Constructions,Lexical Semantics and the Correspondence PrincipleAccounting for Generalizations

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:154.46 KB

- 文档页数:18

Chapter 13 MorphologyThe description of a language deals with all the four facets_ sounds, constructions, meanings and forms of words.The sub-field that studies the functioning of sound-units within the systems of individual languages is called phonology. The branch that is concerned with the meanings of linguistic units is semantics. Morphology overlaps with each of the other three subbranches as a word is a sound unit that has meaning and syntactic function.1.Definitions of MorphologyMorphology: the study of word-formation, or the internal structure of words, or the rules by which words are formed from smaller components -- morphemes.The smallest unit of language in terms of relationship between expression and content, a unit that cannot be further divided into smaller units without destroying or drastically altering the meaning, whether it is lexical or grammatical.Morphology(The study of the internalstructure of words)Inflection (Inflectional morphology)(Deals with the grammatical forms of the same word)Word-formation (Lexical morphology)(Deals with the creation of new words)2. Morpheme, morph, allomorphThe basic unit of morphological description is the morpheme, the smallest unit for grammatical and lexical analysis.Morphemes are abstract units, established for the analysis of word structure.Words can be separated into smaller meaningful units. These minimal meaningful units are known as morpheme.When a word segment represents one morpheme in sound or writing, the segment is a morph. Morpheme are abstract units, which are realized in speech by discrete units known as Morphs. They are actual spoken forms, minimal carriers of meaning.The morph is to a morpheme what a phone is to a phoneme .AllomorphVariant members of a set of morphs areALLOMORPHS of the same morpheme: in-,im-, il-, and ir- are allomorphs of a particularprefix morpheme.Morphemes are distinguished by beingplaced in braces: {and}, {fame}, {in1}.The difference between morph and allomorphs: P119Morpheme(语素)-the minimal units of meaningUndesirabilityIt is formed by combining four distinct units of meaning.Un+desire+able+ityEach of these distinct unit of meaning is a morpheme.Morpheme: the most basic element of meaning.3.Types of morphemes3.1 Free vs. Bound morphemes:Free morphemes: those that may constitute words by themselves, e.g. boy, girl, table, nation. Bound morphemes: those that cannot occur alone, eg -s, -ed, dis-, un-.3.2 Derivational (派生)and inflectional(曲折变化)morphemesInflection: grammatical endings, e.g. plural, tense, comparative, etc.Walk+ingWalk+edWhen inflectional morphemes are attached to other morphemes, they are purely grammatical markers, signifying such concepts as tense, number, case and so on.Derivation: combination of a base and an affix to form a new word, e.g. friend+-ly > friendly. When derivational morphemes are conjoined to other morphemes, a new word is derived, or formed.Tele+commuteMacro+economicsPhysic+ianFad+ismRoot: the base form of a word that cannot be further analyzed without total loss of identity, e.g. friend as in unfriendliness.Roots may befree: those that can stand by themselves, e.g. black+board; nation+-al; orbound: those that cannot stand by themselves, e.g. -ceive in receive, perceive, conceive.Affix: the type of formative that can be used only when added to another morpheme. Normally divided intoprefix (dis-, un-) andsuffix (-en, -ify).Stem: a morpheme or combination of morphemes to which an inflectional affix may be added, e.g. friend+-s; write+-ing, possibility+-es.Representing Word StructureRoots and Affixes (I)1. NV Afteach er2. Roots and Affixes (II)a. Ab. NAf A N Afun kind book sRoots and Affixes (III)c. Vd. VA Af V Afmodern ize destroy ed4.Word-formation4.1 open class and closed classVariable and invariable wordsfollow(s,ing,ed) ; when hello seldom inGrammatical and lexical words(function and Content words)conjunctions, preposition, articles, pronounsbut, and, when, in, off, the, a, his, your.Closed and open class words.pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articlesshe, they, to, on, above, when, where, a, the.nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, some prepositions.(out of, by means of, with regard to)Word class(parts of speech): noun, pronoun, adjective, verb, adverb, preposition, conjunction, interjection, article. Particles, auxiliaries(助词), pro-form, determiners. Inflectional Morphology Derivational/Lexical MorphologyMorphology4.2 Internal structure of words and rules for word formationLike---dislikeOrder---disorderInternal structure: Dis+like dis+orderRules: a negative is formed by adding dis to the end of a verb.Morphology: it refers to the study of the internal structure of words.4.3 Morphological rules of word formationSlowlyClearlyThe ways words are formed are called morphological rules.If a rule can be used freely to form new words, they are called productive morphological rules.Un+adjective=not-adjectiveSad-unsad* (*:unaccepted)Brave-unbrave*Undecided unchecked undeclaredUn-Rule is not as productive for adjectives composed of just one morpheme as for adjective that derived from verbs.BasesVBase for -ed VRoot and base A Af Affor -enblack en ed3.5 CompoundsNounN NN N N Nfire engine green houseVerbV VN V A Vspoon feed white washAdjectiveA AN A A Anation wide red hotMoreComplicatedNN N N N N N Sunday night concert seriesOther Types of Word Formation(I)Clippingprofessor profphysical education phys-edBlendsbreakfast + lunch brunchinformation + commercial informercialOther Types of Word Formation (II)3. Backformationattrition attritoration orat4. Conversiona. V to Nink a (contract)b. N from V(a building) permitc. V from Adirty (a shirt)4.4 Word-formation through lexical change4.4.1 Invention/CoinageKodak, Coke, nylon, Xerox, Bandit, Lycra4.4.2 Blendingtransfer+resistor>transistorsmoke+fog>smogmotorist+hotel>motelbreakfast+lunch>brunchmodulator+demodulator>modemdance+exercise>dancerciseadvertisement+editorial>advertorialeducation+entertainment>edutainmentinformation+commercial>infomercial4.4.3 AbbreviationsClippingBack-clippings: ad(vertisement), chimp(anzee), deli(catessen), exam(ination), hippo(potamus), lab(oratory), piano(forte), reg(ulation)sFore-clippings: (ham)burger, (omni)bus, (violin)cello, (heli)copter, (alli)gator, (tele)phone, (earth)quake.Fore-and-aft clippings: (in)flu(enza), (de)tec(tive).AcronymAIDS, Aids: Acquired Immune Deficiency SyndromeASAP: as soon as possibleCD-ROM: compact disc read-only memoryWASP: white Anglo-Saxon protestantInitialismAI: artificial intelligencea.s.a.p.: as soon as possibleECU: European Currency UnitHIV: human immunodeficiency virusPC: personal computerPS: postscriptRSVP: répondez s’il vous plait (‘please reply’ in French)4.4.4 Back-formationburgle, commentate, edit, peddle, scavenge, sculpt, swindleair-condition, babysit, brainstorm, brainwash, browbeat, dry-clean, house-hunt, housekeep, sightsee, tape-recordarticulate, assassinate, coeducate, demarcate, emote, intuit, legislate, marinate, orate, vaccinate, valuatediagnose < diagnosisenthuse < enthusiasmlaze < lazyliaise < liaisonreminisce < reminiscencestatistic < statisticstelevise < television4.4.5 Analogical creationFrom irregular to regular:work: wrought > workedbeseech: besought > beseechedslay: slew > slayed?go: went > goed???4.4.6 BorrowingFrench: administration, parliament, public, revenue, tax; court, crime, defendant, judge, jury, justice, pardon, sue;army, enemy, guard, officer, peace, soldier, war; clergy, faith, prayer, religion, sermon, service; coat, costume, dress, fashion, frock, jewel, lace;boil, dinner, feast, fry, roast, supper, toast;bargain, butcher, customer, grocer, money, price, value;art, college, music, poet, prose, story, studyLatin: admit, client, conviction, custody, discuss, equal, index, infinite, intellect, library, medicine, minor, opaque, prosecute, pulpit, scribe, scripture, simile, testimonyGreek: acme, bathos, catastrophe, cosmos, criterion, idiosyncrasy, kudos, misanthrope, pathos, pylon, thermSpanish and Portuguese: anchovy, armada, banana, barbecue, cafeteria, cannibal, canoe, canyon, cargo, cask, chilli (or chili), chocolate, cigar, cocaine, cockroach, cocoa, desperado, embargo, guitar, mosquito, negro, port (wine), potato, ranch, renegade, sherry, siesta, tango, tank, tobacco, tomato, vanillaItalian: aria, artichoke, bandit, broccoli, cameo, carnival, casino, concerto, duet, finale, ghetto, graffiti (singular graffito), incognito, inferno, influenza, larva, libretto, macaroni, maestro, mafia, malaria, paparazzi (singular paparazzo), piano, pizza, ravioli, regatta, replica, scampi, solo, soprano, spaghetti, studio, umbrella, vendetta, vermicelli, volcanoDutch: apartheid, booze, boss, brandy, buoy, coleslaw, commando, cookie, cranberry, cruise, deck, decoy, dock, dollar, dope, easel, excise, freight, furlough, gin, kit, knapsack, landscape, luck, onslaught, pickle, reef, sketch, skipper, slim, smuggle, snap, snip, trek, waffle, wagon, yachtHebrew: amen, babel, cabbala (or cabala, kabbala, kabala), camel, cherub, jubilee, manna, messiah, sabbath, satan, seraph, shibbolethArabic: admiral, albatross, alchemy, alcohol, alcove, algebra, alkali, almanac, amber, assassin, candy, cipher (or cypher), harem, hazard, lemon, magazine, nadir, safari, sherbet, sofa, syrup, zenith, zeroIndian: bungalow, cashmere, chutney, cot, curry, dinghy, ginger, guru, juggernaut, jungle, jute, loot,mango, pariah, polo, punch, pundit, pyjamas (or pajamas), shampoo, swastika, thug, toddy, veranda (or verandah), yogaChinese: chop suey, chow, chow mein, ginseng, gung-ho, ketchup (or catchup or catsup), kung fu, tea, tofu (via Japanese), typhoon4.4.7 Types of loan wordsLoanwords:au pair, encore, coup d’etat, kungfu, sputnikLoanblendcoconut: coco (Spanish) + nut (English)Chinatown: China (Chinese) + town (English)Loanshiftbridge: meaning as a card game borrowed from Italian ponteLoan translation, or calquefree verse < L verse libreblack humor < Fr humour noirfound object < Fr objet trouvéThe counterpoint of phonology(音位学)and morphology(形态学)A single phoneme may represent a single morpheme, but they are not identical.boys /bɔɪz/ b. boy’s /bɔɪz/ c. raise /reiz/The counterpoint of phonology(音位学)and morphology(形态学)2. Allomorph: a morpheme may have alternate shapes or phonetic forms.Map---maps--s---/s/Dog---dogs---s---/z/Watch-Watches-es-/iz/Mouse-mice-ic-----/ai/Ox-oxen----en----/n/Tooth-teeth--ee---/i:/Sheep-sheep-ee---/0/。

