孔金阳

- 格式:doc

- 大小:114.00 KB

- 文档页数:15

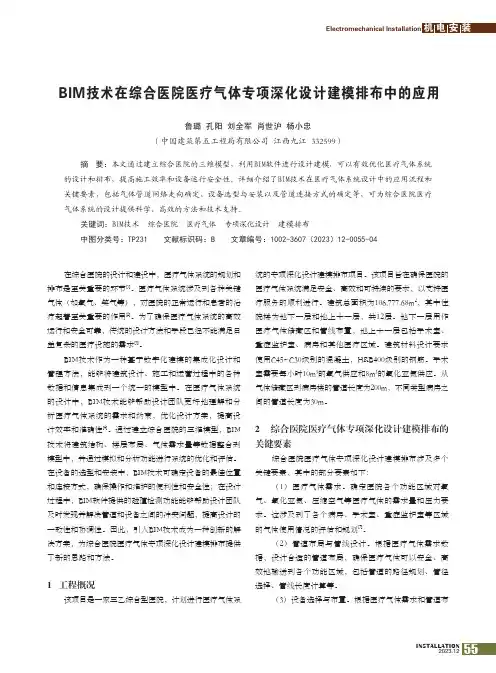

鲁璐 孔阳 刘全军 肖世沪 杨小忠(中国建筑第五工程局有限公司 江西九江 332599)摘要:本文通过建立综合医院的三维模型,利用BIM软件进行设计建模,可以有效优化医疗气体系统的设计和排布,提高施工效率和设备运行安全性。

详细介绍了BIM技术在医疗气体系统设计中的应用流程和关键要素,包括气体管道网络走向确定、设备选型与安装以及管道连接方式的确定等,可为综合医院医疗气体系统的设计提供科学、高效的方法和技术支持。

关键词:BIM技术 综合医院 医疗气体 专项深化设计 建模排布中图分类号:TP231 文献标识码:B 文章编号:1002-3607(2023)12-0055-04BIM技术在综合医院医疗气体专项深化设计建模排布中的应用在综合医院的设计和建设中,医疗气体系统的规划和排布是至关重要的环节[1]。

医疗气体系统涉及到各种关键气体(如氧气、笑气等),对医院的正常运行和患者的治疗起着至关重要的作用[2]。

为了确保医疗气体系统的高效运行和安全可靠,传统的设计方法和手段已经不能满足日益复杂的医疗设施的需求[3]。

BIM技术作为一种基于数字化建模的集成化设计和管理方法,能够将建筑设计、施工和运营过程中的各种数据和信息集成到一个统一的模型中。

在医疗气体系统的设计中,BIM技术能够帮助设计团队更好地理解和分析医疗气体系统的需求和约束,优化设计方案,提高设计效率和准确性[4]。

通过建立综合医院的三维模型,BIM 技术将建筑结构、楼层布局、气体需求量等数据整合到模型中,并通过模拟和分析功能进行系统的优化和评估。

在设备的选型和安装中,BIM技术可确定设备的最佳位置和连接方式,确保操作和维护的便利性和安全性;在设计过程中,BIM软件提供的碰撞检测功能能够帮助设计团队及时发现并解决管道和设备之间的冲突问题,提高设计的一致性和协调性。

因此,引入BIM技术成为一种创新的解决方案,为综合医院医疗气体专项深化设计建模排布提供了新的思路和方法。

D I S A垂直射压铸造生产线的管理要点The document was finally revised on 2021DISA垂直射压铸造生产线的管理要点摘要:丹麦DISA 公司生产的DISA湿型砂垂直射压造型机具有性能可靠、精度高、表面质量好、错型值小、操作简单和生产效率高等优点,目前在造型机行业处于最高水平。

有人说DISA 造型机就象傻瓜相机一样操作简单;也有用印钞机来比喻DISA造型机。

但实际经验告诉我们上,如果没有好的管理,好的设备并不能发挥好的作用。

即使有了先进的造型机,也不一定能生产出合格的铸件。

铸造生产是一个连续的过程,而且铸造是一个影响因素很多的系统,如果这个系统中有一个环节出了问题,就很有可能出废品。

又因为DISA 公司造型机的生产效率很高,所以一旦开始出废品,产生废品的速度也是惊人的。

因此,我们应该用系统的观点来考虑问题。

本文从新产品的开发谈起,就有关DISA 垂直射压造型生产线运行中应该注意的问题谈一些粗浅的看法。

关键词:铸造 DISA垂直射压造型线生产管理?1.全面准确地理解客户的要求让顾客满意的前提是要准确理解顾客的要求。

顾客的要求包括对产品质量特性的要求(如机械性能、化学成分、金相组织、尺寸公差、表面质量、检测方法的规定等)、对产品交付方面的要求(产品的数量、交付期、交货目的地等)、对价格方面的要求(价格条件、付款方式、结算方式等)及违约责任等其他特殊要求。

顾客的要求应该以书面的形式来表达,避免以后与顾客发生争执。

2.新产品的开发在新产品的开发阶段,首先要明确输入的顾客信息并制定开发计划,其次对设计开发的不同阶段要进行评审和验证,直至样品被顾客接受。

制定控制计划、作业指导书是该阶段必须要做的事情。

3. 原料采购铸造行业原材料所占的成本大约在60-70 %,因此通过在原料采购中对所有的原材料均应招标采购,这样做可以比较明显的降低原材料的价格和采购成本,提高原材料的质量。

