¢0321£ National Animosity and Cross-Border Alliances

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:2.18 MB

- 文档页数:30

国家尊严的英语作文National dignity is a concept that transcends borders and cultures. It represents the respect and honor that a nation commands both within its own borders and internationally. Here is an essay on national dignity:National Dignity: The Backbone of a NationIn the tapestry of global relations, the thread of national dignity stands out as a symbol of pride and strength. It is the collective self-respect that a nation holds, reflecting its history, culture, and achievements. National dignity is not just a matter of pride; it is the foundation upon which a nation's identity and international standing are built.Historical Roots of DignityThe roots of national dignity are often found in a country's rich history and the struggles it has overcome. It is the stories of resilience and triumph that shape a nation's character and instill a sense of dignity in its people. For instance, the United States' national dignity is deeply intertwined with its founding principles of liberty and democracy, which have been tested and upheld through various historical events.Cultural SignificanceCulture plays a pivotal role in defining national dignity. It is through the arts, traditions, and values that a nation expresses its unique identity. The preservation and promotion of cultural heritage are crucial in maintaining a nation's dignity. For example, China's long-standing civilization and its contributions to philosophy, science, and art have been instrumental in shaping its national dignity.Economic and Political StrengthA nation's economic and political strength are also integral to its dignity. Prosperity and stability contribute to a nation's ability to assert itself on the global stage. Countries that are economically robust and politically stable are often seen as dignified, as they can influence global decisions and provide for their citizens.International RelationsIn the realm of international relations, national dignity is upheld through diplomacy and respect for international law. Nations that are respected by their peers are those that adhere to the principles of fairness, cooperation, and mutual respect. This respect is earned through consistent behavior and adherence to the rules that govern global interactions.Citizen ResponsibilityUltimately, the responsibility of upholding national dignitylies with the citizens. It is through the actions and behavior of individuals that a nation's dignity is either reinforced or diminished. Citizens must be educated about the importance of national dignity and encouraged to contribute positively to their country's image.ConclusionNational dignity is a multifaceted concept that encompasses a nation's history, culture, economic strength, political stability, and international standing. It is a precious asset that must be nurtured and protected. As citizens, we must strive to uphold our nation's dignity, both within our borders and on the world stage, ensuring that our country is respected and honored for its unique contributions to humanity.This essay touches upon various aspects that contribute to the concept of national dignity, providing a comprehensive view of what it entails and why it is important.。

The Emblems of Nations: National Flagsand MascotsIn the tapestry of the world, each nation stands unique, distinguished by its symbols and icons. Among these, the national flag and the representative animal occupy a prominent place, reflecting the essence and spirit of the country. These symbols are not just visual representations; they are embodiments of the nation's history, culture, and aspirations.The national flag is the most visible and recognizable symbol of a country. It flies proudly, representing theunity and sovereignty of the nation. The colors, patterns, and designs of the flag often have deep meanings and historical significance. For instance, the flag of the United States, with its red, white, and blue stripes andthe fifty stars representing the states, symbolizes liberty, justice, and the unity of the nation. Similarly, the flagof China, with its red background and the yellow five-pointed star, represents the revolutionary spirit and the leadership of the Communist Party of China.On the other hand, the representative animal, often called the mascot or the national animal, is another symbol that captures the essence of a nation. These animals are chosen based on their unique characteristics, whichresonate with the national identity and values. For example, the eagle is a powerful symbol associated with the United States, embodying the nation's spirit of strength and freedom. The panda, a national treasure of China, is a symbol of peace and friendship, reflecting the country's diplomatic approach.The combination of the national flag and the representative animal creates a powerful narrative thattells the story of a nation. These symbols are not just for display; they are tools of national pride and unity. They inspire citizens to uphold the values and idealsrepresented by these icons and to strive for the betterment of their country.Furthermore, these symbols play a significant role in international relations. When representatives of a country travel to another nation, the national flag and the representative animal accompany them, serving asambassadors of the nation's culture and spirit. They foster a sense of camaraderie and understanding between different countries, promoting peace and cooperation.In conclusion, the national flag and the representative animal are invaluable symbols that define a nation. They are more than just visual representations; they are embodiments of a country's history, culture, and aspirations. These symbols unite citizens, inspire pride, and foster international understanding and cooperation. As we look towards the future, it is essential to cherish and uphold these symbols, ensuring that they continue to represent the best of our nations.**国家象征:国旗与代表动物**在世界的织锦中,每个国家都独一无二,以其符号和图标为标志。

公共场所双语标识英文译法English Translation of Public Signs第4部分体育场馆Part 4: Stadium and Gymnasium1 范围DB11/T 334本部分规定了北京市体育场馆双语标识英文译法的原则。

本部分适用于北京市体育场所中的英文标识译法。

2 规范性引用文件下列文件中的条款通过本部分的引用而成为本部分的条款。

凡是注日期的引用文件, 其随后所有的修改单(不包括勘误的内容)或修订版均不适用于本部分,然而, 鼓励根据本部分达成协议的各方研究是否可使用这些文件的最新版本。

凡是不注日期的引用文件, 其最新版本适用于本部分。

GB/T 16159-1996 汉语拼音正词法基本规则3 术语和定义下列术语和定义适用于本部分。

3.1 体育场stadium3.2 指有400米跑道(中心含足球场), 有固定道牙, 跑道6条以上, 并有固定看台的室外田径场地。

3.3 体育馆gymnasium/indoor stadium3.4 指具备基础服务, 包括运动、健身、娱乐、休闲、比赛以及安全保障等功能的设施。

3.5 游泳馆natatorium4 指用钢筋混凝土或砖石建造池身, 使用人工引水有固定看台的室内游泳池。

5 分类6 体育场馆的英语标识按内容可分为: 警示提示信息、功能设施信息、运动项目及场馆名称等信息。

7 具体要求7.1 警示提示信息译法原则参照本标准通则的规定。

7.2 功能设施信息7.3 体育功能设施涉及许多专门的体育和电视转播专业词汇按国际通用表示方法翻译。

如在奥运场馆中, 主体育场译为Main Stadium、主新闻中心译为Main Press Center、运营区/场馆工作区译为BOH(Back of House)、通行区/场馆公众区译为FOH (Front of House)。

