法学外文翻译

- 格式:doc

- 大小:78.00 KB

- 文档页数:15

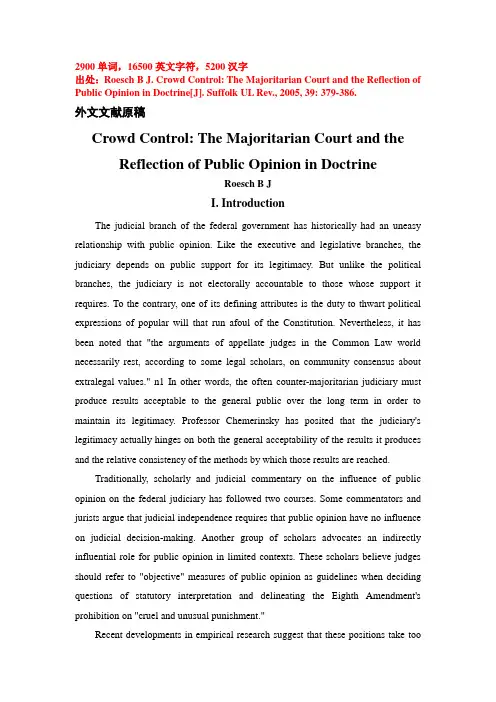

2900单词,16500英文字符,5200汉字出处:Roesch B J. Crowd Control: The Majoritarian Court and the Reflection of Public Opinion in Doctrine[J]. Suffolk UL Rev., 2005, 39: 379-386.外文文献原稿Crowd Control: The Majoritarian Court and the Reflection of Public Opinion in DoctrineRoesch B JI. IntroductionThe judicial branch of the federal government has historically had an uneasy relationship with public opinion. Like the executive and legislative branches, the judiciary depends on public support for its legitimacy. But unlike the political branches, the judiciary is not electorally accountable to those whose support it requires. To the contrary, one of its defining attributes is the duty to thwart political expressions of popular will that run afoul of the Constitution. Nevertheless, it has been noted that "the arguments of appellate judges in the Common Law world necessarily rest, according to some legal scholars, on community consensus about extralegal values." n1 In other words, the often counter-majoritarian judiciary must produce results acceptable to the general public over the long term in order to maintain its legitimacy. Professor Chemerinsky has posited that the judiciary's legitimacy actually hinges on both the general acceptability of the results it produces and the relative consistency of the methods by which those results are reached.Traditionally, scholarly and judicial commentary on the influence of public opinion on the federal judiciary has followed two courses. Some commentators and jurists argue that judicial independence requires that public opinion have no influence on judicial decision-making. Another group of scholars advocates an indirectly influential role for public opinion in limited contexts. These scholars believe judges should refer to "objective" measures of public opinion as guidelines when deciding questions of statutory interpretation and delineating the Eighth Amendment's prohibition on "cruel and unusual punishment."Recent developments in empirical research suggest that these positions take toolimited a view of public opinion as an influence on judicial decision-making. The research suggests that the "judicial isolation" model conflicts with reality-the influence of public opinion may be inevitable. This Article will examine this evidence, which suggests that many judges are influenced-at least marginally - by public opinion. Because the judiciary is the one branch of the federal government committed to a transparent decision-making process, this Article sets out to determine how public opinion affects the judicial decision-making process in various contexts. The mechanics of this apparent influence have significant consequences for how we conceive of the relationship between public opinion and judicial outcome and whether this apparent influence is in fact a threat to judicial independence.One might expect public opinion to exert its influence through the judiciary's interaction with the political branches into which democracy channels it, and it is to these interactions that this Article turns first in its inquiry into the mechanics of public opinion's apparent influence on judicial outcomes. But political controls, such as Congressional control over jurisdiction and budget, are blunt instruments. The political costs of threatening reprisal through these means for individual decisions make their use ineffective as a means to influence the judiciary on a case-by-case basis.Presidential refusal to execute the judiciary's rulings is a more precise-but rarely invoked-constraint. Formal political constraints ultimately fail to explain public opinion's influence on individual cases.The Article next turns to more informal influences on judicial decisions. These constraints include the role of stare decisis and the appellate process, as well as concerns about the jurist's individual reputation and that of the judiciary as a whole. Public opinion may reinforce several of these constraints, but seems to have most of its influence where these constraints leave jurists with discretion. Public opinion thus appears to operate in much the same sphere as the judge's own political ideology, which, according to the "attitudinal" model of judicial decision-making, the judge may promote within the scope of the discretion afforded by precedent.Because consideration of both formal and informal constraints and attitudinalmodels of decision-making yields unsatisfying answers, the Article turns from influences external to the judicial decision-making framework and examines the framework itself. In an attempt to understand the apparent influence of public opinion, this Article imagines what a principled incorporation of public opinion into the various analyses might look like. That is, the Article speculates what American jurisprudence would look like if public opinion were an explicit, rather than mysterious, influence on judicial outcomes, beginning with an examination of one case where the Court did consider public opinion polls as part of its legal analysis. This thought experiment ultimately suggests another explanation for the correlation of public opinion and judicial output.The Supreme Court's citation of opinion polls in Atkins v. Virginia n4 suggests that polls may be useful evidence of public opinion if public opinion had a legitimate place in legal analysis. The use of opinion polls as evidence of public opinion would expand the universe of issues about which there may be judicially knowable public opinion, and represent a significant step towards the potential principled incorporation of public opinion into judicial decision-making. Although the court's use of opinion polls was unfortunate because the polls were not subject to examination and criticism by expert witnesses in the trial court, polls are potentially important and powerful evidence of public opinion. The criticisms leveled at the court's use of opinion polls in Atkins, moreover, suggests that public opinion can be measured accurately enough to be of use to judges.The traditional "spectrum of deference" n5 suggests it is possible to make a reasoned evaluation of the appropriateness of public opinion as an influence in various judicial contexts. The spectrum is based on a realistic evaluation of the relative institutional advantages of the judiciary and Congress, and affords Congress varying degrees of deference depending on the various functions implicated by the decision-making context. Although the considerations are not identical when the question is the consideration of public opinion rather than deference to the will of a political branch, an examination of the values underlying our government and the judiciary's institutional abilities will illuminate when and how the judiciary mayreflect public opinion.For example, Professor Eskridge has argued that public values ought to and do influence the process of statutory interpretation. n6 Atkins suggests that public opinion, which may amount to something less than Eskridge's public values, might influence statutory interpretation depending on the strength of the preference and the strength of other traditional indicators of statutory meaning.Federal common law is another potential context for the consideration of public opinion. Although the common law does not always directly reflect public preferences, democratic principles suggest that public opinion could be relevant to determining common law rules. The common law context illuminates several instances where public opinion should not be considered-in most cases where the rule may affect the public's tax burden, or where public opinion is adverse to a minority or individual who does not enjoy constitutional protection related to the rule of law to be decided.Public opinion could also theoretically play a role in constitutional adjudication. Perhaps ironically, determining whether legislation is within Congress's