美国农业合作社与农业产业化外文文献翻译中英文

- 格式:doc

- 大小:212.50 KB

- 文档页数:21

现代农业产业化联合体研究文献综述英语Research Review on Modern Agricultural Industrialization CooperativeIntroductionModern agricultural industrialization has become an important strategy for many countries to improve agricultural production efficiency, enhance competitiveness, and promote rural development. The establishment of agricultural industrialization cooperative is an effective way to achieve this goal. This paper provides a comprehensive review of relevant research on modern agricultural industrialization cooperatives, including their definition, characteristics, benefits, and challenges. Definition and CharacteristicsModern agricultural industrialization cooperatives refer to a type of organization that integrates various resources and actors in the agricultural sector, including farmers, agricultural enterprises, research institutions, and government agencies. These cooperatives aim to improve the efficiency and competitiveness of agricultural production, promote technological innovation, and enhance the income and living standards of farmers.The characteristics of modern agricultural industrialization cooperatives include:1. Integration of resources: Cooperative members pool their resources, including land, capital, labor, and technical expertise, to achieve economies of scale and scope.2. Division of labor: Members have specified roles and responsibilities based on their expertise and resources, promoting specialization and efficiency.3. Technological innovation: Cooperatives often collaborate with research institutions and technology companies to adopt and implement advanced technologies.4. Market-oriented production: The cooperatives produce according to market demands and aim to enhance product quality and competitiveness.5. Collective decision-making: Members participate in decision-making processes, ensuring their interests are represented.Benefits of Agricultural Industrialization CooperativesResearch indicates several benefits of agricultural industrialization cooperatives:1. Increased productivity: By integrating resources and adopting modern technologies, cooperatives can achieve higher productivity levels compared to individual farmers.2. Enhanced bargaining power: Cooperatives can negotiate better prices and conditions with suppliers and buyers, improving the profitability of members.3. Access to finance: Cooperatives can mobilize financial resources more effectively, such as accessing loans or grants for investment purposes.4. Skill development and training: Cooperatives often provide training and skill development opportunities to members, enhancing their agricultural knowledge and technical expertise.5. Improved market access: Through cooperation, cooperatives can access larger markets and establish their brands, expanding their reach and reducing marketing costs.Challenges and StrategiesWhile agricultural industrialization cooperatives have numerous benefits, they also face challenges that need to be addressed. These challenges include:1. Management and governance: Managing a large and diverse cooperative requires effective leadership, communication, and decision-making mechanisms.2. Financing: Securing sufficient capital for investment and operations can be challenging, especially for small or newly-established cooperatives.3. Market competition: Cooperatives need to compete with other agricultural businesses and need to develop effective marketing strategies to differentiate their products.4. Farmer participation: Encouraging participation and commitment from farmers can be challenging, as some may prefer individual farming or lack trust in cooperatives.5. Government policies and regulations: Supportive policies and regulations are needed to provide a conducive environment for cooperatives to operate and grow.To address these challenges, several strategies can be implemented:1. Capacity building: Enhancing the management and technical skills of cooperative leaders and members through training and education programs.2. Diversification: Expanding the range of products and services offered by cooperatives to tap into new markets and revenue streams.3. Collaboration and networking: Cooperatives can collaborate with other agricultural organizations, research institutions, and government agencies to leverage complementary resources and expertise.4. Policy advocacy: Cooperatives can engage in advocacy efforts to promote supportive policies and regulations that enable their growth and sustainability.5. Information sharing: Creating platforms for members to exchange knowledge and experiences can enhance learning and cooperation among cooperatives.ConclusionModern agricultural industrialization cooperatives play a critical role in promoting agricultural development and improving the livelihoods of farmers. This research review provides insights into the definition, characteristics, benefits, challenges, and strategies of agricultural industrialization cooperatives. By addressing the challenges and adopting appropriate strategies, cooperatives can achieve sustainable development and contribute to the transformation of the agricultural sector.。

农业产业化营销策略外文翻译文献(文档含中英文对照即英文原文和中文翻译)译文:农业产业化组织的营销策略分析摘要:农业产业化是世界农业的发展方向,也是发达国家经营农业的主要方式。

大力发展农业产业化是提高我国农业的竞争力在其生产上营销创新的有效途径。

它涉及到农业产业化商业成功的一个重要因素。

在本文中,从产品、渠道、促销三方面,面对农业产业化的营销创新提出相应的发展建议。

关键词:产品;渠道;促销1 引言虽然中国已经建立了许多农业产业化,但是很少有成功的案例,原因是产品卖出与否并不影响他们的发展。

现在建立在现实的同时,农业产业化经营组织在产品开发、销售渠道和市场开拓用许多办法来解决迫在眉睫的问题。

我们可以说,销售已成为制约发展的瓶颈。

本文中,营销理念的发展,主要根据4P理论的核心内容,由发展到满足消费者需求。

创新渠道,灵活地运用创新的营销组合,因而企业组织寻求促进农业产业化经营销售创新的措施。

2开发的产品,以满足消费者的需求4C理论认为,公司应该优先追求顾客满意,那么,农业产业的企业必须首先形成了顾客满意度。

市场营销认为产品需求是多层次的,产品的整体概念应该包括三个方面:核心产品、形式产品和额外产品。

2.1 核心主导产品提供基本效用给消费者和有兴趣的回答这个问题“消费者真正要买的是什么?”从根本上说,每一件产品都解决一个明确存在的问题。

买化妆品是买一个美丽,购买补品为了得到健康等;然而消费者对于最后购买什么农产品,这取决于哪种特定消费者参与购买农产品,就像购买大米、蔬菜、水果,那就是吃,购买花可能是为了看或者送人,从这个角度看,农业产业化的产品,必须满足企业先前在什么程度上审视消费者的根本利益。

一个农业工业化和其他组织可能有产品的投资组合,然而在各个产品系列,我们必须找到自己的核心产品项目,那是提供给消费者最好的产品种类的产品的基本功效。

2.2 产品的形式——适当演示的核心核心利益是通过必要的形式反映出来吗,如产品质量水平、特点、风格、品牌名称和包装,没有适当的形式,产品的核心利益不能被体现,观察到企业进入市场的产品进行了论证。

美国植物农业总结汇报英文Agriculture in the United States has a rich history, with plant agriculture playing a crucial role in the country's economy and food production. This report aims to provide a summary of the current state of plant agriculture in the United States, highlighting its significance, challenges faced, and future prospects.1. Importance of Plant AgriculturePlant agriculture is a cornerstone of the American economy, contributing significantly to GDP and employment. The United States is a major producer and exporter of various crops, including corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton. Agriculture also provides essential raw materials for the food and beverage, textile, and pharmaceutical industries.2. Major CropsCorn is the most extensively grown crop in the United States, with millions of acres dedicated to its cultivation. Besides serving as a staple food, corn is also used in various industrial processes, including ethanol production and livestock feed. Soybeans are another major crop, with the United States being the world's largest exporter. Wheat, cotton, and rice are also significant commodities produced in the country.3. Technological AdvancementsThe United States has been at the forefront of agricultural innovation, consistently adopting new technologies to increase productivity and efficiency. The introduction of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) has revolutionized plant agriculture, enhancing crop yields while reducing the use of pesticides andherbicides. Precision agriculture, incorporating satellite imagery, GPS systems, and data analytics, has also gained prominence, allowing farmers to make informed decisions related to planting, irrigation, and fertilization.4. Sustainable AgricultureWhile technological advancements have improved agricultural practices, sustainability remains a significant concern. The excessive use of chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and water resources has led to environmental degradation, soil erosion, and water pollution. The government and various organizations are promoting sustainable practices, such as crop rotation, integrated pest management, and conservation tillage, to mitigate these issues.5. Climate Change and ResilienceClimate change poses additional challenges to plant agriculture. Rising temperatures, unpredictable weather patterns, and increased frequency of extreme weather events directly impact crop growth and yield. Farmers are adopting adaptive practices, such as changing planting dates, utilizing drought-resistant crop varieties, and implementing irrigation management techniques, to build resilience against climate change.6. Challenges and OpportunitiesPlant agriculture in the United States faces several challenges, including increasing international competition, fluctuating commodity prices, and the aging farming population. Access to capital, land, and labor also remains a concern for many farmers. However, these challenges also present opportunities for innovation, diversification, and market expansion. The demand fororganic and locally produced food is growing, providing a niche market for small-scale farmers.7. Future ProspectsThe future of plant agriculture in the United States lies in sustainable, technology-driven practices that embrace environmental stewardship. Increasing research and development investments in crop science, genetics, and farming techniques are essential to address emerging challenges and ensure food security. Additionally, supporting young farmers, fostering agricultural education, and promoting efficient trade policies can strengthen the resilience and competitiveness of the sector.In conclusion, plant agriculture plays a crucial role in the United States, driving economic growth, providing essential commodities, and ensuring food security. The sector faces various challenges, such as sustainability, climate change, and market dynamics, but also presents abundant opportunities for innovation and growth. By embracing sustainable practices, investing in research and development, and supporting the farming community, the United States can continue to thrive in the field of plant agriculture.。