7.4 运动项目信息7.5 遵循国际惯例采用英文直接翻译。

如竞技体操和艺术体操的译法特别容易混淆, 应译为竞技体操Artistic Gymnastics、艺术体操Rhythmic Gymnastics。

小学上册英语第2单元真题试卷英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.The invention of the printing press revolutionized the spread of _____.2.What is 15 divided by 3?A. 3B. 4C. 5D. 6C 53.I want to ________ a new bike.4.What is the main language spoken in France?A. SpanishB. FrenchC. ItalianD. GermanB5.The chemical symbol for scandium is ______.6.The _____ is a region of space with a lot of stars.7.My brother is playing ________.8.The ________ (cello) is a musical instrument.9. A reaction that occurs between an acid and a base produces ______.10.What color is an orange?A. BlueB. OrangeC. GreenD. PurpleB11.What is the opposite of "happy"?A. SadB. AngryC. JoyfulD. ExcitedA12.The chemical formula for barium hydroxide is _____.13.The __________ (未来展望) shapes our dreams.14.What is the main ingredient in a cake?A. FlourB. SaltC. SugarD. ButterA15.I like _______ (观察) the stars at night.16.Liquid nitrogen is used as a _____ (cryogenic fluid) in laboratories.17.What do you call a young female horse?A. ColtB. FillyC. MareD. FoalB18.The fruit salad is ________ (新鲜).19.What is the opposite of 'wet'?A. DryB. DampC. MoistD. All of the aboveD20.His favorite singer is a ________.21.The ______ thrives in tropical climates.22.I love _____ (toys/books).23.What do we call a person who studies physical activity?A. KinesiologistB. PhysiotherapistC. Exercise ScientistD. All of the above24.I want to be a ________ when I grow up.25.I love to watch _____ (蝴蝶) visit the flowers.26.My aunt loves to __________. (种花)27.What do you call a group of lions?A. PackB. PrideC. FlockD. Pod28.What is the name of the process plants use to make food?A. PhotosynthesisB. RespirationC. DigestionD. Fermentation29.The birds _______ (飞) in the sky.30.Many fruits grow from _____ (树) or bushes.31.The _____ (树冠) provides shelter for birds.32. A chemical reaction requires a change in ______.33.I love chocolate ___. (cake)34. A tortoise can live for over a ________________ (百年).35.Can you help me _____ (find/lose) my toy?36. A __________ is a famous mountain range in North America.37.The __________ (文化差异) can enrich social interactions.38.I can see a ___. (star)39.He is my best _____ (同学).40.The _____ (向日葵) is tall and bright.41.What do we call a story that is believed to be true but cannot be proven?A. FableB. MythC. LegendD. FolkloreC42.I like to eat _____ for lunch. (sandwiches)43.The _______ (马) is running fast.44.The __________ is a famous mountain range in the United States. (落基山脉)45.What is 18 + 2?A. 19B. 20C. 21D. 22B46.What do we call the place where we can see old things?A. MuseumB. GalleryC. LibraryD. Theater47.The process of photosynthesis converts sunlight into __________.48.My brother is a ______. He enjoys video editing.49.What is the name of the holiday celebrated in October?A. ThanksgivingB. HalloweenC. ChristmasD. New YearB50.The __________ (国际关系) influence trade and travel.51.Which season comes after summer?A. SpringB. WinterC. FallD. SummerC52.My brother collects ________.53.I found a ___ in my pocket. (coin)54.We visit the zoo to see ______ (动物).55.My dream job is __________ because I want to __________.56.I enjoy ___ (making) new friends.57.我的朋友喜欢 _______ (活动). 她觉得这很 _______ (形容词)58. A ______ (蜗牛) moves very slowly.59.The _____ (栽培) of plants is an important skill.60.What is the term for a young monkey?A. KidB. PupC. InfantD. BabyD Baby61.Kittens are baby _________ (猫).62.The capital of Nicaragua is ________ (马那瓜).63.What do we call an animal that eats both plants and meat?A. HerbivoreB. CarnivoreC. OmnivoreD. InsectivoreC64.What is the term for animals that eat both plants and meat?A. HerbivoresB. CarnivoresC. OmnivoresD. InsectivoresC65.The horse helps on the ______ (农场) and carries loads.66.I love to ________ (探险) in nature.67.What do we call the first meal of the day?A. LunchB. DinnerC. BrunchD. BreakfastD Breakfast68.The goat will eat almost anything, including ______ (纸).69.My uncle is a ____ (doctor) who helps sick people.70.I enjoy ______ (旅行) during the summer.71.What do we call the tool used to measure temperature?A. BarometerB. ThermometerC. HydrometerD. Altimeter72.My sister loves her _________ (玩具马) that she brushes every day.73.What is the capital of Armenia?A. YerevanB. GyumriC. VanadzorD. ArtashatA74.The ______ (小鸟) chirps in the morning.75.What do we call the process of changing from a gas to a liquid?A. EvaporationB. CondensationC. FreezingD. Melting76.Plant cells have a ______ (细胞壁) that protects them.77.The _____ (pollen) is carried by the wind.78.My teacher is ______ (善良). She always helps us with our ______ (功课).79.She is a musician, ______ (她是一位音乐家), performing at concerts.80.My mom makes the best ________.81. A ______ is a type of sea creature with tentacles.82.The __________ is the transition zone between different rock types.83.We will have a ________ (展览) at school.84.What is the capital of the Central African Republic?A. BanguiB. BouarC. BerberatiD. BambariA85.The lizard can lose its _______ (尾巴) to escape.86.__________ changes involve the formation of new substances.87.I can create a show using my ________ (玩具名称).88.The ______ (小鼠) scurries quickly across the floor.89.The ______ helps us learn about physical fitness.90.What is the name of the event where people come together to celebrate a festival?A. GatheringB. PartyC. CeremonyD. FestivalD91.__________ (酶) are biological catalysts that speed up chemical reactions in living organisms.anic compounds contain carbon and ______.93.Carbon dioxide is produced during ______.94.What is the term for a baby goat?A. KidB. CalfC. LambD. FoalA95.The ______ (熊) hibernates during the winter months.96.The garden is ______ with flowers. (full)97.Did you see that _____ (小狗) digging in the dirt?98.What is the capital of Japan?A. TokyoB. BeijingC. SeoulD. BangkokA99.中国的历史上有很多著名的________ (battles),如赤壁之战。

![[整理版]英语国家标志性动物和国家珍惜动物](https://uimg.taocdn.com/e91ba5243868011ca300a6c30c2259010202f310.webp)

英语国家标志性动物和国家珍惜动物Animals have always been used to represent certain human characteristics. Countries also use animals as symbols. From eagles to lions, many countries use an animal to show its national spirit and character.人们常常用动物来表现人类的性格。

许多国家把鹰和狮子等动物奉为国家的象征,用它们来展现民族精神和民族性格。

The image of an eagle is on the US President's flag, and on the one-dollar bill. The bald eagle is a large, powerful, brown bird with a white head and tail. The term "bald" does not mean that this bird lacks feathers. Instead, it comes from the old word piebald, that means, "marked with white".美国总统印章和一美元币上都有白头鹰的形象。

白头鹰体形很大,动作有力,羽毛呈灰色,脑袋和尾巴呈白色。

白头鹰英文名字中的"bald"并不是指它没有羽毛。

追根溯源,这个词其实来自一个旧词"piebald",意思是“黑白相间的”。

The US declared that the eagle was its national bird in 1782. It was chosen because of "its long life, great strength, and noble looks".1782年,美国宣布白头鹰为国鸟。

小学上册英语第3单元综合卷英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.In a solution, the substance present in the greatest amount is called the ________.2. A ________ is a large, flat area of grassland.3.Fruits provide essential ______ for our bodies. (水果为我们的身体提供必需的营养。

