Consumption, income, and wealth inequality in Canada

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:896.34 KB

- 文档页数:24

如何平衡消费和储蓄英语作文Balancing Consumption and Savings: A Key to Financial Wellness.In the modern era, the concept of balancing consumption and savings has become increasingly important. With therise of consumerism and the ease of access to credit, it is easy to get caught up in the cycle of spending without considering the long-term consequences. However, a balanced approach to consumption and savings is crucial for maintaining financial stability and achieving financial goals.Consumption refers to the act of purchasing goods and services to meet current needs and desires. It is a natural part of life, as it fulfills our basic requirements and enhances our quality of life. However, over-consumption can lead to financial problems, such as debt and credit card balances that are difficult to manage.On the other hand, savings refer to the act of setting aside money for future needs and goals. Savings provide a financial cushion during emergencies, such as job loss or medical expenses, and also help in achieving long-term financial goals, such as purchasing a home or retiring comfortably.To strike a balance between consumption and savings, it is important to follow a few key principles:1. Budgeting: Creating a budget and sticking to it is essential for balancing consumption and savings. A budget helps you track your income and expenses, identify areas where you can cut back, and allocate funds for savings. By setting aside a certain amount of money each month for savings, you can build a financial cushion that will protect you during unexpected events.2. Prioritizing Needs over Wants: Distinguishing between needs and wants is crucial for balancing consumption. Needs are the basic requirements for survival and well-being, such as food, shelter, and healthcare.Wants, on the other hand, are discretionary purchases that enhance our quality of life but are not essential for survival. By prioritizing needs over wants, you can ensure that your basic requirements are met while still allocating funds for savings.3. Paying Off Debt: If you have existing debt, such as credit card balances or loans, it is important to make a plan to pay them off as soon as possible. Interest payments on debt can eat into your budget and prevent you from saving effectively. By making extra payments or increasing your monthly payments, you can reduce your debt burden and free up more funds for savings.4. Saving Automatically: Setting up automatic transfers from your checking account to your savings account can help you save without even thinking about it. By scheduling regular transfers, you can ensure that you are saving a certain amount of money each month without having to manually transfer funds. This can make saving easier and more effective.5. Investing for the Future: In addition to setting aside funds for emergency savings, it is important to invest for the future. Investing your savings in stocks, bonds, or other investment vehicles can help you grow your money and achieve long-term financial goals. However, it is important to do your research and consult with a financial advisor to ensure that your investments align with yourrisk tolerance and financial goals.In conclusion, balancing consumption and savings is essential for maintaining financial stability and achieving financial goals. By following the principles of budgeting, prioritizing needs over wants, paying off debt, saving automatically, and investing for the future, you can ensure that you are making smart financial decisions that will benefit you in the long run. Remember, financial wellnessis a journey, not a destination, and it requires constant attention and effort to maintain.。

20CONSUMPTION ANDINVESTMENTOVERVIEW1. Consumption is expenditure by consumers and typically accounts for 65 percent of grossdomestic product.2. The consumption function is a direct relation that tells how much is consumed at eachlevel of income.3. The marginal propensity to consume is the amount that consumption changes whenincome changes by one dollar.4. Saving is the part of income that is not spent for consumption or taxes.5. The saving function is a direct relation that tells how much is saved at each level ofincome.6. The marginal propensity to save is the amount that saving changes when income changesby one dollar.7. Since each extra dollar is either spent or saved, the marginal propensity to consume plusthe marginal propensity to save is equal to one.8. Investment is the purchase of new capital by business and typically accounts for 15percent of GDP.9. The amount of investment depends on the interest rate. At high interest rates, a firm canchoose between saving money at the high interest rate or using the money to buy capital goods. It will not buy the capital goods unless the capital good earns more than the firm can earn at the interest rate. The higher the interest rate, the fewer the capital goods which pay a return higher than the interest rate. As the interest rate falls, more and more capital goods will pay more than the interest rate and will be purchased. Thus there is an inverse relation between investment and the interest rate.MATCHING______ 1. consumptionfunction______ 2. marginalpropensity toconsume______ 3. saving______ 4. savingfunction ______ 5. marginalpropensity to save______ 6. dissaving______ 7. investment a. that part of income not spent forconsumption or on taxesb. the change in saving whenincome changes by one dollarc. spending by business for newplant, equipment, and inventories d. the relationship between the levelof income and the level ofconsumptione. the relationship between the levelof income and the level of saving f. the amount consumption changeswhen income changes by onedollarg. when consumption is greater thanincomeTRUE-FALSE______ 1. The marginal propensity to consume is usually larger than one.______ 2. The sum of the marginal propensity to consume and the marginalpropensity to save is one.______ 3. When income rises, consumption also rises.______ 4. When income rises, we can compute the amount that consumption rises if we know the MPC.______ 5. When the interest rate rises, investment also rises.PROBLEMS1. a. Given the following information, find the marginal propensity to consume.Y C MPC S MPS MPC + MPS0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 100175250325400475550625700- - -b. Using the information given above and the fact that Y = C + S, find saving.c. Use the saving information to find the MPS.d. Find the sum of MPC and MPS.2. a. Suppose that at zero income, $40 is consumed. If the MPC is .8, how do we findconsumption at Y = 100? The MPC tells how much C goes up if Y goes up by $1. In this case C goes up $.80. If Y goes up $1 and C goes up $.80, how much does C go up if Y goes up $100? $80. Eighty dollars added to the $40 already consumed leavesconsumption of $120 at the $100 level of income. Using this process, fill in the rest of the table at MPC = .8.MPC = .8 MPC = .9Y 0 100 200 300 400 500C40120C40b. Change the MPC to .9 and find consumption again.c. How does the increase in the MPC affect consumption?_____________________________________________________________________ 3.a. Suppose that income rises from 500 to 600 and the MPC is .7. How muchwill consumption rise? ___________________b. Suppose that the income rises from 500 to 600 and the MPC is .8. Howmuch will saving rise? ___________________IN THE NEWS1. Consumption is the total expenditure on goods and services by consumers. The usualeconomic assumption is that consumption depends on the level of income. But studiessuggest that wealth plays a role in determining consumption.a Can you find a reason why wealth would affect consumption? ____________________________________________________________________________________b. What other determinants can you suggest that might affect how consumers spend?___________________________________________________________________2. Investment is thought to depend on the interest rate. Yet studies of investment do not finda prominent role for the interest rate. Firms claim that the investment decision depends onexpectations of future sales and expectations of how technology is changing.a. How would expectations of future sales affect investment? _____________________b. How would expectations of how technology is changing affect investment? _____________________________________________________________________________ 3. Economists claim that consumption and income are directly related. This means thatwhen one goes up, so does the other. In 1957, GDP was $683 billion and consumptionwas $414 billion. But in the next year, GDP fell to $681 billion, and consumption rose to $418 billion. These figures are all in real terms.How can consumption go up when income goes down? _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 4. Consumption expenditure is about 63 percent of GDP and seems to stay at this level.There are some variations but this percentage has not changed much in the last few years.a. Is 63 percent the MPC? ___________ Explain. ___________________________________________________________________________________________________b. What information would we need to find MPC? __________________________________________________________________________________________________PRACTICE TESTCircle the correct answer1. The concept which shows how much of an extra dollar will go into extra consumptionis known as the:a. average propensity to save.b. average propensity to consume.c. marginal propensity to save.d. marginal propensity to consume.2. Find the correct relation.a. GDP + MPS = 100 percentb. MPC + MPS = 100 percentc. MPC + 1 = 100 percentd. MPC - MPS = 100 percent3. Investment is business spending on:a. resources.b. capital goods.c. stocks and bonds.d. all of the above.4. Consumption varies __________ with the level of income; investment varies__________ with the interest rate.a. directly, inverselyb. inversely, directlyc. directly, directlyd. inversely, inversely5. What if the MPC is 3/4? The MPS is:a. 4/3.b. 3/4.c. 2/4.d. 1/4.ANSWERSMatching1. d2. f3. a4. e5. b6. g7. cTrue-False1. F2. T3. T4. T5. FProblems1. a., b., c., d.Y C MPC S MPS MPC + MPS0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 100175250325400475550625700-.75.75.75.75.75.75.75.75-100-75-50-25255075100-.25.25.25.25.25.25.25.25-1.01.01.01.01.01.01.01.02 a.,b.MPC = .8 MPC = .9Y C C0 100 200 300 400 500 4012020028036044040130220310400490c. The consumption function rises. At each Y, consumption is higher.3.a. Suppose that income rises from 500 to 600 and the MPC is .7. How muchwill consumption rise? _______70__________b. Suppose that the income rises from 500 to 600 and the MPC is .8. Howmuch will saving rise? _______20__________In the News1. a. Wealth is stored up income. So the larger the store of wealth, the more there is tospend when desired. I Therefore more wealth should make more consumption.b. There are other determinants that may be important. The interest rate affectsconsumption. If the interest rate decreases, then people are willing to borrow moreand spend more. So consumption might be inversely related to the interest rate.Consumer confidence and expectations have an important role in spending decisions too. If consumers are concerned about the future, they will not spend so much. Theprice level will not affect consumption because both the income and consumption inreal terms.2. a. A firm with high expectations will be willing to invest because it is sure that it canpay back what it owes. If the firm is uncertain about the future, it will be moreconservative about borrowing and investing.b. If a firm thinks that the technology is changing very quickly, it may want to wait untilthe next generation of technology comes along before it buys. If there just has been a major change in the technology, and there does not appear to be breakthroughs on the horizon, then it may be a good time to invest.3. The reason that income (GDP) fell was that investment went down. Consumersapparently felt that the decrease in income was just a temporary dip and kept on spending.This is a suggestion that considerations besides income affect the level of consumption.4. a. No, 63 percent is not the marginal propensity to consume. The 63 percent tells theaverage amount consumed out of GDP but does not tell how consumption changes as income changes.b. To find the marginal propensity to consume, we would need to know howconsumption changed when income changed.Practice Test1.d.,2.b.,3.b.,4.a.,5.d.。