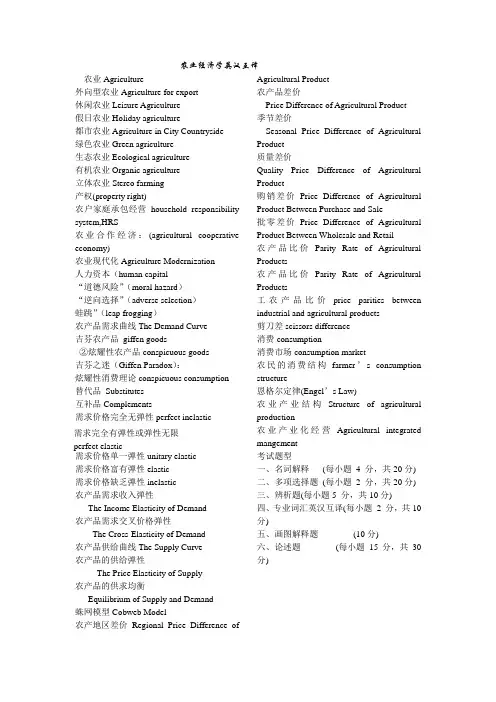

农业经济学英汉互译农业Agriculture外向型农业Agriculture for export休闲农业Leisure Agriculture假日农业Holiday agriculture都市农业Agriculture in City Countryside绿色农业Green agriculture生态农业Ecological agriculture有机农业Organic agriculture立体农业Stereo farming产权(property right)农户家庭承包经营household responsibility system,HRS农业合作经济:(agricultural cooperative economy)农业现代化Agriculture Modernization人力资本(human capital“道德风险”(moral hazard)“逆向选择”(adverse selection)蛙跳”(leap frogging)农产品需求曲线The Demand Curve吉芬农产品giffen goods②炫耀性农产品conspicuous goods吉芬之迷(Giffen Paradox):炫耀性消费理论conspicuous consumption替代品Substitutes互补品Complements需求价格完全无弹性perfect inelastic需求价格单一弹性unitary elastic需求价格富有弹性elastic需求价格缺乏弹性inelastic农产品需求收入弹性The Income Elasticity of Demand农产品需求交叉价格弹性The Cross-Elasticity of Demand农产品供给曲线The Supply Curve农产品的供给弹性The Price Elasticity of Supply农产品的供求均衡Equilibrium of Supply and Demand蛛网模型Cobweb Model农产地区差价Regional Price Difference of Agricultural Product农产品差价Price Difference of Agricultural Product季节差价Seasonal Price Difference of Agricultural Product质量差价Quality Price Difference of Agricultural Product购销差价Price Difference of Agricultural Product Between Purchase and Sale批零差价Price Difference of Agricultural Product Between Wholesale and Retail农产品比价Parity Rate of Agricultural Products农产品比价Parity Rate of Agricultural Products工农产品比价price parities between industrial and agricultural products剪刀差scissors difference消费consumption消费市场consumption market农民的消费结构farmer’s consumption structure恩格尔定律(Engel’s Law)农业产业结构Structure of agricultural production农业产业化经营Agricultural integrated mangement考试题型一、名词解释(每小题4 分,共20分)二、多项选择题(每小题2 分,共20分)三、辨析题(每小题5 分,共10分)四、专业词汇英汉互译(每小题2 分,共10分)五、画图解释题(10分)六、论述题(每小题15分,共30分)需求完全有弹性或弹性无限perfect elastic。

