The Training of Teachers of a Foreign Language

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:432.67 KB

- 文档页数:90

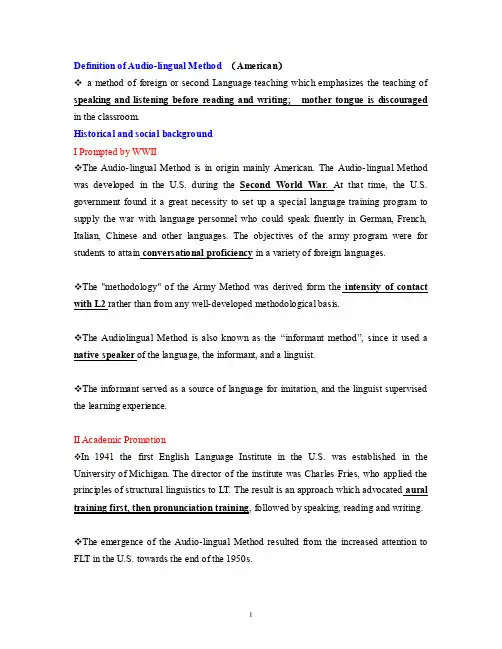

Definition of Audio-lingual Method (American)a method of foreign or second Language teaching which emphasizes the teaching of speaking and listening before reading and writing; mother tongue is discouraged in the classroom.Historical and social backgroundI Prompted by WWIIThe Audio-lingual Method is in origin mainly American. The Audio-lingual Method was developed in the U.S. during the Second W orld W ar. At that time, the U.S. government found it a great necessity to set up a special language training program to supply the war with language personnel who could speak fluently in German, French, Italian, Chinese and other languages. The objectives of the army program were for students to attain conversational proficiency in a variety of foreign languages.The "methodology" of the Army Method was derived form the intensity of contact with L2 rather than from any well-developed methodological basis.The Audiolingua l Method is also known as the “informant method”, since it used a native speaker of the language, the informant, and a linguist.The informant served as a source of language for imitation, and the linguist supervised the learning experience.II Academic PromotionIn 1941 the first English Language Institute in the U.S. was established in the University of Michigan. The director of the institute was Charles Fries, who applied the principles of structural linguistics to LT. The result is an approach which advocated aural training first, then pronunciation training, followed by speaking, reading and writing.The emergence of the Audio-lingual Method resulted from the increased attention to FLT in the U.S. towards the end of the 1950s.III Political PromotionThe need for a radical change and rethinking of FLTM was promoted by the launching of the 1st Russian satellite i n 1957.The US government acknowledged the need for a more intensive effort to teach a foreign language in order to prevent American from becoming isolated from scientific advances made in other countries.IV the OutcomeThis need made LT specialists set about developing a method that was applicable to conditions in U.S. college and university classrooms. They draw on the earlier experiences of the army programmes and the Aural-Oral or Structural Approach developed by Fries and his colleagues, adding insights taken from behaviourist psychology.•Structural linguistics views language as a system of structurally related elements (such as phonemes, morphemes, words, structure, and sentence types) for the expression of meaning.•The grammatical system consists of a list of grammatical elements and rules for their linear combination into words, phrases and sentences.•According to a structural view, language has the following characteristics in the Audiolingual Method:(1)Elements in a language are produced in a rule-governed (structured ) way.(2)Language samples could be exhaustively described at any structural level ofdescription.(3)Language is structured like a pyramid, that is, linguistic levels are system withinsystems.•The structural linguists believed that the primary medium of language is oral. Thisview of language offered the foundations for the Audio-lingual Method in language teaching in which speech was given in a priority.•The Audio-lingual Method is the first theories to recommend the development ofa language teaching theory on declared linguistic and psychological principles. TheoryTheory of learning•Like structural linguistics, behaviorism is also anti-mentalistic, that is, it does not believe that a human being possesses a mind which has consciousness, ideas, etc, and that the mind can influence the behavior of the body.•Behaviorism tires to explain how an external event (a stimulus) caused a change in the behavior of an individual (a response) without using concepts like “mind” or “ideas” or any kind of mental behavior.•Behaviorist psychology states that human and animal behavior can and should be studied in terms of physical processes only.•To the behaviorists, the human being is an organism capable of a wide repertoire of behaviors.•occurrence of these behaviors is dependent upon three crucial elements in learning:①stimulus②response③reinforcement•According to the Audio-lingual Method, learning consists of stimulus-response connections.•According to the Audio-lingual Method, learning is described as the formation of association between responses.• To apply this theory to language learning is to identify the organism as the FL learner, the behavior as verbal behavior, the stimulus as what is taught (language input), the response as the learner’s reaction to the stimulus, and the reinforcement as the approval or praise (or discouragement) of the teacher or students.•According to this behaviorist psychology, learning a language is a process of acquiring a set of appropriate language stimulus-response chains, a mechanical process of habit formation.•This theory of learning is particularly associated with the American psychologist B.F. Skinner-----a famous Harvard behaviorist who believes that verbal behavior is the same as any other fundamental respect of non-verbal behavior.•According to the behaviorist, a habit is formed when a correct response to a stimulus is consistently rewarded.•The habit therefore is the result of stimulus, correct response and reward occurring again and again.•According to Skinner, reward was much more effective than punishment in a teaching situation.•In an audiolingual classroom, teachers are encouraged to show approval for each and every correct performance by their students, and every drill is designed so that the possibility of making mistakes is minimized, engineering success for the students.Basic theoretical principles ( theory of language)•The five slogans (Moulton, 1961) which express the basic theoretical principles of the Audiolingual Method. They reflect the influence of structural linguistics and behaviorist psychology in language teaching:①language is speech, not writing;② a language is what its native speakers say, not what someone thinks they ought to say;③languages are different;④ a language is a set of habits;⑤teach the language, not about the language is a principle of the Audio-lingualMethod.•This five principles became the tenets of language teaching doctrine during the post-war decades.RolesLearner rolesLessons in the classroom focus on the correct imitation of the teacher by the learners. Not only are the learners expected to produce the correct output, but attention is also paid to correct pronunciation. Although correct grammar is expected in usage, no explicit grammatical instruction is given. Furthermore, the target language is the only language to be used in the classroom.Teacher rolesThe Audio-lingual Method is a teacher- dominated model where the teacher role ismost crucial in the instruction of the language.According to the linguist Brooks “a teacher ” must be trained to introduce, sustain and harmonize the learning of the four skills in this order : learning, speaking, reading , writing “ and in the Audio-lingual Method , the teacher “controls the direction and pace and monitors and corrects the learners performance ”Instructional materialActive verbal interactions between teachers and learners and use of materials such as tape recorders and audiovisuals equipments to assist the teacher in the classroom play a central role in teaching a second language.In Audio-lingual Method the target language should be the medium of instruction and/or use and translations o f the native language should be discouraged.CommentsMeritsCombining language and images togethe r and putting them into language teaching, which cultivates the learner’s ability of thinking in target languageSetting out to meet the learner’s direct communicative competenc eFostering the learner’s ability of using language flexibly according to speci fic context situationHelping the learner to grasp target language naturally and firmlyDefects:Over emphasizing the principle of entire structureCutting the connection between the spoken and written form of the language apart artificiallyPaying too much attention to the role of audio-lingual aspect, without appropriate use of the mother tongueOverstressing language form s instead of actual communicative content (pseudofunctional)。

