S&T-vs-IBD-Part-2-On-the-Job

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:86.76 KB

- 文档页数:24

s发/s/的读音规则一、s在词首时;除了sugar;sure以及sh组合发/ /以外;其余一般发/s/.. 例:surface;serve;seven;six;some;sign比较:design/di'zain/一般前缀;合成词不影响其读音..s仍读成/s/..例:unsafe;unsatisfactory;roadside;teaspoon;snowstorm二、两个s在词尾时读作/s/.. 例:grass;glass;address;press;success;pass;miss;stress;across;swiss; progress;process;kiss三、词尾s在u后读作/s/.. 例:bus;us;minus;abacus;plus;status;virus四、在sis组合的弱读中;两个s都读作/s/.. 例:emphasis;analysis;thesis;crisisemphasise; emphasize; analyse/ analyze; criticise/criticize criticism n.五、s在字母c前常读作/s/.. 例:muscle;discipline;science六、s在某些前后缀中读作/s/..1.在前缀mis-;dis-中;s读作/s/.. 例:mismanage;misjudge; misbelieve;disorder;disobey2.在后缀-sive;sity;-self;-some;-sy中;s读作/s/.. 例:expensive;intensive;decisive;yourself;handsome;troublesome;tiresome;quarrelsome七、s在清辅音前后常读作/s/..1.s在清辅音前常读作/s/.. 例:honest;newspaper;task;satisfy;grasp grab; grip2.s在清辅音后常读作/s/.. 例:sportsman;works;stops;roofs.八、词尾se在字母r;l;n后读作/s/.. 例:horse;nurse;worse;course; universe;pulse;else;tense;senseI couldn't find good references by Googling; and I don't know anything about British English. As I think it through; it is quite complicated Sorry -- we should really get around to some spelling reform. I hope others can help edit this list if they think of exceptions.In American English; typicallyIf there are any prefixes or suffixes causing an s to be in the middle of a word either because the "s" is part of the prefix or because it is part of the root"; the "s" is always unvoiced 清音/s/; e.g. subsist; substandard; mismatch; mistake; etc.An s that is written next to an unvoiced consonant 清辅音 is always unvoiced /s/; e.g. lisp; rasp; history; etc.When the unvoiced consonant of the above rule is t; then the /t/ is silent if the next syllable is syllabic /n/ or /l/:listen; whistle. Otherwise it is pronounced. See the comments for a more detailed description of this rule.An s before m is always voiced /z/: chasm; prism; plasma. However; the top rule takes precedence有优先权; so the s in mismatch is always voiceless /s/.An s that is written doubled between vowels is also unvoiced: massive; missive; missile; etc. However; if the s would occur in the phonetic stream /s+j/ then it assimilates to / /; e.g. in mission.An s that is written as one single letter between vowels is usually /z/;e.g. laser; risible; criticise/ criticize; desert; design; reason; busy; result; reserve; closer the comparative form of the adjective "close"; has an /s/ sound. In the same environment as mentioned above /z+j/ will assimilate to / / e.g. in vision.Terrible exception to the above: in dessert; the s is voiced to /z/. Many native English speakers misspell dessert for this reason. Note also that the difference between desert and dessertis not voicing; but which syllable gets the accent it is the first in desert and the second in dessert.Possess and its derivatives are another exception; the middle "ss" is voiced to /z/. The terminating "ss" is not.Other miscellaneous exceptions: The -ss- in the American state name Missouri is also exceptionally pronounced /z/. In raspberry;the p is silent and the s assimilates to the /b/; so is voiced to /z/.补充:Based on the immediately surrounding letters:Word-internal -ns-; e.g. in i ns ist; te ns e; ti ns el; is almost always pronounced /ns/ with unvoiced /s/. This doesn't apply to words that end in -ns; like pe ns or le ns these have /nz/.Exceptions:clea ns e and pa ns y; which have /nz/. For somespeakers; certain but not necessarily all words starting with "trans" such as tra ns it and tra ns ition have /nz/.Word-internal -ls-; e.g. in el s e; pul s e; is almost always pronounced /ls/ with unvoiced /s/. This doesn't apply to words that end in -ls; like ee ls or stea ls these have /lz/. Exception: pa ls y; which has /lz/.Word-internal -rs-; e.g. in pe rs ist; ve rs e; is almost always pronounced /rs/ with unvoiced /s/. This doesn't apply to words that end in -rs; like sta rs or you rs these have /rz/.Based on identifying particular suffixes:The ending -sive is usually pronounced /s v/ with voiceless /s/; even when there is a vowel letter immediately preceding the letter "s". For example; explo s ive; inva s ive; abu s ive; deri s ive are all pronounced with /s/.The ending -o s ity is always pronounced with voiceless /s/.名词复数后面s的发音规则一般来说;s在元音或浊辅音后读z};在清辅音后面读成s;在t后与t在一起读成ts;在d后与d一起读成dz..cups 杯子 days 日子 hands 手 hats 帽子2、以s;sh;ch;x结尾的词在词尾加-es;读izclasses 班级 buses 公共汽车 boxes 盒子 watches 手表3、以“元音字母+y”结尾的词;加-s;读作z;以辅音字母+y结尾的词;变y为i;再加-es;读iz..boy-boys 男孩 army-armies 军队 story-stories 故事factory-factories 工厂 baby-babies 宝贝4、以o结尾的词;多数加-s;读z..kilo-kilos 公里 photo-photos 照片 tobacco-tobaccos 烟草piano-pianos 钢琴以元音字母+o结尾的词一律加-s;读z..zoo-zoos 动物园 radio-radios 收音机少数以o结尾的词;在词尾加-es;读z..tomato-tomatoes 西红柿 hero-heroes 英雄 Negro-Negroes 黑人potato-potatoes 土豆5、以f或fe结尾的词;多数把f;fe变为v;再加-es;读s..leaf-leaves 树叶 thief-thieves 小偷 wife-wives 妻子knife-knives 小刀 shelf-shelves 架子6、不规则名词的复数形式..1、通过变化单词内部元音字母;构成复杂形式..man-men 男子 woman-women 女人 foot-feet 脚 goose-geese 鹅tooth-teeth 牙齿 mouse-mice 老鼠 child-children 小孩2、单数形式与复数形式相同sheep-sheep 绵羊 deer-deer 鹿 Chinese-Chinese 中国人Japanese-Japanese 日本人规则的名词复数形式一般是在单词后加-s 或-es..其音法方法为:在/p/ /t/ /k/ /f/等清辅音后 /s/Cups; hats; cakes; roofs在/s/ /z/ /M/ /CM/ /DN/等音后 /iz/glasses; roses; brushes; matches; bridges在其它情况下:/z/Beds; days; cities; knives以th收尾的词原读/θ/的;加词尾s后;多读/z/;例如:mouth mouthspath /pa:θz/- paths /pa:Iz/但也有不这样变的;如:month /mΛnθ/ - months /mΛnθs/; length/lengθ/ - lengths/leng θs/;另有些词可变可不变;如:youth/ju:θ/ - youths/ju:θs/或/ju: θz/; truth/tru:θ/ -truths/tru:θs/或/tru: θz/..关于名词复数后面s的发音规则;我相信你已经看过了多遍语法书上名词复数后面的三条发音规则了;只是看不懂;也不会用..要掌握这些复杂难懂的规则;关键是要知道其背后的用意;从而不被表面的文字所迷惑..下面请你睁大双眼;我告诉你它们的真实用意——其实就是为了两个字“顺口”..没明白吗;稍微解释两句..s为什么可发s和z两个音呢;就为了顺口;这两个音一个弱一个强;一个无声一个有声也就是过去所说的;前一个是清辅音;后一个是浊辅音;那么这两个音怎么用呢很简单;遇到单词尾是不响亮的清辅音字母时如p;t;k;f就发s;遇到单词尾是响亮的浊辅音字母如b;d;m;n;r或元音字母如a;e;o;u时就发z;这样做的目的就是为了顺口..清辅音发音时仅气流从嘴里出来;声带不振动;发出的声音较弱;因此英语里认为清辅音是一种不响亮音;而浊辅音和元音发音时声带要振动;发出的声音大;因此英语里认为浊辅音和元音是响亮音..为了追求发音的顺口和协调;英语人民普遍有一个发音倾向;并且大家都在自觉地执行;就是让清辅音和清辅音连在一起如ps;ts;ks;fs;让响亮音和响亮音连在一起如bz; dz;mz; nz; rz; az;他们认为这样发音很顺口协调..在他们看来;要是让一个清辅音和一个浊辅音连在一块;比如fz;kz;pz;tz; 就好像让一个哑巴和一个大叫驴站在一块;怎么看都别扭;不顺口;不舒服..因此英语人民在发名词复数后面s音时就自发自动地出现了的两个现象也就是上面的第一条和第三条:1s在p;t;k;f等清辅音后发s;3在其他情况下即在浊辅音和元音后发z..怎么样;这回你明白了吗;要是没明白的话;别急着往下看;翻回头去再看几遍我上面说的话;直到彻底搞明白了再往下看..我向你保证;以上内容绝对十分简单;只是你过去学英语“复杂”惯了;猛然碰到个简单的;一时半会还转型不过来..等你看明白了上面的话语;我再接着讲..英语里有一些特别讨厌的单词;它们以s;z; sh; ch为结尾;比如单词bus; fox; dish; watch;等;这些单词的结尾音有一个一致的特点;就是和s的发音一样或特别接近;这使得若在这些单词的后面直接加个s来表达复数的话;成为buss; foxs; dishs; watchs的话;单词结尾的发音就出现了难题;因为区分两个一样或十分相近的s音十分困难;不信你念念上面单词;看你的嘴能否区分开..怎样来解决这个难题呢英语人民还真很智慧;他们不知道是谁带了头;想了一个办法来对付这个难题;就是在两个s之间塞个e;变成buses; foxes; dishes; watches;并且让e发音为i;这样一来不就把两个相似的s的发音间隔开了吗妙妙妙看来全世界群众的眼睛都是雪亮的..那么buses; foxes; dishes; watches最后的那个s该怎么发音呢这回该问你了;你不是看懂了我前面说的那段话了吗;里面有“响亮音要和响亮音连在一起”..e是个什么音是元音;元音属声带振动的“响亮音”;并且e在这里发i;那么它后面跟个s该怎么发音;这还用说吗;肯定是顺口协调地与e一同发响亮的z了..因此要是让我来修改上述三条规则;首先就是取消第二条;取消这个像烟雾弹一样的多余规则;都是它把问题搞乱了;这条多余的规则使整个规则的讲解都出现了逻辑上的混乱;就好像告诉别人“人类社会是由人类和大人小孩组成的”;这话谁能听得懂取消第二条后我把上述三条规则改写成如下两条:名词复数后的s1S在清辅音后发s2S在浊辅音或元音后发z..如果你还能进一步看得明白;看得觉醒;我就索性将它再改一改;改成一步到位的、谁都能一眼看得明白记得住的下面两句话: 1S在不响亮音后发s2S在响亮音后发z..。

s'的用法

“s”是代词,也是第三人称单数。

当主语是第三人称单数,或搭配with和不定冠词时,可以使用s“。

“s”的用法主要有以下几称:

一、用于人名后面

一般来说,我们使用第三人称单数时,都会在人名后加上“s”,表示这个人所拥有

的东西。

例如,“John’s office”表示约翰的办公室;“Alice’s house”表示爱丽丝

的房子。

二、用于及物动词后面

当我们使用及物动词描述一件事时,我们通常会在动词后添加一个“s”,表示动作

是针对某个人,某个组织或某个物体。

例如,“She cleans her room every day.”表示

每天她都会打扫她的房间。

我们在表述某个名词所拥有的东西时,也可以在后面加上“s”,例如“a book’s cover”表示某本书的封面。

四、用于搭配with和不定冠词时

当我们搭配with和不定冠词时,也可以加上“s”。

例如,“She goes to the shop with her fri ends.”表示她和朋友一起去商店。

总之,“s”作为第三人称单数,主要用于表示某人所拥有的东西,以及描述某个人、某个组织或某件物体所做的动作等用法,在日常英语学习中十分常见。

目前应用最广泛、输出效果更好的S端子接口。

S-Video端子又称亮色分离端子,是一种专业视频标准接口,只传输视频信号,与音频无关。

S并不是Super,而是Separate,是分离的意思,将视频信号的色度信号C 和亮度信号Y进行分离,分别以不同的通道进行传输,减少影像传输过程中的“分离”、“合成”的过程,减少转化过程中的损失,同时降低信号之间的互扰,减轻视频节目输出时亮度和色度相互干扰的问题,以得到更佳的显示效果。

