Is Public Listing a Way Out for State-Owned Enterprises

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:113.83 KB

- 文档页数:35

江西省赣县三中2025届高三第二次诊断性检测英语试卷注意事项:1.答卷前,考生务必将自己的姓名、准考证号填写在答题卡上。

2.回答选择题时,选出每小题答案后,用铅笔把答题卡上对应题目的答案标号涂黑,如需改动,用橡皮擦干净后,再选涂其它答案标号。

回答非选择题时,将答案写在答题卡上,写在本试卷上无效。

3.考试结束后,将本试卷和答题卡一并交回。

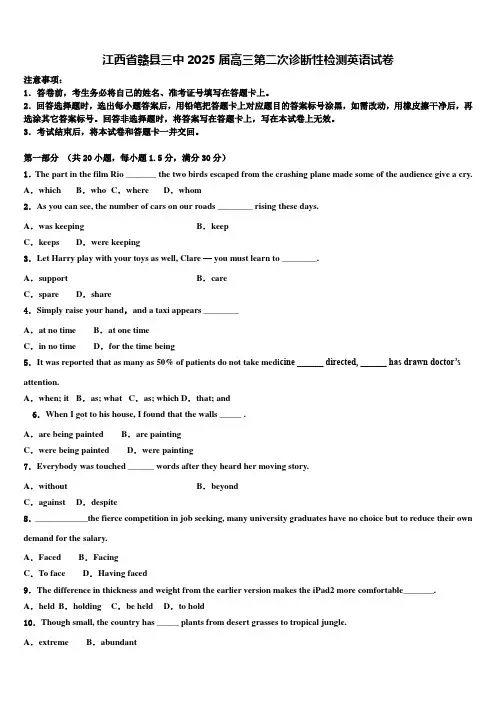

第一部分(共20小题,每小题1.5分,满分30分)1.The part in the film Rio _______ the two birds escaped from the crashing plane made some of the audience give a cry. A.which B.who C.where D.whom2.As you can see, the number of cars on our roads ________ rising these days.A.was keeping B.keepC.keeps D.were keeping3.Let Harry play with your toys as well, Clare — you must learn to ________.A.support B.careC.spare D.share4.Simply raise your hand,and a taxi appears ________A.at no time B.at one timeC.in no time D.for the time being5.It was reported that as many as 50% of patients do not take medi cine ______ directed, ______ has drawn doctor’s attention.A.when; it B.as; what C.as; which D.that; and6.When I got to his house, I found that the walls _____ .A.are being painted B.are paintingC.were being painted D.were painting7.Everybody was touched ______ words after they heard her moving story.A.without B.beyondC.against D.despite8.____________the fierce competition in job seeking, many university graduates have no choice but to reduce their own demand for the salary.A.Faced B.FacingC.To face D.Having faced9.The difference in thickness and weight from the earlier version makes the iPad2 more comfortable_______. A.held B.holding C.be held D.to hold10.Though small, the country has _____ plants from desert grasses to tropical jungle.A.extreme B.abundantC.artificial D.poisonous11.A good suitcase is essential for someone who is ______ as much as Jackie is.A.on the rise B.on the lineC.on the spot D.on the run12.Decades ago, scientists believed that how the brain develops when you are a kid ______ determines your brain structure for the rest of your life.A.sooner or later B.more or less C.to and from D.up and down13.The room ______ 10 metres across is large enough for a single man to live in.A.measuring B.measures C.to be measured D.measured14.The engineer is thought to be capable and modest, so his promotion to manager is a popular _____. A.achievement B.appointment C.commitment D.employment15.The same boiling water softens the potato and hardens the egg. It’s about ________you’re made of, not the circumstances.A.that B.whatC.how D.who16.I’m _______Chinese and I do feel ______Chinese language is ____most beautiful language .A./, the, a B.a, /, the C.a, the, / D.a, /, a17.---Mum, can you tell me why some parents send their children to study abroad at a very young age?---__________, darling. I have never thought about it.A.Y ou have got me there B.Take your timeC.Y ou bet D.Don’t be silly18.We the sunshine in Sanya now if it were not for the delay of our flight.A.were enjoying B.would have enjoyedC.would be enjoying D.will enjoy19.Jane went to her teacher just now. She ________ about the solution to the problem.A.wondered B.was wondering C.had wondered D.would wonder20.I’m not quite sur e how to get there, ---------- I’d better _____ a map.A.watch B.look up C.consult D.read第二部分阅读理解(满分40分)阅读下列短文,从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中,选出最佳选项。

