Participatory Action in the Countryside A Literature Review

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:235.51 KB

- 文档页数:61

英语partc 流程English Participatory Action Research Cycle (PARC)。

Community-based participatory action research (PARC) is an approach to research that emphasizes the involvement of community members in all aspects of the research process. This approach is based on the belief that community members have valuable knowledge and experience that can contribute to the development of research questions, the design and implementation of research methods, and the interpretation and dissemination of research findings.1. Identify the Problem.The first step in the PARC process is to identify the problem that the research will address. This problem should be something that is important to the community and that can be addressed through research. Once the problem has been identified, the research team can begin to develop a research question that will guide the research process.2. Form a Participatory Action Research Team.The next step is to form a participatory action research team. This team should be made up of community members, researchers, and other stakeholders who are interested in addressing the research problem. The team should work together to develop a research plan and to implement the research methods.3. Collect and Analyze Data.Once the research plan has been developed, the research team can begin to collect and analyze data. This data can be collected through a variety of methods, such as surveys, interviews, focus groups, and observations. The data should be analyzed to identify patterns and trends that can help to answer the research question.4. Interpret and Disseminate the Findings.Once the data has been analyzed, the research team caninterpret the findings and disseminate them to the community. This information can be disseminated through a variety of means, such as reports, presentations, and workshops. The findings should be used to inform decision-making and to develop action plans to address the research problem.5. Take Action.The final step in the PARC process is to take action to address the research problem. This action can be taken by the community members, the researchers, or other stakeholders. The action should be based on the findings of the research and should be designed to make a positive impact on the community.Challenges of Conducting PARC.There are a number of challenges that can arise when conducting PARC. These challenges include:Implementing PARC.Building trust between community members and researchers.Managing the power dynamics between community members and researchers.Ensuring that the research is relevant to the community.Finding funding for the research.Overcoming the Challenges of PARC.There are a number of strategies that can be used to overcome the challenges of conducting PARC. These strategies include:Engaging community members in all aspects of the research process.Building relationships between community members andresearchers.Using participatory methods to collect and analyze data.Disseminating the findings of the research to the community.Taking action to address the research problem.Benefits of PARC.There are a number of benefits to conducting PARC. These benefits include:Increased community involvement in research.Improved research quality.Greater impact of research on the community.Empowerment of community members.Increased capacity for community-based research.Conclusion.PARC is a powerful approach to research that can be used to address a wide range of community problems. By involving community members in all aspects of the research process, PARC can help to ensure that the research is relevant, meaningful, and impactful.。