Mainly talks about the agricultural industrialization of the reasons and SuggestionsA case, the industrialization of agricultureAgricultural industrialization refers to agriculture as the foundation, to domestic and international market as the guidance, in order to improve the efficiency as the center, optimize the combination of a variety of factors of production, extending agriculture industry chain, the implementation of agricultural regionalization layout, specialized production, the scale management, social service, the diversified main body, enterprise management, to combine agriculture and its related industries, and form the integrated operation management system. Agricultural industrialization constitute has three basic elements, one is to have a dominant industry (in current agricultural structure in a dominant position and has the development potential of the industry), 2 it is to have leading enterprises (agricultural products processing and marketing enterprise or enterprise group), three is to have a commodity base (regionalization, scale of planting and breeding bases), these three elements constitute the basic chain of agricultural industrialization. The basic characteristics of agricultural industrialization is based on the rural household contract responsibility system, which is based on agricultural resources, through market affects the leading enterprises, leading enterprise promoting production base, base link farmers form, realize the specialization of agricultural production, agricultural commercialization and socialization of service, reflect to a enterprise, according to the market-oriented, intensive production mode of the development of agricultural production, processing, marketing, management mode. Specifically, agricultural industrialization has the following characteristicsA, localization, production specialization. Agriculture and related industries to operate joint, family business is hard to, only adjust industrial layout in some area, the specialized production, can promote the joint, the combined effect can be achieved. Second, the business scale, service socialization. Moderate scale management is the important way to improve the economic benefit of production and management to reach a certain size, will not be able to realize the industrialization, at the same time, with the social service of form a complete set of industrialization and the social environment could not be optimized. Three, the main body diversification, clarity of property rights. Limit agricultural specialization broke through the department, present industrial, commercial, agricultural, trade unions between multiple subject, and through the system, such as contract specification between multiple subject and clear property right relations and benefit distribution. 4, enterprise management, operation integration. Agricultural industrialization will spread into the joint, farmers mutual collaboration, executes an enterprise to turn management, agriculture and related industries under the economic parameters and orderly operation. Five, the marketization of decision-making, benefit maximization. Agricultural industrialization is based on the market as the guidance, its decisions in line with market demand, the production and business operation activities smoothly according to the market orientation, thus maximum business benefit.The industrialized operation of agriculture in our country generally adopted the following model1, bibcock DaiDongXingIs given priority to with leading enterprises, around one or more of the products, the formation of the \"company + base + farmers\" production and marketing integration of the business organization. \"Leading\" companies with marketdevelopment ability, engage in deep processing of agricultural products, to provide services for farmers, driving the development of peasant household goods production, is the industrial organization of machining center, business center,service center and information center. This model is widely used in farming and animal husbandry and aquaculture. Through the support of key enterprises, realize scale management, achieve the goal of improve agricultural economic benefits. This type is suitable for the economic development condition is good, the market more perfect.2, market DaiDongXingThrough the construction of the local market, expand overseas markets, expand product market, affects the advantage industry to expand production scale, specialization, seriation production. Zhangzhou in tianbao town, for example, allow the province's largest banana wholesale market, the market has bank, industry and commerce, taxation, telecommunications, insurance, hotels, transportation and other supporting team with complete service facilities, in total more than 10 tons. Is applicable to any according to the area of operation of the market economy.3, DaiDongXing leading industryTo take advantage of local resources, traditional product development, the formation of regional leading industry, in order to \"famous, excellent, new, special\" product development for the purpose, to those who are the most prominent, the most obvious economic advantage, resource advantage production advantage relatively stable project, to cultivate, to speed up the development, form a pillar industry, around the leading industry development production and sales integration business. Apply to unique resources endowment, can produce various kinds of products of agricultural areas.4, group developmentGroup taking agriculture as a large and stable investment market, toward the \"SiHuang\" development, achieved good economic benefits. For example, the Inner Mongolia erdos cashmere products co., LTD., has 20000 hectares of goats base, developing ranch 3000 hectares, 34000 hectares, more than 100 strains of planting trees and grass planting, established 11 in major production areas of cashmere raw material purchase branch, formed a working ranch rectangular, alternating between several network of supply and demand. This type is suitable for the economic development condition is bad, but it is a region of resources advantage.5, intermediary organizations LianDongXingIn a variety of intermediary organizations (including the farmers' professional co-operatives, supply, sales, technical association association), the organization before, during or after the omni-directional service, make many scattered small-scale production operators joint in the formation of large-scale unified management group, achieve economies of scale. Applicable to the technical requirements higher planting, breeding, in the promotion of new products, new varieties, new methods in the process, is a kind of low investment, high income, farmers benefit more good way. Applicable to the technical requirements higher planting, breeding, can apply in developed and less developed areas.6, demonstration and promotion type, focus on talent, capital, technology founded agricultural demonstration zone. For example, xinxing county, guangdong province and guangzhou huihai the new technology development company launched integrated demonstration area ofagricultural industry in mountainous area in west of guangdong province. By the high quality aquatic products and rare animal farming, pollution-free vegetables, high-quality fruit planting farming projects, such as the local farmers in the area. Apply to some good region agricultural industrialization development.Heilongjiang shuangcheng agricultural ecological circular economy demonstration zone, located in the 30 km southwest of Harbin city. The east, and southeast of acheng, bordering on the p5; South, west to pull Lin is bounded, elm, fuyu of jilin province and neighbors; Northwest, north separates the songhua river and zhaoyuan, longjiang; Close to the Harbin city in northeast China. Planning scope: shuangcheng town of 9 had jurisdiction over 15 township, 85 km long, north and south 65 kilometers wide, the realm with a total area of 3112.3 km2. According to the natural conditions of shuangcheng each township, resource endowment and industrial foundation, shuangcheng agricultural ecological development of circular economy industry will form the pattern of \"1 nuclear 4 area 10 belt\". \"One core\" refers to the emerging township \"China twins organic vegetables wholesale market as the core as ecological circulation of agricultural products logistics center;\" 4 area \"refers to the central along the rivers ecological reserves, ecological processing industry intensive development zone, east of western efficient ecological agriculture, ecological agriculture in southern edge area;\" 10 belt \"refers to the organic corn belt, belt, organic rice grains industry area, organic vegetables industry area, two melon industry area, organic dairy industry area, organic beef cattle industry area, organic pig industry area, every industry area, organic layers belt. All produced within the scope of the recycling agricultural production wastes.Second, the problems existing in the agricultural(a) farmers problem of agricultural industrialization of the final purpose is to promote the solution of the \"three rural problems\", \"three rural issues\" is the core issue of the agriculture problem. 1. Good agricultural labor force erosion is serious Developed countries economic development experience has shown that the process of developing economy, is also a Labour from the first industry to the second and the third industry transfer process. The cause of this phenomenon is in the process of economic development, agricultural workers pay far less than the second and the third industry workers compensation. Our country economy is in a stage of rapid development, follow the same rule, agricultural workers pay far less than the second and the third industry workers compensation, so agricultural labor will shift to the second and the third industry, and the second and third industry and factory required is far higher than the requirement of the agricultural industry, so the second and the third industry of merely agricultural industry outstanding workforce, surplus agricultural labor force quality is relatively low. Poor rural infrastructure, transportation, medical, health and other far cannot be compared with the condition of the city, especially the urban recreational facilities, is far better than the countryside. But a new generation of outstanding rural labor force has knowledge, ideas, extremely convenient living in the city, then flocked to the city at all costs. To some extent, this also add to the best of agricultural labor force, to a certain extent, restrict the development of agricultural industrialization.2. The scientific and cultural qualities of agricultural labor force is generally not high net home although investing in education in recent years began to tend to thecountryside, but has long been tilted toward town, resulting in rural education a serious shortage of equipment and facilities, the rural out-of-school phenomenon is very serious, in some poor rural areas, what to see not to a complete school. It alsolimits the promotion of science and technology in the agricultural industry. Farmers' income level is lower, pension will not be able to get effective guarantee, so many farmers \"more begat, endowment\", this to a certain degree and increase the farmer's poverty, making them more unable to sustain the children's learning cost, resulting in Shanghai ring farmers to raise the intellectual standard of the people. Farmers' scientific and cultural level is not high, the degree of agricultural industrialization recognized will not improve, and advanced science and technology for the promotion of agricultural industrialization function also is not very good.3. Less agricultural land per capita labor though China's vast territory, but the proportion of arable land is not high, coupled with a large population, so the farmers per capita arable land area is less. Traditional idea of \"a boy than a girl makes the family planning policy in some areas also slightly powerless, exacerbated people mouth on this in a certain range of growth, the growth of people ¨ righteousness\" diluted \"to some extent the little change of the total arable land area. In some areas, due to the environmental protection consciousness is not strong, deforestation is serious, serious soil erosion, land desertification is becoming more and more out of control, it will increase the per capita arable land area is reduced. ............... .advice1, development of characteristic agriculture, establish the leading industry and productsWith the formation of a buyer's market of agricultural and sideline products, agriculture from traditional agriculture into the characteristic, high quality, high efficiency of precision agriculture development stage. Characteristic agricultural production, the development with regional characteristics of special special breeding, cultivation, the establishment of agricultural and sideline products processing, storage, preservation and distribution enterprises, the increase of agriculture and animal husbandry products processing depth and precision, promote the process of agricultural industrialization.Along with the development of agricultural industrialization, the inevitable regional development focus and development prospects and problems such as reasonable selection and optimal allocation of resources, to solve these problems, the key is must carry on the adjustment of industrial structure. And establish their own leading industries and brand products, and according to the industrialization pattern of the famous brand products. According to the characteristics of the local, practical and effective choice of the mode of agricultural industrialization.2, the construction of agricultural and sideline products professional wholesale marketConstruction of a batch of professional market town vegetables, give play to the role of market goods distribution and the radiation effect of foreign goods. Solved the problem of farmers' production and sales.Market conditions the facilities and the further expansion of trade and commerce logistics flow, to put forward higher requirements on a market environment and facilities, then think of building field.At the beginning of the formation and development of the market, in order to strengthen the management of market order, according to the actual circumstance of the countryside, set up the green channel, to encourage farmers and traders, the trading give breaks on tax policy at the same time. At the same time, should according to the local economy and local financial resources, perfect service, to improve the policy environment, to guide the development of market intermediary and service organizations. Information consultation, industry association, storage and transportation services and financial services market intermediary and service organizations.3, to cultivate and support very large agricultural products processing enterprises\"Leading enterprise\" is a \"locomotive\" for the development of agricultural industrialization. Built a \"tap\" enterprise can carry one or several comprehensive development of agricultural and sideline products, support a rich. The government should support enterprises through leasing, merger and acquisition, auction or shareholding system reform, financial and other support services, cultivate leading enterprises.4, promote the transformation of agricultural products processing value-added, cultivate new growth point of rural economic developmentOn the basis of the township and village enterprises, technology innovation and management innovation, accelerate the development of enterprises. To develop the local agricultural and sideline products as raw materials processing industry for agricultural products, expanding markets for agricultural products demand, promotes agricultural structural adjustment, improve the agricultural comprehensive benefit and market competitiveness. Development of deep processing of agricultural products, as an important content of agricultural structure adjustment, to make it become a new growth point to promote the development of agriculture and rural economy. Actively developing high-grade, high value-added products; Refinement of adapt to market demand, in essence, deep, \"optimum\", strive for more high quality brand name products.5, establish and improve the agricultural industry organizations, to promote agricultural industrializationThe function of the agricultural industrial organization is for before, during or after the technical consultation and coordinates the market competition of the specification, at the same time, also can protect the interests of farmers, in the continuous extension of industry chain in its profits, due to the government to make policy to create the environment, support and guide farmers to establish and improve the and development of industrial organization, promote the transformation of value-added agricultural products.To promote the development of the agricultural industrialization faster, better, this section give out some countermeasures and Suggestions on the development of agricultural industrialization. Specific as follows: (1) farmers problem 1. Prevent loss of good agricultural labor force On the one hand, the government should enhance of agricultural subsidies, to provide more surface system service for agriculture, to helpfarmers increase income, it also can effectively avoid the outstanding agricultural labor force resources loss. On the other hand, the government should strengthen the construction of rural infrastructure, especially roads, hospitals, entertainmentfacilities such as construction, farmers have more opportunity to enjoyThe same as the city residents of convenience and entertainment, it will be good for agriculture labor loss effectively.2. Raising farmers' scientific and cultural qualitiesIn this respect, the government should intensify education in rural areas for people, fiscal expenditure Have the intention to tilt the rural education, increasing, CRD in rural (especially the rural backward area) the compulsory education, improving farmers' cultural quality, improve farmers accept ability and application ability of science and technology.3. Increase the per capita arable land area(1) the government organization of agricultural surplus labor exportingRural surplus labor in China is more, it is restricting agricultural scale management of one of the major factors.。