S-Video端子输出接口支持设备的最大显示分辨率为1024 x768。

目前市场上常见的S端子有三种:4针、7针和9针。

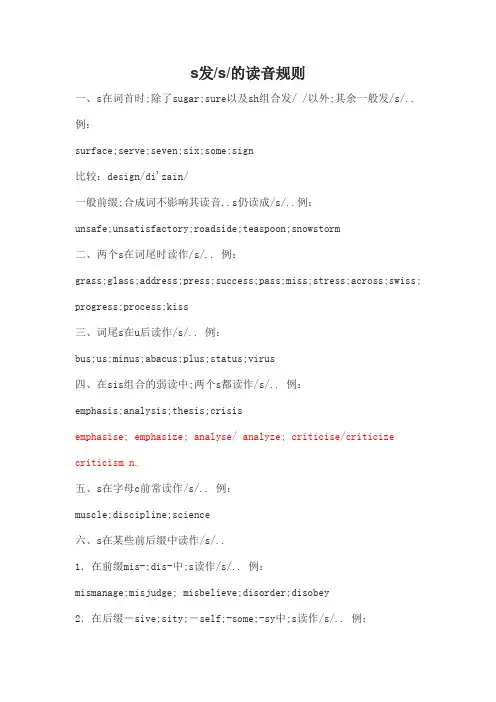

1、4针S-Video接口4针是常见的S-Video端子,目前的电视机、影碟机、投影仪配接的都是4针接口,较早一些的显卡如MX440,FX5200等配置的也是4针的S-Video。

S端子线为单根多芯结构,长度一般在3M之内,最长不能超过5M,否则有可能出现显示画面黑白或者是无信号输出的状况。

实际上视频信号的传输主要取决于传输线的质量,如果主观能够接受不易觉察的图像质量下降并使用高品质信号线,信号的传输距离可以达到30米;如果使用两根信号线传输(在S端子接口处汇合)的高品质75ohm同轴电缆(如RG59 or RG6),传输距离甚至可以达到60-100米。

2、7针S-Video接口标准的7针S-Video比较4针的多出了一路复合信号,可以单独分离输出RCA信号(复合信号),在显卡上就可以省去一个黄色的VIDEO输出接口。

虽然多出的2针功能和定义各不相同,但一般都是把这两针作为标准AV视频信号输出,这样就使得这个7针接口即能分离出一路4针标准S端子信号,又能分离出一路标准的AV视频信号。

有的配备7针S端子的显卡配备一个一转二的转接输出装置,可以分成S端子和AV输出两种模式。

不过,7针的S-Video接口可以直接使用4针S端子线,不必另行购买连接线。

另外,还有部分显卡自带的7针S-Video能够提供色差输出,其针脚的定义有别于上述标准,定义如下:3、9针接口9针的S端子接口针脚定义比较标准较多,一般为两种:一种是为其中4针是标准S端子,2针是标准AV视频信号输出,余下2针是音频信号输出。

s的所有用法

1. “S 可以用来表示复数呀,就像“apples”表示好多苹果一样。

哎呀,你想想,要是没有这个“S”,那说苹果得多费劲呀!

2. S 还能在一些动词后表示第三人称单数呢,比如说“He likes music”里的“likes”。

这不就简单明了地表明是“他”喜欢音乐嘛,多直接呀!

3. 嘿,S 在一些缩写里也有它的身影呢!像“is”缩写成“’s”,“that is”不就可以写成“that’s”嘛,多方便!

4. 你知道吗,S 有时候还能表示所属关系哦,像“my father’s car”,就是说“我爸爸的车”呀,这“S”多重要!

5. S 还会出现在一些固定搭配里啊,比如“as soon as”,“一……就……”,这不是挺常用的嘛!

6. 哇塞,S 也是很多名词复数形式的标志呀,像“dogs”“cats”,

没有“S”可不行,那可就成独苗苗啦!

7. 很多人的名字后面加上“S”也有特别的意思呢,比如“Jones’s”表示琼斯家的。

你说是不是挺有趣的?

8. S 还能在一些表示距离的词后面表示复数呀,像“miles”就是“英里”的复数呢。

9. 哎呀呀,S 真的是有好多好多用法呀,我们可得好好记着呢!

我的观点结论就是:S 的用法真是丰富多样又重要,我们得好好掌握它呀!。

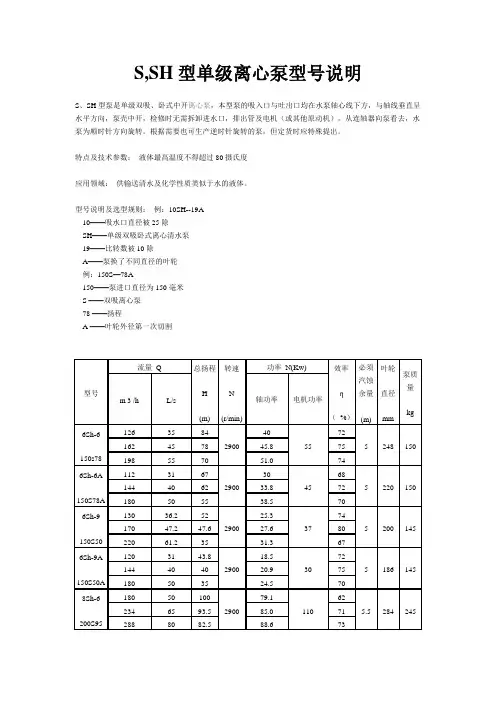

S,SH型单级离心泵型号说明

S、SH型泵是单级双吸、卧式中开离心泵,本型泵的吸入口与吐出口均在水泵轴心线下方,与轴线垂直呈水平方向,泵壳中开,检修时无需拆卸进水口,排出管及电机(或其他原动机),从连轴器向泵看去,水泵为顺时针方向旋转。

根据需要也可生产逆时针旋转的泵,但定货时应特殊提出。

特点及技术参数:液体最高温度不得超过80摄氏度

应用领域:供输送清水及化学性质类似于水的液体。

型号说明及选型规则:例:10SH--19A

10——吸水口直径被25除

SH——单级双吸卧式离心清水泵

19——比转数被10除

A——泵换了不同直径的叶轮

例:150S—78A

150——泵进口直径为150毫米

S ——双吸离心泵

78 ——扬程

A ——叶轮外径第一次切割

, ,。

音标/s/ 在英语中通常与字母"s" 相关,但它也可以出现在其他字母或字母组合中。

以下是一些发音为/s/ 的单词示例:

1. sun -太阳

2. sky -天空

3. sea -海洋

4. sand -沙子

5. song -歌曲

6. star -星星

7. stay -停留

8. stop -停止

9. story -故事

10. study -学习

11. sail -航行

12. sale -销售

13. salt -盐

14. same -同样的

15. save -保存

16. say -说

17. scar -伤疤

18. scart -刺

19. score -得分

20. screen -屏幕

21. script -剧本

22. scrap -废料

23. scrape -刮

24. screw -螺丝钉

25. scribble -乱写

26. scuba -潜水

27. search -搜索

28. season -季节

29. reason -原因

30. record -记录

这些单词中的/s/ 音标可以出现在单词的不同位置,有时在单词的开头,有时在单词的中间或结尾。

发音时,/s/ 音标通常由舌尖或舌边缘轻轻接触上齿或牙龈,同时声带振动。

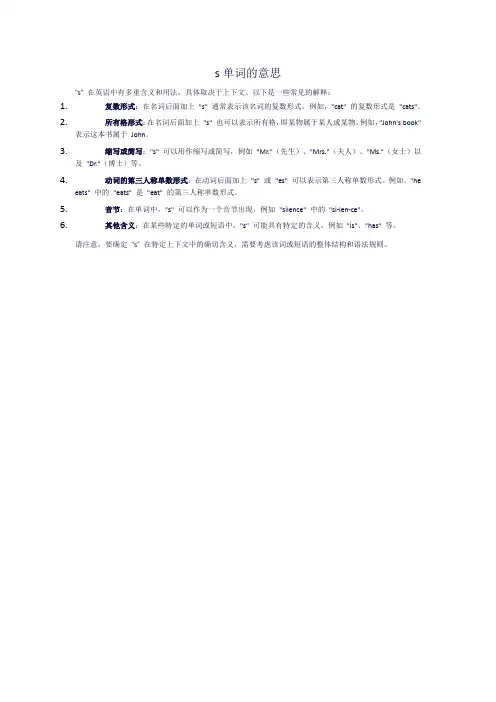

s单词的意思

"s" 在英语中有多重含义和用法,具体取决于上下文。

以下是一些常见的解释:

1.复数形式:在名词后面加上"s" 通常表示该名词的复数形式。

例如,"cat" 的复数形式是"cats"。

2.所有格形式:在名词后面加上"s" 也可以表示所有格,即某物属于某人或某物。

例如,"John's book"

表示这本书属于John。

3.缩写或简写:"s" 可以用作缩写或简写,例如"Mr."(先生)、"Mrs."(夫人)、"Ms."(女士)以

及"Dr."(博士)等。

4.动词的第三人称单数形式:在动词后面加上"s" 或"es" 可以表示第三人称单数形式。

例如,"he

eats" 中的"eats" 是"eat" 的第三人称单数形式。

5.音节:在单词中,"s" 可以作为一个音节出现,例如"silence" 中的"si-len-ce"。

6.其他含义:在某些特定的单词或短语中,"s" 可能具有特定的含义,例如"is"、"has" 等。

请注意,要确定"s" 在特定上下文中的确切含义,需要考虑该词或短语的整体结构和语法规则。

以s开头的英文单词现在小编为大家整理了英语单词,希望能帮助大家学习英语单词。

super超级supper晚饭summer夏季sun太阳sunny阳光明媚的son儿子sister姐妹student学生suspect嫌疑人sugar糖should应该shoe鞋子snack零食snake蛇snow雪snowy有雪的spend花(费)sing唱song歌singer歌手slim苗条的slow慢的sunglass太阳镜secular ['sekjulə] n. 牧师section chief 部门主管Salesman销售员Secretary秘书soldier士兵surgeon外科医生singer歌手steward ['stjuəd] n. 乘务员skipper ['skipə] n. 船长skater溜冰者social worker社会工作人员speech therapist语言医生special correspondent n. 特派记者spinner ['spinə] n. 纺纱工人system operator系统操作员systems analyst系统分析人员slave [sleiv] n. 奴隶State Food and Drug Administration 国家食品药品监督管理局sack n.+袋,包 vt.解雇sad a.悲哀的,悲痛的saddle n.鞍,鞍状物safe a.1.安全的,平安的 2.谨慎的,可靠的safety n.1.安全,保险 2.保险装置sail v.航行(于) vi.启航,开船 n.1.帆,篷 2.航行sailor n.水手,海员sake n.缘故,理由 for the ~ of 为了……起见salad n.凉拌菜,色拉salary n.薪水,工资sale n.1.出售,卖出 2.贱卖,廉价出售 3.销路,销售额 on ~减价出售salesman n.售货员,推销员salt n.盐 vt.腌,盐渍same a.相同的,同样的pron.同样的人,同样的事物the ~as 与……一致的与……相同的sample n.样品,试样vt.抽样试验,抽样调查sand n.1.沙 2.[pl.]沙滩,沙地sandwich n.夹心面包,三明治 vt.夹入中间satellite n.卫星satisfaction n.满意,满足 2.令人满意的事物satisfactory a.令人满意的satisfy vt.1.满足,使满意 2.说服,使相信Saturday n.星期六saucer n.茶托,碟子sausage n.香肠save v.1.救,拯救 2.储蓄,储存 3.节省saving n.1.[pl.]储蓄,存款 2.节省saw n.锯子,锯床 v.锯,锯开say v.说,讲 Vt.说明了,表明 n.发言权,意见scale n.1.刻度,标度 2.[pl.]天平,磅秤 3.比例,比例尺 4.大小,规模 on a large ~大规模地scarce a.1.缺乏的,不足的 2.稀有的scarcely ad.几乎不,简直没有scare v.惊吓,受惊 n.惊恐,恐慌scatter v.分散,散开,撒开scene n.1.景色,景象 2.舞台,发生地点 3.(戏剧等中)一场scenery n.1.风景,景色 2.舞台布景schedule n.时间表,日程安排表v.安排,排定on ~按时间表,及时,准时scheme n.1.计划,规划 2.诡计,阴谋 3.配置,安排scholar n.学者school n.1.学校 2.(大学里的)学院 3.学派,流派science n.1.科学, 2.学科scientific a.科学的scientist n.科学家scissors n.剪刀scold 责骂,申斥scope (活动,影响等的)范围 2.(发挥能力等的)余地机会score n.1.得分,分数 2.二十 v.得(分),记(……的)分数scratch v.抓,搔,抓伤 n.抓,搔,抓痕scream v.尖声叫 n.尖叫声screen n.1.屏幕 2.帘 vt.掩蔽,遮screw n.螺旋,螺钉 V.拧,拧紧sea n.海,海洋seal n.1.封铅,封条 2.印,图章 Vt.封,密封search v.& n.(for)搜查,搜寻season n.季,季节seat n.1.座,座位 2.所在地,场所 Vt.使坐下second num.第二 a.二等的,次等的 n.秒secondary a.1.将要的,二级的 2.嘴的,第二的secret a.秘密的,机密的 N.秘密,奥秘secretary n.1.秘书 2.书记section n. 2.断面,,剖面 3.部门,科secure a.1.(from,against)安全的,可靠的 2.放心的,无虑的security n.安全see v.1.看,看见2.领会,理解3.获悉,知道vt.1.会见,访问2.目睹,经历~ off 送行~ to 注意,务必seed n.种子 vi.结实,结籽 v.播(种)seek v.(after,for)寻找,探索seem v.好像,似乎seize v.抓住,逮住 vt.没收,查封seldom ad..很少,不常select vt.选择,挑选 a.精选的selection n.1.选择,挑选 2.选集,精选品self n.自我,自己selfish a.自私的sell v.出售,卖senate n.参议员,上院send vt.1.送,寄 2.派遣,打发~ for 派人去请senior a.1.年长的 2.资格较老的,地位较高的sense n.1.感官,官能 2.感觉 3.判断力,见识 4.意义,意思 Vt.觉得,意识到 make ~讲得通,有意义sensitive a.(to)1.敏感的 2.易受伤害的 3.灵敏的sentence n.句子 2.判决,宣判 vt.宣判,判决separate a.(from)分离的,分开的 v.(from)分离,分开September n.九月series n.1.系列,连续 2.丛书 a ~ of 一系列,一连串serious a.1.严肃的,庄重的 2.严重的,危急的 3.认真的servant n.仆人serve v.1.服务,尽责 2.招待,伺候 3.符合,适用 4.供应(饭菜)~as 作为,用作service n.1.[常pl.]服务,帮助 2.公共设施,公用事业 3.维修,保养 4.行政部门,服务机构 vt.维修,保养。

