Lyons_Reimer_Twillingate capacity paper _8June2006_

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:74.69 KB

- 文档页数:24

小学上册英语第3单元期末试卷考试时间:100分钟(总分:100)B卷一、综合题(共计100题共100分)1. 填空题:The ________ was a famous historical figure known for his peace efforts.2. 选择题:What is the opposite of 'tight'?A. LooseB. FirmC. SecureD. Strong答案:A3. 听力题:I put my _____ (衣服) in the closet.4. 填空题:The _______ (The Great Famine) devastated Ireland in the 19th century.5. 选择题:What is the capital city of New Zealand?A. WellingtonB. AucklandC. ChristchurchD. Dunedin答案: A6. 选择题:What do we call a place where you can buy books?A. LibraryB. BookstoreC. SchoolD. Grocery storeI like to draw pictures of my ________ (玩具名) and imagine their adventures.8. 听力题:Some planets have _____ made of gas and clouds.9. 填空题:The _______ (The Civil Rights Act) aimed to dismantle segregation laws.10. 填空题:Certain plants are known for their ability to improve ______ health in the environment. (某些植物因其改善环境健康的能力而闻名。

高中英语学术论文研究方法练习题40题1.Which of the following topics is most suitable for a high school English academic paper?A.The history of video games.B.The influence of social media on teenagers' language learning.C.The development of artificial intelligence in the medical field.D.The architecture of ancient Rome.答案:B。

解析:选项 A 视频游戏历史与高中英语学术论文关联不大。

选项C 人工智能在医疗领域的发展与英语学科不相关。

选项D 古罗马建筑也与英语学科没有直接关系。

而选项B 社交媒体对青少年语言学习的影响既与英语语言相关,也适合高中学生进行研究。

2.In choosing a topic for an English academic paper, what should be considered first?A.Personal interest.B.Availability of resources.C.Relevance to the curriculum.D.Popularity of the topic.答案:C。

解析:选项 A 个人兴趣虽然重要,但不是首先要考虑的。

选项 B 资源的可获得性在确定选题后再考虑。

选项 D 话题的流行度不是关键因素。

首先应考虑与课程的相关性,这样才能确保论文在学科范围内有意义。

3.Which of the following is NOT a good criterion for choosing anacademic paper topic?A.Being too broad.B.Having enough research materials available.C.Being relevant to current events.D.Being easy to research.答案:A。

