Observational studies also show that postmenopausal women who receive hormone

replacement therapy (HRT) have a lower rate of CVD and cardiac death than those not

receiving HRT [5,6]. However, two randomized prospective primary or secondary

prevention trials, the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) [7] and the Heart and Estrogen/

Progestin Replacement Study (HERS I and II) [8,9], showed that HRT may actually increase

the risk and events of CVD in postmenopausal women. The reasons for this paradoxical

characterization of HRT as both beneficial and detrimental remain unclear. Many potential

factors may contribute to the adverse outcome, among them the age of patients, preexisting

CVD and/or risk, when HRT was initiated, the type of HRT given (conjugated equine

estrogen with progestin), dosage, and the thromboembolic properties of estrogen and

progestin [6,10–13]. Overall, the use of HRT has become one of the most controversial

topics related to women’s health, making it all the more urgent to clarify whether estrogens

(and/or HRT) prevent or promote CVD, as well as the mechanism(s) involved.Sex differences in cardiovascular disease Blood pressure is typically lower in premenopausal women than men; however, after menopause it increases to levels similar to or higher than age-matched men [2,4].Approximately 75% of women over 60 years of age are hypertensive [14]. Comparison of cohorts from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III (1988–1994) with NHANES IV (1999–2002) showed that over the time period from 1994 to 2002,the percentage of hypertensive patients decreased among men but increased among women [15]. Indeed, the percentage of individuals with uncontrolled hypertension was also higher in women than men (55.9 ± 1.4 vs. 50.8 ± 2.1%), despite the fact that a higher percentage of women than men reported having their blood pressure measured within the previous 6months [15]. It is not clear why hypertension is less well controlled in women than men despite more frequent blood pressure monitoring, but this observation suggests the mechanism(s) responsible may differ in men and women.

Premenopausal women also have a much lower incidence and prevalence of heart and renal

disease compared to men of the same age [4,16–18]. This sex difference in favor of women

also gradually disappears after menopause, indeed cardiovascular risk becomes even higher

in older women [3,19]. Although it has been debated whether the loss of cardiorenal

protection in postmenopausal women is related to aging, loss of female hormones or both,

substantial studies indicate that reduced levels of ovarian hormones constitute a major risk

factor for development of CVD [1,4,16,17,20]. The recent Nurse’s Health Study [21?] and

the WISE Study [22], as well as others [23], have demonstrated that early menopause in

young women due to ovarian dysfunction or bilateral oophorectomy is associated with

increased risk of CVD compared to women with normal endogenous estrogen levels. In

animal models of CVD, females exhibited a lower mortality, less vascular injury, better

preserved cardiovascular function and slower progression to decompensated heart failure,

the differences being narrowed or abolished by ovariectomy or deficiency of endogenous

estrogen [24??,25–27].

Endogenous estrogen may have a cardioprotective effect in men as well. In men, significant

amounts of estrogen can be produced via conversion of C19 androgenic steroids to 17β-

estradiol by the enzyme aromatase. In healthy young men inhibition of aromatase lowers

plasma 17β-estradiol, and is associated with decreased flow-mediated dilatation of the

brachial artery [28]. Similarly, aromatase knockout mice demonstrated impaired endothelial

function [29]. Supplemental estrogen in men attenuated volume overload-induced structural

and functional remodeling [30] and slowed the progression of left ventricular dysfunction to

heart failure post-myocardial infarction (MI) [31]. Taken together, the evidence suggests

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

that the differences in cardioprotection between men and women may be attributable largely

to the protective effect of estrogen in women.

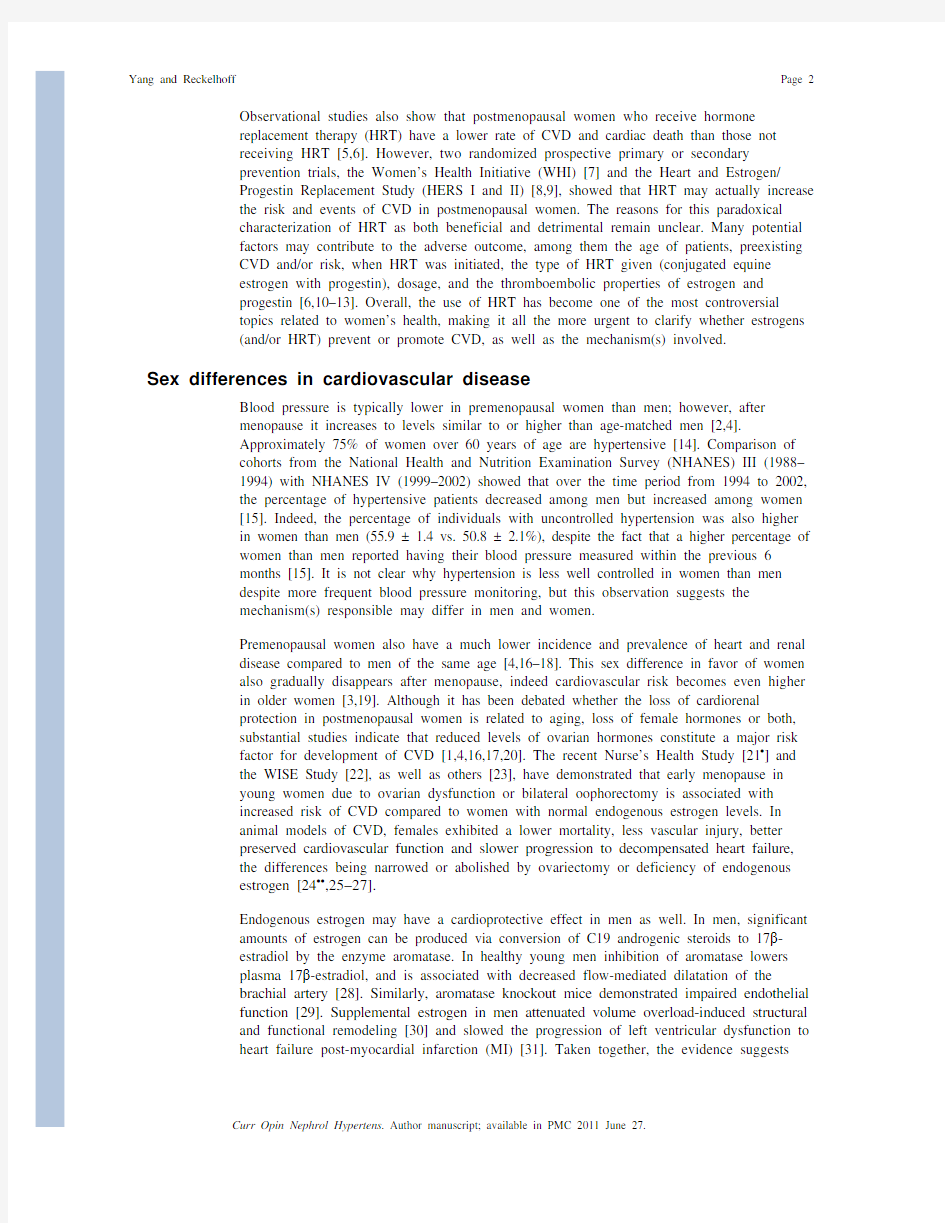

Cardioprotective mechanisms of estrogen Two classical estrogen receptor subtypes, ER α and ER β, have been identified in the heart and vasculature [32,33]. The long-term effects of estrogen may be mediated by both ER αand ER β through alteration of gene expression and protein synthesis (genomic action) [34],whereas the rapid nongenomic effect of estrogen may involve calcium-mediated activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase [35], cGMP and intracellular signal transduction pathways [32,33] (Fig. 1). Recently, a third membrane-bound and G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER), GPR30, has been identified. In addition to estrogen, other hormones/factors such as progestin, genistein and estrogen antagonist/selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) tamoxifen and ICI 182780 have been shown to act as GPR30ligand; however, their affinity to GPR30 is 10-fold to 100-fold less than estrogen [36].Studies have demonstrated estrogen acting via GPR30 and transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) inducing rapid signal transduction, including activation of MAP kinase (MAPK), protein kinase A (PKA) and PI3 kinase (PI3K) [36]. In the heart,activation of GPR30 with the specific agonist G1 reduced ischemia/reperfusion injury and preserved cardiac function acting through PI3K-dependent Akt pathways [37??], suggesting a cardioprotective role of this newly defined estrogen receptor (Fig. 1).There are other recently discovered mechanisms by which estrogens could provide cardioprotection. Estrogen has been shown to increase expression of superoxide dismutase and inhibit NADPH oxidase activity, thereby reducing oxidative stress [26,32,38]. Estrogen acting via ER β increases protein S-nitrosylation, a common post-translational protein modification, leading to cardioprotection [39]. Inflammation is considered a key element in the pathogenesis of hypertension, atherosclerosis and development of coronary heart disease (CHD), and estrogen has been reported to reduce inflammatory markers [32,40]. Estrogen

also attenuates afterload- or agonist-induced cardiac hypertrophy via inhibition of

calcineurin, hypertrophic transcription factor NF-AT, and MAPK signaling pathways [41].

In addition, estrogen has a profound antiapoptotic and pro-survival effect on cardiomyocytes

via activation of Akt and inhibition of caspase-3, GSK-3β [42], p38α-mediated p53

phosphorylation, and JNK1/2-mediated NF-κB activation [43] (Fig. 1). Moreover, estrogen

has been shown to promote endothelial progenitor cell mobilization [44] and enhance

mesenchymal stem cell-mediated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) release

[45,46?], improving endothelial and myocardial functional after ischemia.

Hormonal replacement therapy

Observational studies have suggested that HRT decreases the risk of CVD and reduces

mortality in postmenopausal women with heart disease [5,47]. However, large-scale clinical

trials, the HERS I and II [8,9] and WHI [7], showed an unfavorable outcome of HRT on

CVD risk and events. So far, we know of no good explanation as to why young or

premenopausal women are protected from CVD and yet postmenopausal women do not

benefit from HRT. The controversy over the risks and benefits of HRT in primary

prevention of CVD continues, and much of the debate has focused on the age of

postmenopausal women enrolled in these trials, when HRT is initiated, duration of the

replacement, dosage and the form of estrogen used [6,10–13].

