The Competitive Saving Motive Evidence From Rising Sex Ratios and Savings Rates in China

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:319.41 KB

- 文档页数:50

The Importance of Being a Good Motivator Being a good motivator is an essential skill in both personal and professional settings. The ability to inspire and encourage others not only fosters a positive and productive environment but also contributes to individual and collective success. Whether in the workplace, at home, or within a community, the importance of being a good motivator cannot be overstated. In this essay, we will explore the significance of motivation, the qualities of a good motivator, and the impact of effective motivation on individuals and groups. First and foremost, motivation plays a pivotal role in driving individuals to achieve their goals and fulfill their potential. It serves as the catalyst for action, propelling people to overcome challenges, pursue excellence, and persist in the face of adversity. Without motivation, many individuals may struggle to find the determination and resilience needed to pursue their ambitions. Whether it is the pursuit of career advancement, personal development, or the accomplishment of a specific task, motivation provides the impetus for progress and growth. Moreover, the impact of motivation extends beyond individual endeavors to encompass group dynamics and collective aspirations. In a professional context, a good motivator can inspire a team to collaborate effectively, maintain high morale, and strive for shared objectives. By fostering a culture of motivation, leaders can cultivate a cohesive and empowered workforce, leading to enhanced productivity and innovation. Similarly, within a community or social setting, individuals who possess theability to motivate others can ignite a sense of purpose, solidarity, and collective action, thereby contributing to positive social change and cohesion. The qualities of a good motivator are multifaceted and encompass variousattributes that enable them to inspire and empower others. Empathy, for instance, is a fundamental quality that allows motivators to understand the needs, aspirations, and challenges of those they seek to motivate. By demonstrating empathy, motivators can tailor their approach to resonate with the experiences and emotions of individuals, fostering a deeper connection and a more meaningful impact. Furthermore, effective communication skills are essential for conveying motivation in a compelling and persuasive manner. Whether through spoken words, written messages, or non-verbal cues, the ability to articulate a clear andinspiring message is integral to motivating others. Additionally, resilience and optimism are crucial qualities that enable motivators to instill a sense of hope, determination, and perseverance in others. By embodying resilience in the face of setbacks and maintaining a positive outlook, motivators can serve as role models, demonstrating the possibility of overcoming obstacles and achieving success. Moreover, integrity and authenticity are paramount, as individuals are more likely to be motivated by someone they trust and respect. Motivators who uphold ethical principles and act with sincerity are better positioned to engender trust and credibility, thereby amplifying the impact of their motivation. The impact of effective motivation is profound, influencing not only the immediate outcomes of individual and collective endeavors but also the long-term development and well-being of individuals. When individuals are motivated, they are more likely to experience heightened levels of engagement, satisfaction, and fulfillment in their pursuits. This, in turn, can lead to increased productivity, creativity, and a sense of purpose, ultimately contributing to personal and professional growth. Furthermore, effective motivation can have a ripple effect, inspiring others to become motivators themselves, perpetuating a culture of encouragement and empowerment within a community or organization. In conclusion, the importance of being a good motivator cannot be overstated, as it is a catalyst for individual and collective achievement, growth, and well-being. By embodying empathy,effective communication, resilience, optimism, integrity, and authenticity, individuals can cultivate the qualities of a good motivator. The impact of effective motivation extends beyond immediate outcomes, shaping the attitudes, behaviors, and aspirations of individuals and groups. As such, the ability to motivate others is a valuable skill that has the power to transform lives, foster positive environments, and drive meaningful progress.。

动机重要性英语作文标题,The Importance of Motivation。

Motivation plays a crucial role in determining the success or failure of individuals in various aspects oflife. It serves as the driving force behind our actions, influencing our behavior, thoughts, and emotions. Whetherit's pursuing personal goals, achieving academic excellence, or excelling in professional endeavors, motivation acts as the fuel that propels us forward. In this essay, we will delve into the significance of motivation, exploring its various facets and the impact it has on our lives.First and foremost, motivation provides individualswith a sense of purpose and direction. When we are motivated, we have clear goals and objectives that westrive to accomplish. This clarity helps us channel our energy and efforts towards meaningful pursuits, increasing our chances of success. For example, a student who is motivated to excel academically will set specific targetsfor themselves and work diligently towards achieving them. Without motivation, individuals may feel lost or aimless, lacking the drive to pursue their aspirations.Moreover, motivation serves as a catalyst for personal growth and development. It pushes us out of our comfort zones and encourages us to take on new challenges and opportunities. When we are motivated, we are more likely to embrace change and seek out ways to improve ourselves. This continuous process of self-improvement not only enhances our skills and abilities but also boosts our confidence and self-esteem. As a result, we become better equipped to overcome obstacles and thrive in various aspects of our lives.Furthermore, motivation plays a pivotal role in shaping our attitudes and mindset. A motivated individual tends to have a positive outlook on life, seeing challenges as opportunities for growth rather than setbacks. This optimistic mindset enables us to persevere in the face of adversity and maintain a resilient attitude towards achieving our goals. Additionally, motivation fosters asense of determination and resilience, helping us bounce back from setbacks and failures. Instead of being discouraged by obstacles, motivated individuals view them as temporary setbacks and remain steadfast in their pursuit of success.In addition to its personal benefits, motivation also contributes to collective success in group settings. Whether it's a team project, a sports team, or a professional organization, motivated individuals caninspire and energize those around them. Their enthusiasm and dedication can be contagious, motivating others to perform at their best and strive for excellence. In this way, motivation fosters a culture of high performance and collaboration, leading to collective achievement and success.However, it is important to recognize that motivation is not always easy to maintain. External factors such as criticism, rejection, and failure can dampen our enthusiasm and undermine our confidence. Moreover, internal barriers such as fear, self-doubt, and procrastination can hinderour ability to stay motivated. In such instances, it is crucial to cultivate resilience and persistence, drawing upon our inner strength to overcome challenges and stay focused on our goals.In conclusion, motivation is a powerful force thatdrives individuals to pursue their goals, overcome obstacles, and achieve success. It provides us with a sense of purpose and direction, fuels our personal growth and development, and shapes our attitudes and mindset. Moreover, motivation fosters collaboration and collective success in group settings, inspiring others to perform at their best. While maintaining motivation can be challenging, it is essential for realizing our full potential and leading fulfilling lives. By cultivating resilience and perseverance, we can harness the power of motivation to accomplish extraordinary feats and make meaningful contributions to the world.。

