THE MICROSIMULATION UNIT Poverty in Britain the impact of

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:175.51 KB

- 文档页数:17

如何解决贫困英语作文Poverty is a complex and multifaceted issue that affects millions of people around the world. Addressing it requires a comprehensive approach that includes economic, social, and educational strategies. Here's how we can tackle the problem of poverty:1. Economic Empowerment: Encourage entrepreneurship and small business development to create jobs and stimulate the local economy. Providing microloans and financial literacy training can help individuals start their own businesses.2. Educational Opportunities: Education is a powerful tool to break the cycle of poverty. Ensuring access to quality education for all, regardless of their economic background,is crucial. This includes investing in schools, teachers, and educational materials.3. Social Welfare Programs: Implement social welfare programs that provide a safety net for the most vulnerable. This can include unemployment benefits, food assistance, and healthcare services.4. Skill Development: Offer vocational training and skill development programs to help individuals acquire the skills needed for employment in various sectors.5. Community Involvement: Engage communities in the fightagainst poverty by involving them in decision-making processes and ensuring that their voices are heard.6. Policy Reform: Advocate for policies that reduce income inequality and promote fair wages, labor rights, and social justice.7. Healthcare Access: Improve access to healthcare services, particularly in rural and impoverished areas, to prevent and treat diseases that can exacerbate poverty.8. Infrastructure Development: Invest in infrastructure such as roads, water supply, and sanitation to improve living conditions and create opportunities for economic growth.9. International Aid and Cooperation: Foster international partnerships and aid to support countries and communities in need, particularly in times of crisis.10. Sustainable Development: Promote sustainable development practices that protect the environment while also providing economic benefits to communities.By combining these strategies, we can work towards a world where poverty is a thing of the past, and everyone has the opportunity to live a fulfilling and prosperous life.。

中国特色消除贫困英文演讲Poverty alleviation has been one of the top prioritiesof the Chinese government for decades. With the successful implementation of various poverty alleviation policies, China has achieved remarkable results in reducing the poverty rate. The Chinese-style poverty alleviation model has been highly recognized internationally, earning China a reputation as a frontline fighter against poverty.Step 1: Identification and TargetingThe Chinese-style poverty alleviation model begins with identification and targeting of poor households. In this step, the government deploys professionals who use various methodsto identify and target households living below the poverty line. Through investigation, different factors like lack of education and job opportunities, lack of basic infrastructure, and diseases are recognized as hindrances to poverty reduction.Step 2: Tailored AssistanceOnce households are identified, the government provides them with tailored assistance based on their specific needs. Through a combination of cash transfers, subsidies, andtraining programs, the government helps poor householdsacquire sustainable abilities to improve their livelihoods. The assistance also focuses on the development of industries relevant to the area to boost job creation.Step 3: Relocation and Housing SupportRelocation and housing support are two critical components of the Chinese-style poverty alleviation model.For households living in remote regions with difficulty accessing basic infrastructure, the government constructs new villages with better infrastructure, electricity and water supply, and housing support, which improve their quality of life. Housing support has also been critical in many cases when people move from unsafe and risky areas as part of poverty relief efforts.Step 4: Micro-Credit LoansAccess to credit has been fundamental to poverty reduction goals. As part of the Chinese-style poverty alleviation model, micro-credit loans have been introduced to provide small business owners with capital that will ultimately help them grow their businesses. These loans have increased productivity, income, and access to markets forlow-income households, helping them to lift themselves out of poverty.Step 5: Holistic ApproachThe Chinese-style poverty alleviation model takes a holistic approach to poverty reduction, addressing multiple aspects of poverty simultaneously. The model emphasizes education, health, infrastructure, employment, and cultural development. It applies a systemic approach that tackles the root cause of poverty, instead of focusing only on its symptoms. It seeks to transform people's ability to earn, to secure their basic needs, and to participate in the country's development.ConclusionThe Chinese-style poverty alleviation model exemplifies the country's commitment to ensuring the well-being of its citizens. It demonstrates a coordinated effort between multiple sectors, including government, private sector, civilsociety, and communities. The impressive results and efficiency of the model have opened up possibilities for future global cooperation in poverty alleviation efforts. In conclusion, poverty reduction requires coordinated efforts from international communities, governments, and private sectors. The Chinese-style poverty alleviation model offers valuable lessons to policymakers worldwide to effectively combat poverty.。

