超越经济学与伦理学的僵局

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:212.42 KB

- 文档页数:20

伦理与经济学在商业道德与商业伦理学中的交叉与塑造引言商业道德与商业伦理学作为商业领域的重要理论和实践,涵盖了商业活动中的伦理与价值观。

伦理学和经济学作为两个不同的学科,却在商业道德与商业伦理学的发展过程中互相交叉与塑造。

本文将探讨伦理学与经济学在商业道德与商业伦理学中的作用,并分析它们如何相互影响和塑造。

伦理学与商业道德商业道德的定义商业道德是指商业活动中的道德规范和价值观。

它包括了商业实践的正当性、诚信、公正、负责任等方面。

商业道德的发展与塑造受到伦理学的影响。

伦理学对商业道德的贡献伦理学作为一门研究道德原则和价值观的学科,为商业道德提供了理论基础。

伦理学强调人的尊严和权利,鼓励人们在商业活动中秉持道德和伦理原则。

伦理学的主要概念,如公正、诚信、负责任等,都对商业道德的发展产生了积极的影响。

伦理学在商业道德中的应用伦理学为商业道德提供了一些实践指南和决策模型。

例如,伦理学中的道德原则可以用来评估商业活动的合法性和道德性。

伦理学还研究了人们在商业决策中面临的道德困境和冲突,为商业实践提供了伦理方案和道德规范。

经济学与商业伦理学商业伦理学的定义商业伦理学是研究商业行为和组织的道德和伦理问题的学科。

它探讨了商业活动中的道德和伦理原则,以及如何在商业实践中应用这些原则。

经济学对商业伦理学的贡献经济学作为研究资源配置和经济决策的学科,对商业伦理学的发展有一定的影响。

经济学关注效率和利益最大化,但它也认识到在商业活动中需要考虑道德和伦理原则。

经济学的理论和方法可以帮助商业伦理学更好地理解商业行为和组织的道德问题。

经济学在商业伦理学中的应用经济学的分析工具可以用于商业伦理学的研究和实践。

例如,经济学可以帮助研究商业活动中的道德风险和道德规范的效果。

经济学还可以通过分析商业决策的成本和效益来评估和解决道德困境。

伦理学与经济学的交叉与塑造伦理学对经济学的交叉与塑造伦理学对经济学的发展产生了一定的交叉与塑造。

伦理学的道德原则和价值观对经济学的努力进行了约束和引导。

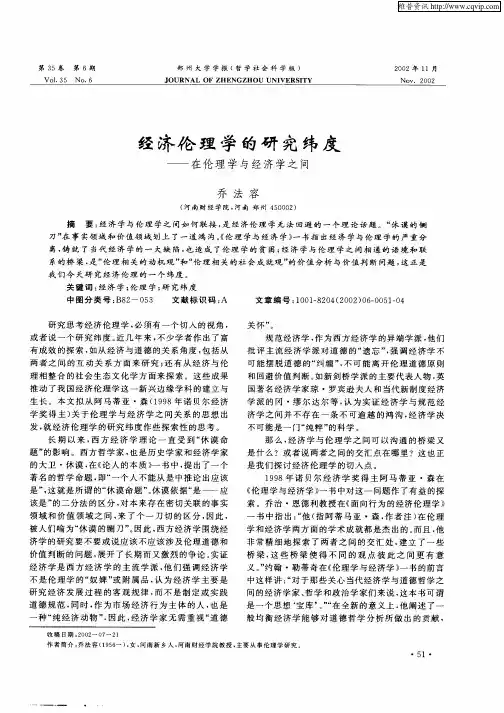

经济伦理学有关问题分析摘要:经济伦理学是以社会经济生活中的道德现象为研究对象,涵盖宏观经济制度、中观经济组织和微观经济关系中所有与道德有关的问题的一门新兴交叉学科。

任何一个国家或民族在其经济发展的背后都有一种人文力作为支撑,其核心要素是经济伦理。

认真审视和梳理经济伦理学研究中尚有争议的重大问题,对经济伦理学的研究进一步走向深入具有重要的意义。

关键词:经济伦理问题一、经济伦理学基本概念1. 经济伦理学的定义经济伦理学是以社会经济生活中的道德现象为研究对象,涵盖宏观经济制度、中观经济组织和微观经济关系中所有与道德有关的问题的一门新兴交叉学科。

经济伦理学是交叉学科、综合学科。

其学科性质,规定了对于它的研究方法的独特性,就是在经济学和伦理学之间,寻求切合点、架通由此达彼的桥梁、对于两者进行沟通、融合。

2. 经济伦理学的研究对象第一,经济学视野中的经济伦理学。

一些经济学家认为经济伦理学是研究经济运行过程中的道德价值体系,他们虽然强调道德调节在经济发展中是超越政府和市场的重要力量,但他们更多关注的似乎是经济体制、产权制度和经济规律等对伦理的影响。

第二,管理学视野中的经济伦理学。

有学者把bussiness ethics译为”管理伦理学”。

他们认为,经济伦理学是在工商管理领域内发展起来、在大学的工商管理学院或商学院开设的一门管理课程,因此,它的研究对象是经济管理活动和经济管理领域中的行为规范或制度。

目的是为了更好地进行管理。

第三,伦理学视野中的经济伦理学。

代表性的观点主要有:一,经济伦理学有广义和狭义之分。

狭义的经济伦理学即企业伦理学,而广义的经济伦理学是一门研究经济制度、经济政策、经济决策、经济行为的伦理合理性,并研究经济活动中的组织和个人的伦理规范的学科;二,经济伦理学的基本问题是经济价值与伦理价值、标准、要求的关系问题,基本任务是发现、找到伦理学与经济学两者的结合点、重叠点,由此找到解决两者冲突的基础和原则;三是经济伦理学是研究人们在社会经济活动中完善人生和协调各种利益关系的道德原则和规范的科学。

