The Dynamics and Semantics of Collaborative Tagging ABSTRACT

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:213.12 KB

- 文档页数:10

全国2019年4月高等教育自学考试英语词汇学试题课程代码:00832I. Each of the statements below is followed by four alternative answers. Choose the one that would best complete the statement and put the letter in the bracket. (30%)1. There are ______ major classes of compounds.A. twoB. forC. threeD. five2. Which of the following statements is NOT true?A. Connotative meaning refers to associations suggested by the conceptual meaning.B. Stylistic meaning accounts for the formality of the word concerned.C. Affective meaning is universal to all men alike.D. Denotative meaning can always be found in the dictionary.3. After the invading Germanic tribes settled down in Britain, their language almost totally blotted out ______.A. Old EnglishB. Middle EnglishC. Anglo-SaxonD. Celtic4. The idiom “Jack of all trades”results from ______.A. additionB. position-shiftingC. dismemberingD. shortening5. ______ are those that cannot occur as separate words without adding other morphemes.A. Free rootsB. Free morphemesC. Bound morphemesD. Meaningful units6. The major factors that promote the growth of modern English are ______.A. the growth of science and technologyB. economic and political changesC. the influence of other cultures and languagesD. all the above7. Since the beginning of this century, ______ has become even more important for the expansion of English vocabulary.A. word-formationB. borrowingC. semantic changeD. both B and C8. Which of the following characteristics of the basic word stock is the most important?A. StabilityB. Collocability.C. Productivity.D. National character.19. The two major factors that cause changes in meaning are ______.A. historical reason and class reasonB. historical reason and psychological reasonC. class reason and psychological reasonD. extra-linguistic factors and linguistic factors10. The fundamental difference between homonyms and polysemants is whether ______.A. they come from the same sourceB. they are correlated with one central meaningC. they are listed under one headword in a dictionaryD. all the above11. Degradation of meaning is the opposite of ______.A. semantic transferB. semantic pejorationC. semantic elevationD. semantic narrowing12. An idiom consists of at least two words. Each has a single meaning and often functions as one word. This is called ______.A. semantic unityB. structural stabilityC. rhetorical functionD. none of the above13. Which of the following suffixes can be used to form both nouns and adjectives? ______A. -ion.B. -ism.C. -ity.D. -ist.14. More often than not, functional words only have ______.A. lexical meaningB. associative meaningC. collocative meaningD. grammatical meaning15. Linguistic context is also known as ______ context.A. socialB. verbalC. lexicalD. physicalII. Complete the following statements with proper words or expressions according to the course book. (10%)16. In the course book, the idioms are classified according to ______ functions.17. Linguistic context can be further divided into ______ context and grammatical context.18. The ______ languages made only a small contribution to the English vocabulary with a few place names like Avon, kent, Themes.19. Morphemes which are identical with root words are considered to be ______.20. According to semanticists, a word is a unit of ______.III. Match the words or expressions in Column A with those in Column B according to 1) stylistic meanings; 2)language groups; 3)degrees of inflections and 4) onomatopoeic motivation. (10%)A B23( )21. apesA. colloquial ( )22. Old EnglishB. a language of full endings ( )23. IrishC. Italic ( )24. tinyD. very formal and official ( )25. FrenchE. yelp ( )26. cattleF. poetic ( )27. domicileG . Celtic ( )28. abodeH. gibber ( )29. foxesI. a language of leveled endings ( )30. Middle English J. lowⅣ. Study the following words and expressions and identify 1) types of affixes; 2) types of meaning and 3) types of motivation. (10%)31. mismanage( ) 32. elephants-trumpet( ) 33. pretty ⎪⎩⎪⎨⎧flower woman girl( ) 34. forehead( ) 35. bossy( ) 36. sun: a heavenly body which gives off light, heat ( ) 37. anti-establishment( ) 38. subsea ( ) 39. a sea of troubles( ) 40. harder( ) Ⅴ. Define the following terms. (10%)41. idiom42. functional words43. degradation44. bilingual dictionary45. conversion Ⅵ. Answer the following questions. Your answers should be clear and short. Write your answers in the space given below. (12%)46. What factors should one take into account when he chooses a dictionary?47. What are the features of compounds? Give examples.48. Cite ONE example to illustrate what grammatical meaning is.Ⅶ. Analyze and comment on the following. Write your answers in the space given below.(18%)49. Read the following extract and try to guess the meaning of the word in italics. Then explain what contextual clues help you work out the meaning.‘Get me an avocado, please,’Janet said, smacking her lips, but her brother, with a glance up at the branches, said that there were none ripe yet.50. Make a tree diagram to arrange the following words in order of hyponymy.apple, cabbage, food, vegetable, mutton, fruit, peach, meat, beef, orange, spinach, pork, celery4。

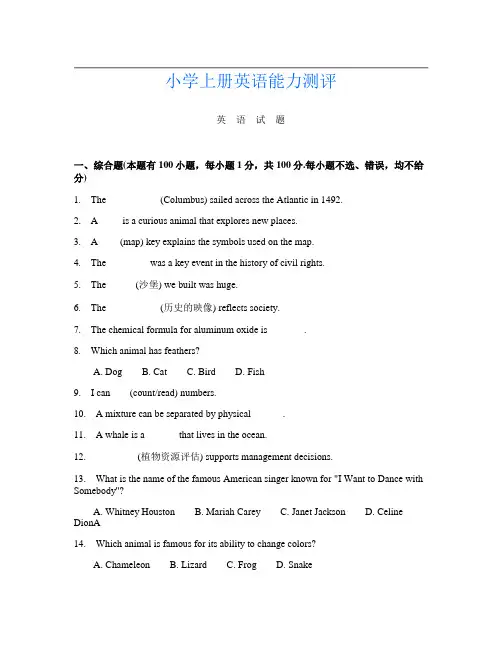

小学上册英语能力测评英语试题一、综合题(本题有100小题,每小题1分,共100分.每小题不选、错误,均不给分)1.The __________ (Columbus) sailed across the Atlantic in 1492.2. A ____ is a curious animal that explores new places.3. A ____(map) key explains the symbols used on the map.4.The ________ was a key event in the history of civil rights.5.The _____ (沙堡) we built was huge.6.The __________ (历史的映像) reflects society.7.The chemical formula for aluminum oxide is _______.8.Which animal has feathers?A. DogB. CatC. BirdD. Fish9.I can ___ (count/read) numbers.10. A mixture can be separated by physical ______.11. A whale is a ______ that lives in the ocean.12.________ (植物资源评估) supports management decisions.13.What is the name of the famous American singer known for "I Want to Dance with Somebody"?A. Whitney HoustonB. Mariah CareyC. Janet JacksonD. Celine DionA14.Which animal is famous for its ability to change colors?A. ChameleonB. LizardC. FrogD. Snake15.He is my _____ (teacher).16.What do we call the large body of fresh water?A. OceanB. RiverC. LakeD. SeaC17.What is the name of the famous American author known for "To Kill a Mockingbird"?A. Mark TwainB. Harper LeeC. Ernest HemingwayD. F. Scott FitzgeraldB18._____ (土壤) quality affects plant growth.19.The _____ (植物细胞) help in growth and development.20.The chemical formula for ethylene is _______.21.The _______ in the garden are blooming beautifully.22.The pelican's bill acts like a net for catching ________________ (鱼).23.Matter can exist in different _____ depending on temperature and pressure.24.The _____ (chicken) lays eggs.25.The ______ (海鸥) flies above the beach.26.Which season is coldest?A. SpringB. SummerC. AutumnD. WinterD27.They are watching a ________.28.The chemical symbol for chlorine is __________.29.The chemical symbol for lithium is ____.30.After the rain, the grass looks very ______ (绿色).31. A _______ forms when a gas cools and turns into a liquid.32.The main gas produced during respiration is __________.33.The ancient Egyptians had a complex social ________ (阶层).34.The park is _______ (很美丽).35.I love to watch ______ while I eat dinner.36.The _______ attracts various pollinators.37.The turtle swims _______ (安静) in the pond.38.Plants take in _____ (二氧化碳) during photosynthesis.39. A nonpolar molecule does not have charged ______.40.My sister is a ______. She loves to play tennis.41. A chemical reaction can lead to the formation of new ________.42.cultural heritage) influences local traditions. The ____43.Hydrogen is the simplest and most abundant _____.44.Mars rovers send back pictures and ______.45.What do you call a baby cat?A. PuppyB. KittenC. CalfD. ChickB46.Which sport is played with a ball and a net?A. SoccerB. BasketballC. TennisD. All of the aboveD47.What do we call a group of stars?A. GalaxyB. UniverseC. ConstellationD. Nebula48.My brother is a ______. He enjoys playing video games.49. A ______ is a type of animal that can swim very fast.50.The _______ (The Space Shuttle) program enabled human spaceflight.51. A healthy garden requires good __________ (照顾).52.What do we call the person who helps in a hospital?A. TeacherB. NurseC. PilotD. Driver53.What do we call the hot season of the year?A. WinterB. SpringC. SummerD. Autumn54.The ________ swims in the water all day.55.What do you call a person who plays an instrument?A. MusicianB. SingerC. DancerD. Actor56.I love to watch _____ (小动物) play in the garden.57.The ________ is very gentle and caring.58.The Earth's atmosphere contains layers such as the ______ and stratosphere.59.What do we call a person who draws pictures?A. WriterB. ArtistC. SculptorD. Photographer60. A _____ (植物知识交流) can foster collaboration among enthusiasts.61.What do we call the study of the Earth's structure and processes?A. GeologyB. GeographyC. CartographyD. Meteorology62.The dog is ______ (barking).63.What is 1 + 1?A. 1B. 2C. 3D. 464.She is a _____ (学生) who loves math and science.65.What do you call the temperature at which water boils?A. 50°CB. 100°CC. 150°CD. 200°CB66.What is the capital of Belize?A. BelmopanB. Belize CityC. San IgnacioD. Orange WalkA67.Fossils are often found in __________ rocks.68.The flowers of a plant may have different shapes and ______. (植物的花朵可能有不同的形状和颜色。