《现代货币金融学说》二.单选题(每小题1分。

备选答案中,只有一个最符合题意,请将其编号填入括号内。

1、在直接影响物价水平的诸多因素当中,费雪认为最主要的一个因素是(货币的数量2.凯恩斯认为现代货币的生产弹性具有以下特征(为零。

3.凯恩斯认为与现行利率变动方向相反的是货币的(投机需求。

4.凯恩斯认为货币交易需求的大小主要取决于(收入。

5.凯恩斯认为资本主义经济的病根在于(有效需求不足。

6.提出累积过程理论的经济学家是(维克塞尔。

7.文特劳布认为投机性动机货币需求形成了货币的(金融性流通。

8.新剑桥学派认为借贷资金供给曲线与利率呈(同向变动关系。

9.新剑桥学派认为在通货膨胀的传导过程中主要的传送带是(货币工资率。

10.新剑桥学派在诸多经济政策中把(社会政策放在首要地位。

11.新剑桥学派的政策目标是(保持经济协调。

12.关于经济周期,维克塞尔认为(市场利率与自然利率不一致造成经济波动。

13.凯恩斯以前的传统经济学的核心是(自动均衡。

14.凯恩斯主义经济政策的中心是(膨胀性的财政政策。

15.凯恩斯认为有效需求的价格弹性(小于1 。

16.按凯恩斯的理论,下列正确的是(货币政策伸缩比工资政策更容易。

17.新剑桥学派认为利率由(实物因素和货币因素决定。

18.按新剑桥学派的理论,治理通货膨胀的首要措施是(社会政策。

19.托宾认为在资产组合的均衡点,风险负效用(等于收益正效用。

20.平方根定律认为当利率上升时,现金存货余额(下降。

21.立方根定律货币预防动机需求与利率之间存在(反向变动关系。

22.IS-LM模型中LM曲线是不同的(利率和收入的水平组合轨迹。

23.在IS-LM模型的古典区域,货币投机需求(等于零。

24.当货币供应量增加时,关于IS-LM模型中LM曲线正确的是(向右下方移动。

25.当货币需求增加时,关于IS-LM模型中LM曲线正确的是(向左上方移动。

26.在凯恩斯区域,政府主要通过(财政政策达到目标。

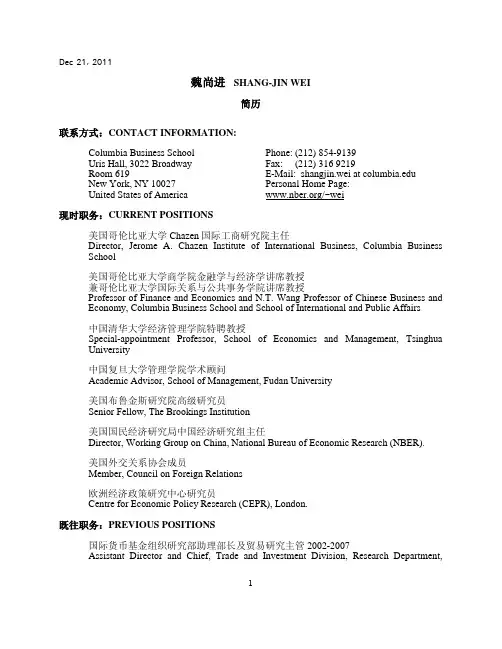

Dec 21, 2011魏尚进SHANG-JIN WEI简历联系方式:CONTACT INFORMATION:Columbia Business School Phone: (212) 854-9139Uris Hall, 3022 Broadway Fax: (212) 316 9219Room 619 E-Mail: shangjin.wei at New York, NY 10027 Personal Home Page:United States of America /~wei现时职务:CURRENT POSITIONS美国哥伦比亚大学Chazen国际工商研究院主任Director, Jerome A. Chazen Institute of International Business, Columbia Business School美国哥伦比亚大学商学院金融学与经济学讲席教授兼哥伦比亚大学国际关系与公共事务学院讲席教授Professor of Finance and Economics and N.T. Wang Professor of Chinese Business and Economy, Columbia Business School and School of International and Public Affairs中国清华大学经济管理学院特聘教授Special-appointment Professor, School of Economics and Management, Tsinghua University中国复旦大学管理学院学术顾问Academic Advisor, School of Management, Fudan University美国布鲁金斯研究院高级研究员Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution美国国民经济研究局中国经济研究组主任Director, Working Group on China, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).美国外交关系协会成员Member, Council on Foreign Relations欧洲经济政策研究中心研究员Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR), London.既往职务:PREVIOUS POSITIONS国际货币基金组织研究部助理部长及贸易研究主管 2002-2007Assistant Director and Chief, Trade and Investment Division, Research Department,1International Monetary Fund布鲁金斯研究所,国际经济学新世纪讲席高级研究员,1999 – 2001The New Century Chair in Trade and International Economics and Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution 1999-2001 (The position was held prior to 1999 by Robert Lawrence and Jeffrey Frankel, and is currently held by Lael Brainard).哈佛大学肯尼迪学院公共政策副教授及助理教授, 1992-2000Associate and Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, 1992-2000.世界银行顾问, 1999-2000Advisor, The World Bank, 1999-2000学历 EDUCATION加利福尼亚伯克利大学经济学博士,1992Ph.D in Economics, University of California, Berkeley, 1992加利福尼亚伯克利大学商业管理硕士(金融学),1991MS in Business Administration (Finance), University of California, Berkeley, 1991宾夕法尼亚州立大学经济学硕士,1988MA in Economics, Pennsylvania State University, 1988复旦大学世界经济专业学士, 1986BA in World Economy, Fudan University, 1986主要研究领域:MAIN RESEARCH FIELDS国际金融,国际贸易,政府治理和改革,中国经济以及宏观经济学。

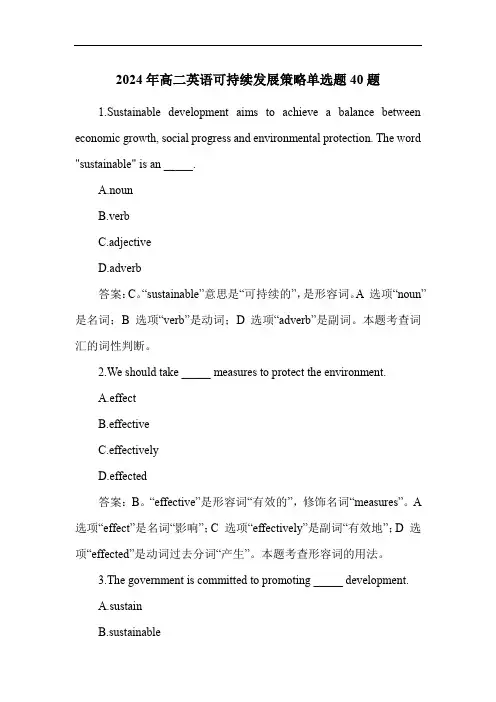

2024年高二英语可持续发展策略单选题40题1.Sustainable development aims to achieve a balance between economic growth, social progress and environmental protection. The word "sustainable" is an _____.A.nounB.verbC.adjectiveD.adverb答案:C。