西方经济学中的经济学与伦理学的关系在西方经济学的发展过程中,经济学与伦理学一直存在着紧密的关系。

经济学作为一门研究资源配置和经济现象的学科,直接关乎人类生活的组织和运作方式。

而伦理学则探讨人类道德价值和行为准则,以指导人们应该如何在经济活动中取舍和行动。

因此,经济学与伦理学的关系既是紧密相联又相互影响的。

首先,经济活动往往涉及到利益的分配和个人行为之间的冲突。

经济学通常关注个人和团体如何在受限资源下做出最优选择,以最大化效用或利润。

然而,在追求个人经济利益的同时,是否符合道德准则也是一个需要考虑的问题。

例如,一个公司在追求利润最大化的同时,是否应该优先考虑环境保护和社会责任?这就要求经济学家应当在经济研究中关注伦理学的观点,进一步思考经济活动的道德意义,避免为了追求利益而牺牲了道德原则。

其次,经济学与伦理学的关系还体现在价值观念和社会权益的权衡上。

经济学强调资源的有效配置和社会福利的最大化,其中包含了人们的价值观念和利益追求。

然而,伦理学则主张传统的道德理念和社会公共利益。

举个例子,一个理性的经济学家可能会认为剥夺劳工权益可以提高企业的效益和利润,但从伦理学的角度看,这种做法很可能会引发道德和社会问题。

因此,伦理学需要提醒经济学家不能仅仅困于利润最大化的思维,而应考虑到人类道德和社会权益的平衡。

此外,西方经济学中的一些流派也强调经济学与伦理学的互动关系。

例如,尼古拉斯·奥斯本曾提出“公共选择理论”的概念,认为经济学与伦理学可以融合在一起,探索公共政策的形成和实施。

他的观点强调了在政府政策制定过程中应该注重道德和公平的考量,而不仅仅是经济效益。

这种观点强调了经济学与伦理学的有机结合,以实现社会福利的最大化。

总之,西方经济学中的经济学与伦理学存在着密切的关系。

经济学与伦理学不仅共同关注经济活动的道德意义,而且需要相互影响和协调,以实现人类福祉和社会进步。

经济学家和伦理学家应该在互相了解基础上共同探索经济行为的伦理维度,并在经济活动中兼顾个人利益与社会福利,以实现经济与伦理的良性互动。

经济学的伦理反思一经济学的鼻祖亚当·斯密,在他的代表作《国富论》中,提出了著名的“看不见的手”的原理。

所谓“看不见的手”就是,“每个人都在力图应用他的资本,来使其生产品能得到最大的价值。

一般地说,他并不企图增进公共福利,也不知道他所增进的公共福利为多少。

他所追求的仅仅是他个人的安乐,仅仅是他个人的利益。

在这样做时,有一只看不见的手引导他去促进一种目标,而这种目标绝不是他所追求的东西。

由于追逐他自己的利益,他经常促进了社会利益。

其效果要比他真正想促进社会利益时所得到的效果为大”。

亚当·斯密以后,“经济学者几乎用了两个世纪来证明亚当·斯密论断的核心真理”。

实证经济学是立足于这一原理,对经济运行进行“是”的研究的学问, 它依据纯粹工程学的方法,假定人都是“有理性的人”,分析和陈述实际存在的经济运行方式, 并试图对研究结论进行实证检验。

所谓“有理性的人”,就是每一个从事经济活动的人都是有理性的,他们总是企图用付出自己最小的代价来获得自己最大的利益。

当经济学者们用尽心思论断亚当·斯密的这一“看不见的手”的原理时,他们忽略了密斯在《道德情操论》中鼓励人类的同情心和自律行为,以及由此而来的美德对于社会生活的意义和价值。

