Diversification in substrate usage by glutathione synthetases from soya bean (Glycine max), wheat (T

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:447.98 KB

- 文档页数:8

植物的进化过程英语作文Title: The Evolutionary Journey of Plants。

Plants, the silent architects of our terrestrial ecosystems, have undergone a remarkable evolutionary journey over millions of years, adapting to diverse environments and shaping the world around us. From their humble beginnings as simple aquatic organisms to the complex and diverse forms we see today, the story of plant evolution is a testament to nature's ingenuity and resilience.The journey of plant evolution begins in the ancient oceans, where primitive algae first emerged around 1.2 billion years ago. These early photosynthetic organismslaid the foundation for all future plant life, harnessing the power of sunlight to convert carbon dioxide and water into energy. Over time, some algae developed specialized structures, such as multicellular filaments and reproductive organs, paving the way for the transition fromwater to land.Around 500 million years ago, the first plants began to colonize the barren landscapes of the Earth. These pioneering species faced numerous challenges, including limited access to water and the absence of a supportivesoil substrate. To overcome these obstacles, early plants evolved a range of adaptations, including the development of root-like structures to anchor themselves in the soil and absorb water and nutrients.One of the most significant milestones in plant evolution was the emergence of vascular tissue, which allowed for the efficient transport of water and nutrients throughout the plant's tissues. This innovation enabled plants to grow taller and more complex, giving rise to the diverse array of ferns, horsetails, and club mosses that dominated the Earth's surface during the Devonian period.The colonization of land by plants had far-reaching consequences for the planet's ecosystems. By photosynthesizing and releasing oxygen as a byproduct,plants played a crucial role in shaping the Earth's atmosphere and making it habitable for other forms of life. Additionally, the development of root systems helped to stabilize soil and prevent erosion, paving the way for the establishment of more complex terrestrial ecosystems.As plants continued to evolve, they diversified into a myriad of forms, from towering trees to delicate flowers. Key innovations, such as the evolution of seeds and flowers, allowed plants to reproduce more efficiently and adapt to a wide range of ecological niches. The co-evolution of plants and pollinators, such as insects and birds, further fueled the diversification of plant species, leading to the rich tapestry of biodiversity that we see today.In more recent times, human activities have had a profound impact on plant evolution. The domestication of crops and the spread of agriculture have led to the widespread cultivation of certain plant species, while deforestation and habitat destruction have threatened the survival of many others. In response to these challenges, scientists are increasingly turning to techniques such asgenetic engineering and conservation efforts to safeguard the future of plant diversity.In conclusion, the evolution of plants is a remarkable saga of adaptation and innovation that has shaped the world we live in today. From their humble origins in the ancient oceans to their conquest of the terrestrial realm, plants have transformed barren landscapes into lush forests and verdant meadows. As we continue to unravel the mysteries of plant evolution, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate web of life that sustains us all.。