power under the Interstate Commerce Clause - in which the Court grants Congress substantial deference - proves to be an inappropriate doctrine for incorporating public opinion. The reason is twofold. First, there is no reason to believe that the public has any inherent advantage over the judiciary in determining whether an activity substantially affects interstate commerce. Second, the Court's Commerce Clause jurisprudence serves merely to channel public opinion to the constitutionally appropriate decision-maker-a determination for which the popularity of the legislation in question seems irrelevant. Nevertheless, public opinion fits surprisingly well into other constitutional doctrines.The vindication of national opinion over a majority in a smaller constituency may justify consideration of public opinion in the Court's Fourteenth Amendment jurisprudence. Doctrinal developments in Lawrence v. Texas suggest that public opinion could become a legitimate and explicit consideration in the substantive due process arena. In the course of striking down Texas's law against homosexual sodomy only seventeen years after upholding the states' ability to prohibit such conduct inBowers v. Hardwick, the Lawrence Court engaged in analysis that bore striking similarities to its Eighth Amendment analysis in Atkins. The Lawrence Court thus pointed to a doctrinal place for public opinion in its substantive due process jurisprudence. Because similar developments have not occurred in the Court's equal protection jurisprudence, this Article reserves judgment regarding the fit of public opinion into equal protection doctrine.The examination of how public opinion might fit into various judicial doctrines suggests where and how public opinion may influence outcomes. In most instances, the correlation of public opinion and judicial outcomes is the result of the process by which judges routinely make decisions rather than an influence external to the decision-making process. This influence therefore need not be viewed as a threat to judicial independence. Current doctrine is, across the board, well designed to reflect public opinion.This Article proceeds as follows: Part II identifies several instances where there is agreement that public opinion must not play a role in judicial decision-making, and examines the competing judicial traditions regarding the role of public opinion in constitutional adjudication. Part III then surveys evidence that public opinion influences judicial decision-making, and concludes that public opinion may have a marginal effect. It next attempts to explain how this influence operates, but finds both political and informal intra-judicial constraints inadequate to account for public opinion's influence on the judiciary. Finally, it examines the use of opinion polls in Atkins to determine the meaning of "cruel and unusual punishment." Part IV examines judicial decisional tools themselves to explain the apparent effect of public opinion on judicial decision-making. It first outlines the traditional spectrum of deference, which serves as an example for the context-specific analysis of whether public opinion could be appropriate as a doctrinal consideration in various contexts. It next examines whether public opinion could be a legitimate consideration in various contexts, including statutory interpretation, common law-making, and several constitutional contexts. The Article concludes by examining the tendency of various doctrines to reflect public opinion, and the effect of recent jurisprudence on the publicopinion-mirroring ability of those doctrines.II. The Debate over Public Opinion in Judicial Decision-making A.Public Opinion as Anathema to Judicial IndependenceThere is widespread agreement that in certain cases, public opinion should not play any role in a judge's decision. For example, determinations of whether probable cause exists to try a defendant should not be influenced by public outcry that the defendant is guilty. n9 Nor should public animus influence individual sentencing decisions. n10 A recent example of these dangers is illuminating.In 1995, Federal District Judge Baer of the Southern District of New York presided over a high profile drug prosecution. After a hearing where Judge Baer found the testimony of defense witnesses credible and the testimony of police officers "incredible," he excluded large quantities of drugs and a confession, ruling that they were obtained in violation of the defendant's Fourth and Fifth Amendment rights.The public and political responses were immediate. The New York Times ran several editorials condemning the ruling. Members of Congress spoke publicly about impeachment, and some even asked President Clinton to add his voice to the criticism. In the meantime, Judge Baer granted a rehearing on the suppression motion. President Clinton declined to comment on the case pending the results of the rehearing. According to the New York Times, a group of Circuit Court judges, and several commentators, the message to Judge Baer was clear: reverse yourself, or risk losing your job, despite the convention against impeaching federal judges because of their decisions.After rehearing the motion, Judge Baer reversed his original decision and admitted the evidence, citing newly-introduced police reports as additional evidence that compelled him to change his mind. But critics claim that this additional evidence could not have been a sufficient ground for reversal, and may have even hurt the prosecution's case by creating additional inconsistencies with the officers' testimony. Judge Baer was in a no-win situation. There was negative publicity about his originaldecision to exclude the evidence, and there would be a negative public reaction to a change of position based on his decision to include the evidence-both of which could undermine public confidence in the impartial nature of the judiciary.The late Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote about the effects of public opinion on the judicial decision-making process, concluding that "no judge can conscientiously say in so many words, "I gave you my best judgment when I decided that the Constitution meant thus and so, but since the public overwhelmingly disagrees with my interpretation of the Constitution, I will therefore change my mind." On its face, this statement appears to reject public opinion as a consideration in constitutional adjudication, a position consistent with much of Rehnquist's jurisprudence.In these contexts, capitulation to contrary public opinion would signal the end of judicial independence. But a careful consideration of public opinion in certain cases does not necessarily indicate an erosion of judicial independence. Commentators and jurists have long acknowledged the influence of public opinion without concluding that the judiciary has abdicated its responsibility of independent judgment.B. Competing Judicial Views on the Propriety on Considering Public OpinionCommentators and jurists have long recognized the effect of public opinion on the judiciary in circumstances where it is not a threat to judicial independence. The Chief Justice Rehnquist, drawing on his experience as a law clerk to Justice Jackson, concluded that public opinion had a significant influence on the Court's disposition in the "Steel Seizure" case. In 1952, President Truman, fearing that a reduction in steel production would hinder the Korean War effort, ordered federal officials to seize and operate several steel production facilities during a strike. Steel companies brought suit and obtained an injunction from the district court enjoining the President from seizing the steel mills. The government obtained a stay from the court of appeals and appealed directly to the Supreme Court, which granted certiorari and heard arguments nine days later. The Court rejected the government's argument that the seizure was justified by certain powers given to the President under Article II of