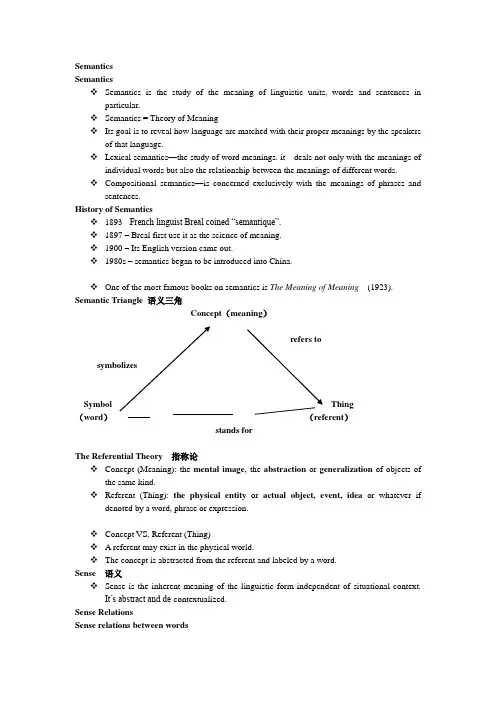

SemanticsSemanticsSemantics is the study of the meaning of linguistic units, words and sentences in particular.Semantics = Theory of MeaningIts goal is to reveal how language are matched with their proper meanings by the speakers of that language.Lexical semantics—the study of word meanings. it deals not only with the meanings of individual words but also the relationship between the meanings of different words.Compositional semantics—is concerned exclusively with the meanings of phrases and sentences.History of Semantics1893 - French linguist Breal coined ―semantique‖.1897 – Breal first use it as the science of meaning.1900 – Its English version came out.1980s – semantics began to be introduced into China.One of the most famous books on semantics is The Meaning of Meaning(1923). Semantic Triangle 语义三角Concept(meaning)refers tosymbolizesSymbol Thing(word)(referent)stands forThe Referential Theory 指称论Concept (Meaning): the mental image, the abstraction or generalization of objects of the same kind.Referent (Thing): the physical entity or actual object, event, idea or whatever if denoted by a word, phrase or expression.Concept VS. Referent (Thing)A referent may exist in the physical world.The concept is abstracted from the referent and labeled by a word.Sense 语义Sense is the inherent meaning of the linguistic form independent of situational context.It’s abstract and de-contextualized.Sense RelationsSense relations between wordsWords are in different sense relations with each other.There are generally 5 kinds of sense relations:1) synonymy 同义2) antonymy 反义3) hyponymy 上下义4) polysemy 一词多义5) homonymy 同音同形异义1. SynonymyIt is the sameness or close similarity of meaning.Words that are close in meaning are called synonyms.2. AntonymyIt is the oppositeness of meaning.Words that are opposite in meaning are antonyms.Oppositeness can be found on different dimensions:Gradable antonymyComplementary antonymyConverse antonymy (relational opposites)Gradable antonymy 分级反义词good/ bad, long /short, narrow/ wideThe members of a pair differ in terms of degree. The denial of one is not necessarily the assertion of the other. There are often intermediate forms between them.Not good≠badHot ---warm---cool---coldComplementary antonymy 互补反义词alive/ dead, male/ female, present/ absent, pass/ fail , boy/ girlIt is characterized by the feature that the denial of one member of the pair implies the assertion of the other and the assertion of one means the denial of the other.Converse antonymy 换位反义词(relational opposites关系对立反义词)buy/ sell, lend/ borrow, before /after,teacher/ student, above /belowThe members of a pair do not constitute a positive-negative opposition. They show the reversal of a relationship between two entities.ExerciseClassify the following pairs of antonyms:Gradable antonymyComplementary antonymyConverse antonymymarried-single male-female hot-coldgive-take big-small awake-asleepnorth-south logical-illogical win-losebuy-sell doctor-patient above-below3. Hyponymy上下义关系It is the sense relation between two words in which the meaning of one word is included in the meaning of another word.HyponymyMusical instruments ---piano flute guitar violin tuba tromboneFish---snapper salmon bass sole troutSalmon---chinook spring coho king sockey4. PolysemyA word is polysemic if it has more than one meaning.Wood:family treea geographical area with many trees5. HomonymyWhen two or more words are the same in pronunciation or in spelling or in both but different in meaning, they are called homonyms.3 types of homonyms:perfect homonyms(同音同形异义词)homographs(同形异义词)homophones (同音异义词).Perfect homonymsPerfect homonyms are words which are the same in both pronunciation and spelling but different in meaning.bank (银行、河岸)bear (容忍、生(孩子))sound (声音、完美的)HomographsHomographs are words which are the same in spelling, but different in pronunciation and meaning."bow" /bəʊ/ -----"弓―"bow" /bau/ -----"鞠躬"HomophonesHomophones are words which are the same in pronunciation, but different in spelling and meaning.tail / taleto / two / toopair / pearsee / seaI / eyepiece / peace。