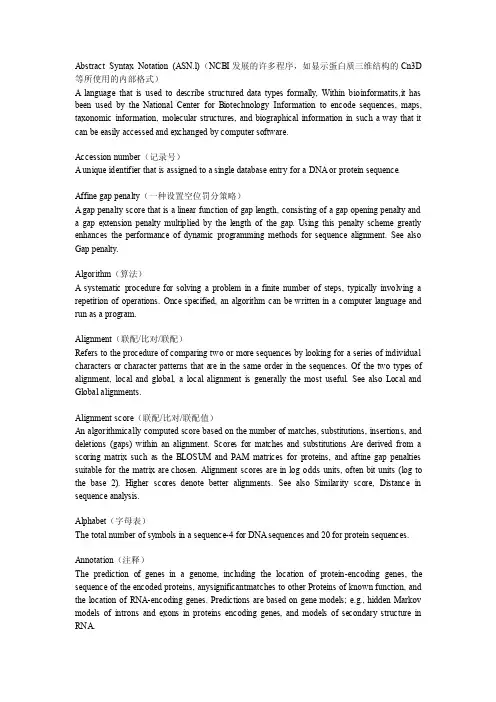

生物信息学主要英文术语及释义生物信息学主要英文术语及释义Abstract Abstract Syntax Syntax Syntax Notation Notation Notation (ASN.l)(ASN.l)(NCBI 发展的许多程序,如显示蛋白质三维结构的Cn3D等所使用的内部格式)等所使用的内部格式) A A language language language that that that is is is used used used to to to describe describe describe structured structured structured data data data types types types formally, formally, formally, Within Within Within bioinformatits,it bioinformatits,it bioinformatits,it has has been been used used used by by by the the the National National National Center Center Center for for for Biotechnology Biotechnology Biotechnology Information Information Information to to to encode encode encode sequences, sequences, sequences, maps, maps, taxonomic information, molecular structures, and biographical information in such a way that it can be easily accessed and exchanged by computer software. Accession number (记录号)(记录号)A unique identifier that is assigned to a single database entry for a DNA or protein sequence. Affine gap penalty (一种设置空位罚分策略)(一种设置空位罚分策略)(一种设置空位罚分策略) A gap penalty score that is a linear function of gap length, consisting of a gap opening penalty and a a gap gap gap extension extension extension penalty penalty penalty multiplied multiplied multiplied by by by the the the length length length of of of the the the gap. gap. gap. Using Using Using this this this penalty penalty penalty scheme scheme scheme greatly greatly enhances enhances the the the performance performance performance of of of dynamic dynamic dynamic programming programming programming methods methods methods for for for sequence sequence sequence alignment. alignment. alignment. See See See also also Gap penalty. Algorithm (算法)(算法)A A systematic systematic systematic procedure procedure procedure for solving for solving a a problem problem problem in in in a a a finite finite finite number number number of of of steps, steps, steps, typically typically typically involving involving involving a a repetition of operations. Once specified, an algorithm can be written in a computer language and run as a program. Alignment (联配/比对/联配)联配)Refers to the procedure of comparing two or more sequences by looking for a series of individual characters or character patterns that are in the same order in the sequences. Of the two types of alignment, alignment, local local local and and and global, global, global, a a a local local local alignment alignment alignment is is is generally generally generally the the the most most most useful. useful. useful. See See See also also also Local Local Local and and Global alignments. Alignment score (联配/比对/联配值)联配值)An algorithmically computed score based on the number of matches, substitutions, insertions, and deletions deletions (gaps) (gaps) (gaps) within within within an an an alignment. alignment. alignment. Scores Scores Scores for for for matches matches matches and and and substitutions substitutions substitutions Are Are Are derived derived derived from from from a a scoring scoring matrix matrix matrix such such such as as as the the the BLOSUM BLOSUM BLOSUM and and and P AM P AM matrices matrices matrices for for for proteins, proteins, proteins, and and and aftine aftine aftine gap gap gap penalties penalties suitable for the matrix are chosen. Alignment scores are in log odds units, often bit units (log to the the base base base 2). 2). 2). Higher Higher Higher scores scores scores denote denote denote better better better alignments. alignments. alignments. See See See also also also Similarity Similarity Similarity score, score, score, Distance Distance Distance in in sequence analysis. Alphabet (字母表)(字母表)The total number of symbols in a sequence-4 for DNA sequences and 20 for protein sequences. Annotation (注释)(注释)The The prediction prediction prediction of of of genes genes genes in in in a a a genome, genome, genome, including including including the the the location location location of of of protein-encoding protein-encoding protein-encoding genes, genes, genes, the the sequence of the encoded proteins, anysignificantmatches to other Proteins of known function, and the location of RNA-encoding genes. Predictions are based on gene models; e.g., hidden Markov models models of of of introns introns introns and and and exons exons exons in in in proteins proteins proteins encoding encoding encoding genes, genes, genes, and and and models models models of of of secondary secondary secondary structure structure structure in in RNA. Anonymous FTP (匿名FTP )When a FTP service allows anyone to log in, it is said to provide anonymous FTP ser-vice. A user can can log log log in in in to to to an an an anonymous anonymous anonymous FTP FTP FTP server server server by by by typing typing typing anonymous anonymous anonymous as as the the user name user name and and his E-mail his E-mail address as a password. Most Web browsers now negotiate anonymous FTP logon without asking the user for a user name and password. See also FTP. ASCII The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) encodes unaccented letters a-z, A-Z, A-Z, the the the numbers numbers numbers O-9, O-9, O-9, most most most punctuation punctuation punctuation marks, marks, marks, space, space, space, and and and a a a set set set of of of control control control characters characters characters such such such as as carriage carriage return return return and and and tab. tab. tab. ASCII ASCII ASCII specifies specifies specifies 128 128 128 characters characters characters that that that are are are mapped mapped mapped to to to the the the values values values O-127. O-127. ASCII ASCII tiles tiles tiles are are are commonly commonly commonly called called called plain plain plain text, text, text, meaning meaning meaning that that that they they they only only only encode encode encode text text text without without without extra extra markup. BAC clone (细菌人工染色体克隆)(细菌人工染色体克隆)Bacterial Bacterial artificial artificial artificial chromosome chromosome chromosome vector vector vector carrying carrying carrying a a a genomic genomic genomic DNA DNA DNA insert, insert, insert, typically typically typically 100100100––200 200 kb. kb. Most of the large-insert clones sequenced in the project were BAC clones. Back-propagation (反向传输)(反向传输)When training feed-forward neural networks, a back-propagation algorithm can be used to modify the network weights. After each training input pattern is fed through the network, the network’s output output is is is compared compared compared with with with the the the desired desired desired output output output and and and the the the amount amount amount of of of error error error is is is calculated. calculated. calculated. This This This error error error is is back-propagated through the network by using an error function to correct the network weights. See also Feed-forward neural network. Baum-Welch algorithm (Baum-Welch 算法)算法)An expectation maximization algorithm that is used to train hidden Markov models. Baye ’s rule (贝叶斯法则)(贝叶斯法则)Forms Forms the the the basis basis basis of of of conditional conditional conditional probability probability probability by by by calculating calculating calculating the the the likelihood likelihood likelihood of of of an an an event event event occurring occurring based on the history of the event and relevant background information. In terms of two parameters A and B, the theorem is stated in an equation: The condition-al probability of A, given B, P(AIB), is is equal equal equal to to to the the the probability probability probability of of of A, P(A), A, P(A), times times the the the conditional conditional conditional probability probability probability of of of B, B, B, given given given A, P(BIA), A, P(BIA), divided by the probability of B, P(B). P(A) is the historical or prior distribution value of A, P(BIA) is a new prediction for B for a particular value of A, and P(B) is the sum of the newly predicted values for B. P(AIB) is a posterior probability, representing a new prediction for A given the prior knowledge of A and the newly discovered relationships between A and B. Bayesian analysis (贝叶斯分析)(贝叶斯分析)A A statistical statistical statistical procedure procedure procedure used used used to to to estimate estimate estimate parameters parameters parameters of of of an an an underlyingdistribution underlyingdistribution underlyingdistribution based based based on on on an an observed distribution. See a lso Baye’s rule.Biochips (生物芯片)(生物芯片)Miniaturized arrays of large numbers of molecular substrates, often oligonucleotides, in a defined pattern. They are also called DNA microarrays and microchips. Bioinformatics (生物信息学)(生物信息学)The merger of biotechnology and information technology with the goal of revealing new insights and and principles principles principles in in in biology. biology. biology. /The /The /The discipline discipline discipline of of of obtaining obtaining obtaining information information information about about about genomic genomic genomic or or or protein protein sequence sequence data. data. data. This This This may may may involve involve involve similarity similarity similarity searches searches searches of of of databases, databases, databases, comparing comparing comparing your your your unidentified unidentified sequence sequence to to to the the the sequences sequences sequences in in in a a a database, database, database, or or or making making making predictions predictions predictions about about about the the the sequence sequence sequence based based based on on current current knowledge knowledge knowledge of of of similar similar similar sequences. sequences. sequences. Databases Databases Databases are are are frequently frequently frequently made made made publically publically publically available available through the Internet, or locally at your institution. Bit score (二进制值/ Bit 值)值)The value S' is derived from the raw alignment score S in which the statistical properties of the scoring system used have been taken into account. Because bit scores have been normalized with respect respect to to to the the the scoring scoring scoring system, system, system, they they they can can can be be be used used used to to to compare compare compare alignment alignment alignment scores scores scores from from from different different searches. Bit units From information theory, a bit denotes the amount of information required to distinguish between two two equally equally equally likely likely likely possibilities. possibilities. possibilities. The The The number number number of of of bits bits bits of of of information, information, information, AJ, AJ, AJ, required required required to to to convey convey convey a a message that has A4 possibilities is log2 M = N bits. BLAST (基本局部联配搜索工具,一种主要数据库搜索程序)(基本局部联配搜索工具,一种主要数据库搜索程序)Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. A set of programs, used to perform fast similarity searches. Nucleotide sequences can be compared with nucleotide sequences in a database using BLASTN, for for example. example. example. Complex Complex Complex statistics statistics statistics are are are applied applied applied to to to judge judge judge the the the significance significance significance of of of each each each match. match. match. Reported Reported sequences may be homologous to, or related to the query sequence. The BLASTP program is used to search a protein database for a match against a query protein sequence. There are several other flavours of BLAST. BLAST2 is a newer release of BLAST. Allows for insertions or deletions in the sequences being aligned. Gapped alignments may be more biologically significant. Block (蛋白质家族中保守区域的组块)(蛋白质家族中保守区域的组块)Conserved Conserved ungapped ungapped ungapped patterns patterns patterns approximately approximately approximately 3-60 3-60 3-60 amino amino amino acids acids acids in in in length length length in in in a a a set set set of of of related related proteins. BLOSUM matrices (模块替换矩阵,一种主要替换矩阵)(模块替换矩阵,一种主要替换矩阵)An alternative to PAM tables, BLOSUM tables were derived using local multiple alignments of more distantly related sequences than were used for the PAM matrix. These are used to assess the similarity of sequences when performing alignments. Boltzmann distribution (Boltzmann 分布)分布)Describes Describes the the the number number number of of of molecules molecules molecules that that that have have have energies energies energies above above above a a a certain certain certain level, level, level, based based based on on on the the Boltzmann gas constant and the absolute temperature.Boltzmann probability function(Boltzmann 概率函数) See Boltzmann distribution. Bootstrap analysis A method for testing how well a particular data set fits a model. For example, the validity of the branch branch arrangement arrangement arrangement in in in a a a predicted predicted predicted phylogenetic phylogenetic phylogenetic tree tree tree can can can be be be tested tested tested by by by resampling resampling resampling columns columns columns in in in a a multiple multiple sequence sequence sequence alignment alignment alignment to to to create create create many many many new new new alignments. alignments. alignments. The The The appearance appearance appearance of of of a a a particular particular branch in trees generated from these resampled sequences can then be measured. Alternatively, a sequence sequence may may may be be be left left left out out out of of of an an an analysis analysis analysis to to to deter-mine deter-mine deter-mine how how how much much much the the the sequence sequence sequence influences influences influences the the results of an analysis. Branch length (分支长度)(分支长度)In sequence analysis, the number of sequence changes along a particular branch of a phylogenetic tree. CDS or cds (编码序列)(编码序列)(编码序列) Coding