the Constitution.The timing of the government's "inherent power" argument was not good, as support for both the Korean War and President Truman was at its nadir. Chief JusticeRehnquist suggested that the tides of public opinion, accelerated and intensified by the rapid movement of the case through the federal judicial system, influenced the Court's decision.Acknowledging public opinion's influence and incorporating it into doctrine are separate propositions, however. Chief Justice Rehnquist repeatedly dissented from opinions taking public opinion into account, stating that public opinion was constitutionally irrelevant. Justice Scalia agreed with Rehnquist's theory, commenting on "how upsetting it is, that so many of our citizens...think that we Justices should properly take into account their views, as though we were engaged not in ascertaining an objective law but in determining some kind of social consensus."Chief Justice Rehnquist also drew considerable support for his position from a longstanding belief among the public that judges do not-and must not-consider public opinion in making decisions. Moreover, many jurists share this view of the judiciary and of their own work. Justice Douglas described judges as strong amid the winds of political change. Chief Justice Burger wrote that "legislatures, not courts, are constituted to respond to the will and consequently the moral values of the people." Justice Powell agreed, noting that "the assessment of popular opinion is essentially a legislative, not a judicial, function." Justice Frankfurter also wrote that courts are unlike representative bodies because they "are not designed to be a good reflex of a democratic society."Support for public opinion as a factor in judicial decision-making among U.S. Court of Appeals judges is mixed. Of thirty-five judges surveyed in 1981, only one responded that public opinion was "a very important" factor, while eight said that it was "moderately important" and twenty-two said that it was "not important." Judge Tacha of the Tenth Circuit declared that public opinion should have no influence whatsoever in articulating ideal judicial procedure.Justice Story wrote that "it is not for judges to listen to ... popular appeal." Chief Justice Taney also addressed the role of public opinion in Dred Scot v. Sanford, concluding that current public opinion was irrelevant to constitutional interpretation. Strictly denying the influence of public opinion is problematic in several respects,however. First, it does not appear to reflect reality. Evidence discussed below suggests that public opinion influences judicial decision-making, even if only at an unconscious level. Second, in some circumstances, public opinion could be a legitimate consideration for a policy-making court.There is also a tradition of recognizing public opinion in certain constitutional contexts. In Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, Justice Souter cited divided public opinion as a reason to uphold the central holding in Roe v. Wade. According to Justice Souter, the Court should refrain from reversing its watershed cases until substantial public opinion for the decision becomes unfavorable.Justice Souter's incorporation of public opinion into constitutional doctrine is also firmly grounded in judicial tradition. In 1812, the Court held in United States v. Hudson n43 that the federal courts lacked the power to make criminal common law. In the decision, Justice Johnson stated that although this question is brought up now for the first time to be decided by this Court, we consider it as having been long since settled in public opinion. In no other case for many years has this jurisdiction been asserted; and the general acquiescence of legal men shews the prevalence of opinion in favor of the negative of the proposition.外文文献翻译稿群体控制:多数主义法院与公共舆论的反思作者:本杰明·J·罗斯切1一、序言联邦国家机关的司法部门有史以来就与社会舆论有着令人不安的紧张关系。

国际法学英文English: International law is a body of rules and principles that govern the conduct of states and international organizations in their relations with one another. It serves as the foundation for stable and peaceful international relations, providing a framework for resolving disputes, protecting human rights, and regulating global activities such as trade and the environment. International law encompasses a wide range of legal instruments, including treaties, customary law, and the decisions of international courts and tribunals. It is a dynamic and evolving field, with new challenges and issues constantly emerging, such as cyber warfare, climate change, and the rights of refugees and migrants. The study of international law involves analyzing these complex legal issues and understanding how they intersect with political, economic, and social factors on a global scale.中文翻译: 国际法是规范国家和国际组织在彼此关系中的行为的一套规则和原则。

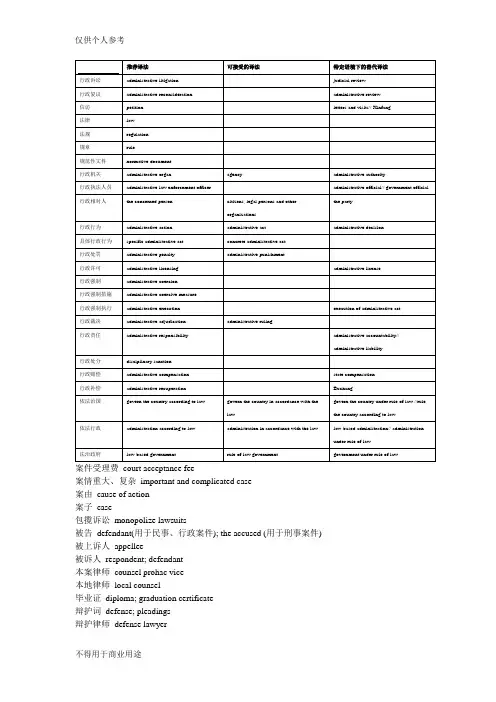

推荐译法可接受的译法特定语境下的替代译法行政诉讼administrative litigation judicial review行政复议administrative reconsideration administrative review信访petition letters and visits// Xinfang法律law法规regulation规章rule规范性文件normative document行政机关administrative organ agency administrative authority行政执法人员administrative law enforcement officer administrative official// government official 行政相对人the concerned person citizens, legal persons and otherorganizationsthe party行政行为administrative action administrative act administrative decision具体行政行为specific administrative act concrete administrative act行政处罚administrative penalty administrative punishment行政许可administrative licensing administrative license行政强制administrative coercion行政强制措施administrative coercive measure行政强制执行administrative execution execution of administrative act行政裁决administrative adjudication administrative ruling行政责任administrative responsibility administrative accountability//administrative liability行政处分disciplinary sanction行政赔偿administrative compensation state compensation行政补偿administrative recuperation Buchang依法治国govern the country according to law govern the country in accordance with thelaw govern the country under rule of law //rule the country according to law依法行政administration according to law administration in accordance with the law law-based administration// administrationunder rule of law法治政府law-based government rule of law government government under rule of law案件受理费court acceptance fee案情重大、复杂important and complicated case案由cause of action案子case包揽诉讼monopolize lawsuits被告defendant(用于民事、行政案件); the accused (用于刑事案件)被上诉人appellee被诉人respondent; defendant本案律师counsel prohac vice本地律师local counsel毕业证diploma; graduation certificate辩护词defense; pleadings辩护律师defense lawyer辩护要点point of defense辩护意见submission财产租赁property tenancy裁定书order; ruling; determination(指终审裁定)裁决书award(用于仲裁)裁决书verdict(用于陪审团)采信的证据admitted evidence; established evidence草拟股权转让协议drafting agreement of assignment of equity interests查阅法条source legal provisions产权转让conveyancing出差go on errand; go on a business trip出国深造further study abroad出具律师意见书providing legal opinion出示的证据exhibit出庭appear in court传票summons; subpoena答辩状answer; reply代理词representation代理房地产买卖与转让agency for sale and transfer of real estate代理公证、商标、专利、版权、房地产、工商登记agency for notarization, trademark, patent, copyright, and registration of real estate and incorporations代理仲裁agency for arbitration代写文书drafting of legal instruments待决案件pending case当事人陈述statement of the parties第三人third party吊销执业证revocation of lawyer license调查笔录investigative record调查取证investigation and gathering for evidence调解mediation调解书mediation二审案件case of trial of second instance发送电子邮件send e-mail法律顾问legal consultants法律意见书legal opinions法律援助legal aid法律咨询legal counseling法庭division; tribunal法学博士学位LL.D (Doctor of Laws)法学会law society法学课程legal courses法学硕士学位LL.M (Master of Laws)法学系faculty of law; department of law法学学士学位LL.B (Bachelor of Laws)J.D ( juris doctor缩写,美国法学学士)法学院law school法院公告court announcement反诉状counterclaim房地产律师real estate lawyer; real property lawyer非合伙律师associate lawyer非诉讼业务non-litigation practice高级合伙人senior partner高级律师senior lawyer各类协议和合同agreements and contracts公安局Public