“sustainable”意思是“可持续的”,是形容词。

A 选项“noun”是名词;B 选项“verb”是动词;D 选项“adverb”是副词。

本题考查词汇的词性判断。

2.We should take _____ measures to protect the environment.A.effectB.effectiveC.effectivelyD.effected答案:B。

“effective”是形容词“有效的”,修饰名词“measures”。

A 选项“effect”是名词“影响”;C 选项“effectively”是副词“有效地”;D 选项“effected”是动词过去分词“产生”。

本题考查形容词的用法。

3.The government is committed to promoting _____ development.A.sustainB.sustainableC.sustainablyD.sustained答案:B。

“sustainable”是形容词“可持续的”,修饰名词“development”。

A 选项“sustain”是动词“维持”;C 选项“sustainably”是副词“可持续地”;D 选项“sustained”是动词过去分词“持续的”。

本题考查形容词修饰名词的用法。

4._____ use of resources is crucial for sustainable development.A.EfficientB.EfficiencyC.EfficientlyD.Efficiencies答案:A。

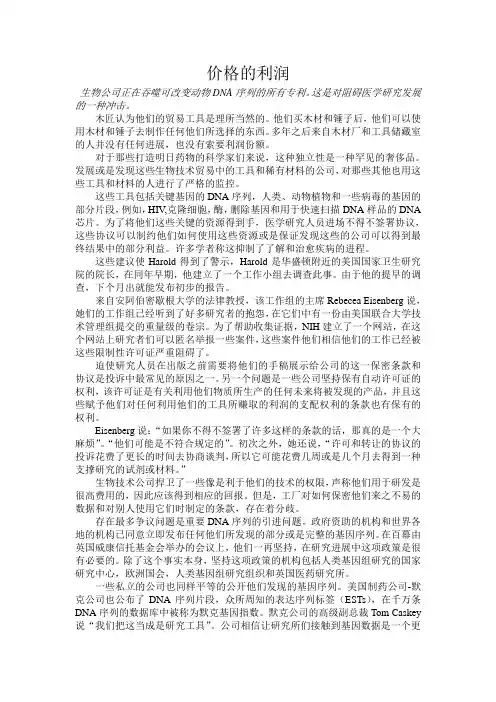

价格的利润生物公司正在吞噬可改变动物DNA序列的所有专利。

这是对阻碍医学研究发展的一种冲击。

木匠认为他们的贸易工具是理所当然的。

他们买木材和锤子后,他们可以使用木材和锤子去制作任何他们所选择的东西。

多年之后来自木材厂和工具储藏室的人并没有任何进展,也没有索要利润份额。

对于那些打造明日药物的科学家们来说,这种独立性是一种罕见的奢侈品。

发展或是发现这些生物技术贸易中的工具和稀有材料的公司,对那些其他也用这些工具和材料的人进行了严格的监控。

这些工具包括关键基因的DNA序列,人类、动物植物和一些病毒的基因的部分片段,例如,HIV,克隆细胞,酶,删除基因和用于快速扫描DNA样品的DNA 芯片。

为了将他们这些关键的资源得到手,医学研究人员进场不得不签署协议,这些协议可以制约他们如何使用这些资源或是保证发现这些的公司可以得到最终结果中的部分利益。

许多学者称这抑制了了解和治愈疾病的进程。

这些建议使Harold得到了警示,Harold是华盛顿附近的美国国家卫生研究院的院长,在同年早期,他建立了一个工作小组去调查此事。

由于他的提早的调查,下个月出就能发布初步的报告。

来自安阿伯密歇根大学的法律教授,该工作组的主席Rebecea Eisenberg说,她们的工作组已经听到了好多研究者的抱怨,在它们中有一份由美国联合大学技术管理组提交的重量级的卷宗。

为了帮助收集证据,NIH建立了一个网站,在这个网站上研究者们可以匿名举报一些案件,这些案件他们相信他们的工作已经被这些限制性许可证严重阻碍了。

迫使研究人员在出版之前需要将他们的手稿展示给公司的这一保密条款和协议是投诉中最常见的原因之一。

另一个问题是一些公司坚持保有自动许可证的权利,该许可证是有关利用他们物质所生产的任何未来将被发现的产品,并且这些赋予他们对任何利用他们的工具所赚取的利润的支配权利的条款也有保有的权利。

Eisenberg说:“如果你不得不签署了许多这样的条款的话,那真的是一个大麻烦”。

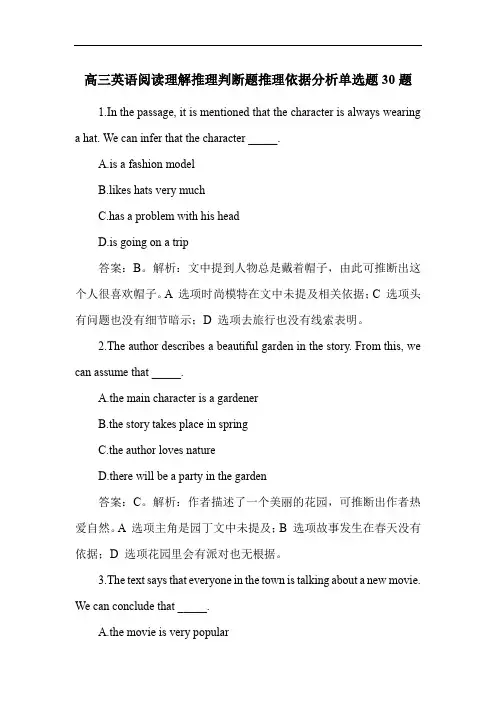

高三英语阅读理解推理判断题推理依据分析单选题30题1.In the passage, it is mentioned that the character is always wearinga hat. We can infer that the character _____.A.is a fashion modelB.likes hats very muchC.has a problem with his headD.is going on a trip答案:B。

解析:文中提到人物总是戴着帽子,由此可推断出这个人很喜欢帽子。

A 选项时尚模特在文中未提及相关依据;C 选项头有问题也没有细节暗示;D 选项去旅行也没有线索表明。

2.The author describes a beautiful garden in the story. From this, we can assume that _____.A.the main character is a gardenerB.the story takes place in springC.the author loves natureD.there will be a party in the garden答案:C。