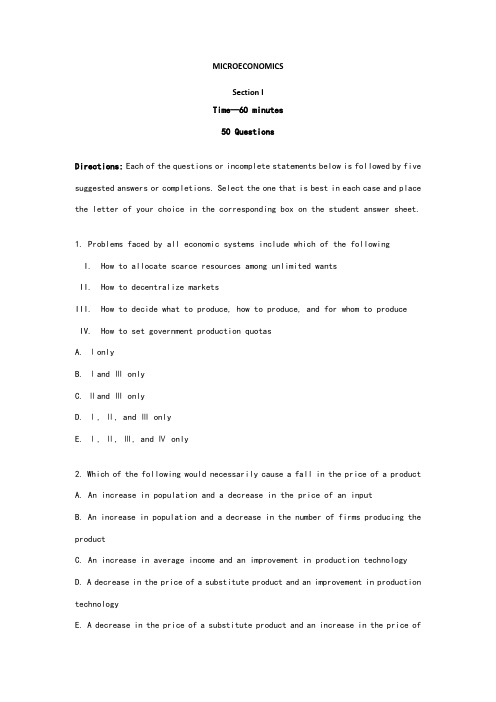

MICROECONOMICSSection ITime—60 minutes50 QuestionsDirections: Each of the questions or incomplete statements below is followed by five suggested answers or completions. Select the one that is best in each case and place the letter of your choice in the corresponding box on the student answer sheet.1. Problems faced by all economic systems include which of the followingI.How to allocate scarce resources among unlimited wantsII.How to decentralize marketsIII.How to decide what to produce, how to produce, and for whom to produce IV.How to set government production quotasA. ⅠonlyB. Ⅰand Ⅲ onlyC. Ⅱand Ⅲ onlyD. Ⅰ, Ⅱ, and Ⅲ onlyE. Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, and Ⅳ only2. Which of the following would necessarily cause a fall in the price of a productA. An increase in population and a decrease in the price of an inputB. An increase in population and a decrease in the number of firms producing the productC. An increase in average income and an improvement in production technologyD. A decrease in the price of a substitute product and an improvement in production technologyE. A decrease in the price of a substitute product and an increase in the price ofan input3. The market equilibrium price of home heating oil is $ per gallon. If a price ceiling of $ per gallon is imposed, which of the following will occur in the market for home heating oilI.Quantity supplied will increase.II.Quantity demanded will increase.III.Quantity supplied will decrease.IV.Quantity demanded will decrease.A. ⅡonlyB. Ⅰand Ⅱ onlyC. Ⅰand Ⅳ onlyD. Ⅱ and Ⅲ onlyE. Ⅲ and Ⅳ only4. Suppose that a family buys all its clothing from a discount store and treats these items as inferior goods. Under such circumstances, this family’s consumption of discount store clothing will necessarilyA. increase when a family member wins the state lotteryB. increase when a family member gets a raise in pay at workC. remain unchanged when its income rises or falls due to events beyond the family’s controlD. decrease when a family member becomes unemployedE. decrease when a family member experiences an increase in income5. Which of the following describes what will happen to market price and quantity if firms in a perfectly competitive market form a cartel and act as aprofit-maximizing monopolyPrice QuantityA. Decrease DecreaseB. Decrease IncreaseC. Increase IncreaseD. Increase DecreaseE. Increase No change6. Quantity Produced Total Cost0 $51 172 283 414 615 91Barney’s Bait Company can sell all the lures it produces at the market price of $14. On the basis of the cost information in the table above, how many lures should the bait company makeA. 1B. 2C. 3D. 4E. 57. A natural monopoly occurs in an industry ifA. economies of scale allow at most one firm of efficient size to exist in that marketB. a single firm has control over a scarce and essential resourceC. a single firm produces inputs for use by other firmsD. a single firm has the technology to produce the product sold in that marketE. above-normal profits persist in the industry8. The typical firm in a monopolistically competitive industry earns zero profit in long-run equilibrium becauseA. advertising costs make monopolistic competition a high-cost market structure rather than a low-cost market structureB. the firms in the industry do not operate at the minimum point on their long-run average cost curvesC. there are no restrictions on entering or exiting from the industryD. the firms in the industry are unable to engage in product differentiationE. there are close substitutes for each firm’s product9. Which of the following inevitably causes a shift in the market demand for workers with a certain skillA. An increase in the demand for goods produced by these workersB. A decrease in tax rates on the income of these workersC. An increase in the equilibrium wages received by these workersD. An increase in the supply of these workersE. The creation of a federally subsidized program to train new workers10. If hiring an additional worker would increase a firm’s total cost by less than it would increase its total revenue, the firm shouldA. not hire the workerB. hire the workerC. hire the worker only if another worker leaves or is hiredD. hire the worker only if the worker can raise the firm’s productivityE. reduce the number of workers employed by the firm11. If a firm wants to produce a given amount of output at the lowest possible cost, it should use each resource in such a manner thatA. it uses more of the less expensive resourceB. it uses more of the resource with the highest marginal productC. each resource has just reached the point of diminishing marginal returnsD. the marginal products of each resource are equalE. the marginal products per dollar spent on each resource are equal12. In which of the following ways does the United States government currently intervene in the working of the market economyI.It produces certain goods and services.II.It regulated the private sector to achieve a more efficient allocation of resources.III.It redistributes income through taxation and public expenditures.A. ⅠonlyB. Ⅱ onlyC. Ⅲ onlyD. Ⅱ and Ⅲ onlyE. Ⅰ, Ⅱ, an d Ⅲ13. If it were possible to increase the output of military goods and simultaneously to increase the output of the private sector of an economy, which of the following statements about the economy and its current position relative to its production possibilities curve would be trueA. The economy is inefficient and inside the curve.B. The economy is inefficient and on the curve.C. The economy is efficient and on the curve.D. The economy is efficient and inside the curve.E. The economy is efficient and outside the curve.14. An effective price floor introduced in the market for rice will result inA. a decrease in the price of rice and an increase in the quantity of rice soldB. a decrease in the price of rice and a decrease in the quantity of rice soldC. a decrease in the price of rice and an excess demand for riceD. an increase in the price of rice and an excess supply of riceE. an increase in the price of rice and an excess demand for rice15. Marginal revenue is the change in revenue that results from a one-unit increase in theA. variable inputB. variable input priceC. output levelD. output priceE. fixed cost16. A leftward shift in the supply curve of corn would result fromA. a decrease in the price of cornB. a decrease in the price of farm machineryC. an increase in the demand for corn breadD. an increase in the labor costs of producing cornE. an increase in consumers’ incomes17. The diagram above depicts costs and revenue curves for a firm. What are the firm’s profit -maximizing output and priceOutput PriceA. 0S 0DB. 0R 0EC. 0Q 0FD. 0Q 0BE. 0P 0G18. The government is considering imposing a 3 percent tax on either good A or goodB. In order to generate the largest revenue, the tax should be imposed on the good for whichA. demand is perfectly elasticB. demand is perfectly inelasticC. demand is unit elasticD. supply is perfectly elasticE. supply is unit elasticDemandMargina MarginaAverage Total K J I H P Q R SGFEDCB A NLM 019. Which of the following statements has to be true in a perfectly competitive marketA. A firm’s marginal revenue equals price.B. A firm’s average total cost is above price in the long run.C. A firm’s average fixed cost rises in the short run.D. A firm’s average variable cost is higher than price in the long run.E. Large firms have lower costs than small firms.20. Assume that an electric power company owns two plants and that, on a particular day, 10,000 kilowatts of electricity are demanded by the public. In order to minimize the total cost of providing the 10,000 kilowatts, the company should allocate production so thatA. marginal costs are the same for both plantsB. average total costs are the same for both plantsC. total variable costs are the same for both plantsD. the sum of total variable cost and total fixed cost is the same for both plantsE. only the plant with the lower average cost is used to produce the 10,000 kilowatts of electricity21. Suppose that the consumption of a certain product results in benefits to others besides the consumers of the product. Which of the following statements is most likely to be trueA. The demand for the product is price inelastic.B. A perfectly competitive industry will not produce the optimal quantity of the product.C. A perfectly competitive industry will not produce the product.D. Optimality requires that consumers of this product be taxed.E. Producers of this product earn an economic profit.Questions 22-23 are based on the table below, which lists the total output of workers in Greta’s Jack et Shop.22. Which of the following is the marginal product of the fourth workerA. 4B. 5C. 6D. 28E. 11223. Greta already employs 3 workers. If the price of jackets is $5 and the wage rate is $25, she shouldA. go out of business altogetherB. lay off the third workerC. keep the third worker but not employ more workersD. hire two more workersE. hire one more workers24. A city council is deciding what price to set for a trip on the city’s co mmuter train line. If the council wants to maximize profits, it will set a price so thatA. price equals marginal costB. price equals average costC. price equals marginal revenueD. marginal revenue equals marginal costE. marginal revenue equals average total cost25. The demand curve for cars is downward sloping because an increase in the price of cars leads toA. the increased use of other modes of transportationB. a fall in the expected future price of carsC. a decrease in the number of cars available for purchaseD. a rise in the prices of gasoline and other oil-based productsE. a change in consumers’ tastes in cars26. Which of the following best explains the shape of the production possibilities curve for the two-commodity economy shown aboveA. The opportunity cost of procuring an additional unit of each commodity stays the same as production of the commodity expands.B. The opportunity cost of producing an additional unit of each commodity decreases as production of the commodity expands.C. The opportunity cost of producing an additional unit of each commodity increases as production of the commodity expands.D. The quantity demanded of each commodity decreases as consumption of the commodity 0 QUANTITY OF COMMODITY 2 Q U A N T I T Y O F C O M M O D I T Y 1increases.E. The quantity demanded of each commodity increases as the production of the commodity expands.27. In the long run, compared with a perfectly competitive firm, a monopolistically competitive firm with the same costs will haveA. a higher price and higher outputB. a higher price and lower outputC. a lower price and higher outputD. a lower price and lower outputE. the same price and lower output28. Assume that products X and Y are substitutes. If the cost of producing X decreases and the price of Y increases, which of the following will occur to the equilibrium price and quantity of XPrice of X Quantity of XA. Increase IncreaseB. Increase DecreaseC. Increase Increase or decreaseD. Increase or decrease IncreaseE. Decrease Decrease29. Suppose that an effective minimum wage is imposed in a certain labor market above the equilibrium wages. If labor supply in that market subsequently increases, which of the following will occurA. Unemployment in that market will increase.B. Quantity of labor supplied will decrease.C. Quantity of labor demanded will increase.D. Market demand will increase.E. The market wage will increase.30. Imperfectly competitive firms may be allocatively inefficient because they produce at a level of output such thatA. average cost is at a minimumB. price equals marginal revenueC. marginal revenue is greater than marginal costD. price equals marginal costE. price is greater than marginal costQuestions 31-33 are based on the table below, which shows a firm’s total cost for different levels of output.31. Which of the following is the firm’s marginal cost of producing the fourth unit of outputA. $B. $C. $D. $E. $32. Which of the following is the firm’s average total cost of producing 3 units of outputA. $B. $C. $D. $E. $33. Which of the following is the firm’s average fixed cost of producing 2 units of outputA. $B. $C. $D. $E. $34. In the short run, if the product price of a perfectly competitive firm is less than the minimum average variable cost, the firm willA. raise its priceB. increase its outputC. decrease its output slightly but increase its profit marginD. lose money by continuing to produce than by shutting downE. lose less by continuing to produce than by shutting down35. Which of the following statements is true of perfectly competitive firms inlong-run equilibriumA. Firm revenues will decrease if production is increased.B. Total firm revenues are at a maximum.C. Average fixed cost equals marginal cost.D. Average total cost s at a minimum.E. Average variable cost is greater than marginal cost.36. Assume that both input and product markets are competitive. If the product price rises, in the short run firms will increase production by increasingA. the stock of fixed capital until marginal revenue equals the product priceB. the stock of fixed capital until the average product of capital equals the price of capitalC. labor input until the marginal revenue product of labor equals the wage rateD. labor input until the marginal product of labor equals the wage rateE. labor input until the ratio of product price to the marginal product of labor equals the wage rate37. Half of the inhabitants of an island oppose building a new bridge to the mainland, since they say it will destroy the island’s quaint atmosphere. The economic concept that is most relevant to the decision of whether or not to build the bridge isA. externalitiesB. natural monopolyC. economic rentD. imperfect competitionE. perfect competition38. Which of the following best states the thesis of the law of comparative advantageA. Differences in relative costs of production are the key to determining patternsof trade.B. Difference in absolute costs of production determine which goods should be traded between nations.C. Tariffs and quotas are beneficial in increasing international competitiveness.D. Nations should not specialize in the production of goods and services.E. Two nations will not trade if one is more efficient than the other in the production of all goods.39. A student who attends college would pay $10,000 annually for tuition, books, and fees. If the student’s next best alternative is to work an d earn $15,000 a year, the opportunity cost of a year in college would be equal toA. zero, since the lost opportunity to earn income is offset by the opportunity to attend collegeB. $5,000, representing the difference between forgone income and college costsC. $10,000, since opportunity costs include only actual cash outlaysD. $15,000, representing forgone income, since the costs of tuition, books, and fees will be more than offset by additional income earned after graduationE. $25,000, representing the sum of tuition, books, fees and forgone income.40. If an increase in the price of good X causes a drop in demand for good Y, good Y isA. an inferior goodB. a luxury goodC. a necessary goodD. a substitute for good XE. a complement to good X41. An improvement in production technology for a certain good leads toA. an increase in demand for the goodB. an increase in the supply of the goodC. an increase in the price of the goodD. a shortage of the goodE. a surplus of the good42. A firm doubles all of its inputs and finds that it has more than doubled its output. This situation is an example ofA. increasing marginal returnsB. diminishing marginal returnsC. constant returns to scaleD. increasing returns to scaleE. decreasing returns to scale43. Reducing the tariff on Canadian beer sold in the United States will most likely have which of the following effects on the market for beer produced and sold in the United StatesA. The quantity of United States beer purchased will increase.B. Total expenditure on United Stats beer will increase.C. The supply of United States beer will increase.D. The price of United States beer will decrease.E. More workers will be employed in the production of United States beer.44. Suppose that the license paid by each business to operate in a city increases from $400 per year to $500 per year. What effect will this increase have on a firm’s short-run costsMarginal Cost Average Total Cost Average Variable CostA. Increase Increase IncreaseB. Increase Increase No effectC. No effect No effect No effectD. No effect Increase IncreaseE. No effect Increase No effect45. In a perfectly competitive market, an individual farmer intending to increase her revenue decides to increase the price of her crop by 20 percent. As a result her total revenue willA. decreaseB. stay the sameC. increase by less than 20 percentD. increase by 20 percentE. increase by more than 20 percent46. If the supply of a factor of production is fixed, which of the following will be true of its priceA. Supply is irrelevant to the determination of factor price.B. A positive factor price cannot be justified on economic grounds.C. Factor price will be determined by the demand for the fixed amount of the factor.D. Factor price will not be determined by supply and demand analysis.E. Factor price will be zero, since no payment is necessary to secure the services of the factor.47. Which of the following is true if a perfectly competitive industry is earning zero economic profits in the long runA. The level of investment in long-run equilibrium is greater than the efficient level.B. Relatively few firms are able to survive the competitive pressures in the longrun.C. Some firms will be forced to transfer their resources to more lucrative uses.D. The resources invested in this industry are earning at least as high a return as the would in any alternative use.E. Firms will exit until economic profits become positive.48. The figure above shows cost and revenue curves for public regulated power company and three possible prices for its output. Which of the following statements about those prices is most accurateA. If P1 were approved, regulation would not be needed and the company would have every incentive to lower rates to P2B. P1 is inefficient; it is better to have several utilities serve the area than to approve P1C. P2 is ideal; it gives stockholders the maximum rate of return and protects consumers from exploitation.D. P3 would maximize consumer welfare; greater electric use at this low rate would guarantee stockholders a fair rate of return.MarginaAverage TotalMarginal Cost DemandQuantitPriceP 1P 2 P 3E. P3 would maximize consumer welfare, but a public subsidy would be needed to keep company in business.49. NOT SCORED*50. In a market economy, public goods such as community police protection are unlikely to be provided in sufficient quantity by the private sector becauseA. private firms are less efficient at producing public goods than is the governmentB. the use of public goods cannot be withheld from those who do not pay for themC. consumers lack information about the benefits of public goodsD. consumers do not value public goods highly enough for firms to produce them profitablyE. public goods are inherently too important to be left to private firms to produce * This question was not scored. Therefore, the maximum number of multiple-choice questions that candidates could answer correctly was 49.。

探讨贫困的根源的英语作文Poverty, a multifaceted and persistent global issue, has been a subject of extensive研究 and analysis. Itsroots are deeply intertwined with a myriad of societal, economic, and political factors, creating a complex webthat perpetuates this debilitating condition. Understanding the fundamental causes of poverty is crucial for developing effective strategies to alleviate its detrimental effects.One of the primary drivers of poverty is lack of access to education. Education empowers individuals with the knowledge, skills, and critical thinking abilities necessary for economic advancement. Without adequate education, people are often relegated to low-paying, insecure jobs, perpetuating a cycle of poverty. In many impoverished regions, educational institutions are underfunded and lack the resources to provide quality instruction, further exacerbating the problem.Economic inequality is another major root of poverty.When wealth is concentrated in the hands of a small elite, the vast majority of the population is left with limited opportunities for economic growth. This inequality can be driven by factors such as unfair labor practices, corporate monopolies, and regressive tax policies. Furthermore, economic downturns and financial crises disproportionately impact low-income households, pushing them deeper into poverty.Political instability and conflict are also significant contributors to poverty. War and violence disrupt livelihoods, destroy infrastructure, and displace populations. In conflict-ridden areas, individuals are often forced to flee their homes, losing their possessions and access to essential services. Prolonged conflicts can also lead to economic collapse and a breakdown of social structures, further exacerbating poverty.Environmental degradation poses another threat to poverty reduction. Climate change, deforestation, and pollution disproportionately affect impoverished communities. These environmental challenges can disruptagricultural production, reduce access to clean water and sanitation, and increase health risks for the poor. Additionally, environmental disasters, such as floods, droughts, and hurricanes, can destroy homes and livelihoods, pushing families into poverty.Social and cultural factors also play a role in perpetuating poverty. Discrimination based on gender, race, ethnicity, or religion can limit access to education, employment, and other opportunities. Cultural norms and practices that reinforce inequality, such as early marriage or restrictions on women's property rights, can also contribute to poverty. Moreover, social isolation and lackof support networks can make it difficult for individualsto escape poverty.Addressing the root causes of poverty requires a comprehensive approach that tackles both its economic and social dimensions. Governments and international organizations have a vital role to play in implementing policies that promote economic growth, reduce inequality, and ensure access to quality education and healthcare forall. Additionally, investing in conflict prevention and resolution, promoting environmental sustainability, and addressing social and cultural barriers to opportunity are essential components of a sustainable solution to poverty.Education is a cornerstone of poverty reduction strategies. By investing in early childhood education, improving the quality of primary and secondary education, and expanding access to higher education, governments can equip individuals with the tools they need to break the cycle of poverty. Education empowers people to secure better-paying jobs, start businesses, and contribute to their communities' economic development.Economic policies that promote inclusive growth and reduce inequality are also crucial. Governments should implement progressive tax policies that shift the tax burden away from low-income earners, invest in infrastructure and public services that benefit the poor, and support small businesses and entrepreneurship. Additionally, labor market regulations should protect workers' rights, ensure fair wages, and promote equalopportunities for all.Addressing conflict and political instability is essential for creating an environment conducive to poverty reduction. International cooperation and diplomacy can play a critical role in resolving conflicts, promoting peace, and fostering economic development in war-torn regions. Additionally, governments should allocate resources topost-conflict reconstruction and reconciliation efforts, helping communities rebuild their lives and livelihoods.Mitigating environmental degradation is another important aspect of tackling poverty. By investing in sustainable agriculture, promoting renewable energy, and reducing pollution, governments can protect natural resources and improve the livelihoods of those who depend on them. Additionally, disaster preparedness and response mechanisms should be strengthened to minimize the impact of environmental disasters on vulnerable communities.Finally, addressing social and cultural barriers to opportunity is essential for a comprehensive approach topoverty reduction. Governments and civil society organizations should work together to combat discrimination, promote gender equality, and empower marginalized groups. Investing in social safety nets, such as food assistance programs, healthcare, and housing subsidies, can provide a lifeline for those who are struggling.The eradication of poverty is a complex challenge that requires a multifaceted and sustained response. By addressing the root causes of poverty, including lack of education, economic inequality, political instability, environmental degradation, and social and cultural barriers, we can create a more equitable and just society for all.。