Security Bureau公司上市company listing公诉案件public-prosecuting case公证书notarial certificate国办律师事务所state-run law office国际贸易international trade国际诉讼international litigation国内诉讼domestic litigation合伙律师partner lawyer合伙制律师事务所law office in partner-ship; cooperating law ofice 合同审查、草拟、修改contract review, drafting and revision会见当事人interview a client会见犯罪嫌疑人interview a criminal suspect兼职律师part-time lawyer监狱prison; jail鉴定结论expert conclusion缴纳会费membership dues举证责任burden of proof; onus probandi决定书decision勘验笔录record of request看守所detention house抗诉书protest控告人accuser; complainant跨国诉讼transnational litigation劳动争议labor disputes劳动争议仲裁委员会arbitration committee for labor disputes劳改场reform-through-labor farm; prison farm利害关系人interested party; party in interest律管处处长director of lawyer control department律师lawyer attorney; attorney at law律师惩戒lawyer discipline律师法Lawyer Law律师费lawyer fee律师函lawyer’s letter律师见证lawyer attestation/authentication律师见证书lawyer certification/authentication/witness律师卷宗lawyer’s docile; file律师刊物lawyer’s journal律师联系电话contact phone number of a lawyer律师事务所law office; law firm律师收费billing by lawyer律师网站lawyer website律师协会National Bar (Lawyer) Association律师协会会员member of Lawyer Association律师协会秘书长secretary general of Bar (Lawyer) Association 律师协会章程Articles of Lawyer Assocition律师业务室lawyer’s office律师执业证lawyer license律师助理assistant lawyer律师资格考试bar exam; lawyer qualification exam律师资格证lawyer qualification certificate民事案件civil case民事调解civil mediation民事诉讼civil litigation派出所local police station; police substation判决judgement(用于民事、行政案件);determination(用于终审);sentence(用于刑事案);verdict(由陪审团作出)旁证circumstantial evidence企业章程articles of association; articles of incorporation; bylaw 企业重组corporate restructure起诉状information; indictment取消律师资格disbar全国律师代表大会National Lawyer Congress缺席宣判pronounce judgement or determination by default人民法院People’s Court人民检察院People’s Procuratorate认定事实determine facts上诉案件case of trial of second instance; appellate case上诉人appellant上诉状petition for appeal涉外律师lawyers specially handling foreign-related matters申请复议administrative reconsideration petition申请加入律师协会application for admission to Law Association 申请人petitioner; claimant申诉案件appeal case申诉人(仲裁)claimant; plaintiff申诉书appeal for revision, petition for revision实习律师apprentice lawyer; lawyer in probation period实习律师证certificate of apprentice lawyer视听证据audio-visual reference material适用法律apply law to facts受害人victim书证documentary evidence司法部Ministry of Justice司法建议书judicial advise司法局Judicial Bureau司法局副局长deputy director of Judicial Bureau司法局局长director of Judicial Bureau司法统一考试uniform judicial exam送达service of process诉讼litigation; action; lawsuit诉讼当事人litigation party; litigious party诉讼业务litigation practice诉状complaint; bill of complaint; statement of claim推销法律服务promote/market legal service外国律师事务所foreign law office委托代理合同authorized representation contract委托代理人agent ad litem; entrusted agent委托授权书power of attorney物证material evidence嫌疑人criminal suspect项目融资project financing项目谈判project negotiating刑事案件criminal case刑事诉讼criminal litigation行政诉讼administrative litigation休庭adjourn the court; recess宣判pronounce judgement; determination宣誓书affidavit业务进修attendance in advanced studies一审案件case of trial of first instance与国外律师事务所交流communicate with foreign law firms 原告plaintiff证券律师securities lawyer证人证言testimony of witness; affidavit执行笔录execution record执业登记registration for practice执业范围scope of practice; sphere of practice; practice area 执业申请practice application执业证年检annual inspection of lawyer license仲裁arbitration仲裁案件arbitration case仲裁机构arbitration agency专门律师specialized lawyer专职律师professional lawyer; full-time lawyer撰写法律文章write legal thesis资信调查credit standing investigation自诉案件private prosecuting case二、诉讼法律案件case案件发回remand/rimit a case (to a low court)案件名称title of a case案卷材料materials in the case案情陈述书statement of case案外人person other than involved in the case案值total value involved in the case败诉方losing party办案人员personnel handling a case保全措施申请书application for protective measures报案report a case (to security authorities)被告defendant; the accused被告人最后陈述final statement of the accused被告向原告第二次答辩rejoinder被害人victim被害人的诉讼代理人vict im’s agent ad litem被上诉人respondent; the appellee被申请人respondent被申请执行人party against whom execution is filed被执行人person subject to enforcement本诉principal action必要共同诉讼人party in necessary co-litigation变通管辖jurisdiction by accord辩护defense辩护律师defense attorney/lawyer辩护人defender辩护证据exculpatory evidence; defense evidence辩论阶段stage of court debate驳回反诉dismiss a counterclaim; reject a counterclaim驳回请求deny/dismiss a motion驳回上诉、维持原判reject/dismiss the appeal and sustain the original judgement/ruling 驳回诉讼dismiss an action/suit驳回通知书notice of dismissal驳回自诉dismiss/reject a private prosecution驳回自诉裁定书ruling of dismissing private-prosecuting case补充答辩supplementary answer补充判决supplementary judgement补充侦查supplementary investigation不公开审理trial in camera不立案决定书written decision of no case-filing不批准逮捕决定书written decision of disapproving an arrest不起诉nol pros不予受理起诉通知书notice of dismissal of accusation by the court财产保全申请书application for attachment; application for property preservation裁定order; determination (指最终裁定)裁定管辖jurisdiction by order裁定书order; ruling裁决书award采信的证据admitted evidence查封seal up撤回上诉withdraw appeal撤诉withdraw a lawsuit撤销立案revoke a case placed on file撤销原判,发回重审rescind the original judgement and remand the case ro the original court for retrial出示的证据exhibit除权判决invalidating judgement (for negotiable instruments)传唤summon; call传闻证据hearsay答辩answer; reply答辩陈述书statement of defence答辩状answer; reply大法官associate justices; justice大检察官deputy chief procurator代理控告agency for accusation代理申诉agency for appeal代理审判员acting judge代为申请取保候审agency for application of the bail pending trial with restricted liberty of moving弹劾式诉讼accusatory procedure当事人陈述statement of the parties当庭宣判pronouncement of judgement or sentence in court地区管辖territorial jurisdiction地区检察分院inter-mediate People’s Procuratorate第三人third party调查笔录record of investigation定期宣判pronouncement of judgement or sentence later on a fixed date定罪证据incriminating evidence; inculpatory evidence冻结freeze督促程序procedure of supervision and urge独任庭sole-judge bench独任仲裁员sole arbitrator对妨碍民事诉讼的强制措施compulsory measures against impairment of civil action对席判决judgement inter parties二审trial of second instance二审案件case of trial of second insurance罚款impose a fine法定证据statutory legal evidence法定证据制度system of legal evidence法官judges法警bailiff; court police法律文书legal instruments/papers法律援助legal aid法律咨询legal consulting法庭辩论court debate法庭调查court investigation法庭审理笔录court record法庭审理方式mode of court trial法庭庭长chief judge of a tribunal法院court法院公告court announcement反诉counterclaim反诉答辩状answer with counterclaim反诉状counterclaim犯罪嫌疑人criminal suspect附带民事诉讼案件a collateral civil action附带民事诉讼被告defendant of collateral civil action复查reexamination; recheck复验reinspect高级法官senior judge高级检察官senior procurator高级人民法院Higher People’s Court告诉案件case of complaint告诉才处理的案件case accepted at complaint告诉申诉庭complaint and petition division工读学校work-study school for delinquent children公安部Ministry of Public Security公安分局public security sub-bureau公安厅public security bureau at the levels of provinces, autonomous regions and cities under direct jurisdiction of central government公开审理trial in public公开审判制度open trial system公示催告程序procedure of public summons for exhortation公诉案件public-prosecuting case公诉词statement of public prosecution公证机关public notary office共同管辖concurrent jurisdiction管辖jurisdiction国际司法协助international judicial assistance海事法院maritime court合议庭collegial panel合议庭评议笔录record of deliberating by the collegiate bench和解composition; compromise核对诉讼当事人身份check identity of litigious parties恢复执行resumption of execution回避withdrawal混合式诉讼mixed action基层人民法院basic People’s Court羁押期限term in custody级别管辖subject matter jurisdiction of courts at different levels监视居住living at home under surveillance监狱prison检察官procurator检察权prosecutorial power检察委员会procuratorial/prosecutorial committee检察院procuratorate检察院派出机构outpost tribunal of procuratorate简易程序summary procedure鉴定结论expert conclusion经济审判庭economic tribunal径行判决direct adjudication without sessions; judgement without notice 纠问式诉讼inquisitional