福建省厦门第一中学2023-2024学年高三上学期11月期中英语试题学校:___________姓名:___________班级:___________考号:___________一、阅读理解FIVE UNUSUAL SPORTSWhat sports are you into? Football? Tennis? Swimming? If you’re looking for a change, you might like to try one of these.OctopushOctopush (or underwater hockey as it’s also known) is a form of hockey that’s played in a swimming pool. Participants wear a mask and snorkel and try to move a puck (水球) across the bottom of a pool. The sport has become popular in countries such as the UK, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. An ability to hold your breath for long periods of time is a definite plus.ZoobombingZoobombing involves riding a children’s bike down a steep hill. The sport originated in the US city of Portland in Oregon in 2002. Participants carry their bikes on the MAX Light Rail and go to the Washington Park station next to Oregon Zoo (which is why it’s called “zoobombing”). From there, they take a lift to the surface, and then ride the mini-bikes down the hills in the area.Office Chair RacingOffice Chair Racing consists of racing down a hill in office chairs that can reach speeds of up to 30kph. Strict rules are in place for competitors: they’re allowed to fit in-line skate wheels and handles to their chairs, but no motors. “We check each chair carefully in advance,”one of the organizers explained. The participants race in pairs wearing protective padding as they launch themselves from a ramp (坡道). Prizes are given to the fastest competitors and also for the best-designed chairs.Fit 4 DrumsFit 4 Drums is a new form of cardio-rhythmic exercise. Led by an instructor, the class involves beating a specially-designed drum with two sticks while dancing at the same time. It’s the first group fitness activity where you get to play a drum while getting an intense workout. A sense of rhythm is a definite advantage!Horse BoardingHorse Boarding involves being towed behind a horse at 35mph on an off-road skateboard. Professional stuntman Daniel Fowler Prime invented the sport after he strung a rope between his off-road “mountain board” and a horse. Participants stand on a board while holding onto a rope, attempting to maintain their balance as the horse gallops (疾驰) ahead. “The horse rider and the horse have to work together because if they don’t, the horse goes flying,”Daniel explained.So, which sport would you like to try?1.What do you need to do if you want to play Octopush?A.Swim on the surface of the water.B.Hold your breath before the sport.C.Play it by the side of the seashore.D.Wear underwater breathing devices. 2.Which activity will you choose if you want to take part in collective fitness?A.Zoobombing B.Office Chair RacingC.Fit 4 Drums D.Horse Boarding3.What proverb does Horse Boarding tell us?A.The spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak.B.Never let your feet run faster than your shoes.C.The bigger they come, the harder they fall.D.Every chess master was once a beginner.Eliana Yi dreamed of pursuing piano performance in college, never mind that her fingers could barely reach the length of an octave (八度音阶). Unable to fully play many works by Romantic-era composers, including Beethoven and Brahms, she tried anyway — and in her determination to spend hours practicing one of Chopin’s compositions which is known for being “stretchy”, wound up injuring herself.“I would just go to pieces,” the Southern Methodist University junior recalled. “There were just too many octaves. I wondered whether I was just going to play Bach and Mozart for the rest of my life.”The efforts of SMU keyboard studies chair Carol Leone are changing all that. Twenty years ago, the school became the first major university in the U.S. to incorporate smaller keyboards into its music program, leveling the playing field for Yi and other piano majors.Yi reflected on the first time she tried one of the smaller keyboards: “I remember beingreally excited because my hands could actually reach and play all the right notes,” she said. Ever since, “I haven’t had a single injury, and I can practice as long as I want.”For decades, few questioned the size of the conventional piano. If someone’s hand span was less than 8.5 inches — the distance considered ideal to comfortably play an octave — well, that’s just how it was.Those who attempt “stretchy” passages either get used to omitting notes or risk tendon (腱) injury with repeated play. Leone is familiar with such challenges. Born into a family of jazz musicians, she instead favored classical music and pursued piano despite her small hand span and earned a doctorate in musical arts.A few years after joining SMU’s music faculty in 1996, the decorated pianist read an article in Piano and Keyboard magazine about the smaller keyboards. As Leone would later write, the discovery would completely renew her life and career.In 2000, she received a grant to retrofit a department Steinway to accommodate a smaller keyboard, and the benefits were immediate. In addition to relieving injury caused by overextended fingers, she said, it gave those with smaller spans the ability to play classic compositions taken for granted by larger-handed counterparts.Smaller keyboards instill many with new confidence. It’s not their own limitations that have held them back, they realize; it’s the limitations of the instruments themselves. For those devoted to a life of making music, it’s as if a cloud has suddenly lifted.4.What is the similarity between Eliana Yi and Carol Leone?A.Their interest in jazz extended to classical music.B.Short hand span used to restrict their music career.C.They both joined SMU’s music faculty years ago.D.Romantic-era composers’ music was easy for them.5.Why did SMU initiate an effort to scale down the piano?A.To reduce the number of octaves.B.To incorporate Bach into its music program.C.To provide fair opportunities for piano majors.D.To encourage pianists to spend more hours practicing.6.How did Yi probably feel when she played the retrofitted piano?A.Confident.B.Frustrated.C.Challenging.D.Determined. 7.Which of the following is the best title of the passage?A.Who Qualifies as an Ideal Pianist?B.Traditional or Innovative Piano?C.Hard-working Pianists Pays offD.The Story behind Retrofitted PianosThe curb cut (路缘坡). It’s a convenience that most of us rarely, if ever, notice. Yet, without it, daily life might be a lot harder—in more ways than one. Pushing a baby stroller onto the curb, skateboarding onto a sidewalk or taking a full grocery cart from the sidewalk to your car—all these tasks are easier because of the curb cut.But it was created with a different purpose in mind.It’s hard to imagine today, but back in the 1970s, most sidewalks in the United States ended with a sharp drop-off. That was a big deal for people in wheelchairs because there were no ramps to help them move along city blocks without assistance. According to one disability rights leader, a six-inch curb “might as well have been Mount Everest”. So, activists from Berkeley, California, who also needed wheelchairs, organized a campaign to create tiny ramps at intersections to help people dependent on wheels move up and down curbs independently.I think about the “curb cut effect” a lot when working on issues around health equity (公平). The first time I even heard about the curb cut was in a 2017 Stanford Social Innovation Review piece by Policy Link CEO Angela Blackwell. Blackwell rightly noted that many people see equity as “a zero-sum game (零和游戏)” and that it is commonly believed that there is a “prejudiced societal suspicion that intentionally supporting one group hurts another.” What the curb cut effect shows though, Blackwell said, is that “when society creates the circumstances that allow those who have been left behind to participate and contribute fully, everyone wins.”There are multiple examples of this principle at work. For example, investing in policies that create more living-wage jobs or increase the availability of affordable housing certainly benefits people in communities that have limited options. But, the action also empowers those people with opportunities for better health and the means to become contributing members of society—and that benefits everyone. Even the football huddle (密商) was initially created to help deaf football players at Gallaudet College keep their game plans secret from opponents who could have read their sign language. Today, it’s used by every team to prevent theopponent from learning about game-winning strategies.So, next time you cross the street, or roll your suitcase through a crosswalk or ride your bike directly onto a sidewalk—think about how much the curb cut, that change in design that broke down walls of exclusion for one group of people at a disadvantage, has helped not just that group, but all of us.8.What does the underlined quote from the disability rights leader imply concerning asix-inch curb?A.It is an unforgettable symbol.B.It is an impassable barrier.C.It is an important sign.D.It is an impressive landmark. 9.According to Angela Blackwell, what do many people believe?A.It’s not worthwhile to promote health equity.B.It’s necessary to go all out to help the disabled.C.It’s impossible to have everyone treated equally.D.It’s fair to give the disadvantaged more help than others.10.Which of the following examples best illustrates the “curb cut effect” principle?A.Spaceflight designs are applied to life on earth.B.Four great inventions of China spread to the west.C.Christopher Columbus discovered the new world.D.Classic literature got translated into many languages.11.What conclusion can be drawn from the passage?A.Caring for disadvantaged groups may finally benefit all.B.Action empowers those with opportunities for better solutions.C.Society should create circumstances that get everyone involved.D.Everyday items are originally invented for people in need of help.Casting blame is natural: it is tempting to fault someone else for a mistake rather than taking responsibility yourself. But blame is also harmful. It makes it less likely that people will own up to mistakes, and thus less likely that organizations can learn from them. Research published in 2015 suggests that firms whose managers pointed to external factors to explain their failings underperformed companies that blamed themselves.Blame culture can spread like a virus. Just as children fear mom and dad’s punishment if they admit to wrongdoing, in a blaming environment, employees are afraid of criticism andpunishment if they acknowledge making a mistake at work. Blame culture asks, “who dropped the ball?” instead of “where did our systems and processes fail?” The focus is on the individuals, not the processes. It’s much easier to point fingers at a person or department instead of doing the harder, but the more beneficial, exercise of fixing the root cause, in which case the problem does not happen again.The No Blame Culture was introduced to make sure errors and deficiencies (缺陷) were highlighted by employees as early as possible. It originated in organizations where tiny errors can have catastrophic (灾难性的) consequences. These are known as high reliability organizations (HROs) and include hospitals, submarines and airlines. Because errors can be so disastrous in these organizations, it’s dangerous to operate in an environment where employees don’t feel able to report errors that have been made or raise concerns about that deficiencies may turn into future errors. The No Blame Culture maximizes accountability because all contributions to the event occurring are identified and reviewed for possible change and improvement.The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), which supervises air traffic across the United States, makes it clear that its role is not to assign blame or liability but to find out what went wrong and to issue recommendations to avoid a repeat. The proud record of the airline industry in reducing accidents partly reflects no-blame processes for investigating crashes and close calls. The motive to learn from errors also exist when the risks are lower. That is why software engineers and developers routinely investigate what went wrong if a website crashes or a server goes down.There is an obvious worry about embracing blamelessness. What if the website keeps crashing and the same person is at fault? Sometimes, after all, blame is deserved. The idea of the “just culture”, a framework developed in the 1990s by James Reason, a psychologist, addresses the concern that the incompetent and the malevolent (恶意的) will be let off the hook. The line that Britain’s aviation regulator draws between honest errors and the other sort is a good starting-point. It promises a culture in which people “are not punished for actions or decisions taken by them that match with their experience and training”. That narrows room for blame but does not remove it entirely.12.According to the research published in 2015, companies that ______ had better performance.A.blamed external factors B.admitted their mistakesC.conducted investigations D.punished the under performers 13.According to the passage, what do you learn about the No Blame Culture?A.It encourages the early disclosure of errors.B.It only exists in high reliability organizations.C.It enables people to shift the blame onto others.D.It prevents organizations from making any error.14.What is the major concern about embracing blamelessness according to the passage?A.Innocent people might take the blame by admitting their failure.B.Being blamed for mistakes can destroy trust in employees.C.The line between honest errors and the other sort is not clear.D.People won’t learn their lessons if they aren’t blamed for failures.15.Which of the following is the best title for the passage?A.Why We Fail to Learn from Our Own MistakesB.How to Avoid Disastrous Errors in OrganizationsC.Why We Should Stop the Blame Game at WorkD.How to Deal with Workplace Blame Culture二、七选五You’ve reached that special time — you are getting ready to leave your job and move on to the next step in your career. But the end of an employment relationship is not necessarily the end of the relationship — with either the leader or the company. 16I learned this relatively early in my career. At first, I was concerned I might lose my relationship with my now former boss, as I truly liked him. 17 My boss enthusiastically stayed in touch with me, and I helped him onboard my replacement and consulted on other projects. And now, more than 2 decades since I left, we are still in communication and friends.That isn’t to say it always goes like this. When I left another role, in spite of my desire to maintain communication, my former supervisor seemed indifferent and the relationship ended. Sometimes your boss was a nightmare and you want to end the relationship. 18 You don’t owe the bad bosses anything. That’s exactly what I did when I was fired from a freelance role after I asked to be paid for my completed work!But for the good bosses and organizations, the ones that invested in your talent and celebrated your achievements, things are different. 19 The breakup can become a breakthrough.20 Especially when you have a truly delightful and respectful boss, you may feel guilt, sadness, or regret. But your overall responsibility is to yourself and your career — not to one organization. And given the right circumstances, it is almost always possible — and usually beneficial — to leave gracefully.A.But it turned out I had no reason to fear.B.So the way I left contributed to this breakup.C.It’s completely understandable not to engage further.D.It is normal to have mixed emotions when you leave a job.E.Here are some ways to build a win-win with your former leader.F.The concusion of the employment can start a new era of cooperation.G.You can leave your company and keep the relationship at the same time.三、完形填空While doing some cleaning in my kitchen, I noticed a tiny black pellet(小球)on the shelf.was gone.Now I 33 peek(窥视)inside the dishwasher and the oven before turning them on. 34 , I know I am not the only one looking out for geckos. No 35 is too small for us to love.21.A.remembered B.discovered C.thought D.wished 22.A.approved of B.sought for C.fed on D.got into 23.A.fixed B.touched C.hurt D.lost 24.A.trouble B.danger C.failure D.pleasure 25.A.starvation B.thirst C.climate D.poverty 26.A.different B.simple C.interesting D.tough 27.A.kitchen B.bedroom C.garden D.lab 28.A.books B.woods C.stones D.bottles 29.A.arranged B.grasped C.cleaned D.removed 30.A.dropped B.obtained C.spotted D.rescued 31.A.agreed B.hoped C.feared D.promised 32.A.counted B.checked C.picked D.locked 33.A.even B.never C.still D.already 34.A.Nevertheless B.Instead C.Therefore D.Otherwise 35.A.place B.dream C.human D.creature四、用单词的适当形式完成短文阅读下面短文,在空白处填入1个适当的单词或括号内单词的正确形式。