电源选项中S1,S2,S3,S4,S5的含义, 待机、休眠、睡眠的区别和优缺点电源选项中S1,S2,S3,S4,S5的含义以 ACPI 的規格來說吧!ACPI(Advance d Configu ration and Power Interfa ce),即高级配置与电源接口。

这种新的能源管理可以通过诸如软件控制"开关"系统,亦可以用Mod em信号唤醒和关闭系统。

ACPI在运行中有以下几种模式:S0 正常。

S1 CPU停止工作。

唤醒时间:0秒。

S2 CPU关闭。

唤醒时间:0.1秒。

S3 除了内存外的部件都停止工作。

唤醒时间:0.5秒。

S4 内存信息写入硬盘,所有部件停止工作。

唤醒时间:30秒。

(冬眠状态)S5 关闭。

判断系统是处于S1模式还是在S3模式,最简单的办法是仔细观察系统的情况:在ACPI的S1休眠模式下,只有CPU停止工作,其他设备仍处于加电状态。

而在S3模式(BIOS->电源管理->Suspend to RAM设为En able,除内存外其他设备均处于断电状态)。

所以我们只需按一下光驱上的弹出钮即可,不能打开光驱门则处于S3状态,反之则处于S1状态。

还有一种比较简单的方法是:在S3模式下,系统完全是安静的,所有风扇全部停止工作,此时系统不能从键盘唤醒,手工唤醒的方法只能是按前面板上的电源按钮。

S1 =>Standby。

即指说系统处于低电源供应状态,在 windows or BIOS 中可设定屏幕讯号输出关闭、硬盘停止运转进入待命状态、电源灯号处于闪烁状态。

此时动一动鼠标、按键盘任一键均可叫醒计算机。

S2 =>Power Standby。

和 S1 几乎是一样。

S3 =>Suspend to RAM。

即是把 windows现在存在内存中的所有数据保存不动,然后进入「假关机」。

s开头的英文单词编号单词解释1Sabbathn. 安息日2sabbaticala. 安息日的3sabern. 军刀,骑兵,骑兵队4sablen. 黑貂,adj. 黑色的5sabotagen. 阴谋破坏,颠覆活动6sabren. 军刀,击剑用刀7sacn. 囊8saccharinn. 糖精9sacerdotala. 僧侣的,祭司的,祭司制度的10sachemn. 酋长,Tammany 派的干部,政党领袖11sachetn. 小袋,小香袋12sackn.袋,麻袋;开除13sackbutn. 低音喇叭,竖琴的一种14sackclothn. 制袋用粗麻布,粗布衣,麻衣15sacramentn. 圣礼,圣事16sacramentaladj. 圣礼的,圣事的,秘迹的,圣典的,圣17sacreda.上帝的;神圣的18sacrednessn. 神圣不可侵犯性19sacrificen.&vt.牺牲;南祭20sacrificiala. 牺牲的,献祭的,具有牺牲性的21sacrilegen. 亵渎圣物,冒渎,悖理逆天的行为22sacrilegiousadj. 亵渎神圣的23sacrosanctadj. 神圣不可侵犯的24sadadj.悲哀的25saddenvt. 使忧愁,使悲哀26saddlen.鞍子,马鞍27saddlern. 制造马鞍的人,马具商,乘用之马28sadistica. 虐待狂的,残酷成性的29sadlyadv. 难过地,悲哀地;痛心的;伤心的;悲痛地,可惜;凄惨地;忧愁地悲哀地30sadnessn.悲痛,悲哀31safarin. 狩猎旅行,长途考察32safeadj.安全的33safeguardn.保护措施;护照34safelyadv. 安全地;平安地;可靠地;平安地;确实地35safetyn.安全,保险36saffronn. 番红花,此花的花茎,番红花色37sagv. 下陷,下垂,消沉38sagan. 英勇故事,长篇小说39sagaciousadj. 聪明的,睿智的40sagacityn. 聪慧,洞察力41sageadj. 智慧的n. 智者42sagon. 西米,西米椰子43saidadj. 上述的,该;say的过去式(分词);(法律、商业文件等用语)上述的,该…;说44sailvi.航行45sailboatn. 帆船46sailingadj. 启航的;n. 航行;驶行,航海,开航47sailorn.水手,海员,水兵48saintn.圣徒;基督教徒49saintlya. 圣洁的50saithsays的古体51saken.缘故,理由52salabilityn. 适销性53salableadj. 有销路的,适销的54salaciousadj. 好色的,淫荡的55salacityn. 好色,淫荡56saladn.色拉;莴苣,生菜57salamandern. 火蜥蜴,火怪,耐火的人58salaryn.薪金,薪水59salen.卖,销售60salesn. 销售;销售额;adj. 出售的61salesgirln. 女售货员62salesmann.售货员,推销员63salesmanshipn. 推销技术,销货术64saleswomann. 女售货员,女店员65salicinn. 柳醇,水杨甙66salientadj. 显著的,突出的67saliferousadj. 含盐的,产盐的68salinea. 盐的,苦涩的,由碱金属或含镁之盐类而成的69salinityn. 盐浓度,盐分70salivan. 唾液,口水71salivarya. 唾液的,分泌唾液的72sallown. 柳树,adj. 病黄色的73sallyn. 突击,出击,远足74salmonn.鲑,大马哈鱼75salonn. 沙龙,(法国等大邸宅的) 大厅,客厅76saloonn. 大厅,展览场,酒吧,大会客室77salsifyn. 波罗门参78saltn.盐79saltatoryadj. 跳跃的; 舞蹈的80saltpetern. 硝石81saltpetren.硝石82saltyadj. 咸的;盐的83salubriousadj. 有益健康的84salutaryadj. 有益的,有益健康的85salutationn. 致敬,(信开头)称呼86salutevi.,vt.&n.敬礼;致敬87salutionn. 致敬88salvagen./v. (从灾难中)抢救,海上救助89salvationn. 得救,拯救90salven. 药膏,v. 减轻,缓和91salvern. 盘子,盆子92Samaritanadj. 撒马利亚的93sameadj.同样的94samisenn. 三弦琴95sammy萨米(男名)96sampann. 舢板,小船97samplen.样品;实例,标本98samplern. 刺绣花样,取样员99samplingn. 抽样100samurain. (日本封建时代的) 武士101sanatoriumn. 疗养院,休养所102sanctificationn. 神圣化,灵化,使神圣103sanctifyvt. 使神圣,奉献给神,使成为神圣之物104sanctimoniousadj. 伪装虔诚的105sanctionn./v. 批准,认可106sanctityn. 神圣,尊严,圣洁107sanctuaryn. 圣堂,避难所108sanctumn. 圣地,密室109sandn.沙,沙地110sandaln. 凉鞋,草鞋,檀香木111sandblastn. 喷沙,喷沙器112sandman] (传说撒沙于小孩眼睛,将其113sandpapern. 沙纸114sandpipern. 矶鹞115sandsn. 沙漠116sandstonen. 沙岩117sandwichvt.夹入,挤进118sandyn.沙的,含沙的119saneadj. 神志清楚的,明智的120sangsing的过去式;唱121sangfroidn. 沉着,临危不惧122sanguinaryadj. 有血的,血腥的123sanguineadj. 充满希望的,乐观的124sanitariumn. 疗养院,疗养所,静养地125sanitaryn. 疗养院;公共厕所;adj. 卫生的,清洁的;神智清楚的,心理健全的126sanitationn. (公共)卫生127sanityn. 神志清楚128sanksink(下沉)的过去式;沉下129sapn.树液130sapida. 有味道的,风味良好的,有趣味的131sapiencen. 贤明,睿智.132sapientadj. 有智慧的133saplessadj. 没有无气的134saplingn. 树苗,年轻人135sapphiren. 青玉,蓝宝石,adj. 天蓝色的. 136sappya. 树液多的,精力充沛的137sapsuckern. 啄木鸟的一种138sara萨拉(女名)139saracenn. & a. 撒拉逊人(的)140sarcasmn. 讥讽,讽刺,嘲笑141sarcasticadj. 讽剌的142sarcasticallyad. 讽刺地143sarcoman. 肉瘤144sarcophagusn. (精美的)石棺145sardinen.沙丁鱼146sardonicadj. 讽刺的,嘲笑的147sargasson.马尾藻148sarsaparillan.『植物』洋菝契149sartorialadj. 裁缝的,缝制的150sashn. 腰带,肩带.151sassafrasn.『植物』察树152satsit的过去式(分词);坐153Satann. 撒旦,魔鬼154satanicadj. 穷凶极恶的155satcheln. 书包,小背包156satev. 使心满意足,使厌足157sateenn. 棉缎158satelliten.附属物159satiablea. 可满足的160satiatev. 使饱足,生腻161satiationn. 充分满足,饱,足162satietyn. 饱足,满足163satinn. 缎子,假缎164satinwoodn. 缎木,缎木木材165satinyadj. 光滑的,柔细的166satiren. 讽剌(作品)167satiricaladj. 讽剌的,爱挖苦的168satiristn. 讽刺诗作者,讽刺家,爱挖苦别人的人169satirizevt. 讽刺,挖苦,对...写讽刺文章170satisfactionn.满意;快事;赔偿171satisfactorilyadv. 圆满地;令人满意地172satisfactorya.令人满意的,良好的173satisfied满足的174satisfyvt.使满意;使满足175satisfyinga. 令人满意的176satrapn. 太守,总督,暴吏177saturatevt. 使渗透,浸透,使充满,使饱和178saturationn.饱和(状态);浸透179Saturdayn.星期六180Saturnn.农神;土星181saturnalian. 纵情狂欢182saturnineadj. 忧郁的,阴沉的183satyrn. 好色之徒,森林之神184saucen.调味汁,酱汁185saucepann. 长柄而有盖子的深锅子,炖锅186saucern.茶托,浅碟187saucya. 傲慢的,莽撞的,活泼的,漂亮的188sauerkrautn. 泡甘蓝(油菜)菜189sauntern./v. 闲逛,漫步190sausagen.香肠,腊肠191sauten. 炒菜,煎肉192savagen.野人adj.野蛮的193savagelyad. 野蛮地;原始地194savageryn. 野性,原始状态,野蛮人195savannan. 大草原;热带或亚热带之大草原196savantn. 专家,学者,博学之士197savevt.救,挽救198savern.救助者,援救者199savingn. 搭救;节约;存款;储蓄a. 保存的;补偿的;储蓄,存款,节约的;挽救的200savingsn. 储金201saviorn. 救助者,救世主,救星202saviourn. 救助者,救世主,救星203savoirn. 才干;急智;手腕204savorn. 味道,滋味,v. 品尝,欣赏205savorya. 风味极佳的,可口的,味香的206savourn. 滋味,气味,食欲207savourya. 风味极佳的,可口的,味香的208sawn.锯子vt.锯,锯开209sawdustn. 锯屑210sawmilln.锯木厂211sawyern. 锯木匠,漂流水中的树木,食木虫212Saxonn. 撒克逊人213saxophonen. 萨克斯管214sayv.说,讲215sayingn.话;俗话;谚语216saysv. 说(第三人称单数)217scabn. 创口上所结的疤,痂218scabbardn. (刀、剑)鞘,枪套219scabrousadj. 粗糙的220scadsn. 大量,巨额221scaffoldn. 脚手架(造房时搭的架子)222scalar标量223scaldv. 烫,用沸水消毒n. 烫伤224scaldingadj. 滚烫的225scalen.天平,磅秤,秤226scallopn. 扇贝227scalpn. 头皮,战利品v. 击败228scalpeln. 外科手术刀,解剖刀229scalyadj.有鳞的; 鳞状的230scamperv. 奔跑,快跑231scanvt.细看;浏览;扫描232scandaln.丑事,丑闻;耻辱233scandalizevt. 使生反感,使震惊,诽谤234scandalmongern. 专事诽谤的人,到处传播丑闻的人235scandalousadj. 丢脸的,诽谤性的236Scandinavian. 斯堪的那维亚,北欧237scandinaviana. 斯堪的纳维亚的238scannern. 扫描器239scantadj. 不足的,缺乏的240scantlingn. 一点点,少量241scantya. 缺乏的,仅有的,节省的,狭小的,242scapev. 避开,避免;逃跑,逃脱243scapegoatn. 替罪的羔羊,替人顶罪者,替身244scarn.伤疤,伤痕;创伤245scarabn. 甲虫246scarcea.缺乏的;希有的247scarcelyad.仅仅;几乎不248scarcityn.缺乏,不足,萧条249scarevt.惊吓vi.受惊250scarecrown. 稻草人,衣衫褴褛的人251scaredadj. 怕;惊慌的,吓坏了的;害怕的,恐惧的252scarfn.围巾,头巾;领带253scarifyvt. 乱刺,乱割,松(土),苛责,乱划254scarletn.猩红色a.猩红的255scarpn. 悬崖,陡坡256scatint. 嘘!257scathen./v. 损害,烧焦258scathingadj. 苛刻的,严厉的259scattervt.使分散vi.分散260scatterbrain注意力不集中的人261scattereda. 分散的262scavengev.(在废物中)寻觅,(动物)食腐肉263scavengern. 食腐动物,拣破烂的人264sceen银幕265scenarion. 剧情说明书,剧本266scendvi.(船)被波浪抬起267scenen.(戏剧等的)一场268sceneryn.舞台布景;风景269scenicadj.天然景色的270scentn.气味,香味;香水271scentlessa. 无气味的,无臭的,遗臭已消失的272sceptern. 笏,节杖,王权273scepticn. 怀疑论者274scepticaladj. 怀疑的,不相信的275scepticismn. 怀疑论,怀疑主义276sceptren. 权杖,君权277schedulen.时间表;计划表278schematicadj. 扼要的,图解的279schematizev. 扼要,表示280schemevt.计划vi.搞阴谋281schemern. 计划者,阴谋家,策士282scheminga. 计划的;诡计多端283schismn. 组织分裂284schismaticadj. 分裂的285scholarn.学者(尤指文学方面)286scholarshipn.学业成绩;奖学金287scholastica. 学校的,学校教育的,学者的, 288schooln.学校289schoolbagn. 书包290schoolbookn. 课本,教科书291schoolboyn. 男学生292schoolchildrenn.小学生293schoolfellown. 同学294schoolgirln.中小学女学生295schoolhousen.校舍296schoolingn. 教育;学校教育;正规学校教育297schoolmann. 教授,烦琐哲学家,学校教师298schoolmastern.(男)教师;校长299schoolmaten.同学300schoolmistressn. 女教师;女校长301schoolroomn.教室302schoolteachern. (中小学)教师303schoolyardn.校园;操场304schoonern. 大酒杯,大篷车305sciencen.科学306scientificadj. 科学的;科学(上)的307scientificala. 科学的308scientificallyad. 合乎科学地,学问上,有系统地309scientistn.(自然)科学家310Scifin.(science fiction的缩略)科幻小说311scimitarn. 弯刀,半月形刀312scintillan. 一点,丝毫313scintillatev. 闪烁、(淡吐)流露机智314scintillatingadj. 才气横溢的315scintillationn.火花的迸出,闪烁316sciolismn. 一知半解的学问317scionn. 嫩芽,子孙318scissorsn.剪刀,剪子319scleran. 巩膜320scoffvt.&vi.嘲笑,嘲弄321scoffern. 嘲笑者322scoldvt.斥责,责备323sconcen. 突出的烛台,头,头盖324sconen. 烤饼325scoopn. 铲子,勺子,独家新闻,口,穴326scootern. (儿童玩的) 滑行车,踏板车327scopen.范围;余地,机会328scorchvi.烧焦,枯萎;挖苦329scorchingadj. 灼热的;酷热的330scoren.二十;(比赛)得分331scornn.轻蔑;嘲笑vt.轻蔑332scornfula. 轻蔑的333scornfullyad. 轻蔑地,藐视地334scorpionn. 蝎子335Scotn. 估定的款项,税赋336Scotchv. 镇压、粉碎337Scotlandn.苏格兰338scotsadj. 苏格兰(人)的339scotsmann. 苏格兰人340scott斯科特(姓)341Scottisha. 苏格兰的,苏格兰人的342scoundreln. 恶棍343scourv. 四处搜索344scourgen./v. 鞭笞,磨难345scoutvt.搜索,侦察,跟踪346scoutingn. 童子军活动347scoutmastern. 童子军领队348scown. 大型平底船,盘艇349scowln. 皱眉,怒视,愁容350scramblevi.&n.爬行,攀登351scrapn.碎片;废料vt.废弃352scrapbookn. 剪贴簿353scrapevt.&vi.&n.刮,擦354scrapern. 刮刀,刮的人355scrappyadj. 好斗的,生气勃勃的356scratchvt.&vi.&n.搔;抓357scrathv. 抓,搔,抓伤;n. 抓痕358scrawlv. 潦草地写,乱涂359scrawnyadj. 细而瘦的360screamvi.尖叫;呼啸361screaminga. 发尖叫声的362screechvi.发尖叫声363screedn. 冗长的演说,长篇大论的文章364screenn.屏;屏幕vt.掩蔽365screwn.螺旋,螺丝vt.拧紧366screwdrivern. 