)4.I like to _____ my lunch at school. (eat)anic compounds contain _______ atoms.6.What is the largest mammal in the world?A. ElephantB. Blue WhaleC. GiraffeD. RhinocerosB7.She has a beautiful __________.8.She is a good ________.9.He is playing with his ___. (toys)10.The main component of hemoglobin is _____.11.Which animal is known for its long neck?A. ElephantB. GiraffeC. ZebraD. Kangaroo12.The United Kingdom is made up of England, Scotland, Wales, and ________.13.The rabbit hops _____ (quickly/slowly).14.What is the largest organ in the human body?A. HeartB. LiverC. SkinD. Brain15.I see a _____ (mouse) in my house.16.The ________ is a colorful bird that sings.17.The _______ (犬) is often considered man's best friend.18.I have a lot of fun with my toy ____ set. (玩具名称)19.The __________ is perfect for a picnic in the park. (天气)20. A ______ (骆驼) can survive without water for days.21.The __________ (葡萄牙) was a major player in the Age of Exploration.22.What do we call the study of heredity and variation?A. GeneticsB. EvolutionC. BiologyD. Ecology23.What is the capital city of Italy?A. RomeB. FlorenceC. VeniceD. MilanA24. A solution that does not conduct electricity is called a _______.25.The monkey swings from ______ to ______.26.What do we use to write?A. BrushB. PencilC. SpoonD. ForkB27.The _____ (草地) is perfect for playing outside.28.I enjoy making my own games using my ________ (玩具名). It sparks my imagination.29.The ________ Revolution began in the late 18th century.30.My ________ (玩具名称) can change shapes easily.31.The children are ___ in the park. (running)32.The octopus can taste with its ______ (触手).33.What animal is known as “man's best friend”?A. CatB. DogC. RabbitD. Hamster34.Cosmic rays are high-energy particles that travel through ______.35.The capital of Samoa is __________.36. A _____ (种子库) preserves different types of seeds.37.What is the opposite of "cold"?A. CoolB. WarmC. HotD. FreezingC38.I have a toy _______ that can spin and twirl around.39.I enjoy drawing and painting in my free time.40.What is the name of the largest freshwater lake in the world?A. Lake SuperiorB. Lake VictoriaC. Caspian SeaD. Lake BaikalD41.The capital of Russia is _____ (51).42.My sister loves to _______ (动词) in the park. 我们常常一起 _______ (动词).43.The ______ teaches us about famous historical figures.44.I enjoy ______ with my family.45.__________ (测量工具) are vital for accurate chemical analysis.46.The __________ (Renaissance) was a period of great cultural revival in Europe.47.The ancient Egyptians used _______ to write on. (纸草)48.The chemical formula for silver nitrate is ______.49.My mom cooks _______ (美味的) food.50. A shooting star is also called a ______.51. A __________ is a natural phenomenon that can impact ecosystems.52.What do we call the outer layer of the Earth?A. CrustB. CoreC. MantleD. LithosphereA53.The ant is strong for its _________ (大小).54.What is the capital city of the USA?A. New YorkB. WashingtonC. Los AngelesD. ChicagoB55.My dream is to have a room full of ____. (玩具名称)56.What is the name of the famous wizard in "Harry Potter"?A. DumbledoreB. GandalfC. MerlinD. HagridA57.My teacher encouraged us to create our own ________ (漫画). I drew a funny ________ (角色).58.The _______ of sound can be affected by the distance from the source.59. A strong acid has a pH value that is ________ than60.We can _______ (跑步) fast.61.What is the capital of Peru?A. LimaB. QuitoC. BogotáD. SantiagoA62.Emma is a ______. She likes to read stories.63.The capital of Pakistan is __________.64.The _____ (土地) must be prepared before planting.65. A concentrated solution contains a high amount of ______.66.What is the main ingredient in salad?A. MeatB. VegetablesC. BreadD. Cheese67.Hydrogen is the simplest and most abundant _____.68.My _______ (蜗牛) is very slow and steady.69.The _____ (植物组织) is made up of different cells.70.My cousin is a talented ____ (dancer).71.What is the main ingredient in chocolate chip cookies?A. SugarB. FlourC. Chocolate chipsD. Eggs72.What is a comet mostly made of?A. RockB. MetalC. Ice and dustD. Gas73. A puppy loves to play with ______ (球).74.I read a _____ (书) every night.75.What is the name of the famous statue in New York Harbor?A. Christ the RedeemerB. Statue of LibertyC. DavidD. Venus de MiloB76.What is the opposite of "happy"?A. SadB. ExcitedC. JoyfulD. AngryA77.The _____ (自然资源) includes all the plants and animals.78.The _____ (watermelon) is refreshing.79.Did you see that _____ (小狗) rolling in the grass?80.My brother has a deep love for __________ (自然).81.The molecule responsible for carrying oxygen in the blood is ______.82. A __________ has a flat body and can often be found in rivers.83.We _____ (play/plays) games on weekends.84. A force can change an object’s ______.85.What is the opposite of "speak"?A. TalkB. WhisperC. SilenceD. ShoutC86.What is the capital city of Australia?A. SydneyB. MelbourneC. CanberraD. Brisbaneets have a bright tail that points away from the _______.88.What do we call an animal that lays eggs?A. MammalB. ReptileC. BirdD. Both B and C89.My cousin is very __________ (适应力强).90. Wall is one of the most famous ________ (地标). The Grea91.What is the name of the famous theme park located in California?A. DisneylandB. Universal StudiosC. SeaWorldD. LegolandA92.What do we call the act of working together toward a common goal?A. CooperationB. CollaborationC. TeamworkD. PartnershipCmunity meeting) discusses local issues. The ____94.I enjoy ______ (与朋友互动).95.The nurse plays a vital role in _____ (患者护理).96.What do you call the written record of events?A. HistoryB. ScienceC. GeographyD. MathA97.How many senses do humans have?A. 4B. 5C. 6D. 7B98.My uncle plays soccer on the ____ (weekends).99. A ____ is a friendly animal that enjoys human companionship. 100. A shadow is formed when light is ______.。

小学上册英语第4单元真题英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.The ________ is a tiny insect that helps flowers bloom.2.The type of energy that can change the state of matter is called _______ energy.3.The Earth’s shape is not a perfect sphere; it is an ______.4.在中国历史中,________ (philosophers) 的思想对社会发展产生了深远的影响。

5.Which insect produces honey?A. AntB. BeeC. FlyD. MosquitoB6.Which animal lives in a den?A. LionB. BearC. CatD. Dog7.I want to be a ________ (医生) when I grow up.8.I saw a _______ playing in the grass (我看到一只_______在草地上玩).9. A _______ is a mixture where the components can be distinguished.10.What color are most leaves in summer?A. YellowB. GreenC. RedD. BrownB11.I can ___ (sing) in the shower.12.What do you call the study of living things?A. BiologyB. ChemistryC. PhysicsD. GeologyA13.I enjoy _______ (在公园散步).14.The __________ is a major river that flows through France. (塞纳河)15.What is the name of the second-largest planet in our Solar System?A. SaturnB. JupiterC. NeptuneD. Uranus16.The symbol for argon is _______.17.The ________ is very gentle and kind.18.Black holes can be detected by observing their effects on nearby _______.19.We had a race with our toy ____. (玩具名称)20.I have a toy ________ (飞机) that can fly high in the ________ (天空).21.My dad works as a _______ (工程师).22.The ________ (lantern) lights up the night.23.How many players are there on a soccer team?A. 7B. 9C. 11D. 13C24.The ancient Romans were known for their _____ and engineering.25.The _______ (马) has a long mane.26.What is the name of the famous rock formation in the USA?A. Mount RushmoreB. Grand CanyonC. Devil's TowerD. All of the above27.Which planet is known for its rings?A. MarsB. JupiterC. SaturnD. NeptuneC28.What is the capital of Qatar?A. DohaB. Al RayyanC. Al WakrahD. LusailA29. A cactus can survive in very _______ places.30.The girl is very ________.31.My friends call me “.”32.My ______ enjoys playing with his friends.33.I enjoy ________ (动词) new toys with my family. Going to the toy store is always an exciting ________ (名词).34.The __________ Sea is located between Europe and Asia.35.The park is ______ (perfect) for picnics.36.What is the capital of Burundi?A. GitegaB. BujumburaC. NgoziD. MuyingaA37.I have a soft ______ (玩偶). I hug it when I feel ______ (伤心).38.This girl, ______ (这个女孩), enjoys painting landscapes.39.What do we call the process of a caterpillar becoming a butterfly?A. MetamorphosisB. GrowthC. EvolutionD. TransformationA40.The _______ (Hopi) are one of the Native American tribes in the Southwest.41. A _______ is a large body of saltwater.42.I planted ______ (花) in my garden. I hope they bloom ______ (快).43.What is the capital of India?A. MumbaiB. DelhiC. KolkataD. BangaloreB44.Which creature is known for spinning webs?A. AntB. SpiderC. BeeD. Fly45.What do we call a person who studies ancient artifacts?A. HistorianB. ArchaeologistC. GeologistD. AnthropologistB46.What do you call a person who creates art?A. ArtistB. PainterC. SculptorD. IllustratorA47.He is my __________. (舅舅)48.The ancient Greeks made significant contributions to ________ (数学).49.What is the name of the ocean that is located between Africa and Australia?A. Atlantic OceanB. Indian OceanC. Pacific OceanD. Arctic OceanB50.The main gases in air are nitrogen and _______.51.War was fought indirectly through ________ (代理战争). The Cold52.What is the color of a typical eggplant?A. GreenB. YellowC. PurpleD. RedC53.advocacy coalition) amplifies voices for change. The ____54.__________ are used to show the arrangement of electrons in an atom.55.What do we call a person who plays a musical instrument?A. MusicianB. ComposerC. ConductorD. SingerA56.My dad likes to _______ (动词) on weekends. 他觉得这个活动很 _______ (形容词).57.What do you call a group of wolves?A. PackB. FlockC. HerdD. School58.Listen and tick.听录音,勾出每个人所喜欢的颜色。

