计量经济学导论(伍德里奇第三版)课后习题答案 CHAPTER 1

- 格式:doc

- 大小:1.55 MB

- 文档页数:57

第1章解决问题的办法1.1(一)理想的情况下,我们可以随机分配学生到不同尺寸的类。

也就是说,每个学生被分配一个不同的类的大小,而不考虑任何学生的特点,能力和家庭背景。

对于原因,我们将看到在第2章中,我们想的巨大变化,班级规模(主题,当然,伦理方面的考虑和资源约束)。

(二)呈负相关关系意味着,较大的一类大小是与较低的性能。

因为班级规模较大的性能实际上伤害,我们可能会发现呈负相关。

然而,随着观测数据,还有其他的原因,我们可能会发现负相关关系。

例如,来自较富裕家庭的儿童可能更有可能参加班级规模较小的学校,和富裕的孩子一般在标准化考试中成绩更好。

另一种可能性是,在学校,校长可能分配更好的学生,以小班授课。

或者,有些家长可能会坚持他们的孩子都在较小的类,这些家长往往是更多地参与子女的教育。

(三)鉴于潜在的混杂因素- 其中一些是第(ii)上市- 寻找负相关关系不会是有力的证据,缩小班级规模,实际上带来更好的性能。

在某种方式的混杂因素的控制是必要的,这是多元回归分析的主题。

1.2(一)这里是构成问题的一种方法:如果两家公司,说A和B,相同的在各方面比B公司à用品工作培训之一小时每名工人,坚定除外,多少会坚定的输出从B公司的不同?(二)公司很可能取决于工人的特点选择在职培训。

一些观察到的特点是多年的教育,多年的劳动力,在一个特定的工作经验。

企业甚至可能歧视根据年龄,性别或种族。

也许企业选择提供培训,工人或多或少能力,其中,“能力”可能是难以量化,但其中一个经理的相对能力不同的员工有一些想法。

此外,不同种类的工人可能被吸引到企业,提供更多的就业培训,平均,这可能不是很明显,向雇主。

(iii)该金额的资金和技术工人也将影响输出。

所以,两家公司具有完全相同的各类员工一般都会有不同的输出,如果他们使用不同数额的资金或技术。

管理者的素质也有效果。

(iv)无,除非训练量是随机分配。

许多因素上市部分(二)及(iii)可有助于寻找输出和培训的正相关关系,即使不在职培训提高工人的生产力。

第1章解决问题的办法1.1(一)理想的情况下,我们可以随机分配学生到不同尺寸的类。

也就是说,每个学生被分配一个不同的类的大小,而不考虑任何学生的特点,能力和家庭背景。

对于原因,我们将看到在第2章中,我们想的巨大变化,班级规模(主题,当然,伦理方面的考虑和资源约束)。

(二)呈负相关关系意味着,较大的一类大小是与较低的性能。

因为班级规模较大的性能实际上伤害,我们可能会发现呈负相关。

然而,随着观测数据,还有其他的原因,我们可能会发现负相关关系。

例如,来自较富裕家庭的儿童可能更有可能参加班级规模较小的学校,和富裕的孩子一般在标准化考试中成绩更好。

另一种可能性是,在学校,校长可能分配更好的学生,以小班授课。

或者,有些家长可能会坚持他们的孩子都在较小的类,这些家长往往是更多地参与子女的教育。

(三)鉴于潜在的混杂因素- 其中一些是第(ii)上市- 寻找负相关关系不会是有力的证据,缩小班级规模,实际上带来更好的性能。

在某种方式的混杂因素的控制是必要的,这是多元回归分析的主题。

1.2(一)这里是构成问题的一种方法:如果两家公司,说A和B,相同的在各方面比B公司à用品工作培训之一小时每名工人,坚定除外,多少会坚定的输出从B公司的不同?(二)公司很可能取决于工人的特点选择在职培训。

一些观察到的特点是多年的教育,多年的劳动力,在一个特定的工作经验。

企业甚至可能歧视根据年龄,性别或种族。

也许企业选择提供培训,工人或多或少能力,其中,“能力”可能是难以量化,但其中一个经理的相对能力不同的员工有一些想法。

此外,不同种类的工人可能被吸引到企业,提供更多的就业培训,平均,这可能不是很明显,向雇主。

(iii)该金额的资金和技术工人也将影响输出。

所以,两家公司具有完全相同的各类员工一般都会有不同的输出,如果他们使用不同数额的资金或技术。

管理者的素质也有效果。

(iv)无,除非训练量是随机分配。

许多因素上市部分(二)及(iii)可有助于寻找输出和培训的正相关关系,即使不在职培训提高工人的生产力。

伍德里奇计量经济学导论答案1、企业生产车间发生的固定资产的修理费应计入()科目。

[单选题] *A.制造费用B.生产成本C.长期待摊费用D.管理费用(正确答案)2、某企业2018年6月期初固定资产原值10 500万元。

6月增加了一项固定资产入账价值为750万元;同时6月减少了固定资产原值150万元;则6月份该企业应提折旧的固定资产原值为( )万元。

[单选题] *A.1 1100B.10 650C.10 500(正确答案)D.10 3503、企业购进货物用于集体福利时,该货物负担的增值税额应当计入()。

[单选题] *A.应交税费——应交增值税B.应付职工薪酬(正确答案)C.营业外支出D.管理费用4、.(年浙江省第一次联考)下列各项中,不属于会计核算的前提条件的是()[单选题] *A持续经营B货币计量C权责发生制(正确答案)D会计主体5、.(年浙江省第三次联考)下列项目中不需要进行会计核算的是()[单选题] *A签订销售合同(正确答案)B宣告发放现金股利C提现备发工资D结转本年亏损6、企业为扩大生产经营而发生的业务招待费,应计入()科目。

[单选题] *A.管理费用(正确答案)B.财务费用C.销售费用D.其他业务成本7、当企业接受投资人的投资时,对于投资者的出资超过其占企业注册资本份额的部分应通过()科目核算。

[单选题] *A.实收资本B.资本公积(正确答案)C.股本D.盈余公积8、企业生产车间使用的固定资产发生的下列支出中,直接计入当期损益的是( )。

[单选题] *A.购入时发生的安装费用B.发生的装修费用C.购入时发生的运杂费D.发生的修理费(正确答案)9、企业购入的生产设备达到预定可使用状态前,其发生的专业人员服务费用计入()科目。