螺丝起子367scribblev. 乱写、乱涂368scribblern. 潦草书写的人,三流作家,小文人369scriben. 书记,抄写员,划线器,作家,作者370scripn. 便条,纸条,纸片371scriptn. 手迹,手稿,副本372scripturala. 圣经的,手稿的,依据圣经的373scripturen.《圣经》;圣书374scrivenern. 代书,公证人,代笔人375scrolln. 卷轴,纸卷,画卷376scrubn.&vt.擦洗,擦净377scrumptiousadj.(食物)很可口的,漂亮的378scruplen./v. 顾忌、迟疑379scrupulousadj. 谨慎小心的、细心的380scrutingn. 详细检查,仔细观察381scrutinizen. 详细检查,细读382scrutinyn. 细看,仔细检查,监视,选票的复查383scudv. 疾行,疾驶384scuff拖足而走385scufflev. 混战,打斗386sculln. 短桨,尾桨,橹387sculleryn. 碗碟洗涤处,碗碟储藏室388scullionn. 在厨房里帮忙的仆人389sculptv. 雕刻390sculptorn. 雕刻家391sculpturala.雕刻的392sculpturen.雕刻(术);雕刻品393scumn. 泡沫,社会渣滓394scuppern. 排水孔395scurfn. 头屑,皮屑396scurrilousadj. 下流的、恶言毁谤的397scurryv. 急跑,疾行398scurvyadj. 卑鄙的、可鄙的399scutcheonn.饰有纹章的盾400scuttlev. 急赶、疾走,逃辟401scythen. 大镰刀402sean.海洋,海403seabedn. 海床404seaboardn. 海岸,沿海地带405seacoastn. 海岸,沿岸406seafarern. 船员,航海家407seafaringadj. 航海的,跟航海有关的408seafoodn.海产品,海鲜409seagulln. 海鸥410sealn.封蜡;印记vt.封411sealeda.密封的;封口412seamn.缝口;接缝;骨缝413seamann.海员,水手;水兵414seamanshipn. 船舶操纵术,航海技术415seamlessa. 无缝合线的,无伤痕的416seamstressn. 女裁缝417seamyadj. 黑暗的,恶劣的418seaportn.海港,港市419searv. (以烈火)烧灼420searchvt.在…中搜寻,搜查421searchern. 搜寻者422searchingn. 搜索423searingadj. 灼热的424seascapen. 海景425seashoren. 海岸,海滨426seasicka. 晕船的427seasiden.海滨(胜地);海边428seasonn.季,季节,时节429seasonablea. 适合于季节的,合于时宜的,应时的430seasonala. 季节性的431seasoningn. 调味品,佐料432seatn. 座;座部;座位;中心;席位;所在地,场所;v. 就座;容纳433seated坐着434Seattlen.(美国城市名)西雅图435seawardn. 朝海的方向436seawatern. 海水437seaweedn. 海草,海藻438seaworthya. 适于航海的,经得起航海的439sebaceousa. 脂肪的,脂肪质的,分泌脂肪的440secedev. 正式脱离或退出(组织)441secessionn. 脱离、退出442secludev. 和别人隔离443secludedadj. 隐遁的,隔绝的444seclusionn. 隐遁,隔离445seclusiveadj. 好隐居的446secondnum.第二a.二等的447secondarya.第二的;次要的448secondhandadj. 二手的,间接的449secondlyadv.其次;第二(点)450secrecyn. 保密451secretn.秘密452secretarialadj. 秘书的;文书的453secretariatn. 秘书处454secretaryn.秘书;书记;大臣455secretev. 分泌,藏匿456secretionn. 分泌,分泌物,分泌液457secretivea. 保密的;喜欢保密的458secretlyad. 秘密地;隐蔽地459sectn. (宗教等)派系460sectariana. 宗派的,党派心强的,偏狭的461sectaryn. 属于某宗派的人,非教会派的新教徒462sectionn.切下的部分463sectionala. 部分的,部门的,节的,截面的464sectorn. 扇形,尺规,函数尺465secularadj. 世俗的、尘世的466securea.安心的;安全的467securelyad. 安全地;无疑地468securitiesn. 证券,有价证券;债券469securityn.安全,安全感470sedann.色当(法国城市)471sedateadj. 安静的、镇静的472sedativen./adj. (药物)镇静的,镇静剂473sedentaryadj. 久坐的,固定不动的474sedgen. 蓑衣草475sedgya. 蓑衣草密茂的,蓑衣草的476sedimentn. 沉淀物,渣477sedimentarya. 沉渣的,沉淀物的,由沉淀物所生成的478seditionn. 煽动叛乱479seditiousadj. 煽动性的480seducev. 勾引、诱惑481seductiveadj. 诱人的、有魅力的482sedulousadj. 聚精会神的、勤勉的483sedulouslyad. 孜孜不倦地484seev.看,看见;了解485seedn.种子486seedern. 播种者,播种机,去核器487seedlingn. 幼苗488seedsmann. 播种者,卖种子的店铺489seeingsee的现在分词;n. 视觉;看见;观看490seekvt.寻找,探索;试图491seemvi.好像,似乎492seeminga. 表面上的;n. 外观493seeminglyad.表面上,外表上494seemlya. 适当的,恰当的,合适的,好看的495seenv. see(看)的过去分词;看见496seepv. (液体等)渗漏497seepagen. 渗出物498seern. 预言者,先知,幻想家499seesawn. 跷跷板,上下动500seethev. 沸腾,汹涌501seethinga. 火热的;激昂的502segmentn.切片,部分;段,节503segmentala.部分504segregatev. 隔离505segregationn. 种族隔离506seigneurn. 封建领主,君主,诸侯507seinen. 塞纳河(法国北部);大捕鱼网;拉网508seismicadj. 地震的509seismometern. 测震表510seizevt.捉,抓;掠夺511seizuren. 捕获,夺取,占领,充公,没收,512seldomadv.很少;不常513selectvt.&vi.选择;挑选514selecteda. 精选的515selectionn.选择,挑选;精选物516selectivea. 有选择性的517selfn.自我,自己518selfisha.自私的,利己的519selfishnessn. 自我中心,利己主义,任性520selflessadj. 无私的,忘我的521selflesslyadv. 忘我地522selflessnessn. 无私,忘我523selfsamea. 完全一样的,同一的524sellvt.&vi.卖525sellern.卖者;行销货526selvagen. 布等的织边,镶边527selvedgen. 布等的织边,镶边528selvesn. self(自我)的复数形式529semaphoren. 旗语530semblancen. 外貌,相似531semestern.半年;学期,半学年532semicirclen.半圆,半圆形体533semicirculara. 半圆的534semicolonn. 分号(;)535semiconductorn. 半导体536seminaladj. 有创意的537seminarn. 研讨会,学术讲座;研究班538seminaryn. 神学院539Semiticadj. 闪族的540semitropicala. 亚热带的541senaten.参议院,上院542senatorn.参议员;评议员543senatoriala. 参议院的,参议员的544sencen. 感官,官能;感觉,判断力;意义545sendvt.送;派遣;发射546sendern. 寄信人547senescencen. 老朽,衰老548senescentadj. 衰老的,老化的549seneschaln. 管家,总管550senileadj. 年老的551senilityn. 衰老,老化552seniora.年少的;地位较高的553seniorityn. 长辈,前任者的特权,老资格554sensationn.感觉,知觉;轰动555sensationaladj. 耸人听闻的,轰动的556sensen.感官;感觉;见识557senselessa.愚蠢的,无意义的558sensibilityn. 感性,感觉,情感559sensibleadj. 合情合理的;感觉得到的;明智的;感知的;明显的;通情达理的;可察觉的;明理的560sensitivea.敏感的;灵敏的561sensitivityn. 敏感性;灵敏性;灵敏度562sensorn. 传感器;灵敏元件;敏感元件563sensorya. 感觉的564sensualadj. 肉欲的、淫荡的565sensualityn. 淫荡、好色566sensuousa. 感觉上的,给人美感的567sentvt. sand的过去式与过去分词568sentencevt.判决,宣判569sententiousadj. 好说教的,简要的570sentientadj. 有知觉的,知悉的571sentimentn.感情;情操;情绪572sentimentala. 多愁善感的573sentimentalistn. 容易感伤的人,多愁善感的人,感情574sentimentalityn. 多感情,多愁善感,感伤癖575sentimentallyad. 感情上576sentineln. 哨兵577sentryn. 哨兵,步哨578sepaln. 萼片579separablea. 可分离的,可分的580separatea.分离的;个别的581separateda. 分开的582separatelyadj. 分离地;单独地;adv. 分别地;分离地;孤独地;各别地,单独地583separationn.分离,分开;分居584separatorn. 区分者,从事分离的人,分离器585sepsisn. 脓毒病,败血586Septembern.九月587septicadj. 受感染的、腐败的588sepulchern. 埋葬所,坟墓589sepulchraladj. 坟墓的,阴深的590sepulchren. 坟墓,埋葬所591sepulturen. 埋葬,坟墓,墓592sequaciousadj. 前后一贯的,盲从的593sequeln. 继续,续集,趋势,结果,结局,594sequencen.连续,继续;次序595sequentn. 后果,继起的事596sequentialadj. 连续的,一连串的597sequentiallyad. 顺序地598sequesterv. (使)隐退,隐居599sequestratev. 扣押,没收600sequestrationn.隔离; 退隐,隐遁601sequinn. 亮片602sequoian,. 红杉603seraglio(C) (回教国家的) 后宫,土耳其皇宫604seraphn. 六翼天使605seraphicadj. 如天使般的,美丽的606sereadj. 干枯的,凋萎的607serenaden. 夜曲,小夜曲608serendipityn. 善于发掘新奇事物的天赋609serenea. 宁静的,沉着的,安详的,晴朗的610serenityn. 宁静,沉着,晴朗611serfn.农奴612serfdomn. 农奴的身分; 农奴制度613sergen. 斜纹哔叽布料614sergeantn.警士;军士615serialn. 序列,连载小说616sericulture养蚕617seriesn.连续,系列;丛书618seriousa.严肃的;认真的619seriouslyadv. 严肃地,严重地;认真地;重大620seriousnessn. 认真621sermonn.布道,讲道,说教622sermonize说教,讲道623serpentn.蛇(尤指大蛇或毒蛇)624serpentineadj. 似蛇般绕曲的,蜿蜒的625serratedadj. 呈锯齿状的626serrieda. 密集的,林立的,重重叠叠罗列的627serumn. 浆液,血清,乳浆628servantn.仆人,佣人629servevt.开(饭),上(菜)630servern. 服伺者,服勤者,伺候者631servicen.服务632serviceablea. 有用的,耐用的633servicesn. 部门634servileadj. 奴性的,百依百顺的635servilityn. 奴态,卑屈636servitorn. 仆人,从仆,工读生637servituden. 奴隶状态,惩役,地役权638sesamen. 芝麻639sessionn.会议,一段时间640setn.(一)套vt.镶,嵌641setbackn. 挫折,失败;(疾病的)反复642setteen. 有靠背的长椅643settern. 安放者,镶嵌者,排字工人644settingn.安装,调整;环境645settlevt.安排;安放;调停646settleda. 固定的647settlementn.调停;(新)住宅区648settlern. 移民者,居留者,赠予者649setupn. 安排,准备,配置650sevennum.七651sevenfoldadj. 七倍652seventeennum.十七,十七个653seventeenthnum. 第十七,十七分之一的654seventhnum.第七;七分之一655seventiethnum. 第七十,七十分之一的656seventynum.七十,七十个657severv. 切断,脱离658severaladj.&pron.几个,数个659severancen. 切断,分离660severea.严格的;严厉的661severel几个,数个662severelyadv. 严厉地,苛刻地;严肃地;严格地;剧烈地663severityn. 严格,严重,激烈664sewvi缝纫vt.缝制,缝补665sewagen. (下水道)污水;污物666sewed缝667sewern. 排水沟,下水道668seweragen. 排水设备,污水669sewingn. 缝纫,缝制物;(书的)装订670sewn逢;缝671sexn.性别,性672sextantn. 六分仪(航海定向仪器)673sextonn. 教堂司事674sexuala. 性的,性别的675sexualityn. 性欲676shabbyadj.破旧的;蹩脚的677shackn. 简陋的小屋,棚屋678shacklen. 脚镣,枷锁679shadn. 鲱鱼类680shaden.(色彩的)浓淡,深浅681shadown.影子682shadowya.有影的;幽暗的683shadya.成荫的,阴凉的684shaftn.(工具的)柄,杆状物685shagn. 粗毛,蓬乱一团686shaggya. 毛发蓬松的,长浓而粗的,表面粗糙的687shakevt.摇,使震动n.摇动688shakenshake的过去分词;摇;摇动689shakern. 摇动者;摇荡器;搅拌器690shakespearen. 莎士比亚691shakya. 震动的,摇晃的,动摇的692shalen. 页岩693shallv.aux.(我,我们)将要694shallopn. 轻舟,小舟695shallowa.浅的;浅薄的696shamn.假冒;膺品vt.假装697shamblevi. 蹒跚地走,摇摇晃晃地走,摇晃不稳698shamblesn. 混乱之处,凌乱的地点699shamen.羞耻,羞愧;羞辱700shamefaceda. 害羞的,谦逊的,不惹眼的,羞耻的701shamefula.可耻的;不道德的702shamelessa. 不知羞耻的703shampoovt.用洗发剂洗n.洗头704shanghai上海705shankn. 胫,腿骨,杆,柄706shantyn. 简陋的小木屋707shapen.形状;情况vt.形成708shapelessadj. 无形的,无定形的709shapelya. 样子好的,定形的,形状美好的710shardn. (陶器等)碎片,破片711sharevt.分享n.一份712shareholdern. 股东713sharesn. 股票714sharkn.鲨鱼;贪婪狡猾的人715sharon莎伦(女名)716sharpadj.锋利的;尖的717sharpenvt.削尖,使敏锐718sharpenern. 铅笔刀,磨石719sharplyad.锐利地,敏锐地720sharpnessn. 锐利,严厉,疾速721shattervt.粉碎,破碎;毁坏722shavevt.剃,刮vi.修面723shavingn. 刮,修胡须,削724shavingsn. 刨花725shawln. (妇女用)披肩,围巾726shayn.轻便马车727shepron.她728sheafn. 一捆、一束729shearvt.剪;剥夺vi.剪730shearsn. 大剪刀731sheathn.壳,套;(刀,剑)鞘732sheathevt. 插入鞘,覆盖733shedn.棚;小屋734sheenn. 光辉,光泽735sheepn.羊,绵羊736sheepfoldn. 羊圈737sheepisha. 懦弱的,羞怯的738sheepskinn.羊皮739sheera.纯粹的;全然的740sheetn.被单;纸张;薄板741shelfn.搁板,架子742shelln.炮弹,猎枪子弹743shellacn. 虫漆744shellern. 剥壳者,脱壳机745shellya. 多壳的,壳一般的,由壳而成的746sheltern.隐蔽处;掩蔽,庇护747sheltereda. 蔽阴的748shelvev. 搁置749shelvesshelf的复数750shepherdn.牧羊人,羊倌751shepherdessn. 牧羊女752sherbetn.冰果冻753sheriffn.郡长;警察局长754sherryn. 雪利酒,葡萄酒755shibbolethn. 陈旧语句,习俗756shieldn.盾;防护物vt.保护757shiftvt.替换,转移n.转换758shifting移动,转嫁759shiftlessadj. 没有决断力的,偷懒的760shillingn.先令761shimmerv. 闪烁,微微发亮762shinn. 胫骨763shinev.照耀;发光764shinglen. 木瓦,屋顶板765shinglesn. 『医』带状泡疹766shininga. 闪闪发光的,明显的767shinya. 有光泽的,发光的,辉煌的768shipn.轮船769shipboardn. 舷侧,船770shipbuildingn.造船(业),造船学771shipmailn. 随船带交772shipmaten. 同船水手773shipmentn.装货;装载的货物774shipownern. 