外国老师在中国的英语作文The Role of Foreign Teachers in ChinaForeign teachers play a significant role in the educational landscape of China. Their presence in schools and universities not only enriches the learning experience but also bridges cultural gaps. In this essay, I will discuss how foreign teachers contribute to Chinese education and the benefits they bring to students.Firstly, foreign teachers bring diverse perspectives to the classroom. They introduce students to different cultures, customs, and ways of thinking. This exposure helps students develop a broader worldview and fosters a greater understanding of global issues. For example, a foreign teacher from the United States might share insights about American culture, history, and current events, which can stimulate discussions and enhance students' global awareness.Secondly, foreign teachers provide valuable language practice. English is an important international language, and having native speakers as teachers allows students to improve their pronunciation, fluency, and conversational skills. Foreign teachers often use engaging methods, such as interactive activities and real-life scenarios, to make language learning more effective and enjoyable. This practical experience helps students gain confidence in using English in various situations.Moreover, foreign teachers contribute to the professional development of local educators. By collaborating with Chinese teachers, they share innovative teaching techniques and educational resources. This exchange of knowledge can lead to the adoption of new methods that enhance the overall quality of education. Additionally, foreign teachers often participate in workshops and training sessions, providing valuable insights that benefit the entire school community.Furthermore, the presence of foreign teachers fosters cross-cultural friendships and mutual respect. When students interact with teachers from different countries, they learn to appreciate diversity and build relationships with people from various backgrounds. These experiences promote tolerance and cultural sensitivity, which are essential skills in an increasingly interconnected world.In conclusion, foreign teachers play a crucial role in enhancing education in China. They bring diverse perspectives, provide valuable language practice, contribute to the professional growth of local teachers, and promote cross-cultural understanding. Their contributions are instrumental in preparing students for a globalized future. Therefore, the presence of foreign teachers in Chinese schools is both valuable and beneficial.。