2024-2025学年冀教版英语初三上学期期末自测试题与参考答案一、听力部分(本大题有20小题,每小题1分,共20分)1、Listen to the conversation and answer the question.A. What is the weather like today?B. Where are they going for the weekend?C. How long will they stay at the beach?Answer: AExplanation: The first speaker mentions, “It’s a sunny day today,” indicating that the weather is nice. The other options are not addressed in the conversation.2、Listen to the dialogue and complete the following sentence.Tom: Hi, Jenny! How was your English test?Jenny: It was okay, but I really need to improve my listening skills.Tom: You should practice listening to English news and podcasts.Jenny: That’s a good idea. Thanks for the advice, Tom.Answer: listening skillsExplanation: In the dialogue, Jenny expresses her need to improve her listening skills, which is the missing information in the sentence completion.3.How are the speakers feeling now?A. ExcitedB. UpsetC. ConfusedD. RelaxedAnswer: BExplanation: In this conversation, the speakers are discussing how they feel about a recent event. One of them mentions feeling upset about a thing that happened, which is why option B, “Upset,” is the correct answer.4.Which activity are the two friends planning to do together?A. Go to a movieB. Play video gamesC. Prepare for the final examsD. Go shoppingAnswer: AExplanation: The two friends are discussing their plans for the weekend. One of them suggests watching a movie, implying that they will go to the cinema together. Therefore, option A, “Go to a movie,” is the right answer.5、What does the woman suggest doing?•A) Going to the cinema.•B) Watching TV at home.•C) Having dinner together.•D) Playing video games.Answer: CExplanation: The woman suggests having dinner together because she says, “How about we grab some dinner? I know a great place.”6、Where are the speakers going to meet?•A) At the bus stop.•B) In front of the school gate.•C) At the library entrance.•D) Near the park.Answer: BExplanation: The man mentions meeting “at the school gate,” indicating that they have agreed to meet in front of the school gate.Note: Remember to listen carefully and choose the most appropriate response based on what you hear.7、Question: What does the man say about his hobby?A) He enjoys playing football.B) He is interested in painting.C) He likes reading books.D) He prefers playing chess.Answer: BExplanation: The man mentions, “Well, my hobby is painting. I find it very relaxing and it helps me express my creativity.” Therefore, the correct answer is B.8、Question: Why does the woman apologize to the man?A) Because she is late for the meeting.B) Because she has lost his phone.C) Because she didn’t understand his message.D) Because she has caused him some trouble.Answer: DExplanation: The woman says, “I’m so sorry for the trouble I’ve caused you. I should have been more careful with your phone.” This implies that she has caused him some trouble, making D the correct answer.9、 What does the man want to do?Answer: CExplanation: The man wants to find a quiet place to work on his project. He mentions that he needs a quiet desk and has looked everywhere but not found one yet.10.Where will the woman go most probably?Answer: AExplanation: The woman decides to go to the park to relax and enjoy the weather. She mentions that the sun is shining and the weather is nice, which implies she will probably go to the park to take a walk and enjoy the nice weather.11、What is the main subject of the article discussed in the following interview?A. Why students are spending more time on mobile phones.B. The effects of social media on students’ academic performance.C. How teachers can better communicate with their students.D. The most popular subjects in high school.Answer: BExplanation: In this conversation, the speakers discuss how social media affects students’ academic performance, making option B the correct answer. The other options are mentioned but not as the main subject.12、Listen to the dialogue and choose the correct reason for the woman’s visit to the dentist.A. She has a toothache.B. She wants to have a teeth cleaning.C. She needs to discuss her facial aesthetics.D. She is doing a survey on people’s dental hygiene.Answer: AExplanation: The woman mentions having a toothache as the reason for her visit in the dialogue. Although the other options are also discussed briefly, the main reason is the toothache. Therefore, option A is the correct answer.13、What does the woman want to buy?A. A coatB. A dressC. A hatAnswer: B. A dressExplanation: In the conversation, the woman mentions she is looking forsomething suitable for a formal dinner party. The man suggests several options, but the woman clearly states her preference for a dress.14、Where are they going to meet?A. At the bus stopB. In front of the libraryC. At the train stationAnswer: C. At the train stationExplanation:The dialogue indicates that the speakers are planning to travel together. When discussing their meeting point, one of them suggests the train station because it’s easier to find and has more frequent departures compared to the bus stop.15.You are listening to a conversation between two students, Alex and Sam, discussing their weekend plans.Alex: Hey Sam, are you going anywhere this weekend?Sam: Yeah, actually. I’m planning to go hiking in the mountains with some friends.Alex: That sounds amazing! Are you taking any supplies with you?Sam: Definitely. We’re bringing water, food, and some first aid kits. What about you, Alex?Alex: I’m just staying home. I think I’ll just relax and catch up on some reading.Question: What is Sam’s plan for the weekend?A) Staying home and readingB) Going hiking with friendsC) Visiting familyD) Going to a concertAnswer: B) Going hiking with friendsExplanation: In the conversation, Sam mentions that he is planning to go hiking in the mountains with some friends, which directly answers the question.16.Listen to a short dialogue between a teacher and a student about an upcoming science project.Teacher: Hi Emily, I see you’re working on your science project. How’s it coming along?Emily: Hi Mrs. Johnson. It’s going okay, but I’m a bit stuck on the experi ment. I’m not sure which variables to control.Teacher: Well, remember, Emily, it’s important to isolate one variable at a time to see its effect. Have you thought about what your hypothesis is?Emily: Yes, I think my hypothesis is that adding more sunlight will increase the growth rate of the plants.Teacher: That’s a good start. Now, think about what you need to control to test that hypothesis effectively.Emily: Oh, I see. I’ll need to keep the amount of water and soil the same for all the plants.Question: What is Emily’s hypothesis for her science project?A) Adding more water will increase the growth rate of the plants.B) Adding more sunlight will increase the growth rate of the plants.C) Adding more soil will increase the growth rate of the plants.D) Using different types of fertilizers will increase the growth rate of the plants.Answer: B) Adding more sunlight will increase the growth rate of the plants.Explanation: Emily explicitly states her hypothesis to the teacher, which is that adding more sunlight will increase the growth rate of the plants. This makes option B the correct answer.17、Conversation One, Questions 17-18.听力材料:W: Hi, Tom. How was your weekend?M: It was good, thanks. I went mountain climbing with some friends.W: Really? That sounds cool. Did you have any difficulties?M: Not really. It was fun and everyone was friendly.W: Did you take any photos?M: Yes, I took a few and they look great. I’ll show you later.17.What did Tom do last weekend?A. He went mountain climbing.B. He stayed at home.C. He watched TV.Answer: A. He went mountain climbing.Explanation: The man mentions that he went mountain climbing with some friends during his weekend. This is the activity discussed in the conversation, so the correct answer is A.18.What does the woman want to see?A. Tom’s photos.B. Tom’s friends.C. Tom’s climbing gear.Answer: A. Tom’s photos.Explanation: At the end of the conversation, the woman says, “I’ll show you lat er,” which refers to the photos Tom took during his weekend activity. Hence, the correct answer is A.19、What does the man suggest doing on Sunday?•A) Visiting a museum•B) Watching a movie•C) Going hiking•D) Having a picnicAnswer: CExplanation: In the dialogue, the man suggests going hiking as it’s a nice day outside, which matches option C.20、How will the woman go to the airport?•A) By bus•B) By taxi•C) By subway•D) By carAnswer: BExplanation: The woman mentions that taking a taxi is more convenient and faster, even though it’s more expensive, indicating she will choose to go by taxi, which is option B.二、阅读理解(30分)Title: A Trip to the CountrysideRead the following passage:Last summer, my family decided to take a trip to the countryside. We had always wanted to experience the peacefulness and beauty of the rural areas. We packed our bags and set off early in the morning.Our first stop was a small village located at the foot of a mountain. The village was surrounded by lush green fields and a river that meandered through it. We were greeted warmly by the villagers who showed us around the village. They took us to see their traditional houses made of mud and straw. The houses were simple but very comfortable. We also visited a local market where we bought fresh vegetables and fruits.After exploring the village, we continued our journey to a nearby forest. The forest was dense with tall trees and colorful flowers. We took a hike and enjoyed the fresh air and the beautiful scenery. We even saw some wild animals,such as squirrels and birds, which were a delight to watch.Our last destination was a small lake where we spent the evening. The lake was surrounded by a dense forest and the water was crystal clear. We had a picnic by the lake and watched the sunset. The sky turned into a beautiful tapestry of colors as the sun dipped below the horizon.The trip to the countryside was an unforgettable experience. It was a perfect blend of adventure, relaxation, and learning about the local culture.Questions:1.What was the main purpose of the family’s trip?A) To visit their relatives in the countryside.B) To experience the peacefulness and beauty of the rural areas.C) To learn about local history.D) To participate in agricultural activities.2.What did the villagers show the family in the village?A) The local hospital.B) The village school.C) Traditional houses made of mud and straw.D) The local museum.3.What activity did the family enjoy most during their trip?A) Visiting the local market.B) Hiking in the forest.C) Having a picnic by the lake.D) Watching the sunset.Answers:1.B2.C3.B三、完型填空(15分)Passage:In the early morning, the sun was still hidden behind the thick clouds. The village(1)_________(was, were) quiet, and only a few birds could be heard singing in the trees. John, a young boy, (2)_________(was, were) awake and dressed in his best clothes. He was (3)_________(not, didn’t) looking forward to the day that lay ahead. The teacher had promised a special surprise for those who (4)_________(did, does) well in the upcoming exam. John knew that the test would be difficult, but he was determined to try his best.Questions:3.(1)_________4.(2)_________5.(3)_________Answers:3.(was)4.(was)5.(didn’t)Feel free to ask if you need more questions or any further assistance!四、语法填空题(本大题有10小题,每小题1分,共10分)1、They___________(need) more time to finish the project.A. needsB. needC. needtedD. neededAnswer: B. needExplanation: The sentence is in the present tense, which is the correct tense to use when the subject “They” is plural. Therefore, the correct form is the base form of the verb “need,” which is “need.”2、If I___________(know) the answer, I would have helped you with the problem.A. knewB. had knownC. have knownD. knowAnswer: B. had knownExplanation: The sentence describes a hypothetical past situation where the condition (knowing the answer) was not met. The correct past perfect form to express this is “had known,” indicating that the action of knowing the answer was completed before the main clause’s past action (helping someone).3、so that•Answer: so that•Explanation: The correct choice here is “so that” because it introducesa purpose clause, showing the reason why managing time effectively helpsstudents achieve better results. The clause “they can achieve better results without feeling overwhelmed” explains the purpose of balancing academic work and leisure activities.4、because•Answer: because•Explanation: The term “because” is used here to introduce a cause or reason, which explains why time management skills are important. The clause “they help students prioritize tasks and meet deadlinese fficiently” gives the reason for the importance of these skills.5.In the__________(be) of the earthquake, many buildings collapsed and people were injured.答案:beeing解析:本题考查现在分词作状语。

乡村民间音乐的特点是什么英语作文The Characteristics of Folk Music in the CountrysideFolk music in the countryside has a unique charm that resonates with people from all walks of life. Its distinctive characteristics are deeply rooted in the traditional cultures and customs of rural communities, reflecting the rich history and heritage of a bygone era. In this essay, we will explore the key features that make countryside folk music so special.One of the most prominent characteristics of countryside folk music is its simplicity and sincerity. Unlike the elaborate compositions of classical music or the polished productions of pop music, folk music in the countryside is often raw and unadorned, capturing the raw emotions and authentic experiences of everyday people. The lyrics are usually straightforward and down-to-earth, telling tales of love, loss, struggle, and triumph in a language that everyone can understand.Another defining feature of countryside folk music is its strong ties to nature and the rural landscape. Many traditional folk songs are inspired by the sights and sounds of the countryside, with themes that revolve around the changingseasons, the beauty of the natural world, and the backbreaking work of farming and rural life. The music is often performed outdoors, in open fields or around campfires, creating a deep connection between the music and its natural surroundings.In addition, countryside folk music is characterized by its sense of community and shared heritage. In rural areas, music is often passed down through generations, with families and neighbors coming together to sing and play traditional songs at community gatherings, festivals, and celebrations. The music serves as a way to preserve and honor the history and culture of the countryside, creating a sense of unity and solidarity among the people who call the rural landscape home.Furthermore, countryside folk music is known for its improvisational and participatory nature. Unlike formal musical performances, which are often highly choreographed and rehearsed, folk music in the countryside is spontaneous and inclusive, allowing for impromptu collaborations and contributions from anyone who wishes to join in. Musicians often play by ear, without sheet music or formal training, relying instead on their instincts and intuition to guide their performance.Overall, the characteristics of countryside folk music – its simplicity, sincerity, connection to nature, sense of community, and improvisational spirit – all contribute to its enduring appeal and timeless beauty. In an increasingly fast-paced and technology-driven world, the music of the countryside offers a glimpse into a simpler, more authentic way of life, reminding us of the power of music to unite, inspire, and uplift the human spirit. As we continue to celebrate and preserve the traditions of rural communities, let us also honor the enduring legacy of countryside folk music, which continues to touch hearts and souls around the world.。

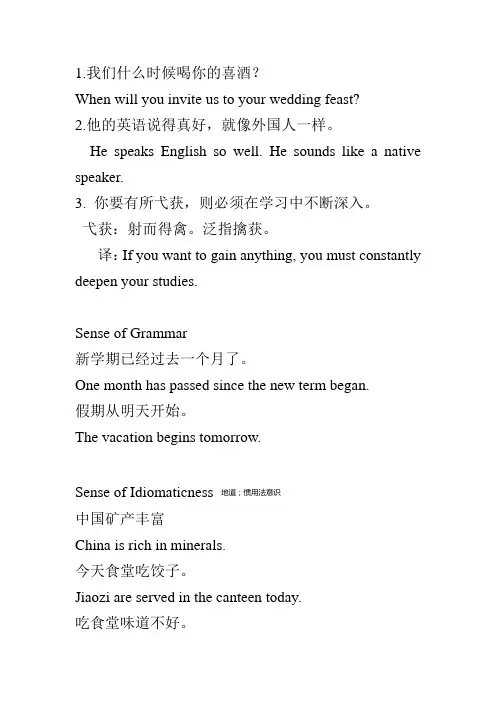

1.我们什么时候喝你的喜酒?When will you invite us to your wedding feast?2.他的英语说得真好,就像外国人一样。

He speaks English so well. He sounds like a native speaker.3. 你要有所弋获,则必须在学习中不断深入。

弋获:射而得禽。

泛指擒获。

译:If you want to gain anything, you must constantly deepen your studies.Sense of Grammar新学期已经过去一个月了。

One month has passed since the new term began.假期从明天开始。

The vacation begins tomorrow.Sense of Idiomaticness 地道;惯用法意识中国矿产丰富China is rich in minerals.今天食堂吃饺子。

Jiaozi are served in the canteen today.吃食堂味道不好。

The food served in the canteen doesn’t taste good.Sense of Coherence连贯性;条理性我家里生活苦,父亲做小买卖,妈妈是家庭妇女,弟弟妹妹多,家里最大的是我,才十三岁,就唱戏养家了。