[单选题] *A.“固定资产”B.“制造费用”C.“在建工程”(正确答案)D.“工程物资”10、固定资产报废清理后发生的净损失,应计入()。

[单选题] *A.投资收益B.管理费用C.营业外支出(正确答案)D.其他业务成本11、企业在使用固定过程中发生更新改造支出应计入()。

T his appendix derives various results for ordinary least squares estimation of themultiple linear regression model using matrix notation and matrix algebra (see Appendix D for a summary). The material presented here is much more ad-vanced than that in the text.E.1THE MODEL AND ORDINARY LEAST SQUARES ESTIMATIONThroughout this appendix,we use the t subscript to index observations and an n to denote the sample size. It is useful to write the multiple linear regression model with k parameters as follows:y t ϭ1ϩ2x t 2ϩ3x t 3ϩ… ϩk x tk ϩu t ,t ϭ 1,2,…,n ,(E.1)where y t is the dependent variable for observation t ,and x tj ,j ϭ 2,3,…,k ,are the inde-pendent variables. Notice how our labeling convention here differs from the text:we call the intercept 1and let 2,…,k denote the slope parameters. This relabeling is not important,but it simplifies the matrix approach to multiple regression.For each t ,define a 1 ϫk vector,x t ϭ(1,x t 2,…,x tk ),and let ϭ(1,2,…,k )Јbe the k ϫ1 vector of all parameters. Then,we can write (E.1) asy t ϭx t ϩu t ,t ϭ 1,2,…,n .(E.2)[Some authors prefer to define x t as a column vector,in which case,x t is replaced with x t Јin (E.2). Mathematically,it makes more sense to define it as a row vector.] We can write (E.2) in full matrix notation by appropriately defining data vectors and matrices. Let y denote the n ϫ1 vector of observations on y :the t th element of y is y t .Let X be the n ϫk vector of observations on the explanatory variables. In other words,the t th row of X consists of the vector x t . Equivalently,the (t ,j )th element of X is simply x tj :755A p p e n d i x EThe Linear Regression Model inMatrix Formn X ϫ k ϵϭ .Finally,let u be the n ϫ 1 vector of unobservable disturbances. Then,we can write (E.2)for all n observations in matrix notation :y ϭX ϩu .(E.3)Remember,because X is n ϫ k and is k ϫ 1,X is n ϫ 1.Estimation of proceeds by minimizing the sum of squared residuals,as in Section3.2. Define the sum of squared residuals function for any possible k ϫ 1 parameter vec-tor b asSSR(b ) ϵ͚nt ϭ1(y t Ϫx t b )2.The k ϫ 1 vector of ordinary least squares estimates,ˆϭ(ˆ1,ˆ2,…,ˆk ),minimizes SSR(b ) over all possible k ϫ 1 vectors b . This is a problem in multivariable calculus.For ˆto minimize the sum of squared residuals,it must solve the first order conditionѨSSR(ˆ)/Ѩb ϵ0.(E.4)Using the fact that the derivative of (y t Ϫx t b )2with respect to b is the 1ϫ k vector Ϫ2(y t Ϫx t b )x t ,(E.4) is equivalent to͚nt ϭ1xt Ј(y t Ϫx t ˆ) ϵ0.(E.5)(We have divided by Ϫ2 and taken the transpose.) We can write this first order condi-tion as͚nt ϭ1(y t Ϫˆ1Ϫˆ2x t 2Ϫ… Ϫˆk x tk ) ϭ0͚nt ϭ1x t 2(y t Ϫˆ1Ϫˆ2x t 2Ϫ… Ϫˆk x tk ) ϭ0...͚nt ϭ1x tk (y t Ϫˆ1Ϫˆ2x t 2Ϫ… Ϫˆk x tk ) ϭ0,which,apart from the different labeling convention,is identical to the first order condi-tions in equation (3.13). We want to write these in matrix form to make them more use-ful. Using the formula for partitioned multiplication in Appendix D,we see that (E.5)is equivalent to΅1x 12x 13...x 1k1x 22x 23...x 2k...1x n 2x n 3...x nk ΄΅x 1x 2...x n ΄Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form756Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix FormXЈ(yϪXˆ) ϭ0(E.6) or(XЈX)ˆϭXЈy.(E.7)It can be shown that (E.7) always has at least one solution. Multiple solutions do not help us,as we are looking for a unique set of OLS estimates given our data set. Assuming that the kϫ k symmetric matrix XЈX is nonsingular,we can premultiply both sides of (E.7) by (XЈX)Ϫ1to solve for the OLS estimator ˆ:ˆϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈy.(E.8)This is the critical formula for matrix analysis of the multiple linear regression model. The assumption that XЈX is invertible is equivalent to the assumption that rank(X) ϭk, which means that the columns of X must be linearly independent. This is the matrix ver-sion of MLR.4 in Chapter 3.Before we continue,(E.8) warrants a word of warning. It is tempting to simplify the formula for ˆas follows:ˆϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈyϭXϪ1(XЈ)Ϫ1XЈyϭXϪ1y.The flaw in this reasoning is that X is usually not a square matrix,and so it cannot be inverted. In other words,we cannot write (XЈX)Ϫ1ϭXϪ1(XЈ)Ϫ1unless nϭk,a case that virtually never arises in practice.The nϫ 1 vectors of OLS fitted values and residuals are given byyˆϭXˆ,uˆϭyϪyˆϭyϪXˆ.From (E.6) and the definition of uˆ,we can see that the first order condition for ˆis the same asXЈuˆϭ0.(E.9) Because the first column of X consists entirely of ones,(E.9) implies that the OLS residuals always sum to zero when an intercept is included in the equation and that the sample covariance between each independent variable and the OLS residuals is zero. (We discussed both of these properties in Chapter 3.)The sum of squared residuals can be written asSSR ϭ͚n tϭ1uˆt2ϭuˆЈuˆϭ(yϪXˆ)Ј(yϪXˆ).(E.10)All of the algebraic properties from Chapter 3 can be derived using matrix algebra. For example,we can show that the total sum of squares is equal to the explained sum of squares plus the sum of squared residuals [see (3.27)]. The use of matrices does not pro-vide a simpler proof than summation notation,so we do not provide another derivation.757The matrix approach to multiple regression can be used as the basis for a geometri-cal interpretation of regression. This involves mathematical concepts that are even more advanced than those we covered in Appendix D. [See Goldberger (1991) or Greene (1997).]E.2FINITE SAMPLE PROPERTIES OF OLSDeriving the expected value and variance of the OLS estimator ˆis facilitated by matrix algebra,but we must show some care in stating the assumptions.A S S U M P T I O N E.1(L I N E A R I N P A R A M E T E R S)The model can be written as in (E.3), where y is an observed nϫ 1 vector, X is an nϫ k observed matrix, and u is an nϫ 1 vector of unobserved errors or disturbances.A S S U M P T I O N E.2(Z E R O C O N D I T I O N A L M E A N)Conditional on the entire matrix X, each error ut has zero mean: E(ut͉X) ϭ0, tϭ1,2,…,n.In vector form,E(u͉X) ϭ0.(E.11) This assumption is implied by MLR.3 under the random sampling assumption,MLR.2.In time series applications,Assumption E.2 imposes strict exogeneity on the explana-tory variables,something discussed at length in Chapter 10. This rules out explanatory variables whose future values are correlated with ut; in particular,it eliminates laggeddependent variables. Under Assumption E.2,we can condition on the xtjwhen we com-pute the expected value of ˆ.A S S U M P T I O N E.3(N O P E R F E C T C O L L I N E A R I T Y) The matrix X has rank k.This is a careful statement of the assumption that rules out linear dependencies among the explanatory variables. Under Assumption E.3,XЈX is nonsingular,and so ˆis unique and can be written as in (E.8).T H E O R E M E.1(U N B I A S E D N E S S O F O L S)Under Assumptions E.1, E.2, and E.3, the OLS estimator ˆis unbiased for .P R O O F:Use Assumptions E.1 and E.3 and simple algebra to writeˆϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈyϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ(Xϩu)ϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1(XЈX)ϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈuϭϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈu,(E.12)where we use the fact that (XЈX)Ϫ1(XЈX) ϭIk . Taking the expectation conditional on X givesAppendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form 758E(ˆ͉X)ϭϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈE(u͉X)ϭϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ0ϭ,because E(u͉X) ϭ0under Assumption E.2. This argument clearly does not depend on the value of , so we have shown that ˆis unbiased.To obtain the simplest form of the variance-covariance matrix of ˆ,we impose the assumptions of homoskedasticity and no serial correlation.A S S U M P T I O N E.4(H O M O S K E D A S T I C I T Y A N DN O S E R I A L C O R R E L A T I O N)(i) Var(ut͉X) ϭ2, t ϭ 1,2,…,n. (ii) Cov(u t,u s͉X) ϭ0, for all t s. In matrix form, we canwrite these two assumptions asVar(u͉X) ϭ2I n,(E.13)where Inis the nϫ n identity matrix.Part (i) of Assumption E.4 is the homoskedasticity assumption:the variance of utcan-not depend on any element of X,and the variance must be constant across observations, t. Part (ii) is the no serial correlation assumption:the errors cannot be correlated across observations. Under random sampling,and in any other cross-sectional sampling schemes with independent observations,part (ii) of Assumption E.4 automatically holds. For time series applications,part (ii) rules out correlation in the errors over time (both conditional on X and unconditionally).Because of (E.13),we often say that u has scalar variance-covariance matrix when Assumption E.4 holds. We can now derive the variance-covariance matrix of the OLS estimator.T H E O R E M E.2(V A R I A N C E-C O V A R I A N C EM A T R I X O F T H E O L S E S T I M A T O R)Under Assumptions E.1 through E.4,Var(ˆ͉X) ϭ2(XЈX)Ϫ1.(E.14)P R O O F:From the last formula in equation (E.12), we haveVar(ˆ͉X) ϭVar[(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈu͉X] ϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ[Var(u͉X)]X(XЈX)Ϫ1.Now, we use Assumption E.4 to getVar(ˆ͉X)ϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ(2I n)X(XЈX)Ϫ1ϭ2(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈX(XЈX)Ϫ1ϭ2(XЈX)Ϫ1.Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form759Formula (E.14) means that the variance of ˆj (conditional on X ) is obtained by multi-plying 2by the j th diagonal element of (X ЈX )Ϫ1. For the slope coefficients,we gave an interpretable formula in equation (3.51). Equation (E.14) also tells us how to obtain the covariance between any two OLS estimates:multiply 2by the appropriate off diago-nal element of (X ЈX )Ϫ1. In Chapter 4,we showed how to avoid explicitly finding covariances for obtaining confidence intervals and hypotheses tests by appropriately rewriting the model.The Gauss-Markov Theorem,in its full generality,can be proven.T H E O R E M E .3 (G A U S S -M A R K O V T H E O R E M )Under Assumptions E.1 through E.4, ˆis the best linear unbiased estimator.P R O O F :Any other linear estimator of can be written as˜ ϭA Јy ,(E.15)where A is an n ϫ k matrix. In order for ˜to be unbiased conditional on X , A can consist of nonrandom numbers and functions of X . (For example, A cannot be a function of y .) To see what further restrictions on A are needed, write˜ϭA Ј(X ϩu ) ϭ(A ЈX )ϩA Јu .(E.16)Then,E(˜͉X )ϭA ЈX ϩE(A Јu ͉X )ϭA ЈX ϩA ЈE(u ͉X ) since A is a function of XϭA ЈX since E(u ͉X ) ϭ0.For ˜to be an unbiased estimator of , it must be true that E(˜͉X ) ϭfor all k ϫ 1 vec-tors , that is,A ЈX ϭfor all k ϫ 1 vectors .(E.17)Because A ЈX is a k ϫ k matrix, (E.17) holds if and only if A ЈX ϭI k . Equations (E.15) and (E.17) characterize the class of linear, unbiased estimators for .Next, from (E.16), we haveVar(˜͉X ) ϭA Ј[Var(u ͉X )]A ϭ2A ЈA ,by Assumption E.4. Therefore,Var(˜͉X ) ϪVar(ˆ͉X )ϭ2[A ЈA Ϫ(X ЈX )Ϫ1]ϭ2[A ЈA ϪA ЈX (X ЈX )Ϫ1X ЈA ] because A ЈX ϭI kϭ2A Ј[I n ϪX (X ЈX )Ϫ1X Ј]Aϵ2A ЈMA ,where M ϵI n ϪX (X ЈX )Ϫ1X Ј. Because M is symmetric and idempotent, A ЈMA is positive semi-definite for any n ϫ k matrix A . This establishes that the OLS estimator ˆis BLUE. How Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form 760Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Formis this significant? Let c be any kϫ 1 vector and consider the linear combination cЈϭc11ϩc22ϩ… ϩc kk, which is a scalar. The unbiased estimators of cЈare cЈˆand cЈ˜. ButVar(c˜͉X) ϪVar(cЈˆ͉X) ϭcЈ[Var(˜͉X) ϪVar(ˆ͉X)]cՆ0,because [Var(˜͉X) ϪVar(ˆ͉X)] is p.s.d. Therefore, when it is used for estimating any linear combination of , OLS yields the smallest variance. In particular, Var(ˆj͉X) ՅVar(˜j͉X) for any other linear, unbiased estimator of j.The unbiased estimator of the error variance 2can be written asˆ2ϭuˆЈuˆ/(n Ϫk),where we have labeled the explanatory variables so that there are k total parameters, including the intercept.T H E O R E M E.4(U N B I A S E D N E S S O Fˆ2)Under Assumptions E.1 through E.4, ˆ2is unbiased for 2: E(ˆ2͉X) ϭ2for all 2Ͼ0. P R O O F:Write uˆϭyϪXˆϭyϪX(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈyϭM yϭM u, where MϭI nϪX(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ,and the last equality follows because MXϭ0. Because M is symmetric and idempotent,uˆЈuˆϭuЈMЈM uϭuЈM u.Because uЈM u is a scalar, it equals its trace. Therefore,ϭE(uЈM u͉X)ϭE[tr(uЈM u)͉X] ϭE[tr(M uuЈ)͉X]ϭtr[E(M uuЈ|X)] ϭtr[M E(uuЈ|X)]ϭtr(M2I n) ϭ2tr(M) ϭ2(nϪ k).The last equality follows from tr(M) ϭtr(I) Ϫtr[X(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ] ϭnϪtr[(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈX] ϭnϪn) ϭnϪk. Therefore,tr(IkE(ˆ2͉X) ϭE(uЈM u͉X)/(nϪ k) ϭ2.E.3STATISTICAL INFERENCEWhen we add the final classical linear model assumption,ˆhas a multivariate normal distribution,which leads to the t and F distributions for the standard test statistics cov-ered in Chapter 4.A S S U M P T I O N E.5(N O R M A L I T Y O F E R R O R S)are independent and identically distributed as Normal(0,2). Conditional on X, the utEquivalently, u given X is distributed as multivariate normal with mean zero and variance-covariance matrix 2I n: u~ Normal(0,2I n).761Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form Under Assumption E.5,each uis independent of the explanatory variables for all t. Inta time series setting,this is essentially the strict exogeneity assumption.T H E O R E M E.5(N O R M A L I T Y O Fˆ)Under the classical linear model Assumptions E.1 through E.5, ˆconditional on X is dis-tributed as multivariate normal with mean and variance-covariance matrix 2(XЈX)Ϫ1.Theorem E.5 is the basis for statistical inference involving . In fact,along with the properties of the chi-square,t,and F distributions that we summarized in Appendix D, we can use Theorem E.5 to establish that t statistics have a t distribution under Assumptions E.1 through E.5 (under the null hypothesis) and likewise for F statistics. We illustrate with a proof for the t statistics.T H E O R E M E.6Under Assumptions E.1 through E.5,(ˆjϪj)/se(ˆj) ~ t nϪk,j ϭ 1,2,…,k.P R O O F:The proof requires several steps; the following statements are initially conditional on X. First, by Theorem E.5, (ˆjϪj)/sd(ˆ) ~ Normal(0,1), where sd(ˆj) ϭ͙ෆc jj, and c jj is the j th diagonal element of (XЈX)Ϫ1. Next, under Assumptions E.1 through E.5, conditional on X,(n Ϫ k)ˆ2/2~ 2nϪk.(E.18)This follows because (nϪk)ˆ2/2ϭ(u/)ЈM(u/), where M is the nϫn symmetric, idem-potent matrix defined in Theorem E.4. But u/~ Normal(0,I n) by Assumption E.5. It follows from Property 1 for the chi-square distribution in Appendix D that (u/)ЈM(u/) ~ 2nϪk (because M has rank nϪk).We also need to show that ˆand ˆ2are independent. But ˆϭϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈu, and ˆ2ϭuЈM u/(nϪk). Now, [(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ]Mϭ0because XЈMϭ0. It follows, from Property 5 of the multivariate normal distribution in Appendix D, that ˆand M u are independent. Since ˆ2is a function of M u, ˆand ˆ2are also independent.Finally, we can write(ˆjϪj)/se(ˆj) ϭ[(ˆjϪj)/sd(ˆj)]/(ˆ2/2)1/2,which is the ratio of a standard normal random variable and the square root of a 2nϪk/(nϪk) random variable. We just showed that these are independent, and so, by def-inition of a t random variable, (ˆjϪj)/se(ˆj) has the t nϪk distribution. Because this distri-bution does not depend on X, it is the unconditional distribution of (ˆjϪj)/se(ˆj) as well.From this theorem,we can plug in any hypothesized value for j and use the t statistic for testing hypotheses,as usual.Under Assumptions E.1 through E.5,we can compute what is known as the Cramer-Rao lower bound for the variance-covariance matrix of unbiased estimators of (again762conditional on X ) [see Greene (1997,Chapter 4)]. This can be shown to be 2(X ЈX )Ϫ1,which is exactly the variance-covariance matrix of the OLS estimator. This implies that ˆis the minimum variance unbiased estimator of (conditional on X ):Var(˜͉X ) ϪVar(ˆ͉X ) is positive semi-definite for any other unbiased estimator ˜; we no longer have to restrict our attention to estimators linear in y .It is easy to show that the OLS estimator is in fact the maximum likelihood estima-tor of under Assumption E.5. For each t ,the distribution of y t given X is Normal(x t ,2). Because the y t are independent conditional on X ,the likelihood func-tion for the sample is obtained from the product of the densities:͟nt ϭ1(22)Ϫ1/2exp[Ϫ(y t Ϫx t )2/(22)].Maximizing this function with respect to and 2is the same as maximizing its nat-ural logarithm:͚nt ϭ1[Ϫ(1/2)log(22) Ϫ(yt Ϫx t )2/(22)].For obtaining ˆ,this is the same as minimizing͚nt ϭ1(y t Ϫx t )2—the division by 22does not affect the optimization—which is just the problem that OLS solves. The esti-mator of 2that we have used,SSR/(n Ϫk ),turns out not to be the MLE of 2; the MLE is SSR/n ,which is a biased estimator. Because the unbiased estimator of 2results in t and F statistics with exact t and F distributions under the null,it is always used instead of the MLE.SUMMARYThis appendix has provided a brief discussion of the linear regression model using matrix notation. This material is included for more advanced classes that use matrix algebra,but it is not needed to read the text. In effect,this appendix proves some of the results that we either stated without proof,proved only in special cases,or proved through a more cumbersome method of proof. Other topics—such as asymptotic prop-erties,instrumental variables estimation,and panel data models—can be given concise treatments using matrices. Advanced texts in econometrics,including Davidson and MacKinnon (1993),Greene (1997),and Wooldridge (1999),can be consulted for details.KEY TERMSAppendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form 763First Order Condition Matrix Notation Minimum Variance Unbiased Scalar Variance-Covariance MatrixVariance-Covariance Matrix of the OLS EstimatorPROBLEMSE.1Let x t be the 1ϫ k vector of explanatory variables for observation t . Show that the OLS estimator ˆcan be written asˆϭΘ͚n tϭ1xt Јx t ΙϪ1Θ͚nt ϭ1xt Јy t Ι.Dividing each summation by n shows that ˆis a function of sample averages.E.2Let ˆbe the k ϫ 1 vector of OLS estimates.(i)Show that for any k ϫ 1 vector b ,we can write the sum of squaredresiduals asSSR(b ) ϭu ˆЈu ˆϩ(ˆϪb )ЈX ЈX (ˆϪb ).[Hint :Write (y Ϫ X b )Ј(y ϪX b ) ϭ[u ˆϩX (ˆϪb )]Ј[u ˆϩX (ˆϪb )]and use the fact that X Јu ˆϭ0.](ii)Explain how the expression for SSR(b ) in part (i) proves that ˆuniquely minimizes SSR(b ) over all possible values of b ,assuming Xhas rank k .E.3Let ˆbe the OLS estimate from the regression of y on X . Let A be a k ϫ k non-singular matrix and define z t ϵx t A ,t ϭ 1,…,n . Therefore,z t is 1ϫ k and is a non-singular linear combination of x t . Let Z be the n ϫ k matrix with rows z t . Let ˜denote the OLS estimate from a regression ofy on Z .(i)Show that ˜ϭA Ϫ1ˆ.(ii)Let y ˆt be the fitted values from the original regression and let y ˜t be thefitted values from regressing y on Z . Show that y ˜t ϭy ˆt ,for all t ϭ1,2,…,n . How do the residuals from the two regressions compare?(iii)Show that the estimated variance matrix for ˜is ˆ2A Ϫ1(X ЈX )Ϫ1A Ϫ1,where ˆ2is the usual variance estimate from regressing y on X .(iv)Let the ˆj be the OLS estimates from regressing y t on 1,x t 2,…,x tk ,andlet the ˜j be the OLS estimates from the regression of yt on 1,a 2x t 2,…,a k x tk ,where a j 0,j ϭ 2,…,k . Use the results from part (i)to find the relationship between the ˜j and the ˆj .(v)Assuming the setup of part (iv),use part (iii) to show that se(˜j ) ϭse(ˆj )/͉a j ͉.(vi)Assuming the setup of part (iv),show that the absolute values of the tstatistics for ˜j and ˆj are identical.Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form 764。