解析:作者描述了一个美丽的花园,可推断出作者热爱自然。

A 选项主角是园丁文中未提及;B 选项故事发生在春天没有依据;D 选项花园里会有派对也无根据。

3.The text says that everyone in the town is talking about a new movie. We can conclude that _____.A.the movie is very popularB.the town has only one movie theaterC.the movie is free to watchD.the people in the town have nothing else to do答案:A。

《The Advantages of Self-Motivation》高考优秀英语作文Self-motivation is an important life skill that can help to lead a successful and happy life. It is the process of encouraging oneself to work hard and strive for success, both in small daily goals and larger long-term objectives. There are many advantages of self-motivation.Firstly, self-motivation leads to improved productivity. When an individual is able to motivate themselves to work hard and focus on their goals, they can achieve more in less time. This increases the quality and quantity of work done as well as helping to achieve results more quickly.Secondly, self-motivation offers greater independence. With self-motivation, one is able to take control of their own situations and push themselves forward without the help of others. This leads to g reater responsibility and pride in one’s accomplishments. Finally, self-motivation leads to improved self-confidence. When an individual is able to set their own goals and work hard to achieve them, their confidence in their own capabilities increases. This enables them to make decisions more independently and deal with life’s challenges with greater resilience.In conclusion, self-motivation provides many advantages that help to lead a successful and fulfilling life. Having the ability to motivate oneself in any situation gives a person the power to take control of their lives and achieve success.。

2024年高考英语阅读理解考试心理调节历年真题在面对高考英语阅读理解考试时,许多考生常常感到紧张和压力。

然而,正确的心理调节方法能够帮助考生更好地迎接考试挑战。

本文将通过历年真题的分析,为考生提供一些心理调节的建议。

第一篇文章:《The Benefits of Reading for Pleasure》这篇文章主要讨论阅读对个人发展的益处。

作为考生,在面对这样的文章时,可以采取以下心理调节方法:1.正确认识自己的能力和水平,不要轻易自我怀疑。

每个人都有不同的英语能力水平,重要的是在考试前集中精力提升自己的阅读理解能力。

2.遇到不理解的单词或句子,不要过于焦虑。

可以利用上下文推测词义,或者记住这些生词,之后进行查词和记忆。

3.保持积极的心态。

无论文章的难易程度如何,都要相信自己能够运用自己所学的知识来解决问题。

第二篇文章:《The Importance of Sleep for Students》这篇文章探讨了学生睡眠对学习的重要性。

对于这样的主题,考生可以采取以下心理调节方法:1.不要熬夜。

无论是平常的学习还是考试前的复习,保证充足的睡眠是非常重要的。

合理的作息能够提高学习效果。

2.关注自己的睡眠质量。

如果有困扰睡眠的问题,可以尝试创建一个舒适和安静的睡眠环境,避免使用电子设备和过度兴奋的活动。

3.培养良好的学习时间管理习惯。

合理规划学习和休息时间,避免学习压力造成睡眠问题。

第三篇文章:《The Benefits of Outdoor Activities》这篇文章讨论了户外活动对个人身心健康的益处。

考生可以采取以下心理调节方法来应对这样的文章:1.在考前适度进行户外活动。

呼吸新鲜空气、放松身心,可以帮助缓解考试压力,保持良好的精神状态。

2.与朋友一起参与户外活动。

与他人一同享受户外活动的乐趣,可以促进良好的社交关系,提升自信和积极性。

3.保持积极乐观的态度。

户外活动可以增强心理韧性,让考生在面对考试困难时更有冷静和应对能力。

2022年考研考博-考博英语-厦门大学考试全真模拟易错、难点剖析AB卷(带答案)一.综合题(共15题)1.单选题As marketers increase their communication through both print and electronic channels,the opportunity for _______is growing rapidly.问题1选项A.fraudB.jargonC.pledgeD.motivation【答案】A【解析】fraud欺诈, 骗子; jargon行话; pledge保证, 许诺, 抵押; motivation 动机。

句意:当营销人员通过印刷和电子渠道加强沟通的时候,也为欺诈行为提供了快速增长的机会。

选项A符合句意。

2.单选题I get asked about what individuals can do to stay current in a world that somehow keeps_______and repeating patterns ail at the same time.问题1选项A.transformingB.distortingC.convertingD.contorting【答案】A【解析】transform转换, 改变; distort扭曲, 曲解; convert使转变; contort扭曲, 歪曲。

句意:有人问我,在一个不断改变的同时又重复着那些模式的世界里,个人如何才能保持与时俱进。

这里强调的是变化,所以选项A符合句意。

3.单选题It wasn't until the late 19th century that physicians realized that its_______symptoms were all part of the same disease.问题1选项A.perfunctoryB.peremptoryC.perplexingD.perambulatory【答案】C【解析】perfunctory敷衍的; peremptory强制的, 专横的; perplexing复杂的, 令人困惑的; perambulatory巡视的。

动机和方法的重要性英语作文150字The Importance of Motivation and MethodsMotivation is crucial in achieving success in any endeavor. It is the driving force that propels us to set goals, work hard, and overcome challenges. Without motivation, it is easy to become discouraged and give up when faced with obstacles. On the other hand, having a strong motivation can keep us focused and determined to achieve our goals.Methods are also important in achieving success. Having a clear plan and strategy in place can help us stay organized and make progress towards our goals. Methods can help us break down our goals into smaller, manageable tasks, making it easier to track our progress and stay on course.Combining motivation with effective methods is the key to success. When we are motivated, we are more likely to stick with our goals and put in the necessary effort to achieve them. Additionally, having a solid plan in place can help us stay on track and make the most of our time and resources.In conclusion, motivation and methods are both important factors in achieving success. By staying motivated and using effective methods, we can overcome challenges and achieve ourgoals. It is important to keep both aspects in mind as we work towards our objectives.。

竞争力和内驱力的作文英文回答:Competitiveness and self-motivation are two important factors that drive individuals to succeed. Both of these aspects play a significant role in personal and professional development.Competitiveness is the desire to outperform others and achieve success. It pushes individuals to constantly improve themselves and strive for excellence. For example, in a work environment, employees who are competitive are more likely to take on challenging tasks and go the extra mile to stand out from their peers. They are driven by the need to be recognized and rewarded for their achievements. This competitive spirit can lead to innovation and growth, benefiting both individuals and the organizations they work for.On the other hand, self-motivation is the internaldrive that pushes individuals to achieve their goals. It is the ability to set goals, stay focused, and overcome obstacles. Self-motivated individuals do not rely onexternal factors to keep them going; instead, they have an inner fire that propels them forward. For instance, someone who is self-motivated may set a goal to learn a new language and consistently dedicate time and effort towards achieving that goal. They do not need someone else to push them; they are driven by their own desire to succeed.中文回答:竞争力和内驱力是推动个人成功的两个重要因素。