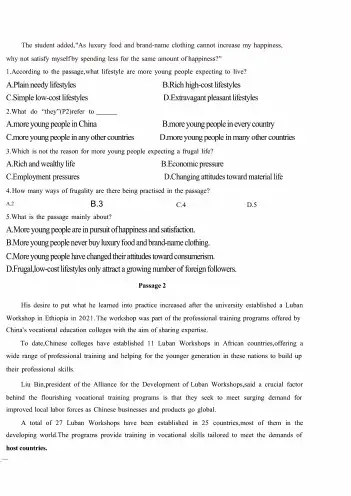

The student added,"As luxury food and brand-name clothing cannot increase my happiness,why not satisfy myselfby spending less fbr the same amount of h appiness?'11.According to the passage,what lifestyle are more young people expecting to live?A.Plain needy lifestylesB.Rich high-cost lifestylesC.Simple low-cost lifestylesD.Extravagant pleasant lifestyles2.What do C4they,,(P2)refer toA.more young people in ChinaB.more young people in every countryC.more young people in any other countriesD.more young people in many other countries3.Which is not the reason for more young people expecting a frugal life?A.Rich and wealthy lifeB.Economic pressureC.Employment pressuresD.Changing attitudes toward material life4.How many ways of frugality are there being practised in the passage?A2 B.3 C.4 D.55.What is the passage mainly about?A.M ore young people are in pursuit ofhappmess and satisfection.B.M ore young people never buy luxury food and brand-name clothing.C.M ore young people have changed their attitudes toward consumerism.D.F rugal,low-cost lifestyles only attract a growing number of foreign followers.Passage2His desire to put what he learned into practice increased after the university established a Luban Workshop in Ethiopia in2021.The workshop was part of the professional training programs offered by China's vocational education colleges with the aim of sharing expertise.To date,Chinese colleges have established11Luban Workshops in African countries,offering a wide range of professional training and helping fbr the younger generation in these nations to build up their professional skills.Liu Bin,president of the Alliance for the Development of Luban Workshops,said a crucial factor behind the flourishing vocational training programs is that they seek to meet surging demand fbr improved local labor forces as Chinese businesses and products go global.A total of27Luban Workshops have been established in25countries,most of them in the developing world.The programs provide training in vocational skills tailored to meet the demands of host countries.2024年河南省普通高等学校选拔优秀专科毕业生进入本科阶段学习考试公共英语题号一二三四五六七八总分分值Part I Reading Comprehension(2x20)Directions:There are4passages in this part.Each passage is followed by some questionsor incomplete sentences.For each ofthem there are4choices marked A.B.C and D.You should decide on the best choice and mark the corresponding letter on the Answer Sheet.Passage1Since ancient times,frugality has been one of the traditional virtues among Chinese people. Following this traditional way of life,more young people in China are now frugal,low-lost lifestyles in order to spend less and save more.They are beginning to realize and project the pitfalls of consumerism,believing that simplicity can bring happiness and satisfaction.Economic and employment pressures,as well as changing attitudes toward material life,and also resulting in more young people turning their backs on extravagance and waste.Frugality is being practiced in a number of ways.Some young people choose discounts and low priced goods,while others are replacing well-known brands with those that are cost-effective.Some are cautious when buying nonessential items,while others say they save all they can in order to make important purchases.He Jiazheng,22,a college student,said he spends about10yuan on each meal and no more than 100yuan on each item of clothing.He,who is studying economics,said his pursuit of frugality stems from the idea of"realizing maximum happiness through minimum expenditure"Another crucial factor underpinning the popularity of the workshops is the deepening cooperationbetween China and countries taking part in the Belt and Road Initiative,or BRI."Advancing the BRI gave rise to the need for Luban Workshops,which has also given impetus to the initiative."Liu said.Most of the workshops are located at vocational colleges in host countries,and they are usually established through partnerships between such colleges in China and their local counterparts.The Chinese institutions share their equipment,teaching methods and materials,and provide training fbr teachers.Since the first Luban Workshop outside China was set up in Thailand in2016,the27workshops established to date offer degrees to more than6,100students and temporary training programs fbr some 31,500students.Liu said the workshops have also provided training fbr more than4.000teachers from host countries.6.Up to now,how many Luban workshops have been set up in African countries.A. 11B.24C.25D.277.About Luban workshops what is the purpose of the drive by China.A.T o promote mtemational cooperation on high educationB.T o promote cross-institution cooperation on high educationC.To promote international cooperation on vocational educationD.T o promote cross-mstitution cooperation on vocational education8.According to the passage,which help is not offered by the Chinese colleges?A.Sharing equipmentB.Providing financial supportsC.P rovidmg training for teachersD.S haring teaching methods and materials9.W hy did China start the first Luban workshop in Africa?A.T o help maintain and operate the railwayB.T o help train talent,which is in short supplyC.T o help train students.which are in short supplyD.T o help tram senior engmeers,which are in short supply10.W hat is the passage trying to tell us?ALuban workshops are specially made programs provided by ChinaB.Luban workshops have offered degrees to students in ThailandC.L uban workshops have tramed first24students in DjiboutiD. L uban workshops have benefit to Africa vocational educationPassage3Shenzhen is trying to be the first choice among Chinese cities fbr global brands launching flagship stores in the country and a shop window of global brands,according to a recently released action plan on expanding consumption,improving consumption quality and creating new demands(2021-2023).The plan put forward by the Shenzhen Municipal Commerce Bureau also stressed building local brands to enhance local products'prestige and influence.First-shop economy and brand economy are important indexes reflecting business innovation and influence of a city,and now play driving roles in stimulating consumption.The population structure in which young people take a majority enables Shenzhen to be the first choice for some well-known brands to establish presence in South China market,H Zeng Li.supervisor with the research firm JLL South China,said.Partial statistics from retail business data platform showed a total of72brands launched their flagship stores in Shenzhen from January to June.Among the shops,13were the brands' first shops in the country,?5were the first in South China and34were the first in Shenzhen.Statistics from the city's commerce bureau also showed that26shopping centers introduced97flagship stores of well-known brands to Shenzhen in2020.Of the97brands,41are in cosmetics and fashion business, and39engage in catering,including bakeries and beverages.which young people favor.lt is estimated that Shenzhen will open20complexes with these new business modes and more feature brands will bring new experiences to local consumers in the second half of this year.In2020,in a move to be a central city of global consumption,Shenzhen unveiled measures to stimulate the development of first-shop economy to attract famous global brands to set up shops in Shenzhen.In April this year,the Shenzhen Municipal Commerce Bureau unveiled measures on building international consumption centers.Among the measures,the property owners that introduced first shops or flagship stores of famous brands at home and abroad will receive rewards of500.000yuan for a retail outlet and200,000yuan fbr a catering outlet.The reward for one property owner or operator will be no more than3milion yuan a year.For product launching or shop launching activities of well-known Shenzhen brands,the government will give standard subsidies of30percent of the actual cost with a cap of3million yuan.—2—1l.What makes it possible for the121new flagship stores to open in Shenzhen?A.T he city can provide data to these fbr foreign and domestic busmessB.T he city n s consumption has made a steady and strong increase.C.T he city's consumption mainly depends on foreign and domestic businessesD.T he city is famous as an international consumption center in South China.12.34stores open in Shenzhen for the first time,which showsA.a strong appealB.t o leading innovationC.a proper policyD.i n driving plan13.What is the meaning of the word"catering"?A.T he work ofprovidmg make-upB.T he work of p roviding costumeC.The work ofprovidmg entertainmentD.T he work ofproviding food and drinks14.A mong these new stores,which sector accounts for the highest percentage of first stores?A.cateringB.c lothingC.leisure activityD.l ifestyle15.Which is the NOT following related to"first store economy"measures?A To reward famous global brands fbr opening their flagship shops in Shenzhen.B.T o reward Shenzhen's commerce bureau fbr its contribution.C.T o reward property owners for mtroducmg flagship shop of f amous domestic brands.D.T o reward property owners for mtroducing flagship shop of famous global brands.Passage4Xinjiang reservoir optimizes water useBy CHENG SI in Aksu,Xinjiang China Daily Updated:2023-09-0900:00Aksu in the Xinjang Uygur autonomous region is making efforts to optimize the use of water resources by building a world-class reservoir project,which aims to reduce droughts and floods andreduce their influence on local economic development and people's livelihoods,as well as generate powerLocated at the junction of Wensu and Wushi counties of Aksu,the Dashixia water reservoir project started construction in December2017,and is expected to test its water-holding function in October2025 and finish all construction around October2026.This area has a very harsh climate and complicated geological conditions,posing great challenges to our work,"said Huang Jin,vice-general manager of Xinjiang Gezhouba Dashixia Reservoir Development Co-the company in charge of construction.He said that the project requires high-quality construction because of the height of the dam,with its highest point designed to reach247meters,in addition to its high flow rate of floodwater release and higher-level resistance to earthquakes.To better monitor the quality of construction work and collect construction data,the company channeled around30million yuan(S4.1million)to build a smart monitoring system in late2021."The application of the system can not only help us save human resources,but reduce the risk of human error.We can monitor the construction work during the whole process,"said LiJiandong,the company's director of technology management department."For example,we can trace the whole process of dam material from the original mining,transportation and its placement through the system."He added that the system is in trial operation so far,and will be put into service around October to December.Seeing the project in smooth operation.the45-year old Xu Shumei,a senior technician from the company,feel her efforts and contributions are rewarded."I've worked in Xinjiang since1999after finishing my education in Chongqing,my hometown. And I started to work for the project around four years ago,"she said.She is responsible for quality control,laboratory management and energy saving and emission reduction for the project."Ive never regretted serving in this industry,and it may be a once-in-a-lifetime chance to get involved in such a world-class project.But I owe a lot to my daughter and parents who need my care because of my work,"she said.16.Which is not the purpose of building a world-class reservoir project in Aska?To reduce droughtsA.B.To reduce floodsC.T o generate powerD.T o reduce power generation17.When is the Dashixia water reservoir expected to finish all construction?.A.A round December2017B.Around late2021C.Around October2025D.Around October202618.How did the company better monitor the quality of construction work?A.T o manage laboratory energyB.To build a smart monitoring systemC.T o protect the right oflaborersD.T o prohibit the risk ofhuman errors19.What can you infer from this passage?A.X u Shumei is a j unior technician in charge of q uality.B.X u Shumei take less care ofhis daughter and parents.C.X u Shumei is a workaholic in eyes ofher relatives.D.X u Shumei has been the company director fbr4years.20.What is the passage mainly about?A.T he Dashixia water reservoir can generate power.B.B.The Dashixia water reservoir can reduce droughtC.T he Xinjiang reservoir can reduce energy and emission.D.D.The Xiryiang reservoir is tying to optimize water resources.Part II Cloze(1x20)Directions:There are20blanks in thefbllowingpassage.For each ofthe blank there are fourchoices marked A,B,C and D.You should choose the ONE that best fits into the passage and mark the corresponding letter on the Answer Sheet.Going to the hospital is a tough and tiring experience for many elderly citizens.Especially, 21who live alone,have limited mobility,or are unfamiliar_22_smartphone use.Companies that provide workers to accompany individuals to the hospital and_23_patients throughout the process_24_to profit as demand rises.This type of service is known as Peizhen,_25_translates to"medical treatment accompaniment"The market is quite segmented.The elderly,_26_certain enterprise customers_27_,and young people living alone in the city,_28_the majority other demand.The_29_typically have more stringent requirements,such as health consultation and expert reservation.The_3O rate ranges from20yuan to100yuan,31on the service content,requirements and staff background,with those with medical backgrounds charging more."Peizhen is a brand-new industry.Our company's primary market is older individuals_32_buy the service for themselves or whose children_33_the service,'1said Yu Weisheng,manager of Shanghai Quanchengjiujiu Health Service Co,whose workers can escort three to four old individuals to the hospital every day.H We_34_collaborate with the district administrations in some neighborhoods,which_35_theelderly service,'1s aid Yu."Typically,elderly people must travel to a_36_hospital for out-patient,rehabilitation therapy,and dialysis services.They engage our workers to assist them_37_they do not have children or the children are not living with them,"Yu explainedYu wants the government s8_a series of access qualification,training,and certification programs to improve management and assure the industry's_39_development."It is a new business;there are no rules governing staff qualification,background,pricing,risk management,patients'medical records,_40_privacy protection,"he said."Service providers should be trained and tested in psychology,medical knowledge,and other necessary skills to ensure service quality and safety,"he stated.21.A.t hat B.these C.someone D.those22.A.t o B.with C.on D.from23.A.insisting B.assist C.insist D.assisting24.A.is beginning B.is planning C.are beginning D.are planning—4—The move allows similar steps taken recently in Finland,a country that is widely regarded as having one of t he best education systems in the world.France has also had a ban in place since September2O18.Newspaper Le Figaro reported that before the ban,around30to40percent of all sanctions issued in senior schools related to the use of m obile phones in the classroom.()41.Smart devices are to be banned from Dutch classroom in the new year.()42.The disabled students are banned to use smart devices in the Netherlands.()43.Robbert Dijkgraaf approved of t he use of smart devices in the Netherlands.()44.Finland is widely regarded as having the best education system in the world.()45France has also issued a similar official rule concerning the use of smart devices.Part IV Translation(40points)Section A English-Chinese Translation(2x5)Directions:This part,mumbered46to50,is to test your ability to translate English into Chinese.Each sentence isfollowed byfour choices of s uggested translation marked A,B,CandD. You should decide on the best choice and mark the corresponding letter on the Answer Sheet.46.A ll our sale items are slightly imperfectA.我们所有所售的商品都非常完美B.我们所有的特价商品都略有瑕疵。

介绍陈延年英语作文Chen Yannian is a renowned English educator in China who has made significant contributions to the field of English language teaching and learning. Born in 1950 in Guangzhou, Chen grew up in a family that valued education and instilled in him a deep appreciation for the power of language. From a young age, he demonstrated a keen interest in English and a natural aptitude for language acquisition.After completing his primary and secondary education, Chen pursued his passion for English by enrolling at Sun Yat-sen University, where he obtained his bachelor's degree in English language and literature. His academic excellence and dedication to his studies quickly caught the attention of his professors, who recognized his potential and encouraged him to further his education.Following his undergraduate studies, Chen went on to earn a master's degree in English linguistics from the same university, cementing his status as a rising star in the field of English education. His graduate research focused on the application of linguistictheories to the teaching of English as a foreign language, a field that would become the central focus of his life's work.After completing his postgraduate studies, Chen embarked on a career as an English language educator, teaching at various universities and institutions across China. His exceptional teaching skills, innovative pedagogical approaches, and deep understanding of the challenges faced by Chinese learners of English quickly earned him a reputation as one of the most influential and respected English educators in the country.One of Chen's key contributions to the field of English education in China has been his tireless efforts to bridge the gap between theory and practice. He has consistently advocated for the implementation of teaching methodologies that are grounded in empirical research and tailored to the unique needs and learning styles of Chinese students. This has involved the development of teaching materials, the design of curriculum, and the training of English language teachers.Chen's impact on English education in China extends far beyond the classroom. He has been a prolific writer, authoring numerous books and articles on various aspects of English language teaching and learning. His publications have been widely read and cited by educators and researchers both within China and internationally,solidifying his status as a leading voice in the field.In addition to his academic and professional work, Chen has also been a tireless advocate for the promotion of English language education in China. He has served on numerous government and industry committees, providing expert advice and guidance on the development of national language policies and the implementation of English language programs. His contributions to the field have been recognized with numerous awards and accolades, including the prestigious National Teaching Excellence Award and the title of "Exemplary Teacher" from the Chinese Ministry of Education.Despite his many achievements, Chen remains humble and dedicated to his work, driven by a deep passion for helping Chinese learners of English to succeed. He continues to inspire and mentor a new generation of English educators, passing on his wealth of knowledge and experience to those who will carry on his legacy.In conclusion, Chen Yannian is a true pioneer in the field of English language education in China. His unwavering commitment to excellence, his innovative teaching approaches, and his tireless advocacy for the promotion of English language learning have made him a towering figure in the field. As Chinese learners of English continue to strive for proficiency in the language, Chen'scontributions will undoubtedly continue to shape the landscape of English education in China for generations to come.。