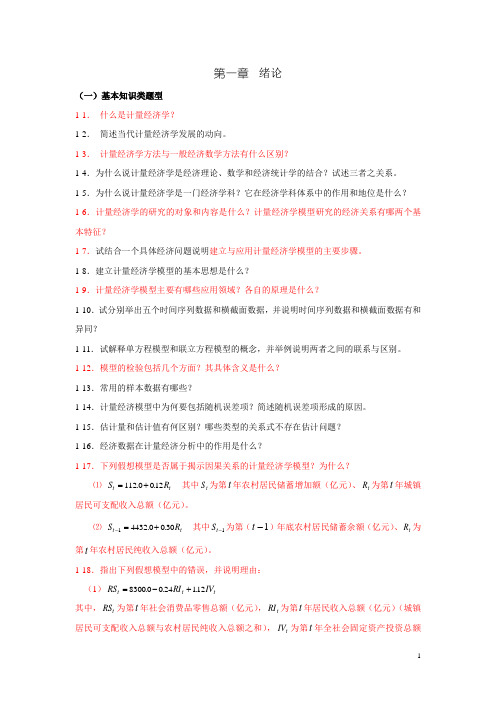

第一章 绪论(一)基本知识类题型1-1. 什么是计量经济学?1-2. 简述当代计量经济学发展的动向。

1-3. 计量经济学方法与一般经济数学方法有什么区别?1-4.为什么说计量经济学是经济理论、数学和经济统计学的结合?试述三者之关系。

1-5.为什么说计量经济学是一门经济学科?它在经济学科体系中的作用和地位是什么? 1-6.计量经济学的研究的对象和内容是什么?计量经济学模型研究的经济关系有哪两个基本特征?1-7.试结合一个具体经济问题说明建立与应用计量经济学模型的主要步骤。

1-8.建立计量经济学模型的基本思想是什么?1-9.计量经济学模型主要有哪些应用领域?各自的原理是什么?1-10.试分别举出五个时间序列数据和横截面数据,并说明时间序列数据和横截面数据有和异同?1-11.试解释单方程模型和联立方程模型的概念,并举例说明两者之间的联系与区别。

1-12.模型的检验包括几个方面?其具体含义是什么?1-13.常用的样本数据有哪些?1-14.计量经济模型中为何要包括随机误差项?简述随机误差项形成的原因。

1-15.估计量和估计值有何区别?哪些类型的关系式不存在估计问题?1-16.经济数据在计量经济分析中的作用是什么?1-17.下列假想模型是否属于揭示因果关系的计量经济学模型?为什么?⑴ S R t t =+1120012.. 其中S t 为第t 年农村居民储蓄增加额(亿元)、R t 为第t 年城镇居民可支配收入总额(亿元)。