关于竞争力的英语作文The Essence and Significance of Competitiveness in Today's World。

In the dynamic and rapidly evolving world we inhabit, competitiveness has become a defining trait of success. It is not merely a measure of one's ability to outperform others, but rather a comprehensive embodiment of drive, innovation, resilience, and adaptability. This essay delves into the multifaceted nature of competitiveness, exploring its various aspects and the significant role it plays in shaping individuals, organizations, and entire economies.At the individual level, competitiveness is often associated with ambition and aspiration. It is the inner drive that propels individuals to strive for excellence, to push beyond their limits, and to continuously improve. This competitive spirit fosters a culture of self-improvement, where individuals are motivated to learn new skills, enhance their knowledge base, and refine their abilities.In the workplace, this translates into a higher level of productivity, creativity, and overall performance. Furthermore, competitiveness also fosters a sense of accountability and responsibility, as individuals strive to meet the expectations and standards set by their peers and superiors.Organizations, too, thrive on competitiveness. In a fiercely competitive market, businesses must constantly innovate, optimize their operations, and enhance their。

竞争力与内驱力为主题的作文英文回答:Competitiveness and self-motivation are two essential factors that contribute to personal and professional success. They are closely interconnected and play significant roles in driving individuals to achieve their goals and surpass their own limitations.Competitiveness, in essence, is the desire to outperform others and excel in various areas of life. It can be a powerful driving force that pushes individuals to constantly improve themselves and seek new challenges. For example, in a job interview, a competitive individual will strive to showcase their unique skills and experiences in order to stand out from other candidates. This desire to be the best can also motivate individuals to work harder and go the extra mile to achieve success.Self-motivation, on the other hand, refers to theinternal drive and determination to pursue goals without external pressure or influence. It is the ability to stay focused and committed even when faced with obstacles or setbacks. Self-motivated individuals are more likely to take initiative, set high standards for themselves, and persevere until they achieve their desired outcomes. For instance, an entrepreneur with a strong self-motivationwill not be discouraged by initial failures but will continue to learn from mistakes and adapt their strategies to eventually succeed.The relationship between competitiveness and self-motivation can be seen in various aspects of life. In sports, for example, athletes who possess a competitive spirit and self-motivation are more likely to train harder, push their limits, and achieve exceptional performances. Similarly, in the business world, individuals who are both competitive and self-motivated are more likely to take risks, innovate, and succeed in highly competitive markets.中文回答:竞争力和内驱力是个人和职业成功的两个关键因素。

竞争性与内驱力作文英文回答:Competitiveness and intrinsic motivation are two important factors that drive individuals to achieve their goals. Competitiveness refers to the desire to outperform others and to be the best in a particular field or endeavor. On the other hand, intrinsic motivation is the internaldrive and passion that comes from within, pushingindividuals to pursue their goals for personal satisfaction and fulfillment.I have personally experienced both competitiveness and intrinsic motivation in my own life. When I was in school,I was always driven by my competitive nature to excel in my studies and extracurricular activities. I wanted to be at the top of my class and win awards to prove my worth to others. This drive to compete with my peers pushed me to work harder and strive for success in everything I did.However, as I grew older, I realized that true satisfaction and fulfillment come from within. I discovered my intrinsic motivation to pursue my passions and interests, regardless of what others thought or achieved. I found joyin the process of learning and growing, rather than just focusing on the end result or comparing myself to others.For example, when I started learning a new language, I was initially motivated by the desire to be better than my classmates. But as I progressed and saw improvements in my skills, I found a deeper sense of fulfillment andsatisfaction from mastering something new. My intrinsic motivation to learn and grow became stronger than my competitiveness with others.In conclusion, while competitiveness can drive individuals to achieve their goals, it is intrinsic motivation that sustains them in the long run. It is important to strike a balance between the two, using competitiveness to push oneself to improve, but relying on intrinsic motivation to find true satisfaction andfulfillment in the journey.中文回答:竞争性和内驱力是推动个人实现目标的两个重要因素。