![【国标舞】中英文名称对照表[完整版]](https://uimg.taocdn.com/ebf735d69a89680203d8ce2f0066f5335a8167ce.webp)

【国标舞】中英文名称对照表[完整版]1、国际标准舞(体育舞蹈)英文常用词汇和术语名称的翻译(1)组织名称World Dance Council 世界舞蹈理事会简称W.D.C.World DanceSport Federation 世界体育舞蹈联合会简称W.D.S.F.Imperial Society of Teacher of Dancing 英国皇家舞蹈教师协会简称I.S.T.D.International Dance Teather’s Association 国际舞蹈教师协会简称I.DT.A.International Council of Ballroom Dancing 国际交际舞理事会简称I.C.B.D.International Council of Ballroom Danving 国际业余舞蹈家理事会简称I.C.AD.China Ballroom Dance Federation中国国际标准舞总会简称C.B.D.F.China Dance Sport Federation中国体育舞蹈联合会简称C.D.S.F.(2)组织名称中国国标舞总会 CBDF国标舞特别舞台 Full Moon美国国标舞 Ballroom Dancing世界华人国标舞联合会 WUCBD国标舞误闯高中校园 Ballroom Adventure国标舞-探戈音乐精选 Ballroom Dance Collection - Tango黄宇曛可爱国标舞 Shine Huang跳国标舞的小女孩 Dancing Girl Miss Wang XY国标舞-伦巴音乐精选 Ballroom Dance Collection ; Ballroom Dance Collection -(3)舞蹈相关词汇1 Dancing 舞蹈、跳舞2 Ballroom Dancing 舞厅舞、交际舞国际体育舞蹈的通称3 Social Dancing 社交舞、交际舞舞会舞的别称4 Modern 摩登的、现代的5 Standard Dancing 标准舞6 International Style of Ballroom Dancing 国际标准交际舞7 Competition Dancing 竞技舞8 Formation Dancing 编队舞、集体舞9 Sports Dancing 体育舞蹈10 Waltz 华尔兹11 Tango 探戈12 Slow Foxtrot 狐步13 Quick Step 快步14 Viennese Waltz 维也纳华尔兹15 Latin American Dancing 拉丁美洲舞16 Rumba 伦巴 17 Samba 桑巴18 Cha-Cha-Cha 恰恰恰19 Paso Doble(西) Paso Double(法)斗牛舞\帕索多布累20 Jive 牛仔舞(4)赛场词汇1 Parrty 舞会2 Partner 舞伴\合作伴侣3 Competition 竞赛\比赛4 Champion 冠军5 Championship 锦标赛\冠军赛6 Amalgamation 组合7 Judge 裁判8 Adjudicator 舞蹈比赛评委9 Professional 专业的,职业的10 Amateur 业余的,爱好者11 Associate 学士12 Member 会士13 Fellow 范士14 Round (第x)轮,圈15 Final 决赛(5)舞蹈术语名称1 Slow 慢的记录符号为S2 Quick 快的记录符号为Q3 Double 双的,加倍的4 Repeat 重复,反复5 Natural 自然的右的,向右的记录符号为Nat6 Relax 放松,松弛7 Music 音乐8 Tempo 速度9 Rhythm 节奏10 Figure 舞步,步法11 Variation 变奏,变化步法12 Alignment(缩写Align) 步向,方位13 Amount of Turn 旋转度14 Precede 在…..之前15 Body Sway 身体倾斜简称B.S16 Swing 摆动动作摆荡17 Rise and Fall 升降动作18 Lower 低下,降低,放下19 Balance 平衡20 Step in Timing 脚步的时间每步占用的拍子21 Reverse 反转的,反的左的,向左的记录符号为Rev22 Position 位置,位子舞伴相关位置,记录符号为Pos23 Posture,Poise 舞姿,姿势24 Hold,Holding 握抱,握持25 Lead,Leading 引导,领导26 Follow,Following 跟随27 Step 步子,舞步28 Closed 关闭,闭式29 Open 开放的,开式30 Crossed 交叉的31 Closed Position 闭位式,闭式舞姿32 Facing Position 舞伴相对立位面对位33 Open Position 开式位,开式舞姿34 Promenade Position 散式舞姿,侧行位简称P.P35 Counter Promenade Position 反散式舞姿,反侧行位简称C.P.P36 Outside Partner 外侧舞姿,右外侧位记录符号为O.P37 Partner Outside 舞伴进外侧,退外侧步38 Wrong Side 左外侧位39 Line of Dancing 物程线,舞蹈线简称L.O.D40 Wall 墙,壁记录符号为W41 Centre 中央,中心记录符号为C42 Diagonal(ly) 斜向的43 Side 边,旁,侧44 Left 左记录符号为L45 Right 右记录符号为R46 Forward 向前的记录符号为Fwd47 Backward 向后的记录符号为Bwd48 Outside 外侧,边外的记录符号为O/S49 Inside 内侧,边内的50 In Line 对直线51 Partner in Line 正对舞伴52 To 衔接,向……53 With 带,带有54 Weight 重量,中心记录符号为Wt55 Without Weight 无重心,无重量记录符号为W/Owt 6 Weight Change 重心转移57 Diagonally Wall 斜向墙记录符号为DW58 Diagonally Centre 斜向中央记录符号为DC59 Syncopation,Syncopated 切分,切分的60 Progressive 行进的记录符号为Prog61 Foot 脚,足记录符号为F62 Foot Work 足着点,足部动作记录符号为Fwk63 Foot Change 换脚动作64 Toe 脚趾,脚尖记录符号为T65 Ball of Foot 脚掌记录符号为B66 Hell 脚跟记录符号为H67 Inside Edge 内侧缘记录符号为IE68 Ankle 脚踝69 Leg 腿70 Knee 膝71 Hip 臀,胯72 Waist 腰73 Breast 胸74 Shoulder 肩75 Shoulder Lesding 肩引导与动力脚同侧肩先行76 Arm 臂77 Elbow 肘78 Hand 手79 Finger 指80 Head 头81 Face 面,脸82 Technique 技术,技巧83 Contrary Body Movement 反身动作简称C.B.M.P84 Contrary Body Movement Position 反身动作位置简称C.B.M.P(6)标准舞专用术语标准舞种通用动作1 Basic Movement 基本动作2 Walk 走步,常步3 Turn 转4 Whole Turn 全转 360o角转5 Half Turn 二分之一转,半转 180o角转6 Quarter Turn 四分之一转 90o角转7 Natural Turn 右转顺转8 Reverse Turn 左转反转9 Pivot Turn 轴转撇转10 Natural Pivot Turn 右轴转右撇转11 Reverse Pivot Turn 左轴转左撇转12 Slip Pivot 滑轴转滑撇转13 Spin 疾转,旋转14 Natural Spin Turn 右旋转右疾转15 Reverse Spin Turn 左旋转左疾转16 Impetus Turn 推转顺转17 Open Impertus Turn 开式推转开式顺转,开足疾转18 Double Reverse Spin 双左疾转旋涡转19 Natural Impetus Turn 右推转右向顺转,合足疾转20 Whisk 扫步,叉行步21 Chassee(法) 并合步,追步快滑步22 Check 截步,止步23 Check Back 截步退行止步后行24 Back Check 退截步退止步25 Brush 刷步26 Break 断步27 Lock Step 锁步28 Forward Lock Step 前进锁步29 Backward Lock Step 后退锁步30 Rock 摇步,摇摆31 Wing 翼步32 Weave 纺织步迂回步33 Weave form P.P. 从P。

备战2022年中考英语题阅读专项训练专题02 2022年北京冬奥会(解析版)¤话题01 为2022年北京冬奥会招募志愿者¤话题02 介绍三届冬奥会情况¤话题03 为庆祝历届冬奥会发行的邮票¤话题04 北京冬奥会及残奥会的吉祥物¤话题05 冬奥会期间住宿预订¤话题06为冬奥会而建造的高铁的情况¤话题07 北京冬奥会的比赛项目¤话题08 冬奥会运动项目之一——冰球¤话题09 冬奥会的发展历史¤话题10 易小阳刻苦训练,为冬奥会作准备的故事Passage 1(2021·江苏·南京郑和外国语学校一模)V olunteers wanted around the world! This is your chance to have a special role in Beijing 2022. The website below can offer more information on the application details. See you in Beijing 2022●Be at least 18 years of age by January 2022.●Be able to municate in Chinese or English freely.●Be able to take part in preGames training and offer volunteer services during the Games period.Applications will be accepted from 5 December 2019 to 30 June 2021. V olunteers who are chosen will receive official notice by 30 September 2021.1.For more information on the application details, you can click on ________.A.309 likes B.152 OpinionC.D.share2.People who want to volunteer can send applications in ________.A.June 2021B.September 2021C.December 2022D.January 2022 3.A volunteer should ________.A.only e from China B.receive preGames trainingC.be above 18 by January 2021D.speak English and Chinese【答案】1.C 2.A 3.B【解析】文章是介绍2022年北京冬奥会招募志愿者的对象、要求、报名时间等。

小学上册英语第二单元真题(含答案)考试时间:90分钟(总分:110)A卷一、综合题(共计100题共100分)1. 听力题:A reaction that releases energy is called an ______ reaction.2. 听力题:My brother is very ________.3. 听力题:The phase change from solid to liquid is called ______.4. 选择题:Which animal is known as the king of the jungle?A. LionB. TigerC. ElephantD. Bear5. 听力题:In a chemical equation, the substances that react are called ______.6. 选择题:What do we call the area around the equator?A. TropicsB. PolesC. ZonesD. Continents答案:A7. 选择题:What do we call the scientific study of plants?A. BotanyB. ZoologyC. EcologyD. Geography答案: A8. 填空题:I find ________ (社会学) very interesting.9. 选择题:What is the name of the small, winged insect that produces honey?A. AntB. FlyC. BeeD. Wasp答案:C10. 听力题:The baby is ________ in the crib.11. 选择题:What is 50 ÷ 10?A. 4B. 5C. 6D. 7答案:B12. 填空题:He is a _____ (评论员) on a popular podcast.13. 听力题:The ______ teaches us about international relations.14. 填空题:The coach, ______ (教练), encourages us to do our best.15. 选择题:What is the name of the fictional superhero from Gotham City?A. SupermanB. SpidermanC. BatmanD. Ironman16. 听力题:A ______ is a type of animal that has a pouch.Many plants have adapted to survive in ______ climates. (许多植物已适应在极端气候中生存。

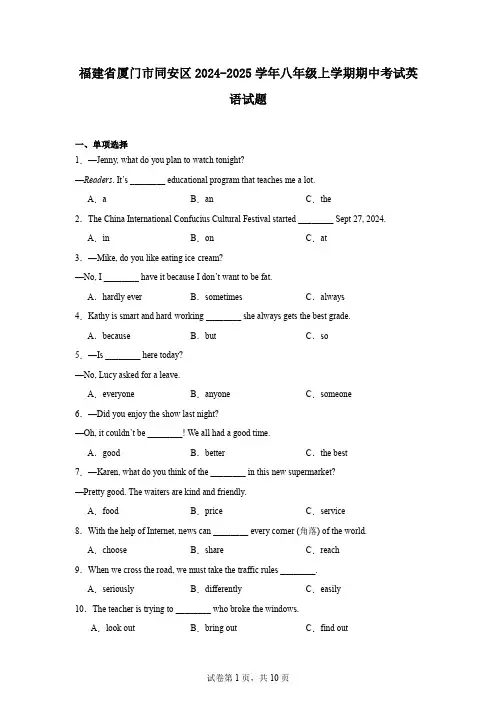

福建省厦门市同安区2024-2025学年八年级上学期期中考试英语试题一、单项选择1.—Jenny, what do you plan to watch tonight?—Readers. It’s ________ educational program that teaches me a lot.A.a B.an C.the2.The China International Confucius Cultural Festival started ________ Sept 27, 2024.A.in B.on C.at3.—Mike, do you like eating ice-cream?—No, I ________ have it because I don’t want to be fat.A.hardly ever B.sometimes C.always4.Kathy is smart and hard-working ________ she always gets the best grade.A.because B.but C.so5.—Is ________ here today?—No, Lucy asked for a leave.A.everyone B.anyone C.someone6.—Did you enjoy the show last night?—Oh, it couldn’t be ________! We all had a good time.A.good B.better C.the best7.—Karen, what do you think of the ________ in this new supermarket?—Pretty good. The waiters are kind and friendly.A.food B.price C.service8.With the help of Internet, news can ________ every corner (角落) of the world.A.choose B.share C.reach9.When we cross the road, we must take the traffic rules ________.A.seriously B.differently C.easily10.The teacher is trying to ________ who broke the windows.A.look out B.bring out C.find out11.Linda is crying, but no one knows what ________ to her just now.A.happens B.happened C.is happening12.—What do you want for dinner, noodles or dumplings?—________. I like both of them.A.It’s up to you B.Help yourself C.That’s all right二、完形填空“Any volunteers?” Mr White asked, looking around. Every time the teacher asked such question, I was afraid of putting up my hand. I just lowered my head and said nothing.In fact, how I wished to raise my hand to show 13 in front of others! But whenever I tried to be brave (勇敢的), there would always be a voice in my mind, “Would they laugh at me if I didn’t give the 14 answer?”But my mother always 15 me to be brave. “No one cares if it’s right or not. When you raise your hand and give your answers, you are the brave one,” said my mom. Since I wanted to share my opinions, I 16 make a change.The big day came a few days later.The moment the teacher asked a question, I raised my hand 17 because I wanted to be the first one to answer it. I tried to express myself as clearly as I could, 18 my heart was pounding (砰砰地跳) fast. To my surprise, everyone clapped loudly for me instead of laughing at me.I finally realized that life is full of choices and you don’t know what 19 they may bring to you. But if you never 20 and make a decision, your life will never have changes. So don’t let fear stop you: be brave.13.A.myself B.yourself C.themselves 14.A.creative B.simple C.right15.A.invited B.expected C.chose16.A.decided to B.forgot to C.stopped to 17.A.quickly B.slowly C.carefully18.A.so B.though C.if19.A.report B.reason C.result20.A.laugh B.wait C.try三、阅读理解China has a long history that goes back more than 5,000 years. And it is full of cool places with amazing culture. Here are three of them.21.People found the Sanxingdui Ruins in ________.A.1700B.1929C.1986D.202322.How many parts are there in the the Grand Canal?A.Two.B.Three.C.Four.D.Five.23.Where can we see the great Buddhist statues from Tang Dynasty?A.Guanghan.B.Beijing.C.Hangzhou.D.Luoyang.24.In which section of the newspaper can we read this passage?A.Art.B.Nature.C.Culture.D.Geography.In Ms. Rose’s classroom, every student had a special talent. Tom was the fastest at math, Zoe drew the most colorful pictures, and Max always had the funniest jokes. But Mia, a quiet girl in the back row, wasn’t sure what her best skill was.One day, Ms. Rose asked everyone to share their “super skill”. Tom worked out a math problem faster than anyone. Zoe showed her excellent artwork, and Max made everyone laugh with a funny joke. Mia started to feel worried. She wasn’t the fastest, funniest, or most colorful.Then Ms. Rose asked, “Mia, what do you think is your super skill?” Mia looked down, unsure. Just then, Tom raised his hand. “Mia helped me yesterday when I was having trouble on an English problem.” he said, “She explained (解释) it slower and clearer than anyone else, and I finally understood!”“When my crayons fell all over the floor. Mia helped me pick them up. No one else noticed, but she did.” Zoe added, “When I felt sad about my artwork, Mia noticed and told me it looked amazing. She even helped me make it better. It made me feel proud (自豪的) of my work again.”Max agreed and said, “When I forgot my snack, Mia shared hers with me. That was the nicest thing anyone did all day!”Ms. Rose smiled. “Mia, you may not be the fastest, but you have the biggest heart. That’s a super skill too!” The class clapped, and Mia felt proud. She realized that her kindness was just as valuable as her friends’ skills and that it was a special talent of her own.25.How did Mia help Tom with his problem?A.B.C.D.26.What does the underlined word “valuable” mean?A.funny B.simple C.useful D.common 27.What does “super skill” mean in the story?A.Something that only Ms. Rose can do.B.A difficult math problem to work out.C.The best talent for making people laugh.D.A talent that makes each student special. 28.What’s the best title of this passage?A.The Best Artwork B.The Kindness of Mia C.The Funniest KidD.Ms Rose’s Special DayDid you know that cats can play fetch (取物), just like dogs? Many people think that only dogs like this game, but some cats do as well!A team from Purdue University studied this interesting behavior (行为). They asked more than 8,000 cat owners (主人) if their cats would bring back a toy after it was thrown. Then the team used this information to learn which cats are more likely to play fetch. This helped them learn more about different cats and what makes them fetch.The study found that about 41% of cats do play fetch, compared to (与……对比) 78% of dogs. This shows that cats also enjoy this playful activity. Some types of cats, like Siamese and Burmeso, are more likely to fetch. Younger and healthier cats like playing fetch more often. The study also found that cats living indoors also play fetch more, maybe because they do not have as many chances to hunt (捕猎) outside. Fetch helps them practice hunting actions, like running and jumping.Cats can be just as friendly and playful as dogs. Sometimes, they even bring a toy to their owner to start the game. This shows that cats want to play and be close to their owners. Playing fetch is a way for cats to have fun and get exercise, which helps them stay healthy and happy.This study is important because it shows us a new side of cats. Cats are often seen as quiet, but playing fetch shows that they can be active and enjoy spending time with their families. Knowing this can help cat owners give their cats more chances to play, stay healthy, and feel loved.29.How did the team learn about cats playing fetch?A.By watching cats quietly.B.By making videos of cats.C.By giving cats toys to fetch.D.By asking cat owners questions.30.Why are indoor cats more likely to play fetch?A.They are often bored.B.They don’t like other toys.C.They enjoy doing exercise.D.They hunt outside less often.31.Why does the cat bring a toy to its owner.A.To show love B.To play a game.C.To catch a mouse.D.To feel like a dog. 32.How can this study help cat owners in the future?A.Care for cats better.B.Play fetch nicely C.Make cats quieter.D.Stay in good health.四、任务型阅读阅读短文,完成表格内容,每空不超过三个词。

高考英语语法填空热点话题押题预测专题10夏季冬季奥运会吉祥物会徽理念20篇(原卷版)养成良好的答题习惯,是决定高考英语成败的决定性因素之一。

做题前,要认真阅读题目要求、题干和选项,并对答案内容作出合理预测;答题时,切忌跟着感觉走,最好按照题目序号来做,不会的或存在疑问的,要做好标记,要善于发现,找到题目的题眼所在,规范答题,书写工整;答题完毕时,要认真检查,查漏补缺,纠正错误。

总之,在最后的复习阶段,学生们不要加大练习量。

在这个时候,学生要尽快找到适合自己的答题方式,最重要的是以平常心去面对考试。

英语最后的复习要树立信心,考试的时候遇到难题要想“别人也难”,遇到容易的则要想“细心审题”。

越到最后,考生越要回归基础,单词最好再梳理一遍,这样有利于提高阅读理解的效率。

另附高考复习方法和考前30天冲刺复习方法。

(2024巴黎奥运会会徽+吉祥物+2022北京冬奥会绿色理念+吉祥物冰墩墩+饮食+2020东京奥运会冠军杨倩+奥运五环)(2022秋·宁夏银川·高三校考)阅读下面材料,在空白处填入1个适当的单词或括号内单词的正确形式。

With just over 600 day 1 (go) until the opening of the next Olympic and Paralympic Games, 2 official mascots of Paris 2024 have been revealed.Now it’s time to meet the Phryges, the mascots for the Paris 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games, who have been tasked with an important mission: to show the world that sport can change everything and3 it deserves to play a major role in society. Kain Phryges (pronounced fri-jeeuhs) are small Phrygian caps,4 represent a strong symbol of liberty, and the ability of people5 (undertake) great and meaningful responsibilities.The Olympic Phryge is triangular in shape, and comes with friendly smile, blue eyes and big colored sneakers, the golden Paris 2024 logo 6 their chests, which is bound to gain high 7 (popular). The Paralympic version 8 (feature) a prosthetic leg (假肢) that goes to the knee. Ever since Shuss, a red, white and blue mascot on skis, appeared at the Olympic Grenoble 1968, mascots have been fun and 9 (festival) ambass adors of the Olympic Movement. “The mascots have always occupied a special place in the history of the Olympic and Paralympic Games,” said Paris 2024 president Tony Estanguet. “They form the emotional bond between the Games and the people, 10 (contribute) to the atmosphere and high spiritin the stadiums.”Organizers said they want to deliver the idea that sport can change everything and that it deserves to have a leading place in the society through the mascots.(2023秋·云南大理·高三统考)阅读下面材料,在空白处填入适当的内容(1个单词)或括号内单词的正确形式。

中国与国际体育的英文作文China and international sports have a complex relationship. On one hand, China has made significant strides in the world of sports, becoming a force to be reckoned with in various disciplines. Chinese athletes have achieved remarkable success in events such as gymnastics, diving, and table tennis, bringing glory to their country. This has not only boosted national pride but has also helped to elevate China's status on the global stage.However, there have been controversies surrounding China's involvement in international sports. The country has faced accusations of doping and unfair practices, tarnishing its reputation. These incidents have raised questions about the integrity of China's sports system and its commitment to fair play. It is essential for China to address these concerns and take steps to ensure transparency and accountability in its sporting endeavors.Despite these challenges, China has been activelyengaged in hosting international sports events. The country has successfully organized major competitions such as the Olympic Games and the Asian Games, showcasing its abilityto provide world-class facilities and infrastructure. These events have not only promoted tourism and economic development but have also fostered cultural exchange and understanding between China and the international community.China's involvement in international sports has alsohad a significant impact on its society. The success of Chinese athletes has inspired a new generation of sports enthusiasts and encouraged more young people to participate in physical activities. This has led to a growing sports industry in China, with increased investments in sports facilities, training programs, and professional leagues.The government has recognized the importance of sports in promoting health and well-being and has made efforts to encourage sports participation at all levels.In conclusion, China's relationship with international sports is a complex one, characterized by both achievements and challenges. While Chinese athletes have excelled on theglobal stage, there have been concerns about fairness and transparency. Nevertheless, China's involvement in international sports has brought numerous benefits, including national pride, economic development, and increased sports participation. It is crucial for China to address the issues raised and continue to strive for excellence in the world of sports.。

2021届怀柔区体育运动学校高三英语上学期期末考试试题及答案第一部分阅读(共两节,满分40分)第一节(共15小题;每小题2分,满分30分)阅读下列短文,从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中选出最佳选项ALocated in the beautiful Sichuan Basin, Chongqing is a magical 8D city. The natural history and cultural scenery of the area provide children with learning opportunities because they can enjoy the many wonders of this area.Fengjie Tiankeng Ground JointTiankeng Diqiao Scenic Area is located in the southern mountainous area of Fengjie County. The Tiankeng pit is 666 meters deep and is currently the deepest tiankeng in the world. The scenic spot is divided into ten areas including Xiaozhai Tiankeng, Tianjingxia Ground, Labyrinth River, and Longqiao River. There are many and weird karst cave shafts, and countless legends haunt them.Youyang Peach GardenYouyang Taohuayuan Scenic Area is a national forest park, a national 5A-level scenic spot, and a national outdoor sports training base. Located in the hinterland of Wuling Mountain. The Fuxi Cave in the scenic spot is about 3,000 meters long, with winding corridors, deep underground rivers, and color1 ful stalactites. The landscape is beautiful.Jinyun Mountain National Nature ReserveJinyun Mountain is located in Beibei District of Chongqing City, about 45 kilometers away from the Central District of Chongqing City. The nine peaks of Jinyun Mountain stand upright and rise from the ground. The ancient trees on the mountain are towering, the green bamboos form the forest, the environment is quiet, and the scenery is beautiful, so it is called "Little Emei". Among them, Yujian Peak is the highest, 1050 meters above sea level; Lion Peak is the most precipitous and spectacular, and the other peaks are also unique.Chongqing People's SquareChongqing's Great Hall of the People, one of the landmarks of Chongqing, gives people the deepest impression than its magnificent appearance resembling the Temple of Heaven. It also uses the traditional method of central axis symmetry, with colonnade-style double wings and a tower ending, plus a large green glazed roof, large red pillars, white railings, double-eave bucket arches, and painted carved beams.1.How deep is the Tiankeng Ground Joint?A.666mB.3,000mC.45kmD.1050m2.Which of the following rocks can you see in Youyang Peach Garden?A.LimestoneB.StalactiteC.MarbleD.Quartzite3.Which attraction is closest to downtown Chongqing?A.Fengjie Tiankeng Ground JointB.Jinyun Mountain National Nature ReserveC.Chongqing People's SquareD.Youyang Peach GardenBPigeons inLondonhave a bad reputation. Some people call them flying rats. And many blame them for causing pollution with their droppings. But now the birds are being used to fight another kind of pollution in this city of 8.5 million.“The problem for air pollution is that it’s been largely ignored as an issue for a long time,” says Andrea Lee, who works for the London-based environmental organization Client Earth. “People don’t realize how bad it is, and how it actually affects their health.”London’s poor air quality is linked to nearly 10,000 early deaths a year. Lee says, citing(引用)a report released by the city manager last year. If people were better informed about the pollution they’ re breathing, she says, they could pressure the government to do something about it.Nearby, on a windy hill inLondon’s Regent’s Park, an experiment is underway that could help—the first week of flights by the Pigeon Air Patrol. It all began when Pierre Duquesnoy, the director for DigitasLBi, a marketing firm, won a London Design Festival contest last year to show how a world problem could be solved using Twitter. Duquesnoy, fromFrance, chose the problem of air pollution.“Basically, I realized how important the problem was,” he says. “But also I realized that most of the people around me didn’t know anything about it.” Duquesnoy says he wants to better measure pollution, while at the same time making the results accessible to the public through Twitter.“So”, he wondered, “how could we go across the city quickly collecting as much data as possible?” Drones were his first thought. But it’s illegal to fly them overLondon. “But pigeons can fly aboveLondon, right?” he says. “They live—actually, they are Londoners as well. So, yeah, I thought about using pigeons equipped with mobile apps. And we can use not just street pigeons, but racing pigeons, because they fly pretty quickly and pretty low.”So it might be time for Londoners to have more respect for their pigeons. The birds may just be helping to improve the quality of the city’s air.4. What can we infer aboutLondon’s air quality from Paragraph 2?A. Londoners are very satisfied with it.B. The government is trying to improve it.C Londoners should pay more attention to it.D. The government has done a lot to improve it.5. Duquesnoy attended the London Design Festival to _________.A. entertain Londoners.B. solve a world problem.C. design a product for sale.D. protect animals like pigeons.6. Why did Duquesnoy give up using drones to fly acrossLondon?A. Because they are too expensive.B. Because they fly too quickly.C. Because they are forbidden.D. Because they fly too high.7. Which can be the best title for the text?A. Clean air inLondon.B. London’s dirty secret.C. London’s new pollution fighter.D. Causes of air pollution inLondon.CWhat do you think of 80s pop music? Do the names George Michael, Madonna and Michael Jackson sound familiar? Well, these are just some of the names that were well-known in the music scene of the 80s and early 90s. The 80s pop musicscene was an important step to the popularity (普及) of present-day music. A new wave in the music scene was introduced, which made such music styles as punk rock, rap music and the MTV popular. Although it was an end to the old 60s and 70s styles, it was also the beginning of something big. The popularity of music videos meant that artists now replaced their guitar-based music with visual displays. A new wave of artists came on the scene and the entire industry developed quickly.The most famous 80s pop music video is Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Introduced in 1982, few people can forget the video not only because of its never-be-foreseen images, but also because of the popularity it received. Think of how 80s pop music changed the lives of people who grew up in the 80s. Ask a young man today to tell you the names of the “New Kids on the Block” and he will start talking about the neighbor kids who just moved in. These are not the answers you might have heard in the 80s. Though today’s young men do not recognize how cool 80s pop music was, most people will always remember it for what it was and these are happy memories they will always love.Some of the 80s pop music legends (传奇人物) include Madonna, U2, AeroSmith and of course the King ofPop Michael Jackson. Let’s not forget Prince, Tina Turner, Phil Collins and Motown’s Lionel Ritchie. Some of these musicians played music that has stood the test of time. Undoubtedly, the 80s pop music scene will live on for many more years to come.8. What is the text mainly about?A. The characters of 80s pop music.B. What made 80s pop music popular.C. 80s pop music’s steps to popularity.D. The effects of 80s pop music.9. 80s pop music mainly includes the following styles EXCEPT ________.A. guitar-based musicB. the MTVC. rap musicD. punk rock10. Michael Jackson’s Thriller impressed people so deeply mainly because ________.A. it changed the lives of peopleB. he sang it in a special styleC. it was made into a music videoD. it left people with happy memories11. The purpose of the last paragraph is to tell readers that ________.A. 80s pop music is and will remain popularB. 80s pop music has many faultsC. 80s pop music is now out of dateD. we shouldn’t forget the great musicians of the 80sDYou've probably heard it suggested that you need to move more throughout the day, and as a general rule of thumb, that "more" is often defined as around 10,000 steps. With many Americans tracking their stepsvia new fitness-tracking wearables, or even just by carrying their phone, more and more people use the 10,000-step rule as their marker for healthy living. Dr. Dreg Hager, professor of computer science at Johns Hopkins, decided to take a closer look at that 10,000-step rule, and he found that usingitas a standard may be doing more harm than good for many.“It turns out that in 1960 in Japan they figured out that the average Japanese man, when he walked 10,000 steps a day burned something like 3,000 calories and that is what they thought the average person should consume so they picked 10,000 steps as a number” Hager said.According to Hager, asking everyone to shoot for 10,000 steps each day could be harmful to the elderly or those with medical conditions, making it unwise for them to jump into that level of exercise, even if it's walking. The bottom line is that 10,000 steps may be too many for some and too few for others. He also noted that those with shorter legs have an easier time hitting the 10,000-step goal because they have to take more steps than people with longer legs to cover the distance. It seems that 10,000 steps may be suitable for the latter.A more recent study focused on older women and how many steps can help maintain good health andpromote longevity (长寿).The study included nearly 17,000 women with an average age of 72. Researchers found that women who took 4,400 steps per day were about 40% less likely to die during a follow-up period of just over four years: Interestingly, women in the study who walked more than 7,500 steps each day got no extra boost in longevity.12. What does the underlined word "it' in Paragraph 1 refer to?A. The phone recording.B. The 10,000-step rule.C. The healthy living.D. The fitness-tracking method.13. What does Paragraph 2 mainly talk about?A. How many steps a Japanese walks.B. How we calculate the number of steps.C. If burning 3,000 calories daily is scientific.D. Where 10,000 steps a day came from.14. Who will probably benefit from 10,000 steps each day according toHager?A. Senior citizens.B. Young short-legged people.C. Healthy long-legged peopleD. Weak individuals.15. How many steps may the researchers suggest senior citizens take each day?A. 4,400 steps.B. 10,000 steps.C. 2,700 steps.D. 7,500 steps.第二节(共5小题;每小题2分,满分10分)阅读下面短文,从短文后的选项中选出可以填入空白处的最佳选项。

奥运英语知识Olympic Knowledge Q & A1、Who created the Olympic Games?谁创立了奥运会?The ancient Greeks.古希腊人。

2、What was one of the prizes for winning an Olympic competition?赢得奥运竞赛将获得一样什么奖品?A wreath.。

花冠.3、What would happen to a married woman who tried to participate the ancient-Olympic Games? 已婚妇女试图参加古代奥运会将会发生什么结果?She could be thrown off a cliff.她将被扔下悬崖。

4、What did male athletes wear during ancient Olympic competition?古代奥运竞赛男运动员穿什么?Nothing.裸体.5、When the first Olympic Games held?第一届奥运会是什么时候举办的?In 776 BC.公元前776年.6、Which rule did the ancient Greeks strictly adhere to?古希腊人严格坚持什么规则?Barring women from competing and halting wars during the Games.禁止妇女比赛及奥运会期间停止战争.7、How many centuries are the ancient Olympic Games known to have existed for?古代奥运会持续了多少个世纪?12centuries.12世纪.8、When were the ancient Olympic Games abolished?古代奥运会何时废除?393AD.公元393年.9、hat inspired the idea for the Modern Olympic Games?什么激发了现代奥运会的想法?The discovery of the ruins at Olympia.奥林匹亚废墟的发现.10、Where is the origin of the Modern Olympic Games?现代奥运会的发袢地在何处?Olympia,Greece.希腊奥林匹亚.11、Who is the creator of the Modern Olympic Games?现代奥运会的创始人是谁?The French educator Baron Pierre de Coubertin.现代奥运会的创始人是顾拜旦,12、Who is the father of the Modern Olympic Games?谁被称为“奥运会之父”?Baron Pierre de Coubertin.法国人顾拜旦.13、When was the International Olympic Committee founded?国际奥委会是何时诞生的?The International Olympic Committee was founded on June 23 1894.国际奥委会诞生于1894年6月23日。

英语吉祥物小短文In English culture, mascots play an important role in representing various organizations, teams, or events. They bring luck and represent the identity of the group they belong to. In this article, we will explore some popular English mascots.One of the most well-known English mascots is the lion. The lion is often associated with strength, bravery, and power. It is also the national animal of England and symbolizes the country's pride and heritage. In many sporting events, the English teams are often represented by a lion mascot, encouraging their players and captivating the audience with their fierce presence.Another popular English mascot is the bulldog. The bulldog is a symbol of tenacity, determination, and loyalty. It is often associated with the British spirit and has become a representation of England itself. Bulldog mascots can be found at various events, from sports matches to national celebrations, instilling a sense of unity and pride among the English people.A unique mascot that gained popularity in recent years is the Paddington Bear. Originally a character from a beloved children's book series, the Paddington Bear has become an unofficial mascot of London. This friendly and adventurous bear is often seen wearing his signature blue coat and red hat, adding a touch of charm and whimsy to the city. The Paddington Bear brings joy to both locals and tourists, embodying the playful and welcoming spirit of London.In addition to animals and fictional characters, historic figures are also chosen as mascots. For example, Winston Churchill, the former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom,is sometimes portrayed as a mascot. With his iconic cigar and determined expression, Churchill symbolizes resilience, leadership, and British history. His presence as a mascot serves as a reminder of the values that the English people hold dear.Mascots hold a special place in English culture. They not only represent a particular group but also embody the characteristics and ideals that are valued by the English people. From lions to bulldogs and even fictional characters like Paddington Bear, these mascots contribute to the sense of identity, unity, and pride in England. Whether on the sports field or at national events, they bring luck, inspire courage, and add a touch of excitement to the atmosphere.。