大学教育目的英语介绍范文(通用6篇)(经典版)编制人:__________________审核人:__________________审批人:__________________编制单位:__________________编制时间:____年____月____日序言下载提示:该文档是本店铺精心编制而成的,希望大家下载后,能够帮助大家解决实际问题。

文档下载后可定制修改,请根据实际需要进行调整和使用,谢谢!并且,本店铺为大家提供各种类型的经典范文,如工作总结、工作计划、合同协议、条据文书、策划方案、句子大全、作文大全、诗词歌赋、教案资料、其他范文等等,想了解不同范文格式和写法,敬请关注!Download tips: This document is carefully compiled by this editor. I hope that after you download it, it can help you solve practical problems. The document can be customized and modified after downloading, please adjust and use it according to actual needs, thank you!Moreover, our store provides various types of classic sample essays for everyone, such as work summaries, work plans, contract agreements, doctrinal documents, planning plans, complete sentences, complete compositions, poems, songs, teaching materials, and other sample essays. If you want to learn about different sample formats and writing methods, please stay tuned!大学教育目的英语介绍范文(通用6篇)大学教育目的英语介绍范文第一篇Why do we choose to go to middle school? Some people say that we can learn a lot of basic knowledge in middle school,while others say that only when we go to middle school can we continue to study in University.They are all right.But I think the most important thing is that during middle school, we can learn.Learning is a lifelong thing.School is the basis of learning, because it can bring us knowledge, It can also provide us with learning guidance.If we have the ability to study independently, it seems that our years in school are very short.We can study anytime and anywhere.Therefore, teaching students how to learn is the goal of middle school education.中文翻译:为什么我们选择去中学有人说我们可以在中学学到很多基础知识,而另一些人说只有我们上中学我们才能在大学里继续学习他们都是对的,但是我认为最重要的是在中学期间,我们可以学习学习学习是一件终身的事情学校是学习的基础,因为它能给我们带来知识,也能给我们提供学习的指导。

As a participant in the English teacher training program, I have gained a wealth of knowledge and experiences that have greatly influenced my understanding of teaching English as a foreign language. This article aims to share my reflections on the training program, highlighting the key takeaways and the personal growth I have experienced.First and foremost, the training program provided me with a comprehensive understanding of the principles and methods of English language teaching. Through various workshops and seminars, I learned about the importance of creating a positive and engaging learning environment, as well as the significance of tailoring teachingstrategies to meet the diverse needs of students. This knowledge has allowed me to approach my teaching career with a more confident and informed mindset.One of the most valuable aspects of the training program was the opportunity to observe and analyze experienced teachers in action. By watching them deliver lessons, I was able to identify effective teaching techniques and strategies that I could incorporate into my own teaching. Additionally, the feedback and suggestions provided by the trainers were invaluable in helping me refine my teaching methods and improve my overall performance.Another significant benefit of the training program was the emphasis on classroom management. I learned about various techniques for maintaining discipline, managing student behavior, and fostering a sense of community within the classroom. These skills are crucial for creating a conducive learning environment and ensuring that all students have the opportunity to succeed.Furthermore, the training program equipped me with the necessary tools and resources to develop my own teaching materials. I was introduced to a variety of online platforms and resources that can be used to create engaging and interactive lessons. This has allowed me to design more dynamic and engaging lessons that cater to the diverse learning styles of my students.Throughout the training program, I also had the opportunity to collaborate with fellow participants and share our experiences and insights. This collaborative approach not only helped me to expand my professional network but also provided me with fresh perspectives on teaching English as a foreign language. I learned from my colleagues' experiences and gained confidence in my own abilities as an educator.One of the most profound takeaways from the training program was the realization of the importance of continuous learning and professional development. As an English teacher, I understand that my journey is far from over, and there is always more to learn and improve upon. The training program has inspired me to stay curious and dedicated to my profession, always seeking new ways to enhance my teaching skills and knowledge.In conclusion, the English teacher training program has been an incredibly rewarding experience that has enriched my understanding of teaching English as a foreign language. From the valuable insights gained from experienced teachers to the collaborative opportunities with fellow participants, the program has provided me with the tools and confidence to excel in my teaching career. I am grateful for the knowledge and experiences I have gained, and I look forward to applying them in my future endeavors as an English teacher.。