sequence. Chebyshe, d inequality The probability that a random variable exceeds its mean is less than or equal to the square of 1 over the number of standard deviations from the mean. Clone (克隆)(克隆)Population of identical cells or molecules (e.g. DNA), derived from a single ancestor. Cloning V ector (克隆载体)(克隆载体)A molecule that carries a foreign gene into a host, and allows/facilitates the multiplication of that gene in a host. When sequencing a gene that has been cloned using a cloning vector (rather than by by PCR), PCR), PCR), care care care should should should be be be taken taken taken not not not to to to include include include the the the cloning cloning cloning vector vector vector sequence sequence sequence when when when performing performing similarity searches. Plasmids, cosmids, phagemids, Y ACs and PACs are example types of cloning vectors. Cluster analysis (聚类分析)(聚类分析) A method for grouping together a set of objects that are most similar from a larger group of related objects. The relationships are based on some criterion of similarity or difference. For sequences, a similarity or distance score or a statistical evaluation of those scores is used. Cobbler A single sequence that represents the most conserved regions in a multiple sequence alignment. The BLOCKS server uses the cobbler sequence to perform a database similarity search as a way to reach sequences that are more divergent than would be found using the single sequences in the alignment for searches. Coding system (neural networks) Regarding Regarding neural neural neural networks, networks, networks, a a a coding coding coding system system system needs needs needs to to to be be be designed designed designed for for for representing representing representing input input input and and output. output. The The The level level level of of of success success success found found found when when when training training training the the the model model model will will will be be be partially partially partially dependent dependent dependent on on on the the quality of the coding system chosen. Codon usageAnalysis of the codons used in a particular gene or organism. COG (直系同源簇)(直系同源簇)Clusters of orthologous groups in a set of groups of related sequences in microorganism and yeast (S. cerevisiae). These groups are found by whole proteome comparisons and include orthologs and paralogs. See also Orthologs and Paralogs. Comparative genomics (比较基因组学)(比较基因组学)A comparison of gene numbers, gene locations, and biological functions of genes in the genomes of diverse organisms, one objective being to identify groups of genes that play a unique biological role in a particular organism. Complexity (of an algorithm)(算法的复杂性)(算法的复杂性)Describes the number of steps required by the algorithm to solve a problem as a function of the amount of data; for example, the length of sequences to be aligned. Conditional probability (条件概率)(条件概率)The The probability probability probability of of of a a a particular particular particular result result result (or (or (or of of of a a a particular particular particular value value value of of of a a a variable) variable) variable) given given given one one one or or or more more events or conditions (or values of other variables). Conservation (保守)(保守)Changes at a specific position of an amino acid or (less commonly, DNA) sequence that preserve the physico-chemical properties of the original residue. Consensus (一致序列)(一致序列)A A single single single sequence sequence sequence that that that represents, represents, represents, at at at each each each subsequent subsequent subsequent position, position, position, the the the variation variation variation found found found within within corresponding columns of a multiple sequence alignment. Context-free grammars A A recursive recursive recursive set set set of of of production production production rules rules rules for for for generating generating generating patterns patterns patterns of of of strings. strings. strings. These These These consist consist consist of of of a a a set set set of of terminal characters that are used to create strings, a set of nonterminal symbols that correspond to rules and act as placeholders for patterns that can be generated using terminal characters, a set of rules for replacing nonterminal symbols with terminal characters, and a start symbol. Contig (序列重叠群/拼接序列)拼接序列)A A set set set of of of clones clones clones that that that can can can be be be assembled assembled assembled into into into a a a linear linear linear order. order. order. A A A DNA DNA DNA sequence sequence sequence that that that overlaps overlaps overlaps with with another contig. The full set of overlapping sequences (contigs) can be put together to obtain the sequence for a long region of DNA that cannot be sequenced in one run in a sequencing assay. Important in genetic mapping at the molecular level. CORBA (国际对象管理协作组制定的使OOP 对象与网络接口统一起来的一套跨计算机、操作系统、程序语言和网络的共同标准)作系统、程序语言和网络的共同标准)The The Common Common Common Object Object Object Request Request Request Broker Broker Broker Architecture Architecture Architecture (CORBA) (CORBA) (CORBA) is is is an an an open open open industry industry industry standard standard standard for for working working with with with distributed distributed distributed objects, objects, objects, developed developed developed by by by the the the Object Object Object Management Management Management Group. CORBA allows Group. CORBA allows the interconnection of objects and applications regardless of computer language, machine architecture, or geographic location of the computers. Correlation coefficient (相关系数)(相关系数)A numerical measure, falling between - 1 and 1, of the degree of the linear relationship between two variables. A positive value indicates a direct relationship, a negative negative value value value indicates indicates indicates an an an inverse inverse inverse relationship, relationship, relationship, and and and the the the distance distance distance of of of the the the value value value away away away from from from zero zero indicates the strength of the relationship. A value near zero indicates no relationship between the variables. Covariation (in sequences)(共变)(共变)Coincident change at two or more sequence positions in related sequences that may influence the secondary structures of RNA or protein molecules. Coverage (or depth) (覆盖率(覆盖率/厚度)厚度)The average number of times a nucleotide is represented by a high-quality base in a collection of random raw sequence. Operationally, a 'high-quality base' is defined as one with an accuracy of at least 99% (corresponding to a PHRED score of at least 20). Database (数据库)(数据库)A A computerized computerized computerized storehouse storehouse storehouse of of of data data data that that that provides provides provides a a a standardized standardized standardized way way way for for for locating, locating, locating, adding, adding, removing, and changing data. See also Object-oriented database, Relational database. Dendogram A form of a tree that lists the compared objects (e.g., sequences or genes in a microarray analysis) in a vertical order and joins related ones by levels of branches extending to one side of the list. Depth (厚度)(厚度)See coverage Dirichlet mixtures Defined Defined as as as the the the conjugational conjugational conjugational prior prior prior of of of a a a multinomial multinomial multinomial distribution. distribution. distribution. One One One use use use is is is for for for predicting predicting predicting the the expected expected pattern pattern pattern of of of amino amino amino acid acid acid variation variation variation found found found in in in the the the match match match state state state of of of a a a hid-den hid-den hid-den Markov Markov Markov model model (representing one column of a multiple sequence alignment of proteins), based on prior distributions found in conserved protein domains (blocks). Distance in sequence analysis (序列距离)(序列距离)The number of observed changes in an optimal alignment of two sequences, usually not counting gaps. DNA Sequencing (DNA 测序)测序)The The experimental experimental experimental process process process of of of determining determining determining the the the nucleotide nucleotide nucleotide sequence sequence sequence of of of a a a region region region of of of DNA. DNA. DNA. This This This is is done by labelling each nucleotide (A, C, G or T) with either a radioactive or fluorescent marker which which identifies identifies identifies it. it. it. There There There are are are several several several methods methods methods of of of applying applying applying this this this technology, technology, each each with with with their their advantages and disadvantages. For more information, refer to a current text book. High throughput laboratories laboratories frequently frequently frequently use use use automated automated automated sequencers, sequencers, sequencers, which which which are are are capable capable capable of of of rapidly rapidly rapidly reading reading reading large large numbers of templates. Sometimes, the sequences may be generated more quickly than they can be characterised. Domain (功能域)(功能域)A A discrete discrete discrete portion portion portion of of of a a a protein protein protein assumed assumed assumed to to to fold fold fold independently independently independently of of of the the the rest rest rest of of of the the the protein protein protein and and possessing its own function.Dot matrix (点标矩阵图)(点标矩阵图)Dot matrix diagrams provide a graphical method for comparing two sequences. One sequence is written horizontally across the top of the graph and the other along the left-hand side. Dots are placed within the graph at the intersection of the same letter appearing in both sequences. A series of diagonal lines in the graph indicate regions of alignment. The matrix may be filtered to reveal the the most-alike most-alike most-alike regions regions regions by by by scoring scoring scoring a a a minimal minimal minimal threshold threshold threshold number number number of of of matches matches matches within within within a a a sequence sequence window. Draft genome sequence (基因组序列草图)(基因组序列草图)(基因组序列草图) The sequence produced by combining the information from the individual sequenced clones (by creating merged sequence contigs and then employing linking information to create scaffolds) and positioning the sequence along the physical map of the chromosomes. DUST (一种低复杂性区段过滤程序)(一种低复杂性区段过滤程序)A program for filtering low complexity regions from nucleic acid sequences. Dynamic programming (动态规划法)(动态规划法)A dynamic programming algorithm solves a problem by combining solutions to sub-problems that are computed once and saved in a table or matrix. Dynamic programming is typically used when a problem has many possible solutions and an optimal one needs to be found. This algorithm is used for producing sequence alignments, given a scoring system for sequence comparisons. EMBL (欧洲分子生物学实验室,EMBL 数据库是主要公共核酸序列数据库之一)数据库是主要公共核酸序列数据库之一)European Molecular Biology Laboratories. Maintain the EMBL database, one of the major public sequence databases. EMBnet (欧洲分子生物学网络)(欧洲分子生物学网络)European European Molecular Molecular Molecular Biology Biology Biology Network: Network: Network: / / was was established established established in in in 1988, 1988, 1988, and and provides provides services services services including including including local local local molecular molecular molecular databases databases databases and and and software software software for for for molecular molecular molecular biologists biologists biologists in in Europe. There are several large outposts of EMBnet, including EXPASY . Entropy (熵)(熵)From information theory, a measure of the unpredictable nature of a set of possible elements. The higher the level of variation within the set, the higher the entropy. Erdos and Renyi law In a toss of a “fair” coin, the number of heads in a row that can be expected is the logarithm of the number of tosses to the base 2. The law may be generalized for more than two possible outcomes by changing the base of the logarithm to the number of out-comes. This law was used to analyze the number of matches and mismatches that can be expected between random sequences as a basis for scoring the statistical significance of a sequence alignment. EST (表达序列标签的缩写)(表达序列标签的缩写)See Expressed Sequence Tag Expect value (E)(E 值)值)E E value. value. value. The The The number number number of of of different different different alignents alignents alignents with with with scores scores scores equivalent equivalent equivalent to to to or or or better better better than than than S S S that that that are are expected to occur in a database search by chance. The lower the E value, the more significant the score. In a database similarity search, the probability that an alignment score as good as the one found between a query sequence and a database sequence would be found in as many comparisons between random sequences as was done to find the matching sequence. In other types of sequence analysis, E has a similar meaning. Expectation maximization (sequence analysis) An algorithm for locating similar sequence patterns in a set of sequences. A guessed alignment of the sequences is first used to generate an expected scoring matrix representing the distribution of sequence characters in each column of the alignment, this pattern is matched to each sequence, and and the the the scoring scoring scoring matrix matrix matrix values values values are are are then then then updated updated updated to to to maximize maximize maximize the the the alignment alignment alignment of of of the the the matrix matrix matrix to to to the the sequences. The procedure is repeated until there is no further improvement. Exon (外显子)(外显子)。