Age and timing of hormonal replacement therapy initiation

In most observational studies, women started HRT around the time of menopause (which

occurs on average at 51 years), whereas the WHI trials examined postmenopausal women

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

ranging from 50 to 79 who began HRT at an average age of 63.3 years; 67% of them were

60–79 years of age, and 73% of this aged population had never received HRT. Presumably

many of them already had atherosclerotic plaques and thus were predisposed to thrombosis.

These preexisting conditions, even subclinical, may have had a profound impact on the

outcome of HRT use, when the goal was primary prevention. Indeed, the later published

‘Coronary Artery Calcium Study’ (WHI-CACS) [48], that was restricted to postmenopausal

women aged 50–59 years, showed that HRT initiated in these younger women reduced

coronary artery calcification and the prevalence of subclinical CHD. Furthermore, a

secondary analysis of the WHI data set [49] showed that women who began HRT closer to

menopause tended to have a reduced risk of CVD. More recently, a cohort study with long-

term follow-up showed that women who underwent bilateral ovariectomy before age 45 had

increased cardiovascular mortality, and this risk was significantly lowered by treatment with

estrogen through age 45 or longer [23]. In monkeys, starting HRT in early menopause

reduced coronary artery atherosclerosis by about 50–70%, whereas delaying initiation of

HRT for 2 years (about 6 years in human terms) blunted this protection [50]. Taken together,

these studies support the hypothesis that estrogen therapy may have a cardiovascular benefit

when initiated early after the onset of menopause.

There is evidence that atherosclerosis involves an ongoing inflammatory response, which is

more profound during the early years of menopause [40,51,52]. Cytokine production has

been shown to increase in the early years following menopause but thereafter declines to

within the premenopausal range [52,53?]. Estrogen reportedly reduces interleukin (IL)-1,

IL-6, IL-18, C-reactive protein, tissue necrosis factor (TNF)-α and increases macrophage

colony-stimulating factor, a cytokine that lowers plasma cholesterol levels by enhancing

clearance of low-density lipoprotein [53?,54–56]. Thus since inflammatory responses are

higher in early postmenopause while absence or reduction of endogenous estrogen may

accelerate the progression of atherosclerosis, the timing of HRT with respect to onset of

menopause may have important ramifications regarding its efficacy in preventing or

delaying the progression of atherosclerosis and CVD. Alternatively, some of the WHI data

may be explained by the fact the HRT has been shown to increase indicators of

inflammation, such as TNF-α [53?]. Future studies will be necessary to ferret out the

contribution of HRT to inflammation in postmenopausal women at various ages.

Duration of hormonal replacement therapy

Re-analysis of the WHI data set [49] shows that younger postmenopausal women given

relatively short-term HRT (<10 years) tended to have reduced risk and incidence of CVD,

but this protection gradually disappeared in succeeding years. It is reported that short-term

HRT (2–3 years) reduced CVD mortality by 30%, associated with significantly reduced

severity of atherosclerotic lesions [57]. Klaiber et al. [58] studied the effect of HRT on

serum estradiol levels in women soon after menopause (average 12.9 months) vs. a long

time after menopause (average 78 months) and found that estradiol was 46% higher after

long duration HRT. It is known that some of the adverse effects of estrogen, such as

increased breast and endometrial cancer and venous thrombosis, correlated positively with

plasma estradiol levels; however, the cardiovascular consequences due to HRT-induced

excessive increase in plasma estradiol are not well established and need further

investigation.

Dosage

Most clinical trials use only one dose of estrogen (0.625 mg conjugated equine estrogen,

CEE) plus one dose of progestin (2.5 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate, MPA). Choice of

CEE dosage is largely based on data from prospective studies showing that it takes at least

0.625 mg/day to significantly increase bone mineral density. However, it is not clear NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

whether this is an appropriate dosage for preventing or reducing CVD risk. In a prospective

study [5], 0.3 mg/day decreased major coronary events in women compared to untreated

controls, whereas 0.625 mg or more CEE combined with progestin increased the risk of

stroke. Genant et al. [59] and Villa et al. [60?] showed that low-dose estrogen slightly

increased plasma estradiol but improved endothelial function and lipid profile without

endometrial hyperplasia, while higher doses increased plasma estradiol two-fold to three-

fold and were associated with endometrial hyperplasia. Unfortunately, they did not examine

the dose effect of estrogen on vascular calcification and risk of CVD. In monkeys fed an

atherogenic diet, 0.3 mg CEE reduced coronary artery atherosclerosis comparable to the

standard dose [61]. We recently reported that in mice with intact cardiac function or

myocardial infarction, low-dose estrogen tended to be cardioprotective whereas at higher

doses that increased plasma estradiol beyond the physiological levels, estrogen increased

mortality, worsened cardiac function and caused severe damage to the kidney, including

hydronephrosis, severe albuminuria, renal tubular dilatation and glomerulosclerosis. High

dose of estrogen also caused ascites, hepatomegaly and fluid retention in the uterine horns

[62?,63??]. High doses of estrogen also raised testosterone significantly, although the

mechanisms by which estrogen replacement increases testosterone are not clear. Taken

together, it is rational to speculate that estrogen dosage may have a significant impact on its

outcome on the heart, vasculature and kidney.

Estrogen only vs. standard hormonal replacement therapy

It has been questioned whether the adverse effect of HRT on thromboembolism is

attributable to the presence of progestin. It is reported that CEE doubled flow-mediated and

endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in postmenopausal women and this effect was

reversed by MPA [64]. In estrogen-deficient cynomolgus monkeys fed high-fat diet, CEE

reduced coronary artery plaque formation and this effect was abolished by MPA [65]. The

WHI-CACS survey showed that CEE alone significantly reduced coronary artery

calcification [48]. In women with hysterectomy, CEE reduced CHD by 44% in younger

postmenopausal women (50–59 years), although no overall cardiovascular protective effects

were evidenced [66].

The ongoing Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS) [67??], a prospective,

randomized and placebo-controlled multicenter trial, is designed to determine the effect of

oral CEE or transdermal 17β-estradiol with or without progestin on atherosclerosis and

coronary calcification in women within 3 years of menopause. KEEPS is expected to

provide valuable information on timing, route and protocols of HRT for prevention of CVD

in women.Conclusion

Whether estradiol protects women from CVD is still unknown. Studies in women previous

to the HERS I and II and the WHI and many animal studies suggested that indeed both

estradiol and HRT protected women from CVD via various mechanisms. The fact that

premenopausal women have a lower incidence of CVD than men also implicates the sex

steroids in women as playing a role in this protection. If that is true, we then need to

determine why aging in women prevents HRT from being as effective in protecting against

CVD as endogenous estradiol and progesterone. Are there age-related changes in estrogen

receptors, intracellular signaling, or genomics that alter the response to HRT in older

postmenopausal women? What role do increases in androgens unopposed by estrogens in

postmenopausal women play in mediating CVD? In addition, what role does obesity –which

is reaching epidemic proportions in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women – play in

mediating the response to HRT? Future studies will be necessary to answer these important

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

questions and lead to more effective therapeutic strategies to improve the quality of life for women following menopause.Acknowledgments This work was supported by the following grants: NIH HL078951 (XPY) and NIH HL66194, HL66072 and HL51971 (JFR).References and recommended reading Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:? of special interest ?? of outstanding interest Additional references related to this topic can also be found in the Current World Literature section in this issue (p. 197).1. Bittner V. Menopause, age, and cardiovascular risk: a complex relationship. J Am Coll Cardiol.2009; 54:2374–2375. [PubMed: 20082926]2. Coylewright M, Reckelhoff JF, Ouyang P. Menopause and hypertension: an age-old debate.Hypertension. 2008; 51:952–959. [PubMed: 18259027]3. Kim ES, Menon V. Status of women in cardiovascular clinical trials. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009; 29:279–283. [PubMed: 19221204]4. Reckelhoff JF, Maric C. Sex and gender differences in cardiovascular-renal physiology and pathophysiology. Steroids. 2010; 75:745–746. [PubMed: 20595039]5. Grodstein F, Manson JE, Colditz GA, et al. A prospective, observational study of postmenopausal hormone therapy and primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Ann Intern Med. 2000;

133:933–941. [PubMed: 11119394]

6. Rosano GM, Vitale C, Fini M. Cardiovascular aspects of menopausal hormone replacement therapy.Climacteric. 2009; 12 (Suppl 1):41–46. [PubMed: 19811240]

7. Manson JE, Hsia J, Johnson KC, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2003; 349:523–534. [PubMed: 12904517]

8. Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, et al. for the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS)Research Group. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. JAMA. 1998; 280:605–613. [PubMed: 9718051]

9. Hulley S, Furberg C, Barrett-Connor E, et al. for the HERS Research Group. Noncardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II). J Am Med Assoc. 2002; 288:58–66.