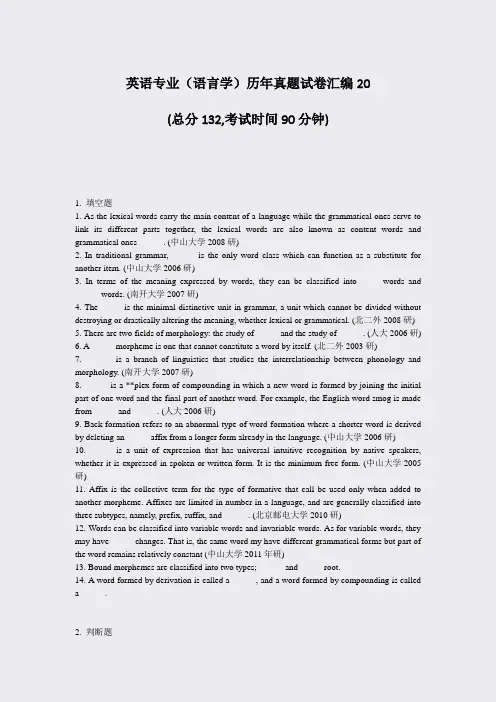

英语专业(语言学)历年真题试卷汇编20(总分132,考试时间90分钟)1. 填空题1. As the lexical words carry the main content of a language while the grammatical ones serve to link its different parts together, the lexical words are also known as content words and grammatical ones______. (中山大学2008研)2. In traditional grammar, ______is the only word class which can function as a substitute for another item. (中山大学2006研)3. In terms of the meaning expressed by words, they can be classified into______words and ______words. (南开大学2007研)4. The______is the minimal distinctive unit in grammar, a unit which cannot be divided without destroying or drastically altering the meaning, whether lexical or grammatical. (北二外2008研)5. There are two fields of morphology: the study of______and the study of______. (人大2006研)6. A______morpheme is one that cannot constitute a word by itself. (北二外2003研)7. ______ is a branch of linguistics that studies the interrelationship between phonology and morphology. (南开大学2007研)8. ______is a **plex form of compounding in which a new word is formed by joining the initial part of one word and the final part of another word. For example, the English word smog is made from______and______. (人大2006研)9. Back-formation refers to an abnormal type of word-formation where a shorter word is derived by deleting an______affix from a longer form already in the language. (中山大学2006研)10. ______is a unit of expression that has universal intuitive recognition by native speakers, whether it is expressed in spoken or written form. It is the minimum free form. (中山大学2005研)11. Affix is the collective term for the type of formative that call be used only when added to another morpheme. Affixes are limited in number in a language, and are generally classified into three subtypes, namely, prefix, suffix, and______. (北京邮电大学2010研)12. Words can be classified into variable words and invariable words. As for variable words, they may have______changes. That is, the same word my have different grammatical forms but part of the word remains relatively constant (中山大学2011年研)13. Bound morphemes are classified into two types; ______and______root.14. A word formed by derivation is called a______, and a word formed by compounding is called a______.2. 判断题1. Some linguists maintain that a word group is an extension of word of a particular class. (清华2001研)A. 真B. 假2. Words are the most stable of all linguistic units in respect of their internal structure. (大连外国语学院2008研)A. 真B. 假3. Nouns, verbs, adjectives and many adverbs are content words. (北二外2008研)A. 真B. 假4. Pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions and articles are all open class items. (清华2001研)A. 真B. 假5. The words "loose" and "books" have a common phoneme and a common morpheme as well. (北二外2007研)A. 真B. 假6. Free morpheme may constitute words by themselves. (大连外国语学院2008研)A. 真B. 假7. Root also falls into two categories: free and bound. (北二外2006研)A. 真B. 假8. A stem is the base form of a word which cannot be further analyzed without total loss of identity. (对外经贸2006研)A. 真B. 假9. The words "water" and "teacher" have a common phoneme and a common morpheme as well. (北二外2006研)A. 真B. 假10. The words "boys" and "raise" have a common phoneme and a common morpheme as well. (北二外2008研)A. 真B. 假11. Analogic change refers to the reduction of the number of exceptional or irregular morphemes. (对外经贸2005研)A. 真B. 假12. The smallest meaningful unit of language is allomorph.A. 真B. 假3. 单项选择题1. Words like pronouns, prepositions, conjunctions, articles are______items. (北二外2003研)A. open-classB. closed-classC. neither open-class nor closed-class2. Nouns, verbs and adjectives can be classified as______. (西安交大2008研)A. lexical wordsB. grammatical wordsC. function wordsD. form words3. Bound morphemes do not include______. (西安交大2008研)A. rootsB. prefixesC. suffixesD. words4. ______other **pounds may be divided into roots and affixes. (大连外国语学院2008研)A. Polymorphemic wordsB. Bound morphemesC. Free morphemes5. ______refers to the way in which a particular verb changes for tense, person, or number.(西安外国语学院2006研)A. AffixationB. InflectionC. DerivationD. Conjugation6. Which two terms can best describe the following pairs of words: table—tables, day + break—daybreak. (大连外国语学院2008研)A. inflection **poundB. compound and derivationC. inflection and derivation7. Compound words consist of______ morphemes. (北二外2003研)A. boundB. freeC. both bound and free8. Which of the following words is formed by the process of blending? (对外经贸2006研)A. WTOB. MotelC. BookshelfD. red-faced9. Which of the following words are formed by blending? (对外经贸2005研)A. girlfriendB. televisionC. smogD. bunch10. The word UN is formed in the way of______. (西安交大2008研)A. acronymyB. clippingC. initialismD. blending11. Which of the following is NOT a process of the lexical change? (大连外国语学院2008研)A. INVENTION.B. ACRONYM.C. LEXICON.12. Language has been changing, but such changes are not so obvious at all linguistic aspects except that of______. (西安外国语学院2006研)A. phonologyB. lexiconC. syntaxD. semantics13. "Wife", which used to refer to any woman, stands for "a married woman" in modern English. This phenomenon is known as______. (西安交大2008研)A. semantic shiftB. semantic broadeningC. semantic elevationD. semantic narrowing14. It is true that words may shift in meaning, i. e. semantic change. The semantic change of the word tail belongs to______.A. narrowing of meaningB. meaning shiftC. loss of meaningD. widening of meaning15. A suffix is an affix which appears______.A. after the stemB. before the stemC. in the middle of the stemD. below the stem4. 简答题1. What is the distinction between inflectional affixes and derivational affixes? (四川大学2007研)2. What does the concept morphophoneme mean? What is the relationship between phoneme and morphophoneme?(南开大学2004研)3. What are phonologically conditioned and morphologically conditioned form of morphemes? (武汉大学2005研)4. How are affixes classified? (四川大学2008研)5. A number interesting word-formation processes can be discerned in the following examples. Can you identify what is going on in these?(a) The deceased's cremains were scattered over the hill.(b) He's always taking pills, either uppers or downers. (上海交通大学2007研)6. How to distinguish root and stem?7. Illustrate the relationship between morpheme and allomorph by examples.8. What are closed-class words and open-class words?6. 名词解释1. Open-class words (浙江大学2007研)2. Lexical word (武汉大学2005研)3. Morpheme (武汉大学2008研)4. Stem (四川大学2007研)5. inflectional morpheme (南开大学2004研)6. Free morphemes (西安交大2008研)7. Bound morpheme (上海交大2007研)8. Inflection (四川大学2007研)9. Compound (四川大学2007研)10. Allomorph (四川大学2006研)11. Back-formation(四川大学2008研;北外2010研)12. Prefix (北外2010研)13. cognate(南开大学2011年研)13. 举例说明题1. Illustrate lexical change proper with the latest examples in English, covering at least four aspects. (大连外国语学院2008研)2. Semantic change plays a very important role in widening the vocabulary of a language. (中山大学2008研)3. Illustrate the ways of lexical change. (武汉大学2005研)4. What are the major types of semantic Changes? (人大2006研)。

1。

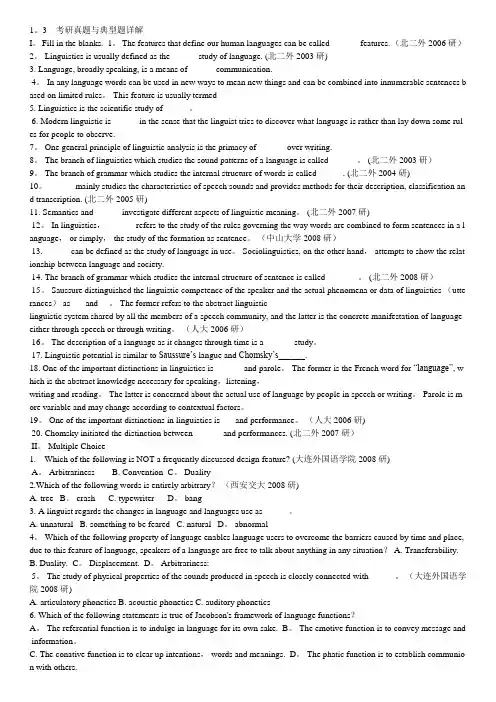

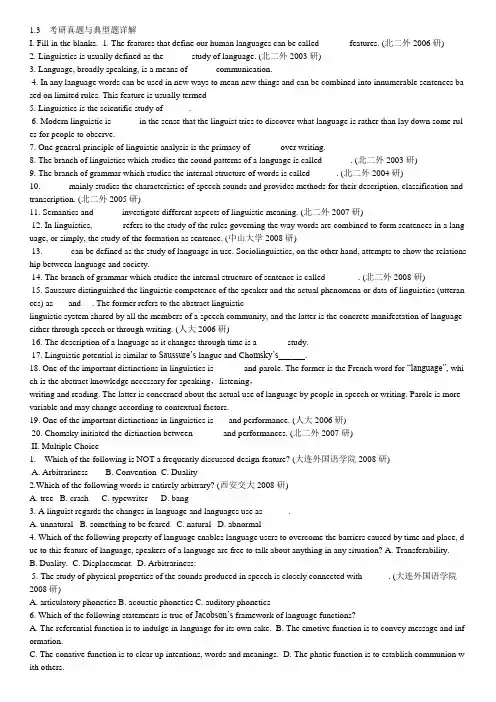

3考研真题与典型题详解I。

Fill in the blanks. 1。

The features that define our human languages can be called ______ features. (北二外2006研)2。

Linguistics is usually defined as the ______study of language. (北二外2003研)3. Language, broadly speaking, is a means of______ communication.4。

In any language words can be used in new ways to mean new things and can be combined into innumerable sentences b ased on limited rules。

This feature is usually termed______5. Linguistics is the scientific study of______。

6. Modern linguistic is______ in the sense that the linguist tries to discover what language is rather than lay down some rul es for people to observe.7。

One general principle of linguistic analysis is the primacy of ______ over writing.8。

The branch of linguistics which studies the sound patterns of a language is called ______。