药物分析英语词汇Abbe refractometer 阿贝折射仪absorbance 吸收度absorbance ratio 吸收度比值absorption 吸收absorption curve 吸收曲线absorption spectrum 吸收光谱absorptivity 吸收系数accuracy 准确度acid-dye colorimetry 酸性染料比色法acidimetry 酸量法acid-insoluble ash 酸不溶性灰分acidity 酸度activity 活度additive 添加剂additivity 加和性adjusted retention time 调整保留时间adsorbent 吸附剂adsorption 吸附affinity chromatography 亲和色谱法aliquot (一)份alkalinity 碱度alumina 氧化铝ambient temperature 室温ammonium thiocyanate 硫氰酸铵analytical quality control(AQC)分析质量控制anhydrous substance 干燥品anionic surfactant titration 阴离子表面活性剂滴定法antibiotics-microbial test 抗生素微生物检定法antioxidant 抗氧剂appendix 附录application of sample 点样area normalization method 面积归一化法argentimetry 银量法arsenic 砷arsenic stain 砷斑ascending development 上行展开ash-free filter paper 无灰滤纸(定量滤纸)assay 含量测定assay tolerance 含量限度atmospheric pressure ionization(API) 大气压离子化attenuation 衰减back extraction 反萃取back titration 回滴法bacterial endotoxins test 细菌内毒素检查法band absorption 谱带吸收baseline correction 基线校正baseline drift 基线漂移batch, lot 批batch(lot) number 批号Benttendorff method 白田道夫(检砷)法between day (day to day, inter-day) precision 日间精密度between run (inter-run) precision 批间精密度biotransformation 生物转化bioavailability test 生物利用度试验bioequivalence test 生物等效试验biopharmaceutical analysis 体内药物分析,生物药物分析blank test 空白试验boiling range 沸程British Pharmacopeia (BP) 英国药典bromate titration 溴酸盐滴定法bromimetry 溴量法bromocresol green 溴甲酚绿bromocresol purple 溴甲酚紫bromophenol blue 溴酚蓝bromothymol blue 溴麝香草酚蓝bulk drug, pharmaceutical product 原料药buret 滴定管by-product 副产物calibration curve 校正曲线calomel electrode 甘汞电极calorimetry 量热分析capacity factor 容量因子capillary zone electrophoresis (CZE) 毛细管区带电泳capillary gas chromatography 毛细管气相色谱法carrier gas 载气cation-exchange resin 阳离子交换树脂ceri(o)metry 铈量法characteristics, description 性状check valve 单向阀chemical shift 化学位移chelate compound 鳌合物chemically bonded phase 化学键合相chemical equivalent 化学当量Chinese Pharmacopeia (ChP) 中国药典Chinese material medicine 中成药Chinese materia medica 中药学Chinese materia medica preparation 中药制剂Chinese Pharmaceutical Association (CPA) 中国药学会chiral 手性的chiral stationary phase (CSP) 手性固定相chiral separation 手性分离chirality 手性chiral carbon atom 手性碳原子chromatogram 色谱图chromatography 色谱法chromatographic column 色谱柱chromatographic condition 色谱条件chromatographic data processor 色谱数据处理机chromatographic work station 色谱工作站clarity 澄清度clathrate, inclusion compound 包合物clearance 清除率clinical pharmacy 临床药学coefficient of distribution 分配系数coefficient of variation 变异系数color change interval (指示剂)变色范围color reaction 显色反应colorimetric analysis 比色分析colorimetry 比色法column capacity 柱容量column dead volume 柱死体积column efficiency 柱效column interstitial volume 柱隙体积column outlet pressure 柱出口压column temperature 柱温column pressure 柱压column volume 柱体积column overload 柱超载column switching 柱切换committee of drug evaluation 药品审评委员会comparative test 比较试验completeness of solution 溶液的澄清度compound medicines 复方药computer-aided pharmaceutical analysis 计算机辅助药物分析concentration-time curve 浓度-时间曲线confidence interval 置信区间confidence level 置信水平confidence limit 置信限congealing point 凝点congo red 刚果红(指示剂)content uniformity 装量差异controlled trial 对照试验correlation coefficient 相关系数contrast test 对照试验counter ion 反离子(平衡离子)cresol red 甲酚红(指示剂)crucible 坩埚crude drug 生药crystal violet 结晶紫(指示剂)cuvette, cell 比色池cyanide 氰化物cyclodextrin 环糊精cylinder, graduate cylinder, measuring cylinder 量筒cylinder-plate assay 管碟测定法daughter ion (质谱)子离子dead space 死体积dead-stop titration 永停滴定法dead time 死时间decolorization 脱色decomposition point 分解点deflection 偏差deflection point 拐点degassing 脱气deionized water 去离子水deliquescence 潮解depressor substances test 降压物质检查法derivative spectrophotometry 导数分光光度法derivatization 衍生化descending development 下行展开desiccant 干燥剂detection 检查detector 检测器developer, developing reagent 展开剂developing chamber 展开室deviation 偏差dextrose 右旋糖,葡萄糖diastereoisomer 非对映异构体diazotization 重氮化2,6-dichlorindophenol titration 2,6-二氯靛酚滴定法differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) 差示扫描热量法differential spectrophotometry 差示分光光度法differential thermal analysis (DTA) 差示热分析differentiating solvent 区分性溶剂diffusion 扩散digestion 消化diphastic titration 双相滴定disintegration test 崩解试验dispersion 分散度dissolubility 溶解度dissolution test 溶出度检查distilling range 馏程distribution chromatography 分配色谱distribution coefficient 分配系数dose 剂量drug control institutions 药检机构drug quality control 药品质量控制drug release 药物释放度drug standard 药品标准drying to constant weight 干燥至恒重dual wavelength spectrophotometry 双波长分光光度法duplicate test 重复试验effective constituent 有效成分effective plate number 有效板数efficiency of column 柱效electron capture detector 电子捕获检测器electron impact ionization 电子轰击离子化electrophoresis 电泳electrospray interface 电喷雾接口electromigration injection 电迁移进样elimination 消除eluate 洗脱液elution 洗脱emission spectrochemical analysis 发射光谱分析enantiomer 对映体end absorption 末端吸收end point correction 终点校正endogenous substances 内源性物质enzyme immunoassay(EIA) 酶免疫分析enzyme drug 酶类药物enzyme induction 酶诱导enzyme inhibition 酶抑制eosin sodium 曙红钠(指示剂)epimer 差向异构体equilibrium constant 平衡常数equivalence point 等当点error in volumetric analysis 容量分析误差excitation spectrum 激发光谱exclusion chromatography 排阻色谱法expiration date 失效期external standard method 外标法extract 提取物extraction gravimetry 提取重量法extraction titration 提取容量法extrapolated method 外插法,外推法factor 系数,因数,因子feature 特征Fehling’s reaction 费林反应field disorption ionization 场解吸离子化field ionization 场致离子化filter 过滤,滤光片filtration 过滤fineness of the particles 颗粒细度flame ionization detector(FID) 火焰离子化检测器flame emission spectrum 火焰发射光谱flask 烧瓶flow cell 流通池flow injection analysis 流动注射分析flow rate 流速fluorescamine 荧胺fluorescence immunoassay(FIA) 荧光免疫分析fluorescence polarization immunoassay(FPIA) 荧光偏振免疫分析fluorescent agent 荧光剂fluorescence spectrophotometry 荧光分光光度法fluorescence detection 荧光检测器fluorimetyr 荧光分析法foreign odor 异臭foreign pigment 有色杂质formulary 处方集fraction 馏分freezing test 结冻试验funnel 漏斗fused peaks, overlapped peaks 重叠峰fused silica 熔融石英gas chromatography(GC) 气相色谱法gas-liquid chromatography(GLC) 气液色谱法gas purifier 气体净化器gel filtration chromatography 凝胶过滤色谱法gel permeation chromatography 凝胶渗透色谱法general identification test 一般鉴别试验general notices (药典)凡例general requirements (药典)通则good clinical practices(GCP) 药品临床管理规范good laboratory practices(GLP) 药品实验室管理规范good manufacturing practices(GMP) 药品生产质量管理规范good supply practices(GSP) 药品供应管理规范gradient elution 梯度洗脱grating 光栅gravimetric method 重量法Gutzeit test 古蔡(检砷)法half peak width 半峰宽[halide] disk method, wafer method, pellet method 压片法head-space concentrating injector 顶空浓缩进样器heavy metal 重金属heat conductivity 热导率height equivalent to a theoretical plate 理论塔板高度height of an effective plate 有效塔板高度high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) 高效液相色谱法high-performance thin-layer chromatography (HPTLC) 高效薄层色谱法hydrate 水合物hydrolysis 水解hydrophilicity 亲水性hydrophobicity 疏水性hydroscopic 吸湿的hydroxyl value 羟值hyperchromic effect 浓色效应hypochromic effect 淡色效应identification 鉴别ignition to constant weight 灼烧至恒重immobile phase 固定相immunoassay 免疫测定impurity 杂质inactivation 失活index 索引indicator 指示剂indicator electrode 指示电极inhibitor 抑制剂injecting septum 进样隔膜胶垫injection valve 进样阀instrumental analysis 仪器分析insulin assay 胰岛素生物检定法integrator 积分仪intercept 截距interface 接口interference filter 干涉滤光片intermediate 中间体internal standard substance 内标物质international unit(IU) 国际单位in vitro 体外in vivo 体内iodide 碘化物iodoform reaction 碘仿反应iodometry 碘量法ion-exchange cellulose 离子交换纤维素ion pair chromatography 离子对色谱ion suppression 离子抑制ionic strength 离子强度ion-pairing agent 离子对试剂ionization 电离,离子化ionization region 离子化区irreversible indicator 不可逆指示剂irreversible potential 不可逆电位isoabsorptive point 等吸收点isocratic elution 等溶剂组成洗脱isoelectric point 