胡壮麟《语言学教程》(修订版)测试题Chapter 1 Introductions to LinguisticsI. Choose the best answer. (20%)1. Language is a system of arbitrary vocal symbols used for human__________A. contactB. communicationC. relationD. community2. Which of the following words is entirely arbitrary?A. treeB. typewriterC. crashD. bang3. The function of the sentence “Water boils at 100 degrees Centigrade.” is__________.A. interrogativeB. directiveC. informativeD. performative4. In Chinese when someone breaks a bowl or a plate the host or the people present are likely to say“碎碎(岁岁)平安”as a means of controlling the forces which they believes feel might affect their lives. Which functions does it perform?A. InterpersonalB. EmotiveC. PerformativeD. Recreational5. Which of the following property of language enables language users to overcome the barriers caused by time and place, due to this feature of language, speakers of a language are free to talk about anything in any situation?A. TransferabilityB. DualityC. DisplacementD. Arbitrariness6. Study the following dialogue. What function does it play according to the functions of language?—A nice day, isn’t it?— Right! I really enjoy the sunlight.A. EmotiveB. PhaticC. PerformativeD. Interpersonal7. __________ refers to the actual realization of the ideal language user’s knowledge of the rules of his language in utterances.A. PerformanceB. CompetenceC. LangueD. Parole8. When a dog is barking, you assume it is barking for something or at someone that exists hear and now. It couldn’t be sor rowful for some lost love or lost bone. This indicates the design feature of __________.A. cultural transmissionB. productivityC. displacementD. duality9. __________ answers such questions as how we as infants acquire our first language.A. PsycholinguisticsB.Anthropological linguisticsC. SociolinguisticsD. Applied linguistics10. __________ deals with language application to other fields, particularly education.A. Linguistic theoryB. Practical linguisticsC. Applied linguisticsD. Comparative linguisticsII. Decide whether the following statements are true or false. (10%)11. Language is a means of verbal communication. Therefore, the communication way used by the deaf-mute is not language.12. Language change is universal, ongoing and arbitrary.13. Speaking is the quickest and most efficient way of the human communicationsystems.14. Language is written because writing is the primary medium for all languages.15. We were all born with the ability to acquire language, which means the details of any language system can be genetically transmitted.16. Only human beings are able to communicate.17. F. de Saussure, who made the distinction between langue and parole in the early 20th century, was a French linguist.18. A study of the features of the English used in Shakespeare’s time is an example of the diachronic study of language.19. Speech and writing came into being at much the same time in human history.20. All the languages in the world today have both spoken and written forms.III. Fill in the blanks. (10%)21. Language, broadly speaking, is a means of __________ communication.22. In any language words can be used in new ways to mean new things and can be combined into innumerable sentences based on limited rules. This feature is usually termed __________.23. Language has many functions. We can use language to talk about itself. This function is __________.24. Theory that primitive man made involuntary vocal noises while performing heavy work has been called the __________ theory.25. Linguistics is the __________ study of language.26. Modern linguistics is __________ in the sense that the linguist tries to discover what language is rather than lay down some rules for people to observe.27. One general principle of linguistic analysis is the primacy of __________ over writing.28. The description of a language as it changes through time is a __________ study.29. Saussure put forward two important concepts. __________ refers to the abstract linguistic system shared by all members of a speech community.30. Linguistic potential i s similar to Saussure’s langue and Chomsky’s __________.IV. Explain the following terms, using examples. (20%)31. Design feature32. Displacement33. Competence34. Synchronic linguisticsV. Answer the following questions. (20%)35. Why do people take duality as one of the important design features of human language? Can you tell us what language will be if it has no such design feature? (南开大学,2004)36. Why is it difficult to define language? (北京第二外国语大学,2004)VI. Analyze the following situation. (20%)37. How can a linguist make his analysis scientific? (青岛海洋大学,1999)Key:[In the reference keys, I won’t give examples or further analysis. That seems too much work for me. Therefore, this key is only for reference. In order to answer this kind of question, you need more examples. So you should read the textbook carefully. – icywarmtea]I.1~5 BACCC 6~10 BACACII.11~15 FFTFF 16~20 FFFFFIII.21. verbal 22. productivity / creativity 23. metalingual function 24. yo-he-ho25. scientific 26. descriptive27. speech 28. diachronic linguistic29. langue 30. competenceIV.31. Design feature: It refers to the defining properties of human language that tell the difference between human language and any system of animal communication.32. Displacement: It means that human languages enable their users to symbolize objects, events and concepts, which are not present (in time and space) at the moment of communication.33. Competence: It is an essential part of performance. It is the speaker’s knowledge of his or her language; that is, of its sound structure, its words, and its grammatical rules. Competence is, in a way, an encyclopedia of language. Moreover, the knowledge involved in competence is generally unconscious. A transformational-generative grammar is a model of competence.34. Synchronic linguistics: It refers to the study of a language at a given point in time. The time studied may be either the present or a particular point in the past; synchronic analyses can also be made of dead languages, such as Latin. Synchronic linguistics is contrasted with diachronic linguistics, the study of a language over a period of time.V.35.Duality makes our language productive. A large number of different units can be formed out of a small number of elements – for instance, tens of thousands of words out of a small set of sounds, around 48 in the case of the English language. And out of the huge number of words, there can be astronomical number of possible sentences and phrases, which in turn can combine to form unlimited number of texts. Most animal communication systems do not have this design feature of human language.If language has no such design feature, then it will be like animal communicational system which will be highly limited. It cannot produce a very large number of sound combinations, e.g. words, which are distinct in meaning.36.It is difficult to define language, as it is such a general term that covers too many things. Thus, definitions for it all have their own special emphasis, and are not totally free from limitations.VI.37.It should be guided by the four principles of science: exhaustiveness, consistency, economy and objectivity and follow the scientific procedure: form hypothesis –collect data –check against the observable facts – come to a conclusion.Chapter 2 Speech SoundsI. Choose the best answer. (20%)1. Pitch variation is known as __________ when its patterns are imposed on sentences.A. intonationB. toneC. pronunciationD. voice2. Conventionally a __________ is put in slashes (/ /).A. allophoneB. phoneC. phonemeD. morpheme3. An aspirated p, an unaspirated p and an unreleased p are __________ of the p phoneme.A. analoguesB. tagmemesC. morphemesD. allophones4. The opening between the vocal cords is sometimes referred to as__________.A. glottisB. vocal cavityC. pharynxD. uvula5. The diphthongs that are made with a movement of the tongue towards the center are known as __________ diphthongs.A. wideB. closingC. narrowD. centering6. A phoneme is a group of similar sounds called __________.A. minimal pairsB. allomorphsC. phonesD. allophones7. Which branch of phonetics concerns the production of speech sounds?A. Acoustic phoneticsB. Articulatory phoneticsC. Auditory phoneticsD. None of the above8. Which one is different from the others according to places of articulation?A. [n]B. [m]C. [ b ]D. [p]9. Which vowel is different from the others according to the characteristics of vowels?A. [i:]B. [ u ]C. [e]D. [ i ]10. What kind of sounds can we make when the vocal cords are vibrating?A. VoicelessB. V oicedC. Glottal stopD. ConsonantII. Decide whether the following statements are true or false. (10%)11. Suprasegmental phonology refers to the study of phonological properties of unitslarger than the segment-phoneme, such as syllable, word and sentence.12. The air stream provided by the lungs has to undergo a number of modification to acquire the quality of a speech sound.13. Two sounds are in free variation when they occur in the same environment and do not contrast, namely, the substitution of one for the other does not produce a different word, but merely a different pronunciation.14. [p] is a voiced bilabial stop.15. Acoustic phonetics is concerned with the perception of speech sounds.16. All syllables must have a nucleus but not all syllables contain an onset and a coda.17. When pure vowels or monophthongs are pronounced, no vowel glides take place.18. According to the length or tenseness of the pronunciation, vowels can be divided into tense vs. lax or long vs. short.19. Received Pronunciation is the pronunciation accepted by most people.20. The maximal onset principle states that when there is a choice as to where to place a consonant, it is put into the coda rather than the onset.III. Fill in the blanks. (20%)21. Consonant sounds can be either __________ or __________, while all vowel sounds are __________.22. Consonant sounds can also be made when two organs of speech in the mouth are brought close together so that the air is pushed out between them, causing __________.23. The qualities of vowels depend upon the position of the __________ and the lips.24. One element in the description of vowels is the part of the tongue which is at the highest point in the mouth. A second element is the __________ to which that part of the tongue is raised.25. Consonants differ from vowels in that the latter are produced without __________.26. In phonological analysis the words fail / veil are distinguishable simply because of the two phonemes /f/ - /v/. This is an example for illustrating __________.27. In English there are a number of __________, which are produced by moving from one vowel position to another through intervening positions.28. __________ refers to the phenomenon of sounds continually show the influence of their neighbors.29. __________ is the smallest linguistic unit.30. Speech takes place when the organs of speech move to produce patterns of sound. These movements have an effect on the __________ coming from the lungs.IV. Explain the following terms, using examples. (20%)31. Sound assimilation32. Suprasegmental feature33. Complementary distribution34. Distinctive featuresV. Answer the following questions. (20%)35. What is acoustic phonetics?(中国人民大学,2003)36. What are the differences between voiced sounds and voiceless sounds in terms of articulation?(南开大学,2004)VI. Analyze the following situation. (20%)37. Write the symbol that corresponds to each of the following phonetic descriptions; then give an English word that contains this sound. Example: voiced alveolar stop [d] dog. (青岛海洋大学,1999)(1) voiceless bilabial unaspirated stop(2) low front vowel(3) lateral liquid(4) velar nasal(5) voiced interdental fricative答案I.1~5 ACDAA 6~10 DBABBII.11~15 TTTFF 16~20 TTTFFIII.21. voiced, voiceless, voiced 22. friction23. tongue 24. height25. obstruction 26. minimal pairs27. diphthongs 28. Co-articulation29. Phonemes 30. air streamIV.31. Sound assimilation: Speech sounds seldom occur in isolation. In connected speech, under the influence of their neighbors, are replaced by other sounds. Sometimes two neighboring sounds influence each other and are replaced by a third sound which is different from both original sounds. This process is called sound assimilation.32. Suprasegmental feature: The phonetic features that occur above the level of the segments are called suprasegmental features; these are the phonological properties of such units as the syllable, the word, and the sentence. The main suprasegmental ones includes stress, intonation, and tone.33. Complementary distribution: The different allophones of the same phoneme never occur in the same phonetic context. When two or more allophones of one phoneme never occur in the same linguistic environment they are said to be in complementary distribution.34. Distinctive features: It refers to the features that can distinguish one phoneme from another. If we can group the phonemes into two categories: one with this feature and the other without, this feature is called a distinctive feature.V.35.Acoustic phonetics deals with the transmission of speech sounds through the air. When a speech sound is produced it causes minor air disturbances (sound waves). Various instruments are used to measure the characteristics of these sound waves.36.When the vocal cords are spread apart, the air from the lungs passes between them unimpeded. Sounds produced in this way are described as voiceless; consonants [p, s, t] are produced in this way. But when the vocal cords are drawn together, the air from the lungs repeatedly pushes them apart as it passes through, creating a vibration effect. Sounds produced in this way are described as voiced. [b, z, d] are voiced consonants.VI.37.Omit.Chapter 