精准扶贫英文作文150字Precision poverty alleviation is a comprehensive approach that aims to address the root causes of poverty and provide targeted support to those in need. This strategy has gained significant attention in recent years, particularly in developing countries, as a means to achieve sustainable and equitable economic growth. The core principle of precision poverty alleviation is to identify the specific needs and challenges faced by individual households or communities, and then tailor interventions to address those unique circumstances.One of the key advantages of this approach is its ability to maximize the impact of limited resources. By focusing on the specific needs of the poorest and most vulnerable, policymakers and development organizations can ensure that their efforts are directed towards the areas where they will have the greatest effect. This is in contrast to more broad-based poverty reduction programs, which may miss the nuances of individual situations and fail to reach those who are most in need.Another important aspect of precision poverty alleviation is itsemphasis on data-driven decision-making. Through the use of advanced data collection and analysis techniques, such as household surveys, satellite imagery, and geographic information systems, governments and development agencies can gain a detailed understanding of the local context and the specific challenges faced by different communities. This information can then be used to design and implement targeted interventions that are tailored to the unique needs of each community.One of the most widely recognized examples of precision poverty alleviation is the case of China's Targeted Poverty Alleviation (TPA) program. Launched in 2015, the TPA program aimed to lift the remaining 70 million people living in poverty out of their dire circumstances by 2020. The program adopted a comprehensive approach that combined financial assistance, skills training, infrastructure development, and social services to address the multidimensional nature of poverty.At the heart of the TPA program was a detailed database of households living in poverty, which was compiled through extensive household surveys and data collection efforts. This information allowed policymakers to identify the specific needs and challenges faced by each household, and then design interventions that addressed those needs. For example, some households might have received financial assistance to start a small business, while othersmight have received support for agricultural development or access to healthcare services.The results of the TPA program have been impressive. By the end of 2020, China had lifted the remaining 70 million people out of poverty, achieving its goal of eliminating extreme poverty. This success can be attributed in large part to the precision and targeted nature of the interventions, which ensured that resources were directed towards those who needed them the most.However, the implementation of precision poverty alleviation is not without its challenges. One of the key challenges is the need for robust data collection and analysis capabilities, which can be resource-intensive and require significant investment in technology and human resources. Additionally, there are concerns about the potential for exclusion or marginalization of certain groups, if the targeting of interventions is not done carefully and with a strong focus on equity.Despite these challenges, the potential benefits of precision poverty alleviation are significant. By tailoring interventions to the specific needs of individual households or communities, policymakers and development organizations can achieve greater impact and ensure that their efforts are truly reaching those who are most in need. Moreover, the data-driven approach of precision poverty alleviationcan also help to improve the overall effectiveness and efficiency of poverty reduction efforts, by allowing for more informed decision-making and more effective monitoring and evaluation.In conclusion, precision poverty alleviation is a promising approach that has the potential to transform the way we address poverty and inequality. By focusing on the unique needs and challenges faced by individual households and communities, this strategy can help to ensure that limited resources are directed towards the areas where they will have the greatest impact. As more countries and development organizations adopt this approach, it will be important to continue to learn from successes and address the challenges that arise, in order to build a more equitable and sustainable future for all.。

扶贫中的困难英语作文English: One of the main difficulties in poverty alleviation is the lack of sustainable solutions. While immediate aid such as food donations and financial assistance can provide temporary relief, long-term solutions are needed to address the root causes of poverty. This includes improving education and healthcare resources, creating job opportunities, and promoting sustainable agricultural practices. Another challenge is the complexity of poverty itself, as it is often interconnected with factors such as lack of access to basic services, social inequality, and environmental degradation. Addressing poverty requires a comprehensive and multifaceted approach that tackles these underlying issues. Additionally, limited resources, corruption, and political instability can hinder poverty alleviation efforts, making it difficult to achieve meaningful and lasting results. Collaboration between governments, NGOs, and the private sector is crucial in overcoming these challenges and creating sustainable change in impoverished communities.中文翻译: 扶贫中的一个主要困难是缺乏可持续的解决方案。

贫困对人体的影响英语作文Poverty and Its Impact on Human Health。

Poverty is a global issue that affects millions of people around the world. Poverty is defined as a lack of resources, including financial, physical, and social resources, that are necessary for a person to live ahealthy and fulfilling life. Poverty is a complex issuethat has a significant impact on human health. In this essay, we will explore the impact of poverty on humanhealth and discuss some of the strategies that can be usedto address this issue.One of the most significant impacts of poverty on human health is malnutrition. Poverty often leads to a lack of access to healthy and nutritious food, which can result in malnutrition. Malnutrition can cause a range of health problems, including stunted growth, weakened immune systems, and an increased risk of disease. Children who are malnourished are also more likely to experiencedevelopmental delays and have lower cognitive abilities.Poverty also has a significant impact on mental health. People living in poverty are more likely to experience stress, anxiety, and depression. This is due to a range of factors, including financial stress, social isolation, anda lack of access to healthcare. The stress of poverty can also lead to an increased risk of substance abuse and addiction.In addition to malnutrition and mental health issues, poverty can also lead to a range of physical health problems. People living in poverty are more likely to experience chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. This is due to a range of factors, including a lack of access to healthcare, unhealthy living conditions, and a lack of physical activity.Addressing poverty and its impact on human health requires a multifaceted approach. One strategy is to increase access to healthcare and nutrition programs. This can include expanding Medicaid and other healthcareprograms for low-income individuals and families. It can also include increasing funding for food assistance programs such as SNAP and WIC.Another strategy is to address the root causes of poverty. This can include increasing access to education and job training programs, as well as increasing the minimum wage. It can also include investing in affordable housing and transportation, which can help to reduce the cost of living for low-income individuals and families.In conclusion, poverty has a significant impact on human health. It can lead to malnutrition, mental health issues, and a range of physical health problems. Addressing poverty and its impact on human health requires a multifaceted approach that includes increasing access to healthcare and nutrition programs, as well as addressing the root causes of poverty. By working together, we can reduce the impact of poverty on human health and create a healthier and more equitable society.。