密斯在他的《道德情操论》中关于人的“人道、公正、慷慨大方和热心公益”的历史道德伦理人性规定,也是社会进步与幸福的最基本要素。

这让很多密斯的追随者困惑:非“自利”而导致的,竟然是可能的美好结果(包括经济结果)?二印度学者阿玛蒂亚·森在他的《伦理学与经济学》中对这一问题进行了很好的论证。

首先,森指出,现代的经济学,有两个不寻常之处。

第一个是它所关注的人类的行为是单一的,自利的。

但是,事实上它所应该关注的是真实的人。

第二,现代经济学与伦理学的脱离与现代经济学是伦理学的一个分支而发展起来的事实之间存在着矛盾。

他认为经济学有两个不同的根源,一个是伦理学,另一个是工程学。

在经济学与伦理学之间在当今这个世界上,经济学和伦理学是两种人们普遍的关注点。

在许多情况下,经济的决策和道德问题之间存在冲突。

尽管经济学和伦理学在某些方面有着不同的关注点,他们之间还是存在着联系和相互影响的。

本文将探讨在经济学与伦理学之间的关系。

首先,经济学与伦理学的相似之处在于追求人类福利的目标。

虽然经济学可能更注重货币和资源的效率和增长,但是该学科的学者也有重视社会福利的方面。

在这方面,学者可以使用经济学的方法来帮助决策者制定合理的政策以实现更加公平和可持续的发展。

另一方面,伦理学则侧重于研究人类道德,即在不同的社会环境,什么样的行为更加合适。

这个方面同样为决策者提供了关于社会价值观和道德规范等问题的信息。

然而,仅仅注重经济效率,而忽略了道德和社会责任的方面,可能会导致严重的后果。

例如,在某些情况下,公司的经济成功可能产生负面效应,如环境破坏,人身伤害等。

经济学家的分析重点是如何在市场上获得以最小代价最高效益的产品和服务。

尽管这种分析可以在制定政策时采用,但是它不能为企业和个人提供诸如乃至于道德责任等方面的参考。

在另一方面,伦理学探讨了个人和组织之间的道德问题,基于个人行为的责任和社会价值观之间的关系,同时也注意到经济活动的社会影响。

因此,伦理学家可能对一些决策提供更广泛的洞见,以及在各种情况下遵循一定的道德准贵作为导向指南。

在某些情况下,伦理学家的意见可能反映在经济学家的决策建议上。

例如,对于环境问题的决策,经济学家从经济角度考虑,伦理学家则从道德角度考虑。

最后但并非最不重要的是,在市场或社会领域,贸易行为和道德责任之间不应该互相排斥。

道德责任需要有助于商业发展,以便在以后的时间内赢得更长远的优势。

一个公司能够积极的履行其社会责任,将为其经济增长发挥正面影响的同时,也会促进其名声,从而更好地吸引消费者和银行的支持。

总的来说,虽然在经济学和伦理学之间存在着某些冲突,但是,它们之间也存在着颇多联系和相互影响。

伦理学书目引言:伦理学作为一门独立的学科,研究人类行为的道德原则和价值观,对于我们的思考和行为具有重要的指导作用。

伦理学书目是探讨这一学科的重要参考资料,包含了众多经典著作和研究成果。

本文将围绕伦理学书目展开讨论,介绍其中一些经典和重要的著作,帮助读者深入了解伦理学的理论框架和研究领域。

一、伦理学的起源与发展1.《伦理学》(亚里士多德):这部作品被视为西方伦理学的奠基之作,系统地探讨了人类行为的道德本质和价值观。

2.《尼各马可伦理学》(亚里士多德):亚里士多德进一步发展了他的伦理学思想,探讨了幸福与道德之间的关系。

3.《伦理学原理》(约翰·斯图尔特·密尔):密尔是19世纪英国伦理学派的代表人物之一,他在这本著作中提出了以幸福为基础的行为准则。

二、伦理学的不同流派和理论1.《论伦理学》(伊曼纽尔·康德):康德是德国启蒙时代的哲学家,他的著作中提出了伦理行为应该遵循的普遍法则,强调人类的理性和自由意志。

2.《论伦理学》(约翰·罗尔斯):罗尔斯是20世纪伦理学思想的重要代表,他在这本著作中提出了正义作为伦理行为的基础原则。

3.《伦理学方法》(休·拉埃尔·斯特劳斯):斯特劳斯是当代法国伦理学家,他在这本著作中探讨了伦理学的方法论,强调了伦理学研究的科学性和客观性。

三、伦理学的应用领域和实践问题1.《伦理学与生命科学》(詹姆斯·R·卡普兰):这本书探讨了伦理学在生命科学领域的应用,涉及生命伦理学、医学伦理学等重要议题。

2.《商业伦理学》(迈克尔·J·桑德尔斯):桑德尔斯在这本著作中探讨了商业领域的道德问题,提出了商业伦理学的研究框架和原则。

3.《伦理学与环境保护》(霍尔·罗尔斯):罗尔斯是环境伦理学的重要代表人物,他在这本著作中探讨了人类与自然环境之间的道德关系和责任。

四、伦理学的批判和争议1.《超越自由:伦理学的政治经济学批判》(阿玛蒂亚·森):森是当代著名的经济学家和社会学家,他在这本著作中对西方伦理学的政治经济学基础进行了批判和反思。

在经济学与伦理学之间遨游作者:叶航来源:《浙江大学学报(人文社会科学版)》2009年第03期[摘要]我国台湾地区著名学者盛庆琜先生创立的统合效用主义理论是对古典功利主义的批评、继承和创新,这一理论与现代经济学有关“社会困境”和“社会偏好”的前沿研究相契合,也与伦理学有关“实然”和“应然”相互关系的研究相契合,是一个“统合”经济学和伦理学的跨学科研究。

特别是盛庆珠先生在统合效用主义理论中提出的“道德满足感”这一范式,可以在功利主义的基础上把经济学的最大化方法推演至人类整体行为模式,包括道德行为和利他主义的分析,从而为解决现代经济学逻辑体系的危机提供了重要的思想资源。

[关键词]功利主义;效用;统合效用主义理论我国台湾地区著名学者盛庆珠先生1991年出版了《功利主义新论:统合效用主义理论及其在公平分配上的应用》一书。

“功利主义”(Utilitanism)亦可译成“效用主义”,是新古典经济学的重要思想来源之一,而现代经济学则是建立在新古典经济学基础上的。

毫无疑问,对古典功利主义的任何批判都必将在现代经济学理论体系中引致某种“投射”,这就是笔者极力向经济学界推介盛庆珠先生创立的统合效用主义理论的原因。

进入21世纪以来,西方经济学者开始在一个更深刻的层面上反思现代主流经济学,尤其是以美国桑塔菲学派为代表的经济学家,如赫伯特·金迪斯(Herbert Gintis)、萨缪·鲍尔斯(Samuel Bowles)、罗伯特·博依德(Robert Boyd)和恩斯特·费尔(Enst Fehr)等人对主流经济学最重要的逻辑起点“经济人假设”进行的深入批评。