My family was hard up, with Father a peddler, Mother a housewife, and so many children to feed. At thirteen, as the eldest child, I acted to help support the family.办年货to do Spring Festival shopping坐月子the new mother’s month-long confinement for relaxation1.他本来想要多给你一点帮助的,只是他近来太忙了。

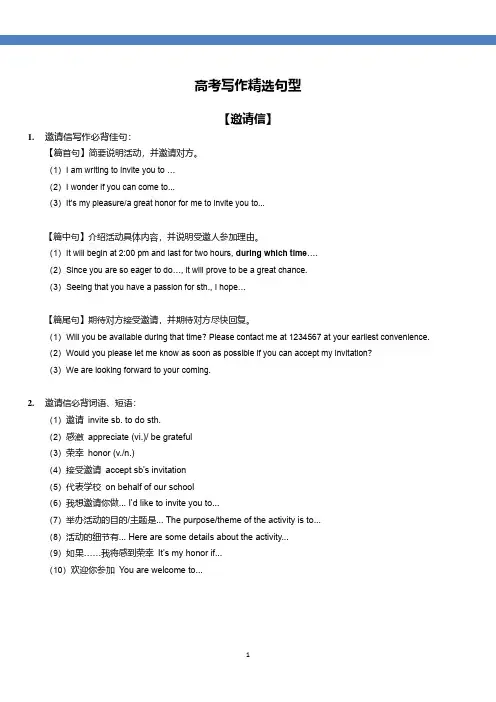

高考写作精选句型【邀请信】1.邀请信写作必背佳句:【篇首句】简要说明活动,并邀请对方。

(1)I am writing to invite you to …(2)I wonder if you can come to...(3)It’s my pleasure/a great honor for me to invite you to...【篇中句】介绍活动具体内容,并说明受邀人参加理由。

(1)It will begin at 2:00 pm and last for two hours, during which time….(2)Since you are so eager to do…, it will prove to be a great chance.(3)Seeing that you have a passion for sth., I hope…【篇尾句】期待对方接受邀请,并期待对方尽快回复。

(1)Will you be available during that time? Please contact me at 1234567 at your earliest convenience.(2)Would you please let me know as soon as possible if you can accept my invitation?(3)We are looking forward to your coming.2.邀请信必背词语、短语:(1)邀请invite sb. to do sth.(2)感激appreciate (vi.)/ be grateful(3)荣幸honor (v./n.)(4)接受邀请accept sb’s invitation(5)代表学校on behalf of our school(6)我想邀请你做... I’d like to invite you to...(7)举办活动的目的/主题是... The purpose/theme of the activity is to...(8)活动的细节有... Here are some details about the activity...(9)如果……我将感到荣幸It’s my honor if...(10)欢迎你参加You are welcome to...1.第一段:照应材料,表明意图。

北师⼤版⾼中英语必修三U7知识点1.keep …in mind =bear …in mind 记住be in one’s mind 有……想法,想念……be on one’s mind 压在⼼头,有⼼事bring (back) to mind 使……想起change one’s mind=alter one’s mind改变主意keep one’s mind on 专⼼于……,聚精会神做……make up one’s mind to do sth. 下决⼼,决定to one’s mind 照……看来be of one mind(=be of the same mind) 想法⼀致,同⼼同德mind one’s own business 少管闲事never mind 没关系;别介意例⼦:(1)I have tried to keep his advice in mind when writing this book.(2) I think I know what is in your mind.(3) Please tell me what is on your mind.(4)The story you have just told brings to mind a strange thing that happened to me.(5)Nothing could change his mind, so the meeting broke up.(6) I found it hard to keep my mind on what he was saying.(7)Have you made up your mind to do what I told you?(8)I’m surprised at his doing such things; it’s dishonest, to my mind.2.as …as possible=as …as sb. can尽量Please be as kind to her as possible.Please be as kind to her as you can.3.participate vi. 参加,参与;分享participate with sb. in sth. 与某⼈分享/分担……participant n. 参加者,参与者participating adj. 由多⼈(或多⽅)⼀起参加的participation n. 参与,参加,分享participatory adj。

Agritourism,or farm tourism,is a form of rural tourism that allows visitors to experience the life and culture of the countryside.Heres a detailed description of what a visit to a typical agritourism site might entail:1.Arrival and Welcome:Upon arrival at the agritourism site,guests are usually greeted by the hosts who provide a warm welcome and a brief introduction to the farm and its activities.2.Accommodation:Guests can stay in various types of accommodations,ranging from traditional farmhouses to modern ecofriendly lodges.These accommodations are often designed to blend in with the natural surroundings,providing a comfortable and authentic experience.3.Exploring the Farm:Visitors are often given a tour of the farm,where they can learn about the different types of crops grown,the farming methods used,and the importance of sustainable agriculture.4.Participating in Farm Activities:One of the main attractions of agritourism is the opportunity to participate in various farm activities.This can include tasks such as planting,harvesting,feeding animals,or even milking cows.These handson experiences provide a deeper understanding of the hard work involved in farming.cational Workshops:Many agritourism sites offer workshops or demonstrations on topics such as cheese making,bread baking,or wine production.These educational sessions not only teach guests new skills but also highlight the value of traditional practices.6.Enjoying Local Cuisine:A key aspect of agritourism is the opportunity to taste and enjoy local produce.Meals are often prepared using ingredients sourced directly from the farm,providing a fresh and authentic dining experience.7.Relaxation and Recreation:In addition to the educational and participatory aspects, agritourism sites also offer opportunities for relaxation and recreation.This can include leisurely walks through the countryside,bike rides,or simply enjoying the peace and tranquility of the rural setting.8.Cultural Experiences:Agritourism often includes elements of local culture,such as traditional music,dance,or storytelling sessions.These cultural experiences help to preserve and promote the heritage of the region.9.Shopping for Local Products:Many agritourism sites have a shop where guests can purchase local products,such as homemade jams,honey,or wine.This not only supports the local economy but also allows visitors to take a piece of the agritourism experience home with them.10.Sustainability and Conservation:A commitment to sustainability is often a key feature of agritourism.This can include practices such as organic farming,water conservation,and the use of renewable energy sources.In conclusion,agritourism offers a unique and enriching experience that combines education,participation,and enjoyment of the natural environment.It is a way to support local communities,promote sustainable practices,and foster a deeper appreciation for the origins of the food we eat.。

