost out on the prairie and were looking for a new promised land, farther west where no dust storms raged.3But focusing over much on racial and cultural matters can distract from the larger vision of environmental history. We must never again lose sight of the land itself, of its moral and material significance, its agency and influence; the land must stand at the core of the new history. Nor should we overlook or dismiss the truth claims of the natural sciences, out of misguided deconstructionism or multiculturalism that makes nature whatever any group says it is, for science is our indispensable ally in understanding the past in a fuller and more authoritative light. Nor, in writing the cultural history of ideas about nature, should we obscure the age-old dialogue between ecology and economy. I put that dialogue front and center in this book, for without it there is no new perspectiveon history—there is only an old history of human ideas, perceptions, and values colliding with other ideas.On the Great Plains of North America, this book argues, one of the modern world‟s defining clashes between ecology and economics occurred. It is still going on and will likely go on for a long while; in fact, such clashes may be said to be at the core of all human history. Twenty-five years after publication, what is the state of that clash in the old Dust Bowl, and what additional lessons can we learn from the recent past?The good news since 1979 is that grass, with the help of the federal government, has made a partial comeback. Six years after this book‟s publication, as a new round of erosion was threatening, Congress, in the Food Security Act, established a Conservation Reserve Program within the Department of Agriculture. It was intended for the entire nation, but particularly for the erosion-prone plains. It authorized USDA to make voluntary agreements with agricultural producers to protect environmentally sensitive land and defined the CRP‟s purposes as controlling soil erosio n, improving the quality of water, and enhancing wildlife habitat. To be eligible, lands must have been planted to an agricultural commodity by its owner during 4 of the previous 6 crop years, rate high on an erodibility index, and be located in a national or state conservation priority area (like the plains). The government rents the land from farmers for ten-year periods and helps re-establish native vegetation on it.The CRP program was established during the presidential administration of Ronald Reagan, whose fervor for ending government intervention in the market place seemingly knew no bounds. The CRP, nonetheless, is such an intervention. Even free-marketfundamentalists have come around to agree with pro-government planners (and this author) that aggressive farming must be controlled to prevent another thirties-style disaster. They have admitted that wind erosion is a human-caused problem and that its solution lies in grassland restoration on a large scale. The nation cannot, it is now agreed o n all sides, depend on the farmer‟s economic self-interest to bring back the grass or prevent erosion. Pragmatism has triumphed over ideology.Many have hailed the CRP as one of the most effective environmental improvement programs in American history. It has certainly been popular among farmers and ranchers as well as environmentalists. For fiscal year 2003, the government was authorized to enroll 53 million acres, an area more than half the size of the national park or national wildlife refuge system. But so large and popular a program comes with a huge price tag: billions of dollars in rental fees that must be kept high enough and secure enough to appeal to farmers in perpetuity. The CRP‟s chief weakness is that it leaves the private property and cash nexus intact.Farmers, it seems, must be paid by the government to do the ecologically rational and socially responsible thing. Regulation at any level, local or federal, is unacceptable. We may not think it right to pay factory owners to stop exploiting children or discriminating against people of color, but we accept the notion that farmers must be paid to do the right thing with the land. Conservation has thus become a new way to draw supplementary income out of the federal treasury.An alternat ive to the CRP‟s strategy of renting and restoring the sensitive lands of the Great Plains comes from a New Jersey husband-wife team, Frank and Deborah Popper. Touring the region as a federal land-use consultant in the 1970s, Frank concluded that thewhole history of frontier settlement had been a miscalculation, that people will never be able to get a secure hold in such a place. Forty years after the Dust Bowl, the region has not yet recovered in population levels or comparative income.4Subsequent da ta has tended to confirm the Popper‟s pessimism about the long-term future of the plains. From Texas to Canada, the region has been losing rural inhabitants for the past 70 years. And the region has not been, on the whole, keeping up with the rest of the country in prosperity. Nebraska now has 7 of the nation‟s 12 poorest counties. Cimarron County, Oklahoma (profiled in this book), has only 3000 residents today, compared to 5400 in 1930; it counts fewer than 2 people per square mile, the demographic standard that, in the late 19th century, historian Frederick Jackson Turner and geographer Henry Gannett used to designate the “unsettled” frontier. Take away federal aid which comes to the plains in the form of Social Security, farm subsidies, and drought assistance, and hundreds of western communities would soon collapse.To relieve the nation‟s taxpayers and save the plains residents from their stubborn downward spiral, the Poppers propose a massive program of “deprivatization,” taking 139,000 square miles out of private ownership—about a fourth of the region‟s 