《国际经贸高级英语(精读与翻译)》参考答案罗汉主编key to ExercisesUnit OneⅠ/1. the accumulation of physical capital indispensable to economic growth2. to import advanced equipment and know-how from abroad3. license trade accounting for 90 per cent of the total volumeof the world s trade of technology4. lack of human capital reflected in economic development5. the great impact of high technology on the adjustment of industries6. key factors driving economic growth7. the transformation from an agricultural nation into an industrial one8. the tangible and intangible factors making up the total factor productivity growth9. the improvement of educational systems lurking in technological progress10. the ratio of capital to labour in this industry11. expand the labour force and increase its education and training12. the role of the R&D department in the operations of multinational corporations13. a study report analyzing variations in technical progress across a large number of countries14. to incorporate quantity and models into economic analysis15. great gap in incomes between developed and developing nationsⅡ/1. Many economists attributed the rapid economic growth rate of someland desiring areas, such as HongKong and Singapore, to the enhancement of educational levels of their population. Based on this, they drew their conclusion that knowledge is the key to their economic development.2. In the 1960s, on the basis of importing much sophisticated technology andknow how from developed countries, Japan expanded its e conomy in large scales, enabling its economy to keep up with the most advanced level of the world in 20 years.3. The development of new economic theories has raised many subjects to statistics. For example, high rates of school enrollment may not translate into high rates of economic growth if the quality of education is poor, or if educated people are not employed at their potential because of distortion in the labor market.4. In 1994, after a long period of investigation and research, the famous economist Krugman presented a study report analyzing variations in technical progress across a large number of countries. He said in the report that the economic development of Asia was not based on the progress of technology, so the economy contained much foam in it. Three years later, the sudden break out of southeast Asian Economic Crisis verified his conclusion.5. People haven't hitherto come up with an ideal method to put a value on science and technology, for it is intangible to some degree.Ⅲ. In the information age, knowledge, rather than physical assets or resources, is the key to competitiveness. This is as true for the obviously konwledge intensive sectors,such as software or biotechnology, as it is for industrial age manufacturing companies or utilities.For the knowledge intensive sectors,knowledge which feeds through from research and development to innovative products and processes is the critical element. Butwith industrial age manufacturing companies or utilities, using knowledge aboutcustomers to improve service is what counts.What is new about attitudes to knowledge today is the recognition of the need to harness, manage and use it like any other asset. This raises issues not only of appropriate processes and systems, but also of how to account for knowledge in the balance sheet.In future, the value of intellectual capital will be more widely measured and reported. The measurement and reporting of key performance indicators related to intellectual capital will become a more widespread practice among major organizations, completing the financial accounts.Unit TwoⅠ/1. to crack the FORTUNE Global 5002. a collective enterprise supervised by workers3. be pessimistic about the factory s ability to absorb technology4. the incorporation (mix)of foreign management practices and Chinese nationalism5. a leading guru of Japanese quality control6. to transfer the management concepts to new acquisitions7. the dominant position in China s refrigerator market8. a case study of the management art9. to let shoddy products released to the market in large quantities10. to set the stage for the renovation of the enterprise11. the wholly-owned companies and holding companies under the control of the parent company12. to soak up the laid-offs released from state owned companies13. to sell modern refrigerator making technolog y to the factory14. the state-owned enterprises accounting for the majority of industrial enterprises15. the development of domestic pillar industriesⅡ/1. Although this joint venture has been growing very fast, it still has a long way to go to realize its goal of cracking the Fortune Global 500.2. Haier once tried to place the sample products in sight of the assembly line workers to improve the quality of the products, but now it has outgrown thispractice.3. In the early 1980s, out of every 1000 urban Chinese households, there were only two or three that owned refrigerators. With the enhancement of people's livingstandard, refrigerators have become the first big item in the households buy of many families.4. The company has 70 subsidiaries around the world, one third of which arewholly-owned, with their products sold to 108 countries and areas. In recent years, it has averaged an increase of 50% a year in revenues.5. The rapid development of collective and private enterprises will help to soak up the labour force released from poorly operated state-owned enterprises and to relieve the nation's employment burden.Ⅲ. Many managers feel uncomfortable if not actively involved in accomplishing a given job. This is said to result from a“low tolerance for ambiguity”. The manager desires to know what is happening on a moment by moment basis. A wise manager should know clearly what work must be delegated, and train employees to do it. If after training, an employee is truly unable to perform the work, then replacement should be considered. A manager should avoid reverse delegation.This happens when an employee brings a decision to the manager that the employee should make. An acceptance of reverse delegation can increase the manager'swork load and the employee is encouraged to become more dependent on the boss. Unit ThreeⅠ/1. to issue a vast amount of short term government bonds2. plenty of capital inflow to the security market in the recent period3. the preference of investors to the inflation protected treasury bonds4. to decrease the risk by hedging5. diversified portfolio6. to reach more than 50% of the initial public offering7. dilution of securities caused by the distribution of shares8. the trigger event that causes the imploding on market index9. short maturity U.S. government and corporate fixed income secu r ities10. real assets like commodities and real estate11. to avoid insider-trading charges through legal windows12. some trigger events that will charge the interest rate in the capital market13. reflect investors' wary view of the market14. shepherd the funds every step of the way15. the agriculture bonds that come back in the stock marketⅡ/1. During the past several months, the interest rate and the exchange rate have fluctuated greatly, which has brought enormous loss to many investors. But this institution overrode the adverse factors in the market and still obtained a big profit by wise hedging investments.2. The diversification of portfolio can decrease the non-systematic riskof individual securities in the portfolio efficiently, but it is unable to remove the systematic risk of the market.3. During the period of high inflation in capitalist countries between the late 1960s and late 1970s, many people tended to convert their money incomes into goods or real estate.4. One of the Bundesbank council members said that the central bank is under no immediate pressure to cut interest rates and that it needs more time to study the economic data before making a decision.5. Many experts consider that the interest rates would trend higher, because, although it is true that there is not much inflation now, wage inflation is evidentand the entire economy is in such high gear right now.Ⅲ. For all the similarities between the 1929 and 1987 stock market crashes, there are one or two vital differences. The most important of these was the reaction of the financial authorities. In 1929, the US Federal Reserve reacted to the crash by raising interest rates, effectively clamping down on credit. This caused manyotherwise healthy companies to fail simply due to cash flow problems. If onecompany failed leaving debts, many others down the line would meet the same fate. In 1987, the authorities were quick to lower interest rates and to ensure that ample credit was made available to help institutions overcome their difficulties. There were no widespread business failures and, more importantly, the economy did not enter another depression. There was a period of recession(milder than a 1930s-style depression), but this was largely due to a resurgence of inflation. The sharp interest rate cuts, and excessively hasty financial deregulation, pushed inflation higher, which in turn forced governments to reverse earlier interest rate cuts, prompting an economic slow-down.Unit FourⅠ/1. to rely heavily on monetary flexibility to reign in inflation2. to execute tight monetary policy3. to implement fiscal policy in the form of social insurance and national taxes4. to pour into economically expanding regions5. to replace their individual currencies with a single currency6. to bode well for the future of the EMU7. to control government deficits to meet Maastricht conditions8. the overvalued currency as a main barrier to export9. to refrain from dumping surplus goods abroad10. the influence of integrated economy on capital flow11. the balance-of-payments deficit warranting the devaluation policy adopted by the monetary authority12. to eliminate the economic costs associated with holding multiple currencies13. costs that must be taken into account when estimating profits14. to take advantage of the small difference between the central bank's pegged rates and market rates15. to hedge against risks coming from volatile exchange ratesⅡ/1. Ironically, Europe will see an increase in economic specialization along with the European unification process.2. The European Central Bank will face a dilemma when two member countries both badly need certain monetary policies to regulate their economies but the policies they need are of opposite directions.3. A person will be called an“arbitrageur"if, to gain profits, he takes advantage of the different exchange rates on different markets, or at different times on a same market.4. The national economies of many European countries have recently been forced to fit Maastricht conditions and arbitrary deadlines, and such actions have created unnecessary economic turmoils.5. As a central bank, the Federal Reserve System currently uses its control over the money supply to keep the national inflation rates low and to expand national economies in recession.Ⅲ. Even before construction of the euro is complete, governments can point to one notable success. The past year has seen extraordinary turmoil in global financial markets. Rich country stock markets and currencies have not been spared. Yet Europe has been, comparatively speaking, a safe haven, Intra-European movements in exchange rates have been tiny. This is something that the euro-11 governments had committed themselves to, but their success could not have been taken for granted a year ago. The fact is, at a time of unprecedented financial turbulence, theforeign exchange markets regarded the promise to stabilize intra-European exchange rates as credible. Currencies have held steady and interest rates have converged: it augurs well for the transition to the new system.Unit FiveⅠ/1. a major engine of growth in Asian economy2. the structural weakness in South Korea's financial system3. to execute economic policies which adhere to IMF-aid programs4. a sharp decline in the price competitiveness of that country's exports5. the slump in the Japanese stock market6. a more advantageous position than its rivals in terms of price competitiveness7. trade disputes sparked by price distortion8. the financial panic triggered by the devaluation of Japanese yen9. to stabilize the recently turbulent capital flows10. the advantageous position of industrial countries in the world trade system11. the serious welfare losses for all nations resulted from a full scale trade war12. a USD 58 billion bailout which South Korea was forced to seek from the IMF13. the great expenditure caused by huge government institutions14. technology intensive and knowledge intensive products with high competitiveness15. the country's economy which remains mired in recessionⅡ/1. While the Asian economy regained stability, the possibility of devaluation of the HongKong dollar will be an important variable affecting the recurrence of similar economic crises in Asia.2. In order to connect the improvement of price competitiveness brought about bythe currency depreciation to a better balance of payment, internationalcooperation is as essential as are internal reforms.3. The Asian financial crisis owing to the heavily indebted banking systems,excessive government spending and over reliance on foreign loans has damaged the world economy seriously.4. Some Japanese companies began to fall out of their over reliance on loansfrom the banking system, focusing on profits and cutting out wasteful spending.5. Erupted in July 1997, the Asian financial crisis reflected the defectsin the fragile financial systems of Asian countries.Ⅲ. Like death and taxes, international economic crises cannot be avoided. Theywill continue to occur as they have for centuries past. But the alarmingly rapid spread of the 1997 Asian crisis showed these economies' vulnerability to investor skittishness. Unfortunately, there is no international“911" that emerging markets can dial when facing economic collapse. Neither the IMF nor a new global financial architecture will make the world less dangerous. Instead, countries that want toavoid a rerun of the devastating 1997—98 crisis must learn to protect themselves. And liquidity is the key to financial self help. A country that has substantial international liquidity—large foreign currency reserves and a ready source offoreign currency loans—is less likely to be the object of a currency attack. Substantial liquidity also enables a country already under a speculative siege to defend itself better and make more orderly financial adjustments. The challenge is to find ways to increase liquidity at reasonable cost.Unit SixⅠ/1. capital flight depleting a country s foreign exchange reserves2. domestic hyperinflation caused by devaluation3. to adopt expansionary fiscal policy to increase national income4. be faced with the danger of increasingly shrinking aggregate demand5. capital market harassed by liquidity trap6. to rule out the possibility of massive speculative activities7. to drive down domestic prices at the expense of economic stagnation8. the international gold standard system characterized by fixed exchange rates9. the pressure of hot money flow on currencies10. the neoclassical theory centering on the spontaneous adjustments of market11. intelligent policy makers who will use variable means to achieve economic goals12. flexible fiscal and financial policies that can help the economy out of depression13. the different dilemmas that the developing countries and the mature economies are faced with14. to sacrifice full employment to achieve high output rate15. the increased demand for this currency that will lead to the devaluation of another currencyⅡ/1. The economic turmoil in that country made the central bank and the treasury department take each other to task, which reflected the importance of the collaboration of a country s monetary and fiscal policies.2. The government has now slipped into such a dilemma that if it wants toimprove its balance of payment, it will need to lower the exchange rate, but to lower the exchange rate will lead to inflation.3. Although devaluation will magnify exports, it can also lead to the increasing foreign curren cy denominated debt;it can even cause the collapse of people's confidence in the government. Therefore, the government did not dare to adopt the devaluation policy without careful consideration.4. The increase of foreign currency denominated debt is not necessarilythe indispensable cost of economic development. Because, although it may promote economic growth in the short run, it will increase the burden of domestic enterprises and lead to imbalanced balance of payment in the long run.5. Major capitalist countries had been seeing gold standard as a symbol of strong economic power, but they were forced to give it up for good during the Great Depression.Ⅲ. Troubled Asian Economies have turned out to have many policy and institutional weaknesses. But if America or Europe should get into trouble next year or the year after, we can be sure that in retrospect analysts will find equally damning things to say about Western values and institutions. And it is very hard to make the case that Asian policies were any worse in the 1990s than they had been in previous decades, so why did so much go so wrong so recently?The answer is that the world became vulnerable to its current travails not because economic policies had not been reformed, but because they had. Around the worldcountries responded to the very real flaws in post Depression policy regimes bymoving back toward a regime with many of the virtues of pre-Depressionfree-market capitalism. However, in bringing back the virtues of old fashioned capitalism, we also brought back some of its vices, most notably a vulnerability both toinstability and sustained economic slumps.Unit SevenⅠ/1. government reforms compatible with a country's development program2. lay emphasis on the resolution of government involvement3. the state induced transfer of wealth from the rich to the less fortunate4. to finance the development of public sectors5. a sharp decrease in the subsidy expenditure of a welfare state6. to minimize the public expenditure of this country7. the growth rate of gross fixed asset formation8. heavy interest obligations resulting from huge interest payments9. a certain share of shadow economy in the government performance10. to avoid increasing government spending and lowering the economic growth rates11. the benchmark to assess the scope for reducing the size of government12. be of growing importance in government reforms13. to facilitate adjustment to the new economic environment14. the detrimental short-run effects of reforms on some groups15. the protectionist and competitive devaluation policies administered by some industrial countriesⅡ/1. Over the years, opinions about the role of state have been changing, andpolitical institutions have been changing as well, to accommodate the demand for more state involvement in the economy.2. It's generally believed that even if welfare states cut down the hugewelfare expenditures, they can't necessarily solve their serious economic problems such as large budget deficits and hyperinflation.3. The government carried out the expansionary fiscal policy, which resulted inthe increase of budget deficits. To compensate the deficits, it should take certain measures, such as issuing bonds or increasing the money supply.4. Many industrial countries face the dilemma during their reforms between high inflation rates and low unemployment rates, so they must consider all around to minimize the losses.5. Radical reforms must aim at maintaining public sector objectives while reducing spending. In this process, the role of the government will change from the provider to the overseer or the regulator of activities.Ⅲ. Modern societies have accepted the view that governments must play a larger role in the economy and must pursue objectives such as income redistribution andincome maintenance. The clock cannot be set back and, in fact, it should not be. For the majority of citizens, the world is certainly a more welcoming place now than it was a century ago. However, we argue that most of the important social and economic gains can be achieved with a drastically lower level of public spendingthan that which prevails today. Perhaps the level of public spending does not needto be much higher than, say, 30 percent of GDP to achieve most of the importantsocial and economic objectives that justify government intervention. Achievingthis expenditure level would require radical reforms, a well-functioning private market, and an efficient regulatory role for the government.Unit EightⅠ/1. winds of reform in Japan s banking sector2. the amended Bank of Japan Law in line with the global standards for autonomy and transparency3. touch on the paramount goal in the sphere of monetary policies4. charge the central bank with maintaining price stability and nurturing a secure credit system5. generate unnecessary panics in the financial markets6. the execution of monetary policies independent of the bureaucracy7. the institutions in charge of formulating the interest rate policies8. a discount rate at a historical low of 0.5%9. to keep maintaining and nurturing the credit system in accordance with the state policy10. in the spheres of fiscal and monetary policies11. the new economic law entering force this year12. in the context of propelling economic reforms13. to strengthen the government s functions through fiscal policies14. key measures which have won confidence from the market15. the implementation of a merit based promotion systemⅡ/1. It is no overstatement to say that the bad accounts in Japan's banks have accumulated to a very high level.2. The central bank's quasi-bureaucratic status has stymied its normal operations, so many economists call for the enhancement of its autonomy in accordance with the global standards.3. It has been normal for bank shares to march in line with movements in net interest margins, which means bank shares tend to rise as net margins widen and fall as the latter narrow.4. Japan's bank shares are in a different position from their American counterparts: America s bank shares have already risen sharply thanks to the country's full-fledged economic recovery, while Japan's bank shares are still weak as the banks struggle to get to grips with their bad debts.5. Runs on the banks proliferated and a sharp fall in bank loans followed, before the non-performing loans, amounting to 30% of bank assets, were taken over by the state in 1997.Ⅲ. How fast Japan's financial system seems to be reforming. Barely a week goes by without news of another merger between Japan s huge but troubled financial firms. Deregulation is the spur. Three years ago the government announced a “Big Bang"for the country's financial-services industry. This would tear down firewallsthat had largely stopped insurance companies, banks and stockbrokers from competing in each other's patches. It was also meant to put an end to arbitrary, stiflingand often corrupt supervision.The biggest reason for deregulation in this way was that Japan's incestuous,Soviet'style financial system was hopelessly bad at allocating credit around the economy. The massive bad-loan problems that have plagued the country's banks for most of the 1990s are merely one symptom of an even bigger ill. Even so, there was wide spread scepticism that the government would go through with the cure. It deserves some credit, therefore, for largely sticking to its plans.Unit NineⅠ/1. the most commonly used measures of income distribution2. the shift from labour to capital markets3. specialization in production and the dispersion of specialized production processes4. the widening gap between the wages of skilled workers and those of unskilled workers5. new production techniques biased toward skilled labor6. economic inefficiency and distortions retarding growth7. sustainable growth and a viable balance of payments policy8. a broadly based, efficient and easily administered tax system9. reduce disparities in human capital across income groups10. targeted programs consistent with the macroeconomic framework11. constitutional rules on revenue sharing12. to promote equality of opportunities through deregulating economy13. cash compensation in lieu of subsidies14. stimulate the use of public resources and the overall economic growth15. take effective measures to promote employment and equityⅡ/1. Much of the debate about income distribution has centered on wage earnings, which have been identified as an important factor in the overall distribution of incomes. But in Africa and Latin America, unequal ownership of land is a factor that cannot be ignored.2. Globalization has linked the labor, product and capital markets of theeconomies around the world and has indirectly led to specialization in production and the dispersion of specialized production processes to geographically distant locations.3. Although fiscal policies are usually viewed as the principal vehicle for assisting low-income groups and those affected by reform programs, quite a number of countries have adopted specific labor market policies in an effort to influence income distribution.4. Measures governments can take to promote equality of opportunities include deregulating the economy;setting up strong and responsible institutions, including a well functioning judicial system;reducing opportunities for corrupt practices;and providing adequate access to health and education services.5. Another important issue is whether governments should focus on outcomes—such as decreasing the number of people living in poverty, or ensuring that all members of society have equal opportunities.Ⅲ. One theory on wealth distribution indicates that irrational distribution andcorruption are the major reasons for the uneven income level. According to this theory, wealth goes through four stages of distribution—the market, the government, non governmental organizations and unlawful activities, mainly corruption. Usually the first stage of distribution—the market—will result in an uneven spread of resources, which should be redressed by the second distribution stage, the government. In the third stage, the distribution of wealth is realized through contributions and donations made by non governmental organizations. The contributions are given to the poor in the form of charity activities. Thenfollows illegal grabbing of wealth, such as robbery, embezzlement, tax evasion andbribery. Their harm to social equality and stability is enormous and cannot really be measured.Unit TenⅠ/1. to facilitate the establishment of a new form of leadership in today's corporations2. to link a corporation's developing prospective to its present business performance3. companies which forge ahead in the rather changeable world economy4. to encourage domestic enterprises to seek out opportunities to enter foreign markets5. to instill development strategies of new products into employees at all levels6. to consider the promotion in the company the criteria to judge whether one is successful or not。