高考英语写作技巧练习题50题(带答案)1. In modern society, more and more people ______ the importance of environmental protection.A. realizeB. knowC. understandD. recognize答案:A。

解析:realize强调经过思考、推理等后意识到某个事实或情况,在这里表达人们经过思考后意识到环保的重要性,最为贴切。

know只是单纯表示知道,语义较浅。

understand更多侧重于理解内涵等,在此语境下不如realize准确。

recognize侧重于识别出、辨认出,与题意不符。

2. On campus, students often ______ in various extracurricular activities.A. participateB. joinC. take partD. enter答案:A。

解析:participate in是固定搭配,表示参加,强调参与活动的过程。

join后面一般接组织、团体等。

take part后面要加in才能接活动。

enter主要表示进入某个地方,不用于参加活动。

3. The new policy has a great ______ on people's daily lives.B. affectC. influenceD. impact答案:D。

解析:have an impact on是固定搭配,表示对有重大影响。

effect虽然也有影响的意思,但搭配是have an effect on,这里少了an。

affect是动词,这里需要名词,所以不对。

influence虽然也可表示影响,但impact更强调冲击力、影响力,在这个语境下更合适。

4. When writing about a scientific discovery, we should use ______ language.A. accurateB. correctC. rightD. proper答案:A。

乡村振兴英语介词练习30题1. In the countryside, the harvest is usually in ____ autumn.A. aB. anC. theD. /答案:D。

in autumn 表示“在秋天”,季节前不用冠词,A 选项“a”和B 选项“an”是不定冠词,C 选项“the”是定冠词,都不符合此处用法。

2. The new school was built ____ the east of the village.A. inB. onC. atD. to答案:A。

“in the east of...”表示“在......的东部(内部)”,学校在村子内部的东边,B 选项“on the east of...”表示“在......的东边( 接壤)”,C 选项“at”通常表示小地点,D 选项“to the east of...”表示“在......的东边 外部)”,均不符合题意。

3. The flowers come out ____ spring.A. atB. inC. on答案:B。

“in spring”表示“在春天”,A 选项“at”用于具体时刻,C 选项“on”用于具体某一天,D 选项“of”表示“......的”,不符合此处语境。

4. The farmers are busy working ____ the fields.A. inB. onC. atD. to答案:A。

“in the fields”表示“在田地里”,是固定搭配,B 选项“on”用于表面,C 选项“at”用于小地点,D 选项“to”表示方向,均不符合。

5. The changes of the countryside happened ____ the past few years.A. inB. onC. atD. during答案:D。

“during the past few years”表示“在过去的几年里”,A 选项“in”通常接一段时间,不强调过程,B 选项“on”用于具体某一天,C 选项“at”用于具体时刻,都不符合此处表达。