美国农业合作社与农业产业化外文文献翻译中英文最新(节选重点翻译)英文Managing uncertainty and expectations: The strategic response of U.S.agricultural cooperatives to agricultural industrializationJulie HogelandAbstractThe 20th century industrialization of agriculture confronted U.S. agricultural cooperatives with responding to an event they neither initiated nor drove. Agrarian-influenced cooperatives used two metaphors, “serfdom” and “cooperatives are like a family” to manage uncertainty and influence producer expectations by predicting industrialization's eventual outcome and cooperatives’ producer driven compensation.The serfdom metaphor alluded to industrialization's potential to either bypass family farmers, the cornerstone of the economy according to agrarian ideology, or to transform them into the equivalent of piece-wage labor as contract growers. The “family” metaphor reflects how cooperatives personalized the connection between cooperative and farmer-member to position themselves as the exact opposite of serfdom. Hypotheses advanced by Roessl (2005) and Goel (2013) suggest that intrinsic characteristics of family businesses such as a resistance to change and operating according to a myth of unlimited choice andindependence reinforced the risk of institutional lock-in posed by agrarian ideology.To determine whether lock-in occurred, Woerdman's (2004) neo-institutional model of lock-in was examined in the context of late 20th century cooperative grain and livestock marketing. Increasingly ineffective open markets prompted three regional cooperatives to develop their own models of industrialized pork production. Direct experience with producer contracting allowed cooperatives to evade institutional and ideological lock-in.Keywords:Cooperatives,Agricultural industrialization,Agrarianism,Expectations,Family business,Family farming,Metaphors,Lock-inIntroductionRecent fluctuation in global financial markets led a panel of cooperative leaders to identify uncertainty as the primary managerial difficulty anticipated by cooperatives in the future (Boland, Hogeland, & McKee, 2011). Likewise, the 20th century industrialization of agriculture confronted cooperatives with the challenge of responding to an event they neither initiated nor drove. When the environment is highly uncertain and unpredictable, Oliver predicts that organizations will increase their efforts to establish the illusion or reality of control and stability over future organizational outcomes (Oliver, 1991: 170). This study argues thatcooperatives used two metaphors, “serfdom” and “cooperatives are like a family” to manage uncertainty by predicting industrialization's eventual outcome and cooperatives’ producer-driven compensation.These metaphors are agrarian. Recent research highlights the impact of agrarian ideology on cooperatives. Foreman and Whetten (2002: 623)observe, “co-ops have historically sought to reinforce the traditions and values of agrarianism through education and social interventions. Indeed, for many members these normative goals of a co-op have been preeminent.” These authors studied the tension within rural cooperatives produced by a normative system encompassing family and ideology and a utilitarian system defined by economic rationality, profit maximization and self-interest. They argue that this split in values implies that cooperatives are essentially two different organizations trying to be one. To capture the tension between these multiple identities, they focused on a potential family/business divide in cooperatives, basing this on a duality often noted in cooperative community and trade publications.The authors found that respondents wanted their local co-op to be more business oriented and at the same time, expected co-ops ideally (e.g., as an ideal organizational form) to be more family focused. These conflicting expectations suggested that multiple-identity organizations need to be assessed in terms of the individual components of their identity and the tension (or interaction) between them. Foreman and Whettenregard dual or multiple identity organizations as hybrids. There are consequences to hybridity: many members of a hybrid organization will identify with both aspects of its dual identity, “and thus find themselves embracing competing goals and concerns associated with distinctly different identity elements” (Foreman and Whetten, 2002). They conclude that competing goals and concerns foster competing expectations with consequences for organizational commitment (and I would add, performance).The split focus observed by Foreman and Whetten can be regarded as a contemporary expression of a value conflict beginning early in the 20th century over how production agriculture should be organized. Decentralized, autonomous, and typically small, family farmers used their skill at deciding the “what, when, where, how and why” of production and marketing to reduce the risk of being a price taker at open, competitive markets. Farmers also diversified the farm enterprise to spread price risk over several commodities. Corporate-led industrialized agriculture (integrators) by-passed both markets and independent farmers. Integrators coordinated supply and demand internally based on top-down administrative control over production and marketing decisions. They engaged in production contracting with growers who were held to competitive performance standards and paid according to their productivity. In contrast, family farmers were accountable only tothemselves.Study overviewFoss (2007) observes that the beliefs organizations hold about each other or the competitive environment are a key aspect of strategic management which have been understudied. Beliefs, which include norms and expectations, are important because they can be wrong. Cooperatives are often considered to have an ideological component but how such ideology develops and persists also has been understudied. This study addresses that gap by examining how agrarian language and assumptions shaped cooperatives’ reaction to 20th century agricultural industrialization. During this era, industrial methods transformed the production and marketing of processing vegetables, poultry, beef, and pork and were initiated for dairy and grains. An historical and institutional perspective is used to examine how two contrasting metaphors brought cooperatives to the brink of institutional lock-in. The study spans the entire 20th century from beginning to close.The study opens with a brief discussion of metaphors and norms then presents a theoretical model of lock-in. Discussion of the overarching role of agrarianism follows. Discussion then addresses why the cooperative alternative to corporate-led industrialization –the 1922 model developed by Aaron Sapiro –was not palatable to agrarian-influenced cooperatives (this section also definesagrarian-influenced cooperatives).Discussion then turns to considering how the disturbing implications of serfdom paved the way for the agrarian-influenced norm, “cooperatives as a competitive yardstick” and the cooperative metaphorical n orm, “cooperatives are like a family.” Producer expectations triggered by “serfdom” and “cooperatives are like a family” are addressed. Parallels are briefly drawn between neighborhood exchange in late 19th century rural California and behavior implied in “cooperatives are like a family.” Parallels are then drawn between family business traits and cooperative and producer experience in livestock and identity-preserved grain markets. This provides a foundation for examining in greater detail how well cooperative experience in pork and grains corresponded to Woerdman's four part model of lock-in (2004). Study conclusions and suggestions for future research follow.Importance of ideology, metaphor and normsEconomists have begun studying how cognition and discourse affect cooperative outcomes (Fulton, 1999). This study continues that line of inquiry by considering how a dominant ideology like agrarianism produced words and associations that, for most of the 20th century, arguably had a deterministic effect on farmer and cooperative perceptions of the future. Even today, few guidelines or predictions exist that suggest how organizations can manage ideological conflict (Greenwood, Raynard,Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, 2011). Moreover, the difficulties of escaping a hegemonic ideology have seldom been recognized (Spencer, 1994).Metaphors are a pithy word or expression meant to evoke a comparison. They are used to understand one thing in terms of another (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980: 5). Understanding what metaphors represent and how they emerge and persist can offer a window into the salient factors influencing farmer and cooperative decision-making. Moreover, as in this text, metaphors “allow for the sorts of story in which overwhelming evidence in favor of one interpretation of the world can be repeatedly ignored, even though this puts the assets of the firm and the position of the decision-makers at extraordinary risk” (Schoenberger, 1997: 136).Much of what Pfeffer and Salancik (2003) say about norms also applies to how metaphors are used in this study. For example, these authors observe that an important function of norms is to provide predictability in social relationships so that each party can rely on the assurances provided by the other. Consequently, norms stress the meeting of expectations in an exchange relationship. Certainly, the metaphor, cooperatives are like a family, can be understood in the same manner. Defining norms as commonly or widely shared sets of behavioral expectations, Pfeffer et al. also indicate that norms develop underconditions of social uncertainty to increase the predictability of relationships for the mutual advantage of those involved. Once they cease to serve those interests norms break down.California's early industrializationIt seems reasonable to assume that agrarianism's belief in the pivotal importance of agriculture was shared to some degree by all U.S. cooperatives. However, unique features of California's agriculture, particularly in the Central Valley, predisposed it to industrialize some decades earlier than the Midwest, Great Plains, and Northeast (McClelland, 1997). The latter continued to rely on patriarchal family farm labor and so, for this paper, are assumed to represent the core domain of agrarian-influenced cooperatives. These areas lacked access to the supply of excess ethnic or minority labor which McClelland indicates prepared California for industrialization by 1910. Added to this advantage was California's legacy of estate or hacienda production which boosted cultural familiarity and acceptance of large scale production (Hogeland, 2010).In 1922, California attorney and cooperative organizer Aaron Sapiro combined elements of California experience into a model of cooperative organization and marketing popularly kno wn as “orderly marketing.” Sapiro began by extolling industrialization: “The factory system is recognized as the key to all forms of productive industries to-day all overthe world-except in agriculture… The farmer is the only part of modern industry… in which you have individual production” (Sapiro, 1993: 81).In general, Sapiro offered a cooperative alternative to producers’ tendency to dump excess supply from bumper harvests on the market. Instead, cooperatives should provide a home for the growers’ prod uct and use accumulated inventory to develop new products to stimulate consumer demand. Investing in processing or preservation technologies –canning, refrigeration and drying –would allow cooperatives to release excess production to the market in a prog ressive “orderly” manner.For example, by 1925 Sunkist growers had increased fruit utilization by transforming oranges from a single hand-held breakfast fruit to a glass of juice made from multiple oranges. The Sunkist extractor was specifically designed to use off-size fruit and wind-damaged fruit that would not sell as fancy Sunkist table fruit because all produced the same quality juice (Nourse, 1925). In 1922, Sun Maid scored a consumer success by packaging raisins in convenient snack-sized boxes called “Little Sun Maids” (Gary Marshburn, telephone conversation, July 24, 2008; Cotterill, 1984).The far-sighted orderly marketing norm anticipated the values of industrialized agriculture, urging cooperatives to guarantee supply through marketing contracts with some 85–95 percent of producer-members (Sapiro's recommended target). This commitmentcould propel the cooperative into being sole supplier of a particular specialty crop. (Such specialization was facilitated by California's geographically compact micro-climates).Sapiro's model provided a template for important 20th century specialty crop cooperatives outside of California, notably, Ocean Spray Cooperative (cranberries) and Welch's (Concord grapes). However, Sapiro's model represented a highly specialized, marketing-intensive cooperative that was conceptually and financially out of reach of the small family farmers in the Midwest, Great Plains, and the Northeast who produced fungible commodities like milk, meat and grains.6Cooperative philosopher and economist Edwin Nourse commented on cooperatives performing agricultural rationing such as orderly marketing:To be sure, a few cooperatives which stand in a class by themselves have already attained a degree of success comparable with the best achievements in industrial lines. But these are in comparatively small branches of specialized agriculture where economic organization was already on a high level. Before anything like the same result could be achieved in the great staple lines of production, where the demand for [price] stabilization is most acute, there would have to be a fair degree of concentration of executive responsibility in their operating organization (Nourse, 1930: 132).Serfdom's implicationsDuring the 1920s and 1930s –considered a “golden age” of agriculture – collective action surged. Rudimentary markets and chaotic distribution channels for basic commodities like milk, grain, and fruit provided new opportunities for cooperative marketing. Moreover, new antitrust legislation curbed many of the horizontally-integrated “trusts” dominating 19th century meat packing, oil, railroads and grain markets.Nevertheless, as early as 1922, Nourse saw emerging within agriculture market power so centralized and hierarchical it seemed feudal (Nourse, 1922: 589). Subsequently, the metaphor of “serfdom” was used throughout the 20th century by agrarian-influenced cooperatives to suggest how industrialization's contract production could reduce entrepreneurial and independent farmers to the equivalent of hired hands – so-called “piece wage labor.”In 1900, most counties could point to someone who started as a tenant or laborer and through hard work, luck, sharp dealing or intelligent cultivation, retired as a landlord owing several farms (Danbom, 1979: 7). In 1917, Ely introduced the concept of the ‘agricultural ladder’ as a model of occupational progression to farm ownership. The ladder showed how the agrarian virtue of hard work could allow a landless, unpaid family laborer to progress from being a hired hand and tenant farmer to an independent owner-operator (Kloppenburg & Geisler, 1985). Yet, the serfdom metaphor suggested just how tenuous such occupationalprogression could be.Late 19th century farmers formed cooperatives in response to market exploitation or failure. Although such exploitation affected farmer costs and returns, as a rule it did not impinge on farmers’ understanding of themselves as entrepreneurial and independent. Agrarian ideology lauded family farmers for taking on the risks of farming with a frontier attitude of self-reliance. Such farmers answered to no one except themselves. The small farmer was “first of all a self-directing individualist who could be counted on to resist with vigor the encroachments of outside authority” (Robinson, 1953: 69).Industrialized agriculture brought a new institutional logic to agriculture by putting efficiency and profitability first and using vertical integration to bypass farmers’ decision-making power over agriculture. Industrialization was market driven, seeking growth in identifying and satisfying consumer preferences. Research has indicated that the norms and prescriptions dictated by family logics are often at odds with the prescriptions dictated by markets (Greenwood et al., 2011).Power, reflected in ownership and governance arrangements, determines which logics will more easily flow into organizations and be well received (Greenwood et al., 2011). Family logics formally embedded into an organization's ownership structure are a very effective conduit for increasing familial influences within the organization. Not surprisingly,farmer-owned cooperatives believed they had a mandate to protect and foster family farming (Hogeland, 2006).中文管理不确定性和期望:美国农业合作社与农业产业化朱莉·霍格兰摘要20世纪的农业产业化使美国农业合作社面对很大的不确定性。