财政学双语重点(重中之重啊!)1.Unified budget: The document which itemizes(逐项列出)all the federal government’s expenditures(支出)and revenues (收入).统一预算:联邦政府在一种文件中将其支出逐项列出。

2.substitution effect: The tendency of an individual to consume more of one good andless of another because of a decrease in the price of the former relative to the latter.替代效应一个人因一种商品相对于另一种商品的价格降低而多消费前者,少消费后者的倾向。

3. income effect :The effect of a price change on the quantity demanded(需求量)due exclusively(唯一的)to the fact that the consumer’s income has changed.收入效应价格变化对需求量的影响完全是由于消费者的实际收入的变化所致。

4. Pareto efficient: An allocation of resources such that no person can be made better off without making another person worse off.帕累托效率一种资源配置状态,在该状态下,如果不使一个人的境况变差就不可能使另一个人的境况变好。

5. Pareto improvement: A reallocation of resources that makes at least one person better off without making anyone else worse off.帕累托改进资源的重新配置可在不使任何人的境况变差的前提下,至少使一个人的境况变好。

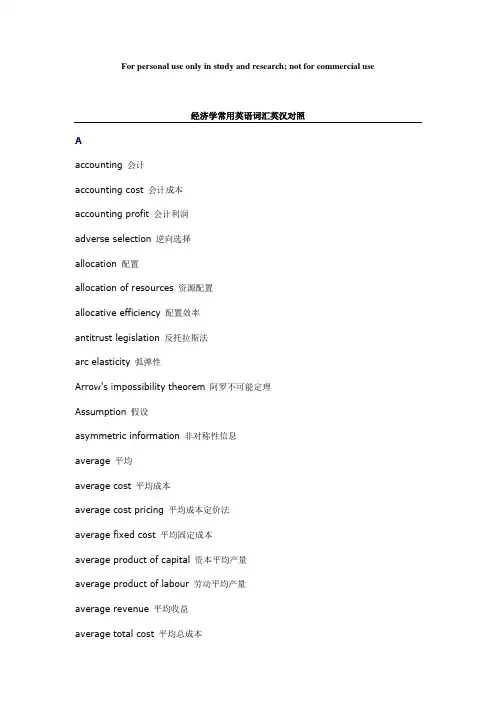

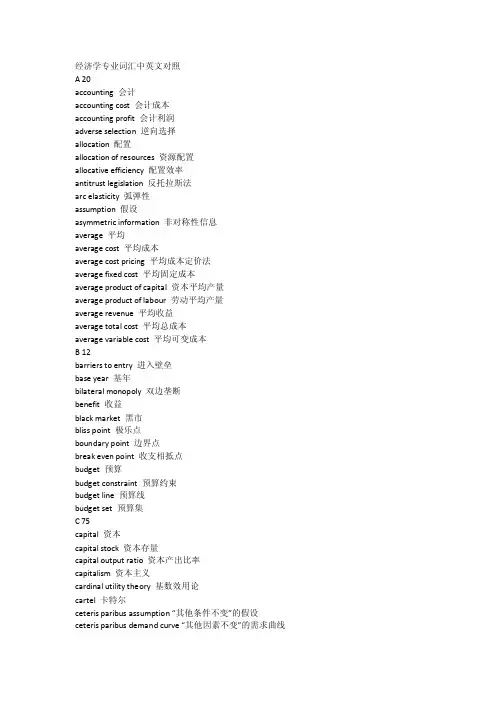

For personal use only in study and research; not for commercial use经济学常用英语词汇英汉对照Aaccounting会计accounting cost会计成本accounting profit会计利润adverse selection逆向选择allocation配置allocation of resources资源配置allocative efficiency配置效率antitrust legislation反托拉斯法arc elasticity弧弹性Arrow's impossibility theorem阿罗不可能定理Assumption假设asymmetric information非对称性信息average平均average cost平均成本average cost pricing平均成本定价法average fixed cost平均固定成本average product of capital资本平均产量average product of labour劳动平均产量average revenue平均收益average total cost平均总成本average variable cost平均可变成本Bbarriers to entry进入壁垒base year基年bilateral monopoly双边垄断benefit收益black market黑市bliss point极乐点boundary point边界点break even point收支相抵点budget预算budget constraint预算约束budget line预算线budget set预算集Ccapital资本capital stock资本存量capital output ratio资本产出比率capitalism资本主义cardinal utility theory基数效用论cartel卡特尔ceteris puribus assumption“其他条件不变”的假设ceteris puribus demand curve其他因素不变的需求曲线Chamberlin model张伯伦模型change in demand需求变化change in quantity demanded需求量变化change in quantity supplied供给量变化change in supply供给变化choice选择closed set闭集Coase theorem科斯定理Cobb—Douglas production function柯布--道格拉斯生产函数cobweb model蛛网模型collective bargaining集体协议工资collusion合谋command economy指令经济commodity商品commodity combination商品组合commodity market商品市场commodity space商品空间common property公用财产comparative static analysis比较静态分析compensated budget line补偿预算线compensated demand function补偿需求函数compensation principles补偿原则compensating variation in income收入补偿变量competition竞争competitive market竞争性市场complement goods互补品complete information完全信息completeness完备性condition for efficiency in exchange交换的最优条件condition for efficiency in production生产的最优条件concave凹concave function凹函数concave preference凹偏好consistence一致性constant cost industry成本不变产业constant returns to scale规模报酬不变constraints约束consumer消费者consumer behavior消费者行为consumer choice消费者选择consumer equilibrium消费者均衡consumer optimization消费者优化consumer preference消费者偏好consumer surplus消费者剩余consumer theory消费者理论consumption消费consumption bundle消费束consumption combination消费组合consumption possibility curve消费可能曲线consumption possibility frontier消费可能性前沿consumption set消费集consumption space消费空间continuity连续性continuous function连续函数contract curve契约曲线convex凸convex function凸函数convex preference凸偏好convex set凸集corporatlon公司cost成本cost benefit analysis成本收益分cost function成本函数cost minimization成本极小化Cournot equilihrium古诺均衡Cournot model古诺模型Cross—price elasticity交叉价格弹性Ddead—weights loss重负损失decreasing cost industry成本递减产业decreasing returns to scale规模报酬递减deduction演绎法demand需求demand curve需求曲线demand elasticity需求弹性demand function需求函数demand price需求价格demand schedule需求表depreciation折旧derivative导数derive demand派生需求difference equation差分方程differential equation微分方程differentiated good 差异商品differentiated oligopoly差异寡头diminishing marginal substitution边际替代率递减diminishing marginal return收益递减diminishing marginal utility边际效用递减direct approach直接法direct taxes直接税discounting贴税、折扣diseconomies of scale规模不经济disequilibrium非均衡distribution分配division of labour劳动分工distribution theory of marginal productivity边际生产率分配论duopoly双头垄断、双寡duality对偶durable goods耐用品dynamic analysis 动态分析dynamic models动态模型EEconomic agents经济行为者economic cost经济成本economic efficiency经济效率economic goods经济物品economic man经济人economic mode经济模型economic profit经济利润economic region of production生产的经济区域economic regulation经济调节economic rent经济租金exchange交换economics经济学exchange efficiency交换效率economy经济exchange contract curve交换契约曲线economy of scale规模经济Edge worth box diagram埃奇沃思图exclusion排斥性、排他性Edge worth contract curve埃奇沃思契约线Edge worth model埃奇沃思模型efficiency效率,效益efficiency parameter效率参数elasticity弹性elasticity of substitution替代弹性endogenous variable内生变量endowment禀赋endowment of resources资源禀赋Engel curve恩格尔曲线entrepreneur企业家entrepreneurship企业家才能entry barriers进入壁垒entry/exit decision进出决策envelope curve包络线equilibrium均衡equilibrium condition均衡条件equilibrium price均衡价格equilibrium quantity均衡产量equity公平equivalent variation in income收入等价变量excess—capacity theorem过度生产能力定理excess supply过度供给exchange交换exchange contract curve交换契约曲线exclusion排斥性、排他性exclusion principle排他性原则existence存在性existence of general equilibrium总体均衡的存在性exogenous variables外生变量expansion paths扩展径expectation期望expected utility期望效用expected value期望值expenditure支出explicit cost显性成本external benefit外部收益external cost外部成本external economy外部经济external diseconomy外部不经济externalities外部性FFactor要素factor demand要素需求factor market要素市场factors of production生产要素factor substitution要素替代factor supply要素供给fallacy of composition合成谬误final goods最终产品firm企业firms’ demand curve for labor企业劳动需求曲线firm supply curve企业供给曲线first-degree price discrimination第一级价格歧视first—order condition一阶条件fixed costs固定成本fixed input固定投入fixed proportions production function固定比例的生产函数flow流量fluctuation波动for whom to produce为谁生产free entry自由进入free goods自由品,免费品free mobility of resources资源自由流动free rider搭便车,免费搭车function函数future value未来值Ggame theory对策论、博弈论general equilibrium总体均衡general goods一般商品Giffen goods吉芬晶收入补偿需求曲线Giffen's Paradox吉芬之谜Gini coefficient吉尼系数golden rule黄金规则goods货物government failure政府失败government regulation政府调控grand utility possibility curve总效用可能曲线grand utility possibility frontier总效用可能前沿Hheterogeneous product异质产品Hicks—kaldor welfare criterion希克斯一卡尔多福利标准homogeneity齐次性homogeneous demand function齐次需求函数homogeneous product同质产品homogeneous production function齐次生产函数horizontal summation水平和household家庭how to produce如何生产human capital人力资本hypothesis假说Iidentity恒等式imperfect competition不完全竞争implicit cost隐性成本income收入income compensated demand curve income constraint收入约束income consumption curve收入消费曲线income distribution收入分配income effect收入效应income elasticity of demand需求收入弹性increasing cost industry成本递增产业increasing returns to scale规模报酬递增inefficiency缺乏效率index number指数indifference无差异indifference curve无差异曲线indifference map无差异族indifference relation无差异关系indifference set无差异集indirect approach间接法individual analysis个量分析individual demand curve个人需求曲线individual demand function个人需求函数induced variable引致变量induction归纳法industry产业industry equilibrium产业均衡industry supply curve产业供给曲线inelastic缺乏弹性的inferior