高二英语说明文写作单选题40题1.Which of the following is the best topic for an expository essay?A.My favorite movieB.The history of basketballC.My summer vacationD.A day in my life答案:B。

“The history of basketball”是一个比较适合写说明文的主题,因为可以围绕篮球的起源、发展、规则变化等方面进行客观的阐述。

“My favorite movie”“My summer vacation”“A day in my life”更倾向于记叙文的主题。

2.What should be the main focus of an expository essay about animals?A.Personal opinions on different animalsB.The cuteness of various animalsC.Facts and characteristics of animalsD.Emotional stories about animals答案:C。

说明文关于动物应该主要聚焦在动物的事实和特征上。

“Personal opinions on different animals”是表达个人观点,不是说明文重点。

“The cuteness of various animals”比较主观,也不是说明文重点。

“Emotional stories about animals”属于记叙文范畴。

3.When writing an expository essay on technology, which of the following is least relevant?A.Personal experiences with technologyB.The impact of technology on societyC.The development of technology over timeD.Different types of technology答案:A。

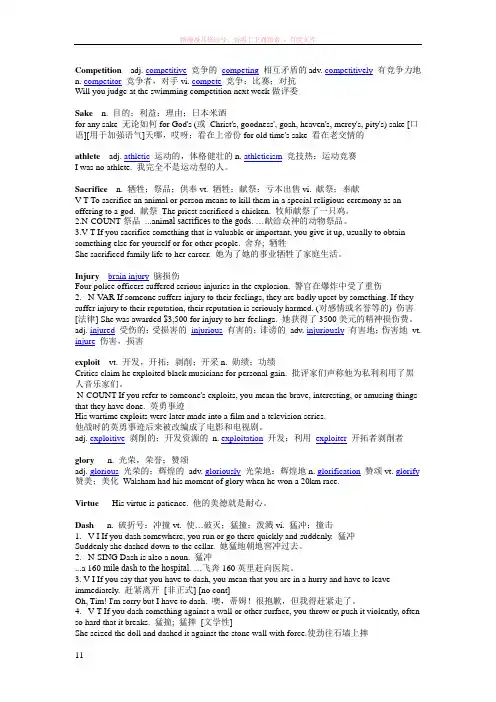

Competition adj. competitive竞争的competing相互矛盾的adv. competitively有竞争力地n. competitor竞争者,对手vi. compete竞争;比赛;对抗Will you judge at the swimming competition next week做评委Sake n. 目的;利益;理由;日本米酒for any sake 无论如何for God's (或Christ's, goodness', gosh, heaven's, mercy's, pity's) sake [口语][用于加强语气]天哪,哎呀;看在上帝份for old time's sake 看在老交情的athlete adj. athletic运动的,体格健壮的n. athleticism竞技热;运动竞赛I was no athlete. 我完全不是运动型的人。

Sacrifice n. 牺牲;祭品;供奉vt. 牺牲;献祭;亏本出售vi. 献祭;奉献V-T To sacrifice an animal or person means to kill them in a special religious ceremony as an offering to a god. 献祭The priest sacrificed a chicken. 牧师献祭了一只鸡。

2.N-COUNT祭品...anim al sacrifices to the gods. …献给众神的动物祭品。

3.V-T If you sacrifice something that is valuable or important, you give it up, usually to obtain something else for yourself or for other people. 舍弃; 牺牲She sacrificed family life to her career. 她为了她的事业牺牲了家庭生活。

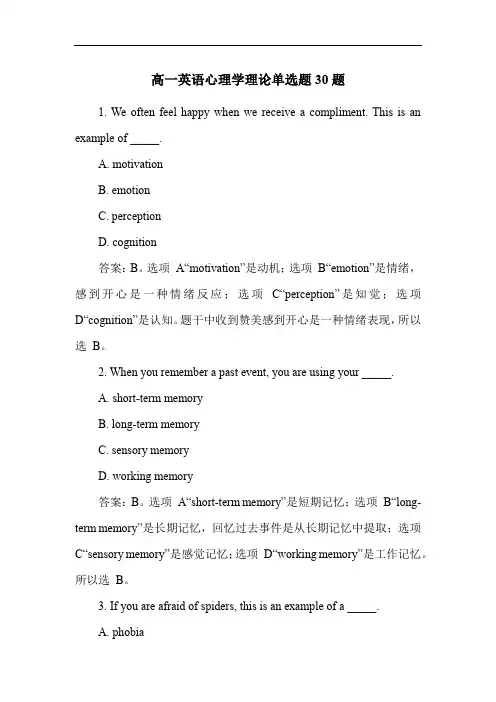

高一英语心理学理论单选题30题1. We often feel happy when we receive a compliment. This is an example of _____.A. motivationB. emotionC. perceptionD. cognition答案:B。

选项A“motivation”是动机;选项B“emotion”是情绪,感到开心是一种情绪反应;选项C“perception”是知觉;选项D“cognition”是认知。

题干中收到赞美感到开心是一种情绪表现,所以选B。

2. When you remember a past event, you are using your _____.A. short-term memoryB. long-term memoryC. sensory memoryD. working memory答案:B。

选项A“short-term memory”是短期记忆;选项B“long-term memory”是长期记忆,回忆过去事件是从长期记忆中提取;选项C“sensory memory”是感觉记忆;选项D“working memory”是工作记忆。