proceedings拘传summon by force; summon by warrant拘留所detention house举报information/report of an offence举证责任burden of proof; onus probandi决定书decision军事法院military procuratorate开庭审理open a court session开庭通知notice of court session勘验笔录record of inquest看守所detention house可执行财产executable property控告式诉讼accusatory proceedings控诉证据incriminating evidence控诉职能accusation function扣押distrain on; attachment扣押物distress/distraint宽限期period of grace劳动争议仲裁申请书petition for labor dispute arbitration劳改场reform-through-labor farm劳教所reeducation-through-labor office类推判决的核准程序procedure for examination and approval of analogical sentence累积证据cumulative evidence立案报告place a case on file立案管辖functional jurisdiction立案决定书written decision of case-filing立案侦查report of placing a case on file利害关系人interested party临时裁决书interim award律师见证书lawyer’s written attestation; lawyer’s written authentication律师事务所law office; law firm律师提前介入prior intervention by lawyer免于刑事处分exemption from criminal penalty民事案件civil case民事审判庭civil tribunal民事诉讼civil action民事诉讼法Civil Procedural Law扭送seize and deliver a suspect to the police派出法庭detached tribunal派出所police station判决judgement; determination判决书judgement; determination; verdict (指陪审团作出的)旁证circumstantial evidence陪审员juror批准逮捕approval of arrest破案clear up a criminal case; solve a criminal case破产bankruptcy; insolvency普通程序general/ordinary procedure普通管辖general jurisdiction企业法人破产还债程序procedure of bankruptcy and liquidation of a business corporation起诉filing of a lawsuit起诉sue; litigate; prosecute; institution of proceedings起诉状indictment; information区县检察院grassroots People’s Procuratorate取保候审the bail pending trial with restricted liberty of moving缺席判决default judgement人民调解委员会People’s Mediation Committee认定财产无主案件cases concerning determination of property as qwnerless认定公民无民事行为能力、限制民事行为能力案件cases concerning determination of a citizen as incompetent or with limited disposing capacity上诉appeal上诉人appellant上诉状petition for appeal少管所juvenile prison社会治安综合治理comprehensive treatment of social security涉外案件cases involving foreign interests涉外民事诉讼foreign civil proceedings涉外刑事诉讼foreign criminal proceedings申请人applicant; petitioner申请书petition; application for arbitration申请执行人execution applicant申诉人宣誓书claimant’s affidavit of authenticity申诉书appeal for revision; petition for revision神示证据制度system of divinity evidence神示制度ordeal system审查案件case review审查并决定逮捕examine and decide arrest审查起诉阶段stage of review and prosecution审理通知书notice of hearing审判长presiding judge审判长宣布开庭presiding judge announce court in session审判管辖adjudgement/trial jurisdiction审判监督程序procedure for trial supervision审判委员会judicial committee审判员judge审问式诉讼inquisitional proceedings生效判决裁定legally effective judgement/order胜诉方winning party省市自治区检察院higher People’s Procuratorate失踪和死亡宣告declaration of disappearance and death实(质)体证据substantial evidence实物证据tangible evidence实在证据real evidence示意证据demonstrative evidence视听证据audio-visual evidence收容所collecting post; safe retreat首席大法官chief justice首席检察官chief procurator受害人的近亲属victim’s immediate family受理acceptance受理刑事案件审批表registration form of acceptance of criminal case 受送达人the addressee书记员court clerk书记员宣读法庭纪律court clerk reads court rules书证documentary evidence司法部Ministry of Justice司法机关judicial organizatons司法警察judicial police司法局judicial bureau司法厅judicial bureau at the levels of provinces, autonomous regions, and cities under direct jurisdiction of central government司法协助judicial assistance死缓的复核judicial review of death sentence with a retrieve死刑复核程序procedure for judicial review of death sentence死刑复核权competence for judicial review of death sentence送达service of process送达传票service of summons/subpoena送达诉状service of bill of complaint搜查search诉sue; suit; action; lawsuit诉前财产保全property attachment prior to lawsuit诉讼litigation; lawsuit; sue; action诉讼保全attachment诉讼参加人litigious participants诉讼代理人agent ad litem诉状complaint; bill of complaint; state of claim特别程序special procedures提起公诉institute a public prosecution铁路法院railway court铁路检察院railroad transport procuratorate庭审程序procedure of court trial通缉wanted for arrest投案appearance退回补充侦查return of a case for supplementary investigation委托辩护entrusted defense未成年人法庭juvenile court无行政职务的法官associate judge无正当理由拒不到庭refuse to appear in court without due cause无罪判决acquittal, finding of “ not guilty ”物证material evidence先予执行申请书application for advanced execution先予执行advanced execution刑事案件criminal case刑事拘留criminal detention刑事强制拘留criminal coercive/compulsory measures刑事审判庭criminal tribunal刑事诉讼criminal proceedings刑事诉讼法Criminal Procedural Law刑事自诉状self-incriminating criminal complaint行政案件administrative case行政审判庭administrative tribunal行政诉讼administrative proceedings行政诉讼法Administrative Procedural Law宣告失踪、宣告死亡案件cases concerning the declaration of disappearance and death 宣判笔录record of rendition of judgement选民资格案件cases concerning qualifications of voters询问证人inquire/question a witness训诫reprimand讯问笔录record of interrogation询问犯罪嫌疑人interrogate criminal suspect言词证据verbal evidence要求传唤证人申请书application for subpoena一裁终局arbitration award shall be final and binding一审trial of first instance一审案件case of trial of first instance应诉通知书notice of respondence to action有罪判决sentence; finding of “guilty”予审preliminary examinantion; pretrial原告plaintiff院长court president阅卷笔录record of file review (by lawyers)再审案件case of retrial再审申请书petition for retrial责令具结悔过order to sign a statement of repentance债权人会议creditors’ meeting侦查阶段investigation stage侦查终结conclusion of investigation征询原、被告最后意见consulting final opinion of the plaintiff and defendant证据evidence证据保全preserve evidence证据保全申请书application for evidence preservation证人证言testimony of witness; affidavit支付令payment order/warrant知识产权庭intellectual property tribunal执行程序procedure execution执行逮捕execution of arrest执行和解conciliation of execution执行回转recovery of execution执行庭executive tribunal执行异议objection to execution执行员executor执行中止discontinuance of execution执行终结conclusion of execution指定辩护appointed defense指定仲裁员声明statement of appointing arbitrator中级人民法院intermediate People’s Court中途退庭retreat during court session without permission仲裁arbitration仲裁被诉人respondent; defendant仲裁裁决award仲裁申请书arbitration仲裁申诉人claimant; plaintiff仲裁庭arbitration tribunal仲裁委员会arbitration committee仲裁协议arbitration agreement; clauses of arbitration仲裁员arbitrator主诉检察官principal procurator助理检察官assistant procurator助理审判员assistant judge专门法院special court专门管辖specific jurisdiction专属管辖exclusive jurisdiction追究刑事责任investigate for criminal responsibility自首confession to justice自诉案件private-prosecuting case自行辩护self-defense自由心证制度doctrine of discretional evaluation of evidence 自侦案件self-investigating case最高人民法院the Supreme People’s Court最高人民检察院the Supreme Peop le’s Procuratorate最后裁决书final award三、民事法律法律渊源source of law制定法statute判例法case law; precedent普通法common law特别法special law固有法native law; indigenous law继受法adopted law实体法substantial law程序法procedural law原则法fundamental law例外法exception law司法解释judicial interpretation习惯法customary law公序良俗public order and moral自然法natural law罗马法Roman Law私法private law公法public law市民法jus civile万民法jus gentium民法法系civil law system英美法系system of Anglo-American law大陆法系civil law system普通法common law大陆法continental law罗马法系Roman law system英吉利法English law衡平法equity; law of equity日尔曼法Germantic law教会法ecclesiastical law寺院法canon law伊斯兰法Islamic law民法法律规范norm of civil law授权规范authorization norm禁止规范forbidding norm义务性规范obligatory norm命令性规范commanding norm民法基本原则fundamental principles of civil law 平等原则principle of equality自愿原则principle of free will公平原则principle of justice等价有偿原则principle of equal value exchange 诚实信用原则principle of good faith行为act作为act不作为omission合法行为lawful act违法行为unlawful act民事权利权利能力civil right绝对权absolute right相对权relative right优先权right of priority先买权preemption原权antecedent right救济权right of relief支配权right of dominion请求权right of claim物上请求权right of claim for real thing形成权right of formation撤销权right of claiming cancellation否认权right of claiming cancellation解除权right of renouncement代位权subrogated right选择权right of choice承认权right of admission终止权right of termination抗辩权right of defense一时性抗辩权momentary right of defense永久性抗辩权permanent counter-argument right不安抗辩权unstable counter-argument right同时履行抗辩权defense right of simultaneous