lecture7_alternatives_LA11_504608018

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:182.44 KB

- 文档页数:37

Unit 20 New Frontiers Lesson 1 Futurology一、课标分析根据《高中课程标准》的规定,在高二的学习中,学生要发展自己的英语语言运用能力:用英语进行恰当交流的能力;用英语获取信息、处理信息的能力。

在学习方法上,要逐渐形成有效的学习方法,在参与、实践、讨论和合作中学会用英语表达、交流,发展综合语言运用能力。

二、教材分析1.本课所在单元的主题为New Frontiers,主要介绍了跟我们生活与学习联系紧密的科学领域,并且介绍了20世纪科学领域的一些先驱者。

2.本节课为 Lesson 1 Futurology的第一课时,是一节阅读课。

该课的主要内容是未来学家就科学对未来影响做出的展望。

3.教材内容上的安排(对未来的预测),可以锻炼学生的抽象思维和创造性想象。

三、学生分析1.学生对未来学及未来的世界这一话题既感到陌生,但又显示出浓厚的兴趣和求知欲,从而带着好奇心去了解并探究。

2.学生对本课话题Futurology这一领域缺乏一定的背景知识、经历和经验,但高中学生已具备一定的相象能力和形象抽象思维能力。

3.高二的学生已具备一定的用英语获取信息、处理信息、分析问题和解决问题的能力。

四、教学目标1. 语言知识目标:a.重点词汇和短语seminar, handy, database, meanwhile, source, biochemistry, in terms of, wonder about, hundreds of, carry out, love doing/ to dob.重点句子1) Some like to read fantasy stories and imagine what the world will be like… Others foreseefuture opportunities and problems.2) Computers that are millions of times smarter than us will have been developed.3) In the next few years, we will be communicating with our friends around the world…4) We will have discovered other places in our solar system suitable for living and will havediscovered ways to go further into space.2.语言技能目标:1)学生学会在阅读中有目的地猜测、思考和获取信息,并进行分析、推理和判断,从而准确理解作者的意图。

Unit 20 New FrontiersLesson 1 Futurology一、教学课型:阅读课这是本单元第一篇阅读文章,它给学生提供了一个近距离感受科学技术迅猛发展的机会,让学生了解到什么是未来学和未来学家,从而鼓励学生积极、勇敢地面对人类社会所面临的经济、政治、文化等多方面的挑战。