2016年全国硕士研究生入学统一考试英语二真题考生注意事项:1 考生必须严格遵守各项考场规则。

2 答题前,考生应按准考证上的有关内容填写答题卡上的“考生姓名”、“报考单位”、“考生编号”等信息。

3 答案必须按要求填涂或书写在指定的答题卡上。

(1)英语知识运用,阅读理解 A节、B节的答案填涂在答题卡 1上。

填涂部分应该按照答题卡上的要求用 2B铅笔完成。

如需改动,必须用橡皮擦干净。

(2)英译汉和写作部分必须用蓝黑色字迹钢笔、圆珠笔或签字笔在答题卡 2上做答。

字迹要清楚。

4.考试结束,将试题,答题卡1和答题卡2一并装入试题袋中交回。

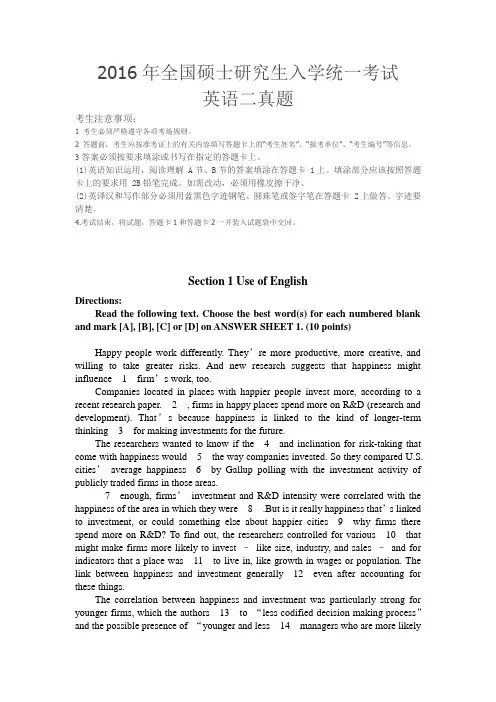

Section 1 Use of EnglishDirections:Read the following text. Choose the best word(s) for each numbered blank and mark [A], [B], [C] or [D] on ANSWER SHEET 1. (10 points)Happy people work differently. They’re more productive, more creative, and willing to take greater risks. And new research suggests that happiness might influence__1__firm’s work, too.Companies located in places with happier people invest more, according to a recent research paper.__2__, firms in happy places spend more on R&D (research and development). That’s because happiness is linked to the kind of longer-term thinking__3__for making investments for the future.The researchers wanted to know if the__4__and inclination for risk-taking that come with happiness would__5__the way companies invested. So they compared U.S. cities’average happiness__6__by Gallup polling with the investment activity of publicly traded firms in those areas.__7__enough, firms’investment and R&D intensity were correlated with the happiness of the area in which they were__8__.But is it really happiness that’s linked to investment, or could something else about happier cities__9__why firms there spend more on R&D? To find out, the researchers controlled for various__10__that might make firms more likely to invest –like size, industry, and sales –and for indicators that a place was__11__to live in, like growth in wages or population. The link between happiness and investment generally__12__even after accounting for these things.The correlation between happiness and investment was particularly strong for younger firms, which the authors__13__to “less codified decision making process”and the possible presence of “younger and less__14__managers who are more likelyto be influenced by sentiment.”The relationship was__15__stronger in places where happiness was spread more__16__.Firms seem to invest more in places where most people are relatively happy, rather than in places with happiness inequality.__17__ this doesn’t prove that happiness causes firms to invest more or to take a longer-term view, the authors believe it at least__18__at that possibility. It’s not hard to imagine that local culture and sentiment would help__19__how executives think about the future. “It surely seems plausible that happy people would be more forward-thinking and creative and__20__R&D more than the average,”said one researcher.1. [A] why [B] where [C] how [D] when2. [A] In return [B] In particular [C] In contrast [D] In conclusion3. [A] sufficient [B] famous [C] perfect [D] necessary4. [A] individualism [B] modernism [C] optimism [D] realism5. [A] echo [B] miss [C] spoil [D] change6. [A] imagined [B] measured [C] invented [D] assumed7. [A] Sure [B] Odd [C] Unfortunate [D] Often8. [A] advertised [B] divided [C] overtaxed [D] headquartered9. [A] explain [B] overstate [C] summarize [D] emphasize10. [A] stages [B] factors [C] levels [D] methods11. [A] desirable [B] sociable [C] reputable [D] reliable12. [A] resumed [B] held [C]emerged [D] broke13. [A] attribute [B] assign [C] transfer [D]compare14. [A] serious [B] civilized [C] ambitious [D]experienced15. [A] thus [B] instead [C] also [D] never16. [A] rapidly [B] regularly [C] directly [D] equally17. [A] After [B] Until [C] While [D] Since18. [A] arrives [B] jumps [C] hints [D] strikes19. [A] shape [B] rediscover [C] simplify [D] share20. [A] pray for [B] lean towards [C] give away [D] send outSection ⅡReading ComprehensionPart ADirections:Read the following four texts. Answer the questions after each text by choosing A, B, C or D. Mark your answers on ANSWER SHEET 1. (40 points)Text 1It’s true that high-school coding classes aren’t essential for learning computer science in college. Students without experience can catch up after a few introductory courses, said Tom Cortina, the assistant dean at Carnegie Mellon’s School of Computer Science.However, Cortina said, early exposure is beneficial. When younger kids learn computer science, they learn that it’s not just a confusing, endless string of letters and numbers —but a tool to build apps, or create artwork, or test hypotheses. It’s not as hard for them to transform their thought processes as it is for older students. Breaking down problems into bite-sized chunks and using code to solve them becomes normal. Giving more children this training could increase the number of people interested in the field and help fill the jobs gap, Cortina said.Students also benefit from learning something about coding before they get to college, where introductory computer-science classes are packed to the brim, which can drive the less-experienced or-determined students away.The Flatiron School, where people pay to learn programming, started as one of the many coding bootcamps that’s become popular for adults looking for a career change. The high-schoolers get the same curriculum, but “we try to gear lessons toward things they’re interested in,”said Victoria Friedman, an instructor. For instance, one of the apps the students are developing suggests movies based on your mood.The students in the Flatiron class probably won’t drop out of high school and build the next Facebook. Programming languages have a quick turnover, so the “Ruby on Rails”language they learned may not even be relevant by the time they enter the job market. But the skills they learn —how to think logically through a problem andorganize the results —apply to any coding language, said Deborah Seehorn, an education consultant for the state of North Carolina.Indeed, the Flatiron students might not go into IT at all. But creating a future army of coders is not the sole purpose of the classes. These kids are going to be surrounded by computers —in their pockets, in their offices, in their homes —for the rest of their lives. The younger they learn how computers think, how to coax the machine into producing what they want —the earlier they learn that they have the power to do that —the better.21. Cortina holds that early exposure to computer science makes it easier to____.A. complete future job trainingB. remodel the way of thinkingC. formulate logical hypothesesD. perfect artwork production22. In delivering lessons for high-schoolers, Flatiron has considered their____.A. experienceB. academic backgroundsC. career prospectsD. interest23. Deborah Seehorn believes that the skills learned at Flatiron will____.A. help students learn other computer languagesB. have to be upgraded when new technologies comeC. need improving when students look for jobsD. enable students to make big quick money24. According to the last paragraph, Flatiron students are expected to____.A. compete with a future army of programmersB. stay longer in the information technology industryC. become better prepared for the digitalized worldD. bring forth innovative computer technologies25. The word “coax”(Line4, Para.6) is closest in meaning to____.A. challengeB. persuadeC. frightenD. misguideText 2Biologists estimate that as many as 2 million lesser prairie chickens---a kind of bird living on stretching grasslands—once lent red to the often gray landscape of the midwestern and southwestern United States. But just some 22,000 birds remain today, occupying about 16% of the species’historic range.The crash was a major reason the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)decided to formally list the bird as threatened. “The lesser prairie chicken is in a desperate situation,”said USFWS Director Daniel Ashe. Some environmentalists, however, were disappointed. They had pushed the agency to designate the bird as “endangered,” a status that gives federal officials greater regulatory power to crack down on threats. But Ashe and others argued that the“threatened”tag gave the federal government flexibility to try out new, potentially less confrontational conservations approaches. In particular, they called for forging closer collaborations with western state governments, which are often uneasy with federal action and with the private landowners who control an estimated 95% of the prairie chicken’s habitat.Under the plan, for example, the agency said it would not prosecute landowner or businesses that unintentionally kill, harm, or disturb the bird, as long as they had signed a range—wide management plan to restore prairie chicken habitat. Negotiated by USFWS and the states, the plan requires individuals and businesses that damage habitat as part of their operations to pay into a fund to replace every acre destroyed with 2 new acres of suitable habitat. The fund will also be used to compensate landowners who set aside habitat, USFWS also set an interim goal of restoring prairie chicken populations to an annual average of 67,000 birds over the next 10 years. And it gives the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA), a coalition of state agencies, the job of monitoring progress. Overall, the idea is to let “states”remain in the driver’s seat for managing the species,”Ashe said.Not everyone buys the win-win rhetoric Some Congress members are trying to block the plan, and at least a dozen industry groups, four states, and threeenvironmental groups are challenging it in federal court Not surprisingly, doesn’t go far enough “The federal government is giving responsibility for managing the bird to the same industries that are pushing it to extinction,”says biologist Jay Lininger.26. The major reason for listing the lesser prairie as threatened is____[A]its drastically decreased population[B]the underestimate of the grassland acreage[C]a desperate appeal from some biologists[D]the insistence of private landowners27.The “threatened”tag disappointed some environmentalists in that it_____[A]was a give-in to governmental pressure[B]would involve fewer agencies in action[C]granted less federal regulatory power[D]went against conservation policies28.It can be learned from Paragraph3 that unintentional harm-doers will not be prosecuted if they_____[A]agree to pay a sum for compensation[B]volunteer to set up an equally big habitat[C]offer to support the WAFWA monitoring job[D]promise to raise funds for USFWS operations29.According to Ashe,the leading role in managing the species in______[A]the federal government[B]the wildlife agencies[C]the landowners[D]the states30.Jay Lininger would most likely support_______[A]industry groups[B]the win-win rhetoric[C]environmental groups[D]the plan under challengeText 3That everyone’s too busy these days is a cliché. But one specific complaint is made especially mournfully:There’s never any time to read.What makes the problem thornier is that the usual time-management techniques don’t seem sufficient. The web’s full of articles offering tips on making time to read: “Give up TV”or “Carry a book with you at all times”But in my experience, using such methods to free up the odd 30 minutes doesn’t work. Sit down to read and the flywheel of work-related thoughts keeps spinning-or else you’re so exhausted that achallenging book’s the last thing you need. The modern mind, Tim Parks, a novelist and critic, writes, “is overwhelmingly inclined toward communication…It is not simply that one is interrupted; it is that one is actually inclined to interruption”. Deep reading requires not just time, but a special kind of time which can’t be obtained merely by becoming more efficient.In fact, “becoming more efficient”is part of the problem. Thinking of time as a resource to be maximised means you approach it instrumentally, judging any given moment as well spent only in so far as it advances progress toward some goal immersive reading, by contrast, depends on being willing to risk inefficiency, goallessness, even time-wasting. Try to slot it as a to-do list item and you’ll manage only goal-focused reading-useful, sometimes, but not the most fulfilling kind. “The future comes at us like empty bottles along an unstoppable and nearly infinite conveyor belt,”writes Gary Eberle in his book Sacred Time, and “we feel a pressure to fill these different-sized bottles (days, hours, minutes)as they pass, for if they get by without being filled, we will have wasted them”. No mind-set could be worse for losing yourself in a book.So what does work? Perhaps surprisingly, scheduling regular times for reading. You’d think this might fuel the efficiency mind-set, but in fact, Eberle notes, such ritualistic behaviour helps us “step outside time’s flow”into “soul time”. You could limit distractions by reading only physical books, or on single-purpose e-readers. “Carry a book with you at all times”can actually work, too-providing you dip in often enough, so that reading becomes the default state from which you temporarily surface to take care of business, before dropping back down. On a really good day, it no longer feels as if you’re “making time to read,”but just reading, and making time for everything else.31. The usual time-management techniques don’t work because[A] what they can offer does not ease the modern mind[B] what challenging books demand is repetitive reading[C] what people often forget is carrying a book with them[D] what deep reading requires cannot be guaranteed32. The “empty bottles”metaphor illustrates that people feel a pressure to[A] update their to-do lists[B] make passing time fulfilling[C] carry their plans through[D] pursue carefree reading33. Eberle would agree that scheduling regular times for reading helps[A] encourage the efficiency mind-set[B] develop online reading habits[C] promote ritualistic reading[D] achieve immersive reading34. “Carry a book with you at all times”can work if[A] reading becomes your primary business of the day[B] all the daily business has been promptly dealt with[C] you are able to drop back to business after reading[D] time can be evenly split for reading and business35. The best title for this text could be[A] How to Enjoy Easy Reading[B] How to Find Time to Read[C] How to Set Reading Goals[D] How to Read ExtensivelyText 4Against a backdrop of drastic changes in economy and population structure, younger Americans are drawing a new 21st-century road map to success, a latest poll has found.Across generational lines, Americans continue to prize many of the same traditional milestones of a successful life, including getting married, having children, owning a home, and retiring in their sixties. But while young and old mostly agree on what constitutes the finish line of a fulfilling life, they offer strikingly different paths for reaching it.Young people who are still getting started in life were more likely than older adults to prioritize personal fulfillment in their work, to believe they will advance their careers most by regularly changing jobs, to favor communities with more public services and a faster pace of life, to agree that couples should be financially secure before getting married or having children, and to maintain that children are best served by two parents working outside the home, the survey found.From career to community and family, these contrasts suggest that in the aftermath of the searing Great Recession, those just starting out in life are defining priorities and expectations that will increasingly spread through virtually all aspects of American life, from consumer preferences to housing patterns to politics.Young and old converge on one key point: Overwhelming majorities of both groups said they believe it is harder for young people today to get started in life than it was for earlier generations. While younger people are somewhat more optimistic than their elders about the prospects for those starting out today, big majorities in both groups believe those “just getting started in life”face a tougher a good-paying job, starting a family, managing debt, and finding affordable housing.Pete Schneider considers the climb tougher today. Schneider, a 27-yaear-old auto technician from the Chicago suburbs says he struggled to find a job after graduating from college. Even now that he is working steadily, he said.”I can’t afford to pay ma monthly mortgage payments on my own, so I have to rent rooms out to people to mark that happen.”Looking back, he is struck that his parents could provide a comfortable life for their children even though neither had completed college when he was young. “I still grew up in an upper middle-class home with parents who didn’thave college degrees,”Schneider said. “I don’t think people are capable of that anymore.”36. One cross-generation mark of a successful life is_____.[A] trying out different lifestyles[B] having a family with children[C] working beyond retirement age[D] setting up a profitable business37. It can be learned from Paragraph 3 that young people tend to ____.[A] favor a slower life pace[B] hold an occupation longer[C] attach importance to pre-marital finance[D] give priority to childcare outside the home38. The priorities and expectations defined by the young will ____.[A] become increasingly clear[B] focus on materialistic issues[C] depend largely on political preferences[D] reach almost all aspects of American life39. Both young and old agree that ____.[A] good-paying jobs are less available[B] the old made more life achievements[C] housing loans today are easy to obtain[D] getting established is harder for the young40. Which of the following is true about Schneider?[A] He found a dream job after graduating from college.[B] His parents believe working steadily is a must for success.[C] His parents’good life has little to do with a college degree.[D] He thinks his job as a technician quite challenging.2015年全国硕士研究生入学统一考试英语二真题考生注意事项:1 考生必须严格遵守各项考场规则。