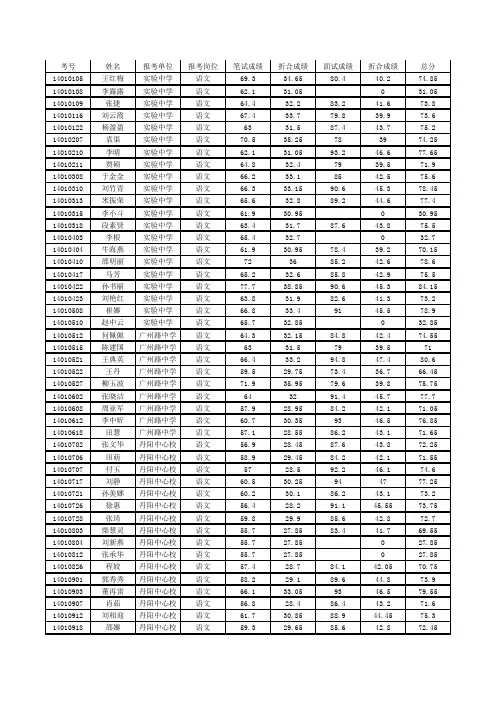

考号姓名报考单位报考岗位笔试成绩折合成绩面试成绩折合成绩总分14010105王红梅实验中学语文69.334.6580.440.274.85 14010108李露露实验中学语文62.131.05031.05 14010109张捷实验中学语文64.432.283.241.673.8 14010116刘云霞实验中学语文67.433.779.839.973.6 14010122杨盈盈实验中学语文6331.587.443.775.2 14010207袁渠实验中学语文70.535.25783974.25 14010210李晴实验中学语文62.131.0593.246.677.65 14010211贾硕实验中学语文64.832.47939.571.9 14010308于金金实验中学语文66.233.18542.575.6 14010310刘竹青实验中学语文66.333.1590.645.378.45 14010313米振荣实验中学语文65.632.889.244.677.4 14010315李小斗实验中学语文61.930.95030.95 14010318段素贤实验中学语文63.431.787.643.875.5 14010403李根实验中学语文65.432.7032.7 14010404牛海燕实验中学语文61.930.9578.439.270.15 14010410邵明丽实验中学语文723685.242.678.6 14010417马芳实验中学语文65.232.685.842.975.5 14010422孙书丽实验中学语文77.738.8590.645.384.15 14010423刘艳红实验中学语文63.831.982.641.373.2 14010508崔娜实验中学语文66.833.49145.578.9 14010510赵中云实验中学语文65.732.85032.85 14010512何佩佩广州路中学语文64.332.1584.842.474.55 14010515陈建国广州路中学语文6331.57939.571 14010521王典英广州路中学语文66.433.294.847.480.6 14010522王丹广州路中学语文59.529.7573.436.766.45 14010527柳玉波广州路中学语文71.935.9579.639.875.75 14010602张晓洁广州路中学语文643291.445.777.7 14010608周亚军广州路中学语文57.928.9584.242.171.05 14010612李中昕广州路中学语文60.730.359346.576.85 14010618田慧广州路中学语文57.128.5586.243.171.65 14010702张文华丹阳中心校语文56.928.4587.643.872.25 14010706田萌丹阳中心校语文58.929.4584.242.171.55 14010707付玉丹阳中心校语文5728.592.246.174.6 14010717刘静丹阳中心校语文60.530.25944777.25 14010721孙美娜丹阳中心校语文60.230.186.243.173.2 14010726徐惠丹阳中心校语文56.428.291.145.5573.75 14010728张琦丹阳中心校语文59.829.985.642.872.7 14010803柴慧灵丹阳中心校语文55.727.8583.441.769.55 14010804刘新燕丹阳中心校语文55.727.85027.85 14010812张承华丹阳中心校语文55.727.85027.85 14010826程姣丹阳中心校语文57.428.784.142.0570.75 14010901郭秀秀丹阳中心校语文58.229.189.644.873.9 14010903董再雷丹阳中心校语文66.133.059346.579.55 14010907肖茹丹阳中心校语文56.828.486.443.271.6 14010912刘相迎丹阳中心校语文61.730.8588.944.4575.3 14010918邵娜丹阳中心校语文59.329.6585.642.872.4514010919仝彩新丹阳中心校语文66.933.459145.578.95 14011004王丽娜丹阳中心校语文56.128.0585.242.670.65 14011007裴晓珍丹阳中心校语文57.828.983.241.670.5 14011008徐晓迪丹阳中心校语文55.627.891.545.7573.55 14011011王晓艳丹阳中心校语文67.433.78140.574.2 14011016兰静丹阳中心校语文61.230.687.643.874.4 14011028崔婧丹阳中心校语文57.928.9585.842.971.85 14011030刘蕾丹阳中心校语文55.727.8587.643.871.65 14011101纪宣宣丹阳中心校语文5728.5028.5 14011118张蝶丹阳中心校语文60.230.187.643.873.9 14011119张志慧丹阳中心校语文58.129.0589.644.873.85 14011125朱丹莉丹阳中心校语文61.330.6585.442.773.35 14011217李璇丹阳中心校语文57.528.75824169.75 14011221李炜丹阳中心校语文61.630.886.443.274 14011307冯雪丹阳中心校语文6532.590.245.177.6 14011322王改银丹阳中心校语文57.928.9581.240.669.55 14011325王紧紧丹阳中心校语文56.728.3576.438.266.55 14011404褚衍芳岳程中心校语文59.329.6580.440.269.85 14011405蒋欣岳程中心校语文63.231.683.241.673.2 14011410靳飞岳程中心校语文64.132.058944.576.55 14011429马薇薇岳程中心校语文59.129.5580.840.469.95 14011430孟迎岳程中心校语文73.236.6904581.6 14011501刘丹岳程中心校语文66.433.284.842.475.6 14011510刘萌岳程中心校语文62.731.35864374.35 14011511赵明岳程中心校语文73.736.8587.843.980.75 14011514梁雪翠岳程中心校语文5929.58140.570 14011516田海莉岳程中心校语文61.730.8587.243.674.45 14011601李秋平岳程中心校语文62.331.1586.843.474.55 14011604刘芳岳程中心校语文62.431.2031.2 14011607张佳宁岳程中心校语文72.936.4584.242.178.55 14011628丁卫上岳程中心校语文5929.588.444.273.7 14011630孙超岳程中心校语文59.229.684.242.171.7 14011705郭丽岳程中心校语文59.129.5583.241.671.15 14011710张锐雪岳程中心校语文62.231.188.444.275.3 14011714侯宁岳程中心校语文64.932.458743.575.95 14011729杨燕珍岳程中心校语文59.729.85029.85 14011802刘念岳程中心校语文67.433.787.843.977.6 14011827高晓玉岳程中心校语文61.530.75944777.75 14011910王海著岳程中心校语文59.629.8029.814011918卢海华岳程中心校语文(定向)67.833.988.244.17814011920孙燕岳程中心校语文(定向)41.320.65020.6514011924贾复叶佃户屯中心校语文603083.841.971.914012003吴玉文佃户屯中心校语文55.427.786.843.471.114012004刘忠伟佃户屯中心校语文62.531.25031.2514012013李菏梅佃户屯中心校语文63.831.985.242.674.514012019秦广磊佃户屯中心校语文54.827.471.835.963.314012023刘娜佃户屯中心校语文57.128.5594.847.475.9514012111张燕佃户屯中心校语文55.527.7577.438.766.4514012125李俊桃佃户屯中心校语文56.628.385.842.971.214012204李南佃户屯中心校语文6130.585.842.973.414012215苏亚佃户屯中心校语文57.228.687.643.872.414012216晁铭泽佃户屯中心校语文66.933.4583.241.675.0514012223朱金霞佃户屯中心校语文63.531.7578.439.270.9514012224黄凤丽佃户屯中心校语文6130.580.640.370.814012228李中瑞佃户屯中心校语文66.733.35824174.3514012305张金龙佃户屯中心校语文54.927.45027.4514012311韩冰丹阳路小学语文56.728.3586.643.371.65 14012316金兆燕丹阳路小学语文60.730.358944.574.85 14012317许小翠丹阳路小学语文58.429.293.446.775.9 14012325庞立伟丹阳路小学语文59.229.685.642.872.4 14012326杨瑞庆丹阳路小学语文65.132.558743.576.05 14012413苏仪丹阳路小学语文57.428.7028.7 14012418沙娜丹阳路小学语文59.629.890.645.375.1 14012501赵庆伟丹阳路小学语文58.729.3575.237.666.95 14012512张静丹阳路小学语文57.828.982.641.370.2 14012518陈冬亚丹阳路小学语文58.229.185.642.871.9 14012522夏慧丹阳路小学语文57.928.9590.245.174.05 14012529王含含丹阳路小学语文56.128.05804068.05 14012603李晓超丹阳路小学语文56.428.2028.2 14012605武洁丹阳路小学语文58.629.387.243.672.9 14012612徐双双丹阳路小学语文643291.845.977.9 14012621马崇喜丹阳路小学语文60.730.358743.573.85 14012622杨丹丹阳路小学语文57.528.7581.440.769.45 14012623徐丽丹阳路小学语文69.234.689.644.879.4 14020102庞艳芳实验中学数学7537.581.640.878.3 14020117郑贵霞实验中学数学63.231.684.442.273.8 14020120朱宇实验中学数学70.635.381.640.876.1 14020122刘勇实验中学数学73.236.6036.6 14020124洪慧丽实验中学数学78.839.489.844.984.3 14020128胡秀花实验中学数学7738.5804078.5 14020205李瑞鸽实验中学数学62.831.485.442.774.1 14020209王兆民实验中学数学68.634.382.641.375.6 14020211李萍实验中学数学6532.581.640.873.3 14020212李志红实验中学数学66.233.176.838.471.514020222丁爱荣实验中学数学7537.587.843.981.4 14020225姜蓓蓓实验中学数学61.430.772.636.367 14020229韩茹实验中学数学62.231.176.238.169.2 14020302张辉实验中学数学61.430.7030.7 14020313范丹丹实验中学数学62.631.382.841.472.7 14020316喻学民实验中学数学68.434.2034.2 14020323桑阳阳实验中学数学64.832.486.843.475.8 14020330赵芬实验中学数学65.432.782.241.173.8 14020424孙宝粉实验中学数学7336.589.444.781.2 14020427付秋娟实验中学数学64.432.290.845.477.6 14020429孔慧霞实验中学数学61.630.8030.814020501李春燕实验中学数学(定向)52.626.387.643.870.114020502单素兰实验中学数学(定向)442278.639.361.314020503贾倩倩广州路中学数学582979.839.968.9 14020504王威广州路中学数学64.632.390.445.277.5 14020511张明月广州路中学数学6130.575.237.668.1 14020521万海云广州路中学数学58.629.377.638.868.1 14020526张乐乐广州路中学数学62.631.379.239.670.9 14020527刘丽霞广州路中学数学56.828.4783967.4 14020601徐云路广州路中学数学57.828.986.443.272.1 14020603李冉广州路中学数学79.239.68944.584.1 14020604李振振广州路中学数学60.230.176.838.468.5 14020610胡素娟丹阳中心校数学542779.439.766.7 14020612王琳丹阳中心校数学57.628.8864371.8 14020614姜娜娜丹阳中心校数学65.232.678.439.271.8 14020615刘庆栋丹阳中心校数学52.626.394.647.373.6 14020623宋世宇丹阳中心校数学63.631.89547.579.3 14020711任亚萍丹阳中心校数学57.628.886.643.372.1 14020715于磊丹阳中心校数学64.232.179.839.972 14020720毛永婷丹阳中心校数学70.835.4904580.4 14020725刘杏莉丹阳中心校数学60.630.385.642.873.1 14020726王品丹阳中心校数学69.834.987.243.678.5 14020801刘星丹阳中心校数学5728.58140.569 14020803李霞丹阳中心校数学55.227.689.644.872.4 14020805马沛沛丹阳中心校数学5527.586.843.470.9 14020806吕海丽丹阳中心校数学60.630.382.841.471.7 14020810赵慧媛丹阳中心校数学62.231.183.641.872.9 14020812刘艳香丹阳中心校数学61.630.881.440.771.5 14020819任桂梅丹阳中心校数学52.426.287.843.970.1 14020820石海红丹阳中心校数学53.226.681.440.767.3 14020827吕继莲丹阳中心校数学6130.586.243.173.6 14020902王俊方丹阳中心校数学52.226.185.242.668.7 14020905翟春静丹阳中心校数学52.226.1026.1 14020906李文荟丹阳中心校数学70.635.392.846.481.7 14020911李雁丹阳中心校数学83.241.686.443.284.8 14020917段素永丹阳中心校数学54.427.285.242.669.814020928任桂房丹阳中心校数学54.627.371.235.662.9 14021001王延红丹阳中心校数学58.229.1029.1 14021003张丹玉丹阳中心校数学72.236.194.847.483.5 14021013陶翠风丹阳中心校数学53.626.88341.568.3 14021015张晶晶丹阳中心校数学58.829.483.841.971.3 14021016朱兆伟丹阳中心校数学51.825.9783964.9 14021020李娜丹阳中心校数学69.834.990.245.180 ********郭倩倩丹阳中心校数学55.827.99547.575.4 14021026马海燕丹阳中心校数学562893.446.774.7 14021028张然丹阳中心校数学55.227.688.444.271.8 14021107段蕊丹阳中心校数学70.235.184.442.277.3 14021113刘芳丹阳中心校数学57.628.886.643.372.1 14021115徐哲丹阳中心校数学57.428.788.644.373 14021116吴丹丹阳中心校数学65.632.893.646.879.6 14021124魏静岳程中心校数学60.830.481.840.971.3 14021201吴娜岳程中心校数学57.828.995.447.776.6 14021203贾玉华岳程中心校数学63.231.674.637.368.9 14021205刘爽岳程中心校数学51.225.681.440.766.3 14021206王红燕岳程中心校数学56.228.181.840.969 14021216高俊霞岳程中心校数学57.628.889.244.673.4 14021218马卫娜岳程中心校数学5125.5804065.5 14021224赵贵珍岳程中心校数学582989.844.973.9 14021229胡慧娟岳程中心校数学60.430.27135.565.7 14021307张雪梅岳程中心校数学51.825.9025.9 14021311于茜岳程中心校数学562882.641.369.3 14021312李艳红岳程中心校数学54.427.2844269.2 14021316薛峰岳程中心校数学6331.587.643.875.3 14021317王晓琳岳程中心校数学5125.580.440.265.7 14021323林宗立岳程中心校数学57.428.777.238.667.3 14021324顾桐岳程中心校数学562886.443.271.2 14021327王晓丹岳程中心校数学55.227.677.238.666.2 14021411赵瑞莹岳程中心校数学57.828.98944.573.4 14021415陈改丽岳程中心校数学72.636.3844278.3 14021420王萍萍岳程中心校数学60.630.372.236.166.4 14021421苌娟岳程中心校数学63.231.686.843.475 14021424王素英岳程中心校数学5125.569.634.860.3 14021508汪秀华岳程中心校数学582972.236.165.114021510刘春阳佃户屯中心校数学51.625.868.534.2560.0514021517常佳佃户屯中心校数学53.626.882.441.26814021523孙久卫佃户屯中心校数学603075.837.967.914021526苗婷婷佃户屯中心校数学52.226.174.837.463.514021529吴伟佃户屯中心校数学50.825.491.845.971.314021603何晓华佃户屯中心校数学54.827.489.644.872.214021606于文花佃户屯中心校数学53.626.87537.564.314021613李兴新佃户屯中心校数学522672.436.262.214021620马坤佃户屯中心校数学522662.231.157.114021623张世朋佃户屯中心校数学51.425.7904570.714021703王端强佃户屯中心校数学58.429.28743.572.714021706翟瑞玲佃户屯中心校数学51.825.989.844.970.814021709兰怀彪佃户屯中心校数学57.228.680.640.368.914021713赵慧佃户屯中心校数学57.628.8944775.814021716王福霆佃户屯中心校数学63.231.6603061.614021719常晓琳丹阳路小学数学53.226.682.641.367.9 14021720时蕊蕊丹阳路小学数学6130.582.241.171.6 14021803牛青燕丹阳路小学数学50.225.19346.571.6 14021806陈富永丹阳路小学数学48.424.281.440.764.9 14021809岳妍妍丹阳路小学数学46.223.1023.1 14021827郝厚莉丹阳路小学数学56.228.185.842.971 14021828张贵影丹阳路小学数学61.230.687.243.674.2 14021908刘双文丹阳路小学数学58.429.287.643.873 14021917岳远福丹阳路小学数学52.626.382.841.467.7 14021918于瑞娟丹阳路小学数学53.426.787.443.770.4 14021920汤曼曼丹阳路小学数学45.822.981.240.663.5 14021921吴盟盟丹阳路小学数学58.229.186.643.372.4 14021925徐琛丹阳路小学数学48.624.382.841.465.7 14021929王德博丹阳路小学数学48.824.460.830.454.8 14030102李静实验中学英语76.338.1588.844.482.55 14030106吴书蕾实验中学英语79.939.9588.444.284.15 14030107刘雯雯实验中学英语77.938.95884482.95 14030109田婷婷实验中学英语804085.842.982.9 14030116王瑞杰实验中学英语79.339.6586.643.382.95 14030122靳秋梅实验中学英语79.339.6590.245.184.75 14030128梁搏云实验中学英语78.239.188.644.383.4 14030211姚永燕实验中学英语79.639.887.843.983.7 14030311姬广梅实验中学英语76.438.276.638.376.5 14030330韩秋爽实验中学英语78.439.288.844.483.6 14030404薄彦娜实验中学英语77.338.6591.245.684.25 14030405季肖宾实验中学英语78.939.4590.245.184.55 14030423张惠然实验中学英语77.138.5591.845.984.45 14030430田如实验中学英语84.242.186.243.185.2 14030508张姿实验中学英语81.840.986.443.284.1 14030516马旺莉实验中学英语78.639.386.243.182.4 14030517刘佩佩实验中学英语783992.646.385.3 14030528郑璐璐实验中学英语77.738.858944.583.35 14030601姜文实验中学英语79.239.684.642.381.914030610郭艳芝实验中学英语76.838.489.244.683 14030614王唤实验中学英语81.340.6589.844.985.55 