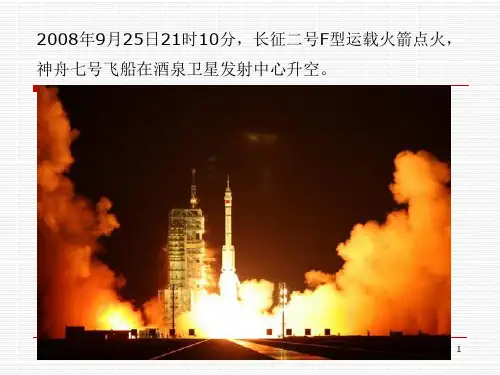

Laser Guide Star Adaptive Optics Integral Field Spectroscopy of a Tightly Collimated Bipola

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:610.87 KB

- 文档页数:11

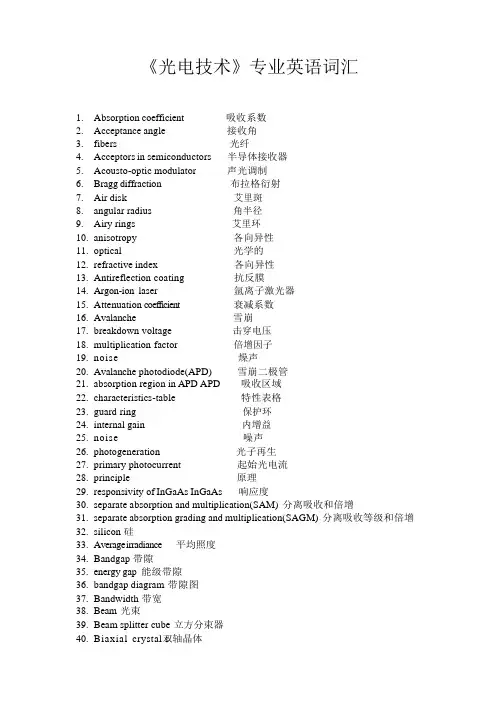

《光电技术》专业英语词汇1.Absorption coefficient 吸收系数2.Acceptance angle 接收角3.fibers 光纤4.Acceptors in semiconductors 半导体接收器5.Acousto-optic modulator 声光调制6.Bragg diffraction 布拉格衍射7.Air disk 艾里斑8.angular radius 角半径9.Airy rings 艾里环10.anisotropy 各向异性11.optical 光学的12.refractive index 各向异性13.Antireflection coating 抗反膜14.Argon-ion laser 氩离子激光器15.Attenuation coefficient 衰减系数16.Avalanche 雪崩17.breakdown voltage 击穿电压18.multiplication factor 倍增因子19.noise 燥声20.Avalanche photodiode(APD) 雪崩二极管21.absorption region in APD APD 吸收区域22.characteristics-table 特性表格23.guard ring 保护环24.internal gain 内增益25.noise 噪声26.photogeneration 光子再生27.primary photocurrent 起始光电流28.principle 原理29.responsivity of InGaAs InGaAs 响应度30.separate absorption and multiplication(SAM) 分离吸收和倍增31.separate absorption grading and multiplication(SAGM) 分离吸收等级和倍增32.silicon 硅33.Average irradiance 平均照度34.Bandgap 带隙35.energy gap 能级带隙36.bandgap diagram 带隙图37.Bandwidth 带宽38.Beam 光束39.Beam splitter cube 立方分束器40.Biaxial crystal双s 轴晶体41.Birefringent 双折射42.Bit rate 位率43.Black body radiation law 黑体辐射法则44.Bloch wave in a crystal 晶体中布洛赫波45.Boundary conditions 边界条件46.Bragg angle 布拉格角度47.Bragg diffraction condition 布拉格衍射条件48.Bragg wavelength 布拉格波长49.Brewster angle 布鲁斯特角50.Brewster window 布鲁斯特窗51.Calcite 霰石52.Carrier confinement 载流子限制53.Centrosymmetric crystals 中心对称晶体54.Chirping 啁啾55.Cladding 覆层56.Coefficient of index grating 指数光栅系数57.Coherence连贯性pensation doping 掺杂补偿59.Conduction band 导带60.Conductivity 导电性61.Confining layers 限制层62.Conjugate image 共轭像63.Cut-off wavelength 截止波长64.Degenerate semiconductor 简并半导体65.Density of states 态密度66.Depletion layer 耗尽层67.Detectivity 探测率68.Dielectric mirrors 介电质镜像69.Diffraction 衍射70.Diffraction g rating 衍射光栅71.Diffraction grating equation 衍射光栅等式72.Diffusion current 扩散电流73.Diffusion flux 扩散流量74.Diffusion Length 扩散长度75.Diode equation 二极管公式76.Diode ideality factor 二极管理想因子77.Direct recombinatio直n接复合78.Dispersion散射79.Dispersive medium 散射介质80.Distributed Bragg reflector 分布布拉格反射器81.Donors in semiconductors 施主离子82.Doppler broadened linewidth 多普勒扩展线宽83.Doppler effect 多普勒效应84.Doppler shift 多普勒位移85.Doppler-heterostructure 多普勒同质结构86.Drift mobility 漂移迁移率87.Drift Velocity 漂移速度88.Effective d ensity o f s tates 有效态密度89.Effective mass 有效质量90.Efficiency 效率91.Einstein coefficients 爱因斯坦系数92.Electrical bandwidth of fibers 光纤电子带宽93.Electromagnetic wave 电磁波94.Electron affinity 电子亲和势95.Electron potential energy in a crystal 晶体电子阱能量96.Electro-optic effects 光电子效应97.Energy band 能量带宽98.Energy band diagram 能量带宽图99.Energy level 能级100.E pitaxial growth 外延生长101.E rbium doped fiber amplifier 掺饵光纤放大器102.Excess carrier distribution 过剩载流子扩散103.External photocurrent 外部光电流104.Extrinsic semiconductors 本征半导体105.Fabry-Perot laser amplifier 法布里-珀罗激光放大器106.Fabry-Perot optical resonator 法布里-珀罗光谐振器107.Faraday effect 法拉第效应108.Fermi-Dirac function 费米狄拉克结109.Fermi energy 费米能级110.Fill factor 填充因子111.Free spectral range 自由谱范围112.Fresnel’s equations 菲涅耳方程113.Fresnel’s optical indicatrix 菲涅耳椭圆球114.Full width at half maximum 半峰宽115.Full width at half power 半功率带宽116.Gaussian beam 高斯光束117.Gaussian dispersion 高斯散射118.Gaussian pulse 高斯脉冲119.Glass perform 玻璃预制棒120.Goos Haenchen phase shift Goos Haenchen 相位移121.Graded index rod lens 梯度折射率棒透镜122.Group delay 群延迟123.Group velocity 群参数124.Half-wave plate retarder 半波延迟器125.Helium-Neon laser 氦氖激光器126.Heterojunction 异质结127.Heterostructure 异质结构128.Hole 空穴129.Hologram 全息图130.Holography 全息照相131.Homojunction 同质结132.Huygens-Fresnel principle 惠更斯-菲涅耳原理133.Impact-ionization 碰撞电离134.Index matching 指数匹配135.Injection 注射136.Instantaneous irradiance 自发辐射137.Integrated optics 集成光路138.Intensity of light 光强139.Intersymbol interference 符号间干扰140.Intrinsic concentration 本征浓度141.Intrinsic semiconductors 本征半导体142.Irradiance 辐射SER 激光144.active medium 活动介质145.active region 活动区域146.amplifiers 放大器147.cleaved-coupled-cavity 解理耦合腔148.distributed Bragg reflection 分布布拉格反射149.distributed feedback 分布反馈150.efficiency of the He-Ne 氦氖效率151.multiple quantum well 多量子阱152.oscillation condition 振荡条件ser diode 激光二极管sing emission 激光发射155.LED 发光二极管156.Lineshape function 线形结157.Linewidth 线宽158.Lithium niobate 铌酸锂159.Load line 负载线160.Loss c oefficient 损耗系数161.Mazh-Zehnder modulator Mazh-Zehnder 型调制器162.Macrobending loss 宏弯损耗163.Magneto-optic effects 磁光效应164.Magneto-optic isolator 磁光隔离165.Magneto-optic modulator 磁光调制166.Majority carriers 多数载流子167.Matrix emitter 矩阵发射168.Maximum acceptance angle 最优接收角169.Maxwell’s wave equation 麦克斯维方程170.Microbending loss 微弯损耗171.Microlaser 微型激光172.Minority carriers 少数载流子173.Modulated directional coupler 调制定向偶合器174.Modulation of light 光调制175.Monochromatic wave 单色光176.Multiplication region 倍增区177.Negative absolute temperature 负温度系数 round-trip optical gain 环路净光增益179.Noise 噪声180.Noncentrosymmetric crystals 非中心对称晶体181.Nondegenerate semiconductors 非简并半异体182.Non-linear optic 非线性光学183.Non-thermal equilibrium 非热平衡184.Normalized frequency 归一化频率185.Normalized index difference 归一化指数差异186.Normalized propagation constant 归一化传播常数187.Normalized thickness 归一化厚度188.Numerical aperture 孔径189.Optic axis 光轴190.Optical activity 光活性191.Optical anisotropy 光各向异性192.Optical bandwidth 光带宽193.Optical cavity 光腔194.Optical divergence 光发散195.Optic fibers 光纤196.Optical fiber amplifier 光纤放大器197.Optical field 光场198.Optical gain 光增益199.Optical indicatrix 光随圆球200.Optical isolater 光隔离器201.Optical Laser amplifiers 激光放大器202.Optical modulators 光调制器203.Optical pumping 光泵浦204.Opticalresonator 光谐振器205.Optical tunneling光学通道206.Optical isotropic 光学各向同性的207.Outside vapor deposition 管外气相淀积208.Penetration depth 渗透深度209.Phase change 相位改变210.Phase condition in lasers 激光相条件211.Phase matching 相位匹配212.Phase matching angle 相位匹配角213.Phase mismatch 相位失配214.Phase modulation 相位调制215.Phase modulator 相位调制器216.Phase of a wave 波相217.Phase velocity 相速218.Phonon 光子219.Photoconductive detector 光导探测器220.Photoconductive gain 光导增益221.Photoconductivity 光导性222.Photocurrent 光电流223.Photodetector 光探测器224.Photodiode 光电二极管225.Photoelastic effect 光弹效应226.Photogeneration 光子再生227.Photon amplification 光子放大228.Photon confinement 光子限制229.Photortansistor 光电三极管230.Photovoltaic devices 光伏器件231.Piezoelectric effect 压电效应232.Planck’s radiation distribution law 普朗克辐射法则233.Pockels cell modulator 普克尔斯调制器234.Pockel coefficients 普克尔斯系数235.Pockels phase modulator 普克尔斯相位调制器236.Polarization 极化237.Polarization transmission matrix 极化传输矩阵238.Population inversion 粒子数反转239.Poynting vector 能流密度向量240.Preform 预制棒241.Propagation constant 传播常数242.Pumping 泵浦243.Pyroelectric detectors 热释电探测器244.Quantum e fficiency 量子效应245.Quantum noise 量子噪声246.Quantum well 量子阱247.Quarter-wave plate retarder 四分之一波长延迟248.Radiant sensitivity 辐射敏感性249.Ramo’s theorem 拉莫定理250.Rate equations 速率方程251.Rayleigh criterion 瑞利条件252.Rayleigh scattering limit 瑞利散射极限253.Real image 实像254.Recombination 复合255.Recombination lifetime 复合寿命256.Reflectance 反射257.Reflection 反射258.Refracted light 折射光259.Refractive index 折射系数260.Resolving power 分辩力261.Response time 响应时间262.Return-to-zero data rate 归零码263.Rise time 上升时间264.Saturation drift velocity 饱和漂移速度265.Scattering 散射266.Second harmonic generation 二阶谐波267.Self-phase modulation 自相位调制268.Sellmeier dispersion equation 色列米尔波散方程式269.Shockley equation 肖克利公式270.Shot noise 肖特基噪声271.Signal to noise ratio 信噪比272.Single frequency lasers 单波长噪声273.Single quantum well 单量子阱274.Snell’s law 斯涅尔定律275.Solar cell 光电池276.Solid state photomultiplier 固态光复用器277.Spectral intensity 谱强度278.Spectral responsivity 光谱响应279.Spontaneous emission 自发辐射280.stimulated emission 受激辐射281.Terrestrial light 陆地光282.Theraml equilibrium 热平衡283.Thermal generation 热再生284.Thermal velocity 热速度285.Thershold concentration 光强阈值286.Threshold current 阈值电流287.Threshold wavelength 阈值波长288.Total acceptance angle 全接受角289.Totla internal reflection 全反射290.Transfer distance 转移距离291.Transit time 渡越时间292.Transmission coefficient 传输系数293.Tramsmittance 传输294.Transverse electric field 电横波场295.Tranverse magnetic field 磁横波场296.Traveling vave lase 行波激光器297.Uniaxial crystals 单轴晶体298.UnPolarized light 非极化光299.Wave 波300.W ave equation 波公式301.Wavefront 波前302.Waveguide 波导303.Wave n umber 波数304.Wave p acket 波包络305.Wavevector 波矢量306.Dark current 暗电流307.Saturation signal 饱和信号量308.Fringing field drift 边缘电场漂移plementary color 补色310.Image lag 残像311.Charge handling capability 操作电荷量312.Luminous quantity 测光量313.Pixel signal interpolating 插值处理314.Field integration 场读出方式315.Vertical CCD 垂直CCD316.Vertical overflow drain 垂直溢出漏极317.Conduction band 导带318.Charge coupled device 电荷耦合组件319.Electronic shutter 电子快门320.Dynamic range 动态范围321.Temporal resolution 动态分辨率322.Majority carrier 多数载流子323.Amorphous silicon photoconversion layer 非晶硅存储型324.Floating diffusion amplifier 浮置扩散放大器325.Floating gate amplifier 浮置栅极放大器326.Radiant quantity 辐射剂量327.Blooming 高光溢出328.High frame rate readout mode 高速读出模式329.Interlace scan 隔行扫描330.Fixed pattern noise 固定图形噪声331.Photodiode 光电二极管332.Iconoscope 光电摄像管333.Photolelctric effect 光电效应334.Spectral response 光谱响应335.Interline transfer CCD 行间转移型CCD336.Depletion layer 耗尽层plementary metal oxide semi-conductor 互补金属氧化物半导体338.Fundamental absorption edge 基本吸收带339.Valence band 价带340.Transistor 晶体管341.Visible light 可见光342.Spatial filter 空间滤波器343.Block access 块存取344.Pupil compensation 快门校正345.Diffusion current 扩散电流346.Discrete cosine transform 离散余弦变换347.Luminance signal 高度信号348.Quantum efficiency 量子效率349.Smear 漏光350.Edge enhancement 轮廓校正351.Nyquist frequency 奈奎斯特频率352.Energy band 能带353.Bias 偏压354.Drift current 漂移电流355.Clamp 钳位356.Global exposure 全面曝光357.Progressive scan 全像素读出方式358.Full frame CCD 全帧CCD359.Defect correction 缺陷补偿360.Thermal noise 热噪声361.Weak inversion 弱反转362.Shot noise 散粒噪声363.Chrominance difference signal 色差信号364.Colotremperature 色温365.Minority carrier 少数载流子366.Image stabilizer 手振校正367.Horizontal CCD 水平CCD368.Random noise 随机噪声369.Tunneling effect 隧道效应370.Image sensor 图像传感器371.Aliasing 伪信号372.Passive 无源373.Passive pixel sensor 无源像素传感器374.Line transfer 线转移375.Correlated double sampling 相关双采样376.Pinned photodiode 掩埋型光电二极管377.Overflow 溢出378.Effective pixel 有效像素379.Active pixel sensor 有源像素传感器380.Threshold voltage 阈值电压381.Source follower 源极跟随器382.Illuminance 照度383.Refraction index 折射率384.Frame integration 帧读出方式385.Frame interline t ransfer CCD 帧行间转移CCD 386.Frame transfer 帧转移387.Frame transfer CCD 帧转移CCD388.Non interlace 逐行扫描389.Conversion efficiency 转换效率390.Automatic gain control 自动增益控制391.Self-induced drift 自激漂移392.Minimum illumination 最低照度393.CMOS image sensor COMS 图像传感器394.MOS diode MOS 二极管395.MOS image sensor MOS 型图像传感器396.ISO sensitivity ISO 感光度。