介绍外国人来北京教英语作文《Foreigners Teaching English in Beijing》In recent years, more and more foreigners have come to Beijing to teach English. This has brought many benefits to the city and its people.One of the main benefits is that it provides students with a better learning environment. Foreign teachers usually have a native accent and a more natural way of speaking, which can help students improve their listening and speaking skills. In addition, they often bring different teaching methods and cultural perspectives, which can make the learning process more interesting and engaging.Another benefit is that it promotes cultural exchange. Foreign teachers can introduce their own cultures and customs to students, which can broaden their horizons and enhance their understanding of the world. At the same time, students can also share their own cultures with the teachers, creating a mutual learning and understanding atmosphere.In addition, the presence of foreign teachers can also improve the quality of English education in Beijing. They can bring new teaching materials and teaching methods, and provide training and guidance to local teachers. This can help improve the overall level of English teaching in the city.However, there are also some challenges associated with the presence of foreign teachers. One of the main challenges is the language barrier. Some foreign teachers may not be fluent in Chinese, which can make it difficult for them to communicate with students and local teachers. In addition, there may be cultural differences that can lead to misunderstandings and conflicts.To address these challenges, it is important for schools and educational institutions to provide support and training to foreign teachers. This can include language training, cultural orientation, and teaching methodology courses. In addition, it is important for local teachers and students to be open-minded and willing to learn from the foreign teachers.The presence of foreigners teaching English in Beijing has brought many benefits to the city and its people. It provides students with a better learning environment, promotes cultural exchange, and improves the quality of English education. However, there are also some challenges that need to be addressed. With the right support and training, these challenges can be overcome, and the benefits of having foreign teachers can be fully realized.。