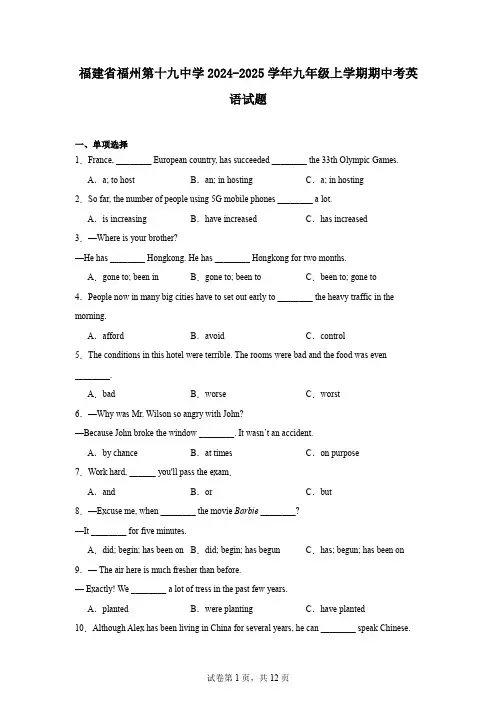

福建省福州第十九中学2024-2025学年九年级上学期期中考英语试题一、单项选择1.France, ________ European country, has succeeded ________ the 33th Olympic Games.A.a; to host B.an; in hosting C.a; in hosting2.So far, the number of people using 5G mobile phones ________ a lot.A.is increasing B.have increased C.has increased 3.—Where is your brother?—He has ________ Hongkong. He has ________ Hongkong for two months.A.gone to; been in B.gone to; been to C.been to; gone to 4.People now in many big cities have to set out early to ________ the heavy traffic in the morning.A.afford B.avoid C.control5.The conditions in this hotel were terrible. The rooms were bad and the food was even________.A.bad B.worse C.worst6.—Why was Mr. Wilson so angry with John?—Because John broke the window ________. It wasn’t an accident.A.by chance B.at times C.on purpose7.Work hard, ______ you'll pass the exam.A.and B.or C.but8.—Excuse me, when ________ the movie Barbie ________?—It ________ for five minutes.A.did; begin; has been on B.did; begin; has begun C.has; begun; has been on 9.— The air here is much fresher than before.— Exactly! We ________ a lot of tress in the past few years.A.planted B.were planting C.have planted 10.Although Alex has been living in China for several years, he can ________ speak Chinese.A.almost B.hardly C.nearly11.—Was the exam easy?—Yes, but I don’t think ________ could pass it.A.everybody B.nobody C.somebody12.—How many people are there in the room?—________. I knocked at the door but ________ answered.A.No one; no one B.None; none C.None; no one13.—Has everyone got ready for the exam ________?—Not ________. Some students still lose themselves in playing computer games every day.A.yet; already B.yet; yet C.already; yet14.—Will your younger brother go for a picnic this Sunday?—If I don’t go, ________.A.so does he B.neither will he C.neither does he 15.—Excuse me, could you tell me ________?—It’s twenty minutes by underground.A.how I can get to your schoolB.how long does it take to get to your schoolC.how far it is from your home to your school二、完形填空从每小题所给的A、B、C三个选项中,选出可以填入空白处的最佳答案。