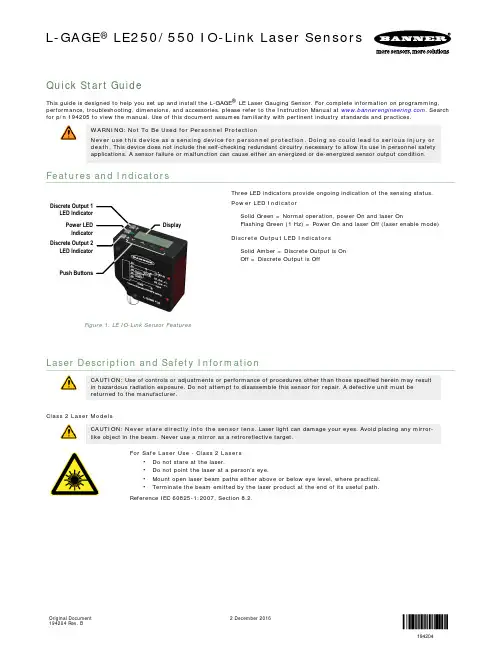

Quick Start GuideThis guide is designed to help you set up and install the L-GAGE ® LE Laser Gauging Sensor. For complete information on programming,performance, troubleshooting, dimensions, and accessories, please refer to the Instruction Manual at . Searchfor p/n 194205 to view the manual. Use of this document assumes familiarity with pertinent industry standards and practices.WARNING: Not To Be Used for Personnel ProtectionNever use this device as a sensing device for personnel protection. Doing so could lead to serious injury or death. This device does not include the self-checking redundant circuitry necessary to allow its use in personnel safety applications. A sensor failure or malfunction can cause either an energized or de-energized sensor output condition.Features and IndicatorsPower LED Indicator Discrete Output 1LED IndicatorDisplayDiscrete Output 2LED IndicatorPush ButtonsFigure 1. LE IO-Link Sensor FeaturesThree LED indicators provide ongoing indication of the sensing status.Power LED IndicatorSolid Green = Normal operation, power On and laser OnFlashing Green (1 Hz) = Power On and laser Off (laser enable mode)Discrete Output LED IndicatorsSolid Amber = Discrete Output is On Off = Discrete Output is OffLaser Description and Safety InformationCAUTION: Use of controls or adjustments or performance of procedures other than those specified herein may result in hazardous radiation exposure. Do not attempt to disassemble this sensor for repair. A defective unit must be returned to the manufacturer.Class 2 Laser ModelsCAUTION: Never stare directly into the sensor lens. Laser light can damage your eyes. Avoid placing any mirror-like object in the beam. Never use a mirror as a retroreflective target.For Safe Laser Use - Class 2 Lasers•Do not stare at the laser.•Do not point the laser at a person’s eye.•Mount open laser beam paths either above or below eye level, where practical.•Terminate the beam emitted by the laser product at the end of its useful path.Reference IEC 60825-1:2007, Section 8.2.L-GAGE ® LE250/550 IO-Link Laser SensorsOriginal Document 194204 Rev. B2 December 2016194204Class 2 LasersClass 2 lasers are lasers that emit visible radiation in the wavelength range from 400 nm to 700nm, where eye protection is normally afforded by aversion responses, including the blink reflex.This reaction may be expected to provide adequate protection under reasonably foreseeableconditions of operation, including the use of optical instruments for intrabeam viewing.Figure 2. FDA (CDRH) warning label(Class 2)Class 2 Laser Safety NotesLow-power lasers are, by definition, incapable of causing eye injury within the duration of a blink (aversion response) of 0.25 seconds. They also must emit only visible wavelengths (400 to 700nm). Therefore, an ocular hazard may exist only if individuals overcome their natural aversion to bright light and stare directly into the laser beam.Class 1 Laser ModelsClass 1 lasers are lasers that are safe under reasonably foreseeable conditions of operation,including the use of optical instruments for intrabeam viewing.Figure 3. FDA (CDRH) warning label(Class 1)Laser wavelength: 650 nmOutput: < 0.22 mWPulse Duration: 150 µs to 900 µsSensor InstallationNOTE: Handle the sensor with care during installation and operation. Sensor windows soiled by fingerprints, dust,water, oil, etc. may create stray light that may degrade the peak performance of the sensor. Blow the window clear using filtered, compressed air, then clean as necessary using 70% isopropyl alcohol and cotton swabs or water and a soft cloth.Sensor OrientationCorrect sensor-to-object orientation is important to ensure proper sensing. See the following figures for examples of correct and incorrect sensor-to-object orientation as certain placements may pose problems for sensing distances.Figure 4. Orientation by a wall IncorrectCorrectFigure 5. Orientation in an opening IncorrectCorrect Figure 6. Orientation for a turning object - Tel: +1-763-544-3164P/N 194204 Rev. BIncorrectCorrectFigure 7. Orientation for a height differenceIncorrectCorrect Figure 8. Orientation for a color or lusterdifference Figure 9. Orientation for a highly reflectivetargetApplying tilt to sensor may improve performance on reflective targets. The direction and magnitude of the tilt depends on the application,but a 15° tilt is often sufficient.Mount the Sensor1.If a bracket is needed, mount the sensor onto the bracket.2.Mount the sensor (or the sensor and the bracket) to the machine or equipment at the desired location. Do not tighten the mountingscrews at this time.3.Check the sensor alignment.4.Tighten the mounting screws to secure the sensor (or the sensor and the bracket) in the aligned position.Wiring Diagrams+–Figure 10. IO-Link ModelsKey11 = Brown2 = White3 = Blue4 = Black5 = GrayDisplayFigure 11. LE550 Display in Run ModeThe display is a 2-line, 8-character LCD. The main screen is the Run mode screen, which shows the real-time distance measurement.ButtonsUse the sensor buttons Down , Up , Enter , and Escape to program the sensor and to access sensor information.P/N 194204 Rev. B - Tel: +1-763-544-31643Down and Up ButtonsPress Down and Up to:•Access the Quick Menu from Run mode•Navigate the menu systems•Change programming settingsWhen navigating the menu systems, the menu items loop.Press Down and Up to change setting values. Press and hold the buttons to cycle through numeric values. After changing asetting value, it slowly flashes until the change is saved using the Enter button.Enter ButtonPress Enter to:•Access the Sensor Menu from Run mode•Access the submenus•Save changesIn the Sensor Menu, a check mark in the lower right corner of the display indicates that pressing Enter accesses asubmenu.Press Enter to save changes. New values flash rapidly and the sensor returns to the parent menu.Escape ButtonPress Escape to:•Leave the current menu and return to the parent menu•Return to Run mode from the Quick MenuImportant: Pressing Escape discards any unsaved programming changes.In the Sensor Menu, a return arrow in the upper left corner of the display indicates that pressing Escape returns to theparent menu.Press and hold Escape for 2 seconds to return to Run mode from any menu or remote teach.Sensor ProgrammingProgram the sensor using the buttons on the sensor or the remote input (limited programming options).From Run mode, use the buttons to access the Quick Menu and the Sensor Menu. See Quick Menu on page 4, Sensor Menu (MENU) on page 5, and the instruction manual (p/n 194205) for more information on the options available from each menu. For TEACH options, follow the TEACH instructions in the instruction manual.In addition to programming the sensor, use the remote input to disable the buttons for security, preventing unauthorized or accidental programming changes. See the instruction manual for more information.from Run ModeAccess Quick MenuAccess Sensor MenuSee Figure 13 on page 5See Figure 14 on page 6Figure 12. Accessing the MenusQuick MenuThe sensor includes a Quick Menu with easy access to view and change the discrete output switch points. Access the Quick Menu by pressing Down or Up from Run mode. When in the Quick Menu, the current distance measurement displays on the first line and the menu name and the discrete output switch points alternate on the second line of the display. Press Enter to access the switch points. Press Down or Up to change the switch point to the desired value. Press Enter to save the new value and return to the Quick Menu. - Tel: +1-763-544-3164P/N 194204 Rev. BQuick MenuFigure 13. Quick Menu Map (Window Mode)Sensor Menu (MENU)Access the Sensor Menu by pressing Enter from Run mode, when MENU is displayed. The Sensor Menu includes several submenus that provide access to view and change sensor settings and to view sensor information.P/N 194204 Rev. B - Tel: +1-763-544-31645LE Series User Interface Top Menu Sub MenusFigure 14. LE550 Sensor Menu Map SpecificationsSupply Voltage (Vcc)12 to 30 V dcPower and Current Consumption, exclusive of loadNormal Run Mode: 1.7 W, Current consumption < 70 mA at 24 V dc Supply/Output Protection CircuitryProtected against reverse polarity and transient overvoltages Sensing BeamClass 2 laser models: visible red, 650 nmClass 1 laser models: visible red, 650 nmSensing RangeLE250: 100 mm to 400 mm (3.94 to 15.75 inches) LE550: 100 mm to 1000 mm (3.94 to 39.37 inches) - Tel: +1-763-544-3164P/N 194204 Rev. BOutput ConfigurationD1_Out: IO-Link, Push/pull D2_Out: PNPOutput Ratings100 mA maximum capability each output Saturation: Less than 2 VOff-State Leakage Current: Less than 50 µA PNP at 30 V (N.A. push/pull)Remote InputAllowable Input Voltage Range: 0 to VccActive High (internal weak pulldown—sourcing current):High State > Vcc – 1.5 V dc Low State < Vcc – 5 V dc Input Impedance > 10 kOhmMeasurement/Output RateClass 2 Laser Models: < 1 msClass 1 Laser Models (Fast): < 1 msClass 1 Laser Models (Std/Medium/Slow): < 2 ms Minimum Window SizeLE250: 1 mm (0.039 inches)LE550: 10 mm (0.39 inches)BoresightingLE250: 4 mm radius at 400 mm LE550: 1 cm radius at 1 m Maximum Torque2 N·m (17.7 in-lbs)IndicatorsPower LED IndicatorSolid Green = Normal operation, power On and laser OnFlashing Green (1 Hz) = Power On and laser Off (laser enable mode)Discrete Output LED Indicator Solid Amber = Discrete Output is On Off = Discrete Output is Off ConstructionHousing: die-cast zinc Window: acrylicTypical Beam Spot Size1IO-Link InterfaceSupports Smart Sensor Profile: Yes Baud Rate: 38400 bpsProcess Data Widths: 32 bitsIODD files: Provides all programming options of the display, plus additional functionality Ambient Light ImmunityClass 2 laser models: > 10,000 lux Class 1 laser models: > 5,000 lux Response TimeDelay at Power Up3 s RepeatabilitySee Performance Curves Temperature EffectSee Performance CurvesEnvironmental RatingIEC IP67, NEMA 6Operating Conditions−20 °C to +55 °C (−4 °F to +131°F)90% at +55 °C maximum relative humidity (non-condensing)Storage Temperature−30 °C to +65 °C (−22 °F to +149 °F)Vibration/Mechanical ShockAll models meet Mil. Std. 202 G requirements method 201A. Also meets IEC 60947-5-2.Application NoteFor optimum performance, allow 10 minutes for the sensor to warm up CertificationsIndustrial ControlEquipment 3TJJUL Environmental Rating: Type 1Required Overcurrent ProtectionWARNING: Electrical connections must be made by qualified personnel in accordance with local and national electrical codes and regulations.Overcurrent protection is required to be provided by end product application per the supplied table.Overcurrent protection may be provided with external fusing or via Current Limiting, Class 2 Power Supply.Supply wiring leads < 24 AWG shall not be spliced.For additional product support, go to .σ measured valueP/N 194204 Rev. B - Tel: +1-763-544-31647Performance Curves0.60.50.40.30.20.10100200300DISTANCE (mm)R E P E A T A B I L I T Y ( ± m m )400Figure 15. Repeatability (90% to 6% reflectance)123456782000DISTANCE (mm)R E P E A T A B I L I T Y ( ± m m )4006008001000Figure 16. Repeatability (90% to 6% reflectance)0.1500.1000.1250.0750.0500.0250.0300100200300400DISTANCE (mm)T e m p e r a t u r e E f f e c t (± m m / °C )Figure 17. Temperature Effect0.60.40.50.30.20.10200DISTANCE (mm)T e m p e r a t u r e E f f e c t (± m m / °C )4006008001000Figure 18. Temperature EffectBanner Engineering Corp. Limited WarrantyBanner Engineering Corp. warrants its products to be free from defects in material and workmanship for one year following the date of shipment. Banner Engineering Corp. will repair or replace, free of charge, any product of its manufacture which, at the time it is returned to the factory, is found to have been defective during the warranty period. This warranty does not cover damage or liability for misuse, abuse, or the improper application or installation of the Banner product.THIS LIMITED WARRANTY IS EXCLUSIVE AND IN LIEU OF ALL OTHER WARRANTIES WHETHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED (INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE), AND WHETHER ARISING UNDER COURSE OF PERFORMANCE, COURSE OF DEALING OR TRADE USAGE.This Warranty is exclusive and limited to repair or, at the discretion of Banner Engineering Corp., replacement. IN NO EVENT SHALL BANNER ENGINEERING CORP. BE LIABLE TO BUYER OR ANY OTHER PERSON OR ENTITY FOR ANY EXTRA COSTS, EXPENSES, LOSSES, LOSS OF PROFITS, OR ANY INCIDENTAL, CONSEQUENTIAL OR SPECIAL DAMAGES RESULTING FROM ANY PRODUCT DEFECT OR FROM THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THE PRODUCT, WHETHER ARISING IN CONTRACT OR WARRANTY, STATUTE, TORT, STRICT LIABILITY,NEGLIGENCE, OR OTHERWISE.Banner Engineering Corp. reserves the right to change, modify or improve the design of the product without assuming any obligations or liabilities relating to any product previously manufactured by Banner Engineering Corp. Any misuse, abuse, or improper application or installation of this product or use of the product for personal protection applications when the product is identified as not intended for such purposes will void the product warranty. Any modifications to this product without prior express approval by Banner Engineering Corp will void the product warranties. All specifications published in this document are subject to change; Banner reserves the right to modify product specifications or update documentation at any time. Specifications and product information in English supersede that which is provided in any other language. For the most recent version of any documentation, refer to: .© Banner Engineering Corp. All rights reserved。