3 LexiconI. Choose the best answer. (20%)1. Nouns, verbs and adjectives can be classified as __________.A. lexical wordsB. grammatical wordsC. function wordsD. form words2. Morphemes that represent tense, number, gender and case are called __________ morpheme.A. inflectionalB. freeC. boundD. derivational3. There are __________ morphemes in the word denationalization.A. threeB. fourC. fiveD. six4. In English –ise and –tion are called __________.A. prefixesB. suffixesC. infixesD. stems5. The three subtypes of affixes are: prefix, suffix and __________.A. derivational affixB. inflectional affixC. infixD. back-formation6. __________ is a way in which new words may be formed from already existing words by subtracting an affix which is thought to be part of the old word.A. affixationB. back-formationC. insertionD. addition7. The word TB is formed in the way of __________.A. acronymyB. clippingC. initialismD. blending8. The words like comsat and sitcom are formed by __________.A. blendingB. clippingC. back-formationD. acronymy9. The stem of disagreements is __________.A. agreementB. agreeC. disagreeD. disagreement10. All of them are meaningful except for __________.A. lexemeB. phonemeC. morphemeD. allomorphII. Decide whether the following statements are true or false. (10%)11. Phonetically, the stress of a compound always falls on the first element, while the second element receives secondary stress.12. Fore as in foretell is both a prefix and a bound morpheme.13. Base refers to the part of the word that remains when all inflectional affixes are removed.14. In most cases, prefixes change the meaning of the base whereas suffixes change the word-class of the base.15. Conversion from noun to verb is the most productive process of a word.16. Reduplicative compound is formed by repeating the same morpheme of a word.17. The words whimper, whisper and whistle are formed in the way of onomatopoeia.18. In most cases, the number of syllables of a word corresponds to the number of morphemes.19. Back-formation is a productive way of word-formations.20. Inflection is a particular way of word-formations.III. Fill in the blanks. (20%)21. An __________ is pronounced letter by letter, while an __________ is pronounced as a word.22. Lexicon, in most cases, is synonymous with __________.23. Orthographically, compounds are written in three ways: __________, __________ and __________.24. All words may be said to contain a root __________.25. A small set of conjunctions, prepositions and pronouns belong to __________ class, while the largest part of nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs belongs to __________ class.26. __________ is a reverse process of derivation, and therefore is a process of shortening.27. __________ is extremely productive, because English had lost most of its inflectional endings by the end of Middle English period, which facilitated the use of words interchangeably as verbs or nouns, verbs or adjectives, and vice versa.28. Words are divided into simple, compound and derived words on the __________ level.29. A word formed by derivation is called a __________, and a word formed by compounding is called a __________.30. Bound morphemes are classified into two types: __________ and __________.IV. Explain the following terms, using examples. (20%)31. Blending32. Allomorph33. Closed-class word34. Morphological ruleV. Answer the following questions. (20%)35. How many types of morphemes are there in the English language? What are they?(厦门大学,2003)36. What are the main features of the English compounds?VI. Analyze the following situation. (20%)37. Match the terms under COLUMN I with the underlined forms from COLUMN II (武汉大学,2004)I II(1) acronym a. foe(2) free morpheme b. subconscious(3) derivational morpheme c. UNESCO(4) inflectional morpheme d. overwhelmed(5) prefix e. calculation Key:I.1~5 AACBB 6~10 BCADBII.11~15 FTFTT 16~20 FTFFFIII.21. initialism, acronym 22. vocabulary23. solid, hyphenated, open 24. morpheme25. close, open 26. back-formation27. conversion 28. morpheme29. derivative, compound 30. affix, bound rootIV.31. Blending: It is a process of word-formation in which a new word is formed by combining the meanings and sounds of two words, one of which is not in its full form or both of which are not in their full forms, like newscast (news + broadcast), brunch (breakfast + lunch) 32. Allomorph: It is any of the variant forms of a morpheme as conditioned by position or adjoining sounds.33. Close-class word: It is a word whose membership is fixed or limited. Pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles, etc. are all closed-class words.34. Morphological rule: It is the rule that governs which affix can be added to what type of base to form a new word, e.g. –ly can be added to a noun to form an adjective.V.Omit.VI.37.(1) c (2) a (3) e (4) d (5) bChapter 4 SyntaxI. Choose the best answer. (20%)1. The sentence structure is ________.A. only linearB. only hierarchicalC. complexD. both linear and hierarchical2. The syntactic rules of any language are ____ in number.A. largeB. smallC. finiteD. infinite3. The ________ rules are the rules that group words and phrases to form grammatical sentences.A. lexicalB. morphologicalC. linguisticD. combinational4. A sentence is considered ____ when it does not conform to the grammati¬cal knowledge in the mind of native speakers.A. rightB. wrongC. grammaticalD. ungrammatical5. A __________ in the embedded clause refers to the introductory word that introduces the embedded clause.A. coordinatorB. particleC. prepositionD. subordinator6. Phrase structure rules have ____ properties.A. recursiveB. grammaticalC. socialD. functional7. Phrase structure rules allow us to better understand _____________.A. how words and phrases form sentences.B. what constitutes the grammaticality of strings of wordsC. how people produce and recognize possible sentencesD. all of the above.8. The head of the phrase “the city Rome” is __________.A. the cityB. RomeC. cityD. the city Rome9. The phrase “on the shelf” belon gs to __________ construction.A. endocentricB. exocentricC. subordinateD. coordinate10. The sentence “They were wanted to remain quiet and not to expose themselves.” is a __________ sentence.A. simpleB. coordinateC. compoundD. complexII. Decide whether the following statements are true or false. (10%)11. Universally found in the grammars of all human languages, syntactic rules that comprise the system of internalized linguistic knowledge of a language speaker are known as linguistic competence.12. The syntactic rules of any language are finite in number, but there is no limit to the number of sentences native speakers of that language are able to produce and comprehend.13. In a complex sentence, the two clauses hold unequal status, one subordinating the other.14. Constituents that can be substituted for one another without loss of grammaticality belong to the same syntactic category.15. Minor lexical categories are open because these categories are not fixed and new members are allowed for.16. In English syntactic analysis, four phrasal categories are commonly recognized and discussed, namely, noun phrase, verb phrase, infinitive phrase, and auxiliary phrase.17. In English the subject usually precedes the verb and the direct object usually follows the verb.18. What is actually internalized in the mind of a native speaker is a complete list of words and phrases rather than grammatical knowledge.19. A noun phrase must contain a noun, but other elements are optional.20. It is believed that phrase structure rules, with the insertion of the lexicon, generate sentences at the level of D-structure.III. Fill in the blanks. (20%)21. A __________ sentence consists of a single clause which contains a subject and a predicate and stands alone as its own sentence.22. A __________ is a structurally independent unit that usually comprises a number of words to form a complete statement, question or command.23. A __________ may be a noun or a noun phrase in a sentence that usually precedes the predicate.24. The part of a sentence which comprises a finite verb or a verb phrase and which says something about the subject is grammatically called __________.25. A __________ sentence contains two, or more, clauses, one of which is incorporated into the other.26. In the complex sentence, the incorporated or subordinate clause is normally called an __________ clause.27. Major lexical categories are __________ categories in the sense that new words are constantly added.28. __________ condition on case assignment states that a case assignor and a case recipient should stay adjacent to each other.29. __________ are syntactic options of UG that allow general principles to operate in one way or another and contribute to significant linguistic variations between and among natural languages.30. The theory of __________ condition explains the fact that noun phrases appear only in subject and object positions.IV. Explain the following terms, using examples. (20%)31. Syntax32. IC analysis33. Hierarchical structure34. Trace theoryV. Answer the following questions. (20%)35. What are endocentric construction and exocentric construction? (武汉大学,2004)36. Distinguish the two possible meanings of “more beautiful flowers” by means of IC analysis. (北京第二外国语大学,2004)VI. Analyze the following situation. (20%)37. Draw a tree diagram according to the PS rules to show the deep structure of the sentence:The student wrote a letter yesterday.Key:I.1~5 DCDDD 6~10 ADDBAII.11~15 TTTTF 16~20 FTFTTIII.21. simple 22. sentence23. subject 24. predicate25. complex 26. embedded27. open 28. Adjacency29. Parameters 30. CaseIV.31. Syntax: Syntax refers to the rules governing the way words are combined to form sentences in a language, or simply, the study of the formation of sentences.32. IC analysis: Immediate constituent analysis, IC analysis for short, refers to the analysis of a sentence in terms of its immediate constituents –word groups (phrases), which are in turn analyzed into the immediate constituents of their own, and the process goes on until the ultimate sake of convenience.33. Hierarchical structure: It is the sentence structure that groups words into structural constituents and shows the syntactic category of each structural constituent, such as NP, VP and PP.34. Trace theory: After the movement of an element in a sentence there will be a trace left in the original position. This is the notion trace in T-G grammar. It’s suggested that if we have the notion trace, all the necessary information for semantic interpretation may come from the surface structure. E.g. The passive Dams are built by beavers. differs from the active Beavers built dams. in implying that all dams are built by beavers. If we add a trace element represented by the letter t after built in the passive as Dams are built t by beavers, then the deep structure information that the word dams was originally the object of built is also captured by the surface structure. Trace theory proves to be not only theoretically significant but also empirically valid.V.35.An endocentric construction is one whose distribution is functionally equivalent, or approaching equivalence, to one of its constituents, which serves as the center, or head, of the whole. A typical example is the three small children with children as its head. The exocentric construction, opposite to the first type, is defined negatively as a construction whose distribution is not functionally equivalent to any of its constituents. Prepositional phrasal like on the shelf are typical examples of this type.36.(1) more | beautiful flowers(2) more beautiful | flowersChapter 5 Meaning[Mainly taken from lxm1000w’s exercises. – icywarmtea]I. Choose the best answer. (20%)1. The naming theory is advanced by ________.A. PlatoB. BloomfieldC. Geoffrey LeechD. Firth2. “We shall know a word by the company it keeps.” This statement represents _______.A. the conceptualist viewB. contexutalismC. the naming theoryD. behaviorism3. Which of the following is NOT true?A. Sense is concerned with the inherent meaning of the linguistic form.B. Sense is the collection of all the features of the linguistic form.C. Sense is abstract and decontextualized.D. Sense is the aspect of meaning dictionary compilers are not interested in.4. “Can I borrow your bike?”_______ “You have a bike.”A. is synonymous withB. is inconsistent withC. entailsD. presupposes5. ___________ is a way in which the meaning of a word can be dissected into meaning components, called semantic features.A. Predication analysisB. Componential analysisC. Phonemic analysisD. Grammatical analysis6. “Alive” and “dead” are ______________.A. gradable antonymsB. relational antonymsC. complementary antonymsD. None of the above7. _________ deals with the relationship between the linguistic element and the non-linguistic world of experience.A. ReferenceB. ConceptC. SemanticsD. Sense8. ___________ refers to the phenomenon that words having different meanings have the same form.A. PolysemyB. SynonymyC. HomonymyD. Hyponymy9. Words that are close in meaning are called ______________.A. homonymsB. polysemiesC. hyponymsD. synonyms10. The grammaticality of a sentence is governed by _______.A. grammatical rulesB. selectional restrictionsC. semantic rulesD. semantic featuresII. Decide whether the following statements are true or false. (10%)11. Dialectal synonyms can often be found in different regional dialects such as British English and American English but cannot be found within the variety itself, for example, within British English or American English.12. Sense is concerned with the relationship between the linguistic element and the non-linguistic world of experience, while the reference deals with the inherent meaning of the。