船主775shippern. 装货者,货主776shippingn. 船运,装运;船运业;船舶(总数);海运777ships轮船778shipshapeadj. 整洁的,井然有序的779shipwreckn.船舶失事780shipwrightn. 造船者781shipyardn. 造船所782shiren. 郡783shirkv. 逃避,规避784shirrn. 宽紧线,橡皮线785shirtn.(男试)衬衫786shirtingn. 衬衫衣料787shivervi.颤抖,哆嗦n.冷颤788shoaln. 浅滩、浅水处,一群(鱼)789shockn.冲击;震惊vi.震动790shocked震惊的791shockinga. 令人震惊的;可怕的792shoddyadj. 伪造的;劣等的;n. 劣质的,冒充好货的793shoen.鞋794shoecase鞋柜795shoemakern. 鞋店,皮鞋匠796shoesn. 鞋797shoestring小额资本798shoneshine的过去式(分词);发光;照耀;发光(shone=shined) 799shooint. 赶走鸟等时所发声音800shookshake的过去式;摇;摇动801shootvt.发射;射中n.发芽802shootingn. 射击803shopn.商店,店铺;车间804shopkeepern.店主805shopmann.售货员806shoppern. 购物者807shoppingn. 买东西;购物808shopwindown. 商店橱窗809shoren.滨,岸810shorewardad. 向岸,朝岸,朝向陆地811shornshear的过去分词812shortadj.矮的813shortagen.短缺,不足额814shortcaken.油酥糕饼815shortcomingn.短处,缺点816shortcutn. 近路,捷径817shortenvt.弄短,缩小,减少818shorteningn. 缩短819shortfall缺额,缺少,不足,亏空820shorthandn.速记,速记法821shorthanded人手不足的822shorthornn. 短角牛823shortlyadv.立刻;不久824shortmann. 矮人825shortnessn. 短促,短,矮826shortsn. 短裤;短运动裤827shose选择828shotn.发射;射击声829shouldaux.v.将;万一;就830shouldervt.承担,挑起,肩负831shoutvi.vt.&n.喊;高呼832shoutingn. 叫喊声,哗笑833shovevt.推vi.(使劲)推834shoveln.铁锨835shovelfuln. 一铁铲836showvt.给…看;表明837showcasen. 陈列柜838showed出示839showervi.下阵雨vt.使湿透840showerya. 阵雨的841showingn. 显示,表现842showmann. 马戏团的老板,玩杂耍的人843shownshow的过去分词;出示;出示(shown=showed) 844showoffn. 卖弄者845showpiecen. 陈列品,精品,样品846showroomn. 展室,陈列室847showyadj. 鲜艳的,显眼的848shrankshrink的过去式849shrapneln. 开花弹,榴弹,弹片850shredv. 切成细条,撕成碎片851shrewn. 泼妇,一种似鼠的动物名852shrewdadj. 判断敏捷的,精明的853shrewisha. 泼妇一样的854shrewsburyn. 舒兹伯利(英国城市)855shriekvi.尖声喊叫n.尖叫声856shrilla.尖声的vt.尖声地叫857shrillyad. 尖声地858shrimpn.(小)虾,河虾,褐虾859shrinen.神殿,神龛,圣祠860shrinkvi.收缩;缩小;退缩861shrinkagen. 收缩,缩小,减低862shrivevi. 忏悔863shrivelv. (使)皱缩,干涸,枯萎864shroudn. 寿衣,遮蔽物v. 覆盖865shrubn.灌木,灌木丛866shrubberyn. 灌木,灌木林867shrugvt.&vi.耸(肩) n.耸肩868shuckn. (植物的)壳,夹,无用之物869shuddern. 战栗,发抖870shufflev. 拖步走,支吾,洗牌871shunv. 避免,闪避872shuntv. 使(火车)转到另一轨道,转移方向873shutvt.&vi.关闭874shuten. 舒特(姓)875shuttern.百叶窗;(相机)快门876shuttlen.(织机的)梭877shuttlecockn. 羽毛球878shya.易受惊的;害羞的879shylockn. 夏洛克(男名)880shylyadv. 怕羞地;胆小地;羞怯地;畏缩地;害羞地881shynessn. 羞怯,胆怯882sin.((符号))『化学』silicon883Siameseadj. 暹罗的; 暹罗语884siberian. 西伯利亚885siberiana. 西伯利亚的886sibilantadj. 嘶嘶作声的887siblingn. 兄弟或姊妹888sibyln. 女预言家,女先知889sibyllineadj. 预言的890sicilyn. 西西里(岛)(意大利)891sicka.有病的;恶心的892sickbedn. 病床893sickenvt. 患病,使厌倦,使恶心894sickeninga. 令人作呕的;引起疾病的895sicklen. 镰刀896sicklya. 病弱的,阴沉的,无精打采的897sicknessn.疾病898siden.边;面899sideboardn. 餐具柜900sidecarn. 轻快的双轮马车,机器脚踏车的边车901sidelinen. 副业,旁线,旁观者的看法,兼职,902sidelongad. 向横,向侧面,斜向着,间接地903siderealadj. 恒星的904sides侧905sidesplittingadj. 令人捧腹大笑的906sidewalkn. 人行道907sidewayad. & a. 斜向一边(的),侧身(的)908sidewaysad.斜向一边地909sidlev. (偷偷地)侧身而行910siegen.包围,围攻,围困911siennan. 赭色912sierran. 呈齿状起伏的山脉913sieven. 筛,滤杓v. 筛出、滤出914siftvt.筛,过滤vi.通过915siftern. 筛子916sighn.&vi.叹气,叹息917sighs叹息918sightn.视力;视觉;见919sightlessa. 盲目的,不在目前的,不可见的920sightlya. 看着舒服的,悦目的,眼界好的921sightseeingn.观光,游览922signn.征兆,迹象,病症923signaln.信号vi.发信号924signalizevt. 使著名,使显著,使显眼925signatory签字人;签过名的926signaturen.署名,签字,签名927signboardn. 招牌,布告板928signetn. 印,图章929significancen.意义,意味;重要性930significantn.有意义的;重要的931significationn. 含义,意义,表示932signifyvt.表示,意味着933signorn.…先生,…君934signoran.…夫人,…太太935signpostn. 招牌柱,广告柱,路标936Sikhn. (印度的) 锡克教徒937silagen. 储藏的饲料938silevi. 下滑,下降939silencen.寂静,沉默940silenta.沉默的;寂静无声的941silentlyadv. 静静地;寂静地;沉默地942silhouetten. 剪影,轮廓943silican. 硅石944silicaten. 硅酸盐945siliconn.硅(旧名矽)946silkn.(蚕)丝;丝织品,绸947silkena. 丝的,绸制的,柔软的,圆滑的948silkwormn.蚕949silkya. 丝的,柔滑的950silln. 基石,门槛,窗台951sillya.傻的,愚蠢的952silon. 筒仓,地窖953siltn. 淤泥、淤沙954silvana. 森林的,乡村的955silvern.银;银子;银器956silversmithn. 银器匠957silverwaren. 银餐具;银器958silverya. 象银的,银色的,银铃一样的959simianadj. 猿的、猴的n. 类人猴960similara.相似的,类似的961similarityn.类似,类似处962similarlyadv. 同样地;类似地,相似地963similen. 直喻,明喻964similituden. 相似,外表965simmervt. 慢慢地煮966simonyn. 僧职买卖,僧职买卖罪967simperv. 傻笑、假笑968simperingadj. 傻笑的969simpleadj.单纯的;简易的970simpletonn. 笨蛋,傻子971simplicityn.简单,简易;朴素972simplifieda. 精简了的,简化了的973simplifyvt.简化,使单纯974simplistica.过分简单化的975simplyadv.简单地;仅仅976simulatev. 假装,模仿977simulatedadj. 伪装的,模仿的978simultaneousa.同时的,同时存在的979simultaneouslyadv. 同时地;同时,一起980simutaneousa.同时进行的981sinn.罪,罪孽vi.犯罪982sinceconj.由于;既然983sincerea.真诚的;真挚的984sincerelyadv. 真诚地;诚恳地;真挚地985sincerityn.真诚,诚意;真实986sinen. (数学)正弦987sinecuren. 挂名差事,闲职988sinewn. 腱,力量,精力989sinewyadj. 多腱的,强壮有力的990sinfula. 有罪的,罪孽深重的991singv.唱,演唱992singaporen. 新加坡;新加坡人993singev. (轻微地)烧焦,烫焦994singern.歌唱家,歌手995singingn. 唱歌996singlea.单一的;独身的997singlenessn. 单一,单独,独身998singletreen. 系曳绳的横木999singulara.异常的,奇异的1000singularityn. 卓越,奇异1001singularlyad.不可思议地,少见地1002sinisteradj. 不吉祥的,险恶的1003sinkn.(厨房内的)洗涤槽1004sinkern. 使下沉的人,锤子,开凿工人1005sinkingn.下沉;沉没;投资1006sinlessa. 无罪的,清白的1007sinnern. 罪人,不知礼仪的人,无赖1008sinuousadj. 蜿蜒的,迂回的1009sinusn. 窦,静脉窦,湾,下陷或凹下去的地方1010sipv. 啜饮1011siphonn. 虹吸1012sirn.先生,阁下;…爵士1013siren. 陛下,殿下,父1014sirenn.汽笛,警报器1015sirloinn. 牛的上部腰肉1016siroccon. 从非洲吹向南欧一带的非洲热风, 1017sirrahn. 小子1018sirupn. 糖浆,糖蜜1019sisn. ((口语))小姐1020sissyn. 女孩子,女人般的男人,胆小无用的男子1021sistern.姐、妹1022sisterhoodn. 姊妹关系,姊妹之谊,妇女团体1023sisterlya. 姊妹一般的,象姊妹的1024sitv.坐1025siten.地点,地基;场所1026sittingadj. 坐着的;n. & a. 坐,就坐1027situatev. 位于,坐落在;使处于1028situateda.位于…的1029situationn.位置;处境;形势1030sixnum.六1031sixpencen. 六便士银币,六便士1032sixteennum. 十六;十六个1033sixteenthnum. 第十六,十六分之一1034sixthnum.第六;六分之一1035sixtiethnum. 第六十,六十分之一1036sixtynum.六十1037sizablea. 相当大的,大小相当的1038sizen.尺寸,大小1039sizzlern. 炎热天气,大热天1040skatev.滑冰1041skatern. 溜冰者1042skatingn. 滑冰,溜冰;滑冰的1043skeinn. 一束(线或纱)1044skeletala. 骨骼的,骸骨的1045skeletonn.骨骼,骷髅;骨架1046skepticn. 怀疑者1047skepticaladj. 怀疑的1048skepticismn. 怀疑态度1049sketchn.略图;速写;概略1050sketchyadj. 概略的,粗略的1051skew偏斜;adj. 不直的,歪斜的1052skewern. (烤肉用的)串肉杆v. 用杆串好1053skin.滑橇vi.滑雪1054skidvt. 刹住,滚滑1055skiern. 滑雪者1056skiffn. 轻舟,小船1057skiingn. 滑雪;滑雪运动1058skilfula. 精巧的;熟练的;灵巧的1059skilln.技能,技巧;熟练1060skilleda.有技能的,熟练的1061skilletn. 煎锅1062skillfula.灵巧的,娴熟的1063skimvt.掠过,擦过;略读1064skimmern. 撇取浮皮的器具,大略阅读的人, 1065skimming漏税,剔除1066skimpv. 节省花费,吝啬1067skimpyadj. 吝啬的,贫乏的1068skinn.皮,皮肤1069skinflintn. 吝啬鬼1070skinnyadj.极瘦的1071skipvi.跳,蹦vt.跳过1072skippern. 船长,主将,正驾驶1073skirmishn. 小战,小争吵1074skirtn.女裙1075skittishadj. <马等>容易受惊的,容易惊恐的1076skulduggeryn. 舞弊,作假1077skulkn. 躲藏,偷偷摸摸地走1078skulln. 头盖骨,脑壳1079skunkn. 臭鼬,黄鼠狼1080skyn.天空1081skyeya. 天空的,天蓝色的,高达天际的, 1082skylarkn. 云雀,发疯般的胡闹1083skylinen. 天涯,地平线,以天空为背景的轮廓1084skyrocketv. 陡升,猛涨1085skyscrapern.摩天楼1086slabn. 厚板,厚块1087slacka.萧条的;懈怠的1088slackenv. (使)松弛,放松1089slackern. 逃避工作的人,懒虫1090slagn. 炉渣,矿渣1091slainslay的过去分词1092slakev. 解渴,消渴1093slamvt.使劲关,砰地放下1094slandern.&vt.诽谤,诋毁1095slanderousadj. 诽谤的,中伤的1096slangn.俚语;行话,黑话1097slantvi.倾斜1098slapvt.掴,拍n.巴掌,拍1099slapdashadj. 草率的,马虎的1100slashvt.vi. 猛砍,乱砍1101slatn. 条板,金属板1102slaten. 石板,候选人名单v. 提名1103slatternadj. 不整洁的1104slaughtervt.&n.屠杀,屠宰1105SlavAdj.斯拉夫人的1106slaven.奴隶1107slaveholdern. 奴隶所有者1108slaverv. 流口水,渴望n. 口水1109slaveryn.奴隶制度;苦役1110Slavicadj. 斯拉夫人1111slavisha. 奴隶的,奴性的,奴隶根性的,1112slayv. 杀,残杀1113slayern.杀人者1114sleazeadj. 质地薄的;粗糙的1115sleazya. 质地薄的,没有内容的,廉价的1116sledn. 雪撬,小雪撬1117sledgen. 雪橇,大锤1118sledgehammern. 长柄大锤1119sleekv. (使)光滑,adj. 光滑的,整洁的1120sleepv.&n.睡,睡眠1121sleepern. 睡眠者,枕木,卧铺1122sleepilyad. 瞌睡地;懒散地1123sleepinessn. 想睡1124sleepingn. & a. 睡(眠)着(的)1125sleeplessa. 不睡眠的,睡不着的,不休息的1126sleeplessnessn.失眠1127sleepya.想睡的;寂静的1128sleetn. 雨夹雪1129sleeven.袖子,袖套1130sleevelessa. 无袖的1131sleighn. 雪撬1132sleightn. 巧妙手法,巧计,灵巧(分割1133slendera.细长的;微薄的1134sleptsleep的过去式(分词);睡1135slewslay的过去式;v. (使)旋转;n. 大量许多1136slicen.薄片,切片;部分1137slicka. 光滑的,熟练的,聪明的,平凡的,1138slidslide的过去分词1139slidevi.滑动1140sliding可调整的1141slighta.细长的;轻微的1142slightlyadv. 轻微地;轻蔑地;略微地;稍微,有点;细长的;轻轻地1143slima.细长的;微小的1144slimen. 黏液1145slimyadj. 泥泞的,令人讨厌的1146slingv. 投掷,扔,n. 吊腕带,吊索1147slinkv. 偷偷走动1148slipvt.&vi.(使)滑动1149slippage滑动,打滑,下降,延期1150slippern.拖鞋,便鞋1151slipperyadj. 滑的;使人滑跤的;不稳固的;不稳定的;滑溜的,狡猾的,不可靠的1152slipshoda. 破烂的,马虎的,潦草的1153slitvt.切开n.狭长的切口1154slitherv. (蛇)滑动,扭动前进1155slivern. 长条,细片,v. 裂成细片1156slobbern. 口水;v. 流口水,粗俗地表示1157slogann.标语,口号1158sloopn. 小帆船1159slopn. 外衣,工作服,泥浆,污水1160slopen.倾斜;斜面vi.倾斜1161slopinga.倾斜1162sloppyadj. 邋遢的,不整洁的1163slotn. 水沟,细长的孔,硬币投币口,1164slothn. 懒惰,树懒(一种动物)1165slothfula. 懒惰的1166slouchn. 没精打采的样子,耷拉,笨人1167sloughn./v. (蛇等)蜕皮,蜕壳1168slovenn. 不修边幅的人1169slovenlyadj. 不整洁的,马虎的1170slowa.慢的;迟钝的1171slowdownn. 放慢,迟缓;怠工1172slowlyadv. 慢慢地;缓慢地;减速地,adj. 慢慢地1173sludgen. 软泥,泥泞,泥状雪1174sluev. (使)旋转1175slugn. 鼻涕虫,懒汉,子弹,金属小块1176sluggardn. 懒鬼1177sluggishadj. 行动迟钝的,缓慢的1178sluicen. 水门,水闸,n. 冲洗,奔流1179slumn.贫民窟1180slumbern.睡眠;沉睡状态1181slumberousadj. 昏昏欲睡的1182slumpn./v. 猛然落下,暴跌,萧条1183slurv. 含糊不清地讲1184slushn. 烂泥,雪水。