10. Hodis HN. Assessing benefits and risks of hormone therapy in 2008: new evidence, especially with regard to the heart. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008; 75 (Suppl 4):S3–S12. [PubMed: 18697261]

11. Schnatz PF. Hormonal therapy: does it increase or decrease cardiovascular risk? Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006; 61:673–681. [PubMed: 16978427]

12. Haines CJ, Farrell E. Menopause management: a cardiovascular risk-based approach. Climacteric.2010; 13:328–339. [PubMed: 20001565]

13. Harman SM. Estrogen replacement in menopausal women: recent and current prospective studies,the WHI and the KEEPS. Gend Med. 2006; 3:254–269. [PubMed: 17582367]

14. Barton M, Meyer MR. Postmenopausal hypertension: mechanisms and therapy. Hypertension.2009; 54:11–18. [PubMed: 19470884]

15. Kim JK, Alley D, Seeman T, et al. Recent changes in cardiovascular risk factors among women and men. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006; 15:734–746. [PubMed: 16910905]

16. Rosano GM, Vitale C, Marazzi G, Volterrani M. Menopause and cardiovascular disease: the evidence. Climacteric. 2007; 10 (Suppl 1):19–24. [PubMed: 17364594]

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

17. Wake R, Yoshiyama M. Gender differences in ischemic heart disease. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov. 2009; 4:234–240. [PubMed: 19545234]18. Silbiger S, Neugarten J. Gender and human chronic renal disease. Gend Med. 2008; 5 (Suppl A):S3–S10. [PubMed: 18395681]19. Anderson RD, Pepine CJ. Gender differences in the treatment for acute myocardial infarction: bias or biology? Circulation. 2007; 115:823–826. [PubMed: 17309930]20. Matthews KA, Crawford SL, Chae CU, et al. Are changes in cardiovascular disease risk factors in midlife women due to chronological aging or to the menopausal transition? J Am Coll Cardiol.2009; 54:2366–2373. [PubMed: 20082925]21?. Parker WH, Broder MS, Chang E, et al. Ovarian conservation at the time of hysterectomy and long-term health outcomes in the Nurses’ Health Study. Obstet Gynecol. 2009; 113:1027–1037.A prospective study that demonstrates that bilateral oophorectomy before age 50 years was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality, CHD and stroke. [PubMed: 19384117]22. Bairey Merz CN, Johnson BD, Sharaf BL, et al. Hypoestrogenemia of hypothalamic origin and coronary artery disease in premenopausal women: a report from the NHLBI-sponsored WISE study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003; 41:413–419. [PubMed: 12575968]23. Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, et al. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009; 16:15–23. [PubMed: 19034050]24??. Wang F, Keimig T, He Q, et al. Augmented healing process in female mice with acute myocardial infarction. Gend Med. 2007; 4:230–247. A mouse study showing that females had low cardiac rupture and mortality, augmented healing and better reserved cardiac function after myocardial infarction. [PubMed: 18022590]25. Dent MR, Tappia PS, Dhalla NS. Gender differences in apoptotic signaling in heart failure due to volume overload. Apoptosis. 2010; 15:499–510. [PubMed: 20041302]26. Lagranha CJ, Deschamps A, Aponte A, et al. Sex differences in the phosphorylation of mitochondrial proteins result in reduced production of reactive oxygen species and cardioprotection in females. Circ Res. 2010; 106:1681–1691. [PubMed: 20413785]27. Javeshghani D, Schiffrin EL, Sairam MR, Touyz RM. Potentiation of vascular oxidative stress and nitric oxide-mediated endothelial dysfunction by high-fat diet in a mouse model of estrogen

deficiency and hyperandrogenemia. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2009; 3:295–305. [PubMed: 20409973]

28. Lew R, Komesaroff P, Williams M, et al. Endogenous estrogens influence endothelial function in young men. Circ Res. 2003; 93:1127–1133. [PubMed: 14592997]

29. Kimura M, Sudhir K, Jones M, et al. Impaired acetylcholine-induced release of nitric oxide in the aorta of male aromatase-knockout mice. Regulation of nitric oxide production by endogenous sex hormones in males. Circ Res. 2003; 93:1267–1271. [PubMed: 14576203]

30. Gardner JD, Murray DB, Voloshenyuk TG, et al. Estrogen attenuates chronic volume overload induced structural and functional remodeling in male rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.2010; 298:H497–H504. [PubMed: 19933421]

31. Cavasin MA, Tao ZY, Yu AL, Yang X-P. Testosterone enhances early cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction, causing rupture and degrading cardiac function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006; 290:H2043–H2050. [PubMed: 16361364]

32. Xing D, Nozell S, Chen YF, et al. Estrogen and mechanisms of vascular protection. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009; 29:289–295. [PubMed: 19221203]

33. Babiker FA, De Windt LJ, van Eickels M, et al. Estrogenic hormone action in the heart: regulatory network and function. Cardiovasc Res. 2002; 53:709–719. [PubMed: 11861041]

34. Barkhem T, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA. Molecular mechanisms, physiological consequences and pharmacological implications of estrogen receptor action. Am J Pharmacogenom. 2004; 4:19–28.

35. Ruehlmann DO, Mann GE. Rapid nongenomic vasodilator actions of oestrogens and sex steroids.Curr Med Chem. 2000; 7:533–541. [PubMed: 10702623]

36. Prossnitz ER, Maggiolini M. Mechanisms of estrogen signaling and gene expression via GPR30.Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009; 308:32–38. [PubMed: 19464786]

37??. Deschamps AM, Murphy E. Activation of a novel estrogen receptor, GPER, is cardioprotective

in male and female rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009; 297:H1806–H1813. A recent NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

study showing that activation of the newly discovered estrogen receptor, GPER, improves cardiac function and reduces infarct size. [PubMed: 19717735]38. Zhang QG, Raz L, Wang R, et al. Estrogen attenuates ischemic oxidative damage via an estrogen receptor alpha-mediated inhibition of NADPH oxidase activation. J Neurosci. 2009; 29:13823–13836. [PubMed: 19889994]39. Lin J, Steenbergen C, Murphy E, Sun J. Estrogen receptor-beta activation results in S-nitrosylation of proteins involved in cardioprotection. Circulation. 2009; 120:245–254. [PubMed: 19581491]40. Reckelhoff JF. Cardiovascular disease, estrogen deficiency, and inflammatory cytokines.Hypertension. 2006; 48:372–373. [PubMed: 16864743]41. Donaldson C, Eder S, Baker C, et al. Estrogen attenuates left ventricular and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by an estrogen receptor-dependent pathway that increases calcineurin degradation.Circ Res. 2009; 104:265–275. [PubMed: 19074476]42. Wang F, He Q, Sun Y, et al. Female adult mouse cardiomyocytes are protected against oxidative stress. Hypertension. 2010; 55:1172–1178. [PubMed: 20212261]43. Liu CJ, Lo JF, Kuo CH, et al. Akt mediates 17beta-estradiol and/or estrogen receptor-alpha inhibition of LPS-induced tumor necresis factor-alpha expression and myocardial cell apoptosis by suppressing the JNK1/2-NFkappaB pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2009; 13:3655–3667. [PubMed:20196785]44. Erwin GS, Crisostomo PR, Wang Y, et al. Estradiol-treated mesenchymal stem cells improve myocardial recovery after ischemia. J Surg Res. 2009; 152:319–324. [PubMed: 18511080]45. Baruscotti I, Barchiesi F, Jackson EK, et al. Estradiol stimulates capillary formation by human endothelial progenitor cells: role of estrogen receptor-alpha/beta, heme oxygenase 1, and tyrosine kinase. Hypertension. 2010; 56:397–404. [PubMed: 20644008]46?. Bolego C, Rossoni G, Fadini GP, et al. Selective estrogen receptor-alpha agonist provides widespread heart and vascular protection with enhanced endothelial progenitor cell mobilization in the absence of uterotrophic action. FASEB J. 2010; 24:2262–2272. New mechanisms that may be responsible for the cardioprotective action of estrogen. [PubMed: 20203089]47. Grodstein F, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and mortality. N Engl J Med. 1997; 336:1769–1775. [PubMed: 9187066]

48. Manson JE, Allison MA, Rossouw JE, et al. Estrogen therapy and coronary-artery calcification. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356:2591–2602. [PubMed: 17582069]

49. Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007; 297:1465–1477.

[PubMed: 17405972]

50. Clarkson TB, Anthony MS, Morgan TM. Inhibition of postmenopausal atherosclerosis

progression: a comparison of the effects of conjugated equine estrogens and soy phytoestrogens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001; 86:41–47. [PubMed: 11231976]

51. Nuedling S, Kahlert S, Loebbert K, et al. Differential effects of 17beta-estradiol on mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in rat cardiomyocytes. FEBS Lett. 1999; 454:271–276.

[PubMed: 10431821]

52. Yasui T, Maegawa M, Tomita J, et al. Changes in serum cytokine concentrations during the menopausal transition. Maturitas. 2007; 56:396–403. [PubMed: 17164077]

53?. Georgiadou P, Sbarouni E. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on inflammatory biomarkers.

Adv Clin Chem. 2009; 47:59–93. A comprehensive review outlines the effects of HRT on inflammatory biomarkers. [PubMed: 19634777]

54. Oztas E, Kurtay G. Effects of raloxifene on serum macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-18 levels in postmenopausal women younger than 60 years. Menopause. 2010;17:1188–1193. [PubMed: 20613670]

55. Karim R, Stanczyk FZ, Hodis HN, et al. Associations between markers of inflammation and physiological and pharmacological levels of circulating sex hormones in postmenopausal women.Menopause. 2010; 17:785–790. [PubMed: 20632462]

56. Kamada M, Irahara M, Maegawa M, et al. Postmenopausal changes in serum cytokine levels and hormone replacement therapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001; 184:309–314. [PubMed: 11228479]NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

57. Alexandersen P, Tankó LB, Bagger YZ, et al. The long-term impact of 2–3 years of hormone replacement therapy on cardiovascular mortality and atherosclerosis in healthy women.Climacteric. 2006; 9:108–118. [PubMed: 16698657]58. Klaiber EL, Broverman DM, Vogel W, et al. Relationships of serum estradiol levels, menopausal duration, and mood during hormonal replacement therapy. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1997;22:549–558. [PubMed: 9373888]59. Genant HK, Lucas J, Weiss S, et al. Low-dose esterified estrogen therapy: effects on bone, plasma estradiol concentrations, endometrium, and lipid levels. Estratab/Osteoporosis Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1997; 157:2609–2615. [PubMed: 9531230]60?. Villa P, Suriano R, Ricciardi L, et al. Low-dose estrogen and drospirenone combination: effects on glycoinsulinemic metabolism and other cardiovascular risk factors in healthy postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 2010 [Epub ahead of print]. A new study showing low-dose estrogen plus/drospirenone induced favorable changes in lipid profile improvement of vascular reactivity.61. Appt SE, Clarkson TB, Lees CJ, Anthony MS. Low dose estrogens inhibit coronary artery atherosclerosis in postmenopausal monkeys. Maturitas. 2006; 55:187–194. [PubMed: 16574351]62?. Zhan E, Keimig T, Xu J, et al. Dose-dependent cardiac effect of oestrogen replacement in mice postmyocardial infarction. Exp Physiol. 2008; 93:982–993. In mice with myocardial infarction,low dose of estradiol that restored plasma estrogen close to physiological levels tended to improve cardiac function and remodeling. At an increased dose, estradiol exacerbated cardiac fibrosis, hypertrophy, dysfunction and dilatation. [PubMed: 18487314]63??. Meng X, Dai X, Liao T-D, et al. Dose-dependent toxic effects of high-dose estrogen on renal and cardiac injury in surgically postmenopausal mice. Life Sci. 2010 [Epub ahead of print]. A mouse study showing that excessive dose of estradiol that raises uterine weight beyond physiological levels adversely affects the kidney even before it damages the heart.64. Wakatsuki A, Okatani Y, Ikenoue N, Fukaya T. Effect of medroxyprogesterone acetate on endothelium-dependent vasodilation in postmenopausal women receiving estrogen. Circulation.2001; 104:1773–1778. [PubMed: 11591613]65. Adams MR, Register TC, Golden DL, et al. Medroxyprogesterone acetate antagonizes inhibitory effects of conjugated equine estrogens on coronary artery atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb

Vasc Biol. 1997; 17:217–221. [PubMed: 9012659]

66. Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in

postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004; 291:1701–1712. [PubMed: 15082697]

67??. Miller VM, Black DM, Brinton EA, et al. Using basic science to design a clinical trial: baseline

characteristics of women enrolled in the Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study (KEEPS). J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2009; 2:228–239. An ongoing prospective, randomized, controlled trial designed to test the hypothesis that HRT when initiated early in menopause reduces progression of atherosclerosis. [PubMed: 19668346]

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

Figure 1. Possible mechanisms responsible for estrogen-mediated vasodilatation, renal and

cardiovascular protection

The multifaceted mechanisms of estrogen involve (a) acting on estrogen receptor-α (ERα)

and ERβ to reduce synthesis of NADPH oxidase and increase synthesis of endothelial nitric

oxide synthase (eNOS) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), thereby decreasing superoxide and

increasing NO production and bioavailability (genomic effect); (b) rapidly activating eNOS

via a calcium-mediated mechanism(s) without altering gene expression (nongenomic effect),

leading to NO/cGMP release and vascular relaxation; (c) activating Akt via MAP kinase

(MAPK)–PI3 kinase (PI3K) pathways, reducing apoptosis and enhancing cell survival and

(d) reducing NF-κB activation/translocation via p38α-mediated p53 phosphorylation and

JNK1/2-mediated signaling pathways, inhibiting chemokine/cytokine transcription and

decreasing inflammation. In addition, estrogen acts on the membrane-bound and G-protein-

coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) GPR30 associated with transactivation of epidermal

growth factor receptors, which induces rapid signal transduction, including activation of

MAPK, protein kinase A (PKA) and PI3K, leading to cardiovascular protection. NIH-PA Author Manuscript

NIH-PA Author Manuscript

常用心血管疾病治疗药物 虽然目前治疗心血管疾病的方法越来越多,但是药物治疗仍然是基础治疗、最为重要和首选的方法之一。不仅仅要求医生,患者本人以及家属也要熟悉常用的心血管疾病用药的知识,如药理作用、适应症、禁忌症、毒副作用及应用注意事项等。 治疗心血管疾病常用药物,常按药物作用机制进行大的分类,如血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂(ACEI)类、血管紧张素受体拮抗剂(ARB)类、β-阻滞剂、硝酸酯类、利尿剂、α-阻滞剂、强心药及洋地黄类、调血脂药物、抗心律失常药、钙通道阻滞剂、心肌营养药等。也有按具体疾病的治疗药物选择进行分类,如降血压药物、治疗冠心病药物、治疗心功能不全药物、抗凝抗栓药物等,不同分类各有其优点,这就要求临床医师对药、对病都要掌握,在诊疗指南的框架内,个体化治疗,最终实现治病、“救人”的目的。下面根据药理作用机制的异同,重点介绍主要的药物。 一、血管扩张剂 血管扩张剂是现代心血管病治疗学的基础,该类药物通过各种机制最终导致动脉和/或静脉扩张,降低体、肺循环血管阻力,降低心脏负荷,改善血流动力学效应,不仅广泛用于治疗原发性或继发性高血压和肺动脉高压,也是治疗心力衰竭、休克和改善脏器微循环的重要措施。不少血管扩张剂能直接扩张冠脉,增加冠脉血流量,改善心肌供氧,是治疗冠心病心绞痛和心肌梗死的良药。根据其作用机制不同,大致可分为以下几类:①直接作用的血管扩张剂;②α肾上腺素能受体阻滞剂;③影响肾素一血管紧张素一醛固酮系统(RAAS)的药物。 ④其他具有扩张血管作用的药物如钙离子拮抗剂、β-阻滞剂等。 ●直接作用的血管扩张剂 本类药物主要包括硝酸酯类、硝普钠和肼酞嗪(肼苯哒嗪)类及其他药物,分述如下: (一)硝酸酯类

第五部分心血管系统疾病 一、是非题 1.动脉粥样硬化的病变发生在大、中型动脉。( ) 2.急性风湿性心脏病时瓣膜上赘生物容易脱落引起栓塞。( ) 3.风湿性心肌炎时在心肌间质有风湿小体形成。( ) 4.高血压性肾萎缩称原发性肾萎缩。( ) 6.亚急性细菌性心内膜炎常发生在已有病变的瓣膜上。( ) 6.风湿性关节炎反复发作也可以导致关节畸形。( ) 7.二尖瓣狭窄也可引起左、右房室扩张肥大。( ) 8.风湿病是一种由A组溶血性链球菌直接引起的疾病,常累及全身结缔组织。( ) 9.高血压主要引起全身大、中动脉硬化。( ) 10.凡是血压超过140/90mmHg者,统称高血压。( ) 11.特发性高血压就是高血压病。( ) 12.主动脉狭窄可引起左心室向心性肥大。( ) 13.亚急性细菌性心内膜炎之赘生物脱落后可引起栓塞性小脓肿。( ) 14.高血压脑溢血常发生于内囊部。( ) 15.二尖瓣狭窄病人心脏病变以左室肥大为主。( ) 16.急性风心病时瓣膜上的疣状赘生物实质上是析出性血检。 17.低密度脂蛋白(LDL)与动脉粥样硬化症的发生密切相关。 18.亚急性细菌性心内膜炎常发生在已有病变的瓣膜上。 19.高血压主要累及病人的细小动脉。( ) 20.风湿性心包炎形成绒毛心,纤维素在心包脏壁两层间形成粘连而导致缩心包炎。( ) 21.风湿病是链球菌直接引起的炎症性疾病。( ) 22.二尖瓣瓣膜病和高血压病时可导致淤血而引起右心衰竭。( ) 23.风湿性心内膜炎赘生物易脱落引起栓塞。( ) 二、填空题 1.风湿病的基本病变分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 三个期。 2.心肌梗死的原因_________ 。 3.粥样斑块的继发性变化有_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 。 4.高血压常见死因有_________ 、_________ 、_________ 。 5.心肌梗死的合并症及后果可能为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 。 6.动脉粥样硬化症根据病变发展经过可分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 。 7.心肌梗死最常累及的病变分为_________ 及_________ 。 8.心肌梗死的继发改变有_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 。 9.动脉粥样硬化的基本病变分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 和_________ 四个时期。 10.风心病最常受累的瓣膜是_________ ,其次是_________ 。 11.可使左心室壁增厚的心脏病有_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 等。 12.根据动脉粥样硬化斑块的形成和发展将其分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 五个时期。 13.高血压可分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 三个时期。 14.动脉粥样硬化主要累及的血管是_________。其基本病变可分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 和

心血管疾病 实况报道第317号 2013年3月 重要事实 ?心血管疾病是全球的头号死因:每年死于心血管疾病的人数多于任何其它死因 (1)。 ?估计在2008年有1730万人死于心血管疾病,占全球死亡总数的30%(1)。这些死者中,估计730万人死于冠心病,620万人死于中风(2)。 ?低收入和中等收入国家受到的影响尤甚:超过80%的心血管疾病死亡发生在低收入和中等收入国家,男性和女性的情况几尽相同(1)。 ?到2030年,死于心血管疾病(主要是心脏病和中风)的人数将增加至2330万人(1,3)。预计心血管疾病将继续成为单个首要死因(3)。 ?大多数心血管疾病都可以通过解决诸如烟草使用、不健康饮食和肥胖、缺乏身体活动、高血压、糖尿病和血脂升高等危险因素而得到预防。 ?每年有940万例死亡,或所有死亡数的16.5%可能由高血压造成(4)。这包括51%因中风造成的死亡以及45%因冠心病造成的死亡(5)。

什么是心血管疾病? 心血管疾病是一组心脏和血管疾患,包括: ?冠心病——心肌供血血管的疾病 ?脑血管疾病——大脑供血血管的疾病 ?周围末梢动脉血管疾病——手臂和腿部供血血管的疾病 ?风湿性心脏病——由链球菌造成的风湿热对心肌和心脏瓣膜的损害 ?先天性心脏病——出生时存在的心脏结构畸形 ?深静脉血栓和肺栓塞——腿部静脉出现血块,它可脱落并移动至心脏和肺部。 心脏病发作和中风通常属于急症,主要是由于堵塞导致血液不能流入心脏或大脑。这种情况发生的最常见原因是在心脏或脑部供血血管内壁上堆积有脂肪层。中风也可能是因脑血管或血栓出血造成。 罹患心血管疾病的危险因素是什么? 心脏病和中风的最重要行为危险因素是不健康的饮食、缺乏身体活动、使用烟草和有害使用酒精。行为危险因素引发大约80%的冠心病和脑血管疾病(1)。 不健康饮食和缺乏身体活动造成的影响在个体中可能表现为血压、血糖和血脂的升高,以及超重和肥胖;这些“间接危险因素”可在初级保健机构得到衡量,它表明出现心脏病发作、中风、心衰和其它并发症的危险有所上升。 已经证明,停止使用烟草、减少膳食盐含量、使用水果蔬菜、有规律进行身体锻炼以及避免有害使用酒精可降低罹患心血管疾病的危险。通过预防或治疗高血压、糖尿病和血脂升高,也可降低心血管疾病的危险。 一些政策可创造出有利环境,使人们能够承担并可得到健康的选择。这些政策对鼓动人们采用健康行为并加以保持是必不可少的。 心血管疾病还有一些潜在的决定因素,或“起因的起因”。它们体现出推动社会、经济和文化变革的主要力量——全球化、城市化和人口老龄化。心血管疾病的其它决定因素包括贫穷、压力,以及遗传因素。 心血管疾病的共同症状是什么? 心脏病和中风的症状 潜在的血管病通常没有症状。心脏病发作或中风可能是潜在疾病的最初警告。心脏病发作的症状包括:

第九章心血管系统常见疾病的药物治疗 本章学习目标 一、掌握 1.高血压病的治疗目标,主要降压药物的种类、适应证及代表药物 2.高脂血症的治疗目标,他汀类药物的药理作用和临床应用 二、熟悉 1.高血压治疗的个体化原则; 2.心衰的治疗药物原则 二、了解 1.降压药物的选择 2.心力衰竭的治疗药物种类 本章主要介绍三个内容: 一、高血压病的药物治疗 二、高脂血症的药物治疗 三、充血性心力衰竭的药物治疗 本章重点掌握: 第一节高血压病的药物治疗 高血压是最常见的心血管疾病之一。高血压是导致脑卒中、导致伴有心肌梗死和冠心病的心血管疾病危险因素之一。 随着人口老龄化,如不有效地对血压进行预防性监测,高血压患者的数量将会进一步增加。Framingham心脏研究提出,在55岁血压正常的人群中,有90%的可能性发展为高血压。高血压和心血管疾病(Cardiovascular Disease,CVD)事件危险性之间的关系连续一致,持续存在,并独立于其它的危险因素。

心血管疾病主要危险因素包括:高血压、吸烟、肥胖、缺乏体力活动、血脂紊乱、糖尿病、早发心血管疾病家族史等 (一)药物治疗目标 抗高血压治疗的最终目标是减少心脑血管和肾脏疾病的发生率和死亡率。多数高血压患者,特别是50岁以上者,收缩压(SBP)达标时,舒张压(DBP)也会达标,治疗重点应放在SBP达标上。血压达到<140/90 mm Hg能减少心血管疾病(CVD)并发症。有糖尿病或肾病的高血压患者,降压目标是<130/80 mm Hg。 (二)生活方式调整 健康的生活方式对预防高血压非常重要,是治疗高血压必不可少的部分。降低血压的主要生活方式调整包括:超重和肥胖者应减轻体重;采用终止高血压膳食疗法,即提倡富含钾和钙的饮食方法;减少钠的摄入;增加体力活动;限制饮酒。调整生活方式能降低血压,提高降压药物的疗效,降低心血管危险。 (三)药物治疗 目前常用的降压药物可分为五大类,即利尿剂,肾上腺素受体阻滞剂,钙通道阻滞剂(CCB),血管紧张素转换酶抑制剂(ACEI)和血管紧张素Ⅱ受体拮抗剂(ARB)。 1.利尿剂 (1)分类:包括①噻嗪类:氢氯噻嗪、甲氯噻嗪、多噻嗪、吲达帕胺;②袢利尿药:呋塞米、托尔塞米和布美他尼;③保钾利尿药:螺内酯、氨苯蝶啶和阿米洛利。 (2)适应证:适用于轻、中度高血压。对盐敏感高血压,合并肥胖或糖尿病,更年期妇女和老年人高血压有较强的降压效应。袢利尿剂主要用于肾功能不全时。利尿剂能增强其它降压药的疗效。 (3)不良反应:一般利尿剂的不良反应是低血钾症和影响血脂、血糖和血尿酸代谢,往往发生在大剂量时。其它不良反应主要是乏力及尿量增多。 (4)禁忌证:痛风者禁用。保钾利尿剂可引起高血钾。肾功能不全者禁用。 2.肾上腺素受体阻滞剂 (1)分类:包括: ①α受体阻滞剂:哌唑嗪、多沙唑嗪、特拉唑嗪、酚妥拉明、妥拉唑林和乌拉地尔;

心血管系统疾病 动脉粥样硬化(AS) (一)血管的病理变化——累及全身大中动脉。 1.脂纹 2.纤维斑块 3.粥样斑块 4.继发改变 肉眼镜下 脂纹早期。常见于主动脉后壁和分支的开口 处 大量吞噬脂质的泡沫细胞(巨噬细胞源性和肌源 性) 纤维斑块灰黄色斑块 表层——纤维结缔组织,并有玻璃样变。 深层——脂质、巨噬细胞,以及吞噬脂质的泡沫 细胞

粥样斑 块 明显隆起于动脉内膜表面的黄色 斑块 1)表层:瓷白色纤维帽 2)深层:粥糜样物质+胆固醇结晶 3)底部和边缘:肉芽组织增生、泡沫细胞和淋巴细胞 浸润 继发改变 ①斑块内出血; ②斑块脱落形成栓子,引起栓塞; ③斑块破裂溃疡形成,继发血栓形成,进而引起动脉管腔阻塞,发生梗死; ④钙盐沉积——钙化; ⑤动脉瘤形成和血管腔狭窄,进而发生动脉瘤破裂出血和器官缺血性病变 (二)心脏、肾脏和脑的病理变化——梗死! 1.心脏——心肌梗死(凝固性坏死) 表现为心绞痛和心肌梗死。50%发生于左冠状动脉前降支供血区(左心室前壁、心尖部和室间隔2/3)。肉眼:新鲜——不规则形;陈旧——灰白色瘢痕组织。 镜下——凝固性坏死。 2.肾脏——肾梗死 肉眼:新鲜——三角形,灰白色。 严重时可形成动脉粥样硬化性固缩肾,即表现为肾脏形成多数大的瘢痕凹陷,多个瘢痕使肾脏缩小。

镜下:贫血性梗死。 3.脑 (1)脑萎缩。 (2)脑软化:颞叶、内囊、豆状核和丘脑。 (3)脑出血:小动脉瘤,血压突然升高时破裂可引起。 原发性高血压 (一)血管——累及全身细小动脉,最常累及肾入球小动脉。 表现为细动脉硬化(玻璃样变)。 细动脉内皮下均匀红染的蛋白性物质沉积——细动脉管壁增厚、管腔狭窄、弹性下降和硬度增加。

心血管系统常见病试题 一、最佳选择题 1、高血压的并发症通常主要受累的脏器包括 A、心脏、脑、肾脏、肺与血管 B、心脏、肺、胰脏、眼与动脉 C、肾脏、脑、心脏、眼与胰脏 D、肾脏、眼、胃肠、脑与心脏 E、心脏、脑、肾脏、眼与血管 2、原发性高血压临床表现中错误的是 A、初期即有明显症状 B、诊断临界值是收缩压≥140mmHg和(或)舒张压≥90mmHg C、绝大多数原发性高血压属于缓进型 D、可出现靶器官损害的临床表现 E、约半数人测量血压后才偶然发现血压升高 3、下列症状不是高血压临床表现的是 A、头痛 B、头晕 C、口干 D、心悸 E、耳鸣 4、关于单纯性收缩期高血压正确的是 A、收缩压≥140舒张压<90 B、收缩压>140舒张压<90 C、收缩压>130舒张压<100 D、收缩压>130舒张压<90 E、收缩压≥130舒张压<90 5、抗高血压治疗的目标因人群而异,合并慢性肾病的高血压病人的血压应严格控制在 A、<120/70mmHg B、<125/70mmHg C、<140/90mmHg D、<135/80mmHg E、<135/85mmHg 6、男,68岁双侧肾动脉狭窄,有哮喘史,气短、心悸就诊,体征和实验结果为血压172/96mmHg血尿酸516mmol/L(正常180-440 mmol/L),血钾110mmol/L(正常25-100mmol/L)应该选哪个抗高血压药 A、氢氯噻嗪 B、替米沙坦 C、卡托普利 D、利血平

E、拉西地平 7、高血压治疗的目标叙述正确的是 A、血压降低至120/80mmHg以下 B、控制患者血压不再持续升高 C、迅速降低患者血压,以规避并发症带来的风险 D、将血压控制在120/80mmHg以下,最大限度地消除危险因素,保护重要脏器的正常功能不受影响 E、降压治疗方案除了必须有效控制血压,还应兼顾对糖代谢、脂代谢、尿酸代谢等多重危险因素的控制 8、以下抗高血压药物中,属于利尿药的是 A、缬沙坦 B、氨氯地平 C、维拉帕米 D、氨苯蝶啶 E、依那普利 9、以下有关高血压的药物治疗方案的叙述中,不正确的是 A、可采用两种或两种以上药物联合用药 B、药物治疗高血压时要考虑患者的合并症 C、采用最小有效剂量,使不良反应减至最小 D、首先选用血管扩张剂和中枢性抗高血压药 E、最好选用1天1次给药持续24小时降压的药品 10、长期应用哪类降压药物可能会引起男性乳房发育 A、氨氯地平 B、螺内酯 C、卡维地洛 D、依那普利 E、利血平 11、高血压合并消化性溃疡者宜不用 A、甲基多巴 B、利血平 C、硝苯地平 D、酚妥拉明 E、依那普利 12、以下降压药,属于中枢α-受体激动剂的是 A、利血平 B、可乐定 C、拉贝洛尔 D、卡托普利 E、特拉唑嗪

全面认识高血压 ——主讲人:祁阳县中医院心血管科主任、副教授周桃元 【主持人】世界心脏联盟将每年9月的最后一个星期日定为“世界心脏日”。5月17日是世界高血压日,今年的主题是“知晓你的高血压”。高血压是心脑血管病的主要危险因素。高血压,就在我们身边。我国高血压已突破3.3亿,其中1.38亿患者不知道自己患有高血。所以我们一起来全面认识高血压。今天我们请到了权威专家,来自祁阳县中医院心血管科的副教授周桃元主任,周主任您好。 [周桃元简介] 周桃元,男,1965年2月出生,汉族,中共党员,毕业于中医药大学,本科学历,科副主任医师,1989年7月参加工作,现任祁阳中医院心血管科主任,省中西医结合学会委员、省中医心血管科学会委员及永州心血管科学会委员。曾在湘雅医院进修心血管科一年,每年都参加国家级或省级学术会议2-3次,毕业后一直从事科临床工作,能熟练运用中西医结合理论诊治各种心血管科疾病及急危重症病人的救治。在国家级及省级刊物上发表医学论文十七篇。 [周主任] 主持人好,大家好。 【主持人】周主任,心血管病作为危害人类健康的“第一杀手”已波及全球,防治心血管病的关键是哪种疾病? [周主任] 是高血压病。高血压是威胁人类健康的隐形杀手!全世界每年有1200万人死于跟高血压有关的疾病。 ?每100个脑出血病人中有93人患高血压 ?每100个脑梗塞病人中有86人患高血压 ?每100个冠心病人中有50~70人患高血压。 【主持人】高血压总是悄无声息地损害我们的健康,早期患者并