Wavefront Sensing and Adaptive Optics自从人类开始观测天空以来,我们一直在努力寻找更好的方法来提高望远镜的性能,以便更清晰地观察宇宙中的奇妙景象。

在这个过程中,波前感知和自适应光学技术成为了一个重要的突破。

波前感知是一种用于测量光波传播中的畸变的技术。

当光波通过大气层时,会受到大气湍流的影响,导致光波的形状发生扭曲。

这种扭曲会降低望远镜的分辨率和图像质量。

波前感知技术通过使用传感器来测量光波的形状变化,并将这些信息传递给自适应光学系统,来纠正光波的畸变。

自适应光学是一种根据波前感知的信息来实时调整望远镜的光学元件的技术。

它使用一种叫做变形镜的设备来纠正光波的畸变。

变形镜是由许多微小的可调节镜片组成的,这些镜片可以根据波前感知的数据来微调其形状,以便纠正光波的畸变。

通过不断地调整变形镜的形状,自适应光学系统可以实时地纠正光波的畸变,从而提高望远镜的分辨率和图像质量。

波前感知和自适应光学技术的应用非常广泛。

它们被广泛应用于天文学领域,以提高望远镜的观测性能。

通过使用波前感知和自适应光学技术,天文学家们能够观测到更细节丰富的天体图像,例如行星表面的细微结构、恒星的变化和星系的形态。

这些观测结果对于理解宇宙的演化和了解宇宙中的各种物理过程非常重要。

除了天文学领域,波前感知和自适应光学技术还被应用于其他领域,如医学成像、激光通信和材料加工等。

在医学成像中,波前感知和自适应光学技术可以提高医学影像的分辨率,从而帮助医生更准确地诊断疾病。

在激光通信中,这些技术可以提高光信号的传输质量和距离。

在材料加工中,波前感知和自适应光学技术可以提高激光加工的精度和效率。

尽管波前感知和自适应光学技术在许多领域都取得了巨大的成功,但它们仍然面临一些挑战和限制。

首先,波前感知需要高精度的传感器来测量光波的形状变化,这对于一些应用来说可能是昂贵的。

其次,自适应光学系统需要高速的计算和控制系统来实时调整变形镜的形状,这对于一些实时性要求很高的应用来说可能是困难的。

LASER INTERFEROMETER GRAVITATIONAL WAVE OBSERVATORY LIGO Laboratory / LIGO Scientific CollaborationLIGO-E960050-v4 Advanced LIGO12 Nov 2009 see DCC record for approvalLIGO Vacuum Compatible Materials ListD. Coyne (ed.)Distribution of this document:LIGO Science CollaborationThis is an internal working noteof the LIGO Project.California Institute of Technology LIGO Project – MS 18-341200 E. California Blvd.Pasadena, CA 91125Phone (626) 395-2129Fax (626) 304-9834E-mail:*****************.edu Massachusetts Institute of Technology LIGO Project – NW17-161175 Albany StCambridge, MA 02139Phone (617) 253-4824Fax (617) 253-7014E-mail:*************.eduLIGO Hanford Observatory P.O. Box 1970Mail Stop S9-02Richland WA 99352Phone 509-372-8106Fax 509-372-8137LIGO Livingston ObservatoryP.O. Box 940Livingston, LA 70754Phone 225-686-3100Fax 225-686-7189/CHANGE RECORDRevisionDateAuthority DescriptionA30 Jul 1996Initial Release Initial ReleaseB/v1 5 Apr 2004DCNE030570-01 Added approved materials for initial LIGO, clarified the designation "presently used", or "provisional" materials, added independent approval for Initial LIGO and AdvancedLIGO approval.v2 9 Sep 2009See DCC record ∙ Removed distinction between initial and advanced LIGO for approval∙ Made an explicit notation in the materials list if the use of a material is restricted (or not)∙ Moved a number of materials from the provisionally approved to the approved list, although in some cases with restrictions (e.g. carbon steel, Sm-Co, Nd-Fe-B, Vac-Seal, copper, Tin-Lead solder, etc.) and removed the provisional list from the document∙ Added a number of materials to the approved list, although in some cases with restrictions (e.g. adhesives,aluminum bronze, etc.) ∙ Added a few materials to the explicitly excluded list, e.g.aluminum alloy 7000 series, brass (aka manganese bronze), free-machining grades of stainless steel (303, 303S, 303Se) except as small fasteners, etc. ∙ Added a number of references∙ Added a section on general restrictions on materials (e.g. no castings, material certifications are always required, only the grades and sources called out for the polymers are permitted, etc.)∙ Most outgassing rate values remain blank in the materials list (pending)v3 16 Sep 2009 See DCCrecord∙ Added SEI-ISI actuators to approved list∙ Clarified that no castings refers to metals only∙ Added exception for the use of grinding to prepare the leads for in-vacuum photodiodes ∙ Added numbers to the rows of the approved materials list for easier reference∙ Added the grade and source for PEEK and carbon-loaded PEEKV4 12 Nov 2009See DCC record ∙ Explicitly added the Ferritic Stainless Steels (400 series) to the approved materials list. Of high vapor pressureelements, these alloys have 0.06% P max and 0.15% S max, which is well under the 0.5% max allowed inLIGO-L080072-00 [Ref. b )7]TABLE OF CONTENTS1Introduction (4)2Scope (4)3Nomenclature and Acronyms (4)4Ultra-High Vacuum Material Concerns (5)5Vacuum Requirements (5)6Procedure for Qualifying New Materials (6)7VRB wiki Log (6)8General Restrictions (6)9Approved Materials (7)10Explicitly Rejected Materials (20)11References for the approved materials table (20)LIST OF TABLESTable 1: Approved Construction Materials (8)1 IntroductionAll items to be installed inside LIGO Observatory vacuum systems must be on the "approved materials" list (components and materials).2 ScopeThe materials listed herein are those which are intended for use in vacuum. Materials used for items which are temporarily inside a LIGO vacuum system, but do not reside in vacuum (e.g. alignment fixtures, installation tooling, etc.) are not restricted to this material list. These items (referred to as "Class B"1 as opposed to "Class A" items which remain in the vacuum system) must comply with LIGO cleanliness standards and must not leave residues of non-vacuum compatible materials (e.g. hydrocarbon lubricants).3 Nomenclature and AcronymsLIGOAdL AdvancedADP Ammonium Di-hydrogen Phosphate [(NH4)H2PO4]AES Auger Electron SpectroscopyAMU Atomic Mass UnitFTIR Fourier Transform Infrared SpectroscopyHC HydrocarbonsLIGOInL InitialKDP Potassium Di-hydrogen Phosphate [KH2PO4]LIGO Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave ObservatoryOFHC Oxygen Free High-Conductivity CopperNEO Neodymium Iron BoronPFA Perfluoroalkoxy fluoropolymer (Du Pont)PTFE Polytetrafluorethylene (Du Pont)PZT Lead-Zirconate-TitanateRTV Room Temperature Vulconizing Silicone elastomerSIMS Stimulated Ion Mass SpectroscopyUHV Ultra High VacuumVRB LIGO Vacuum Review BoardXPS X-ray Photoelectric Spectroscopy1 Betsy Bland (ed.), LIGO Contamination Control Plan, LIGO-E09000474 Ultra-High Vacuum Material ConcernsThere are two principal concerns associated with outgassing of materials in the LIGO vacuum system:a)Outgassing increases the gas load (and column density) in the system and consequently mayeither compromise the interferometer phase noise budget or require higher pumping capacity. Reduction with time, whether 1/t (range of adsorption energies) or 1/sqrt(t) (diffusion followed by desorption) is important and the particular gas species (whether condensable or non-condensable) is critical. Even inherently compatible, low outgassing materials (e.g. 6061 aluminum alloy) will contribute to the gas load (especially if not properly cleaned and/or copious amounts are installed into the vacuum system). However, the most significant risk is likely to be from materials which have inherently high outgassing rates (e.g. water outgassing from flouroelastomers such as Viton® and Flourel®).The literature is most useful in providing total and water outgassing rates. Since in LIGO, there is a special problem of larger phase noise sensitivity to (and concern of optical contamination from) heavy hydrocarbons, where possible, the hydrocarbon outgassing or surface contamination information should be provided.b)Outgassing is a potential source of contamination on the optics with the result of increasedoptical losses (scatter and absorption) and ultimately failure due to heating. The amount of outgassing is less important than the molecular species that is outgassed. Little is known of the most important contamination sources or the mechanisms that lead to the optical loss(e.g., UV from second harmonic generation, double photon absorption photoeffect, simplemolecular decomposition in the optical fields leaving an absorbing residue, etc.).In the approved materials list, one column entry indicates whether the listed material has the potential for (is suspected of) being a significant contributor as regards a) or b) or both.5 Vacuum RequirementsAn allocation of high molecular weight hydrocarbon outgassing budget to assemblies within the AdL UHV is given in LIGO-T0400012. However, this document is in need of revision (a) to reflect the pumping capacity of the beam tube (which reduces the requirements considerably), and (b) to more accurately reflect the evolved AdL configuration.An allocation of total gas load for AdL has not been made as yet. With the elimination of the significant amount of Flourel® flouroelastomer in InL (spring seats, parts of the InL seismic isolation system), the water load will decrease dramatically. However, recent calculations3 of test mass damping due to residual gas suggest that this may not be