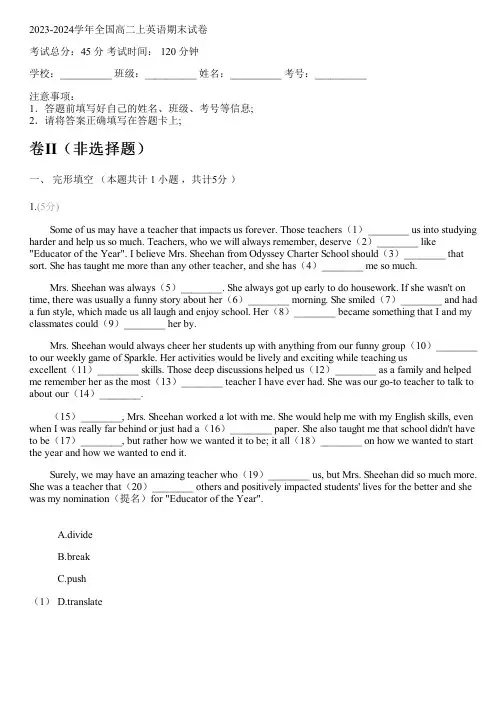

2023-2024学年全国高二上英语期末试卷考试总分:45 分考试时间: 120 分钟学校:__________ 班级:__________ 姓名:__________ 考号:__________注意事项:1.答题前填写好自己的姓名、班级、考号等信息;2.请将答案正确填写在答题卡上;卷II(非选择题)一、完形填空(本题共计 1 小题,共计5分)1.(5分)Some of us may have a teacher that impacts us forever. Those teachers(1)________ us into studying harder and help us so much. Teachers, who we will always remember, deserve(2)________ like "Educator of the Year". I believe Mrs. Sheehan from Odyssey Charter School should(3)________ that sort. She has taught me more than any other teacher, and she has(4)________ me so much.Mrs. Sheehan was always(5)________. She always got up early to do housework. If she wasn't on time, there was usually a funny story about her(6)________ morning. She smiled(7)________ and had a fun style, which made us all laugh and enjoy school. Her(8)________ became something that I and my classmates could(9)________ her by.Mrs. Sheehan would always cheer her students up with anything from our funny group(10)________ to our weekly game of Sparkle. Her activities would be lively and exciting while teaching usexcellent(11)________ skills. Those deep discussions helped us(12)________ as a family and helped me remember her as the most(13)________ teacher I have ever had. She was our go-to teacher to talk to about our(14)________.(15)________, Mrs. Sheehan worked a lot with me. She would help me with my English skills, even when I was really far behind or just had a(16)________ paper. She also taught me that school didn't have to be(17)________, but rather how we wanted it to be; it all(18)________ on how we wanted to start the year and how we wanted to end it.Surely, we may have an amazing teacher who(19)________ us, but Mrs. Sheehan did so much more. She was a teacher that(20)________ others and positively impacted students' lives for the better and she was my nomination(提名)for "Educator of the Year".(1)A.divideB.breakC.pushD.translate(2)A.recognitionB.presenceC.surroundingsD.wisdom(3)A.belong toB.devote toC.refer toD.turn to(4)A.witnessedB.discoveredC.inspiredD.traced(5)A.calmB.curiousC.carefulD.cheerful(6)A.leisureB.colorfulC.busyD.peaceful(7)A.strangelyB.constantlyC.obviouslyD.madly(8)A.smileB.abilityC.spiritD.experience(9)A.supportB.protectC.appreciateD.identify(10)A.adventuresB.discussionsC.arrangementsmitments(11)A.writingB.swimmingC.runningD.driving(12)A.fightB.bondC.marchD.resist(13)A.energeticB.considerateC.beautifulD.excited(14)A.parentsB.relativesC.problemsD.achievements(15)A.OccasionallyB.SuddenlyC.FinallyD.Specifically(16)elessB.horribleC.meaningfulD.spare(17)A.knowledgeableB.attractiveC.distantD.boring(18)A.dependedB.decidedC.insistedD.experimented(19)A.punishedB.consultedC.rememberedD.influenced(20)A.visitedB.acceptedC.touchedD.praised二、阅读理解(本题共计 4 小题,每题 5 分,共计20分)2.Mini Book Excerpts(节选)BiographyWhen Salinger learned that a car park was to be built on the land, the middle-aged writer was shocked and quickly bought the neighboring area to protect it…The townspeople never forgot the rescue and came to help their most famous neighbor.J. D. Salinger: A Life by Kenneth Slawenski(Random House, $27)Mystery(疑案小说)"You're a smart boy. Benny's death was no accident, and you're the only one who saw it happen. Doyou think the murderer should get away with it?" The boy was staring stubbornly at his lap again. A thought suddenly occurred to Annika. "Did you…You recognized the man in the car, didn't you?" The boy hesitated, twisting his fingers. "Maybe," he said quietly.Red Wolf by Liza Marklund(Atria Books, $25.99)Short StoriesShe wants to say to him what she has learned, none of it in class: Some women are born stupid, and some women are too smart for their own good. Some women are born to give, and some women only know how to take. Some women learn who they want to be from their mothers, some who they don't want to be. Some mothers suffer so their daughter won't, some mothers love so their daughters won't.You Are Free by Danzy Senna(Riverhead Books, $15)HumorDo your kids like to have fun? Come to Fun Times! Do you like to watch your kids having fun? Bring them to Fun Times! Fun Times! 's "amusement cycling" is the most fun you can have, legally, in the United States right now. Why spend thousands of dollars flying to Disney World when you can spend less than half of that within a day's drive of most cities?Happy: And Other Rad Thoughts by Larry Dovle(Fcco. $14.99)(1)If the readers want to know about the life of Salinger, they should buy the book published by _______.A.EccoB.Atria BooksC.Riverhead BooksD.Random House(2)The book Happy: And Other Bad Thoughts is intended for ________.A.young childrenB.Disney World workersC.middle school teachersD.parents with young children(3)Which book describes women with characters of their own?A.Happy: And Other Bad Thoughts.B.J. D. Salinger: A Life.C.You Are Free.D.Red Wolf.(4)After finishing the book Red Wolf, the readers would learn that ________.A.the boy helped arrest the murdererB.Benny died of an accidentC.the murderer got away with the crimeD.Annika carried out the crime3.A 17-year-old Bangladeshi boy has won this year's International Children's Peace Prize for his work to fight cyberbullying(网络欺凌)in his country.The prize winner, Sadat Rahman, promised to keep fighting online abuse until it no longer exists. "The fight against cyberbullying is like a war, and in this war I am a fearless fighter," Sadat Rahman said during a ceremony on November 13 in The Hague, the Netherlands. He added, "If everybody keeps supporting me, then together we will win this battle against cyberbullying."Rahman developed a mobile phone application that provides education about online bullying and a way to report cases of it. He said he began his work on the project after hearing the story of a 15-year-old girl who took her own life as a result of cyberbullying. "I will not stop until we receive no more cases through the app," Rahman said at the ceremony.The award comes with a fund of over $118,000, which is invested by the Kids Rights Foundation. The group chooses projects to support causes that are closely linked to the winner's work.Past well-known winners of the prize include Pakistani human rights activist Malala Yousafzai and Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. And the students who organized the March for Our Lives event in 2018 after a deadly mass shooting at their school in the American state of Florida also won the prize.Yousafzai praised Rahman's work during the ceremony. She spoke through video conferencing. "All children have the right to be protected from violence no matter if it is physical or mental, offline or online," she said. "Cyberbullying damages that right."(1)What does Sadat Rahman devote himself to?A.Battling online violence.B.Helping poor children.C.Being a brave fighter.D.Removing school bullying.(2)What caused Sadat Rahman to start his project?A.People's lack of education.B.His own experience of being bullied.C.A girl's death from cyberbullying.D.The wide use of mobile phone apps.(3)What is Paragraph 5 mainly about?A.The March for Our Lives event.B.Human rights activists in the world.C.A horrible mass school shooting.D.Some previous winners of the prize.(4)What can we infer from Yousafzai's words?A.Rahman's efforts have paid off.B.Cyberbullying should be got rid of.C.All children have the right to fight against violence.D.Children are faced with physical and mental bullying.4.Americans have changed, at least when it comes to their apple preferences. The Red Delicious apple is likely to lose its title as the most popular apple this year, which it held for more than half a century. The U.S. Apple Association is projecting, that the Gala apple will usurp(夺取)the Red Delicious for the top spot.The group, which advocates on behalf of 7,500 apple growers and 400 companies in the apple business, predicted that the U. S. would grow 52.4 million Gala apples in 2018, up 5.9 percent from a year earlier. Red Delicious apple production is expected to fall 10.7 percent to 51.7 million.Consumers apparently like the Gala's "taste, texture(口感)and sweetness," the U.S. Apple Association said in a statement. "The rise in production of newer varieties of apples aimed at the fresh consumption domestic market has caused demand for the Red Delicious to decline." said Mark Seetin, the association's director of regulatory and industry affairs.The Granny Smith, Fuji and Honeycrisp apples are expected to rank third, fourth and fifth. The association predicted that within a year or two the Honeycrisp may pass the Granny Smith and Fuji, jumping into third place. The production of the apple rose 21.8 percent to 23.5 million this year. That puts it ahead of the Golden Delicious apple for the first time. The Honeycrisp was created by the University of Minnesota's apple breeding(培育)program only 21 years ago. It typically costs more than its competitors.Until the 1970s, Americans had only a few choices of apples. While the Golden Delicious offered a color contrast and the Granny Smith brought tartness(酸味)to the table, the Red Delicious was the star, heavily promoted by Washington state growers. Then wholesalers began looking for tastier varieties, finding them overseas in Japan, home to the Fuji, and New Zealand, which had the Braeburn and Gala.(1)How does the author prove Americans' preference for the Gala?A.By using statistics.B.By listing examples.C.By explaining causes.D.By presenting research findings.(2)What do we know about the Honeycrisp?A.It is sour in flavor.B.It is light in color.C.It is gaining popularity.D.It is losing its price advantage.(3)Which of the following comes from New Zealand?A.The Fuji.B.The Honeycrisp.C.The Braeburn.D.The Granny Smith.(4)What does the text mainly tell us?A.Why Americans eat apples from different countries.B.How different apples are becoming popular in America.C.How American farmers choose their apple growing types.D.Why the Red Delicious was Americans' favorite for 50 years.causal inferences rather than simply finding patterns. "At some point—you know, if you're intelligent—you realize maybe there's something else out there," he says.【长难句分析】1. After playing thousands of games against itself at a super speed, and learning from winning positions, Alpha Zero independently discovered several famous chess strategies and even invented new ones.翻译:在以超快的速度与自己对弈数千场,并从获胜位置中学习之后,Alpha Zero独立地发现了几种翻译:著名的国际象棋策略,甚至发明了新的策略。

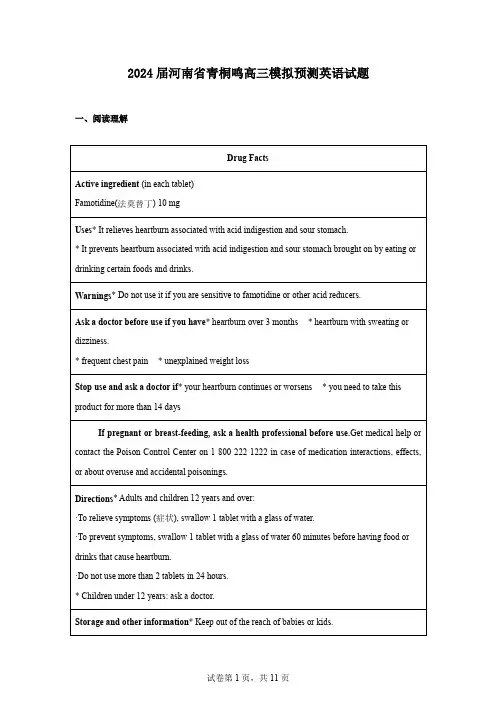

2024届河南省青桐鸣高三模拟预测英语试题一、阅读理解1.Who can take the drug without consulting the doctors?A.Tony, 45, finding a sudden 10 kg weight loss.B.Oliver, 11, feeling heartburn with sour stomach.C.Sally, 20, battling with the heartburn for 4 months.D.Jim, 23, wanting to avoid the heartburn from drinking.2.What can we do with the drug properly?A.Place it in a lower shelf with easy access.B.Store it in a box at the temperature of 30℃.C.Preserve it against exposure to sunshine and rain.D.Take 3 tablets a day to better ease the heartburn.3.What is probably this text?A.A medical journal.B.A label for drug instructions.C.A drug advertisement.D.A physical examination result.Do you recall your beloved school teachers? Did they awaken a passion for a once-unappealing subject or offer valuable guidance?Mr Moriarty was the one. When he became a science teacher, 22-year-old Patrick Moriarty was hoping to make a difference in his students’ lives. After all, the natural world has so many fascinating secrets that he was willing to teach and he would devote long years to preparing his “kids” for adulthood. In 1978, he was teaching kids about the sky events and passed out worksheets, showing the paths of the upcoming eclipses (日食). Sadly, a lot of them would not be visible in New York. All but one on April 8, 2024.“Circle that one,” Mr Moriarty told his students. “We’re going to get together on that one.”The youngsters laughed — the eclipse wouldn’t occur for nearly five decades and everyone would’ve forgotten the promise by then. But they severely underestimated their teacher.Years flew by and Mr Moriarty made the same promise to all of his classes about the plan in the distant future. As the popularity of printed press declined, he created a Facebook group in 2022, detailing the event and trying to find former students who would want to attend it.Mr Moriarty never expected there would be such a massive turnout, but the word was spreading like wildfire among his former classmates. On Monday, the 8th of April, about 100 former students gathered in their teacher’s driveway. As the students started arriving at his house, he had trouble recognizing them. However, he remembered most of their names and some amusing stories that happened during his teaching years.“It was so interesting to see them walking up with thinning or gray hair, and looking at me like, ‘You’re still my teacher,’” he laughed. “This has got to be the longest homework assignment in history.” Lastly, Mr Moriarty suggested marking the 22nd of August, 2044, the day when the next visible total solar eclipse will occur. Once again, everyone laughed, but this time with a little less doubt.4.Why did Mr Moriarty create a Facebook group?A.To popularize astronomical knowledge.B.To seek out former students who wanted to take class.C.To share some funny stories from. his teaching career.D.To remind his former students of the previous assignment.5.Which of the following words best describe Mr Moriarty?A.Passionate and committed.B.Honest and wise.C.Respectable and humble.D.Generous and energetic.6.What can be inferred about Mr Moriarty from paragraph 6?A.He suffered from a poor memory.B.He had little influence on his former students.C.He took great pride in his students’ achievements.D.He was astonished to see so many of his former students.7.What can we learn about the students’ reaction to the reunion of 2044?A.They ignored the special promise.B.They put more trust in their teacher.C.They thought of their teacher being amusing.D.They doubted the possibility of the proposal.The UK is experiencing a boom in book clubs, according to new data from event listing companies. Book club listings on the ticketing site Eventbrite increased by 350% between 2019 and 2023. Between 2022 and 2023 alone, book club listings on the site rose by 41%. Another event listing site, Meetup, reported a 14% increase in the number of RSVPs to book clubs between January 2023 and January 2024, compared with a 4% increase in RSVPs for all UK-based events.Victoria Okafor, who co-runs the book club Between2Books, said the heightened interest in reading may be partly the result of a general “shift in hobbies”, as GenZ (the generation around 00s) turned to other ways to spend their free time. Besides, during the global health crisis period, many people were forced to slow down and pick up or reignite hobbies, and online book clubs provided a platform to connect with others.Social media may be helping with the visibility of book clubs, too, said Okafor. “People may come across your page accidentally, but from there people have the knowledge to attend should they wish. I think this makes a big difference compared to just hearing things from word of mouth.”Many of the book clubs listed on Eventbrite carry specific themes — Sheffield Feminist Book Club, Bring Your Baby Book Club, and Modern Chinese Literature Online Book Club.Okafor’s club, Between2Books, focuses on books by writers traditionally excluded (排除) from the classics. She thought she began seeking out such stories “embarrassingly late”. “Reading authors of color brought back a joy to my reading that came from not only seeing elements of myself and culture reflected in novels but also reading stories that could be funny or empowering as opposed to the accounts of struggle that can often surround stories of people of color,” she said. “The variety of books makes reading and discussion so rich and I think that’s what attenders are drawn to.”8.How is paragraph 1 mainly developed?A.By giving examples.B.By listing figures.C.By analyzing causes.D.By presenting theories.9.What does the underlined word “reignite” in paragraph 2 probably mean?A.Return.B.Reward.C.Regain.D.Reconnect.10.Which is one of the reasons for the boom of book clubs?A.The influence of social media.B.The recommendation of old generations.C.GenZ having a stronger thirst for knowledge.D.Some people shifting the focus of their lives.11.What attracts people to join Okafor’s club according to the last paragraph?A.The diversity of books.B.The reputation of writers.C.The humor of the works.D.The suggestion of the organizer.A Hollywood-quality movie may soon be only a few text prompts away. OpenAI last week revealed its latest, world-shocking technology: a text-to-video app called Sora that can produce photorealistic short videos lasting up to a minute.The company hasn’t released Sora to the public yet, but the artificially generated videos it created for its demonstration were stunning. In one, the detailed prompt involves people walking through Tokyo while cherry blossoms are flying through the wind. The resulting video was a mind-blowing exercise in world-building, showing a couple walking in a detailed streetscape that is unmistakably Tokyo. Perhaps even more awe-inspiring is that Sora does not merely produce videos that fulfill the demands of the prompts. It improvises (即兴创作) in a way that suggests a talent for storytelling.“Good grief,” said Loz Blain in New Atlas. “We’d better try to deal with the speed at which this technology is advancing. The wheel, the steam engine, the airplane, the computer, the Internet... None of them ever sped up like this. If you look closely, you can’t tell that these very short videos aren’t real. But it’s impossible to say whether this technology is nearly as good as it’s going to get. Videos made a year ago, using the AI tool Midjourney, couldn’t even display the correct number of fingers on a hand. But Sora now creates a world as you describe. Get ready for the next wave of ‘AI disruption (颠覆)’ as Sora shakes the entertainment industry.”Yet costs are increasing, too. Estimates of the cost of building out AI systems have varied from hundreds of billions to 7 trillion dollars over the coming years. Where’s the money going to come from? With OpenAI’s current valuation approaching $100 billion, traditional investors are largely priced out. Governments may be one possible solution, but many are likely to have national security concerns about backing this technology.Such concerns are well founded. It’s simply impossible to know how these systems will be misused until they’re out in the wild. While OpenAI has the ability to prevent violent pictures, disinformation is much harder to police. Faked videos could so w confusion and chaos. At the very least, OpenAI should wait until after November to bring Sora to the public.12.Why does the author mention the resulting video in paragraph 2?A.To show Sora has a better gift for writing stories.B.To show Sora has the potential to create great videos.C.To show the video is as good as a Hollywood-quality one.D.To show the video is a stunning result of human wisdom.13.What is Loz Blain’s attitude towards the future of Sora?A.Dismissive.B.Unclear.C.Optimistic.D.Objective. 14.What can be inferred about the technology from the last two paragraphs?A.It is bound to cause confusion and chaos.B.Traditional investment in it is a possible option.C.Governments are doubtful about its development.D.Possible problems related to its use remain to be seen.15.What is the best title for the text?A.Sora: a Rising Star of Video-Making B.Sora: an Admirable Genius at Storytelling C.Sora: a Troublemaker of Public Safety D.Sora: a Potential Promoter of Film IndustryThe Getting Things Done (GTD) method refers to a personal productivity methodology (方法论) that redefines how you approach your life and work. It relies on the idea that you need to simplify your workload. If you frequently feel overwhelmed or you just have too much going on, this method might be great for you. 16 However, it can indeed easily be broken down into five main components:17 Write it all down, either in a planner or a document, and don’t skip anything, even if it seems irrelevant. You will find it somehow helpful in the future.Clarify what you have written down. Look at each task and identify the steps you can take to complete it. Quickly write those down, so you break each task into steps. 18 Then consider whether it can be thrown out or handled later instead.Organize by creating a to-do list, putting action items on your calendar, assigning smaller tasks, filing away reference materials to create a timely, structured approach to getting it done.Reflect frequently and review all your organized materials on a regular basis. 19 Try using an “after-action review” to comprehensively go over what you’ve done and what you need to work on or stick with as you move forward.Engage by tackling your action items knowingly and actively. You have a list of tasks and action items, an organized system with dates and references, and a schedule for checking in with yourself. 20A little stress can push you to be more productive, but too much will have the opposite effect, so using the GTD method can really make you calm and confident.A.Seize whatever is coming into your head.B.Note down the main concerns in your daily life.C.Sometimes you may feel it tough to work out the plan.D.Then you have all in place and work toward goal completion gradually.E.The methodology of GTD may be involved enough to fill a whole book.F.This could mean every Monday, you check it, update or revise something.G.You may find that there are no actionable steps associated with some task.二、完形填空Can you imagine the power of a father? On Sept.17, 2022, a man and his son 21 to begin the first of three legs of the Ironman competition in Cambridge. Jeff Agar, 59, and his son, Johnny Agar, weren’t the 22 participants. Johnny has suffered from a brain disease and finds difficulty in 23 . Consequently, throughout the race, Jeff would 24 as Johnny’s, arms and legs.The race began with a 2.4-mile swim in a river. With one end of a rope 25 around his back and the other to a kayak (皮艇) with Johnny in, Jeff 26 into the water. Swimming while dragging another person is 27 enough. The pair completed the swim in 90 minutes, and here came the next 28 : a 112-mile bicycle ride. Their special bike has an additional seat in the back for Johnny that 29 backward, which made it easier to observe and cheer onother 30 behind.After roughly nine hours, they set their sights on the final leg — a 26.2-mile marathon with Jeff 31 Johnny in the racing chair. 32 , Jeff and Johnny managed to pick up the pace. With only 200 feet to the finish line, Jeff 33 to help Johnny out of his racing chair. After years of tough 34 , Johnny was determined to finish the last part of the race on his own.Eventually, the 35 pair crossed the finish line together. As the crowd. cheered loudly, the tired Jeff just kept a low profile. “He didn’t want his finish line moment,” says Johnny. “He wanted it to be mine.”21.A.broke out B.set out C.picked up D.stood up 22.A.official B.particular C.occasional D.typical 23.A.sleeping B.speaking C.walking D.understanding 24.A.expect B.appear C.treat D.act25.A.tied B.stuck C.decorated D.adapted 26.A.fell B.sailed C.jumped D.drowned 27.A.challenging B.interesting C.fascinating D.inspiring 28.A.measure B.routine C.means D.leg 29.A.leans B.reflects C.faces D.moves 30.A.representatives B.competitors C.applicants D.travelers 31.A.pushing B.approaching C.monitoring D.informing 32.A.Unfortunately B.Generally C.Unbelievably D.Obviously 33.A.stopped B.forced C.pretended D.happened 34.A.researching B.training C.communication D.separation 35.A.heart-broken B.good-natured C.well-known D.strong-willed三、语法填空阅读下面短文,在空白处填入1个适当的单词或括号内单词的正确形式。