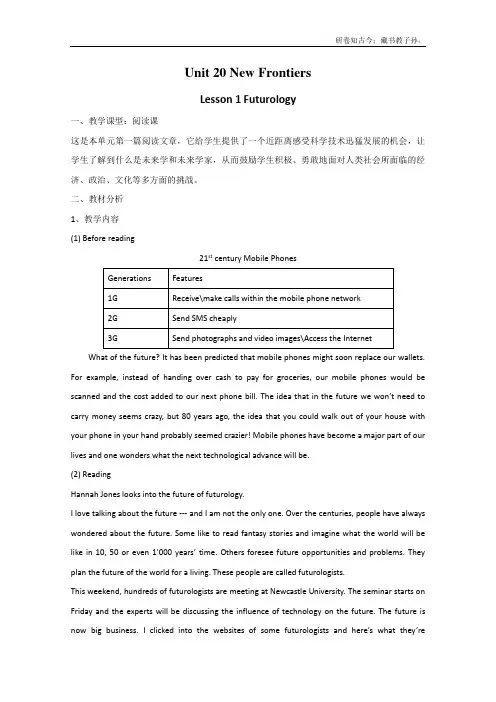

二、教材分析1、教学内容(1) Before reading21st century Mobile PhonesWhat of the future? It has been predicted that mobile phones might soon replace our wallets. For example, instead of handing over cash to pay for groceries, our mobile phones would be scanned and the cost added to our next phone bill. The idea that in the future we won’t need to carry money seems crazy, but 80 years ago, the idea that you could walk out of your house with your phone in your hand probably seemed crazier! Mobile phones have become a major part of our lives and one wonders what the next technological advance will be.(2) ReadingHannah Jones looks into the future of futurology.I love talking about the future --- and I am not the only one. Over the centuries, people have always wondered about the future. Some like to read fantasy stories and imagine what the world will be like in 10, 50 or even 1’000 years’ time. Others foresee future opportunities and problems. They plan the future of the world for a living. These people are called futurologists.This weekend, hundreds of futurologists are meeting at Newcastle University. The seminar starts on Friday and the experts will be discussing the influence of technology on the future. The future is now big business. I clicked into the websites of some futurologists and here’s what they’repredicting:·The technology already exists, so very soon all of us are going to use our voices to give instructions to computers. ·In the next few years, we will be communicating with our friends around the world using life-sized video screens in our living rooms.·By the year 2020, computers will already have become more handy and also more powerful than the human brain both in terms of intelligence and the amount of information they can store.·By the year 2030, development in biochemistry and medical science will make it theoretically possible for us to live for at least 150 years. Tiny, insect-like robots may be sent around our bodies to carry out repairs and keep us healthy.·By the middle of the century, computers that are millions of times smarter than us will have been developed. We will be linking our brains to these computers and a huge database. A new species might have developed!·By the end of the century, we will have discovered other places in our solar system suitable for living and will have discovered ways to go further into space.I’ll be there in Newcastle this weekend. At nine o’clock on Saturday morning, I’ll be sitting in the front row and l istening to the great Duke Willard talking about the future of my brain. If you can’t beat the future, join it!(3) Post-readinga) The Programme of the futurologists’ conferenceTell the statements T or F according to the information in the table. If false, correct it.( ) 1) At 5 p.m on Friday Prof Howard Green will be giving a lecture on alternative sources of energy.( ) 2) By Saturday lunchtime, they will be listening to two lectures.( ) 3) At 2.30 p.m on Saturday, everyone will have had lunch.( ) 4) On Sunday night, they will be having a reception.( ) 5) On Sunday morning, the participants will have identified a few problems of the future. ( ) 6) At noon on Sunday they will have attended the closing ceremony.b) Title: _____________________________ISRAEL: In our world's oceans, wind, waves and underwater currents spread dissolved air through the water. At a depth of 200m below the sea, there is still about 1.5% dissolved air. Fish gills work comfortably with this amount of air, and now Israeli inventor Alon Bodner has designed a way for man to do the same, eliminating the need for cumbersome oxygen tanks and expensive air compression units. If it goes to plan, a tankless underwater breathing system in the form of a vest that will be attached to a diver should be available in a few years time.(4) Homeworka) Match the vocabulary with the explanations.1)wonder about a. estimate in advance2)foresee b. survive or continue living with difficulty3)meet c. go into a website4)seminar d. get together5)click into e. (of things or places) convenient, useful6)predict f. feel curiosity7)exist g. know or see something in advance8)handy h. according to9)in terms of i. a group of animals or plants10)store j. collect and keep for future use11)carry out k. a meeting where students discussing a topic with teachers12)link… to… l. connect… to…13)species m. finish doing somethingb) Complete the sentences with the correct form of the words given.1) A toolbox will be very _________ if you have got one at home.2) Scientists are __________ research into using spiders’ cobwebs to produce tiny wire.3) I was ___________ why he did this.4) There is no one who can ________ or __________ what the human future will be.5) Many people __________ in front of the City Government Building yesterday.6) Nowadays if you ___________ the websites of some famous writers, you can read their works.7) It is said that computers will be more powerful than the human brain ________intelligence.8) Many animals like squirrels will ________ food for future use.9) In some slowly developing districts, there are no roads ________ the city _______ villages.10) We call for middle school students to read more books _________ for their ages and health.c) Read more information about “the Future” and do exercises.1) By the time you get home I ________________________________________.你到家之前我将把房子彻底打扫了一遍。

雅思写作万能高分词汇之alternativealternative绝对是一个万能单词,可作形容词,表示“另外的,其他的,可用来替换的”,也可以作名词,表示“另一个选择”。