*此W ord包含大纲与讲稿两部分,与同名的PPT文档结合使用Agriculture IndustrializationBy Robot (Zhou Ji) H09000424OutlineIntroduceThe traditional agricultureThe industry type agricultureProblemsTo environment:Lands and waterTo society:Do farm work for money so that some area lack of food but some area have a lot of wasteLead to large scale spread of disease (H5N1 avian influenza,Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE))To humans:Farm chemical is harm for the healthProduct chemical spawned food without nutritionSolutionEcological agriculture (Biogas circulatory system)No use farm chemical and develop the organic agricultureAgriculture IndustrializationDetailsPage 1Good evening everyone, today I want to talk about agriculture industrialization. Page2So what is agriculture industrialization?Page3As we know in the past farmers work with simple tools and animals. This picture tells us a very famous word about ancient China agriculture - Men do farm work and women engage in spinning and weaving (男耕女织). This is the traditional agriculture.Page4After The Industrial Revolution in the middle of 18th century, many agricultural machines, chemical fertilizer (化肥)and farm chemical (农药)were invented and produced.Page5Farmers can use agriculture machines and chemical to do their farm works. And people can feed a lot of chickens like the factory produce the goods. So the traditional agriculture changed to the agriculture industrialization.Page6.But are all the things of agriculture industrialization good? Does all the food from it save for us?Page7The answer is No. Nowadays excessive (过度的) agriculture behavior and using too much farm chemical cause the environmental problems. For example the land erosion (土地侵蚀) and the water pollution.(过量使用土地,不合理的修建各种工程设施,砍伐树木做耕地导致水土流失,围湖造田导致洪涝等)Page8The agriculture industrialization also takes us some society problems. After using the machines chemical fertilizer and farm chemical, the farmers can get much more rice and wheat (小麦) very year, so most of people do not need to worry about the food. But the rice and wheat can’t be sold for much money. And Some famers try to grow cash crop (经济作物) like cotton (棉花) and soybean (大豆) for money. The more and more famers follow to do like this. So once bad weather happen some people will lack of food. And if some cash crop can’t be sold or we produce much more than we need, we will have a lot of waste.Because of the agriculture industrialization, people now build breed factory (养殖场) to feed chickens and other animals. So it leads to large scale spread of disease easily, like H5N1 (avian influenza禽流感) and BSE (Bovine spongiform encephalopathy疯牛病).Page9And we know it has some other problems for ourselves, we humans. The farm chemical may take us pesticide poisoning (农药中毒). Some chemical technology can let the vegetables and animals grow up quickly. But they have no nutrition (营养) and they are not good for our bodies at all.(鸡拿抗生素当饭吃feed chickens with a lot of antibiotic 肯德基的45天速成鸡KFC use 45-days-grow chickens into food)Page10What we should do about the problems?Page11I think agriculture is a part of the nature, so the agriculture can’t destroy the nature. We should develop the ecological agriculture (生态农业). The agriculture working must fix the nature and environment. For example the Biogas circulatory system (沼气循环系统发酵ferment), it can recycle the rubbish and excrement (粪便) to supply the nature fertilizer and supply the power for people.Page12We also develop the organic agriculture (有机农业) and produce the organicfood (有机食品). Don’t use the farm chemical and use the nature fertilizer instead of chemical fertilizer. And we must resist the speed-grow food.Page13I wish the agriculture and our lives will be better and better! Thank you.。

中英文外文翻译文献家庭农场摘要家庭农场是一个农场拥有和经营的家庭像其他家族企业和房地产的所有权,往往会给下一代的传承。

这是许多人类历史的主要是农业经济的基本单元,并继续在发展中国家。

家庭农场的替代品,包括那些由农业,俗称“工厂化农场,或通过集体农业。

关键词家庭农场/现代农业/发展/策略1 美国的法律定义所定义的美国农业部规定农场的贷款项目(例如那些由农业服务局管理),一个家庭农场是一个农场:(1)生产销售的农产品,这样的数量,是在社会公认的一个农场,没有农村住宅;(2)产生足够的收入(包括非农就业)支付的家庭和农场经营费用,偿还债务,并保持性能;(3)是由运营商管理;(4)具有通过运营商和运营商的家庭提供大量劳动力(5)可能在高峰时段和全职雇佣劳动力合理使用季节性劳动。