所以选B。

3. If you are afraid of spiders, this is an example of a _____.A. phobiaB. habitC. preferenceD. hobby答案:A。

选项A“phobia”是恐惧症,害怕蜘蛛是一种恐惧症的表现;选项B“habit”是习惯;选项C“preference”是偏好;选项D“hobby”是爱好。

所以选A。

4. When you solve a math problem, you are using your _____.A. creativityB. intelligenceC. memoryD. imagination答案:B。

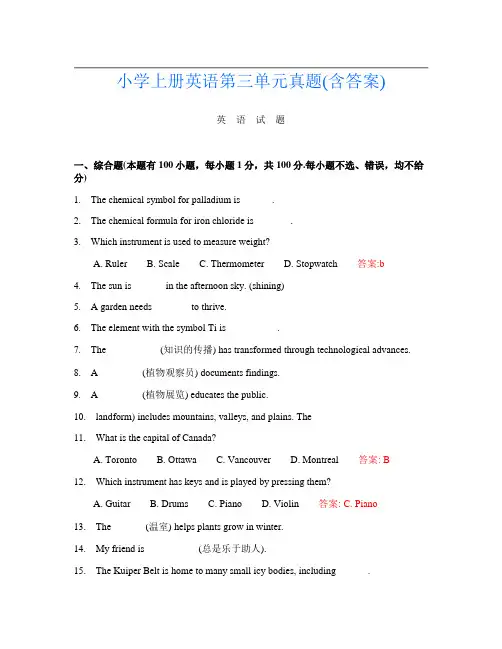

小学上册英语第三单元真题(含答案)英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.The chemical symbol for palladium is ______.2.The chemical formula for iron chloride is _______.3.Which instrument is used to measure weight?A. RulerB. ScaleC. ThermometerD. Stopwatch答案:b4.The sun is ______ in the afternoon sky. (shining)5. A garden needs _______ to thrive.6.The element with the symbol Ti is __________.7.The __________ (知识的传播) has transformed through technological advances.8. A ________ (植物观察员) documents findings.9. A ________ (植物展览) educates the public.ndform) includes mountains, valleys, and plains. The ____11.What is the capital of Canada?A. TorontoB. OttawaC. VancouverD. Montreal答案: B12.Which instrument has keys and is played by pressing them?A. GuitarB. DrumsC. PianoD. Violin答案: C. Piano13.The ______ (温室) helps plants grow in winter.14.My friend is __________ (总是乐于助人).15.The Kuiper Belt is home to many small icy bodies, including ______.16.What is the capital of Kazakhstan?A. AlmatyB. Nur-SultanC. ShymkentD. Karaganda答案: B17.My family goes to the ____.18.The __________ (文艺复兴) brought about changes in art and science.19.What do we call a person who studies the economy?A. EconomistB. PoliticianC. SociologistD. Businessman答案: A20.The process of ______ can change the landscape over time.21. A snail carries its ______ on its back.22.The flamingo stands on one _______ (腿) while resting.23.The Earth's crust is rich in various ______ elements.24.What do you call the main character in a story?A. AntagonistB. ProtagonistC. Supporting CharacterD. Narrator答案: B25. A __________ is a mixture of two or more gases.26.What is the name of the fairy tale character who wore a red hood?A. CinderellaB. Sleeping BeautyC. Little Red Riding HoodD. Rapunzel答案:C27.The ability to conduct heat varies among different _____.28.The _____ (空气) around us is important for plants to breathe.29.The chemical symbol for hydrogen is __________.30.Acids can turn blue litmus paper ______.31.She is ________ her favorite song.32.I can create a _________ (玩具公园) for my toy animals.33.The fish swims in the ________ (水).34.My pet _______ (仓鼠) is very cute.35.The ancient Greeks believed in the power of ________.36.What is the name of the small, red fruit that is often mistaken for a vegetable?A. TomatoB. PeachC. CherryD. Strawberry答案: A37.We have a _____ (梦) of traveling.38.I see a __ on the fence. (butterfly)39.My uncle is a talented __________ (作家).40.I have a pet ________ (猫) that likes to sleep a lot.41.My sister is a great __________ (歌手).42.My dog loves to _______ (玩耍) with its toys.43. A saturated fat is ______ at room temperature.44.My brother is very ________.45.The kitten is ______ with a ball of yarn. (playing)46.What is 7 + 3?A. 9B. 10C. 11D. 12答案:B.1047.Every season has its own ______ (魅力).48.The _____ (湖泊) is calm.49.The __________ is a major river that flows through Russia. (伏尔加河)50.Which animal is known for its black and white stripes?A. TigerB. ZebraC. LeopardD. Cheetah答案: B51.Mushrooms are a type of ______ (真菌), not a plant.52.The Renaissance began in _______.53.We celebrate ________ (success) as a group.54.I saw a _______ (小鸭子) following its mother.55.My aunt loves __________ (跳舞).56.Which of these animals is a reptile?A. FrogB. LizardC. RabbitD. Dolphin答案: B57.The chemical symbol for nitrogen is ______.58.The ______ is the main organ for breathing.59.Photosynthesis converts sunlight into ______ energy.60.My teacher is very __________ (鼓励的).61.Rainforests are known for their rich ______.62.The __________ (土壤的pH值) can affect plant health dramatically.63.The __________ (历史的视角) can highlight bias.64.I can ________ a song on the piano.65.My cousin is an amazing __________ (演员) in school plays.munity engagement toolkit) provides resources for involvement. The ____67.The __________ (历史的探索) unveils insights.68. A fish can breathe underwater with its ______ (鳃).69.She is wearing a _____ hat. (yellow)70.The flowers are ___ (blooming/fading).71.The ______ (果实) of a plant develops from its flowers.72.Mars rovers send back pictures and ______.73.What is the boiling point of water in degrees Celsius?A. 50B. 75C. 100D. 120答案:C74.The bison roams the ______ (草原).75.I like to make ______ for my teachers.76. A _______ is a process that involves mixing.77.In which direction does the sun rise?A. NorthB. SouthC. EastD. West答案:C78.What is the process of changing from a liquid to a gas?A. EvaporationB. CondensationC. FreezingD. Melting答案: A79.I love to watch ______ (舞蹈表演). It’s amazing to see the creativity and talent of the performers.80.My family goes _____ every summer. (camping)81. A compound with a high melting point is likely to be an ______.82.The sound of rain is very ______ (放松).83.The country famous for its poets is ________ (波兰).84.The chemical symbol for silver is ______.85.The capital of Mali is __________.86.I have a favorite ______ (毛绒玩具) that I take everywhere with me.87. A solution that does not conduct electricity is called a ______ solution.88.I enjoy _____ (骑自行车) in the park.89.The sun is shining ________.90.What do you call the action of preparing food for a meal?A. CookingB. BakingC. RoastingD. Grilling答案: A91. A solvent is the substance that dissolves a ______.92.I see a _______ (hawk) flying above.93.What is the capital of the Czech Republic?A. PragueB. BudapestC. BratislavaD. Warsaw答案: A. Prague94.We develop ________ (strategies) for success.95.The Earth's surface is shaped by both internal and external ______.96.The dog is ______ (barking) loudly.97.She has a _____ (colorful) backpack.98.The ancient Egyptians practiced _______ to preserve bodies.99.What do you call a person who repairs watches?A. JewelerB. ClockmakerC. HorologistD. Mechanic答案: C 100.The coach, ______ (教练), teaches us how to play sports.。