⑵ S R t t -=+144320030.. 其中S t -1为第(1-t )年底农村居民储蓄余额(亿元)、R t 为第t 年农村居民纯收入总额(亿元)。

1-18.指出下列假想模型中的错误,并说明理由:(1)RS RI IV t t t =-+83000024112...其中,RS t 为第t 年社会消费品零售总额(亿元),RI t 为第t 年居民收入总额(亿元)(城镇居民可支配收入总额与农村居民纯收入总额之和),IV t 为第t 年全社会固定资产投资总额(亿元)。

第16章联立方程模型16.1 复习笔记解释变量另一种重要的内生性形式是联立性。

当一个或多个解释变量与因变量联合被决定时,就出现了这个问题。

估计联立方程模型的主要方法是工具变量法。

一、联立方程模型的性质联立方程组中的每个方程都具有其他条件不变的因果性解释。

因为只观察到均衡结果,所以在构造联立方程模型中的方程时,使用违反现存事实的逻辑。

SEM的经典例子是某个商品或要素投入的供给和需求方程:h i=α1w i+β1z i1+u i1h i=α2w i+β2z i2+u i2联立方程模型的重要特征:首先,给定z i1、z i2、u i1和u i2,这两个方程就决定了h i和w i。

h i和w i是这个SEM中的内生变量。

z i1和z i2由于在模型外决定,是外生变量。

其次,从统计观点来看,关于z i1和z i2的关键假定是,它们都与u i1和u i2无关。

由于这些误差出现在结构方程中,所以它们是结构误差的例子。

最后,SEM中的每个方程自身都应该有一个行为上的其他条件不变解释。

二、OLS中的联立性偏误在一个简单模型中,与因变量同时决定的解释变量一般都与误差项相关,这就导致OLS中存在偏误和不一致性。

1.约简型方程考虑两个方程的结构模型:y1=α1y2+β1z1+u1y2=α2y1+β2z2+u2并专门估计第一个方程。

变量z1和z2都是外生的,所以每个都与u1和u2无关。

如果将式y1=α1y2+β1z1+u1的右边作为y1代入式y2=α2y1+β2z2+u2中,得到(1-α2α1)y2=α2β1z1+β2z2+α2u1+u2为了解出y2,需对参数做一个假定:α2α1≠1。

这个假定是否具有限制性则取决于应用。

y2可写成y2=π21z1+π22z2+v2其中,π21=α2β1/(1-α2α1)、π22=β2/(1-α2α1)和v2=(α2u1+u2)/(1-α2α1)。

用外生变量和误差项表示y2的方程(16.14)是y2的约简型方程。

计量经济学第三版版课后答案全第⼆章(1)①对于浙江省预算收⼊与全省⽣产总值的模型,⽤Eviews分析结果如下:Dependent Variable: YMethod: Least SquaresDate: 12/03/14 Time: 17:00Sample (adjusted): 1 33Included observations: 33 after adjustmentsVariable Coefficient Std. Error t-Statistic Prob.??XCR-squaredMean dependent var Adjusted R-squared. dependent var. of regression Akaike info criterionSum squared residSchwarz criterionLog likelihood Hannan-Quinn criter.F-statisticDurbin-Watson statProb(F-statistic)②由上可知,模型的参数:斜率系数,截距为—③关于浙江省财政预算收⼊与全省⽣产总值的模型,检验模型的显着性:1)可决系数为,说明所建模型整体上对样本数据拟合较好。

2)对于回归系数的t检验:t(β2)=>(31)=,对斜率系数的显着性检验表明,全省⽣产总值对财政预算总收⼊有显着影响。

④⽤规范形式写出检验结果如下:Y=—t= ()R2= F= n=33⑤经济意义是:全省⽣产总值每增加1亿元,财政预算总收⼊增加亿元。

(2)当x=32000时,①进⾏点预测,由上可知Y=—,代⼊可得:Y= Y=*32000—=②进⾏区间预测:∑x 2=∑(X i —X )2=δ2x (n —1)= ? x (33—1)= (X f —X)2=(32000—?2当Xf=32000时,将相关数据代⼊计算得到:即Yf 的置信区间为(—, +)(3) 对于浙江省预算收⼊对数与全省⽣产总值对数的模型,由Eviews 分析结果如下:Dependent Variable: LNYMethod: Least SquaresDate: 12/03/14 Time: 18:00Sample (adjusted): 1 33Included observations: 33 after adjustmentsVariable Coefficien t Std. Error t-Statistic Prob.?? LNXCR-squared Mean dependent var Adjusted R-squared . dependent var. of regression Akaike infocriterion Sum squared resid Schwarz criterionLog likelihood Hannan-Quinncriter. F-statistic Durbin-Watson statProb(F-statistic)①模型⽅程为:lnY=由上可知,模型的参数:斜率系数为,截距为③关于浙江省财政预算收⼊与全省⽣产总值的模型,检验其显着性: 1)可决系数为,说明所建模型整体上对样本数据拟合较好。