比如:Im awfully sorry,meres no alternative but to sell me car.真的很抱歉,我没有其他办法只能卖汽车了。

Everyone will accept computers,because there is no alternative.我们都会接受电脑,因为别无选择。

Competitive success is commonly seen as the American alternative to social rank based on family background.在美国,在竞争中胜出常被看作可以替代基于家庭背景的社会地位。

在《剑桥雅思》一篇关于“开车优劣势”的高分范文中有这么一句:Long-distance train and coach services should be made attractive and afrordablealternatives to driving your own cars for long journeys.本句中的alternative用作名词,全句的意思为:应该让长途火车和客车既有吸引力,价格又便宜,在长距离旅行中来替代自驾。

以下看出现在老雅范文中的alternative。

In conclusion,there are reasons why countries should reduce their consumption of fossil fuels such as oil,coal and natural gas,but more realistically,they should find ways of generating and storing alternativesources such as solar and wind energy.总之,各国应该减少石油、煤炭和天然气等化石燃料的消耗是有原因的,但更現实的是,它们应该找到方法来生产和储存替代能源,如太阳能和风能。

Alternative⼀词从词典释义来看不难明了,但是在使⽤和翻译时,必须注意与它搭配使⽤的限定词和介词以及上下⽂,否则就有可能导致误⽤或误译。

例如在表达“另⼀种可采⽤的⽅法”时,如⽤alternative,前⾯不能加限定词another,因为alternative ⼀词原义就指“⼆者选⼀”、“⼆者之⼀”,已含有“另⼀个”的意思,引申后恰好可以表⽰“另⼀种(可供选⽤)⽅法”,所以只需说an alternative或the alternative就可以了。

⼜如He has no alternative⼀句,初学者往往根据alternative的“可采⽤的⽅法”这⼀释义⽽译成“他没有可采⽤的⽅法”或“他⼀筹莫展”,殊不知alternative在这⼀句的含义是“另⼀种可采⽤的⽅法”,所以句⼦应译为“他没有选择的余地”或“他别⽆良策”。

⼀般说来,名词alternative可以有下⾯四种含义,除第⼀种含义外都适⽤于“形容词 alternative+名词”。

其汉译则因上下⽂⽽异。

⼀、表⽰对两个或两个以上办法(或⽅案等)的选择Alternative前⼀般⽤the或the only, alternative⽤单数。

alternative 后可以接of,引出可供选择的对象,各对象⽤or连接。

这⼀含义不适⽤于“形容词alternative+名词”。

例如:1,We have the alternatives of coffee, tea, or water. 我们可以选喝咖啡、茶或开⽔。

2,Should a motorway pass under or over a large waterway? Up till about 1960 the only alternative was bridging over or tunnelling under the waterway.公路应该从江河的下⽅还是上⽅通过?直到1960年左右所能选择的⽅案只是⽔上架桥法或⽔下开凿隧道法。

![英语单词精解系列[高中人教选修8单元5]七十八](https://uimg.taocdn.com/bd67f988e45c3b3567ec8bcf.webp)

英语单词精解系列[高中人教选修8单元5]七十八alternative音标_________________________________________________________________________________ 英[o:l z t3:n9tiv; ol-]美[□Kta-nativ]释义_________________________________________________________________________________ adj.供选择的;选择性的:交替的n.二中择一:供替代的选择短语_________________________________________________________________________________ Alternative education:另类教育;选择性教ff;选替教育Alternative science:类科学;另类科学;另一种科学Alternative Rap:另类说唱;说唱乐;另类说唱乐;另类弹词说唱alternative currency:替代货币alternative uses:改换用途地使用;多种用途;为它找个替身;选择使用Alternative Girls:替代女友;交替少女;交换少女潜身少女alternative proposals:替代方案;替代方案备选方案;备选方案;被选建议书alternative conception:有概念;相异概念;相异构想;另有想法alternative feeder:交替喂纱导纱器例句_________________________________________________________________________________1.N-COUNT If one thing is an alternative to another, the first can be found, used, or done instead of the second. 替代品2.ADJ An alternative plan or offer is different from the one that you already have, and can be done or used instead.另外的[ADJ n]例:There were alternative methods of travel available.有另外的旅行方式可采用。