无明显的不适感,因此高血压患者并不重视,我国的高血压现状怎样? [周主任] 我国高血压现状非常令人担忧,可以概括为:三高、三低、三误区。 三高:患病率高(11.26%);死亡率高(41%);致残率高。 三低:知晓率低(35.6%);治疗率低(17.1%);控制率(4.1%)。 三个误区:不愿意服药;不难受不服药;不按病情服药。 【主持人】什么是血压? [周主任]血液要想在全身流动就需要有压力,血压就是指血液在流动时对血管壁产生的压力。 【主持人】高血压表现多样化,有的毫无症状,甚至有的人一生都无症状。怎样知道自己患了高血压?高血压的标准是多少? [周主任] 诊断高血压时要确诊血压值,通常是用三次非同日同时的平均血压,也就是说测三天不同时辰的三个血压值,取其平均值。量血压时要注意在安静状态下,室温不要太高,也不能太低,一般在20C。左右,要以右手为准,取坐位,当然必要时可以测立位,甚至下肢血压。高血压病患者早期可以没有任何症状,偶于体检时发现血压升高,有些高血压病患者早期可有头痛、头昏、心悸、耳鸣等症状,少数患者则在出现心、脑、肾等并发症后才发现。高血压的诊断标准为收缩压≥140 mmHg或(和)舒压≥90mmHg。24小时动态血压测定:24小时平均血压≥130/80mmHg,白天≥135/85mmHg,夜间≥125/75mmHg. 血压高低与症状不成正比,有无症状都要常规测血压。 【主持人】哪些人易患高血压? [周主任]有以下情况的人,患高血压病的危险大:吸烟、饮酒过量、焦虑、不经常活动、肥胖、摄入盐和脂肪过多,胆固醇高,糖尿病患者、有高血压家族史。

心血管系统疾病病理习题 A型题 1.疣状赘生物是指 A.心内膜增生物 B.心内膜上的新生物 C.心瓣膜纤维化 D.心瓣膜上的附壁血栓 E.心瓣膜钙化 2.下列符合恶性高血压特征性病理变化的是 A.肾入球小动脉玻璃样变性 B.肾细动脉壁纤维素样坏死 C.肾动脉粥瘤 D.肾小球毛细血管内透明血栓 E.肾小球纤维化 3.关于动脉粥样硬化的描述,哪项是正确的 A.主动脉脂纹仅见于中年以上人群 B.粥瘤内泡沫细胞均来自单核细胞 C.脂纹以主动脉前壁多见 D.氧化低密度脂蛋白(ox-IDL)具

有细胞毒性 E.粥瘤内胶原由纤维母细胞产生 4.下述哪项符合限制性心肌病 A.心内膜及心内膜下心肌纤维化 B.心肌间质纤维化 C.心肌细胞呈旋涡状排列 D.心肌细胞变性坏死 E.心肌间质内淋巴细胞浸润 5.慢性风湿性瓣膜病常见的联合瓣膜损害是 A.二尖瓣和三尖瓣 B.二尖瓣与主动脉瓣 C.主动脉瓣与肺动脉瓣 D.主动脉瓣与三尖瓣 E.二尖瓣与肺动脉瓣 6.动脉粥样硬化最好发的部位是 A.主动脉 B.冠状动脉 C.肾动脉 D.脑动脉 E.四肢动脉 7.冠状动脉粥样硬化最好发的部位是

A.左总干 B.左前降支 C.左旋支 D.右总支 E.右回旋支 8.高血压病时,大动脉的病变常表现为 A.纤维蛋白样坏死 B.内膜弹力纤维增生 C.内膜粥样斑块形成 D.管壁玻璃样变 E.外膜滋养小血管炎 9.原发性良性高血压的基本病变是 A.细、小动脉痉挛 B.细、小动脉玻璃样变 C.细、小动脉纤维素样坏死 D.细、小动脉洋葱皮样改变 E.以上都不是 10.动脉粥样硬化最易合并动脉瘤形成的部位是 A.下肢动脉 B.肾动脉 C.腹主动脉

循环系统疾病常见症状 1、心源性呼吸困难:又称气促或气急,是病人在休息或较轻的体力活动中自我感觉到的呼吸异常。循环系统疾病引起呼吸困难最常见的病因是左心功能不全,也可见于右心功能不全,心包炎、心包压塞等。(1)劳力性呼吸困难:是最早出现也是病情较轻的一种。其特点是在体力活动时发生或加重,休息后缓解或消失。引起呼吸困难的体力活动如快步行走、上楼、一般速度步行、穿衣、洗漱等。 (2)夜间阵发性呼吸困难:常发生在夜间,于睡眠中突然憋醒,并被迫坐起或下床,开窗通风后症状才逐渐缓解。 (3)端坐呼吸:常为严重心功能不全的表现之一,病人平卧时有呼吸困难,常被迫采取坐位。 2、胸痛: 许多循环系统疾病可产生胸痛,常见的有各型心绞痛、急性心肌梗死、急性主A夹层动脉瘤、急性心包炎、心脏神经官能症。 典型心绞痛位于胸骨左,呈阵发性压榨样痛,于体力活动或情绪激动时诱发,休息后可缓解。 急性心肌梗死多是持续性剧痛,呈濒死感,伴心律、血压改变; 急性主A夹层动脉瘤病人可出现胸骨右或心前区撕裂样剧痛或烧灼痛.急性心包炎引起的疼痛可因呼吸或咳嗽而加剧; 心脏神经官能症也可出现心尖部针刺样疼痛,但与劳累、休息无关,且活动后减轻,常伴有神经衰弱症状。 3、心悸:是指病人自觉心跳或心慌伴心前区不适感。 最常见的病因为心律失常,如心动过速、心动过缓、早搏等。 也可因心脏搏动增强,如各种器质性心血管疾病心功能代偿期及全身性疾病,如甲亢、贫血、发热、低血糖反应等,以及心脏神经官能症所致。 此外,生理性因素如健康人剧烈运动,精神紧张或情绪激动,过量吸烟、饮酒,饮浓茶或咖啡。 应用某些药物如肾上腺素类、阿托品、氨茶碱等可引起心率加快,心肌收缩力增强而致心悸。

心血管疾病营养治疗原则 医学营养治疗(medical nutrition therapy,MNT)是心血管疾病综合防治的重要措施之一。营养治疗的目标是控制血脂、血压、血糖和体重,降低心血管疾病危险因素的同时,增加保护因素。鼓励内科医生自己开营养处方,或推荐病人去咨询临床营养师。对于心力衰竭(心衰)患者,营养师作为多学科小组(包括医师、心理医师、护士和药剂师)的成员,通过提供医学营养治疗对患者的预后有着积极的影响,对减少再入院和住院天数、提高对限制钠及液体摄入的依从性、提高生活质量等心衰患者的治疗目标具有重要作用。 营养治疗和咨询包括客观地营养评估、准确地营养诊断、科学地营养干预(包括营养教育)、全面地营养监测。推荐首次门诊的时间为 45- 90 min,第 2-6 次的随访时间为 30-60 min,建议每次都有临床营养师参与。从药物治疗开始前,就应进行饮食营养干预措施,并在整个药物治疗期间均持续进行膳食营养干预,以便提高疗效。 医学营养治疗计划需要 3-6 个月的时间。首先是行为干预,主要是降低饱和脂肪酸和反式脂肪酸的摄入量,即减少肉类食品、油炸油煎食品和糕点摄入;减少膳食钠的摄入量,清淡饮食,增加蔬菜和水果摄入量。其次是给予个体化的营养治疗膳食 6 周。在第 2 次随访时,需要对血脂、血压和血糖的变化进行评估,如有必要,可加强治疗。 第 2 次随访时可指导患者学习有关辅助降脂膳食成分(如植物甾醇和膳食纤维)知识,增加膳食中的钾、镁、钙的摄入量,此阶段需对患者的饮食依从性进行监控。在第 3 次随访时,如果血脂或血压没有达到目标水平,则开始代谢综合征的治疗。当血脂已经大幅度下降时,应对代谢综合征或多种心血管病危险因素进行干预和管理。 校正多种危险因素的关键是增加运动,减少能量摄入和减轻体重。通过健康教育和营养咨询,帮助患者学会按膳食营养处方计划合理饮食、阅读食品营养标签、修改食谱、准备或采购健康的食物,以及外出就餐时合理饮食。 极低脂肪膳食有助于达到降脂目标。在二级预防中,这类膳食也可以辅助药物治疗。这类饮食含有最低限度的动物食品,饱和脂肪酸 (<30/0)、胆固醇(<5 mg/d) 以及总脂肪(<10%) 的摄入量均非常低,该类膳食主要食用低脂肪的谷物、豆类、蔬菜、水果、蛋清和脱脂乳制品,通常称之为奶蛋素食疗法。对于有他汀类药物禁忌证的患者可以选择极低脂肪膳食进行治疗,或由临床医师根据病情选择。 (一)总原则 1.食物多样化,粗细搭配,平衡膳食。 2.总能量摄入与身体活动要平衡:保持健康体重,BMI 在 18.5-<24.0 kg/m2。 3.低脂肪、低饱和脂肪膳食:膳食中脂肪提供的能量不超过总能量的 30%,其中饱和脂肪酸不超过总能量的 10%,尽量减少摄入肥肉、肉类食品和奶油,尽量不用椰子油和棕榈油。每日烹调油用量控制在 20 -30 g。