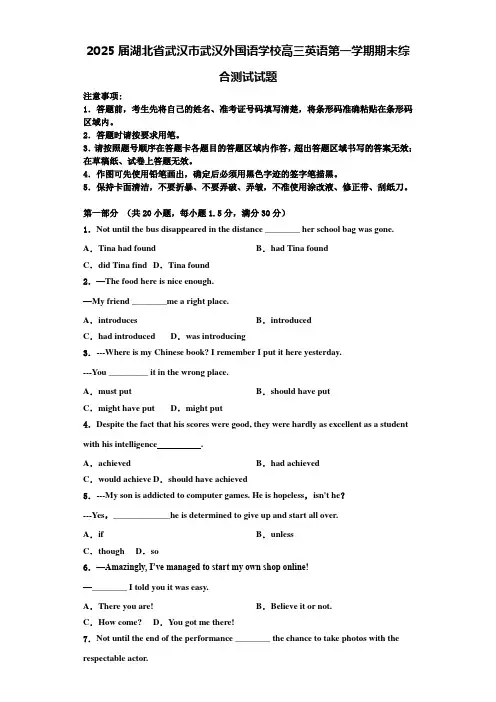

2025届湖北省武汉市武汉外国语学校高三英语第一学期期末综合测试试题注意事项:1.答题前,考生先将自己的姓名、准考证号码填写清楚,将条形码准确粘贴在条形码区域内。

2.答题时请按要求用笔。

3.请按照题号顺序在答题卡各题目的答题区域内作答,超出答题区域书写的答案无效;在草稿纸、试卷上答题无效。

4.作图可先使用铅笔画出,确定后必须用黑色字迹的签字笔描黑。

5.保持卡面清洁,不要折暴、不要弄破、弄皱,不准使用涂改液、修正带、刮纸刀。

第一部分(共20小题,每小题1.5分,满分30分)1.Not until the bus disappeared in the distance ________ her school bag was gone. A.Tina had found B.had Tina foundC.did Tina find D.Tina found2.—The food here is nice enough.—My friend ________me a right place.A.introduces B.introducedC.had introduced D.was introducing3.---Where is my Chinese book? I remember I put it here yesterday.---You _________ it in the wrong place.A.must put B.should have putC.might have put D.might put4.Despite the fact that his scores were good, they were hardly as excellent as a student with his intelligence .A.achieved B.had achievedC.would achieve D.should have achieved5.---My son is addicted to computer games. He is hopeless,isn't he?---Yes,_____________he is determined to give up and start all over.A.if B.unlessC.though D.so6.—Amazingly, I’ve managed to start my own shop online!—________ I told you it was easy.A.There you are! B.Believe it or not.C.How come? D.Y ou got me there!7.Not until the end of the performance ________ the chance to take photos with the respectable actor.A.the audience got B.the audience had gotC.did the audience get D.had the audience got8.—What happened to the young trees we planted last week?—The trees ________ well, but I didn’t water them.A.might grow B.needn’t have grownC.would have grown D.would grow9.______ flag-raising ceremony was held at the Golden Bauhinia Square on July 1 to celebrate ______ 17th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to China.A.A; / B.A; theC.The; the D./; the10.The shocking news made me realize ______ terrible problems we would face.A. that B.how C.what D.why11.A new ________ bus service to Tianjin Airport started to operate two months ago. A.common B.usualC.regular D.ordinary12.— Who recommended Nancy for the post?— It was James ______ admiration for her was obvious.A.who B.that C.whose D.whom13.It was only after a family related conversation ______________ I found out she was actually my distant cousin.A.when B.thatC.which D.who14.--- Hello, Tom. This is Mary speaking.--- What a coincidence! I_________ about you.A.just thought B.was just thinkingC.have just thought D.would just think15.It is not only blind men who make such stupid mistakes. People who can see sometimes act__________.A.just foolishly B.less foolishly C.as foolishly D.so foolishly 16.Among the crises that face humans ________ the lack of natural resources.A.is B.are C.is there D.are there 17.Whether to favor urban development or the preservation of historical sites is especially controversial in China, where there exists rich history, diversified tradition and cultural ________.A.surplus B.deposits C.accounts D.receipts18.It’s second time in five days that he has asked me for higherpay.A.不填;a B.a;the C.the;a D.the;the19.In that remote area, the trees _____ by the volunteers are growing well. A.planted B.planting C.being planted D.to plant20.You will have to stay at home all day ______ you finish all your homework.A.if B.unless C.whether D.because第二部分阅读理解(满分40分)阅读下列短文,从每题所给的A、B、C、D四个选项中,选出最佳选项。

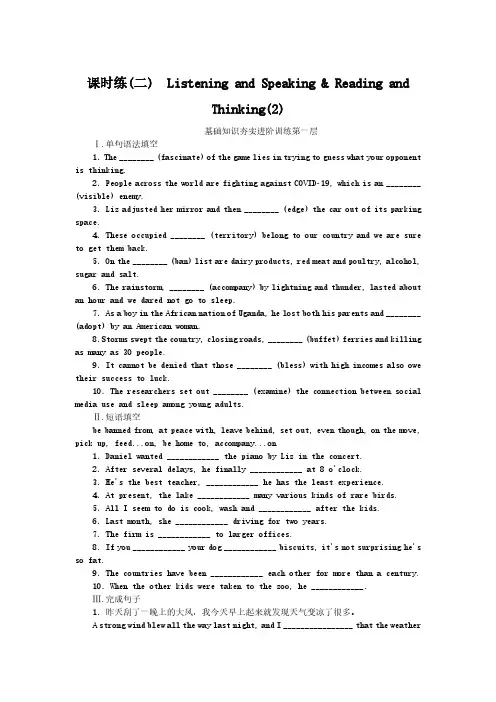

课时练(二) Listening and Speaking & Reading andThinking(2)基础知识夯实进阶训练第一层Ⅰ.单句语法填空1.The ________ (fascinate) of the game lies in trying to guess what your opponent is thinking.2.People across the world are fighting against COVID19, which is an ________ (visible) enemy.3.Liz adjusted her mirror and then ________ (edge) the car out of its parking space.4.These occupied ________ (territory) belong to our country and we are sure to get them back.5.On the ________ (ban) list are dairy products, red meat and poultry, alcohol, sugar and salt.6.The rainstorm, ________ (accompany) by lightning and thunder, lasted about an hour and we dared not go to sleep.7.As a boy in the African nation of Uganda, he lost both his parents and ________ (adopt) by an American woman.8.Storms swept the country, closing roads, ________ (buffet) ferries and killing as many as 30 people.9.It cannot be denied that those ________ (bless) with high incomes also owe their success to luck.10.The researchers set out ________ (examine) the connection between social media use and sleep among young adults.Ⅱ.短语填空be banned from, at peace with, leave behind, set out, even though, on the move, pick up, feed...on, be home to, accompany...on1.Daniel wanted ____________ the piano by Liz in the concert.2.After several delays, he finally ____________ at 8 o'clock.3.He's the best teacher, ____________ he has the least experience.4.At present, the lake ____________ many various kinds of rare birds.5.All I seem to do is cook, wash and ____________ after the kids.6.Last month, she ____________ driving for two years.7.The firm is ____________ to larger offices.8.If you ____________ your dog ____________ biscuits, it's not surprising he's so fat.9.The countries have been ____________ each other for more than a century.10.When the other kids were taken to the zoo, he ____________.Ⅲ.完成句子1.昨天刮了一晚上的大风,我今天早上起来就发现天气变凉了很多。