等电点isoosmotic solution 等渗溶液isotherm 等温线Karl Fischer titration 卡尔·费歇尔滴定kinematic viscosity 运动黏度Kjeldahl method for nitrogen 凯氏定氮法Kober reagent 科伯试剂Kovats retention index 科瓦茨保留指数labelled amount 标示量leading peak 前延峰least square method 最小二乘法leveling effect 均化效应licensed pharmacist 执业药师limit control 限量控制limit of detection(LOD) 检测限limit of quantitation(LOQ) 定量限limit test (杂质)限度(或限量)试验limutus amebocyte lysate(LAL) 鲎试验linearity and range 线性及范围linearity scanning 线性扫描liquid chromatograph/mass spectrometer (LC/MS) 液质联用仪litmus paper 石蕊试纸loss on drying 干燥失重low pressure gradient pump 低压梯度泵luminescence 发光lyophilization 冷冻干燥main constituent 主成分make-up gas 尾吹气maltol reaction 麦牙酚试验Marquis test 马奎斯试验mass analyzer detector 质量分析检测器mass spectrometric analysis 质谱分析mass spectrum 质谱图mean deviation 平均偏差measuring flask, volumetric flask 量瓶measuring pipet(te) 刻度吸量管medicinal herb 草药melting point 熔点melting range 熔距metabolite 代谢物metastable ion 亚稳离子methyl orange 甲基橙methyl red 甲基红micellar chromatography 胶束色谱法micellar electrokinetic capillary chromatography(MECC, MEKC) 胶束电动毛细管色谱法micelle 胶束microanalysis 微量分析microcrystal 微晶microdialysis 微透析micropacked column 微型填充柱microsome 微粒体microsyringe 微量注射器migration time 迁移时间millipore filtration 微孔过滤minimum fill 最低装量mobile phase 流动相modifier 改性剂,调节剂molecular formula 分子式monitor 检测,监测monochromator 单色器monographs 正文mortar 研钵moving belt interface 传送带接口multidimensional detection 多维检测multiple linear regression 多元线性回归multivariate calibration 多元校正natural product 天然产物Nessler glasses(tube) 奈斯勒比色管Nessler’s reagent 碱性碘化汞钾试液neutralization 中和nitrogen content 总氮量nonaqueous acid-base titration 非水酸碱滴定nonprescription drug, over the counter drugs (OTC drugs) 非处方药nonproprietary name, generic name 非专有名nonspecific impurity 一般杂质non-volatile matter 不挥发物normal phase 正相normalization 归一化法notice 凡例nujol mull method 石蜡糊法octadecylsilane chemically bonded silica 十八烷基硅烷键合硅胶octylsilane 辛(烷)基硅烷odorless 无臭official name 法定名official specifications 法定标准official test 法定试验on-column detector 柱上检测器on-column injection 柱头进样on-line degasser 在线脱气设备on the dried basis 按干燥品计opalescence 乳浊open tubular column 开管色谱柱optical activity 光学活性optical isomerism 旋光异构optical purity 光学纯度optimization function 优化函数organic volatile impurities 有机挥发性杂质orthogonal function spectrophotometry 正交函数分光光度法orthogonal test 正交试验orthophenanthroline 邻二氮菲outlier 可疑数据,逸出值overtones 倍频峰,泛频峰oxidation-reduction titration 氧化还原滴定oxygen flask combustion 氧瓶燃烧packed column 填充柱packing material 色谱柱填料palladium ion colorimetry 钯离子比色法parallel analysis 平行分析parent ion 母离子particulate matter 不溶性微粒partition coefficient 分配系数parts per million (ppm) 百万分之几pattern recognition 模式识别peak symmetry 峰不对称性peak valley 峰谷peak width at half height 半峰宽percent transmittance 透光百分率pH indicator absorbance ratio method pH指示剂吸光度比值法pharmaceutical analysis 药物分析pharmacopeia 药典pharmacy 药学phenolphthalein 酚酞photodiode array detector(DAD) 光电二极管阵列检测器photometer 光度计pipeclay triangle 泥三角pipet(te) 吸移管,精密量取planar chromatography 平板色谱法plate storage rack 薄层板贮箱polarimeter 旋光计polarimetry 旋光测定法polarity 极性polyacrylamide gel 聚丙酰胺凝胶polydextran gel 葡聚糖凝胶polystyrene gel 聚苯乙烯凝胶polystyrene film 聚苯乙烯薄膜porous polymer beads 高分子多孔小球post-column derivatization 柱后衍生化potentiometer 电位计potentiometric titration 电位滴定法precipitation form 沉淀形式precision 精密度pre-column derivatization 柱前衍生化preparation 制剂prescription drug 处方药pretreatment 预处理primary standard 基准物质principal component analysis 主成分分析programmed temperature gas chromatography 程序升温气相色谱法prototype drug 原型药物provisions for new drug approval 新药审批办法purification 纯化purity 纯度pyrogen 热原pycnometric method 比重瓶法quality control(QC) 质量控制quality evaluation 质量评价quality standard 质量标准quantitative determination 定量测定quantitative analysis 定量分析quasi-molecular ion 准分子离子racemization 消旋化radioimmunoassay 放射免疫分析法random sampling 随机抽样rational use of drug 合理用药readily carbonizable substance 易炭化物reagent sprayer 试剂喷雾器recovery 回收率reference electrode 参比电极refractive index 折光指数related substance 有关物质relative density 相对密度relative intensity 相对强度repeatability 重复性replicate determination 平行测定reproducibility 重现性residual basic hydrolysis method 剩余碱水解法residual liquid junction potential 残余液接电位residual titration 剩余滴定residue on ignition 炽灼残渣resolution 分辨率,分离度response time 响应时间retention 保留reversed phase chromatography 反相色谱法reverse osmosis 反渗透rider peak 驼峰rinse 清洗,淋洗robustness 可靠性,稳定性routine analysis 常规分析round 修约(数字)ruggedness 耐用性safety 安全性Sakaguchi test 坂口试验salt bridge 盐桥salting out 盐析sample applicator 点样器sample application 点样sample on-line pretreatment 试样在线预处理sampling 取样saponification value 皂化值saturated calomel electrode(SCE) 饱和甘汞电极selectivity 选择性separatory funnel 分液漏斗shoulder peak 肩峰signal to noise ratio 信噪比significant difference 显著性差异significant figure 有效数字significant level 显著性水平significant testing 显著性检验silanophilic interaction 亲硅羟基作用silica gel 硅胶silver chloride electrode 氯化银电极similarity 相似性simultaneous equations method 解线性方程组法size exclusion chromatography(SEC) 空间排阻色谱法sodium dodecylsulfate, SDS 十二烷基硫酸钠sodium hexanesulfonate 己烷磺酸钠sodium taurocholate 牛璜胆酸钠sodium tetraphenylborate 四苯硼钠sodium thiosulphate 硫代硫酸钠solid-phase extraction 固相萃取solubility 溶解度solvent front 溶剂前沿solvophobic interaction 疏溶剂作用specific absorbance 吸收系数specification 规格specificity 专属性specific rotation 比旋度specific weight 比重spiked 加入标准的split injection 分流进样splitless injection 无分流进样spray reagent (平板色谱中的)显色剂spreader 铺板机stability 稳定性standard color solution 标准比色液standard deviation 标准差standardization 标定standard operating procedure(SOP) 标准操作规程standard substance 标准品stationary phase coating 固定相涂布starch indicator 淀粉指示剂statistical error 统计误差sterility test 无菌试验stirring bar 搅拌棒stock solution 储备液stoichiometric point 化学计量点storage 贮藏stray light 杂散光substituent 取代基substrate 底物sulfate 硫酸盐sulphated ash 硫酸盐灰分supercritical fluid chromatography(SFC) 超临界流体色谱法support 载体(担体)suspension 悬浊液swelling degree 膨胀度symmetry factor 对称因子syringe pump 注射泵systematic error 系统误差system model 系统模型system suitability 系统适用性tablet 片剂tailing factor 拖尾因子tailing peak 拖尾峰tailing-suppressing reagent 扫尾剂test of hypothesis 假设检验test solution(TS) 试液tetrazolium colorimetry 四氮唑比色法therapeutic drug monitoring(TDM) 治疗药物监测thermal analysis 热分析法thermal conductivity detector 热导检测器thermocouple detector 热电偶检测器thermogravimetric analysis(TGA) 热重分析法thermospray interface 热喷雾接口The United States Pharmacopoeia(USP) 美国药典The Pharmacopoeia of Japan(JP) 日本药局方thin layer chromatography(TLC) 薄层色谱法thiochrome reaction 硫色素反应three-dimensional chromatogram 三维色谱图thymol 百里酚(麝香草酚)(指示剂)thymolphthalein 百里酚酞(麝香草酚酞)(指示剂)thymolsulfonphthalein ( thymol blue) 百里酚蓝(麝香草酚蓝)(指示剂)titer, titre 滴定度time-resolved fluoroimmunoassay 时间分辨荧光免疫法titrant 滴定剂titration error 滴定误差titrimetric analysis 滴定分析法tolerance 容许限toluene distillation method 甲苯蒸馏法toluidine blue 甲苯胺蓝(指示剂)total ash 总灰分total quality control(TQC) 全面质量控制traditional drugs 传统药traditional Chinese medicine 中药transfer pipet 移液管turbidance 混浊turbidimetric assay 浊度测定法turbidimetry 比浊法turbidity 浊度ultracentrifugation 超速离心ultrasonic mixer 超生混合器ultraviolet irradiation 紫外线照射undue toxicity 异常毒性uniform design 均匀设计uniformity of dosage units 含量均匀度uniformity of volume 装量均匀性(装量差异)uniformity of weight 重量均匀性(片重差异)validity 可靠性variance 方差versus …对…,…与…的关系曲线viscosity 粘度volatile oil determination apparatus 挥发油测定器volatilization 挥发法volumetric analysis 容量分析volumetric solution(VS) 滴定液vortex mixer 涡旋混合器watch glass 表面皿wave length 波长wave number 波数weighing bottle 称量瓶weighing form 称量形式weights 砝码well-closed container 密闭容器xylene cyanol blue FF 二甲苯蓝FF(指示剂)xylenol orange 二甲酚橙(指示剂)zigzag scanning 锯齿扫描zone electrophoresis 区带电泳zwitterions 两性离子zymolysis 酶解作用。