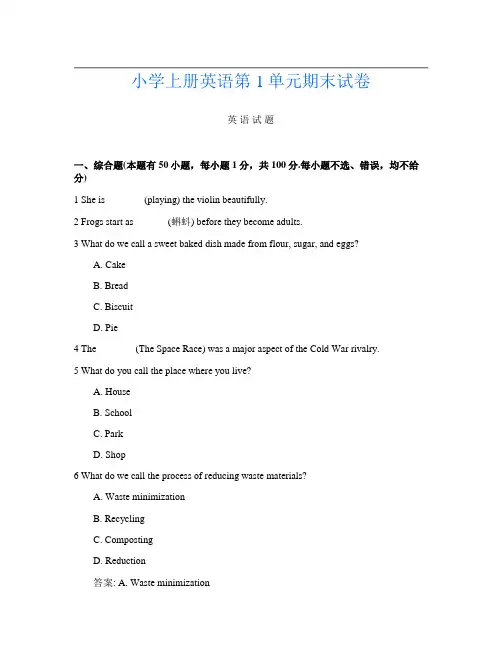

小学上册英语第1单元期末试卷英语试题一、综合题(本题有50小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1 She is _______ (playing) the violin beautifully.2 Frogs start as ______ (蝌蚪) before they become adults.3 What do we call a sweet baked dish made from flour, sugar, and eggs?A. CakeB. BreadC. BiscuitD. Pie4 The _______ (The Space Race) was a major aspect of the Cold War rivalry.5 What do you call the place where you live?A. HouseB. SchoolC. ParkD. Shop6 What do we call the process of reducing waste materials?A. Waste minimizationB. RecyclingC. CompostingD. Reduction答案: A. Waste minimization7 What do you call a baby tiger?A. CubB. KitC. PupD. Calf8 The ______ is often seen in parks.9 I enjoy sharing my _________ (玩具) stories with my classmates.10 What do we call a young male horse?A. FillyB. ColtC. FoalD. Calf答案:B. Colt11 A _______ reaction occurs when substances combine to form a new substance.12 The ________ hops around and explores.13 We are having ______ for dinner tonight. (pizza)14 What do we call a person who travels in space?A. PilotB. AstronautC. CosmonautD. Scientist答案: B15 A windmill converts wind energy into ______.16 The ancient Greeks valued ________ (艺术和哲学).17 A ______ is a sea creature with a shell.18 My sister loves to __________ (听音乐) while studying.19 What is the name of the process that plants use to make food using sunlight?A. RespirationB. PhotosynthesisC. TranspirationD. Fermentation答案:B20 A solution that can no longer dissolve any more solute is called a _______ solution.21 A ______ (羊) bleats softly in the pasture.22 What is the smallest prime number?A. 0B. 1C. 2D. 3答案:C23 The _____ (海豹) is often seen on rocky shores.24 What do we call the act of engaging in self-reflection?A. IntrospectionB. ContemplationC. MeditationD. All of the Above答案:D25 We can _______ a fun project together.26 My friend is a ______. She loves to paint.27 The _____ (海滩) is sunny.28 I enjoy ______ (学习) about different subjects.29 The ancient Egyptians used ________ to document their history.30 What is the main ingredient in chocolate?A. SugarB. Cocoa beansC. MilkD. Flour答案:B31 I have a _____ (有趣的事情) to share.32 My friend has a unique __________ (世界观).33 are a famous ________ (阿尔卑斯山是一座著名的________) range in Europe. The Amaz34 The first electric vehicle was built in the _______ century. (19)35 The chemical symbol for gallium is ______.36 The __________ was a time of great technological advancement. (工业革命)37 My sister is a great __________ (学习者).38 The movie was very ___. (funny)39 The color of a flame can indicate the presence of certain ________.40 The ______ (猩猩) lives in trees and is very strong.41 Matter is anything that has ________ and takes up space.42 What type of animal is a frog?A. MammalB. ReptileC. BirdD. Amphibian答案: D. Amphibian43 A caribou migrates during the ________________ (季节).44 What is the opposite of "fast"?A. QuickB. SlowC. RapidD. Speedy答案:B45 Many cultures use plants in __________ (传统医学).46 The parrot loves to sit on _______ (肩膀).47 What do we call the process of converting a liquid into a solid?A. FreezingB. MeltingC. EvaporationD. Condensation48 The puppy is ______ (非常可爱) and fluffy.49 What type of animal is a dolphin?A. FishB. MammalC. ReptileD. Amphibian答案: B50 What is the opposite of 'wet'?A. DryB. DampD. Moist答案:A51 A __________ is an area where fresh and saltwater mix.52 What do you call the machine that helps you cook food?A. OvenB. RefrigeratorC. DishwasherD. Microwave53 A ____(green technology) develops innovative solutions.54 I want to learn how to ___. (dance)55 Saturn's rings are composed of billions of ______.56 What do you call a person who swims?A. DiverB. SurferC. SwimmerD. Sailor答案:C57 The jellyfish has a bell-shaped ________________ (身体).58 The _______ (小金色) is a common pet for many families.59 n Tea Party was a protest against ________. The Bost60 The chemical symbol for tantalum is ______.61 The state of matter that has a definite volume but not a definite shape is _______.62 What do you call someone who studies the stars?A. GeologistC. AstronomerD. Meteorologist答案:C63 The bird is singing ___. (sweetly)64 Which of these is a type of fabric?A. CottonB. WoodC. MetalD. Stone答案:A65 The __________ can indicate the presence of ancient life forms in rock.66 What do bees produce?A. MilkB. HoneyC. SugarD. Butter67 My brother is ___ (tall/short) for his age.68 Gardening can be an excellent way to spend time outdoors and enjoy ______. (园艺是花时间在户外并享受自然的绝佳方式。

2025届仿真模拟★第02套2025年普通高等学校招生全国统一考试英语注意事项:1.答卷前,考生务必将自己的姓名、准考证号填写在答题卡和试卷指定位置上。

2.回答选择题时,选出每小题答案后,用铅笔把答题卡上对应题目的答案标号涂黑。

如需改动,用橡皮擦干净后,再选涂其他答案标号。

回答非选择题时,将答案写在答题卡上,写在本试卷上无效。

3.考试结束后,将本试卷和答题卡一并交回。

英语听力 高三模拟 第2025-02套.mp4第一部分听力(共两节,满分30分)做题时,先将答案标在试卷上。

录音内容结束后,你将有两分钟的时间将试卷上的答案转涂到答题卡上。

第一节(共5小题;每小题1.5分,满分7.5分)听下面5段对话。

每段对话后有一个小题,从题中所给的A、B、C三个选项中选出最佳选项。

听完每段对话后,你都有10秒钟的时间来回答有关小题和阅读下一小题。

每段对话仅读一遍。

例:How much is the shirt?A. £19.15.B. £9.18.C. £9.15.答案是C。

1.Where does the conversation probably take place?A. In a supermarket.B. In the post office.C. In the street. 2.What did Carl do?A. He designed a medal.B. He fixed a TV set.C. He took a test.3.What does the man do?A. He’s a tailor.B. He’s a waiter.C. He’s a shop assistant. 4.When will the flight arrive?A. At 18:20.B. At 18:35.C. At 18:50.5.How can the man improve his article?A. By deleting unnecessary words.B. By adding a couple of points.C. By correcting grammar mistakes.第二节(共15小题;每小题1.5分,满分22.5分)听下面5段对话或独白。

高二英语阅读推理判断单选题45题1. The article mentions that scientists have discovered a new species of animal. What kind of environment is this new species most likely to live in?A. DesertB. RainforestC. MountainD. Ocean答案:B。

解析:文章中提到科学家发现新物种,科普类文章中通常新物种多在生态丰富的环境中被发现,雨林环境生物多样性丰富,最有可能是新物种生存的环境。

A 选项沙漠环境恶劣,生物种类相对较少;C 选项山地环境虽然也可能有一些特殊物种,但不如雨林可能性大;D 选项海洋环境如果没有特殊提示一般不太可能是刚被发现的新物种生存环境。

2. According to the text, which of the following is NOT a characteristic of a certain scientific phenomenon?A. ColorfulB. LoudC. FastD. Quiet答案:A。

解析:文章中对该科学现象进行了描述,其中没有提到色彩斑斓这个特征。

B 选项大声如果文中有相关声音描述可能是特征;C 选项快速如果文中有涉及速度可能是特征;D 选项安静如果文中有关于安静的表述可能是特征。

3. The passage says that a particular experiment was conducted. What was the main purpose of this experiment?A. To prove a theoryB. To create a new productC. To solve a problemD. To entertain people答案:A。

机械工程英语考试题及答案一、选择题(每题2分,共20分)1. The term "mechanical engineering" refers to the field that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of machines.A. TrueB. False答案:A2. Which of the following is not a type of machine element?A. GearB. PistonC. LeverD. Circuit答案:D3. The study of forces and their effects on the motion of objects is known as:A. ThermodynamicsB. MechanicsC. Fluid dynamicsD. Electromagnetism答案:B4. In mechanical engineering, what is the SI unit for torque?A. Newton-meter (Nm)B. Pascal (Pa)C. Joule (J)D. Watt (W)答案:A5. What is the process of converting electrical energy into mechanical energy called?A. ElectromagnetismB. ElectrolysisC. Electromechanical conversionD. Electrostatics答案:C6. A system of units based on the meter, kilogram, and second is known as the:A. CGS systemB. FPS systemC. SI systemD. MKS system答案:C7. What is the primary function of a bearing in a mechanical system?A. To reduce frictionB. To increase frictionC. To generate heatD. To store energy答案:A8. The process of removing material from a workpiece to achieve the desired shape and size is called:A. CastingB. MachiningC. WeldingD. Annealing答案:B9. Which of the following materials is not typically used in mechanical engineering?A. SteelB. PlasticC. ConcreteD. Rubber答案:C10. The study of the behavior of materials under various types of applied loads is known as:A. Material scienceB. Structural engineeringC. Civil engineeringD. Mechanical engineering答案:A二、填空题(每题2分,共20分)1. The ________ is a device that converts the rotational motion of an engine into linear motion.答案:piston2. A ________ is a mechanical device that can multiply force or distance.答案:lever3. The ________ is the point where all forces acting on a body act.答案:center of gravity4. A ________ is a type of machine that uses a rotating shaft to apply torque to a workpiece.答案:lathe5. The ________ is a measure of the resistance of a material to deformation.答案:stiffness6. ________ is the process of joining two or more pieces of metal by melting and fusing them together.答案:welding7. A ________ is a machine that uses a rotating blade to move or lift substances.答案:pump8. ________ is the study of the strength and properties of materials.答案:material science9. ________ is the process of changing the shape or size of a material by applying force.答案:deformation10. ________ is the process of removing material from a workpiece by cutting.答案:machining三、简答题(每题10分,共40分)1. Explain the difference between static and dynamic equilibrium in mechanical systems.答案:Static equilibrium refers to a state where all forces acting on a body are balanced, resulting in no acceleration. Dynamic equilibrium occurs when the net force acting on abody is zero, but the body is still moving at a constant velocity.2. Describe the function of a gearbox in a mechanical system. 答案:A gearbox is a mechanical device that transmits power from a prime mover to a machine by converting rotationalspeed and torque. It changes the speed and torque of theinput shaft to the output shaft, allowing for different operating speeds and torques in various applications.3. What are the three main types of stress that a materialcan experience?答案:The three main types of stress are tensile stress, compressive stress, and shear stress. Tensile stress occurs when a material is pulled apart, compressive stress occurs when a material is compressed, and shear stress occurs when two parallel planes of a material slide past each other.4. Explain the concept of power in mechanical engineering.答案:Power in mechanical engineering is the rate at which work is done or energy is transferred. It is the product of force and velocity, and it is typically measured in watts (W). Power can be calculated as the work done per unit time, andit is an important parameter in the design and operation of mechanical systems.。