sufficient. We will need to achieve a total pressure of 10-9 torr or less in proximity to each test mass. A total gas load budget/estimate will be created.The limits on optical loss due contamination are < 1 ppm/yr absorption and < 4 ppm/yr scatter loss2 D. Coyne, Vacuum Hydrocarbon Outgassing Requirements, LIGO-T0400013 N. Robertson, J. Hough, Gas Damping in Advanced LIGO Suspensions, LIGO-T0900416-v1for any test mass (TM), high reflectance (HR), surface4.6 Procedure for Qualifying New MaterialsA request to qualify a new material or component/assembly should be addressed to the LIGO Chief Engineer or the LIGO Vacuum Review Board with a justification regarding the need for the new material and an estimate of the amount of material required. Materials can only be added to the "approved" list after extensive testing in accordance with the document "LIGO Vacuum Compatibility, Cleaning Methods and Procedures"5.7 VRB wiki LogThis revision captures all relevant LIGO Vacuum Review Board (VRB) decisions as of the date of this release. For more recent direction not yet captured in a revision of this document, see the LIGO VRB wiki log (access restricted to LSC members).8 General Restrictions1)Material certifications are required in every case.2)Only the grades called out3)Only the grades and sources called out for the polymers (unless otherwise noted).4)All polymers are restricted (even if approved). The use of an approved polymer in a newapplication must be approved. Despite the fact that some polymer materials are approved for use, these materials should be avoided if possible and used sparingly, especially if used in proximity to LIGO optics.5)Special precautions must be taken for adhesives. Often the shelf life for adhesives islimited. All adhesives should be degassed as part of the preparation procedure. Extreme care must be taken when mixing multi-part adhesives, to insure that the proper ratio is used and accurately controlled.6)No metal castings, including no aluminum tooling plate.7)All surfaces are to be smooth (preferably ≤ 32 micro inches Ra). All metal surfaces areideally machined.8)All machining fluids must be fully synthetic (water soluble, not simply water miscible) andfree of sulfur, chlorine, and silicone.9)No bead or sand blasting is permitted.4 G. Billingsley et. al., Core Optics Components Design Requirements Document, section 4.2.2.6 of LIGO-T080026-00. The timescale for accumulation (i.e. the time span between in situ re-cleaning of the test mass optics) has been chosen here to be 1 year. It is possible that a somewhat shorter time span could be accommodated.5 D. Coyne (ed.), LIGO Vacuum Compatibility, Cleaning Methods and Qualification Procedures, LIGO-E96002210)No grinding is permitted (due to potential contamination from the grinding wheel matrix),except for (a) grinding maraging steel blades to thickness6 and (b) photodiode lead end preparation for pin sockets.11)Parts should be designed and fabricated to provide venting for enclosed volumes12)For design applications where dimensional control is extremely important or tolerances areexceedingly tight, it is the responsibility of the design engineer to (a) establish a basis for baking parts at temperatures lower than the default temperatures (defined in LIGO-E960022), and (b) get a waiver for a lower temperature bake from the LIGO Vacuum Review Board.13)All materials must be cleaned with appropriate chemicals and procedures (defined in LIGO-E960022) and subsequently baked at “high temperature”. The appropriate temperature is defined in LIGO-E960022. Typical hold duration at temperature is 24 hours. The preferred bake is in a vacuum oven so that the outgassing rate can be shown to be acceptable by Residual Gas Assay (RGA) measurement with a mass spectrometer. If the part is too large to be placed in a vacuum oven, then it is air baked (or dry nitrogen baked) and then its surface cleanliness is established by FTIR measurement.14)Welding, brazing, soldering have special restrictions and requirements7 defined in LIGO-E0900048.15)For commercially produced components with potentially many materials used in theconstruction, a detailed accounting of all of the materials and the amounts used must be submitted for review. It may be necessary for some components to get certifications (per article or serial number) of the materials employed in their manufacture, so that material substitutions by the manufacturer are visible to LIGO.9 Approved MaterialsThe following Table lists materials which are approved for use in all LIGO vacuum systems. In many cases the materials are restricted to a particular application. Use of the material for another application must be approved by either the LIGO Chief Engineer or the LIGO Vacuum Review Board. References for the approved materials list table are given in the last section.6 C. Torrie et. al., Manufacturing Process for Cantilever Spring Blades for Advanced LIGO, LIGO-E09000237 C. Torrie, D. Coyne, Welding Specification for Weldments used within the Advanced LIGO Vacuum System, LIGO-E0900048LIGO LIGO-E960050-v410 Explicitly Rejected Materials1)Alkali metals2)Aluminum alloy 7000 series: due to the high zinc content3)Brass (aka manganese bronze): due to high zinc content4)Cadmium or zinc plating on metal parts: Cadmium and zinc have prohibitively high vapourpressures. Crystalline whiskers grow on cadmium, can cause short circuits.5)Delrin™ or similar polyacetal resin plastics: Outgassing products known to contaminatemirrors.6)Dyes7)Epoxy Tra-Bond 2101: outgassing was measured by LIGO to be too high (note that this isnot a low outgassing epoxy formulation)8)Inks9)Manganese bronze (aka brass): due to high zinc content10)Oils and greases for lubrication11)Oilite™ or other lubricant-impregnated bearings12)Oriel MotorMike™ actuators filled with hydrocarbon oil, not cleanable13)Palladium14)Soldering flux15)Stainless Steel, free-machining grades (303, 303S, 303Se): allowable only as smallhardware components (nuts, bolts, washers), due to high sulfur or selenium content16)RTV Type 61517)Tellurium11 References for the approved materials table1.Dayton, B.B. (1960) Trans. 6th Nat. Vacuum Congress; p 1012.Schram, A. (1963) Le Vide, No 103, p 553.Holland, Steckelmacher, Yarwood (1974) Vacuum Manual4.Lewin, G. (1965) Fundamentals of Vacuum Science and Technology, p 725.Coyne, D., Viton Spring Seat Vacuum Bake Qualification, LIGO-T970168-00, 10 Oct 1997.6.Coyne, D., Allowable Bake Temperature for UHV Processing of Copper Alloys, LIGO-T0900368-v2, 11 Aug 2009.7.Worden, J., Limits to high vapor pressure elements in alloys, LIGO- L080072-00, 12 Sep 2008.8.Coyne, D., VRB Response to L070131-00: Unacceptability of 7075 Aluminum Alloy in theLIGO UHV?,LIGO-, LIGO-L070132-00, 11 Nov 2008.20LIGO LIGO-E960050-v49.Worden, J., VRB response to L080042-00, Is 303 stainless steel acceptable in the LIGOVacuum system?, LIGO-L080044-v1, 12 Jan 2009.10.Worden, J., VRB response to nickel-phosphorous plating issues , LIGO-L0900024-v1, 20 Feb2009.11.Torrie, C. et. al., Manufacturing Process for Cantilever Spring Blades for Advanced LIGO,LIGO-E0900023-v6, 23 Jun 2009.12.Worden, J., VRB Response to Flourel/Viton O-ring questions, LIGO-L070086-00, 12 Oct2007.13.Coyne, D. (ed), LIGO Vacuum Compatibility, Cleaning Methods and Qualification Procedures,LIGO- E96002214.Process Systems International, Inc., Specification for Viton Vacuum Bakeout, LIGO VacuumEquipment - Hanford and Livingston, LIGO- E960159-v1, 18 Dec 1996.15.Coyne, D., Component Specification: Material, Process, Handling and Shipping Specificationfor Fluorel Parts, LIGO-E970130-A, 17 Nov 1997.16.Process Systems International, Inc., WA Site GNB Valve Modification Report Update (PSIV049-1-185) and LA Mid Point Valve O-Ring Specification, LIGO-C990061-00, 21 Jan 1999.17.Process Systems International, Inc., Vacuum Equipment: O Ring Specification, Rev. 06, LIGO-E960085-06, 7 Jan 1997.18.ASTM, Standard Specification for Steel Wire, Music Spring Quality, A 228/A 228M – 07.19.Worden, J., Re: L0900002-v1: VRB request: all SmCo magnets UHV compatible?, LIGO-L0900011-v1, 3 Feb 2009.20.C. Torrie, et. al., Summary of Maraging Steel used in Advanced LIGO, LIGO-T090009121。

