TLR4 TLR4在人冠脉内皮细胞胞内发挥作用 LBP和sCD14在介导LPS-反应中的作用

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:4.16 MB

- 文档页数:25

冠心病病人外周血sCD14、TLR4表达与冠状动脉粥样硬化斑块稳定性的关系李海龙;林英子【期刊名称】《中西医结合心脑血管病杂志》【年(卷),期】2022(20)6【摘要】目的探讨冠心病病人外周血可溶性白细胞分化抗原14(sCD14)、Toll样受体4(TLR4)表达水平与冠状动脉粥样硬化斑块稳定性的相关性。

方法选取2018年10月—2020年2月我院心血管内科收治的冠心病病人146例(冠心病组),其中,稳定型心绞痛(SAP)38例、不稳定型心绞痛(UAP)55例、急性心肌梗死(AMI)53例;采用Gensini积分评估冠心病病人冠状动脉病变程度。

另选取同期体检健康者146名作为对照组。

采用流式细胞仪检测研究对象外周血TLR4表达水平,酶联免疫吸附法(ELISA)测定血清中sCD14水平。

Pearson相关分析法分析sCD14、TLR4表达水平与Gensini评分相关性。

采用二元Logistic回归分析影响冠心病病人冠状动脉粥样硬化斑块不稳定的因素。

结果与对照组比较,SAP组、AMI组、UAP组sCD14、TLR4表达水平均升高(P<0.05);与SAP组比较,AMI组、UAP组Gensini评分、外周血sCD14、TLR4表达水平均升高(P<0.05);与UAP组比较,AMI组Gensini评分升高(P<0.05)。

与硬斑块组比较,软斑块组、混合型斑块组sCD14、TLR4表达水平升高(P<0.05);与混合型斑块组比较,软斑块组sCD14、TLR4表达水平升高(P<0.05)。

sCD14、TLR4表达水平均与Gensini评分呈正相关(P<0.05)。

Logistic回归分析显示,高水平TLR4、高水平sCD14、高Gensini 评分是冠心病病人冠状动脉粥样硬化斑块不稳定的危险因素(P<0.05)。

结论冠心病病人外周血TLR4表达水平及血清sCD14水平明显升高,与冠状动脉粥样硬化斑块不稳定有密切关系,且TLR4和sCD14与冠状动脉病变严重程度存在相关性。

TLR4激动上调内皮细胞氧化低密度脂蛋白受体LOX-1表达王虹艳;曲鹏;富晶;姜华【期刊名称】《高血压杂志》【年(卷),期】2005(13)7【摘要】目的近年研究表明介导先天免疫反应的受体Toll样受体4(TLR4)参与了动脉硬化的发生发展。

业已证明氧化低密度脂蛋白受体LOX1介导内皮细胞活化和功能失调,激发炎症过程,在动脉粥样硬化的发生和发展中起着极为重要作用。

本研究观察TLR4激动是否调节内皮细胞LOX1表达。

方法应用脂多糖(LPS)刺激体外培养的人脐静脉内皮细胞(HUVECs)24h。

采用RTPCR和流式细胞术分别检测TLR4、LOX1mRNA和蛋白表达水平。

为了观察转录因子NFκB在调节LOX1表达中的作用,应用NFκB特异性抑制剂咖啡酸苯乙酯(CAPE)预处理细胞,然后以LPS 刺激,检测LOX1mRNA和蛋白变化。

结果LPS(10~1000ng/mL)上调HUVECsTLR4和LOX1mRNA表达,LPS(1000ng/mL)上调TLR4和LOX1蛋白表达,CAPE(20μg/mL)可抑制LPS介导的LOX1表达上调。

结论TLR4/NFκB信号途径可能通过上调内皮细胞LOX1表达参与动脉粥样硬化的发生及发展。

【总页数】5页(P422-426)【关键词】Toll样受体4;脂多糖;人脐静脉内皮细胞;氧化低密度脂蛋白受体;动脉粥样硬化【作者】王虹艳;曲鹏;富晶;姜华【作者单位】大连医科大学附属第二医院心血管内科;大连医科大学附属第二医院实验中心【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R543.5【相关文献】1.氧化型低密度脂蛋白诱导肝窦内皮细胞植物血凝素样氧化型低密度脂蛋白受体1的表达 [J], 刘静;王云芳;牛瑞兰;张琦;权金星;田利民2.Toll样受体4/核因子κB和氧化低密度脂蛋白受体LOX-1对单核内皮细胞黏附的影响 [J], 王虹艳;曲鹏;吕申;刘敏;姜华3.银杏叶提取物对脂多糖介导的血管内皮细胞低密度脂蛋白受体LOX-1表达的影响 [J], 富晶;王虹艳;曲鹏4.氧化低密度脂蛋白促进内皮细胞MMP-9 mRNA、LOX-1 mRNA的表达及LOX-1在其中的作用研究 [J], 祝河忠;申晓彧;陈佳娟;潘庆敏;严洁5.氧化应激和植物凝集素样氧化型低密度脂蛋白受体1在氧化低密度脂蛋白上调内皮细胞自噬水平中的作用 [J], 韩侨;张艳林;尤寿江;刘慧慧;曹勇军;陈锐;刘春风因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

四川大掌博士后研究工作报告中文摘要G一细菌是牙周炎的主要致病菌,内毒素是革兰氏阴性菌外膜的主要成分,是一种公认的重要的牙周致病因子,在牙周炎发病中的作用越来越受到重视。

牙龈成纤维细胞是牙周组织的主要细胞群,作为牙周组织中重要炎症反应细胞,在LPS引起的牙周炎组织病理损害过程中具有重要作用。

近年来的研究表明,成纤维细胞也具有一定的免疫细胞活性,可与内毒素直接作用,可作为免疫辅助细胞参与牙周组织的破坏过程,产生炎症细胞因子,介导炎症反应,参与牙周炎的发生和发展。

LPS受体识别、激活细胞内的信号转导途径等方面一直存在争议。

人牙龈成纤维细胞LPS受体的寻找和鉴定一直是该领域研究的热点课题。

Toll样受体(Toll-likereceptors,TLRs)的发现和研究为该领域带来了新的机遇,TLRs极有可能是LPS的识别受体,将刺激信号传入胞内,在介导LPS的病理生理中具有重要作用。

那么,牙龈成纤维细胞是否表达Toll样受体,如果表达,表达何种Toll样受体,其是否介导了LPS对牙龈成纤维细胞的激活,其特异的信号转导通路及调节机制如何,以及何种转录因子在其中起了重要作用,本实验拟对上述问题进行研究,为进一步研究LPS对牙龈成纤维细胞激活/损伤机理奠定基础,也为揭示LPS的膜信号转导机制和牙周炎的防治提供新思路。

基于以上原因,本论文进行了以下实验:1人牙龈成纤维细胞TLR4编码区cDNA克隆、蛋白表达和多克隆抗体的制各首先我们从人牙龈成纤维细胞中成功地克隆到了人TLR4全部编码区序列,约2.4kb,证实了人牙龈成纤维细胞表达TLR4mRNA:根据TLR4的基因结构和读框,我们采用基因重组的方法成功地构建了原核表达载体pRSETA.TLR4,并通过对T7启动子有较好效果的大肠杆菌BL21进行IPTG诱导表达,结果获得了预计的约90KD的TLR4融合蛋白,并用NiNl’A柱亲和层析进行了初步纯化;纯化的TLR4融合蛋白免疫新西兰大白兔,采用双向免疫扩散试验和ELISA法检测效价的方法证明了所制备的抗体是成功的,为进一步的研究奠定了物质基础。

小剂量脂多糖诱导血管内皮细胞TLR4的表达路玲;常文秀;曹书华;王勇强;高红梅【摘要】Objective To investigate the expression of Toll like receptor4(TLR4)on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) induced by small doses of lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Methods The ECV304 belonging to HUVEC was cultured in vitro, and hatched with LPS and LPS + antibody of TLR4(anti-TLR4) respectively. Cell proliferation activity was detected by MTT. The effect of LPS on change of the cell surface of TLR4 was observed with immunohistochemical staining method. The expression of TLR4-mRNA and of IL-8mRNA were evaluated by Fluorescence Detection Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). Results ECV304 cells stimulated by LPS of(10-50)ng/mL within 24 h, MTT detection showed no apparent change (P> 0.05); but with 100 ng/mL LPS stimulated the cells 24 h, the number of cells reduced significantly (P <T 0.05), under the circumstances, anti-TLR4 didn't withstand evidently. The 10 ng/mL LPS stimulated ECV304 in 24 h, the expression of TLR4 was elevatory; and with 50 ng/mL LPS stimulation, the expression of TLR4 was significantly increased in 6-24 h (P<0.05), with 50 ng/mL LPS stimulating ECV304 cells in 4 h and 8 h. The expression of TLR4-mRNA in LPS group and LPS+anti-TLR4 group increased significantly as compared with the normal control group (P<0.05), but LPS+anti-TLR4 group only in 8 h lower than LPS group;the expression of IL-8mRNA in LPS group and LPS+anti-TLR4 evaluated obviously as compared with the normal control group only in 8h, which did not affect with anti-TLR4. Conclusion Small doses of LPS can induce ECV304 cells expressing TLR4 and cause cell activation, and anti-TLR4 can inhibit TLR4 expression, but can't restrain cell activation.%目的:观察小剂量脂多糖(LPS)对人脐静脉内皮细胞(ECV304)TOLL样受体4(TLR4)表达的影响.方法:体外培养ECV304细胞,分别与LPS及LPS+TLR4抗体进行孵育.MTT法检测细胞的增殖活性,免疫组化染色法检测细胞表面TLR4的表达,实时荧光定量聚合酶链反应(RT-PCR)检测细胞核核内TLR4-mRNA及IL-8mRNA的表达.结果:LPS(10~50 ng/mL)刺激ECV304细胞24 h内,细胞增殖活性无明显变化(P >0.05);而以100 ng/mL 刺激24 h后,细胞增殖活性明显降低(P< 0.05),TLR4抗体对此无明显拮抗作用.LPS能明显上调ECV304表达TLR4、TLR4-mRNA及IL-8mRNA,其中10 ng/mL的LPS在24 h时、50 ng/mL LPS在6~24 h时,TLR4表达具有统计学意义(P< 0.05);50 ng/mL的LPS刺激ECV304细胞在4 h及8 h 时,细胞核内TLR4mRNA 表达均明显升高(P < 0.05),而IL-8mRNA 表达在8 h 时明显升高(P < 0.05).TLR4 抗体对ECV304表达TLR4及TLR4-mRNA有拮抗作用(P< 0.05),对IL-8mRNA表达无明显拮抗作用(P> 0.05).结论:小剂量LPS可诱导ECV304细胞表达TLR4并引起细胞活化,TLR4抗体可抑制TLR4的表达,但不能抑制细胞的活化.【期刊名称】《中国中西医结合外科杂志》【年(卷),期】2012(018)001【总页数】5页(P47-51)【关键词】脂多糖;血管内皮细胞;TOLL样受体4【作者】路玲;常文秀;曹书华;王勇强;高红梅【作者单位】天津医科大学第一中心临床学院ICU,天津300192;天津医科大学第一中心临床学院ICU,天津300192;天津医科大学第一中心临床学院ICU,天津300192;天津医科大学第一中心临床学院ICU,天津300192;天津医科大学第一中心临床学院ICU,天津300192【正文语种】中文【中图分类】Q95-33脂多糖(Lipopolysaccharide,LPS)是革兰阴性菌细胞壁的主要成分与毒力因子,可使内皮细胞活化,促使炎症介质、酶等释放,作用于凝血、纤溶系统,促发弥漫性血管内凝血。

CD14与肿瘤的相互关系及研究进展李康【摘要】CD14为白细胞表面分化抗原,在介导机体免疫应答及炎性反应中具有重要作用.近年来研究发现CD14的基因多态性能够影响多种肿瘤的易患性,同时其免疫调节功能与肿瘤的发生、发展密切相关,但其详细的作用机制仍未明确.该文针对CD14多态性与肿瘤、CD14与肿瘤免疫逃逸、CD14与肿瘤发生、发展的关系研究现状展开综述,期望为CD14在抗肿瘤中的作用研究提供理论支持.【期刊名称】《医学综述》【年(卷),期】2014(020)015【总页数】3页(P2726-2728)【关键词】CD14;肿瘤;基因多态性;免疫逃逸【作者】李康【作者单位】西藏自治区人民医院消化内科,拉萨850000【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R34分化抗原群(cluster of differentiation antigen 14,CD14)为细胞表面糖蛋白家族成员之一,最初被发现为白细胞表面分化抗原,是单核细胞、中性粒细胞和巨噬细胞的特异性表面标志物[1]。

哺乳细胞中CD14为革兰染色阴性菌脂多糖(lipopolysaccharide,LPS)的高亲和受体,能够参与机体对革兰染色阴性菌的吞噬与消化,在介导机体的免疫应答以及炎性反应中均发挥着重要作用[2-3]。

近年来,多项研究指出CD14的基因多态性与肿瘤的易患性密切相关。

随着研究的深入,CD14与肿瘤免疫逃逸以及肿瘤发生、发展的关系也逐渐受到关注。

基于CD14对免疫应答及细胞因子的调控作用,深入探讨CD14的功能及作用机制对于抗肿瘤研究具有非常重要的意义。

1 CD14的结构人CD14基因位于第5号染色体长臂5q23~31区,长约3900 bp,包含2个外显子和较长的5′端以及3′端非编码序列。

CD14蛋白包含375个氨基酸残基,其成熟肽长356个氨基酸,其中包含19个氨基酸长度的信号肽,4个N型糖链黏部位,约占整个相对分子质量的20%。

此外,CD14的氨基酸序列中还包含一个重复10次的富含亮氨酸的特异性序列,可能与CD14分子的膜结合以及与其他蛋白质的结合有关。

TLR4在冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病患者单个核细胞炎性反应中的作用黄俊;何隆淼;杨琴;陈云肖【期刊名称】《中国急救医学》【年(卷),期】2016(036)008【摘要】目的探讨冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病患者外周血单个核细胞Toll样受体4(Toll-like receptor 4,TLR4)介导的炎性反应及在急性冠状动脉事件中的作用.方法连续入选研究对象,取外周血分离单个核细胞,予以脂多糖(LPS)和(或)阿托伐他汀处理.流式细胞仪检测细胞TLR4表达,ELISA法检测肿瘤坏死因子(TNF)-α、白细胞介素(IL)-6、IL-1、IL-10水平.结果急性冠状动脉综合征(ACS)组单个核细胞TLR4及TNF-α、IL-6、IL-1明显高于稳定型心绞痛(SAP)组、冠状动脉慢血流(CSF)组及健康对照(HC)组,而IL-10低于其他各组(P<0.05).LPS刺激后,与HC组比较,SAP组、CSF组TLR4及TNF-α、IL-6、IL-1明显高于原有水平,IL-10低于原有水平(P<0.05),而阿托伐他汀干预能抑制这一现象.阿托伐他汀干预ACS组可致TLR4和TNF-α、IL-6、IL-1水平下降,IL-10水平上升(P<0.05).结论 TLR4过度表达及其炎症反应可能与ACS的发生密切相关.LPS能激活SAP患者、CSF患者单个核细胞TLR4,介导炎性反应.阿托伐他汀能抑制TLR4的过度表达及其炎性反应.【总页数】4页(P703-706)【作者】黄俊;何隆淼;杨琴;陈云肖【作者单位】330006 江西南昌,南昌大学第一附属医院心内科;330006 江西南昌,南昌大学第一附属医院心内科;330006 江西南昌,南昌大学第一附属医院心内科;330006 江西南昌,南昌大学第一附属医院心内科【正文语种】中文【相关文献】1.外周血单个核细胞TLR4的表达在慢性乙型重型肝炎患者中的意义2.右美托咪定对脂多糖诱导的子宫内膜炎小鼠子宫组织中TLR4-NF-κB/NLRP3炎性小体介导的炎性反应的影响3.优质护理在呼出气一氧化氮测定哮喘患者气道炎性反应评估中的作用研究4.优质护理在呼出气一氧化氮测定哮喘患者气道炎性反应评估中的作用研究5.慢性心力衰竭患者外周血单个核细胞miR-590表达与左心室重构和炎性反应的关系因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

TLR4与N-HDL-C在冠心病中的表达及辛伐他汀的干预机制一、TLR4在冠心病中的表达TLR4是Toll样受体家族的一员,是一种重要的免疫受体,可识别和结合细菌脂多糖,引发炎症反应。

研究表明,TLR4在冠心病中的表达水平明显升高,并且与冠心病的发展和进展密切相关。

具体来说,TLR4的高表达能够激活NF-κB信号通路,导致炎症介质的释放增加,进而引发动脉粥样硬化斑块形成以及血管炎症反应的加剧,从而增加冠心病的风险。

研究发现TLR4的激活还可以诱导内皮细胞的黏附分子表达增加,进而促进白细胞的黏附和血管内皮损伤。

TLR4在冠心病的病理生理过程中起着举足轻重的作用。

二、N-HDL-C在冠心病中的作用高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(HDL)被认为是一种“良好”的胆固醇,其具有抗氧化、抗炎和反粘附等多种保护心脏疾病的作用。

N-HDL-C是指对HDL-C进行了修饰的一种脂蛋白,其具有更强的抗氧化和抗炎能力。

研究表明,N-HDL-C的水平与冠心病的发生和发展密切相关。

N-HDL-C水平降低会导致氧化应激和炎症反应的增加,从而加速动脉粥样硬化的发展。

N-HDL-C还可以促进胆固醇从动脉壁中回收到肝脏,从而减少胆固醇在动脉中的沉积,减轻动脉粥样硬化的程度。

N-HDL-C在冠心病的发病机制中扮演着重要的保护作用。

三、辛伐他汀的干预机制辛伐他汀是一种常用的降脂药物,其主要作用是通过抑制HMG-CoA还原酶,降低胆固醇的合成,从而起到降脂的效果。

辛伐他汀还具有多种其他保护心脏的作用。

研究表明,辛伐他汀可以通过抑制TLR4的激活,减少炎症介质的释放,从而减轻血管炎症反应。

辛伐他汀还可以增加N-HDL-C的水平,通过其抗氧化和抗炎作用保护血管内皮功能,减少动脉粥样硬化斑块的形成。

辛伐他汀还可以通过提高内皮细胞NO的合成,扩张血管,减少心血管事件的发生。

辛伐他汀通过降低胆固醇合成和提高HDL-C水平,从而起到保护血管和心脏的作用。

辛伐他汀还可以通过抑制TLR4的激活和增加N-HDL-C的水平,进一步减轻血管炎症反应,从而减少冠心病的发生和发展。

TLR4、CD14在干燥综合征发病中的作用及其机制研究的

开题报告

第一部分:研究背景与意义

干燥综合征是一种常见的自身免疫疾病,其发病机制至今不明确。

临床上常见的症状包括口干、眼干、皮肤干燥等表现。

干燥综合征患者的唾液腺和泪腺等分泌腺体积缩小、腺泡变形,导致分泌液体量和质量下降。

在免疫学方面,干燥综合征是具有自身免疫性质,T细胞介导的体液免疫和细胞免疫功能异常。

尽管许多研究聚焦在免疫失调上,但在干燥综合征中,TLR4、CD14的角色尚未完全认识。

因此,本研究旨在探讨TLR4、CD14在干燥综合征患者中的表达及其参与发病机制的作用,以期为干燥综合征的治疗提供科学依据。

第二部分:研究内容及方法

研究目的:研究TLR4、CD14在干燥综合征发病中的作用及其机制

研究方法:

1.研究对象选择:40例干燥综合征患者和30例健康对照者

2.外周血细胞分离,提取外周血单个核细胞 (PBMCs),RNA/DNA分离后用qPCR法测定TLR4、CD14 mRNA/P蛋白的表达水平,并用免疫荧光法检测TLR4、CD14蛋白的表达水平

3.患者血清中检测自身抗体、炎症因子水平的变化。

包括其抗核抗体、抗SSA、抗SSB自身抗体、白介素10(IL-10)、肿瘤坏死因子α(TNFα)、白细胞介素6(IL-6)等。

第三部分:预期结果及意义

本研究将详细分析TLR4和CD14在干燥综合征发病机制中的作用,验证它们在干燥综合征中的具有重要作用及免疫生物学意义。

预计的实验结果将有助于深入了解干燥综合征的免疫病理学机制,为干燥综合征的深入研究、诊断及治疗提供新的理论基础。

TLR4信号转导通路中胞外分子之间的相互作用

陈伟;史忠

【期刊名称】《医学综述》

【年(卷),期】2006(012)009

【摘要】细菌脂多糖(LPS)介导的炎症信号主要通过一种跨膜蛋白toll样受体

4(toll-like receptor 4,TLR4)传入胞内,引起一系列相应的细胞效应.近年来对该信

号通路的研究取得了一些新的进展,本文综述了该信号通路中胞外的主要分子LPS、脂多糖结合蛋白(LBP)、CD14、TLR4和髓样分化蛋白-2(MD-2),及其各分子之间

的相互作用.通过这些分子之间的相互作用激活TLR4并触发信号转导.

【总页数】3页(P522-524)

【作者】陈伟;史忠

【作者单位】中国人民解放军第三军医大学新桥医院急救部,重庆,400037;中国人

民解放军第三军医大学新桥医院急救部,重庆,400037

【正文语种】中文

【中图分类】R392.11

【相关文献】

1.酸乳体系中乳酸菌胞外多糖与蛋白相互作用研究进展 [J], 曾令鹤;钱方;姜淑娟;

牟光庆

2.克氏锥虫Tc13家族新成员的分子鉴定及其特性--对Tulahuén细胞株的Tc13

抗原与β1-肾上腺素受体胞外第二环相互作用的描述 [J],

3.中性粒细胞胞外诱捕网形成的分子机制及其在脓毒症中病理作用的研究进展 [J],

郑大勇;张天翼;林源希;李真玉;宗晓龙

4.光谱法在分子之间相互作用研究中的应用 [J], 刘峥;夏之宁

5.表面活性剂在药物制剂中的应用及其与药物分子之间的相互作用 [J], 张晋;刘少杰;郑利强;李干佐

因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

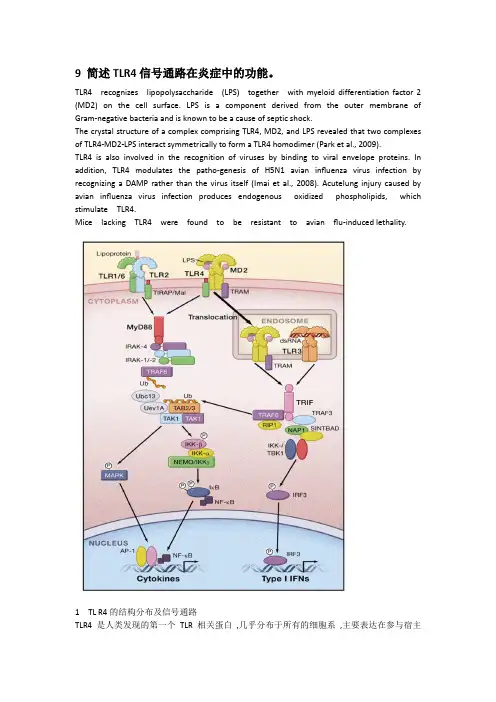

9 简述TLR4信号通路在炎症中的功能。

TLR4 recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS) together with myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD2) on the cell surface. LPS is a component derived from the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria and is known to be a cause of septic shock.The crystal structure of a complex comprising TLR4, MD2, and LPS revealed that two complexes of TLR4-MD2-LPS interact symmetrically to form a TLR4 homodimer (Park et al., 2009).TLR4 is also involved in the recognition of viruses by binding to viral envelope proteins. In addition, TLR4 modulates the patho-genesis of H5N1 avian influenza virus infection by recognizing a DAMP rather than the virus itself (Imai et al., 2008). Acutelung injury caused by avian influenza virus infection produces endogenous oxidized phospholipids, which stimulate TLR4.Mice lacking TLR4 were found to be resistant to avian flu-induced lethality.1TL R4的结构分布及信号通路TLR4是人类发现的第一个TLR 相关蛋白,几乎分布于所有的细胞系,主要表达在参与宿主防御功能的细胞上,如单核巨噬细胞、粒细胞、树突状细胞、淋巴细胞、内皮细胞和上皮细胞,以骨髓单核细胞的表达尤其多[ 5 ],近年来发现,肾小管上皮细胞、心脏、呼吸道上皮细胞和肠上皮细胞也均表达TLR4[ 6 ] 。

LPS (TLR4激活剂)产品编号产品名称包装(TLR4激活剂) 0.5mg S1732 LPS产品简介:¾LPS即lipopolysaccharide,本产品是从E. coli O111: B4中纯化获得的脂多糖。

LPS是绝大多数革兰氏阴性菌细胞壁的主要成分,有很强的免疫原性,可以增强免疫反应。

LPS主要通过TLR4(Toll-like receptor 4)发挥作用。

LPS可以和脂多糖结合蛋白(lipopolysaccharide binding protein, LBP)结合,随后和CD14结合,并和TLR4和MD2形成复合物。

该复合物形成后,可以通过MyD88途径诱导炎性细胞因子的产生。

LPS的信号途径也可以是不依赖于MyD88的。

有报道表明LPS也可以直接和TLR4相结合。

不同来源的LPS的性状有所不同,通常从大肠杆菌来源的LPS可以激活TLR4从而引起炎症反应,而从P.gingivalis来源的LPS可以激活TLR2从而引起炎症反应。

本产品为大肠杆菌(E. coli O111: B4)来源的LPS。

¾LPS可以激活NF-κB,从而促进后续的炎症因子的转录和表达。

LPS因此也常用作NF-κB的激活剂。

另外,LPS在肝细胞中可以上调iNOS的水平。

¾从E. coli O111: B4中纯化获得的LPS是目前应用最广泛的一种LPS。

¾本产品为进口分装,用水配制,浓度为2mg/ml,共0.25ml。

包装清单:产品编号产品名称包装S1732 LPS(TLR4激活剂, 2mg/ml) 0.5mg—说明书1份保存条件:-20℃保存,一年有效。

需避免反复冻融,可以适当分装。

短时间内频繁使用可以4℃保存,半年有效。

注意事项:¾本产品对人体有害,请注意适当防护。

由于LPS有很强的免疫原性,需注意防止LPS被吸入或进入人体的循环系统。

¾为了您的安全和健康,请穿实验服并戴一次性手套操作。

TLR4阻断剂和PDTC对LPS刺激的人牙周韧带细胞的作用研究的开题报告题目:TLR4阻断剂和PDTC对LPS刺激的人牙周韧带细胞的作用研究1. 研究背景及意义人牙周韧带细胞(periodontal ligament cells,PDLs)是牙周组织的重要细胞成分,参与了牙周组织的代谢、修复和重构。

外源性的病原菌感染会引起PDLs的炎症反应,导致牙周疾病的发生和进展,如牙周炎和牙周脓肿等。

LPS是细菌的一种重要成分,可以刺激PDLs分泌炎性因子和细胞因子,从而导致炎症反应。

因此,对于牙周疾病的治疗,炎症反应的控制和调节是非常重要的。

越来越多的研究显示,TLR4和NF-κB通路在PDLs的炎症反应中起着重要作用。

TLR4是一种主要的细胞膜受体,在LPS的识别和信号传递中发挥重要作用,而NF-κB 是炎症反应中的一个关键转录因子。

刺激TLR4会激活NF-κB途径,从而引发炎症反应。

因此,通过阻断TLR4和NF-κB途径可能可以减少PDLs的炎症反应,从而治疗牙周疾病。

本研究旨在探究TLR4阻断剂和PDTC对LPS刺激的PDLs的作用,研究结果可为牙周疾病的治疗提供一定的实验依据。

2. 研究内容及方法(1)细胞培养:采用离体研究的方法,收集人牙周韧带细胞,培养并分组,每组60个细胞。

(2)添加LPS和药物:将PDLs分为四组,分别为LPS组、LPS+TLR4阻断剂组、PDTC组和LPS+TLR4阻断剂+PDTC组。

LPS组为正对照组,仅添加LPS刺激;LPS+TLR4阻断剂组为实验组1,先添加TLR4阻断剂,再添加LPS刺激;PDTC组为实验组2,仅添加PDTC;LPS+TLR4阻断剂+PDTC组为实验组3,先添加TLR4阻断剂和PDTC,再添加LPS刺激。

各组细胞分别加入相应浓度的药物,LPS浓度为10μg/mL,TLR4阻断剂浓度为5μM,PDTC浓度为5μM。

细胞培养时长为24h。

(3)测定指标:收集PDLs培养物,测定细胞的活性、炎性因子IL-1β和TNF-α的表达水平,及TLR4和NF-κB的表达水平。

TLR4介导的信号通路在感染性炎症中的作用作者:刘瑾来源:《中国科技博览》2016年第22期[摘 ;要]Toll样受体4(TLR4)属于模式受体家族,他们是高度保守的受体家族,识别保守病原体相关分模式,因此代表防御的第一道防线。

TLR4被认为是革兰氏阳性细菌脂多糖的识别受体。

此外,它还链接由炎症损伤引起的内源性分子。

因此,TLR4是在感染性刺激介导由外源和内源配体促炎反应引发的一种关键受体。

具有炎症反应放大器的关键作用。

本综述集中于关于TLR4激活在感染性炎症中的作用和TLR4信号传导在一些病理状况中的研究进展。

[关键词]Toll样受体4,感染性炎症中图分类号:TD327.3 文献标识码:A 文章编号:1009-914X(2016)22-0347-011、前言TLR4的首要功能是识别来自病原体的外源分子,特别是革兰氏阳性菌分子。

如LPS[1]。

最近TLR4已经被广泛证明参与识别由受损组织和坏死细胞引起释放的内源性分子。

这些分子称为损伤相关分子模式分子(DAMP),这些分子通过与TLR4相互作用诱导强的促炎反应激活[2]。

这是一个复杂的协同过程,然后诱导恢复组织完整性和功能的解决途径。

然而,在一些情况下,过度或调节不良的炎症反应可能对机体有害。

在几种具有微生物或非微生物病因中,在某些情况下,TLR4激活的参与可以有助于疾病的进展。

2、 TLR4信号通路TLR4由608个残基的细胞外结构域和参与细胞内信号传导级联的187个残基的细胞内结构域组成。

现已证明,T LR4与细胞表面上的骨髓分化2(MD2)物理缔合是配体诱导的活化所必需的[3]。

并通过与LPS的相互作用与TLR4的胞外结构域非共价结合,形成TLR4/MD2受体复合物。

MD2缺乏跨膜和胞内结构域,LPS结合蛋白(LBP)和CD14将LPS单体转移到MD2和TLR4。

LPS结合后,发生两个TLR4 / MD2复合物的二聚化,导致TLR4同二聚体的构象变化,诱导包含Toll /白细胞介素-1受体样(TIR)结构域的衔接蛋白的募集。

Appl12对巨噬细胞LPSTLR4信号通路调控作用的研究的开题报告一、研究背景巨噬细胞是主要的免疫细胞,具有摄取、消化和杀菌等重要功能。

当体内遭受到外界病原菌、细胞碎片、肿瘤细胞等侵袭时,巨噬细胞能够通过识别并摄取这些异物,进而激活免疫反应,起到抵御感染和维护机体健康的作用。

目前已知,巨噬细胞的活化主要与LPS(脂多糖)信号通路有关。

LPSTLR4信号通路即脂多糖结合蛋白(LPS binding protein, LBP)将LPS与CD14结合,再由CD14将复合物转移到TLR4表面上。

激活TLR4后,其结合蛋白MYD88与下游串联反应的一系列蛋白质结合,最终激活NF-κB等关键转录因子,诱导一系列基因的表达和促炎性物质的释放。

近年来,一些研究表明苹果提取物Appl12可以对巨噬细胞LPSTLR4信号通路的激活产生调控作用。

因此,本研究旨在进一步探讨Appl12对巨噬细胞LPSTLR4信号通路调控的作用机制。

二、研究目的1. 确定不同浓度Appl12对巨噬细胞LPSTLR4信号通路的影响程度。

2. 探究Appl12作用的靶点和作用机制。

三、研究方法1. 准备巨噬细胞株,利用MTT法或其他方法评价Appl12对巨噬细胞的毒性。

2. 使用Western blot、实时荧光PCR等方法检测Appl12处理前后各时间点内巨噬细胞中关键转录因子和促炎性因子如NF-κB、IL-6、TNF-α等的表达变化。

3. 利用蛋白质组学手段探寻Appl12作用的分子机制,如鉴定Appl12调节的蛋白质、代谢产物和细胞信号通路等。

四、研究意义本研究将对Appl12对巨噬细胞LPSTLR4信号通路的调控机制进行深入解析,有望揭示其潜在的治疗作用和副作用,为通过药物创新提高巨噬细胞免疫活性提供科学依据。

㊀㊀[摘要]㊀痛风是由于血尿酸浓度升高,尿酸钠晶体在关节㊁肌腱和周围组织中沉积,从而导致炎症性关节炎间歇性发作㊂Toll样受体是先天免疫系统中模式识别受体的一种㊂痛风性关节炎是由于过饱和的尿酸钠晶体在血液中析出,并与巨噬细胞产生作用,导致中性粒细胞的趋化㊁聚集,从而激活TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路,释放IL⁃1β㊁IL⁃6㊁TNF⁃α等炎性因子和蛋白酶,导致痛风性关节炎的发生㊁发展㊂该文以痛风及TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路为主线,综述了TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路与痛风的相关性以及以该信号通路为靶点的治疗方法㊂㊀㊀[关键词]㊀痛风;㊀尿酸钠晶体;㊀炎症;㊀TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路㊀㊀[中图分类号]㊀R363 2+1㊀[文献标识码]㊀A㊀[文章编号]㊀1674-3806(2023)10-1096-04㊀㊀doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-3806.2023.10.23ResearchprogressofTLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κBsignalingpathwayingout㊀BAIDong⁃xue,LIJing,MALi⁃feng.KeyUniversityLaboratoryofEnvironmentandDisease⁃RelatedGeneResearch,XizangMinzuUniversity,Xianyang712082,China㊀㊀[Abstract]㊀Goutiscausedbytheincreaseofblooduricacidconcentrationandthedepositionofsodiumuratecrystalsinjoints,tendonsandsurroundingtissues,whichleadstointermittentattacksofinflammatoryjointdisease.Toll⁃likereceptor(TLR)isoneofthepattern⁃recognitionreceptors(PRRs)intheinnateimmunesystem.Ithasbeenprovedthatgoutyarthritisiscausedbyoversaturatedmonosodiumurate(MSU)crystalsprecipitatinginthebloodandinteractingwithmacrophages,whichleadstothechemotaxisandaggregationofneutrophils,thusactivatingTLR2/TLR4⁃nuclearfactor(NF)⁃κBsignalingpathwayandreleasinginflammatoryfactorssuchasinterleukin(IL)⁃1β,IL⁃6andtumornecrosisfactor⁃α(TNF⁃α),andproteases,leadingtotheoccurrenceanddevelopmentofgoutyarthritis.TakinggoutandTLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κBsignalingpathwayasthemainclue,thispaperreviewsthecorrelationbetweenTLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κBsignalingpathwayandgout,andthetreatmentmethodstargetedbyTLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κBsignalingpathway.㊀㊀[Keywords]㊀Gout;㊀Monosodiumuratecrystals;㊀Inflammation;㊀TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κBsignalingpathway㊀㊀痛风是由于血尿酸浓度升高,尿酸钠(monoso⁃diumurate,MSU)晶体沉积在关节㊁肌腱及其周围软组织中,从而导致炎症性关节炎间歇性发作[1]㊂如不及时治疗,可能导致不可逆的关节损伤㊁慢性炎症及关节畸形㊂除了改变饮食和生活方式外,痛风的药物治疗还包括抗炎和降低尿酸盐的药物㊂该病有显著的性别差异,女性发病率显著低于男性[1]㊂痛风在全世界的发病率呈升高趋势㊂据国外文献统计,痛风患病率为2 7% 6 7%[2],2010 2017年我国痛风患病率约为1 1%[3]㊂痛风急性发作期的一系列临床表现,是由沉积的MSU晶体的先天免疫反应引起的㊂Toll样受体(Toll⁃likereceptors,TLRs)是模式识别受体(pattern⁃recognitionreceptors,PRRs),是先天免疫系统中的一种㊂有研究表明,痛风性关节炎是由于过饱和的MSU晶体在血液中析出,并与巨噬细胞产生作用,诱导中性粒细胞聚集㊁趋化,大量中性粒细胞进入滑膜和关节液,吞噬MSU晶体后引起脱颗粒㊁溶酶体和细胞膜的溶解㊁白细胞募集以及炎症介质的进一步释放,激活TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路,形成了正反馈循环,使炎症级联放大[4]㊂本文以痛风及TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路为主线,综述了TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路与痛风的相关性及以此信号通路为靶点的治疗方法㊂1㊀痛风的发病机制痛风的主要病因包括尿酸的产生增加或排泄减少,产生增加主要是由遗传原因或与嘌呤代谢有关的酶缺陷引起;排泄减少主要与已发现的几种尿酸转运体有关,如尿酸转运体通道㊁尿阴离子交换器和有机阴离子家族成员[5]㊂此外,痛风的发生常与其他疾病相关,如高血压㊁肥胖㊁心血管疾病㊁糖尿病㊁血脂异常㊁慢性肾脏疾病[1]㊂当血清尿酸水平超过一定浓度,尿酸就会析出并形成MSU结晶在关节等部位沉积,从而导致关节周围的炎症反应,最终导致痛风急性发作[6]㊂痛风发病机制主要是两种:一是通过TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路,二是通过调控NOD样受体家族pyrin结构域3(NOD⁃likereceptorfamilypyrindomaincontaining3,NLRP3)炎症小体组装机制㊂MSU晶体是一种损伤相关分子,目前大多研究发现痛风发作可能与MSU晶体沉积关节刺激机体免疫系统而导致的炎症反应密切相关[7]㊂TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路是目前研究较多的㊂此通路调控白介素⁃1β(interleukin⁃1β,IL⁃1β)㊁肿瘤坏死因子⁃α(tumornecrosisfactor⁃α,TNF⁃α)等炎性因子的产生,并在痛风发病过程中起重要作用㊂2㊀TLRs2 1㊀TLRs的定义㊁结构㊁功能㊀TLRs是PRRs家族,在发生感染和细胞损伤的免疫反应中发挥核心作用㊂它们最先在果蝇中被发现,目前TLRs在人类中发现有10种(TLR1 TLR10),小鼠中发现有12种(TLR1 TLR9和TLR11㊁TLR12㊁TLR13)[8]㊂TLRs是一种Ⅰ型跨膜蛋白,其结构由胞外区㊁跨膜区㊁胞浆区三个部分组成㊂胞外区含有富含亮氨酸的重复序列,具有马蹄形结构,可识别各种配体;胞浆区为Toll⁃IL⁃1受体结构域(Toll⁃IL⁃1receptordomain,TIR),可激活下游信号通路[9]㊂TLRs存在于所有先天免疫细胞上,如巨噬细胞㊁中性粒细胞㊁自然杀伤细胞㊁嗜酸性粒细胞和嗜碱性粒细胞等,TLRs能够识别外部病原体上的病原相关分子模式和内部损伤相关分子模式[10]㊂几乎所有生物都编码不同的TLRs,TLR1㊁TLR2㊁TLR4㊁TLR5㊁TLR6㊁TLR11表达于细胞膜上,主要识别脂质㊁脂蛋白等微生物膜成分,如TLR4主要识别脂多糖(lipopo⁃lysaccharide,LPS)并在质膜上转导LPS信号,它检测微生物细胞表面成分;TLR5可识别鞭毛蛋白;TLR1㊁TLR2和TLR6检测细菌脂蛋白;TLR3㊁TLR7㊁TLR8和TLR9位于细胞质中,仅在内质网㊁溶酶体和内溶酶体等细胞内小泡中表达,具有识别微生物核酸,如TLR3特异性检测双链RNA(dsRNA)等核酸,TLR7和TLR8可识别单链RNA;TLR9是含有双链DNA的未甲基化寡核苷酸,而TLR13识别细菌核糖体RNA[11⁃12]㊂TLRs通过与其配体的作用而被激活,产生炎性细胞因子㊁趋化因子等㊂此外,TLRs参与抗原呈递细胞的成熟和分化,从而将先天免疫反应和获得性免疫反应联系起来㊂已报道TLRs基因在免疫组织(如脾㊁胸腺㊁淋巴结)和非免疫组织(骨骼肌㊁脑㊁肺㊁肠和胰腺等)以及所有天然免疫细胞和获得性免疫细胞上表达[13]㊂2 2㊀TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号转导通路㊀TLR2/TLR4在被如CD14㊁LPS和MD2等配体激活后,TLR2/TLR4的细胞质TIR结构域募集信号转导接头的MyD88形成复合物,激活下游各种激酶IRAK4㊁IRAK1,进而导致TNF受体相关因子6(TNFreceptorassociatedfactor6,TRAF6)被募集和激活,激活kappaB抑制因子激酶复合物(inhibitorofkappaBkinase,IKK)α㊁IKKβ㊁IKKγ㊂TLR4还通过非MyD88依赖途径,募集TRAM和TRIF形成复合物,激活TRAF3,进而激活IKKε㊁TANK结合激酶1㊂两者最终导致NF⁃κB被激活,启动前炎性IL⁃1β的表达㊂产生炎症级联反应,生成如TNF⁃α㊁IL⁃1β等细胞炎症因子[14⁃15]㊂3㊀TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号转导通路与痛风的相关性3 1㊀TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号转导通路相关基因的研究㊀在痛风的发病过程中,虽然痛风的许多炎性介质已被识别,但仅有13个等位基因与统计学上有显著的遗传关联[4],其中与TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号转导通路相关的基因主要包括TLR4㊁分化簇14(clusterofdifferentiation14,CD14)㊁IL⁃1β㊁TNF⁃α㊂3 1 1㊀TLR4㊀TLR4是一种PRRs,其基因高度多态,与自身免疫及自身炎症有关㊂TLR4基因rs2149356T>G单核苷酸多态性可能与我国汉族人群原发性痛风发病相关,TT基因型是痛风发病的危险因素,可能参与调节TLR4⁃IL⁃1β信号通路以及免疫㊁炎症㊁脂质代谢[16⁃17]㊂TLR4已被证明在痛风小鼠模型对MSU晶体的炎症反应中是必要因素[18]㊂研究表明,在服用抗TLR4抗体时,血清IL⁃1β在发作期间降低,表明TLR4是未来痛风疗法发展的合理靶点[19]㊂3 1 2㊀CD14㊀CD14是痛风炎症的重要介质TLR2和TLR4的共同受体㊂体外研究表明,sCD14可与MSU晶体结合;CD14阴性细胞仍可吞噬MSU晶体,但产生的炎性细胞因子IL⁃1β减少约90%,有力地支持了CD14在痛风炎症中的作用[20]㊂CD14中功能基因变异的获得增加了TLR4介导的信号对MSU晶体的反应,而功能变异的缺失减少了IL⁃1β的诱导和白细胞的渗透㊂因此,CD14在痛风中可能具有促炎作用[20]㊂但一项研究表明,与健康对照组相比,痛风患者的膜结合CD14和sCD14均减少,将MSU晶体应用于外周血单核细胞CD14的表达也减少[21]㊂这可能表明CD14在痛风的自发缓解中起重要作用㊂3 1 3㊀IL⁃1β㊀IL⁃1β被认为是痛风炎症的中枢,可通过刺激促炎细胞因子㊁趋化因子8和IL⁃6释放以及内皮细胞上黏附分子的上调而加剧痛风相关的炎症,导致中性粒细胞和单核细胞等重新聚集到MSU晶体沉积部位[22],中性粒细胞募集后,炎症的正反馈循环随之而来㊂据报道,MSU晶体存在下的脂肪酸在与TLR2结合后诱导大量IL⁃1β的释放,通过动物模型研究证实了游离脂肪酸和MSU在诱导小鼠IL⁃1β产生和MSU结晶性炎症反应中的协同作用[23]㊂MSU晶体还可以刺激C5a补体蛋白的产生,进而通过产生活性氧和激活炎症小体来刺激IL⁃1β的产生[24]㊂对抑制IL⁃1β作为痛风的治疗进行了几项临床试验㊂Schlesinger等[25]发现,卡那单抗是一种人类抗IL⁃1β的单抗,降低了痛风性关节炎急性发作的风险㊂欧洲药品管理局认为卡那单抗可用于痛风频繁发作且对秋水仙碱㊁非甾体抗炎药㊁口服和注射皮质类固醇有禁忌证的患者[26]㊂对IL⁃1受体拮抗剂阿那白滞素进行了临床研究,结果显示其对急性痛风发作的疗效不逊于通常的治疗方法[27]㊂3 1 4㊀TNF⁃α㊀TNF⁃α是一种被广泛研究的促炎细胞因子,痛风患者血清TNF⁃α升高,MSU晶体刺激单核细胞产生TNF⁃α,TNF⁃α通过其受体促进天冬氨酸蛋白水解酶1的激活,导致NLRP3炎症体的激活,从而导致痛风加重,TNF⁃α还促进pro⁃IL⁃1β的合成,从而产生IL⁃1β[28⁃29]㊂研究表明,rs1800630的A变异与TNF⁃α和血清TNF⁃α水平降低相关[30]㊂这可能表明局部和全身TNF⁃α表达的影响存在重要差异㊂目前已开发出几种TNF⁃α抑制剂㊂可用的拮抗剂包括:依那西普,一种与IgG的Fc部分偶联的重组人TNF⁃R2可溶性融合蛋白;英夫利西单抗,一种抗TNF人鼠嵌合IgG1单克隆抗体;阿达木单抗和戈利木单抗,人抗TNF⁃α单克隆抗体;培塞利珠单抗,人源化抗TNF⁃α抗体的Fabᶄ片段[31]㊂有研究表明,依那西普可能对其他抗炎药无效的痛风性炎症有效[32]㊂有病例报道显示英夫利西单抗成功治疗痛风[33]㊂3 2㊀以TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号转导通路为痛风治疗靶点的研究㊀痛风是人类最常见的自身炎症性关节炎之一,传统的痛风治疗策略药物数量有限,且有许多与之相关的副作用,因此,需要开发更安全㊁有效的药物㊂Holzinger等[34]的一项研究表明,痛风中高表达的骨髓相关蛋白⁃8(myeloid⁃relatedprotein⁃8,MRP⁃8)和MRP⁃14是MSU晶体诱导的体外和体内IL⁃1β分泌的增强剂,这些由活化的吞噬细胞释放的内源性TLR4配体可导致痛风炎症的持续㊂He等[35]的一项研究表明,抑制TLR4可以增强髓系细胞表达的触发受体1抑制剂在MSU晶体诱导的炎症中的作用,而髓系细胞表达的触发受体1可以加速MSU晶体诱导的急性炎症,抑制髓系细胞表达的触发受体1可能为缓解急性痛风性关节炎提供一种新治疗策略㊂另一项研究表明,规律㊁适度的体力活动可以产生可量化的抗炎作用,能够通过降低循环中性粒细胞上的TLR2表达和抑制全身CXCL1来部分减轻由关节内MSU晶体诱导的病理反应[36]㊂Rossato等[18]的一项研究表明,MSU可能激活TLR4以诱导巨噬细胞释放IL⁃1β,在急性痛风发作期间引发伤害感受和炎症㊂Huang等[37]的研究表明,MSU晶体刺激HSP60表达,从而加速TLRs/MyD88/NF⁃κB信号通路并加剧线粒体功能障碍㊂4㊀结语随着痛风患病率的升高,有效的治疗策略变得越来越重要㊂现有研究表明,痛风性关节炎关节内析出的MSU晶体通过TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路,合成前IL⁃1β和其他炎症体成分,此为痛风性关节炎发病的主要途径之一㊂随着对痛风的研究不断深入,痛风发病机制的逐渐明确,痛风性关节炎的治疗新药不断被研究㊂目前,虽已证实TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路在痛风的发病过程中起重要作用,但针对该通路为靶点治疗痛风的药物研究较少,因此,新的治疗靶点的研究有较好前景㊂参考文献[1]DalbethN,MerrimanTR,StampLK.Gout[J].Lancet,2016,388(10055):2039-2052.[2]DalbethN,GoslingAL,GaffoA,etal.Gout[J].Lancet,2021,397(10287):1843-1855.[3]PascartT,LiotéF.Gout:stateoftheartafteradecadeofdevelop⁃ments[J].Rheumatology(Oxford),2019,58(1):27-44.[4]BodofskyS,MerrimanTR,ThomasTJ,etal.Advancesinourunder⁃standingofgoutasanauto⁃inflammatorydisease[J].SeminArthritisRheum,2020,50(5):1089-1100.[5]WangX,WangYG.ProgressintreatmentofgoutusingChineseandWesternmedicine[J].ChinJIntegrMed,2020,26(1):8-13.[6]谢蓓蓓,苏厚恒.MSU晶体介导的痛风性关节炎的炎症机制[J].中华临床医师杂志(电子版),2013,7(16):102-104.[7]蒋㊀莉,周京国,青玉凤,等.Toll样受体2和Toll样受体4及其信号通路在原发性痛风性关节炎发病机制中作用的研究[J].中华风湿病学杂志,2011,15(5):300-304.[8]KawaiT,AkiraS.Toll⁃likereceptorsandtheircrosstalkwithotherinnatereceptorsininfectionandimmunity[J].Immunity,2011,34(5):637-650.[9]LimKH,StaudtLM.Toll⁃likereceptorsignaling[J].ColdSpringHarbPerspectBiol,2013,5(1):a011247.[10]Ghafouri⁃FardS,AbakA,ShooreiH,etal.Interactionbetweennon⁃codingRNAsandToll⁃likereceptors[J].BiomedPharmacother,2021,140:111784.[11]KawaiT,AkiraS.Theroleofpattern⁃recognitionreceptorsininnateimmunity:updateonToll⁃likereceptors[J].NatImmunol,2010,11(5):373-384.[12]FitzgeraldKA,KaganJC.Toll⁃likereceptorsandthecontrolofimmu⁃nity[J].Cell,2020,180(6):1044-1066.[13]V zquez⁃CarballoC,Guerrero⁃HueM,García⁃CaballeroC,etal.Toll⁃likereceptorsinacutekidneyinjury[J].IntJMolSci,2021,22(2):816.[14]LimKH,StaudtLM.Toll⁃likereceptorsignaling[J].ColdSpringHarbPerspectBiol,2013,5(1):a011247.[15]周㊀琦,刘树民,董婉茹. TLR2/4⁃NF⁃κB 信号转导通路在痛风性关节炎发病中的作用机制[J].中国药师,2016,19(9):1733-1736.[16]青玉凤,周京国,张全波,等.Toll样受体4基因单核苷酸多态性与我国汉族人群原发性痛风性关节炎发病的相关性研究[J].中华风湿病学杂志,2013,17(11):724-728.[17]QingYF,ZhouJG,ZhangQB,etal.AssociationofTLR4geners2149356polymorphismwithprimarygoutyarthritisinacase⁃controlstudy[J].PLoSOne,2013,8(5):e64845.[18]RossatoMF,HoffmeisterC,TrevisanG,etal.Monosodiumuratecrystalinterleukin⁃1βreleaseisdependentonToll⁃likereceptor4andtransientreceptorpotentialV1activation[J].Rheumatology(Oxford),2020,59(1):266.[19]QingYF,ZhangQB,ZhouJG,etal.ChangesinToll⁃likereceptor(TLR)4⁃NFκB⁃IL1βsignalinginmalegoutpatientsmightbeinvolvedinthepathogenesisofprimarygoutyarthritis[J].RheumatolInt,2014,34(2):213-220.[20]ScottP,MaH,ViriyakosolS,etal.EngagementofCD14mediatestheinflammatorypotentialofmonosodiumuratecrystals[J].JImmunol,2006,177(9):6370-6378.[21]DuanL,LuoJ,FuQ,etal.DecreasedexpressionofCD14inMSU⁃mediatedinflammationmaybeassociatedwithspontaneousremissionofacutegout[J].JImmunolRes,2019,2019:7143241.[22]HachichaM,NaccachePH,McCollSR.Inflammatorymicrocrys⁃talsdifferentiallyregulatethesecretionofmacrophageinflammatoryprotein1andinterleukin8byhumanneutrophils:apossiblemech⁃anismofneutrophilrecruitmenttositesofinflammationinsynovitis[J].JExpMed,1995,182(6):2019-2025.[23]JoostenLA,NeteaMG,MylonaE,etal.EngagementoffattyacidswithToll⁃likereceptor2drivesinterleukin⁃1βproductionviatheASC/caspase1pathwayinmonosodiumuratemonohydratecrystal⁃inducedgoutyarthritis[J].ArthritisRheum,2010,62(11):3237-3248.[24]KhamenehHJ,HoAW,LaudisiF,etal.C5aregulatesIL⁃1βpro⁃ductionandleukocyterecruitmentinamurinemodelofmonosodiumuratecrystal⁃inducedperitonitis[J].FrontPharmacol,2017,8:10.[25]SchlesingerN,MyslerE,LinHY,etal.Canakinumabreducestheriskofacutegoutyarthritisflaresduringinitiationofallopurinoltreat⁃ment:resultsofadouble⁃blind,randomisedstudy[J].AnnRheumDis,2011,70(7):1264-1271.[26]SoA,DumuscA,NasiS.TheroleofIL⁃1ingout:frombenchtobedside[J].Rheumatology(Oxford),2018,57(suppl_1):i12-i19.[27]JanssenCA,OudeVoshaarMAH,VonkemanHE,etal.Anakinraforthetreatmentofacutegoutflares:arandomized,double⁃blind,placebo⁃controlled,active⁃comparator,non⁃inferioritytrial[J].Rheu⁃matology(Oxford),2019.[Epubaheadofprint][28]AmaralFA,BastosLF,OliveiraTH,etal.TransmembraneTNF⁃αissufficientforarticularinflammationandhypernociceptioninamousemodelofgout[J].EurJImmunol,2016,46(1):204-211.[29]ChapmanPT,YarwoodH,HarrisonAA,etal.Endothelialactiva⁃tioninmonosodiumuratemonohydratecrystal⁃inducedinflammation:invitroandinvivostudiesontherolesoftumornecrosisfactorαandinterleukin⁃1[J].ArthritisRheum,1997,40(5):955-965.[30]SkoogT,vanᶄtHooftFM,KallinB,etal.Acommonfunctionalpolymorphism(CңAsubstitutionatposition⁃863)inthepromoterregionofthetumournecrosisfactor⁃α(TNF⁃α)geneassociatedwithreducedcirculatinglevelsofTNF⁃α[J].HumMolGenet,1999,8(8):1443-1449.[31]SzondyZ,PallaiA.TransmembraneTNF⁃alphareversesignalingleadingtoTGF⁃betaproductionisselectivelyactivatedbyTNFtargetingmole⁃cules:Therapeuticimplications[J].PharmacolRes,2017,115:124-132.[32]TauscheAK,RichterK,GrässlerA,etal.Severegoutyarthritisrefrac⁃torytoanti⁃inflammatorydrugs:treatmentwithanti⁃tumournecrosisfactorαasanewtherapeuticoption[J].AnnRheumDis,2004,63(10):1351-1352.[33]FiehnC,ZeierM.Successfultreatmentofchronictophaceousgoutwithinfliximab(Remicade)[J].RheumatolInt,2006,26(3):274-276.[34]HolzingerD,NippeN,VoglT,etal.Myeloid⁃relatedproteins8and14contributetomonosodiumuratemonohydratecrystal⁃inducedinflam⁃mationingout[J].ArthritisRheumatol,2014,66(5):1327-1339.[35]HeY,YangQ,WangX,etal.Inhibitionoftriggeringreceptorexpressedonmyeloidcell⁃1alleviatesacutegoutyinflammation[J].MediatorsInflamm,2019,2019:5647074.[36]JablonskiK,YoungNA,HenryC,etal.PhysicalactivitypreventsacuteinflammationinagoutmodelbydownregulationofTLR2oncirculatingneutrophilsaswellasinhibitionofserumCXCL1andisassociatedwithdecreasedpainandinflammationingoutpatients[J].PLoSOne,2020,15(10):e0237520.[37]HuangQ,GaoW,MuH,etal.HSP60regulatesmonosodiumuratecrystal⁃inducedinflammationbyactivatingtheTLR4⁃NF⁃κB⁃MyD88signalingpathwayanddisruptingmitochondrialfunction[J].OxidMedCellLongev,2020,2020:8706898.[收稿日期㊀2022-08-10][本文编辑㊀韦㊀颖]本文引用格式白冬雪,李㊀靖,马利锋.TLR2/TLR4⁃NF⁃κB信号通路在痛风中的研究进展[J].中国临床新医学,2023,16(10):1096-1099.。

TLR4在内毒素激活肺泡Ⅱ型上皮细胞过程中的表达及可能作用机制李永旺;张德明;钱桂生;毛宝龄;麻莉【期刊名称】《第三军医大学学报》【年(卷),期】2004(26)10【摘要】目的探讨TLR4(tolllikereceptor 4)在内毒素 (LPS)激活肺泡Ⅱ型上皮细胞(ATⅡcells)中的表达及可能作用机制。

方法通过RT PCR的方法检测TLR4mRNA在ATⅡcells的表达 ;电泳迁移率改变法检测LPS刺激后的ATⅡcellsNF κB活性的变化 ;ELISA检测ATⅡcells培养上清中TNF α和IL 6的含量变化。

结果正常ATⅡcells表达有TLR4mRNA ,LPS刺激后表达增强 ;其表达在 1~ 10 3 ng/mlLPS范围内呈浓度依赖性增强。

LPS刺激后,ATⅡcellsNF κB活性及TNF α和IL 6的生成均呈浓度依赖性的增强。

【总页数】4页(P863-866)【关键词】内毒素;Toll样受体4;急性肺损伤;肺泡Ⅱ型上皮细胞【作者】李永旺;张德明;钱桂生;毛宝龄;麻莉【作者单位】第三军医大学新桥医院全军呼吸内科研究所【正文语种】中文【中图分类】R322.35;R392.11【相关文献】1.MD2在内毒素激活肺泡Ⅱ型上皮细胞中的表达及作用 [J], 李永旺;张德明;钱桂生;毛宝龄2.肝细胞生长因子在内毒素诱导肺泡Ⅱ型上皮细胞损伤中的作用 [J], 马红艳;叶燕青;黄莺;施娟娟3.肿瘤坏死因子在内毒素诱导小鼠肺泡Ⅱ型上皮细胞凋亡中的作用 [J], 宋勇;施毅4.α2A肾上腺素能受体在右美托咪定抑制Ⅱ型肺泡上皮细胞缺氧复氧损伤时TLR4/NF-κB信号通路激活中的作用 [J], 刘培斌;覃卫丹;陈潮金;姚伟锋;谭芳;邓颖青;池信锦;蔡珺5.加味麻杏石甘汤对放射后肺泡Ⅱ型上皮细胞IL-6、TLR2、TLR4表达的影响 [J], 陈珠;钟亚珍;陈帅;林胜友因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

The FASEB Journal express article 10.1096/fj.03-1263fje. Published online May 7, 2004.Toll-like receptor 4 functions intracellularly in human coronary artery endothelial cells: roles of LBP and sCD14 in mediating LPS-responsesStefan Dunzendorfer, Hyun-Ku Lee, Katrin Soldau, and Peter S. TobiasThe Scripps Research Institute, Department of Immunology, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037Corresponding author: Peter S. Tobias, The Scripps Research Institute, Department of Immunology IMM-12, 10550 North Torrey Pines Road, La Jolla, CA 92037. E-mail:tobias@ABSTRACTEndothelial cells are activated by microbial agonists through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to express inflammatory mediators; this is of significance in acute as well as chronic inflammatory states such as septic shock and atherosclerosis, respectively. We investigated mechanisms of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced cell activation in human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAEC) using a combination of FACS, confocal microscopy, RT-PCR, and functional assays. We found that TLR4, in contrast to TLR2, is not only located intracellularly but also functions intracellularly. That being the case, internalization of LPS is required for activation. We further characterized the HCAEC LPS uptake system and found that HCAEC exhibit an effective LPS uptake only in the presence of LPS binding protein (LBP). In addition to its function as a catalyst for LPS-CD14 complex formation, LBP enables HCAEC activation at low LPS concentrations by facilitating the uptake, and therefore delivery, of LPS-CD14 complexes to intracellular TLR4-MD-2. LBP-dependent uptake involves a scavenger receptor pathway. Our findings may be of pathophysiological relevance in the initial response of the organism to infection. Results further suggest that LBP levels, which vary as LBP is an acute phase reactant, could be relevant to initiating inflammatory responses in the vasculature in response to chronic or recurring low LPS. Key words: innate immunity • endothelium • endotoxinEndothelial cells (EC), which form the inner vascular lining, are important in the regulation of vascular tone, coagulation and fibrinolysis, cellular growth, differentiation, and last but not least, immune and inflammatory responses (1, 2). Moreover, these cells are targets for many endogenous and exogenous agents (e.g., lipopolysaccharide [LPS]), that activate the endothelium and result in production of proinflammatory mediators (3). These mechanisms play roles in Gram-negative sepsis, where the body may be overwhelmed with LPS and also in diseases that are linked to a low, but chronic, LPS burden. There is considerable evidence that endotoxin (LPS) contributes to the propagation of atherosclerosis (4, 5), which shares many features with inflammatory diseases (6).LPS is a major component of the outer surface of Gram-negative bacteria and a potent activator of cells of the immune and inflammatory system, including endothelial cells. In vivo, LPS-induced cell activation depends on the presence of at least four proteins: TLR4 (7–9), MD-2 (10), CD14 (11), and LPS binding protein (LBP) (12). The first three may be present as a complex on the surfaces of myeloid (and transfected) cells (13). Many cells, among them epithelial and endothelial cells, do not express the membrane bound form of CD14 (mCD14); their activation involves soluble CD14 (sCD14) (14). LPS·sCD14 complexes will form slowly in vitro (15), but, in vivo, plasma LBP (16–18) catalyzes LPS·CD14 complex formation (19). LPS·CD14 complexes, whether membrane bound or soluble, are necessary for LPS binding to TLR4-MD-2 (20). In mCD14 expressing cells, most LPS appears to be internalized quite independently of activation (21), and mCD14-negative cells also internalize LPS (22, 23). Although LPS internalization by phagocytes has generally been regarded as a disposal function (21), studies have also suggested that internalization might be required for LPS signaling in myeloid lineage cells (24, 25). However, a very recent publication clearly demonstrates that signaling starts on the surface of TLR4-transfected and TLR4 surface expressing cells when incubated with LPS-sCD14 complexes, even in the absence of LPS uptake (26). Other recent work suggests that internalization of LPS is required for activation of murine intestinal epithelial cells, where mCD14, but not TLR4, is found on the surface (27, 28).MATERIALS AND METHODSAntibodiesAnti-TLR4 polyclonal antibody (pAb) H80 and monoclonal antibody (mAb) HTA125 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Monoclonal anti-TLR2 2392 was a gift of Paul Godowski (Genentech), and anti-TLR4 HTA1216, HTA414, and HTA405 were gifts from Kensuke Miyake (Saga Medical School, Japan). Anti-LBP mAb 2B5 and anti-CD14 mAb 28C5 were produced in our laboratory (29). Polyclonal rabbit anti-human MyD88 was from Imgenex (San Diego, CA). The monoclonal mouse anti-human CD14 (clone M5E2), mouse anti-human CD144 (clone 55-7H1), mouse anti-human CD106 (VCAM-1; clone 51-10C9), rat anti-mouse CD31 (PECAM-1) (clone MEC13.3), rat anti-mouse CD144 (VE-cadherin; clone 11D4.1), and rat anti-mouse CD106 (VCAM-1; clone 429-MVCAM.A) used for immunofluorescence staining and PE-conjugated anti-human CD62E (E-selectin/ELAM; clone 68-5H11) were from PharMingen (San Diego, CA). All secondary antibodies used in fluorescence microscopy were Alexa Fluor conjugates (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). PE-conjugated secondary antibodies used in flow cytometry were purchased from PharMingen (San Diego, CA).Proteins, LPS, and other reagentsHuman recombinant sCD14 and LBP were expressed in and purified from BTI-TN-5B1-4 cells (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA) as recently described (23). Both proteins can be radiolabeled at an artificially introduced protein kinase A site. Macrophage-activating lipopeptide-2 (MALP-2) was from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA), recombinant mouse TNF-α was purchased from Serotec (Oxford, UK), and hIL-1β was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Compound 406 was generously provided by Professor S. Kusumoto (Osaka University, Japan). All LPS was purchased from List Biological Laboratories (Campbell, CA). Escherichia coli (O55:B5) LPSwas exclusively used for cell stimulation and tritium-labeled LPS (3H-LPS) from E. coli (K12 LCD25) was used in LPS uptake experiments. For use in fluorescence microscopy, LPS from Salmonella minnesota (Re595) was labeled with FITC (Molecular Probes) (19). Complexes of sCD14 with either LPS were preformed without LBP as described previously (30). Under these conditions, no LPS remains unbound. Complexed LPS (LPS·CD14, FITC-LPS·CD14, 3H-LPS·CD14) was prepared freshly each time and used right away.Cell cultureHCAEC and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were purchased from Clonetics (San Diego, CA) and grown to confluence in full growth medium (EGM-2-MV) from the same company. HCAEC were from healthy young donors and were used for experiments from passages 4–8. There was no obvious difference in TLR2 surface expression or responsiveness to various stimuli between passage 4 and passage 8 cells. Medium was changed every day, and cells were passaged in a 1:3 ratio using trypsin/EDTA (0.025%/0.2 mM).Mouse endothelial cell cultureMouse microvascular and vascular EC were isolated from lung tissue and the aortas of C57/BL6 mice. Halothane-anesthetized animals were killed, and the lungs and the aorta were explanted under sterile conditions, minced, and digested for 1 h at 37°C in 1 mg/ml collagenase type II (Invitrogen). Cells were stained with rat anti-mouse CD31 (10 µg/ml), and goat anti-rat IgG conjugated to paramagnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) enabled further purification using MACS (magnetic cell sorting). Endothelial cells were then cultured and maintained on fibronectin-coated tissue culture plates in mouse brain microvascular growth medium (Cell Application Incorporation, San Diego, CA) supplemented with 15 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Sigma). Purity of the cells was >90% as determined by staining for mouse CD31, mouse CD106, and mouse CD144 and by uptake of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled AcLDL (Molecular Probes).Monocyte isolationHuman peripheral blood monocytes were purified by MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purity of the preparations and viability of the cells regularly exceeded 95% as determined by subsequent FACS analyses using FITC-anti-human CD14 and propidium iodide (2.5 µg/ml). The isolation procedure did not activate the cells and did not diminish their ability to be stimulated.Flow cytometryFor flow cytometry analysis of protein surface expression, HCAEC cultured in six-well plates were harvested with a cell scraper. Freshly prepared monocytes and HCAEC were washed twice and stained with various primary and isotype control antibodies (10 µg/ml) for 30 min at 4°C in PBS/5% FCS containing 0.1% sodium azide. After additional washing steps, cells were incubated with secondary PE-conjugated antibodies for a further 30 min at 4°C, washed and resuspended in PBS, and analyzed on a FACScan (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). HCAEC activation was determined by CD62E surface expression, which was quantified using PE-conjugated mouse anti-human CD62E or control PE-conjugated mouse IgG for 30 min at 4°C before FACS analyses.RT-PCRRNA was purified from LPS-stimulated or unstimulated HCAEC or monocytes using the Absolutely RNA RT-PCR Miniprep Kit from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). mRNA levels of TLR2, TLR4, MD-2, CD14, LBP, and gp96 were determined by RT-PCR. Briefly, the first-strand cDNA was reverse-transcribed from 1 µg total RNA with random primers using the SuperScript first-strand Synthesis System from Invitrogen. The cDNA product was amplified by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 45 s at 55°C, and 2 min extension at 72°C using specific primer pairs. cDNA from monocytes or from stimulated HepG2 cells was used as control for CD14 or LBP, respectively. The RT-PCR products were separated in 1.2% (wt/vol) agarose gels and visualized with ethidium bromide.Immunofluorescence staining and fluorescence microscopyHCAEC were cultured in eight-well Nunc Lab-Tec II chambered coverglasses (Nalge Nunc, Naperville, IL) and after an incubation period of 4 h with either LPS (100 ng/ml), FITC-LPS (100 ng/ml), sCD14 (1.6 µg), LBP (2.5 µg), or preformed FITC-LPS·CD14 complexes (100 ng/ml), cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit from PharMingen (San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 0.5% BSA for 30 min at room temperature, and thereafter the following primary antibodies were added at the indicated concentration for 1 h at room temperature: H80 (20 µg/ml), HTA125 (10 µg/ml), 2B5 (10 µg/ml), anti-hCD14 (10 µg/ml), anti-hCD144 (10 µg/ml), anti-hVCAM-1 (10 µg/ml). Fluorescent wheat germ agglutinin (Oregon Green 488; Molecular Probes) was used for Golgi staining, and fluorescent phallotoxin was used for F-actin staining (both at 5 µg/ml). Cells were washed, and secondary fluorescence-labeled antibodies were added at 5 µg/ml for 1 h at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (300 nM) for 3 min before cells were extensively washed and treated with SlowFade Light antifade reagent (Molecular Probes). Monocytes were stained in suspension. Thereafter, they were mounted to a cover glass with ProLong (Molecular Probes) mounting medium, thus maintaining their round shape. Images were acquired using the DeltaVision Optical Sectioning Microscope (Model 283). Following data acquisition using the Photometrics CH350L liquid-cooled CCD camera, which collects low-intensity signals with a linear response to light intensity, the data are then deconvoluted using DeltaVision software SoftWoRx 2.5 based on the Agard/Sadat inverse matrix algorithm. Following computational deconvolution, this system can provide high-resolution 3D images of cells, but each single optical section can still be viewed alone.Cell stimulation experimentsHCAEC and HUVEC were cultured in six-well plates, and after reaching confluence, EGM-2-MV was changed to DMEM/2% FCS or DMEM/2% depleted FCS at least 6 h before an experiment was started. Antibodies were added 30 min before cells were stimulated for 4 h at 37°C with LPS, LPS·CD14, or MALP-2 at various concentrations. Thereafter, the cells were harvested and stained for flow cytometry analyses. Human peripheral blood monocytes were resuspended in DMEM/2% FCS and seeded into 24-well tissue culture plates at 1 × 104cells/well. After addition of antibodies for 30 min, cells were stimulated with either LPS or MALP-2 (1 ng/ml) for 4 h at 37°C. Supernatants were harvested, and hIL-8 was measured with an ELISA (Biosource, Camarillo, CA). Mouse EC were stimulated with LPS, MALP-2, or cytokines for 12 h in culture medium containing 5% FCS. Thereafter, medium was measured for mouse macrophage inflammatory protein-2 (MIP-2), which is the murine homologue of human IL-8, by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). For stimulation of HCAEC with low LPS concentrations or with preformed LPS·CD14 complexes, it was necessary to deplete serum of sCD14 or LBP using anti-CD14 (mAb 28C5) and anti-LBP (mAb 2B5) as described previously (21, 23). Depleted FCS contained <1 ng/ml of remaining antibodies (measured by ELISA). Both CD14 and LBP were below the detection limit of Western blotting (1 ng of protein in our experiments).LPS uptake experimentsHCAEC, or mouse EC, were grown to confluence in six-well tissue culture plates, and medium was changed to DMEM/2% FCS before experiments. 3H-LPS (100 ng/ml) or 3H-LPS·CD14 (100 ng/ml) was incubated for 2 h with the cells of one well along with various antibodies, sCD14, and LBP. Thereafter, the adherent cells were washed twice with PBS and further treated with 250 µg/ml proteinase K (Sigma) in HBSS for 30 min at room temperature to remove cell surface proteins/receptors (22). The 3H counts remaining after proteinase K treatment were therefore considered to be intracellular. This treatment also detached the cells, which were harvested, washed twice in PBS, and lysed in 300 µl 2% SDS/50 mM EDTA. Liquid samples were transferred to scintillation vials and assayed for counts in Ecoscint scintillation fluid (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA). The same procedure was carried out in experiments where 32P-labeled LBP (250 ng/ml) uptake was investigated.Transient transfectionOne day after seeding into six-well plates, HCAEC (5×105 cells/well) were transiently transfected with cDNA for CD14 or TLR4 in pFLAG-CMV.1 (Sigma) using 6 µl/well Lipofectin Reagent (Invitrogen) and 1.6 µg/well DNA in 100µl Opti-MEM I (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD). After 3 h under serum-free conditions, EGM-2-MV was added and cells were analyzed the following day for surface expression of CD14 or TLR4. In several experiments, transfection efficiency was typically 5–10%.StatisticsData are expressed as mean and standard error of the mean (SE). Means were compared by Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA and by Mann Whitney U test. A difference with P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were calculated using the StatView software package (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA).RESULTSFACS analyses of HCAEC do not detect surface TLR4To investigate cell surface expression of TLR2 and TLR4 protein, we performed several FACS analyses on monocytes and HCAEC and compared the results with the TLR2 and TLR4 mRNAexpression levels (Fig. 1). Nonpermeabilized HCAEC or monocytes were stained with 5 different anti-TLR4 (monoclonal HTA1216, HTA405, HTA414, HTA125, and polyclonal H80), anti-TLR2 (mAb 2392), or anti-CD14 (M5E2) primary antibodies. Dot blot assays with immobilized primary antibody confirmed that the secondary antibodies used were able to detect their primary partners (not shown). In contrast to human peripheral blood monocytes, which showed clear surface staining for TLR2, TLR4, and CD14, we could not detect TLR4 or CD14 on the surface of HCAEC, although the TLR4 mRNA expression was similar in monocytes and HCAEC. At an expression level of TLR2 mRNA (after induction with LPS-IFNγ or TNF-IFNγ) comparable to basal TLR4 mRNA levels, 92–98% of HCAEC stained positive for surface TLR2; even in unstimulated HCAEC, where almost no TLR2 mRNA was found, FACS still was able to detect surface TLR2. Although LPS-IFNγ enhanced TLR4 mRNA expression in HCAEC, TLR4 was still not detected on the surface. Figure 1 (HCAEC) shows a representative result of many experiments; in this experiment, HTA125 was used for TLR4 and anti-TLR2 2392 for TLR2 detection. Both antibodies worked very well in monocytes (see Fig. 1, Monocytes). However, upon transient transfection and overexpression of TLR4 or CD14 in HCAEC, some surface expression (~1% of cells) was seen in FACS analyses (see Fig. 1, HCAEC transfected), establishing that the detection system works in HCAEC.HCAEC express RNA for TLR2, TLR4, MD-2, and gp96, but not CD14 or LBPTo assess mRNA expression in HCAEC, RT-PCR analyses was performed. Agarose gel electrophoresis revealed clear bands at the expected fragment sizes for TLR2, TLR4, and MD-2. Stimulation of the HCAEC for 12 h with 10 ng/ml of E. coli LPS (O55:B5) did not significantly change TLR4 or MD-2 mRNA expression, but enhanced TLR2 mRNA. More important, neither stimulated nor unstimulated HCAEC were positive for LBP or CD14. As expected, mRNA for the chaperon protein gp96 was found in three different HCAEC preparations and in monocytes (Fig. 2).TLR4 is intracellular in HCAEC and on the surface of monocytesExpression of TLR4 mRNA in the absence of cell surface TLR4 led us to search for intracellular TLR4 in HCAEC by 3D-deconvolution confocal microscopy. In HCAEC, which are nontransfected cells, TLR4 was found exclusively around the nucleus (Fig. 3A–D). After stimulation of the cells, VCAM-1 was found intracellularly and surface expressed (Fig. 3C). Nonimmune rabbit IgG was used as control and revealed uniform background staining (not shown). In monocytes, use of the same anti-TLR4 antibody (H80), resulted in bright surface staining and showed colocalization of TLR4 to membrane CD14 (Fig. 3E).Anti-TLR4 antibodies do not block HCAEC response to LPSHCAEC activation was determined by measuring CD62E surface expression (Fig. 4). Preliminary experiments showed that CD62E is minimally expressed on resting cells, but is rapidly induced and highly expressed upon stimulation. HCAEC were incubated with various antibodies 30 min before stimulation with LPS (10 ng/ml) for 4 h. All anti-TLR4 antibodies used failed to inhibit LPS-induced activation of HCAEC. Even long-term preincubation (up to 12 h) of HCAEC with anti-TLR4 was not able to block LPS activation (not shown). This is in contrast to monocytes, where HTA405 or HTA125 significantly, but incompletely, inhibited LPS-induced IL-8 secretion. The effects of HTA405 on HCAEC or monocyte activation by LPS werefurther explored at a wide range of LPS and mAb concentrations (see Table 1). In no case werethe results qualitatively different from Figure 4. As anticipated from published work, the abilityof LPS to stimulate cells was abolished by anti-LBP (mAb 2B5) or anti-CD14 (mAb 28C5) inendothelial cells as well as in monocytes. Anti-TLR2 (mAb 2392) completely blocked MALP-2-induced cell activation in both cell types (Fig. 4). The fact that anti-TLR2 did not inhibit LPS-induced cell activation excludes the possibility that TLR2 agonist impurities in the LPSpreparation were responsible for activation of the cells. Similarly, lack of an effect of 2B5 onMALP-2-initiated activation suggests that there is not an LPS contaminant in MALP-2. In contrast to anti-TLR4, Compound 406 (lipid 4A) dose-dependently (0.1–100 µg/ml) inhibitedLPS-induced HCAEC activation (not shown).TLR4 is required for LPS signaling but not for LPS uptake in ECWe cultured pulmonary microvascular and aortic EC derived from TLR4 –/– C57/BL6 mice andcompared their response to LPS and other proinflammatory stimuli with cells from wild-typeanimals (Fig. 5). Compared with cultured HCAEC, the mouse cells did not respond well withCD62E expression to any stimulus, and therefore we measured MIP-2 secreted into the medium.Even after 12 h incubation with 10 ng/ml of E. c oli LPS (O55:B5), the TLR4 –/– cells were stillcompletely unresponsive to this stimulus, whereas the response to murine TNF (10 ng/ml),MALP-2 (100 ng/ml), or human IL-1 (10 ng/ml) was independent of TLR4 genotype. The wild-type cells were activated by all stimuli. Results shown (Fig. 5A) are from experiments withmurine aortic EC; lung microvascular EC responded similarly (data not shown). When TLR4 –/–cells were incubated with 3H-LPS (100 ng/ml) for 2 h with various concentrations of LBP and 3H-LPS uptake was measured, no difference was found compared with wild-type cells, suggesting that uptake occurs independently of TLR4 phenotype (Fig. 5B). Moreover, mouse ECLPS uptake mimicked the LPS uptake observed in human cells (HCAEC).LBP facilitates the uptake of LPS and LPS·CD14 complexes into HCAECBecause previous data show that sCD14 and LBP are required for LPS-induced HCAECactivation, we further investigated the role of these proteins in LPS uptake. HCAEC wereincubated for 2 h with 100 ng/ml of 3H-LPS along with an increasing amount of human LBP(Fig. 6A). LBP dose-dependently stimulated 3H-LPS uptake into cells. The maximum of theeffect was seen close to equimolarity of LPS with LBP and resulted in a ~10-fold increase in theamount of LPS transported into the cells. Because LPS·CD14 complexes are necessary for cellactivation, we were curious whether LBP would enhance uptake of complexes preformedwithout LBP, and found that LBP did enhance 3H-LPS·CD14 complex uptake ~5-fold. LBP-enhanced LPS and LPS·CD14 complex uptake was sensitive to an anti-LBP antibody (mAb2B5), but was never blocked completely and a low basal uptake remained. This suggests thatLBP is not absolutely necessary for the uptake of LPS and LPS·CD14 complexes. This basaluptake was insensitive to either anti-TLR4 (mAb HTA405), anti-LBP (mAb 2B5), or anti-CD14(mAb 28C5) (data not shown).Similar patterns of uptake are seen when LPS, sCD14, and LBP were added simultaneously andtherefore CD14 complexation of LPS was catalyzed by LBP (Fig. 6B). Thus LPS in the absenceof LBP, alone or in the presence of sCD14, is only minimally internalized as compared with LPSin the presence of LBP. When LBP catalyzed complexation of LPS to sCD14 is inhibited by anti-CD14 (mAb 28C5), uptake follows the LPS-LBP pattern (10-fold increase). When complexation of LPS to either sCD14 or LBP is inhibited by anti-LBP (mAb 2B5), the effects of both LBP and CD14 are abolished. Finally, data obtained with 32P-LBP (Fig. 6C) show that LBP is internalized with LPS and that the uptake follows the same pattern as observed when LPS uptake was measured.LPS, LBP, and CD14 all colocalize with intracellular TLR4In fact, LPS complexes are found intracellularly. HCAEC were incubated for 4 h with FITC-LPS (100 ng/ml) alone or with sCD14 (1.6 µg/ml), LBP (2.5 µg/ml), or both. Thereafter, cells were stained for TLR4, LBP, or CD14 (Fig. 7). Confocal microscopy showed clear colocalization of FITC-LPS and LBP (Fig. 7A), FITC-LPS and intracellular TLR4 (Fig. 7B), LBP and TLR4 in the presence of sCD14 (Fig. 7C), and finally sCD14 and TLR4 in the presence of LBP (Fig. 7D). Under serum-free conditions (without sCD14), where no cell activation occurs, no colocalization of either FITC-LPS (Fig. 7E) or LBP (Fig. 7F) with intracellular TLR4 was observed. Colocalization of LBP and CD14 could not be shown because both are detected by mouse antibodies and these could not be distinguished by labeled second antibodies. LBP or CD14 were never detected intracellularly when added without LPS; instead, large aggregates were found in the microscopic field outside the cells. When HCAEC were stimulated for 2 h with LPS (10 ng/ml), the intracellular adaptor molecule MyD88, which is involved in TLR4 signaling, was recruited to a perinuclear region (Fig. 7G). This was not the case in the absence of sCD14 (Fig. 7H).LBP enhances HCAEC activation at low LPS concentrations via facilitated LPS·CD14 uptakeBecause the preceding experiments revealed a role for LBP in LPS uptake, we were curious whether this would have an impact on cell activation. To exclude additional LPS complex formation during the experiments, CD14-depleted FCS was used for experiments with preformed LPS·CD14 complexes and, because we wanted to see effects of added recombinant LBP, LBP-depleted FCS was used for experiments with uncomplexed LPS. Neither CD14 nor LBP at the concentrations used in our experiments activated cells without LPS.Figure 8A shows that 10 ng/ml of LPS with 250 ng/ml LBP enabled a full response of the cells and sCD14 (160 ng/ml) showed no additional effect. When LPS and sCD14 were added without LBP under these conditions, a minimal stimulation was observed, probably due to incomplete LBP depletion of the serum. Stimulation under each condition was blocked by an anti-LBP antibody, thus confirming the necessity of LBP for LPS·CD14 complex formation during the 4 h course of these experiments.In contrast, 10 ng/ml of preformed LPS·CD14 complexes stimulated the cells without any effect of anti-LBP or additional LBP (Fig. 8C), suggesting that LBP is not absolutely required (Fig. 6A) for sufficient uptake of preformed LPS·CD14 complexes at 10 ng/ml. However, uptake did occur, because a blocking anti-TLR4 (mAb HTA405), which would block surface TLR4, failed to inhibit activation even when added together with anti-LBP (mAb 2B5).At a low LPS concentration (0.1 ng/ml) (Fig. 8B), addition of sCD14 (100 ng/ml) did not stimulate cells. Providing LBP (200 ng/ml) enabled a response of the cells, which was further enhanced by additional sCD14. Activation was again blocked by anti-LBP (mAb 2B5), which would also inhibit rapid LBP catalyzed formation of stimulatory LPS·CD14 complexes. Preformed LPS·CD14 complexes at 0.1 ng/ml (Fig. 8D) did not stimulate cells in CD14-depleted FCS. When additional LBP was provided, cell stimulation was observed, which cannot be explained by LBP catalyzed LPS·sCD14 complex formation, because preformed complexes were added in CD14 depleted medium. Again, stimulation was insensitive to anti-TLR4 (mAb HTA405) and therefore mediated by intracellular TLR4.Thus, at 0.1 ng/ml of LPS, LBP enhances the uptake of LPS·CD14 complexes, preformed in vitro (Fig. 8D) or formed by LBP-mediated catalysis (Fig. 8B), and this LBP-enhanced uptake results in HCAEC activation.LBP-stimulated LPS uptake into HCAEC involves a scavenger receptor pathwaySome scavenger receptors have been shown to be lipid A or LPS uptake receptors (31–33). Because HCAEC were found to be CD14 negative, we were curious whether scavenger receptor blocking agents would affect the LPS uptake in these cells. HCAEC were pretreated with dextran sulfate (MW 8000), polyinosinic acid (PIA), polyadenylic acid (PAA), or polycytidylic acid (PCA) for 30 min before measurement of 3H-LPS uptake with or without additional LBP. Both dextran and PIA reduced the LBP-enhanced 3H-LPS uptake to the level of basal 3H-LPS uptake, whereas the polycationic substances PAA and PCA lacked this effect (Fig. 9). Unfortunately, both dextran sulfate and PIA activated HCAEC to express surface CD62E even in the absence of added LPS (data not shown).DISCUSSIONTo begin a study of regulation and modification of TLR2 and TLR4 expression in HCAEC under various conditions, we performed FACS analyses on those cells, but despite the use of several different anti-TLR4 antibodies, we never observed positive surface staining for TLR4. Nevertheless, the cells responded well to both TLR2 and TLR4 agonists, and mRNA for both TLR2 and TLR4 was expressed. TLR2 mRNA was only weakly detectable in resting cells, but the TLR2 protein was still found on the HCAEC surface by FACS, confirming the high sensitivity of this method. After stimulation of the cells, TLR2 mRNA levels corresponded to TLR2 surface expression. However, this was not observed for TLR4. Despite high expression of TLR4 mRNA in both monocytes and HCAEC, TLR4 protein was never seen on the surface of HCAEC. The reliability of the detection system was confirmed in monocytes, which stained well for TLR2 and TLR4 on the surface, and in transfected HCAEC, where some TLR4 surface protein could be detected by FACS after transfection and overexpression of human TLR4.With the knowledge that TLR4 has been shown to reside in the Golgi apparatus in murine intestinal epithelial cells (28) and that LPS is transported to the Golgi in human epithelial HeLa cells (34), we further investigated HCAEC using confocal microscopy and found TLR4 located in a perinuclear region but not on the surface, where VCAM-1 was observed after cell stimulation. This is in contrast to monocytes, where TLR4 was clearly seen to colocalize with。