T his appendix derives various results for ordinary least squares estimation of themultiple linear regression model using matrix notation and matrix algebra (see Appendix D for a summary). The material presented here is much more ad-vanced than that in the text.E.1THE MODEL AND ORDINARY LEAST SQUARES ESTIMATIONThroughout this appendix,we use the t subscript to index observations and an n to denote the sample size. It is useful to write the multiple linear regression model with k parameters as follows:y t ϭ1ϩ2x t 2ϩ3x t 3ϩ… ϩk x tk ϩu t ,t ϭ 1,2,…,n ,(E.1)where y t is the dependent variable for observation t ,and x tj ,j ϭ 2,3,…,k ,are the inde-pendent variables. Notice how our labeling convention here differs from the text:we call the intercept 1and let 2,…,k denote the slope parameters. This relabeling is not important,but it simplifies the matrix approach to multiple regression.For each t ,define a 1 ϫk vector,x t ϭ(1,x t 2,…,x tk ),and let ϭ(1,2,…,k )Јbe the k ϫ1 vector of all parameters. Then,we can write (E.1) asy t ϭx t ϩu t ,t ϭ 1,2,…,n .(E.2)[Some authors prefer to define x t as a column vector,in which case,x t is replaced with x t Јin (E.2). Mathematically,it makes more sense to define it as a row vector.] We can write (E.2) in full matrix notation by appropriately defining data vectors and matrices. Let y denote the n ϫ1 vector of observations on y :the t th element of y is y t .Let X be the n ϫk vector of observations on the explanatory variables. In other words,the t th row of X consists of the vector x t . Equivalently,the (t ,j )th element of X is simply x tj :755A p p e n d i x EThe Linear Regression Model inMatrix Formn X ϫ k ϵϭ .Finally,let u be the n ϫ 1 vector of unobservable disturbances. Then,we can write (E.2)for all n observations in matrix notation :y ϭX ϩu .(E.3)Remember,because X is n ϫ k and is k ϫ 1,X is n ϫ 1.Estimation of proceeds by minimizing the sum of squared residuals,as in Section3.2. Define the sum of squared residuals function for any possible k ϫ 1 parameter vec-tor b asSSR(b ) ϵ͚nt ϭ1(y t Ϫx t b )2.The k ϫ 1 vector of ordinary least squares estimates,ˆϭ(ˆ1,ˆ2,…,ˆk ),minimizes SSR(b ) over all possible k ϫ 1 vectors b . This is a problem in multivariable calculus.For ˆto minimize the sum of squared residuals,it must solve the first order conditionѨSSR(ˆ)/Ѩb ϵ0.(E.4)Using the fact that the derivative of (y t Ϫx t b )2with respect to b is the 1ϫ k vector Ϫ2(y t Ϫx t b )x t ,(E.4) is equivalent to͚nt ϭ1xt Ј(y t Ϫx t ˆ) ϵ0.(E.5)(We have divided by Ϫ2 and taken the transpose.) We can write this first order condi-tion as͚nt ϭ1(y t Ϫˆ1Ϫˆ2x t 2Ϫ… Ϫˆk x tk ) ϭ0͚nt ϭ1x t 2(y t Ϫˆ1Ϫˆ2x t 2Ϫ… Ϫˆk x tk ) ϭ0...͚nt ϭ1x tk (y t Ϫˆ1Ϫˆ2x t 2Ϫ… Ϫˆk x tk ) ϭ0,which,apart from the different labeling convention,is identical to the first order condi-tions in equation (3.13). We want to write these in matrix form to make them more use-ful. Using the formula for partitioned multiplication in Appendix D,we see that (E.5)is equivalent to΅1x 12x 13...x 1k1x 22x 23...x 2k...1x n 2x n 3...x nk ΄΅x 1x 2...x n ΄Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form756Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix FormXЈ(yϪXˆ) ϭ0(E.6) or(XЈX)ˆϭXЈy.(E.7)It can be shown that (E.7) always has at least one solution. Multiple solutions do not help us,as we are looking for a unique set of OLS estimates given our data set. Assuming that the kϫ k symmetric matrix XЈX is nonsingular,we can premultiply both sides of (E.7) by (XЈX)Ϫ1to solve for the OLS estimator ˆ:ˆϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈy.(E.8)This is the critical formula for matrix analysis of the multiple linear regression model. The assumption that XЈX is invertible is equivalent to the assumption that rank(X) ϭk, which means that the columns of X must be linearly independent. This is the matrix ver-sion of MLR.4 in Chapter 3.Before we continue,(E.8) warrants a word of warning. It is tempting to simplify the formula for ˆas follows:ˆϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈyϭXϪ1(XЈ)Ϫ1XЈyϭXϪ1y.The flaw in this reasoning is that X is usually not a square matrix,and so it cannot be inverted. In other words,we cannot write (XЈX)Ϫ1ϭXϪ1(XЈ)Ϫ1unless nϭk,a case that virtually never arises in practice.The nϫ 1 vectors of OLS fitted values and residuals are given byyˆϭXˆ,uˆϭyϪyˆϭyϪXˆ.From (E.6) and the definition of uˆ,we can see that the first order condition for ˆis the same asXЈuˆϭ0.(E.9) Because the first column of X consists entirely of ones,(E.9) implies that the OLS residuals always sum to zero when an intercept is included in the equation and that the sample covariance between each independent variable and the OLS residuals is zero. (We discussed both of these properties in Chapter 3.)The sum of squared residuals can be written asSSR ϭ͚n tϭ1uˆt2ϭuˆЈuˆϭ(yϪXˆ)Ј(yϪXˆ).(E.10)All of the algebraic properties from Chapter 3 can be derived using matrix algebra. For example,we can show that the total sum of squares is equal to the explained sum of squares plus the sum of squared residuals [see (3.27)]. The use of matrices does not pro-vide a simpler proof than summation notation,so we do not provide another derivation.757The matrix approach to multiple regression can be used as the basis for a geometri-cal interpretation of regression. This involves mathematical concepts that are even more advanced than those we covered in Appendix D. [See Goldberger (1991) or Greene (1997).]E.2FINITE SAMPLE PROPERTIES OF OLSDeriving the expected value and variance of the OLS estimator ˆis facilitated by matrix algebra,but we must show some care in stating the assumptions.A S S U M P T I O N E.1(L I N E A R I N P A R A M E T E R S)The model can be written as in (E.3), where y is an observed nϫ 1 vector, X is an nϫ k observed matrix, and u is an nϫ 1 vector of unobserved errors or disturbances.A S S U M P T I O N E.2(Z E R O C O N D I T I O N A L M E A N)Conditional on the entire matrix X, each error ut has zero mean: E(ut͉X) ϭ0, tϭ1,2,…,n.In vector form,E(u͉X) ϭ0.(E.11) This assumption is implied by MLR.3 under the random sampling assumption,MLR.2.In time series applications,Assumption E.2 imposes strict exogeneity on the explana-tory variables,something discussed at length in Chapter 10. This rules out explanatory variables whose future values are correlated with ut; in particular,it eliminates laggeddependent variables. Under Assumption E.2,we can condition on the xtjwhen we com-pute the expected value of ˆ.A S S U M P T I O N E.3(N O P E R F E C T C O L L I N E A R I T Y) The matrix X has rank k.This is a careful statement of the assumption that rules out linear dependencies among the explanatory variables. Under Assumption E.3,XЈX is nonsingular,and so ˆis unique and can be written as in (E.8).T H E O R E M E.1(U N B I A S E D N E S S O F O L S)Under Assumptions E.1, E.2, and E.3, the OLS estimator ˆis unbiased for .P R O O F:Use Assumptions E.1 and E.3 and simple algebra to writeˆϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈyϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ(Xϩu)ϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1(XЈX)ϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈuϭϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈu,(E.12)where we use the fact that (XЈX)Ϫ1(XЈX) ϭIk . Taking the expectation conditional on X givesAppendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form 758E(ˆ͉X)ϭϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈE(u͉X)ϭϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ0ϭ,because E(u͉X) ϭ0under Assumption E.2. This argument clearly does not depend on the value of , so we have shown that ˆis unbiased.To obtain the simplest form of the variance-covariance matrix of ˆ,we impose the assumptions of homoskedasticity and no serial correlation.A S S U M P T I O N E.4(H O M O S K E D A S T I C I T Y A N DN O S E R I A L C O R R E L A T I O N)(i) Var(ut͉X) ϭ2, t ϭ 1,2,…,n. (ii) Cov(u t,u s͉X) ϭ0, for all t s. In matrix form, we canwrite these two assumptions asVar(u͉X) ϭ2I n,(E.13)where Inis the nϫ n identity matrix.Part (i) of Assumption E.4 is the homoskedasticity assumption:the variance of utcan-not depend on any element of X,and the variance must be constant across observations, t. Part (ii) is the no serial correlation assumption:the errors cannot be correlated across observations. Under random sampling,and in any other cross-sectional sampling schemes with independent observations,part (ii) of Assumption E.4 automatically holds. For time series applications,part (ii) rules out correlation in the errors over time (both conditional on X and unconditionally).Because of (E.13),we often say that u has scalar variance-covariance matrix when Assumption E.4 holds. We can now derive the variance-covariance matrix of the OLS estimator.T H E O R E M E.2(V A R I A N C E-C O V A R I A N C EM A T R I X O F T H E O L S E S T I M A T O R)Under Assumptions E.1 through E.4,Var(ˆ͉X) ϭ2(XЈX)Ϫ1.(E.14)P R O O F:From the last formula in equation (E.12), we haveVar(ˆ͉X) ϭVar[(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈu͉X] ϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ[Var(u͉X)]X(XЈX)Ϫ1.Now, we use Assumption E.4 to getVar(ˆ͉X)ϭ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ(2I n)X(XЈX)Ϫ1ϭ2(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈX(XЈX)Ϫ1ϭ2(XЈX)Ϫ1.Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form759Formula (E.14) means that the variance of ˆj (conditional on X ) is obtained by multi-plying 2by the j th diagonal element of (X ЈX )Ϫ1. For the slope coefficients,we gave an interpretable formula in equation (3.51). Equation (E.14) also tells us how to obtain the covariance between any two OLS estimates:multiply 2by the appropriate off diago-nal element of (X ЈX )Ϫ1. In Chapter 4,we showed how to avoid explicitly finding covariances for obtaining confidence intervals and hypotheses tests by appropriately rewriting the model.The Gauss-Markov Theorem,in its full generality,can be proven.T H E O R E M E .3 (G A U S S -M A R K O V T H E O R E M )Under Assumptions E.1 through E.4, ˆis the best linear unbiased estimator.P R O O F :Any other linear estimator of can be written as˜ ϭA Јy ,(E.15)where A is an n ϫ k matrix. In order for ˜to be unbiased conditional on X , A can consist of nonrandom numbers and functions of X . (For example, A cannot be a function of y .) To see what further restrictions on A are needed, write˜ϭA Ј(X ϩu ) ϭ(A ЈX )ϩA Јu .(E.16)Then,E(˜͉X )ϭA ЈX ϩE(A Јu ͉X )ϭA ЈX ϩA ЈE(u ͉X ) since A is a function of XϭA ЈX since E(u ͉X ) ϭ0.For ˜to be an unbiased estimator of , it must be true that E(˜͉X ) ϭfor all k ϫ 1 vec-tors , that is,A ЈX ϭfor all k ϫ 1 vectors .(E.17)Because A ЈX is a k ϫ k matrix, (E.17) holds if and only if A ЈX ϭI k . Equations (E.15) and (E.17) characterize the class of linear, unbiased estimators for .Next, from (E.16), we haveVar(˜͉X ) ϭA Ј[Var(u ͉X )]A ϭ2A ЈA ,by Assumption E.4. Therefore,Var(˜͉X ) ϪVar(ˆ͉X )ϭ2[A ЈA Ϫ(X ЈX )Ϫ1]ϭ2[A ЈA ϪA ЈX (X ЈX )Ϫ1X ЈA ] because A ЈX ϭI kϭ2A Ј[I n ϪX (X ЈX )Ϫ1X Ј]Aϵ2A ЈMA ,where M ϵI n ϪX (X ЈX )Ϫ1X Ј. Because M is symmetric and idempotent, A ЈMA is positive semi-definite for any n ϫ k matrix A . This establishes that the OLS estimator ˆis BLUE. How Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form 760Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Formis this significant? Let c be any kϫ 1 vector and consider the linear combination cЈϭc11ϩc22ϩ… ϩc kk, which is a scalar. The unbiased estimators of cЈare cЈˆand cЈ˜. ButVar(c˜͉X) ϪVar(cЈˆ͉X) ϭcЈ[Var(˜͉X) ϪVar(ˆ͉X)]cՆ0,because [Var(˜͉X) ϪVar(ˆ͉X)] is p.s.d. Therefore, when it is used for estimating any linear combination of , OLS yields the smallest variance. In particular, Var(ˆj͉X) ՅVar(˜j͉X) for any other linear, unbiased estimator of j.The unbiased estimator of the error variance 2can be written asˆ2ϭuˆЈuˆ/(n Ϫk),where we have labeled the explanatory variables so that there are k total parameters, including the intercept.T H E O R E M E.4(U N B I A S E D N E S S O Fˆ2)Under Assumptions E.1 through E.4, ˆ2is unbiased for 2: E(ˆ2͉X) ϭ2for all 2Ͼ0. P R O O F:Write uˆϭyϪXˆϭyϪX(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈyϭM yϭM u, where MϭI nϪX(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ,and the last equality follows because MXϭ0. Because M is symmetric and idempotent,uˆЈuˆϭuЈMЈM uϭuЈM u.Because uЈM u is a scalar, it equals its trace. Therefore,ϭE(uЈM u͉X)ϭE[tr(uЈM u)͉X] ϭE[tr(M uuЈ)͉X]ϭtr[E(M uuЈ|X)] ϭtr[M E(uuЈ|X)]ϭtr(M2I n) ϭ2tr(M) ϭ2(nϪ k).The last equality follows from tr(M) ϭtr(I) Ϫtr[X(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ] ϭnϪtr[(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈX] ϭnϪn) ϭnϪk. Therefore,tr(IkE(ˆ2͉X) ϭE(uЈM u͉X)/(nϪ k) ϭ2.E.3STATISTICAL INFERENCEWhen we add the final classical linear model assumption,ˆhas a multivariate normal distribution,which leads to the t and F distributions for the standard test statistics cov-ered in Chapter 4.A S S U M P T I O N E.5(N O R M A L I T Y O F E R R O R S)are independent and identically distributed as Normal(0,2). Conditional on X, the utEquivalently, u given X is distributed as multivariate normal with mean zero and variance-covariance matrix 2I n: u~ Normal(0,2I n).761Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form Under Assumption E.5,each uis independent of the explanatory variables for all t. Inta time series setting,this is essentially the strict exogeneity assumption.T H E O R E M E.5(N O R M A L I T Y O Fˆ)Under the classical linear model Assumptions E.1 through E.5, ˆconditional on X is dis-tributed as multivariate normal with mean and variance-covariance matrix 2(XЈX)Ϫ1.Theorem E.5 is the basis for statistical inference involving . In fact,along with the properties of the chi-square,t,and F distributions that we summarized in Appendix D, we can use Theorem E.5 to establish that t statistics have a t distribution under Assumptions E.1 through E.5 (under the null hypothesis) and likewise for F statistics. We illustrate with a proof for the t statistics.T H E O R E M E.6Under Assumptions E.1 through E.5,(ˆjϪj)/se(ˆj) ~ t nϪk,j ϭ 1,2,…,k.P R O O F:The proof requires several steps; the following statements are initially conditional on X. First, by Theorem E.5, (ˆjϪj)/sd(ˆ) ~ Normal(0,1), where sd(ˆj) ϭ͙ෆc jj, and c jj is the j th diagonal element of (XЈX)Ϫ1. Next, under Assumptions E.1 through E.5, conditional on X,(n Ϫ k)ˆ2/2~ 2nϪk.(E.18)This follows because (nϪk)ˆ2/2ϭ(u/)ЈM(u/), where M is the nϫn symmetric, idem-potent matrix defined in Theorem E.4. But u/~ Normal(0,I n) by Assumption E.5. It follows from Property 1 for the chi-square distribution in Appendix D that (u/)ЈM(u/) ~ 2nϪk (because M has rank nϪk).We also need to show that ˆand ˆ2are independent. But ˆϭϩ(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈu, and ˆ2ϭuЈM u/(nϪk). Now, [(XЈX)Ϫ1XЈ]Mϭ0because XЈMϭ0. It follows, from Property 5 of the multivariate normal distribution in Appendix D, that ˆand M u are independent. Since ˆ2is a function of M u, ˆand ˆ2are also independent.Finally, we can write(ˆjϪj)/se(ˆj) ϭ[(ˆjϪj)/sd(ˆj)]/(ˆ2/2)1/2,which is the ratio of a standard normal random variable and the square root of a 2nϪk/(nϪk) random variable. We just showed that these are independent, and so, by def-inition of a t random variable, (ˆjϪj)/se(ˆj) has the t nϪk distribution. Because this distri-bution does not depend on X, it is the unconditional distribution of (ˆjϪj)/se(ˆj) as well.From this theorem,we can plug in any hypothesized value for j and use the t statistic for testing hypotheses,as usual.Under Assumptions E.1 through E.5,we can compute what is known as the Cramer-Rao lower bound for the variance-covariance matrix of unbiased estimators of (again762conditional on X ) [see Greene (1997,Chapter 4)]. This can be shown to be 2(X ЈX )Ϫ1,which is exactly the variance-covariance matrix of the OLS estimator. This implies that ˆis the minimum variance unbiased estimator of (conditional on X ):Var(˜͉X ) ϪVar(ˆ͉X ) is positive semi-definite for any other unbiased estimator ˜; we no longer have to restrict our attention to estimators linear in y .It is easy to show that the OLS estimator is in fact the maximum likelihood estima-tor of under Assumption E.5. For each t ,the distribution of y t given X is Normal(x t ,2). Because the y t are independent conditional on X ,the likelihood func-tion for the sample is obtained from the product of the densities:͟nt ϭ1(22)Ϫ1/2exp[Ϫ(y t Ϫx t )2/(22)].Maximizing this function with respect to and 2is the same as maximizing its nat-ural logarithm:͚nt ϭ1[Ϫ(1/2)log(22) Ϫ(yt Ϫx t )2/(22)].For obtaining ˆ,this is the same as minimizing͚nt ϭ1(y t Ϫx t )2—the division by 22does not affect the optimization—which is just the problem that OLS solves. The esti-mator of 2that we have used,SSR/(n Ϫk ),turns out not to be the MLE of 2; the MLE is SSR/n ,which is a biased estimator. Because the unbiased estimator of 2results in t and F statistics with exact t and F distributions under the null,it is always used instead of the MLE.SUMMARYThis appendix has provided a brief discussion of the linear regression model using matrix notation. This material is included for more advanced classes that use matrix algebra,but it is not needed to read the text. In effect,this appendix proves some of the results that we either stated without proof,proved only in special cases,or proved through a more cumbersome method of proof. Other topics—such as asymptotic prop-erties,instrumental variables estimation,and panel data models—can be given concise treatments using matrices. Advanced texts in econometrics,including Davidson and MacKinnon (1993),Greene (1997),and Wooldridge (1999),can be consulted for details.KEY TERMSAppendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form 763First Order Condition Matrix Notation Minimum Variance Unbiased Scalar Variance-Covariance MatrixVariance-Covariance Matrix of the OLS EstimatorPROBLEMSE.1Let x t be the 1ϫ k vector of explanatory variables for observation t . Show that the OLS estimator ˆcan be written asˆϭΘ͚n tϭ1xt Јx t ΙϪ1Θ͚nt ϭ1xt Јy t Ι.Dividing each summation by n shows that ˆis a function of sample averages.E.2Let ˆbe the k ϫ 1 vector of OLS estimates.(i)Show that for any k ϫ 1 vector b ,we can write the sum of squaredresiduals asSSR(b ) ϭu ˆЈu ˆϩ(ˆϪb )ЈX ЈX (ˆϪb ).[Hint :Write (y Ϫ X b )Ј(y ϪX b ) ϭ[u ˆϩX (ˆϪb )]Ј[u ˆϩX (ˆϪb )]and use the fact that X Јu ˆϭ0.](ii)Explain how the expression for SSR(b ) in part (i) proves that ˆuniquely minimizes SSR(b ) over all possible values of b ,assuming Xhas rank k .E.3Let ˆbe the OLS estimate from the regression of y on X . Let A be a k ϫ k non-singular matrix and define z t ϵx t A ,t ϭ 1,…,n . Therefore,z t is 1ϫ k and is a non-singular linear combination of x t . Let Z be the n ϫ k matrix with rows z t . Let ˜denote the OLS estimate from a regression ofy on Z .(i)Show that ˜ϭA Ϫ1ˆ.(ii)Let y ˆt be the fitted values from the original regression and let y ˜t be thefitted values from regressing y on Z . Show that y ˜t ϭy ˆt ,for all t ϭ1,2,…,n . How do the residuals from the two regressions compare?(iii)Show that the estimated variance matrix for ˜is ˆ2A Ϫ1(X ЈX )Ϫ1A Ϫ1,where ˆ2is the usual variance estimate from regressing y on X .(iv)Let the ˆj be the OLS estimates from regressing y t on 1,x t 2,…,x tk ,andlet the ˜j be the OLS estimates from the regression of yt on 1,a 2x t 2,…,a k x tk ,where a j 0,j ϭ 2,…,k . Use the results from part (i)to find the relationship between the ˜j and the ˆj .(v)Assuming the setup of part (iv),use part (iii) to show that se(˜j ) ϭse(ˆj )/͉a j ͉.(vi)Assuming the setup of part (iv),show that the absolute values of the tstatistics for ˜j and ˆj are identical.Appendix E The Linear Regression Model in Matrix Form 764。