400 million acres, and more than double the acreage covered nationally by the CRP--and creating a permanent, and enormous, wildlife refuge. They call it “the Buffalo Commons.” Deer, antelope, bison, and elk would once more roam freely across a large part of the continent, and the native grasslands would once again reign supreme. Tourists would come and spend money to see the world‟s largest ecological restoration project, but the grandiose dream of turning all of the grasslands into an intense producer of food and wealth would vanish.Although controversial where the CRP has been popular, the Buffalo Commons is a more practical and less costly solution for the long term. That such an idea has even been proposed, that a debate has been raging over it, that increasingly plains residents are losing faith in traditional thinking, is more good news. The plains, like the nation, are in need of some bold ideas about how to live more carefully with nature for the longest time. The market economy will never find such ideas attractive, or make them possible, which is why government must take the lead.But what to do with the rest of the plains--those 300 million acres, more or less, where private ownership will continue to rule and where a more resilient agriculture and rural life must be found? How can we farm those lands without destroying them? Here again comes some good news in the form of bold proposals. Wes Jackson, a biologist and native Kansan, co-founder of the Land Institute, has proposed a fundamental changein how we think about agriculture. Since its invention thousands of years ago, farming has been primarily a work of tilling bare soil and planting annual seeds, hoping for rapid growth and a big harvest. While that may have been a safe enough practice on silt-rich floodplains with well-watered soils, it has been full of risk as farmers have moved elsewhere and created a global epidemic of erosion. We need a new model, Jackson argues, for raising food in those more demanding places.In 1980 (one year after this book appeared) Jackson published his New Roots for Agriculture in which he envisioned an agriculture based on evolutionary biology and ecology: “a polyculture of perennials.”5 The original prairie should serve as a model tobe imitated rather than an enemy to be destroyed. In its natural state a prairie can include dozens or even hundreds of plant species, some well adapted to drought, others fertilizingthe soil by fixing nitrogen, others emitting chemical protection from voracious insects. Mostly, those plants are perennials that last for years before offspring take their place. Where the conventional farmer buys a single variety of seed every year, plows and plants on an annual cycle, and expends much human labor and fossil fuel energy in order to raise a crop, nature follows a different strategy. Agriculturists would do well to learn from those natural processes, to try to imitate the prairie.It will take at least another half century, the Land Institute admits, to perfect a new agriculture based on nature‟s wisdom. Scientists need to identify which native plants have the highest protein yield, then help those plants improve with selective breeding, then learn to grow them together in a mimic prairie, then figure out how to harvest that newfangled crop and turn it into foodstuffs. More recently, Jackson and his fellow plant breeders have pursued a near-term strategy of perennializing major grain crops like wheat and sorghum. They are going back to the time when those plants were wild grasses and trying to recover the natural resilience that has been bred out of them over the centuries.Here again is a remedy for the plains that market economics will not pursue. All-out production of the most immediately profitable crops is what capitalism, agricultural or industrial, knows how to do, while investing in scientific research and developing a futuristic farming based on ecology and evolution get no takers. Even the land-grant colleges and the Department of Agriculture, fixed as they are on maximizing commodity production, have shown little interest in a radical shift toward natural-systems agriculture. But the good news is that, for the first time since Americans began to show up with their railroads, grain elevators, and plows, the region can dare to dream about revolutionary possibilities. One day, if the Land Institute is successful, we may witness a Great Plainswhere native flora and flora flourish as they once did, through good years and bad, while applied ecologists show farmers how to raise food on what looks like a prairie.Contrasting with these new approaches to the Plains based on ecological science is another vision pursued by agribusiness over the past quarter-century. It amounts to an intensification of the same attitudes that gave us the original Dust Bowl. Immense wealth has accumulated in a few hands through this vision, but almost everyone realizes that it cannot endure indefinitely, that a crash—or at least an end--is some day coming.Standing at the dead center of that entrepreneurial agriculture on the southern plains is the beef cow. Once a land of longhorns, Herefords, and Angus roaming across a native prairie, replacing the extinguished bison, much of the region has been transformed into industrial meat production. Cattle are imported from all directions and confined in vast feedlots where they are fed on grains raised by irrigation. Once fattened up, they travel to massive slaughterhouses (or in curr ent sanitized parlance, “processing plants”) where they are cut up for the steaks and hamburgers that Americans consume by the billions. Increasingly, hogs have become part of the same meat factory. They are gathered into “confinement” facilities where t hey live out their lives under artificial light and are pumped up with feed