Discourse analysis (DA), or discourse studies, is a general term for a number of approaches to analyzing written, spoken, signed language use or any significant semiotic event.The objects of discourse analysis—discourse, writing, talk, conversation, communicative event, etc.—are variously defined in terms of coherent sequences of sentences, propositions, speech acts or turns-at-talk. Contrary to much of traditional linguistics, discourse analysts not only study language use 'beyond the sentence boundary', but also prefer to analyze 'naturally occurring' language use, and not invented examples. This is known as corpus linguistics; text linguistics is related. The essential difference between discourse analysis and text linguistics is that it aims at revealing socio-psychological characteristics of a person/persons rather than text structure[1].Discourse analysis has been taken up in a variety of social science disciplines, including linguistics, sociology, anthropology, social work, cognitive psychology, social psychology, international relations, human geography, communication studies and translation studies, each of which is subject to its own assumptions, dimensions of analysis, and methodologies. Sociologist Harold Garfinkel was another influence on the discipline: see below.HistorySome scholars consider the Austrian emigre Leo Spitzer's Stilstudien [Style Studies] of 1928 the earliest example of discourse analysis (DA); Michel Foucault himself translated it into French. But the term first came into general use following the publication of a series of papers by Zellig Harris beginning in 1952 and reporting on work from which he developed transformational grammar in the late 1930s. Formal equivalence relations among the sentences of a coherent discourse are made explicit by using sentence transformations to put the text in a canonical form. Words and sentences with equivalent information then appear in the same column of an array. This work progressed over the next four decades (see references) into a science of sublanguage analysis (Kittredge & Lehrberger 1982), culminating in a demonstration of the informational structures in texts of a sublanguage of science, that of immunology, (Harris et al. 1989) and a fully articulated theory of linguistic informational content (Harris 1991). During this time, however, most linguists decided a succession of elaborate theories of sentence-level syntax and semantics.Although Harris had mentioned the analysis of whole discourses, he had not worked out a comprehensive model, as of January, 1952. A linguist working for the American Bible Society, James A. Lauriault/Loriot, needed to find answers to some fundamental errors in translating Quechua, in the Cuzco area of Peru. He took Harris's idea, recorded all of the legends and, after going over the meaning and placement of each word with a native speaker of Quechua, was able to form logical, mathematical rules that transcended the simple sentence structure. He then applied the process to another language of Eastern Peru, Shipibo. He taught the theory in Norman, Oklahoma, in the summers of 1956 and 1957 and entered the University of Pennsylvania in the inte rim year. He tried to publish a paper Shipibo Paragraph Structure, but it was delayed until 1970 (Loriot & Hollenbach 1970). In the meantime, Dr. Kenneth Lee Pike, a professor at University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, taught the theory, and one of his students, Robert E. Longacre, was able to disseminate it in a dissertation.Harris's methodology was developed into a system for the computer-aided analysis of natural language by a team led by Naomi Sager at NYU, which has been applied to a number of sublanguage domains, most notably to medical informatics. The software for the Medical Language Processor is publicly available on SourceForge.In the late 1960s and 1970s, and without reference to this prior work, a variety of other approaches to a new cross-discipline of DA began to develop in most of the humanities and social sciences concurrently with, and related to, other disciplines, such as semiotics, psycholinguistics, sociolinguistics, and pragmatics. Many of these approaches, especially those influenced by thesocial sciences, favor a more dynamic study of oral talk-in-interaction.Mention must also be made of the term "Conversational analysis", which was influenced by the Sociologist Harold Garfinkel who is the founder of Ethnomethodology.In Europe, Michel Foucault became one of the key theorists of the subject, especially of discourse, and wrote The Archaeology of Knowledge on the subject.[edit] T opics of interestTopics of discourse analysis include:∙The various levels or dimensions of discourse, such as sounds (intonation, etc.), gestures, syntax, the lexicon, style, rhetoric, meanings, speech acts, moves, strategies, turns and other aspects of interaction∙Genres of discourse (various types of discourse in politics, the media, education, science, business, etc.)∙The relations between discourse and the emergence of syntactic structure∙The relations between text (discourse) and context∙The relations between discourse and power∙The relations between discourse and interaction∙The relations between discourse and cognition and memory[edit] PerspectivesThe following are some of the specific theoretical perspectives and analytical approaches used in linguistic discourse analysis:∙Emergent grammar∙Text grammar (or 'discourse grammar')∙Cohesion and relevance theory∙Functional grammar∙Rhetoric∙Stylistics (linguistics)∙Interactional sociolinguistics∙Ethnography of communication∙Pragmatics, particularly speech act theory∙Conversation analysis∙V ariation analysis∙Applied linguistics∙Cognitive psychology, often under the label discourse processing, studying the production and comprehension of discourse.∙Discursive psychology∙Response based therapy (counselling)∙Critical discourse analysis∙Sublanguage analysisAlthough these approaches emphasize different aspects of language use, they all view language as social interaction, and are concerned with the social contexts in which discourse is embedded. Often a distinction is made between 'local' structures of discourse (such as relations among sentences, propositions, and turns) and 'global' structures, such as overall topics and the schematic organization of discourses and conversations. For instance, many types of discourse begin with some kind of global 'summary', in titles, headlines, leads, abstracts, and so on.A problem for the discourse analyst is to decide when a particular feature is relevant to thespecification is required. Are there general principles which will determine the relevance or nature of the specification.[2][edit] Prominent discourse analystsMarc Angenot, Robert de Beaugrande, Jan Blommaert, Adriana Bolivar, Carmen Rosa Caldas-Coulthard, Robyn Carston, Wallace Chafe, Paul Chilton, Guy Cook, Malcolm Coulthard, James Deese, Paul Drew, Alessandro Duranti, Brenton D. Faber, Norman Fairclough, Michel Foucault, Roger Fowler, James Paul Gee, Talmy Givón, Charles Goodwin, Art Graesser, Michael Halliday, Zellig Harris, John Heritage, Janet Holmes, Paul Hopper, Gail Jefferson, Barbara Johnstone, Walter Kintsch, Richard Kittredge, Adam Jaworski, William Labov, George Lakoff, Stephen H. Levinson, James A. Lauriault/Loriot, Robert E. Longacre, Jim Martin, David Nunan, Elinor Ochs, Jonathan Potter, Edward Robinson, Nikolas Rose, Harvey Sacks, Svenka Savic Naomi Sager, Emanuel Schegloff, Deborah Schiffrin, Michael Schober, Stef Slembrouck, Michael Stubbs, John Swales, Deborah Tannen, Sandra Thompson, Teun A. van Dijk, Theo van Leeuwen, Jef V erschueren, Henry Widdowson, Carla Willig, Deirdre Wilson, Ruth Wodak, Margaret Wetherell, Ernesto Laclau, Chantal Mouffe, Judith M. De Guzman, Cynthia Hardy, Louise J. Phillips[edit] Further reading1.^Y atsko V.A. Integrational discourse analysis conception2.^ Gillian Brown "discourse Analysis"∙Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.∙Brown, G., and George Yule (1983). Discourse Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.∙Carter, R. (1997). Investigating English Discourse. London: Routledge.∙Gee, J. P. (2005). An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. London: Routledge.∙Deese, James. Thought into Speech: The Psychology og a Language.Century Psychology Series. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 1984.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1952a). "Culture and Style in Extended Discourse". Selected Papers from the 29th International Congress of Americanists (New Y ork, 1949), vol.III: Indian Tribes of Aboriginal America ed. by Sol Tax & Melville J[oyce] Herskovits, 210-215. New Y ork:Cooper Square Publishers. (Repr., New Y ork: Cooper Press, 1967. Paper repr. in 1970a,pp. 373–389.) [Proposes a method for analyzing extended discourse, with example analyses from Hidatsa, a Siouan language spoken in North Dakota.]∙Harris, Zellig S. (1952b.) "Discourse Analysis". Language 28:1.1-30. (Repr. in The Structure of Language: Readings in the philosophy of language ed. by Jerry A[lan] Fodor & JerroldJ[acob] Katz, pp. 355–383. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1964, and also in Harris 1970a, pp. 313–348 as well as in 1981, pp. 107–142.) French translation "Analyse dudiscours". Langages (1969) 13.8-45. German translation by Peter Eisenberg, "Textanalyse".Beschreibungsmethoden des amerikanischen Strakturalismus ed. by Elisabeth Bense, Peter Eisenberg & Hartmut Haberland, 261-298. München: Max Hueber. [Presents a method for the analysis of connected speech or writing.]∙Harris, Zellig S. 1952c. "Discourse Analysis: A sample text". Language 28:4.474-494. (Repr.in 1970a, pp. 349–379.)∙Harris, Zellig S. (1954.) "Distributional Structure". Word 10:2/3.146-162. (Also in Linguistics Today: Published on the occasion of the Columbia University Bicentennial ed.by Andre Martinet & Uriel Weinreich, 26-42. New Y ork: Linguistic Circle of New Y ork,1954. Repr. in The Structure of Language: Readings in the philosophy of language ed. byJerry A[lan] Fodor & Jerrold J[acob] Katz, 33-49. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall,1964, and also in Harris 1970.775-794, and 1981.3-22.) French translation "La structure distributionnelle,". A nalyse distributionnelle et structurale ed. by Jean Dubois & Françoise Dubois-Charlier (=Langages, No.20), 14-34. Paris: Didier / Larousse.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1963.) Discourse Analysis Reprints. (= Papers on Formal Linguistics, 2.) The Hague: Mouton, 73 pp. [Combines Transformations and Discourse Analysis Papers 3a, 3b, and 3c. 1957, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. ]∙Harris, Zellig S. (1968.) Mathematical Structures of Language. (=Interscience Tracts in Pure and Applied Mathematics, 21.) New Y ork: Interscience Publishers John Wiley & Sons).French translation Structures mathématiques du langage. Transl. by Catherine Fuchs.(=Monographies de Linguistique mathématique, 3.) Paris: Dunod, 248 pp.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1970.) Papers in Structural and Transformational Linguistics. Dordrecht/ Holland: D. Reidel., x, 850 pp. [Collection of 37 papers originally published 1940-1969.]∙Harris, Zellig S. (1981.) Papers on Syntax. Ed. by Henry Hiż. (=Synthese Language Library,14.) Dordrecht/Holland: D. Reidel, vii, 479 pp.]∙Harris, Zellig S. (1982.) "Discourse and Sublanguage". Sublanguage: Studies of language in restricted semantic domains ed. by Richard Kittredge & John Lehrberger, 231-236. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1985.) "On Grammars of Science". Linguistics and Philosophy: Essays in honor of Rulon S. Wells ed. by Adam Makkai & Alan K. Melby (=Current Issues inLinguistic Theory, 42), 139-148. Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1988a) Language and Information. (=Bampton Lectures in America, 28.) New Y ork: Columbia University Press, ix, 120 pp.∙Harris, Zellig S. 1988b. (Together with Paul Mattick, Jr.) "Scientific Sublanguages and the Prospects for a Global Language of Science". Annals of the American Association ofPhilosophy and Social Sciences No.495.73-83.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1989.) (Together with Michael Gottfried, Thomas Ryckman, Paul Mattick, Jr., Anne Daladier, Tzvee N. Harris & Suzanna Harris.) The Form of Information in Science: Analysis of an immunology sublanguage. Preface by Hilary Putnam. (=Boston Studies in the Philosophy of, Science, 104.) Dordrecht/Holland & Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, xvii, 590 pp.∙Harris, Zellig S. (1991.) A Theory of Language and Information: A mathematical approach.Oxford & New Y ork: Clarendon Press, xii, 428 pp.; illustr.∙Jaworski, A. and Coupland, N. (eds). (1999). The Discourse Reader. London: Routledge.∙Johnstone, B. (2002). Discourse analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.∙Kittredge, Richard & John Lehrberger. (1982.) Sublanguage: Studies of language in restricted semantic domains. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.∙Loriot, James and Barbara E. Hollenbach. 1970. "Shipibo paragraph structure." Foundations of Language 6: 43-66. The seminal work reported as having been admitted by Longacre and Pike. See link below from Longacre's student Daniel L. Everett.∙Longacre, R.E. (1996). The grammar of discourse. New Y ork: Plenum Press.∙Miscoiu, S., Craciun O., Colopelnic, N. (2008). Radicalism, Populism, Interventionism.Three Approaches Based on Discourse Theory. Cluj-Napoca: Efes.∙Renkema, J. (2004). Introduction to discourse studies. Amsterdam: Benjamins.∙Sager, Naomi & Ngô Thanh Nhàn. (2002.) "The computability of strings, transformations, and sublanguage". The Legacy of Zellig Harris: Language and information into the 21st Century, V ol. 2: Computability of language and computer applications, ed. by Bruce Nevin, John Benjamins, pp. 79–120.∙Schiffrin, D., Deborah Tannen, & Hamilton, H. E. (eds.). (2001). Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Oxford: Blackwell.∙Stubbs, M. (1983). Discourse Analysis: The sociolinguistic analysis of natural language.Oxford: Blackwell∙Teun A. van Dijk, (ed). (1997). Discourse Studies. 2 vols. London: Sage.Potter, J, Wetherall, M. (1987). Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. London: SAGE.[edit]。