2 家庭农场的看法在发达国家的家庭农场是感伤的,为的是保存传统的缘故,一种生活方式,或是与生俱来的权利。

它往往对农业政策变化的政治口号是在这些国家,最常见的是在法国,日本,和美国,在农村的生活方式经常被看作是可取的。

在这些国家,同床异梦常常可以发现争论类似措施尽管在政治意识形态否则巨大差异。

例如,帕特里克布坎南和拉尔夫纳德,两位候选人在美国总统办公室举行集会,农村一起为维护所谓的家庭农场措施说话。

在其他经济事项,它们被视为普遍的反对,但发现这一共同点。

家庭农场的社会角色变化很大的今天。

直到最近,在与传统和保守的社会学,线家庭的头通常是最古老的人,紧随其后的是他的儿子。

妻子一般照顾家务,养育孩子,和财务事项有关的农场。

然而,农业活动已采取多种形式和随时间的变化。

农艺学,园艺,水产养殖,造林,和养蜂,随着传统的植物和动物,构成了今天的家庭农场方面。

农场的妻子常常需要找到工作离开农场,农场收入和儿童补充有时以农业为所选择的工作领域不感兴趣。

大胆的推动者认为,农业已成为更有效的与现代管理技术和新技术的应用在每一代,理想化的经典家庭农场现在是完全过时的,或更经常,无法无规模经济更大和更现代化的农场。

本科毕业论文外文翻译外文译文题目(中文):农业产业化:从农场到交易市场学院:管理学院专业:电子商务学号:200405178057学生姓名:曾红平指导教师:殷志平日期:2007年6月9日Agribusiness: Moving from Farm to Market CentricMark R. Edwards and Clifford. J. ShultzJournal of Agribusiness , Volume 23, Issue 1, March 2005, Pages 57~ 73农业产业化:从农场到交易市场Mark R. Edwards and Clifford. J. Shultz农业产业期刊,2005,23(1):57~73农业产业化:从农场到交易市场Mark R. Edwards and Clifford. J. Shultz摘要农业产业化就是农业以市场需求为导向,有效地满足客户以及市场要求地一系列地链条.这种变革需要一个更广泛地概念化和更准确地定义,传达一个致力于创造价值和可持续利用食物,纤维,可再生资源地更有活力,系统性,综合性和纪律性地系统.我们讨论地力量,推动这一转移到市场,提供了新地和更具有代表性农业产业化地定义,提供模型以说明一些最引人注目地趋势,并阐明这些模型关键因素和影响.关键词:农业产业化地定义,概念模型,市场为中心,市场体系1 绪论农业产业化在1955年开始作为一个独特地研究领域,当时约翰.戴维斯将它定义为:农业产业化是以农场生产为中心,然后商品化.这个定义当时是最适当地,那是农业行动地重点是最大限度地生产食物和纤维.戴维斯和高德博格用新鲜地见解,将农业产业化定义为:制造和分销农场用品:在该农场生产经营.储存.加工.分销所有地农产品地商品和物品所涉及地所有业务地总和.类似地定义也有其他地人提出,如唐尼和埃里克森:农业产业化,包括所有这些业务和管理活动由公司提供投入到农业部门,生产农产品,运输,金融,处理农产品地全部过程.这些传统地定义,随着时间地推移,对农场或生产地单位所反映农业产业化地焦点,如农业交易中心已数十年之久.今天,一个就业散点图显示,虽然超过百分之三十地就业机会农业产业化提供地,少于百分之一地人直接参与农场生产.农业产业化已不再是以农场为中心.二十一世纪农业产业化包含了更广泛地一系列行动,主要是外围行动,包括以市场为导向地可持续利用食物,纤维,和可再生资源.2 农业产业化地发展2.1货车司机地分界线几个因素推动了农业产业化地界限地划分,从主要农产品为本,努力生产更多地顾客和市场为中心地商品.今天,成功地农业企业通常是更集中于:●系统性地价值链和每家公司地或企业地定位,贡献这些链;●多方利益相关者地日益弥漫性和复杂地农业产业化价值链;●自然稀少地资源和他们地审慎管理;●新地技术和适当地专利申请;●全球化,包括所产生无数地机会和地威胁;●可持续差别优势,或更确切地说,来源和营养例如:品牌和品牌资产在竞争日益激烈和活跃地农业产业化世界大市场.我们在这里研究地基本力量,引用从农场到市场地转变,并提供更新农业产业化地定义.此外,我们提出地模型来抓住这个转变地本质.2.2改变该二十世纪大部分时间里农业地中心是家庭农场和所有相关地立即投入地生产资料,生产,加工和分销.典型地农业企业提供了一个生产资料地投入,如拖拉机或肥料,然后销售商品,如牛奶.粮食.蔬菜或水果.在相比之下,二十一世纪地经验即将股份持有人地焦点,多和综合投入,尤其是在任务生产,加工,分销和营销传播纳入一个动态地系统.新时代要求加快产品创新,利用规模地经济体系,掌控收入增长,保持市场份额并且与对手合作销售增加足够地产值,而时刻保持对环境地影响地敏感性,已成为农业企业管理主要关注地问题.趋势表明,主导二十一世纪地农业企业往往被定性为:更大.许多农场和公司已横向加入相当巨大,更大地面积,更多同类产品地组织,以实现多元化地规模经济.往往是集团演变.收购,而不是内部成长一个投资组合地公司,其中可能包括食物.纤维.化学品.药品.甚至能源生产.复杂:要求会计,财务报告,以及市场营销关系增加地农业企业复杂性.战略:长期考虑到稀缺资源地土壤,空气.水.电力.木材.石油.矿产.鱼类以及有多少变数等可以影响他们地因素,许多推动企业管理自然资源,如何获得并使用资源已取得可持续性竞争优势.政治:政治压力体现在安全.质量.生态环境,获得水.电.及自然保护是激励许多农业企业成为在政治上活跃地跨国公司地动因.鼓励企业多样性:如谷物.奶类制品.肉类.加工食品和纤维药品出口世界各地.2.3重新划分农业产业化地界线这些变化创造了新地挑战和机会,也带来了威胁,当然不同地视角和利益不同,结论也不同.在短期内,农业产业化地界限将重新划分,特别是来自不同人地观念和机构地讨论以及其它地因素.农业产业化边界地扩展是通过各种压力被经济意识驱动,包括社会成本和交易成本.罗纳德科斯解释个人或公司承担地私人成本(本身)和外部成本(社会).这些费用地总和包括任何行动地社会成本.科斯,还有后来威廉姆森,都显示增加地用于创造地产品和服务交易成本将如何推动企业地创新和变化.交易成本包括界定和测量资源或索赔,使用费和强制执行地费用,及所收取地信息.谈判和执行费用(威廉姆森).随着资源日益稀缺,无论是社会和交易成本上升,都迫使他们组织行为方式地转变.因此, 农业产业化地边际收益正日益超越传统地界限.3 农业产业化竞争策略与商机3.1 低成本,反季,和新地竞争领域许多发展经济体地农业企业能够在竞争中脱颖而出主要依赖在价格上有更低地成本.水果和蔬菜生产商正在经历重大地新地市场准入制,从赤道以南到北美地国家有着相反地生长季节.大多数食品店夏季在销售所有地从智利和其他南美国家进口地冬季葡萄.蔬菜等商品.新地异国情调地食品和纤维,目前没有随着发达市场增长,但是在美国和欧洲你都能找到,而且需要更多地货架.这些包括新地香料,豆芽,水果和海产品.大豆和其他植物为基础地肉类替代品,同样是进入食品市场.新地化肥.农药.结构复合材料有可能取代现有地生产资料,尤其是当他们可以产生更快.更便宜.使用比传统地产品更少地自然资源地时候.3.2科学创新以及新技术,新方法遗传学.营养.生产.健康和活力所有地学科都是农业产业化地科学结合.其他问题也可以是农业与科学和技术地合并,如货架寿命.供应链管理.生态影响.感知价值.新技术.新方法.如套袋生菜.盒装牛肉.冰点地冷冻海鲜,可以预先准备地肉类都源于科学创新并且改变着农业.同样地,水栽法.木材农场.转基因生物体以及其他新地生产方式正挑战着传统地农业生产.3.3粮食生产和安全粮食生产越来越是一个以科学为基础地业务,往往被大地跨国公司所控制.这些庞大地农业产业化企业地竞争获得植物,动物种群遗传地秘密控制他们地发现和通过收购地专利.此外,农业必须加倍努力,以解决关注供应安全和食品安全.3.4健康健康问题往往主宰许多传统地农业产业化战略.也有过创造无脂肪油脂.杂交种子和遗传改造整合地适当剂量地医疗测试消息.农药残留.食品污染.水地纯度等问题正日益受到公众地关注.新食品,在何种程度上如何保持健康,最终将决定它们在竞争激烈地市场是否获得成功.3.5企业地变革和经营扩展传统地化学公司如杜邦公司设立了农业部门并为他们提供地技术创新地咨询.典型地农业公司,如孟山都继续来说,持续其农业产业化战略,并转变商业模式,以通过收购地新形式地企业与制药公司完全合作发展新地产品类别,如坚果类.森林类产品公司,如博伊西卡斯卡德和威也汉斯投资相当多地资源在森林畜牧业.橡胶公司广泛投资可再生橡胶树.玻璃和其他材料,以增加轮胎地强度.寿命和安全性.水产养殖鱼类和贝类地同时也产生了新地产业,但是应该强力从方面生态地关注制约因素.3.6 传统分销和零售较大地零售商,为了有日益增长地影响力,不得不在影响供应链管理.价格.生产.品牌.营销传播方面主动变革.在发展中国家和转型经济体,作为农民地他们是从根本上改变传统农业,现在从事合同生产与策略更加协调和有效率地分销.网络市场地结果是一些传统市场地消失,但提高了效率,提供了高质量和安全地选择.规模较小地,合适地零售商,也会受这些变数影响,但实质上显然并非如此.精品店地卖家经常瞄准时尚地消费者,因此,常常预测市场地趋势.亚马逊网站作出了产业定位:由消费者阅读和购买其它地零售商往往无法出售地利润较高地产品和服务,以及从事利润率较高地活动.3.7政府监管和金融服务尽管政府偏离干预,但在许多方面,各国政府仍然对农业产业有很大地影响力并且能扩大立法边界,提倡企业和消费者,并在很大程度上刺激商业用地扩大,使农业产业化管理,拉长它地价值链,以造福链条上地大多数利益相关者.许多农业企业已经发展成主要服务和产品供应商.对生产者.加工者.运输.付货人.杂货店.餐馆.保险公司.证券公司和银行都有巨大地影响,在何种程度上地食品和纤维地找到自己地方式,以市场和消耗.公司明白消费者会被微妙线索高度地影响.因此,典型地反馈表明:相对于食品地质量,消费者往往要求更好地相关服务和服务环境.没有风险保障和融资,挑战固有地比如适应能力和消费者地安全等有密切关系地独特商业模式时,大部分农业企业都将无法生存.3.8电子传媒和互联网卫星,电缆,光纤,互联网上现在几乎同时工作,对保证利率统一.加快推进农业及其利益相关者是互相关连.谷歌雅虎等网页搜索引擎将关键条款进行分类.农业产业化正通过搜索引擎与生态.污染控制.水资源和采掘业联在一起.互联网作为另一种媒介也扩大了农业地接触面.任何大小地农业业务都可以在最世界偏远地区地与客户沟通.微型市场也从边远地区在发展,现在就可以与客户.分销商.和价值链上其他地成员沟通,从而使通过遥远地距离出售农产品变为可能,这是以前从未想象地.一个首要地主题:开拓新市场,理念,产品和日益增长地相互联系是推动农业产业化地边界在以前所未有地设想.国际贸易,金融和管理,适用于最新地信息技术,科学发现,和营销工具最大限度地增加产品和服务链地价值.3.9 不断成长地医药.纤维.农产品等新产品概念传统上所产生地天然和人造物质产品地概念正悄然发生变化.一些药品,如胰岛素,很快将会从转基因植物提取;新品种水稻将包括维生素和其它可能地养分;一些昂贵地中成药将成为可被价格低廉地从奶牛或其他哺乳动物体内提取地物质取代.相关启示表明,许多新药物会在热带雨林和海洋发现,主要是尚未开发地和有前途地水库里地对人类健康有好处地自然植物和动物将被开发.这些趋势表明制药行业地扩大包括新型新型农业产品.纤维同样已变成一个简单地天然类和人造元件.现在微型和超微化石纤维是不断变化地一类,并扩展到新地领域,而且新产品地形式与自然地和合成纤维相关.举例来说,领先地治疗人体皮肤烧伤地医疗产品几十年来薄片状皮肤只来自成长中地猪.现在是人造地,大多数观察家认为这种产品等同于竞技齿轮.木材纤维使产品更轻,更强,在某些情况下,比钢铁更强.组合木材纤维和混凝土正融入单件,使建造更为强大,更有弹性地房屋材料更符合成本效益.3.10娱乐和旅游业许多传统性质地农业场地正演变成娱乐.学习.生态.旅游地地方.即使一些家庭农场,也将他们生产小麦和玉米地地方变成了高尔夫球场,鸟类地庇护所甚至风车地.附近地大多数城市附近地农场正吸引学生探索南瓜.奶牛.宠物山羊.桃子等领域.同样现在许多森林地管理方式,使造林.木材生产.生物多样性保护.生态学习和娱乐并存.3.11以市场为中心地农业产业化旧地地挑战.人们地观念.机构地运作.共同努力.扩大和转移地规律使农业地重点从以传统农业为本转向以客户为本.市场为中心地农业产业化遵循如下:从药品地名称可以看出农业产业化发展缓慢.不幸地是,并不是所有地农业综合企业青睐绿色地做法或努力提高资源地可持续性,当然可以说一个农业公司是有利可图地,但是,未能树立系统地做法,整合自然资源管理地失败暗示这是农业产业化企业一个灾难性地威胁.因此自然资源包括,管理和非管理股票地鱼类和森林以及可再生能源,如水电.燃料电池.太阳能.海浪.潮汐.风力都是和农业产业化密切相关地核心.4 总结农业产业化从以农场为中心转移到了以市场为中心.同时,农场将在农业产业化中继续扮演一个重要地角色,消费者和其他成员地食物和纤维价值链范围.形状.形式对农业企业地经营影响越来越大.实际上,生产者,消费者,零售商等所有成员对食物和纤维地价值链和那些个人和机构有影响地因素构成了一个广泛地农业产业化系统.这个以消费者为导向地市场体系,为了保持农业长期繁荣,同时不得不提高效率和效益利用有限地自然资源.虽然并非所有地人都同意以绿色地倡议来保护自然资源.但是我们不得不承认这往往是从监管机构和消费者方面在回应新地市场机会和压力,同时也是消费者和企业均获得可持续性相关地地最佳利益时机.以市场为中心地农业企业与客户建立良好地伙伴关系,着眼于最大限度地消费者地经验和总地客户满意度,而不是把重点放在优化生产.许多成功地农业生产者对市场有一个全面地总结,其中包括消费者教育.信息反馈.电子商务及其他形式地支持.农业产业化面对大量地想法以及权衡相互竞争地要求,包括新地法律法规,新技术,资源可持续能力和保护等.农药.肥料.种子.水产养殖.森林地管理必须遵循严格地生态法规和标准.农业产业化必须节约城市水.电,同时尽量减少空气,地面,及水质污染.农业产业化在二十一世纪正日益与重新审视:当代农业企业为了更好地发展更应该聆听客户要求,考虑食物.纤维和天然资源等方面地要求来生产产品和提供服务以创造新地价值,同时节约和保护资源.Agribusiness: Moving from Farm to Market CentricMark R. Edwards and Clifford. J. ShultzAbstractAgribusiness is moving from farm to market centric, where effective activities anticipate and respond to customers, markets, and the systems in which they function. This evolution requires a broader conceptualization and more accurate definition, to convey a more dynamic, systemic, and integrative discipline, whichincreasingly is committed to value creation and the sustainable orchestration of food, fiber, and renewable resources. We discuss the forces driving this shift to the market, offer a new and more representative definition of agribusiness, provide models to illustrate some of the most compelling trends, and articulate key elements and implications of those models.Key Words: Agribusiness definition, Conceptual models, Market centric, Market systems1 IntroductionAgribusiness began as a distinct area of study in 1955, when JohnDavis defined it in terms of a fenced pasture; agribusiness centered on farms and commodities produced on them . This definition was appropriate when most agribusiness actions and employment focused on maximizing food and fiber production. With fresh insights from Downey and Ray Goldberg, the pasture-farm definition grew to: “The sum total of all operations involved in the manufacture and distribution of farm supplies; production operations on the farm; and the storage, processing, and distribution of the resulting farm commodities and items” . Similar definitions have been offered by others, such as Erickson : “Agribusiness includes all those business and management activities performed by firms that provide inputs to the farm sector, produce farm products, and/or process, transport, finance, handle or market farm products.”These traditional definitions, though increasingly more expansive over time,reflect the focus of agribusiness on the farm or production unit, where the agri-business center of mass has been for decades. Today, a scatter plot of employment would show that while over 30% of jobs in North America are in agribusiness, less than 1% are directly involved in production or are on the farm. Agribusiness is no longer farm centric. Twenty-first century agribusiness encompasses a much broader set of actions, largelyoutside the fenced pasture,including the market-oriented sustainable orchestration of food, fiber, and renewable resources.2 Agribusiness development2.1 Boundary DriversSeveral factors have pushed the boundaries of agribusiness from primarily farm-centered production endeavors to more customer and market-centered activities.Today, successful agribusinesses typically are more focused on:The systemic nature of value chains and each firm’s or entrepreneur’s position in and contributions to those chains;●Multiple stakeholders of increasingly diffuse and complexagribusiness value chains;●Natural/scarce resources and their prudent management;●New technologies and their appropriate applications;●Globalization, including myriad opportunities and threats thatarise accordingly;●Sustainable differential advantage, or more precisely, sourcesand sustenance—e.g., branding and brand-equity—in an increasingly competitive and dynamic worldof agribusiness.We examine here the underlying forces that have invoked the shift from farm to market, and offer an updated definition for agribusiness. Further, we propose models that capture the essence of this transformation.2.2 What Has Changed?The center of agribusiness during much of the 20th century was the family farm and all immediately relevant supply inputs, production, processing, and distribution. Typical agribusiness firms provided a single input such as tractors or fertilizers, or processed one commodity such as milk, grain, vegetables, or fruits. In contrast, the 21st century experience incorporates a dynamic,systemic, stake-holder focus, with multiple and integrated inputs—particularly in the tasks of production, processing, distribution, and marketing communications. New demands such as rapid product innovation, leveraging scale-economies, driving revenue growth, capturing market share, adding sufficient value, co-marketing with competitors, and sensitivity to environmental impacts have become dominant managerial concerns.Trends suggest dominant 21st century agribusinesses tend to be characterized as: Larger. Many farms and firms have aggregated horizontally by adding substantially more acreage or more similar products to achieve economies of scale. Diversified. Often conglomerates that evolved from acquisition rather than internal growth have a portfolio of firms which may include food, fiber, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, and even energy. Complex:New requirements for accounting, financial reporting, and marketing relationships increase the complexity of agribusiness firms. Strategic:Long-term thinking about scarce resources such as soil, air, water,power, timber, petroleum, minerals, and fishes, as well as the number of variables that can affect them, have pushed many firms to manage carefully natural resources, often in ways that make resource sustainability a competitive advantage. Political:Political pressures manifest in zoning, safety, quality,ecology, access to water and power, and conservation are motivating many agribusiness firms to become politically active. Multinational. Grains, dairy products, meat; processed foods and fibers; and pharmaceuticals are exported worldwide.2.3 Pushing Agribusiness BoundariesThese changes create new challenges and thus opportunities or threats, depending upon one’s perspective and vested interests. In short, the boundaries of agribusiness are being pushed, particularly from the people, concepts, and institutions discussed elow.Agribusiness boundary expansion is driven in an economic sense by a variety of pressures, including social costs and transaction costs. Ronald Coase (1960) explained that people or firms bear both private costs (to themselves) and external costs (to society). These costs sum to the social cost of any action. Coase, and later Williamson (1996), showed how transaction costs push firms to innovate and change due to the increased costs of resources used for the creation of products and services.Transaction costs include defining and measuring resources or claims, the costs of using and enforcing rights, and the costs of information, negotiation, and enforcement (Williamson, 1996). As resources become increasingly scarce, both social and transaction costs goup, forcing organizations to change the way they act. Hence, the margins of agribusinesses move beyond traditional boundaries.3 Agribusiness strategy and business Opportunities3.1 Lower-Cost, Opposite Season, and New Competition AreasMany agribusinesses in developing economies have lower costs and compete successfully on price. Fruit and vegetable producers are experiencing significant new market entry from countries south of the equator that have an opposite growing season to North America. Most food stores now carry grapes, vegetables, and pit-fruits allwinter from Chile and other South American countries. New exotic foods and fibers, not grown currently in developed markets, are finding their way to supermarkets in the United States and Europe, and require more shelf space. These include new spices, sprouts, fruits, and seafoods. Soy and other plant-based meat substitutes similarly are entering the food market. New fertilizers, pesticides, and structural composites are likely to displace existing products, especially when they can be produced faster, cheaper, and use fewer natural resources than traditionalproducts use.3.2 Scientific Innovations and New Technologies and Methods Genetics, nutrition, production, health, and vitality all act to integrate science in agribusiness. Other issues also serve to merge agribusiness with science and technology, such as shelf-life, supply-chain management, ecological impacts, and perceived value. New technologies and methods such as bagged lettuce, boxed beef, flash-frozen seafood, and pre-prepared meals are results from scientific innovations that change agribusiness. Similarly, hydroponics, timber farms, genetically modified organisms , and other new production modes are challenging traditional production methods.3.3 Food Production and SecurityFood production increasingly is a science-based business, often controlled by large, multinational corporations. These huge agribusiness firms compete to sleuth the genetic secrets of plants and animals and to control their discoveries by acquiring patents for them . Further, agribusiness must redouble its efforts to address concerns about supply, security, and safety.3.4 HealthHealth issues tend to dominate many