2018届高考英语一轮单元总复习讲义精品荟萃外研版必修四Module 1知识详解1 alternative adj. 替换的;供选择的n.可供选择的事物(回归课本P2>alternative energy 可替代能源归纳总结例句探源①Try to arrange play dates for the children as an alternative to TV viewing.b5E2RGbCAP设法给孩子们安排做游戏的时间,来代替看电视。

②(牛津P56>Do you have an alternative solution?你有没有别的解决办法?③(朗文P57>I had no alternative but to report him to the police.除了向警察举报他,我别无选择。

p1EanqFDPw④As natural resources are limited on earth,we will have to use alternative energy.DXDiTa9E3d由于地球上的自然资源是有限的,我们将必须运用可替代性能源。

即境活用1.(高考湖北卷>As there is less and less coal and oil,scientists are exploring new ways of making useof________energy,such as sunlight,wind and water for power and fuel.RTCrpUDGiTA.primary B.alternativeC.instant D.unique解读:选B。

句意是:由于煤和石油越来越少,科学家正在开发新的利用可替代能源的方法,比如利用阳光、风和水来发电和做燃料。

根据句意可知此处要用alternative表示“可替代的”。

primary主要的;instant立即的;unique独特的。

Unit 7 CareersLesson 2 Career Skills学习目标1. 掌握本节生词、短语及句型的表达与运用。

2. 通过练习,对本节课的内容有更深入的了解。

知识运用1. response词性:____________ 意思:_____________in response to 作出对……的反应/回答make a quick response to 对……作出快速反应make no response 没有回答respond to 对……作出反应;回答,回复respond with 以……作为回答respond to sb. by doing sth. 用做某事来回答某人/ 作出反应练习:I knocked on the door but there was no _________.2. apply词性:____________ 意思:_____________apply to sb. for sth. 向某人申请某物apply to do sth. 申请做某事apply…to… 把……应用到……apply oneself to 致力于…….application n. 申请;应用applied adj. 应用的applicant n. 申请人练习:I decided to _________ my previous experience to learning English.3. alternative词性:____________ 意思:_____________have no alternative but to do sth. 别无选择只能做某事an alternative to… ……的另一种选择an alternative lifestyle 另类的生活方式alternative energy 替代能源alternatively adv.(引出第二种选择或可能的建议)要不,或者练习:There were so many cars that we had no _________ but to wait.4. guarantee词性:____________ 意思:_____________be guaranteed to do sth. 必定会做某事guarantee to do sth. 保证做某事guarantee sb. sth. 向某人保证某事guarantee that... 保证……give sb. a guarantee that... 向某人保证……under guarantee在保修期内练习:Most states _________ the right to free and adequate education.5. focus on意思:_____________focus one's attention/ mind on… 集中注意力/ 心思于……focus one's eyes on… 注视……focus the camera on… 把照相机的镜头对准……练习:You'd better _________ your attention _________ your study.6. lead to意思:_____________lead to failure 导致失败lead to success 通向成功lead to being caught 导致被抓lead sb.to do sth. 导致某人做某事练习:Eating too much sugar can _________ health problems.7. come up with意思:_____________put up with 容忍,忍受catch up with 追得上,赶得上keep up with 跟得上end up with 结束,以……结束,以……告终练习:Although against my opinion, the old professor didn't ________________ his own.听力探究Listen again. Answer the questions.1 What is Kristy's purpose of visiting Mr McDougall?2 Does Mr McDougall know what jobs Kristy will do in the future? Why?3 What is Mr McDougall's prediction for future jobs?4 What do teenagers need to prepare for future jobs according to Mr McDougall?句型梳理1.(教材P105)Well, first, you need to have the ability to learn new skills.首先,你需要有学习新技能的能力。