有关扶贫的英文作文高中Poverty Alleviation: A Global Challenge and Shared ResponsibilityPoverty is a complex and multifaceted issue that has plagued societies across the globe for centuries. It is a scourge that not only deprives individuals of their basic necessities but also hinders the overall progress and development of communities and nations. In recent years, the international community has placed a renewed emphasis on the importance of poverty alleviation, recognizing it as a crucial step towards achieving sustainable and equitable development.At the heart of this global effort is the recognition that poverty is not just an economic problem, but a comprehensive challenge that encompasses social, political, and environmental factors. Addressing poverty requires a holistic approach that tackles the root causes and provides comprehensive solutions tailored to the unique needs of different regions and communities.One of the key pillars of poverty alleviation is the provision of accessto basic services, such as healthcare, education, and clean water. By ensuring that all individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic status, have access to these fundamental necessities, we can empower them to break the cycle of poverty and build a better future for themselves and their communities.In this regard, the role of governments and policymakers cannot be overstated. Governments must prioritize the allocation of resources towards social welfare programs, infrastructure development, and the creation of employment opportunities. This not only directly benefits those living in poverty but also fosters an environment that promotes economic growth and social mobility.Moreover, the private sector has a crucial part to play in the fight against poverty. Businesses can contribute by adopting ethical and socially responsible practices, investing in community development initiatives, and providing opportunities for skills training and job creation. By aligning their corporate goals with the broader objectives of poverty alleviation, businesses can create a positive impact and contribute to the overall well-being of the communities in which they operate.Another key aspect of poverty alleviation is the empowerment of marginalized communities and individuals. This involves addressing the underlying social, cultural, and political barriers that perpetuatepoverty, such as gender inequality, discrimination, and lack of access to decision-making processes. By empowering these communities and providing them with the tools and resources they need to advocate for their rights and participate in the development of their communities, we can foster a more inclusive and equitable society.The role of civil society organizations and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in this endeavor cannot be overstated. These entities often serve as the link between the government, the private sector, and the communities they serve, providing essential services, advocating for the rights of the marginalized, and facilitating the implementation of poverty alleviation programs. By working in partnership with these organizations, governments and businesses can leverage their expertise and reach to maximize the impact of their efforts.Furthermore, the importance of international cooperation and global solidarity cannot be overlooked. Poverty is a global challenge that transcends national borders, and addressing it requires a coordinated and collaborative effort among nations, international organizations, and development agencies. Through the sharing of best practices, the mobilization of resources, and the implementation of cross-border initiatives, the international community can amplify the impact of poverty alleviation efforts and ensure that no one is left behind.In conclusion, the fight against poverty is a complex and multifaceted challenge that requires the concerted efforts of governments, the private sector, civil society, and the international community. By adopting a holistic approach that addresses the root causes of poverty and empowers marginalized communities, we can work towards a future where all individuals have access to the basic necessities and the opportunity to thrive. This is not only a moral imperative but also a crucial step towards achieving sustainable and equitable development for all.。

举例贫穷的现象英文作文Title: The Perpetual Cycle of Poverty: A Global Phenomenon。

Poverty is an enduring issue that plagues societies worldwide, transcending geographical boundaries and socioeconomic statuses. It manifests in various forms, perpetuating a cycle of deprivation that entrapsindividuals and communities. Through examining diverse examples of poverty, we gain insights into its multifaceted nature and the urgent need for comprehensive solutions.One prevalent manifestation of poverty is homelessness. In bustling urban centers like New York City or Mumbai, throngs of individuals find themselves without stable shelter, forced to seek refuge in makeshift tents, under bridges, or on the streets. These individuals endure harsh living conditions, lacking access to basic amenities such as clean water, sanitation facilities, and adequate nutrition. The cycle of poverty is starkly evident as manyhomeless individuals struggle to break free from their circumstances due to systemic barriers such as lack of affordable housing, mental health issues, or substance abuse.Moreover, in rural areas across the globe, agricultural poverty persists as a predominant challenge. Smallholder farmers, particularly in developing countries, grapple with meager incomes, limited access to modern farming techniques, and vulnerability to climate change-induced disasters. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, subsistence farmingremains the primary source of livelihood for millions of people, yet erratic weather patterns, soil degradation, and inadequate infrastructure impede agricultural productivity. Consequently, rural communities endure persistent poverty, hindering their prospects for economic advancement.Additionally, educational disparities exacerbate the cycle of poverty, particularly among marginalized populations. In regions where access to quality educationis limited, children from impoverished backgrounds face formidable obstacles in attaining academic success. In manylow-income communities, schools lack essential resources such as textbooks, trained teachers, and proper infrastructure, undermining students' learning outcomes. Consequently, generations are trapped in intergenerational poverty, perpetuating a cycle where limited access to education begets limited opportunities for socioeconomic mobility.Furthermore, the global digital divide exacerbates disparities and perpetuates poverty in both urban and rural settings. While the digital revolution has transformed economies and societies, millions of people remain excluded from its benefits due to limited access to technology and digital literacy. In remote villages and urban slums alike, individuals are deprived of internet connectivity and the skills necessary to participate in the digital economy. As a result, they are further marginalized, unable to access online educational resources, remote job opportunities, or e-commerce platforms that could potentially uplift their economic status.In conclusion, poverty manifests in multifarious ways,from homelessness and agricultural destitution to educational disparities and digital exclusion. These examples underscore the complex interplay of economic, social, and systemic factors that perpetuate the cycle of poverty. Addressing this pervasive issue requires holistic approaches that prioritize equitable access to education, healthcare, housing, and economic opportunities. By fostering inclusive growth and dismantling structural barriers, societies can work towards breaking the cycle of poverty and fostering a future of prosperity for all.。