床上用品专用英语单词床上用品:Bedding; bedclothes 绝对地道,这是报关员考试教材上的翻译被子 Quilt; Duvet(充羽毛、绒制成的)被壳 Comforter Shell传统式枕套:Pillow Sham开口式枕套: Pillow Case靠垫 Cushion帷幔 Valance窗帘 Curtain闺枕 Boudoir Pillow圆抱枕 Neck Roll被单 Bed Sheet, 床单sheet=bedsheet=flat Sheet包被单 Sheet床单 Flat Sheet床罩 Fitted Sheet; Bed Cover ,BED SPREAD 床罩,也叫Fitted Sheet,床裙 Bed Spread; Bed Skirt (BEDSPREAD有时也做床裙 )枕巾 Pillow Towel桌布 Tablecloth盖毯 Throw毛毯 Woolen Blanket毛巾毯 Towel Blanket睡袋 Sleeping bag; FleabagFITTED COVER 床笠THROW, QUILT, COMFORTER, DUVET 之间的区别是什么?Duvet 和Comforter在英语中都是被子的意思,前者多用于英国,后者多用于美国。

有时也可以用quilt,但是quilt还一种意思是西式做床罩在整张床上的床罩(酒店里那种)。

Throw :毯子Flat sheet --平面床罩。

Fitted sheet--松紧床套。

Duvet Cover--有填充物的被套。

Bedspread--床盖,即床罩。

Petticoat--床裙。

Comforter--指直接由被套加棉心缝制成的美式棉被。

Sham--指有花边的枕套。

European sham--指比标准枕头尺寸更大的方形花边枕套。

Flat sheet --平面床罩。

Fitted sheet--松紧床套。

Duvet Cover--有填充物的被套。

Journal of Hazardous Materials 177 (2010) 892–898Contents lists available at ScienceDirectJournal of HazardousMaterialsj o u r n a l h o m e p a g e :w w w.e l s e v i e r.c o m /l o c a t e /j h a z m atGenotoxicity study of photolytically treated 2-chloropyridine aqueous solutionsDimitris Vlastos a ,∗,Charalambos G.Skoutelis a ,Ioannis T.Theodoridis a ,David R.Stapleton b ,Maria I.Papadaki a ,ba Department of Environmental and Natural Resources Management,University of Ioannina,Seferi 2,Agrinio 30100,Greece bChemical Engineering,IPSE,School of Process Environmental and Materials Engineering,University of Leeds,Leeds LS29JT,UKa r t i c l e i n f o Article history:Received 4November 2009Received in revised form 21December 2009Accepted 30December 2009Available online 7 January 2010Keywords:Genotoxicity PhotolysisMicronucleus assay2-Chloropyridine mineralisation Pyridinesa b s t r a c t2-Chloropyridine (2-CPY)has been identified as a trace organic chemical in process streams,wastewater and even drinking water.Furthermore,it appears to be formed as a secondary pollutant during the decomposition of specific insecticides.As reported in our previous work,2-CPY was readily removed and slowly mineralised when subjected to ultraviolet (UV)irradiation at 254nm.Moreover,2-CPY was found to be genotoxic at 100g ml −1but it was not genotoxic at or below 50g ml −1.In this work 2-CPY aqueous solutions were treated by means of UV irradiation at 254nm.2-CPY mineralisation history under different conditions is shown.2-CPY was found to mineralise completely upon prolonged irradiation.Identified products of 2-CPY photolytic decomposition are presented.Solution genotoxicity was tested as a function of treatment time.Aqueous solution samples,taken at different photo-treatment times were tested in cultured human lymphocytes applying the cytokinesis block micronucleus (CBMN)assay.It was found that the solution was genotoxic even when 2-CPY had been practically removed.This shows that photo-treatment of 2-CPY produces genotoxic products.Upon prolonged irradiation solution genotoxicity values approached the control value.© 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.1.IntroductionGenotoxic substances may represent a health hazard to humans but also may affect organisms in the environment.Pyridine and pyridine derivatives (PPDs)have received great attention because of their potential environmental and health threats.They may enter the environment as a consequence of their extensive use as insecticides and herbicides in agriculture and through industrial activities associated with pharmaceutical and textile manufacture and chemical synthesis [1–3].Widespread use of such pesticides and urban,industrial effluents can result in contamination of surface and ground waters in areas around appli-cation or discharges zones.Degradation of those compounds via naturally occurring physicochemical and/or biological processes can result in significant levels of PPDs in water environments [4,5].2-Chloropyridine (2-CPY),in particular has been reported to be an environmental contaminant,although it has not been reported to occur naturally.According to Arch Chemicals,Inc.[6]it is a key intermediate in the manufacture of pyrithione-based biocides for use in cosmetics and various pharmaceutical products.The Dow Chemical Co.has identified it as a trace organic chemical in pro-∗Corresponding author.Tel.:+302641074148;fax:+302641074150.E-mail address:dvlastos@cc.uoi.gr (D.Vlastos).cess streams and wastewater [7].It has also been identified as a Rhine River pollutant in the Netherlands and a trace organic con-taminant in drinking water derived from river water in Barcelona,Spain [8,9].Furthermore,it appears to be formed as a secondary pollutant during the decomposition of specific insecticides,such as imidaclo-prid.All the main imidacloprid metabolites identified in mammals,plants and insects contain the 2-CPY moiety.This moiety has an important contribution in the toxic effects that those metabolites impose on target and non-target insects [10,11].The application of photochemical advanced oxidation processes (PAOPs)for the removal of organics is gaining importance in water treatment.Among others,ultraviolet (UV)light-induced degra-dation processes constitute a well-established practice in water and wastewater treatment and the interest in this area has been constantly increasing in the recent past.UV-driven advanced oxi-dation processes (AOPs)are primarily based on the generation of powerful oxidizing species,such as OH radicals,through the photolysis of H 2O 2or through processes such as photo-Fenton reactions and semiconductor photocatalysis [10].UV-driven photo-chemical treatment and TiO 2based heterogeneous photocatalysis effectively degrade many organic pollutants such as dyes,pesti-cides,halogenated compounds,and surfactants,e.g.[2,3,12–15].It is worth noting that thousands of research studies on the chemical-photodegradation of various organics have been undertaken over the years,a great number of which result on their successful pho-0304-3894/$–see front matter © 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.12.117D.Vlastos et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials177 (2010) 892–898893todegradation.However,the elimination of their genotoxicity has not been equally researched.Only few investigations have been carried out with the aim to evaluate the in vitro genotoxicity in humans’cells before and after their treatment.From an environmental point of view,there are advantages if photochemical methods for the degradation of the environmental pollutants are used.On the other hand,a serious question arises, about the toxicity and/or genotoxicity fate of the photodegradation products into the environment and their side effects to humans and other organisms.In recent years,there has been intense development of bioana-lytical techniques that employ live organisms as indicators.Biotests detect the presence of toxic substances in the environment,and determine their toxicity in the samples analyzed by quantitatively estimating the harm that they cause to live organisms.Until now, many microbiotests that have been developed have employed vari-ous indicator organisms such as algae,vascular plants,crustaceans, rotifers and protozoans[16].However,the available information on the genotoxicity of the intermediates which are generated by the different photodegra-dation methods on several environmental pollutants is limited. Moreover,the difficulties in the interpretation of the biotest results in terms of the extrapolation from various organisms to humans cannot be underestimated.It is therefore important to combine photochemical treatment work with genotoxicity studies on human cells.Traditionally,different genotoxic endpoints in different bioas-says have been used to investigate the genotoxicity of several environmental pollutants.The cytokinesis block micronucleus (CBMN)assay,first reported by Fenech and Morley[17],has been widely used in different cell types including human lymphocytes for the evaluation of the genotoxic and cytotoxic potential of vari-ous agents[18–21].Micronuclei(MN)contain acentric chromosome fragments or whole chromosomes and they can be recognized as distinct forma-tions that exist in daughter cells separated from the main nucleus [18].They are the result of chromosome breakage and/or chromo-some loss due to lagging chromosomes during anaphase of mitosis. The main characteristic of the assay is the use of Cytochalasin-B, an inhibitor of actin polymerization,which prevents cytokinesis, while permitting nuclear division[17,22].As a result,binucleated (BN)cells are produced which are scored for the presence of MN. Scoring MN only in BN cells makes the method very sensitive for the analysis of lymphocytes that have undergone one division.In our previous work[23,24]it was reported that2-CPY,which was found to be genotoxic at100g ml−1,is readily removed upon photolytic treatment at254nm.2-CPY rate of removal was found to increase with increasing temperature,and on lowering solution volume or initial2-CPY concentration.2-CPY photoly-sis yields2-hydroxypyridine(2-HPY)as the primary intermediate which is further removed upon prolonged photolysis.The present work shows the effect of254nm UV light-induced degradation on solution total organic carbon(TOC)removal and on the solu-tion effective genotoxicity.The changes of the genotoxicity of aqueous solutions of2-CPY irradiated by means of UV light at 254nm,at solution natural pH,at different treatment times are studied.2.Materials and methods2.1.Chemicals and photo-treatment2-CPY(C5H4NCl)was supplied by Fluka(product code:26280; CAS number109-09-1;purity≥98.0%by GC).It was used without further purification.Aqueous solutions were made using Milli-Q purity water.2.1.1.Measurements employed in the purely photolytic studyUnless otherwise stated,experiments were performed at initial substrate concentrations of300g ml−1under different condi-tions,i.e.400ml of solution was irradiated isothermally at50◦C for the time required to achieve complete TOC removal.Measurements were performed in an open or air tight system,with or without agitation,with or without air purging with or without radical scav-enger tert-butanol,with or without helium purging,at solution natural pH.The basic experimental set-up used in all of the above measure-ments is shown in detail elsewhere[23,24].Briefly,it consists of a glass reactor where the solution is illuminated by means of a low-pressure,110W,mercury lamp with90%emittance at254nm. The reaction mixture was