goods劣品inflection point拐点information信息information cost信息成本initial condition初始条件initial endowment初始禀赋innovation创新input投入input—output投入—产出institution制度institutional economics制度经济学insurance保险intercept截距interest利息interest rate利息率intermediate goods中间产品internalization of externalities外部性内部化invention发明inverse demand function逆需求函数investment投资invisible hand看不见的手isocost line等成本线,isoprofit curve等利润曲线isoquant curve等产量曲线isoquant map等产量族Kkinded—demand curve弯折的需求曲线Llabour劳动labour demand劳动需求labour supply劳动供给labour theory of value劳动价值论labour unions工会laissez faire自由放任Lagrangian function拉格朗日函数Lagrangian multiplier拉格朗乘数,land土地law法则law of demand and supply供需法law of diminishing marginal utility边际效用递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution边际替代率递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of technical substitution边际技术替代率law of increasing cost成本递增法则law of one price单一价格法则leader—follower model领导者--跟随者模型least—cost combination of inputs最低成本的投入组合leisure闲暇Leontief production function列昂节夫生产函数licenses许可证linear demand function线性需求函数linear homogeneity线性齐次性linear homogeneous production function线性齐次生产函数long run长期long run average cost长期平均成本long run equilibrium长期均衡long run industry supply curve长期产业供给曲线long run marginal cost长期边际成本long run total cost长期总成本Lorenz curve洛伦兹曲线loss minimization损失极小化1ump sum tax一次性征税luxury奢侈品Mmacroeconomics宏观经济学marginal边际的marginal benefit边际收益marginal cost边际成本marginal cost pricing边际成本定价marginal cost of factor边际要素成本marginal period市场期marginal physical productivity实际实物生产率marginal product边际产量marginal product of capital资本的边际产量marginal product of 1abour劳动的边际产量marginal productivity边际生产率marginal rate of substitution边替代率marginal rate of transformation边际转换率marginal returns边际回报marginal revenue边际收益marginal revenue product边际收益产品marginal revolution边际革命marginal social benefit社会边际收益marginal social cost社会边际成本marginal utility边际效用marginal value products边际价值产品market市场market clearance市场结清,市场洗清market demand市场需求market economy市场经济market equilibrium市场均衡market failure市场失败market mechanism市场机制market structure市场结构market separation市场分割market regulation市场调节market share市场份额markup pricing加减定价法Marshallian demand function马歇尔需求函数maximization极大化microeconomics微观经济学minimum wage最低工资misallocation of resources资源误置mixed economy混合经济model模型money货币monopolistic competition垄断竞争monopolistic exploitation垄断剥削monopoly垄断,卖方垄断monopoly equilibrium垄断均衡monopoly pricing垄断定价monopoly regulation垄断调控monopoly rents垄断租金monophony买方垄断NNash equilibrium纳什均衡Natural monopoly自然垄断Natural resources自然资源Necessary condition必要条件necessities必需品net demand净需求nonconvex preference非凸性偏好nonconvexity非凸性nonexclusion非排斥性nonlinear pricing非线性定价nonrivalry非对抗性nonprice competition非价格竞争nonsatiation非饱和性non--zero—sum game非零和对策normal goods正常品normal profit正常利润normative economics规范经济学Oobjective function目标函数oligopoly寡头垄断oligopoly market寡头市场oligopoly model寡头模型opportunity cost机会成本optimal choice最佳选择optimal consumption bundle消费束perfect elasticity完全有弹性optimal resource allocation最佳资源配置optimal scale最佳规模optimal solution最优解optimization优化ordering of optimization(social) preference (社会)偏好排序ordinal utility序数效用ordinary goods一般品output产量、产出output elasticity产出弹性output maximization产出极大化Pparameter参数Pareto criterion帕累托标准Pareto efficiency帕累托效率Pareto improvement帕累托改进Pareto optimality帕累托优化Pareto set帕累托集partial derivative偏导数partial equilibrium局部均衡patent专利pay off matrix收益矩阵、支付矩阵perceived demand curve感觉到的需求曲线perfect competition完全竞争perfect complement完全互补品perfect monopoly完全垄断perfect price discrimination完全价格歧视perfect substitution完全替代品perfect inelasticity完全无弹性perfectly elastic完全有弹性perfectly inelastic完全无弹性plant size工厂规模point elasticity点弹性positive economics实证经济学post Hoc Fallacy后此谬误prediction预测preference偏好preference relation偏好关系present value现值price价格price adjustment model价格调整模型price ceiling最高限价price consumption curve价格费曲线price control价格管制price difference价格差别price discrimination价格歧视price elasticity of demand需求价格弹性price elasticity of supply供给价格弹性price floor最低限价price maker价格制定者price rigidity价格刚性price seeker价格搜求者price taker价格接受者price tax从价税private benefit私人收益principal—agent issues委托--代理问题private cost私人成本private goods私人用品private property私人财产producer equilibrium生产者均衡producer theory生产者理论product产品product transformation curve产品转换曲线product differentiation产品差异product group产品集团production生产production contract curve生产契约曲线production efficiency生产效率production function生产函数production possibility curve生产可能性曲线productivity生产率productivity of capital资本生产率productivity of labor劳动生产率profit利润profit function利润函数profit maximization利润极大化property rights产权property rights economics产权经济学proposition定理proportional demand curve成比例的需求曲线public benefits公共收益public choice公共选择public goods公共商品pure competition纯粹竞争rivalry对抗性、竞争pure exchange纯交换pure monopoly纯粹垄断Qquantity—adjustment model数量调整模型quantity tax从量税quasi—rent准租金Rrate of product transformation产品转换率rationality理性reaction function反应函数regulation调节,调控relative price相对价格rent租金rent control规模报酬rent seeking寻租rent seeking economics寻租经济学resource资源resource allocation资源配置returns报酬、回报returns to scale规模报酬revealed preference显示性偏好revenue收益revenue curve收益曲线revenue function收益函数revenue maximization收益极大化ridge line脊线risk风险Ssatiation饱和,满足saving储蓄scarcity稀缺性law of scarcity稀缺法则second—degree price discrimination二级价格歧视second derivative --阶导数second—order condition二阶条件service劳务set集shadow prices影子价格short—run短期short—run cost curve短期成本曲线short—run equilibrium短期均衡short—run supply curve短期供给曲线shut down decision关闭决策shortage短缺shut down point关闭点single price monopoly单一定价垄断slope斜率social benefit社会收益social cost社会成本social indifference curve社会无差异曲线social preference 社会偏好social security社会保障social welfare function社会福利函数socialism社会主义solution解space空间stability稳定性stable equilibrium稳定的均衡Stackelberg model斯塔克尔贝格模型static analysis静态分析stock存量stock market股票市场strategy策略subsidy津贴substitutes替代品substitution effect替代效应substitution parameter替代参数sufficient condition充分条件supply供给supply curve供给曲线supply function供给函数supply schedule供给表Sweezy model斯威齐模型symmetry对称性symmetry of information信息对称Ttangency相切taste兴致technical efficiency技术效率technological constraints技术约束technological progress技术进步technology技术third—degree price discrimination第三级价格歧视total cost总成本total effect总效应total expenditure总支出total fixed cost总固定成本total product总产量total revenue总收益total utility总效用total variable cost总可变成本traditional economy传统经济transitivity传递性transaction cost交易费用Uuncertainty不确定性uniqueness唯一性unit elasticity单位弹性unstable equilibrium不稳定均衡utility效用utility function效用函数utility index效用指数utility maximization效用极大化utility possibility curve效用可能性曲线utility possibility frontier效用可能性前沿VValue价值value judge价值判断value of marginal product边际产量价值variable cost可变成本variable input可变投入variables变量vector向量visible hand看得见的手vulgar economics庸俗经济学Wwage工资wage rate工资率Walras general equilibrium瓦尔拉斯总体均衡Walras's law瓦尔拉斯法则Wants需要Welfare criterion福利标准Welfare economics福利经学Welfare loss triangle福利损失三角形welfare maximization福利极大化Zzero cost零成本zero elasticity零弹性zero homogeneity零阶齐次性zero economic profit零利润仅供个人用于学习、研究;不得用于商业用途。

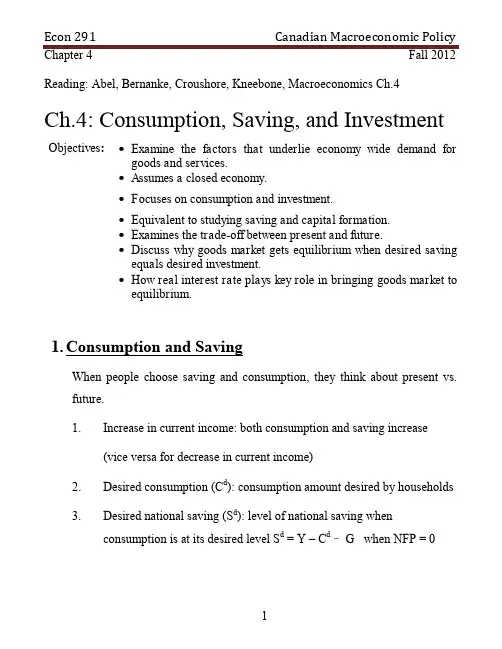

Reading: Abel, Bernanke, Croushore, Kneebone, Macroeconomics Ch.4 Ch.4: Consumption, Saving, and Investment Objectives: ∙Examine the factors that underlie economy wide demand for goods and services.∙Assumes a closed economy.∙Focuses on consumption and investment.∙Equivalent to studying saving and capital formation.∙Examines the trade-off between present and future.∙Discuss why goods market gets equilibrium when desired savingequals desired investment.∙How real interest rate plays key role in bringing goods market toequilibrium.1.Consumption and SavingWhen people choose saving and consumption, they think about present vs.future.1. Increase in current income: both consumption and saving increase(vice versa for decrease in current income)2. Desired consumption (C d): consumption amount desired by households3. Desired national saving (S d): level of national saving whenconsumption is at its desired level S d = Y – C d– G when NFP = 0A. The consumption and saving decision of an individual.1). The rate a person trades off current and future consumption dependson the ____________ interest rate prevailing in the economy.▪The real interest rate is the amount that a lender can earn, or a borrower will have to pay for every dollar lent/borrowed per year.2). The real interest rate, r, determines the __________________ ofcurrent consumption and future consumption.▪$1 worth of consumption today is equivalent to _________ dollar’s worth of consumption in the next time period. (Assuming inflation = 0).B. Effects of changes in current income1). Recall: Keynesian consumption function: C d = a +bY da). Desired consumption depends on current aggregate disposableincomeb). b = marginal propensity to consume (MPC); between 0 and 1The ______________ of additional current income that oneconsumes in the current period is the marginal propensity toconsume (MPC)MPC = ∆C d/ ∆Y dc). a = autonomous consumption: consumption that is_________________from income.2). When current income (Y) rises by $1, C d rises, but not by as much as Y,so S d ___________. S d rises by the fraction of the $1 ______ spent on consumption.C. The effects of changes in expected future income1). Higher expected future income leads to ____________ consumptiontoday because of consumption smoothing motive, so current saving_______________.▪ The consumption-smoothing motive is the desire to have a relatively __________ pattern of consumption over time.▪ A one-time income bonus is likely to be _________and the income earned on that saving spread over time.2). Current consumption will ______________ and current savings will______________ when expected future income increases, because of the smoothing motive.D. Effects of changes in wealth1). Increase in wealth ____________ current consumption, so____________current saving because one does not need to save asmuch for the future anymore.2). Housing wealth and consumer spending:Consumers increase spending more due to increase in housing wealththan by increase in stock market wealth. The three reasons area). 2/3 of households own their homes;b) Stock prices are far more volatile than are housing prices; andc) Increases in wealth arising from increases in housing prices areexempt from capital gain taxation.E. Effect of changes in the real interest rate1). For a lender an increase in real interest rate has two opposite effects:a). The income effect (IE) of the real interest rate reflects a__________effect on saving, since increase in current incomefrom wealth will ____________ current consumption and thus_____________ in current saving.b). The substitute effect (SE) of the real interest rate on savingreflects the _______________ effect on saving, since theopportunity cost of current consumption increases and thusincrease current saving.2). For a borrower when real interest rate increases, the substitution effectand income effect both result in _____________ in saving.3). Empirical evidence is that an increase in real interest rate ___________consumption and _____________ saving, but the effect is not very strong.4). Taxes and the real return to saving► Expected after-tax real interest rate: r a-t = (1- t)i - πeQ: i = 5%, πe = 2%; if t = 30%, what is r a-t?How about if t = 20%?A:By reducing the tax rate on interest the government can increase thereal rate of return for saver and (possibly) increase the rate of saving in the economy.F. Fiscal Policy▪Assumption: the economy’s aggregate output is given; it is not affected by the change in fiscal policy.▪The government fiscal policy has two major components: _______________________________ and __________________.1). Government purchases (G) (temporary increase)a). Higher G financed by current taxes reduces after-tax income,lowering desired consumption.b). Even true if financed by higher future taxes, if people realizehow future incomes are affected.c). Since C d declines less than G rises, national saving(S d = Y - C d - G) declines.d). So government purchases reduce both ________and ________.2). Taxesa). Lump-sum tax cut today, financed by higher future taxesb). Decline in future income __________ increase in current income.c). Ricardian equivalence proposition(i) If future income loss exactly offset current income gain,there is ______________________ in consumption.(ii) Tax change affects only the ____________ of taxes, not theirultimate amount.(iii) In practice, people may not see that future taxes will rise iftaxes are cut today; then a tax cut leads to _____________desiredconsumption and ______________ desired national saving.2.InvestmentA. Why is investment important?1). Investment fluctuates _____________ over the business cycle, so weneed to understand investment to understand the business cycle.2). Investment plays a crucial role in ________________________ anddetermines the long run ________________________________ of theeconomy.B. The desired capital stock1). Desired capital stock is the amount of capital that allows firms toearn the ____________ expected profit.2). Desired capital stock depends on costs and benefits of ____________capital.3). Since investment becomes capital stock with a __________, thebenefit of investment is the _____________ marginal product ofcapital (MPK f).4). The user cost of capitala). User cost of capital = real cost of using a unit of capital for aspecified period of time.b). It includes cost of capital, depreciation rate, and expected realinterest rate.►5). Determining the desired capital stocka). Desired capital stock is the level of capital stock at which__________________________.b). MPK f falls as K rises due to diminishing marginal productivity,thus MPK f is _______________ sloping.c). uc doesn’t vary with K, so is a horizontal lined). If MPK f > uc, profits rise as K is added (____________________)e). If MPK f < uc, profits rise as K is reduced (__________________)f). Profits are maximized where _________________.MPK f, ucKC. Changes in the desired capital stock1). Factors that shift the MPK f curve or change the user cost of capitalcause the desired capital stock to change.2). These factors are changed in the ___________________,____________________________, __________________________,or _______________________________ that affect the MPK f.E.g.1. A decline in the real interest rateMPK fK Result:E.g.2. The economy experiences technological advancementMPK fKResult:3). Taxes and the desired capital stocka). With taxes, the return to capital is only (1 –τ) MPK fb). Setting the return equal to the user cost gives:►c). Tax-adjusted user cost of capital is __________________.d). An increase in τ ______________ the tax-adjusted user cost and____________ the desired capital stock.e). In reality, there are complications to the tax-adjusted user cost(1) We assumed that firm revenues were _____________.(i) In reality, _____________, not revenues, are taxed.(ii) So depreciation allowances reduce the tax paid by firms,because they _____________ profits.(2) Investment tax credits reduce taxes when firms make_________investments.(3) Summary measure: the effective tax rate is the tax rate onfirm revenue that would have the same effect on the desiredcapital stock as do the actual provisions of the tax code.D. From the desired capital stock to investment1). The capital stock changes from two opposing channels:a). New capital ____________ the capital stock; this is __________investment.b). The capital stock depreciates, which _________ the capital stockGross Investment – Depreciation = Net Investment►where I is gross investment and net investment equals the change inthe capital stock.2). Rewriting the equation gives:►a). If firms can change their capital stocks in one period, then thedesired capital stock (K*) = K t+1b). So I t= K* – K t + dK tc). Thus investment has two parts:(i) Desired net increase in capital stock over the year (K*–K t)(ii) Investment needed to replace depreciated capital (dK t)3). Lags and investmenta). Some capital can be constructed easily, but other capitalmay take years to put in place.b). So investment needed to reach the desired capital stockmay be spread out over several years.E. Investment in inventories and housing▪ Marginal product of capital and user cost also apply, as with equipment and structures.▪A firm’s inventories are ____________________, ____________________and ________________________. It is the most volatile component of investment spending.▪ Residential investment is the construction of _______________ or________________________________.3.Goods Market EquilibriumA. Adjusting real interest rate brings the goods market to equilibriumThe real interest rate is the key to bring the quantity of goods supplied and demanded into balance.1). Goods market equilibrium condition: __________________________2). It differs from income-expenditure identity, as good market equilibriumcondition need __________ hold; undesired goods may be produced, sogoods market won’t be in equilibrium3). Alternative representation: since S d= Y – C d– G,►B. The saving-investment diagram1). Plot S d vs. I dS d: ____________ sloping—higher real interest rate raises desired S dI d: __________________ sloping – higher real interest rate increasesthe user cost of capitalrS d ,I d2). Equilibrium where _________________3). How to reach equilibrium? Adjustment of r4). Shifts of the saving curvea). Saving curve shifts right due to:(i).(ii).(iii).(iv).(v).b). Example: Temporary increase in government purchasesc). Result of lower savings: higher r, causing crowding out of I5). Shifts of the investment curvea). Investment curve shifts right due to:(i).(ii).b). Example: an innovation or economic reform raises MPK fc). Result of increased investment: higher r, higher S and I。