Continued Fractions and DynamicsStefano Isola【期刊名称】《应用数学(英文)》【年(卷),期】2014(5)7【摘要】Several links between continued fractions and classical and less classical constructions in dynamical systems theory are presented and discussed.【总页数】24页(P1067-1090)【关键词】Continued;Fractions;Fast;and;Slow;Convergents;Irrational;Rotations;Farey;a nd;Gauss;Maps;Transfer;Operator;Thermodynamic;Formalism【作者】Stefano Isola【作者单位】Dipartimento di Matematica e Informatica, Università degli Studi di Camerino, Camerino Macerata, Italy【正文语种】中文【中图分类】O1【相关文献】1.Quantitative Poincare recurrence in continued fraction dynamical system [J], PENG Li;TAN Bo;WANG BaoWei2.MULTIFRACTAL ANALYSIS OF THE CONVERGENCE EXPONENT INCONTINUED FRACTIONS [J], 房路路;马际华;宋昆昆;吴敏3.Continued Fraction Method for Approximation of Heat Conduction Dynamics in a Semi-Infinite Slab [J], Jietae Lee;Dong Hyun Kim4.Gravity Field Imaging by Continued Fraction Downward Continuation: A Case Study of the Nechako Basin(Canada) [J], ZHANG Chong;ZHOU Wenna;LV Qingtian;YAN Jiayong5.On Continued Fractions and Their Applications [J], Zakiya M. Ibran;EfafA. Aljatlawi;Ali M. Awin因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