held in a dark vessel submerged in a Huber-ministat1200constant temperature bath and was continu-ously and steadily circulated through the reactor at aflow-rate of 200ml min−1.The photoreactor had27mm i.d.and an approximate height of300mm.Sample pH and temperature were continuously measured and logged in the computer.Two Pt-A thermometers were placed at the UV reactor entrance and exit,respectively.The arithmetic average of these two temperatures,which differed by less than1◦C,was reported as the measurement temperature.To examine the effect of stripping in the purged with air measure-ments,where loss of volatile compounds is more pronounced, experiments were run with the addition of a reflux system.A coil condenser wasfitted in order to cool the air leaving the system and condense as much as possible from the stripped organic material. An antifreeze/water mixture was re-circulated through condenser coil at−10◦C.Samples periodically drawn from the vessel were analysed by means of high performance liquid chromatography(HPLC)and 2-CPY and primary intermediate product,2-HPY,concentration was quantified.HPLC measurements were performed using the methodology presented in our previous work[2].2-CPY degrada-tion products which could not be identified and quantified with HPLC were identified via GC–MS according to the methodology presented in the same work[2].As reported in[2],those analy-ses were performed onfit-for-the-purpose measurements where the entire end-volume of the solution was used for a single GC–MS analysis.The results obtained were qualitative,i.e.there was no-quantification or association of their production with photo-treatment time.TOC was analysed by means of catalytic combustion/non-dispersive infrared gas analysis on a Shimadzu5050TOC analyzer following the methodology presented in[23].A Hanna Instruments pH211pH meter with a Hanna Instruments HI1131probe was used for the measurement of pH.2.1.2.Measurements employed in the genotoxicity studySix series of experiments were performed at initial sub-strate concentrations of2000±100g ml−1.210ml of solution was irradiated isothermally at around35◦C,in a closed but not air tight system,outlined in Section 2.1.1,under vigor-ous agitation,at solution natural pH.Samples were withdrawn and analysed by HPLC(Dionex P680system)with a Dionex 1024dio-array equipped with an Acclaim C185m120Å, 406mm×250mm column using a50:50water:acetonitrile iso-cratic mobile phase at1ml min−1.UV detection was at201,206, 210,254and261nm.Where appropriate,calibration curves were established using external standards at various concentrations and were used for quantification.HPLC analyses were run in duplicate and mean values of two separate measurements are quoted as results.The same parent samples were used for the genotoxicity study following the protocol described in Section 2.2.894 D.Vlastos et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials 177 (2010) 892–8982.2.CBMN assay in human lymphocytes in vitroBlood samples were derived from two healthy individuals (22years old,non-smokers)not undergoing any drug treatment and who did not have any viral infection or X-ray exposure for over a year.Whole blood (0.5ml)was added to 6.5ml Ham’s F-10medium (Invitrogen), 1.5ml foetal calf serum (Invitrogen)and 0.3ml phytohaemagglutinin (Invitrogen)to stimulate cell division.The appropriate volume of 2-CPY or 2-CPY phototreated solution (the same for all samples)was added 24h post-culture initiation to achieve a final nominal 2-CPY concentration of 100g ml −1.The selection of this concentration is justified in Stapleton et al.[24].2-CPY nominal concentration (100g ml −1)was equal to the actual 2-CPY concentration only in the photochemically untreated samples (t =0).For photolytically treated solutions the nominal concentration was calculated relatively to the initial solution con-centration and not to the actual 2-CPY concentration at the time the sample was withdrawn.Samples were dissolved in double dis-tilled H 2O (dd H 2O).Mitomycin-C (Sigma)at final concentration of 0.5g ml −1served as positive control.For the MN study,6g ml −1Cytochalasin-B (Sigma)was added to the culture medium 44h after its initiation and 20h after the addition of the appropriate 2-CPY solution.Cells were harvested 72h after the initiation of culture and were collected by centrifugation.A mild hypotonic treatment with a 1:3solution of Ham’s medium and dd H 2O supplemented with 2%serum was given for 3min at room temperature and was followed by 10min fixation with a fresh 5:1solution of methanol/acetic acid.Cells were stained with 7%Giemsa [19,20].At least 2000BN cells with preserved cytoplasm were scored per treatment,in order to calculate the frequency of MN.Standard criteria [18]were used for scoring MN.The Cytokinesis Block Proliferation Index (CBPI),is given by the equation:CBPI =M 1+2M 2+3(M 3+M 4)/N ,where M 1,M 2,M 3and M 4correspond to the numbers of cells with one,two,three and four nuclei,respectively and N is the total number of cells [25].CBPI was calculated by counting at least 2000cells in order to determine possible cytotoxic effects.The calculation of MN size was also used as an additional parameter to indicate whether the activity of the tested sub-stances was clastogenic or aneugenic [19,26].Small size MN is more likely to contain acentric chromosome fragments indi-cating a clastogenic effect,while large size MN may possibly contain whole chromosomes thus indicating an aneugenic effect [27–29].Fig.1.Normalised TOC removal at 50◦C and solution natural pH,without agita-tion (laminar-flow).(᭹)2-CPY initial concentration 500g ml −1,solution volume 400ml;(+)2-CPY initial concentration 300g ml −1,solution volume 400ml;( )2-CPY initial concentration 300g ml −1,solution volume 250ml.Fig.2.Normalised TOC removal:2-CPY initial concentration 300g ml −1,solution volume 400ml:at solution natural pH and 50◦C.( )Laminar,non-aerated flow;( ),swirl-flow;(᭹),swirl-flow,purging with air and overhead condenser;(+)swirl-flow,purging with air.Inset:pH during photo-treatment:( )laminar,non-aerated flow;( )swirl-flow;(᭹)swirl-flow,purging with air and overhead condenser;(+)swirl-flow,purging with air;(*)laminar,purged with air flow.MN size is expressed as the ratio of MN diameter to the cell nucleus diameter.MN size was characterised as small,when this ratio was ≤1/10,medium,when this ratio was in the range 1/3to 1/9and large when its value was ≈1/3of nuclear diameter [19].2.3.Statistical analysisAll results are expressed as the mean frequency ±standard error (MF ±SE).Differences of MN data among treatment and control groups were tested by the G -test for independence on 2×2tables.This test is based on the general assumption of the 2analysis,but offers theoretical and computational advantages [30].The 2-test was used for the analysis of CBPI among each treatment.Differ-ences at p <0.05were considered significant.G -test was evaluated using the data analysis statistical software Minitab (Minitab Inc.,Pennsylvania,USA).3.Results and discussion 3.1.Photolytic treatment of 2-CPYAs mentioned earlier,2-CPY was found to be readily removed following photolytic treatment,yielding primarily 2-HPY [23].Upon prolonged irradiation TOC removal is possible.Fig.1shows the effect of volume and solution initial concentration on the rate of TOC removal.As can be seen in Fig.1,increased volume or initial concentration prolongs TOC removal.Fig.2shows TOC removal of 300g ml −1,400ml solution at 50◦C under different conditions,namely under air purging,with and without agitation in an open but not air tight system as well as with an overhead condenser.In the same figure the pH history of those measurements as well as the pH profile of a laminar-flow measurement with air purging is shown.Although 2-CPY rate of removal has been found not to depend on purging with air or agitation,TOC removal does depend on those factors as can be seen in Fig.2.It can also be seen that TOC is faster removed in purged with air measurements.254nm UV irradiation results in 2-CPY fast de-halogenation,with a very rapid pH drop.Prolonged UV-treatment results in complete mineralisa-tion,which is however faster in the measurements were oxygen is readily available.So,the fastest TOC removal is observed in the agitated,purged with air measurement.The solution pH rises in all purged with air measurements to approximately neutral where it is maintained until sample complete mineralisation.The avail-ability of oxygen appears to affect directly how fast pH rises.In measurements purged with helium (not shown here)or measure-D.Vlastos et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials177 (2010) 892–898895Fig.3.Outline of2-CPY254nm photolytic decomposition pathways and products. ments where oxygen is not provided,pH remains acidic throughout the measurement.2-HPY is thefirst major intermediate produced by this reaction[23,24,31],the removal of which was found to be faster in a rich in oxygen solution due to photo-oxidation[3].Purg-ing with helium(not shown here)and addition of radical scavenger tert-butanol resulted in the same mineralisation history as the mea-surement performed under laminar-flow in a closed system.The presence of tert-butanol in the purged with air measurement was slower,with a respective slower pH rise than the measurement performed at the same otherwise conditions but tert-butanol addi-tion.Purging with air,however,results in some stripping of volatile products,which macroscopically appears as TOC removal.This was verified by the measurement performed with the use of an over-head condenser which displayed a slower TOC removal and pH rise than the measurement where this condenser was absent,at the same otherwise conditions.The products obtained via GC–MS(and HPLC)analysis,their GC–MS retention time and similarity match are shown in Table1while Fig.3outlines their macroscopic formation paths. All products reported in Table1but formamide(P8)have been identified via GC–MS or/and HPLC.2-HPY(P1),is directly produced from2-CPY and it is subsequently forming Dewar pyridinone(product P2)as in the case of other2-halogenated pyridines while a small amount of2-CPY reacts directly to form Dewar pyridinone[2].Products P2(5-azabicyclo[2.2.0]hex-2-en-6-one),P3(1H-pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde),P4(6-hydroxy-2(1H)-pyridinone),P5(N-formyl-3-carbamoylpropenal)and P11 (2-pyridinecarbonitrile)have been also identified in the degrada-tion