Nickel Alloy Development and Use in USC Boilers

John deBarbadillo1, Brian Baker1, Leon Klingensmith2, Lesh Patel1

1Special Metals Corporation, 3200 Riverside Drive, Huntington WV, 25705, jdebarba@https://www.doczj.com/doc/5f2624506.html,, bbaker@https://www.doczj.com/doc/5f2624506.html,, spatel@https://www.doczj.com/doc/5f2624506.html,

2 Wyman-Gordon Pipe and Fittings, 10825 Telge Road, Houston TX, 77240,

klink@https://www.doczj.com/doc/5f2624506.html,

Abstract

Solid solution strengthened stainless steels and nickel-base alloys have been employed successfully worldwide for many years as tube, pipe and weld overlay in fossil fuel fired steam boilers. Over the past decade the need for improved boiler efficiency to reduce CO2 emissions has led to the design of ultra-supercritical (USC) steam boiler systems with operating temperatures and pressures that require much stronger and more corrosion resistant materials. INCONEL? alloys 617 and 740 have emerged as leading candidates for tube, pipe and other components. Alloy 617 is a carbon and molybdenum strengthened nickel-base alloy that has been used for over twenty years in industrial gas turbines. Alloy 740 is a new precipitation hardened nickel-base alloy, based on an aircraft gas turbine alloy NIMONIC? alloy 263, that was modified for increased strength and hot corrosion resistance.

This paper briefly reviews the history of the development of these alloys and the properties that make them candidates for USC service. The paper then describes the recent manufacturing of boiler tube and header pipe for qualification programs in Europe. Most recently a 378mm OD x 88mm AWT x 8.9m long alloy 617 pipe was extruded at Wyman-Gordon Pipe and Fittings Co. in Houston, TX. Properties and microstructure of this extrusion will be presented. The alloy 740 composition was originally formulated for relatively thin wall boiler tube operating to a maximum service temperature of 700°C. The alloy has also been under consideration for much larger components such as the boiler header and re-heater pipe, and various components in the steam turbine. Extensive microstructure analyses of long time exposed material and heavy section welding tests have been performed. These tests revealed the need to slightly modify the alloy chemistry to improve phase stability and to prevent weld micro-fissures. These data will be presented and discussed. The final section of the paper will comment on some of the challenges that remain for producing large section superalloy steam boiler components.

? INCONEL and NIMONIC are Trademarks of Special Metals Corporation.

Keywords: Nickel-base alloys; Stress-rupture; Extrusion; Tube and Pipe; Large Ingots

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, the quest for a more fuel-efficient and lower CO2 emission coal fired boiler, has resulted in considerable advances in the understanding of materials requirements and capabilities. Currently the most efficient commercial supercritical- steam designs operating in the temperature range of 600°C and steam pressures of 20-35MPa utilize super-ferritic steels such as P92. Higher efficiency systems operating at steam temperatures of 700°C and above and pressures of 35MPa referred to in this paper as ultra-supercritical (USC) plants will require adoption of much stronger and more expensive nickel-base alloys for tube, pipe and forged and cast components in the boiler and steam turbine. Collaborative projects in Europe, Japan and the United States have explored the capabilities of a wide range of nickel-base alloys and excellent reviews have been published [1,2]. Two alloys have emerged as leading candidates for this application. One is a

restricted-chemistry version of the carbon and molybdenum strengthened alloy 617 that is widely referred to as CCA 617. The concept originated in Europe and the alloy has been extensively characterized in a program based at the Oak Ridge National Lab in the USA [3]. The second alloy is an age-hardened alloy called INCONEL alloy 740 which was developed by Special Metals and characterized extensively in the European THERMIE AD700 program [4]. The nominal compositions of the two alloys and their variants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Nominal Composition of Alloys 617 and 740, weight percent.

ALLOY C CR MO CO AL TI NB MN FE SI

617 0.08 22 9 12.5 1 0.3 - 0.1 0.5 0.1

22 9 12 1 0.4 - 0.1 0.5 0.1

0.06

CCA617

740 0.03 25 0.5 20 0.9 1.8 2 0.3 0.7 0.5 740H 0.03 25 0.5 20 1.35 1.35 1.5 0.3 0.7 0.15

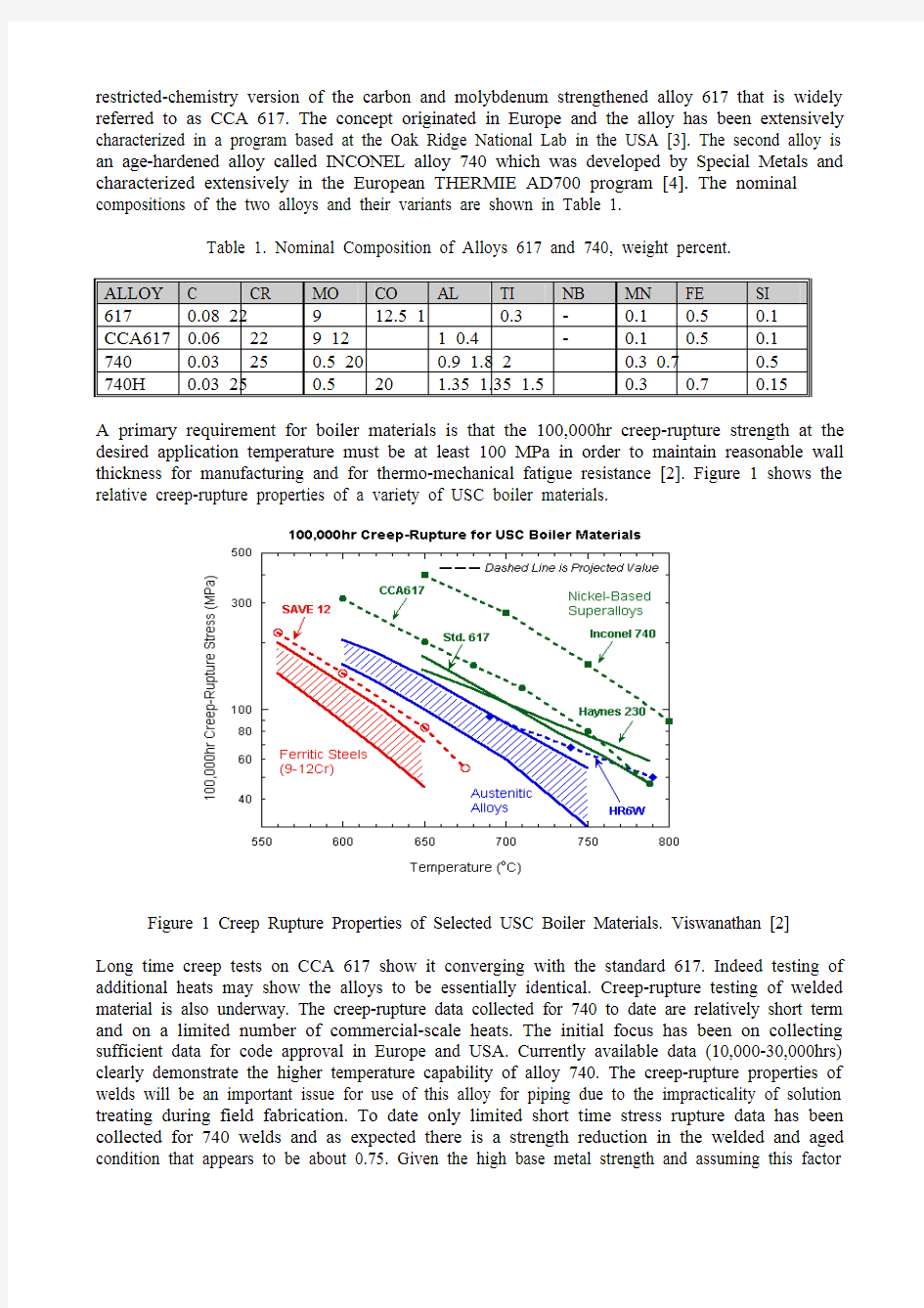

A primary requirement for boiler materials is that the 100,000hr creep-rupture strength at the desired application temperature must be at least 100 MPa in order to maintain reasonable wall thickness for manufacturing and for thermo-mechanical fatigue resistance [2]. Figure 1 shows the relative creep-rupture properties of a variety of USC boiler materials.

Figure 1 Creep Rupture Properties of Selected USC Boiler Materials. Viswanathan [2]

Long time creep tests on CCA 617 show it converging with the standard 617. Indeed testing of additional heats may show the alloys to be essentially identical. Creep-rupture testing of welded material is also underway. The creep-rupture data collected for 740 to date are relatively short term and on a limited number of commercial-scale heats. The initial focus has been on collecting sufficient data for code approval in Europe and USA. Currently available data (10,000-30,000hrs) clearly demonstrate the higher temperature capability of alloy 740. The creep-rupture properties of welds will be an important issue for use of this alloy for piping due to the impracticality of solution treating during field fabrication. To date only limited short time stress rupture data has been collected for 740 welds and as expected there is a strength reduction in the welded and aged condition that appears to be about 0.75. Given the high base metal strength and assuming this factor

does not further diminish in long time exposure, 740 still appears to be able to meet the target for the USA USC design.

The second important criterion is corrosion attack in steam and, in the case of boiler tubing, combustion gases. Both alloys with their high chromium content would be expected to perform well in steam environments and oxidation is not expected to be a limiting factor as shown in Figure 2 [5].

Fig. 2. Steam Corrosion for Alloys vs Chromium Content. 1000hrs at 650°C and 1000°C. Sarver [5]

Fig. 3. Performance of Various Nickel-Base Alloys in Simulated Coal Ash. Depth of attack after exposure at 700°C in N2-15% CO2 – 3.5% O2 – 0.25% SO2 with salt consisting of 5% Na2SO4 – 5% K2SO4 – 90% (Fe2O3-Al2O3-SiO2) recoated at intervals shown. Baker and Smith [8]

Fireside corrosion or coal ash corrosion is a much more complex subject as coal chemistry (particularly sulfur and chloride content) may have a profound effect. As a consequence no single set of test method or environment accurately describe relative material performance [6]. In general alloy 617 does not perform particularly well due to its high molybdenum content and may require a coating in many applications [7]. Alloy 740 has performed well in actual and simulated environment exposure. Figure 3 shows selected exposure data from Baker and Smith et al in laboratory simulation of a US Midwestern coal environment. A simulated coal ash deposit was applied periodically during the test period. Much more extensive evaluation in subscale test components is underway at the COMTES 700 program in Germany.

Boiler Tube

The initial USC nickel-base alloy boiler development effort has been focused on tube. Alloys 617 and 740 are both amenable to tube manufacture, but they are considered “hard alloys” having restricted capacity for cold reduction and therefore require multiple cold work and anneal cycles. To date all of the tube production for the USC application has been at the Special Metals facility in Hereford UK. The technology will be readily transferrable to the Special Metals facility in Huntington, WV in the USA that has comparable facilities. The manufacturing method used for both alloys involves Vacuum Induction Melting (VIM) followed by Electroslag Remelting (ESR) to 500mm diameter ingot and forging to a nominal 300mm bar. This forged bar is peeled, cut, bored, faced and radiused. The billet is extruded at 1180C to 130mm OD x 12.5mm wall tube shell that is then deglassed, annealed and pickled. The subsequent cold working process may be quite complex depending on the specific tube diameter and wall. It may consist of multiple cold pilger or cold draw, anneal and pickle steps until the final dimensions are obtained. The final heat treatment is a full solution anneal at 1150°C, water quench and age 16hrs at 800°C. Dimensions of tube made to date include a range of sizes from 21.3mm x 2.7mm AW to 50mm x 10mm AW. Length is typically 4m to 5m.

Fig 4. Room and high temperature tensile data for alloy 740. Tube specimens. Mechanical property testing is being undertaken to gain TüV code approval. Tensile data on tube samples from four commercial heats that were tested over the range from 20°C to 750°C are shown in Figure 4. These results compare quite well with the initial data determined on bar and plate.

More than 100 impact tests have been performed using half-size samples. As-annealed material has a range of 78-104J with an average of 88.7J. Annealed and aged material range is 42-52J with an average of 45.4J. Initial stress rupture data from two production heats are plotted on a Larson-Miller plot (Fig 5) along with the preliminary data summary curve from the US Supercritical Consortium [2]. Again the tube results compare quite favorably with the summary curve that inclues tests from a variety of product forms.

Fig 5. Creep-rupture properties of alloy 740 tube compared with the composite data. Header Pipe – Alloy 617

The initial characterization of alloy 617 for USC was done on relatively small-section plate and thin-wall tube. The primary application of alloy 617 since its development has been for aircraft and industrial gas turbine casings, combustors and exhaust gas ducts. Alloy 617 has been identified as a candidate for a number of much more massive components in USC boilers and turbines including boiler header, re-heater and super-heater pipe, steam turbine casings, valve bodies and rotors. These components may weigh 5,000kg to 25,000kg or more. Manufacturing of large size nickel-base superalloy ingots is of relatively recent origin. Alloy 625 ingots weighing up to 10,000kg have been produced for chemical and nuclear forged components and alloys 706 and more recently 718 are used in large frame turbine rotors and in forging dies. Manufacturing experience has shown that very stringent composition, remelting, forging and thermal treatment controls are needed to prevent thermal stress cracking and to generate a uniform microstructure [9-11]. Experience with large 617 ingots is much more limited. A recent report [12] describes initial casting and forging trials with large 617 ingots. These parts were successfully made from upset and bored ingots. No information has been published about the microstructure of these forgings.

The header pipe for steam boilers is too long to make from a single extruded piece. Typically this pipe is constructed from several extruded, heat treated and girth-welded pipe segments. Pipe diameters for current USC boilers are P92 advanced 9% chromium steel and may be more than a meter in diameter. Depending on the diameter, wall thicknesses of 125 mm are achievable. Wyman-Gordon Pipe and Fittings Co. has the capability of making pipes up to 20m long. Alloy 617 has a significantly higher flow stress than P92 at their respective metal working temperatures. It was expected at the outset of this project that maximum alloy 617 pipe dimensions would be limited by extrusion force limits rather than press geometry

To explore the extrusion option, Wyman-Gordon and Special Metals in collaboration with their European customer have made two trial alloy 617 pipe extrusions. The purpose of this work was to establish manufacturing feasibility, if possible to determine the pipe size limits for the alloy and to generate properties for code approval. Two 675mm diameter, 11,200kg electrodes were Vacuum Induction Melted (VIM) at the Special Metals facility in Huntington WV to the CCA 617 chemistry limits. These electrodes were Vacuum Arc Remelted (VAR) to 750mm diameter ingot, homogenized, cropped and conditioned before shipment to Wyman-Gordon. Remelting was quite stable and no evidence of center or channel segregation was observed on ingot head and toe macro-etch slices. No center segregation was detected by assays taken on ingot cross section.

The Wyman-Gordon extrusion process is a two-step operation involving a block and pierce on a 14kt press and back extrusion on a 35kt press. Figure 6 shows the two adjacent presses in action.

Fig. 6. 14KT Blocking Press and 35KT Extrusion Press. Material shown is not alloy 617.

First the ingot was pierced and expanded. The hollow was then machined and radiused and finally extruded to pipe. Extrusion conditions were based on hot compression tests and laboratory scale extrusions. The first sighting shot extrusion was from a 4,635Kg billet extruded at 1177°C. This extrusion pushed uneventfully although a patch of small OD cracks was present near the nose end of the pipe. The approximate dimensions of the as extruded pipe are 378mm OD x 88mm AWT x 6.7m. This pipe is shown on the cooling table in Figure 7a. The second extrusion was made from a conditioned ingot weighing 6805Kg. Due to the high loads on the first push some extrusion parameters were adjusted and the soaking temperature was raised to 1190°C. Nevertheless this run required the full capacity of the press. The final dimensions were 378mm OD x 88mm AWT x 8.9m. The second pipe is shown in Figure 7b.

After extrusion and straightening the pipes were production annealed at 1177°C and water quenched. An extensive non-destructive and mechanical property evaluation is now underway. Tensile and toughness data taken from the mid-wall of the pipes are shown in Table 2. These properties meet or exceed the customer specifications. It is particularly gratifying that the transverse through wall properties also exceed expectations. Knoop hardness traverses across the wall show no hardness trend.

Fig. 7a. First Extrusion Fig. 7b Second Extrusion Table 2. Tensile and Toughness Data for Production Annealed Pipe

Specimen

Location Orientation Tube Temp

°C

YS

MPa

UTS

MPa%EL%RA

Min

CVN, J

Avg

CVN, J

Spec L 20 241 655 35 74 100

H T 1

20

317

710

64

53

T T 1

20

324

724

56

50

H T 2

20

331

745

58

53

386

394 T T 2

20

317

703

64

57

377

384 Spec L 186

H L 1

650

197

511

77

60

T L 1

650

198

511

76

59

H L 2

650

221

536

86

60

T L 2

650

194

497

87

62

Representative 100X photomicrographs are shown in Fig 8. Average grain size was ASTM 1.5 on the nose and 2.5 on the tail with isolated grains as large as ASTM 0. Very light carbide banding is visible. This level of banding is considered acceptable based on the customer’s visual standards. Additional mechanical property results including short term creep and stress rupture data will be reported in the future. An extensive full wall welding evaluation will also be conducted.

Fig. 8a Head End of Extrusion Fig. 8b Tail End of Extrusion

Header Pipe – Alloy 740

All of the early characterization of alloy 740 was on relatively thin wall boiler tube for service where the maximum steam temperature would not exceed 700°C. It became clear that some adjustments of the original chemistry would be needed for alloy 740 to meet requirements for the heavier section components envisioned for service to 750°C in the US USC program. There were two primary considerations, thermal stability of the age hardening system leading to possible loss of strength and ductility and heat-affected zone micro-fissures in constrained welds.

Xie, Zhao and Dong working with the Special Metals development team performed an extensive metallographic analysis of alloy 740 aged for up to 5000hrs at temperatures between 704°C and 850°C [13]. This work revealed that during exposure at 725°C and above, acicular η phase particles nucleated at the grain boundaries and grew into the grains while consuming γ’. They established a TTT curve for this reaction. Xie also documented the coarsening rate of γ’ and the formation of the silicon containing G-phase. The effect of these long time microstructure changes on mechanical property behavior is uncertain; however, an exploration of composition adjustments within the broad alloy 740 composition range was undertaken. The specific adjustments that were explored were to increase aluminum-titanium ratio slightly to improve the stability of γ’, decrease titanium to retard formation of η and restrict silicon to discourage G-phase. Experimental lab heats demonstrated that these ideas did provide the desired microstructure stability [13].

Heat affected zone micro-fissures are a commonly encountered problem in restrained welds of superalloys that typically have a wide freezing range. Fissures were not encountered in the early work involving tube to tube welds with wall thickness less than 10mm. But exploratory work by Baker, Ramirez and Sanders showed that this was likely to be a problem in the heavier section circumferential butt welds required for the header pipe [14]. Subsequently Babcock and Wilcox Co and Special Metals undertook an in depth investigation of the factors that should be controlled to suppress micro-fissures in thick section welds. The results of this investigation are described in a recent paper by Sanders [15]. A typical HAZ micro-fissure in a 76mm joint made by hot-wire GTAW in a 740 plate of the original composition using matching composition filler wire is shown in Fig 10a. The approach taken to eliminate these micro-fissures was to adjust the composition to reduce the freezing range. All of the alloy constituents of alloy 740 widen the freezing range and some constraints existed. Aluminum and titanium were fixed at levels identified in the earlier work to maintain stability and gamma prime volume fraction. The effect of the elements niobium, silicon and boron on the freezing range was explored using the JMatPro modeling software. Based on the predicted relationships, a series of experimental compositions were made as 300lb VIM/VAR heats and converted to plate and welding wire. The freezing range was verified using differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and Gleeble testing.

All welding was done on annealed and aged plate of various thicknesses using GTAW and pulsed GMAW welding processes. Sanders et al report in detail on the results of the various welding trials on the optimum composition [15]. The most significant test for verifying 740 heavy section capability was an automatic hot-wire GTAW joint made on 76mm plate. Polished and etched cross-sections of joints made of the original and modified composition are shown in Fig 9a-b. Multiple cross sections of the weld in the modified composition were examined and were found to be free of any fissures in the base metal and the weld metal. All of the four bend tests, performed using a 2.5T radius, passed with no cracking whereas bends of welds in the original composition all cracked. Tensile properties at room temperature matched base plate properties.

Fig 9a Weld in original Composition Fig. 9b Weld in modified Composition

Fig 10a HAZ Micro-fissures Fig 10a Fissure-free HAZ

Combining the microstructure and welding work, a new target composition range has been defined as alloy 740H for use in heavy-section boiler and turbine applications. This range is compared with the tube chemistry in Table 1. Considerable work remains to verify the capabilities of this modified composition. Hot tensile and short time stress rupture tests at Special Metals and toughness of exposed material have matched properties for the tubing chemistry. This data is shown in Figure 11. Long time creep and stress rupture testing is underway at Oak Ridge National Lab on base plate material and is planned on weld material. To this point all work with the heavy section chemistry has been done on 300lb lab VIM/VAR heats. The next step would be to make a full-scale commercial heat and convert it to a component. One possibility being considered is to make an extruded header pipe similar to the alloy 617 pipe described previously.

Challenges for Nickel Alloy Use in USC Boilers

Significant progress has been made over the past decade to identify and characterize nickel-base alloys for USC application. Materials have been identified that, based on medium-term testing, appear to satisfy the design targets. Testing of production tubing of alloy 617 and alloy 740 continues to match expectations from laboratory work. Thick section pipe components have been successfully made from alloy 617 and testing is underway. A chemistry modification has been made to alloy 740 that has alleviated the problem of weld micro-fissures and improved microstructure stability and creep-rupture life in the 700°C to 750°C range. However, challenges remain before these alloys will be considered viable for boiler and turbine use. Process simulation will become an important tool in addressing these issues, but full-scale fabrication trials and prototype component testing will be needed. This type of component verification is time consuming and expensive and

unfortunately often production equipment specific. The following are some of the remaining issues to be addressed.

Fig 11. Creep-rupture tests of various USC materials showing recent results for the modified alloy

740 composition.

Work in Europe and the US has begun to stretch the manufacturing size boundaries for 617, but even larger components will be needed for the full-scale plant. As a consequence of its high molybdenum content, alloy 617 has very high hot forming loads. The pipe extrusion at Wyman-Gordon effectively defined the range of pipe sizes possible for this alloy. The actual dimensions will be defined by the specific combination of pipe OD and wall, with about 684mm OD x 50mm wall being the largest size possible. Larger cross section pipe would have to be made by other methods, for example bored, forged billet or seam-welded plate. Both approaches have the disadvantage of much more welding and would need to be proven.

Another issue for alloy 617 is microstructure uniformity. Carbide banding that may occur in this alloy is associated with directionality of properties, variable impact toughness, laminar tearing of welds and fatigue resistance. The microstructure standards used to date are adopted from plate products and may not be relevant or even achievable in large forged components. Furthermore, it is well known that the tendency for segregation defects increases strongly with ingot size. The phenomenon of macro-segregation in nickel-base superalloys has received widespread attention [16], but no ideal method for predicting segregation tendency of an alloy exists. Recent studies that base predicted behavior on estimated density differences between the interdendritic and bulk liquid have shown considerable promise [17,18]. Both alloy 617 and 740 appear to be resistant to macro-segregation in comparison to alloys such as 230, 625 and 718 [19]. The good microstructure in our recently produced 30-inch VIM/VAR ingot is a milestone but it remains to be seen whether this can be produced in larger ingots or by alternative remelting methods.

Alloy 740 for heavy section use poses a different set of potential problems. The alloy appears to be less prone to melt segregation than alloy 617 and based on Gleeble tests has about 80% of the flow stress of 617 and hence able to be forged or extruded to larger size on existing equipment. Hot compression testing of alloys 617 and 740 now being conducted at Wyman-Gordon will quantify this effect. On the other hand alloy 740 is a γ’ age-hardened alloy with a relatively high hardener

content and therefore susceptible to thermal stress cracking during heating and cooling at various stages of the manufacturing operation, particularly during remelting. Large section components may exhibit auto-aging as a result of slow cooling at the center of the component. This will adversely affect strength because γ’ precipitates formed during auto-aging tend to be coarser than those formed during isothermal aging at the optimum aging temperature. Little is known at this point about alloy 740 behavior under these manufacturing conditions.

Finally, the issue of weld properties in large components made from age-hardened materials must be fully understood addressed. Short-term studies indicated the strength of the aged weld metal to be about 75% of the fully solution treated and aged weld. Structures too large to be assembled in the plant and will require field fabrication. Under these conditions full solution treatment is not possible and the optimum aging cycle of 16hrs may pose problems. Welding with a stronger alloy is being studied but no existing stronger alloy matches alloy 740 corrosion properties. At this point it is difficult to imagine how the full strength of an age- hardened alloy can be utilized without a matching strength weld.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ian Dempster, Tom Armstrong and Bill Wehrle who have made important contributions to the success of the alloy 617 pipe extrusion. Also John Sanders and John Siefert of Babcock & Wilcox and Ronnie Gollihue of Special Metals who have led the alloy 740 heavy section welding investigations.

References

1) R. Blum and R. W. Vanstone; Proceedings of the Sixth International Charles Parsons Turbine Conference, Institute of Materials, Minerals and Mining, London, 2003, pp 489-510.

2.) R. Viswanathan, J. P. Shingledecker, J. Hawk, and M. Santella; Proceedings of 34th International Technical Conference on Clean Coal and Fuel Systems, Coal Technology Association, Clearwater, FL, May 31 to June 4, 2009.

3) J. P. Shingledecker, R. W. Swindeman, Q. Wu and V. K. Vasudevan: Proceedings to the Fourth International Conference on Advances in Materials Technology for Fossil Power Plants, ASM-International, Materials Park Ohio, 2005.

4) B. A. Baker; Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivitives, TMS 2005, pp601-611

5) J. M. Sarver and J. Tanzosh; Advances in Materials Technology for Fossil Plants, ASM International, 2005.

6) M. S. Gagliano, H. Hack, and G. Stanko, G., Proceedings, The 2008 Clearwater Coal Conference, 33rd International Technical Conference on Coal Utilization and Fuel Systems, Clearwater, FL, USA, June 1-5, 2008.

7) R. Viswanathan, R. Purgert, P. Rawls; “Coal-Fired Power Materials,” Advanced Materials and Processes, September, 2008, pp 41-45.

8) B. A. Baker and G. D. Smith, Paper 04526, presented at the NACE Annual Conference 2004, New Orleans, LA, March 28-April 1, 2004.

9) S. V. Thamboo, R. C. Schwant, L. Yang, L. A. Jackman, B. J. Bond and R. L. Kennedy: Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivitives, TMS 2001, pp 57-70

10) A. D. Helms, C. B. Adasczik, L. A. Jackman; Superalloys 1996, TMS 1996, pp427-433.

11) R. S. Minisandram, L. A. Jackman, C. B. Adasczik and R. Shivpuri; Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivitives, TMS, 1997, pp 131-139.

12.) F. Hofmann, International Atomic Energy Agency website,

https://www.doczj.com/doc/5f2624506.html,/inisnkm/nkm/aws/htgr/fulltext/iwggcr9_36.pdf.

13.) X. Xie, S. Zhao, J. Dong, G. D.Smith, G. D, and S. J. Patel, Materials Science Forum, Vols. 475-479, 2005, pp 613-618.

14) J. M. Sanders, J Ramirez, and B. Baker, Proceedings of Fifth International Conference on Advances in Materials Technology for Fossil Power Plants, EPRI, DOE and OCDO, Marco Island, FL, October 3-5, 2007.

15.) J. M. Sanders, B. A. Baker, J. A. Siefert, R. D. Gollihue, Proceedings of 34th International Technical Conference on Clean Coal and Fuel Systems, Coal Technology Association, Clearwater, FL, May 31 to June 4, 2009.

16) S. T. Wlodek, and R. D. Field: Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivitives, TMS 1994, pp 167-175

17) W. Yang, W. Chen, K.-M. Chang, S. K. Mannan, J. J. deBarbadillo and K. Morita: Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivitives, TMS 2001, pp 113-122.

18) K. Morita, T. Suzuki, T. Taketsuru, D. G. Evans, and W. Yang; Superalloys 718, 625, 706 and Various Derivitives, TMS 2001, pp 149-160

19) T. Kajikawa, T. Sato, H. Yamada: Int. Symposium on Liquid Metal Processing and Casting, TMS 2009, pp 327-335.

爱惜粮食从我做起教学 反思 文档编制序号:[KKIDT-LLE0828-LLETD298-POI08]

《爱惜粮食从我做起》主题教育课反思 爱惜粮食是中华民族的传统美德。可如今生活水平提高了,学生将粮食视为取之不尽的,很难体会到粮食的来之不易,因此浪费粮食的现象无处不在。 在设计这节课时,我结合“光盘行动”和学生身边浪费粮食现象,做到遵循“回归生活,关注孩子的现实生活”的教学理念。在教学中通过认知、活动、辨理、讨论、等教学方法去感受、体会、领悟粮食来的真不容易,去爱惜粮食。本节课通过激趣导入、明理辨析、联系生活实际,指导行为、实践延伸这五个步骤分层逐步地实现教育目的。课后,我也认真地反思了自己在这节课的教学得失。首先,在这次的研讨课收获甚多。 一、课前准备充分,教学思路清晰 为了让学生了解粮食浪费现象,让粮食来之不易的观念直入学生心中,首先,我大量收集资料,聚焦浪费现象,来引发学生思考。其次,了解粮食是怎样诞生的,观看农民伯伯种水稻的过程,让学生感受粮食的来之不易。同时,让学生体验插秧苗,让孩子在模拟的劳动情境中体会劳动的辛苦,懂得粒粒皆辛苦的道理。再是,用真实的数据,震撼学生心灵;用触目惊心的画面,引发学生内心共鸣要爱惜粮食。最后是明理辨析、联系生活实际,指导行为、实践延伸。 二、紧跟时代,联系实际 从学生的生活实际出发,通过自身的浪费引发学生思考,让学生正视身边的浪费现象,进一步感受身边浪费粮食现象的普遍性和严重性。教育学生生活中做到珍惜粮食,不浪费粮食。 当然,在这节课里,还存在着许多不成熟的做法:

1.让学生体会中庄稼的辛苦时,让学生说出粮食生产的过程,只是思考过程并看图片,没有条件亲身体会,学生体会不了农民耕种的辛苦,这是一次失败的体验教学。 2.一些课件设计不够好。如:非洲饥饿儿童图片,震撼力不够,如果能配上音乐、讲述,效果可能会更好。但由于个人的信息技术尚还欠缺,很多添加音乐、配上语言的课件不会制作。再如:辨理的选材也是不够说服力。 通过这次主题班会尝试,我明白了品德与生活的教学就是要为孩子架起通向生活的桥梁,把学生与真实的社会生活紧密地联系起来,有意识的把学生带回到真实的生活中去,去观察、感受、体验、分析、反思他们的生活,并以其引导和提升自己的真实生活的重要性。

铝合金焊接技术 内容来源网络,由“深圳机械展(11万㎡,1100多家展商,超10万观众)”收集整理! 更多cnc加工中心、车铣磨钻床、线切割、数控刀具工具、工业机器人、非标自动化、数字化无人工厂、精密测量、3D打印、激光切割、钣金冲压折弯、精密零件加工等展示,就在深圳机械展. MIG、TIG能够得到良好的焊接接头,但是,这两种方法却有熔透能力差、焊接变形大、生 产效率低等缺点。近年来,很多科技工作者开始探讨铝合金焊接的新方法,如激光焊、双光 束激光焊、激光-电弧复合焊以及搅拌焊摩擦等,下面主要介绍这四种焊接方法的主要特点。 1、铝合金的激光焊 随着大功率、高性能激光加工设备的不断开发,铝合金激光焊接技术发展很快,与传统的 TIG、MIG焊相比,激光焊接铝合金具有以下优点; (1)能量密度高,热输入量小,焊接变形小,能得到熔化区和热影响区窄而熔深大的焊缝; (2)冷却速度快,能得到组织微细的焊缝,故焊接接头性能良好; (3)焊接速度快、功能多、适应性强、可靠性高,且不需要真空装置,所以在焊接精度、 效率、自动化等方面具有无可比拟的优势。 激光有很高的能量密度,焊接铝合金可以有效防止传统焊接工艺产生的缺陷,强度系数提高 很大。但激光器功率一般都比较小,对铝合金厚板的焊接困难,同时铝合金表面对激光束的 吸收率很低,要达到深熔焊时存在阀值问题,所以工艺上有一定难度。 2、铝合金的激光-电弧复合焊 虽然激光焊接铝合金有许多优势,但仍存在较大的局限性,如设备成本高、接头间隙允许度 小、工件准备工序严等。为了更有效地焊接铝合金,人们发展了激光-电弧复合焊工艺。激 光-电弧复合主要是激光与TIG电弧、MIG电弧及等离子体复合。铝合金激光-电弧复合焊

MONEL 400 /UNS N04400 The alloy has excellent corrosion resistance in hydrofluoric acid and fluorine gas, and is suitable for pipe fittings and valves etc for chemical industry, petroleum, atomic energy, marine development. 在氢氟酸和氟气中具有优异的耐蚀性,适用于化工、石油、原子能、海洋开发中用的管件、阀件等。 NICKEL 200 ( UNS N02200 / DIN. W.Nr. 2.4060 ) The alloy is from pure commercial (99.6%) nickel, has good mechanical properties and excellent corrosion resistance, high thermal conductivity, low gas content and low vapor pressure. Mainly used in food processing equipment, salt refining equipment, mining and ocean mining. High temperature above 300 DEG C for manufacturing industrial sodium hydroxide required equipment. 是纯商业性(99.6%)造成的镍,具有优良的力学性能和优良的耐腐蚀性,较高的热和电导率,低气体含量和低蒸汽压力。主要应用于食物加工处理设备、食盐提炼设备、采矿和海洋开采。在300℃以上的高温条件下制造工业氢氧化钠所需的设备。 NICKEL 201 ( UNS N02201 / DIN. W.Nr. 2.4060 ) The alloy is a commercially pure nickel with very low carbon content and has been approved for use in a high temperature environment of up to 1230 degrees Celsius. 是含碳量极低的纯商业性镍,已被批准用于服务高达1230℃的高温环境中。 INCONEL 600 ( GB NS312 / UNS N06600 / DIN W.Nr.2.4816 / DIN NiCrl 5Fe / BS NA14 / AFNOR NC23FeA ) The alloy has high corrosion resistance against various corrosive media, also has good anti creep rupture strength. Recommended for the above 700 C working environment, mainly used for corrosive alkali metal production and application, especially the use of sulfide in the environment. 对于各种腐蚀介质都具有耐蚀性,还具有很好的抗蠕变断裂强度。推荐用于700℃以上的工

常用金属焊接性之高温合金的钎焊 高温合金是在高温下具有较好的力学性能、抗氧化性和抗腐蚀性的合金。这类合金可分为镍基、铁基和钴基三类;在钎焊结构中用得最多的是镍基合金。镍基合金按强化方式分为固溶强化、实效沉淀强化和氧化物弥散强化三类。固溶强化镍基合金为面心立方点阵的固溶相,通过添加铬、钴、钨、钼、铝、钛、铌等元素提高原子间结合力,产生点阵畸变,降低堆垛层错能,阻止位错运动,提高再结晶温度来强化固溶体。沉淀强化镍基合金钢是在固溶强化的基础上添加较多的铝、钛、铌、钽等元素而形成的。这些元素除形成强化固溶体外,还与镍形成Ni3(Al、Ti)γ’或Ni3(NbAlTi)γ”金属间化合物相;同时钨、铜、硼等元素与碳形成各种碳化物。TD-Ni和TD-NiCr合金是在镍或镍铬基体中加入2%左右弥散分布的ThO2颗粒,产生弥散强化效果的新型高温合金。 一:钎焊性 高温合金均含有较多的铬,加热时表面形成稳定的Cr2O3,比较难以去除;此外镍基高温合金均含铝和钛,尤其是沉淀强化高温合金和铸造合金的铝和钛含量更高。铝和钛对氧的亲和力比铬大得多,加热时极易氧化。因此,如何防止或减少镍基高温合金加热时的氧化以及去除其氧化膜是镍基高温合金钎焊时的首要任务。镍基高温合金钎焊时不建议用钎剂来去除氧化物,尤其是在高的钎焊温度下,因为钎剂中的硼砂或硼酸在钎焊温度下与母材起反应,降低母材表面的熔化温度,促使钎剂覆盖处的母材产生溶蚀;并且硼砂或硼酸与母材发生反应后析出的硼可能渗入母材,造成晶间渗入。对薄的工件来说是很不利的。所以镍基高温合金一般都在保护气氛,尤其是在真空中钎焊。母材表面氧化物的形成和去除与保护气氛的纯度以及真空度密切相关。对于含铝和钛低的合金,热态真空度不应低于10-2Pa;对于含铝钛较高的合金,表面氧化物的去除不仅与真空度有关,而且还与加热温度有关。 无论是固溶强化,还是沉淀强化的镍基高温合金,都必须将其合金元素及其化合物充分固溶于基体内,才能取得良好的高温性能。沉淀强化合金固溶处理后还必须进行时效处理,已达到弥散强化的目的。因此钎焊热循环应尽可能与合金的热处理相匹配,即钎焊温度尽量与热处理的加热温度相一致,以保证合金元素的充分溶解。钎焊温度过低不能使合金元素完全溶解;钎焊温度过高将使母材的晶粒长大,这些均对母材

铝及铝合金的焊接特点 (1)铝在空气中及焊接时极易氧化,生成的氧化铝(Al2O3)熔点高、非常稳定,不易去除。阻碍母材的熔化和熔合,氧化膜的比重大,不易浮出表面,易生成夹渣、未熔合、未焊透等缺欠。铝材的表面氧化膜和吸附大量的水分,易使焊缝产生气孔。焊接前应采用化学或机械方法进行严格表面清理,清除其表面氧化膜。在焊接过程加强保护,防止其氧化。钨极氩弧焊时,选用交流电源,通过“阴极清理”作用,去除氧化膜。气焊时,采用去除氧化膜的焊剂。在厚板焊接时,可加大焊接热量,例如,氦弧热量大,利用氦气或氩氦混合气体保护,或者采用大规范的熔化极气体保护焊,在直流正接情况下,可不需要“阴极清理”。 (2)铝及铝合金的热导率和比热容均约为碳素钢和低合金钢的两倍多。铝的热导率则是奥氏体不锈钢的十几倍。在焊接过程中,大量的热量能被迅速传导到基体金属内部,因而焊接铝及铝合金时,能量除消耗于熔化金属熔池外,还要有更多的热量无谓消耗于金属其他部位,这种无用能量的消耗要比钢的焊接更为显着,为了获得高质量的焊接接头,应当尽量采用能量集中、功率大的能源,有时也可采用预热等工艺措施。 (3)铝及铝合金的线膨胀系数约为碳素钢和低合金钢的两倍。铝凝固时的体积收缩率较大,焊件的变形和应力较大,因此,需采取预防焊接变形的措施。铝焊接熔池凝固时容易产生缩孔、缩松、热裂纹

及较高的内应力。生产中可采用调整焊丝成分与焊接工艺的措施防止热裂纹的产生。在耐蚀性允许的情况下,可采用铝硅合金焊丝焊接除铝镁合金之外的铝合金。在铝硅合金中含硅%时热裂倾向较大,随着硅含量增加,合金结晶温度范围变小,流动性显0.5. 着提高,收缩率下降,热裂倾向也相应减小。根据生产经验,当含硅5%~6%时可不产生热裂,因而采用SAlSi条(硅含量4.5%~6%) 焊丝会有更好的抗裂性。 (4)铝对光、热的反射能力较强,固、液转态时,没有明显的色泽变化,焊接操作时判断难。高温铝强度很低,支撑熔池困难,容易焊穿。 (5)铝及铝合金在液态能溶解大量的氢,固态几乎不溶解氢。在焊接熔池凝固和快速冷却的过程中,氢来不及溢出,极易形成氢气孔。弧柱气氛中的水分、焊接材料及母材表面氧化膜吸附的水分,都是焊缝中氢气的重要来源。因此,对氢的来源要严格控制,以防止气孔的形成。 (6)合金元素易蒸发、烧损,使焊缝性能下降。 (7)母材基体金属如为变形强化或固溶时效强化时,焊接热会使热影响区的强度下降。 (8)铝为面心立方晶格,没有同素异构体,加热与冷却过程中没有相变,焊缝晶粒易粗大,不能通过相变来细化晶粒。 2. 焊接方法 几乎各种焊接方法都可以用于焊接铝及铝合金,但是铝及铝合金对

《燕子》课后随记 金土完小靳深 “一身乌黑光亮的羽毛,一对俊俏轻快的翅膀,加上剪刀似的尾巴,凑成了活泼机灵的小燕子。”──多么优美的文字,多么生动的描述,在我摇头晃脑地为学生朗读《燕子》一课时,却发现学生们并没有被我的激情、被书中的文字所感染。为什么呢?燕子可是学生们经常见到的,而文中又描写得这么形象、这么可爱,怎么会引不起学生的共鸣呢?就在我产生疑问时,我发现班里多半学生的目光都瞅向窗外。原来,窗外正有几只燕子在叽叽喳喳,我突然意识到,该让学生走进大自然,去把书中的语言文字和自己的观察体验相结合。让学生学会看风景、学会做文章。 “小燕子,穿花衣,年年春天来这里……”儿时的歌谣被孩子们快乐地哼唱着,在阳光下,在校园里,学生们尽情地寻找着燕子的足迹,品味着字里行间的描述和自己眼中看到的风景的异同。“老师,你看,小燕子真长着剪刀似的尾巴。”“老师,你瞧,燕子斜着身子在天空中飞过,跟书中写的一样。”看着孩子们因为兴奋而涨得通红的小脸,我的心情豁然开朗。 第二天上课,我惊喜地发现,所有的孩子竟然都能把课文非常有感情地背诵了。看着他们摇头晃脑、怡然自得的神情,我有了深深的领悟──课堂教学是一个用生活验证和丰富知识的过程,语文教学更是一个诗意的旅程,教师应是一个称职的导游,而真正看风景的人是学生。记得有一首歌唱到:“风景这边独好,祖国分外妖娆。”而我想说的是:让学生用自己的眼睛和心灵去看风景,风景哪边都好,生活无限美妙!

《2. 古诗两首》教学后记 本课教学采用了“合──分──合”的方式,将两首古诗有机地整合在一起,共同突显“春”这一主题。开课伊始,便将两首古诗和盘托出,让学生通过自读自悟,发现两首诗之间的共同点──都描写了春天,都写到了春风这一事物──从而引出“二月春风似剪刀”,以此导入对《咏柳》一诗的教学。又以“二月春风裁出了……裁出了……裁出了一个万紫千红的春天(出示:万紫千红总是春)”过渡到《春日》一诗。两首古诗的分开教学看似独立,其中又有着千丝万缕的联系,自始至终不离“春”这一主题,为二次整合铺垫基础。 课末,将两首古诗再次整和,进行对比参读。使学生领会到:《咏柳》如细笔勾勒,由一柳而见出整个春天;《春日》则如泼墨挥毫,渲染出春天的“无边光景”,“万紫千红”。然而此处对比的实质并非为求异,而为探求两首古诗内在精神之一致,即对春天的赞美和热爱。至此,学生对春的感悟和热情得以升华,此时,让他们写下心中对春的感受便如水到渠成,一蹴而就。课堂氛围达到高潮。 除了两首古诗之间的整合,本课教学还巧妙地引入朱自清的散文《春》,使古今诗文得以整合。课始,以“盼望着,盼望着,东风来了,春天的脚步近了。”导入新课,揭示了整节课的主题,奠定了课堂的情感基调。课末,以《春》的结尾三段丰富了春的内涵,提升了学生的情感。在这儿,诗、文各有自己独特的语言个性,又具有相同的精神内涵。“诗”是“文”的浓缩,“文”是“诗”的诠释,其有效结合,使学生置身于更广阔的语文空间,营造了课堂的浓浓春意。另外,新旧知识的整合在本堂课中也有体现。课前谈话让学生背诵已学的描写春天的古诗,照顾到了学生的“最近发展区”,课终鼓励学生阅读和摘录有关春天的美诗文是对课堂教学的延伸拓展。

铝合金通用焊接工艺规程 1 使用范围及目的 范围:本规范是适用于地铁铝合金部件焊接全过程的通用工艺要求。目的:与焊接相关的作业人员按标准规范作业,同时也使焊接过程检查更具可操作性。 2 焊前准备的要求 2.1 在焊接作业前首先必须根据图纸检查来料或可见的重要尺寸、形位公差和焊接质量,来料不合格不能进行焊接作业。 2.2 在焊接作业前,必须将残留在产品表面和型腔内的灰尘、飞溅、毛刺、切削液、铝屑及其它杂物清理干净。 2.3 用棉布将来料或工件上的灰尘和脏物擦干净,如果工件上有油污,使用清洗液清理干净。 2.4 使用风动不锈钢丝轮将焊缝区域内的氧化膜打磨干净,以打磨处呈白亮色为标准,打磨区域为焊缝两侧至少25mm以上。 2.5 焊前确认待焊焊缝区域无打磨时断掉的钢丝等杂物。 2.6 钢焊和铝焊的打磨、清理工具禁止混用。 2.7 原则上工件打磨后在48小时内没有进行焊接,酸洗部件在72小时内没有进行焊接,则焊前必须重新打磨焊接区域。 2.8 为保证焊丝的质量,焊丝原则上用完后再到焊丝房领用,对于晚班需换焊丝的,可以在当天白班下班前领用,禁止现场长时间(24小时以上)存放焊丝。 2.9 在焊接作业前,必须检查焊接设备和工装处于正常工作状态。焊 前应检查焊机喷嘴的实际气流量(允差为+3L/min),自动焊焊丝在8圈以下,手工焊焊丝在5圈以上,否则需要更换气体或焊丝;检查导电嘴是否拧紧,喷嘴是否需要清理。导电嘴不能只简单的采用手动拧紧,必须采用尖嘴钳拧紧。检查工装状

态是否完好,若工装有损坏,应立即通知工装管理员进行核查,并组织维修,禁止在工装异常状态下进行焊接操作。 2.10 焊接前必须检查环境的温度和湿度。作业区要求温度在5?以上,MIG焊湿度小于65,,TIG焊湿度小于70,。环境不符合要求,不能进行焊接作业。 2.11 焊接过程中不允许有穿堂风。因此,在焊接作业前必须关闭台位附近的通道门。当焊接过程中,如果有人打开台位相近处的大门,则要立即停止施焊。如果台位附近的空调风影响到焊接作业,也必须将该处空调的排风口关闭,才能进行焊接作业。 2.12 对于厚度在8mm以上(包括8mm)的铝材,焊接要预热,预热温度 80?,120?,层间温度控制在60?,100?。预热时要使用接触式测温仪进行测温,工件板厚不超过50mm时,正对着焊工的工件表面,距坡口表面4倍板厚,最多不超过50mm的距离处测量,当工件厚度超过50mm时,要求的测温点应位于至少75mm距离的母材或坡口任何方向上同一的位置,条件允许时,温度应在加热面的背面上测定,严禁凭个人感觉及经验做事。 2.13 按图纸进行组装,点焊固定,点焊要满足与焊接相同的要求,不属于焊接组成部分的点焊要尽可能在焊接时完全熔化(图纸要求的点焊 除外,如焊接垫板的固定),组焊后不能出现图纸要求之外的焊点,部件固定后按图纸要求进行尺寸、平行度、垂直度等项点的自检,自检合格后,根据图纸进行焊接,操作工人必须及时、真实填写操作记录。 2.14 当图纸要求或工艺要求使用焊接垫板时,应将焊接垫板点焊在工件上,点焊应符合焊接质量要求,点焊要求为:焊接垫板小于100mm时,在焊接垫板两端点焊固定,焊接垫板大于100mm时,根据焊接垫板长度点焊均匀分布,间距100mm。 2.15 为了避免腐蚀,铝合金配件存放时不允许直接采用钢或者铜材质的容器存放,不允许将配件直接放置在钢制的工装或地板上。 2.16 对于焊缝质量等级为

爱护自己的名誉教学反思 2019-05-16 本学期,我担任了三年级的《品德与社会》学科。通过这几周的教学,我深刻的体会到,《品德与社会》这门学科的重要性及综合性,如何上好品德课,希望每一节课学生都有所收获,是我努力的目标。本节课主要的学习目标是使学生理解和懂得自尊、自爱,培养学生分辨是非、美丑,爱护自己的名誉,学习反省自己的生活和行为。上完课后,感觉自己很多地方做得不够,根据听课^领`导的指导及自己的反思把我的问题归结如下: 一、由于刚接触这门学科,对于这门学科的教学方法还不是很熟悉,所以我上课讲的太多,学生说的少,容易上成说教课,导致课堂气氛不够活跃,学生思维受限,表达能力得不到提高。教师应该在这里只起到提问,引导的.作用,让学生明理,然后导行,更多的发挥学生的主动性,提高学生的兴趣。 二、本课中我用到了图片,还有视频进行引导,来让学生去发现,分辨什么是美,什么是丑,一堂课上下来,感到图片与视频的内容有些重复,可以选取其中的一部分作为引导,或者由视频直接导入即可。可以把更多一些的时间放在拓展维护国家名誉这部分,用故事,儿歌等加强学生的爱国主义教育,维护国家名誉。 三、要与学生的生活紧密联系。三年级学生还不能从字面上理解自尊,名誉等词,要使学生理解和懂得自尊、自爱,就要把教学内容与学生生活实际有机结合起来,通过最大限度的与学生的生活紧密结合,深入浅出引导,这样才能达到目标。我这节课结合教材中的事例大做文章,贴近学生的生活不够,应由事例、图片的引导,延伸到现实生活中,延伸到孩子们自己身上,应该主要解决学生生活中实际存在的问题,并不是一味讲道理。最主要的要让学生发现自己及周边的事情,反省自己的生活和行为,最终使他们懂得应该怎样维护自尊,珍惜名誉。 总而言之,通过课后反思把教学实践中的“得”与“失”加以总结,变成自己的教学经验。在不断总结经验教训的基础上,不断提高自身的整体素质,争取努力上好每一节《品德与社会》课,让孩子们在娱乐中学到一点知识,懂得一点道理,得到一点感悟,引发一点思考,在轻松中感到学习的快乐。

铝合金焊接的几种先进工艺:搅拌摩擦焊、激光焊、激光- 电弧复合焊、电子束焊。针对于焊接性不好和曾认为不可焊接的合金提出了有效的解决方法,几种工艺均具有优越性,并可对厚板铝合金进行焊接。 关键词:铝合金搅拌摩擦焊激光焊激光- 电弧复合焊电子束焊 1 铝合金焊接的特点 铝合金由于重量轻、比强度高、耐腐蚀性能好、无磁性、成形性好及低温性能好等特点而被广泛地应用于各种焊接结构产品中,采用铝合金代替钢板材料焊接,结构重量可减轻50 %以上。 铝合金焊接有几大难点: ①铝合金焊接接头软化严重,强度系数低,这也是阻碍铝合金应用的最大障碍; ②铝合金表面易产生难熔的氧化膜(Al2O3 其熔点为2060 ℃) ,这就需要采用大功率密度的焊接工艺; ③铝合金焊接容易产生气孔; ④铝合金焊接易产生热裂纹; ⑤线膨胀系数大,易产生焊接变形; ⑥铝合金热导率大(约为钢的4 倍) ,相同焊接速度下,热输入要比焊接钢材大2~4 倍。 因此,铝合金的焊接要求采用能量密度大、焊接热输入小、焊接速度高的高效焊接方法。 2 铝合金的先进焊接工艺 针对铝合金焊接的难点,近些年来提出了几种新工艺,在交通、航天、航空等行业得到了一定应用,几种新工艺可以很好地解决铝合金焊接的难点,焊后接头性能良好,并可以对以前焊接性不好或不可焊的铝合金进行焊接。 2. 1 铝合金的搅拌摩擦焊接 搅拌摩擦焊FSW( Friction Stir Welding) 是由英国焊接研究所TWI ( The Welding Institute) 1991 年提出的新的固态塑性连接工艺[1~2 ] 。图1为搅拌摩擦焊接示意图[3 ] 。其工作原理是用一种特殊形式的搅拌头插入工件待焊部位,通过搅拌头高速旋转与工件间的搅拌摩擦,摩擦产生热使该部位金属处于热塑性状态,并在搅拌头的压力作用下从其前端向后部塑性流动,从而使焊件压焊在一起。图2 为搅拌摩擦焊接过程[4 ] 。由于搅拌摩擦焊过程中不存在金属的熔化,是一种固态连接过程,故焊接时不存在熔焊的各种缺陷,可以焊接用熔焊方法难以焊接的有色金属材料,如铝及高强铝合金、铜合金、钛合金以及异种材料、复合材料焊接等。目前搅拌摩擦焊在铝合金的焊接方面研究应用较多。已经成功地进行了搅拌摩擦焊接的铝合金包括2000 系列(Al- Cu) 、5000 系列(Al - Mg) 、6000 系列(Al - Mg - Si) 、7000 系列(Al - Zn) 、8000 系列(Al - Li) 等。国外已经.进入工业化生产阶段,在挪威已经应用此技术焊接快艇上长为20 m 的结构件,美国洛克希德·马丁航空航天公司用该项技术焊接了铝合金储存液氧的低温容器火箭结构件。 铝合金搅拌摩擦焊焊缝是经过塑性变形和动态再结晶而形成,焊缝区晶粒细化,无熔焊的树枝晶,组织细密,热影响区较熔化焊时窄,无合金元素烧损、裂纹和气孔等缺陷,综合性能良好。与传统熔焊方法相比,它无飞溅、烟尘,不需要添加焊丝和保护气体,接头性能良好。由于是固相焊接工艺,加热温度低,焊接热影响区显微组织变化小,如亚稳定相基本保持不变,这对于热处理强化铝合金及沉淀强化铝合金非常有利。焊后的残余应力和变形非常小,对于薄板铝合金焊后基本不变形。与普通摩擦焊相比,它可不受轴类零件的限制,可焊接直焊缝、角焊缝。传统焊接工艺焊接铝合金要求对表面进行去除氧化膜,并在48 h 内进行加工,而搅拌摩擦焊工艺只要在焊前去除油污即可,并对装配要求不高。并且搅拌摩擦焊比熔化焊节省能源、污染小。 搅拌摩擦焊铝合金也存在一定的缺点:

学生自我反思与评价: 一、光阴似箭,日月如梭。一眨眼的工夫,一个学期就很快就过去了,又迎来了新的一年,新的学期,又有新的工作等着我们来学,等我们来消化,去理解.在上个学期,我没有好好去学习,去理解,所以在上个学期的考试才会考得那么糟糕,那么差。不过,现在又是新的一年,新的学期,我要整装待发,要以一个全新的我去迎接这个学期的起点站,奋发图强,永不停步。 二、本人能严格遵守学校纪律,有较强的集体荣誉感,乐于助人,关心同学,与同学相处融洽;学习上刻苦努力,思维活跃。是一个正直诚恳,听话懂事,诚实质朴的学生。老师和同学都很喜欢我。学习上虽然很努力,但学习方法不是最佳,所以成绩还不够理想。希望在以后的学习和生活中,能探索出适合我自己的高效的学习方法。 三、我能够尊敬师长,团结同学,基本上能遵守校纪校规。本人自控力还可以,但是也要提高自身的分析识别能力。以后我会在各个方面能够独立自觉,自己管理自己。在学习上,我有提高各科成绩的良好愿望,但这不能只是口头上说说而已,我要用自己的行动来表明我的决心,迎接每一个崭新的明天! 四、本人在校热爱祖国,尊敬师长,团结同学,乐于助人,是老师的好帮手,同学的好朋友。我学习勤奋,积极向上,喜欢和同学讨论并解决问题,经常参加班级学校组织的各种课内外活动。在家尊老爱幼,经常帮爸爸妈妈做家务是家长的好孩子,邻居的好榜样。这个学期,我学到了很多知识,思想比以前有了很大的提高,希望以后能做一个有理想,有抱负,有文化的人,为建设社会主义中国做出自己的努力。当然我也深刻认识到自己的不足,字写的不是很好,有时候做事情会只有三分钟热情,我相信只要克服这些问题,我就能做的更好。 五、在这个学期里,我不能像上个学期一样浪费时间,不懂得珍惜时间,所以,我要在这个学期里自我反思,要珍惜现在的时间,不会再浪费时间了。老师讲的课我没有听懂或者是没有听清楚,下课后,我要马上跑去问老师,直到弄懂课时,要专心听讲,不可以跟前后左右讲小话,要勤做笔记,把老师讲过的重点记下来。回到家里,把今天老师讲过的课文复习一遍,再做老师布置的作业。我会在这个学期里好好学习,争取用优秀的成绩汇报爸爸妈妈。 六、本人能自觉遵守中学生守则,积极参加各项活动,尊敬师长,与同学和睦相处,关心热爱集体,乐于帮助别人,劳动积极肯干,自觉锻炼身体,经常参加并组织班级学校组织的各种课内外活动。 七、考试技巧贵在练习。生活之中,我还要多多加强自己的练习和复习,考试之前制定周详的复习计划,不再手忙脚乱,没有方向。平日生活学习中学会积累,语文积累好词好句,数学也要多积累难的题目,英语则是语法项目。对做完形填空等练习题也是提高英语的好方法。 八、各科老师,我希望老师不要对我失去信心,虽然我这次考得并不理想,但是我相信自己的实力。下一次考试,我一定会努力的! 九、金无足赤,人无完人.十全十美的人在现实生活中是不存在的。可是每个人都有优点,也有缺点。既有长处,也有短处。我一定会努力借鉴别人的优点和长处。在期末考试中,我的成绩并不理想,从现在的这一刻起,我要从零开始,把所有的精力都放在学习上。确立目标。争取在下次考试中考一个理想的成绩。 十、通过这一学期的学习,让我明白了许多道理。我为了一个团结友爱的班集体而感到高兴自豪。我为有许多乐于助人的同学而感到欣慰,我爱我的班集体。 十一、面对未来,我充满希望,相信只要有真心付出,就一定能有所回报,我会在下个学

铝合金焊接工艺 Coca-cola standardization office【ZZ5AB-ZZSYT-ZZ2C-ZZ682T-ZZT18】

铝合金焊接工艺 铝合金具有较高的比强度、断裂韧度、疲劳强度和耐腐蚀稳定性,并且工艺成形性和焊接性能良好,MIG焊是铝合金焊接的主要方法之一。由于铝合金表面华丽的色泽等诸多优点而被广泛应用于航空、航天及其它运载工具的结构材料;如运载火箭的液体燃料箱,超音速飞机和汽车的结构件以及轻型战车的装甲等。本文主要研究了MIG焊接6063铝合金的工艺方法。 焊接材料 焊接所采用的母材为6063铝合金,焊接壁厚在3mm以上时,开V形坡口,夹角为60°~70°,空隙不得大于1mm,以多层焊完结;焊丝所用的材料为5356铝合金焊丝;壁厚在3mm以下时,不开坡口,不留空隙,不加填充丝;焊接薄铝件, 最好是用低温铝焊条WE53。 焊前准备 坡口加工 铝材可采用机械或等离子弧等方法切割下料。 坡口加工采用机械加工法。加工坡口表面高应平整、无毛刺和飞边。 坡口形式和尺寸根据接头型式,母材厚度、焊接位位置、焊接方法、有无垫板及使用条件。 焊接工艺参数的选择 应在焊接工艺规程规定的范围内正确选用焊接工艺参数

表1手工钨术氩弧焊接工艺参数 焊前清洗 首先,用丙酮等有机溶液除去油污,两侧坡口的清理范围不小于50mm,坡口及其附近(包括垫板)的表面应用机械法清理至露出金属光泽。焊丝去除油污后,应采用化学法除去氧化膜,可用5%~10%的NaOH溶液在70℃下浸泡30~60s,清水冲洗后,再用10%的HNO3常温下浸2min,清水冲洗干净后干燥处理。清理后的焊件、焊丝在4h内应尽快完成施焊。 焊接工艺要求 定位焊缝应符合下列规定: 1)焊件组对可在坡口处点焊定位,也可以坡口内点固。焊接定位焊缝时,选用的焊丝应与母材相匹配。 2)定位焊缝就有适当的长度,间距和高度,以保证其有足够的强度面不致在焊接过程中开裂。 3)定位焊缝如发现缺陷应及时处理。对作为正式焊缝一部分的根部定位焊缝,还应将其表面的黑料,氧化膜清除,并将两端修整成缓坡型。

篇一:《珍爱生命热爱生活》教学反思 七年级上册第一单元《珍爱生命热爱生活》(复习课)教学反思 20XX年10月27日,学校安排 听我的考核课,我是思品备课组的第一个,按既定教学计划,第九周开始复习七年级内容,针 对思品学科特点和开卷考试要求,我设计了学思导纲,将复习内容及要求以纸质形式展现给学 生,以便于学生复习和保存。我的设想是通过本节复习,引导学生在加深对重要观点原理的理 解、识记的基础上,对分散在其他单元章节中的相关知识点进行梳理归类和整合,以便形成知 识体系,提升学生知识迁移和综合运用能力。 课堂 上,我按计划运行,由于学生学过的时间较长、加上当时离中考还远学生压根儿不重视,我对 学情把握不准,第二、三两个环节进展不顺利,我不得不指导学生重新整理问题及答案要点、 监督学生做好笔记,时间远远超出了我的设想,但这也给我一个很好的提醒:七八年级的复习 课必须认清学情,踏踏实实抓双基,认认真真抓落。因为有了九年级的复习级强化训练,学生 的知识迁移和运用能力有所提高,第四环节进展还顺利,虽然学生的答案要点不够全面和准确, 但基本没有审错题等大的偏差。价值判断第二小题有难度,多数学生能清晰的找到答题要点之 一:生命的重要性,只有极少数学生能想到另一角度:生命的价值在于创造和奉献,得分率能 达到近70%。情景分析题第1题学生失误较多,表现为学生思路较窄,角度单一,多数学生只 想到只想到与本节内容联系最密切的生命角度,对于同违法犯罪作斗争这一角度多数学生想不 到,少数学生想到了正义这一点,却不能用政治语言表述出来,反映出学生的发散思维欠缺, 在阅读分析抓住关键问题点、运用所学知识解答方面还有欠缺。为此我针对学生展示中暴露的 问题进行了重点点播,引导学生对第1小题进行改正补充并现场让学生梳理审题思路及答题 要点,进一步检查学生的理解运用情况。第2小题由于难度较大我现对题目要求和答题技巧 进行了提示,引导学生班独立思考、内抢答效果还不错,多数学生能踊跃发言,只是当真的让 他们把答案整理出来时,不少学生无从下手、有的比较凌乱缺乏条理,因此指导督促学生整理 笔记的环节不能忽视,否则很难适应开卷考试的要求。由于前面内容耗时较多,课堂检测环 节就没办法按原计划处理了,我只好改变策略,把它改为课后作业,第二天通过作业批阅照样 对学生的课堂学习情况作了较为全面客观的了解处理,剩余的问题作为学生的复习作业。虽然 没有完整的完成预定教学目标,但我也没有为完成教学任务而完成教学任务,我始终坚持以生 为本关注学生状态、重视课堂效果,以学生对知识的掌握情况为施教尺度,关注学生的学,以 此及时调整自己的教学设计,注重细节,讲究实效,绝不让学生吃夹生饭。 这节 课从课文内容梳理、挖掘、整合到问题的设计,我觉得比较适合思品学习成绩前35%的学生, 他们一直处于积极思考认真作答、整理的状态,笔记整理调理完整。 和能力,笔记很难记全、记调理,对知识的掌握也就可想而知了,更有个别学生错别字都很常 见,这样的笔记有多少参考价值,他们又能真正掌握多少、学会多少?本届学生的学习基础和 习惯远比我想象的更差,对于公然不记笔记、不写作业的该从何处入手转变他们?仅九年级一 年的时间、单靠教师单方面的努力能有多少收获?实在不敢奢望。 篇二:珍爱生命班会课反思 “珍爱生命.健康成长”班会课后反思 6月30日第20周的星期一在升国旗前,我们班前几周 一周都在排练小品和诗歌朗诵的同学悄悄问我:“老师,我们今天上班会公开课吗?”“我还不 能确定,我去问一下曾老师。”其实这节班会公开课早就该上了,由于种种事情一拖再拖,一 直拖到现在学期末。虽然自己也在用心改了一次又次教案和课件,学生也在为排练班会中的节 目准备了好久,但是总是自信心不足,感觉很多方面还不够好。而我也一直不能给主管此件事 的曾老师有个交代,心里总是不舒服。在学生的催问下,我终于再次向曾老师表明上公开课的

铁镍基高温合金的焊接性及焊接工艺 一、焊接性 对于固熔强化的高温合金,主要问题是焊缝结晶裂纹和过热区的晶粒长大,焊接接头的“等强度”等。对于沉淀强化的高温合金,除了焊缝的结晶裂纹外,还有液化裂纹和再热裂纹;焊接接头的“等强度”问题也很突出,焊缝和热影响区的强度、塑性往往达不到母材金属的水平。 1、焊缝的热裂纹 铁镍基合金都具有较大的焊接热裂纹倾向,特别是沉淀强化的合金,溶解度有限的元素Ni和Fe,易在晶界处形成低熔点物质,如Ni—Si,Fe—Nb,Ni—B等;同时对某些杂质非常敏感,如:S、P、Pb、Bi、Sn、Ca等;这些高温合金易形成方向性强的单项奥氏体柱状晶,促使杂质偏析;这些高温合金的线膨胀系数很大,易形成较大的焊接应力。 实践证明,沉淀强化的合金比固熔强化合金具有更大的热裂倾向。 影响焊缝产生热裂纹的因素有: ①合金系统特性的影响。 凝固温度区间越大,且固相线低的合金,结晶裂纹倾向越大。如:N—155(30Cr17Ni15Co12Mo3Nb),而S—590(40Cr20Ni20Co20Mo4W4Nb4)裂纹倾向就较小。 ②焊缝中合金元素的影响。 采用不同的焊材,焊缝的热裂倾向有很大的差别。如铁基合金Cr15Ni40W5Mo2Al2Ti3在TIG焊时,选用与母材合金同质的焊丝,即焊缝含有γ/形成元素,结果焊缝产生结晶裂纹;而选用固熔强化型HGH113,Ni—Cr—Mo系焊丝,含有较多的Mo,Mo在高Ni合金中具有很高的溶解度,不会形成易熔物质,故也不会引起热裂纹。含Mo量越高,焊缝的热裂倾向越小;同时Mo还能提高固熔体的扩散激活能,而阻止形成正亚晶界裂纹(多元化裂纹)。 B、Si、Mn含量降低,Ni、Ti成分增加,裂纹减少。 ③变质剂的影响。 用变质剂细化焊缝一次结晶组织,能明显减少热裂倾向。 ④杂质元素的影响。 有害杂质元素,S、P、B等,常常是焊缝产生热裂纹的原因。 ⑤焊接工艺的影响。 焊接接头具有较大的拘束应力,促使焊缝热裂倾向大。采用脉冲氩弧焊或适当减少焊缝电流,以减少熔池的过热,对于提高焊缝的抗热裂性是有益的。 2、热影响区的液化裂纹 低熔点共晶物形成的晶间液膜引起液化裂纹。 A—286的晶界处有Ti、Si、Ni、Mo等元素的偏析,形成低熔点共晶物。 液膜还可以在碳化物相(MC或M6C)的周围形成,如Inconel718,铸造镍基合金B—1900和Inconel713C。 高温合金的晶粒粗细,对裂纹的产生也有很大的影响。焊接时常常在粗晶部位产生液化裂纹。因此,在焊接工艺上,应尽可能采用小焊接线能量,来避免热影响区晶粒的粗化。 对焊接热影响区液化裂纹的控制,关键在于合金本身的材质,去除合金中的杂质,则有利于防止液化裂纹。 3、再热裂纹 γ/形成元素Al、Ti的含量越高,再热裂纹倾向越大。 对于γ/强化合金消除应力退火,加热必须是快速而且均匀,加热曲线要避开等温时效的温度、时间曲线的影响区。 对于固熔态或退火态的母材合金进行焊接时,有利于减少再热裂纹的产生。 焊接工艺上应尽可能选用小焊接线能量,小焊道的多层焊,合理设计接头,以降低焊接结构的拘束度。

GH3030高温合金 GH30固溶强化型高温合金 80Ni-20Cr板 gh3030棒国军标 GH3030(GH30) 固溶强化型变形高温合金 GH3030特性及应用领域概述: 该合金是早期发展的80Ni-20Cr固溶强化型高温合金,化学成分简单,在800℃以下具有满意的热强性和高的塑性,并具有良好的抗氧化、热疲劳、冷冲压和焊接工艺性能。合金经固溶处理后为单相奥氏体,使用过程中组织稳定。主要用于800℃以下工作的涡轮发动机燃烧室部件和在1100℃以下要求抗氧化但承受载荷很小的其他高温部件。 GH3030相近牌号: GH30,Зи435,XH78T(俄罗斯) GH3030 化学成分:(GB/T14992-2005) GH3030物理性能:

GH3030力学性能:(在20℃检测机械性能的最小值) GH3030生产执行标准: GH3030 金相组织结构: 该合金在1000℃固溶处理后为单相奥氏体组织,间有少量TiC和Ti(CN)。GH3030工艺性能与要求: 1、该合金具有良好的可锻性能,锻造加热温度1180℃,终锻900℃。 2、该合金的晶粒度平均尺寸与锻件的变形程度、终锻温度密切相关。 3、热处理后,零件表面氧化皮可用吹砂或酸洗方法清除。 GH3030主要规格: GH3030无缝管、GH3030钢板、GH3030圆钢、GH3030锻件、GH3030法兰、 GH3030圆环、GH3030焊管、GH3030钢带、GH3030直条、GH3030丝材及配套焊材、GH3030圆饼、GH3030扁钢、GH3030六角棒、GH3030大小头、GH3030弯头、GH3030三通、GH3030加工件、GH3030螺栓螺母、GH3030紧固件。 篇幅有限,如需更多更详细介绍,欢迎咨询了解。

“珍爱生命.健康成长”班会课后反思 6月30日第20周的星期一在升国旗前,我们班前几周一周都在排练小品和诗歌朗诵的同学悄悄问我:“老师,我们今天上班会公开课吗?”“我还不能确定,我去问一下曾老师。”其实这节班会公开课早就该上了,由于种种事情一拖再拖,一直拖到现在学期末。虽然自己也在用心改了一次又次教案和课件,学生也在为排练班会中的节目准备了好久,但是总是自信心不足,感觉很多方面还不够好。而我也一直不能给主管此件事的曾老师有个交代,心里总是不舒服。在学生的催问下,我终于再次向曾老师表明上公开课的意识,曾老师当机立断:”今天第一节就可以让大家去你班听课。”而我还是有些不自信,怕上不好,曾老师立即看出了我的心思:“那就我和两个级长一起去听一听。”于是在我的前期准备还算充分,但是自信心还不是很足,,心里准备还不是很充分的情况下上了这节“珍爱生命,健康成长”的班会课。 本节班会上我由小时候家中的两只小鸟痛失小宝宝的故事导入,然后讲到前不久在网上看到的新闻母亲节几位妈妈寻子的故事开始,引出“珍爱生命.健康成长”的主题。在此环节自我感觉这种导入的过程及想法还好。但是由于自己一直想着都到第20周了,可能上不了这个班会课了,所以心里上对这些内容没有提前一点时间再熟悉一下,所以在讲故事的环节中讲得还不够生动和清楚,学生似乎听得也不是很清楚。因此在与学生互动过程中,当我问“这两只小鸟似乎在等着什么”,在问学生时,学生竟然说等待生命,而不是说在等待它

们的孩子。 另外,由于老师的指导水平和学生的素质有限,虽然学生对诗朗诵《生命的顽强》稿子已经背得很熟练,但是感情演绎得还不是很到位,表现还不够大气。演小品的学生,个别学生还是不够放得开,还需要多历练。 当然在此次班会课中,给我感受最深的是:对学生的教育不能只是说教,要多利用班会课,精心设计班会,给学生搭建一个平台,学生将会非常热情地投入其中,在排练与表演的过程中,学生得到了锻炼,感受到付出与体验的快乐。就拿诗歌朗诵来说,我只把稿子给了班上的语文课代表,让她去找班上的同学,大家一起排练,老师从中进行了简单的指导。小品的排练我只是把我的想法告诉班上一位同学,然后让他去找班上愿意表演的同学,我戏称此同学为“陈导”。把权力放手给学生,让他们下午放学后排练,老师只给一些指导性的意见,更多的语言靠他们自己去想,去体会。 我感受到此次班会课虽然谈不上是什么非常成功的班会课,但是它让所有学生不仅在课堂上有了珍爱生命的意识和观念,而且在如何健康成长,如何保护自己方面增强了安全知识和智慧,同时让学生们在班会中得到了锻炼,我想这些都是非常重要的!而我自己,也能在这个过程中感受到教育的力量,感受到孩子们的可爱,感受到自己价值的体现,从中感受到教学的快乐! 2014-07-06

高温合金的焊接性 1 引言 高温合金是航空发动机的关键材料,而镍基及镍铁基高温合金是目前高温合金结构材料的重要组成部分,镍基高温合金由于具有优异的耐热性及耐腐蚀性,被称之为“航空发动机的心脏”,具有组织稳定、工作温度高、合金化能力强等特点,目前已成为航空航天、军工、舰艇燃气机、火箭发动机所必须的重要金属材料,同时在高温化学、原子能工业及地面涡轮等领域得到了广泛的应用。据统计,在国外一些先进的飞机发动机中,高温合金的用量已达发动机重量的55%~60%。用于制造涡轮叶片的材料主要是镍基高温合金,同时镍基高温合金还是目前航空发动机和工业燃汽轮机等热端部件的主要用材,在先进发动机中这种合金的重量占50%以上。从高温合金的发展史来看,高温合金经历了变形高温合金、普通铸造高温合金、定向凝固高温合金、单晶高温合金4个阶段。 低膨胀高温合金具有高强度和低膨胀系数相结合的独特性能, 有良好的冷热疲劳性能, 耐热冲击、抗高压氢脆。自70年代开始研究开发低膨胀高温合金以来, 相继有十几种不同类型的低膨胀高温合金问世, 并被广泛用于航空航天工业中。航空工业上低膨胀高温合金主要用于涡轮发动机机匣、涡轮外环以及封严圈、蜂窝支撑环等零部件的制造, 以缩小叶片与机匣、封套之间的间隙, 降低燃气损失, 提高发动机的推力和效率。美国的CFM—56、V—2500 和F101发动机都大量采用这类合金,有的用量已达到发动机质量的25%。航天工业上采用这类合金制造宇宙飞船和火箭发动机的主燃烧室、涡轮泵和喷嘴等零件。低膨胀高温合金的应用不可避免要涉及到焊接加工。已有的研究表明, 这类合金焊接时存在一定的焊缝结晶裂纹和热影响区微裂纹倾向。这不仅会限制新材料的应用范围, 还有可能引发再热裂纹和疲劳裂纹造成产品的报废, 甚至给飞机的安全飞行埋下严重隐患。因此, 开展低膨胀高温合金的焊接性研究, 研究其焊接裂纹的形成机理、影响因素和控制措施,不仅能够丰富焊接裂纹理论, 而且对于提高航空航天发动机的可靠性和安全性有着重要意义。该领域的研究日益受到人们的重视, 并且取得了一定的进展。 2 低膨胀高温合金的成分特点及焊接性 大致可以把低膨胀高温合金分为四类。第一类是含Nb低膨胀高温合金, 它包括Incoloy 903 和Pyroment CTX—1及国产GH903 。此类合金以Fe-Ni-Co为基, 添加Nb、Ti、Al等元素进行强化。第二类是降Al低膨胀高温合金, 它包括Incoloy 907 和CTX—3及国产GH907。为提高抗应力加速晶界氧化脆性, 此类合金中限制Al含量<0.1%(质量分数),适当提高了Nb含量。第三类是高Si低膨胀高温合金, 它包括Incoloy 909和CTX—909及国产GH909。这类合金是降Al 低膨胀高温合金的改型,其基本成分相同, 仅提高了Si含量。最后一类是抗氧化低膨胀高温合金。已有的关于低膨胀高温合金的研究, 主要集中在Incoloy903上,对于Incoloy907和