而这一批评恰好回应了盛庆珠先生对古典功利主义的批评,并在众多方面与盛先生创立的统合效用主义理论相契合。

本文即是从这一角度,尝试对盛庆珠先生的学术思想作一述评。

一、方法论个人主义与社会困境以新古典经济学为基础的现代经济学是建立在方法论个人主义之上的,其逻辑起点是所谓“追求个人效用最大化”的经济主体,即“经济人假设”。

伦理与经济学引言伦理学是研究人类行为准则和道德原则的学科,而经济学是研究资源分配和市场行为的学科。

虽然看似不相关,但伦理和经济学在现实生活中密切相连。

本文将探讨伦理与经济学之间的关系,包括伦理对经济决策的影响,经济学如何评估道德问题,以及两者如何相互为对方提供指导。

伦理对经济决策的影响在经济活动中,伦理问题经常涉及到道德与利益之间的冲突。

伦理原则可以影响人们的经济决策,例如在商业领域,企业家和经理人员面临着道德选择。

他们需要在追求利润最大化的同时尊重消费者权益、员工权益、环境保护等伦理原则。

如果一个企业被曝光违反伦理规范,可能会受到舆论和法律的压力,影响其经济利益。

另一个伦理对经济决策的影响是在个人层面。

一个人在决策时,可能会考虑道德价值观是否与经济利益相一致。

例如,一个有道德原则的个人可能不会从事非法活动或欺骗行为,因为这样做对他们的伦理观念有冲突。

这种内在的道德选择会影响他们的经济决策,从而影响整个经济系统。

经济学如何评估道德问题经济学在评估道德问题时,通常会使用效用理论。

效用理论认为人们行为的目标是追求最大的幸福感或满足感。

在经济学中,幸福感通常被表示为效用函数。

通过衡量个人或社会对不同选择的效用价值,经济学可以评估道德问题的影响。

例如,在资源分配的问题上,经济学可以评估不同分配方案对整体社会幸福感的影响。

如果一个分配方案导致贫富不均,经济学可以通过测量不平等的效用损失来评估其道德性。

经济学家可以在分配方案中引入纠正因子,以确保资源分配更加公平,并减少不平等的影响。

另一个例子是环境保护。

经济学可以评估环境保护措施对经济增长和生活质量的影响。

经济学家可以测量环境保护政策对污染减少的效用和经济成本的权衡。

这样的分析有助于制定可持续发展的经济政策,将道德原则与经济增长平衡起来。

伦理与经济学的相互指导虽然伦理和经济学有时会产生冲突,但它们也可以相互指导。

伦理学可以为经济学提供道德标准和价值观,使经济学更加注重社会公正和可持续性发展。

经济学伦理学研究经济活动中的道德和伦理问题在当代社会中,经济活动不仅仅是追求利益最大化,也是一个涉及道德和伦理问题的领域。

经济学伦理学作为一个交叉学科,探讨了经济活动中的道德观念、伦理原则以及道德行为的应用。

本文将对经济学伦理学研究经济活动中的道德和伦理问题进行探讨。

一、道德和伦理在经济活动中的重要性经济活动是社会的重要组成部分,而道德和伦理则是社会秩序和和谐运行的基石。

在经济学伦理学的研究中,经济学家和伦理学家都强调,道德和伦理在经济活动中的重要性不可忽视。

经济活动不仅仅是为了实现经济利益最大化,更需要考虑社会责任、公正和公平。

只有在道德和伦理的指导下,经济活动才能够更好地服务于社会,实现共同的利益。

二、经济学伦理学的研究内容经济学伦理学的研究范围广泛,包括但不限于以下几个方面:1. 道德和伦理的定义:经济学伦理学首先关注的是经济活动中的道德和伦理问题的定义。