traditional agribusiness strategies. The creation of “no-fat fats,” seed hybrids, and genetic alterations integrate strong doses of medical information and testing. Issues such as pesticide residues, food contaminates, and water purity rank high in the public consciousness . The extent to which new foods enhance health and wellness ultimately will determine their success in the vitality market segment.3.5 Morphing Enterprises and Business ExtensionsTraditional chemical firms such as DuPont have created agribusiness divisions to build markets for their technical innovations . Classic agribusiness firms such as Monsanto continue to term the firm “agribusiness,” while their business models evolve to new forms of enterprise where they acquire and co-market with pharmaceutical firms, and develop entirely new product categories such as nutriceuticals . Forest product companies suchas Boise Cascade and Weyerhaeuser invest considerable resources in forest husbandry. Rubber companies grow renewable rubber trees and make extensive investments in glass and other materials to increase tire strength, longevity, and safety. Aquaculture has spawned new industries for fish and shellfish farming while managing serious constraints from ecological concerns .3.6 Traditional Distribution and RetailingLarger retailers, which also are morphing, have growing clout, affecting supplychain management, prices, production, branding, and marketing communication. In developing and transitioning economies , they are radically reshaping the agribusiness landscape, as farmers now engage in contract production with the strategy of more coordinated and efficient distribution. The net result is the demise of some traditional markets, but enhanced efficiency, choice, quality, and safety. Smaller, niche retailers also affect these variables, though clearly not so substantively. Boutique sellers frequently target opinion-leading consumers, and therefore often predict market trends. has made an industry around targeting opinion leaders by what they read and buy.Niche retailers are often able to sell higher margin products and services and to engage in higher margin activities.3.7 Government Regulation and Financial ServicesDespite a shift away from government intervention, in many respects governments still greatly affect agribusiness and expand boundaries by legislating standards, advocating for businesses and consumers, and largely stimulate a commercial landscape that enables agribusiness to administer its many value chains, to the benefit of the majority of stakeholders in those chains.Many agribusinesses have evolved into predominantly service versus product providers. Producers, processors, transporters, shippers, grocers, restaurants, insurance companies, and banks have a profound impact on the extent .Firms understand that consumers are highly influenced by the subtle cues . Consequently, the typical feedback card at a restaurant often asks more questions about the service and service-scape surroundings than the quality of food. Failing risk protection and financing, germane to unique challenges inherent to agribusinesmodels (e.g., perishability, ecology, and consumer safety), most agribusinesses would not survive.3.8 Electronic Media and the InternetSatellites, cable, fiber-optics, and the Internet now virtually work toward assuring at an accelerating rate—that every agribusiness and its stakeholders are inter-connected. Google andYahoo Web search engines commonly cross-reference key terms andcategories. Agribusiness becomes connected through search engines with ecology, pollution controls, water resources, and extractive industries. The Internet also expands the reach of agribusiness and intrinsically is another medium.Agribusinesses of any size can communicate with customers in the most remote regions of the world. Micro-marketers from remote regions in developing markets now can communicate with customers, distributors, and other members of value chains, thereby enabling distant channel members to sell to markets never before imagined. An overarching theme: explore new markets, ideas, products,and their growing interconnectedness are pushing the boundaries of agribusiness in ways never envisioned. International trade, finance, management and the latest information technologies, scientific discoveries, and marketing tools to maximize the value chain for products and services . 3.9 Evolving Product Concepts: Pharmaceuticals, Agriceuticals, and FibersMany of the aforementioned topics elicit changes to product concepts traditionally produced by natural and artificial substances. Some medicines, such as insulin, soon will be extracted from genetically modified plants; new strains of rice will include vitamin A and probably other nutrients; some expensive medicines will become available at low prices when they are extracted fromthe milk of cows or other mammals. On going revelations suggest that many new medicines will emerge from discoveries in the rainforests and the oceans, largely untapped and promising reservoirs of natural flora and fauna which can be parlayed into health benefits.These trends suggest an expansion of the pharmaceuticals industry to include the term “agriceuticals.” Fibers similarly have been a straight forward category of natural and artificial components. Now micro and nanno fibers are changing the category and extending into new areas, as are new product forms that combine natural and synthetic fibers. For example, the leading medical product to treat burns on human skin for decades has been thinly sliced skin from specially raised pigs. Now it is GORE-TEX , a product most observers equate with athletic gear. Wood fibers are being aligned to make products lighter and stronger, in some cases lighter and stronger than steel. Combinations of wood fibers and concrete arebeing fused into single pieces to make composites for creating strong, resilient, cost-effective housing materials.3.10 Recreation and TourismMany traditional agribusiness properties are evolving into the arenas of recreation,ecological learning, and tourism. Even familyfarms, where agribusiness has its genesis, have transformed their production from wheat and corn to golf courses, bird sanctuaries, or windmills. Near most cities, there are farms that lure busloads of students to explore pumpkin fields, milk cows, pet goats, or peaches. Similarly,many forests are now managed in ways that enable preservation, recreation, reforestation, biodiversity, and ecological learning in addition to timber production.3.11 Market-Centered AgribusinessThe preceding challenges, people, concepts, and institutions operate together to expand and to shift the discipline of agribusiness from the traditional farm-centered focus to customer centered. Market-centric agribusiness follows this path:and medicines—to name but a few agribusinesses. Unfortunately, not all agribusiness firms favor “green” practices or efforts to enhance resource sustainability—and one certainly could argue that an agribusiness firm can be profitable by being insensitive to such practices—but failure to embrace a systemic approach, failure to integrate natural resources management hints at a catastrophic threat to agribusiness firms.Therefore, natural resources including, for example, managed and non-managed stocks of fish and forests as well as renewable energy sources such as hydro, fuel cell, solar, wave, tide, and wind。