1、一般来说,s在元音或浊辅音后读[z},在清辅音后面读成[s],在[t]后与[t]在一起读成[ts],在[d]后与[d]一起读成[dz]。

cups 杯子days 日子hands 手hats 帽子2、以s,sh,ch,x结尾的词在词尾加-es,读[iz]classes 班级buses 公共汽车boxes 盒子watches 手表3、以“元音字母+y”结尾的词,加-s,读作[z];以辅音字母+y结尾的词,变y为i,再加-es,读[iz]。

boy-boys 男孩army-armies 军队story-stories 故事factory-factories 工厂baby-babies 宝贝4、以o结尾的词,多数加-s,读[z]。

kilo-kilos 公里photo-photos 照片tobacco-tobaccos 烟草piano-pianos 钢琴以元音字母+o结尾的词一律加-s,读[z]。

zoo-zoos 动物园radio-radios 收音机少数以o结尾的词,在词尾加-es,读[z]。

tomato-tomatoes 西红柿hero-heroes 英雄Negro-Negroes 黑人potato-potatoes 土豆5、以f或fe结尾的词,多数把f,fe变为v,再加-es,读[s]。

leaf-leaves 树叶thief-thieves 小偷wife-wives 妻子knife-knives 小刀shelf-shelves 架子6、不规则名词的复数形式。