小学上册英语第3单元真题试卷(有答案)英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.What is the capital of France?A. ParisB. LondonC. TokyoD. Berlin答案:A Paris2. A ______ has a pouch for carrying its baby.3.__________ (有机化合物) contain carbon and are found in living things.4.We go _____ (徒步旅行) in the mountains.5.The _____ (小鸭) swims alongside its mother.6.The discovery of ________ has changed our understanding of physics.7.The chemical formula for magnesium nitride is _______.8.The ______ (生态系统) relies on healthy plant life.9.Where does the sun rise?A. WestB. NorthC. SouthD. East答案:D10.The process of ______ can lead to the creation of canyons.11.The cat is ______ on the window. (sitting)12.Road was a trade route between _____ and Europe. The Silk13.ts have thick leaves to store ______. (某些植物有厚厚的叶子来储存水分。

) Some pla14.The chemical symbol for potassium is _______.15.The ______ (海豚) communicates with clicks and whistles.16.The atomic number tells us the number of ______ in an atom.17. A _____ (小狼) howls at the moon.18.I want to ________ (visit) my grandma.19.I enjoy going camping with my family. We set up a ______ (帐篷) and roast marshmallows over the fire.20.My mom is a __________ (艺术教育者).21.The ________ (保护措施) help save endangered species.22.I enjoy playing ________ (桌上游戏) with my friends.23.I want to be a ___ (scientist/artist).24.I found a _____ (足球) in the park.25.正确抄写下列字母,每个写一遍。