14030616崔晓萌实验中学英语76.138.0590.445.283.25 14030629宋艳玲广州路中学英语73.436.785.842.979.6 14030630梅风春广州路中学英语76.838.487.443.782.1 14030704何霏霏广州路中学英语72.336.1586.643.379.45 14030715朱玺诺广州路中学英语75.437.783.841.979.6 14030719李艳慧广州路中学英语76.438.288.844.482.6 14030720袁哲广州路中学英语72.936.4587.843.980.35 14030801刘永霞广州路中学英语7336.587.243.680.1 14030805吴寒广州路中学英语80.540.2590.845.485.65 14030825时丽静丹阳中心校英语66.633.387.243.676.9 14030901张红梅丹阳中心校英语70.435.286.243.178.3 14030912宋倩倩丹阳中心校英语71.335.6584.842.478.05 14030924黄路路丹阳中心校英语73.336.6590.245.181.75 14030926孙玉洁丹阳中心校英语69.634.8884478.8 14030930郭东丹阳中心校英语76.138.0588.844.482.45 14031001马瑞娟丹阳中心校英语70.335.1591.845.981.05 14031003郭青红丹阳中心校英语7537.58743.581 14031009王燕敏丹阳中心校英语67.533.7584.842.476.15 14031012李培培丹阳中心校英语70.235.189.644.879.9 14031018石星丹阳中心校英语743790.445.282.2 14031022杨知芹丹阳中心校英语75.337.6584.442.279.85 14031028郑妍妍丹阳中心校英语72.836.490.845.481.8 14031107周玉芬丹阳中心校英语66.233.18743.576.6 14031108尹培梅丹阳中心校英语6834884478 14031116刘江慧丹阳中心校英语6934.582.641.375.8 14031117申江虹丹阳中心校英语69.234.689.644.879.4 14031120王雨丹阳中心校英语72.336.15036.15 14031121张珊珊丹阳中心校英语68.334.1589.244.678.75 14031219董红彬丹阳中心校英语74.237.189.244.681.7 14031222于燕丹阳中心校英语73.936.958743.580.45 14031303王艳岳程中心校英语68.334.15804074.15 14031310孙艳丽岳程中心校英语71.835.9035.9 14031317刘艳岳程中心校英语68.434.283.841.976.1 14031326李瑞芳岳程中心校英语75.937.9590.645.383.25 14031330王萌岳程中心校英语69.834.981.840.975.8 14031404王秋菊岳程中心校英语72.536.2580.640.376.55 14031407邓敏岳程中心校英语69.634.889.244.679.4 14031422宋珍岳程中心校英语74.737.3584.642.379.65 14031429秦丽岳程中心校英语70.435.278.439.274.414031505陈国苹佃户屯中心校英语62.431.287.643.87514031511高丽佃户屯中心校英语6130.590.445.275.714031520周敏敏佃户屯中心校英语6130.584.642.372.814040102刘林林实验中学物理61.830.990.7145.3676.2614040107霍庆松实验中学物理683483.2941.6575.65 14040113乔朋亚实验中学物理65.832.980.7140.3673.26 14040114信建朋实验中学物理59.229.682.1441.0770.67 14040118白易灵实验中学物理68.634.390.2945.1579.45 14040122何娟实验中学物理59.829.982.1441.0770.97 14040127张顺实验中学物理623181.4340.7271.72 14040129王苹实验中学物理61.830.984.5742.2973.19 14040205杨立斌实验中学物理60.630.381.1440.5770.87 14050104杨佩实验中学化学77.238.60038.6 14050116刘秀芬实验中学化学70.635.391.5745.7981.09 14050207高速实验中学化学7135.587.5743.7979.29 14050212刘秀英实验中学化学73.836.984.7142.3679.26 14050225魏玲实验中学化学73.636.883.1441.5778.37 14050226张新实验中学化学72.236.183.2941.6577.75 14050227李红梅实验中学化学71.235.689.8644.9380.53 14050301李洪囡实验中学化学7939.581.5740.7980.29 14060105闫松松实验中学生物61.530.7588.4344.2274.97 14060117孟红霞实验中学生物58.729.3586.2943.1572.5 14060119李霞实验中学生物59.629.879.5739.7969.59 14060125姚国宇实验中学生物60.930.4575.4337.7268.17 14060126贺洁实验中学生物58.729.3594.2947.1576.5 14060127丁丽津实验中学生物62.831.489.8644.9376.33 14060128徐娟实验中学生物58.829.489.2944.6574.05 14060201王晓晶实验中学生物60.130.0587.5743.7973.84 14060211吴琳实验中学生物623181.5740.7971.79 14060226刘园丽实验中学生物66.833.485.1442.5775.97 14060227张莹莹实验中学生物60.930.4586.1443.0773.52 14060311李晓华实验中学生物64.532.2584.4342.2274.47 14070104彭珊珊实验中学政治70.635.389.2944.6579.95 14070109刘龙涛实验中学政治69.834.988.1444.0778.97 14070117武少龙实验中学政治69.434.787.8643.9378.63 14070130陈静实验中学政治70.435.290.1445.0780.27 14070210尹倩实验中学政治723692.4346.2282.22 14070212张连美实验中学政治74.637.387.7143.8681.16 14070221黄雪梅实验中学政治69.634.883.8641.9376.73 14070222王红彩实验中学政治72.236.191.4345.7281.82 14070223刘洪军广州路中学政治70.235.181.2940.6575.75 14070227王文静广州路中学政治71.635.890.7145.3681.16 14070302于金凯广州路中学政治73.636.88944.581.3 14080106王创创实验中学历史67.633.8033.8 14080107孙超实验中学历史763884.7142.3680.36 14080108姜琰实验中学历史64.432.287.4343.7275.92 14080119李忠国实验中学历史72.236.183.7141.8677.96 14080121胡玉静实验中学历史6532.586.1443.0775.57 14080129吴桂真实验中学历史723685.5742.7978.79 14080206李翠平佃户屯中学历史75.437.789.1444.5782.27 14080214李悦佃户屯中学历史76.638.390.8645.4383.7314080215李玉鹏佃户屯中学历史7035035 14090104刘庆凤实验中学地理5728.586.1443.0771.57 14090106杨延东实验中学地理60.630.384.5742.2972.59 14090108褚福玲实验中学地理56288140.568.5 14090111姜旭实验中学地理56.228.188.2944.1572.25 14090113段凤杰实验中学地理56.828.483.2941.6570.05 14090115刘霄实验中学地理58.829.481.4340.7270.12 14090117杨海燕实验中学地理643289.1444.5776.57 14090119杲东超实验中学地理55.827.985.2942.6570.55 14090120孙建雷实验中学地理66.433.289.1444.5777.77 14090123杨巧宁实验中学地理6532.587.2943.6576.15 14090202石其鹏实验中学地理58.429.283.1441.5770.77 14090203张静实验中学地理58.229.190.1445.0774.17 14090206李雪实验中学地理57.228.682.5741.2969.89 14090209邵明晓实验中学地理623185.7142.8673.86 14090210胡莉莉实验中学地理62.431.28542.573.7 14090219李红广州路中学地理58.429.285.2942.6571.85 14090221王燕爽广州路中学地理61.430.784.1442.0772.77 14090223李鸿飞广州路中学地理58.229.1029.1 14100103王乃号实验中学体育683484.242.176.1 14100107秦琦实验中学体育703590.245.180.1 14100113贾勇实验中学体育65.632.885.742.8575.65 14100120彭相超实验中学体育66.433.285.442.775.9 14100129李斌实验中学体育65.632.888.244.176.9 14100202王杰实验中学体育68.234.187.543.7577.85 14100203赫海峰实验中学体育6733.590.645.378.8 14100204董翔实验中学体育74.637.389.144.5581.85 14100206吕翠翠实验中学体育68.234.1884478.1 14100221李新坤实验中学体育65.632.893.646.879.6 14100224王付银实验中学体育65.832.987.843.976.8 14100226王飞龙实验中学体育68.434.285.142.5576.75 14100229苏通实验中学体育73.636.892.646.383.1 14100230代倩实验中学体育77.638.888.944.4583.25 14100308孙士帅实验中学体育70.635.389.444.780 14100310孟令渊实验中学体育6733.578.439.272.7 14100311乔征萍丹阳中心校体育70.235.190.445.280.3 14100313侯增鹏丹阳中心校体育68.834.489.844.979.3 14100317盛开俊丹阳中心校体育66.633.391.845.979.2 14100319辛山溟丹阳中心校体育663385.242.675.6 14100330张慧丹阳中心校体育72.836.490.445.281.6 14100406孙雪冰丹阳中心校体育71.635.889.644.880.6 14100417王伟岳程中心校体育79.639.884.642.382.1 14100419王银婷岳程中心校体育62.631.3031.3 14100421王彬岳程中心校体育77.238.689.344.6583.25 14100423商长辉岳程中心校体育64.432.280.640.372.5 14100425倪翠翠岳程中心校体育62.231.188.144.0575.15 14100426杨亚南岳程中心校体育63.631.886.243.174.914100504董红梅佃户屯中心校体育59.429.782.341.1570.8514100505蒋艳茹佃户屯中心校体育77.438.7904583.714100508张震佃户屯中心校体育59.829.978.439.269.114100509胡文飞佃户屯中心校体育57.228.679.939.9568.5514100515刘士辉佃户屯中心校体育66.233.1033.114100516麻忠宁佃户屯中心校体育71.435.790.845.481.114100524崔丽娟丹阳路小学体育54.427.286.843.470.6 14100526郭兴芸丹阳路小学体育63.231.68944.576.1 14100528尹茂民丹阳路小学体育61.230.689.144.5575.15 14110113刘慧静广州路中学音乐6231844273 14110117杨亚慧广州路中学音乐61.430.784.642.373 14110119吕春燕广州路中学音乐59.429.789.444.774.4 14110127艾清柯丹阳中心校音乐56.428.28542.570.7 14110130苗影丹阳中心校音乐54.427.291.645.873 14110202刘小慈丹阳中心校音乐66.633.389.444.778 14110204李妮臻丹阳中心校音乐6331.586.443.274.7 14110213宋延延丹阳中心校音乐59.629.889.244.674.4 14110228李敏纳丹阳中心校音乐53.626.878.439.266 14110230姜曼丹阳中心校音乐5728.591.645.874.3 14110301董燕丹阳中心校音乐53.626.882.241.167.9 14110303范书锋岳程中心校音乐59.229.684.442.271.8 14110307丁景宽岳程中心校音乐582989.444.773.7 14110308祝莹慧岳程中心校音乐5929.587.243.673.1 14110312李倩岳程中心校音乐63.831.989.844.976.8 14110319孔莹莹岳程中心校音乐5929.591.245.675.1 14110327许松岳程中心校音乐71.635.886.243.178.914110423杨德龙佃户屯中心校音乐5728.5904573.514110424李慧敏佃户屯中心校音乐55.227.690.845.47314110428高艳佃户屯中心校音乐61.630.8884474.814110502郭亚奇佃户屯中心校音乐603092.246.176.114110506权薇佃户屯中心校音乐55.827.988.844.472.314110513张莹佃户屯中心校音乐64.232.194.647.379.414110516李哲颖佃户屯中心校音乐5929.591.645.875.314110517曹政伟佃户屯中心校音乐55.427.790.445.272.914110523陈红基佃户屯中心校音乐562886.643.371.314110530田亚娜佃户屯中心校音乐63.831.992.446.278.114110610张丽娟佃户屯中心校音乐58.829.49346.575.914110619赵瑞汝佃户屯中心校音乐61.830.98542.573.414110620郭姗佃户屯中心校音乐59.429.788.844.474.114110624周志伟佃户屯中心校音乐56.228.188.444.272.314110711苏爱娜丹阳路小学音乐67.433.790.845.479.1 14110713崔丹丹丹阳路小学音乐59.629.888.644.374.1 14110717张洁丹阳路小学音乐61.430.7944777.7 14120117刘丽梨实验中学美术71.635.892.446.282 14120121宋红艳实验中学美术683475.437.771.7 14120124胡树媛实验中学美术75.237.683.241.679.2 14120213费红光佃户屯中学美术68.634.3824175.3 14120225孙欣佃户屯中学美术69.434.791.445.780.4 14120229施永平佃户屯中学美术63.831.98542.574.4 14120310张静岳程中心校美术72.436.288.444.280.4 14120319尹璐岳程中心校美术69.634.891.645.880.6 14120321郭丽敏岳程中心校美术69.834.986.843.478.3 14120324赵彩芹岳程中心校美术68.234.188.444.278.3 14120419王会娟岳程中心校美术7135.587.243.679.1 14120423袁振梅岳程中心校美术76.238.190.245.183.2 14120425王素叻岳程中心校美术68.834.485.642.877.2 14120426王凤霞岳程中心校美术73.436.78944.581.2 14120502魏春青岳程中心校美术74.437.290.645.382.5 14120506孙晓玲岳程中心校美术70.435.287.843.979.1 14120517仪冬平岳程中心校美术70.835.48743.578.9 14120521翟卫国岳程中心校美术68.634.389.244.678.914120602张立敏佃户屯中心校美术7336.58743.58014120604王星佃户屯中心校美术69.234.690.645.379.914120605石娜娜佃户屯中心校美术683484.842.476.414120608韩珊珊佃户屯中心校美术68.434.28944.578.714120620王巧佃户屯中心校美术68.434.286.843.477.614120621王欣然佃户屯中心校美术66.833.490.845.478.814120627朱鲁雪佃户屯中心校美术74.437.288.244.181.314120628郭琳琳佃户屯中心校美术73.836.987.443.780.614120723李宝娟佃户屯中心校美术70.835.484.442.277.614120724司雪艳佃户屯中心校美术68.234.188.844.478.514120807张莉芝佃户屯中心校美术743793.646.883.814120811邹国娜佃户屯中心校美术68.234.188.644.378.414120813路慧萍佃户屯中心校美术703589.444.779.714120826晋慧娟佃户屯中心校美术68.634.390.845.479.714120906王红佃户屯中心校美术72.436.288.444.280.414120918祝稳稳丹阳路小学美术72369145.581.5 14120924赵姝丹阳路小学美术70.435.289.644.880 14120929王萌丹阳路小学美术74.837.48944.581.9 14130104郭培芳实验中学计算机6130.5824171.5 14130113徐新博实验中学计算机68.834.489.4344.7279.12 14130120赵效林实验中学计算机6130.577.2938.6569.15 14130124周君倩实验中学计算机63.231.685.2942.6574.25 14130125李兰廷实验中学计算机643289.4344.7276.72 14130205李娜实验中学计算机62.831.479.5739.7971.19 14130208范彦静佃户屯中学计算机60.230.182.7141.3671.46 14130211吴卫佃户屯中学计算机5326.593.7146.8673.36 14130212刘康亚佃户屯中学计算机49.424.776.7138.3663.0614130214吴林华佃户屯中心校计算机60.830.486.7143.3673.7614130216安凤佃户屯中心校计算机44.822.481.8640.9363.3314130218庞肖玉佃户屯中心校计算机4924.572.5736.2960.7914130220范文敏佃户屯中心校计算机44.822.463.8631.9354.3314140102王艳美丹阳中心校学前教育66.633.388.444.277.5 14140107李瑞雪丹阳中心校学前教育6331.576.838.469.9 14140114陈慧杰丹阳中心校学前教育70.435.282.441.276.4 14140125王飞飞丹阳中心校学前教育67.833.985.242.676.5 14140126刘红岩丹阳中心校学前教育643290.445.277.2 14140127王荣倍丹阳中心校学前教育63.631.879.639.871.6 14140211于雨岳程中心校学前教育64.232.183.841.974 14140220陈娟岳程中心校学前教育65.632.879.439.772.5 14140224闫妍岳程中心校学前教育66.833.486.643.376.7 14140225卢福丽岳程中心校学前教育60.430.286.443.273.4 14140302孟姣岳程中心校学前教育6532.577.838.971.4 14140313薛姗岳程中心校学前教育63.431.7031.714140315宋洪兰佃户屯中心校学前教育57.828.989.844.973.814140318陈丹丹佃户屯中心校学前教育5728.5783967.514140325程蕴博佃户屯中心校学前教育623187.443.774.714140405石丹丹佃户屯中心校学前教育57.628.887.843.972.714140406王亭佃户屯中心校学前教育60.230.180.840.470.514140408王莹佃户屯中心校学前教育69.434.779.639.874.514140413赵珂佃户屯中心校学前教育60308341.571.514140415晁品品佃户屯中心校学前教育64.632.383.841.974.214140423张明冉佃户屯中心校学前教育64.832.48542.574.914140429彭慧珍实验幼儿园学前教育65.232.682.241.173.7 14140508刘佳实验幼儿园学前教育69.634.887.643.878.6 14140516解红峰实验幼儿园学前教育6633864376 14140517李桂珍实验幼儿园学前教育69.234.679.639.874.4 14140522孟令超实验幼儿园学前教育65.432.788.444.276.9 14140529董昱汝实验幼儿园学前教育65.232.683.841.974.5 14140611吴春婷实验幼儿园学前教育703575.437.772.7 14140616李姝婧实验幼儿园学前教育67.433.791.445.779.4 14140707魏敏实验幼儿园学前教育63.431.7031.7。