a rXiv:as tr o-ph/1327v12Mar21Planetary Systems in the Universe:Observation,Formation and Evolution ASP Conference Series,Vol.3×108,2000A.J.Penny,P.Artymowicz,grange,and S.S.Russell,eds.An Adaptive Optics Survey for Companions to Stars with Extra-Solar Planets James P.Lloyd,Michael C.Liu,James R.Graham,Melissa Enoch,Paul Kalas,Geoffrey W.Marcy,Debra Fischer Department of Astronomy,University of California,Berkeley,CA 94720,USA Jennifer Patience,Bruce Macintosh,Donald T.Gavel,Scot S.Olivier,Claire E.Max Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics,Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,Livermore,CA 95064,USA Russel White,Andrea M.Ghez,Ian S.McLean Department of Physics and Astronomy,University of California,Los Angeles,CA 90095,USA Abstract.We have undertaken an adaptive optics imaging survey of extrasolar planetary systems and stars showing interesting radial veloc-ity trends from high precision radial velocity searches.Adaptive Optics increases the resolution and dynamic range of an image,substantially improving the detectability of faint close companions.This survey is sen-sitive to objects less luminous than the bottom of the main sequence at separations as close as 1′′.We have detected stellar companions to the planet bearing stars HD 114762and Tau Boo.We have also detected a companion to the non-planet bearing star 16Cyg A.1.IntroductionThe Lick Adaptive Optics System is a Shack-Hartmann Laser Guide star AO system on the Lick Observatory Shane 3m telescope at Mt Hamilton,California (Max et al.1997).For these observations,we used the system in natural guide star mode,with the bright star serving as wavefront reference.Under good conditions,the system produces diffraction limited images (0.′′15FWHM)with a strehl ratio of 0.7in the K band (2.2µm).The AO system feeds a 256×256pixel infrared camera,IRCAL (Lloyd et al.2000),which reimages the field of view at 0.′′076per pixel.The camera incorporates a cold focal plane with an occulting finger to obtain high dynamic range images.For this program,we typically take a few minutes of integration of unsaturated images to obtain coverage close to the star,and deep exposures in coronagraphic mode to detect faint companions at larger separations.We have selected targets from those stars with radial velocity planets,or with radial velocity trends from the Lick and Keck radial velocity surveys.12J.P.Lloyd et al.2.ResultsHD155423(see Fig1)shows substantial scatter in precision radial velocity measurements.High resolution imaging shows HD155423is a hierarchical triple, with a0.′′2close binary(8AU projected separation)M3dwarf pair,separated1.′′5from the F8dwarf primary.A faint object was previously discovered near16Cyg A,but was not known to be physically associated(Hauser&Marcy1999).We have confirmed by proper motion measurements that the∆K=5.4object is a physically associated M5dwarf(see Fig1).Radial velocity measurements show a shallow linear trend.HD114762has a radial velocity companion with an84day period and Msin i=11M Jup(Latham et al.1989).We have detected a∆K=7.3compan-ion3.′′3from the primary(see Fig1).JHK photometry and follow up Keck AO/NIRSPEC spectroscopy(McLean et al.2000)reveal the companion to be a late M subdwarf.The physical association of this companion is confirmed by proper motion over a2year baseline(Patience et al.1998).Radial velocity measurements of HR6623show a nearly linear trend over 13years(see Fig1).This would classify this object as a poorly determined single lined spectroscopic binary.AO imaging resolves the companion,which is an M5dwarf.Further radial velocity and astrometric observations will allow accurate mass determinations.Tau Boo hosts an Msin i=3.9M Jup,3.3day period planet,and shows radial velocity residuals(see Fig1).It has an M2V companion that was discovered in1849at10.′′3.At present it is at2.′′82,with0.′′01per year of orbital motion. Although it has been suggested that there may be additional companions in the system(Wiedemann,Deming,&Bjoraker2000),we do not detect any additional companions,and attribute the velocity residuals to the stellar companion.Acknowledgments.This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation under a cooperative agreement with the Center for Adaptive Optics,Agreement No.AST-987678.Work on the Lick adaptive optics system was performed in part under the auspices of the U.S.Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory,Contract number W-7405-ENG-48 ReferencesCochran,W.,Hatzes,A.,Butler,R.P.&Marcy,G.W.1997,ApJ,483,457 Hauser,H.M.&Marcy,G.W.1999,PASP,111,321Latham,D.,Stefanik,R.,Mazeh,T.,et al.1989,Nature,339,38Lloyd,J.P.,Liu,M.C.,Macintosh,B.A.,Severson,S.A.,Deich,W.T.S.& Graham J.R.2000,in Proc.SPIE4008,Optical and IR Telescope Instrumen-tation and Detectors,ed.M.Iye&A.F.Moorwood,(Washington:SPIE) Max,C.E.,Olivier,S.S.,Friedman,H.W.,et al.,Science,277,1649 McLean,I.S.Wilcox,M.K.,Becklin,E.E.et al.2000,ApJ,533,L45 Patience,J.,Ghez,A.M.,White,R.J.et al.1998,BAAS,193,9708 Wiedemann,G.,Deming,D.,Gjoraker,G.2000,astro-ph/0007216APS Conf.Ser.Style3Time (Years) V e l o c i t y (m /s )Time (Years)V e l o ci t y (m s −1)HD 114762B: NIRSPEC/Keck AOF l u xFigure 1.K band images of stars with detected companions;J band spectra of HD 114762B;Radial Velocity data for HR 6623and Tau Boo (residual)。