CHAPTER 1SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS1.1 (i) Ideally, we could randomly assign students to classes of different sizes. That is, each student is assigned a different class size without regard to any student characteristics such as ability and family background. For reasons we will see in Chapter 2, we would like substantial variation in class sizes (subject, of course, to ethical considerations and resource constraints).(ii) A negative correlation means that larger class size is associated with lower performance. We might find a negative correlation because larger class size actually hurts performance. However, with observational data, there are other reasons we might find a negative relationship. For example, children from more affluent families might be more likely to attend schools with smaller class sizes, and affluent children generally score better on standardized tests. Another possibility is that, within a school, a principal might assign the better students to smaller classes. Or, some parents might insist their children are in the smaller classes, and these same parents tend to be more involved in their children’s education.(iii) Given the potential for confounding factors – some of which are listed in (ii) – finding a negative correlation would not be strong evidence that smaller class sizes actually lead to better performance. Some way of controlling for the confounding factors is needed, and this is the subject of multiple regression analysis.1.2 (i) Here is one way to pose the question: If two firms, say A and B, are identical in all respects except that firm A supplies job training one hour per worker more than firm B, by how much would firm A’s output differ from firm B’s?(ii) Firms are likely to choose job training depending on the characteristics of workers. Some observed characteristics are years of schooling, years in the workforce, and experience in a particular job. Firms might even discriminate based on age, gender, or race. Perhaps firms choose to offer training to more or les s able workers, where “ability” might be difficult to quantify but where a manager has some idea about the relative abilities of different employees. Moreover, different kinds of workers might be attracted to firms that offer more job training on average, and this might not be evident to employers.(iii) The amount of capital and technology available to workers would also affect output. So, two firms with exactly the same kinds of employees would generally have different outputs if they use different amounts of capital or technology. The quality of managers would also have an effect.(iv) No, unless the amount of training is randomly assigned. The many factors listed in parts (ii) and (iii) can contribute to finding a positive correlation between output and training even if job training does not improve worker productivity.1.3 It does not make sense to pose the question in terms of causality. Economists would assume that students choose a mix of studying and working (and other activities, such as attending class,leisure, and sleeping) based on rational behavior, such as maximizing utility subject to the constraint that there are only 168 hours in a week. We can then use statistical methods to measure the association between studying and working, including regression analysis that we cover starting in Chapter 2. But we would not be claiming that one variable “causes” the other. They are both choice variables of the student.CHAPTER 2SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS2.1 (i) Income, age, and family background (such as number of siblings) are just a fewpossibilities. It seems that each of these could be correlated with years of education. (Income and education are probably positively correlated; age and education may be negatively correlated because women in more recent cohorts have, on average, more education; and number of siblings and education are probably negatively correlated.)(ii) Not if the factors we listed in part (i) are correlated with educ . Because we would like to hold these factors fixed, they are part of the error term. But if u is correlated with educ then E(u|educ ) ≠ 0, and so SLR.4 fails.2.2 In the equation y = β0 + β1x + u , add and subtract α0 from the right hand side to get y = (α0 + β0) + β1x + (u - α0). Call the new error e = u - α0, so that E(e ) = 0. The new intercept is α0 + β0, but the slope is still β1.2.3 (i) Let y i = GPA i , x i = ACT i , and n = 8. Then x = 25.875, y =3.2125, 1ni =∑(x i – x )(y i – y ) =5.8125, and 1ni =∑(x i – x )2 = 56.875. From equation (2.9), we obtain the slope as 1ˆβ= 5.8125/56.875 ≈ .1022, rounded to four places after the decimal. From (2.17), 0ˆβ = y – 1ˆβx ≈ 3.2125 – (.1022)25.875 ≈ .5681. So we can write GPA = .5681 + .1022 ACTn = 8.The intercept does not have a useful interpretation because ACT is not close to zero for the population of interest. If ACT is 5 points higher, GPA increases by .1022(5) = .511.(ii) The fitted values and residuals — rounded to four decimal places — are given along with the observation number i and GPA in the following table:You can verify that the residuals, as reported in the table, sum to -.0002, which is pretty close to zero given the inherent rounding error.(iii) When ACT = 20, GPA = .5681 + .1022(20) ≈ 2.61.(iv) The sum of squared residuals, 21ˆni i u=∑, is about .4347 (rounded to four decimal places), and the total sum of squares, 1ni =∑(y i – y )2, is about 1.0288. So the R -squared from theregression isR 2 = 1 – SSR/SST ≈ 1 – (.4347/1.0288) ≈ .577.Therefore, about 57.7% of the variation in GPA is explained by ACT in this small sample of students.2.4 (i) When cigs = 0, predicted birth weight is 119.77 ounces. When cigs = 20, bwght = 109.49. This is about an 8.6% drop.(ii) Not necessarily. There are many other factors that can affect birth weight, particularly overall health of the mother and quality of prenatal care. These could be correlated withcigarette smoking during birth. Also, something such as caffeine consumption can affect birth weight, and might also be correlated with cigarette smoking.(iii) If we want a predicted bwght of 125, then cigs = (125 – 119.77)/( –.524) ≈–10.18, or about –10 cigarettes! This is nonsense, of course, and it shows what happens when we are trying to predict something as complicated as birth weight with only a single explanatory variable. The largest predicted birth weight is necessarily 119.77. Yet almost 700 of the births in the sample had a birth weight higher than 119.77.(iv) 1,176 out of 1,388 women did not smoke while pregnant, or about 84.7%. Because we are using only cigs to explain birth weight, we have only one predicted birth weight at cigs = 0. The predicted birth weight is necessarily roughly in the middle of the observed birth weights at cigs = 0, and so we will under predict high birth rates.2.5 (i) The intercept implies that when inc = 0, cons is predicted to be negative $124.84. This, of course, cannot be true, and reflects that fact that this consumption function might be a poor predictor of consumption at very low-income levels. On the other hand, on an annual basis, $124.84 is not so far from zero.(ii) Just plug 30,000 into the equation: cons = –124.84 + .853(30,000) = 25,465.16 dollars.(iii) The MPC and the APC are shown in the following graph. Even though the intercept is negative, the smallest APC in the sample is positive. The graph starts at an annual income levelincreases housing prices.(ii) If the city chose to locate the incinerator in an area away from more expensive neighborhoods, then log(dist) is positively correlated with housing quality. This would violate SLR.4, and OLS estimation is biased.(iii) Size of the house, number of bathrooms, size of the lot, age of the home, and quality of the neighborhood (including school quality), are just a handful of factors. As mentioned in part (ii), these could certainly be correlated with dist [and log(dist)].2.7 (i) When we condition on incbecomes a constant. So E(u |inc⋅e |inc) = ⋅E(e |inc⋅0 because E(e |inc ) = E(e ) = 0.(ii) Again, when we condition on incbecomes a constant. So Var(u |inc⋅e |inc2Var(e |inc ) = 2e σinc because Var(e |inc ) = 2e σ.(iii) Families with low incomes do not have much discretion about spending; typically, a low-income family must spend on food, clothing, housing, and other necessities. Higher income people have more discretion, and some might choose more consumption while others more saving. This discretion suggests wider variability in saving among higher income families.2.8 (i) From equation (2.66),1β = 1n i i i x y =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ / 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑.Plugging in y i = β0 + β1x i + u i gives1β = 011()n i i i i x x u ββ=⎛⎫++ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑.After standard algebra, the numerator can be written as201111in n ni i i i i i x x x u ββ===++∑∑∑.Putting this over the denominator shows we can write 1β as1β = β01n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ + β1 + 1n i i i x u =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫⎪⎝⎭∑.Conditional on the x i , we haveE(1β) = β01n i i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑/ 21n i i x =⎛⎫⎪⎝⎭∑ + β1because E(u i ) = 0 for all i . Therefore, the bias in 1β is given by the first term in this equation. This bias is obviously zero when β0 = 0. It is also zero when 1ni i x =∑ = 0, which is the same asx = 0. In the latter case, regression through the origin is identical to regression with an intercept.(ii) From the last expression for 1βin part (i) we have, conditional on the x i ,Var(1β)= 221n i i x -=⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑Var 1n i i i x u =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ = 221n i i x -=⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑21Var()n i i i x u =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑= 221n i i x -=⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑221n i i x σ=⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑ = 2σ/ 21ni i x =⎛⎫ ⎪⎝⎭∑.(iii) From (2.57), Var(1ˆβ) = σ2/21()n i i x x =⎛⎫- ⎪⎝⎭∑. From the hint, 21n i i x =∑ ≥ 21()n i i x x =-∑, and soVar(1β) ≤ Var(1ˆβ). A more direct way to see this is to write 21()ni i x x =-∑ = 221()ni i x n x =-∑, which is less than 21ni i x =∑ unless x = 0.(iv) For a given sample size, the bias in 1β increases as x increases (holding the sum of the2i x fixed). But as x increases, the variance of 1ˆβincreases relative to Var(1β). The bias in 1β is also small when 0β is small. Therefore, whether we prefer 1β or 1ˆβ on a mean squared error basis depends on the sizes of 0β, x , and n (in addition to the size of 21ni i x =∑).2.9 (i) We follow the hint, noting that 1c y = 1c y (the sample average of 1i c y is c 1 times the sample average of y i ) and 2c x = 2c x . When we regress c 1y i on c 2x i (including an intercept) we use equation (2.19) to obtain the slope:2211121112222221111112221()()()()()()()()ˆ.()n ni iiii i nnii i i niii nii c x c x c y c y c c x x y y c x c x cx x x x y y c c c c x x ββ======----==----=⋅=-∑∑∑∑∑∑From (2.17), we obtain the intercept as 0β = (c 1y ) – 1β(c 2x ) = (c 1y ) – [(c 1/c 2)1ˆβ](c 2x ) = c 1(y – 1ˆβx ) = c 10ˆβ) because the intercept from regressing y i on x i is (y – 1ˆβx ).(ii) We use the same approach from part (i) along with the fact that 1()c y + = c 1 + y and2()c x + = c 2 + x . Therefore, 11()()i c y c y +-+ = (c 1 + y i ) – (c 1 + y ) = y i – y and (c 2 + x i ) –2()c x + = x i – x . So c 1 and c 2 entirely drop out of the slope formula for the regression of (c 1 + y i )on (c 2 + x i ), and 1β = 1ˆβ. The intercept is 0β = 1()c y + – 1β2()c x + = (c 1 + y ) – 1ˆβ(c 2 + x ) = (1ˆy x β-) + c 1 – c 21ˆβ = 0ˆβ + c 1 – c 21ˆβ, which is what we wanted to show.(iii) We can simply apply part (ii) because 11log()log()log()i i c y c y =+. In other words, replace c 1 with log(c 1), y i with log(y i ), and set c 2 = 0.(iv) Again, we can apply part (ii) with c 1 = 0 and replacing c 2 with log(c 2) and x i with log(x i ). If 01ˆˆ and ββ are the original intercept and slope, then 11ˆββ= and 0021ˆˆlog()c βββ=-.2.10 (i) This derivation is essentially done in equation (2.52), once (1/SST )x is brought inside the summation (which is valid because SST x does not depend on i ). Then, just define /SST i i x w d =.(ii) Because 111ˆˆCov(,)E[()] ,u u βββ=- we show that the latter is zero. But, from part (i), ()1111ˆE[()] =E E().nn i i i i i i u wu u w u u ββ==⎡⎤-=⎢⎥⎣⎦∑∑ Because the i u are pairwise uncorrelated (they are independent), 22E()E(/)/i i u u u n n σ== (because E()0, i h u u i h =≠). Therefore,22111E()(/)(/)0.n n ni i i i i i i w u u w n n w σσ======∑∑∑(iii) The formula for the OLS intercept is 0ˆˆy x ββ=- and, plugging in 01y x u ββ=++ gives 01111ˆˆˆ()().x u x u x βββββββ=++-=+--(iv) Because 1ˆ and u β are uncorrelated, 222222201ˆˆVar()Var()Var()/(/SST )//SST x xu x n x n x ββσσσσ=+=+=+, which is what we wanted to show.(v) Using the hint and substitution gives ()220ˆVar()[SST /]/SST x xn x βσ=+ ()()2122221211/SST /SST .nni x i x i i n x x x n x σσ--==⎡⎤=-+=⎢⎥⎣⎦∑∑2.11 (i) We would want to randomly assign the number of hours in the preparation course so that hours is independent of other factors that affect performance on the SAT. Then, we would collect information on SAT score for each student in the experiment, yielding a data set{(,):1,...,}i i sat hours i n =, where n is the number of students we can afford to have in the study. From equation (2.7), we should try to get as much variation in i hours as is feasible.