and antibiotics. Chicago, Omaha, and Kansas City no longer do the work of killing and packaging the nation‟s meat supply; the southern plains have taken on the bloody job.Dodge City, where television marshal Matt Dillon once stood at the bar of the Long Branch saloon chatting up the barmaid Kitty, is now the site of three gargantuan feedlots. Their proud achievements are emblazoned on a roadside sign east of town, looking down on a bovine metropolis of 60,000. Each cow in that metropolis gets 140 days ofresidency to reach a weight of 1,100 pounds. Half of that bulk is edible meat. By-products include pharmaceuticals, leather goods, cosmetics, animal feeds, photographic film, and fertilizers. Together, the Excel and National Beef companies fatten enough animals to feed 16 million people a year. They have helped make the state of Kansas the nation‟s leader in commercial cattle production.A thousand cattle trucks load up animals each day and transport them farther west to the outskirts of Garden City. Here, the multinational corporations ConAgra and Iowa Beef (the latter owned by Tyson Foods) slaughter 9500 animals every 24 hours. The surrounding county has even more capacity than Dodge City--12 feedlots with a capacity to feed over 284,000 head of cattle. Those animals consume annually over 300 million bushels of feed grains and nearly a million tons of hay.The Kansas cattle industry, most of it concentrated on the semi-arid plains, alone generates over $4 billion a year. Add in the adjoining states and the Texas panhandle, and one begins to get an idea of just how far this vision of the region as meat factory has gone. Some of its cash receipts stay in local hands, making Garden City and its hinterland a boom country. Finney County‟s population increased by 22.5% from 1990 to 2000, almost 3 times the state average. But then when one examines the distribution of that wealth derived from meat, the reality is not so rosy. In 1999, the county‟s median household income was below the state average, while the percentage of persons below the poverty line was substantially above the state average (14.2% versus 9.9%). Obviously, most of the money leaves the county and leaves the state, going to corporate headquarters in Arkansas, Nebraska, and beyond.6The growth of a new-era cattle kingdom on the plains has attracted job seekers from distant places. For a while the work force in the beef processing industry was heavily Vietna mese; but this is tough, dangerous work (meatpacking has one of industry‟s worst personal injuries records), and the Vietnamese have quickly moved out of the processing plants, leaving a work force mainly made up of Hispanics who are hungry for employment. In the latest census nearly half of Finney County‟s population was of Hispanic or Latino origin; in nearby Haskell County (profiled in this book), it was one-quarter.7However one calculates its economic pluses and minuses, the feedlot-beef processing enterprise has a tremendous need for natural resources and a tremendous impact on its environment. Above all, it must have water and lots of it. The animals require water to drink, but even more the farmers who grow their feed need water for irrigation. Dryland farming could never support the scale of meat production now found on the southern plains. So agriculturists have found that needed abundance underground, in deep wells as I briefly discussed in the original edition of this book, and water pumping has now become ubiquitous. The entire horizon of southwestern Kansas is crawling with center-pivot irrigation rigs that resemble huge segmented insects making great circles on the ground. The crops they irrigate from their drip hoses are mainly corn, sorghum, and alfalfa, while winter wheat has diminished in acreage, being far less profitable or usable as cattle feed.As farmers have tapped every drop of groundwater in the riparian zone, the flow of virtually every stream or river in western Kansas has dried up. There is less surface water here today than when it was first labeled the Great American Desert. Farmers havepunched down into the High Plains aquifer, which includes the Ogallala aquifer, extending under eight states in the Great Plains; this source supplies 70 percent of the water used by Kansans each day. Some parts of that aquifer have been practically depleted; others have lots of water remaining, but it is not easy to determine how much longer the supply will last. Out of hundreds of thousands of wells drilled into the aquifer, we collect data on water levels in only about 9500. Moreover, the rate of withdrawal is not fixed, but varies with the price of fuel and farm commodities and with the amount of surface precipitation. Moreover, as the plains face a future of global warming, when annual precipitation is likely to fall and droughts become more frequent and severe, the supplies for irrigation will go down rapidly.8 Some areas might have 100 years of water left if current rates of withdrawal could be maintained, others fewer than 25 years—but then who can say what demands the future will bring?9Like the fabled copper and gold fields of the American West, the livestock industry that dominates the Great Plains today is a mining economy. It extracts meat instead of ore. Like all mining economies, its end will inevitably be ghost towns, abandoned houses, derelict farms, and bankrupt businesses. Then, when there is little or no water left to grow crops, when the cycle has come full circle, will the dust begin to blow? It always has in the past. There is the bad news that we must put alongside the good.In the Darwinian world of nature, the fittest are supposed to survive, but it is never easy to determine who or what is the most fit. Will capitalism prove to be the fittest, or will something else? Will natural-systems agriculture or the feedlot industry, Hispanics or Anglos, buffalo grass or sorghum? A mere century or two of American domination of the plains is not an adequate base for making any predictions about the long-term survival。

Democracy in AmericaFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaDemocracy in AmericaAuthor Alex de TocquevilleOriginal title De la démocratie en AmériquePublisher Saunders and Otley (London), Now in public domainPublication date 1835-1840This article is about the book written by Tocqueville. For the actual system of government used in the United States, see Politics of the United States.De la démocratie en Amérique (published in two volumes, the first in 1835 and the second in 1840) is a classic French text by Alexis de Tocqueville on the democratic institution of the United States in the 1830s and its strengths and weaknesses. A literal translation of its title is On Democracy in America, but the usual translation of the title is simply Democracy in America. It is regarded as a classic account of the democratic system of the United States and has been used as an important reference ever since. The work is regarded as a seminal text in economics and a key work in the foundation of economic sociology.In 1831, twenty-five year-old Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont were sent by the French government to study the American prison system. They arrived in New York City in May of that year and spent nine months traveling the United States, taking notes not only on prisons, but on all aspects of American society including the nation's economy and its political system. The two also briefly visited Canada, spending a few days in the summer of 1831 in what was then Lower Canada (modern-day Quebec) and Upper Canada (modern-day Ontario).After they returned to France in February 1832, Tocqueville and Beaumont submitted their report, entitled Du système pénitentiaire aux États-Unis et de son application en France, in 1833. When the first edition was published, Beaumont, sympathetic to social injustice, was working on another book, Marie, ou l'esclavage aux Etats-Unis (two volumes, 1835), a social critique and novel describing the separation of races in a moral society and the conditions of slaves in America.Contents [hide]1 Summary2 Importance3 Notes4 See also5 Bibliography6 External linksSummaryThe primary focus of Democracy in America is an analysis of why republican representative democracy has succeeded in the United States while failing in so many other places. He seeks to apply the functional aspects of democracy in America to what he sees as the failings of democracy in his native France.Tocqueville speculates on the future of democracy in the United States, discussing possible threats to democracy and possible dangers of democracy. These include his belief that democracy has a tendency to degenerate into "soft despotism" as well as the risk of developing a tyranny of the majority. He observed that the strong role religion played in the United States was due to its separation from the government, a separation all parties found agreeable. He contrasts this to France where there was whathe perceived to be an unhealthy antagonism between democrats and the religious, which he relates to the connection between church and state.Insightful analysis of political society was supplemented in the second volume by description of civil society as a sphere of private and civilian affairs[1]. the Second Book, published in 1840, is considered as a reference in sociology , but, some of its developments underline a Republican influence: because of his study of political freedom and individualism, Tocqueville's thought contains elements of republican Debate, particularly about the place of human being in political and civil society. his analysis of the virtue prooves a potential connection with civic humanism[2].Tocqueville's views on America took a darker turn after 1840 however, as made evident in Aurelian Craiutu's "Tocqueville on America after 1840: Letters and Other Writings".ImportanceDemocracy in America was published in numerous editions in the 19th century. It was immediately popular in both Europe and the United States, while also having a profound impact on the French population. By the twentieth century, it had become a classic work of political science, social science, and history. It is a commonly assigned reading for undergraduates of U.S.A. universities majoring in the political or social sciences.Tocqueville's work is often acclaimed for making a number of predictions which were eventually borne out. Tocqueville correctly anticipates the potential of the debate over the abolition of slavery to tear apart the United States (as it indeed did in the American Civil War). On the other hand, he predicts that any part of the Union would be able to declare independence. He also predicts the rise of the United States and Russia as rival superpowers (which they did become after World War II with Russia as the central component of the Soviet Union.)American democracy was seen to have its potential downside: the despotism of public opinion, the tyranny of the majority, conformity for the purpose of seeking material security, the absence of intellectual freedom which he saw to degrade administration and bring statesmanship, learning, and literature to the level of the lowest. Democracy in America predicted the violence of party spirit and the judgment of the wise subordinated to the prejudices of the ignorant.[edit]Notes--------------------------------------------------------PuritanFrom Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia(Redirected from Puritans)This article is about the religious movement. For other uses, see Puritan (disambiguation).Gallery of famous seventeenth-century Puritan theologians: Thomas Gouge, William Bridge, Thomas Manton, John Flavel, Richard Sibbes, Stephen Charnock, William Bates, John Owen, John Howe, Richard Baxter.The Puritans were a significant grouping of English-speaking Protestants in the 16th and 17th-century. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1559, as an activist movement within the Church of England. They were blocked from changing the system from within, but their views were taken by the emigration of congregations to the Netherlands and later New England, and by evangelical clergy to Ireland and later into Wales, and were spread into lay society by preaching and parts of the educational system, particularly certain colleges of the University of Cambridge. Puritans were mainly concerned withreligious matters, and took on distinctive views on clerical dress and in opposition to the episcopal system, particularly after the 1619 conclusions of the Synod of Dort were resisted by the English bishops. They largely adopted sabbatarian views in the 17th century, and were influenced by millenialism. In alliance with the growing commercial world, the parliamentary opposition to the royal prerogative, and in the late 1630s with the Scottish Presbyterians with whom they had much in common, the Puritans became a major political force in England and came to power as a result of the First English Civil War. After the English Restoration of 1660 and the 1662 Uniformity Act, almost all Puritan clergy left the Church of England, some becoming nonconformist ministers, and the nature of the movement in England changed radically, though it retained its character for much longer in New England.Puritans by definition felt that the English Reformation had not gone far enough, and that the Church of England was tolerant of practices which they associated with the Catholic Church. They formed into various religious groups advocating for greater "purity" of worship and doctrine, as well as personal and group piety. Puritans adopted a Reformed theology and in that sense were Calvinists (as many of their opponents were, also), but also took note of radical views critical of Zwingli in Zurich and Calvin in Geneva. In church polity, some advocated for separation from all other Christians, in favor of autonomous gathered churches, and these separatist and independent strands of Puritanism became significant in the 1640s, when the supporters of a presbyterian polity in the Westminster Assembly were unable to forge a new English national church.The designation "Puritan" is often expanded to mean any conservative Protestant, or even more broadly, to evangelicals. The word "Puritan" was originally an alternate term for "Cathar" and was a pejorative term used to characterize them as extremists similar to the Cathari of France. Some scholars use the term precisianist in regard to the historical groups of England and New England.[1]Contents [hide]1 Background1.1 Elizabethan and Jacobean Puritanism1.2 Conflict within the Church of England under Charles I1.3 Fragmentation1.4 Great Ejection and Dissenters2 Terminology3 Scholarly debates4 Beliefs5 Cultural consequences6 Social consequences6.1 Puritan family life6.2 The home in New England6.3 Education in New England6.4 Restriction and individualism6.5 The Puritan spirit in the United States7 See also8 Notes9 ReferencesBackgroundMain article: History of the PuritansThe movement that was later identified by the name "Puritan" can be traced back[citation needed] to theAnabaptists of continental Europe, although the term itself was not coined until the 1560s, when it appears as a term of abuse for those who found the Elizabethan Religious Settlement of 1559 inadequate. Throughout the reign of Elizabeth I, the Puritan movement involved both a political and a social component. Politically, the movement attempted, mostly unsuccessfully, to have Parliament pass legislation to replace episcopacy with a congregational form of church governance, and to alter the Book of Common Prayer.Elizabethan and Jacobean PuritanismBy the end of Elizabeth's reign, the Puritans constituted a self-defined group within the Church of England who regarded themselves as the godly; they held out little hope for those who remained attached to "popish superstitions" and worldliness. Most Puritans were non-Separating Puritans who remained within the Church of England, and Separating Puritans or Separatists who left the Church of England altogether were numerically much fewer. Although the Puritan movement was subjected to repression by some of the bishops, other bishops were more tolerant, and in many places, individual ministers were able to omit disliked portions of the Book of Common Prayer.Puritanism was fundamentally anti-Catholic: Puritans felt that the Church of England was still too close to Catholicism and needed to be reformed further. During the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585 to 1604, anti-Catholicism agreed with English government policy. The accession of King James I of England brought the Millenary Petition, a Puritan manifesto of 1603 for reform of the English church, but James wanted a new religious settlement along different lines. He called the Hampton Court Conference in 1604, and heard the views of four prominent Puritan leaders there, but largely sided with his bishops. Well informed by his education and Scottish upbringing on theological matters, he dealt shortly with the peevish legacy of Elizabethan Puritanism, and tried to pursue an eirenic religious policy in which he was arbiter. Many of his episcopal appointments were Calvinists.The Puritan movement of Jacobean times was distinctive from the rest of the church: in theology that was more prescriptive[jargon] than broad Calvinism, in legalism, theonomy, and especially congregationalism. Puritans still opposed much of the Catholic summations in the Church of England, notably the Book of Common Prayer, but also the use of non-secular vestments (cap and gown) during services, the use of the Holy Cross during baptism, and kneeling during the sacrament.[2] Puritans rejected anything they thought was reminiscent of the Pope, and many of the non-secular rituals preserved by the Church of England were not only considered to be objectionable, but were believed to put one's immortal soul in peril.[edit]Conflict within the Church of England under Charles IJames I was succeeded by his son Charles I of England in 1625. In the year before becoming King, he married Henrietta-Marie de Bourbon of France, a Roman Catholic daughter of the convert Henry IV of France, who refused to attend the coronation of her husband in a non-Catholic cathedral.[3] She had no tolerance for Puritans. At the same time, William Laud, Bishop of London, was becoming increasingly powerful as an advisor to Charles. Laud viewed Puritans as a schismatic threat to orthodoxy in the church. With the Queen and Laud among his closest advisors, Charles pursued policies to eliminate the religious distinctiveness of Puritans in England. Charles was determined to eliminate the "excesses" of Puritanism from the Church of England. His close advisor Laud became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633, and moved the Church of England away from Puritanism, rigorously enforcing the law against ministers who deviated from the Book of Common Prayer or who violated the ban on preaching about predestination.The Mayflower, which transported Pilgrims to the New World. During the first winter at Plymouth,about half of the Pilgrims died.[4]Charles relied largely on the Star Chamber and Court of High Commission to implement his policies. Charles adapted them as instruments to suppress the Puritans, following the later juristic methods of Elizabeth I. They were courts under the control of the King, not the Parliament, and were therefore capable of convicting and imprisoning those guilty of displeasing the King.[5] The Puritan movement in England allied itself with the cause of "England's ancient liberties"; the unpopularity of Laud and the suppression of Puritanism was a major factor leading to the English Civil War, during which Puritans formed the backbone of the parliamentarian forces. Laud was arrested in 1641 and executed in 1645, after a lengthy trial in which a large mass of evidence was brought, tending to represent him as obstructive of the "godly" and amounting to the whole, detailed Puritan case against the royal church policy of the preceding decade.[edit]FragmentationA plate depicting the Trial of Charles I on 4 January 1649.The Puritan movement in England was riven over decades by emigration and inconsistent interpretations of Scripture, and some political differences that then surfaced. The Westminster Assembly was called in 1643. Doctrinally, the Assembly was able to agree to the Westminster Confession of Faith, a consistent Reformed theological position. While its content was orthodox, many Puritans would have rejected portions of it. The Westminster Divines were, on the other hand, divided over questions of church polity, and split into factions supporting a reformed episcopacy, presbyterianism, congregationalism, and Erastianism.The Directory of Public Worship was made official in 1645, and the larger framework now called the Westminster Standards was adopted for the Church of England (reversed in 1660).[clarification needed][citation needed] Although the membership of the Assembly was heavily weighted towards the presbyterians, Oliver Cromwell was a Congregationalist separatist who imposed his views. The Church of England of the Interregnum was run as a presbyterian ministry, but never became a national presbyterian church such as existed in Scotland, and England was not the theocratic state leading Puritans had called for as "godly rule".[6][edit]Great Ejection and DissentersAt the time of the English Restoration (1660), the Savoy Conference was called to determine a new religious settlement for England and Wales. With only minor changes, the Church of England was restored to its pre-Civil War constitution under the Act of Uniformity 1662, and the Puritans found themselves sidelined. A tradional estimate of the historian Calamy is that around 2,400 Puritan clergy left the Church, in the "Great Ejection" of 1662.[7] At this point, the term Dissenter came to include "Puritan", but more accurately describes those (clergy or lay) who "dissented" from the 1662 Book of Common Prayer.[citation needed]Dividing themselves from all Christians in the Church of England, the Dissenters established their own separatist congregations in the 1660s and 1670s; an estimated 1,800 of the ejected clergy continued in some fashion as ministers of religion (according to Richard Baxter).[7] The government initially attempted to suppress these schismatic organizations by the Clarendon Code. There followed a period in which schemes of "comprehension" were proposed, under which presbyterians could be brought back into the Church of England; nothing resulted from them. The Whigs, opposing the court religious policies, argued that the Dissenters should be allowed to worship in schism from the body of Christ, and this position ultimately prevailed when the Toleration Act was passed in the wake of the Glorious Revolution (1689). As a result, a number of schismatic individuals were legally tolerated in the 1690s.The term Nonconformist generally replaced the term "Dissenter" from the middle of the eighteenth century.[edit]TerminologyOriginally used to describe a third-century sect of strictly legalistic heretics, the word "Puritan" is now applied unevenly to a number of Protestant churches (and religious groups within the Anglican Church) from the late 16th century to the present. Puritans did not originally use the term for themselves. It was a term of abuse that first surfaced in the 1560s. "Precisemen" and "Precisians" were other early antagonistic terms for Puritans who preferred to call themselves "the godly." The word "Puritan" thus always referred to a type of religious belief, rather than a particular religious sect. To reflect that the term encompasses a variety of ecclesiastical bodies and theological positions, scholars today increasingly prefer to use the term as a common noun or adjective: "puritan" rather than "Puritan."[citation needed]The single theological momentum most consistently defined by the term "Puritan" was Anabaptist and led to the founding of the Independent or Congregationalist churches; In the United States, the church and religious culture of the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony formed the basis of post-colonial American Congregationalism, specifically the Congregational Church proper as well as Unitarianism.[citation needed] The term Puritan was used by the group itself mainly in the 16th century, though it seems to have been used often and, in its earliest recorded instances, as a term of abuse. By the middle of the 17th century, the group had become so divided that "Puritan" was most often used by opponents and detractors of the group, rather than by the practitioners themselves. As Patrick Collinson has noted, well before the founding of the New England settlement, "Puritanism had no content beyond what was attributed to it by its opponents."[8] The practitioners knew themselves as members of particular churches or movements, and not by the simple term.Puritans who felt that the Reformation of the Church of England was not to their satisfaction but who remained within the Church of England advocating further reforms are known as non-separating Puritans. (The Non-Separating Puritans differed among themselves about how much further reformation was necessary.) Those who felt that the Church of England was so corrupt that true Christians should separate from it altogether are known as separating Puritans or simply as Separatists. Especially after the Restoration (1660), non-separating Puritans were called Nonconformists (for their failure to conform to the Book of Common Prayer) while separating Puritans were called Dissenters.The term "puritan" is not strictly used to describe any new religious group after the 17th century, although several groups might be called "puritan" because their origins lay in the Puritan movement. The term "puritan" might be used by analogy (usually unfavorably) to describe any group that shares a commitment to the Puritans' Anabaptist points of view.[edit]Scholarly debatesThe literature on Puritans, particularly biographical literature on individual Puritan ministers, became large already in the 17th century, and indeed the interests of Puritans in the narratives of early life and conversions made the recording of the internal lives important to them. The historical literature on Puritans is, however quite problematic and subject to controversies of interpretation. The great interest of authors of the 19th century in Puritan figures was routinely accused in the 20th century of consisting of anachronism and the reading back of contemporary concerns. The national context (England and Wales, plus the kingdoms of Scotland and Ireland) frames the definition of Puritans, but was not a self-identification for Protestants who saw the progress of the Thirty Years War from 1620 as directly bearing on their denomination, and as a continuation of the religious wars of the previous century,carried on by the English Civil Wars. The analysis of "mainstream Puritanism" in terms of the evolution from it of separatist and antinomian groups that did not flourish, and others that continue to this day such as Baptists and Quakers, risks an incoherent view of where the burden of belief lay for the "godly". Puritans were politically important in England, but it is debated whether the movement was in any way a party with policies and leaders before the early 1640s; and Puritanism in New England was important culturally for a group of colonial pioneers in America, but there have been many studies trying to pin down exactly what the identifiable cultural component was. Fundamentally, historians remain dissatisfied with the grouping as "Puritan" as a working concept for historical explanation. The conception of a Protestant work ethic, identified more closely with Calvinist or Puritan principles, has been criticised at its root, mainly as a post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy aligning economic success with a narrow religious scheme.[edit]BeliefsPuritan teaching called for a commitment to Jesus Christ, for greater personal holiness. There were substantial works of theology written by Puritans, such as the Medulla Theologiae of William Ames, but there is no theology that is distinctive of Puritans. "Puritan theology" makes sense only as certain parts of Reformed theology, i.e. the legacy in theological terms of Calvinism, as it was expounded by Puritan preachers (often known as lecturers), and applied in the lives of Puritans. Various strands of Calvinist thought of the 17th century were adopted by different parts of the Puritan movement, and in particular Amyraldism was adopted by some influential figures. In the same way, there is no theory of church polity that is uniquely Puritan, and views differed. Some approved of the existing church hierarchy with bishops, but others sought to reform the Episcopal churches on the Presbyterian model. Some separatist Puritans were Presbyterian, but most were Congregationalists. The idea of personal Biblical interpretation, while central to Puritan beliefs, was shared with Protestants in general.The central tenet of Calvinism was God's supreme authority over human affairs, particularly in the church, and especially as expressed in the Bible. Puritans therefore sought both individual and corporate conformity to the teaching of the Bible, with moral purity pursued both down to the smallest detail as well as ecclesiastical purity to the highest level. They believed that man existed for the glory of God; that his first concern in life was to do God's will and so to receive future happiness.[9] On the individual level, Calvinists emphasized that each person should be continually reformed by the grace of God to fight against indwelling sin and do what is right before God. A humble and obedient life would arise for every Christian.Calvinists studied the earlier Church fathers and quoted them against later developments of the Roman tradition. Chrysostom, a favorite of the Calvinists, spoke eloquently against drama and other worldly endeavors, and the Puritans adopted his view when decrying the culture of England, plays and bawdy city entertainments.At the level of the church body, Calvinists believed that the worship in the church ought to be strictly regulated by what is commanded in the Bible (the regulative principle of worship). Calvinists condemned as idolatry many worship practices, regardless of antiquity or widespread adoption among Christians, against opponents who defended wtradition. Like some of Reformed churches on the European continent, Puritan reforms were typified by a minimum of ritual and decoration and by an unambiguous emphasis on preaching. Simplicity in worship led to the exclusion of vestments, images, candles, etc. They did not celebrate traditional holidays which they believed to be in violation of the regulative principle.Puritans opposed the supremacy of the monarch in the church (Erastianism), and argued that the onlyhead of the Church in heaven or earth is Christ. They believed that secular governors are accountable to God (not through the church, but alongside it) to protect and reward virtue, including "true religion", and to punish wrongdoers — a policy that is better described as non-interference rather than separation of church and state. The separating Congregationalists, a radicla segment of the Puritan movement, believed the Divine Right of Kings was heresy.Other notable beliefs of Calvinists included the priesthood of all believers, and that the observance of the Sabbath was still obligatory for Christians, although they generally believed the Sabbath had been changed to Sunday. Puritans believed Satan was of the netherworld, but Puritan pastors undertook exorcisms in some high-profile cases, wrote extensively and in alarmist fashion against heresy (for example in Gangraena), and believed in some allegations of witchcraft.[edit]Cultural consequencesFor more details on this topic, see Puritan recreation.Puritans eliminated the use of musical instruments in their religious services, for theological and practical reasons. Outside of church, however, Calvinists encouraged music in certain ways.There was a desire to see education and enlightenment for the masses (especially so they could read the Bible for themselves). In addition to promoting lay education, Calvinists wanted to have knowledgeable, educated pastors, who could read the Bible in its original languages of Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic, as well as church tradition and scholarly works, which were most commonly written in Latin. Most of their leading divines undertook studies at the University of Oxford or the University of Cambridge before seeking ordination.Diversions for the educated included discussing the Bible and its practical applications as well as reading the classics such as Cicero, Virgil, and Ovid. They also encouraged the composition of poetry that was of a religious nature, though they eschewed religious-erotic poetry except for the Song of Solomon. This they considered magnificent poetry, without error, regulative for their sexual pleasure, and, especially, as an allegory of Christ and the Church.[edit]Social consequencesParticularly in the years after 1630, Puritans left for New England (see Migration to New England (1620–1640)), supporting the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and other settlements. The large-scale Puritan emigration to New England then ceased, by 1641, with around 21,000 having moved across the Atlantic. This English-speaking population in America did not all consist of colonists, since many returned, but produced more than 16 million descendants by 1988.[10][11] This so-called "Great Migration" is not so named because of sheer numbers, which were much less than the number of English citizens who emigrated to Virginia and the Caribbean during this time.[12] The rapid growth of the New England colonies (~700,000 by 1790) was almost entirely due to the high birth rate and lower death rate per year.Puritan culture emphasized the need for self-examination and the strict accounting for one‘s feelings as well as one‘s deeds. This was the center of evangelical experience, which women in turn placed at the heart of their work to sustain family life. The words of the Bible, as they interpreted them, were the origin of many Puritan cultural ideals, especially regarding the roles of men and women in the community. While both sexes carried the stain of original sin, for a girl, original sin suggested more than the roster of Puritan character flaws. Eve‘s corruption, in Puritan eyes, extended to all women, and justified marginalizing them within churches' hierarchical structures. An example is the different ways that men and women were made to express their conversion experiences. For full membership, the Puritan church insisted not only that its congregants lead godly lives and exhibit a clear understanding of。