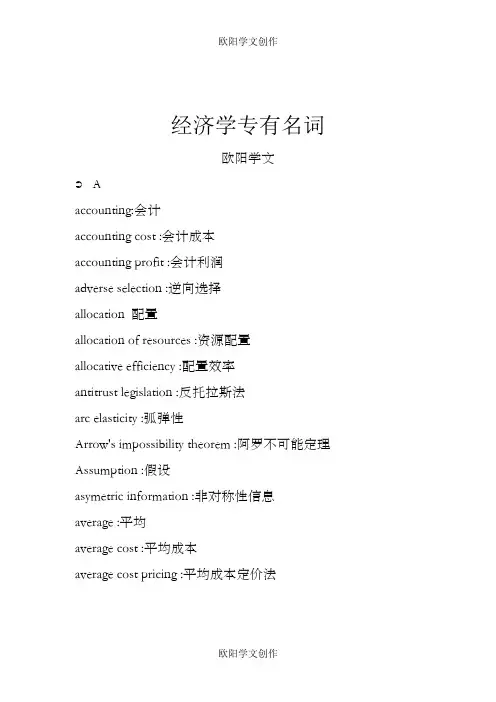

经济学专有名词欧阳学文Aaccounting:会计accounting cost :会计成本accounting profit :会计利润adverse selection :逆向选择allocation 配置allocation of resources :资源配置allocative efficiency :配置效率antitrust legislation :反托拉斯法arc elasticity :弧弹性Arrow's impossibility theorem :阿罗不可能定理Assumption :假设asymetric information :非对称性信息average :平均average cost :平均成本average cost pricing :平均成本定价法average fixed cost :平均固定成本average product of capital :资本平均产量average product of labour :劳动平均产量average revenue :平均收益average total cost :平均总成本average variable cost :平均可变成本Bbarriers to entry :进入壁垒base year :基年bilateral monopoly :双边垄断benefit :收益black market :黑市bliss point :极乐点boundary point :边界点break even point :收支相抵点budget :预算budget constraint :预算约束budget line :预算线budget set 预算集Ccapital :资本capital stock :资本存量capital output ratio :资本产出比率capitalism :资本主义cardinal utility theory :基数效用论cartel :卡特尔ceteris puribus assumption :“其他条件不变”的假设ceteris puribus demand curve :其他因素不变的需求曲线Chamberlin model :张伯伦模型change in demand :需求变化change in quantity demanded :需求量变化change in quantity supplied :供给量变化change in supply :供给变化choice :选择closed set :闭集Coase theorem :科斯定理Cobb—Douglas production function :柯布--道格拉斯生产函数cobweb model :蛛网模型collective bargaining :集体协议工资collusion :合谋command economy :指令经济commodity :商品commodity combination :商品组合commodity market :商品市场commodity space :商品空间common property :公用财产comparative static analysis :比较静态分析compensated budget line :补偿预算线compensated demand function :补偿需求函数compensation principles :补偿原则compensating variation in income :收入补偿变量competition :竞争competitive market :竞争性市场complement goods :互补品complete information :完全信息completeness :完备性condition for efficiency in exchange :交换的最优条件condition for efficiency in production :生产的最优条件concave :凹concave function :凹函数concave preference :凹偏好consistence :一致性constant cost industry :成本不变产业constant returns to scale :规模报酬不变constraints :约束consumer :消费者consumer behavior :消费者行为consumer choice :消费者选择consumer equilibrium :消费者均衡consumer optimization :消费者优化consumer preference :消费者偏好consumer surplus :消费者剩余consumer theory :消费者理论consumption :消费consumption bundle :消费束consumption combination :消费组合consumption possibility curve :消费可能曲线consumption possibility frontier :消费可能性前沿consumption set :消费集consumption space :消费空间continuity :连续性continuous function :连续函数contract curve :契约曲线convex :凸convex function :凸函数convex preference :凸偏好convex set :凸集corporatlon :公司cost :成本cost benefit analysis :成本收益分cost function :成本函数cost minimization :成本极小化Cournot equilihrium :古诺均衡Cournot model :古诺模型Cross—price elasticity :交叉价格弹性Ddead—weights loss :重负损失decreasing cost industry :成本递减产业decreasing returns to scale :规模报酬递减deduction :演绎法demand :需求demand curve :需求曲线demand elasticity :需求弹性demand function :需求函数demand price :需求价格demand schedule :需求表depreciation :折旧derivative :导数derive demand :派生需求difference equation :差分方程differential equation :微分方程differentiated good :差异商品differentiated oligoply :差异寡头diminishing marginal substitution :边际替代率递减diminishing marginal return :收益递减diminishing marginal utility :边际效用递减direct approach :直接法direct taxes :直接税discounting :贴税、折扣diseconomies of scale :规模不经济disequilibrium :非均衡distribution :分配division of labour :劳动分工distribution theory of marginal productivity :边际生产率分配论duoupoly :双头垄断、双寡duality :对偶durable goods :耐用品dynamic analysis :动态分析dynamic models :动态模型EEconomic agents :经济行为者economic cost :经济成本economic efficiency :经济效率economic goods :经济物品economic man :经济人economic mode :经济模型economic profit :经济利润economic region of production :生产的经济区域economic regulation :经济调节economic rent :经济租金exchange :交换economics :经济学exchange efficiency :交换效率economy :经济exchange contract curve :交换契约曲线economy of scale :规模经济Edgeworth box diagram :埃奇沃思图exclusion :排斥性、排他性Edgeworth contract curve :埃奇沃思契约线Edgeworth model :埃奇沃思模型efficiency :效率,效益efficiency parameter :效率参数elasticity :弹性elasticity of substitution :替代弹性endogenous variable :内生变量endowment :禀赋endowment of resources :资源禀赋Engel curve :恩格尔曲线entrepreneur :企业家entrepreneurship :企业家才能entry barriers :进入壁垒entry/exit decision :进出决策envolope curve :包络线equilibrium :均衡equilibrium condition :均衡条件equilibrium price :均衡价格equilibrium quantity :均衡产量eqity :公平equivalent variation in income :收入等价变量excess—capacity theorem :过度生产能力定理excess supply :过度供给exchange :交换exchange contract curve :交换契约曲线exclusion :排斥性、排他性exclusion principle :排他性原则existence :存在性existence of general equilibrium :总体均衡的存在性exogenous variables :外生变量expansion paths :扩展径expectation :期望expected utility :期望效用expected value :期望值expenditure :支出explicit cost :显性成本external benefit :外部收益external cost :外部成本external economy :外部经济external diseconomy :外部不经济externalities :外部性FFactor :要素factor demand :要素需求factor market :要素市场factors of production :生产要素factor substitution :要素替代factor supply :要素供给fallacy of composition :合成谬误final goods :最终产品firm :企业firms’demand curve for labor :企业劳动需求曲线firm supply curve :企业供给曲线first-degree price discrimination :第一级价格歧视first—order condition :一阶条件fixed costs :固定成本fixed input :固定投入fixed proportions production function :固定比例的生产函数flow :流量fluctuation :波动for whom to produce :为谁生产free entry :自由进入free goods :自由品,免费品free mobility of resources :资源自由流动free rider :搭便车,免费搭车function :函数future value :未来值Ggame theory :对策论、博弈论general equilibrium :总体均衡general goods :一般商品Giffen goods :吉芬晶收入补偿需求曲线Giffen's Paradox :吉芬之谜Gini coefficient :吉尼系数goldenrule :黄金规则goods :货物government failure :政府失败government regulation :政府调控grand utility possibility curve :总效用可能曲线grand utility possibility frontier :总效用可能前沿Hheterogeneous product :异质产品Hicks—kaldor welfare criterion :希克斯一卡尔多福利标准homogeneity :齐次性homogeneous demand function :齐次需求函数homogeneous product :同质产品homogeneous production function :齐次生产函数horizontal summation :水平和household :家庭how to produce :如何生产human capital :人力资本hypothesis :假说Iidentity :恒等式imperfect competion :不完全竞争implicitcost :隐性成本income :收入income compensated demand curve :收入补偿需求曲线income constraint :收入约束income consumption curve :收入消费曲线income distribution :收入分配income effect :收入效应income elasticity of demand :需求收入弹性increasing cost industry :成本递增产业increasing returns to scale :规模报酬递增inefficiency :缺乏效率index number :指数indifference :无差异indifference curve :无差异曲线indifference map :无差异族indifference relation :无差异关系indifference set :无差异集indirect approach :间接法individual analysis :个量分析individual demand curve :个人需求曲线individual demand function :个人需求函数induced variable :引致变量induction :归纳法industry :产业industry equilibrium :产业均衡industry supply curve :产业供给曲线inelastic :缺乏弹性的inferior goods :劣品inflection point :拐点information :信息information cost :信息成本initial condition :初始条件initial endowment :初始禀赋innovation :创新input :投入input—output :投入—产出institution :制度institutional economics :制度经济学insurance :保险intercept :截距interest :利息interest rate :利息率intermediate goods :中间产品internatization of externalities :外部性内部化invention :发明inverse demand function :逆需求函数investment :投资invisible hand :看不见的手isocost line :等成本线,isoprofit curve :等利润曲线isoquant curve :等产量曲线isoquant map :等产量族Kkinded—demand curve :弯折的需求曲线Llabour :劳动labour demand :劳动需求labour supply :劳动供给labour theory of value :劳动价值论labour unions :工会laissez faire :自由放任Lagrangian function :拉格朗日函数Lagrangian multiplier :拉格朗乘数,land :土地law :法则law of demand and supply :供需法law of diminishing marginal utility :边际效用递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution :边际替代率递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of technical substitution :边际技术替代率law of increasing cost :成本递增法则law of one price :单一价格法则leader—follower model :领导者--跟随者模型least—cost combination of inputs :最低成本的投入组合leisure :闲暇Leontief production function :列昂节夫生产函数licenses :许可证linear demand function :线性需求函数linear homogeneity :线性齐次性linear homogeneous production function :线性齐次生产函数long run :长期long run average cost :长期平均成本long run equilibrium :长期均衡long run industry supply curve :长期产业供给曲线long run marginal cost :长期边际成本long run total cost :长期总成本Lorenz curve :洛伦兹曲线loss minimization :损失极小化1ump sum tax :一次性征税luxury :奢侈品Mmacroeconomics :宏观经济学marginal :边际的marginal benefit :边际收益marginal cost :边际成本marginal cost pricing :边际成本定价marginal cost of factor :边际要素成本marginal physical productivity :实际实物生产率marginal product :边际产量marginal product of capital :资本的边际产量marginal product of 1abour :劳动的边际产量marginal productivity :边际生产率marginal rate of substitution :边替代率marginal rate of transformation 边际转换率marginal returns :边际回报marginal revenue :边际收益marginal revenue product :边际收益产品marginal revolution :边际革命marginal social benefit :社会边际收益marginal social cost :社会边际成本marginal utility :边际效用marginal value products :边际价值产品market :市场market clearance :市场结清,市场洗清market demand :市场需求market economy :市场经济market equilibrium :市场均衡market failure :市场失败market mechanism :市场机制market structure :市场结构market separation :市场分割market regulation :市场调节market share :市场份额markup pricing :加减定价法Marshallian demand function :马歇尔需求函数maximization :极大化microeconomics :微观经济学minimum wage :最低工资misallocation of resources :资源误置mixed economy :混合经济model :模型money :货币monopolistic competition :垄断竞争monopolistic exploitation :垄断剥削monopoly :垄断,卖方垄断monopoly equilibrium :垄断均衡monopoly pricing :垄断定价monopoly regulation :垄断调控monopoly rents :垄断租金monopsony :买方垄断NNash equilibrium :纳什均衡Natural monopoly :自然垄断Natural resources :自然资源Necessary condition :必要条件necessities :必需品net demand :净需求nonconvex preference :非凸性偏好nonconvexity :非凸性nonexclusion :非排斥性nonlinear pricing :非线性定价nonrivalry :非对抗性nonprice competition :非价格竞争nonsatiation :非饱和性non--zero—sum game :非零和对策normal goods :正常品normal profit :正常利润normative economics :规范经济学Oobjective function :目标函数oligopoly :寡头垄断oligopoly market :寡头市场oligopoly model :寡头模型opportunity cost :机会成本optimal choice :最佳选择optimal consumption bundle :消费束perfect elasticity :完全有弹性optimal resource allocation :最佳资源配置optimal scale :最佳规模optimal solution :最优解optimization :优化ordering of optimization(social) preference :(社会)偏好排序ordinal utility :序数效用ordinary goods :一般品output :产量、产出output elasticity :产出弹性output maximization 产出极大化Pparameter :参数Pareto criterion :帕累托标准Pareto efficiency :帕累托效率Pareto improvement :帕累托改进Pareto optimality :帕累托优化Pareto set :帕累托集partial derivative :偏导数partial equilibrium :局部均衡patent :专利pay off matrix :收益矩阵、支付矩阵perceived demand curve :感觉到的需求曲线perfect competition :完全竞争perfect complement :完全互补品perfect monopoly :完全垄断perfect price discrimination :完全价格歧视perfect substitution :完全替代品perfect inelasticity :完全无弹性perfectly elastic :完全有弹性perfectly inelastic :完全无弹性plant size :工厂规模point elasticity :点弹性post Hoc Fallacy :后此谬误prediction :预测preference :偏好preference relation :偏好关系present value :现值price :价格price adjustment model :价格调整模型price ceiling :最高限价price consumption curve :价格费曲线price control :价格管制price difference :价格差别price discrimination :价格歧视price elasticity of demand :需求价格弹性price elasticity of supply :供给价格弹性price floor :最低限价price maker :价格制定者price rigidity :价格刚性price seeker :价格搜求者price taker :价格接受者price tax :从价税private benefit :私人收益principal—agent issues :委托--代理问题private cost :私人成本private goods :私人用品private property :私人财产producer equilibrium :生产者均衡producer theory :生产者理论product :产品product transformation curve :产品转换曲线product differentiation :产品差异product group :产品集团production :生产production contract curve :生产契约曲线production efficiency :生产效率production function :生产函数production possibility curve :生产可能性曲线productivity :生产率productivity of capital :资本生产率productivity of labor :劳动生产率profit :利润profit function :利润函数profit maximization :利润极大化property rights :产权property rights economics :产权经济学proposition :定理proportional demand curve :成比例的需求曲线public benefits :公共收益public choice :公共选择public goods :公共商品pure competition :纯粹竞争rivalry :对抗性、竞争pure exchange :纯交换pure monopoly :纯粹垄断Qquantity—adjustment model :数量调整模型quantity tax :从量税quasi—rent :准租金Rrate of product transformation :产品转换率rationality :理性reaction function :反应函数regulation :调节,调控relative price 相对价格rent :租金rent control :规模报酬rent seeking :寻租rent seeking economics :寻租经济学resource :资源resource allocation :资源配置returns :报酬、回报returns to scale :规模报酬revealed preference :显示性偏好revenue :收益revenue curve :收益曲线revenue function :收益函数revenue maximization :收益极大化ridge line :脊线risk :风险Ssatiation :饱和,满足saving :储蓄scarcity :稀缺性law of scarcity :稀缺法则second—degree price discrimination :二级价格歧视second derivative :--阶导数second—order condition :二阶条件service :劳务set :集shadow prices :影子价格short—run :短期short—run cost curve :短期成本曲线short—run equilibrium :短期均衡short—run supply curve :短期供给曲线shut down decision :关闭决策shortage 短缺shut down point :关闭点single price monopoly :单一定价垄断slope :斜率social benefit :社会收益social cost :社会成本social indifference curve :社会无差异曲线social preference :社会偏好social security :社会保障social welfare function :社会福利函数socialism :社会主义solution :解space :空间stability :稳定性stable equilibrium :稳定的均衡Stackelberg model :斯塔克尔贝格模型static analysis :静态分析stock :存量stock market :股票市场strategy :策略subsidy :津贴substitutes :替代品substitution effect :替代效应substitution parameter :替代参数sufficient condition :充分条件supply :供给supply curve :供给曲线supply function :供给函数supply schedule :供给表Sweezy model :斯威齐模型symmetry :对称性symmetry of information :信息对称Ttangency :相切taste :兴致technical efficiency :技术效率technological constraints ;技术约束technological progress :技术进步technology :技术third—degree price discrimination :第三级价格歧视total cost :总成本total effect :总效应total expenditure :总支出total fixed cost :总固定成本total product :总产量total revenue :总收益total utility :总效用total variable cost :总可变成本traditional economy :传统经济transitivity :传递性transaction cost :交易费用Uuncertainty :不确定性uniqueness :唯一性unit elasticity :单位弹性unstable equilibrium :不稳定均衡utility :效用utility function :效用函数utility index :效用指数utility maximization :效用极大化utility possibility curve :效用可能性曲线utility possibility frontier :效用可能性前沿Vvalue :价值value judge :价值判断value of marginal product :边际产量价值variable cost :可变成本variable input :可变投入variables :变量vector :向量visible hand :看得见的手vulgur economics :庸俗经济学Wwage :工资wage rate :工资率Walras general equilibrium :瓦尔拉斯总体均衡Walras's law :瓦尔拉斯法则Wants :需要Welfare criterion :福利标准Welfare economics :福利经学Welfare loss triangle :福利损失三角形welfare maximization :福利极大化Zzero cost :零成本zero elasticity :零弹性zero homogeneity :零阶齐次性zero economic profit :零利润。