THE MICROSIMULATION UNITPoverty in Britain: the impact of government policy since 1997A projection to 2004-5 using microsimulationHolly Sutherland1Microsimulation Research Note No. MU/RN/44May 20041 IntroductionThis note updates and revises the estimates provided in Sutherland, Sefton and Piachaud (2003) (SSP henceforth) of the likely reduction in poverty rates by 2004-5 - the Government’s target year for reducing child poverty by one quarter - and of the impact of policy changes since 1997 on poverty.These estimates are derived using POLIMOD, the Microsimulation Unit’s tax-benefit model based on 1999-2000 Family Resources Survey (FRS) data (see Appendix 1). These data are the same as those used in the earlier study. The estimates are updated in the sense that:• policy changes that have been announced since late 2003 for the fiscal year 2004-5 are included in the calculation of simulated incomes for 2004-5 (see Appendix 2); policies are expressed in 2004-5 prices;• incomes before taxes and benefits are projected to 2004-5 levels (October 2004).They are revised in the sense that:• the projection of incomes from 1999-2000 forward to 2004-5 and backward to 1997 makes use of the most recently-available estimates of changes in income by source.These statistics may themselves have been subject to revision or improvement and in some cases (notably, for rent) our method of projection has been revised (see Appendix3);• some minor mis-interpretations of the nature of recent or prospective policy changes have been corrected, following more details being announced;• estimates of means-tested benefits and credits make use of the latest of take-up figures published by DWP (2004) and Inland Revenue (2003).Since the method has been revised and corrected, albeit to a rather small extent, the difference between the estimates provided in SSP and those provided here should not be taken as the change in poverty between 2003-4 and 2004-5 nor of the impact of policy changes implemented or announced between these two points in time.Throughout we use a poverty line of 60% of contemporary median equivalised income, as in SSP, and provide estimates using income measures on both an After Housing Costs (AHC) and a Before Housing Costs (BHC) basis. Poverty rates and income distributions based on 1 I am grateful to John Hills, David Piachaud and Tom Sefton for useful discussions. Family Resources Survey data for 1999-2000 have been made available by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) through the UK Data Archive. The DWP and the Data Archive bear no responsibility for the analysis or interpretation of the data reported here.simulated incomes are reported in sections 2 and 3. Section 3 also includes some analysis of average changes in income across the income distribution (not provided in SSP). As in SSP and most official analysis to date we use the McClements equivalence scale to adjust for differences in household size and composition. Corresponding estimates of some of the key statistics using the modified OECD equivalence scale are provided in Section 4. It is this scale that will be used in the future for official evaluation of poverty and changes in poverty (DWP, 2003).2 Projected changes in poverty 1996-7 to 2004-5Table 1 presents projected relative poverty rates in 2004-5 compared with rates in 1997 using simulated incomes. These figures take account of changes in policies (taxes and benefits) and projected changes in pre-tax and benefit income (such as earnings growth). They do not take account of changes in composition (such as changes in employment). See SSP (2003; chapter 2) for an analysis of the role of composition change in poverty reduction. Projections of income forward and backwards from 1999-2000 are clearly subject to uncertainties. In particular, projecting beyond the period for which we have aggregate data (from late 2003 or early 2004 to October 2004) involves significant guesswork. For instance, we assume that average earnings continue to grow at the same rate as in the most recent year for which we have data, that is, at 3.7 per cent. This is slower rate of growth in real terms than for several years. If actual earnings growth were to be faster, the relative poverty line (i.e. the median) would be higher, and with it the proportion measured as in relative poverty. The projections represent a best estimate at the time of writing, but no more than that. Details are provided in Appendix 3.Table 1 Simulated estimates of poverty rates in Britain in 1997 and 2004-5All Children Children in 2parent familiesChildren in 1parent familiesPeople overpension ageNumber (000) Rate(%)Number(000)Rate(%)Number(000)Rate(%)Number(000)Rate(%)Number(000)Rate(%)BHC 1997 10,150 18 3,150 25 1,940 20 1,210 40 2,160 21 BHC 2004-5 8,080 14 1,940 15 1,290 13 660 22 1,950 19 Reduction 2,070 4 1,200 9 650 7 550 18 210 2 AHC 1997 13,580 24 4,290 33 2,370 24 1,920 63 2,750 27 AHC 2004-5 10,930 19 3,250 25 1,800 18 1,460 48 1,760 17 Reduction 2,650 5 1,040 8 580 6 460 15 990 10Source: POLIMOD based on 1999/2000 Family Resources Survey dataNote: Poverty is measured as the numbers of people living in households with equivalised income below 60% of the current median (McClements equivalence scale). 2004-5 incomes are based on projections including the tax-benefit system as announced up to Budget Statement of March 2004 (HM Treasury, 2004). Population composition is as in 1999-00. Figures are rounded to the nearest 10,000 persons or percentage point. This does not necessarily mean that estimates are statistically significant to the level shown. Rows or columns may not add due to rounding.This is an updated and revised version of Table 13 in SSP (2003).The results shown in Table 1 are very similar to the earlier estimates for 1997 to 2003-4 in SSP (2003). The they suggest that the target reduction in child poverty of one quarter by 2004-5 will be just met on an AHC basis and will be met more comfortably on a BHC basis, assuming that changes in composition of the population have no affect. Overall poverty rates fall by 4 percentage points on an AHC basis and 5 percentage points on a BHC basis. For the elderly, the same discrepancy in poverty reduction on the two income measures that was observed in SSP (2003) remains. The poverty rate falls by 10 percentage points from 27 to 17 per cent on an AHC basis but by only 2 percentage points from 21 to 19 per cent on a BHC basis.Figure 1 shows the modelled cumulative income distributions for the whole population, for children and for people over pension age in relation to BHC and AHC poverty lines in 1997 and 2004-5. The poverty lines are shown at 60 per cent of contemporary median incomes, but one can use these charts to visualise the poverty rates using lower or higher proportions of the median as poverty thresholds. For example, 50 per cent of the BHC median under 1997 policies (but in 2004-5 prices) is £157.22 per week and 8.9 per cent of people (10.4 per cent of children; 10.6 per cent of elderly) were in households with equivalised income below this level.Figure 1 shows the extent to which the right-ward shift in the poverty line mitigates the effect of increasing income levels on relative poverty rates. For example, on a BHC basis the child poverty rate in 2004-5 using the 1997 poverty line is as low as 10%.Figure 1: Cumulative income distribution and relative poverty lines under 1997and 2004-05 policies and incomesBHC AHC(a) Whole population(b) Children(c) People over pension ageSource : POLIMODEquivalised BHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f p e n s i o n e r sEquivalised AHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f p o p u l a t i o nEquivalised BHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f p o p u l a t i o nEquivalised BHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f c h i l d r e nEquivalised AHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f c h i l d r e nEquivalised AHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f p e n s i o n e r s3. The impact of tax and benefit changesWe can also use policy simulation to give a measure of the impact of policy change by itself. Table 2 shows the 2004-5 estimates as before in Table 1, but by comparison with what would have happened if the tax and benefit system of 1997 (uprated by prices) had still applied in 2004-5. Poverty rates would have been higher in 2004-5 than they were in 1997. For example, 27 per cent of children would be poor (BHC) instead of 25 per cent, as shown in Table 1. In other words, if nothing had been done, poverty would have increased (assuming no changes in composition). Other things being equal the policy changes listed in Appendix 2 have reduced the AHC poverty overall rate by 26 per cent, for children by 28 per cent and for the elderly by 48 per cent (on a BHC basis the percentage reductions are 29, 43 and 29 respectively.)Table 2 Simulated estimates of poverty rates in 2004-5: projected 2004-5 tax-benefitsystem and price-indexed 1997 systemAll Children Children in 2parent familiesChildren in 1parent familiesPeople overpension ageNumber (000) Rate(%)Number(000)Rate(%)Number(000)Rate(%)Number(000)Rate(%)Number(000)Rate(%)BHC 1997 11,430 20 3,420 27 2,000 20 1,420 47 2,760 27 BHC 2004-5 8,080 14 1,940 15 1,290 13 660 22 1,950 19 Reduction 3,350 6 1,480 12 710 7 770 25 810 8 AHC 1997 14,750 26 4,480 35 2,400 25 2,080 68 3,360 33 AHC 2004-5 10,930 19 3,250 25 1,800 18 1,460 48 1,760 17 Reduction 3,820 7 1,230 10 600 6 630 21 1,590 16Source: POLIMOD based on 1999/2000 Family Resources Survey dataNote: Poverty is measured as the numbers of people living in households with equivalised income below 60% of the within-scenario median (McClements equivalence scale). 