Alternative approachesto language acquisitionLanguage Acquisition80640272Yang XiaoluReadings for this week*Goldberg, A. 2003. Constructions: a new theoretical approach to language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 7(5):219-224.Lieven, E., Pine, J., and Baldwin, G. 1997. Lexically-based learning and early grammatical development. Journal of Child Language24:187-219.*Tomasello, M. 2000. Do young children have adult syntactic competence? Cognition, 74, 209-253.*Tomasello, M. and Brooks, P. J. 1998. Young children’s earliest transitive and intransitive constructions. Cognitive Linguistics9(4):379-395.the Chomskyan view of languageacquisitionmentalismthe logical problem of language acquisitionuniversal grammarmodularityInnatenessthe debate between nativism vs. empiricism; generative linguistics vs. cognitive-functional linguisticsCommon ground between generativelinguistics and cognitive functional linguistics (Goldberg 2003)Language is a cognitive (mental) system: (as opposed to the behaviorist view of language) Structures are combined in a certain way to create novel utterances.A non-trivial theory of language learning is needed.Some basic concepts in the debatecore vs. peripherymodular vs. non-modulardomain-specificity vs. domain-generalityautonomy vs. interactionrule-based learning vs. item-based/lexically-based learning/usage-based-complexity-productivity“In other ways, constructionist approaches contrast sharply with the mainstream generative approach. The latter has held that the nature of language can best be revealed by studying formal structures independently of their semantic or discourse functions. Ever increasing layers of abstractness have characterized the formal representations. Meaning is claimed to derive from the mental dictionary of words, with functional differences between formal patterns being largely ignored. Semiregular patterns and unusual patterns are viewed as ‘peripheral,’with a narrow band of data seen as relevant to the ‘core’of language. Mainstream generative theory argues further that the complexity of core language cannot be learned inductively by general cognitive mechanisms and therefore learners must be hard-wired with principles that are specific to language (‘universal grammar’).”(Goldberg 2003:219)Explaining language acquisition in terms of general cognitive principlesMcNamara 1972 “Cognitive basis of language learning in infants”Slobin1973 “Cognitive prerequisites for the development of grammar”Tomasello2000 The Cultural Origins of Human CognitionLanguage is interactive: language development is not simply a development of mental grammar internalized by the child, but is a product of complex interactions of linguistic, cognitive, perceptual systems with the environment.Cognitive development precedes linguistic development. The child uses the cognitive ability s/he has developed (e.g. the ability to detect intentional behavior in others, the capacity for joint attention and reference, understanding of the structure of action in social interaction, understanding of the speech acts of others), as well as other cognitive principles and mechanisms, as guides to discovering the linguistic system of the target language.Explaining language acquisition in terms of general cognitive principles: connectionism Elman, J. et al. 1996. Rethinking Innateness: A Connectionist Perspective on Development.Elman, J. (2001). Connectionism and language acquisition. In M. Tomasello& E. Bates (Eds.), Essential Readings in Language Development. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.Bates, E. Elman, J., Johnson, M., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Parisi, D., & Plunkett, K. (1998). Innateness and emergentism. In W. Bechtel and G. Graham (Eds.) A Companion to Cognitive Science.Oxford: Basil Blackwood.cf. 李平, 2002, 《当代语言学》2002年第3期Language is not domain-specific and is processed by general mechanisms. Such mechanisms are connectionist networks that consist of numerous simple units.Language is analyzed through continuous connectionist computation and is distributed across neural systems. Linguistic competence can be obtained without innate linguistic rules.Language learning is not a process of deriving complex structures from more primitive or innate ones. Rather, new forms or structures emerge all the time in an unpredictable way in response to the linguistic input.Figure 1: A neural network that reads letters and recognizes words. When a letter is detected, the corresponding letter node activates all words that contain it (lines with arrows). Since only one word can be present at a time, word nodes compete with inhibitory connections (lines with filled circles).Accounting for early grammatical development: from two-word combinations tomulti-word combinationsAndrew’s Pivotal constructions(Braine 1963)airplane by siren by mail come mama come clock on there up on there milk in there light up thereother bread other milk other pants other part other piece other pocket other shoe boot off light offmore car more cereal more fish