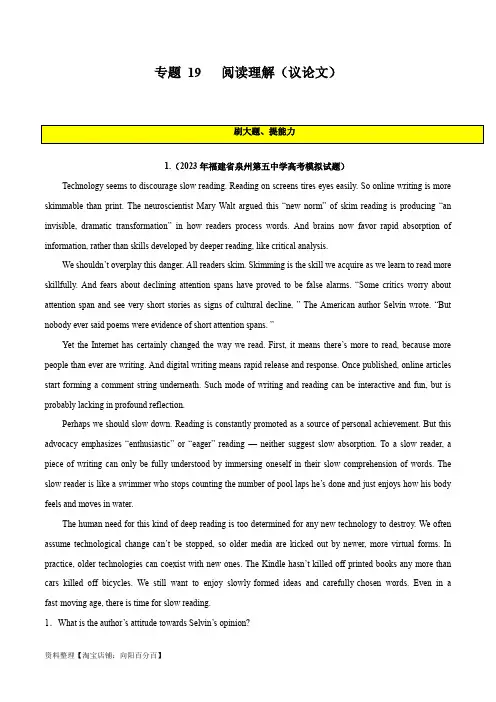

专题19 阅读理解(议论文)1.(2023年福建省泉州第五中学高考模拟试题)Technology seems to discourage slow reading. Reading on screens tires eyes easily. So online writing is more skimmable than print. The neuroscientist Mary Walt argued this “new norm” of skim reading is producing “an invisible, dramatic transformation” in how readers process words. And brains now favor rapid absorption of information, rather than skills developed by deeper reading, like critical analysis.We shouldn’t overplay this danger. All readers skim. Skimming is the skill we acquire as we learn to read more skillfully. And fears about declining attention spans have proved to be false alarms. “Some critics worry about attention span and see very short stories as signs of cultural decline, ” The American author Selvin wrote. “But nobody ever said poems were evidence of short attention spans. ”Yet the Internet has certainly changed the way we read. First, it means there’s more to read, because more people than ever are writing. And digital writing means rapid release and response. Once published, online articles start forming a comment string underneath. Such mode of writing and reading can be interactive and fun, but is probably lacking in profound reflection.Perhaps we should slow down. Reading is constantly promoted as a source of personal achievement. But this advocacy emphasizes “enthusiastic” or “eager” reading — neither suggest slow absorption. To a slow reader, a piece of writing can only be fully understood by immersing oneself in their slow comprehension of words. The slow reader is like a swimmer who stops counting the number of pool laps he’s done and just enjoys how his body feels and moves in water.The human need for this kind of deep reading is too determined for any new technology to destroy. We often assume technological change can’t be stopped, so older media are kicked out by newer, more virtual forms. In practice, older technologies can coexist with new ones. The Kindle hasn’t killed off printed books any more than cars killed off bicycles. We still want to enjoy slowly-formed ideas and carefully-chosen words. Even in a fast-moving age, there is time for slow reading.1.What is the author’s attitude towards Selvin’s opinion?A.Favorable.B.Critical.C.Doubtful.D.Objective.2.Which statement would the author probably agree with?A.Advocacy of passionate reading helps promote slow reading.B.Digital writing and reading tends to ignore careful reflection.C.We should be aware of the impact skimming has on the brain.D.The number of Internet readers declines due to technology.3.Why is “swimmer” mentioned in paragraph 4?A.To demonstrate how to immerse oneself in thought.B.To stress swimming differs from reading.C.To show slow reading is better than fast reading.D.To illustrate what slow reading is like.4.Which would be the best title for the passage?A.Slow Reading is Here to StayB.Technology Prevents Slow ReadingC.Reflections on Deep ReadingD.The Wonder of Deep Reading【答案】1.A 2.B 3.D 4.A【导语】这是一篇议论文。

2016考研英语二真题及答案(完整版)分析令人期待的2016英语初试结束了,凯程教育的电话瞬间变成了热线,同学们兴奋地汇报自己的答题情况,几乎所有内容都在凯程考研集训营系统训练过,英语专业课难度与往年相当,答题的时候非常顺手,英语题型今年是选择题,阅读填空,作文。