1997 system is based on parameters of tax and benefit systems as in April 1997, uprated for price inflation only. 2004-5 tax-benefit system is as announced up to Budget Statement of March 2004 (HM Treasury, 2004). Population composition is as in 1999-00 and incomes are all at projected 2004-5 levels. Figures are rounded to the nearest 10,000 persons or percentage point. This does not necessarily mean that estimates are statistically significant to the level shown. Rows or columns may not add due to rounding.This is an updated and revised version of Table 12 in SSP (2003).The overall distributional effect of the policy reforms is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the average percentage change in BHC income in each decile group (by equivalised BHC household income) comparing incomes under the 2004-5 system with those under the price-adjusted 1997 system. The changes are shown for all individuals and for children and the elderly in particular. All decile groups up to the eighth gain on average, and the gains are somewhat – although not dramatically – larger for children than in general. The final set of bars show the overall change and indicate that, as a group, the elderly benefit by most in percentage terms.Projected 2004-05 system compared to price-indexed 1997 systemSource: POLIMOD4.An alternative “counterfactual”The scale of the gains shown in Figure 2 is only robust if we accept that the alternative to the 2004-5 system to have been the 1997 tax and benefit system indexed by prices . An alternative counterfactual assumption would be that 1997 tax and benefit systems were indexed by some measure of household income growth. We illustrate this scenario by indexing all the parameters governing the 1997 tax and benefit system by the increase in average earnings (34 per cent, compared with a 19 per cent increase in prices). Figure 3 shows what the distributional impact of the actual reforms looks like by comparison with this earnings -indexed base.Looking at the impact on the population as a whole, aggregate household incomes are very slightly higher under the actual 2004-5 tax and benefit system than they would have been under the 1997 system indexed by earnings. There is little difference in the overall resource cost to government and impact on households taken as a whole between the actual reform package and an alternative world in which 1997 policy had been maintained in relation to earnings, but without any structural reforms. However, the diagram shows that the distributional effects of the actual reforms remain more progressive than the earnings-linked base. There has been an effective transfer from higher-income to lower-income households. This redistribution has achieved the reductions in relative poverty shown in Table 2.12345678910ALLdecile of equivalised household disposable income (1997 policies)% c h a n g e i n i n c o m eProjected 2004-5 system compared to earnings-indexed 1997 systemSource: POLIMODInterestingly, on this basis, the redistribution now clearly benefits children by more than the elderly or the population in general (see the final set of bars in Figure 3). With earnings indexation, state pension incomes under the 1997 system are relatively more generous and the 2004-5 system appears less advantageous than under the price indexation assumption. 5.An alternative equivalence scaleA recent government review of child poverty measurement recommended the use of the modified OECD equivalence scale and BHC incomes in future, instead of the McClements scale and figures based on both AHC and BHC incomes (DWP, 2003). Table 3 shows poverty estimates for (a) 1997 policies on 1997 incomes (b) 1997 policies (indexed by prices) on projected 2004-5 incomes and (c) 2004-5 policies on 2004-5 incomes, all using BHC incomes adjusted by the OECD scale. Appendix 4 compares the two scales. Figure 4 shows the same results as in Figure 3, but using the OECD scale and Figure 5 shows the BHC cumulative distributions for (a) and (c) (as in Figure 1) using the OECD scale.Generally, while the use of the alternative equivalence scale increases measured poverty rates somewhat, there is little effect on the change in poverty rates shown in Table 3 compared with those in Tables 1 and 2. Brewer et al (2004) carry out a more extensive investigation of the effects of using the alternative scale on child poverty statistics, and have similar findings.12345678910ALLdecile of equivalised household disposable income (1997 policies)% c h a n g e i n i n c o m eTable 3 Simulated estimates of poverty in 1997 and 2004-5: Before Housing Costs andusing the modified OECD equivalence scaleAll ChildrenChildren in 2parent families Children in 1 parent familiesPeople over pension ageNumber (000) Rate (%) Number (000) Rate (%) Number (000) Rate (%) Number (000) Rate (%) Number (000) Rate (%) (a) 1997 policies and incomes10,910 19 3,460 27 1,980 20 1,480 49 2,410 24 (b) 1997 policies, 2004-5 incomes12,160 21 3,650 28 2,120 22 1,630 53 3,120 31 (c) 2004-5 policies and incomes 8,830 16 2,250 18 1,330 14 920 30 2,220 22 Reduction (c) - (a) 2,080 4 1,210 9 650 7 560 18 200 2 Reduction (c) - (b)3,33061,400117908700239009Source: POLIMOD based on 1999/2000 Family Resources Survey dataNote: Poverty is measured as the numbers of people living in households with equivalised income below 60% of the within-scenario median (modified OECD equivalence scale). Figures are rounded to the nearest 10,000 persons percentage point. This does not necessarily mean that estimates are statistically significant to the level shown. Rows or columns may not add due to rounding.Figure 4: Average percentage difference in income: Projected 2004-05 system compared to price-indexed 1997 system (ranking by household income adjusted by the modified OECD equivalence scale)Source:POLIMOD12345678910ALLdecile of equivalised household disposable BHC income (1997 policies)% c h a n g e i n i n c o m eFigure 5: Cumulative income distribution and relative poverty lines under 1997and 2004-05 policies and incomes using the modified OECD equivalence scale(a) Whole population (b) Children(c) People over pension ageSource : POLIMOD6. Concluding pointsRevised and updated simulations of the effect of policy changes by 2004-5 result in similar – and somewhat strengthened - conclusions about the effect of government policy to date on poverty as were drawn in SSP (2003). Additions to the value of the Child Tax Credit since the SSP analysis, offset to some extent by the effects of growth in Council Tax and the failure to index all elements of the system results in projected poverty rates that suggest that the child poverty target for 2004-5 will be just met on an AHC basis and will be met more comfortably on a BHC basis. However, as before, this conclusion assumes that compositional changes have no adverse effect on poverty and this may not turn out to be the case.Adopting an alternative equivalence scale has little effect on the assessment of the size of the change in poverty. However, the decision to focus attention in UK analysis on the sameEquivalised BHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f p o p u l a t i o nEquivalised BHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f p e n s i o n e r sEquivalised BHC household income (£ per week in 2004/5 prices)% o f c h i l d r e nmeasure of relative poverty as is used in assessments made at the EU level (BHC income using the modified OECD scale) means that instead of three measures (AHC and BHC using McClements plus the EU measure) there will in the future be just one (DWP, 2003). The analysis reported here, together with that in SSP (2003) and other studies (Brewer et al., 2004) shows that different measures do not necessarily always behave in the same way. There are dangers in relying on just one measure since movement in a particular measure can be due to particular influences on the level of the poverty line and its relationship with benefit levels. Given the essential arbitraryness of a poverty line set at a percentage of median income it seems important to retain as much richness as possible in the ways that incomes themselves are measured and compared, in order to provide the basis for a complete understanding of the underlying influences.Conventionally policy changes are assessed against a neutral counterfactual of price indexation. Thus if incomes are maintained in real terms then the household is considered to be neither a gainer nor a loser. However, we have seen that indexation is not sufficient to protect a household from falling into relative poverty if median incomes are growing in real terms. An alternative is to adopt “constant shares” as the neutral position. In this case households whose share is reduced are considered losers. The counterfactual is that the tax and benefit system would be uprated by average incomes. Redistribution on top of this is not necessary if the status quo is to be maintained, but is necessary if relative poverty is to be reduced. We have seen that the share of resources available to households through the tax and benefit system hardly increased between 1997 and 2004-5 as a proportion of average income (Figure 3). However, there was some redistribution of shares: losses outweighed gains in the top half of the distribution and on average households in the bottom half increased their share. In particular, there was redistribution towards children in the bottom half. (Again, this leaves aside changes in the shares of pre-tax and benefit income that might have taken place between 1997 and 2004-5.)ReferencesBrewer M., A. Goodman, M. Myck, J. Shaw and A. Shephard, 2004. Poverty and Inequality in Britain: 2004, IFS Commentary 96.DWP. 2003. Measuring Child Poverty. London: DWP.DWP. 2004. Income Related Benefits: Estimates of Take-Up in 2001/2002. London: DWP. DWP. 2004a. Households Below Average Income – 1994/5 to 2002/03. Leeds: Corporate Document Services.HM Treasury. 