孔姓名字大全_孔姓男孩名字_孔姓女孩名字孔姓男孩名字大全:孔云峰孔晓方孔宏孔卓然孔战民孔丽晴孔源源孔剑雄孔雨然孔茗辉孔熙宇孔海良孔春孔杰瑞孔九凤孔顺林孔睿孔国旺孔沐淋孔德强孔承明孔高亮孔砚孔心琪孔子卓孔锦诚孔真帅孔博可孔万禄孔祖光孔涛孔霆孔滑孔韧孔斯然孔炫似孔弘绫孔延孔俊威孔嘉姗孔郁耀孔纯磊孔承影孔浆孔宗含孔骥孔玄凯孔敏祺孔林枫孔长旦孔禹露孔文滔孔力横孔语嘉孔志浩孔彦弛孔安沁孔艺宁孔舒扬孔锋孔涵迪孔浈辉孔晓晨孔子千孔占波孔浩海孔光华孔九斤孔穆容孔依蕾孔亚楠孔俞航孔艳敏孔豫孔汶刖孔晓雅孔缦芸孔智生孔东满孔思靖孔欣铧孔长春孔丁郁孔玉兰孔赢政孔无双孔旷代孔推霍孔晨孔顺砉孔屹欣孔以寒孔建赫孔孟生孔魏韵孔龙河孔彦彬孔闰泽孔国津孔一孔仪倚孔洲荥孔焱海孔鑫浩孔奕超孔煜中孔欣生孔煜涛孔铭玮孔艺霏孔伟伟孔舜天孔灵晴孔晶孔世恿孔章少孔弋凡孔恒熙孔荀孔勋君孔淞孔详明孔闻郡孔永清孔宗沛孔若萌孔彬峰孔昭君孔趁孔璧徽孔冬生孔钰博孔久明孔荣权孔建勋孔留那孔永东孔夕裕孔金轩孔湃泛孔习习孔锦裕孔邦进孔文杰孔天昌孔庄禹孔亦贝孔卧南孔国华孔文潞孔思清孔志辉孔熙湘孔果孔浩燃孔宇体孔向伟孔耀辉孔锦辉孔渲溢孔泽含孔仁孔意捷孔瑜晋孔耀来孔辰含孔薰仪孔歆孔看孔圣钧孔瑜涵孔昕宇孔钿深孔海顶孔子淦孔泰宸孔梦笔孔以善孔品邺孔粉隆孔玉军孔仪华孔镱洲孔晟民孔洋孔茉孔蕊孔美涵孔艺菡孔禾孔焕春孔龟孔晓庆孔宸甘孔景松孔诺尧孔天民孔兵孔雨筠孔翔孔睿民孔度寒孔军孔宥孔穆仟孔一岩孔小播孔素杰孔岳蓓孔科晖孔诗晗孔浩翔孔旷崛孔永新孔秀光孔正辉孔佳孔宝谣孔剑峰孔黎军孔子海孔三多孔娴孔雨宸孔宝灯孔圣伟孔著易孔饴养孔会瑜孔沫菡孔亚孔志璞孔苏齐孔承序孔希月孔姓女孩名字大全:孔祥婵孔丌娜孔倩容孔颖茹孔琳惠孔蓉易孔蓉儿孔宝怡孔志玲孔振玉孔墨琳孔仪婷孔凡艳孔美娜孔圆红孔燕婉孔悦篮孔奕茹孔莲萍孔笑萍孔俊美孔茗秀孔钰霞孔丰英孔滢雪孔光红孔令瑛孔琼琼孔兰芳孔六英孔玲嫒孔秋娜孔妍巧孔雪婷孔可玉孔佳雪孔丽茹孔瑞玉孔瑞婷孔怡萱孔妍仟孔钰琳孔敏英孔涵怡孔永梅孔香茹孔姝瑶孔如玉孔依妍孔伟英孔林秀孔鑫怡孔凯文孔帼芬孔燕飞孔君怡孔抒琴孔舒琴孔束琴孔菽琴孔燕仪孔帼芳孔帼红孔艺婷孔惠燕孔莘冉孔晨瑶孔涵瑶孔百霞孔红红孔广玉孔月霞孔汇文孔碧悦孔曼莉孔帅文孔悦希孔慧颖孔娜妮孔宜怡孔淼玉孔淼怡孔鸶怡孔释怡孔斯怡孔紫媛孔梓媛孔梓怡孔施怡孔祖悦孔沐婷孔乐颖孔玉瑶孔秀巧孔童玉孔景怡孔钰玲孔钰洁孔荷玉孔家玉孔嘉玉孔婷玉孔扬文孔紫倩孔文梅孔淑花孔希媛孔郭美孔小倩孔怡林孔怡琳孔虹洁孔蔓玉孔小莉孔蓉荣孔飞英孔军燕孔玲凤孔丛霞孔聪霞孔银燕孔童瑶孔彤瑶孔维莹孔文燕孔颜婷孔争艳孔怡茜孔小怡孔玮婷孔娴婷孔紫颖孔婷蕊孔琳茗孔兆艳孔凤玲孔晗琼孔昭文孔德莉孔怡妹孔雅红孔宏霞孔品瑶孔品玉孔美琼孔品妍孔品冉孔品媛孔颦丽孔品丽孔晴雪孔兮媛孔以琳孔真玉孔贞玉孔珍玉孔凯悦孔泽玉孔垂茹孔茹瑶孔绍文孔悦名孔严婷孔海艳孔红芬孔得洁孔德洁孔术玲孔玲莉孔紫瑶孔倩雅孔雨琳孔语琳孔迎雪孔垂莹孔金梅孔玲澜孔玲岚孔香红孔妍又孔谷英孔紫文孔雅芳孔雅莉孔方怡孔晓美孔杰冉孔米玲孔唯玲孔改玲孔希茹孔雨茹孔冰琳孔素媛孔力冉孔燕楠孔萃丽孔应文孔伟娜孔樱蓉。

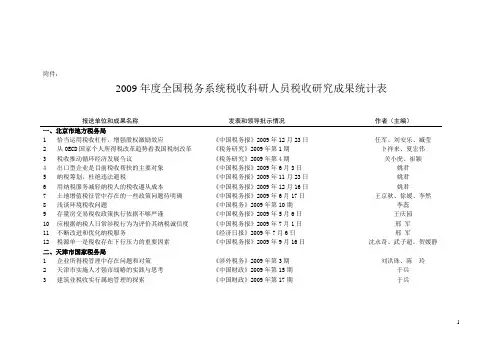

附件:2009年度全国税务系统税收科研人员税收研究成果统计表报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)一、北京市地方税务局1 恰当运用税收杠杆,增强股权激励效应《中国税务报》2009年12月23日任军、刘安乐、臧莹2 从OECD国家个人所得税改革趋势看我国税制改革《税务研究》2009年第1期卜祥来、夏宏伟3 税收推动循环经济发展刍议《税务研究》2009年第4期关小虎、崔颖4 出口型企业是目前税收帮扶的主要对象《中国税务报》2009年6月3日姚君5 纳税筹划,杜绝违法避税《中国税务报》2009年11月23日姚君6 用纳税服务减轻纳税人的税收遵从成本《中国税务报》2009年12月16日姚君7 土地增值税征管中存在的一些政策问题待明确《中国税务报》2009年6月17日王京秋、徐媛、李然8 浅谈环境税收问题《中国税务》2009年第10期李蕊9 存量房交易税收政策执行依据不够严谨《中国税务报》2009年5月6日王庆园10 应根据纳税人日常涉税行为为评价其纳税诚信度《中国税务报》2009年7月1日邢军11 不断改进和优化纳税服务《经济日报》2009年7月6日邢军12 税源单一是税收存在下行压力的重要因素《中国税务报》2009年9月16日沈永奇、武子超、贺媛静二、天津市国家税务局1 企业所得税管理中存在问题和对策《涉外税务》2009年第3期刘洪珠、陈玲2 天津市实施人才强市战略的实践与思考《中国财政》2009年第15期于兵3 建筑业税收实行属地管理的探索《中国财政》2009年第17期于兵1报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)三、河北省地方税务局1 2008年河北省地税系统优秀调研成果河北大学出版社 2009年8月税收研究中心2 大任斯人——中国税史人物评传中国税务出版社 2009年11月李胜良四、山西省地方税务局1 新理念、新跨越、新发展中国税务出版社 2009年8月卢晓中2 煤碳开采行业税收政策研究《税务研究》2009年第7期马爱锋、王久瑾、王婧五、内蒙古自治区国家税务局1 研究与探索(2006--2008论文集) 中国税务出版社2009年6月李青山六、辽宁省大连市国家税务局1 涉农小产权房的税收征管问题应引起重视《中国税务报》2009年4月22日于成斌、雷丁、姚丹七、上海市国家税务局1 税收与GDP周期关系分析《税务研究》2009年第10期刘新利2 企业跨境并购的涉税问题研究《涉外税务》2009年第3期金亚萍八、江苏省国家税务局1 税收课题研究文选中国税务出版社 2009年10月省国税局税科所课题组2 风险预警:增强税收管理靶向性《中国税务报》2009年10月21日陈锡平、朱海云、江鹤鸣3 税收风险管理:探索征管新机制《中国税务》2009年第11期王迎春、孙亚华等九、江苏省地方税务局1 税收执法服务标准化问题研究《税务研究》2009年第8期马伟、杨国梁、杨建中2 个税改革需要哪些基本条件《中国财经报》2009年6月23日省地税局课题组3 借鉴国外经验,强化我国税源管理《涉外税务》2009年第2期省地税局课题组2报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)4 美国应对金融危机的税收政策及其借鉴《涉外税务》2009年第12期南京市国际税收研究会课题组5 税务机关如何更有效地保护纳税人的权利《中国税务报》2009年9月23日唐跃、汪义娟等6 “绿色税制”也应向体育产业开绿灯《中国税务报》2009年4月8日赵建华、冷强7 新税法执行中的一些“细节”应明确《中国税务报》2009年12月2日王俊、汪树强8 纳税服务也要讲品牌《中国税务报》2009年12月16日朱春燕、汪树强9 税收执法服务标准化研究《税务研究》2009年第8期马伟等10 寻求外籍人员个人所得税管理的新思路《涉外税务》2009年第3期赵薇薇、王树民、张海波11 台湾地区非居民企业金融衍生工具等税收政策及对大陆的启示《涉外税务》2009年第11期徐怀庚等12 基层税务机关防范执法风险的思考《中国税务》2009年第9期唐春晖、沈潇敏13 中小企业亟盼科技创新税收激励政策“叫好又卖座”罗志军省长批示 2009年9月22日市地税局课题组14 建设网上办税服务厅的构想《税务研究》2009年第2期市地税局课题组15 某外资房地产公司关联交易避税案引发的思考《涉外税务》2009年第2期王海林、王群、余菁16 服务贸易对外支付税务备案存在的问题及建议《涉外税务》2009年第4期孟咸华、乔苏平等17 监事津贴收入如何缴纳个人所得税《涉外税务》2009年第5期毕丽等18 我国个人所得税税制模式转轨需要解决的若干问题《涉外税务》2009年第10期华雅琴、张志忠19 发达国家环保税的成功经验值得借鉴《中国税务报》2009年11月18日李凤山、卫建明20 尽快建立电子商务税收征管法律制度《中国税务报》2009年11月18日王伟21 由“网购”引起的电子商务征税思考《中国税务》2009年第8期叶晓宇2223 灌南县反映基层文化工作存在的困难及建议税收政策促进江苏沿海地区开发的借鉴和思考曹卫星副省长批示 2009年11月9日市地税局课题组《中国税务报》2009年12月23日市地税局课题组3报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)24 从税收角度剖解制约中小企业发展难题《中国税务报》2009年6月3日陈建浦、唐爱国、周立刚25 地税工作实现科学发展的路径选择《中国税务》2009年第7期唐晓鹰26 城镇土地使用税征收中存在的问题及其改进设想《税务研究》2009年第4期许建国27 关于环境保护税若干问题的思考《经济研究参考》2009年第9期朱向荣、邹鹤28 开征“物业税”应慎行《经济研究参考》2009年第9期毛祥林、吉秋根十、浙江省国家税务局1 网上税务存在的问题及发展设想《税务研究》2009年第5期王金武、袁征、罗四平2 关于促使企业合理确定出口货物销售价格的建议龚正副省长批示 2009年5月19日市国税局课题组十一、浙江省地方税务局1 美国国内收入局战略规划(2009—2013)简介《财务与会计》2009年第11期金一星、刘颖2 个体“双定户”税收超定额的法律责任应当明确《中国税务报》 2009年10月14 日陈学智十二、安徽省国家税务局1 税收理论与实践----安徽国税系统税收科研成果中国税务出版社2009年9月胡道新2 美国州际税收的分配与协调《涉外税务》 2009年第6期省国税局课题组3 纳税评估方法与技术安徽人民出版社 2009年3月周开君4 新税法实施后的国内避税问题探析《现代财经》2009年第3期丁建忠等5 关于税收稽查分级分类管理的若干思考《税务研究》2009年第5期侯伟等6 参照家电下乡政策,完善涉农税收优惠《中国税务报》2009年10月14日侯伟7 构建三位一体的税务户籍管理体制《中国税务报》2009年6月3日张立旺十三、安徽省地方税务局1 个人股权变动中的逃税行为应引起重视《中国税务报》2009年11月18日曹建华、赵勇4报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)十四、福建省地方税务局1 房产税和土地使用税征管应规范《中国税务报》2009年7月15日洪江2 税收征管模式在《税收征管法》中应有所体现《中国税务报》2009年8月19日邹利红、陈霄、全文十五、福建省厦门市国家税务局1 借鉴国际先进经验,改进国际税收征管《涉外税务》2009年第8期戴黎明2 制定税收政策时应该重视纳税服务内涵《中国税务报》2009年12月2日李华泽3 保护纳税人权利价值取向下的税制改革成就《税务研究》2009年第2期陈鹭珍4 对出口货物“视同内销”政策的探讨《涉外税务》2009年第8期林颖十六、福建省厦门市地方税务局1 加强税收协调,推进海峡两岸经贸关系正常化《涉外税务》2009年第1期厦门市地税局课题组十七、江西省国家税务局1 当代税收管理创新与发展中国财政经济出版社2009年11月周广仁2 在发挥税收杠杆作用中促进经济平稳较快发展的思考《中国经济时报》2009年3月30日周广仁3 建立基层税务人员绩效考核机制的几点思考《税务研究》2009年第2期曾光辉、吴自立、洪锦平4 做强红谷滩新区经济,促进国税收入总量增长《中国税务》2009年第12期帅盛武、宋婉媚、梁坚5 应加强增值税转型后企业固定资产税收管理《中国税务报》2009年4月8日汪跃华、周磊6 税法原理与实务南京大学出版社2009年2月张进良、吴蔚文7 鹰潭市铜产业主导下的经济税收风险调查《中国税务》2009年第6期万淑芳8 税收执法管理信息系统运行情况分析《中国税务》2009年第6期刘伟明、胡文伟、徐丽芳5报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)9 “管、评、查”互动机制运行的实践与思考《中国税务》2009年第7期张小力、肖忠卫10 构建税收征管绩效考核指标体系的设想《中国税务》2009年第8期赵水财11 浅谈和谐国税建设的目标和意义《中国税务》2009年第3期胥敏锋12 构建和谐国税的现实选择《中国税务》2009年第4期刘胜华、漆斌、胡建东13 转变观念,创新形式,优化纳税服务《中国税务》2009年第5期晏韶红14 加强对电力产品增值税的税源管理《中国税务》2009年第5期曾逸、李小春15 加强企业注销环节的税收管理《中国税务》2009年第11期陈金梅、陈刚、朱文兵16 核定征收方式的法律问题及其完善建议《中国税务》2009年第11期黄达十八、江西省地方税务局1 基于次优理论的汽车排污税研究《税务研究》2009年第4期陈平路、邓保生2 完善我国生态税收政策的若干建议《税务研究》2009年第4期李春根、计敏3 出租房屋地方税收政策执行情况调查与分析《中国税务》2009年第11期程镇平、李丽惠十九、山东省国家税务局1 国际金融危机下中国经济发展之税收调控政策研究《涉外税务》2009年第11期胡金木2 企业所得税管理的影响因素及实践探索《涉外税务》2009年第6期郭吉毅3 美国预约定价协议中采用的转让定价方法及借鉴《涉外税务》2009年第2期朱庆民、张德志、朱清4 对加强出口征退税衔接工作的几点建议《涉外税务》2009年第5期朱庆民、王吉武5 对构建现代纳税服务体系的思考《税务研究》2009年第4期张德志6 我国太阳能产业税收政策探讨《税务研究》2009年第11期市国税局课题组6报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)7 出口退税政策调整对济南经济的影响《涉外税务》2009年第11期李伟8 增值税政策调整后的管理和应对《税务研究》2009年第12期夏宗华、吕文涛9 从实践角度看纳税服务《税务研究》2009年第8期宋修广10 优化纳税服务工作的思考《税务研究》2009年第9期黄玉远11 应对国际贸易变化,规避汇率兑现风险《中国税务报》2009年3月22日王文清、高俊峰、王洪光12 当前组织税收收入工作中应注意的几个问题《中国税务报》2009年9月16日李刚昌13 税收契约视角下的纳税人权利研究《税务研究》2009年第10期王奉炜14 依据税源预计实现能力科学规划税收任务《中国税务报》2009年10月14日李锋15 关于加强出口征、退税工作衔接的思考《税务研究》2009年第9期朱彩婕、王吉武、李朝16 营销环节谨防虚开发票风险《中国税务报》2009年7月27日尹森、刘玉清17 从生产工艺倒算进项税额《中国税务报》2009年8月31日刘玉清二十、山东省地方税务局1 关于开展“应对金融危机,共谋科学发展”主题活动姜大明省长批示 2009年4月9日于希信等的情况报告2 关于推进企业二三产业分离工作情况的汇报姜大明省长批示 2009年9月24日于希信等3 关于2008年全省文化事业建设费收入情况的汇报省委常委、宣传部部长李群批示2009年1月9日于希信等4 对新时期税务文化建设的探讨《税务研究》2009年第3期于希信5 山东省社区地方税收管理的探索与实践郭兆信副省长批示 2009年10月16日于希信等6 关于金融危机对我市地税收入影响分析报告省委常委、济南市委书记焉荣竹批示2009年6月19日张志明等7 税收伦理研究中国财政经济出版社 2009年4月马奎升7报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)8 深化税收分析,建立科学的税收分析工作机制《中国税务》2009年第1期宋维刚9 税务文化建设的实践与思考《中国税务》2009年第7期宋维刚二十一、湖北省国家税务局1 税收促进“两型”社会建设研究湖北人民出版社 2009年12月刘勇、陶东元2 新时期税务基层建设湖北长江出版社 2009年12月刘勇、陶东元二十二、湖南省国家税务局1 关联方统借统贷涉税风险分析《中国税务报》2009年4月2日宋宇2 分税制改革与国、地税机构建设《税务研究》2009年第6期陈懿贇、梁莱歆二十三、广东省国家税务局1 国税、地税互为代收税款利大于弊《税务研究》2009年第10期黄学铭二十四、广东省深圳市地方税务局1 深圳市经济发展与产业结构调整的税收研究中国经济出版社2009年3月及聚声2 做好相应调整和国际磋商避免和消除双重征税《涉外税务》2009年第8期刘宁静3 对企业进口不作价设备税收流失问题的剖析《涉外税务》2009年第10期曾立新二十五、广西壮族自治区国家税务局1 中国税收专业化管理研究中国市场出版社 2009年12月霍军、蓝常高、刘景荣二十六、广西壮族自治区地方税务局1 广西地方税源建设分析《税务研究》 2009年第11期关礼2 钦州市地税局规范地方税管理《中国税务》2009年第6期李经群二十七、重庆市国家税务局1 企业所得税汇总纳税方法存在的问题及对策《税务研究》2009年第2期周德志、陈文梅8报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)二十八、四川省国家税务局魏宏副省长批示 2009年5月张崇明、周定奎、龚兵1 关于当前全省国税收入增幅低于经济增幅情况的分析报告2 探索推行一体化管理,不断提高税收征管质量效率《中国税务》2009年第4期罗元义3 税收优惠服务科学发展的调查与思考《中国税务》2009年第9期雷海兰二十九、贵州省国家税务局1 税收与民商法中国市场出版社 2009年9月王东山2 科学发展指导下的宏观调控与财税政策选择《税务研究》2009年第8期刘毓文、涂龙力三十、陕西省国家税务局1 以科学发展观为指导,构建纳税服务体系《中国税务》2009年第12期雷炳毅2 税收未被解读的密码陕西人民出版社2009年2月曹钦白3 税道苍黄西北大学出版社2009年9月姚轩鸽4 现行税收管理员制度及机构设置问题《税务研究》2009年第6期袁小平、周蒙5 税收评价指数:模型建立与实证分析《税务研究》2009年第6期刘合斌6 QFD在税收执法和管理质量评价中的应用《涉外税务》2009年第6期刘合斌三十一、甘肃省国家税务局1 更新理念,创新实践《中国税务报》2009年9月28日朱俊福《税务研究》2009年第3期刘若鸿、王应科2 关于“金税工程”三期税务决策支持系统建设的若干思考3 推进税务行政管理改革与创新的几点建议《税务研究》2009年第9期赵应堂4 浅议税收文化对税收遵从的影响《税务研究》2009年第10期贾曼莹、王应科、丁子茜5 结构性减税对甘肃省经济税收的影响《税务研究》2009年第11期省国税局课题组6 依托信息技术,创新税收管理机制《中国税务》2009年第11期刘金良、王应科、冯小明9报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)7 有必要延长西部大开发优惠政策期限《中国税务报》2009年4月8日刘虎三十二、甘肃省地方税务局1 用足用活税收政策,做大地方税收规模徐守盛省长批示 2009年8月张性忠2 坚持以人为本,强化干部培训《中国税务报》2009年12月16日廖永凯3 高收入者个人所得税纳税申报存在的问题与对策《税务研究》2009年第4期陈志健三十三、宁夏回族自治区国家税务局1 宁东国家级能源化工基地管理体制及税收利益分配研究自治区陈建国书记、王正伟主席批示 2009年5月张捷、祁彦斌、杨道先、蔡玮2 《宁夏税收研究报告》(2007-2008)中国税务出版社 2009年12月张捷、李彦凯三十四、扬州税务进修学院1 税务文化修炼经济科学出版社 2009年6月周敏、彭骥鸣2 《税收征管法》修订的几个重点问题探析《税务研究》2009年第3 期袁森庚3 完善同期资料管理,提高反避税水平《涉外税务》2009年第5期杨贵松、饶戈军4 减税政策从长远来看,将为税收增长奠定基础《中国税务报》2009年7月22日韩晓琴5 日本税制:困局中寻求“突围”《涉外税务》2009年第9期宋兴义6 国际避税地:不再安全的税收庇护所《中国税务》2009年第5期宋兴义等7 《特别纳税调整实施办法(试行)》出台的背景及意义《中国税务》2009年第6期宋兴义8 瑞银集团税案:瑞士银行百年保密制度的致命打击?《中国税务》2009年第10期宋兴义三十五、国家税务总局税收科学研究所10报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)1 新中国税制60年中国财政经济出版社 2009年刘佐刘佐等2 中国改革开放30年税收大事记(1978——2008)钱冠林副局长批示 2009年8月26日中国税务出版社 2009年3 中国税收30年中国税务出版社2009年刘佐4 关于中国税制结构优化问题的探讨《税务研究》2009年第5期刘佐5 新中国60年税制建设回眸《税务研究》2009年第10期刘佐6 新中国60年税收大事辑选《中国税务》2009年第10期刘佐7 新中国60年税制建设的简要回顾与展望《经济研究参考》2009年第55期刘佐8 新中国税收史上第一个纲领性文件《中国税务报》2009年1月16日刘佐9 新中国农业税制度的变迁《中国税务报》2009年9月20日刘佐10 新中国成立60年:五次重大税制改革《中国税务报》2009年9月25日刘佐11 新中国成立60年:税收立法大事记《中国税务报》2009年9月25日刘佐12 关于中国税务学会赴台交流的考察报告解学智副局长批示 2009年12月18日靳东升、付树林13 外国税收管理的理论与实践经济科学出版社2009年2月靳东升、付树林14 保障“走出去”企业税收权益《中国税务报》2009年4月8日靳东升等15 中国开征物业税面临的若干问题《中国金融》2009年第12期靳东升16 2008年世界税收形势变动的十大特点《经济研究参考》2009年第7期靳东升、孙红梅17 全球税收形势变动凸现两大主线《中国税务报》2009年8月12日靳东升、孙红梅18 泛北部湾次区域合作中的税收协调《涉外税务》2009年第12期靳东升、刘馨颖19 关于修订中国对外签订避免双重征税协定中方工作文《中国税务报》2009年3月8 日靳东升、魏志梅本的若干思考20 外国州际税收调查中国税务出版社 2009年7月靳万军、付广军11报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)21 美、日、德三国政府间税收收入分配制度及借鉴《涉外税务》2009年第11期靳万军、付广军22 关于赴葡萄牙和西班牙考察的报告张志勇总经济师批示 2009年6月12日李本贵、胥玉芹23 税收政策可在鼓励出口和就业及消费方面发挥作用《中国税务报》2009年2月4日李本贵24 财政收入的“两个比重”不宜再提高《中国税务报》2009年3月4日李本贵25 非居民税收管理的难点及建议《涉外税务》2009年第12期张林海26 个人所得税模式转换配套条件研究《税务研究》2009年第3期石坚27 税收政策应以促进房地产市场健康发展为目标《中国税务报》2009年5月27日石坚28 构建主体税种明确和税收负担合理的房地产税制《中国税务报》2009年7月1日石坚29 优化税收征管模式,完善税收征管法中国新闻出版社2009年12月朱广俊30 税收征管模式在征管法中的体现中国新闻出版社2009年11月朱广俊31 我国个人所得税收入分配的效应分析《经济研究参考》2009年第56期付广军32 完善个人所得税需在税率和级次设计上用力《中国税务报》2009年7月22日付广军33 中国民营经济税收报告社科文献出版社 2009年8月付广军34 税收与国民收入分配中国市场出版社 2009年12月付广军35 以信息化为依托优化税收征管流程管理《中国税务报》2009年7月15日伦玉君36 关于向综合与分类相结合的个人所得税税制模式转变解学智副局长批示 2009年5月16日陈文东的初步分析37 关于赴韩国参加第五届中韩税收研讨会的报告张志勇总经济师批示 2009年6月11日陈文东38 关于中法个人所得税研讨会综述的报告张志勇总经济师批示 2009年9月17日陈文东39 关于外国应对金融危机税收政策的情况报告肖捷局长、解学智副局长批示 2009年1月6日、14日陈琍、魏志梅、龚辉文、刘馨颖、孙红梅12报送单位和成果名称发表和领导批示情况作者(主编)40 关于参加亚洲税收论坛第六次会议的情况汇报解学智副局长批示 2009年5月5日陈琍41 税收协调的理论研究《税务研究》2009年第8期陈琍42 社会化纳税服务的国际比较研究《财政研究》2009年第9期陈琍43 中国企业承接国际服务外包税收政策国际比较研究《税务研究》2009年第12期魏志梅等44 英国应对金融危机的启示《中国财经报》2009年1月13日龚辉文45 借鉴国际经验,进一步优化中国中长期税制结构《财政研究》2009年第5期龚辉文、刘馨颖46 国外应对金融危机的最新税政《中国财经报》2009年3月3日龚辉文47 国外房地产税收政策发展近况《涉外税务》2009年第8期龚辉文48 “促进可持续发展的消费税政策研究”课题研讨会综述解学智副局长批示 2009年12月21日刘馨颖49 财税支持力度空前,日本要搞“低碳革命”《中国税务报》2009年5月13日刘馨颖50 发展中国家税制改革的五个特点《涉外税务》2009年第7期刘馨颖51 日本实施扩张性财政政策应对金融危机《涉外税务》2009年第8期刘馨颖52 新中国第一所税务学校诞生前后《中国税务报》2009年10月16日刘燕明53 五十年代税刊记述《中国税务》2009年第10期刘燕明54 税权划分的国际比较研究中国税务出版社 2009年5月孙红梅55 中国与日本转让定价制度比较与借鉴《涉外税务》2009年第12期孙红梅等56 税收特赦——英、美、意等国施行税收特赦计划解学智副局长批示 2009年12月21日张旋57 开辟新税源,英、美、意等国施行税收特赦计划《中国税务报》2009年11月11日张旋13。

力洋小学二0一三学年度学校工作总结韶华乍转,又是一年!在这一年里我镇各校在教育局、镇政府、教办的领导下,始终坚持以党的十八大精神为指针,牢固树立科学发展观,全面贯彻落实党的群众路线,做到与时俱进,做到以提高教育教学质量为中心,以"创品牌、促均衡、提质量、树形象"为工作重点,在全体师生的共同努力下,各校均取得了可喜的成绩,圆满完成了期初所制定的各项目标任务规划。

现分七个篇章总结如下:行政管理篇一、加强班子建设各校非常重视领导班子的自身建设,我们要求所有班子成员努力在工作中践行科学发展观,提出以勤政廉政、依法行政、提高效率、促进发展作为每一个班子成员追求的目标,也作为考核班子成员的主要依据。

班子成员呈现年轻化、勤劳化、钻研化、爱心化;明确分工,各司其职,但同时又努力做到分工不分家。

我们的很多中层领导身兼多职,同时还兼任着语文、数学等重要学科的教学任务。

本学期对我们行政班子成员来说是一个大考验,多次迎检创优,汇总各种材料,牺牲了很多休息时间,为学校争得了荣誉,他们的工作能力已经得到了学校广大教职员工的一致认可。

二、加强师德、师风建设教师的思想政治素质、职业道德水平如何,直接关系到学校教育质量的高低。

我镇把师德师风建设作为教师队伍建设的重点,引导教师树立正确的教育观、价值观、质量观和人才观,增强教书育人,以身立教的社会使命感,加强尊重学生、爱护学生、保护学生的责任意识,并结合开展《宁海县教育局关于进一步加强中小学教师师德师风建设的实施意见》,使我镇教师的思想道德素质有了较大地提升,使师德、师风建设有了一定的成效。

如:中心校今年有6名女教师坐产,一线教学的压力空前之大,临时代课一时无从找起,面对困难,面对挑战,学校多名老师主动为学校排忧解难,挑起重担,有的从教学一个班的到两个班,有的从一个年级的到两个年级。

他们的奉献和拼搏精神值得我们学习。

三、加大教学“五认真”管理力度本学期镇教导处严格规范学校的教育教学管理工作,努力提升学校的教育教学常规管理水平。

勐卯小学中华魂演讲比赛主持词一、开场白:杨佳怡:尊敬的各位领导、各位评委,梅林:各位老师,亲爱的同学们:合:大家下午好!杨:为了深入贯彻党的十八大、十八届三中全会精神,弘扬以爱国主义为核心的民族精神,激发我们的爱国情感,勐卯小学本学期开展了“中华魂”知识问答赛、“中华魂——放飞梦想”读后感征文竞赛。

今天我们在这里即将举行的是勐卯小学“中华魂”演讲比赛。

梅:五千年的历史,留下了璀璨的传统文化。

杨:在历史的长河中,仁人志士层出不穷;梅:中华美德熠熠生辉,民族精神世代传承。

杨:我们伟大的中华民族,孕育了五千年的辉煌。

梅:弘扬民族之精神,再现中华之雄魂。

勐卯小学中华魂演讲比赛活动即将开始。

杨:掌声有请勐卯小学党支部梁昌平书记为我们讲话。

二、介绍出席的领导:杨:首先向大家介绍出席本次比赛的领导,他们是:梅:杨:让我们以热烈的掌声欢迎他们的到来!!三、介绍评委:梅:担任本次比赛的评委有:杨:1号评委老师,2号评委老师,3号评委李雅萍校长,4号评委梁昌平书记,5号评委滕玲老师,6号评委方渊老师,7号评委张瑞老师。

梅:担任此次比赛的记分员是:黄转玲老师赵女萍老师杨:让我们以热烈的掌声对他们接下来的辛苦工作表示衷心地感谢!四、比赛过程:杨:勐卯小学“中华魂”演讲比赛,现在开始!我们期待着每位选手精彩的表现!梅:首先我们以热烈的掌声欢迎一号选手周丽娜上场,她来自勐卯小学小学 218班,她演讲的题目是《放飞梦想》。

(请2号选手做准备.)杨:接下来上场演讲的是 209班蔺淑娴同学,她演讲的题目是《放飞梦想》。

(请3号选手做准备.)梅:华夏的炎黄子孙所传承下来的民族精神却世代相传、生生不息。

让我们传承民族精神,用青春和热血铸就伟大的中国梦!接下来上场演讲的是班 214班同学穆相昆生,她演讲的题目是《放飞梦想》。

(请4号选手做准备.)杨:接下来上场演讲的是216班杨雨珊同学,她演讲的题目是《放飞梦想》。

(请5号选手做准备.)梅:爱我中华,就应当为民族的腾飞奉献智慧和力量;爱我中华,就要让火红的青春绽放出生命的芳华。

书苑小学2013年春季期中表彰大会议程全体肃立,奏唱《中华人民共和国国歌》!------ 请坐下!各位老师,同学们,尊敬的各位家长:大家上午好!“又是一年春草绿,依然十里杏花红”。

新的学期,开启新的希望,新的学期,承载新的梦想。

光阴荏苒,日月如梭,不觉间这一学期已走过了一大半的路程,一路走来让我们有收获成功的喜悦,也有经历失败的痛苦。

今天,我们书苑小学全体师生和家长代表相聚在这里,召开表彰大会。

表彰通过自身努力、刻苦学习,在各方面取得优秀成绩的同学,也希望通过这样一次表彰会,总结经验,发扬成绩,团结和动员全体同学以更加崭新的思想观念、更加饱满的精神状态,积极投入到今后的学习中去,做一名全面健康发展的好学生。

今天有很多家长放弃了休息时间,参加学校的表彰大会,我在此代表学校领导及全体师生,向出席本次会议的各位家长代表表示衷心的感谢!(鼓掌)在大会开始之前,我对今天大会的纪律做以下要求:1.全体教师按班就坐,并维持好班级秩序。

2.全体同学做到安静、认真,保证大会的严肃性;3.要保持会场的干净、整齐;4.大会结束时,要听从学校安排,有按秩序退场。

下面我宣布:书苑小学2013年春期期中表彰大会现在开始!第一项:请用热烈的掌声欢迎教导处滕主任宣布荣获特等奖,一、二、三等奖及进步奖名单让我们用热烈的掌声对以上获奖的同学表示祝贺!(同学们:这是一批学习优秀,习惯优良,品学兼优的学生,他们每天努力,同学们都看在眼里;他们每一点进步,老师都倍感欣慰,印象深刻。

他们的收获,他们的人格,让我们不得不承认这就是成功。

幸福或许不排名次,但成功必须排名次。

此时此刻,我想在座的每一位同学的心中都有一种力量在鞭策着自己,努力努力一定要努力,因为,我们的学习,不是缺乏时间,而是缺乏努力。

努力吧同学们,你一样会成功。

)第二项:请用热烈的掌声欢迎政教处范主任宣布优秀少先队员,德育标兵获奖名单。

优秀班级体、优秀班主任名单。

让我们再次用热烈的掌声对以上获奖的同学表示祝贺!生命是一个过程,优秀是一种习惯。

DesignandImplementationofElectronicCommunitiesLEVENTV.ORMAN orman@Cornell University, JohnsonGraduateSchoolof Management, Ithaca NY 14853Abstract. Electroniccommunitiescanbedesignedtoorganizeconsumers,topooltheirpurchasingpower, andtoguidetheirpurchasingdecisions.Suchcommercialelectroniccommunitieshavethepotentialtofaci l-itate the creation of novel marketplaces, and even radically change the buyer–seller interaction, as physicalcommunities did throughout the history. Commercial electronic communities are groups of consumers thatparticipate in the marketplace as a single unit. In addition to bargaining power gained from such bundling,such communities can expand markets by reducing market uncertainty, and they have the potential to dras-tically reduce transaction costs. However, these benefits are not automatic, and the optimum design andimplementation of communities are critical to their economic success. The size and the makeup of a com-munity, the size and the nature of the product bundle it offers, and the concise description and efficientimplementation of the community as an electronic marketplace are all critical factors for the success of acommunity.Keywords:electroniccommunities,electronicmarkets,marketdesign,marketimplementation,distributed markets1. Electronic communities Electroniccommunitiesarevirtualgatheringplacesforpeoplesharingcommoninterests.Bulletin boards and newsgroups were the earliest examples of virtual gathering places. Largenumbersofbulletinboardsandnewsgroupshavebeencreated,eachcharacterizedbyatheme,andeachattractingusersinterestedinthattheme,andfacilitatinginteractionand information exchange among them. Electronic communities are the current multi- mediaversionsoftheseearlyattempts,wherenotonlytextmessagesareexchanged,but photographs, audio and video files, interactive chat, conferencing, and database accessare available to community members [12]. Although communities have been studied extensively as a social phenomenon, their commercial applications have been limited[5,12,15]. Early Internet vendors have established communities to facilitate interaction amongtheircustomers,inanefforttoengenderloyaltyandasenseofcommunityamong theircustomers,andtoengagecustomerstoextendthelengthofstayattheirsite[2,10]. Suchvendorcreatedcommunitiesareuseful,butverylimitedinscopeandfunctionality ascommercialenterprises.Theyarelimitedinscopetoonevendor’sproducts,andthey arelimitedinfunctionalitytoserveonlythecommercialinterestsofoneparticularven-dor. More recently, buying cooperatives have been formed to pool buyers on the web to takeadvantageofvolumediscountsofferedbyvendors[2,10].Thesenewwebbusinessesaremoreambitiousintheireffortstoorganizeconsumers,butstillfallfarshortofafullscale commercial electronic community, since membership is very ephemeral, and lim- itedtoasinglepurchasingdecisionforasinglegoodorservice.Electroniccommunitiesdesigned to organize consumers, pool their purchasing power, and guide their purchas-ing decisions have the potential to facilitate electronic marketplaces, and even radicallychange the nature of buyer–seller interaction, as physical communities throughout thehistory have often changed the nature of physical marketplaces. We will refer to such electroniccommunitiesas commercialelectroniccommunities.Commercial electronic communities in their most general form are communitiesthat participate in the marketplace as a single unit. Such communities are similar toconsumer cooperatives, and they are often impractical in the physical world due to the intensiveinformationprocessingrequirementsinformingthecommunity.HealthMain-tenance Organizations (HMO) are typical examples of commercial communities in thephysical world since the members negotiate with health care providers as a group, andall members are entitled to all services provided by the HMO, which are bundled into themembershipprice.Suchcommunitiesaremorecosteffectiveinelectroniccommerce becauseofthereductionincommunicationandinformationprocessingcoststhatarees- sentialindesigning,forming,andoperatingacommercialelectroniccommunity,which wouldoftenbeprohibitiveinthephysicalworld.Thecriticalissuesindesigningelectronic communitiesrangefromdeterminingthefeasibilityandtheoptimumdesignofcommu-nitiesto theimpactof such communitieson the markets andtheeconomyingeneral. Communitiescanbeviewedasbundlesofconsumers,andassuchtheyaresimilarto bundles of goods, and their effect on the marketplace is symmetric to bundling ofgoods. There is an extensive literature on bundling and its effect on the marketplace.That literature is relevant both because of the similarities of the impact on the market, butalsoforcomparisonpurposestodeterminewhatcommunitiescanprovideaboveandbeyond bundling of goods[3,4,7,8].2. Design issuesCommunity design is an interdisciplinary endeavor. Technology and economic issues areintertwinedinseparably.Theoptimumdesignrequiresacomprehensivetreatmentof bothtechnicalandeconomicissues,astheyrelatetoboththeinternalorganizationofthe communityand itsimpact on the markets [5,11].The most fundamental problems are in the internal organization of communities,as that defines the relationship between the community and its members. There is aspectrum of possibilities: At one extreme, a pure community is where all members are entitledtoallgoodsandservicesprocuredbythecommunityoperator,allbundledinonemembership price. A segmented community is where members have varying privileges andentitlements,whichisequivalenttomultiplesubcommunities.Attheotherextreme,a community where the members are only entitled to the option to acquire any of the goodsandservicesforadditionalfees,whichisequivalenttoaretailerwithmembership discountsasinshoppingcards.ApurecomDESIGNANDIMPLEMENTA TIONOFELECTRONIC COMMUNITIES 165intensiveinformationprocessingrequirements,butquitefeasibleinelectroniccommercewith its reduced communication andinformationprocessingcosts.Purecommunitiesraiseanumberofdifficultorganizationalandtechnicalquestions.The effective description of a community for the market place is the most fundamentalmunitiesareabstractstructures,andtheyneedtobedescribedforthemarketplace to facilitate the consumers’ decision processes to join a community. At a sim-plistic level, they could be described as bundles of goods and services procured by the community operator in the past, and those bundles can be used as an indicator of future procurements.Themembersstayinthecommunitytotheextentthatthevaluegenerated bythecommunityoperatorjustifiestheirmembershipfees,andthevaluetheyreceiveishigher than the value generated by competing communities plus switching costs. Such descriptions are practical, but ignore the vast potential of communities combined with abstractdescriptions.Abstractdescriptionsforabstractstructures,suchascommunities,are likely to generate value by encouraging abstract decision making, and a significantdrop in transaction costs, above and beyond what can be achieved with bundling. Thetypical examples in this area are mutual funds for investors, where the funds are de-scribed in terms of their risk/return characteristics, not as bundles of stocks, bonds and commercial papers. Mutual funds are pure communities with abstract descriptions, andprovide a rare but almost perfect example from the physical world. Another exampleof a pure community is governments at various levels. The government leadership iselected on the basis of abstract and often philosophical descriptions, such as smaller government or environmental protection. The government then enters the marketplace andparticipatesinpurchasesonbehalfofthecitizenrythatitrepresents,andallcitizensbenefit(potentially)ernmentsprovidea second rare example of a pure commercial community. The fundamental information systemquestionishowtoeffectivelydescribecommunitiesforthemarketplace,andhow tomatchthosedescriptionstotheabstractdescriptionsofconsumers.Thematchingpro- cesscanbeautomatedasindatabasesearches,semiautomatedasintextsearchengines,or manual as in the physical world with mutual funds, HMO’s, or governm ents. In allcases, an effective and preferably abstract description both for the communities and for theindividualsis essential[13].Communities are not completely independent of each other. Not only their mem-berships may overlap, in effect creating subcommunities at the intersection, but also communitiesmaycombinetoformlargerandmoreabstractcommunities.Acommunity ofsingleparentsoftoddlerswouldbeasubcommunityofsingleparents,andthatwould beasubcommunityofparents.Acommunityofmembersbelongingtoacitygovernment arealsomembersofthecorrespondingstategovernment.Suchhierarchicalrelationshipscan create a rich tapestry of abstractions and aggregations, and can lead to powerful marketmechanismsthatarequitenovel.Suchstructuresarerareinthephysicalmarkets, oreveninthecurrentelectronicmarkets,buttheyarequitecommonininformationsys-tems in the form of database abstractions. As markets are implemented more and more aspuredatabaseapplications,andconsumersandproductsarerepresentedaselectroniccollections of data, such database constructs have immediate applications in buildingmunityisrareinthephysicalworld,duetoitsabstract market structures. All the accompanying database concepts such as inheritanceof attributes within a hierarchy, and aggregation of semantic descriptions to form moreabstract descriptions,allapplydirectlytothehierarchyofcommunities[1,11].Communities do not exist in a vacuum, but participate in markets. The interactionof communities with markets also raises a number of significant research issues. The mostobviousadvantageofacommunityisthatitallowsconsumerstobandtogetherand negotiateasagroup,andgainmarketpower.Inthisrespect,acommunityactsasabuyingcooperative. Moreover, a community operator who participates in the market place forthe whole community, and purchases goods and services for the whole community, canreduce transaction costs significantly. Such reduction in transaction costs of consumers allowsthemtoengageinpricediscoveryandsearchmoreeffectively,andeliminatesthe informationasymmetrybetweenconsumersandsuppliersthathavealwayscharacterizedphysical markets. Communities also benefit suppliers, since they allow the suppliers todo more effective targeting by using community descriptions, and to do more effective andlargescalebundling,oftenacrossmultiplevendors,totakeadvantageofconditionalutilities, and cross subsidies within bundled goods. Finally, communities lead to more expanded markets, since they allow better price discrimination, although the excessprofits extracted through community-based-price-discrimination do not necessarily allaccrue tothe suppliers.Markets themselves may need to be redesigned to accommodate communities. Communitiesarenotlikelytoreacttopriceandqualityinformationinthesamemanneras individuals. The information needs of a community operator are much more exten-sive and often much more formal. The databases that support markets may have to be extendedtosupportmuchmoredetailedandabstractdescriptionofgoodsandservices,and also incorporate the descriptions of communities for possible automatic matching. Exchangemechanisms,paymentsystems,marketclearingalgorithms,trust,security,and insurancemechanismsmayallneedtobeslightlymoreformal,morecomprehensive,and moreautomatedtoaccommodatetheneedsofcommunities.Theprimaryreasonforsuch formalityisthelargesizeandvalueofeachtransaction,asopposedtosmallunitsoftrans- actionswhenthemarketiscomposedofindividuals.Advertisingandconsumerbehavior islikelytochangedrastically,becauseoftheintroductionofacommunityoperatorasanintermediary to transactions, and as an agent of the consumer. The consumer-business interactionresemblesmoreabusiness–businessinteraction,whenacommunityisformed andthecommunity operatorintervenes asanintermediaryon behalfof thecommunity. Communities themselves create new types of markets, where the consumers can shopforcommunities,findcommunitiesthatbestmatchtheirneeds,andbecomemem-bers.Thestructureofsuchsecondarymarketsisadifficultresearchissue,anditishighly intertwinedwiththesemanticdescriptionofcommunitiesexplainedaboveasatechnical researchissue.Membershippricingandcrosssubsidieswithinthecommunityaremore advancedissuesthatrequireasaprerequisitetheresolutionofcommunitydescriptionand communitysearchissues.Whyandhowanindividualbecomesamemberwilldetermine hiswillingness to pay for membershipandstaya member. DESIGNANDIMPLEMENTATIONOFELECTRONIC COMMUNITIES 1673. BargainingpowerCommunities can have economic benefits both for consumers and for businesses. The obviousbenefittoconsumersisthenegotiatingpowergainedbypoolingtheirpurchasingpower.Theobviousbenefittothevendorsisawelldescribedandfocusedmarketthatis availableforprecisetargeting.Theadvantagetobothpartiesisasignificantreductionintransaction costs, due to bulk purchasing for the whole community, and better-targeted marketing. A less intuitive advantage of communities is their ability to expand markets andgenerateasurplusaboveandbeyondwhatcouldbeachievedwithoutcommunities. Suchaneconomicsurpluscanmakeallpartiesbetteroff,providingastrongjustificationforthe creation ofcommunities.However,aneconomicjustificationforcommunitiesdoesnotrequireforallpartiestobebetteroff,butonlythecommunityitself.Acommunityorganizercanformacom- munityasaseparateeconomicentitythatentersthemarketplaceonbehalfofitsmembers. Suchacommunitywouldbeeconomicallyfeasibletotheextentthatitcanextractasur-plus for the community from the marketplace. That surplus can be viewed as additional consumersurplusforthecommunitymembers,orasprofitsforthecommunityoperator, oracombinationofboth,dependingonthenatureofthecommunity.Thatsurpluscanbe aportionoftheeconomicsurplusgeneratedbythecommunity,leavingtheremainderofthe surplus for the suppliers, making all parties better off. Alternatively, the communitysurplus may be extracted from the suppliers’ profits, by using the increasing bargain-ing power of the consumers in the community, leaving the suppliers worse off. Either possibility, or a combination ofthetwoleads toaneconomicallyfeasiblecommunity. Considerapopulationof4consumers,andamonopolistsupplierofasinglegood.Let the reservation prices of the consumers for the good be 4, 7, 8, and 9 respectively,and the marginal cost of producing the good is 2/unit. The optimum price set by themonopolist will be 7, with a total profit of 15, and a total consumer surplus of 3, asshownin figure1. Nowconsiderapairwisegroupingoftheseconsumersintotwocommunities,withreservationprices4+7 = 11,and8+9 = 17.Eachcommunityconsistsof2consumersand will buy a package of 2 units of the good, if its price is below its reserFigure2. The total profit and the total consumer surplus for 2 communities with reservation prices 11 and17, and amonopolist supplier ofa good with marginal cost of4.or it will buy none. The marginal cost of a two-unit package is 2*2 = 4. The optimum pricesetbythemonopolistforatwo-unitpackageis11,thetotalprofitsare14,andthetotal consumer surplusis 6, as shown infigure2.Clearly, the communities, by using their bargaining power, extracted additionalsurplus, raising it from 3 to 6, at the expense of the supplier, whose profits fell from15 to 14. The community accomplished this by pressuring the supplier to lower its unitprice from 7 to 11/2 = 5.5, as a direct result of bargaining power gained by forming a community.The additional consumer surplus is not necessarily achieved at the expense of munitiescanexpandmarkets,andgeneratesurplusthatcanbenefitall.Bothconsumersandsupplierscanbebetteroffasaresultofcommunities.Considera different pairwise grouping of the four consumers into two new communities, with reservation prices of 4 + 8 = 12, and 7 + 9 = 16. The marginal cost of a two-unitpackage is still 4. The optimum price set by the seller will be 12, with a total profit of16, and thetotal consumer surpluswillbe4,asshowninfigure3.Clearly, these communities generated enough surplus to make both parties betteroff.Theseller’sprofitswentupfrom15to16,andthetotalconsumersurplusrosefrom3to4. The communities accomplished this by expanding the market, and generatingadditional economic surplus for alltoshare.vation price, DESIGNANDIMPLEMENTATIONOFELECTRONIC COMMUNITIES 169Figure4.Profitasafunctionofpriceandmarketvariance,whichsummarizestheproblemfacedbysuppliers.Not all communities are beneficial. Some communities do not benefit the con-sumers,andhencetheyarenoteconomicallyviable,sincetheconsumershavenoincen-tive to join them. Consider, a third possible pairwise grouping of these consumers into twocommunitieswithreservationprices4+9 = 13,and7+8 = 15.Themarginalcostof a two-unit package is still 4. The optimum price for the seller will be 13, with totalprofitsof18,andatotal consumer surplusof2,asshowninfigure4.Clearly,theconsumersurplusislowerthantheopenmarket,sinceitwentdownfrom3to2.Consequently,thesecommunitiesarenoteconomicallyfeasible,sinceconsumers havenoincentivetojointhem.Thecriticalquestionforacommunityoperatorishowto determinetheoptimumcommunity,andtodesignittomaximizethecommunitysurplus. Thecriticalvariableisthevarianceofreservationprices,ormarketuncertainty.Itis nosurprisethatasthevariancedecreases,thesupplier’sprof itsgoupbecauseofbettertar- getedpricing,andconsumersurplusfalls.However,thatisnotuniformlyso.Atveryhighvariances,thetrendcanreverseitself,themarketcanshrinkconsiderablybydraggingtheconsumer surplus down, and the suppliers may take advantage of the shrinking market byconcentratingon thehighendcustomers,andcanactuallyincreasetheirprofits.Thebasic economic problem is a game theoretic problem. The suppliers control prices and setthemoptimallytomaximizeprofits,andcommunitiescontrolmarketuncertaintyandsetthem optimallybydesigningtheircommunitiestomaximizetheirsurplus.Suppliers’problemistosetthepricesoptimallyforagivenmarketvariancecreatedbycommunities. Thecommunities’problemistosetthemarketuncertaintyoptimallybydesigningtheir communitiesgiventheassumptionthatthesupplierswillrespondbysettingpricesopti-mally.Givenauniformdistributionofreservationprices,simulationsusingMathematicasoftware show that profit is a unimodal function of price, for each market variance, andthe optimum price decreases as the market variance increases. Figure 4 summarizes theproblem facedbythesuppliers.Similarly,theconsumersurplusisaunimodalfunctionofmarketvarianceassuming anoptimalsettingofpricesbysuppliers.Acommunityoperator’sproblemistodesignthe optimumcommunitythatmaximizesthecommunitysurplus,bycomputingtheoptimumpoint v,as shown in figure 5. 170 ORMANFigure5. Theeffect of marketuncertainty on thesupplierprofits and community surplus.4. Transactioncost Economicviabilityofacommunitydoesnotrequireamonopolistselleragainstwhicha communitycanexercisebargainingpower.Acommunitycanbeviableeveninacompet- itiveenvironment,withcompetitiveprices.Inacompetitiveenvironment,evenwhenthebargaining power is not a relevant issue, a community can produce significant surplusthrough savings in transaction costs. Savings in transaction costs can be considerablesince the members of the community do not have to engage in market transactions in- dividually, but the community operator executes market transactions on behalf of all members. Such a community would be able to reduce transaction costs in proportionto the size of the community since the community operator would develop expertise,perform the search for goods, and execute each transaction only once on behalf of all members.Moreover,thecommunityoperatorwouldbundleanumberofproductsthatarerelevant to the community, and further reduce transaction costs by developing expertisein a line of products, and by using the expertise developed in one product in acquiringother similarproducts.Economic viability of a community does not require the community to be an or- ganicstructureemergingspontaneously.Acommunitycanbecreatedasanindependent businessbyacommunityoperator.Thecommunityoperator’sobjectiveistodesignthe optimumcommunitytomaximizeitsprofit.Thecommu nityoperator’sprofitisaportion ofthesurplusgeneratedbythecommunity,whichwasdiscussedintheprevioussection.The community operator’s profit is determined by the revenues r from members in the formofmembershipfees,thepaymentsc tosuppliersforthegoods,andthetransactioncosts t: p = r -c -t.Ina competitive environment, since the cost of goods is exoge-nous,andalsothetransactioncostsareindependentofsize,thena¨?vecommunitydesignwould aim for the largest possible community, to maximize revenues, and to amortizethe transaction costs over the largest possible membership base. In fact, the largest pos- siblecommuntiyisrarelytheoptimum,becausethesizeimpactsthecompositionofthecommunity.Acommunitydoesnotchooseitsmembersrandomly,butselectsthosethat aremostrelevanttothethemeofthecommunity,orinotherwords,thosewhoarewilling topaythemostforthegoodsandservicesofferedbythecommunity.ConseDESIGNANDIMPLEMENTA TIONOFELECTRONIC COMMUNITIES 171effective reservation price of the community members decreases as the community size increases, since the community has to accept lower paying members to the community. Themembershipfeesaredeterminedbythereservationpriceofthelowestpayingmem- bersofthecommunity,sinceotherwisethosenewestmembersofthecommunitywouldnot join. Even a price discrimination scheme, such as the subsidy system discussed inSection 3 would result in a reduction of the average reservation price of the commu-nity as the commmunity size increases, and lower paying members are admitted. This fundamental problem with size is a direct result of the increasing heterogeneity of the community with increasing size. Consequently, the optimum community size is deter-mined by a trade off between the larger savings from transaction costs, and the smaller revenuesfrom amoreheterogeneouscommunity,asthecommunity sizeincreases. Considerfourconsumerswithreservationprices4,7,8,and9forasingleproduct whoseacquisitioncosttothecommunityis2perunit,andthetransactioncostis6.Thecommunity operator tries to set the membership fee optimally, which determines theoptimum community size by admitting all those whose reservation prices are above the membership fee. The optimum membership fee for this community would be 7, with communitysize 3 as showninthetable below.Membership fee community size revenues cost ofgoods transaction cost profit.4416 86 273 21 6 6 9 (optimum)8216 46 691 926 1Now consider the same four consumers with two products. The reservation pricesare 4, 7, 8, and 9 for the first product, and 2, 2, 4, and 8 for the second, and the total reservationpricesforthebundleare6,9,12,17.Thecostofacquiringthethebundleis assumedtobe4,andthetransactioncostremains6.Theoptimumcommunitymember-ship fee will be 12 with the resulting community size 2 for the bundle size 2, as shown in the table below.Membership fee community size revenues cost ofgoods transaction cost profit.6424 16 6 29327 12 6 912 2 24 8 6 10 (optimum)17 1 17 4 6 7Finally, consider the same consumers with a bundle of three products, where the reservation prices are 4, 7, 8, 9 for the first, 2, 2, 4, 8 for the second, and 0, 1, 2, 6 for thethird,withtotalsof6,10,14,23.Thecostofthebundleis6,andthet172 ORMANremains6.Theoptimumcommunitymembershipfeewillbe23withcommunitysize1forthe bundle size3, asshown in thefollowing table:Membership fee community size revenues cost ofgoods transaction cost profit.6424 24 6 –610 3 30 186 614 2 28 126 1023 1 23 6 6 11 (optimum) Itisnotacoincidencethatthereisaninverserelationshipbetweenthecommunitysize and the bundle size for the optimum communities. Intuitively, this result follows fromtheexistenceofanoptimumheterogeneitywithinacommunity.Thatheterogeneityor variance within a community can be achieved by increasing the community size or thebundlesize,orinotherwordsincreasingonerequiresdecreasingtheothertostayat theoptimumlevelofvariance.Anotherintuitiveexplanationisthetendencyofbundling toreducethevarianceofreservationpricesoverthewholepopulation,andclusterthem around the mean. This observation follows immediately from the central limit theorem. However,areductioninvarianceforthewholepopulationactuallyincreasesthevariance ifwerestrictourselvesonlytothetailsofthedistribution.Sincethecommunitydoesnot select its members randomly, but specifically from the upper tail of the distribution, it facesincreasingvariancewithbundling.Consequently,increasingbundlesizeleadstoa sharperdropinmembers’willingnesstopayasthecommunitysizeincreases,andhencethe optimum community size becomes smaller. We will now develop these arguments moreformally.Let p be the profits, r revenues, c the cost of goods, and t is the transaction cost.p = r -c -t.Revenues are dependent on the membership price l and the size of the community s: r = ls. The membership price l is the lowest reservation price among members per product in the bundle, and it is determined by the community size s and the bundle size b. The decision variables for a community organizer are the communitysize and the product bundle, and the membership price l is set at a level to attract thatsize community to that bundle. For a small community with a small product bundle,the membership price can be set high to attract only those that are most interested in thatproductbundle.Asthesizeofthecommunitygrows,thecommunitybecomesmore heterogeneous, and to attract lower paying members, the community has to lower its membership fee. However, the drop in membership fees are the steepest for smaller communities, and as the community grows the highest paying members are exhausted, 2 2and the rate of drop flattens out. Consequently, ?l/?s = l < 0 and ? l/?s = l > 0.Similarly,asthebundlesizebgrows,thereservationpriceforthebundlegrowssincethe valueofallitemsareassumedtobenonzero,butthegrowthrateisslowerasthebundlegrows, and the most desirable items for the community are exhausted. Consequently,* 2 2 **?l/?b = l > 0and? l/?b = l < 0.Onthecostside,normalizingcostswithrespectto reservation prices eliminates the variance of absolute cost values, and we can safelyransactioncostquently,theDESIGNANDIMPLEMENTATIONOFELECTRONIC COMMUNITIES 173assume that the cost of a bundle increases with the size of the bundle at a constant rate,* 2 2 **?c/?b = c > 0and? c/?b = c = 0, but the bundle cost is independent of the 2 2 communitysize,?c/?s = c = 0and? c/?l = l = 0.Weknowfromdefinitionsthat p = ls-cs-t,andthecommunityoperatorneedsto maximize profit p with respect to community size s and the bundle size b, resultingin: p = l +l s -c-c s = 0whichimpliesthatl s = c-l istheoptimalityconditionsince p = l +l s +l -c -c s -c < 0forsmalls fromtheassumptionsabove.* * * * *Similarly, p = l s-c s = 0impliesthatl = c istheoptimalityconditionsince** ** ** ** **p = l s -c s < 0sincel < 0andc = 0fromassumptionsabove.The two optimality conditions can be used to derive the optimum community size andtheoptimum bundlesize asshown graphicallyinfigure 6. Therecanbemultipleoptimumsolutions,sincecostisnotnecessarilyalinearfunc- tionofthebundlesize.Whentherearemultiplesolutions,thereisaninverserelationshipbetweenthe bundle sizeand the communitysize alongtheefficientfrontier. *The preceding analysis depends heavily on the computation of l and l , the price sensitivityofthecommunitywithrespecttocommunitysizeandthebundlesize.These* *Figure6. l = c condition is used to compute the optimum bundle size b1 in the first graph, and then l s = c - l condition is used in the second graph to compute the optimum community size s1 and theoptimum community membership feel1 fromthe given bundlecost c and bundle size b1.Figure7. Theinverserelationshipbetweencommunitysizes andthebundlesizebisderivedwherethebold * *arrow shows the increasing b values, and the bold curve shows the efficient frontier where l = c . These。