应用光学(applied optics) 中英对照复习资料第1章1、光学研究分为两类:物理光学和几何光学.There are two aspects of people’s study of light: physical optics and geometrical optics. 2、光实际是电磁波.light is an electromagnetic wave3、光具有波粒2象性: a kind of matter with wave-particle duality, namely it has the characteristics of both the waves and the corpuscles.4、可见光visible light波长范围:400nm~760nm5、光速、频率、波长关系the relation among the speed of light, the frequency and wavelength ofcand electromagnetic wave.:,, ,6、波面wavefront是所有光线的垂直perpendicular surface曲面。

或光线垂直于波面:rays are perpendicular to wavefront.典型波面:同心光束concentric beam波面为球面sphere(spherical surface);像散光束astigmatic beam波面为非球面aspheric shape(aspheric surface);平行光束parallel beam波面为平面plane(plain surface)。

7、几何光学基本定律。

Basic laws of geometrical optics1)直线传播定律:光线在均匀透明介质中按直线传播。

The law of rectilinear propagation: rays propagate along straight lines in a homogeneous and transparent medium.2)反射定律:the law of reflection(1)反射光线位于入射面内。

optics and lasers in engineering模板Optics and Lasers in EngineeringIntroduction:Optics and lasers play a vital role in various engineering disciplines, revolutionizing industries and applications across the board. From manufacturing to telecommunications, these technologies have significantly advanced our capabilities and opened up new frontiers. In this article, we will step-by-step explore the fundamental concepts and practical applications of optics and lasers in engineering.1. Understanding Optics:Optics is the branch of physics that deals with the behavior and properties of light. It explores how light interacts with matter and how we can manipulate it to our advantage. At its core, optics focuses on two fundamental concepts - reflection and refraction.1.1 Reflection:Reflection occurs when a light ray strikes a surface and bounces back. The angle of incidence (the angle between the incident beam and the normal line) is always equal to the angle of reflection (the angle between the reflected beam and the normal line). This property of light is extensively utilized in engineering for applications like mirrors, optical sensors, and laser beam alignment.1.2 Refraction:Refraction is the bending of light as it passes from one medium to another. This bending is due to the change in the speed of light in different materials. The amount of bending depends on the angle of incidence and the refractive indices of the two materials involved. Engineers employ this phenomenon in lenses, optical fibers, and various devices used in imaging, such as cameras, microscopes, and telescopes.2. Essentials of Lasers:A laser (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) is a device that emits a coherent beam of light through a processcalled stimulated emission. Understanding the fundamentals of lasers is crucial in engineering, as they are widely used across multiple fields.2.1 Stimulated Emission:Stimulated emission occurs when an incoming photon interacts with atoms or molecules in an active medium, causing them to emit a photon identical in energy, phase, and direction to the incident photon. This results in the amplification of the light, leading to the creation of a coherent laser beam.2.2 Laser Components:Lasers consist of several key components, including an active medium (such as a solid-state crystal, gas, or semiconductor material), an optical cavity (to contain and control the light), and a pump source (to provide energy to the active medium). The combination and arrangement of these components determine the laser's properties, such as wavelength, power, and beam characteristics.3. Applications of Optics and Lasers:Now that we have covered the basics, let's delve into the diverse applications of optics and lasers in engineering.3.1 Manufacturing and Material Processing:Lasers have revolutionized manufacturing processes, offering advantages such as precision, speed, and versatility. Laser cutting and welding are widely used in industries like automotive, aerospace, and electronics. Optical metrology techniques ensure accurate measurements and quality control, further enhancing production efficiency.3.2 Telecommunications:Optical fibers, which rely on the principles of total internal reflection, are the backbone of modern telecommunications. These ultra-thin fibers can carry vast amounts of data over long distances, providing high-speed communication channels for internet connectivity, cable television, and telephone networks.3.3 Medical Applications:Lasers have transformed medical procedures and diagnostics. They are used for precise surgeries, such as laser eye surgery and cosmetic procedures. Laser-based imaging techniques, like optical coherence tomography (OCT) and laser-induced fluorescence, aid in diagnosing diseases and monitoring treatment effectiveness.3.4 Remote Sensing and Imaging:Optics and lasers enable remote sensing technologies, such as LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), used in topographic mapping, environmental monitoring, and autonomous vehicles. Additionally, imaging technologies like holography, infrared imaging, and laser scanners are employed in fields ranging from digital photography to biomedical imaging.Conclusion:Optics and lasers are indispensable tools in various engineering disciplines. Their principles and applications have transformedindustries and opened up endless possibilities for technological advancements. As engineers continue to innovate and harness the power of optics and lasers, we can expect even more remarkable developments in the near future.。