2004. Budget 2004: Prudence for a Purpose: A Britain of stability and strength, HC 301. London: TSO.Inland Revenue. 2003. Working Families’ Tax Credit: Estimates of Take-up rates in 2001-02.London: Inland Revenue.Redmond G., H. Sutherland and M. Wilson. 1998. The arithmetic of tax and social security reform: a user's guide to microsimulation methods and analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Sutherland H., T. Sefton and D. Piachaud. 2003. Poverty in Britain: the impact of government policy since 1997. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation./bookshop/details.asp?pubID=563Appendix 1 Policy simulation using POLIMODPOLIMOD is a tax-benefit microsimulation model constructed and maintained by the Microsimulation Unit in the Department of Applied Economics at the University of Cambridge. See Redmond et al. (1998) for more information. The household income variables used here to measure poverty have been deliberately defined to be as similar as possible to those used in the Household Below Average Income (HBAI) statistics (DWP, 2004a). There are some minor departures from HBAI methodology due to the fact that we must simulate taxes and benefits (and earnings, where these are affected by the Minimum Wage) in order to evaluate changes in the rules that govern them. The 1999/2000 FRS micro-data are updated to 2004/5 levels of prices and incomes in order to evaluate contemporary policy changes, whereas HBAI statistics for a given year use data collected in that year. In addition, there are some differences which arise because some components of income (taxes and benefits) are simulated rather than using values recorded in the survey data.POLIMOD calculates liabilities for, or entitlements to income tax, National Insurance contributions (NICs), Child Benefit, Family Credit (FC), Working Tax Credit (WTC), Child Tax Credit (CTC) Income Support (IS) - including income-related Job Seekers Allowance and pensioners’ Minimum Income Guarantee (MIG) - Housing Benefit (HB) and Council Tax Benefit (CTB). The effect of the minimum wage is modelled by assuming that all with hourly earnings below the relevant minimum are brought up to it and that working hours do not change. Resulting changes in earnings then affect tax and benefits. Otherwise, elements of income are drawn from the recorded values in the FRS dataset. The main effect of simulating the tax and benefit components of income is to narrow the income distribution to some extent. POLIMOD captures the effects of non- take up of pre-2003 means-tested benefits (FC/WFTC, IS, HB and CTB) by applying the take-up proportions estimated by the DWP (2004) and Inland Revenue (2003) using data for 2001-2. For example we assume that some 15% of lone parents do not receive the FC to which they were entitled, and 32% of pensioners do not receive the IS (MIG) to which they are entitled. We assume that take-up behaviour is not affected by changes in the size of benefit entitlements. Little is known about what to expect in relation to take-up of the new tax credits, introduced in 2003. We assume that take-up of income-tested CTC will be the same as IS (on a case-by case basis); take-up of WTC is assumed to be the same as WFTC in 2001-2 and to have the same probability for the new groups who are eligible. Take-up of both parts of the Pension Credit (Guarantee Credit and the Savings Credit) is assumed to be the same as that for MIG (IS for pensioners).Appendix 2: Summary of main modelled changes in tax and benefit policy 1997 – 2004-5Changes that are due for implementation part way through a fiscal year are modelled as though they apply all year.2Amounts are weekly and in current prices and differences are expressed in real terms, unless otherwise specified.The National Minimum Wage was introduced in 1999.By October 2004 the hourly rate for employees aged 22 and over was £4.85, the rate for young (18-21) and trainee workers was £4.10 and the rate for 16-17 year olds was £3.00.Lone parent benefit abolished (the 1997 benefit would have been worth £7.20 in 2004/5 prices).Child benefit increased in real terms by £3.35 for first or only children and £0.35 for other children.Maternity pay: the flat rate element increased substantially in £100 in 2003/4. The 2004/5 level was £36.70 per week higher in real terms than the level in 1997.Basic state retirement pension(and widows’ pension) has been increased in real terms by £5.50 (Cat. A) or £3.30 (Cat. B).Winter fuel allowance: increased from a low level in 1997 to £200 per year for households containing a person aged over 60, with a further payment of £100 if aged over 70. Incapacity benefit is reduced by 50p for every £1 of occupational or personal pension income over £85 per week.Working Families Tax Credit (WFTC) replaced family credit in 1999 and this was replaced in turn in 2003 by the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and the Working Tax Credit (WTC). The CTC also subsumes the Children’s Tax Credit, which was itself a replacement for tax allowances for couples and lone parents (see below under income tax), the child elements of Income Support and child additions to non-meanstested benefits for adults.Compared with Family Credit in 1997 the maximum value of CTC is higher per child (by 128% in real terms for young children but less – 38% and 10% for children aged 11-15 and 16-17 respectively). The credit is tapered away according to gross income (with a lower effective taper than in Family Credit, which depended on net income) and investment income is included (rather than capital limits and tariff income as in IS and FC). A minimum payment equivalent to the couple and lone parent tax allowances (but somewhat higher, and significantly higher for families with babies under 1 year old) is paid for those with incomes up to the income tax higher rate threshold. For higher incomes, it is tapered away. Compared with the child amounts in Income Support in 1997, the CTC payments are 120%, 50% and 26% greater for children aged 0-10, 11-15 and 16-17 respectively (worth approximately £23, £14 and £9 in real terms per week). However, the lone parent premium which has been abolished, would have been worth £5.60 in 2004/5. The amounts paid extra for disabled children have been increased.The Working Tax Credit (WTC) uses similar rules about work conditions as Family Credit (and Disability Working Allowance) but extends entitlement to some groups without children or disabilities (working 30+ hours) and operates with a lower taper. The Child Care Tax Credit is linked to entitlement to WTC (but is not modelled here).2 For example, the minimum wage is uprated part-way through 2004-5. The uprated amount is assumed to apply throughout the year.The Pension Credit (PC) replaces the Minimum Income Guarantee (IS for people aged 60+). It has two parts, both of which are assessed jointly for couples: the Guarantee Credit (GC), based on MIG but with some relaxation of rules, and the Savings Credit(SC) which is an additional top-up for those with modest incomes above the MIG and/or basic pension level. In the GC, for those aged 60+ and their partners the upper capital limit is removed and the assumed tariff rate of income from capital is halved. Hours of work conditions are removed and some sources of income are exempted from the income test. Benefit levels are increased in real terms by up to £27 for single pensioners and £40 for couples (less for those aged 75+ who were already paid higher premia in 1997). In addition the Savings Credit is for people aged 65+ and their partners. This tops up small amounts of qualifying income above the level of the basic state pension at a rate of 60p per £ of income (assessed jointly), up to a maximum. The SC is reduced by any income in excess of the Guarantee Credit level at a rate of 40%. Capital limits for pensioners on PC are increased but for all others they are reduced in real value. (These have not been uprated since 1988.)Housing benefit(HB) and Council tax benefit(CTB) changes match those for Income Support (and, where relevant, Pension Credit and Child Tax Credit) except that the real value of the 1997 lone parent premia which were abolished is £12.80 in 2004/5 prices.National insurance contributions: Class 1 employee contribution lower earnings limit (LEL) increased by £17 in real terms; upper earnings limit (UEL) increased by £50; contributions on earnings below the LEL (“entry fee”) abolished (worth up to £1.48 per week). Class 1 rate increased from 10% to 11% and extra 1% charged on all earnings above the UEL. Class 2 (self-employed) contributions reduced by £5.25. Class 4(self-employed) lower profits limit aligned with the Class 1 LEL (a reduction of £69); Class 4 upper profits limit aligned with the Class 1 UEL (an increase of £50); the rate of Class 4 increased from 6% to 8% and an extra 1% charged on profits above the upper profits limit.Income tax schedule: introduction of a 10% lower rate; this applies on the first £2,020 of annual taxable income, including income from investments (replaces 20% lower band); standard rate reduced from 23% to 22%.Income tax allowances: Personal allowance not indexed in 2003/4 so its 2004/5 value is 1.25% less than its 1997 value in real terms. Age-related personal allowances increased by more than inflation; Married couples allowance (MCA) for couples both aged under 65 and Additional personal allowance for lone parents abolished. (Under 1997 policy these would have been worth £6.00 per week in 2004/5 prices.) Age-related MCA increased so that pensioner couples do not lose. Age-related personal allowances increased to 7-10% more than their 1997 real value..Mortgage tax relief abolished. (In 1997 the maximum annual relief was 15% of the annual interest on £30,000.)Council tax increased in real terms by 39% (on average). This represents a real increase of about £6.15 per week on a Band D Council Tax in 2004/5 prices.。