performance 既得权tested right期待权expectant right专属权exclusive right非专属权non-exclusive right人身权利personal right人权human right人格权right of personality生命健康权right of life and health姓名权right of name名称权right of name肖像权right of portraiture自由权right of freedom名誉权right reputation隐私权right of privacy私生活秘密权right of privacy贞操权virginity right身份权right of status亲权parental power; parental right亲属权right of relative探视权visitation right配偶权right of spouse荣誉权right of honor权利的保护protection of right公力救济public protection私力救济self-protection权利本位standard of right社会本位standard of society无责任行为irresponsible right正当防卫justifiable right; ligitimate defence防卫行为act of defence自为行为self-conducting act紧急避险act of rescue; necessity自助行为act of self-help不可抗力force majeure意外事件accident行为能力capacity for act意思能力capacity of will民事行为civil act意思表示declaration of intention意思表示一致meeting of minds; consensus完全行为能力perfect capacity for act限制行为能力restrictive capacity for act准禁治产人quasi-interdicted person保佐protection自治产人minor who is capable of administering his own capacity 无行为能力incapacity for act禁治产人interdicted person自然人natural person公民citizen住所domicile居所residence经常居住地frequently dwelling place户籍census register监护guardianship个体工商户individual business农村承包经营户leaseholding rural household合伙partnership合伙人partner合伙协议partnership agreement合伙财产property of partnership合伙债务debt of partnership入伙join partnership退伙withdrawal from partnership合伙企业partnership business establishment个人合伙partnership法人合伙partnership of legal person特别合伙special partnership普通合伙general partnership有限合伙limited partnership民事合伙civil partnership隐名合伙sleeping partnership; dormant partnership私营企业private enterprise; proprietorship法人legal person企业法人legal body of enterprise企业集团group of enterprise关联企业affiliate enterprise个人独资企业individual business establishment国有独资企业solely state-owned enterprise中外合资企业Sino-foreign joint venture enterprise中外合作企业Sino-foreign contractual enterprise社团法人legal body of mass organization财团法人legal body of financial group联营joint venture法人型联营association of legal persons合伙型联营coordinated management in partnership协作型联营cooperation-type coordinated management合作社cooperative民事法律行为civil legal act单方民事法律行为unilateral civil legal act双方民事法律行为bilateral civil legal act多方民事法律行为joint act civil legal act有偿民事法律行为civil legal act with consideration无偿民事法律行为civil legal act without consideration; civil legal act without award 实践性民事法律行为practical civil legal act诺成性民事法律行为consental civil legal act要式民事法律行为formal civil legal act不要式民事法律行为informal civil legal act要因民事法律行为causative civil legal act不要因民事法律行为noncausative civil legal act主民事法律行为principal civil legal act从民事法律行为accessory civil legal act附条件民事法律行为conditional civil legal act附期限民事法律行为civil legal act with term生前民事法律行为civil legal act before death死后民事法律行为civil legal act after death准民事法律行为quasi-civil legal act无效行为ineffective act可撤销民事行为revocable civil act违法行为illegal act; unlawful act侵权行为tort欺诈fraud胁迫duress乘人之危taking advantage of others’ precarious position以合法形式掩盖非法目的legal form concealing illegal intention恶意串通malicious collaboration重大误解gross misunderstanding显失公平obvious unjust误传misrepresentation代理agency本人principal被代理人principal受托人trustee代理人agent本代理人original agent法定代理人statutory agent; legal agent委托代理人agent by mandate指定代理人designated agent复代理人subagent再代理人subagent转代理人subagent代理权right of agency授权行为act of authorization授权委托书power of attorney代理行为act of agency委托代理agency by mandate本代理original agency复代理subagency次代理subagency有权代理authorized agency表见代理agency by estoppel; apparent agency律师代理agency by lawyer普通代理general agency全权代理general agency全权代理委托书general power of attorney共同代理joint agency独家代理sole agency居间brokerage居间人broker行纪commission; broker house信托trust时效time limit; prescription; limitation时效中止suspension of prescription/limitation时效中断interruption of limitation/prescription时效延长extension of limitation取得时效acquisitive prescription时效终止lapse of time; termination of prescription 期日date期间term涉外民事关系civil relations with foreign elements 冲突规范rule of conflict准据法applicable law; governing law反致renvoi; remission转致transmission识别identification公共秩序保留reserve of public order法律规避evasion of law国籍nationality国有化nationalization法律责任legal liability民事责任civil liability/responsibility行政责任administrative liability/responsibility刑事责任criminal liability/responsibility违约责任liability of breach of contract; responsibility of default 有限责任limited liability无限责任unlimited liability按份责任shared/several liability连带责任joint and several liability过失责任liability for negligence; negligent liability过错责任fault liability; liability for fault单独过错sole fault共同过错joint fault混合过错mixed fault被害人过错victim’s fault第三人过错third party’s fault推定过错presumptive fault恶意bad faith; malice故意deliberate intention; intention; willfulness过失negligence重大过失gross negligence疏忽大意的过失careless and inadvertent negligence过于自信的过失negligence with undue assumption损害事实facts of damage有形损失tangible damage/loss无形损失intangible damage/loss财产损失property damage/loss人身损失personal damage/loss精神损失spiritual damage/loss民事责任承担方式methods of bearing civil liability停止侵害cease the infringing act排除妨碍exclusion of hindrance; removal of obstacle消除危险elimination of danger返还财产restitution of property恢复原状restitution; restitution of original state赔偿损失compensate for a loss; indemnify for a loss支付违约金payment of liquidated damage消除影响eliminate ill effects恢复名誉rehabilitate one’s reputation赔礼道歉extend a formal apology物权jus ad rem; right in rem; real right物权制度real right system; right in rem system一物一权原则the principal of One thing, One Right物权法定主义principal of legality of right in rem物权公示原则principal of public summons of right in rem 物权法jus rerem物property生产资料raw material for production生活资料means of livelihood; means of subsistence流通物res in commercium; a thing in commerce限制流通物limited merchantable thing禁止流通物res extra commercium; a thing out of commerce 资产asset固定资产fixed asset流动资产current asset; floating asset动产movables; chattel不动产immovable; real estate特定物res certae; a certain thing种类物genus; indefinite thing可分物res divisibiles; divisible things不可分物res indivisibiles; indivisible things主物res capitalis; a principal thing从物res accessoria; an accessory thing原物original thing孳息fruits天然孳息natural fruits法定孳息legal fruits无主物bona vacatia; vacant goods; ownerless goods遗失物lost property漂流物drifting object埋藏物fortuna; hidden property货币currency证券securities债券bond物权分类classification of right in rem/real right自物权jus in re propria; right of full ownership所有权dominium; ownership; title所有权凭证document of title; title of ownership占有权dominium utile; equitable ownership使用权right of use; right to use of收益权right to earnings; right to yields处分权right of disposing; jus dispodendi善意占有possession in good faith。

附录一(外文原文)BOOK II mean to inquire if, in the civil order, there can be any sure and legitimate rule of administration, men being taken as they are and laws as they might be. In this inquiry I shall end always to unite what right sanctions with what is prescribed by interest, in order that justice and utility may in no case be divided.I enter upon my task without proving the importance of the subject. I shall be asked if I am a prince or a legislator, to write on politics. I answer that I am neither, and that is why I do so. If I were a prince or a legislator, I should not waste time in saying what wants doing; I should do it, or hold my peace.As I was born a citizen of a free State, and a member of the Sovereign, I feel that, however feeble the influence my voice can have on public affairs, the right of voting on them makes it my duty to study them: and I am happy, when I reflect upon governments, to find my inquiries always furnish me with new reasons for loving that of my own country.1. SUBJECT OF THE FIRST BOOKMan is born free; and everywhere he is in chains. One thinks himself the master of others, and still remains a greater slave than they. How did this change come about? I do not know. What can make it legitimate? That question I think I can answer.If I took into account only force, and the effects derived from it, I should say: "As long as a people is compelled to obey, and obeys, it does well; as soon as it can shake off theyoke, and shakes it