美国有三种税基:个人所得,财产和消费.Income, wealth and consumption are the three bases that can be taxed in the United States. 税收的三种主要来源都会影响投资决策.All three major sources of taxation may have effect on investment decisions.对投资影响最大的税收是联邦所得税,它对投资收入征税,包括利息,股本和资本收益.The tax that has the greatest impact on investments is the federal income tax, which is taxed on investment income including interest and dividends, and capital gains.但是,财产税,如联邦不动产遗产税或房地产财产税,也是个人投资者在一定情况下需要重点考虑的.However, taxes on wealth, such as the federal estate tax or property tax on real estate, can be also very important consideration for individual investors in specific circumstances.The least important general tax from an investment viewpoint is the sales tax.从投资角度看,最不重要的普通税是销售税。

购买证券或开办储蓄账户及购买共同基金股份无需缴纳销售税。

The purchase of securities, the opening of a savings account or the acquisition of shares in a mutual fund is not subject to sales tax.不过在某些地方,像购买黄金古玩等收藏品也要缴纳销售税。

CFA Economic学习笔记分享想要通过CFA考试,抓紧备考是必不可少的,掌握重点和难点也很重要,现在,小编给大家分享一些CFA考试的笔记经验,祝愿大家都能顺利通过考试!微观弹性1、当商品占收入比重小时,价格弹性也小。

2、需求的收入弹性(当收入变化时,需求的变化)necessities:positiveand low elasticity, the other way is luxuries3、供给的价格弹性:当价格与总收益的变动是反向时,处于高弹性区域。

效率与公平Public goods:公共产品会因为收益人不需负担其产出的成本而导致生产者的不积极,生产不足。

Common resource:公共资源的使用会因为极低的成本而造成过度使用。

效率与公平的两种思路:1、资源分配结果的公平:Utilitarianism2、资源分配规则的公平:Symmetry principle市场行为组织生产1、机会成本包括:Explicit cost、Implicit costa) Implicit cost 包括:i. Implicit rental rate(资本的隐性租金率):economic depreciation、foregoneinterestii. Normal profit: 企业家才能的机会成本2、经济利益economic profit(not accountingprofit):总收益减去机会成本技术、经济效率:1、 Technological efficiency:较少的特定投入量得到产出(有一种生产因素的量变少了就行)2、 Economic efficiency:较少的成本得到产出(总成本变少才算Economic efficiency)雇主雇员问题:Three methods to reduce the principal-agent problemwnership, incentive pay, long-term contracts.商业组织形式:Three types of business organization:proprietorship/partnership/corporation市场集中度:最大的4家市场占有率总和(40%-60%)、最大的50家市场占有率平方和(1000-1800)经济活动的合作方式:Market coordination , Firmcoordination(低交易成本、规模经济、范围经济、团队经济)产出和成本MP最大点对应MC最小点MP交AP于AP最大点,对应着,MC交AVC于AVC最小点。

ap宏观经济学知识点【篇一:ap宏观经济学知识点】开考科目:详情查看请点击:【】【新航道提供免费服务,优先抢考位,如需代报名,详情查看:,或者在线咨询我们的老师】六、 ap经济学考试中的十三大要点1 、fundamentals of economic analysisscarce resourcesproduction possibilitiesfunctions of economic systems2、 demand, supply, market equilibrium, and welfare analysis demandsupplymarket equilibriumwelfare analysis3、elasticity, microeconomic policy, and consumer theory elasticitymicroeconomic policy and applications of elasticity consumer choice4、the firm, profit, and the costs of productionfirms, opportunity costs, and profitsproduction and cost5、market structures, perfect competition, monopoly, and things betweenperfect competitionmonopolymonopolistic competitionoligopoly6、factor marketsfactor demandleast-cost hiring of multiple inputsfactor supply and market equilibriumimperfect competition in product and factor markets7、public goods, externalities, and the role of government public goods and spillover benefitspollution and spillover costsincome distribution and tax structures8、 macroeconomic measures of performancethe circular flow modelaccounting for output and incomeinflation and the consumer price indexunemployment9、 consumption, saving, investment, and the multiplier consumption and savinginvestmentthe multiplier effect10、aggregate demand and aggregate supplyaggregate demandaggregate supplymacroeconomic equilibriumthe trade-off between inflation and unemployment11、fiscal policy, economic growth, and productivity expansionary and contractionary fiscal policydifficulties of fiscal policyeconomic growth and productivity12、money, banking, and monetary policymoney and financial assetsfractional reserve banking and money creationmonetary policy13、 international tradecomparative advantage and gains from tradebalance of paymentsforeign exchange ratestrade barriers【篇二:ap宏观经济学知识点】阅读,只需一秒。

英语词汇复习经济类经济类英语词汇是学习经济学的基础,掌握这些词汇对于理解经济领域相关内容非常重要。

本文将介绍一些常用的经济类英语词汇,帮助读者进行词汇复习。

一、货币与金融词汇1. Currency (n.) - 货币Currency refers to a system of money in general use in a particular country or region. It is used as a medium of exchange in the economy.2. Inflation (n.) - 通货膨胀Inflation refers to the general increase in prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time. It is usually measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI).3. Deflation (n.) - 通货紧缩Deflation is the opposite of inflation. It refers to a decrease in the general price level of goods and services, resulting in the increase in purchasing power of money.4. Interest rate (n.) - 利率Interest rate is the percentage of the total loan amount charged as interest by a lender to a borrower. It is an important tool used by central banks to control inflation and stimulate economic growth.5. Exchange rate (n.) - 汇率Exchange rate is the value of one currency in terms of another currency. It determines the amount of one currency needed to purchase a given amount of another currency.二、市场与贸易词汇1. Market (n.) - 市场Market refers to the interaction between buyers and sellers of goods and services. It can be a physical place or a virtual platform where products are exchanged.2. Demand (n.) - 需求Demand refers to the desire, ability, and willingness of consumers to buy a product or service. It is influenced by factors such as price, income, and consumer preferences.3. Supply (n.) - 供应Supply refers to the quantity of a product or service that producers are willing and able to provide in the market. It is influenced by factors such as production costs, technology, and government regulations.4. Trade (n.) - 贸易Trade refers to the buying and selling of goods and services between countries or regions. International trade plays a crucial role in the global economy.5. Tariff (n.) - 关税Tariff is a tax imposed on imported goods and services. It is used to protect domestic industries and regulate trade between countries.三、就业与劳动市场词汇1. Employment (n.) - 就业Employment refers to the state of having paid work. It is an essential aspect of economic development and social well-being.2. Unemployment (n.) - 失业Unemployment refers to the condition of being without a job but actively seeking employment. It is usually measured by the unemployment rate, which is the percentage of the labor force that is unemployed.3. Labor market (n.) - 劳动市场Labor market refers to the supply and demand for labor in an economy. It is where individuals and businesses interact to determine wages and employment opportunities.4. Minimum wage (n.) - 最低工资Minimum wage is the lowest hourly wage that employers are legally required to pay their employees. It is set by the government to ensure fair compensation for workers.5. Skills (n.) - 技能Skills refer to the abilities and knowledge acquired through education, training, and experience. They are essential for individuals to participate in the labor market and contribute to economic growth.总结:以上介绍了一些经济类英语词汇,这些词汇是经济学学习中的基础。