南京大学海外教育学院汉语学习项目介绍2006-2007Chinese Language ProgramsThe Institute of International Students Nanjing University1.学校及学院简介Brief Introduction南京大学Nanjing University在中国大学中排名前五名的大学之一百年名校浓厚的学术氛围,优良的教学质量宽广的研究领域、齐全的专业设置。

学校现有17个学院、52个系、76各本科专业、207个硕士专业、139个博士专业、18个博士流动站所有的专业均招收留学生Is one of the top 5 universities in ChinaIs a century-old institution with outstanding facilities for teaching and researchBoasts a wide variety of research areas and fields of study. The university currently comprises 17 schools, with a total of 52 departments, 76 undergraduate programs, 207 master’s programs, 139 PhD programs and 18 post-doctoral stations.Welcomes international students to apply to any field of study南京大学海外教育学院Institute for International Students, Nanjing University从1955年开始接受外国留学生,迄今已接受了70多个国家15000多名外国留学生。

目前在校留学生1200余名提供从零起点到本科和研究生的各个层次的汉语教学,以满足各种层次学生的不同需要丰富的课程类型,优秀的教育师资,良好的学习条件。

阅读理解词义猜测篇解题技巧近几年来高考英语阅读理解非常注重对词义的推断题,代词指代判断题和生词词义判断题,其解题思路如下:一、由人称演变过程推断代词意义代词意义判断题要求考生借助诧境逻辑推断人称代词和指示代词的意义。

人称代词意义判断题主要考查考生对it,指动物、无生命事物、特定事件、人,,they,指复数人、动物、物品、事件,属主格,,them(指复数人、动物、物品、事件,属宾格),he, she等代词指代意义的推断。

指示代词意义判断题主要要求考生对this,these, that, those等代词指代意义进行准确判断,考查考生对特定人、物和事件的再认能力。

历年高考实践表明,代词意义判断题容易出现在人称转换较多和动作变换频繁的语境当中。

解题时考生应认真阅读特定代词所在句和前后邻句的内容,搞清人称转换和动作变换的过程,弄清其来龙去脉和前因后果,这样就能准确推断其所替代的对象。

常见的标志词有: mean, underlined, refer to常见的命题形式有:The underlined word in the second paragraph means “________”.Which of the following words is closest in meaning to the underlined word in the last paragraph?The underlined word “hunch” in Paragraph 2 can best be replaced by “________”.What does the phrase “knock off” in Paragraph 1 mean?The underlined sent ence in the last paragraph means “________”.The word “it” in the last sentence refers to “________”.例1:原文:We achieve knowledge passively by being told by someone else. Most of thelearning that takes place in the classroom and the kind that happens when we watch TV or read newspapers or magazines is passive. Conditioned as we are to passive learning, it’s not surprising that we depend on it in our everyday communication with friends and co-workers. (天津卷D卷)试题:The underlined word “it” in paragraph 2 r efers to ______(49题)A active learningB knowledgeC communicationD passive learning例2:原文:Photographs are everywhere. They decorate the walls of homes and are used in stores for sales of different goods. The news is filled with pictures of fires, floods, and special events. Photos record the beauties of nature. They can also bring things close that are far away. Through photos, people can see wild animals, cities in foreign lands, and even the stars in outer space. Photo also tell stories. (陕西卷B篇)试题:The underlined word “they” in the first paragraph refers to_____(45题)A beautiesB photosC goodsD events例3:原文:Tanni’s enduring success has been part motivation, part preparation. “The training I do that enables me to be a good sprinter(短跑运动员)enables me to be a good at a marathon too. I train 50 weeks of the year and that keeps me prepared for whatever distance I went to race------I am still competing at a very high level, but as I get older things get harder and I went to re tire before I fall apart.”(福建卷A篇)试题:The underlined word “that” in the 5th paragraph refers to_______(58题)A.fifty weeks’ trainingB.being a good sprinterC.training almost every dayD.part motivation and part preparation例4:原文:The next day my dad pulled out his childhood pictures and told me quite a few stories about his own childhood . Although our times together became easier over theyears, I never felt closer to him at that moment. After so many years, I’m at last seeing another side of my fath er. And in so doing, I’m delighted with my new friend. My dad, in his new home in Arizona, is back to me from where he was.(全国卷I ,篇)试题: The underlined words “my new friend” in the last paragraph refer to________(59题)A the author’s sonB the author’s fatherC the friend of the author’s fatherD the café owner例5:原文:Some politicians often use this trick. Let’s say that during Governor Smith’s last term, her state lost one million jobs and gained three million jobs. Then she seeks anot her term. One of her opponents says,“During Governor Smith’s term, the state lost one million jobs!”that’s true. However, and honest statement would have been, “During Governor Smith’s term, the state had a net gain of two million jobs”------(全国卷:篇)试题:Wh at do the underlined words “net gain” in paragraph 5 mean?(51题)A.final increaseB.big advantagerge shareD.total saving例6:原文:A Brown University sleep researcher has some advice for people who run high schools: Don’t start classes s o early in the morning. It may not be that the students who nod off at their desks are lazy. And it may not be that their parents have failed to enforce bedtime. Instead, it may be that biologically these sleepyhead students aren’t used to the early hour.------(08浙江卷C篇)试题:The underlined phrase “nod off”(paragraph1) most probably means“______”(49)题A.turn aroundB.agree with othersC.fall asleepD.refuse to work例7: 原文:be skeptical; the topmost branches are usually too skinny to hold weight, and we could never climb high enough to see anything except other trees.------(天津卷E篇) 试题:The underlined word“skeptical”in Paragraph 3 is closest in meaning to _______ (54题)A.clamB.doubtfulC.seriousD.optimistic例8:原文:Climbing attracts people because it’s good exercise for almosteveryone. You use your whole body a complete workout. When you climb,both your mind and your body can become stronger. (安徽卷:篇)试题:The word “workout” underlined in the last paragraph most prob ably means ________(66题)A.settlementB.exerciseC.excitementD.tiredness例9:原文: Parents who found older children bullying younger brothers and sisters might do well to replace shouting and punishment by rewarding and giving more attention to the injured ones. It’s certainly much easier and more effective.(湖北卷B篇)试题:According to the passage, the underlined word “bullying” is closest in meaning to “_________”(67题)A.helpingB.punishingC.hurtingD.protecting词义猜测题强化训练◆Car rentals (出租) are becoming more and more popular as an inexpensive way of taking to the roads.1. The underlined word “inexpensive” in the sentence is closest in meaning to _____.A. modernB. valuableC. convenientD. cheap◆Mr. Smith loves to talk, and his wife is similarly loquacious.2. The underlined word “loquacious” in the sentence probably means _____.A. quietB. calmC. activeD. talkative◆The old woman has a strange habit to keep over 100 cats in her house. Her neighbors all called her an eccentric lady.3. An eccentric lady is likely _____.A. to get along with easilyB. to be different from most peopleC. to be humor and lovelyD. to be serious and beloved◆Most women in Ghana — the educated and illiterate, the urban and rural, the young and old — work to earn an income in addition to maintaining their roles as housewives and mothers.4. The underlined word “illiterate” in the passage means _____.A. repeatedB. richC. uneducatedD. sick◆Dr. Barnard was a member of an agricultural mission to India, a group of experts on better farming methods.5. The underlined word “mission” in the sentence means _____.A. a group of workers working abroadB. a group of students studying abroadC. a group of tourists travelling in foreign countriesD. a group sent abroad to offer help to a foreign country◆Before the main business of a conference begins, the chairman usually makes a short preliminary speech, or makes a few preliminary remarks. In other words, he says a few things by way of introduction.6. What do the underlined words “preliminary speech” mean?A. A speech to give a brief introduction.B. A speech to make the atmosphere active.C. A speech to attract the attention of the listeners.D. A speech to make the listeners laugh.◆Music, for instance, was once as groups’ experience. ... For many people now, however, music is an individual experience.7. The underlined word “individual” probably means _____.A. specialB. personalC. seriousD. alone1-7 DDBCDAB。