of other2-halogenated pyridines[2],while products P5and P9(6-chloro-2-pyridinecarboxylic acid)were also found to form during2-CPY photocatalysis[32].Moreover,products P5and P11 were also identified during2-fluoropyridine photocatalysis[32]. N-Formyl-3-carbamoylpropenal,product P5,was also identified in the degradation of pyridine and its formation bares close anal-ogy to the mechanism followed for the degradation of pyridine [33].The mass spectrum of P5is similar to that reported in[33], together with the analysis of the different ion fragments while the molecular ion at m/z=127is also present.The degradation of the later aliphatic product could then result in the production of short-chain compounds such as,formamide(P8),[33–35],as well as acetic and formic acid.The latter two(products P6and P7, respectively)have been identified in the current study by GC–MS. Compound P11was detected in traces and is also expected to form at the later stages of the reaction potentially through the formation of2-carbamoylpyridine,as a result of reaction of formamide and pyridine,that could be dehydrated during the GC–MS analysis.The formation of2-pyridinecarboxylic acid,compound P9,can be produced by a reaction of the substrate,2-CPY,with formic acid, which is formed in the later stages of the degradation process.3.2.CBMN assay in human lymphocytes in vitro2-CPY and2-HPY concentrations were measured as a function of time via HPLC and the profile of those two concentrations of a typical measurement used for the genotoxicity study is shown in Fig.4.2-CPY initial concentration employed in the photolytic mea-surements was ca.2000g ml−1.The addition of the phototreated sample to the culture inevitably resulted in sample dilution.In order to achieve consistency with previous study[24],the samples employed in the genotoxicity study where obtained from the pho-totreated ones after appropriate dilution to the concentration range of the ones employed in[24].Thus,the samples employed in the genotoxicity study had an equivalent to2-CPY initial concentration of100g ml−1.The embedded Fig.4shows the total number of large MN found in2000BN cells(which indicate aneuploidy)and the mean CBPI values(which indicate cytotoxicity)of each treatment.The arrows indicate the axis where each quantity is read.Table2shows the results obtained from peripheral blood lym-phocytes cultures treated with2-CPY before and after treatment by UV light in different degradation times.As can be seen in Table2,2-CPY induced a statistically signif-icant increase(p<0.001)in the frequency of MN and binucleated micronucleated(BNMN)cells at the concentration of100g ml−1, before UV light treatment,compared to the control.In the case of treatments by UV light at20,50,120,160,240and300min the frequencies of MN and BNMN were still significant(p<0.001).In the case of treatments by UV light at600,900and1200min our data indicated no significant statistical differences in both MN and BNMN frequencies compared to the control value.The reported control and positive control frequencies of MN shown in this work are consistent with the literature[20,36,37].Fig.4.Normalised concentration of2-CPY and2-HPY at solution natural pH,35◦C and,laminar,non-aeratedflow.( )[2-CPY]/[2-CPY]0;(᭹)[2-HPY]/[2-CPY]0.Inset: Total number of large MN found in2000BN cells(left-hand axis,wide bars)and mean CBPI value(right hand axis,thin grey bars)of diluted phototreated samples.896 D.Vlastos et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials 177 (2010) 892–898The 2-CPY cytotoxic effect before and after UV irradiation was evaluated by the determination of CBPI.Regarding the cytotoxic index,statistically significant differences (p <0.001)on CBPI were detected between control and untreated or treated by UV irradia-tion,2-CPY cultures.As can be seen in Table 2and Fig.4,solution irradiation caused a gradual drop of CBPI value for the first 240min,thus indicating the formation of cytotoxic intermediates.The low-est CBPI value was observed at 240min.Subsequently CBPI value was gradually increasing,reaching the control value after 1200min of irradiation.The size ratio of MN in the in vitro CBMN assay is an alerting index as effective as the fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)analysis for the discrimination of clastogenic and aneugenic effects [19,26].Data on the size ratio of MN (‰)induced by 2-CPY before and after irradiation compared to the control,are presented in Fig.5.Compared to the control size ratio of MN,an over threefold increase in small size MN frequency was observed up to 160min,as well as,an over twofold increase from 240up to 600min of irradia-tion of 2-CPY.In addition,three and over threefold increase in large MN frequency was observed during the first 300min of irradiation of 2-CPY,which subsequently was decreased to reach the control value after 600min of irradiation,as shown in Fig.4.There are very few studies in the literature on the mutagenicity of the tested compound.The findings reported in those studies were not always consistent.2-CPY was mutagenic when tested at concentrations up to 7500g/plate in the Salmonella typhimurium /mammalian micro-Table 1Products formed during 254nm photolytic treatment of 2-CPY aqueous solutions.CompoundNameStructureGC–MS retention time (min)Similarity match (%)P 12-Hydroxypyridine 16.55997P 25-Azabicyclo[2.2.0]hex-2-en-6-one (or Dewar pyridinone)12.64485P 31H-Pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde 11.11780P 46-Hydroxy-2(1H)-pyridinone 10.34870P 5N-Formyl-3-carbamoylpropenal 13.90772P 6Acetic acid 5.15890P 7Formic acid 4.98290P 8Formamide No direct measurementP 96-Chloro-2-pyridinecarboxylic acid 7.76887P 102,3-Dichloro-pyridine 11.15492P 112-Pyridinecarbonitrile 20.42078D.Vlastos et al./Journal of Hazardous Materials 177 (2010) 892–898897Table 2Frequencies of micronucleated binucleated cells (BNMN)and micronuclei (MN),during 254nm UV photo-treatment of 2-CPY aqueous solutions.Photo-treatment time (min)BNMN MF(‰)±SEMN MF(‰)±SE CBPI MF ±SE Control 04±0 4.0±0 2.09±0.18Positive control (0.5g ml −1MMC)076.0±4.0*83.0±4.0* 1.39±0.04*2-CPY (100g ml −1)012.0±0.0*12.5±0.5* 1.71±0.04*2012.0±2.0*13.0±1.0* 1.67±0.05*508.5±0.5*9.5±0.5* 1.64±0.10*12011.0±2.0*13.0±1.0* 1.68±0.02*1609.0±0.0*11.5±0.5* 1.56±0.02*24010.5±0.5*11.0±0.0* 1.45±0.03*3008.0±1.0*8.5±0.5* 1.65±0.16*600 5.0±1.0 6.0±2.0 1.65±0.16*900 6.0±2.0 6.0±2.0 1.60±0.08*12004.0±0.04.0±0.01.80±0.07*2-CPY:2-Chloropyridine,BNMN:micronucleated binucleated cells,MN:micronuclei,CBPI:cytokinesis block prolifer-ation index,MMC:mitomycin-C,MF(‰)±se:mean frequencies (‰)±standard error,*p <0.001[G -test for BNMN and MN; 2for CBPI].some assay in strains TA97,TA98,TA100and TA102with metabolic activation,but non-mutagenic when tested in the same strains at concentrations up to 5000g/plate without activation [38].Zimmermann et al.[39]reported 2-CPY to be one of a series of pyridine derivatives which induced mitotic aneuploidy in Saccha-romyces cerevisiae .The ability to induce chromosomal aberrations by 2-CPY,wastested in V 3cells (an African Green monkey kidney cell line).In a dose range from 400to 3200g ml −1,2-CPY was found to be non-cytotoxic and non-clastogenic [40].However,when tested in the L5178Y mouse lymphoma mammalian system,in concentrations up to 2004g ml −1,induced gene mutations and chromosomal aber-rations with and without metabolic system.2-CPY also induced MN when tested at concentrations from 1920to 1992g ml −1in mouse lymphoma cells [41].In our recent study of the potential in vitro genotoxicity of 2-CPY,statistically significant differences were observed in MN frequency between control and 100g ml −1of 2-CPY [24].Our results are in accordance with the findings of two of the above-referred studies in S.cerevisiae and in mouse lymphoma cells [39,41].However,it should be highlighted here,that among allFig.5.Mean frequencies (‰)of micronuclei (MN)per size,during 254nm UV photo-treatment of 2-CPY aqueous solutions.genotoxicity studies employing 2-CPY,our work is the only one that has evaluated 2-CPY genotoxic effects on human cells.In the present study,we have quantified the concentration of 2-CPY and we have investigated its genotoxicity after solution UV photo treatment of different time lengths.As can be seen in Figs.4and 5,a significant increase in large MN frequencies and a drop in CBPI value were noticed up to 240min of UV irradiation.An increase in both,small and large size MN frequencies were observed,indicating a possible clastogenic and aneugenic effect.The negative genotoxic results in our findings,the slight positive response of cytotoxic index as well as the decrease in large size MN frequency was observed after 600min of UV irradiation.The genotoxic activity of 2-CPY decreased only after prolonged UV irradiation far beyond the required for the removal of the orig-inal substrate (i.e.120min).The removal of the initially loaded 2-CPY was approximately 50%at 50min (i.e.50g ml −1actual 2-CPY concentration),70%at 120min (i.e.30g ml −1actual 2-CPY concentration),and over 95%at 300min.According to our previous genotoxicity findings [24],2-CPY is not genotoxic or cytotoxic at concentrations at or below 50g ml −1.In the current work,2-CPY concentration was lower than 50g ml −1in all but the first four treatments (t ≤120min)employed in the genotoxicity study.Thus,the mixture genotoxic-ity cannot be attributed to 2-CPY.The solution genotoxicity reached its maximum at 240min,as can be seen in Fig.4.As can be seen in the same figure,this is near the maximum 2-HPY concentration.The rate of genotoxicity reduction was significantly slower than the rate of 2-CPY removal.This could be attributed to other genotoxic prod-ucts,such as 2-HPY formed during 2-CPY photolytic treatment or due to synergistic effects between compounds present in the solu-tion.To our best knowledge there are no genotoxic effects reported for any of 2-CPY degradation products presented in Table 1.The genotoxicity of individual products formed during 2-CPY formation is currently researched in our laboratory.4.ConclusionsUV irradiation of aqueous solutions of 2-CPY results in 2-CPY fast de-halogenation,with a very rapid pH drop.A number of interme-diate products shown in Table 1were produced,which degraded upon solution prolonged photo-treatment thus resulting in com-plete TOC removal.Genotoxicity studies were performed using untreated and 254nm UV treated solutions without air purging,at solution nat-。