什么是道德?什么是伦理?如何将其应用于经济活动中?这些都是经济学伦理学需要解答的问题。

2. 道德决策和道德原则:经济学伦理学研究经济活动中的道德决策和道德原则。

经济学家通过实证研究,分析经济主体在面对道德决策时的行为模式和原则,从而揭示人们在经济活动中的道德选择。

3. 公平和公正:公平和公正是经济活动中的重要道德原则。

经济学伦理学的研究探索了在资源分配、收入分配以及市场交易等方面的公平和公正问题。

这些研究有助于制定更为合理的经济政策和法规。

4. 社会责任和可持续发展:经济学伦理学研究经济主体在经济活动中的社会责任和可持续发展。

这一研究是为了解决经济发展与社会、环境的关系,探讨经济活动如何既实现自身利益又真正贡献于社会的问题。

三、经济学伦理学的应用意义经济学伦理学的研究对于现实经济活动具有重要的指导意义。

首先,经济学伦理学的研究有助于构建和完善经济伦理体系。

通过研究经济活动中的道德和伦理问题,我们能够建立一套符合社会发展需求的道德准则,为经济活动提供指导。

Beyond the Stalemate of Economics versus Ethics:Corporate Social Responsibility and the Discourse of the Organizational SelfMichaela DriverABSTRACT.The purpose of this paper is to advance research on CSR beyond the stalemate of economic versus ethical models by providing an alternative per-spective integrating existing views and allowing for more shared dialog and research in the field.It is suggested that we move beyond making a normative case for ethical models and practices of CSR by moving beyond the question of how to manage organizational self-interest toward the question of how accurate current concep-tions of the organizational self seem to be.Specifically,it is proposed that CSR is not a question of how self-interested the corporation should be,but how this self is defined.Economic and ethical models of CSR are not models of opposition but exist on a continuum between egoic and post-egoic,illusory and authentic conceptions of the organizational self.This means that moving from one to the other is not a question of adopting different paradigms but rather of moving from illusion and dys-function to authenticity and functionality,from pathology to health.KEY WORDS:corporate social responsibility,economic and ethical models,economic,egoic and post-egoic approaches,narratives,organizational self,psychoanalysisIntroductionWhile the topic of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)has gained increasing attention in organiza-tional research,it seems that research in this areacontinues to be hampered by a fundamental perhaps ‘‘ideological divide’’(Matten et al.,2003:111)be-tween those who advocate an economic model of CSR and those who advocate an ethical model of CSR (Argandona,1998;Joyner and Payne,2002;Kapelus,2002;Smith,2003;Stormer,2003;Swanson,1995).The economic model,largely fol-lowing Friedman’s reasoning (1962;1970),suggests that the social responsibility of a corporation goes no further than the obligation to maximize share-holder wealth and that indeed to spend corporate resources on philanthropic causes asks executives to engage in moral judgment for which they are not qualified and which,hence,is unethical (Hill et al.,2003;Schwartz,1998;Smith,2003),while the ethical model,based largely on Carroll’s model of CSR,goes beyond economic performance to in-clude legal,ethical and discretionary responsibilities (1979;1999)and assumes CSR should be under-taken for ethical or normative reasons alone (Windsor,2001).As such,the debate in research still seems to be whether or not corporations should be primarily self-interested,however enlightened such interest may be (Smith,2003),focusing on profitability and what is good for business or whether they should adopt a less self-centered,more other-centered paradigm,in which the shareholder is not privi-leged relative to other stakeholders and in which the corporation sees itself connected to and responsible for the larger community in which it exists,from the local community,to national and even global society (Gioia,2003;Stormer,2003;Swanson,1995).The stalemate that the division over these models seems to have resulted in‘‘In other words,there is nothing behind the curtain except the subject who has already gone beyond it.’’(Slavoi Zizek)1Journal of Business Ethics (2006)66:337–356ÓSpringer 2006DOI 10.1007/s10551-006-0012-7(Matten et al.,2003),despite various efforts aimed at their integration(Swanson,1995,1999),has had several consequences for the research and practice of CSR.For one,as a result of the two models, there is no universal and clear definition of what CSR is(Hill et al.,2003;Smith,2003;Van Mar-rewijk,2003).Two,there is continuing debate over whether research should investigate CSR relative tofinancial performance with some arguing that the case has to be made that CSR is good for business(Joyner and Payne,2002;Schmidt Albin-ger and Freeman,2000),while others argue that if it were good for business,we would not be talking about CSR in thefirst place(Kapelus,2002)and still others arguing that efforts to link CSR with profitability denigrate or even render meaningless the idea of CSR,since an ethical choice that can be justified by instrumental gain is not an ethical choice to begin with(Stormer,2003;Windsor, 2001).Third,and importantly,researchers seem to be unable to agree,given the two models,how CSR should be implemented or measured in practice,with economic models arguing for eco-nomic decision-making rules and outcome mea-sures(see for example McWilliams and Siegel, 2001),while ethical models argue for moral and normative evaluations based,for example,on the moral development of the corporation,values-based decision-making models(Zwetsloot,2003) and activities and outcome measures that demon-strate the organization’s commitment to relation-ships with external stakeholders,long term benefits to society,large scale wealth redistribution and connectedness with larger communities(Kapelus, 2002;Smith,2003).The purpose of this paper is to advance research on CSR beyond the stalemate of economic versus ethical models by providing an alternative per-spective,one that may serve to integrate existing views and allow for more shared dialog and re-search in thefield.Such dialog would eventually resolve definitional problems,address questions on what to investigate and resolve issues surrounding how to implement and measure CSR.Specifically, the perspective proposed here is one that examines CSR not in terms of economic versus ethical considerations but instead focuses on the notion of self.That is,rather than suggesting that CSR hinges on whether the corporation is self-interested or not,it is proposed that CSR hinges on how the self is defined.Specifically,it hinges on what or who we are referring to when we use the term the corporate self that is to be socially responsible in some way.Drawing on postmodern,discursive and psychoanalytic conceptions of the self,the paper argues that both economic and ethical models of CSR are based on theflawed assumption of a uni-dimensional,stable and simplistic conception of the corporate self,which then leads to overly narrow conceptualizations of social responsibility or conceptualizations that erroneously pit corporate self against non-corporate others(e.g. business versus society)(Roberts,2003;Solomon, 2004).The paper offers an alternative view of the corporate self as multi-dimensional,dynamic and complex,a self that,since it is continu-ously socially constructed,de-constructed and re-constructed,contains multiple identities and is fundamentally embedded in an evolving perception of another.The dualism of corporate self versus non-corporate self or business versus society and its resulting narrow conception of social responsibility(Kapelus,2002)are mere illusion,literally deceit of the ego.Behind such illusion,may rest the realization that since the self is never uni-dimensional,stable and simplistic,the corporation cannot conceive of social responsibility in terms of self versus non-self,connected versus disconnected self.Rather the corporate self only exists in the embedded relationships among various stakeholders.Therefore,its responsibility is always to be self-interested within such a conception