(1)、通过变化单词内部元音字母,构成复杂形式。

man-men 男子woman-women 女人foot-feet 脚goose-geese 鹅tooth-teeth 牙齿mouse-mice 老鼠child-children 小孩(2)、单数形式与复数形式相同sheep-sheep 绵羊deer-deer 鹿Chinese-Chinese 中国人Japanese-Japanese 日本人规则的名词复数形式一般是在单词后加-s 或-es。

s的用法和意思一、概述s是一个汉字拼音的缩写,常常在中文社交媒体和文字聊天中使用。

它有多种含义和用法,可以表示感叹、赞美、羡慕等情绪,并且具有口语化的特点。

以下将详细介绍s的各个用法和意思。

二、表示赞美或羡慕1. “s”这个简短的字母组合经常被用来表示对某人或事物赞美或羡慕的情感。

它源自英语单词“super”的首字母,表达了超强、超级之意。

2. 比如,在朋友圈看到一张漂亮的照片,我们可以回复“s啦”,表达对照片主人外貌出众的羡慕之情;看到他人取得巨大成功时,也可以用“s”来表示对其成就向往的赞扬。

3. s还可作为名词使用。

例如,“她真是一个大s”,指某女性外表极其出众;“他是个学霸, 是学校里最大的“s””。

三、表达惊叹或突然觉醒1. 有时候, 我们可能会听到一些令人印象深刻的事情,或者突然意识到一些重要的问题。

这个时候,我们可以用“s”来表达我们的惊讶或突然觉醒。

2. 比如,在听到朋友讲述了一个令人难以置信的经历后,我们可能会回复“s了个啥”,表示对故事中发生的事情感到吃惊;当我们才意识到自己疏忽了一件重要的事情时,也可以用“s”来表达自己突然想起来了。

四、其他用法1. “s”有时也可以表示歉意。

比如在网络聊天中,如果我们打错字,或者说错话了,可以使用“sry”(sorry的简写)来表达道歉之情。

2. 另外,“s”还有一种调侃或幽默的用法。

当我们看到某人做出滑稽、笑料十足的举动时,可以回复“笑死我了, s”,表示被逗乐了。

五、总结总之,“s”的用法和意思在不同场景下具有多样性。

除了表示赞美和羡慕外,它还可用于表示惊叹、突然觉醒、歉意或幽默等方面。

作为一种极富表现力和口语化特点的表达方式,“s”在中文社交媒体和文字聊天中得到了广泛应用。

无论是夸赞朋友的外表,还是展现自己对事物的惊叹,都可以巧妙地运用“s”,让沟通更加生动有趣。

1 什么是S 参数S 参数是散射参数S 参数的原文名称是“Scattering-Parameter”以二端口网络为例,如单根传输线,共有四个S 参数:S11,S12,S21,S22,对于互易网络有S12=S21,对于对称网络有S11=S22,对于无耗网络,有S11S11S21S21=1,即网络不消耗任何能量,从端口1 输入的能量不是被反射回端口 1 就是传输到端口2 上了。

在高速电路设计中用到的微带线或带状线,都有参考平面,为不对称结构(但平行双导线就是对称结构),所以S11 不等于S22,但满足互易条件,总是有S12=S21。

假设Port1 为信号输入端口,Port2 为信号输出端口,则我们关心的S 参数有两个:S11 和S21,S11 表示回波损耗,也就是有多少能量被反射回源端(Port1)了,这个值越小越好,一般建议S110.7,即-3dB,如果网络是无耗的,那么只要Port1 上的反射很小,就可以满足S210.7 的要求,但通常的传输线是有耗的,尤其在GHz 以上,损耗很显著,即使在Port1 上没有反射,经过长距离的传输线后,S21 的值就会变得很小,表示能量在传输过程中还没到达目的地,就已经消耗在路上了。

对于由2 根或以上的传输线组成的网络,还会有传输线间的互参数,可以理解为近端串扰系数、远端串扰系统,注意在奇模激励和偶模激励下的S 参数值不同。

需要说明的是,S 参数表示的是全频段的信息,由于传输线的带宽限制,一般在高频的衰减比较大,S 参数的指标只要在由信号的边缘速率表示的EMI 发射带宽范围内满足要求就可以了。

from 微波仿真论坛vK v4g eI S11:端口2 匹配时,端口1 的反射系数S22:端口1 匹配时,端口2 的反射系数S12:端口 1 匹配时,端口 2 到端口1 的反向传输系数S21:端口 2 匹配时,端口 1 到端口 2 的正向传输系数2 什么是Z 参数Z 参数是阻抗参数3 什么是smith 圆图史密斯圆图是由很多圆周交织在一起的一个图。