Adaptive Optics for Vision Science: Principles, Practices, Designand ApplicationsJason Porter, Abdul Awwal, Julianna LinHope Queener, Karen Thorn(Editorial Committee)Updated on June 30, 2003−Introduction1.Introduction (David Williams)University of Rochester1.1 Goals of the AO Manual (This could also be a separate preface written by the editors)* practical guide for investigators who wish to build an AO system* summary of vision science results obtained to date with AO1.2 Brief History of Imaging1.2.1 The evolution of astronomical AOThe first microscopes and telescopes, Horace Babcock , military applications during StarWars, ending with examples of the best AO images obtained to date. Requirements forastronomical AO1.2.2 The evolution of vision science AOVision correction before adaptive optics:first spectacles, first correction of astigmatism, first contact lenses, Scheiner and thefirst wavefront sensor.Retinal imaging before adaptive optics:the invention of the ophthalmoscope, SLO, OCTFirst AO systems: Dreher et al.; Liang, Williams, and Miller.Comparison of Vision AO and Astronomical AO: light budget, temporal resolutionVision correction with AO:customized contact lenses, IOLs, and refractive surgery, LLNL AO Phoropter Retinal Imaging with Adaptive OpticsHighlighted results from Rochester, Houston, Indiana, UCD etc.1.3 Future Potential of AO in Vision Science1.3.1 Post-processing and AO1.3.2 AO and other imaging technologies (e.g. OCT)1.3.3 Vision Correction1.3.4 Retinal Imaging1.3.5 Retinal SurgeryII. Wavefront Sensing2. Aberration Structure of the Human Eye (Pablo Artal)(Murcia Optics Lab; LOUM)2.1 Aberration structure of the human eye2.1.1 Monochromatic aberrations in normal eyes2.1.2 Chromatic aberrations2.1.3 Location of aberrations2.1.4 Dynamics (temporal properties) of aberrations2.1.5 Statistics of aberrations in normal populations (A Fried parameter?)2.1.6 Off-axis aberrations2.1.7 Effects of polarization and scattering3. Wavefront Sensing and Diagnostic Uses (Geunyoung Yoon) University of Rochester3.1 Introduction3.1.1 Why is wavefront sensing technique important for vision science?3.1.2 Importance of measuring higher order aberrations of the eyeCharacterization of optical quality of the eyePrediction of retinal image quality formed by the eye’s opticsBrief summary of potential applications of wavefront sensing technique3.1.3 Chapter overview3.2 Wavefront sensors for the eye3.2.1 History of ophthalmic wavefront sensing techniques3.2.2 Different types of wavefront sensors and principle of each wavefrontsensorSubjective vs objective method (SRR vs S-H, LRT and Tcherning)Measuring light going into vs coming out of the eye (SRR, LRT and Tcherning vs S-H) 3.3 Optimizing Shack-Hartmann wavefront sensor3.3.1 Design parametersWavelength, light source, laser beacon generation, pupil camera, laser safety…3.3.2 OSA standard (coordinates system, sign convention, order of Zernikepolynomials)3.3.3 Number of sampling points (lenslets) vs wavefront reconstructionperformance3.3.4 Tradeoff between dynamic range and measurement sensitivityFocal length of a lenslet array and lenslet spacing3.3.5 PrecompensationTrial lenses, trombone system, bite bar (Badal optometer)3.3.6 Increasing dynamic range without losing measurement sensitivityTranslational plate with subaperturesComputer algorithms (variable centroiding box position)3.3.7 Requirement of dynamic range of S-H wavefront sensor based on a largepopulation of the eye’s aberrations3.4 Calibration of the wavefront sensor3.4.1 reconstruction algorithm - use of simulated spot array pattern3.4.2 measurement performance - use of phase plate or deformable mirror 3.5 Applications of wavefront sensing technique to vision science3.5.1 Laser refractive surgery (conventional and customized ablation)3.5.2 Vision correction using customized optics (contact lenses andintraocular lenses)3.5.3 Autorefraction (image metric to predict subjective vision perception)3.5.4 Objective vision monitoring3.5.5 Adaptive optics (vision testing, high resolution retinal imaging)3.6 SummaryIII. Wavefront Correction with Adaptive Optics 4. Mirror Selection (Nathan Doble and Don Miller)University of Rochester / Indiana University4.1 Introduction4.1.1 Describe the DMs used in current systems.4.1.1.2 Xinetics type – Williams, Miller, Roorda – (PZT and PMN)4.1.1.3 Membrane – Artal, Zhu(Bartsch)4.1.1.4 MEMS – LLNL Phoropter, Doble4.1.1.5 LC-SLM – Davis System.4.2 Statistics of the two populations4.2.1 State of refraction:4.2.1.1 All aberrations present4.2.1.2 Zeroed Defocus4.2.1.3 Same as for 4.2.1.2 but with astigmatism zeroed in addition4.2.2 For various pupil sizes (7.5 - 2 mm) calculate:4.2.2.1 PV Error4.2.2.2 MTF4.2.2.3 Power Spectra4.2.3 Required DM stroke given by 95% of the PV error for the variousrefraction cases and pupil sizes.4.2.4 Plot of the variance with mode order and / or Zernike mode.4.3 Simulation of various Mirror TypesDetermine parameters for all mirrors to achieve 80% Strehl.4.3.1 Continuous Faceplate DMs4.3.1.1 Describe mode of operation.4.3.1.2 Modeled as a simple Gaussian4.3.1.3 Simulations for 7.5mm pupil4.3.1.4 Parameters to vary:Number of actuators.Coupling coefficient.Wavelength.4.3.1.5 All the above with unlimited stroke.4.3.2 Piston Only DMs4.3.2.1 Describe mode of operation.4.3.2.2 Simulations for 7.5mm pupil with either cases4.3.2.3 No phase wrapping i.e. unlimited stroke.Number of actuators.Packing geometryWavelength.Need to repeat the above but with gaps.4.3.2.4 Effect of phase wrappingTwo cases:Phase wrapping occurs at the segment locations.Arbitrary phase wrap.4.3.3 Segmented Piston / tip / tilt DMs4.3.3.1 Describe mode of operation.4.3.3.2 Three influence functions per segment, do the SVD fit on a segment by segmentbasis.4.3.3.3 Simulations for 7.5mm pupil.4.3.3.4 No phase wrapping unlimited stroke and tip/tilt.Number of actuators - squareSame as above except with hexagonal packing.Wavelength.Gaps for both square and hexagonal packing.4.3.3.5 Effect of phase wrappingPhase wrapping occurs at the segment locations.Arbitary phase wrap. Wrap the wavefront and then determine the required number ofsegments. Everything else as listed in part 1).4.3.4 Membrane DMs4.3.4.1 Describe mode of operation. Bimorphs as well.4.3.4.2 Simulations for 7.5mm pupil with either cases.4.3.4.3 Parameters to vary:Number of actuators.Actuator size.Membrane stressWavelength.5. Control Algorithms (Li Chen)University of Rochester5.1 Configuration of lenslets and actuators5.2 Influence function measurement5.3 Control command of wavefront corrector5.3.1 Wavefront control5.3.2 Direct slope control5.3.3 Special control for different wavefront correctors5.4 Transfer function modelization of adaptive optics system5.4.1 Transfer function of adaptive optics components5.4.2 Overall system transfer function5.4.3 Adaptive optics system bandwidth analysis5.5 Temporal modelization with Transfer function5.5.1 Feedback control5.5.2 Proportional integral control5.5.3 Smith compensate control5.6 Temporal controller optimization5.6.1 Open-loop control5.6.2 Closed-loop control5.6.2 Time delay effect on the adaptive optics system5.6.3 Real time considerations5.7 Summary6. Software/User Interface/Operational Requirements (Ben Singer) University of Rochester6.1 Introduction6.2 Hardware setup6.2.1 Imaging6.2.1.1 Hartmann-Shack Spots6.2.1.2 Pupil Monitoring6.2.1.3 Retinal Imaging6.2.2 Triggered devices: Shutters, lasers, LEDs6.2.3 Serial devices: Defocusing slide, custom devices6.2.4 AO Mirror control6.3 Image processing setup6.3.1 Setting regions of interest: search boxes6.3.2 Preparing the image6.3.2.1 Thresholding6.3.2.2 Averaging6.3.2.3 Background subtraction6.3.2.4 Flat-fielding6.3.3 Centroiding6.3.4 Bad data6.4 Wavefront reconstruction and visualization6.4.1 Zernike mode recovery and RMS6.4.1.1 Display of modes and RMS: traces, histograms6.4.1.2 Setting modes of interest6.4.2 Wavefront visualization6.4.2.1 Continuous grayscale image6.4.2.2 Wrapped grayscale image6.4.2.3 Three-D plots6.5 Adaptive optics6.5.1 Visualizing and protecting write-only mirrors6.5.2 Testing, diagnosing, calibrating6.5.3 Individual actuator control6.5.4 Update timing6.5.5 Bad actuators6.6 Lessons learned, future goals6.6.1 Case studies from existing systems at CVS and B&L6.6.1.1 One-shot wavefront sensing vs realtime AO6.6.1.2 Using AO systems in experiments: Step Defocus6.6.2 Engineering trade-offs6.6.2.1 Transparency vs Simplicity6.6.2.2 Extensibility vs Stability6.6.3 How to please everyone6.6.3.1 Subject6.6.3.2 Operator6.6.3.3 Experimenter6.6.3.4 Programmer6.6.4 Software tools6.7 Summary7. AO Assembly, Integration and Troubleshooting (Brian Bauman) Lawrence Livermore7.1 Introduction and Philosophy7.2 Optical alignment7.2.1 General remarks7.2.2 Understanding the penalties for misalignments7.2.3 Having the right knobs: optomechanics7.2.4 Common alignment practices7.2.4.1 Tools7.2.4.2 Off-line alignment of sub-systems7.2.4.3 Aligning optical components7.2.4.4 Sample procedures (taken from the AO phoropter project)7.3 Wavefront sensor checkout7.3.1 Wavefront sensor camera checkout7.3.2 Wavefront sensor checkout7.3.2.1 Proving that centroid measurements are repeatable.7.3.2.2 Proving that the centroid measurements do not depend on where centroids are withrespect to pixels7.3.2.3 Measuring plate scale.7.3.2.4 Proving that a known change in the wavefront produces the correct change incentroids.7.4 Wavefront Reconstruction7.4.1 Testing the reconstruction code: Prove that a known change in thewavefront produces the correct change in reconstructed wavefront.7.5 Aligning the “probe” beam into the eye7.6 Visual stimulus alignment7.7 Flood-illumination alignment7.8 DM-to-WFS Registration7.8.1 Tolerances & penalties for misregistration7.8.2 Proving that the wavefront sensor-to-SLM registration is acceptable.7.9 Generating control matrices7.9.1 System (“push”) matrix7.9.2 Obtaining the control matrix7.9.3 Checking the control matrix7.9.4 Null spaces7.10 Closing the loop7.10.1 Checking the gain parameter7.10.2 Checking the integration parameter7.11 Calibration7.11.1 Obtaining calibrated reference centroids.7.11.2 Proving that reference centroids are good7.11.3 Image-sharpening to improve Strehl performance.7.12 Science procedures7.13 Trouble-shooting algorithms8. System Performance: Testing, Procedures, Calibration and Diagnostics (Bruce Macintosh, Marcos Van Dam)Lawrence Livermore / Keck Telescope8.1 Spatial and Temporal characteristics of correction8.2 Power Spectra calculations8.3 Disturbance rejection curves8.4 Strehl ratio/PSF measurements/calculations8.5 Performance vs. different parameters (beacon brightness, field angle, …)?8.6 Summary Table and Figures of above criteria8.6.1 Results from Xinetics, BMC, IrisAOIV. Retinal Imaging Applications 9. Fundamental Properties of the Retina (Ann Elsner) Schepens Eye Research Institute9.1 