英语句子论元结构的构式语法研究

构式语法(Construction Grammar)是近十多年来在认知语言学研究中凸现的一种理论体系或研究方法(approach),其迄今为止成果最突出的领域集中在两方面:一是以A.E.Goldberg为代表的论元结构(argument structure)的研究,二是以C.Fillmore和P.Kay为代表的词汇语义(lexical semantics)及标记性构式(markedconstructions)的研究。

但在已有研究中,纯语言理论研究多,语言的习得研究少,以二语为背景的习得研究更少;国内研究大多数以理论介绍、经验总结和英汉对比为主,外语教学相关的研究较少。

针对已有研究的不足,本研究以“中国英语学习者的英语句子学习”为核心问题,在运用构式语法系统地分析英语学习中词汇意义(lexical meaning)、构式意义(constructional meaning)与句子整体意义三者之间的相互关系基础之上,以英语相关技能知识的习得为基本研究维度,从论元结构构式理论研究中国学生英语句子理解模式的发展特点及其主要影响因素,并进一步探讨论元结构构式观对外语学习者句子理解能力的促进性,从而达到丰富构式语法理论在外语教学领域的研究,也为构式语法在外语教学中的应用提供框架的目的。

Goldberg的构式语法研究构式语法理论(Construction Grammar)是当前国际语言学领域研究的热点之一。

它作为一种新兴的语法理论,也引起了我国学术界的广泛关注。

Goldberg认为构式是语言研究的基本单位,是语言研究的中心,在她的专著Constructions:A construction grammar approach to argument structure中全面阐述了构式语法的理论基础、研究单位、研究方法和研究目标。

标签:构式语法理论基础基本单位研究取向构式语法是20世纪80年代末在Charles J.Fillmore的“框架语义学”的基础上兴起的,以认知语言学为理论背景,其主要研究可分为两部分:一是论元结构构式(Argument Structure Construction)的研究,以Adele Goldberg为代表,重点研究论元结构构式的意义、动词与构式之间的关系以及构式之间的关系等理论问题;二是词汇语义(lexical semantics)和有标记构式(marked constructions)的研究,以Charles J.Fillmore和Paul Kay为代表,主要针对一个个具体构式的研究。

Goldberg是构式语法的领军人物,她认为英语中的基本句子都是构式,构式是语言研究的基本单位,是语言研究的中心;构式本身具有意义,该意义并不是其构成成分意义的简单相加,而是独立于句子的构成成分而存在。

一、Goldberg的构式语法理论在Constructions: A construction grammar approach to argument structure一书中,Goldberg全面阐述了构式语法的理论基础、基本研究单位、研究方法和研究目标。

构式语法以框架语义学为基础,以认知语言学为理论背景,坚持功能主义的语言观。

其功能主义的语言观集中体现在Goldberg(1995)的两个著名的假设上。

《英语语言学》导学手册程可拉主编英语语言学教学大纲一、教学目的和要求英语语言学是英语本科专业的自考课程。

本课程的目的是帮助学生系统地学习语言学基本理论知识和研究方法,为从事英语语言教学与研究打下良好的基础。

本课程教学的具体要求是:1.系统掌握语言学的基本理论和基本知识。

2.能应用语言学知识分析各种语言现象。

3.能应用语言学的基本理论来指导中学英语教学。

二、教学内容I. Introduction1. Linguistics1.1 What is linguistics?1.2 Linguistics vs. traditional grammar1.3 The scope of linguistics2. Language2.1 What is language?2.2 The defining properties of human languageII. Phonology1. The phonic medium of language2. Phonetics2.1 What is phonetics?2.2 The speech organs2.3 Narrow and broad transcriptions2.4 Some major articulatory variables2.5 Classification of English speech sounds3. Phonology3.1 Phonetics and phonology3.2 Phone, phoneme and allophone3.3 Phonemic contrast, complementary distribution, and minimal pair3.4 Some rules of phonology3.5 Suprasegmental features---Stress, tone, intonationIII. Morphology1. Morphology1.1 Open classes and closed classes1.2 Internal structure of words and rules for word formation2. Morphemes---the minimal units of meaning3. Derivational and inflectional morphemes4. Morphological rules of word formation5. CompoundsIV. Syntax1. Syntax1.1 What is syntax?1.2 Sentence2. Structuralist approach2.1 Form classes2.2 Constituent structure2.3 Immediate constituent analysis2.4 Endocentric and exocentric constructions2.5 Advantage of IC analysis2.6 Labelled tree diagram2.7 Discontinuous constituents3. Transformational-generative grammar3.1 Competence and performance3.2 Criteria for judging grammars3.3 Generative aspect3.4 Transformational aspect3.5 Deep and surface structures4. The Standard Theory4.1 Components of a TG4.2 The base4.3 Transformations4.4 The form of T-rules4.5 The phonological component4.6 The semantic componentV. Semantics1. Semantics1.1 What is semantics?2. Some views on semantics2.1 Naming things2.2 Concepts2.3 Context and behaviourism2.4 Mentalism3. Lexical meaning3.1 Sense and reference3.2 Synonymy3.3 Polysemy and homonymy3.4 Hyponymy3.5 Antonymy3.6 Relational opposites4. Componential analysis4.1 Componets of meaning4.2 Meaning relations in terms of componential analysis5. Sentence meaning5.1 How to define the meaning of a sentence?5.2 Selectional restrictions5.3 Basic statements about meaning6. The semantic structure of sentences6.1 Extended use of componential analysis6.2 Prediction analysis6.3 Subordinate and downgraded predictions6.4 Advantages of predication analysisVI. Pragmatics1. What does pragmatics study?2. Speech act theory3. Principles of conversation3.1 The co-operative principle3.2 The politeness principleVII. Language change1. Introduction2. Sound change3. Morphological and syntactic change3.1 Change in “agreement” rule3.2 Change in negation rule3.3 Process of simplification3.4 Loss of inflections4. V ocabulary change4.1 Addition of new words4.2 Loss of words4.3 Changes in the meaning of words5. Some recent trends5.1 Moving towards greater informality5.2 The influence of American English5.3 The influence of science and technology6. Causes of language changeVIII. Language and society1. The scope of sociolinguistics1.1 Indications of relatedness between language and society1.2 Sociolinguistics vs. traditional linguistic study1.3 Two approaches in sociolinguistics2. Varieties of language2.1 Varieties of language related to the user2.2 Standard dialect2.3 Varieties of language related to the use3. Communicative competence4. Pidgin and creole5. Bilingualism and diglossiaIX. Language and culture1. Introduction2. What is culture?3. Language and meaning4. Interdependence of language and culture5. The significance of cultural teaching and learning6. Linguistics evidence of cultural differences6.1 Greetings6.2 Thanks and compliments6.3 Terms of address6.4 Colour words6.5 Privacy and taboos6.6 Rounding off numbers7. Cultural overlap and diffusion8. ConclusionX. Language acquisition1. Introduction1.1 Language acquisition1.2 The beginning of language1.3 Stages in first language acquisition1.4 Age and native language acquisition1.5 Common order in the development of language1.6 Different rate of language development2. Phonological development2.1 Regular sound development2.2 Mother and father words2.3 Grammatical development2.4 Vocabulary development2.5 Sociolinguistic development3. Theories of child language acquisition3.1 A behaviorist view of language acquisition3.2 A nativist view of language acquisitionXI. Errors analysis and second language acquisition1. Differences and similarities between first and second language acquisition2. The inadequacy of imitation theory3. Interference3.1 Phonological evidence3.2 Lexical evidence3.3 Grammatical evidence4. Cross-association5. Overgeneralization6. Strategies of communication7. Performance errors三、教学原则和方法1.启发式教学原则:教师积极引导学生理解分析问题,发挥学生的主观能动性,培养他们综合分析问题解决问题的能力。

semantics知识点总结Semantics is the study of meaning in language. It is concerned with how words and sentences are interpreted, how meaning is assigned to linguistic expressions, and how meaning is inferred from language. In this summary, we will explore some key concepts and topics in semantics, including the following:1. Meaning and reference2. Sense and reference3. Truth-conditional semantics4. Lexical semantics5. Compositional semantics6. Pragmatics and semantics7. Ambiguity and vagueness8. Semantic changeMeaning and referenceMeaning is a fundamental concept in semantics. It refers to the content or interpretation that is associated with a linguistic expression. The study of meaning in linguistics is concerned with understanding how meaning is established and conveyed in language. Reference, on the other hand, is the relationship between a linguistic expression and the real world entities to which it refers. For example, the word "dog" refers to the concept of a four-legged animal that is commonly kept as a pet. The study of reference in semantics is concerned with understanding how words and sentences refer to objects and entities in the world.Sense and referenceThe distinction between sense and reference is an important concept in semantics. Sense refers to the meaning or concept associated with a linguistic expression, while reference refers to the real world entities to which a linguistic expression refers. For example, the words "morning star" and "evening star" have the same reference - the planet Venus - but different senses, as they are used to describe the planet at different times of the day. Frege, a prominent philosopher of language, introduced this important distinction in his work on semantics.Truth-conditional semanticsTruth-conditional semantics is an approach to semantics that seeks to understand meaning in terms of truth conditions. According to this view, the meaning of a sentence isdetermined by the conditions under which it would be true or false. For example, the meaning of the sentence "The cat is on the mat" is determined by the conditions under which this statement would be true - i.e. if there is a cat on the mat. Truth-conditional semantics has been influential in the development of formal semantics, and it provides a formal framework for analyzing meaning in natural language.Lexical semanticsLexical semantics is the study of meaning at the level of words and lexical items. It is concerned with understanding the meanings of individual words, as well as the relationships between words in a language. Lexical semantics examines how words are related to each other in terms of synonymy, antonymy, hyponymy, and other semantic relationships. It also explores the different senses and meanings that a word can have, and how these meanings are related to each other. Lexical semantics plays a crucial role in understanding the meaning of sentences and discourse.Compositional semanticsCompositional semantics is the study of how the meanings of words and sentences are combined to create complex meanings. It seeks to understand how the meanings of individual words are combined in sentences to produce the overall meaning of a sentence or utterance. Compositional semantics is concerned with understanding the rules and principles that govern the composition of meaning in natural language. It also explores the relationship between syntax and semantics, and how the structure of sentences contributes to the interpretation of meaning.Pragmatics and semanticsPragmatics is the study of how language is used in context, and how meaning is influenced by the context of language use. Pragmatics is closely related to semantics, but it focuses on the use of language in communication, and how meaning is affected by factors such as the speaker's intentions, the hearer's inferences, and the context in which the language is used. While semantics is concerned with the literal meaning of linguistic expressions, pragmatics is concerned with the implied meaning that arises from the use of language in context.Ambiguity and vaguenessAmbiguity and vagueness are common phenomena in natural language, and they pose challenges for semantic analysis. Ambiguity refers to situations where a linguistic expression has multiple possible meanings, and it is unclear which meaning is intended. For example, the word "bank" can refer to a financial institution or the edge of a river. Vagueness, on the other hand, refers to situations where the boundaries of a linguistic expression are unclear or indistinct. For example, the word "tall" is vague because it is not always clear what height qualifies as "tall". Semantics seeks to understand how ambiguity and vagueness arise in language, and how they can be resolved or managed in communication.Semantic changeSemantic change refers to the process by which the meanings of words and linguistic expressions evolve over time. Over the course of history, languages undergo semantic change, as words acquire new meanings, lose old meanings, or change in their semantic associations. Semantic change can occur through processes such as metaphor, metonymy, broadening, narrowing, and generalization. Understanding semantic change is important for the study of historical linguistics and the diachronic analysis of language.ConclusionSemantics is a rich and complex area of study that plays a fundamental role in understanding the meaning of language. It encompasses a wide range of topics and concepts, and it has important implications for fields such as philosophy of language, cognitive science, and natural language processing. By exploring the key concepts and topics in semantics, we can gain valuable insights into how meaning is established and conveyed in language, and how we can analyze and understand the rich complexity of linguistic expressions.。