PARTICIPATORY ACTION IN THE COUNTRYSIDE A LITERATURE REVIEWDiane Warburtonfor theCountryside CommissionAugust 19971Introduction 4•This Review4•The Countryside Commission and participatory action4 2What is participation?7•Definitions7•Ends or means9•Power 9 3Who participates?11•Community11•Other interests (visitors and users, sociations, viewers, publicinterest, professionals, disadvantaged groups, volunteers)12•Where should participation happen?16•Community•Local•Beyond the local4Participation in other fields17•Social welfare17•Housing17•International development18 5Participation in environmental planning andmanagement20•Planning20•Regeneration20•Sustainable development21•Global•Europe•United Kingdom•UK local government•National Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs)24•Countryside Commission 24 6Why has participation grown in recent years?26•Practical benefits of participation 26•Efficiency and effectiveness•Ethics•Public demand•Possible costs and dangers of participation29•Changing political context 30•Changing role of government•Changing view of management•Changing world view•New political action•Communitarianism and social capital•New social movements•Participation: conservative or radical?•Institutions and participation: risk and trust•Institutional barriers to increased participation•Summary of analysis of the growth of participation367How to increase participation in programmes38•Willingness to change38•Commitment to participation38•Balancing participation, statutory duties and publicaccountability39•Principles of good practice40•Participation for its own sake•Clarity of purpose, and stance•The importance of context•Timing•General principles of good practice•Participation requires resources43•Choosing the appropriate techniques44•Preparation for participation•Participatory approaches•Participatory techniques and mechanisms•Participatory fact-finding and analysis•Information giving•Structures for participation•Support agencies and techniques•Assessing whether participation has been successful48 8Overall summary 51 9Conclusions and recommendations52•Responses to questions in the Brief52•Is participation a 'good thing'?•Is participation understood, applied and achievedby public officers, professionals, companies,educationalists, communities and individuals?•Is there is a consensus on any aspects of thedebate on environmental participation?•Conclusions for the Commission54•Recommendations for the Commission55 10AppendicesAppendix 1.Agenda 21 and participatory actionAppendix 2.Current Countryside Commission programmesand participationAppendix 3.Booklist for participatory action in the countrysideAppendix 4.Author index to booklist (and full bibliography for report)1.INTRODUCTIONThis ReviewThis literature review was commissioned by the Countryside Commission in February 1997 to:•examine the wider policy context in which participatory action in the countryside operates•test some of the underlying assumptions about participation•make recommendations on how the lessons from the literature can be applied to the Commission's programmes.The review was undertaken essentially as a desk exercise, culminating in a complete first draft in April 1997. It is not a review of practice (generally or within the Commission), nor is it a practical guide to 'doing participation'.The findings of the research were presented to two seminars of Commission staff, in York and in London, in June 1997. These seminars were invaluable in relating sometimes highly abstract analysis to specific policy priorities for the Commission. The key issues in those seminar discussions have been incorporated, wherever possible, into this final report.The brief for the review identified a number of key questions to be addressed, including:•Is the assumption that participation is a 'good thing' borne out by documentation on principles and practices?•How much is actually known about how far participation is understood, applied and achieved by public officers, professionals, companies, educationalists, communitiesand individuals?•Is there a consensus view on all (or any) aspects of the debate on environmental participation?These questions are specifically addressed in the Conclusions section of this report, together with proposed actions for the Commission to consider, in order to support increasing participation in the Commission's programmes and strategy development.The Countryside Commission and participatory actionThe Countryside Commission already has a long tradition of supporting participatory action in the countryside.It has developed the concept of Participatory Action in the Countryside (PAC) which it has defined as "the principle and means by which decisions are made, action is taken and management applied by and on behalf of all the stakeholders in a locality or community affected by countryside conservation or recreational change" (Brief). This approach is based on its own experience (from its Groundwork programme, its community action programme, its involvement in Rural Action for the environment, and numerous other initiatives) that programmes which develop wider ownership by stakeholders result in more effective and more sustainable solutions to the issues it wishes to address.The Commission's overall aim is "The Countryside Commission aims to make sure that the English countryside is protected, and can be used and enjoyed now and in the future" (Countryside Commission 1996). This can be interpreted as a twofold mission, encompassing conservation and participation: conservation through protection of the countryside, and participation through the use and enjoyment of the countryside.The participatory element of the Commission's overall work can itself be seen as twofold: participation as involvement in activity, and participation as involvement in planning and decision-making. The Commission's ten year strategy, A Living Countryside, attaches great importance to both types of participation. As well as promoting leisure uses of the countryside, it argues for "more open public commitment and partnership in decision-making and project management [with the expectation that] greater local or community ownership of problems and solutions will ensure the sustainability of action taken to protect the countryside itself" (Brief).Taken together, these statements all incorporate a clear recognition that participation is not an optional extra for the Commission's work: it is an essential element. This is reflected in the numerous participatory mechanisms and approaches being developed in the Commission's current priority policy areas (see Section 5 below, and Appendix 2, for details). The Commission's commitment to participation appears to have developed as a result of a number of factors:•Broader policy developments. The Commission's own priorities are set within the broad principles of sustainable development. The Commission recognises that "theGovernment wants sustainable development to be reflected in all policies ... [and has] outlined the action needed in this country to protect the world's wildlife. We expectto play a full part in taking this action forward" (Countryside Commission 1996, 2).The Commission's policy and strategy are explicitly set within the guiding framework of the overall UK policy on sustainable development, which is itself set within theprinciples of Agenda 21 and the Rio Declaration agreed at the United NationsConference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in 1992. The EuropeanUnion's 5th Environmental Action Programme, Towards Sustainability, alsoinfluences Commission programmes (Commission of the European Communities1992).All these programmes and policies place great emphasis on public and communityparticipation as key mechanisms for engaging in sustainable development (seeSection 5, and Appendix 1, for details).•Public service principles. In an era when public trust in public institutions is at an historically low level, the Commission recognises the need to validate and gainsupport for its approaches and programmes through public debate and involvement:rebuilding trust through dialogue and collaborative participatory action.•Desire to widen constituency. The Commission understands that the countryside has an importance which includes and goes beyond local interest, and that theinterests of all stakeholders need to be taken into account by extending participation to those who may in the past have been excluded from involvement.