of the self as multitude,as constructed,changing and complex narrative of a self that exists only in relation to others.As such CSR is not a question of whether or not organizations are or should be ethical,which they seem to be by definition(Roberts,2003),or whe-ther or not they are or should be connected to external stakeholders,which they also seem by def-inition(Solomon,2004),but whether or not orga-nizations understand themselves to be so and thus whether or not they have an egoic,delusional conception of the self or whether they have an accurate conception of the true self in relation to338Michaela Driverothers.Based on this view,CSR can then be defined along a continuum from egoic to post-egoic self-understanding.Further,CSR theories and practices can be evaluated as narratives that fall somewhere along this continuum,where narrow,economic conceptualizations likely fall toward the egoic,illu-sionary endpoint and wider;ethical conceptualiza-tions fall toward the post-egoic endpoint of a more accurate self conception.The paper proceeds as follows.First,literature on CSR will be reviewed with respect to the economic and ethical models of CSR.Second,the notion of the self on which these models are based will be explored,compared and contrasted with conceptu-alizations of the self based on critical,postmodern and psychoanalytic organizational theorizing.Third, an alternative model of CSR will be developed,one that locates CSR relative to organizational self-conceptions on a continuum from egoic illusion to post-egoic authenticity.The paper concludes by discussing the implications of this perspective for research on CSR.Economic and ethical models of CSR There have been various efforts to reconcile the division that seems to dominate research on CSR seemingly co-existing in two distinct camps,one adopting an economic view,the other an ethical or normative one(Roberts,2003;Smith,2003; Swanson,1995).In a recent attempt,Solomon (2004)argues that the economic model of CSR in which business’only responsibility is to maximize its profits is based on aflawed assumption of ‘‘antagonism between individual self-interest and the greater public good’’(Solomon,2004:1021). Specifically,based on an Aristotelian approach to business,it becomes clear that‘‘[c]orporations are neither legalfictions norfinancial juggernauts but communities,people working together for com-mon goals’’(Solomon,2004:1026).As such cooperation and interdependence are not only a fundamental organizing principle but also that which make corporations ethical by definition (Roberts,2003).Consequently,to define CSR strictly in eco-nomic terms is to ignore the communal nature of organizations that are embedded in communities to whom they are responsible by virtue of why and how organizations exist in practice(Solomon, 2004:1023).That is not to say that CSR and financial gain are mutually exclusive,but rather that profit maximization based on self-interest wrongly defined as interest in an independent, autonomous and disconnected self,is not unethical but inaccurate as it ignores the interdependent, connected and communal nature of the corporate self(Solomon,2004).We will return to the no-tion of corporate self at a later point,but for now what is pertinent for purposes of this paper is the idea that economic models of CSR,while often criticized,seem to persist(Snider et al.,2003)and hence that the division in CSR of two camps,one economic and one ethical,continues to hamper the evolution of conceptualizations,theoretical advances and practical applications(Matten et al., 2003;Swanson,1995,1999).Specifically,while researchers are arguing over the validity of eco-nomic versus ethical models of CSR,they are unable to agree upon and develop universally ac-cepted definitions of CSR(Hill et al.,2003; Smith,2003;Van Marrewijk,2003).The absence of such definitions,in turn,hampers the opera-tionalization of concepts and its measurement and implementation in practice.For example,propo-nents of economic models typically focus on rules for making CSR related decisions and evaluations of outcomes based on economic orfinancial cost-benefit analyses(McWilliams and Siegel,2001).By contrast,proponents of ethical models investigate the moral development of corporations and the values that underlie CSR related decisions (Zwetsloot,2003)or the quality of relationships to and degree of connectedness with various external stakeholders and CSR related behaviors relative to long-term benefits to a larger social good,such as a more equal distribution of wealth in society (Kapelus,2002;Smith,2003).In short,the two models drive two different research agendas and parallel developments in the theory and practice of CSR.This of course hampers the exchange of ideas and the pooling of resources toward con-certed efforts(across the two camps)to have a more comprehensive theory of CSR that can be more easily implemented in organizational practiceBeyond the Stalemate of Economics versus Ethics339and have more impact at that.But before we follow this line of argumentation further,let us define and compare the two models in more detail.How the two models differWhile McWilliams and Siegel define CSR‘‘as actions that appear to further some social good, beyond the interests of thefirm and that which is required by law’’(2001:117),i.e.adopt a definition that goes beyond strict profit maximization and includes some if not all of Carroll’s(1979,1999)four dimensions(economic,legal,ethical and discre-tionary),they develop a model of CSR that suggests that corporations use cost-benefit analyses and economic models of supply and demand to deter-mine optimal levels of CSR so that engagement in CSR is not a question of ethics but rather of eco-nomics.So whilefirms may be profitable with or without CSR,the question whether they should engage in CSR is not a question of whether they ought to do so based on moral reasoning but of whether they canfind optimal levels of CSR investments given economic constraints and the costs versus the benefits of such investments (McWilliams and Siegel,2001).In a recent review of the literature on CSR, Windsor(2001)suggests that economic models of CSR still dominate the research and especially the practice of CSR.The author laments the fact that definitions of CSR are vague and contain no mini-mum standards to hold corporations accountable to. Moreover,it is suggested that CSR in practice seems to be mostly empty rhetoric and that what goes for responsibility may be responsiveness at best and,if strictly undertaken for profitability,amoral at worst. The author concludes that economic models do not only demonstrate a disregard for morality but are also based on theflawed assumption that what is good for business is good for society while in reality not accounting for the true cost of doing business and leaving it up to public policy to manage the public good.According to Windsor(2001),economic models fail to differentiate between short-run business im-pacts and the long-run alignment or misalignment between business and social interests and as such can be easily manipulated.Therefore,economic models of CSR may provide‘‘an‘economic theology’’’(Windsor,2001:240)but not a basis for moral choice particularly when it comes to unprofitable demands.Stormer(2003)echoes this idea suggesting that CSR has to move beyond short-sighted and overly simplistic economic models which assume thatfirms only have to take care of their profits while society takes care of itself.In truth,Stormer says,corporations only get more powerful while the rest is falling apart(2003).As such,the notion that economic behavior in itself is ethical