more high more hot more juice more walk hi Calico hi mamano bed no down no fix no home no mama no more no pee see baby see trainall broke all buttoned all clean all done all dry all fix all messy all shut all through all wetthe pivot grammarBraine (1963) The Ontogeny of English Phrase Structure: the First Phrasetwo word classes at this stage: pivot and openthe pivotal class: never stands alone and always occurs either in first position and final positiona three-rule pivot grammar1) P1 + O;2) O + P2;3) O + O (e.g ball table, mommy sock…)The semantic relations approachBrown (1973) A First Language: the Early StagesSemantic relations-recurrence (more)-location (up there, in there)-possession,-agent-actionThe child knows some things about the causal relations among agents, actions, and objects, and this knowledge might form the basis for structures like agent-action-object (and also for possessor-possessed, object-location, object-attribute, and so on)Problems with the pivot grammar and the semantic relations approachFail to account for all early word combinations Fail to account for how young children get frompivot grammar or semantically based categories to the more abstract syntactic categories of adultsthe nativist view of early syntaxthe Continuity Hypothesis“In the absence of compelling evidence to the contrary, the child’s grammatical rules should be drawn from the same basic rule types, and be composed of primitive symbols from the same class, as the grammatical rules attributed to adults in standard linguistic investigations.”(Pinker 1984:7)“Children’s developing grammars can differ from the target, the adult grammar, only in ways in which adult grammars can differ from each other.”(Crain and Thornton 1998:31)problems with the nativist viewFails to deal with the problems of cross-linguistic variation and developmental change:-how children could “link”an abstract and unchanging universal grammar to the structures of a particular language.Fails to give a satisfactory account of why children’s early language looks very little like adult language.the nativist view: why early child grammar different from adult grammarPerformance and pragmatic limitationscf. Valian’s(1991) account of early null subjectsMaturation-certain aspects of grammar ‘mature’-time constraintLexicalism-grammatical categories and rules attached to lexical entries-interaction between grammar and lexiconTomasello(1992, 2000a, b, 2003)The usage-based accountitem-based learningGeneral cognitive processes involved in language learning-intention reading and cultural learning-analogy making and structure-mapping-structure combiningthe usage-based approach-intention reading and social learning“…a large part of language acquisition must be accomplished by means of some form of social or imitative learning.”(Tomasello2000:238)InputImitationContexts: daily routinesthe usage-based approachAnalogy making and structure-mapping“…human beings are capable of discerning similarities not only among objects on the basis of perceptual or functional features, but also among relational and event situations on a basis of acommon relational structure abstracted across particular objects involved.”(2000:241)-the function of a structure is as important as its form-salient intentional, causal, or spatial relations acquired earlier: early sentences revolve around these relationse.g. transitive verbs like give, tell, show, send,all have a ‘transfer’meaning and occur in NP+V+NP+NPthe usage-based approach-item-based learning“…the child initially learns individual, item-based linguistic constructions…upon comprehension and production of specific items on specific occasions of use.”(Tomasello2000:237-38) “…young children do not yet possess abstract and verb-general argument structure constructions into which different verbs may be substituted for one another as needed, but rather they areworking more concretely with verbs as individual lexical items whose syntactic behavior must be learned one by one.”((2000a:210-11)the Verb Island Hypothesis (Tomasello1992)Different verbs develop along different paths. Verbs operate as “individual islands of organization.”(1992:257)the usage-based approach-structure combining“Children learn various kinds of constructions from early in development-varying in both complexity and abstractness-and so when they want to express some new meaning, one thing they can do is to juxtapose or integrate those existing structures in some way.”(Tomasello2000:245)symbolic integration (Tomasello1992)A diary study of an English-speaking girl’s (T) verbs during theperiod from 16 months to 24 months of ageSymbolic integration(Tomasello1992)“From the point of view of Cognitive Linguistics, constructing a sentence is an act performed by a particular person speaking a particular language on a particular occasion for a particular purpose. The mental operation involved in this process are the same as those used in other domains of creative activity, although the material worked with –the structures and categories involved –are obviously unique to language. The mental operations used in sentence construction are referred to as processes of symbolic integration.”