off, it does still better; for, regaining its liberty by the same right as took it away, either it is justified in resuming it, or there was no justification for those who took it away." But the social order is a sacred right which is the basis of all other rights. Nevertheless, this right does not come from nature, and must therefore be founded on conventions. Before coming to that, I have to prove what I have just asserted.2. THE FIRST SOCIETIESThe most ancient of all societies, and the only one that is natural, is the family: and even so the children remain attached to the father only so long as they need him for their preservation. As soon as this need ceases, the natural bond is dissolved. The children, released from the obedience they owed to the father, and the father, released from the care he owed his children, return equally to independence. If they remain united, they continue so no longer naturally, but voluntarily; and the family itself is then maintained only by convention.This common liberty results from the nature of man. His first law is to provide for his own preservation, his first cares are those which he owes to himself; and, as soon as he reaches years of discretion, he is the sole judge of the proper means of preserving himself, and consequently becomes his own master.The family then may be called the first model of political societies: the ruler corresponds to the father, and the people to the children; and all, being born free and equal, alienate their liberty only for their own advantage. The whole difference is that,in the family, the love of the father for his children repays him for the care he takes of them, while, in the State, the pleasure of commanding takes the place of the love which the chief cannot have for the peoples under him.Grotius denies that all human power is established in favour of the governed, and quotes slavery as an example. His usual method of reasoning is constantly to establish right by fact. It would be possible to employ a more logical method, but none could be more favourable to tyrants.It is then, according to Grotius, doubtful whether the human race belongs to a hundred men, or that hundred men to the human race: and, throughout his book, he seems to incline to the former alternative, which is also the view of Hobbes. On this showing, the human species is divided into so many herds of cattle, each with its ruler, who keeps guard over them for the purpose of devouring them.As a shepherd is of a nature superior to that of his flock, the shepherds of men, i.e., their rulers, are of a nature superior to that of the peoples under them. Thus, Philo tells us, the Emperor Caligula reasoned, concluding equally well either that kings were gods, or that men were beasts.The reasoning of Caligula agrees with that of Hobbes and Grotius. Aristotle, before any of them, had said that men are by no means equal naturally, but that some are born for slavery, and others for dominion.Aristotle was right; but he took the effect for the cause. Nothing can be more certain than that every man born in slavery is born for slavery. Slaves lose everything in theirchains, even the desire of escaping from them: they love their servitude, as the comrades of Ulysses loved their brutish condition. If then there are slaves by nature, it is because there have been slaves against nature. Force made the first slaves, and their cowardice perpetuated the condition.I have said nothing of King Adam, or Emperor Noah, father of the three great monarchs who shared out the universe, like the children of Saturn, whom some scholars have recognised in them. I trust to getting due thanks for my moderation; for, being a direct descendant of one of these princes, perhaps of the eldest branch, how do I know that a verification of titles might not leave me the legitimate king of the human race? In any case, there can be no doubt that Adam was sovereign of the world, as Robinson Crusoe was of his island, as long as he was its only inhabitant; and this empire had the advantage that the monarch, safe on his throne, had no rebellions, wars, or conspirators to fear.3. THE RIGHT OF THE STRONGESTThe strongest is never strong enough to be always the master, unless he transforms strength into right, and obedience into duty. Hence the right of the strongest, which, though to all seeming meant ironically, is really laid down as a fundamental principle. But are we never to have an explanation of this phrase? Force is a physical power, and I fail to see what moral effect it can have. To yield to force is an act of necessity, not of will -- at the most, an act of prudence. In what sense can it be a duty?Suppose for a moment that this so-called "right" exists. I maintain that the sole result isa mass of inexplicable nonsense. For, if force creates right, the effect changes with the cause: every force that is greater than the first succeeds to its right. As soon as it is possible to disobey with impunity, disobedience is legitimate; and, the strongest being always in the right, the only thing that matters is to act so as to become the strongest. But what kind of right is that which perishes when force fails? If we must obey perforce, there is no need to obey because we ought; and if we are not forced to obey, we are under no obligation to do so. Clearly, the word "right" adds nothing to force: in this connection, it means absolutely nothing.Obey the powers that be. If this means yield to force, it is a good precept, but superfluous: I can answer for its never being violated. All power comes from God, I admit; but so does all sickness: does that mean that we are forbidden to call in the doctor? A brigand surprises me at the edge of a wood: must I not merely surrender my purse on compulsion; but, even if I could withhold it, am I in conscience bound to give it up? For certainly the pistol he holds is also a power.Let us then admit that force does not create right, and that we are obliged to obey only legitimate powers. In that case, my original question recurs.4. SLA VERYSince no man has a natural authority over his fellow, and force creates no right, we must conclude that conventions form the basis of all legitimate authority among men. If an individual, says Grotius, can alienate his liberty and make himself the slave of a master, why could not a whole people do the same and make itself subject to a king?There are in this passage plenty of ambiguous words which would need explaining; but let us confine ourselves to the word alienate. To alienate is to give or to sell. Now, a man who becomes the slave of another does not give himself; he sells himself, at the least for his subsistence: but for what does a people sell itself? A king is so far from furnishing his subjects with their subsistence that he gets his own only from them; and, according to Rabelais, kings do not live on nothing. Do subjects then give their persons on condition that the king takes their goods also? I fail to see what they have left to preserve.It will be said that the despot assures his subjects civil tranquillity.Granted; but what do they gain, if the wars his ambition brings down upon them, his insatiable avidity, and the vexations conduct of his ministers press harder on them than their own dissensions would have done? What do they gain, if the very tranquillity they enjoy is one of their miseries? Tranquillity is found also in dungeons; but is that enough to make them desirable places to live in? The Greeks imprisoned in the cave of the Cyclops lived there very tranquilly, while they were awaiting their turn to be devoured.To say that a man gives himself gratuitously, is to say what is absurd and inconceivable; such an act is null and illegitimate, from the mere fact that he who does it is out of his mind. To say the same of a whole people is to suppose a people of madmen; and madness creates no right.Even if each man could alienate himself, he could not alienate his children: they are born men and