词汇语义与句法结构Beth Levin原著Malka Rappaport Hovav詹卫东编译[译者按] 原文是The Handbook of Contemporary Semantic Theory, Shalon Lappin, ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996,一书中的第18章,Chapter 18, Lexical Semantics and Syntactic Structure。

Beth Levin是美国西北大学语言学系副教授。

她的研究集中在动词意义的词汇表示,以及词汇语义学、句法学和形态学之间的交互作用方面。

她是English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation (University of Chicago Press, 1993) 一书的作者,此外她跟Malka Rappaport Hovav合著过Unaccusativity: At the Syntax-Lexical Semantic Interface (MIT Press, 1995)。

在到西北大学工作前,她曾经是MIT认知科学中心的Lexicon工程的主要负责人。

Malka Rappaport Hovav是美国Bar-Ilan大学英语系副教授。

她从1984年起一直在那里工作。

她还是MIT认知科学中心Lexicon工程的研究人员。

她的主要研究兴趣是词汇语义学和形态学,以及上述两个领域跟句法之间的交互关系。

过去的10年是词汇语义学迅速发展的一个时期。

这也部分地导致了当前许多句法理论所普遍接受的一个假设:一个句子的句法性质的诸多方面都是由句中谓词(predicator)1的意义决定的(有关讨论可以参见Wasow 1985)。

在决定句子的句法结构方面,意义所扮演的角色,最引人注目的示例来自谓词论元的句法表达的规律性上。

我们把这叫做“linking regularities”(这个说法来自Carter 1988)。

The Difference between Semantics and PragmaticsSemantics and pragmatics are both linguistic studies of meaning. However there are some differences between them. Therefore how they related, and how do they differ? Now let us analyze it in detail.Semantics can be simply defined as the study of language meaning. It involves many areas such as linguistic, logic, computer science, and psychology and so on. Even if they have some general characters in analysis of semantics, methods and content are definitely difference. The research objects of semantics are the meaning of natural language which can be phrase, sentence, paragraph etc. as we say above semantics is the study of meaning. So this definition naturally leads to the question: what is meaning? Meaning is central to the study of communication, but the question of what meaning really is is difficult to answer. Even linguists do not agree among themselves as to what meaning is.Pragmatics can be defined in various ways. A general definition is that it is the study of how speaker of a language use sentence to effect successful communication. We can simply define it as the study of the use of context. As the process of communication is essentially a process of conveying and understanding meaning in a certain context, pragmatics can also be regarded as a kind of meaning study. It is one of branches of meaning in linguistics study. It is a new object and specially researches the understanding and use of language. It means that pragmatics studies how human being through context to understand and use our own language. In the process of using language, speaker often not only convey language component and symbols. Hearer should go to understand the speaker’s actual intention according to a series of psychological inferring.Another key concept of pragmatics is meaning. Mr. He Zhaoxiong (1981) in his book point out that among these definitions of pragmatics there are two basic concepts one is meaning, another is concept. As we say pragmatics is a comparatively new branch of study in the area of linguistics; its development and establishment in the 1960s and 1970s resulted mainly from the expansion of the study of linguistics, especially that of semantics.Just we talked about in paragraph 2; the question of what meaning really is is difficult to answer. And what makes the matter even more complicated is that philosopher, psychologists, andsociologists all claim a deep interest. The philosophers are interested in understanding the relations between linguistics expressions and what they refer to in the real world, and in evaluating the truth value of linguistic expressions. The psychologists focus their interest on understanding the workings of the human mind through language. This is why it is not surprising to find that books all bearing the title semantics but talk about different things.There are some views concerning the study of meaning. One of the oldest notions concerning meaning, and also the most primitive one, was the naming theory proposed by ancient Greek scholar Plato. It thinks that words are just names or labels for things.The conceptualist view holds that there is no direct link between a linguistic form and what it refers to. Next is contextualism. It means that meaning should be studied in terms of situation, use, concept-elements closely linked with language behavior. The last is behaviorism which attempted to define the meaning of a language from a the situation in which the speaker utters it and the response it calls forth in the hearer,In the study of pragmatics two major traditions have been recognized: the Anglo American tradition and the European continental tradition. The former lays much emphasis on the study of specific language phenomena while the latter does not identify pragmatics with a specific unit of analysis, but it takes pragmatics to be a general cognitive, social, and cultural perspective at the use of language. Within the Anglo-American tradition, pragmatics studies such topics as diesis, speech acts, indirect language, structure of conversation, politeness, cross-cultural communication, and presupposition.As pragmatics and semantics are both linguistic studies of meaning, then how are they related, and how do they differ.The publication of Saussure’s work course in general linguistics in the early 20th century marked the beginning of modern linguistics and at the same time laid down the key note for modern linguistic studies. Language should be studied as a self-contained, intrinsic system. Any serious study cannot afford to investigate the use of language and extra- linguistic factors were not to be considered.For more than half a century this has been the dominant tradition of linguistics study. This is the spirit in which traditional phonology studied the sounds of language, traditional syntax studied the structure of language was considered as something intrinsic, and inherent. A property attachedto language itself. Therefore, meaning of words, meaning of sentences were all studied in isolation from language use.But gradually linguists found that it would be impossible to give an adequate description of meaning if the context of language use was left inconsiderate. But once the notion of context was taken into consideration, semantics spilled over into pragmatics. What essentially distinguishes semantics and pragmatics is whether in the study of meaning the context of use is considered. If it is not considered, the study is confined to the area of traditional semantics. If it is considered, the study is being carried out in the area of pragmatics.So what is context? The notion of context, first noted by the British linguist John Firth in the 1930s in the study of language, is essential to the pragmatic study of language. It is generally considered as constituted by the knowledge shared by the speaker and the hearer. V arious components of shared knowledge have been identified. Knowledge of the language they use, knowledge of what has been said before, knowledge about the world in general, knowledge about the specific situation in which linguistic communication is taking place, and knowledge about each other. Context determines the speaker’s use of language and also the hearer’s interpretation of what is said to him. Without such knowledge, linguistic communication would not be possible, and without considering such knowledge, linguistic communication cannot be satisfactorily accounted for in a pragmatics sense. Look at the following sentences. How did it go? It is cold in here. It was a hot Christmas day so we went down to the beach in the afternoon and had a good time swimming and surfing.Sentence 1 might have occurred in a conversation between two students talking about an examination, or two surgeons talking about an operation, or in some other contexts. Sentence 2 might have been said by the speaker to ask the hearer to turn on the heater or to leave the place, or to apologize for the poor condition of the room, depending on the situation of context. Sentence 3 makes sense only if the hearer has the knowledge that Christmas falls in summer in the southern hemisphere.As has been said before, a sentence is a grammatical concept, and the meaning of a sentence is often studied as the abstract, intrinsic property of the sentence itself in terms of predication. But if we think of a sentence as what people actually utter in the course of communication, it becomes an utterance, and it should be considered in the situation in which it is actually uttered. So it isimpossible to tell if the dog is barking is a sentence or an utterance.It can be either. It all depends on how we look at it and how we are going to analyze it. If we take it as a grammatical unit and consider it a self-contained unit in isolation from context, then we are regarding it as a sentence. If we take it as something a speaker utters in a certain situation with a certain purpose, then we are taking it to be an utterance.Therefore, while the meaning of a sentence is abstract, and decontextualized, that of an utterance is concrete, and context-dependent. The meaning of an utterance is based on sentence meaning. It is the realization of the abstract meaning of a sentence in a real situation of communication, or simply in a context.Now take the sentence my bag is heavy as an example. Semantic analysis of the meaning of the sentence results in the one-place predication BAG. Then a pragmatic analysis of the utterance will reveal what the speaker intends to do with it.The utterance meaning of the sentence varies with the context in which it is uttered. For example, it could have been uttered by a speaker as a straightforward statement, telling the hearer that his bag is heavy. It could also have been intended by the speaker as an indirect, polite request, asking the hearer to help him carry the bag. Still another possibility is that the speaker is declining someone’s request for help. All these are possible interpretations of the same utterance my bag is heavy. How it is to be understood depends on the context in which it is uttered and purpose for which the speaker utters it.While most utterances take the form of grammatically complete sentences, some utterance do not, and some cannot even be restored to complete sentences. For example, good morning! Hi! And Ouch! Are all utterances, which have meaning in communication? If good morning can be restored to I wish you a good morning, we do not know from which complete sentence hi and ouch have been derived.The contextualist view was further strengthened by Bloomfield, who drew on behaviorist psychology when trying to define the meaning of linguistic forms. Behaviorists attempted to define the meaning of a language form as the situation in which the speaker utters it and the response it calls forth in the hearer. This theory, somewhat close to contextualism, is linked with psychological interest. Sense and reference are two terms often encountered in the study of word meaning. They are two related but different aspects of meaning.Sense is concerned with the inherent meaning of linguistic form, the collection of all its features.。