带极性侧链的环[6]芳酰胺的球形自组装杨永安1袁立华1胡晋川1邹树良1冯文1,*龚兵2(1四川大学化学学院,教育部辐射物理与技术重点实验室,原子核科学与技术研究所,成都610064;2Department of Chemistry,the State University of New York at Buffalo,Buffalo,New York14260,USA)摘要:环芳酰胺是一类基于三中心氢键促进,经寡聚前体一步大环合成法得到的刚性大环分子.通过紫外-可见(UV -Vis)光谱、动态光散射(DLS)、扫描电镜(SEM)、透射电镜(TEM)和原子力显微镜(AFM)等实验手段,详细考察了侧链为三甘醇单甲基醚链,由六个苯环单元组成的环[6]芳酰胺的自组装行为.实验结果表明,该大环在1,2-二氯乙烷中发生自组装,其组装聚集体随温度升高产生从聚集体到单分子的解聚变化,至70℃时几乎完全解聚;在由良溶剂(二氯甲烷)和不良溶剂(芳烃类)组成的混合溶剂中,带有三甘醇醚链的环[6]芳酰胺化合物1自组装成微球,结合热稳定性实验和TEM 证实是实心微球而非囊泡.进一步发现微球形成和形貌依赖于混合溶剂中不良溶剂的极性和种类,芳烃类溶剂有利于微球形成,而烷烃和极性溶剂则不利,后者更倾向于形成膜的结构.关键词:自组装;环芳酰胺;大环;三中心氢键中图分类号:O647Spherical Assemblies of Cyclo[6]aramide withPolar Side ChainsYANG Yong -An 1YUAN Li -Hua 1HU Jin -Chuan 1ZOU Shu -Liang 1FENG Wen 1,*GONG Bing 2(1College of Chemistry,Key Laboratory for Radiation Physics and Technology of Ministry of Education,Institute of Nuclear Scienceand Technology,Sichuan University,Chengdu 610064,P.R.China ;2Department of Chemistry,the State University ofNew York at Buffalo,Buffalo,New York 14260,USA )Abstract :Cyclic aromatic oligoamides are a new class of recently discovered shape -persistent macrocycles.These molecules are prepared in high yields based on a one -step macrocyclization strategy that relies on hydrogen bond -enforced folding of the corresponding uncyclized oligomeric precursors.Macrocycle 1is a member of a series of six -residue macrocycles dubbed cyclo[6]aramides and bears polar side chains derived from tri(ethylene glycol)monomethyl ether.We investigated its self -assembly using multiple techniques including UV -Vis spectrum,dynamic light -scattering (DLS),scanning electron microscopy (SEM),transmission electron microscopy (TEM),and atomic force microscopy (AFM).Results from these experiments demonstrated that 1aggregates in apolar solvents such as 1,2-dichloroethane.As temperature increases,the supramolecular aggregates gradually disintegrate into molecularly dissolved species.For example,at 70℃,compound 1exists mainly in its molecularly dissolved form.In mixed solvents consisting of good (dichloromethane)and poor (aromatic hydrocarbons)components,compound 1aggregates into spherical assemblies.These self -assembling spheres were shown by studies on thermal stability and by TEM imaging to be solid balls instead of hollow vesicles.The formation of the microspheres was found to be dependent on the properties of the poor solvents as their formation was promoted in aromatic hydrocarbons and obliteratedin aliphatic and polar solvents.In aliphatic and polar solvents,macrocycle 1was found to assemble into films.[Article]物理化学学报(Wuli Huaxue Xuebao )Acta Phys.-Chim.Sin .,2010,26(6):1557-1564June Received:January 13,2010;Revised:March 5,2010;Published on Web:April 15,2010.*Corresponding author.Email:wfeng9510@;Tel:+86-28-85418755.The project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (20774059).国家自然科学基金(20774059)资助项目鬁Editorial office of Acta Physico -Chimica Sinica1557Acta Phys.-Chim.Sin.,2010Vol.26具有大π共轭体系的刚性环状化合物(shape-persistent macrocycles)的研究近年来十分活跃.与构象容易变化的环相比,这类大环化合物的骨架呈刚性,构筑基元之间转动的构象自由度非常有限,由此产生很大的分子表面,通过环平面的π-π堆积作用等,可自组装形成不同类型的纳米分子结构,如纳米管、线和囊泡等[1-8],在药物输送和缓释、人工离子通道、液晶等[9-12]方面表现出独特的性质.环芳酰胺是一类以芳环[13-14]为构筑基元,通过酰胺键连接而形成的寡聚环状分子,由于其环内同时含有氢键受体和供体[15],这类大环在分子识别和自组装上具有重要的作用[7,10,16-17],但这类分子骨架一般仍具有相当程度的构象可变性.近年来发现,采用含邻位烷氧基的间位取代二酸和二胺,在低温下,“一锅煮”可获得高产率环化芳酰胺产物,这是将两种或多种小分子单体简单混合的传统缩聚方法无法做到的.这一利用三中心分子内氢键导向的成环方法,不仅合成简单、产率高(如环[6]芳酰胺,可达80%),而且环化反应无需在一般成环要求的高稀淡条件下进行,作为副产物的线性聚合物也很少[19].基于分子内三中心氢键构筑的刚性环芳酰胺,如环[6]芳酰胺,不同于一般的芳酰胺大环,分子内氢键[18]限制这类分子的酰胺键自由转动,由于构筑基元中苯环酰胺基团采取的是间位或对位组合关系,使得活性寡聚前体链骨架采取弯曲构象,特别是两个远程活性端基的位阻效应,导致长度大于一圈的寡聚中间体很难形成,最终导致首尾偶联闭环占主导地位,进而高效动力学成环[19-21],这类环芳酰胺分子中苯环羰基氧指向环内中间,而一般文献报道[22-24]的芳酰胺大环中的羰基氧朝向环外,因此可以络合大的阳离子,如胍离子[16].我们最近的研究发现,尽管分子内氢键促使这类大环分子骨架呈现刚性,但局部的柔韧性依然存在[25],一步反应仍可得到部分环[8]芳酰胺[26].而相对于环[8]聚体,环[6]芳酰胺分子结构呈浅碗状,更接近于平面,有可能通过π-π堆积作用进一步组装.研究有关大环分子的自组装,将促进对这类新型的刚性环芳酰胺分子构筑纳米结构的认识.迄今对这类刚性环芳酰胺的自组装研究尚未见文献报道.本文首次研究了带有三甘醇醚链的环[6]芳酰胺1(图1)在不同溶剂体系中的自组装性能,用扫描电镜(SEM)、透射电镜(TEM)、原子力显微镜(AFM)、紫外-可见(UV-Vis)光谱和动态光散射(DLS)等探讨了组装形成球形微纳米结构的现象.1实验部分1.1环芳酰胺的制备环[6]芳酰胺1按文献[19]方法,从4,5-二甲氧基-2,3-苯二胺与侧链带三甘醇甲醚的间苯二酸酰氯在三乙胺存在下反应得到,45℃真空干燥4h,所得白色粉末纯度>98%,MALDI-TOF和1H NMR谱鉴定结构数据与文献报道[19]一致.1.2大环自组装制样方法先配制成一定浓度(2-8mmol·L-1)的二氯甲烷溶液,然后滴加到云母或玻璃片上,待自然挥发干后进行SEM测试.TEM制样方法类似,但所用基材为纯碳膜铜网且需在45℃下真空干燥2h后进行测试.AFM制样方法除基材是在云母片上外,其余的与TEM一样.测定DLS制样时采用三氯甲烷,配制成浓度为5mmol·L-1溶液,用孔径为220nm的过滤筛进行过滤.测量温度:25℃,入射光波长532nm,扫描时间3min,扫描角度90°.所用试剂除氯仿(色谱级;TEDIA公司生产)外均为分析纯.1.3表征采用日本日立公司的Hitachi S-450型扫描电镜(加速电压为20kV),日本电子株式会社(JEOL)的JEM-100CX型透射电镜(加速电压为80kV)和美Key Words:Self-assembly;Cyclic aramide;Macrocycle;Three-center hydrogen bond图1环[6]芳酰胺(1)的结构Fig.1Structure of cyclo[6]aramide (1) 1558No.6杨永安等:带极性侧链的环[6]芳酰胺的球形自组装国Vecco公司的型号为NanoScope MultiMode&Explore型的原子力显微镜(轻敲模式,单晶硅探针)观察合成样品形貌;采用日本SHIMADZ公司型号为UV-2450的紫外-可见分光光度计进行紫外测试.采用美国Brookhaven公司生产的型号为MalvernZetasizer Nano S动态光散射仪进行粒径测试,扫描角度为90°,采用氦氖激光光源(λ=532nm).2结果与讨论2.1自组装过程环[6]芳酰胺在1H NMR谱中(CDCl3)不同浓度(0.2-50mmol·L-1)下没有出现峰形明显变化或质子位移.当采用变温UV-Vis光谱(图2),观察到237nm处的峰位,随着温度升高吸光度逐渐降低,70℃时几乎消失,同时发生蓝移.说明低温时发生分子间堆积,提高温度自组装体逐渐被破坏[27-29].在10-60℃温度区间,237nm波长处出现等吸收点,一般认为是聚集体与单一自由分子相互转变过程的标志[30-32],即在溶液中存在两相,在低温下大环主要是以聚集体的形式存在,而在高温下则是以自由分子或几个分子聚集的形式存在.当温度达到70℃时,吸光度陡降,推测此时分子聚集体发生解聚,主要以单一分子形式存在.动态光散射(DLS)实验进一步提供了发生自组装的证据.如图3,新配制经短暂放置的溶液直接进行测试,平均粒径仅为3nm,而静置24h,平均粒径增大到998nm左右.由于一个化合物单分子的尺寸小于3nm,因此说明是单分子或几个分子在静置过程中堆积成更大的聚集体.与平均粒径为90nm的未成环的芳酰胺五聚体相比[33],成环后环[6]芳酰胺聚集体尺寸增加了11倍,这说明多了一个构筑单元,分子聚集的程度发生了很大的变化.鉴于测试前溶液是先经过孔径为220nm的过滤筛进行过滤,然后静置后测试,而静置24h后测试出的粒径远大于过滤筛的孔径,这有力地说明了过滤后样品分子在溶液里通过非共价键作用力自组装形成了聚集体.2.2自组装形貌分析从二氯甲烷与对二甲苯溶剂制样得到如图4的SEM结果.可见,环分子之间堆积成球状,直径0.5-6μm.尽管微球大小不是很均匀,但形状比较规整且光滑.值得注意的是,大环π-π堆积倾向于形成管状结构,但这里得到的是球状体.原因可能是由于化合物周围的侧链是具有亲水性的醚链,此侧链在有机溶剂里彼此之间相互聚集缠绕,当这侧链聚集能力大于环与环之间的π-π作用时,就形成了球状体.这种球状体十分稳定,因为于60℃加热3.5h形貌几乎没有发生改变(图5),据此推测可能为实心球.为进一步证实这一推测,制样后立刻放置到较图2在1,2-二氯乙烷中不同温度下样品1的紫外-可见光谱图Fig.2UV-Vis absorption spectra of the sample1in 1,2-dichloroethane at different temperatures concentration:0.01mmol·L-1,temperature:10,20,30,40,50,60,70℃图3样品1的动态光散射图Fig.3DLS spectra of the sample1standing at25℃for overnight(A),1h (B)15591560Acta Phys.