Mergers & InquisitionsSales & Trading vs. Investment Banking – Part 2 – On the JobIntroductionBrian: Welcome back to our second podcast in this series on sales and trading versus investment banking. This is Brian from Mergersand Inquisitions. I’m here with Jerry, who has been contributingto the site and helping me with some projects behind thescenes.He has worked in sales and trading at two bulge bracketinvestment banks before and then started his own prop tradingfirm, so he has quite a lot of experience in the realm of salesand trading.In the previous podcast, we spoke about the recruiting processfor both investment banking and sales and trading, and how itdiffers depending on what you’re going for, what type of firmyou’re going after, how you network, how you write yourresume, and how interviews are different for these two differentfields.This time around, we’re going to be going into what it’s actuallylike on the job, what it’s actually like to work in both investmentbanking and sales and trading, how you get assigned to groups,how you interact with your co-workers, how working in Asia ordifferent parts of the world is a bit different, and finally, careerpaths, exit opportunities, and what’s available for you in thefuture if you decide to go into one of these industries.To kick off this discussion and to get started here, people knowa lot about the training programs in investment banking. Onceyou actually get a full time offer, there’s a lot of knowledge aboutwhat you learn in training. It’s a lot of accounting, financialmodeling, valuation – those types of skills.What is the training program like in sales and trading? Let’s sayyou’ve gotten an offer and you’re about to start working. Howwould your firm actually go about training you?Sales & Trading Training Programs & Group Assignments/Jerry: Let me talk first about how investment banks would train their traders. Since a trader, like an investment banker, is consideredfront office staff of an investment bank, if this investment bankhas a global training program – usually American investmentbanks will have a two month training program for all their newhires all over the world. They all go to New York and get twomonths of training. If it’s in Europe, then it might be in London.That just covers a wide variety of basic financial concepts.After that, the trader will go back to their trading desk whereverthey’re based. Then they’ll get training directly from theirmanager. This is where you can get some variation on how thisworks.Some traders – they’re able to start trading real money on thevery first day, although, on a smaller budget, they’re only able totrade a small amount of money.Some traders – they have to trade with either fake money or nottrade at all for a long time. It may be for three to six months oreven longer.Basically, the way that trading is different from investmentbanking is you really can’t learn trading just by studying itwhereas in investment banking, you can learn modeling bybuilding models in class or on your own.In trading, the psychology of trading fake money and thepsychology of trading of real money is totally different becauseyou might get really excited or nervous when trading actualmoney. The only real way to learn trading well is to actually dothe trading.Basically, your manager will try to ease you into the position byfirst letting you trade with mock money and then letting youtrade with a small amount of real money, and then increasingthe amount of money that you trade. Basically, you learn bydoing.Brian: That’s really interesting because I know that the process is alittle different but I didn’t realize that with trading, there’s muchmore of that element of training once you get back to your realdesk, your real group, and once you start working./I know for banking, they don’t really do that too much. They kindof just throw you into the fire and say, “We have to do a pitchbook, we have to do a deal. Figure out what to do and do it,” butthey don’t really give you any training wheels. It’s a little differentin that respect.You brought up an interesting point, which is that in trading, youstart off with smaller amounts of money, or perhaps in thebeginning with nothing at all while you’re learning the ropes, andthen move up to trading larger amounts.How does that process work exactly? I’ve heard before thatthere are junior traders and then actual real traders. How arethey different? How do you move from a junior trader role up tosomeone who’s making more significant trades, let’s say? Jerry: This varies widely among different investment banks, andobviously among the different types of financial institutions thatconduct trading. Some investment banks will have a differencebetween junior traders and senior traders.Some banks will not use titles like this at all. Basically, you’llhave the same title for a couple of years but the amount ofmoney that you’ll be trading will gradually increase as time goeson.If you’re at an investment bank, you prove that you’re able tocontrol risk well and that you don’t panic when the market goescrazy. If you’re able to steadily make money, then the bank willincrease the amount of risk you’re able to take and the amountof money you’re able to trade with.This is also similar at a hedge fund or a proprietary trading firm.You’ll start out with a smaller amount of money. Such firmsmight have more simplistic rules for increasing the amount ofmoney that you’re able to trade.For example, at a proprietary trading firm, they might just say,“Okay, if you make over X amount of money per month for anumber of months in a row, then your trading budget will be Y.The risk you’ll be able to take will be Z.” The set of rules and theamount you’re able to trade is evaluated differs by organization./Brian: Okay, I see. Once you’ve gone through the training process and it’s time to actually pick which desk you’re working at for tradingfor example, how does this process actually work?I’m assuming that if you do an internship, and you work on aparticular desk, then you’ll probably go back to it but let’s saythat you haven’t worked at that bank before, let’s say you’re newto it. How would they actually assign you to a particular group orto a particular desk in trading?Jerry: Most financial institutions will actually hire you directly to work ina specific area in trading. For example, before you even enterthe firm, it will be decided that, okay, you will be doing credittrading or you will be doing rates trading.There might be some firms that just hire somebody as a traderand then let them do a rotation in each of the different tradingdesks, and finally let them settle down at one desk, but that ispretty rare nowadays. You might get a chance to rotate aroundthe different trading departments if you’re an intern, but as a full-time hire, that’s less likely.A Day in the Life of a TraderBrian: Okay, I see. We’ve covered the training program, how thatworks, and how you actually get assigned to groups. One reallycommon question I get is: What do you actually do once you’vestarted working? You’re past the training phase, to kind of gothrough a day in the life of both a trader and a banker.There’s a lot of content on the site already about a day in the lifeof an investment banker. I guess the way I’d summarize it, incase you haven’t read it already, is that the days are veryrandom. Generally, you’re going to start off working maybe eightor nine, 9:30 in the morning.Usually, mornings are not too active. Afternoons are actually nottoo active in investment banking. You might have meetings, youmight have calls with companies, you might be doing randomtasks and such, but actually what typically happens is that at theend of the day, or at least, the end of the day for the seniorbankers, they all pack up, leave, and go home.They drop a bunch of work on your desk and say, “Okay,analyst or associate, here’s what has to get done by tomorrow/morning.” They just expect that you’re going to stay there andwork on it until it gets done. Actually most of the time, you’redoing the bulk of your work at night.This is mostly true in the U.S. I know that in other regions it’s abit different. The lifestyle and hours can be a bit different, thework style can be different but this is what I would say iscommon at large investment banks, in the U.S. anyway.For trading, we’ve discussed before, in the first podcast, how it’sa little different in that the trader is very, very busy during markethours but to go into more detail on that, what would you say theaverage day in the life of a trader is like?Jerry: Sure. Why don’t I take the most typical example of a proprietary trader working for an investment bank in New York doingregular stock trading? The trader would probably get up in themorning, about two or three hours before the market opens, andget to the firm maybe one to one and a half hours before themarket opens.There would be usually a morning meeting where all the tradersget together. It might be in a separate room or it might just be onthe trading floor itself where everyone pulls their chairs together.The traders from the different markets will talk to each otherabout what they think the movements will be today andsummarize the movements from the previous day so that wayeveryone has a better idea of what the markets will do today,since each market tends to influence the other markets.For example, movements in the stock market might affect themovements in the credit market. Then, during market hours – inNew York, at 9:30 a.m. – the stock market would open and thetrader would have to be monitoring the market at all times.This actually makes it a little difficult to go to the bathroomsometimes. It might be difficult to take a lunch break if themarket is especially busy on a certain day. There is alwayspressure to be constantly monitoring the market while themarket is open.A trader will monitor the market and, if a good opportunitycomes up, will make a couple of trades, and will also talk with/brokers if it’s a market that involves brokers, and try to get more information from them.If they have traders both internally and traders at other firms that they’re friends with, they might make a couple of calls, and try to get more information on the markets. They’ll just keep on doing that until the market close.After the market close, the trader will have to work on wrapping up the trades for the day. If it’s a normal stock market, then most all of the settlement is either automated or taken care of by the middle and back office.If it’s an over-the-counter market, like for example credit default swaps, then the trader might have to spend some time wrapping up the trades, making sure they’re all settled properly, calling operations and back office to make sure the trades are booked correctly.Then the trader might spend some time analyzing stocks, preparing for the next market day, analyzing the trades they did for that day. Maybe after some analysis, they realize they need to rebalance their portfolio of stocks.Then they’ll know that the next day they need to, for example, increase their allocation to a certain industry. They might even build simulations of stock trades – different sorts of analysis might occur later in the day.There tends to be a trend where traders who make a lot of money actually work less and traders who are not making as much money work more because, even if the traders who make a lot of money don’t work that hard, there’s no way they’re going to get fired because the bank knows that they’re bringing in a lot of dough for the bank.Also they know they’re going to get a big bonus just because they made a lot of money. The traders who aren’t making money are freaking out because they know that they might get fired if they don’t make money sometime soon.That’s a basic wrap-up of what a typical day in the life of a trader is like./Brian: Interesting. Just a few questions on that because I’m actually kind of curious because I’ve seen a few trading firms but haven’treally worked there at all. You mentioned the middle of the daythat it can be hard to take a bathroom break for example.This may sound like a stupid question, but sometimes thingscome up during the middle of the day – personal errands, or youhave to visit the doctor, or something like that.With banking, it’s usually fine to step out for an hour in themiddle of the day if nothing important is going on becausechances are, you can just give work to someone else or itdoesn’t need to be done right this moment but obviously it’sdifferent in trading.Just logistically, let’s say that you have some kind of personalerrand in the middle of the day. For something like that, howwould you deal with it? Could you do anything?Jerry: The most common way to deal with a problem like that is just to ask a colleague to help monitor your positions while you’regone. It would be very dangerous in most situations if you justleft your portfolio there and the market is still moving, andnobody is looking at it.Let’s say one of the companies that you invested in or that youhold stock in suddenly goes bankrupt or announces somethingcrazy, and you’re not there at the desk to take care of thatsituation, then that could result in huge losses for the firm in avery short amount of time, so you need to get somebody to lookat your positions for you.Brian: I see. You mentioned that if you step away, somethingdisastrous could happen because of the volume of money thatyou’re trading here. I know this varies a lot by groups andbanks, and different trading strategies, but on average, whatsize trades are we usually talking about here?People who are day trading might be trading hundreds orthousands of dollars for example, but I’m assuming that it’s waybigger than that at banks. Are we talking about tens ofthousands, hundreds of thousands, millions of dollars in singletrades?/Jerry: It depends a lot in the market that you’re working in. Forexample, I worked mostly in credit trading – the size of mosttrades ranged from about five million dollars notional to about$20 million notional.If you were trading stocks, as a junior trader you might betrading notional amounts of trades in the millions in your firstyear of trading. Something like hundreds of millions of dollars instock? Well, that’s not going to happen in your first year oftrading. I’m talking about the notional amounts for single trades.As a day trader for a proprietary trading firm, in your first year,most of your trades will be under one million dollars. When Iwas running my own proprietary trading firm, a lot of traders inthe very beginning got about $50,000 worth of buying power.That increased more to $500,000 and a million after a couplemonths on the job.Brian: Okay, definitely a completely different scale from what people in their bedrooms trading on E*TRADE are dealing with on a dailybasis. You went over the day in the life of a trader, what youmight expect. The bottom line is it sounds like you’re workingmaybe 12 or so hours per day. Would you say that is accurate? Jerry: Yes, I would say that’s a pretty good average for a lot of traders, both at investment banks and hedge funds. Since market hoursare a couple hours less than that, you only need a few hoursbefore the market opens and a few hours after the marketcloses to wrap up your trades.Then you can leave – unlike investment banking where rightbefore you try to leave the firm, you might get a ton of workdumped on your desk at that moment. The work hours everyday are usually pretty constant.Sometimes you might have to stay late if there’s a specific typeof analysis that you want to do, and you want to get somethingready for a big announcement that’s coming out the next day.Or if you’re the type of trader that has to work with thesalespeople to make trades directly with clients, you might haveto work indirectly with a client that’s in a different time zone.That might make you stay later at work but most of the cases,it’s pretty normalized, the work hours./Brian: It sounds like the bottom line is you would expect maybe a 60 hour work week for sales and trading whereas investmentbanking is really all over the map, but I would say expect maybe80 to 100 hours on average with a lot of unpredictability.It’s completely unlike trading. You might have a day where yougo home at 7:00 p.m. and the next day you might have to pullan all-nighter for no apparent reason.You brought up an interesting point there with the possibility ofhaving to work with the salespeople. When you went throughthe average day in the life of a trader, you talked about howyou’re monitoring the market, you’re looking at newsbeforehand, you’re planning the day after the market closes,and then you’re making trades during the day.How much interaction is there with the sales force? What do youhave to work on together with them?Jerry: This depends on what kind of trader you are. If you’re a purely proprietary trader, which means that you take the firm’s moneyand then you use that money to trade purely for speculativeprofit, then you don’t really deal with salespeople.If you’re, let’s say, a flow trader or an agency trader – a flowtrader means that you need to trade with clients. There is a flowof clients that comes to the bank.For example, a client might want to buy a credit default swap onMicrosoft, or maybe the client is trying to hedge risk onMicrosoft so you would need to sell a Microsoft credit defaultswap to that client. If you don’t like the risk of that, maybe youwould take an opposite trade in the market to hedge out thatrisk.Depending on what type of trader you are, you might have zerointeraction with the sales force, or you might be interacting withthem all day long. It really depends on the type of trading. Brian: Essentially what happens is that the client would come to the salesperson, and they would say, “I want to buy X, Y, and Zsecurities.” Then they would come to you and say, “Can youhelp me make the trade for this, and can you actually get this forthe client?”/Jerry: Exactly. If the trader says, “No, there’s no way we can take that sort of position. We don’t want to make that trade with theclient,” then the client might be upset so the investment bankwill try to make the client happy by trying to execute mosttrades.If the risk is way too big and the trader doesn’t want to do it,then yes, the trader might analyze the trade and say it’s notworth it for us to do this.Brian: During the day, we went through a sample day in the life of atrader but for the sales force, for anyone working in sales – andI know you’re not an expert because you were on the tradingside.But for sales, what I would imagine is that most of the day isprobably just spent calling clients, talking to them on the phone,trying to find new clients if that’s what your role involves. Is thatpretty accurate that basically they’re spending most of the dayon the phone?Jerry: Right. A large amount of time everyday is spent just callingclients and trying to give them information about the markets,and also, making recommendations for what they should buy orsell.If they’re really good at convincing, just like selling any otherproduct, they might convince the client to purchase, let’s say100 million shares of Microsoft.Then the client would execute that trade through the investmentbank. It’s generally accepted procedure for the client to placethe trade through the bank whose salesperson convinced themof the trade.Let’s say if a client listened to advice from Bank A and thenplaced the trade through Bank B. That would be really messedup and nobody would want to work with that client again – sothat’s the way it works.Salespeople also need to spend a lot of time making theirclients happy. This might mean sending Christmas cards andNew Year’s cards, taking them out to dinner and showing thema really good time, sending them birthday presents, stuff like this/to make sure that that client keeps on doing business with theinvestment bank.Brian: It’s like any sales job really. It sounds like it’s completelyrelationship-driven. If you’re more of a people person than ananalytical person, then maybe that’s a better fit for you.One other point I wanted to touch on here is just your interactionwith co-workers. For investment banking, I think at least if youwork at a large bank in, say, New York or London for example,it’s generally pretty hierarchical.What I mean by that is that other analysts will hang out witheach other, and associates to some extent – they are higher upthan you but you’re still at entry level.Beyond that, once you get up to the mid-level – VPs, seniorVPs, directors, and then finally MDs – generally as an analyst,you’re not going to have too much interaction with thembecause they’re busy trying to wine and dine clients and tryingto actually bring in business for the bank.You’re just crunching numbers and making presentations mostof the time so I would say really most of the co-workerinteraction on the investment banking side happens with yourother analysts.You’ll go to Starbucks, you’ll go out to eat, they’ll hang out afterwork, and you form a pretty close bond because they’re all inthe same position. It’s sort of like if you join a fraternity and youhave to go through hazing. That’s sort of what being in ananalyst program at an investment bank doing investmentbanking is like.What is it like on the trading side? Do you talk to your co-workers much during the day or are you just too focused on themarket?Sales & Trading Co-Worker InteractionsJerry: That’s a great question, Brian. It often depends on how focused you are on the market during the day. Some traders will becompletely absorbed in the market, especially if the market isvery volatile that day, and they won’t really be able to talk tomany people during market hours./However, trading well usually does require significant interaction mainly with other traders and to a lesser extent, with people the middle office and sales.The reason for the need for this interaction is because you need to understand how other markets are functioning since other markets might affect your market.If you’re working as an equity trader, you might talk with the options traders to figure out if a huge order in the options market is affecting the price of the stock for the option that is being traded.Another interaction you might have is with the risk department. If you want to make a really big trade or you want to buy a stock in a very risky company, then you might need to get approval first from the risk department. That might be a big argument or discussion as to whether or not you’re allowed to make that trade.In terms of hierarchy, trading is a lot more flat. One reason is because a junior trader might easily make more money than a senior trader just because they’re having a better month or year or because they’re actually more skilled.Unlike investment banking, some people are just born to do trading well and they can do it very well very quickly whereas other people might not do well even if they trade for years.If, let’s say, there’s the head of a trading department, they’re not going to be sitting in a corner office separated from everyone else because that would just make it very hard to trade trading ideas.When the market is moving very quickly, you don’t have time to walk over to a corner office, have a meeting, and then come back to the market and make a decision. You need to – bam, one, two, three – you need to make decisions right at that moment. Sometimes people yell if necessary. Everyone needs to be able to communicate with everyone else instantly. Sometimes the need for formality, to have slow meetings, that just doesn’t work for trading./Brian: Picturing the trading floor here, is it kind of like Boiler Roomwhere it’s very loud, people are always screaming at each otherand there’s always a lot of action going on? Are we talkingabout what is described in Liar’s Poker for example?Jerry: I would say both the movie Boiler Room and the book Liar’sPoker would slightly exaggerate what happens on most tradingfloors. That’s also because that book and that movie are slightlydated. Hopefully traders are a bit more civilized now and don’tthrow phones at the heads of interns like they did in Liar’sPoker.It’s true that things that can get quite hectic sometimes andpeople will be excited about the market. Everything is very time-sensitive. One trade placed one second earlier might make areally big difference before a rival firm makes a similar trade andpushes the market in one direction or the other.Definitely, there’s that aspect of attention and sometimes peopleyelling when necessary, but usually it’s not that crazy. It’s noteveryone screaming at each other all day long, everyday. It’snot like that.Brian: I guess that’s good to hear from the perspective of your health, although it does make it a little less interesting to not havepeople screaming at you all day.Another question on lifestyle here – and I’m partially responsiblefor this phrase getting popular – but we have to go to themodels and bottles question.For investment banking, some people are kind of obsessed withgoing out to clubs with their co-workers and getting a table.They’re paying $400 USD to get a table, get expensive alcohol,and sitting there and acting important at a club, which I think iskind of stupid.I did it a couple of times but I was not really that into it. Most ofthe going out with co-workers was more just going to bars,going to events, that kind of stuff. Not quite as much going toexpensive, high-end clubs, at least where I was on the WestCoast of the U.S.For trading though, how would you describe it? I know obviouslyyou were working in Japan so maybe it’s a little different, but/how would you describe the going out scene? Do you do muchwith your co-workers outside of work?Jerry: Going out with co-workers can be interesting, but most of it just involves going to bars or going to restaurants and chatting witheach other, just having a good time. The really interesting partcomes in when the brokers have to take the traders out for agood time.When the traders go out for a good time, they’re all paying outof their own pockets to have fun. When the broker takes thetrader out for a good time, the broker’s firm is paying for thegood time, so basically, the broker has the right – or you couldeven say the mandate – to spend a lot of money to make thistrader happy, to make sure that the trader spends a lot ofmoney on trades with the broker firm.The reason for this is because in markets that require a broker,which would be most over-the-counter markets, a trader canchoose to execute their trades through a selection of differentbrokerage firms.From one trade, a brokerage firm might make a brokerage feeof thousands of dollars. Obviously it makes sense for brokers tospend tons of money on taking traders out to have a good time.As an example, one of my friends from Stanford – who shallremain unnamed – and worked at a bulge bracket investmentbank in New York, once went out with a broker and three othertraders. They just had dinner and a couple nice wines and itturned out to be $15,000 for one night.A salesperson at the Tokyo branch of an American bulgebracket investment bank said he spent – usually when takingone client out to dinner at hostess clubs – they spent about$1,000 per night. That’s the salespeople taking the clients out todinner, not the brokers taking the traders out to dinner.Basically this culture of people taking their clients out to dinner,to hostess bars, and maybe to establishments even more shadythan hostess bars, this is a huge amount of expenditure beingspent at investment banks. I would say that’s probably thebiggest aspect of mottles and bottles for traders and forsalespeople./。