•Limited resources. The Commission accepts that it cannot achieve its ambitious objectives for the countryside alone: its programmes require participation fromothers in a range of relationships.These relationships vary, depending on the specific programme objectives and theinterests of stakeholders and potential partners such as local authorities, otherpublic bodies, local residents, farmers and other landowners and managers, visitors,conservation groups, voluntary organisations, community groups and the public ingeneral.However, the Commission also recognises its limits in terms of developingparticipatory action:•It has statutory duties in relation to conservation, which need to be fulfilled•It has time constraints•It usually operates relatively short term programmes•There is a lack of staff time for new developments•It has size constraints•The organisation is too small to work locally throughout the country •It has priority constraints•It must work strategically and nationally, not in an executive role atlocal level•It is not neutral: it has its own agenda (and therefore cannot simply'facilitate', even if it wanted to)•it is not a community development organisation but it wishes to workin a way that supports sustainable community development, and towork in partnership with agencies and groups which are concernedwith community development (particularly local authorities andthrough Local Agenda 21 groupings)In spite of these constraints, the Commission remains committed to investigating ways of increasing participation in its work. This Review is just one element of the Commission's continuing work in this field.2.WHAT IS PARTICIPATION?DefinitionsParticipation means different things to different people but it is essentially to do with involving the people affected by decisions in making, implementing and monitoring those decisions. Numerous attempts have been made to define participation, although it is generally recognised that "Participation defies any single attempt at definition or interpretation" (Oakley 1991, 6).However, it is crucial that some common understanding of participation is achieved in order to progress the debate. Some contributions to the debate are given below:•"Participation is concerned with human development and increases people's sense of control over issues which affect their lives, helps them to learn how to plan andimplement and, on a broader front, prepares them for participation at regional oreven national level. In essence, participation is a 'good thing' because it breakspeople's isolation and lays the groundwork for them to have not only a moresubstantial influence on development, but also a greater independence and controlover their lives" (Oakley 1991, 17).•Participation can also be understood in terms of its difference from conventional project management: "Participation is radically different from conventional projectpractice ... experimentation is the order of the day; structured but sensitive,manageable and yet not controlled" (Oakley 1991, 270).However, even though there seems to be a consensus on paper about what participation is, there are "clearly fundamentally opposed views as to what participation means in practice" (ibid 269). Oakley argues that there is a fundamental difference between participatory development (top-down), and participation in development (bottom up).Some attempts at definition of some of the other key terms in participatory practice are given below:•Capacity building: "Training and other methods to help people develop the confidence and skills necessary for them to achieve their purpose" (Wilcox 1994, 31).Chambers prefers the term 'capability', by which he means "the quality of beingcapable; the ability to do something" (Chambers 1997, xiv) .•Community action: Describes those activities which people undertake themselves to improve the quality of their own lives within their communities. In environmental terms it can range from direct action to save or improve land or buildings, to lobbying for changes in policy or legislation, with activities as diverse as setting up housing co-operatives, allotment societies, village appraisals, revitalising local customs, trafficcampaigns, city farms and large scale multi-objective organisations like development trusts. The key aspects of community action are that it is done by people forthemselves, it is done locally and it involves control by local people.•Community development: The method or approach used by community workers, agencies and others to encourage and support community action. Three usefuldefinitions of community development are given below:•"Community development is concerned with change and growth - with giving people more power over the changes that are taking place around them, thepolicies that affect them and the services they use. It seeks to enableindividuals and communities to grow and change according to their ownneeds and priorities rather than those dictated by circumstances beyond theirboundaries. It works through bringing people together to share skills,knowledge and experience in the belief that it is through working togetherthat they will reach their full potential" (Taylor 1992).•"Community development is a process which aims to make real and to extend participative democracy. Through its activities, the rights of citizenship areclaimed for traditionally unheard and powerless people. Social needs andindividuals problems are turned into public issues to be tackled throughcollective activity, so that the people involved build up their personal skillsand confidence and take a greater control of their communal life" (Flecknoe& McLellan 1994, 5).•"Community development is seen as assisting people to: 'tackle forthemselves the problems which they face and identify to be important'. Thecommunity then plays the leading role in defining both the problems to beaddressed and the manner of responding to them" (Voluntary Activity Unit1996).•Community education: "Community education is a process by which education workers engage with local people in a learning programme ... a process wherebysmall groups of people are gathered together around a clear set of objectives toengage in a learning process which has tangible outcomes for them as clients" (Fagan 1993, 9)•Community involvement: This takes place when a process or project is defined and controlled outside the community: for example, involvement in a woodlandconservation project proposed and managed by an outside organisation. Communityinvolvement can work at a number of levels from simply giving information about the project to local people, to substantial involvement in the design and aftercare of thescheme, but always stops short of ultimate responsibility or control.•Community work: The profession (whether paid or not) of encouraging and supporting (or enabling) community action. There are numerous links betweencommunity action, community work and community development: experiencedcommunity activists may become paid community workers engaged in a communitydevelopment project.•Consultation: Have deliberations (with person); seek information or advice from;take into consideration (Concise Oxford English Dictionary)•Empower: Authorise, license (person to do); give power to, make able (person to do) (Concise Oxford English Dictionary)•Participation: Have share, take part; have something of (Concise Oxford English Dictionary)•Voluntary action: Essentially undertaken for the benefit of others (eg Meals on Wheels) and well-established, with some very large and influential voluntaryorganisations as well as many smaller bodies. Some argue that community action is part of voluntary action, and some voluntary organisations have for many yearsadopted a community development approach to their work.Beyond defining terms, the literature identifies two main issues in debates about participation:•Whether participation is, or should be, an end or a means•The question of power.Ends or meansThere is a key distinction between participation as a method for improving the efficiency and effectiveness of projects by using the resources of local people, and participation as a part (at least) of the purpose of the project (Oakley 1991). This has been described as a distinction between instrumental and transformative (or developmental) participation (Nelson and Wright 1995).The literature suggests that unless participation is explicitly part of the overall purpose of the project - an end as well as a means - the initiative is unlikely to be sustainable. PowerArnstein's ladder of participation recognised in 1969 that power is a key issue in participation. The ladder remains a useful analysis of power relations in participation (Arnstein 1969; Hart 1994). It consists of eight levels:Level 1 Level 2ManipulationEducationThese levels assume apassive community,given informationwhich may be partial orinaccurateLevel 3Information People are told what isgoing to happen, ishappening or hashappenedLevel 4Consultation People are given avoice, but no power toensure their views areheededLevel 5Involvement People's views havesome influence, buttraditional powerholders still make thedecisionsLevel 6Partnership People can begin tonegotiate withtraditional powerholders, includingagreeing roles,responsibilities andlevels of controlLevel 7Delegated power Some power isdelegatedLevel 8Citizen control Full delegation of alldecision-making andactionParticipation can be defined as encompassing everything from Level 4 (consultation), depending on how it is done, to Level 8 (citizen control).Oakley's more recent analysis suggests three broad levels of power and control related to participation (Oakley 1991, 6):•Participation as contribution. At this level, control and direction are not passed to local people; they are just asked to contribute resources.•Participation as organisation. The creation and/or the development of organisations and institutions is an important element in participation. Formalorganisations (such as trusts) may result from a participatory process, as well asinformal groupings. There is a distinction between organisations externallyconceived and introduced, and organisations which emerge and take structure as a result of the process of participation. However, in both cases, the development of a new (or changed) organisation will involve some delegation of power and control.