株洲六O一中英文小学简介株洲六0一中英文小学,座落在湖南省株洲市荷塘区样板路——钻石路东侧,背倚中国最大的硬质合金企业——株洲硬质合金集团有限公司。

学校始建于一九五七年,前身是株洲硬质合金厂的厂办小学。

随着厂名的更换,先后定名为“六0一厂民办小学”、“长江冶炼厂子弟小学”、“株洲硬质合金厂子弟小学”。

二00二年四月十七日,学校更名为“株洲六0一中英文小学”,正式确立了发展英语特色的办学思路。

二00五年,株洲硬质合金集团公司进行改制,实行主辅分离,九月一日学校由原来的企业办学正式移交至政府管理,成为株洲市荷塘区区属小学。

目前学校拥有3450平方米的草坪足球场。

现有教学楼4幢,学生教室60间。

仪器室、医务室、图书室达省一级标准,图书室藏书4万余册。

学校配套教学设施齐全。

拥有带彩显的语音室2个,科学实验室2个,阅览室2个,钢琴教室4个,计算机网络教室2个,图书室,多媒体教室,体育器材室,综合实践室,电子备课室,广播室,舞蹈练功厅,美术室,塑胶篮球场等。

近几年,学校大力改善办学条件,加速了学校现代化建设。

建成了一个设施齐备,卫生达标的学校食堂及教师、学生餐厅;重新健全了学校的网络,34间教室全部成为多媒体教室,为教职工的工作和学习提供了有利的条件。

学校现有教学仪器设施资产约112万元,现有固定资产736万元。

学校加强硬件设施建设的同时,着力于校园文化建设,建立了校园网站、成立了电视广播站,创办校报,建立了新的文化识别系统,确立了校徽、校旗,建设了文化墙,努力打造“六0一”品牌。

我校现有34个教学班,学生1500多人,教职工100多人,其中专任教师90多人,本科学历的有61人,大专学历的有34人。

教师中,获得高级职称的有3人,获得中级职称的有50人。

2006年以来,学校逐步形成了较为完善的办学理论体系,这就是以“创名校、树名师、育名生”为奋斗目标,倡导“唯标是夺,追求卓越”的校园精神,以“挖掘并发展学生的潜能”为使命,全方位打造“爱生、严谨、育人、创新”的教风和“文明、有礼、勤奋、多思”的学风,形成了“团结守纪、勤奋向上”的校园氛围。

training 造句training 造句如下:1、He was weight training like mad.他在疯了似地进行举重训练。

2、He does a lot of weight training.他进行大量的举重训练。

3、He was training us to be soldiers.他正把我们训练成士兵。

4、These teachers need special training.这些教师需要专门的培训。

5、The training was of no lasting value.这种训练不会有长久的效果。

6、Training is an investment not a cost.培训是一种投资而不是一种花费。

7、Training was given a very low priority. 培训被摆在了非常次要的地位。

8、I used to do weight training years ago. 我多年前曾进行过举重训练。

9、After training she was posted to Biloxi. 培训之后,她被派到了比洛克西。

10、A lot of companies do in-house training. 许多公司都进行内部人员培训。

11、Training makes workers highly productive.培训使工人们生产力很高。

12、My training was geared toward winning gold.我的训练是为赢得金牌去规划的。

13、He hates to be interrupted during training.他讨厌训练中被打断。

14、Training in interpersonal skills is essential. 各种人际交往技巧的训练是非常必要的。

15、The company produces its own training material. 公司自行编写培训教材。

英语作文-高等教育行业中的教师队伍建设与教师培养In the higher education industry, the construction of the teacher team and the training of teachers play a crucial role in shaping the quality of education. The development of a strong and competent teacher workforce is essential for providing students with high-quality education and preparing them for the challenges of the future.First and foremost, the recruitment of talented and dedicated individuals to join the teaching profession is a key aspect of building a strong teacher team. Universities and colleges should have rigorous selection processes in place to ensure that only the most qualified candidates are hired. This includes assessing candidates' academic qualifications, teaching experience, and passion for education. By recruiting the best teachers, institutions can create a positive learning environment and inspire students to reach their full potential.In addition to recruiting top talent, it is important for institutions to provide ongoing professional development opportunities for teachers. Continuous training and support help teachers stay updated on the latest teaching methods and technologies, allowing them to deliver engaging and effective lessons. Professional development programs can also help teachers improve their classroom management skills, communication abilities, and overall teaching effectiveness. By investing in the growth and development of teachers, institutions can ensure that their teacher team remains dynamic and innovative.Furthermore, mentorship programs can be implemented to support new teachers as they navigate the challenges of the profession. Experienced teachers can provide guidance, feedback, and support to new educators, helping them build confidence and develop their teaching skills. Mentorship programs not only benefit new teachers but also contribute to the overall strength and cohesion of the teacher team. By fostering a culture of collaboration and support, institutions can create a positive and nurturing environment for teachers to thrive.Moreover, institutions should prioritize the well-being and job satisfaction of teachers to retain top talent and foster a positive work environment. Providing competitive salaries, benefits, and opportunities for career advancement can help attract and retain skilled educators. Additionally, creating a supportive and inclusive workplace culture where teachers feel valued and respected can boost morale and motivation. By prioritizing the well-being of teachers, institutions can cultivate a dedicated and motivated teacher team that is committed to excellence in education.In conclusion, the construction of a strong teacher team and the continuous training and development of teachers are essential for the success of the higher education industry. By recruiting talented individuals, providing professional development opportunities, implementing mentorship programs, and prioritizing teacher well-being, institutions can build a dynamic and effective teacher workforce that is capable of delivering high-quality education to students. Investing in the growth and development of teachers is not only beneficial for individual educators but also crucial for the overall success and reputation of institutions in the competitive higher education landscape.。