-Chim.Sin.,2010Vol.26图4样品1滴加到玻璃片上并干燥后的扫描电镜图Fig.4SEM images of the sample1drop-casted and dried on glass platelarge-area image showing microspheres(A),a zoomed-in image(B)图5在云母上样品1的扫描电镜图Fig.5SEM images of the sample1on micaheated at60℃for3.5h(A),evaporating solvent at room temperature(B)图6样品1在不同温度加热2h的扫描电镜图Fig.6SEM images of the sample1after heating for2h at different temperatures(A)60℃,(B)75℃,(C)90℃,(D)45℃(in vaccum)No.6杨永安等:带极性侧链的环[6]芳酰胺的球形自组装高温度或真空的环境中,在溶剂迅速挥发的情况下,考察了不同温度(45-90℃)以及真空条件下(45℃,2 h)对自组装后球状体形貌的影响,部分结果见图6.可以看到,在溶剂迅速挥发干的情况下,微球整体分布和形貌随温度升高,在60和75℃时都可观察到发生较大变化(图6A和6B),但并没有发生微球破裂的情况;在较高温度90℃的情况下(图6C),样品可能已有轻微熔化,球体之间出现粘连和融合,真空状态下球体形貌完整(图6D),这说明此球状体可能是实心的而非囊泡.TEM实验发现(图7(A-C)),放大图7D中,球体中间颜色深,边沿浅,进一步证明此微球为实心球,在制样条件下得到的微球直径为100-300nm.为了进一步证明堆积后的球状形貌,还用AFM 进行了表征.如图8所示,自组装体尺寸一般在250-500nm.从截面分析可以看出,由于直径与高度比为429.7∶13.3=32.3,因此得到的球体形貌是扁平状.这一现象可能是由于分子之间包结的溶剂分子在制样过程中挥发导致堆积坍陷所致.2.3溶剂极性和种类对自组装影响为了考察溶剂的极性和种类对自组装结构的影响[34],就分别比较了芳香溶剂,烷烃溶剂和极性溶剂.图7样品1滴加到纯碳膜铜网上并干燥后的透射电镜图Fig.7TEM images of the sample1drop-casted and dried on carbon film(A)large-area image showing microshperes;(B),(C)different areas containing microspheres;(D)a zoomed-in image over the microspheres marked in C图8在云母上样品1的轻敲模式原子力显微镜电镜图和横截面分析图Fig.8Tapping-mode AFM image of the sample1drop-casted on mica and the correspondingcross-section analysis1561Acta Phys.-Chim.Sin.,2010Vol.26当采用苯、均三甲苯、间二甲苯和邻二甲苯等芳香类溶剂作为不良溶剂代替对二甲苯进行制样,从SEM 图上都能看到球状形貌(图9).由于溶解度的原因,从二氯甲烷-苯体系制得样品分子之间融合程度较高(图9A),而二甲苯控制球形效果最好,三甲苯次之.图10在烷烃溶剂中样品1的扫描电镜图Fig.10SEM images of the sample 1prepared in aliphatic solvents(A)dichloromethane -n -pentane,(B)dichloromethane -cyclohexane,(C)dichloromethane -n -hexane,(D)dichloromethane -petroleum ether图9在芳香类溶剂中样品1的扫描电镜图Fig.9SEM images of the sample 1prepared in aromatic solvents(A)dichloromethane -benzene,(B)dichloromethane -mesitylene,(C)dichloromethane -m -xylene,(D)dichloromethane -o -xyene1562No.6杨永安等:带极性侧链的环[6]芳酰胺的球形自组装相比之下,用正戊烷、正己烷、环己烷、石油醚等烷烃溶剂代替对二甲苯采用类似方法进行制样,形成了不均匀的膜或团聚体的形貌(图10).所观察到的结果之间的差异可能与样品分子在该混合溶剂中的溶解性有关.采用极性溶剂甲醇、乙腈或乙酸乙酯替代对二甲苯作为不良溶剂,只观察到形成膜结构(图11),不能得到微球.这说明极性溶剂不利于形成球体形貌.在极性溶剂中,大环分子间的弱相互作用几乎完全被破环,侧链伸展,与溶剂作用加强,宏观上更容易表现为膜.可见,溶剂极性对微球形貌影响很大,芳烃溶剂有利于形成球状体,可能是由于芳烃溶剂的苯环在自组装过程中起到模板或诱导作用,而不含有苯环的烃类溶剂和极性溶剂则倾向于成膜.3结论紫外-可见光谱和动态光散射证实,侧链带醚链的环[6]芳酰胺分子会自发地进行自组装,在低温状态下,有利于自组装,而随着温度的升高自组装体逐渐被破坏,70℃时大环聚集体完全解聚,在溶液中以单一分子形式存在.电镜实验(SEM,TEM)和原子力显微镜(AFM)表明,在二氯甲烷-对二甲苯溶剂中容易自组装聚集成实心球体,该实心微球形貌与制样时不良溶剂的极性和种类有关,芳香溶剂可能因苯环的模板或诱导作用有利于球形聚集体的形成,而烷烃类,如正己烷,以及极性溶剂,如甲醇等则不利,后者更倾向于成膜.由于环[6]芳酰胺分子呈浅碗状,加之极性侧链之间的相互作用的影响,导致形成球形组装结构,进一步改变侧链结构有可能调控分子的聚集行为.References1Zang,L.;Che,Y.K.;Moore,J.S.Acc.Chem.Res.,2008,41:1596 2Ono,K.;Tsukamoto,K.;Hosokawa,R.;Kato,M.;Suganuma,M.;Tomura,M.;Sako,K.;Taga,K.;Saito,K.Nano Lett.,2009,9:122 3Balakrishnan,K.;Datar,A.;Zhang,W.;Yang,X.M.;Naddo,T.;Huang,J.L.;Zuo,J.M.;Yen,M.;Moore,J.S.;Zang,L.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2006,128:65764Cheng,X.H.;Ju,X.P.;Hoeger,.Chem.,2006,26: 733[程晓红,鞠秀萍,Hoeger,S.有机化学,2006,26:733]5Shu,L.J.;Müri,M.;Krupke,R.;Mayor,.Biomol.Chem., 2009,7:10816Xiao,Z.Y.;Zhao,X.;Jiang,X.K.;Li,.Biomol.Chem., 2009,7:25407Xu,X.N.;Wang,L.;Li,mun.,2009:66348Seo,S.H.;Chang,J.Y.;Tew,G.N.Angew.Chem.Int.Edit., 2006,45:75269H觟ger,S.;Cheng,X.H.;Ramminger,A.D.;Enkelmann,V.;Rapp,A.;Mondeshki,M.;Schnell,I.Angew.Chem.Int.Edit.,2005,44:280110Helsel,A.J.;Brown,A.L.;Yamato,K.;Feng,W.;Yuan,L.H.;Clements,A.J.;Harding,S.V.;Szabo,G.;Shao,Z.F.;Gong,B.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2008,130:1578411Seo,S.H.;Jones,T.V.;Seyler,H.;Peters,J.O.;Kim,T.H.;Chang,J.Y.;Tew,G.N.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2006,128:926412Xie,Z.;Zhang,W.;Huang,.Chem.,2002,22: 543[谢政,张炜,黄鹏程.有机化学,2002,22:543]13Szumna,A.;Jurczak,J.Helv.Chim.Acta,2001,84:376014B觟hme,F.;Kunert,C.;Komber,H.;Voigt,D.;Friedel,P.;Khodja, M.;Wilde,H.Macromolecules,2002,35:423315Dixon,D.A.;Dobbs,K.D.;Valentini,J.J.J.Phys.Chem.,1994, 98:1343516Sanford,A.R.;Yuan,L.H.;Feng,W.;Yamato,K.;Flowersb,R.A.;Gong,mun.,2005:472017Yamato,K.;Yuan,L.H.;Feng,W.;Helsel,A.J.;Sanford,A.R.;Zhu,J.;Deng,J.G.;Zeng,X.C.;Gong,.Biomol.Chem.,2009,7:364318(a)Parra,R.D.;Zeng,H.;Zhu,J.;Zheng,C.;Zeng,X.C.;Gong,图11在极性溶剂中样品1的扫描电镜图Fig.11SEM images of the sample1prepared in polar solvents(A)dichloromethane-methanol,(B)dichloromethane-acetonitrile1563Acta Phys.-Chim.Sin.,2010Vol.26B.Chem.Eur.J.,2001,7:4352(b)Parra,R.D.;Gong,B.;Zeng,X.C.J.Chem.Phys.,2001,115:603619Yuan,L.H.;Feng,W.;Yamato,K.;Sanford,A.R.;Xu,D.G.;Guo,H.;Gong,B.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2004,126:1112020Wen,W.;Yamato,K.;Yang,L.Q.;Ferguson,J.;Zhong,L.J.;Zou, S.L.;Yuan,L.H.;Zeng,X.C.;Gong,B.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2009, 131:262921Gong,B.Acc.Chem.Res.,2008,41:137622Meshcheryakov,D.;B觟hmer,V.;Bolte,M.;Hubscher-Bruder,V.;Arnaud-Neu,F.;Herschbach,H.;Dorsselaer,A.V.;Thondorf,I.;M觟gelin,V.Angew.Chem.Int.Edit.,2006,45:164823Qin,B.;Chen,X.Y.;Fang,X.;Shu,Y.Y.;Yip,Y.K.;Yan,Y.;Pan,S.Y.;Ong,W.Q.;Ren,C.L.;Su,H.B.;Zeng,.Lett.,2008,10:512724Kang,S.W.;Gothard,C.M.;Maitra,S.;Atia-tul-Wahab;Nowick, J.S.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2007,129:148625Yang,L.Q.;Zhong,L.J.;Yamato,K.;Zhang,X.H.;Feng,W.;Deng,P.C.;Yuan,L.H.;Zeng,X.C.;Gong,B.New J.Chem.,2009,33:72926Zou,S.L.;He,Y.Z.;Yang,Y.A.;Zhao,Y.;Yuan,L.H.;Feng,W.;Yamato,K.;Gong,B.Synlett,2009,9:143727Balakrishnan,K.;Datar,A.;Oitker,R.;Chen,H.;Zuo,J.M.;Zang, L.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2005,127:1049628Jonkheijm,P.;Miura,A.;Zdanowska,M.;Hoeben,F.J.M.;Feyter, S.D.;Schenning,A.H.J.;Schryver,F.C.D.;Meijer,E.W.Angew.Chem.Int.Edit.,2004,116:7629Balakrishnan,K.;Datar,A.;Naddo,T.;Huang,J.L.;Oitker,R.;Yen,M.;Zhao,J.C.;Zang,L.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2006,128:7390 30Schenning,A.P.H.J.;Jonkheijm,P.;Peeters,E.;Meijer,E.W.J.Am.Chem.Soc.,2001,123:40931Chen,Z.J.;Stepanenko,V.;Dehm,V.;Prins,P.;Siebbeles,L.D.A.;Seibt,J.;Marquetand,P.;Engel,V.;Würthner,F.Chem.Eur.J.,2007,13:43632Hoeben,F.J.M.;Jonkheijm,P.;Meijer,E.W.;Schenning,A.P.H.J.Chem.Rev.,2005,105:149133Zhang,Y.F.;Yamato,K.;Zhong,K.;Zhu,J.;Deng,J.G.;Gong,.Lett.,2008,10:433934Li,Y.J.;Li,X.F.;Li,Y.L.;Liu,H.B.;Wang,S.;Gan,H.Y.;Li, J.B.;Wang,N.;He,X.R.;Zhu,D.B.Angew.Chem.Int.Edit.,2006,45:36391564。