behavior has to be debunked and economic models of CSR have to be discarded(Etang,1995)in favor of ethical models stressing that self-interested behavior for economic gain is not ethical or moral(Etang,1994).In a similar vein,it has been argued that concep-tions which seem to underlie economic models and what is defined as moral in corporations are based on a conventional rather than a post-conventional level of moral development(Gonzalez,2002;Logsdon and Yuthas,1997).CSR based on economic models and wealth maximization focus not on a universal moral imperative but on a narrow conception of what the corporation must do to be responsible to the share-holder(Gioia,2003).It has been suggested that only the adoption of models that stress a post-conven-tional moral ethos beyond conformity and self-interest(Etang,1994;Stormer,2003)will eventually lead to the reduction of ethical dysfunction in orga-nizations(Snell,2000).Only such a model will encourage truly ethical behavior,that is,behavior that is ethical not only in its outcome but ethical because of its motivation(Etang,1994).Even researchers who seem to agree that CSR consists of more than economic responsibility still suggest that economic and legal considerations seem to dominate the practice of CSR,especially in the US(Pinkston and Carroll,1996)and that making the business case that CSR is good for the bottom line is an important argument for convincing busi-ness organizations to engage in CSR(Joyner and Payne,2002).Even when a non-economic model of CSR is adopted,the assumptions and mental models (Windsor,2001)of the economic model seem to prevail in theory(Pava and Krausz,1997)and in practice(Introcaso,1997).Even authors suggesting340Michaela Driverthat the economic model of CSR falls short,which is clearly not true in all cases(Sethi,2003),remain within the economic paradigm by suggesting that to getfirms to engage in CSR economic constraints have to be changed.Specifically,economic con-straints have to be changed so that it would be either profitable to engage in CSR or unprofitable not to engage in it(Sethi,2003).Such reasoning seems to be supported by studies focusing on the economic payoffs of CSR demonstrating that in some cases CSR enhances the attractiveness of corporations as employers(Schmidt Albinger and Freeman,2000), leads to more satisfied employees who are less likely to leave(Riordan et al.,1997)and shows a positive link withfirmfinancial performance(Joyner and Payne,2002).However,economic constraints alone do not seem to increase CSR.Simply making the business case that it can be profitable to engage in CSR or even demonstrating that certain CSR behaviors have greaterfinancial returns forfirms does not ensure that more CSR practices are put in place or that such practices actually benefit a larger good.Carson(2003) claims that the economic model of CSR is based on the erroneous assumption that corporate self-interest automatically leads to the common good.Carson suggests that CSR and stakeholder theories need to include specific prohibitions against fraud and deceit because it can no longer be assumed that managers are moral agents who can be expected to act ethically based on economic constraints or pay offs alone (2003).The latter idea seems to be validated in a recent study showing that CEO incentives do not lead to better corporate social performance(McGuire et al.,2003).In a similar vein,one author suggests that economic models of CSR have shown their dark side in the recent era of downsizing during which employees are routinely and unethically discarded like outdated equipment(Miller,1998).There are no normative criteria in economic models to weigh so-cially responsible behaviors toward afirm’s share-holders whose wealth may be maximized through the cutting of labor costs against socially responsible behaviors towards employees potentially losing their jobs.Or rather,as long as it is just a question of economic wealth maximization for thefirm,stake-holders like employees may be considered irrelevant to CSR.Moreover,it seems that CSR motivated primarily by profit and a negative duty to avoid penalties seems to lead more to impression management than to concrete,sustained and responsible actions (Maignan and Ralston,2002).While most corpo-rations have adopted the language of CSR,this language reflects primarily economic concerns or does not reflect actual behaviors(Robertson and Nicholson,1996;Snider,Hill and Martin,2003), and is sometimes outright deceptive(Laufer,2003). In a similar vein,Roberts(2003)argues that economic models of CSR lead corporations to conceive of responsibility in narrow terms with financial concerns often leading to empty rhetoric and impression management rather than the responsible concern for other stakeholders(Clark-son,1995).Similarly,Korhonen(2003)has argued that in order to create ethical and sustainable CSR,a paradigm shift has to occur that leaves behind strict economic models of CSR.Such a paradigm shift seems to be necessary because economic concerns do not seem to lead to increased CSR unless a rarely seen concern for CSR and economic performance coincide(Poitras,1994).Moreover,Kapelus(2002) has found that economic models of CSR encourage managers to limit who is included in their definitions of community and their delimitation as to whom they must be responsible for,leading to economi-cally justified solutions in practice(Introcaso,1997). It seems that economic models of CSR not only lead to narrow conceptions of responsibility but are en-acted in practice in such as way as to undermine the common good through opportunistic behavior (Abbarno,2001).Even if they are not enacted in opportunistic fashion,they appear to be based on limited and short-sighted information that simplifies the complex relationships,impacts and connections of global organizations today(Zadek,1998).The two models and conceptions of corporate selfIn summary,it seems that the economic models of CSR have been widely criticized as being too simplistic and leading to overly narrow conceptions of responsibility based on the fundamental assump-tion that there is a corporate self whose interest inBeyond the Stalemate of Economics versus Ethics341profit or wealth maximization must precede all other concerns.But even as these models are criticized and more ethical or normative alternatives are proposed, the fundamental assumption that the corporation is a self with narrowly defined interests persists.The difference seems to be that economic models of CSR condone this interest as ethical while ethical models criticize it as unethical,amoral or overly simplified.As such the debate seems to hinge on whether or how to manage the self-interest of cor-porations,not on whether the current assumption of the self is correct.Specifically,while some authors suggest that the corporate self has been too narrowly conceived (Matten et al.,2003),and others have proposed more communal,more inclusive models of corporations (Stormer,2003),the issue seems to continue to be that economic models better describe what corporations are:a unidimensional self that best serves its own interests.Conversely,ethical models use normative ideals and the idea that the corporation should view this self as connected,interdependent and communal relative to the system in which it co-exists(Stormer, 2003).As such the descriptive,economic models generating testable hypotheses of what is (McWilliams,2001)continue to clash with pre-scriptive models of what ought to be and CSR seems to vacillate between two end points on a continuum between facts and values(Swanson, 1999).Put simply,the debate around economic versus ethical