2025年牛津译林版英语中考仿真试题与参考答案一、听力部分(本大题有20小题,每小题1分,共20分)1、Listen to the following conversation and choose the best answer to the question you hear.A. The man is asking for directions.B. The woman is trying to find a restaurant.C. The man is recommending a hotel.Answer: B解析:This question tests your ability to understand a short dialogue. The woman mentions that she is looking for a place to eat, indicating that she is trying to find a restaurant. The other options are not supported by the dialogue.2、Listen to the following short passage and answer the question.How many people are planning to attend the conference this year?A. 50B. 100C. 150Answer: C解析:This question requires you to listen for specific numbers. In the passage, it is mentioned that the conference is expecting 150 participants this year, making option C the correct answer. The other numbers are not mentionedin the passage.3、Question: Listen to the following conversation and answer the question.A. What is the man planning to do this weekend?B. Where does the woman usually go for her morning walk?C. What is the weather forecast for this weekend?Answer: AExplanation: In the conversation, the man mentions that he is planning to go hiking this weekend, indicating his weekend plans.4、Question: Listen to the following news report and answer the question. What is the main cause of the recent traffic congestion in the city?A. Construction work on a major roadB. An unexpected increase in the number of touristsC. A sudden snowstorm that blocked trafficAnswer: AExplanation: The news report specifically mentions that construction work on a major road has caused the traffic congestion, making option A the correct answer.5、Listen to the dialogue between two friends and answer the question.A. What is the weather like today?B. What are they planning to do this weekend?C. Who is responsible for the party preparation?Answer: BExplanation: In the dialogue, the two friends are discussing their plans for the weekend, indicating that they are making arrangements for an event.6、Listen to the following passage about a famous landmark and answer the question.Question: What is the main purpose of the passage?A. To describe the history of the landmarkB. To provide a detailed map of the landmarkC. To explain the significance of the landmark in the local culture Answer: CExplanation: The passage focuses on the cultural importance of the landmark in the community, which is the main theme discussed.7.You will hear a short conversation between two friends. Listen carefully and choose the best answer to the question.Question: What is the man’s plan for the weekend?A) To go to the movies.B) To stay at home and read.C) To visit his grandparents.Answer: AExplanation: In the conversation, the man says, “I’m going to the movies this weekend. I heard they’re showing a new action movie.” This indicates that his plan is to go to the movies.8.You will hear a short dialogue between a student and a teacher. Listencarefully and answer the question.Question: What is the student’s problem with the assignment?A) He doesn’t understand the instructions.B) He can’t find the necessary materials.C) He has too much homework.Answer: AExplanation: In the dialogue, the student says, “I’m really confused about the assignment. I don’t know what to do.” This suggests that the student’s problem is that he doesn’t understand the instructions for the assig nment.9.You will hear a short conversation between two students about their weekend plans. Listen carefully and answer the following question.Question: What activity does the second student plan to do on Saturday afternoon?A. Go to the movies.B. Visit a friend.C. Attend a sports game.D. Stay at home and read.Answer: BExplanation: The second student mentions that they have a friend coming over on Saturday afternoon, which implies that they will be visiting their friend. Therefore, the correct answer is B. Visit a friend.10.You will hear a monologue about the importance of environmentalprotection. Listen carefully and answer the following question.Question: According to the speaker, what is the most effective way to reduce carbon emissions?A. Use public transportation more often.B. Recycle and reuse materials.C. Eat less meat.D. All of the above.Answer: DExplanation: The speaker emphasizes the importance of taking various actions to reduce carbon emissions, such as using public transportation, recycling, reusing materials, and eating less meat. Therefore, the correct answer is D. All of the above.11.You are listening to a conversation between two students, Alice and Bob, discussing their weekend plans.Alice: Hey Bob, are you free this weekend?Bob: Yeah, I am. What are you planning to do?Alice: I was thinking of going hiking in the countryside. It’s been a while since I did that.Bob: That sounds great! I could use some fresh air too. How about meeting at the park on Saturday morning?Alice: Perfect! What time should we meet?Bob: How about 8:00? It will give us enough time to get there and start early.Alice: Okay, 8:00 it is. I’ll bring some snacks and water.Bob: Good idea. I’ll bring a backpack and some hiking boots.Question: What activity is Alice planning to do this weekend?A) Go hikingB) Go swimmingC) Go campingD) Go sightseeingAnswer: A) Go hiking解析:This question can be answered by listening to Alice’s statement, “I was thinking of going hiking in the countryside.” She exp licitly mentions her plan to go hiking.12.You are listening to a news report about a local charity event.Anchor: Good evening, this is the local news. Tonight, we have a special report on an upcoming charity event that will take place this weekend. It’s called “Community United.” The event aims to raise funds for local families in need.Interviewer: Thank you, Anchor. We’re joined by the event organizer, Sarah Johnson. Sarah, can you tell us more about the event?Sarah: Absolutely. “Community United” will be held on Saturday from 10:00 AM to 4:00 PM at the city park. There will be a variety of activities, including a bake sale, a silent auction, and a raffle.Interviewer: That sounds exciting. How much has the charity raised so far?Sarah: We have raised$5,000 so far, but we’re hoping to double that amount by the end of the event.Interviewer: That’s fantastic. How can people get involved?Sarah: They can donate money, volunteer their time, or simply come out and support the event. Every little bit helps.Q uestion: What is the main purpose of the “Community United” event?A) To raise funds for local businessesB) To raise funds for local families in needC) To promote tourism in the cityD) To provide free healthcare servicesAnswer: B) To raise funds for local families in need解析:The purpose of the event is clearly stated by Sarah, “The event aims to raise funds for local families in need.” This answers the question directly.13.You will hear a conversation between two friends discussing their weekend plans. Listen carefully and answer the question.Question: What activity do the friends decide to do together on Saturday afternoon?A. Go shoppingB. Visit a museumC. Have a picnicD. Go to a movieAnswer: BExplanation: In the conversation, one friend suggests visiting a museum because they are interested in history. The other friend agrees, so they decide to go to the museum together on Saturday afternoon.14.Listen to a short passage about the importance of exercise. After listening, complete the following statement.Question: According to the passage, regular exercise can help improve which of the following?A. Academic performanceB. Sleep qualityC. Diet habitsD. Work efficiencyAnswer: BExplanation: The passage clearly states that regular exercise can help improve sleep quality, which is the correct answer. The other options are not mentioned in the passage.15.You will hear a conversation between two students discussing their study plans. Listen carefully and answer the following question.Question: What subject are they planning to study together?A. MathematicsB. HistoryC. PhysicsD. ChemistryAnswer: BExplanation: In the conversation, one of the students mentions that they have a history assignment due next week and asks if the other student would like to study together. Therefore, the subject they are planning to study together is History.16.You will hear a short speech by a university professor about the importance of teamwork in the workplace. Listen carefully and answer the following question.Question: According to the professor, what are some benefits of teamwork?A. Higher productivityB. Increased creativityC. Improved communicationD. All of the aboveAnswer: DExplanation: The professor in the speech mentions that teamwork leads to higher productivity, increased creativity, and improved communication. Therefore, the correct answer is “All of the above.”17.You will hear a short conversation between two friends about their weekend plans. Listen carefully and choose the best answer to the question.Question: What does Tom plan to do on Sunday afternoon?A. Visit his grandparents.B. Go shopping with his sister.C. Attend a basketball game.Answer: AExplanation: The woman says, “You know, Tom, your grandparents are coming to visit this weekend.” This indicates that Tom has plans to visit his grandparents on Sunday afternoon.18.You will hear a short passage about the importance of exercise. Listen carefully and answer the question.Question: According to the passage, what are the benefits of regular exercise?A. It helps you stay healthy and fit.B. It can improve your memory and concentration.C. It reduces stress and anxiety.Answer: DExplanation: The passage states, “Regular exercise can help you stay healthy and fit, improve your memory and concentration, and reduce stress and anxiety.” Therefore, the correct answer is “All of the above,” which is not listed as an option, so we choose the closest one, which is D.19.Question: What is the name of the author that the speaker is discussing in the book?A)J.K. RowlingB)J.R.R. TolkienC)Agatha ChristieD)Charles DickensAnswer: B) J.R.R. TolkienExplanation: The speaker mentions that the book focuses on the life and works of J.R.R. Tolkien, the author of “The Lord of the Rings.”20.Question: How does the speaker describe the setting of the story?A) A peaceful countrysideB) A bustling cityC) A mysterious forestD)An ancient castleAnswer: C) A mysterious forestExplanation: The speaker describes the story as taking place in a “mysterious forest,” which is filled with magical creatures and unexpected twists.二、阅读理解(30分)Title: The Power of MusicReading Passage:Music has always been a significant part of human culture. It transcends language barriers and brings people together from different backgrounds. The power of music can be seen in various aspects of life, from personal experiences to global events. In this article, we will explore the different ways in which music impacts our lives.One of the most notable impacts of music is its ability to evoke emotions. When we listen to music, our brain releases neurotransmitters that make us feel happy, sad, or excited. This emotional connection can create a sense of unity and understanding among people who may otherwise have little in common. For instance, during times of crisis, such as natural disasters or wars, music can provide comfort and solace to those affected.Music also plays a crucial role in the development of a child’s cognitive abilities. Studies have shown that listening to music can improve memory, attention span, and even mathematical skills. The rhythm and patterns in music help the brain to organize information, making it easier for children to learn new things.Furthermore, music has a profound impact on our social lives. It is a universal language that can be used to express love, joy, sorrow, and triumph. In social settings, music can help to break the ice and create a more relaxed atmosphere. It can also serve as a bonding experience, as people come together to share their favorite tunes.Question:What is the primary purpose of the article?A. To discuss the history of musicB. To explore the different ways in which music impacts our livesC. To analyze the effects of music on children’s cognitive developmentD. To compare the role of music in different culturesAnswer: B. To explore the different ways in which music impacts our lives Question:According to the article, how does music help people during times of crisis?A. It distracts them from their problemsB. It provides comfort and solaceC. It encourages them to fight harderD. It helps them to forget their troublesAnswer: B. It provides comfort and solaceQuestion:The article mentions that music can improve a child’s cognitive abilities. Which of the following is NOT mentioned as an improvement?A. MemoryB. Attention spanC. Mathematical skillsD. Reading comprehensionAnswer: D. Reading comprehension三、完型填空(15分)Section 3: Cloze TestRead the following passage and choose the best word for each blank from the options given below.In the small town of Windermere, the local library had always been a hubof community activity. It was a place where people of all ages could come together, exchange ideas, and find solace in the pages of a book. However, as time went by, the library faced a challenge that threatened its very existence.One day, the librarian, Mrs. Thompson, noticed a peculiar trend. The number of children visiting the library had begun to decline. She worried that the library might lose its youthful spirit if this continued. To address the issue, she decided to launch a campaign to “revitalize” the library.1.Mrs. Thompson was concerned about the decline in the number of_______visitingthe library.a) adultsb) childrenc) volunteersd) donors2.The library had always been a place where people could _______.a) study aloneb) exchange ideasc) borrow books for freed) attend workshops3.Mrs. Thompson believed that the library’s youthful spirit could be saved by _______.a) charging admissionb) reducing the collectionc) offering special programsd) closing it down4.To revitalize the library, Mrs. Thompson planned to _______.a) increase the number of booksb) decrease the hours of operationc) introduce new technologiesd) exclude children5.The campaign to revitalize the library aimed to _______.a) attract more young readersb) raise funds for renovationsc) replace the librariand) hold a book saleAnswers:1.b) children2.b) exchange ideas3.c) offering special programs4.c) introduce new technologies5.a) attract more young readers四、语法填空题(本大题有10小题,每小题1分,共10分)1、The__________(be) of the book is very interesting.A. authorB. authorsC. author’sD. authors’Answer: CExplanation: The correct answer is “author’s” because it is the possessive form, indicating ownership or relationship to the book.2、She__________(not only) read the book but also wrote a review about it.A. hasB. haveC. hadD. have beenAnswer: AExplanation: The correct answer is “has” because “not only… but also” is a correlative conjunction that connects two clauses with the same subject, and the subject here is “She,” which is singular.3、In the___________meeting, the decision was made to start the project next month.A. nextB. followingC. upcomingD. latestAnswer: C. upcomingExplanation: The correct answer is “upcoming” because it refers to afuture event that is about to happen. The phrase “in the upcoming meeting” suggests a meeting that is going to take place in the near future.4、She___________(be) in the library when I called her.A. isB. wasC. wereD. beAnswer: B. wasExplanation: The correct answer is “was” because the sentence describes a past event. The past continuous tense is used to describe an action that was happening at a specific time in the past, which is indicated by “when I called her.”5.I have been looking forward to__________(go) your party next weekend.答案:going解析:本题考查动词的用法。