Chapter 12 : Language AndBrain1. neurolinguistics: It is the study of relationship between brain and language. It includes research into how the structure of the brain influences language learning, how and in which parts of the brain languageis stored, and how damage to the brain affects theability to use language.2. psycholinguistics: the study of language processing. It is concerned with the processes of language acqisition, comprehension and production.3. brain lateralization: The localization of cognitive and perceptive functions in a particular hemisphere of the brain.4. dichotic listening: A technique in which stimuli either linguistic or non-linguistic are presented through headphones to the left and right ear to determine the lateralization of cognitive function.5. right ear advantage: The phenomenon that the right ear shows an advantage for the perception of linguistic signals id known as the right ear advantage.6. split brain studies: The experiments thatinvestigate the effects of surgically severing the corpus callosum on cognition are called as split brain studies.7. aphasia: It refers to a number of acquired language disorders due to the cerebral lesions caused by a tumor, an accident and so on.8. non-fluent aphasia: Damage to parts of the brain in front of the central sulcus is called non-fluent aphasia.9. fluent aphasia: Damage to parts of the left cortex behind the central sulcus results in a type of aphasia called fluent aphasia.10. Acquired dyslexia: Damage in and around the angular gyrus of the parietal lobe often causes the impairmentof reading and writing ability, which is referred to as acquired dyslexia.11. phonological dyslexia: it is a type of acquired dyslexia in which the patient seems to have lost the ability to use spelling-to-sound rules.12. surface dyslexia: it is a type of acquired dyslexia in which the patient seems unable to recognize words as whole but must process all words through a set of spelling-to-sound rules.13. spoonerism: a slip of tongue in which the positionof sounds, syllables, or words is reversed, for example, Let’s have chish and fips instend of Let’s have fish and chips.14. priming: the process that before the participants make a decision whether the string of letters is a word or not, they are presented with an activated word.15. frequency effect: Subjects take less time to make judgement on frequently used words than to judge less commonly used words . This phenomenon is called frequency effect.16. lexical decision: an experiment that letparticipants judge whether a string of letter is a word or not at a certain time.17. the priming experiment: An experiment that let subjects judge whether a string of letters is a word or not after showed with a stimulus word, called prime.18. priming effect: Since the mental representation is activated through the prime, when the target is presented, response time is shorter that it otherwise would have been. This is called the priming effect.(06F)19. bottom-up processing: an approach that makes use principally of information which is already present in the data.20. top-down processing: an approach that makes use of previous knowledge and experience of the readers in analyzing and processing information which is received. 21. garden path sentences: a sentence in which the comprehender assumes a particular meaning of a word or phrase but discovers later that the assumption was incorrect, forcing the comprehender to backtrack and reinterpret the sentence.22. slip of the tongue: mistakes in speech whichprovide psycholinguistic evidence for the way we formulate words and phrases.Chapter 11 : Second Language Acquisition1. second language acquisition: It refers to the systematic study of how one person acquires a second language subsequent to his native language.2. target language: The language to be acquired by the second language learner.3. second language: A second language is a language which is not a native language in a country but whichis widely used as a medium of communication and whichis usually used alongside another language or languages.4. foreign language: A foreign language is a language which is taught as a school subject but which is notused as a medium of instruction in schools nor as a language of communication within a country.5. interlanguage: A type of language produced by second and foreign language learners, who are in the processof learning a language, and this type of languageusually contains wrong expressions.6. fossilization: In second or foreign language learning, there is a process which sometimes occurs in which incorrect linguistic features become a permanent part of the way a person speaks or writes a language.7. contrastive analysis: a method of analyzing languages for instructional purposes whereby a native language and target language are compared with a viewto establishing points of difference likely to cause difficulties for learners.8. contrastive analysis hypothesis: A hypothesis in second language acquisition. It predicts that wherethere are similarities between the first and second languages, the learner will acquire second language structure with ease, where there are differences, the learner will have difficulty.9. positive transfer: It refers to the transfer that occur when both the native language and the target language have the same form, thus making learning easier. (06F)10. negative transfer: the mistaken transfer offeatures of one’s native language into a second language.11. error analysis: the study and analysis of errors made by second and foreign language learners in orderto identify causes of errors or common difficulties in language learning.12. interlingual error: errors, which mainly resultfrom cross-linguistic interference at different levels such as phonological, lexical, grammatical etc.13. intralingual error: Errors, which mainly resultfrom faulty or partial learning of the target language, independent of the native language. The typical examples are overgeneralization and cross-association. 14. overgeneralization: The use of previously available strategies in new situations, in which they are unacceptable.15. cross-association: some words are similar in meaning as well as spelling and pronunciation. This internal interference is called cross-association.16. error: the production of incorrect forms in speechor writing by a non-native speaker of a second language, due to his incomplete knowledge of the rules of that target language.17. mistake: mistakes, defined as either intentionallyor unintentionally deviant forms and self-corrigible, suggest failure in performance.18. input: language which a learner hears or receives and from which he or she can learn.19. intake: the input which is actually helpful for the learner.20. Input Hypothesis: A hypothesis proposed by Krashen , which states that in second language learning, it’s necessary for the learner to understand input language which contains linguistic items that are slightly beyond the learner’s present linguistic competence. Eventually the ability to produce language is said to emerge naturally without being taught directly.21. acquisition: Acquisition is a process similar tothe way children acquire their first language. It is a subconscious process without minute learning of grammatical rules. Learners are hardly aware of their learning but they are using language to communicate. It is also called implicit learning, informal learning or natural learning.22. learning: learning is a conscious learning of second language knowledge by learning the rules and talking about the rules.23. comprehensible input: Input language which contains linguistic items that are slightly beyond thelearner’s present linguistic competence. (06F)24. language aptitude: the natural ability to learn a language, not including intelligence, motivation, interest, etc.25. motivation:motivation is defined as the learner’s attitudes and affective state or learning drive.26. instrumental motivation: the motivation that people learn a foreign language for instrumental goals such as passing exams, or furthering a career etc. (06C)27. integrative motivation: the drive that people learna foreign language because of the wish to identify with the target culture. (06C/ 05)28. resultative motivation: the drive that learnerslearn a second language for external purposes. (06F)29. intrinsic motivation: the drive that learners learn the second language for enjoyment or pleasure from learning.30. learning strategies: learning strategies are learners’ conscious goal-oriented and problem-solving based efforts to achieve learning efficiency.31. cognitive strategies: strategies involved in analyzing, synthesis, and internalizing what has been learned. (07C/ 06F)32. metacognitive strategies: the techniques in planning, monitoring and evaluating one’s learning. 33. affect/ social strategies: the strategies dealing with the ways learners interact or communicate with other speakers, native or non-native.Chapter 10: Language Acquisition1. language acquisition:It refers to the child’s acquisition of his mother tongue, i.e. how the child comes to understand and speak the language of his community.2. language acquisition device (LAD): A hypothetical innate mechanism every normal human child is believedto be born with, which allow them to acquire language.(03)3. Universal Grammar: A theory which claims to account for the grammatical competence of every adult no matter what language he or she speaks.4. motherese: A special speech to children used by adults, which is characterized with slow rate of speed, high pitch, rich intonation, shorter and simpler sentence structures etc.----又叫child directed speech,caretaker talk.(05)5. Critical Period Hypothesis: The hypothesis that the time span between early childhood and puberty is the critical period for language acquisition, during which children can acquire language without formalinstruction successfully and effortlessly. (07C/ 06F/ 04)6. under-extension: Use a word with less than its usual range of denotation.7. over-extension: Extension of the meaning of a word beyond its usual domain of application by young children.8. telegraphic speech:Children’s early multiword speech that contains content words and lacks function words and inflectional morphemes.9. content word: Words referring to things, quality, state or action, which have lexical meaning used alone.10. function word: Words with little meaning on their own but show grammatical relationships in and between sentences.11. taboo: Words known to speakers but avoided in some contexts of speech for reasons of religion, politeness etc. (07C)12. atypical development: Some acquisition of language may be delayed but follow the same rules of language development due to trauma or injury.Chapter 9: Language And Culture1. culture : The total way of life of a person, including the patterns of belief, customs, objects, institutions, techniques, and language thatcharacterizes the life of human community.2. discourse community : It refers to the common ways that members of some social group use language to meet their needs.3. acculturation : A process in which changes on the language, culture and system of values of a group happen through interaction with another group with a different language, culture and a system of values.4. Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis : The interdependence of language and thought is now known as Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis.5. linguistic relativity : A belief that the waypeople view the world is determined wholly or partly by the structure of their native language-----又叫Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. (06C)6. linguistic determinism: It refers to the idea that the language we use, to some extent, determines the way in which we view and think about the world around us. (06C)7. denotative meaning: It refers to the literal meaning, which can be found in a dictionary.8. connotative meaning: The association of a word,apart from its primary meaning.9. iconic meaning: The image of a word invoked to people.10. metaphors: A figure of speech, in which no function words like like, as are used. Something is described by stating another thing with which it can be compared.11. euphemism: a word or phrase that replace a taboo word or is used to avoid reference to certain acts or subjects, e.g. powder room for toilet.12. cultural overlap:The situation between twosocieties due to some similarities in the natural environment and psychology of human being13. cultural diffusion: Through communication, some elements of culture A enter culture B and become partof culture B, thus bringing about cultural diffusion. (05/03)14. cultural imperialism: The situation of increasing cultural diffusion all over the world.(06C)15. linguistics imperialism: it is a kind of kind of linguicism which can be defined as the promulgation of global ideologies through the world-wide expansion of one language. (06C)16. linguistic nationalism: In order to protect the purity of their language, some countries have adoptedspecial language policy. It is called linguistic nationalism.17. intercultural communication: It is communication between people whose cultural perceptions and symbols are distinct enough to alter the communication event. 18. language planning: planning, usually by a government, concerning choice of national or official language(s), ways of spreading the use of a language, spelling reforms, the addition of new words to the language, and other language problems.Chapter 8: Language And Society1. sociolinguistics: The subfield of linguistics that study language variation and language use in social contexts.2. speech community: A group of people who form a community and share at least one speech variety as well as similar linguistic norms. (05)3. speech varieties: It refers to any distinguishable form of speech used by a speaker or a group of speakers.4. regional dialect: A variety of language used by people living in the same geographical region.5. sociolect: A variety of language used by people, who belong to a particular social class.6. registers : The type of language which is selected as appropriate to the type of situation.7. idiolect : A person’s dialect of an individual speaker that combines elements, regarding regional, social, gender and age variations. (04)8. linguistic reportoire : The totality of linguistic varieties possessed by an individual constitutes his linguistic repertoire.9. register theory : A theory proposed by American linguist Halliday, who believed that three social variables determine the register, namely, field of discourse, tenor of discourse and mode of discourse. 10. field of discourse : the purpose and subject matter of the communicative behavior..11. tenor of discourse: It refers to the role of relationship in the situation in question: who the participants in the communication groups are and in what relationship they stand to each other.12. mode of discourse: It refers to the means of communication and it is concerned with how communication is carried out.13. standard dialect: A superposed variety of language of a community or nation, usually based on the speech and writing of educated native speakers of the language.14. formality: It refers to the degree of formality in different occasions and reflects the relationship andconversations. According to Martin Joos, there are five stages of formality, namely, intimate, casual, consultative, formal and frozen.15. Pidgin: A blending of several language, developing as a contact language of people, who speak different languages, try to communication with one another on a regular basis.16. Creole : A pidgin language which has become the native language of a group of speakers used in this daily life.17. bilingualism : The use of two different languages side by side with each having a different role to play, and language switching occurs when the situation changes.(07C)18. diaglossia : A sociolinguistic situation in which two different varieties of language co-exist in a speech community, each having a definite role to play. 19. Lingua Franca : A variety of language that serves as a medium of communication among groups of people, who speak different native languages or dialects20. code-switching: the movement back and forth between two languages or dialects within the same sentence or discourse. (04)1. historical linguistics: A subfield of linguistics that study language change.2. coinage: A new word can be coined to fit some purpose. (03)3. blending: A blend is a word formed by combining parts of other words.4. clipping: Clipping refers to the abbreviation of longer words or phrases.5. borrowing: When different culture come into contact, words are often borrowed from one language to another. It is also called load words.6. back formation: New words may be coined from already existing words by subtracting an affix mistakenly thought to be part of the old word. Such words are called back-formation.7. functional shift: Words may shift from one part of speech to another without the addition of affixes.8. acronyms: Acronyms are words derived from theinitials of several words.9. protolanguage: The original form of a language family, which has ceased to exist.10. Language family: A group of historically related languages that have developed from a common ancestral language.Chapter 6: Pragmatics1. pragmatics: The study of how speakers uses sentences to effect successful communication.2. context: The general knowledge shared by the speakers and the hearers. (05)3. sentence meaning: The meaning of a self-contained unit with abstract and de-contextualized features.4. utterance meaning: The meaning that a speaker conveys by using a particular utterance in a particular context. (03)5. utterance: expression produced in a particular context with a particular intention.6. Speech Act Theory: The theory proposed by John Austin and deepened by Searle, which believes that we are performing actions when we are speaking. (05)7. constatives: Constatives are statements that either state or describe, and are thus verifiable. (06F)8. performatives: Performatives are sentences that don’t state a fact or describe a state, and ar e not verifiable.9. locutionary act: The act of conveying literal meaning by virtue of syntax, lexicon and phonology.10. illocutionary act: The act of expressing the speaker’s intention and performed in saying something. (06F)11. perlocutionary act: The act resulting from saying something and the consequence or the change brought about by the utterance.12. representatives: Stating or describing, saying what the speaker believes to be true.13. directives: Trying to get the hearer to do something.14. commisives: Committing the speaker himself to some future course of action.15. expressives: Expressing feelings or attitude towards an existing state.16. declaration: Bring about immediate changes by saying something.17. cooperative Principle: The principle that the participants must first of all be willing to cooperate in making conversation, otherwise, it would be impossible to carry on the talk.18. conversational implicature:The use of conversational maxims to imply meaning during conversation.19. formality: formality refers to the degree of how formal the words are used to express the same purpose. Martin Joos proposed five stages of formality, namely, intimate, casual, consultative, cold, and frozen. (06F)Chapter 5: Semantics1. semantics: Semantics can be simply defined as the study of meaning.2. Semantic triangle: It is suggested by Odgen and Richards, which says that the meaning of a word is not directly linked between a linguistic form and theobject in the real world, but through the mediation of concept of the mind.3. sense : Sense is concerned with the inherent meaning of the linguistic form. It is the collection of all the features of the linguistic form. It is abstract and de-contexturalized. It is the aspect of meaning dictionary compilers are interested in.4. reference : Reference means what a linguistic form refers to in the real, physical world. It deals with the relationship between the linguistic element and the non-linguistic world of experience.5. synonymy: Synonymy refers to the sameness or close similarity of meaning. Words that are close in meaning are called synonyms.6. dialectal synonyms: synonyms that are used in different regional dialects.7. stylistic synonyms: synonyms that differ in style, or degree of formality.8. collocational synonyms: Synonyms that differ intheir colllocation, i.e., in the words they go together with.9. polysemy : The same word has more than one meaning.(05/03)10. homonymy: Homonymy refers to the phenomenon that words having different meanings have the same form,i.e., different words are identical in sound or spelling, or in both. (04)11. homophones: When two words are identical in sound, they are homophones.12. homographs: When two words are identical in spelling, they are homographs.13. complete homonymy: When two words are identical in both sound and spelling, they are complete homonyms. 14. hyponymy: Hyponymy refers to the sense relation between a more general, more inclusive word and a more specific word.15. superordinate: The word which is more general in meaning is called the superordinate.16. co-hyponyms: Hyponyms of the same superordinate are co-hyponyms.17. antonymy: The term antonymy is used for oppositeness of meaning.18. gradable antonyms: Some antonyms are gradable because there are often intermediate forms between thetwo members of a pair. e.g, antonyms old and young, between them there exist middle-aged, mature, elderly. 19. complementary antonyms: a pair of antonyms that the denial of one member of the pair implies the assertion of the other. It is a matter of either one or the other.20. relational opposites: Pairs if words that exhibit the reversal of a relationship between the two items are called relational opposites. For example, husband---wife, father---son, buy---sell, let---rent, above---below.21. entailment: the relationship between two sentences where the truth of one is inferred from the truth of the other. E.g. Cindy killed the dog entails the dog is dead.22. presupposition: What a speaker or writer assumes that the receiver of the massage already knows. e.g. Some tea has already been taken is a presupposition of Take some more tea.23. componential analysis: an approach to analyze the lexical meaning into a set of meaning components or semantic features. For example, boy may be shown as[+human] [+male] [-adult].24. predication analysis: a way, proposed by British linguist G. Leech, to analyze sentence meaning.25. predication: In the framework of predication analysis, the basic units is called predication, which is the abstraction of the meaning of a sentence.26. predicate: A predicate is something said about an argument or it states the logical relation linking the arguments in a sentence.27. argument: An argument is a logical participant in a predication, largely identical with the nominalelement(s) in a sentence.28. selectional restriction: Whether a sentence is semantically meaningful is governed by the rules called selectional restrictions, i.e. constraints on what lexical items can go with what others.29. semantic features: The smallest units of meaning ina word, which may be described as a combination of semantic components. For example, woman has the semantic features [+human] [-male] [+adult]. (04)30. presequence: The specific turn that has thefunction of prefiguring the coming action. (05)Chapter 4: Syntax1. syntax: A branch of linguistics that studies how words are combined to form sentences and the rules that govern the formation of sentences.2. category: It refers to a group of linguistic items which fulfill the same or similar functions in aparticular language such as a sentence, a noun phrase or a verb.3. syntactic categories: Words can be grouped together into a relatively small number of classes, called syntactic categories.4. major lexical category: one type of word level categories, which often assumed to be the heads around which phrases are built, including N, V, Adj, and Prep.5. minor lexical category: one type of word level categories, which helps or modifies major lexical category.6. phrase: syntactic units that are built around a certain word category are called phrase, the categoryof which is determined by the word category around which the phrase is built.7. phrase category: the phrase that is formed by combining with words of different categories. In English syntactic analysis, four phrasal categories are commonly recognized and discussed, namely, NP, VP, PP, AP.8. head: The word round which phrase is formed is termed head.9. specifier: The words on the left side of the heads are said to function as specifiers.10. complement: The words on the right side of the heads are complements.11. phrase structure rule:The special type of grammatical mechanism that regulates the arrangement of elements that make up a phrase is called a phrase structure rule.12. XP rule: In all phrases, the specifier is attached at the top level to the left of the head while the complement is attached to the right. These similarities can be summarized as an XP rule, in which X stands for the head N,V,A or P.13. X^ theory: A theoretical concept in transformational grammar which restricts the form of context-free phrases structure rules.14. coordination: Some structures are formed by joining two or more elements of the same type with the help of a conjunction such as and or or. Such phenomenon is known as coordination.15. subcategorization:The information about a word’s complement is included in the head and termed suncategorization. (07C)16. complementizer: Words which introduce the sentence complement are termed complementizer.17. complement clause: The sentence introduced by the complementizer is called a complement clause.18. complement phrase: the elements, including a complementizer and a complement clause is called a complement phrase.19. matrix clause: the contrusction in which the complement phrase is embedded is called matrix clause. 20. modifier: the element, which specifies optionally expressible properties of heads is called modifier.21. transformation : a special type of rule that can move an element from one position to another.22. inversion : the process of transformation that moves the auxiliary from the Infl position to aposition to the left of the subject, is called inversion.23. Do insertion : In the process of forming yes-no question that does not contain an overt Infl, interrogative do is inserted into an empty Infl positon to make transformation work.24. deep structure : A level of abstract syntactic representation formed by the XP rule.25. surface structure : A level of syntactic representation after applying the necessary syntactic movement, i.e., transformation, to the deep structure. (05)26. Wh question : In English, the kind of questions beginning with a wh- word are called wh question.27. Wh movement :The transformation that will move wh phrase from its position in deep structure to aposition at the beginning of the sentence. This transformation is called wh movement.28. moveα: a general rule for all the movement rules, where ‘alpha‘ is a cover term foe any element thatcan be moved from one place to another.29. universal grammar: the innateness principles and properties that pertain to the grammars of all human languages.1. morphology: A branch of linguistics that studies the internal structure of words and rules for word formation.2. open class: A group of words, which contains an unlimited number of items, and new words can be addedto it.3. closed class: A relatively few words, including conjunctions, prepositions and pronouns, and new words are not usually added to them.4. morpheme: The smallest unit of meaning of a language. It can not be divided without altering or destroyingits meaning.。