经济学词汇--中英文对照A--------------------------------------------------------------------------------accounting:会计accounting cost:会计成本accounting profit:会计利润adverse selection:逆向选择allocation配置allocation of resources:资源配置allocative efficiency:配置效率antitrust legislation:反托拉斯法arc elasticity:弧弹性Arrow's impossibility theorem:阿罗不可能定理Assumption:假设asymetric information:非对称性信息average:平均average cost:平均成本average cost pricing:平均成本定价法average fixed cost:平均固定成本average product of capital:资本平均产量average product of labour:劳动平均产量average revenue:平均收益average total cost:平均总成本average variable cost:平均可变成本B--------------------------------------------------------------------------------barriers to entry:进入壁垒base year:基年bilateral monopoly:双边垄断benefit:收益black market:黑市bliss point:极乐点boundary point:边界点break even point:收支相抵点budget:预算budget constraint:预算约束budget line:预算线budget set预算集C--------------------------------------------------------------------------------capital:资本capital stock:资本存量capital output ratio:资本产出比率capitalism:资本主义cardinal utility theory:基数效用论cartel:卡特尔ceteris puribus assumption:“其他条件不变”的假设ceteris puribus demand curve:其他因素不变的需求曲线Chamberlin model:张伯伦模型change in demand:需求变化change in quantity demanded:需求量变化change in quantity supplied:供给量变化change in supply:供给变化choice:选择closed set:闭集Coase theorem:科斯定理Cobb—Douglas production function:柯布--道格拉斯生产函数cobweb model:蛛网模型collective bargaining:集体协议工资collusion:合谋command economy:指令经济commodity:商品commodity combination:商品组合commodity market:商品市场commodity space:商品空间common property:公用财产comparative static analysis:比较静态分析compensated budget line:补偿预算线compensated demand function:补偿需求函数compensation principles:补偿原则compensating variation in income:收入补偿变量competition:竞争competitive market:竞争性市场complement goods:互补品complete information:完全信息completeness:完备性condition for efficiency in exchange:交换的最优条件condition for efficiency in production:生产的最优条件concave:凹concave function:凹函数concave preference:凹偏好consistence:一致性constant cost industry:成本不变产业constant returns to scale:规模报酬不变constraints:约束consumer:消费者consumer behavior:消费者行为consumer choice:消费者选择consumer equilibrium:消费者均衡consumer optimization:消费者优化consumer preference:消费者偏好consumer surplus:消费者剩余consumer theory:消费者理论consumption:消费consumption bundle:消费束consumption combination:消费组合consumption possibility curve:消费可能曲线consumption possibility frontier:消费可能性前沿consumption set:消费集consumption space:消费空间continuity:连续性continuous function:连续函数contract curve:契约曲线convex:凸convex function:凸函数convex preference:凸偏好convex set:凸集corporatlon:公司cost:成本cost benefit analysis:成本收益分cost function:成本函数cost minimization:成本极小化Cournot equilihrium:古诺均衡Cournot model:古诺模型Cross—price elasticity:交叉价格弹性D--------------------------------------------------------------------------------dead—weights loss:重负损失decreasing cost industry:成本递减产业decreasing returns to scale:规模报酬递减deduction:演绎法demand:需求demand curve:需求曲线demand elasticity:需求弹性demand function:需求函数demand price:需求价格demand schedule:需求表depreciation:折旧derivative:导数derive demand:派生需求difference equation:差分方程differential equation:微分方程differentiated good:差异商品differentiated oligoply:差异寡头diminishing marginal substitution:边际替代率递减diminishing marginal return:收益递减diminishing marginal utility:边际效用递减direct approach:直接法direct taxes:直接税discounting:贴税、折扣diseconomies of scale:规模不经济disequilibrium:非均衡distribution:分配division of labour:劳动分工distribution theory of marginal productivity:边际生产率分配论duoupoly:双头垄断、双寡duality:对偶durable goods:耐用品dynamic analysis:动态分析dynamic models:动态模型E--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Economic agents:经济行为者economic cost:经济成本economic efficiency:经济效率economic goods:经济物品economic man:经济人economic mode:经济模型economic profit:经济利润economic region of production:生产的经济区域economic regulation:经济调节economic rent:经济租金exchange:交换economics:经济学exchange efficiency:交换效率economy:经济exchange contract curve:交换契约曲线economy of scale:规模经济Edgeworth box diagram:埃奇沃思图exclusion:排斥性、排他性Edgeworth contract curve:埃奇沃思契约线Edgeworth model:埃奇沃思模型efficiency:效率,效益efficiency parameter:效率参数elasticity:弹性elasticity of substitution:替代弹性endogenous variable:内生变量endowment:禀赋endowment of resources:资源禀赋Engel curve:恩格尔曲线entrepreneur:企业家entrepreneurship:企业家才能entry barriers:进入壁垒entry/exit decision:进出决策envolope curve:包络线equilibrium:均衡equilibrium condition:均衡条件equilibrium price:均衡价格equilibrium quantity:均衡产量eqity:公平equivalent variation in income:收入等价变量excess—capacity theorem:过度生产能力定理excess supply:过度供给exchange:交换exchange contract curve:交换契约曲线exclusion:排斥性、排他性exclusion principle:排他性原则existence:存在性existence of general equilibrium:总体均衡的存在性exogenous variables:外生变量expansion paths:扩展径expectation:期望expected utility:期望效用expected value:期望值expenditure:支出explicit cost:显性成本external benefit:外部收益external cost:外部成本external economy:外部经济external diseconomy:外部不经济externalities:外部性F--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Factor:要素factor demand:要素需求factor market:要素市场factors of production:生产要素factor substitution:要素替代factor supply:要素供给fallacy of composition:合成谬误final goods:最终产品firm:企业firms’demand curve for labor:企业劳动需求曲线firm supply curve:企业供给曲线first-degree price discrimination:第一级价格歧视first—order condition:一阶条件fixed costs:固定成本fixed input:固定投入fixed proportions production function:固定比例的生产函数flow:流量fluctuation:波动for whom to produce:为谁生产free entry:自由进入free goods:自由品,免费品free mobility of resources:资源自由流动free rider:搭便车,免费搭车function:函数future value:未来值G--------------------------------------------------------------------------------game theory:对策论、博弈论general equilibrium:总体均衡general goods:一般商品Giffen goods:吉芬晶收入补偿需求曲线Giffen's Paradox:吉芬之谜Gini coefficient:吉尼系数goldenrule:黄金规则goods:货物government failure:政府失败government regulation:政府调控grand utility possibility curve:总效用可能曲线grand utility possibility frontier:总效用可能前沿H--------------------------------------------------------------------------------heterogeneous product:异质产品Hicks—kaldor welfare criterion:希克斯一卡尔多福利标准homogeneity:齐次性homogeneous demand function:齐次需求函数homogeneous product:同质产品homogeneous production function:齐次生产函数horizontal summation:水平和household:家庭how to produce:如何生产human capital:人力资本hypothesis:假说I--------------------------------------------------------------------------------identity:恒等式imperfect competion:不完全竞争implicitcost:隐性成本income:收入income compensated demand curve:收入补偿需求曲线income constraint:收入约束income consumption curve:收入消费曲线income distribution:收入分配income effect:收入效应income elasticity of demand:需求收入弹性increasing cost industry:成本递增产业increasing returns to scale:规模报酬递增inefficiency:缺乏效率index number:指数indifference:无差异indifference curve:无差异曲线indifference map:无差异族indifference relation:无差异关系indifference set:无差异集indirect approach:间接法individual analysis:个量分析individual demand curve:个人需求曲线individual demand function:个人需求函数induced variable:引致变量induction:归纳法industry:产业industry equilibrium:产业均衡industry supply curve:产业供给曲线inelastic:缺乏弹性的inferior goods:劣品inflection point:拐点information:信息information cost:信息成本initial condition:初始条件initial endowment:初始禀赋innovation:创新input:投入input—output:投入—产出institution:制度institutional economics:制度经济学insurance:保险intercept:截距interest:利息interest rate:利息率intermediate goods:中间产品internatization of externalities:外部性内部化invention:发明inverse demand function:逆需求函数investment:投资invisible hand:看不见的手isocost line:等成本线,isoprofit curve:等利润曲线isoquant curve:等产量曲线isoquant map:等产量族K--------------------------------------------------------------------------------kinded—demand curve:弯折的需求曲线L--------------------------------------------------------------------------------labour:劳动labour demand:劳动需求labour supply:劳动供给labour theory of value:劳动价值论labour unions:工会laissez faire:自由放任Lagrangian function:拉格朗日函数Lagrangian multiplier:拉格朗乘数,land:土地law:法则law of demand and supply:供需法law of diminishing marginal utility:边际效用递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of substitution:边际替代率递减法则law of diminishing marginal rate of technicalsubstitution:边际技术替代率law of increasing cost:成本递增法则law of one price:单一价格法则leader—follower model:领导者--跟随者模型least—cost combination of inputs:最低成本的投入组合leisure:闲暇Leontief production function:列昂节夫生产函数licenses:许可证linear demand function:线性需求函数linear homogeneity:线性齐次性linear homogeneous production function:线性齐次生产函数long run:长期long run average cost:长期平均成本long run equilibrium:长期均衡long run industry supply curve:长期产业供给曲线long run marginal cost:长期边际成本long run total cost:长期总成本Lorenz curve:洛伦兹曲线loss minimization:损失极小化1ump sum tax:一次性征税luxury:奢侈品M--------------------------------------------------------------------------------macroeconomics:宏观经济学marginal:边际的marginal benefit:边际收益marginal cost:边际成本marginal cost pricing:边际成本定价marginal cost of factor:边际要素成本marginal physical productivity:实际实物生产率marginal product:边际产量marginal product of capital:资本的边际产量marginal product of1abour:劳动的边际产量marginal productivity:边际生产率marginal rate of substitution:边替代率marginal rate of transformation边际转换率marginal returns:边际回报marginal revenue:边际收益marginal revenue product:边际收益产品marginal revolution:边际革命marginal social benefit:社会边际收益marginal social cost:社会边际成本marginal utility:边际效用marginal value products:边际价值产品market:市场market clearance:市场结清,市场洗清market demand:市场需求market economy:市场经济market equilibrium:市场均衡market failure:市场失败market mechanism:市场机制market structure:市场结构market separation:市场分割market regulation:市场调节market share:市场份额markup pricing:加减定价法Marshallian demand function:马歇尔需求函数maximization:极大化microeconomics:微观经济学minimum wage:最低工资misallocation of resources:资源误置mixed economy:混合经济model:模型money:货币monopolistic competition:垄断竞争monopolistic exploitation:垄断剥削monopoly:垄断,卖方垄断monopoly equilibrium:垄断均衡monopoly pricing:垄断定价monopoly regulation:垄断调控monopoly rents:垄断租金monopsony:买方垄断N--------------------------------------------------------------------------------Nash equilibrium:纳什均衡Natural monopoly:自然垄断Natural resources:自然资源Necessary condition:必要条件necessities:必需品net demand:净需求nonconvex preference:非凸性偏好nonconvexity:非凸性nonexclusion:非排斥性nonlinear pricing:非线性定价nonrivalry:非对抗性nonprice competition:非价格竞争nonsatiation:非饱和性non--zero—sum game:非零和对策normal goods:正常品normal profit:正常利润normative economics:规范经济学O--------------------------------------------------------------------------------objective function:目标函数oligopoly:寡头垄断oligopoly market:寡头市场oligopoly model:寡头模型opportunity cost:机会成本optimal choice:最佳选择optimal consumption bundle:消费束perfect elasticity:完全有弹性optimal resource allocation:最佳资源配置optimal scale:最佳规模optimal solution:最优解optimization:优化ordering of optimization(social)preference:(社会)偏好排序ordinal utility:序数效用ordinary goods:一般品output:产量、产出output elasticity:产出弹性output maximization产出极大化P--------------------------------------------------------------------------------parameter:参数Pareto criterion:帕累托标准Pareto efficiency:帕累托效率Pareto improvement:帕累托改进Pareto optimality:帕累托优化Pareto set:帕累托集partial derivative:偏导数partial equilibrium:局部均衡patent:专利pay off matrix:收益矩阵、支付矩阵perceived demand curve:感觉到的需求曲线perfect competition:完全竞争perfect complement:完全互补品perfect monopoly:完全垄断perfect price discrimination:完全价格歧视perfect substitution:完全替代品perfect inelasticity:完全无弹性perfectly elastic:完全有弹性perfectly inelastic:完全无弹性plant size:工厂规模point elasticity:点弹性post Hoc Fallacy:后此谬误prediction:预测preference:偏好preference relation:偏好关系present value:现值price:价格price adjustment model:价格调整模型price ceiling:最高限价price consumption curve:价格费曲线price control:价格管制price difference:价格差别price discrimination:价格歧视price elasticity of demand:需求价格弹性price elasticity of supply:供给价格弹性price floor:最低限价price maker:价格制定者price rigidity:价格刚性price seeker:价格搜求者price taker:价格接受者price tax:从价税private benefit:私人收益principal—agent issues:委托--代理问题private cost:私人成本private goods:私人用品private property:私人财产producer equilibrium:生产者均衡producer theory:生产者理论product:产品product transformation curve:产品转换曲线product differentiation:产品差异product group:产品集团production:生产production contract curve:生产契约曲线production efficiency:生产效率production function:生产函数production possibility curve:生产可能性曲线productivity:生产率productivity of capital:资本生产率productivity of labor:劳动生产率profit:利润profit function:利润函数profit maximization:利润极大化property rights:产权property rights economics:产权经济学proposition:定理proportional demand curve:成比例的需求曲线public benefits:公共收益public choice:公共选择public goods:公共商品pure competition:纯粹竞争rivalry:对抗性、竞争pure exchange:纯交换pure monopoly:纯粹垄断Q--------------------------------------------------------------------------------quantity—adjustment model:数量调整模型quantity tax:从量税quasi—rent:准租金R--------------------------------------------------------------------------------rate of product transformation:产品转换率rationality:理性reaction function:反应函数regulation:调节,调控relative price相对价格rent:租金rent control:规模报酬rent seeking:寻租rent seeking economics:寻租经济学resource:资源resource allocation:资源配置returns:报酬、回报returns to scale:规模报酬revealed preference:显示性偏好revenue:收益revenue curve:收益曲线revenue function:收益函数revenue maximization:收益极大化ridge line:脊线risk:风险S--------------------------------------------------------------------------------satiation:饱和,满足saving:储蓄scarcity:稀缺性law of scarcity:稀缺法则second—degree price discrimination:二级价格歧视second derivative:--阶导数second—order condition:二阶条件service:劳务set:集shadow prices:影子价格short—run:短期short—run cost curve:短期成本曲线short—run equilibrium:短期均衡short—run supply curve:短期供给曲线shut down decision:关闭决策shortage短缺shut down point:关闭点single price monopoly:单一定价垄断slope:斜率social benefit:社会收益social cost:社会成本social indifference curve:社会无差异曲线social preference:社会偏好social security:社会保障social welfare function:社会福利函数socialism:社会主义solution:解space:空间stability:稳定性stable equilibrium:稳定的均衡Stackelberg model:斯塔克尔贝格模型static analysis:静态分析stock:存量stock market:股票市场strategy:策略subsidy:津贴substitutes:替代品substitution effect:替代效应substitution parameter:替代参数sufficient condition:充分条件supply:供给supply curve:供给曲线supply function:供给函数supply schedule:供给表Sweezy model:斯威齐模型symmetry:对称性symmetry of information:信息对称T--------------------------------------------------------------------------------tangency:相切taste:兴致technical efficiency:技术效率technological constraints;技术约束technological progress:技术进步technology:技术third—degree price discrimination:第**价格歧视total cost:总成本total effect:总效应total expenditure:总支出total fixed cost:总固定成本total product:总产量total revenue:总收益total utility:总效用total variable cost:总可变成本traditional economy:传统经济transitivity:传递性transaction cost:交易费用U--------------------------------------------------------------------------------uncertainty:不确定性uniqueness:唯一性unit elasticity:单位弹性unstable equilibrium:不稳定均衡utility:效用utility function:效用函数utility index:效用指数utility maximization:效用极大化utility possibility curve:效用可能性曲线utility possibility frontier:效用可能性前沿V--------------------------------------------------------------------------------value:价值value judge:价值判断value of marginal product:边际产量价值variable cost:可变成本variable input:可变投入variables:变量vector:向量visible hand:看得见的手vulgur economics:庸俗经济学W--------------------------------------------------------------------------------wage:工资wage rate:工资率Walras general equilibrium:瓦尔拉斯总体均衡Walras's law:瓦尔拉斯法则Wants:需要Welfare criterion:福利标准Welfare economics:福利经学Welfare loss triangle:福利损失三角形welfare maximization:福利极大化Z--------------------------------------------------------------------------------zero cost:零成本zero elasticity:零弹性zero homogeneity:零阶齐次性zero economic profit:零利润。