托福听力tpo40 全套对话讲座原文+题目+答案+译文Section 1 (2)Conversation1 (2)原文 (2)题目 (5)答案 (7)译文 (7)Lecture1 (9)原文 (9)题目 (12)答案 (15)译文 (15)Lecture2 (17)原文 (17)题目 (21)答案 (23)译文 (23)Section 2 (26)Conversation2 (26)原文 (26)题目 (28)答案 (30)译文 (30)Lecture3 (32)原文 (32)题目 (36)答案 (39)译文 (39)Lecture4 (42)原文 (42)题目 (45)答案 (48)译文 (48)Section 1Conversation1原文NARRATOR: Listen to a conversation between a student and a business professor.MALE STUDENT: Thanks for seeing me, Professor Jackson.FEMALE PROFESSOR: Sure, Tom. What can I do for you?MALE STUDENT: I'm gonna do my term project on service design, uh, what you see as a customer …the physical layout of the building, the parking lot. And I thought I'd focus on various kinds of eateries …restaurants, coffee shops, cafeterias, so I'd also analyze where you order your food, where you eat, and so on.FEMALE PROFESSOR: Wait, I thought you were going to come up with a hypothetical business plan for an amusement park? Isn’t that what you e-mailed me last week?I could've sworn …. Oh! I'm thinking of a Tom from another class.Tom Benson. Sorry, sorry.MALE STUDENT: No problem. I did e-mail you my idea too, though …. FEMALE PROFESSOR: Oh, that's right. I remember now. Restaurants …yeah …MALE STUDENT: So, here's my question. I read something about service standard that kinda confused me. What’s the difference between service design and service standard?FEMALE PROFESSOR: Service standard refers to what a company …employees …are ideally supposed to do in order for everything to operate smoothly. The protocols to be followed.MALE STUDENT: Oh, OK.FEMALE PROFESSOR: Um, so backing up…Service design is…uh, think of the cafeteria here on campus. There are several food counters, right? All with big, clear signs to help you find what you're looking for—soups, salads, desserts—so you know exactly where to go to get what you need. And when you're finished picking up your food, where do you go?MALE STUDENT: To the cash registers.FEMALE PROFESSOR: And where are they?MALE STUDENT: Um, right before you get to the seating area.FEMALE PROFESSOR: Exactly. A place that you would logically move to next.MALE STUDENT: You know, not every place is like that. This past weekend was my friend's birthday, and I went to a bakery in town, to pick up a cake for her party. And the layout of the place was weird: People were allin each other's way, standing in the wrong lines to pay, to place orders…. Oh! And another thing? I heard this bakery makes really good apple pie, so I wanted to buy a slice of it, too.FEMALE PROFESSOR: OK.MALE STUDENT: There was a little label that said “apple pie,” where it's supposed to be, but there wasn’t any left.FEMALE PROFESSOR: And that's what's called a service gap. Maybe there wasn't enough training for the employees, or maybe they just ran out of pie that day. But something's wrong with the process, and the service standard wasn’t being met.MALE STUDENT: OK, I think I get it. Anyway, since part of the requirements for the term project is to visit an actual place of business, do you think I could use our cafeteria? They seem to have a lot of the things I'm looking for.FEMALE PROFESSOR: Well, campus businesses like the cafeteria or bookstore don't quite follow the kinds of service models we're studying in class. You should go to some other, local establishment, I'd say.MALE STUDENT: I see.FEMALE PROFESSOR: But just call the manager ahead of time so they aren't surprised.题目1.Why does the student go to see the professor?A. To find out all the requirements for a projectB. To discuss a service gap at a restaurantC. To get help understanding concepts relevant to his projectD. To get help with designing a business plan2.Why does the professor mention a student in another class?A. To describe an interesting topic for a projectB. To explain the cause of her initial confusionC. To point out that she has not received e-mails from all her students yetD. To indicate that she has several students doing projects about restaurants3.Why does the professor talk about the cafeteria on campus?A. To give an example of an effective service designB. To illustrate how service standards can inform service designC. To help the man understand a service problemD. To illustrate the concept of a service gap4.What do the speakers imply about the bakery the student went to recently? [Click on 2 answers.]A. The apple pie he bought there was not as good as it usually is.B. The bakery's service design was inefficient.C. The bakery needs additional employees to fix a service gap.D. The bakery did not meet a service standard.5.What does the professor say the student should do for his project?A. Compare an on-campus service model with an off-campus oneB. Interview the service manager and employees at the cafeteriaC. Recommend service improvements at the cafeteria and the bookstoreD. Analyze the service design of a nearby restaurant答案C B A BD D译文旁白:下面听一段学生和商务课教授间的对话。

辽宁省五校2025届高三六校第一次联考英语试卷考生须知:1.全卷分选择题和非选择题两部分,全部在答题纸上作答。

选择题必须用2B铅笔填涂;非选择题的答案必须用黑色字迹的钢笔或答字笔写在“答题纸”相应位置上。

2.请用黑色字迹的钢笔或答字笔在“答题纸”上先填写姓名和准考证号。

3.保持卡面清洁,不要折叠,不要弄破、弄皱,在草稿纸、试题卷上答题无效。

第一部分(共20小题,每小题1.5分,满分30分)1.After he was promoted to the present position, he is not so hardworking as he ______.A.was used to B.used to be C.was used to being D.used to2.______much pressure the U.S. government put on the Chinese government, China would stickto its own policy of exchange rate.A.However B.Wherever C.Whatever D.Whoever3.The course about Chinese food attracts over 100 students per year, _______ up to half are from overseas.A.in which B.of whomC.with which D.for whom4.________ a high percentage of Australians may be people who watch sports rather than do them, as far as most of its population is concerned, it is indeed a great sporting nation.A.While B.as C.If D.Whether5.Speaking a foreign language allows you to ________ time in a negotiation, for you can act like you have not understood to come up with your answer.A.save B.afford C.buy D.spend6.The bus would not have run into the river ________ for the bad tempered lady.A.if it were not B.had it not beenC.if it would not be D.should it not be7.There was also a wallet sitting inside the car with a lot of money ______.A.reaching out B.sticking out C.picking out8.In Australia, many road signs are now both in English and Chinese, ______ it easier for Chinese tourists to travel. A.making B.made C.make D.makes9.It really matters _______ he treated the latest failure, for the examination is around the corner.A.if B.thatC.why D.how10.His sister left home in 1998, and_________________ since.A.had not been heard of B.has not been heard ofC.had not heard of D.has not heard of11.I am sure that the girl you are going to meet is more beautiful_______ than in her pictures.A.in nature B.in movement C.in the flesh D.in the mood12.With more forests being destroyed, huge quantities of good earth ________ each year.A.is washing away B.is being washed awayC.are washing away D.are being washed away13.______me tomorrow and I’ll let you know the lab result.A.Calling B.Call C.To call D.Having called14.Keep up your spirits even if you _____ fail hundreds of times.A.must B.needC.may D.should15.Everybody was touched ______ words after they heard her moving story.A.without B.beyondC.against D.despite16.This car is important to our family. We would repair it at our expense _______ it break down within the first year. A.could B.wouldC.might D.should17.–E xcuse me, sir, didn’t you see the red light?–Sorry, my mind ________ somewhere else.A.has been wandering B.was wanderedC.was wandering D.has been wandered18.Jenny nearly missed the flight _________________doing too much shopping.A.as a result of B.on top ofC.in front of D.in need of19.— Did you catch the first bus this morning?—No. It had left the stop _________ I got there.A. in the time B.at the timeC.by the time D.during the time20.—Why did you come by taxi?—My car broke down last week and I still it repaired.A.didn’t have B.hadn’t hadC.haven’t had D.won’t have第二部分阅读理解(满分40分)阅读下列短文,从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中,选出最佳选项。