1.3考研真题与典型题详解I. Fill in the blanks. 1. The features that define our human languages can be called ______ features. (北二外2006研)2. Linguistics is usually defined as the ______study of language. (北二外2003研)3. Language, broadly speaking, is a means of______ communication.4. In any language words can be used in new ways to mean new things and can be combined into innumerable sentences ba sed on limited rules. This feature is usually termed______5. Linguistics is the scientific study of______.6. Modern linguistic is______ in the sense that the linguist tries to discover what language is rather than lay down some rul es for people to observe.7. One general principle of linguistic analysis is the primacy of ______ over writing.8. The branch of linguistics which studies the sound patterns of a language is called ______. (北二外2003研)9. The branch of grammar which studies the internal structure of words is called______. (北二外2004研)10. ______mainly studies the characteristics of speech sounds and provides methods for their description, classification and transcription. (北二外2005研)11. Semantics and ______investigate different aspects of linguistic meaning. (北二外2007研)12. In linguistics, ______ refers to the study of the rules governing the way words are combined to form sentences in a lang uage, or simply, the study of the formation as sentence. (中山大学2008研)13. ______can be defined as the study of language in use. Sociolinguistics, on the other hand, attempts to show the relations hip between language and society.14. The branch of grammar which studies the internal structure of sentence is called _______. (北二外2008研)15. Saussure distinguished the linguistic competence of the speaker and the actual phenomena or data of linguistics (utteran ces) as and . The former refers to the abstract linguisticlinguistic system shared by all the members of a speech community, and the latter is the concrete manifestation of language either through speech or through writing. (人大2006研)16. The description of a language as it changes through time is a ______ study.17. Linguistic potential is similar to Saussure’s langue and Cho msky’s______.18. One of the important distinctions in linguistics is ______ and parole. The former is the French word for “language”, whi ch is the abstract knowledge necessary for speaking,listening,writing and reading. The latter is concerned about the actual use of language by people in speech or writing. Parole is more variable and may change according to contextual factors.19. One of the important distinctions in linguistics is and performance. (人大2006研)20. Chomsky initiated the distinction between ______ and performances. (北二外2007研)II. Multiple Choice1.Which of the following is NOT a frequently discussed design feature? (大连外国语学院2008研)A. ArbitrarinessB. ConventionC. Duality2.Which of the following words is entirely arbitrary? (西安交大2008研)A. treeB. crashC. typewriterD. bang3. A linguist regards the changes in language and languages use as______.A. unnaturalB. something to be fearedC. naturalD. abnormal4. Which of the following property of language enables language users to overcome the barriers caused by time and place, d ue to this feature of language, speakers of a language are free to talk about anything in any situation? A. Transferability.B. Duality.C. Displacement.D. Arbitrariness:5. The study of physical properties of the sounds produced in speech is closely connected with______. (大连外国语学院2008研)A. articulatory phoneticsB. acoustic phoneticsC. auditory phonetics6. Which of the following statements is true of Jacobson’s framework of language functions?A. The referential function is to indulge in language for its own sake.B. The emotive function is to convey message and inf ormation.C. The conative function is to clear up intentions, words and meanings.D. The phatic function is to establish communion w ith others.7.Which of the following is a main branch of linguistics? (大连外国语学院2008研)A. MacrolinguisticsB. PsycholinguisticsC. Sociolinguistics8. ______ refers to the system of a language, i. e. the arrangement of sounds and words which speakers of a language have a shared knowledge of. (西安外国语学院2006研)A. LangueB. CompetenceC. Communicative competenceD. Linguistic potential9.The study of language at one point in time is a _______ study. (北二外2010研)A. historicalB. synchronicC. descriptiveD. diachronic10. “An refer to Confucius even though he was dead 2,000 years ago. ” This shows that language has the design feature of _ ____.A. arbitrarinessB. creativityC. dualityD. displacement11. The function of the sentence “Water boils at 100 degree Centigrade” is .A. interrogativeB. directiveC. informativeD. performative 12.Saussure is closely connected with______. (大连外国语学院2008研) A. Langue B. Competence C. EticIII. True or False1. Onomatopoeic words can show the arbitrary nature of language. (清华2000研)2. Competence and performance refer respectively to a language user’s underlying knowledge about the system of rules and the actual use of language in concrete situations.3. Language is a means of verbal communication. Therefore, the communication way used by the deaf-mute is not language4. Arbitrariness of language makes it potentially creative, and conventionality of language makes a language be passed from generation to generation. As a foreign language learner, the latter is mere important for us.5. The features that define our human languages can be called DESIGN FEATURES. (大连外国语学院2008研)6. By diachronic study we mean to study the changes and development of language.7. Langue is relatively stable and systematic while parole is subject to personal and situational constraints.8. Language change is universal, ongoing and arbitrary.9. In language classrooms nowadays the grammar taught to students is basically descriptive, and more attention is paid to the developing learners’ communicative skills.10. Language is a system of arbitrary, written signs which permit all the people in a given culture, or other people who have learned the system of that culture, to communicate or interact.11. Saussure’s exposition of synchronic analysis led to the school of historical linguistics.12. Applied linguistics is the application of linguistic principles and theories to language teaching and learning.13. Wherever humans exist, language exists. (对外经贸2006研)14. Historical linguistics equals to the study of synchronic study.15. Duality is one of the characteristics of human language. It refers to the fact that language has two levels of structures: the system of sounds and the system of meanings.16. Prescriptive linguistics is more popular than descriptive linguistics, because it can tell us how to speak correct language. IV. Explain the following terms.1.Duality (北二外2010研;南开大学2010研)2.Design featurespetence4.Displacement (南开大学2010研;清华2001研)5.Diachronic linguistics6. Descriptive linguistics7.Arbitrariness(四川大学2006研)V. Short answer questions1. Briefly explain what phonetics and phonology are concerned with and what kind of relationships hold between the two. (北外2002研)参考答案及解析I.Fill in the blanks.1.Design (人类语言区别于其他动物交流系统的特点是语言的区别特征,是人类语言特有的特征。

《齐齐哈尔大学学报》(哲学社会科学版)2013年7月Journal of Qiqihar University (Phi&Soc Sci )July 2013收稿日期:2013-03-07作者简介:钟俊(1981-),男,厦门大学外文学院2011级博士研究生,南昌工学院基础教学部讲师。

主要从事语料库语言学、双语词典与翻译研究。

□外语理论与翻译研究弗里斯语言学理论与语料库语言学钟俊1,2张丽2(1.厦门大学外文学院,福建厦门361005;2.南昌工学院基础教学部,江西南昌330108)关键词:弗里斯;语言学理论;语料库语言学摘要:弗里斯是20世纪著名的结构主义语言学家,他提倡语言研究要重视真实的语料,并自建语料库来检验、构建语言学理论。