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIESTHE COMPETITIVE SAVING MOTIVE:EVIDENCE FROM RISING SEX RATIOS AND SAVINGS RATES IN CHINAShang-Jin WeiXiaobo ZhangWorking Paper 15093/papers/w15093NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH1050 Massachusetts AvenueCambridge, MA 02138June 2009The authors would like to thank Marcos Chamon, Avi Ebernstein, Lena Edlund, Roger Gordon, Ed Hopkins, Tatiana Kornienko, Justin Lin, Olivier Jeanne, Simon Johnson, Nancy Qian, Junsheng Zhang,and seminar participants at the NBER and various universities for helpful discussions, and John Klopfer,Lisa Moorman and Jin Yang for able research assistance. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.© 2009 by Shang-Jin Wei and Xiaobo Zhang. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source.The Competitive Saving Motive: Evidence from Rising Sex Ratios and Savings Rates in China Shang-Jin Wei and Xiaobo ZhangNBER Working Paper No. 15093June 2009JEL No. D1,F3ABSTRACTWhile the high savings rate in China has global impact, existing explanations are incomplete. This paper proposes a competitive saving motive as a new explanation: as the country experiences a rising sex ratio imbalance, the increased competition in the marriage market has induced the Chinese, especially parents with a son, to postpone consumption in favor of wealth accumulation. The pressure on savings spills over to other households through higher costs of house purchases. Both cross-regional and household-level evidence supports this hypothesis. This factor can potentially account for about half of the actual increase in the household savings rate during 1990-2007.Shang-Jin WeiGraduate School of BusinessColumbia UniversityUris Hall 6193022 BroadwayNew York, NY 10027-6902and NBERshangjin.wei@Xiaobo ZhangInternational Food Policy Research Institute2033 K Street, NWWashington, DC 20006x.zhang@”… [A] surge in growth in China and a large number of other emerging market economies … led to an excess of global intended savings relative to intended capital investment. That ex ante excess of savings propelled global long-term interest rates progressively lower between early 2000 and 2005.That decline in long-term interest rates across a wide spectrum of countries statistically explains, and is the most likely major cause of, real-estate capitalization rates that declined and converged across the globe, resulting in the global housing price bubble.” Alan Greenspan, Wall Street Journal, March 11, 20091. IntroductionHigh savings rates in certain countries are said to be a major contributor to the recent housing price bubbles and the global financial crisis by depressing global long-term interest rate in the last decade (Greenspan, 2009). The Chinese national savings rate, at about 50 percent of GDP in 2007, has caught special attention. This savings rate is high in at least three senses. First, it is higher than most other countries, including East Asian countries that are already known to have high savings rates. Second, it is higher than in China’s own past: the gross domestic savings rate as a share of GDP rose by about 15 percentage points since 1990. Finally, it is higher than China’s already-high investment-to-GDP ratio. China’s household savings are approximately half of its national savings. (In 2007, the household savings as a share of the household disposal income was 30%).The purpose of this paper is to test a new hypothesis regarding household savings behavior using Chinese regional and household data. Before doing that, let us review existing explanations in the literature. The first is the life cycle theory (Modigliani, 1970, and Modigliani and Cao, 2004), which predicts that the savings rate rises with the share of working age population in the total population. This explanation doesn’t appear to be consistent with profile of savings at household level (Chamon and Prasad, 2008). The second explanation has to do with a precautionary savings motive in combination with a rise in income uncertainty, which is favored by Blanchard and Giavazzi (2005) and Chamon and Prasad (2008). The problem is that while both pension systems and the public provision of health care in China have been improved since 2003, household savings as a share of disposable income rose sharply during the same period. This time series pattern contradicts the precautionary motive theory. The third explanation is a low level of financial development. This has the same difficulty as the last explanation since the financial system is most likely more efficient today than a few years ago yet thesavings rate still rose. The fourth explanation is cultural norms. But cultural norms tend to be persistent, and therefore are unlikely capable of explaining the visible rise in the savings rate over the last two decades1.In this paper, we suggest that an alternative competitive saving motive may be at work: families with sons compete with each other to raise their savings rate in response to ever rising pressure in the marriage market. Competitive saving by these families spills over to greater savings by other families, possibly through raising the prices of non-tradable goods such as housing. The increased pressure in the marriage market comes from China’s rising sex ratio imbalance, which has made it progressively more difficult for men to get married. As far as we know, we are the first in the literature to propose this hypothesis as an explanation for a rising savings rate in China. Toward the end of the paper, we argue that the explanation is likely applicable to many other countries as well.We provide a series of evidence. First, across provinces, we show that the local savings rate tends to be higher in regions and years in which the local sex ratio (for the pre-marital age cohort) is higher. This continues to be true after we control for local income, social safety net, the age profile of the local population, and province and year fixed effects.Second, in recognition of possible endogeneity of and measurement error in local sex ratios, we employ instrumental variables where the local sex ratio for the pre-marital age cohort is shown to be linked to local financial penalties for violating family planning policies set more than a decade earlier (as Ebenstein, 2008, and Edlund et al, 2008, also document). With two-stage least squares estimation, the effect of local sex ratios on local savings rates remain positive and statistically significant. In fact, the point estimate1 We do not study corporate savings behavior in this paper. The Chinese corporate savings rate has risen sharply in recent years, accounting now for about half of the national savings rate (Kuijs, 2006). The corporate savings behavior is a separate puzzle to be explained. The existing explanation suggests that a combination of state-ownership and windfalls in resource sectors is the primary driver. (The government savings rate is relatively moderate and has turned negative in 2008-09.) We note, however, that a recent paper by Bayoumi, Tong and Wei (2009) discusses China’s corporate savings rate in a global context and casts doubt on the usual interpretation. Because corporate savings rates have been rising globally (Bates, Kahle, and Stulz, 2005; and IMF, 2005), it turns out that the Chinese corporate savings rate is only modestly higher than those of other countries (by2 percentage above the global average savings rate when comparing listed companies across countries). So differences in corporate savings are unlikely to be a big part of the cross country differences in national savings rates. Moreover, comparing corporate savings by Chinese firms of different ownership, in resource and non-resource sectors, Bayoumi, Tong and Wei (2009) do not find evidence that state-owned firms save more than private firms, or that the corporate savings rate is unusually high in resource sectors. This casts doubt on the notion that a high Chinese corporate savings rate is mainly a result of poor corporate governance and inefficiencies tied either to state-ownership or to windfalls in resource sectors.becomes larger. This suggests that an increasing imbalance in the sex ratio causes a rise in the savings rate.Third, we examine household data using household surveys that cover 122 rural counties and 70 cities. While households with a son typically save more than households with a daughter, we do not regard this per se as supportive evidence of our hypothesis, since other channels could account for this difference. Instead, the evidence that we find compelling is that savings by otherwise identical households with a son tend to be greater in regions with a higher local sex ratio. This is something clearly predicted by our hypothesis, but not by any other existing explanations. In addition, we find that savings by households with a daughter do not decline in regions with a high sex ratio, which is consistent with our interpretation that the savings pressure on households with a son spills over to other types of households. We discuss reasons that these patterns at the household level are unlikely to be the outcome of some selection in the data.Finally, we provide several supplementary pieces of evidence. We show that local housing values indeed tend to be higher in regions with a higher local sex ratio, even after taking into account local income. This is direct evidence that the competitive pressure on households with a son in the marriage market may trigger other households to save more just to cope with higher local housing costs. We also provide some evidence that household level