Shape of the retina, geometric optics9.1.1 Normal fovea, young vs. old9.1.1.1. foveal pit9.1.1.2. foveal crest9.1.2 Normal optic nerve head9.1.3 Periphery and ora serrata9.2 Two blood supplies, young vs. old9.2.1 Retinal vessels and arcades9.2.2 0 – 4 layers retinal capillaries, foveal avascular zone9.2.3 Choriocapillaris, choroidal vessels, watershed zone 9.3 Layers vs. features, young vs. old, ethnic differences9.3.1 Schlera9.3.2 Choroidal vessels, choroidal melanin9.3.3 Bruch’s membrane9.3.4 RPE, tight junctions, RPE melanin9.3.5 Photoreceptors, outer limiting membrane9.3.5.1 Outer segment9.3.5.2 Inner segment9.3.5.3 Stiles-Crawford effect9.3.5.4 Macular pigment9.3.6 Neural retina9.3.7 Glia, inner limiting membrane, matrix9.3.8 Inner limiting membrane9.3.9 Vitreo-retinal interface, vitreous floaters9.4 Spectra, layers and features9.4.1 Main absorbers in the retina9.4.2 Absorbers vs. layers9.4.3 Features in different wavelengths9.4.4 Changes with aging9.5 Light scattering, layers and features9.5.1 Directly backscattered light9.5.2 Multiply scattered light9.5.3 Geometric changes in specular light return9.5.4 Layers for specular and multiply scattered light9.5.5 Imaging techniques to benefit from light scattering properties 9.6 Polarization9.6.1 Polarization properties of the photoreceptors9.6.2 Polarization properties of the nerve fiber bundles, microtubules9.6.3 Anterior segment and other polarization artifacts9.6.4 Techniques to measure polarization properties9.7 Imaging techniques to produce contrast from specular or multiply scattered light9.7.1 Confocal imaging9.7.2 Polarization to narrow the point spread function9.7.3 Polarization as a means to separate directly backscattered light frommultiply scattered light, demonstration using the scattered light9.7.4 Coherence techniques as a means to separate directly backscattered light from multiply scattered light, with a goal of using the scattered light10. Strategies for High Resolution Retinal Imaging (Austin Roorda, Remy Tumbar, Julian Christou)University of Houston / University of Rochester / University of California, Santa Cruz10.1 Conventional Imaging (Roorda)10.1.1 Basic principlesThis will be a simple optical imaging system10.1.2 Basic system designShow a typical AO flood-illuminated imaging system for the eye10.1.3 Choice of optical componentsDiscuss the type of optical you would use (eg off axis parabolas)10.1.4 Choice of light sourceHow much energy, what bandwidth, flash duration, show typical examples10.1.5 Controlling the field sizeWhere to place a field stop and why10.1.6 Choice of cameraWhat grade of camera is required? Show properties of typical cameras that are currently used10.1.7 Implementation of wavefront sensingWhere do you place the wavefront sensor. Using different wavelengths for wfs.10.2 Scanning Laser Imaging (Roorda)10.2.1 Basic principlesThis will show how a simple scanning imaging system operates10.2.2 Basic system designThis shows the layout of a simple AOSLO10.2.3 Choice of optical componentsWhat type of optical components shoud you use and why (eg mirrors vs lenses). Where doyou want to place the components (eg raster scanning, DM etc) and why.10.2.4 Choice of light sourceHow to implement different wavelengths. How to control retinal light exposure10.2.5 Controlling the field sizeOptical methods to increase field sizeMechanical (scanning mirror) methods to increase field size10.2.6 Controlling light deliveryAcousto-optical control of the light source for various applications10.2.7 Choice of detectorPMT vs APD what are the design considerations10.2.8 Choice of frame grabbing and image acquisition hardwareWhat are the requirements for a frame grabber. What problems can you expect.10.2.9 Implementation of wavefront sensingStrategies for wavefront sensing in an AOSLO10.2.10 Other: pupil tracking, retinal tracking, image warping10.3 OCT systems (Tumbar)10.3.1 Flood illuminated vs. Scanning10.4 Future ideas (Tumbar)10.4.1 DIC (Differential Interference Contrast)10.4.2 Phase Contrast10.4.3 Polarization Techniques10.4.4 Two-photon10.4.5 Fluorescence/Auto-fluorescence10.5 Survey of post-processing/image enhancement strategies (Christou)11. Design Examples11.1 Design of Houston Adaptive Optics Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscope (AOSLO) (Krishna Venkateswaran)11.1.1 Basic optical designEffect of double pass system on psf, imaging in conjugate planes11.1.2 Light delivery opticsFiber optic source and other optics11.1.3 Raster scanningScanning speeds etc.,11.1.4 Physics of confocal imaging11.1.5 Adaptive optics in SLOWavefront sensing, Zernike polynomials, Deformable mirror, correction time scales11.1.6 Detailed optical layout of the AOSLOLens, mirrors, beam splitters with specs11.1.7 Image acquisitionBack end electronics, frame grabber details11.1.8 Software interface for the AOSLOWavefront sensing, Image acquisition11.1.9 Theoretical model of AOSLO:Limits on axial and lateral resolution11.1.10 Image registration11.1.11 Results11.1.12 Discussions on improving performance of AOSLOLight loss in optics, Deformable mirror, Wavefront sensing,11.1.13 Next generation AOSLO type systems11.2 Indiana University AO Coherence Gated System (Don Miller)11.2.1 Resolution advantages of an AO-OCT retina camera11.2.2 AO-OCT basic system design concepts11.2.2.1 Application-specific constraints−Sensitivity to weak tissue reflections−Tolerance to eye motion artifacts−Yoking focal plane to the coherence gate11.2.2.2 Integration of AO and OCT sub-systems−Generic OCT system−Specific OCT architectures−Preferred AO-OCT embodiments11.2.3 Description of the Indiana AO-OCT retina cameraOptical layout of the Indiana AO-OCT retina camera11.2.3.1 Adaptive Optics for correction of ocular aberrationsA. System descriptionB. Results11.2.3.2 1D OCT axial scanning for retina trackingA. System descriptionB. Results11.2.3.3 High speed 2D incoherent flood illumination for focusing and aligningA. System descriptionB. Results11.2.3.4 CCD-based 2D OCT for en face optical sectioning the retinaA. System descriptionB. Results11.2.4 Future developments11.2.4.1 Smart photodiode array11.2.4.2 En face and tomographic scanning11.2.4.3 Reduction of image speckle11.2.4.4 Detector sensitivity11.2.4.5 Faster image acquisition11.3 Rochester Second Generation AO System (Heidi Hofer)V. Vision Correction Applications12. Customized Vision Correction Devices (Ian Cox)Bausch & Lomb12.1 Contact Lenses12.1.1 Rigid or Soft Lenses?12.1.2 Design Considerations – More Than Just Optics12.1.3 Measurement – The Eye, the Lens or the System?12.1.4 Manufacturing Issues – Can The Correct Surfaces Be Made?12.1.5 Who Will Benefit?12.1.6 Summary12.2 Intraocular Lenses12.2.1 Which Aberrations - The Cornea, The Lens or The Eye?12.2.2 Surgical Procedures – Induced Aberrations12.2.3 Design & Manufacturing Considerations12.2.4 Future Developments & Summary13. Customized Refractive Surgery (Scott MacRae)University of Rochester / StrongVision14. Visual Psychophysics (UC Davis Team, headed by Jack Werner) UC Davis14.1 Characterizing visual performance14.1.1 Acuity14.1.2 Contrast sensitivity functions (CSFs)14.1.3 Photopic/scotopic performance (include various ways to defineluminance)14.2 What is psychophysics?14.2.1 Studying the limits of vision14.2.2 Differences between detection, discrimination and identification14.3 Psychophysical methods14.3.1 Psychometric function14.3.2 signal detection theory14.3.3 measuring threshold14.3.4 Criterion-free methods14.3.5 Method of constant stimuli, method of adjustment, adaptive methods(e.g. Quest).14.4 The visual stimulus14.4.1 Issues in selecting a display systemTemporal resolutionSpatial resolutionIntensity (maximum, bit depth)HomogeneitySpectral characteristics14.4.2 Hardware optionsCustom optical systems (LEDs, Maxwellian view)DisplaysCRTsDLPsLCDsPlasmaProjectorsDisplay generationcustom cardsVSGBits++10-bit cardsPelli attenuatorDithering/bit stealing14.4.3 SoftwareOff the shelf software is not usually flexible enough. We recommend doing it yourself. This canbe done using entirely custom software (e.g. C++) or by using software libraries such as VSG(PC) or PsychToolbox (Mac/PC).14.4.4 CalibrationGamma correctionSpatial homogeneityTemporal and spatial resolution14.5 Summary15. Wavefront to Phoropter Refraction (Larry Thibos)Indiana University15.1 Basic terminology15.1.1 Refractive error15.1.2 Refractive correction15.1.3 Lens prescriptions15.2 The goal of subjective refraction15.2.1 Definition of far point15.2.2 Elimination of astigmatism15.2.3 Using depth-of-focus to expand the range of clear vision15.2.4 Placement of far-point at hyperfocal distance15.3 Methods for estimating the monochromatic far-point from an aberration map15.3.1 Estimating center of curvature of an aberrated wavefront15.3.1.1 Least-squares fitting15.3.1.2 Paraxial curvature matching15.3.2 Estimating object distance that optimizes focus15.3.2.1 Metrics based on point objects15.3.2.2 Metrics based on grating objects15.4 Ocular chromatic aberration and the polychromatic far-point15.4.1 Polychromatic center of curvature metrics15.4.2 Polychromatic point image metrics15.4.3 Polychromatic grating image metrics15.5 Experimental evaluation of proposed methods15.5.1 Conditions for subjective refraction15.5.2. Monochromatic predictions15.5.3 Polychromatic predictions16. Design ExamplesDetailed Layouts, Numbers, Noise Analysis, Limitations for Visual Psychophysics: 16.1 LLNL/UR/B&L AO Phoroptor (Scot Olivier)16.2 UC Davis AO Phoropter (Scot Olivier)16.3 Rochester 2nd Generation AO System (Heidi Hofer)V. Appendix/Glossary of Terms (Hope Queener, JosephCarroll)• Laser safety calculations• Other ideas?• Glossary to define frequently used terms。

英文回答:Paramolecular laser optical correction is an important treatment for eye vision correction using advanced laser technology. This technology, which is applied primarily to the treatment of ills such as near—sightedness, distant vision and light, is an important part of the development of our health care. Key technologies include the precise positioning and operation of laser systems, the precision of corneal cutting techniques, and the impact of laser therapy on eye tissue. In using this technology, laser systems must be strictly required to be capable of precisely locking the eyeball of the patient and adjusting the angle and strength of the laser beam to ensure the accuracy and safety of the treatment. Angular cutting techniques are also essential, and there is a need to ensure that the patient ' s corneals are properly circumcised during surgery and that the depth and shape of the cutting meets the treatment requirements. The impact of laser therapy on eye tissue also needs to be accurately assessed to ensure recovery and effectiveness after surgery, reflecting a people—centred approach to development.准分子激光视觉光学矫正是一项利用先进激光技术对眼睛视觉问题进行矫正的重要治疗手段。