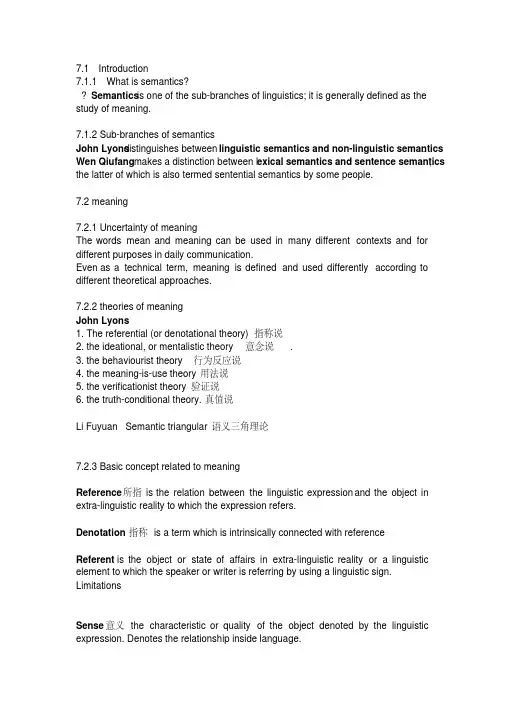

7.1 Introduction7.1.1 What is semantics??Semantics is one of the sub-branches of linguistics; it is generally defined as the study of meaning.7.1.2 Sub-branches of semantics. John Lyons distinguishes between linguistic semantics and non-linguistic semantics, Wen Qiufang makes a distinction between l exical semantics and sentence semantics the latter of which is also termed sentential semantics by some people.7.2 meaning7.2.1 Uncertainty of meaningThe words mean and meaning can be used in many different contexts and for different purposes in daily communication.Even as a technical term, meaning is defined and used differently according to different theoretical approaches.7.2.2 theories of meaningJohn Lyons1.The referential (or denotational theory) 指称说2.the ideational, or mentalistic theory 意念说.3.the behaviourist theory 行为反应说4.the meaning-is-use theory 用法说5.the verificationist theory验证说6.the truth-conditional theory.真值说Li Fuyuan Semantic triangular 语义三角理论7.2.3 Basic concept related to meaningReference所指is the relation between the linguistic expression and the object in extra-linguistic reality to which the expression refers.Denotation指称is a term which is intrinsically connected with referenceReferent is the object or state of affairs in extra-linguistic reality or a linguistic element to which the speaker or writer is referring by using a linguistic sign. LimitationsSense意义the characteristic or quality of the object denoted by the linguistic expression. Denotes the relationship inside language.Extension and intensionExtension is the class of entities to which a linguistic expression is correctly applied Intension is the set of defining properties which determines the applicability of a linguistic expression.Concept is the result of human cognition,reflecting the objective world in human mind.7.2.4 Types of meaningDenotation and connotation 外延意义和内涵意义The denotative meaning of a linguistic form is the person,object, abstract notion, event, or Mate which the word or sentence denotes.We can say that the denotation of a linguistic expression is its dictionary meaning.The main application of the term connotation is with reference to the emotional associations which are suggested by, or are part of the meaning of a linguistic unit, especially a lexical item.Positive neutral negative (Wen Qiufang)7.3Lexical semantics is concerned with the meaning of lexical items.7.3.1 componential analysis成分分析The way to decompose the meaning of a word into its components is known as componential analysis. We can analyze a word as a set of semantic features or semantic components with the values: plus ( + ) or minus ( -)7.3.27.3.2 Semantic field 语义场Words do not exist in isolation. They are always related to each other in one another and form different semantic fields. Semantic field theory is a theory of the German structuralist school:the vocabulary of a language is not simply a listing of independent items, but is organized into areas, or fields, within which words interrelate and define each other in various ways. (Crystal. 1985, 274).7.3.3 Lexical relationsSaeed 8 lexical relations一Form relation 形式关系Homonymy同音(同形)异义关系two or more lexical items are synonyms when they have the same meaningsAbsolute homoyms 同音同形异义词Homopones 同音异义词Homographs 同形异义词二Sense relations 语义关系1.Polysemy一词多义关系 a lexical item has a range of different meanings2.Synonymy同义关系two or more lexical items have the same meanings3.Antonymy反义关系two words are opposite in meaningcomplementary antonymy 互补反义关系Gradable antonymy 等级反义关系Relational opposite 关系对立反义词4.Hyponymy下义关系Hyponym 下义词Hyperonym 上义词三object relations 实体关系1.Meronymy 组成部分与整体关系2.Member-collection 成员与集体关系3.Portion-mass 部分与整体关系Lexical ambiguity is caused by ambiguous words rather than by ambiguous structures and is usually created by polysemy or homonymy.7.4 sentential semanticsSix essential factors for determining sentence meaningi) the meanings of individual words which make up a sentence;ii) grammaticality of a sentence;iii) the linear ordering of the linguistic forms in a sentence;iv) the phonological features like stress and intonation;v) the hierarchical order of a sentence;vi) the semantic roles of the nouns in relation to the verb in a sentence.Nine semantic rolesAgent (施事格)Patient (目标格)Experiencer (经验者)Instrument (工具格)Cause (动因格)Attribute (属性)Recipient (接受者)Locative (方位格)Temporal (时间格)SynonymousEntailContradictPresuppose presupposition triggerTautologyContradictionSemantically anomalous 异常的反常的Predicate谓语argument论元proposition命题。

专八语言集锦(05年——14年专八真题及解析归纳)目录1、2005年 (1)2、2006年 (2)3、2007年 (4)4、2008年 (6)5、2009年 (8)6、2010年 (10)7、2011年 (11)8、2012年 (12)9、2013年 (13)10、2014年 (14)11、附加语言学考研题 (15)2005年38.(考查点:main branches of linguistics) Syntax is the study ofA. language functionsB. sentence structuresC. textual organizationD.word formation答案:B。

解析:Syntax is about principles of forming and understanding correct English sentences,是关于形成和理解正确英语句子的原则。

也就是句子结构。

故选择B。

39.(考察点:design features of language) Which of ale following is NOTa distinctive feature of human language?A. ArbitrarinessB. ProductivityC. Cultural transmissionD. Finiteness答案:D。

解析:题问下面四个选项中,哪一个不是人类语言的主要特征?除Finiteness(有限性)外,选项中的其它的三项Arbitrariness(任意性),Productivity(能产性)和Cultural transmission(文化传递性)在语言学概述部分都提到了。

故选择D。

40. (考察点:人物)The speech act theory was first put forward byA. John SearleB. John AustinC. Noam ChomskyD. M.A,K. Halliday答案:B。

semantics名词解释1. Semantics(semantically)意义学,语义学;关于意义的研究。

在语言学中指对词和句子的含义进行探讨,包括各种词汇和语法构造的意思以及它们在具体语境中的运用方式。

例句:1. Semantics is a branch of linguistics that studies the meaning of words and sentences.意义学是语言学的一个分支,研究词汇和句子的含义。

2. Semantic analysis involves examining the structure and meaning of language.语义分析涉及审查语言的结构和含义。

3. The study of semantics is important in understanding how language is used to convey meaning.研究语义对于理解语言如何传达含义至关重要。

4. The semantics of a sentence can change depending on the context in which it is used.一句话的语义会因其所在的语境而有所改变。

5. In semantics, we look at both the denotative and connotative meanings of words.在语义学中,我们关注词语的指示意义和隐含意义。

6. The semantic content of a text refers to its underlying meaning and themes.一段文本的语义内容指的是其潜在的意义和主题。

7. Understanding the semantics of a language is important in accurately translating it into another language.了解一种语言的语义对于准确翻译它到另一种语言至关重要。