•Participation as empowerment. At this level, the relationship between power and participation is made explicit: participation is developmental and power andcontrol are devolved. There is debate about the notion of empowerment. Some see empowerment as the development of skills and abilities to enable people to manage better, or negotiate better for services. Others see it as enabling people to decideupon and take the actions they believe are essential to their development.Oakley stresses that the first of these types of participation (contribution) is fundamentally different from the other two: both organisation and empowerment involve a transfer of control (Oakley 1991).There is much debate in the literature about power: whether it is 'power to' or 'power over'; the differences between power which is coercive and power which works through covertly creating contexts within which all overt power is exercised; whether power should be envisaged as finite, like a cake (so the more you have, the less I have); whether power should be envisaged as a flow, so we all have it, and just manipulate and collect it differently; how power is exercised through aesthetic choices which confer status (Bourdieu 1986). It can also be argued that power grows by being shared: the more people who share power, the more power there is.Overall, the literature suggests that, to be effective, participatory initiatives must include a sharing of power: "Participation implies a more active form of public involvement, where decisions are taken jointly between the community and decision-makers. It requires decision-makers to be willing to share their power and responsibility" (Bell 1995).Almost all the benefits of participation only accrue when people involved feel they have some say in the decision: some level of ownership of solutions is essential to sustainability. Without this sense of agency (being able to influence things and make changes), people soon lose interest and trust in the process.3.WHO PARTICIPATES?CommunityThere is still much stress on 'community' as the key focus for participation, but there is also more recognition that this is not the only way of defining who participates. The concept of community is confusing because it relates to place as well as people, and can also be applied to all sorts of collectivities not related to place at all (eg Muslim communities, the gay community).The literature on community in relation to environmental management suggests that definitions of community only begin to have relevance when the links between community and place are recognised:•"Concern for familiar topography, for the places one knows, is not about the loss of a commodity, but about the loss of identity. People belong in the world: it gives them a home. The attachment to place - not just natural places, but urban places too - is one of the most fundamental of human needs ... The important thing about places, ofcourse, is that they are shared. Each person's home area is also other people's. The sense of place is therefore tied to the idea of 'community'" (Jacobs 1995, 20).•"'Community' is that web of personal relationships, group networks, traditions and patterns of behaviour that develops against the backdrop of the physicalneighbourhood and its socio-economic situation. Community development aims toenrich that web and make its threads stronger, to develop self confidence and skills, so that the community (the people) can begin to make significant improvements totheir neighbourhood (the place and its material environment)" (Flecknoe & McLellan 1994, 8).Community is usually understood as being to do with "locality", with "actual social groups", with "a particular quality of relationship" which is "felt to be more immediate than society", and when used in conjunction with other activities, such as 'community politics', is "distinct not only from national politics but from formal local politics and normally involves various kinds of direct action and direct local organisations, 'working directly with people', as which it is distinct from 'service to the community'" (Williams 1988).However, the idea of community is easily over-romanticised and, as Taylor points out, "Communities ... can be scene of conflict and exclusion as well as togetherness, and many of the stresses of modern life work against a community 'spirit'" (Taylor 1992, 2). Community does not mean consensus. Living in the same place does not guarantee a common view about local issues.Geographically defined communities are convenient for agencies who want to be able to draw lines on a map and develop participation within those boundaries. Where those geographical boundaries exist (such as district council or parish council boundaries) they may be appropriate in certain circumstances. However, these sorts of externally defined boundaries should not be regarded as immutable.Community is more than just a place on a map: "Despite easy cynicism, 'community' is more than an empty rhetoric-word. And it represents more than nostalgia too for a bygone age of monolithic classes and localities. Community is the recognition that people are not just individuals, that there is such a thing as society to which we belong, which makes us who we are, and without which there can be no true human flourishing" (Jacobs 1995, 20-21). Community can therefore be seen almost as an aspiration as much as a place, and as a collection of certain sorts of relationships which are related to place but not defined by the physical place.In many participatory initiatives, the debate has gone beyond the 'what is community' issue, concluding that defining 'community' is less important than identifying who are the people affected by the decisions under debate: stakeholders is often the preferred term, signifying a practical personal interest.Nevertheless, it is generally accepted that the community (in terms of the people who live and work in a particular location) will still be the most important group to be involved in any initiative focused on a specific place. They are the people who will have to live with the consequences of whatever happens; others may care about it but their lives are less likely to be affected by the ultimate decision.Other interestsAlongside local people, other groups have been identified in the literature as having a stake in decisions about countryside or environmental management including visitors and users, sociations, viewers, the common or public interest, professionals, disadvantaged groups and volunteers.All these groups go beyond the obvious stakeholders in any local area, but all care and all would be affected in different ways by changes to specific places. Recognition of this wider constituency will require the development of a wider range of participatory mechanisms than has been the norm in the past. The possible interests of each of these groups is outlined below.Visitors and usersPeople may not live in an area of countryside, but may have a strong commitment to it and concern about it because they regularly use it for a range of purposes. These purposes may be economically based or for leisure: dog walkers who are known to have fought to preserve and then managed woodlands (Warburton 1995); or people who have traditionally collected produce from areas (from coal on beaches to fruit from hedgerows).'Sociations'Other groups also visit and use the countryside for leisure purposes, and will often vehemently defend their access and their activities.'Sociations' is a term which refers to the networks created by individuals involved in specific areas of interest or activity, such as cyclists, rock climbers, walkers etc (Clark et al 1994). These groups develop a mutuality and collective action around what could be called 'hobbies', although that term goes nowhere near expressing the commitment and identification people feel within these groups (Hoggett and Bishop 1986). These groupings may be maintained through regular publications, organisational structures and occasional events.It is suggested that people are using these links to create new forms of social identity through sharing their commitment to these activities, and that this lies behind the strong feelings aroused by threats to their access to the places they use for their activities -especially the countryside (Clark et al 1994): "the individual is creating his or her sense of self through a series of consciously adopted commitments - manifested in consumption patterns ... and in chosen affiliations with other individuals reflecting particular aspects of his or her patterns of moral or practical concern" (Clark et al 1994, 31), including, particularly, leisure activities.Clark et al argue that "people are now moving in their everyday behaviours towards new forms of social identity, linking themselves in fresh ways with other people sharing, and perhaps giving concrete form to, their commitments" (Clark et al 1994, 32). These links can result in people's attachment to their activities (such as climbing or nature conservation) being deeper and more complex than expected, which may explain why conflicts become so heated: a threat to the activity becomes a threat to personal identity.ViewersLandlife (Liverpool) has argued that by planting fields of sunflowers which can be seen from the tower blocks in inner city Liverpool, an improvement has been made to the lives of the people living there. Landlife's research (unpublished) with the residents of the block has shown the truth of this, even when only a few of the residents (although there are some) have any practical participation in planting, looking after and harvesting the crop: the seeds from the sunflowers are collected and sold to raise funds for the overall scheme. It connects people with the land, and it makes their lives more beautiful.。