上篇第一章心血管系统疾病一、选择题 【A1型题】 1.风湿病侵犯的组织最确切的是在 A.心内膜 B.关节滑膜 C.血管 D.皮肤 E.全身结缔组织 2.在风湿病侵犯的器官中,病变最多见且严重的是 A.心脏 B.关节 C.血管 D.皮肤 E.脑 3.风湿病最具特征的病理变化是 A.粘液样变性 B.纤维蛋白样坏死 C.风湿小体 D.心瓣膜纤维组织增生 E.心外膜纤维蛋白渗出 4.风湿性心外膜炎病变是 A.变质性炎 B.化脓性炎 C.浆液纤维蛋白性炎 D.出血性炎 E.卡他性炎 5.风湿性心肌炎的特征病变是 A.心肌细胞变性、坏死 B.心肌间质水肿 C.间质弥漫性淋巴细胞浸润 D.间质多灶性中性粒细胞浸润 E.间质中出现风湿小体 6.风湿性心外膜炎常出现绒毛心,其原因是 A.纤维蛋白性炎 B.间皮细胞绒毛状增生 C.白色血栓 D.风湿小体 E.心外膜瘢痕形成 7.浆膜风湿病的病变特征是 A.粘液样变性 B.纤维蛋白样坏死 C.风湿小体 D.浆液渗出 E.浆液渗出及纤维蛋白形成 8.风湿性心内膜炎最常侵犯下述何处内膜组织 A.心瓣膜 B.腱索 C.左房心 D.右心房 E.左心室 9.风湿性心内膜炎除最常侵犯二尖瓣外,其次受累的内膜组织是 A.主动脉瓣 B.二尖瓣和主动脉瓣同时受累 C.腱索 D.左心房壁 E.左心室壁 10.早期风湿性心内膜炎最特征性的病变是在瓣膜上形成 A.溃疡 B.水肿 C.穿孔 D.串珠状疣状赘生物 E.巨大赘生物 11.慢性风湿性心瓣膜病之联合瓣膜损害,主要是 A.二尖瓣及三尖瓣 B.二尖瓣及主动脉瓣 C.主动脉瓣及肺动脉瓣 D.主动脉瓣及三尖瓣 E.二尖瓣、三尖瓣、主动脉瓣及肺动脉瓣 12.急性风湿性心内膜炎导致瓣膜狭窄或关闭不全的关键是 A.病变广泛 B.病变持续时间长 C.病变贯穿瓣膜 D.两瓣叶之间出现病变 E.病变反复发作

二、判断改错题 1.凡是血压超过140/90mmHg者,统称高血压。( ) 2.高血压主要累及病人的细小动脉。 ( ) 3.高血压性肾萎缩称原发性肾萎缩。( ) 4.高血压主要引起全身大、中动脉硬化。( ) 5.高血压脑溢血常发生于内囊部。( ) 6.特发性高血压就是高血压病。( ) 7.动脉粥样硬化的病变发生在细、小动脉。( ) 8.低密度脂蛋白(LDL)与动脉粥样硬化症的发生密切相关。 9.心肌梗死常发生于左室前壁、心尖部及室间隔前2/3, 即左冠状动脉左旋支供血区。( ) 10.急性风湿性心脏病时瓣膜上赘生物容易脱落引起栓塞。( ) 11.急性风心病时瓣膜上的疣状赘生物本质上是白色血栓。 12.风湿性心包炎形成绒毛心,纤维素在心包脏壁两层间形成粘连而导致缩窄性心包炎。( ) 13.风湿性心肌炎时在心肌间质有风湿小体形成。( ) 14.风湿性心内膜炎赘生物易脱落引起栓塞。( ) 15.风湿性关节炎反复发作也可以导致关节畸形。( ) 16.风湿病是链球菌直接引起的炎症性疾病。( ) 17.风湿病是一种由A组溶血性链球菌直接引起的疾病,常累及全身结缔组织。( ) 18.二尖瓣狭窄病人心脏病变以左室肥大为主。( ) 19.主动脉狭窄可引起左心室向心性肥大。( ) 20.亚急性细菌性心内膜炎之赘生物脱落后可引起栓塞性小脓肿。( ) 21.亚急性细菌性心内膜炎常发生在正常的瓣膜上 22.二尖瓣狭窄也可引起左、右房室扩张肥大。( ) 23.二尖瓣瓣膜病和高血压病时可导致淤血而引起右心衰竭。( ) 三、填空题 1.高血压常见死因有_________ 、_________ 、_________ 。 2.高血压可分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 三个时期。 3.恶性高血压病的特征性病变是_________和_________,主要累及_________。 4.引起颗粒性固缩肾的疾病主要是_________ 、和_________。 5 动脉粥样硬化的基本病变可分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 四个时期。 6.动脉粥样硬化斑块的继发性变化有_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 。 7.动脉粥样硬化症病变主要累及_________ 动脉,而高血压的病变主要累及 _________ 动脉。 8.心肌梗死的原因_________ 。 9.心肌梗死的合并症及后果可能为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 。 10.心肌梗死最常累及的病变分为 _________ 及_________ 。 11.风心病最常受累的瓣膜是 _________ ,其次是_________ 。 12.风湿病按病变过程可分为_________ 、_________ 、_________ 三期。变质性病变以_________ 为特征;增生性病变以 _________ 为特征。 13.风湿病的皮肤病变为_________和_________,前者为_________性病变,后者为_________性病变。 14.可使左心室壁增厚的心脏病有_________ 、_________ 、_________ 、_________ 等。 四、名词解释 1.高血压 2.高血压脑病 3.冠心病(Coronary heart disease)

---------------------------------------------------------------最新资料推荐------------------------------------------------------ 心血管系统疾病之病理学多选题 一、单项选择题(A 型题) 280.* 对人体造成最严重后果的风湿病(rheumatism)病变发生在( ) A.关节 D.心脏B.血管 E.脑 C.皮肤 281.* 在对风湿病进行有关的描述中,错误的提法是( ) A.属于变态反应性疾病B.发病与溶血性链球菌感染有关 C.以心脏病变的后果最为严重 D.风湿性关节炎常可导致关节畸形 E.皮下结节和环形红斑有助于临床诊断282.风湿性心脏病(rheumatic heart disease)最常累及的瓣膜是( ) A.二尖瓣 D.肺动脉瓣 B.三尖瓣 E.二尖瓣和主动脉瓣 C.主动脉瓣283.* 对风湿性心脏病最具有诊断意义的病变是( ) A.心肌变性、坏死 D.风湿小体 B.纤维蛋白性心外膜炎E.心肌间质炎细胞浸润 C.心瓣膜赘生物284.* 麦氏(McCallam)斑常见于( ) A.左心室 D.右心房 B.左心房 E.升主动脉 C.右心室 285.慢性风湿性瓣膜病最常见的联合瓣膜病变是( ) A.二尖瓣和三尖瓣 D.三尖瓣和肺动脉瓣 B.二尖瓣和主动脉瓣 E.主动脉瓣和肺动脉瓣 C.三尖瓣和主动脉瓣 286.* 急性风湿病最常见的致死原因是( ) A.风湿性心外膜炎 D.风湿性脑动脉炎B.风湿性心内膜炎 E.动脉系统栓塞 C.风湿性心肌炎287.慢性风湿性心瓣膜病一般没有( ) A.瓣膜增厚变硬 1 / 11

心血管系统常见疾病 心源性呼吸困难: 1、气体交换受损:与肺淤血、肺水肿或体循环淤血有关 2、活动无耐力:与缺氧有关 心前区疼痛: 1、疼痛:心前疼痛,与冠状动脉供血不足导致心肌缺血,缺氧或炎症累及心包有关。 心悸: 1、不舒适:心悸:与心律失常心脏搏动增强有关。 心源性水肿: 1、体液过多:与体循环淤血及钠、水潴留有关。 2、有皮肤完整性受损的危险:与水肿、卧床过久。营养不良有关。 晕厥(心源性): 1、有受伤的危险:与晕厥发作有关。 2、心输出量减少:与严重心律失常,心肌收缩力减弱,主动脉瓣狭窄有关。 慢性心力衰竭: 1、活动无耐力:与心功能不全,心排出量下降有关。 2、气体交换受损:与左心衰竭致肺淤血,右心衰竭致体循环淤血有关。 3、体液过多:与右心衰竭致体循环淤血,肾血流灌注不足,钠水潴留有关。 急性心力衰竭: 1、气体交换受损:与急性肺水肿影响气体交换有关。 2、焦虑、恐惧:与病程长、丧失劳动能力和突发的病情加重致极度呼吸困难及窒息等,监护室的抢救设施和抢救时的紧张气氛对病人的影响有关。 3、清理呼吸道无效:与肺淤血呼吸道内大量泡沫痰有关。 4、潜在并发症:心源性休克,呼吸道感染,下肢静脉血栓形成。 心律失常: 1、活动无耐力:与心律失常导致心排出量减少有关。 2、焦虑:与严重心律失常至心跳不规则,心律失常反复发作和疗效不佳。缺乏心律失常的相关知识有关。 3、有受伤的危险:与心律失常导致的晕厥有关。 4、潜在并发症:心绞痛、脑栓塞、猝死。

风湿性心瓣膜病: 1、活动无耐力:与心瓣膜病致心排血量降低有关。 2、焦虑:同上。 3、有感染的危险:与肺淤血及风湿活动有关。 4、知识缺乏:与对疾病缺乏认识有关。 5、潜在并发症:心力衰竭,心律失常,血栓栓塞,亚急性感染性心内膜炎,风湿活动。 心绞痛: 1、疼痛:心前区疼痛与冠状动脉供血不足,导致心肌缺血、缺氧,乳酸及代谢产物积聚、刺激神经末稍有关。 2、活动无耐力:与心绞痛的发作影响活动有关。 3、焦虑:与心前区疼痛及对预后的忧虑有关。 4、知识缺乏:与缺乏有关冠心病的知识有关。 5、潜在并发症:急性心肌梗死。 心肌梗死 1、疼痛:心前区疼痛与心肌血供急剧减少或中断,发生缺血性坏死有关。 2、活动无耐力:与心输出量减少引起全身氧供不足及卧床时间过久有关。 3、恐惧:与剧烈胸痛产生濒死导致病人怀疑自己生存危机,及监护室环境,创伤性抢救有关。 4、有便秘的危险:与不适应卧床排便,饮食少有关。 5、潜在并发症:心律失常、休克、猝死、深静脉血栓形成。肺部感染。 病毒性心肌炎 1、活动无耐力:与心肌细胞受损有关。 2、疼痛:心前区疼痛与心肌受损有关。 3、焦虑:与感到疾病的威胁有关。 4、潜在并发症:心力衰竭、心律失常。 急性心包炎 1、疼痛:心前区疼痛:与心包纤维蛋白性炎症有关。 2、气体交换受损:与肺淤血及肺组织受损有关。 3、心排出量减少:与大量心包积液妨碍心室舒张充盈有关。 4、体温过度:与感染有关。 5、焦虑:与住院影响工作,生活及病情重有关。 缩窄性心包炎 1、活动无耐力:与心排出量不足有关。 2、体液过多:与体循环淤血有关。 原发性心肌病 1、气体交换受损:与心力衰竭有关。 2、疼痛:胸痛与心肌耗氧量增加,冠状动脉供血不足有关。 3、活动无耐力:与心肌病变使心肌收缩力减弱,心排出量减少(与心脏功能下降)有关。 4、体液过多:与心力衰竭有关。