models seems to be a debate be-tween two conceptions.One is a corporation that is a disconnected,simple self with uni-dimen-sional,stable interests,and the other that is an interconnected,complex self with multi-dimen-sional,dynamic interests taking responsibility for a greater common good.But it is not a question of facts versus values or of what is versus what should be(Swanson,1999)or indeed of ethics versus economics.I would like to argue that it is a question of the accuracy of the concept of self on which both models of CSR are based.Based on critical,postmodern and psycho-analytic conceptions of the organizational self,there is no such thing as a disconnected,simple self with unidimensional,stable interests;illusions that such a self may exist lead to dysfunction and pathology,which,as we will see,are exactly the issues sur-rounding economic models of CSR.Critical,postmodern and psychoanalytic conceptions of the organizational self Whether it is due to the rise of post-bureaucratic forms of organizing or has always been the case, critical and postmodern organization scholars agree that the idea of the organization as unified,stable, predictable and autonomous self does not reflect reality(Lippens,2001).Rather,the organization is constituted of multiple subjectivities and contested territories(Parker,2000)in which boundaries of what is self and non-self seem to shift continuously.The notion of self,what is in the interest or what is moral for this self,is continuously constructed,de-con-structed and re-constructed in various narratives (Hassard and Parker,1993;Hardy,2001;Lippens, 2001;McKinlay and Starkey,1998).From this per-spective,the question is not whether we can adopt models of CSR based on the assumption of a dis-connected,simple and unidimensional self with clearly defined interests and then argue over whether such models are more or less ethical.Rather the question is whether such models are even accurate given what we know about the contested and socially constructed nature of what we refer to as the orga-nizational self.This,in turn,means that it is not a question of whether corporations should view themselves as members of society,or an amalgam of multiple selves embedded in society that leads them to assess the cost of doing business by also considering the public goods they consume(Phillips and Eyres,2001).Instead,it is whether corporations are aware that they are such a member and that anything else is dysfunctional illusion.If we seek to apply consciousness(Pruzan, 2001),moral ethos and development to corporations (Gonzalez,2002;Logsdon and Yuthas,1997;Snell, 2000;Sridhar and Camburn,1993),it is important to recognize that corporations may also suffer from psychodynamic dysfunction(Gabriel et al.,1999)that affects moral ethos and development not based on ethical failure but based on more or less conscious processes of self-development and self-awareness. Though it is not my purpose to go into depth psychology and particularly the teachings of Jacques342Michaela DriverLacan–which elsewhere have been described as critically important to organizational studies (Arnaud,2002;Jones and Spicer,2004;Vanheule et al.,2003)–how self-development and concep-tions of the self may become dysfunctional has long been studied by can’s focus on a linguistic approach to psychoanalysis stressing the importance of language for our understanding of the conscious and especially unconscious dimensions of the human psyche is pivotal.Central to Lacan’s teachings is the idea that the conscious,rational speech of an individual is often misidentified as being the true subject or self(1977b).Actually,the rational speaking self engages mostly in empty speech,speech expressing an‘‘alienated reflection’’(Muller and Richardson,1982:70)in the ego.This speech isfirst acquired in early childhood when we learn to replace our experience of separa-tion from the mother and of a self that is fragmented and helpless with a reflection of the self in the mirror where we see a stable,unified and permanent image of ourselves.We accept this mirror image as our permanent‘‘I’’(Lacan,1977a).What we are unaware of is that this image is inauthentic.Like any reflection it is an inverted image of the original marked by various distortions.However,we proceed to build our ego around this distorted image,this‘‘miscog-nition’’(Muller and Richardson,1982:31).From that moment on the image we take to be our authentic self is really a distorted and external image. We become so used to this distortion that we see our self always in relation to external images andfinally do not just look in the mirror for our reflection but to others.As we become social selves,we look to others for the reflection of our self that represents what we have come to expect,namely the image of a stable, uni-dimensional self(Lacan,1977a).As we construct this self in speech with others,we defend against anything that might make us aware that we are not this stable,uni-dimensional self.We continue to assert in the empty speech of our rational self that this image we have is indeed our authentic self or ually with the help of psy-choanalysis,we can work through empty speech, which is not only inauthentic but leads to a variety of pathological behaviors,and arrive at full speech and a more authentic conception of the self(Lacan, 1977b).In full speech we are able to express our self not as the alienated image of the ego but as subjects embedded in a larger,universal order,what Lacan refers to as the symbolic order(1977b,c).This universal order is the structure and language of our unconscious.As such,it is transindividual,that is,it is the same universal order in which all persons are embedded.Authentic subjectivity or selfhood is the discourse of this universal order in which we are all embedded as fragmented,momentary,ambiguous and multi-dimensional penetrations.When we realize this,we can become less frus-trated with the fruitless chase for reflections of our self that are stable,consistent,integrated and permanent(Lacan,1977d).Specifically,we can recognize that the empty speech of the ego does not represent our authentic self but only a distorted image.From there we can try to create full speech by constructing the self in a discourse that acknowledges the authentic self as fragmented, momentary,ambiguous and multi-dimensional. Most importantly,we can construct our selves in discourse with others who,we realize,are embedded in the same universal order(Lacan,1988a,b).So it is not a matter of leaving behind or shedding the alienated ego speech,which makes most of us ‘‘commonly’’pathological(Lacan,1977b),but a matter of working through this speech toward the discourse of a self not rigidly but dynamically defined,not disconnected and permanent but interconnected and changing.Through such dis-course,we can free our self of the rigid,frustrating and alienating structures of the ego,and instead experience our self as an ambiguous but highly creative process of narrative construction(Lacan, 1988b).What does all this mean for organizations? Organizations,like persons,are linguistic phe-nomena(Alvesson and Karreman,2000;Hassard and Parker,1993;Hardy,2001;Putnam and Cooren,2004).As such we can explore organi-zational action(Taylor and Robichaud,2004)and the construction and enactment of organizational selves via discourse at various levels of analysis (Hardy,2004)and as co-construction of multiple meanings that emerge in dialog among many voices(Cunliffe,2002).Specifically,the organiza-tional self is constructed and enacted through various narratives that reflect not only dynamics ofBeyond the Stalemate of Economics versus Ethics343。