(p.226)Symbolic integration(Tomasello1992)“…cognitive processes involved in language acquisition are symbolic integration operations, that is, the operations used toproduce, and perhaps to comprehend, larger structures in which items from the inventory (including categories) are combined and coordinated into sentences. In the simplest cases, these are fairly straightforward mental combinations, concatenating two words, for example. Established structures with their own internalcomplexity can also be conjoined, usually in ways that preserve the previous ordering patterns of elements within the constituent structure. Most complexity is added when the coordinationamong established structures involves substituting one to another in some way.”(p.259-60)Symbolic integration: Tomasello(1992) How T constructs “See Daddy’s car”?See _____See MariaSee DaddySee thisSee Daddy’s carDaddy’s _____Daddy’s breadDaddy’s ballDaddy’s saladSymbolic integration: Tomasello (1992) operations involved in symbolic integration in T’s dataSubstitution Expansion Addition Coordination Close this door Close this window previous use new use⇒Read paper Read this book ⇒Read this book outsideRead this book Cereal down rug __down +Down __⇒⇒Evidence for the item-based learningObservational studies: spontaneous production Experimental studies: controlled experiments the age range of subjects: before 3 years of ageEvidence for the item-based learning:Tomasello(1992)“…T composed her more complex sentences using materials she had previously used in less complex sentences.”(p.234)“…roughly 92% of T’s first 271 three-or-more-word sentences involved only a single simple change from previous sentences with that same verb.”(p.236)“In almost all cases, the ordering within the two constituents (e.g. see ___ and Daddy’s ____ )is preserved.”(p.237)Lieven et al. (1997)11 English-speaking children’s production of multi-word combinations; children observed 1;0 to 3;0Pronoun use (case-marking)\Randomly using me/my and I in subject positionVerb argument structures\the first 20 utterances with a subject-verb-objectstructure\No distinction between prototypical and non-prototypical verb structures“The children's early utterances with two arguments and a verb were as often nonprototypical as prototypical and seemed to have developed from previous verb and direct object patterns, based around speci®c verbs like do, get, want, see and make which ful®lled the criteria of constructed positional patterns in our coding scheme. Again the basis of organization and development seems to be more related to speci®c lexical items than to any more generally underlying systematicities.”(Lieven et al., p.208)“Many of the children in the present study had groups of utterances united by wh-frames such as wheres x and whats x doing, and structures such as its x, its a x, theres a x and theres the x but our approach would suggest that we are not likely to ®nd that individual children have a fully ¯exible grasp of whquestions or of copula construction. Instead, they are building up utterances around one particular frame while ignoring others which, on the grounds of syntactic theory, ought to be related.”(Lieven et al 1997, p.209)Tomasello&Brooks (1998)Verb-specificity and verb-generalitySubjects: 16 children at 2.0 and 16 children at 2.5Methodology-Novel verbs used MEEK, TAM to describe a novel action-the meeking situation: involving a puppet pulling a small object upa ramp; meek was used to describe either the action of the puppetor the action of the object moving up-the tamming situation: involving a puppet pushing a small object, causing it to swing back and forth-the transitive and intransitive contexts-Test sentences:The puppy is meeking the ball. /The ball is meeking.The bear tammed the carrot./ The carrot is tamming.ProcedureThe child is exposed to one verb in a transitive context and the other one in an intransitive context.Questions raised to the child:‘What is going to happen now’‘What’s happening with the (patient)?’‘What is the (actor) doing?’ResultsThe researchers found that 2-year-old children who heard a transitive or intransitive novel verb only used the verb in the way as they heard it used: i.e. when children heard an intransitive verb, they only reproduced a similar intransitive utterance, even when they were encouraged to produce a transitive utterance.Verb-specificity is supported.Next week:The Development of Words and Word Meanings*Barrett, M. 1995. Early lexical development. In P. Fletcher and B. MacWhinney(eds.), The Handbook of Child Language. Cambridge, MA.: Blackwell.*Golinkoff, M, Mervis, C., and Hirsh-Pasek, K. 1994. Early object labels: the case for a developmental lexical principles framework. Journal of Child Language21:125-155. (photocopy)*Tardiff, T. 1996. Nouns are not always learned before verbs: evidence from Mandarin speakers' early vocabularies. Developmental Psychology32:492-504. (E-copy)。