(ii) Here are three factors: innate ability, family income, and general health on the day of the exam. If we think students with higher native intelligence think they do not need to prepare for the SAT, then ability and hours will be negatively correlated. Family income would probably be positively correlated with hours , because higher income families can more easily affordpreparation courses. Ruling out chronic health problems, health on the day of the exam should be roughly uncorrelated with hours spent in a preparation course.(iii) If preparation courses are effective,1β should be positive: other factors equal, an increase in hours should increase sat .(iv) The intercept, 0β, has a useful interpretation in this example: because E(u ) = 0, 0β is the average SAT score for students in the population with hours = 0.CHAPTER 3SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS3.1 (i) hsperc is defined so that the smaller it is, the lower the student’s standing in high school. Everything else equal, the worse the student’s standing in high school , the lower is his/her expected college GPA. (ii) Just plug these values into the equation:colgpa = 1.392 - .0135(20) + .00148(1050) = 2.676.(iii) The difference between A and B is simply 140 times the coefficient on sat , because hsperc is the same for both students. So A is predicted to have a score .00148(140) ≈ .207 higher. (iv) With hsperc fixed, colgpa ∆ = .00148∆sat . Now, we want to find ∆sat such thatcolgpa ∆ = .5, so .5 = .00148(∆sat ) or ∆sat = .5/(.00148) ≈ 338. Perhaps not surprisingly, a large ceteris paribus difference in SAT score – almost two and one-half standard deviations – is needed to obtain a predicted difference in college GPA or a half a point.3.2 (i) Yes. Because of budget constraints, it makes sense that, the more siblings there are in a family, the less education any one child in the family has. To find the increase in the number of siblings that reduces predicted education by one year, we solve 1 = .094(∆sibs ), so ∆sibs = 1/.094 ≈ 10.6. (ii) Holding sibs and feduc fixed, one more year of mother’s education implies .131 years more of predicted education. So if a mother has four more years of education, her son is predicted to have about a half a year (.524) more years of education.(iii) Since the number of siblings is the same, but meduc and feduc are both different, the coefficients on meduc and feduc both need to be accounted for. The predicted difference in education between B and A is .131(4) + .210(4) = 1.364.3.3 (i) If adults trade off sleep for work, more work implies less sleep (other things equal), so 1β < 0. (ii) The signs of 2β and 3β are not obvious, at least to me. One could argue that more educated people like to get more out of life, and so, other things equal, they sleep less (2β < 0). The relationship between sleeping and age is more complicated than this model suggests, and economists are not in the best position to judge such things. (iii) Since totwrk is in minutes, we must convert five hours into minutes: ∆totwrk = 5(60) = 300. Then sleep is predicted to fall by .148(300) = 44.4 minutes. For a week, 45 minutes less sleep is not an overwhelming change. (iv) More education implies less predicted time sleeping, but the effect is quite small. If we assume the difference between college and high school is four years, the college graduate sleeps about 45 minutes less per week, other things equal. (v) Not surprisingly, the three explanatory variables explain only about 11.3% of the variation in sleep . One important factor in the error term is general health. Another is marital status, and whether the person has children. Health (however we measure that), marital status, and number and ages of children would generally be correlated with totwrk . (For example, less healthy people would tend to work less.)3.4 (i) A larger rank for a law school means that the school has less prestige; this lowers starting salaries. For example, a rank of 100 means there are 99 schools thought to be better. (ii) 1β > 0, 2β > 0. Both LSAT and GPA are measures of the quality of the entering class. No matter where better students attend law school, we expect them to earn more, on average. 3β, 4β > 0. The number of volumes in the law library and the tuition cost are both measures of the school quality. (Cost is less obvious than library volumes, but should reflect quality of the faculty, physical plant, and so on.) (iii) This is just the coefficient on GPA , multiplied by 100: 24.8%. (iv) This is an elasticity: a one percent increase in library volumes implies a .095% increase in predicted median starting salary, other things equal. (v) It is definitely better to attend a law school with a lower rank. If law school A has a ranking 20 less than law school B, the predicted difference in starting salary is 100(.0033)(20) = 6.6% higher for law school A.3.5 (i) No. By definition, study + sleep + work + leisure = 168. Therefore, if we change study , we must change at least one of the other categories so that the sum is still 168. (ii) From part (i), we can write, say, study as a perfect linear function of the otherindependent variables: study = 168 - sleep - work - leisure . This holds for every observation, so MLR.3 violated. (iii) Simply drop one of the independent variables, say leisure :GPA = 0β + 1βstudy + 2βsleep + 3βwork + u .Now, for example, 1β is interpreted as the change in GPA when study increases by one hour, where sleep , work , and u are all held fixed. If we are holding sleep and work fixed but increasing study by one hour, then we must be reducing leisure by one hour. The other slope parameters have a similar interpretation.3.6 Conditioning on the outcomes of the explanatory variables, we have 1E()θ = E(1ˆβ + 2ˆβ) = E(1ˆβ) + E(2ˆβ) = β1 + β2 = 1θ.3.7 Only (ii), omitting an important variable, can cause bias, and this is true only when the omitted variable is correlated with the included explanatory variables. The homoskedasticity assumption, MLR.5, played no role in showing that the OLS estimators are unbiased.(Homoskedasticity was used to obtain the usual variance formulas for the ˆjβ.) Further, the degree of collinearity between the explanatory variables in the sample, even if it is reflected in a correlation as high as .95, does not affect the Gauss-Markov assumptions. Only if there is a perfect linear relationship among two or more explanatory variables is MLR.3 violated.3.8 We can use Table 3.2. By definition, 2β > 0, and by assumption, Corr(x 1,x 2) < 0. Therefore, there is a negative bias in 1β: E(1β) < 1β. This means that, on average across different random samples, the simple regression estimator underestimates the effect of the training program. It is even possible that E(1β) is negative even though 1β > 0.3.9 (i) 1β < 0 because more pollution can be expected to lower housing values; note that 1β is the elasticity of price with respect to nox . 2β is probably positive because rooms roughly measures the size of a house. (However, it does not allow us to distinguish homes where each room is large from homes where each room is small.) (ii) If we assume that rooms increases with quality of the home, then log(nox ) and rooms are negatively correlated when poorer neighborhoods have more pollution, something that is often true. We can use Table 3.2 to determine the direction of the bias. If 2β > 0 and Corr(x 1,x 2) < 0, the simple regression estimator 1β has a downward bias. But because 1β < 0,this means that the simple regression, on average, overstates the importance of pollution. [E(1β) is more negative than 1β.] (iii) This is what we expect from the typical sample based on our analysis in part (ii). The simple regression estimate, -1.043, is more negative (larger in magnitude) than the multiple regression estimate, -.718. As those estimates are only for one sample, we can never know which is closer to 1β. But if this is a “typical” sample, 1β is closer to -.718.3.10 (i) Because 1x is highly correlated with 2x and 3x , and these latter variables have large partial effects on y , the simple and multiple regression coefficients on 1x can differ by large amounts. We have not done this case explicitly, but given equation (3.46) and the discussion with a single omitted variable, the intuition is pretty straightforward.(ii) Here we would expect 1β and 1ˆβ to be similar (subject, of course, to what we mean by “almost uncorrelated”). The amount of correlation bet ween 2x and 3x does not directly effect the multiple regression estimate on 1x if 1x is essentially uncorrelated with 2x and 3x . (iii) In this case we are (unnecessarily) introducing multicollinearity into the regression: 2x and 3x have small partial effects on y and yet 2x and 3x are highly correlated with 1x . Adding2x and 3x like increases the standard error of the coefficient on 1x substantially, so se(1ˆβ) is likely to be much larger than se(1β).(iv) In this case, adding 2x and 3x will decrease the residual variance without causingmuch collinearity (because 1x is almost uncorrelated with 2x and 3x ), so we should see se(1ˆβ) smaller than se(1β). The amount of correlation between 2x and 3x does not directly affectse(1ˆβ).3.11 From equation (3.22) we have111211ˆ,ˆni ii ni i r yr β===∑∑where the 1ˆi rare defined in the problem. As usual, we must plug in the true model for y i :1011223311211ˆ(.ˆni i i i ii ni i r x x x u r βββββ==++++=∑∑The numerator of this expression simplifies because 11ˆni i r=∑ = 0, 121ˆni i i r x =∑ = 0, and 111ˆni i i r x =∑ = 211ˆni i r =∑. These all follow from the fact that the 1ˆi rare the residuals from the regression of 1i x on 2i x : the 1ˆi rhave zero sample average and are uncorrelated in sample with 2i x . So the numerator of 1β can be expressed as2113131111ˆˆˆ.nnni i i i i i i i rr x r u ββ===++∑∑∑Putting these back over the denominator gives13111113221111ˆˆ.ˆˆnni i ii i nni i i i r x rur r βββ=====++∑∑∑∑Conditional on all sample values on x 1, x 2, and x 3, only the last term is random due to its dependence on u i . But E(u i ) = 0, and so131113211ˆE()=+,ˆni i i ni i r x r βββ==∑∑which is what we wanted to show. Notice that the term multiplying 3β is the regressioncoefficient from the simple regression of x i 3 on 1ˆi r.3.12 (i) The shares, by definition, add to one. If we do not omit one of the shares then the equation would suffer from perfect multicollinearity. The parameters would not have a ceteris paribus interpretation, as it is impossible to change one share while holding all of the other shares fixed. (ii) Because each share is a proportion (and can be at most one, when all other shares are zero), it makes little sense to increase share p by one unit. If share p increases by .01 – which is equivalent to a one percentage point increase in the share of property taxes in total revenue –holding share I , share S , and the other factors fixed, then growth increases by 1β(.01). With the other shares fixed, the excluded share, share F , must fall by .01 when share p increases by .01.3.13 (i) For notational simplicity, define s zx = 1();ni i i z z x =-∑ this is not quite the samplecovariance between z and x because we do not divide by n – 1, but we are only using it to simplify notation. Then we can write 1β as11().niii zxz z ys β=-=∑This is clearly a linear function of the y i : take the weights to be w i = (z i -z )/s zx . To show unbiasedness, as usual we plug y i = 0β + 1βx i + u i into this equation, and simplify:111011111()()()()()nii i i zxnni zx i ii i zxniii zxz z x u s z z s z z u s z z us ββββββ====-++=-++-=-=+∑∑∑∑where we use the fact that 1()ni i z z =-∑ = 0 always. Now s zx is a function of the z i and x i and theexpected value of each u i is zero conditional on all z i and x i in the sample. Therefore, conditional on these values,1111()E()E()niii zxz z u s βββ=-=+=∑because E(u i ) = 0 for all i . (ii) From the fourth equation in part (i) we have (again conditional on the z i and x i in the sample),2111222212()()()()()n niiii i i zxzxnii zxz z u zz Var u Var Varss z z s βσ===--==-=∑∑∑because of the homoskedasticity assumption [Var(u i ) = σ2 for all i ]. Given the definition of s zx , this is what we wanted to show.(iii) We know that Var(1ˆβ) = σ2/21[()].ni i x x =-∑ Now we can rearrange the inequality in the hint, drop x from the sample covariance, and cancel n -1everywhere, to get 221[()]/ni zx i z z s =-∑ ≥211/[()].ni i x x =-∑ When we multiply through by σ2 we get Var(1β) ≥ Var(1ˆβ), which is what we wanted to show.CHAPTER 44.1 (i) and (iii) generally cause the t statistics not to have a t distribution under H 0.Homoskedasticity is one of the CLM assumptions. An important omitted variable violates Assumption MLR.3. The CLM assumptions contain no mention of the sample correlations among independent variables, except to rule out the case where the correlation is one.4.2 (i) H 0:3β = 0. H 1:3β > 0. (ii) The proportionate effect on salary is .00024(50) = .012. To obtain the percentage effect, we multiply this by 100: 1.2%. Therefore, a 50 point ceteris paribus increase in ros is predicted to increase salary by only 1.2%. Practically speaking, this is a very small effect for such a large change in ros . (iii) The 10% critical value for a one-tailed test, using df = ∞, is obtained from Table G.2 as 1.282. The t statistic on ros is .00024/.00054 ≈ .44, which is well below the critical value. Therefore, we fail to reject H 0 at the 10% significance level. (iv) Based on this sample, the estimated ros coefficient appears to be different from zero only because of sampling variation. On the other hand, including ros may not be causing any harm; it depends on how correlated it is with the other independent variables (although these are very significant even with ros in the equation).。