相信凯程的学员们对此非常熟悉,预祝亲爱的同学们复试顺利。

英语分笔试、面试,如果没有准备,或者准备不充分,很容易被挂掉。

如果需要复试的帮助,同学们可以联系凯程老师辅导。

下面凯程英语老师把英语的真题全面展示给大家,供大家估分使用,以及2017年考英语的同学使用,本试题凯程首发,转载注明出处。

2016年全国硕士研究生入学统一考试英语(二)真题及答案(完整版)(注:以下选项标红加粗为正确答案)Section I Use of EnglishDirections:Read the following text. Choose the best word(s) for each numbered blank and mark A, B, C or D on the ANSWER SHEET. (10 points)Happy people work differently. They're more productive, more creative, and willing to take greater risks. And new research suggests that happiness might influence how firms work, too.Companies located in place with happier people invest more, according to a recent research paper. In particular , firms in happy places spend more on R&D(research and development).That's because happiness is linked to the kind of longer-term thinking necessary for making investment for the future.The researchers wanted to know if the optimism and inclination for risk-taking that come with happiness would change the way companies invested. So they compared U.S. cities' average happiness measured by Gallup polling with the investment activity of publicly traded firms in those areas.sure enough, firms' investment and R&D intensity were correlated with the happiness of the area in which they were headquartered. But it is really happiness that's linked to investment, or could something else about happier cities explain why firms there spend more on R&D? To find out, the researches controlled for various factors that might make firms more likely to invest like size, industry , and sales-and-and for indicators that a placewas desirable to live in, like growth in wages or population. They link between happiness and investment generally held even after accounting for these things.The correlation between happiness and investment was particularly strong for younger firms, which the authors attribute to "less confined decision making process" and the possible presence of younger and less experienced managers who are more likely to be influenced by sentiment.'' The relationship was also stronger in places where happiness was spread more equally. Firms seem to invest more in places.While this doesn't prove that happiness causes firms to invest more or to take a longer-term view, the authors believe it at least hints at that possibility. It's not hard to imagine that local culture and sentiment would help shape how executives think about the future. It surely seems plausible that happy people would be more forward -thinking and creative and lean towards R&D more than the average," said one researcher.Section II Reading ComprehensionPart ADirections:Read the following four texts. Answer the questions below each text by choosing A, B, C or D. Mark your answers on the ANSWER SHEET. (40 points)Text 1It's true that high-school coding classes aren't essential for learning computer science in college. Students without experience can catch up after a few introductory courses, said Tom Cortina, the assistant dean at Carnegie Mellon's School of Computer Science.However, Cortina said, early exposure is beneficial. When younger kids learn computer science, they learn that it's not just a confusing, endless string of letters and numbers - but a tool to build apps, or create artwork, or test hypotheses. It's not as hard for them to transform their thought processes as it is for older students. Breaking down problems into bite-sized chunks and using code to solve them becomes normal. Giving more children this training could increase the number of people interested in the field and help fill the jobs gap, Cortina said.Students also benefit from learning something about coding before they get to college, where introductory computer-science classes are packed to the brim, which can drive the less-experienced or-determined students away.The Flatiron School, where people pay to learn programming, started as one of the many coding bootcamps that's become popular for adults looking for a career change. The high-schoolers get the same curriculum, but "we try to gear lessons toward things they're interested in," said Victoria Friedman, an instructor. For instance, one of the apps the students are developing suggests movies based on your mood.The students in the Flatiron class probably won't drop out of high school and build the next Facebook. Programming languages have a quick turnover, so the "Ruby on Rails" language they learned may not even be relevant by the time they enter the job market. But the skills they learn - how to think logically through a problem and organize the results - apply to any coding language, said Deborah Seehorn, an education consultant for the state of North Carolina.Indeed, the Flatiron students might not go into IT at all. But creating a future army of coders is not the sole purpose of the classes. These kids are going to be surrounded by computers-in their pockets ,in their offices, in their homes -for the rest of their lives, The younger they learn how computers think, how to coax the machine into producing what they want -the earlier they learn that they have the power to do that -the better.21.Cortina holds that early exposure to computer science makes it easier to _______[A] complete future job training[B] remodel the way of thinking[C] formulate logical hypotheses[D] perfect artwork production22.In delivering lessons for high - schoolers , Flatiron has considered their________[A] experience[B] interest[C] career prospects[D] academic backgrounds23.Deborah Seehorn believes that the skills learned at Flatiron will ________[A] help students learn other computer languages[B] have to be upgraded when new technologies come[C] need improving when students look for jobs[D] enable students to make big quick money24.According to the last paragraph, Flatiron students are expected to ______[A] bring forth innovative computer technologies[B] stay longer in the information technology industry[C] become better prepared for the digitalized world[D] compete with a future army of programmers25.The word "coax"(Line4,Para.6) is closest in meaning to ________[A] persuade[B] frighten[C] misguide[D] challengeText 2Biologists estimate that as many as 2 million lesser prairie chickens---a kind of bird living on stretching grasslands-once lent red to the often grey landscape of the midwestern and southwestern United States. But just some 22,000 birds remain today, occupying about 16% of the species 'historic range.The crash was a major reason the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS)decided to formally list the bird as threatened ."The lesser prairie chicken is in a desperate situation ," said USFWS Director Daniel Ashe. Some environmentalists, however, were disappointed. They had pushed the agency to designate the bird as "endangered," a status that gives federal officials greater regulatory power to crack down on threats .But Ashe and others argued that the" threatened" tag gave the federal government flexibility to try out new, potentially less confrontational conservations approaches. In particular, they called for forging closer collaborations with western state governments, which are often uneasy with federal action. and with the private landowners who control an estimated 95% of the prairie chicken's habitat.Under the plan, for example, the agency said it would not prosecute landowner or businesses that unintentionally kill, harm, or disturb the bird, as long as they had signed a range-wide management plan to restore prairie chicken habitat. Negotiated by USFWS and the states, the plan requires individuals and businesses that damage habitat as part of their operations to pay into a fund to replace every acre destroyed with 2 new acres of suitable habitat .The fund will also be used to compensate landowners who set aside habitat , USFWS also set an interim goal of restoring prairie chicken populations to an annual average of 67,000 birds over the next 10 years .And it gives the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (WAFWA), a coalition of state agencies, the job of monitoring progress. Overall, the idea is to let "states" remain in the driver 's seat for managing the species," Ashe said.Not everyone buys the win-win rhetoric. Some Congress members are trying to block the plan, and at least a dozen industry groups, four states, and three environmental groups are challenging it in federal court. Not surprisingly, doesn't go far enough. "The federal government is giving responsibility for managing the bird to the same industries that are pushing it to extinction, " says biologist Jay Lininger.26.The major reason for listing the lesser prairie as threatened is____.[A]its drastically decreased population[B]the underestimate of the grassland acreage[C]a desperate appeal from some biologists[D]the insistence of private landowners27.The "threatened" tag disappointed some environmentalists in that it_____.[A]was a give-in to governmental pressure[B]would involve fewer agencies in action[C]granted less federal regulatory power[D]went against conservation policies28.It can be learned from Paragraph3 that unintentional harm-doers will not be prosecuted if they_____.[A]agree to pay a sum for compensation[B]volunteer to set up an equally big habitat[C]offer to support the WAFWA monitoring job[D]promise to raise funds for USFWS operations29.According to Ashe, the leading role in managing the species in______.[A]the federal government[B]the wildlife agencies[C]the landowners[D]the states30.Jay Lininger would most likely support_______.[A]industry groups[B]the win-win rhetoric[C]environmental groups[D]the plan under challengeText 3That everyone's too busy these days is a cliché. But one specific complaint is made especially mournfully: There's never any time to read.What makes the problem thornier is that the usual time-management techniques don't seem sufficient. The web's full of articles offering tips on making time to read: "Give up TV" or "Carry a book with you at all times." But in my experience, using such methods to free up the odd 30 minutes doesn't work. Sit down to read and the flywheel of work-related thoughts keeps spinning-or else you're so exhausted that a challenging book's the last thing you need. The modern mind, Tim Parks, a novelist and critic, writes, "is overwhelmingly inclined toward communication…It is not simply that one is interrupted; it is that one is actually inclined to interruption." Deep reading requires not just time, but a special kind of time which can't be obtained merely by becoming more efficient.In fact, "becoming more efficient" is part of the problem. Thinking of time as a resource to be maximised means you approach it instrumentally, judging any given moment as well spent only in so far as it advances progress toward some goal. Immersive reading, by contrast, depends on being willing to risk inefficiency, goallessness, even time-wasting. Try to slot it as a to-do list item and you'll manage only goal-focused reading-useful, sometimes, but not the most fulfilling kind. "The future comes at us likeempty bottles along an unstoppable and nearly infinite conveyor belt," writes Gary Eberle in his book Sacred Time, and "we feel a pressure to fill these different-sized bottles (days, hours, minutes) as they pass, for if they get by without being filled, we will have wasted them." No mind-set could be worse for losing yourself in a book.So what does work? Perhaps surprisingly, scheduling regular times for reading. You'd think this might fuel the efficiency mind-set, but in fact, Eberle notes, such ritualistic behaviour helps us "step outside time's flow" into "soul time." You could limit distractions by reading only physical books, or on single-purpose e-readers. "Carry a book with you at all times" can actually work, too-providing you dip in often enough, so that reading becomes the default state from which you temporarily surface to take care of business, before dropping back down. On a really good day, it no longer feels as if you're "making time to read," but just reading, and making time for everything else.31. The usual time-management techniques don't work because .[A] what they can offer does not ease the modern mind[B] what challenging books demand is repetitive reading[C] what people often forget is carrying a book with them[D] what deep reading requires cannot be guaranteed32. The "empty bottles" metaphor illustrates that people feel a pressure to .[A] update their to-do lists[B] make passing time fulfilling[C] carry their plans through[D] pursue carefree reading33. Eberle would agree that scheduling regular times for reading helps .[A] encourage the efficiency mind-set[B] develop online reading habits[C] promote ritualistic reading[D] achieve immersive reading34. "Carry a book with you at all times" can work if .[A] reading becomes your primary business of the day[B] all the daily business has been promptly dealt with[C] you are able to drop back to business after reading[D] time can be evenly split for reading and business35. The best title for this text could be .[A] How to Enjoy Easy Reading[B] How to Find Time to Read[C] How to Set Reading Goals[D] How to Read ExtensivelyText 4Against a backdrop of drastic changes in economy and population structure, younger Americans are drawing a new 21st-century road map to success, a latest poll has found.Across generational lines, Americans continue to prize many of the same traditional milestones of a successful life, including getting married, having children, owning a home, and retiring in their sixties. But while young and old mostly agree on what constitutes the finish line of a fulfilling life, they offer strikingly different paths for reaching it.Young people who are still getting started in life were more likely than older adults to prioritize personal fulfillment in their work, to believe they will advance their careers most by regularly changing jobs, to favor communities with more public services and a faster pace of life, to agree that couples should be financially secure before getting married or having children, and to maintain that children are best served by two parents working outside the home, the survey found.From career to community and family, these contrasts suggest that in the aftermath of the searing Great Recession, those just starting out in life are defining priorities and expectations that will increasingly spread through virtually all aspects of American life, from consumer preferences to housing patterns to politics.Young and old converge on one key point: Overwhelming majorities of both groups said they believe it is harder for young people today to get started in life than it was for earlier generations. Whlie younger people are somewhat more optimistic than their elders about the prospects for those starting out today, big majorities in both groups believe those "just getting started in life" face a tougher a good-paying job, starting a family, managing debt, and finding affordable housing.Pete Schneider considers the climb tougher today. Schneider, a 27-yaear-old auto technician from the Chicago suburbs says he struggled to find a job after graduating from college. Even now that he is working steadily, he said." I can't afford to pay ma monthly mortgage payments on my own, so I have to rent rooms out to people to mark that happen." Looking back, he is struck that his parents could provide a comfortable life for their children even though neither had completed college when he was young."I still grew up in an upper middle-class home with parents who didn't have college degrees,"Schneider said."I don't think people are capable of that anymore. "36. One cross-generation mark of a successful life is .[A] trying out different lifestyles[B] having a family with children[C] working beyond retirement age[D] setting up a profitable business37. It can be learned from Paragraph 3 that young people tend to .[A] favor a slower life pace[B] hold an occupation longer[C] attach importance to pre-marital finance[D] give priority to childcare outside the home38. The priorities and expectations defined by the young will .[A] become increasingly clear[B] focus on materialistic issues[C] depend largely on political preferences[D] reach almost all aspects of American life39. Both young and old agree that .[A] good-paying jobs are less available[B] the old made more life achievements[C] housing loans today are easy to obtain[D] getting established is harder for the young40. Which of the following is true about Schneider?[A] He found a dream job after graduating from college[B] His parents believe working steadily is a must for success[C] His parents' good life has little to do with a college degree[D] He thinks his job as a technician quite challengingPart BDirections:Read the following text and answer the questions by choosing the most suitable subheading from the list A-G for each numbered paragraphs (41-45). There are two extra subheadings which you do not need to use. Mark your answers on the ANSWER SHEET.(10 points)[A] Be silly[B] Have fun[C] Ask for help[D] Express your emotions.[E] Don't overthink it[F] Be easily pleased[G] Notice thingsAct Your Shoe Size, Not Your Age.(1) As adults, it seems that we're constantly pursuing happiness, often with mixed results. Yet children appear to have it down to an art-and for the most part they don't need self-help books or therapy. Instead, they look after their wellbeing instinctively and usuallymore effectively than we do as grownups. Perhaps it's time to learn a few lessons from them.41_____ [D] Express your emotions(2) What does a child do when he's sad? He cries. When he's angry? He shouts. Scared? Probably a bit of both. As we grow up, we learn to control our emotions so they are manageable and don't dictate our behaviours, which is in many ways a good thing. But too often we take this process too far and end up suppressing emotions, especially negative ones. That's about as effective as brushing dirt under a carpet and can even make us ill. What we feel appropriately and then-again, like children-move on.42______[F] Be easily pleasedA couple of Christmases ago, my youngest stepdaughter, who was 9 years old at the time, got a Superman T-shirt for Christmas. It cost less than a fiver but she was overjoyed, and couldn't bigger house or better car will be the magic silver bullet that will allow us to finally be content, but the reality is these things have little lasting impact on our happiness levels. Instead, being grateful for small things every day is a much better way to improve wellbeing.43_______[A] Be sillyHave you ever noticed how much children laugh? If we adults could indulge in a bit of silliness and giggling, we would reduce the stress hormones in our bodies, increase good hormones like endorphins, improve blood flow to our hearts and ever have a greater chance of fighting off infection. All of which would, of course, have a positive effect on our happiness levels.44______ [B] Have funThe problem with being a grownup is that there's an awful lot of serious stuff to deal with-work, mortgage payments, figuring out what to cook for dinner. But as adults we also have the luxury of being able to control our own diaries and it's important that we schedule in time to enjoy the thing we love. Those things might be social, sporting, creative or completely random (dancing around the living room, anyone?)-it doesn't matter, so long as they're enjoyable, and not likely to have negative side effects, such as drinking too much alcohol or going on a wild spending spree if you're on a tight budget.45______ [E] Don't overthink itHaving said all of the above, it's important to add that we shouldn't try too hard to be happy. Scientists tell us this can back fire and actually have a negative impact on our wellbeing. As the Chinese philosopher Chuang Tzu is reported to have said: "Happiness is the absence of striving for happiness." And in that, once more, we need to look to the example of our children, to whom happiness is not a goal but a natural byproduct of the way they live.Section III TranslationDirections:Translate the following text into Chinese. Write your translation on the ANSWER SHEET. (15 points)The supermarket is designed to lure customers into spending as much time as possible within its doors. The reason for this is simple: The longer you stay in the store, the more stuff you'll see, and the more stuff you see, the more you'll buy. And supermarkets contain a lot of stuff. The average supermarket, according to the Food Marketing Institute, carries some 44,000 different items, and many carry tens of thousands more. The sheer volume of available choice is enough to send shoppers into a state of information overload. According to brain-scan experiments, the demands of so much decision-making quickly become too much for us. After about 40 minutes of shopping, most people stop struggling to be rationally selective, and instead began shopping emotionally-which is the point at which we accumulate the 50 percent of stuff in our cart that we never intended buying.【参考译文】超市旨在吸引顾客在自己店内停留尽量长的时间。