临床治疗心血管疾病常用药物药效分析 目的对临床上治疗心血管病常用药物的药效进行分析,为临床合理用药提供参考依据。方法选取我院2014年~2015年收治心血管疾病患者隨机抽取50例作为研究对象,对其治疗用药情况进行统计和分析,并以药品日剂量(DDD)、总用药量、用药时间等已知条件计算用药频度(DDDs)和药物利用指数(DUI),以1.0为标准线,1.0及以下为合理用药,超过1.0则为不合理用药。根据患者治疗效果对药物疗效进行评估。结果我院临床治疗心血管疾病有12种常用药物,通过DUI指数评估,其中有10种药物DUI指数低于1.0,其余两种药物DUI指数在1.0以上。结论临床上对于心血管疾病的治疗,本着合理、安全用药的原则用药会获得显著的治疗效果,对于临床用药具有一定的指导意义。 标签:心血管疾病;临床;常用药物;药效 心血管疾病是威胁人类健康的常见疾病之一,多发于老年人群体。现今生活节奏加快,社会压力和生活压力不断增加,加上不良的生活习惯,心血管疾病呈现出年轻化的发展趋势。据资料显示,每年全球约有近两千万人死于心血管疾病,约占全球死亡总数的三分之一,心血管疾病已经成为全球疾病致死的头号死因。心血管疾病一旦发病会以很快的速度恶化,及时的药物治疗可以有效的控制心血管疾病的恶化速度,因此,安全用药、合理用药成为心血管疾病治疗的重点问题。现报告如下。 1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料 选取我院2014年~2015年收治心血管疾病患者随机抽取50例作为研究对象,对心血管疾病临床药物治疗进行研究和分析。此50例患者中,男29例,女21例,年龄22~84岁,平均(52.2±10.35)岁。病程1.5~25年,平均(10±5.3)年。患者均诊断为心血管疾病,临床上以药物治疗为主。 1.2 方法 對患者的病情程度、药品种类和名称、用药剂量和方法、用药时长以及药物不良反应进行归纳、总结和分析。以药品日剂量(DDD)、总用药量、用药时间等已知条件计算用药频度(DDDs)和药物利用指数(DUI),计算公式为:DDDS=用药总量/DDD,DUI=DDDs/用药总时间。以1.0为标准线,1.0及以下为合理用药,超过1.0则为不合理用药。 1.3 疗效判定指标 患者心血管疾病的临床症状表现完全消除,疗效可定为治愈;患者心血管疾病的临床症状表现虽存在但较治疗前有所缓解,疗效可定为好转;患者心血管疾

心血管系统疾病习题及 答案 Company number:【WTUT-WT88Y-W8BBGB-BWYTT-19998】

上篇第一章心血管系统疾病一、选择题 【A1型题】 1.风湿病侵犯的组织最确切的是在 A.心内膜 B.关节滑膜 C.血管 D.皮肤 E.全身结缔组织 2.在风湿病侵犯的器官中,病变最多见且严重的是 A.心脏 B.关节 C.血管 D.皮肤 E.脑 3.风湿病最具特征的病理变化是 A.粘液样变性 B.纤维蛋白样坏死 C.风湿小体 D.心瓣膜纤维组织增生 E.心外膜纤维蛋白渗出 4.风湿性心外膜炎病变是 A.变质性炎 B.化脓性炎 C.浆液纤维蛋白性炎 D.出血性炎 E.卡他性炎 5.风湿性心肌炎的特征病变是 A.心肌细胞变性、坏死 B.心肌间质水肿 C.间质弥漫性淋巴细胞浸润 D.间质多灶性中性粒细胞浸润 E.间质中出现风湿小体 6.风湿性心外膜炎常出现绒毛心,其原因是 A.纤维蛋白性炎 B.间皮细胞绒毛状增生 C.白色血栓 D.风湿小体 E.心外膜瘢痕形成 7.浆膜风湿病的病变特征是 A.粘液样变性 B.纤维蛋白样坏死 C.风湿小体 D.浆液渗出 E.浆液渗出及纤维蛋白形成 8.风湿性心内膜炎最常侵犯下述何处内膜组织 A.心瓣膜 B.腱索 C.左房心 D.右心房 E.左心室 9.风湿性心内膜炎除最常侵犯二尖瓣外,其次受累的内膜组织是 A.主动脉瓣 B.二尖瓣和主动脉瓣同时受累 C.腱索 D.左心房壁 E.左心室壁 10.早期风湿性心内膜炎最特征性的病变是在瓣膜上形成 A.溃疡 B.水肿 C.穿孔 D.串珠状疣状赘生物 E.巨大赘生物 11.慢性风湿性心瓣膜病之联合瓣膜损害,主要是 A.二尖瓣及三尖瓣 B.二尖瓣及主动脉瓣 C.主动脉瓣及肺动脉瓣 D.主动脉瓣及三尖瓣 E.二尖瓣、三尖瓣、主动脉瓣及肺动脉瓣 12.急性风湿性心内膜炎导致瓣膜狭窄或关闭不全的关键是

心血管疾病治疗方法 心脑血管疾病是一种严重威胁人类,特别是50岁以上中老年人健康的常见病,具有高患病率、高致残率和高死亡率的特点,即使应用目前最先进、完善的治疗手段,仍可有50%以上的脑血管意外幸存者生活不能完全自理,全世界每年死于心脑血管疾病的人数高达1500万人,居各种死因首位。以下是分享给大家的关于心血管疾病治疗方法,一起来看看吧! 1.保持心态平衡 冠心病、高血脂患者尤其要放宽胸怀,不要让情绪起伏太大。 2.适当运动 心脑血管患者要适当运动,运动量减少也会造成血流缓慢,血脂升高。要合理安排运动时间和控制好运动量。冬季要等太阳升起来之后再去锻炼,此时,温度回升,可避免机体突然受到寒冷刺激而发病。 3.控制危险因素 严格控制血压至理想水平,服用有效调脂药物,控制糖尿病,改善胰岛素抵抗和异常代谢状态,戒烟。 4.药物治疗 根据不同的心脑血管疾病,给予针对性的治疗药物,以缓解症状,改善预后,预防并发症。 5.外科治疗

通过外科手术或介入治疗,对出血部位进行止血,消除血肿,或改善缺血部位的供血。 6.康复治疗 患者病情平稳后,从简单的被动运动开始,逐步做主动运动,最终达到生活自理的目的。早期康复训练对脑血管疾病患者的功能恢复尤为重要。 保健心血管科常用药物李春梅整理 目录 (一) 抗高血压药 (二) 抗心绞痛药抗心律失常药 (三) 强心衰药 (四) 抗心绞痛药 (五) 抗血小板、抗凝药 (六) 降血脂药 (七) 改善循环药物 (八) 改善心肌代谢药物 ----------------------------------------------------------- 一、常用降压药 1. 利尿药 (1)噻嗪类利尿剂包括氢氯噻嗪(双氢克尿噻)、氯噻嗪 禁忌:痛风,低钠血症禁用;妊娠妇女不宜使用。 (2)袢利尿剂包括呋塞米(速尿)、托拉塞米(特苏尼)、布美他尼、

循环系统的常见疾病主要有:高血压及高血压病;冠心病及隐性冠心病、心绞痛、心肌梗死;心律失常与早博;心性猝死;心脏焦虑症等等。这些病也称为"心身疾病",因为其病因基本上是由于心因性因素诱发。这也可以说是内在因素起重要作用,而外来的因子是第二位的作用;如果内在因素稳定、强大,外来因子就起不了作用。 循环系统疾病的主要病理变化是高血压和动脉硬化,这两者相辅相成,高血压会促使、促进动脉硬化,而动脉硬化会使血压升高。高血压和动脉硬化是循环系统所有疾病的元凶。防止高血压的发生和对高血压病进行有效的治疗、预防、控制,也就会有效地控制了循环疾病的发生发展和预防。 高血压指的是一时性血压升高的生理现象,升高后很快能自行下降恢复常态。基本对人体没有造成损害。高血压病是一种病态,是生理性开始向病理性的转变,血压升高已呈持续稳定状态,不治疗不能下降,对机体组织、器官逐渐开始发生损害。最早的损害大多是隐袭的,更不易察觉,但确确实实是在潜移默化地在开始损害。 血压是测定动脉血管中的压力。动脉血管是一根富有弹性的肌性器官,弹性越好,舒张自如,管腔越光滑,血流的阻力越小,血压就能保持正常。此外,还有极其灵敏的-植物神经-反馈调控机制,进行调节。如果一旦管腔僵硬,管壁粗糙,调控失灵,血流阻力就会上升,血压随之升高。 高血压病人的血管日夜不停地遭受高压的冲击,日久管壁必然受到伤害,受损的首先是血管内膜,不仅会变得粗糙,同时血流中溶解的胆固醇会渗透、浸入血管壁而沉积。如果一个人的血脂,尤其是胆固醇,很高,那么就会有大量的胆固醇通过受损害的动脉内膜沉积到血管内膜下的中层,从而破坏了动脉中层的平滑肌和弹力纤维,血管的弹性就此下降、甚至丧失,僵硬。这就是动脉硬化。 硬化僵硬的血管难以舒张,进一步使血流阻力增大,舒张期的血压难以得到缓冲,舒张压就进一步上升,形成恶性循环。 这种受损的发生在心脑肾实质脏器内的动脉硬化,就是冠心病、中风的主要"罪魁祸首"。 动脉硬化后的血压升高主要表现在舒张压。收缩压的升高主要是由于小动脉的持久收缩/或小动脉痉挛。这与植物神经功能密切相关,与体内的内分泌活动,尤其是肾上腺皮质的分泌活动密切有关。这些变化与情绪密切相连。这有下面的两组资料为证: