1985年巴菲特给股东的信(英文原版)

- 格式:docx

- 大小:57.89 KB

- 文档页数:32

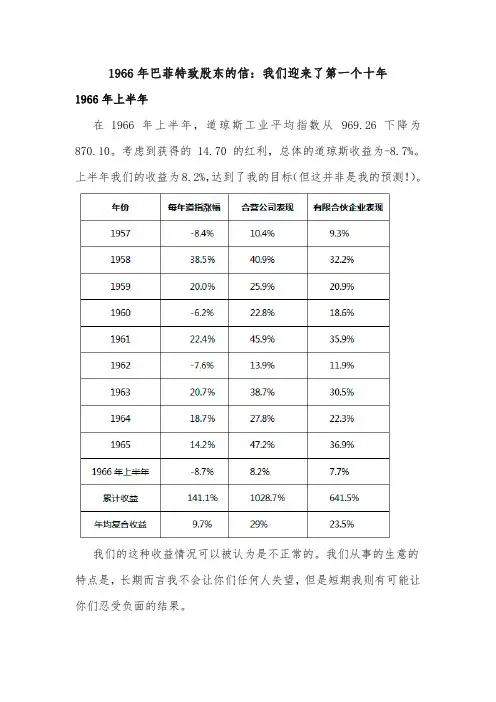

1966年巴菲特致股东的信:我们迎来了第一个十年1966年上半年在1966 年上半年,道琼斯工业平均指数从 969.26 下降为870.10。

考虑到获得的 14.70 的红利,总体的道琼斯收益为-8.7%。

上半年我们的收益为8.2%,达到了我的目标(但这并非是我的预测!)。

我们的这种收益情况可以被认为是不正常的。

我们从事的生意的特点是,长期而言我不会让你们任何人失望,但是短期我则有可能让你们忍受负面的结果。

在上半年我们以及两位在企业中拥有10%股份的合伙人联手买下了 Hochschild,Kohn&Co的全部股份。

这是一家巴尔的摩的私人百货公司。

这是我们合伙企业第一次以谈判的方式买下整个生意。

虽然如此,买入的原则并没有任何改变。

对该生意价格的定量和定性的衡量都照常进行,并严格按照与其它投资机会同样的准绳进行了估价。

HK(以后就这样叫它,因为我也是直到交易完成后才知道该公司的确切发音)从各个方面满足了我们的要求。

无论是从生意还是私人交往的角度来说,我们都拥有一流的人才来打理这桩生意。

如果没有优异的管理,即便价格更加便宜,我们也不见得会买下这个生意。

当一个拥有数千名雇员的生意被售出时,想要不吸引一定的公众注意是不可能的。

然而希望你们不要以公众新闻的报道来推断该生意对合伙企业的影响。

我们有超过五千万美元的投资,绝大部分都投资在二级市场上,而HK 的投资只占了我们净投资额的不到 10%。

在对于二级市场的投资部分,我们对于某只证券的投资超过了我们对 HK 投资额度的三倍还多,但是这项投资却不会引起公众的注意。

这并不是说对于 HK 的投资就不重要,它占我们投资额10%比例就说明它对我们而言是一项重要的投资。

但是总体而言它只是我们全部的投资的冰山一角而已。

到年底我准备用购买成本加上自购买后它产生的盈余作为我们对它的估值。

这项评估方法将一直被执行,除非未来发生新的变化。

自然地,如果不是因为一个吸引人的价格,我们是不会买入HK 的。

Warren Buffett's Letters to Berkshire Shareholders-1977BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC.To the Stockholders of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.:Operating earnings in 1977 of $21,904,000, or $22.54 per share, were moderately better than anticipated a year ago. Of these earnings, $1.43 per share resulted from substantial realizedcapital gains by Blue Chip Stamps which, to the extent of our proportional interest in that company, are included in ouroperating earnings figure. Capital gains or losses realizeddirectly by Berkshire Hathaway Inc. or its insurance subsidiaries are not included in our calculation of operating earnings.Whiletoo much attention should not be paid to the figure for any single year, over the longer term the record regarding aggregate capital gains or losses obviously is of significance.1977年本公司的营业净利为2,190万美元,每股约当22.54美元,表现较年前的预期稍微好一点,在这些盈余中,每股有1.43美元的盈余,系蓝筹邮票大量实现的资本利得,本公司依照投资比例认列投资收益所贡献,至于伯克希尔本身及其保险子公司已实现的资本利得或损失,则不列入营业利益计算,建议大家不必太在意单一期间的盈余数字,因为长期累积的资本利得或损失才是真正的重点所在。

Buffett’s Letters To Berkshire Shareholders 1991巴菲特致股东的信1991年Our gain in net worth during 1991 was $2.1 billion, or 39.6%. Over the last 27 years (that is, since present management took over) our per-share book value has grown from $19 to $6,437, or at a rate of 23.7% compounded annually.1991年本公司的净值成长了21亿美元,较去年增加了39.6%,而总计过去27年以来,也就是自从现有经营阶层接手之后,每股净值从19元成长到现在的6,437美元,年复合成长率约为23.7%。

The size of our equity capital -which now totals $7.4 billion - makes it certain that we cannot maintain our past rate of gain or, for that matter, come close to doing so. As Berkshire grows, the universe of opportunities that can significantly influence the company's performance constantly shrinks. When we were working with capital of $20 million, an idea or business producing $1 million of profit added five percentage points to our return for the year. Now we need a $370 million idea (i.e., one contributing over $550 million of pre-tax profit) to achieve the same result. And there are many more ways to make $1 million than to make $370 million. 现在我们股东权益的资金规模已高达74亿美元,所以可以确定的是,我们可能再也无法像过去那样继续维持高成长,而随着伯克希尔不断地成长,世上所存可以大幅影响本公司表现的机会也就越来越少。

1957年巴菲特致股东信我认为目前市场的价格水平超越了其内在价值,这种情况主要反映在蓝筹股上。

如果这种观点正确,则意味着市场将来会有所下跌——价格水平届时将被低估。

虽然如此,我亦同时认为目前市场的价格水平仍然会低于从现在算起五年之后的水平。

即便一个完整的熊市也不见得会对内在价值造成伤害。

如果市场的价格水平被低估,我们的投资头寸将会增加,甚至不排除使用财务杠杆。

反之我们的头寸将会减少,因为价格的上涨将实现利润,同时增加我们投资组合的绝对量。

所有上述的言论并不意味着对于市场的分析是我的首要工作,我的主要动机是为了让自己能够随时发现那些可能存在的,被低估的股票。

笔记:1.不预测市场未来走势,努力研究企业内在价值2.价格低估时加大买入;价格高估时持有或卖出1958年巴菲特致股东信在去年的信中,我写到“我认为目前市场的价格水平超越了其内在价值,这种情况主要反映在蓝筹股上。

如果这种观点正确,则意味着市场将来会有所下跌——价格水平届时将被低估。

虽然如此,我亦同时认为目前市场的价格水平仍然会低于从现在算起五年之后的水平。

即便一个完整的熊市也不见得会对市场价值的固有水平造成伤害。

”“如果市场的价格水平被低估,我们的投资头寸将会增加,甚至不排除使用财务杠杆。

反之我们的头寸将会减少,因为价格的上涨将实现利润,同时增加我们投资组合的绝对量。

”“所有上述的言论并不意味着对于市场的分析是我的首要工作,我的主要动机是为了让自己能够随时发现那些可能存在的,被低估的股票。

”去年,股票的价格水平稍有下降。

我之所以强调“稍有下降”,是因为那些在近期才对股票有感觉的人会认为股票的价格下降的很厉害。

事实上我认为,相对股票价格的下降,上市公司的盈利水平下降的程度更快一些。

换句话说,目前投资者仍然对于大盘蓝筹股过于乐观。

我并没有想要预测未来市场走势或者是上市公司的盈利水平的意思,只是想要在此说明市场并未出现所谓的大幅下降,同时投资价值也仍然未被低估。

巴菲特给股东的信英文版Dear Shareholders,I wanted to take this opportunity to update you on the current state of Berkshire Hathaway and provide some insights into our recent activities.Firstly, I am pleased to report that 2020 was another successful year for Berkshire Hathaway, despite the challenges brought about by the global pandemic. Our net earnings for the year were $42.5 billion, and our operating earnings were $21.9 billion. This success was largely driven by the outstanding performance of our operating businesses, as well as the improving market conditions.Our insurance subsidiaries, in particular, had an exceptional year. Both GEICO and Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance Group reported strong results, and we are confident in the long-term prospects of these businesses.In addition to our operating businesses, we also made several significant investments during the year. Some of the notable investments include a substantial purchase of Apple stock, as well as new investments in Verizon Communications and Chevron Corporation. We believe that these investments align with our long-term financial goals and will continue to generate value for our shareholders in the years to come.In terms of capital allocation, we continue to prioritize the repurchase of Berkshire Hathaway shares. In 2020, we repurchased a record $24.7 billion worth of shares, a further indication of ourconfidence in the intrinsic value of our company. We will continue to pursue this strategy in the future, as long as we believe that repurchases represent good value for our shareholders.Looking ahead, we remain optimistic about the future prospects of Berkshire Hathaway. Our strong balance sheet, diversified portfolio, and talented management team position us well to navigate any challenges that may come our way. We will continue to seek out attractive investment opportunities and grow our businesses organically in order to create long-term value for our shareholders.Lastly, I want to express my gratitude to you, our shareholders, for your ongoing support and confidence in Berkshire Hathaway. We are committed to delivering on our promises and working tirelessly to generate superior returns for all of our shareholders.Sincerely,Warren Buffett。

巴菲特致股东的信 1985年各位可能还记得去年年报最后提到的那个爆炸性消息,平时表面上虽然没有什么动作,但我们的经验显示偶尔也会有一些大卡司出现,这种精心设计的企业策略终于在1985年有了结果,在今年报告的后半部将会讨论到(a)我们在资本城/ABC的重大投资部位(b)我们对Scott&Fetzer的购并(c)我们与消防人员保险基金的合约(d)我们卖出在通用食品的部位。

去年波克夏的净值约增加了六亿一千万美金,约相当于增加了48.2%,这比率就好比哈雷慧星造访一般,在我这辈子中再也看不到了,二十一年来我们的净值从19.46增加到1,643.71约为23.2%年复合成长率,这又是一项不可能再重现的比率。

有两个因素让这种比率在未来难以持续,一种因素属于暂时性-即与过去二十年相较,现在股市中缺乏合适的投资机会,如今我们已无法为我们的保险事业投资组合找到价值低估的股票,这种情况与十年前有180度的转变,当时惟一的问题是该挑那一个便宜货。

市场的转变也对我们现有的投资组合产生不利的影响,在1974年的年报中,我可以说我们认为在投资组合中有几支重要个股有大幅成长的潜力,但现在我们说不出口,虽然我们保险公司的主要投资组合中,有许多公司如同过去一样拥有优秀经营团队也极具竞争优势,但目前市场上的股价已充份反应这项特点,这代表今后我们保险公司的投资绩效再也无法像过去那样优异。

第二项负面因素更显而易见的是我们的规模,目前我们在股票投入的资金是十年前的20倍,而市场的铁则是成长终将拖累竞争的优势,看看那些高报酬率的公司,一旦当他们的资本额超过十亿美金,没有一家在往后的十年能够靠再投资维持20%以上的报酬率,而仅能依赖大量配息或买回自家股份来维持,虽然前者能为股东带来更大的利益,但公司就是无法找到理想的投资机会。

而我们的问题就跟他们一样,去年我告诉各位在往后十年我们大约要赚到39亿美金,才能有15%的成长,今年同样的门槛提高到57亿美金(根据统记:扣除石油公司不算,只有15家公司在过去十年能够赚到57亿)我跟Charlie-经营波克夏事业的合伙人,对于波克夏能够保持比一般美国企业更高的获利能力持乐观的态度,而只要获利持续身为股东的你也能保证因此受惠,(1)我们不必去担心每季或每年的帐面获利数字,相反地只要将注意力集中在长远的价值上即可(2)我们可以将事业版图扩大到任何有利可图的产业之上,而完全不受经验、组织或观念所限(3)我们喜爱我们的工作,这些都是关键因素,但即便如此我们仍必须要大赚一笔(比过去达到23.2%还要更多)才有办法使我们的平均报酬率维持15%另外我还必须特别提到一项投资项目,是与最近购买本公司股票的投资人有密切相关的,过去一直以来,波克夏的股票价格约略低于内含价值,维持在这样的水准,投资人可以确定(只要折价的幅度不再继续扩大)其个人的投资经验与该公司本身的表现维持一致,但到了最近,这种折价的状况不再,甚至有时还会发生溢价,折价情况的消失代表着波克夏的市值增加的幅度高于内含价值增长的速度(虽然后者的表现也不错),当然这对于在此现象发生前便持有股份的人算是好消息,但对于新进者或即将加入者却是不利的,而若想要使后者的投资经验与公司的表现一致,则这种溢价现象便必需一直维持,然而管理当局无法控制股价,当然他可对外公布政策与情况,促使市场参与者的行为理性一点,而我个人偏好(可能你也猜得到)即期望公司股价的表现尽量与其企业本身价值接近,惟有维持这种关系,所有公司的股东在其拥有所有权期间皆能与公司共存共荣,股价剧幅的波动并无法使整体的股东受惠,到头来所有股东的获利总和必定与公司的获利一致,但公司的股价长时间偏离内含价值(不管是高估或低估)都将使得企业的获利不平均的分配到各个股东之间,而其结果好坏完全取决于每个股东本身有多幸运、或是聪明愚笨,长久以来,波克夏本身的市场价值与内含价值一直存在着一种稳定的关系,这是在所有我熟悉的上市公司中少见的,这都要归功于所有波克夏的股东,因为大家都很理性、专注、以投资为导向,所以波克夏的股价一直很合理,这不凡的结果是靠一群不凡的股东来完成,几乎我们所有的股东都是个人而非法人机构,没有一家上市公司能够像我们一样。

在2007年的伯克希尔哈撒韦股东大会上,一位来自旧金山的年轻人问巴菲特,要想成为一个好的投资者,最好的方法是什么?巴菲特说:“我10岁的时候就把奥马哈公立图书馆里能找到的投资方面的书都读完了,很多书我都读了两遍,你要把各种思想装进自己的脑子里,随着时间的推移,当你能分辨出哪些是合理的时候,就该下水了。

”投资不是易懂的学问,对一个投资者来说,读一本好的投资书无论何时都是十分重要的。

可投资的书那么多,究竟读哪一本才算赚到呢?首先这本书必须是有价值的,读一本滥竽充数的投资书无疑是在浪费生命。

其次,这本书要足够有趣,读有价值又有趣的投资书籍,才会有快乐的投资和满意的收益。

最后,它要够通俗。

一个无金融背景的普通投资者去研读一部《投资学》,大概要花费掉你半年内所有的业余时间。

如果把非常复杂的投资哲理用简单易懂的话说出来,它可以节省你很多时间。

根据上面3个指标,我们找出了10本经典的投资书籍,它们的研究对象都是西方市场,或者说就是华尔街,可能有人觉得用书中的内容来理解中国股市是不科学的,但美国股市作为一个成熟市场,有着10倍于中国股市的历史,西方市场所经历过的完全有可能在中国市场上重演。

更重要的是,不论中西方,投资理念一定是共通的。

1 《巴菲特传:一个美国资本家的成长》(Buffett:TheMaking of an American Capitalist)罗杰·洛温斯坦作者罗杰·洛温斯坦曾是《华尔街日报(博客,微博)》的资深财经记者,对巴菲特做过多年的跟踪研究。

这本《一个美国资本家的成长》可以作为一本很好了解价值投资理念的书来读,介绍了巴菲特的投资策略和公司价值分析。

巴菲特是一个善于发现价格洼地的人、一个善于在股市高涨的时候主动离开的人,这在很多方面应该归功于其心理上的优势--能够战胜自己的贪婪和恐惧。

巴菲特的财富有很多来自于周期性行业,因为他能够忍受周期性行业的剧烈波动,又有现金在低位不断的补仓,这才使其有了获得超额收益的可能。

Buffett’s Letters To Berkshire Shareholders 1979巴菲特致股东的信 1979年Again, we must lead off with a few words about accounting. Since our last annual report, the accounting profession has decided that equity securities owned by insurance companies must be carried on the balance sheet at market value. We previously have carried such equity securities at the lower of aggregate cost or aggregate market value. Because we have large unrealized gains in our insurance equity holdings, the result of this new policy is to increase substantially both the 1978 and 1979 yearend net worth, even after the appropriate liability is established for taxes on capital gains that would be payable should equities be sold at such market valuations. 首先,还是会计相关的议题,从去年年报开始,会计原则要求保险公司持有的股票投资在资产负债表日的评价方式,从原先的成本与市价孰低法,改按公平市价法列示,由于我们帐上的股票投资拥有大量的未实现利益,因此即便我们已提列了资本利得实现时应该支付的估计所得税负债,我们1978年及1979年的净值依然大幅增加。

巴菲特致合伙人的信1961年(上、下)致我的合伙人:有的合伙人对我说,一年才写一封信,“总要盼很长时间”,能不能半年写一次。

一年写两封信应该也不至于没话说,至少今年是有话说的。

所以,我又写了一封信,以后就每年写两封。

1961 年上半年,包括股息在内,道指的整体收益率是13%。

在这样的行情中,我们应该是最难超过指数的,但在过去六个月里,我管理的所有六个账户的业绩都略高于道指。

1961 年新成立了几个合伙人账户,它们成立的时间有先有后,从成立之初算起,有和指数持平的,也有跑赢的。

这里,我要强调两点。

第一,一年的时间太短,绝对不足以用于评价投资表现,六个月时间更短,更不能用于评价投资表现了。

我之所以不愿意半年写一次信,一个原因就是担心合伙人太看重短期业绩,短期业绩说明不了什么。

我自己更愿意把五年的表现作为评判标准,最好是在五年里经过牛市和熊市相对收益的考验。

第二点,我希望大家都理解,如果股市继续保持1961 年上半年这样的上涨节奏,我怀疑我们不但跑不赢,甚至还会落后指数。

我始终相信,与一般的投资组合相比,我们的持仓更保守,而且大盘越涨,我们越保守。

无论什么时候,我都尽量在投资组合中专门安排一部分资金,投资至少在一定程度上独立于大市的证券。

股市越涨,这部分投资占比越高。

独立于市场有利有弊,市场这口大锅越是热气腾腾,业余的厨子做的饭菜越好吃,这时候业余的厨子尤其厉害,可我们的投资组合呢,更大的仓位都不在锅里。

我们已经开始进行一笔可能规模很大的投资,现在正在公开市场收集筹码,我当然希望这只股票至少在一年里不要上涨。

这样的投资可能拖累短期业绩,但是把时间拉长到几年,不但非常有可能实现超额收益,而且还可以获得极高的防守属性。

我们有望在年底将所有合伙人合并到一个账户。

我已经和新加入的所有合伙人谈过了,也与先前成立的合伙人账户中的代表合伙人讨论了方案。

下面是部分条款:(A) 根据年末市场价值合并所有合伙人账户,明确条款,规定各个合伙人将来如何承担因年底未实现收益需缴纳的税款。

How Inflation Swindles the Equity InvestorThe central problem in the stock market is that the return on capital hasn´t risen with inflation. It seems to be stuck at 12 percent.by Warren E. Buffett, FORTUNE May 1977It is no longer a secret that stocks, like bonds, do poorly in an inflationary environment. We have been in such an environment for most of the past decade, and it has indeed been a time of troubles for stocks. But the reasons for the stock market's problems in this period are still imperfectly understood.There is no mystery at all about the problems of bondholders in an era of inflation. When the value of the dollar deteriorates month after month, a security with income and principal payments denominated in those dollars isn't going to be a big winner. You hardly need a Ph.D. in economics to figure that one out.It was long assumed that stocks were something else. For many years, the conventional wisdom insisted that stocks were a hedge against inflation. The proposition was rooted in the fact that stocks are not claims against dollars, as bonds are, but represent ownership of companies with productive facilities. These, investors believed, would retain their Value in real terms, let the politicians print money as they might.And why didn't it turn but that way? The main reason, I believe, is that stocks, in economic substance, are really very similar to bonds.I know that this belief will seem eccentric to many investors. Thay will immediately observe that the return on a bond (the coupon) is fixed, while the return on an equity investment (the company's earnings) can vary substantially from one year to another. True enough. But anyone who examines the aggregate returns that have been earned by compa-nies during the postwar years will dis-cover something extraordinary: the returns on equity have in fact not varied much at all.The coupon is stickyIn the first ten years after the war - the decade ending in 1955 -the Dow Jones industrials had an average annual return on year-end equity of 12.8 percent. In the second decade, the figure was 10.1 percent. In the third decade it was 10.9 percent. Data for a larger universe, the FORTUNE 500 (whose history goes back only to the mid-1950's), indicate somewhat similar results: 11.2percent in the decade ending in 1965, 11.8 percent in the decade through 1975. The figures for a few exceptional years have been substantially higher (the high for the 500 was 14.1 percent in 1974) or lower (9.5 percent in 1958 and 1970), but over the years, and in the aggregate, the return on book value tends to keep coming back to a level around 12 percent. It shows no signs of exceeding that level significantly in inflationary years (or in years of stable prices, for that matter).For the moment, let's think of those companies, not as listed stocks, but as productive enterprises. Let's also assume that the owners of those enterprises had acquired them at book value. In that case, their own return would have been around 12 percent too. And because the return has been so consistent, it seems reasonable to think of it as an "equity coupon".In the real world, of course, investors in stocks don't just buy and hold. Instead, many try to outwit their fellow investors in order to maximize their own proportions of corporate earnings. This thrashing about, obviously fruitless in aggregate, has no impact on the equity, coupon but reduces the investor's portion of it, because he incurs substantial frictional costs, such as advisory fees and brokerage charges. Throw in an active options market, which adds nothing to, the productivity of American enterprise but requires a cast of thousands to man the casino, and frictional costs rise further.Stocks are perpetualIt is also true that in the real world investors in stocks don't usually get to buy at book value. Sometimes they have been able to buy in below book; usually, however, they've had to pay more than book, and when that happens there is further pressure on that 12 percent. I'll talk more about these relationships later. Meanwhile, let's focus on the main point: as inflation has increased, the return on equity capital has not. Essentially, those who buy equities receive securities with an underlying fixed return - just like those who buy bonds.Of course, there are some important differences between the bond and stock forms. For openers, bonds eventually come due. It may require a long wait, but eventually the bond investor gets to renegotiate the terms of his contract. If current and prospective rates of inflation make his old coupon look inadequate, he can refuse to play further unless coupons currently being offered rekindle his interest. Something of this sort has been going on in recent years.Stocks, on the other hand, are perpetual. They have a maturity date of infinity. Investors in stocks are stuck with whatever return corporate America happens to earn. If corporate America is destined to earn 12 percent, then that is the level investors must learn to live with. As a group, stock investors can neither opt out nor renegotiate. In the aggregate, their commitment is actually increasing. Individual companies can be sold or liquidated and corporations can repurchase theirown shares; on balance, however, new equity flotations and retained earnings guarantee that the equity capital locked up in the corporate system will increase.So, score one for the bond form. Bond coupons eventually will be renegotiated; equity "coupons" won't. It is true, of course, that for a long time a 12 percent coupon did not appear in need of a whole lot of correction.The bondholder gets it in cashThere is another major difference between the garden variety of bond and our new exotic 12 percent "equity bond" that comes to the Wall Street costume ball dressed in a stock certificate.In the usual case, a bond investor receives his entire coupon in cash and is left to reinvest it as best he can. Our stock investor's equity coupon, in contrast, is partially retained by the company and is reinvested at whatever rates the company happens to be earning. In other words, going back to our corporate universe, part of the 12 percent earned annually is paid out in dividends and the balance is put right back into the universe to earn 12 percent also.The good old daysThis characteristic of stocks - the reinvestment of part of the coupon - can be good or bad news, depending on the relative attractiveness of that 12 percent. The news was very good indeed in, the 1950's and early 1960's. With bonds yielding only 3 or 4 percent, the right to reinvest automatically a portion of the equity coupon at 12 percent via s of enormous value. Note that investors could not just invest their own money and get that 12 percent return. Stock prices in this period ranged far above book value, and investors were prevented by the premium prices they had to pay from directly extracting out of the underlying corporate universe whatever rate that universe was earning. You can't pay far above par for a 12 percent bond and earn 12 percent for yourself.But on their retained earnings, investors could earn 22 percent. In effert, earnings retention allowed investots to buy at book value part of an enterprise that, :in the economic environment than existing, was worth a great deal more than book value.It was a situation that left very little to be said for cash dividends and a lot to be said for earnings retention. Indeed, the more money that investors thought likely to be reinvested at the 12 percent rate, the more valuable they considered their reinvestment privilege, and the more they were willing to pay for it. In the early 1960's, investors eagerly paid top-scale prices for electric utilities situated in growth areas, knowing that these companies had the ability to reinvest verylarge proportions of their earnings. Utilities whose operating environment dictated a larger cash payout rated lower prices.If, during this period, a high-grade, noncallable, long-term bond with a 12 percent coupon had existed, it would have sold far above par. And if it were a bond with a f urther unusual characteristic - which was that most of the coupon payments could be automatically reinvested at par in similar bonds - the issue would have commanded an even greater premium. In essence, growth stocks retaining most of their earnings represented just such a security. When their reinvestment rate on the added equity capital was 12 percent while interest rates generally were around 4 percent, investors became very happy - and, of course, they paid happy prices.Heading for the exitsLooking back, stock investors can think of themselves in the 1946-56 period as having been ladled a truly bountiful triple dip. First, they were the beneficiaries of an underlying corporate return on equity that was far above prevailing interest rates. Second, a significant portion of that return was reinvested for them at rates that were otherwise unattainable. And third, they were afforded an escalating appraisal of underlying equity capital as the first two benefits became widely recognized. This third dip meant that, on top of the basic 12 percent or so earned by corporations on their equity capital, investors were receiving a bonus as the Dow Jones industrials increased in price from 138 percent book value in 1946 to 220 percent in 1966, Such a marking-up process temporarily allowed investors to achieve a return that exceeded the inherent earning power of the enterprises in which they had invested.This heaven-on-earth situation finally was "discovered" in the mid-1960's by many major investing institutions. But just as these financial elephants began trampling on one another in their rush to equities, we entered an era of accelerating inflation and higher interest rates. Quite logically, the marking-up process began to reverse itself. Rising interest rates ruthlessly reduced the value of all existing fixed-coupon investments. And as long-term corporate bond rates began moving up (eventually reaching the 10 percent area), both the equity return of 12 percept and the reinvestment "privilege" began to look different.Stocks are quite properly thought of as riskier than bonds. While that equity coupon is more or less fixed over periods of time, it does fluctuate somewhat from year to year. Investors' attitudes about the future can be affected substantially, although frequently erroneously, by those yearly changes. Stocks are also riskier because they come equipped with infinite maturities. (Even your friendly broker wouldn't have the nerve to peddle a 100-year bond, if he had any available, as "safe.") Because of the additional risk, the natural reaction of investors is to expectan equity return that is comfortably above the bond return - and 12 percent on equity versus, say, 10 percent on bonds issued py the same corporate universe does not seem to qualify as comfortable. As the spread narrows, equity investors start looking for the exits.But, of course, as a group they can't get out. All they can achieve is a lot of movement, substantial frictional costs, and a new, much lower level of valuation, reflecting the lessened attractiveness of the 12 percent equity coupon under inflationary conditions. Bond investors have had a succession of shocks over the past decade in the course of discovering that there is no magic attached to any given coupon level - at 6 percent, or 8 percept, or 10 percent, bonds can still collapse in price. Stock investors, who are in general not aware that they too have a "coupon", are still receiving their education on this point.Five ways to improve earningsMust we really view that 12 percent equity coupon as immutable? Is there any law that says the corporate return on equity capital cannot adjust itself upward in response to a permanently higher average rate of inflation?There is no such law, of course. On the other hand, corporate America cannot increase earnings by desire or decree. To raise that return on equity, corporations would need at least one of the following: (1) an increase in turnover, i.e., in the ratio between sales and total assets employed in the business; (2) cheaper leverage; (3) more leverage; (4) lower income taxes, (5) wider operating margins on sales.And that's it. There simply are no other ways to increase returns on common equity. Let's see what can be done with these.We'll begin with turnover. The three major categories of assets we have to think about for this exercise are accounts receivable inventories, and fixed assets such as plants and machinery.Accounts receivable go up proportionally as sales go up, whether the increase in dollar sales is produced by more physical volume or by inflation. No room for improvement here.With inventories, the situation is not quite as simple. Over the long term, the trend in unit inventories may be expected to follow the trend in unit sales. Over the short term, however, the physical turnover rate may bob around because of spacial influences - e.g., cost expectations, or bottlenecks.The use of last-in, first-out (LIFO) inventory-valuation methods serves to increase the reported turnover rate during inflationary times. When dollar sales are rising because of inflation, inventory valuations of a LIFO company either will remain level, (if unit sales are not rising) orwill trail the rise 1n dollar sales (if unit sales are rising). In either case, dollar turnover will increase.During the early 1970's, there was a pronounced swing by corporations toward LIFO accounting (which has the effect of lowering a company's reported earnings and tax bills). The trend now seems to have slowed. Still, the existence of a lot of LIFO companies, plus the likelihood that some others will join the crowd, ensures some further increase it the reported turnover of inventory.The gains are apt to be modestIn the case of fixed assets, any rise in the inflation rate, assuming it affects all products equally, will initially have the effect of increasing turnover. That is true because sales will immediately reflect the new price level, while the fixed-asset account will reflect the change only gradually, i.e., as existing assets are retired and replaced at the new prices. Obviously, the more slowly a company goes about this replacement process, the more the turnover ratio will rise. The action stops, however, when a replacement cycle is completed. Assuming a constant rate of inflation, sales and fixed assets will then begin to rise in concert at the rate of inflation.To sum up, inflation will produce some gains in turnover ratios. Some improvement would be certain because of LIFO, and some would be possible (if inflation accelerates) because of sales rising more rapidly than fixed assets. But the gains are apt to be modest and not of a magnitude to produce substantial improvement in returns on equity capital. During the decade ending in 1975, despite generally accelerating inflation and the extensive use of LIFO accounting, the turnover ratio of the FORTUNE 500 went only from 1.18/1 to 1.29/1.Cheaper leverage? Not likely. High rates of inflation generally cause borrowing to become dearer, not cheaper. Galloping rates of inflation create galloping capital needs; and lenders, as they become increasingly distrustful of long-term contracts, become more demanding. But even if there is no further rise in interest rates, leverage will be getting more expensive because the average cost of the debt now on corporate books is less than would be the cost of replacing it. And replacement will be required as the existing debt matures. Overall, then, future changes in the cost of leverage seem likely to have a mildly depressing effect on the return on equity.More leverage? American business already has fired many, if not most, of the more-leverage bullets once available to it. Proof of that proposition can be seen in some other FORTUNE 500 statistics - in the twenty years ending in 1975, stockholders' equity as a percentage of total assets declined for the 500 from 63 percent to just under 50 percent. In other words, each dollar of equity capital now is leveraged much more heavily than it used to be.What the lenders learnedAn irony of inflation-induced financial requirements is that the highly profitable companies - generally the best credits - require relatively little debt capital. But the laggards in profitability never can get enough. Lenders understand this problem much better than they did a decade ago - and are correspondingly less willing to let capital-hungry, low-profitability enterprises leverage themselves to the sky.Nevertheless, given inflationary conditions, many corporations seem sure in the future to turn to still more leverage as a means of shoring up equity returns. Their managements will make that move because they will need enormous amounts of capital - often merely to do the same physical volume of business - and will wish to got it without cutting dividends or making equity offerings that, because of inflation, are not apt to shape up as attractive. Their natural response will be to heap on debt, almost regardless of cost. They will tend to behave like those utility companies that argued over an eighth of a point in the 1960's and were grateful to find 12 percent debt financing in 1974.Added debt at present interest rates, however, will do less for equity returns than did added debt at 4 percent rates it the early 1960's. There is also the problem that higher debt ratios cause credit ratings to be lowered, creating a further rise in interest costs.So that is another way, to be added to those already discussed, in which the cost of leverage will be rising. In total, the higher costs of leverage are likely to offset the benefits of greater leverage.Besides, there is already far more debt in corporate America than is conveyed by conventional balance sheets. Many companies have massive pension obligations geared to whatever pay levels will be in effect when present workers retire. At the low inflation rates of 1965-65, the liabilities arising from such plans were reasonably predictable. Today, nobody can really know the company's ultimate obligation, But if the inflation rate averages 7 percent in the future, a twentyfive-year-old employee who is now earning $12,000, and whose raises do no more than match increases in living costs, will be making $180,000 when he retires at sixty-five.Of course, there is a marvelously precise figure in many annual reports each year, purporting to be the unfunded pension liability. If that figure were really believable, a corporation could simply ante up that sum, add to it the existing pension-fund assets, turn the total amount over to an insurance company, and have it assume all the corporation's present pension liabilities. In the real world, alas, it is impossible to find an insurance company willing even to listen to such a deal.Virtually every corporate treasurer in America would recoil at the idea of issuing a "cost-of-living" bond - a noncallable obligation with coupons tied to a price index. But through the privatepension system, corporate America has in fact taken on a fantastic amount of debt that is the equivalent of such a bond.More leverage, whether through conventional debt or unbooked and indexed "pension debt", should be viewed with skepticism by shareholders. A 12 percent return from an enterprise that is debt-free is far superior to the same return achieved by a business hocked to its eyeballs. Which means that today's 12 percent equity returns may well be less valuable than the 12 percent returns of twenty years ago.More fun in New YorkLower corporate income taxes seem unlikely. Investors in American corporations already own what might be thought of as a Class D stock. The class A, B and C stocks are represented by the income-tax claims of the federal, state, and municipal governments. It is true that these "investors" have no claim on the corporation's assets; however, they get a major share of the earnings, including earnings generated by the equity buildup resulting from retention of part of the earnings owned by the Class D sharaholders.A further charming characteristic of these wonderful Class A,B andC stocks is that their share of the corporation's earnings can be increased immedtately, abundantly, and without payment by the unilateral vote of any one of the "stockholder" classes, e.g., by congressional action in the case of the Class A. To add to the fun, one of the classes will sometimes vote to increase its ownership share in the business retroactively - as companies operating in New York discovered to their dismay in 1975. Whenever the Class A, B or C "stockholders" vote themselves a larger share of the business, the portion remaining for ClassD - that's the one held by the ordinary investor - declines.Looking ahead, it seems unwise to assume that those who control the A, B and C shares will vote to reduce their own take over the long run. The class D shares probably will have to struggle to hold their own.Bad news from the FTCThe last of our five possible sources of increased returns on equity is wider operating margins on sales. Here is where some optimists would hope to achieve major gains. There is no proof that they are wrong. Bu there are only 100 cents in the sales dollar and a lot of demands on that dollar before we get down to the residual, pretax profits. The major claimants are labor, raw materials energy, and various non-income taxes. The relative importance of these costs hardly, seems likely to decline during an age of inflation.Recent statistical evidence, furthermore, does not inspire confidence in the proposition that margins will widen in, a period of inflation. In the decade ending in 1965, a period of relatively low inflation, the universe of manufacturing companies reported on quarterly by the Federal Trade Commission had an average annual pretax margin on sales of 8.6 percent. In the decade ending in 1975, the average margin was 8 percent. Margins were down, in other words, despite a very considerable increase in the inflation rate.If business was able to base its prices on replacement costs, margins would widen in inflationary periods. But the simple fact is that most large businesses, despite a widespread belief in their market power, just don't manage to pull it off. Replacement cost accounting almost always shows that corporate earnings have declined significantly in the past decade. If such major industries as oil, steel, and aluminum really have the oligopolistic muscle imputed to them, one can only conclude that their pricing policies have been remarkably restrained.There you have, the complete lineup: five factors that can improve returns on common equity, none of which, by my analysis, are likely to take us very far in that direction in periods of high inflation. You may have emerged from this exercise more optimistic than I am. But remember, returns in the 12 percent area have been with us a long time.The investor's equationEven if you agree that the 12 percent equity coupon is more or less immutable, you still may hope to do well with it in the years ahead. It's conceivable that you will. After all, a lot of investors did well with it for a long time. But your future results will be governed by three variable's: the relationship between book value and market value, the tax rate, and the inflation rate.Let's wade through a little arithmetic about book and market value. When stocks consistently sell at book value, it's all very simple. If a stock has a book value of $100 and also an average market value of $100, 12 percent earnings by business will produce a 12 percent return for the investor (less those frictional costs, which we'll ignore for the moment). If the payout ratio is 50 percent, our investor will get $6 via dividends and a further $6 from the increase in the book value of the business, which will, of course, be reflected in the market value of his holdings.If the stock sold at 150 percent of book value, the picture would change. The investor would receive the same $6 cash dividend, but it would now represent only a 4 percent return on his $150 cost. The book value of the business would still increase by 6 percent (to $106) and the market value of the investor's holdings, valued consistently at 150 percent of book value, would similarlyincrease by 6 percent (to $159). But the investor's total return, i.e., from appreciation plus dividends, would be only 10 percent versus the underlying 12 percent earned by the business.When the investor buys in below book value, the process is reversed. For example, if the stock sells at 80 percent of book value, the same earnings and payout assumptions would yield 7.5 percent from dividends ($6 on an $80 price) and 6 percent from appreciation - a total return of 13.5 percent. In other words, you do better by buying at a discount rather than a premium, just as common sense would suggest.During the postwar years, the market value of the Dow Jones industrials has been as low as 84 percent of book value (in 1974) and as high as 232 percent (in 1965); most of the time the ratio has been well over 100 percent. (Early this spring, it was around 110 percent.) Let's assume that in the future the ratio will be something close to 100 percent - meaning that investors in stocks could earn the full 12 percent. At least, they could earn that figure before taxes and before inflation.7 percent after taxesHow large a bite might taxes take out of the 12 percent? For individual investors, it seems reasonable to assume that federal, state, and local income taxes will average perhaps 50 percent on dividends and 30 percent on capital gains. A majority of investors may have marginal rates somewhat below these, but many with larger holdings will experience substantially higher rates. Under the new tax law, as FORTUNE observed last month, a high-income investor in a heavily taxed city could have a marginal rate on capital gains as high as 56 percent. (See "The Tax Practitioners Act of 1976.")So let's use 50 percent and 30 percent as representative for individual investors. Let's also assume, in line with recent experience, that corporations earning 12 percent on equity pay out 5 percent in cash dividends (2.5 percent after tax) and retain 7 percent, with those retained earnings producing a corresponding market-value growth (4.9 percent after the 30 percent tax). The after-tax return, then, would be 7.4 percent. Probably this should be rounded down to about 7 percent to allow for frictional costs. To push our stocks-asdisguised-bonds thesis one notch further, then, stocks might be regarded as the equivalent, for individuals, of 7 percent tax-exempt perpetual bonds.The number nobody knowsWhich brings us to the crucial question - the inflation rate. No one knows the answer on this one - including the politicians, economists, and Establishment pundits, who felt, a few years back,that with slight nudges here and there unemployment and inflation rates would respond like trained seals.But many signs seem negative for stable prices: the fact that inflation is now worldwide; the propensity of major groups in our society to utilize their electoral muscle to shift, rather than solve, economic problems ; the demonstrated unwillingness to tackle even the most vital problems (e.g., energy and nuclear proliferation) if they can be postponed; and a political system that rewards legislators with reelection if their actions appear to produce short-term benefits even though their ultimate imprint will be to compound long-term pain.Most of those in political office, quite understandably, are firmly against inflation and firmly in favor of policies producing it. (This schizophrenia hasn't caused them to lose touch with reality, however; Congressmen have made sure that their pensions - unlike practically all granted in the private sector - are indexed to cost-of-living changes after retirement.)Discussions regarding future inflation rates usually probe the subtleties of monetary and fiscal policies. These are important variables in determining the outcome of any specific inflationary equation. But, at the source, peacetime inflation is a political problem, not an economic problem. Human behavior, not monetary behavior, is the key. And when very human politicians choose between the next election and the next generation, it's clear what usually happens.Such broad generalizations do not produce precise numbers. However, it seems quite possible to me that inflation rates will average 7 percent in future years. I hope this forecast proves to be wrong. And it may well be. Forecasts usually tell us more of the forecaster than of the future. You are free to factor your own inflation rate into the investor's equation. But if you foresee a rate averaging 2 percent or 3 percent, you are wearing different glasses than I am.So there we are: 12 percent before taxes and inflation; 7 percent after taxes and before inflation; and maybe zero percent after taxes and inflation. It hardly sounds like a formula that will keep all those cattle stampeding on TV.As a common stockholder you will have more dollars, but you may have no more purchasing power. Out with Ben Franklin ("a penny saved is a penny earned") and in with Milton Friedman ("a man might as well consume his capital as invest it").What widows don't noticeThe arithmetic makes it plain that inflation is a far more devastating tax than anything that has been enacted by our legislatures. The inflation tax has a fantastic ability to simply consume capital. It makes no difference to a widow with her savings in a 5 percent passbook account。

历年巴菲特致股东的信英文原版Warren Buffett's Annual Letters to ShareholdersIntroduction:Every year, legendary investor Warren Buffett writes a letter to the shareholders of his company, Berkshire Hathaway. These letters are eagerly anticipated by investors, analysts, and the general public, as they provide valuable insights into Buffett's investment philosophy, views on the economy, and updates on the company's performance. Over the years, Buffett's letters have become a treasure trove of wisdom for investors looking to learn from one of the most successful investors of all time.Year 1: 1977In his first letter to shareholders in 1977, Buffett outlined his investment principles and the philosophy that would guide his investment decisions for decades to come. He emphasized the importance of investing in companies with strong competitive advantages, a competent and trustworthy management team, and a long-term mindset. Buffett also stressed the importance of focusing on the intrinsic value of a company rather than its stock price, and the importance of having a margin of safety when making investment decisions.Year 2: 1985In 1985, Buffett's letter focused on the importance of staying true to your investment principles, even in the face of market volatility or criticism. He emphasized the importance of patience, discipline, and a long-term perspective in investing, and stressed that short-term fluctuations in the market should not deter investors from sticking to their investment strategy. Buffett also discussed the importance of having a diverse portfolio of investments to reduce risk and increase the chances oflong-term success.Year 3: 1999In 1999, Buffett warned investors about the dangers of speculation and excessive risk-taking in the stock market. He cautioned against investing in overvalued companies or in industries with uncertain futures, and advised investors to focus on companies with sustainable competitive advantages and strong financials. Buffett also discussed the importance of maintaining a margin of safety in all investment decisions, and stressed the importance of doing thorough research before making any investment.Year 4: 2008In 2008, Buffett's letter addressed the global financial crisis and its implications for investors. He discussed the importance of staying calm and rational during times of market turmoil, and emphasized the importance of focusing on the long-term prospects of companies rather than short-term market movements. Buffett also discussed the importance of having a strong balance sheet and ample liquidity in times of economic uncertainty, and stressed the importance of being prepared for any eventuality in the market.Year 5: 2016In 2016, Buffett's letter focused on the changing landscape of the investment industry and the impact of technology on the economy. He discussed the importance of staying flexible and adaptable in an ever-changing world, and emphasized the importance of continuously learning and evolving as an investor. Buffett also discussed the importance of having a sound investment process and sticking to your principles even in the face of uncertainty, and stressed the importance of maintaining a long-term perspective in investing.ConclusionWarren Buffett's annual letters to shareholders are a valuable resource for investors looking to learn from one of themost successful investors of all time. His insights, wisdom, and investment philosophy have stood the test of time and continue to be relevant in today's ever-changing investment landscape. Buffett's letters serve as a guidepost for investors looking to navigate the complexities of the stock market and achievelong-term success in their investment journey.。

巴菲特2023给股东的信英文版全文共10篇示例,供读者参考篇1Dear Shareholders,Hiya! It's your pal Warren Buffett here again with my annual letter to you all. I hope you've been having a great year and that your investments have been doing well. I know the stock market can be a bit tricky, but don't worry, I'm here to help guide you through it!First off, I want to say a big THANK YOU to all of you for believing in Berkshire Hathaway and for being part of our family. We wouldn't be where we are today without you. You guys are the best!Now, let's talk a bit about how we did in 2023. It's been a bit of a bumpy ride with all the ups and downs in the market, but our team has been working hard to make sure we're making smart investments for the long term. We've had some wins and some losses, but overall, I'm pleased with how we've been doing.I know that some of you might be worried about the future of the stock market, but remember, I've been in this game for a long time and I've seen it all. The key is to stay calm, do your research, and invest in companies that you believe in for the long haul. That's the Buffett way!As always, if you have any questions or need some advice, feel free to reach out to me or my team. We're here to help you succeed in your investing journey. Remember, it's not about timing the market, it's about time in the market.Alrighty, I'll wrap things up now. Thanks again for being awesome shareholders and for being part of the Berkshire Hathaway family. Here's to a prosperous 2024!Your friend,Warren Buffett篇2Dear Shareholders,Hi everyone, it's me, Warren Buffett! I hope you're all doing well and staying healthy. I just wanted to take a moment to write you all a little letter and update you on everything that's been going on with our company Berkshire Hathaway.First of all, I want to say a big thank you to all of our shareholders for your continued support and belief in our company. We wouldn't be where we are today without all of you, so thank you from the bottom of my heart.I'm happy to report that despite the challenges of the past year, Berkshire Hathaway has continued to grow and thrive. Our investments have been performing well, and our businesses have been strong. I'm proud of the hard work and dedication of our employees, and I know that we have a bright future ahead of us.As always, I want to remind all of our shareholders to focus on the long term. Investing in stocks is a marathon, not a sprint. It's important to be patient and stay focused on our goals. Remember, Rome wasn't built in a day!I also want to encourage all of you to continue to educate yourselves about investing. Knowledge is power, and the more you know, the better equipped you will be to make smart investment decisions.In conclusion, I want to thank you all once again for your support. I am confident that together, we will continue to achieve great things. And remember, as always, the best investment you can make is in yourself. So keep learning, keep growing, and keep believing in the future.Yours truly,Warren Buffett篇3Dear shareholders,Hi everyone! I'm Warren Buffett, your favorite old investor, here to share some exciting news with you all. I hope you're all doing well and staying safe.I can't believe it's already 2023! Time flies when you're having fun, right? And I have to say, it's been another incredible year for Berkshire Hathaway. We've been making some big moves and I couldn't wait to tell you all about it.First of all, our investments have been doing really well. I've been keeping an eye on the stock market and making some smart choices, which has helped our company grow even more. I always say that it's important to invest in companies that you believe in, and that's exactly what we've been doing.But it's not just about the money for me. I always remember that it's about the people too. That's why we've been working hard to give back to our communities and help those in need.Whether it's through our donations or our volunteer work, we're always looking for ways to make a positive impact.I know that things can be tough sometimes, especially with everything going on in the world right now. But I want you all to remember that we're in this together. We're a team, and as long as we stick together and keep working hard, we can overcome any challenge that comes our way.So keep your heads high, keep believing in yourself, and keep being the awesome shareholders that you are. I know that together, we can achieve anything.Thanks for your support, and I'll talk to you all again soon.Your friend,Warren Buffett篇4Dear Shareholders,Hey guys, it's me, Warren Buffett! I hope you're all doing well and enjoying the rollercoaster ride of the stock market. 2023 has been quite a year so far, hasn't it?I wanted to take this opportunity to update you on how our company is doing. Despite the challenges we've faced, I am pleased to report that our business is still going strong. Our investments continue to perform well, and we are optimistic about the future.I know that times have been tough for many people, especially with the ongoing pandemic. But rest assured that we are doing everything we can to weather the storm and come out stronger on the other side. As always, our focus remains on creating long-term value for our shareholders.In the coming months, we will continue to pursue new opportunities and make strategic investments that will drive growth and profitability. I am confident that with your continued support, we will be able to overcome any obstacles that come our way.In closing, I want to thank you for your unwavering loyalty and trust in our company. Your support means the world to us, and we are committed to delivering on our promise to create value for you, our shareholders.Until next time, take care and stay safe!Warm regards,Warren Buffett篇5Dear Shareholders,Hello everybody! I'm Warren Buffett, the CEO of Berkshire Hathaway. I hope you are all doing great and staying healthy. I wanted to take some time to share some exciting news and updates with you all.First off, I am happy to report that Berkshire Hathaway had another successful year in 2023. Our investments have continued to grow and our portfolio is looking stronger than ever. I want to thank all of you for your continued support and trust in our company.As you may know, I am a big believer in long-term investing and staying patient in the market. It's important to remember that the stock market can be unpredictable, but if you stay focused on the fundamentals and invest in good companies, you will see success over time.I also want to remind you all to always do your own research and make informed decisions when it comes to your investments.It's important to understand the companies you are investing in and to have a clear strategy in place.In closing, I want to thank you all again for being loyal shareholders of Berkshire Hathaway. I truly appreciate your support and trust in our company. I look forward to another successful year ahead and I am confident that we will continue to grow and thrive together.Keep investing smart and stay positive!Sincerely,Warren Buffett篇6Dear Shareholders,Hi there! It's me, Warren Buffett, your friendly neighborhood investing guru. I hope this letter finds you well and feeling excited about the future of our company. Let's dive right into it!I am pleased to report that in 2023, our company has continued to outperform the market and deliver strong returns for our shareholders. Despite facing challenges from the global economy, we have remained resilient and focused on ourlong-term goals.One of the things that sets us apart from other companies is our commitment to ethical business practices and transparency. We believe in doing the right thing, even when it's hard, and that's why our shareholders trust us to make the best decisions for their investments.As we look ahead to the coming year, I am confident that our company will continue to thrive and grow. Our team is dedicated to finding new opportunities and delivering value for our shareholders. We will continue to invest in our people, our products, and our communities to ensure a bright future for all.In closing, I want to thank each and every one of you for your continued support and trust in our company. Together, we can achieve great things and build a better future for all. Here's to another successful year ahead!Sincerely,Warren BuffettP.S. Remember, invest for the long-term and stay positive!篇7Dear Shareholders,Hi everyone! I hope you are all doing well and enjoying your day. I want to take this chance to talk to you all about how things are going at Berkshire Hathaway.I am happy to say that in 2023, we had a really great year! Our business did really well and we made a lot of money. This wouldn't have been possible without all of you, so thank you for your support and investment in Berkshire Hathaway.I know that sometimes the stock market can be a little bit crazy and it's hard to know what to do. But I want to remind you all that it's important to stay calm and not make any rash decisions. Investing for the long term is the best way to grow your money and I believe in our company's future.As always, I want to encourage you all to keep learning and educating yourselves about investing. The more you know, the better decisions you can make. And don't forget to do your own research before investing in any company.I am proud of what we have accomplished together and I am excited for what the future holds for Berkshire Hathaway. Thank you for being a part of our family and I look forward to many more successful years ahead.Sincerely,Warren Buffett篇8Dear Shareholders,Hi guys! It’s your buddy Warren Buffett here again! I hope you are all doing great and enjoying your journey as part owners of Berkshire Hathaway. I wanted to take a moment to chat with you about all the exciting things happening in our company.First things first, I want to thank each and every one of you for your continued support and trust in me and the Berkshire team. Your confidence in us means the world and we are always striving to make you proud.Now, let’s talk about our performance in 2023. I am happy to report that we have had another successful year. Our investments are doing well and our businesses are thriving. We continue to focus on long-term value creation and maintaining a strong financial position.One of the keys to our success is our amazing team. I am so grateful for the hard work and dedication of all our employees and managers. They are the heart and soul of Berkshire Hathaway and I am proud to work with such talented individuals.I also want to remind you all to stay focused on the long term when it comes to investing. As I always say, “Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.” Stay disciplined, do your research, and invest in companies with solid fundamentals.In closing, I want to thank you all again for your support and for being part of the Berkshire Hathaway family. I am excited about the future and confident that together we will continue to achieve great things.Keep smiling and keep investing!Your pal,Warren Buffett篇9Dear Shareholders,Hello everyone! I hope you are all doing well and enjoying your day. It's me, Warren Buffett, your favorite billionaire investor, here to share some exciting news with you all.First of all, I want to thank each and every one of you for your continued support and trust in our company, Berkshire Hathaway. Your confidence in our team and our investmentsmeans the world to me, and I am so grateful for all of your support.Now, let's talk about the future. As we look ahead to 2023, I am feeling optimistic about the opportunities that lie ahead for Berkshire Hathaway. Despite the challenges we have faced in the past, I believe that we are well-positioned to continue growing and succeeding in the years to come.One of the key reasons for my optimism is our talented team of managers and employees. I am proud to say that we have some of the best minds in the business working for us, and I have no doubt that they will continue to deliver exceptional results for our shareholders.In addition, our portfolio of investments is stronger than ever, and I am confident that we will continue to find new opportunities to grow and expand our business in the coming years.As always, I encourage you to keep a long-term perspective when it comes to investing. Remember that the stock market can be unpredictable, but if you stay patient and focused on the fundamentals, you will have a much better chance of success in the long run.Thank you again for your continued support and trust in Berkshire Hathaway. I look forward to sharing more updates with you in the future.Sincerely,Warren Buffett篇10Dear Shareholders,Hi everyone, it’s me, Warren Buffett! I hope you’re all doing well and staying safe during these uncertain times. I wanted to take a moment to write to all of you and share some thoughts about the year that’s passed and what’s ahead for us.First of all, I want to thank each and every one of you for your continued support and trust in me and Berkshire Hathaway. It means the world to me and I am truly grateful for your loyalty.Now, let’s talk a bit about the year 2023. It’s been a rollercoaster of a year, hasn’t it? The stock market has been up and down, and there have been many challenges along the way. But through it all, we’ve stuck together as a team and come out stronger on the other side.I want to reassure you all that despite the ups and downs, I am confident in the future of our company. We have a solid foundation, a talented team, and a clear vision for the road ahead. We will weather this storm and come out even stronger than before.As always, I encourage you to stay focused on the long term and not get caught up in the day-to-day fluctuations of the market. Remember, investing is a marathon, not a sprint. Stay patient, stay disciplined, and trust in the process.In closing, I want to thank you once again for your support and dedication. Together, we will continue to build a bright future for Berkshire Hathaway and all of our shareholders.Wishing you all the best and looking forward to what the future holds.Sincerely,Warren Buffett。

Buffett’s Letters To Berkshire Shareholders 1980巴菲特致股东的信 1980年Operating earnings improved to $41.9 million in 1980 from $36.0 million in 1979, but return on beginning equity capital (with securities valued at cost) fell to 17.8% from 18.6%. We believe the latter yardstick to be the most appropriate measure of single-year managerial economic performance. Informed use of that yardstick, however, requires an understanding of many factors, including accounting policies, historical carrying values of assets, financial leverage, and industry conditions. 1980年本公司的营业利益为4,190万美元,较1979年的3,600万美元成长,但期初股东权益报酬率(持有股票投资以原始成本计)却从去年的18.6%滑落至17.8%。

我们认为这个比率最能够作为衡量公司管理当局单一年度经营绩效的指针。

当然要运用这项指针,还必须对包含会计原则、资产取得历史成本、财务杠杆与产业状况等在内的主要因素有一定程度的了解才行。

In your evaluation of our economic performance, we suggest that two factors should receive your special attention - one of a positive nature peculiar, to a large extent, to our own operation, and one of a negative nature applicable to corporate performance generally. Let’s look at the bright side first. 各位在判断本公司的经营绩效时,有两个因素是你必须特别注意的,一项是对公司营运相当有利的,而另一项则企业绩效相对较不利的。

1958 Letter Warren E Buffett5202 Underwood Ave. Omaha, NebraskaTHE GENERAL STOCK MARKET IN 19581958 年股票市场的总体情况A friend who runs a medium-sized investment trust recently wrote: "The mercurial temperament, characteristic of the American people, produced a major transformation in 1958 and ‘exuberant’ would be the proper word for the stock market, at least".一个运作中等规模投资信托的朋友最近写到:“浮躁易变的情绪,美国人的主要特征,造就了1958 年股票市场”。

至少,用“亢奋”这一词形容1958 年的股票市场是合适的。

I think this summarizes the change in psychology dominating the stock market in 1958 at both the amateur and professional levels. During the past year almost any reason has been seized upon to justify “Investing” in the market. There are undou btedly more mercurially-tempered people in the stock market now than for a good many years and the duration of their stay will be limited to how long they think profits can be made quickly and effortlessly. While it is impossible to determine how long theywill continue to add numbers to their ranks and thereby stimulate rising prices, I believe it is valid tosay that the longer their visit, the greater the reaction from it.我觉得这句话—无论从业余角度还是专业角度——很好地概括了主导1958 年股票市场的心理变化。

Buffett’s Letters To Berkshire Shareholders 1989巴菲特致股东的信 1989年Our gain in net worth during 1989 was $1.515 billion, or 44.4%. Over the last 25 years (that is, since present management took over) our per-share book value has grown from $19.46 to $4,296.01, or at a rate of 23.8% compounded annually. 本公司1989年的净值增加了15亿1千5百万美元,较去年增加了44.4%,过去25年以来(也就是自从现有经营阶层接手后),每股净值从19元成长到现在的4,296美元,年复合成长率约为23.8%。

What counts, however, is intrinsic value -the figure indicating what all of our constituent businesses are rationally worth. With perfect foresight, this number can be calculated by taking all future cash flows of a business -in and out - and discounting them at prevailing interest rates. So valued, all businesses, from manufacturers of buggy whips to operators of cellular phones, become economic equals. 然而真正重要的还是实质价值-这个数字代表组合我们企业所有份子合理的价值,根据精准的远见,这个数字可由企业未来预计的现金流量(包含流进与流出),并以现行的利率予以折现,不管是马鞭的制造公司或是行动电话的业者都可以在同等的地位上,据以评估其经济价值。

第1章公司治理对于股东和管理人员而言,许多股东年会是在浪费时间。

有时这是因为管理人员不愿披露企业的实质问题,但在更多情况下,一场毫无结果的股东年会是由于到场的股东们更关心自己的表现机会,而不是股份公司的事务。

一场本应进行业务讨论的股东大会却变成了表演戏剧、发泄怨气和鼓吹己见的论坛。

(这种情况是不可避免的:为了每股股票的价格,你不得不告诉痴迷的听众你关于这个世界应当如何运转的意见。

)在这种情况下,股东年会的质量总是一年不如一年,因为那些只关心自己的股东的哗众取宠的行为挫伤了那些关心企业的股东们。

伯克希尔的股东年会则完全是另外一种情况。

与会的股东人数每年都略有增加,而且我们从未面对过愚蠢的问题,或是自私自利的评论。

相反,我们得到的却是各式各样与公司有关的,有创见的问题。

因为股东年会就是解答这些问题的时间和地点,所以查理和我都很乐意回答所有的问题,无论要花多少时间。

(但我们不能在每年的其他时间回答以书信或电话方式提出的问题;对于一个拥有数千名股东的公司来说,一次只向一个人汇报是在浪费管理时间。

)在股东年会上真正禁止谈论的公司业务,是那些因坦诚而可能使公司真正破费的事情。

我们的证券投资活动就是个主要的例子。

与所有者相关的企业原则1.尽管我们的形式是法人组织,但我们的经营观念却是合伙制。

查理?芒格和我将我们的股东看做是所有者合伙人(Owner-partner),并将我们自己看作经营合伙人(ManagingPartner)。

(由于我们的持股规模,不管怎样我们还是有控制权的合伙人。

)我们并不将公司本身作为我们企业资产的最终所有者,而是将企业看成是一个通道,我们的股东通过它拥有资产。

查理和我希望你们不要认为自己仅仅拥有一纸价格每天都在变动的凭证,而且一旦发生某种经济或政治事件就会使你紧张不安,它就是出售的候选对象。

相反,我们希望你们把自己想像成一家企业的所有者之一,对这家企业你愿意无限期地投资,就像你与家庭成员合伙拥有一个农场或一套公寓那样。

波克夏海瑟崴股份有限公司致股东函董事长的信1983Berkshire海瑟崴股份有限公司致Berkshire公司全体股东:去年登记为Berkshire的股东人数由1,900人增加到2,900人,主要是由于我们与Blue Chip 的合併案,但也有一部份是因为自然增加的速度,就像几年前我们一举成长突破1,000大关一样。

有了这么多新股东,有必要将有关经营者与所有者间关系方面的主要企业原则加以汇整说明:尽管我们的组织登记为公司,但我们是以合伙的心态来经营(Although our form is corporate, our attitude is partnership.) 查理孟格跟我视Berkshire的股东为合伙人,而我们两个人则为执行合伙人(而也由于我们持有股份比例的关系,也算是具控制权的合伙人)我们并不把公司视为企业资产的最终拥有人,实际上公司只要股东拥有资产的一个媒介而已。

对应前述所有权人导向,我们所有的董事都是Berkshire的大股东,五个董事中的四个,其家族财产有超过一半是Berkshire持股,简言之,我们自给自足。

我们长远的经济目标(附带后面所述的几个标准)是将每年平均每股实质价值的成长率极大化,我们不以Berkshire规模来作为衡量公司的重要性或表现,由于资本大幅提高,我们确定每股价值的年增率一定会下滑,但至少不能低于一般美国大企业平均数。

我们最希望能透过直接拥有会产生现金且具有稳定的高资本报酬率的各类公司来达到上述目的,否则退而求其次,是由我们的保险子公司在公开市场买进类似公司的部份股权,购併对象的价格与机会以及保险公司资金的需求等因素会决定年度资金的配置。

由于这种取得企业所有权的双向手法,及传统会计原则的限制,合併报告盈余无法完全反映公司的实际经济状况,查理跟我同时身为公司股东与经营者,实际上并不太理会这些数字,然而我们依旧会向大家报告公司每个主要经营行业的获利状况,那些我们认为重要的,这些数字再加上我们会提供个别企业的其它资讯将有助于你对它们下判断。