savings rates tend to be linked to a wedding event in a family in a quantitatively significant way, and that a groom’s family tends to save more than a bride’s family in preparation for the wedding.We do not wish to claim that no combination of the existing explanations could contribute to a higher savings rate. Instead, we suggest a competitive saving motive as an additional explanation. The estimated effect of a rising sex ratio on the Chinese savings rate is economically significant, and can be projected to become even more important in the foreseeable future. Based on the point estimate (0.74) in the IV regression, a rise in the sex ratio for the pre-marital age cohort from 1.05 to 1.14 (which is actual increase in Chinese sex ratio for the age cohort of 7-21 from 1990-2007) would lead to a rise in the savings rate by 6.7 percentage points, which is 48% of the actual increase in the household savings rate. If we run separate regressions for rural and urban areas, we find that the elasticity of the local savings rate with respect to the local sex ratio is larger inrural areas than in urban areas. The increase in the rural sex ratio is estimated to account about 53% of the actual increase in the rural savings rate from 1990 to 2007.Because the sex ratio imbalance at birth has been increasing steadily since mid-1980s, the imbalance for the pre-marital age cohort will almost surely be higher over the next decade than in the last decade, even if the sex ratio at birth starts to be reserved soon. This implies that the incremental savings rate that is stimulated by the competitive savings motive will almost surely rise in importance in the near future.A high savings rate in a large economy is a significant contributor to global current account imbalances. Once one recognizes that the sex ratio imbalance is a structural factor behind a rising savings rate, it should be clear that a discussion of global imbalances that focuses narrowly on exchange rates or even social safety nets is incomplete. Furthermore, policy actions that improve the economic status of women could potentially reduce the sex ratio imbalance by reducing parental preference for sons (Qian, 2008). A change in the family planning policy that relaxes birth quotas could also reduce the imbalance. Because of their important implications for aggregate savings and current account imbalances, these changes deserve more attention that they receive now.The paper is organized in the following way. In Section 2, we develop the argument more fully, lay out some caveats and possible answers to them, and make connections to related literatures. In Section 3, we provide statistical evidence for our hypothesis. Finally, in Section 4, we conclude and discuss possible future research. A data appendix explains the sources and definitions of the main variables, including measures of sex ratio imbalance and of savings rates.2. Developing the argument: unbalanced sex ratios and competitive savingsIn this section, we first document the evolution of the sex ratio imbalance in the Chinese society over the last three decades. We then explain why this could trigger a race to raise savings rate, and connect this discussion to related literature.From unbalanced sex ratios to “bare branches”Left to the nature, the sex ratio at birth (in a society without massive starvation) is generally around 106 boys per 100 girls (with human biology compensating for a slightlyhigher mortality rate for infant boys than girls). The sex ratio was balanced or slightly below normal in the 1960s and 1970s (mostly likely due to malnutrition). The sex ratio at birth in China was close to be normal in 1980 (with 106 boys per 100 girls), but climbed steadily since the mid-1980s to over 120 boys for each 100 girls in 2005 (Li, 2007; Zhu, Lu, and Hesketh, 2009) and estimated to be 124 boys/100 girls in 2007. By 2005, men outnumbered women at age 25 or below by about 30 million. The excess men cannot be married mathematically. The number of unmarried men -sometimes referred to as “bare branches” in colloquial Chinese - continues to rise as the sex ratio imbalance deteriorates2.Some men may partner off as gays, and others may emigrate or marry women from other countries. Because the scale of the “bare branches” is so large – 30 million men are more than the entire male population of Italy or of many other countries, and because most “bare branches” come from low income households, actions by a small portion of men do not provide a practical solution to the problem. In any case, a rising sex ratio imbalance must imply a diminishing probability that a man will find a bride3.From fear of becoming a “bare branch” to competitive savingsMost men have a desire to get married. It may be safer to say that, in an Asian society, parents of a son strongly prefer for their son to be married. As the competitionfor a dwindling pool of potential wives intensifies, the parents of a son (or a son himself) will try harder to improve the son’s prospects for marriage. Postponing consumption and raising the household savings rate is one such action that families may take. To be successful, a family needs to save more than enough number of other competing families. If all families think the same way, this leads to competitive saving. (Of course, in general2 If some new-born girls are not reported by their parents with hopes to be pregnant again with a son, then the sex ratio imbalance at birth could be overstated in official statistics. To assess the quantitative importance of this possibility, we compare the sex ratio at birth in the 1990 population census with the sex ratio for the 10 years old in the 2000 census. It is reasonable to assume that parents would not hide their 10-year old girls from census-takers in 2000. First, those parents who would like to try for another child in 1990 most likely would have done so already within ten years, and have paid a fine for violating family planning policy by 2000. In addition, there were also positive incentives to report the girls who have reached school age since registration was required for (free) immunization shots and school attendance. Since the sex ratios for both the new-borns in 1990 and the 10 years old children in 2000 were 1.12, we conclude that the under-reported infant girls, as a proportion of total number of new-born girls, are not large enough to make a noticeable distortion to reported sex ratio imbalance. Zhu. Li and Hesketh (2009) reached the same conclusion with a somewhat different methodology.3 A fraud has recently emerged in which some women pretend to be willing to marry bachelors in a rural area in return for a bride price (“cai li”) on the order of RMB 40,000 (about US$5900, or “five years’ worth of farm income”). The women would then run away after the wedding with the bride price (“It’s cold cash, not cold feet, motivating runaway brides in China,” by Mei Fong, Wall Street Journal, June 5, 2009)equilibrium, the total number of unmarried men will not be changed by household savings decision. But an individual family’s desire to improve marriage prospects for its son may lead all families with a son to compete to increase their savings.]The idea that accumulating more wealth may improve one’s chance in the marriage market is not unique to China. For example, pop star Madonna has declared in the hit song, “Material Girl,” that: “We are living in a material world/ and I am a material girl/Some boys try and some boys lie but/ I don’t let them play/ Only boys who save their pennies/ make my rainy day.” So she sees a connection between a man’s savings rate and his success in dating. To be clear, our hypothesis does not require women to be material girls (in China or elsewhere). Indeed, other factors can be important for success in finding a spouse. But other things being equal, as long as more wealth improves a man’s likelihood for marriage, parents with a son (or a son himself) will be encouraged to raise their savings rates. Many factors (such as health and appearance) are difficult to control, but the savings rate is one such thing that parents or men themselves can act on. However, we are not saying that the savings behavior is the only variable that is altered by a rising sex ratio. Instead, parents with a son may do all things in their power to improve their son’s marriage prospect, including perhaps investing more in their son’s education, and pushing him to work harder. The hypothesis in the current paper is that postponing parents’ consumption and raising their savings rate may be one such variable that responds positively to a rising sex ratio.For the sex ratio to affect household savings rates, parents don’t have to know local sex ratio statistics. There is an invisible hand at work. Consider two otherwise identical households with a son, one in a region with a high sex ratio, and the other in a region with a low sex ratio. Parents in the first region would observe or be told by relatives or colleagues with a son that it is very expensive for their sons to find a girlfriend and to marry. The expectation for how much the parents (or the sons) need to contribute to their son’s new household, given costs of housing, cars, furniture, or honeymoons, would differ in the two regions. The types of furniture, cars and honeymoons, and local housing prices may already reflect the degree of competition in a local marriage market, and thus affect the savings required of parents with a son. In otherwords, even without knowledge of local sex ratio statistics, parents with a son may make savings decisions that reflect the local