free; their liberty belongs to them, and no one but they has the right todispose of it. Before they come to years of discretion, the father can, in their name, lay down conditions for their preservation and well-being, but he cannot give them irrevocably and without conditions: such a gift is contrary to the ends of nature, and exceeds the rights of paternity. It would therefore be necessary, in order to legitimise an arbitrary government, that in every generation the people should be in a position to accept or reject it; but, were this so, the government would be no longer arbitrary.To renounce liberty is to renounce being a man, to surrender the rights of humanity and even its duties. For him who renounces everything no indemnity is possible. Such a renunciation is incompatible with man's nature; to remove all liberty from his will is to remove all morality from his acts. Finally, it is an empty and contradictory convention that sets up, on the one side, absolute authority, and, on the other, unlimited obedience. Is it not clear that we can be under no obligation to a person from whom we have the right to exact everything? Does not this condition alone, in the absence of equivalence or exchange, in itself involve the nullity of the act? For what right can my slave have against me, when all that he has belongs to me, and, his right being mine, this right of mine against myself is a phrase devoid of meaning?Grotius and the rest find in war another origin for the so-called right of slavery. The victor having, as they hold, the right of killing the vanquished, the latter can buy back his life at the price of his liberty; and this convention is the more legitimate because it is to the advantage of both parties.But it is clear that this supposed right to kill the conquered is by no means deduciblefrom the state of war. Men, from the mere fact that, while they are living in their primitive independence, they have no mutual relations stable enough to constitute either the state of peace or the state of war, cannot be naturally enemies. War is constituted by a relation between things, and not between persons; and, as the state of war cannot arise out of simple personal relations, but only out of real relations, private war, or war of man with man, can exist neither in the state of nature, where there is no constant property, nor in the social state, where everything is under the authority of the laws.Individual combats, duels and encounters, are acts which cannot constitute a state; while the private wars, authorised by the Establishments of Louis IX, King of France, and suspended by the Peace of God, are abuses of feudalism, in itself an absurd system if ever there was one, and contrary to the principles of natural right and to all good polity.War then is a relation, not between man and man, but between State and State, and individuals are enemies only accidentally, not as men, nor even as citizens, but as soldiers; not as members of their country, but as its defenders. Finally, each State can have for enemies only other States, and not men; for between things disparate in nature there can be no real relation.Furthermore, this principle is in conformity with the established rules of all times and the constant practice of all civilised peoples. Declarations of war are intimations less to powers than to their subjects. The foreigner, whether king, individual, or people, whorobs, kills or detains the subjects, without declaring war on the prince, is not an enemy, but a brigand. Even in real war, a just prince, while laying hands, in the enemy's country, on all that belongs to the public, respects the lives and goods of individuals: he respects rights on which his own are founded. The object of the war being the destruction of the hostile State, the other side has a right to kill its defenders, while they are bearing arms; but as soon as they lay them down and surrender, they cease to be enemies or instruments of the enemy, and become once more merely men, whose life no one has any right to take. Sometimes it is possible to kill the State without killing a single one of its members; and war gives no right which is not necessary to the gaining of its object. These principles are not those of Grotius: they are not based on the authority of poets, but derived from the nature of realityand based on reason.The right of conquest has no foundation other than the right of the strongest. If war does not give the conqueror the right to massacre the conquered peoples, the right to enslave them cannot be based upon a right which does not exist. No one has a right to kill an enemy except when he cannot make him a slave, and the right to enslave him cannot therefore be derived from the right to kill him. It is accordingly an unfair exchange to make him buy at the price of his liberty his life,over which the victor holds no right. Is it not clear that there is a vicious circle in founding the right of life and death on the right of slavery, and the right of slavery on the right of life and death?Even if we assume this terrible right to kill everybody, I maintain that a slave made in war, or a conquered people, is under no obligation to a master, except to obey him as far as he is compelled to do so. By taking an equivalent for his life, the victor has not done him a favour; instead of killing him without profit, he has killed him usefully. So far then is he from acquiring over him any authority in addition to that of force, that the state of war continues to subsist between them: their mutual relation is the effect of it, and the usage of the right of war does not imply a treaty of peace. A convention has indeed been made; but this convention, so far from destroying the state of war, presupposes its continuance.So, from whatever aspect we regard the question, the right of slavery is null and void, not only as being illegitimate, but also because it is absurd and meaningless. The words slave and right contradict each other, and are mutually exclusive. It will always be equally foolish for a man to say to a man or to a people: "I make with you a convention wholly at your expense and wholly to my advantage; I shall keep it as long as I like, and you will keep it as long as I like."5. THAT WE MUST ALWAYS GO BACK TO A FIRST CONVENTIONEven if I granted all that I have been refuting, the friends of despotism would be no better off. There will always be a great difference between subduing a multitude and ruling a society. Even if scattered individuals were successively enslaved by one man, however numerous they might be, I still see no more than a master and his slaves, and certainly not a people and its ruler; I see what may be termed an aggregation, but notan association; there is as yet neither public good nor body politic. The man in question, even if he has enslaved half the world, is still only an individual; his interest, apart from that of others, is still a purely private interest. If this same man comes to die, his empire, after him, remains scattered and without unity, as an oak falls and dissolves into a heap of ashes when the fire has consumed it.A people, says Grotius, can give itself to a king. Then, according to Grotius, a people is a people before it gives itself. The gift is itself a civil act, and implies public deliberation. It would be better, before examining the act by which a people gives itself to a king, to examine that by which it has become a people; for this act, being necessarily prior to the other, is the true foundation of society.Indeed, if there were no prior convention, where, unless the election were unanimous, would be the obligation on the minority to submit to the choice of the majority? How have a hundred men who wish for a master the right to vote on behalf of ten who do not? The law of majority voting isitself something established by convention, and presupposes unanimity, on one occasion at least.附录二(中文译文)第一卷我要探讨在社会秩序之中,从人类的实际情况与法律的可能情况着眼,能不能有某种合法的而又确切的政权规则。