sex ratio.The initial inspiration for the hypothesis comes (from our visits to the National Zoo in Washington DC, and) from the literature on evolutionary biology. In nature, male sea lions or walruses tend to be physically larger than corresponding females; in fact, this pattern holds for most species. A leading hypothesis for why this occurs, sexual dimorphism, conjectures that because bigger and stronger males have an advantage in competing for and retaining females, differences in size are reinforced over time by natural selection (Weckerly 1998). It is likely that humans had to do the same a long time ago; that is why men, on average, are somewhat taller and larger than women. By now, the (sexual) returns to progressively larger males are much lower, if not negative. Men may discover that possessing a larger house, a bigger savings account, and more general wealth is a more effective mating strategy.Existing literature, potential caveats, and counter-argumentsNo other paper in the existing empirical literature that we are aware of makes a connection between sex ratios and savings rates. Nonetheless, a relevant economics literature is the work on status goods, positional goods, and social norms (e.g., Cole, Mailath and Postlewaite, 1992; Hopkins and Kornienko, 2004 and 2009). When allowing certain goods to offer utility beyond their direct consumption value (i.e., through “status,” which in turn could affect the prospect of finding a marriage partner), it is easy to show that consumption and savings behavior can be altered. It is important to point out, however, that the effect of a rising sex ratio imbalance on savings rates is conceptually ambiguous. In particular, when competition in the marriage market increases, men (or their parents) may compete by increasing their conspicuous consumption, if conspicuous consumption effectively signals their attractiveness; this would result in a decline in the savings rate. Our response is that, while conspicuous consumption may increase the frequency of dating, the probability of securing a marriage partner may depend more on showing substantial wealth than on showing off a few flashy goods. Furthermore, a visible way to demonstrate a man’s desirability is by owning a larger house (at least in a developing country like China), which requires a larger savings before the purchase ismade than otherwise. Both signaling strategies can induce households with a son to raise their savings rate. In any case, it is an empirical question as to whether savings rates are positively or negatively related to sex ratio imbalances.The theoretical models in Hopkins (2009) and Hopkins and Kornienko (2009) could be interpreted to predict that a rise in sex ratio imbalances leads to a rise in savings rates. In a possible reading of their models, men compete for potential wives through effort (including by raising their savings rate). Assume that the reward for a higher savings rate is a better chance to win a wife. Men with the lowest savings rates, on the other hand, may not find a wife. As the fraction of men who may stay unmarried increases, men (without coordination) compete by saving more. The resulting level of savings for men is inefficiently high: if all men were to cut their savings by the same amount, the chance for each of them to be matched with a wife would stay the same, but they would have avoided postponing consumption unnecessarily.When the savings effect dominates the conspicuous consumption effect for parents with a son (or unmarried men), would parents with a girl (or unmarried women) save less since a rising sex ratio is a favorable development for them? Indeed, could the reduction in their savings be so much as to completely offset the increase in savings by parents with a son or unmarried men? In a way, we can wait for the data to tell us the answer. Here, it is useful to point out the existence of an opposing force that could potentially raise the savings rate even by parents with a daughter. That force is the price of housing. Parents with a son (or unmarried men) may attempt to increase their competitiveness by buying a larger house, and may bid up housing prices in a region with an unbalanced sex ratio. As a consequence, even parents with a daughter have to save more in order to afford housing. This is a spillover effect4.This discussion has clear implications for the empirical work. First, we need to estimate the net effect of higher local sex ratios on local savings rates. Second, it would be useful to check how savings by households with a son or with a daughter respond to local sex ratios. Third, it would be informative to check if local housing prices are indeed linked to local sex ratios (holding constant other factors).4h When all men save more, the reward for savings by women or parents with a daughter increases, if wealthier men also prefer relatively wealthy women. As a result, parents with a daughter are also more willing to save. For a theoretical model that may deliver this result, see Peters and Siow, 2002. This could be an additional spillover channel.Determinants of sex ratio imbalanceSex ratio imbalance comes almost entirely from sex selective abortions. This, in turn, results from a combination of three factors: (a) parental preference for sons; (b) some limit to the number of children a couple is allowed or wants to have, which for the Chinese is a strict family planning policy; and (c) availability of inexpensive technology to screen the sex of a fetus (Ultrasound B in particular) and to perform abortions.Our empirical work will start with regressions that assume exogenous sex ratios. This assumption can be justified by recognizing that parental preference for sons is part of a culture, and as such, it changes only very slowly. Korea has experienced a sustained increase in its sex ratio imbalance for about 25 to 30 years, which has only recently started to decline; this evidence is consistent with our assumption (Guilmoto, 2007).We nonetheless also report instrumental variable regressions that allow for potential endogeneity of (and measurement error in) sex ratios. The instrumental variables for sex ratio in the pre-marital age cohort explore regional variations in the financial penalty for violating birth quotas, set by regional governments years before newborns grow to marriageable age.3. Statistical EvidenceSince 1980, both the sex ratio for marriage-age youths and the savings rate in China have been rising. In Figure 1, we present a time series plot of standardized versions of both variables,5 with the sex ratio at birth lagged by twenty years. The sex ratio is lagged since the median age of first marriage for Chinese women is about 20. The two standardized variables, visually, are highly correlated (the actual correlation coefficient is 0.822). While this is highly suggestive, it is not a rigorous proof by itself.Panel regressions across Chinese provinces during 1980-2007We start by examining provincial-level data for any association between local savings rates and local sex ratios. We perform a panel fixed effects regression that links a5 standardized variable = (raw variable – mean)/standard deviation.location j’s savings rate in year t with the sex ratio for the appropriate age cohort in that same location and year, controlling for location fixed effects, year fixed effects, and other factors. To be precise, our specification is the following:Savings_rate j,t = β Sex_ratio j,t +X j, tΓj,t + province fixed effects + year dummies +e j,tFollowing Chamon and Prasad (2008), we define the local savings rate by log (income net of taxes / living expenditure).6 This definition is less susceptible to extreme values, and makes the error term more likely to satisfy the normality assumption. We cluster the standard errors by province.Ideally, we would like to know sex ratios for a fixed age cohort in every region and in every year. However, such data are not available as the Chinese population census is carried out only once every few years (in 1982, 1990 and 2000). Moreover, only the 2000 census offers public data for individual age groups at the provincial level. Given these constraints, we make the following short cut: we focus on the sex ratios for the age cohort 7-21 in all years, inferred from the 2000 population census. For the age cohort 7-21 in 2007, we infer their sex ratio from the age cohort 0-19 in the 2000 census, since the two groups should theoretically be the same. Similarly, for the age cohort 7-21 in 1990, we infer their statistics from the cohort 17-31 in the 2000 census; and so on.A caveat with this method is that the actual sex ratio is likely to be different from the inferred one for all years other than 2000. In particular, because the mortality rates for boys and young men are generally slightly higher than those for girls and young women, we may under-estimate the true sex ratios for years before 2000 and over-estimate them for years after 2000. However, under the assumption that measurement errors are common across all regions in any given year (but may vary from year to year), we can eliminate the effect of measurement errors by including year fixed effects in regressions.As control variables, we include both log income and proportions of the local population in the age brackets of 0-19 and 20-59, respectively. Table 1a presents the summary statistics of the major variables used in the provincial level analysis. Table 1b6 Income and expenditure data, which are aggregated based on nationwide rural and urban household surveys, are from various issues of China Statistical Yearbooks.。