溃疡性肠炎+共识2010-3

- 格式:pdf

- 大小:544.43 KB

- 文档页数:30

溃疡性结肠炎临床疗效对比观察【摘要】目的:观察与分析益生菌联合美沙拉嗪治疗溃疡性结肠炎的临床疗效。

方法:选择2009年2月-2012年2月在笔者所在医院进行治疗的溃疡性结肠炎患者100例作为研究对象,并随机分为观察组及对照组,各50例。

观察组给予益生菌联合美沙拉嗪的治疗,对照组仅采用美沙拉嗪治疗。

治疗结束后对比观察两组临床疗效及不良反应。

结果:经治疗观察组总有效率90.0%,对照组总有效率78.0%,观察组复发率8.0%,对照组复发率26.0%,两组比较差异均有统计学意义(p0.05),具有可比性。

1.2 方法两组患者在给予常规抗炎、营养补液等对症支持的基础上,观察组给予美沙拉嗪1 g/次,4次/d,口服;同时还给予益生菌制剂(双歧三联活菌胶囊)0.42 g/次,口服,3次/d,治疗时间为4周。

对照组采用美沙拉嗪的用药方法与观察组相同。

两组患者均在三餐前服用,同时在治疗期间给予患者健康饮食指导。

试验期间患者不接受其他治疗。

治疗结束后,均行结肠镜检查,镜检结果显示有效者,则继续服用,随访3个月统计复发率。

1.3 疗效评价标准根据中华医学会消化病学分会制定的《溃疡性结肠炎疗效判定标准》,显效:临床症状、体征消失,经结肠镜检查黏膜大致正常,无炎性反应;有效:临床症状、体征基本消失,结肠镜复查肠黏膜轻度炎性反应或假息肉形成;无效:临床症状、体征和病理检查无改善[4]。

1.4 统计学处理所得数据均应用spss 13.0统计学软件进行分析处理,计量资料采用t检验,计数资料采用字2检验,p<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2 结果根据疗效标准,经4周的治疗后观察组显效29例,有效16例,无效5例,总有效率90.0%,3个月复发4例,复发率8.0%,对照组显效21例,有效18例,无效11例,总有效率78.0%,3个月复发13例,复发率26.0%,观察组总有效率明显高于对照组,复发率明显低于对照组,差异均有统计学意义(p<0.05),见表1。

欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第3版[译者按]为普及和提高中国炎症性肠病诊断及治疗水平,推动中国炎症性肠病事业的发展,中国炎症性肠病联盟组织和实施了欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第三版的翻译。

欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第三版代表了当今全球溃疡性结肠炎诊断及治疗的最高水准,值得借鉴。

关于对欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第三版的借鉴,应该根据患者的具体情况进行合理取舍,切不可生搬硬套,也不可断章取义。

同时,也应该结合医者自身的临床经验,灵活运用该共识:在缺乏临床经验时,应该注重诊断和治疗的规范化;在具有一定的临床经验后,应该注重诊断和治疗的个性化,从而提高对溃疡性结肠炎的诊断和治疗水平。

欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第三版的翻译工作是由近50位有志于中国炎症性肠病事业的专业人士完成的,是他们的辛勤劳动成果。

虽然该共识的翻译工作是枯燥和繁琐的,但是,所有参与者都是自愿加入的,而且他们的工作卓有成效。

在此,中国炎症性肠病联盟向所有参与翻译、校对和审核的同仁致以崇高的敬意!经过翻译、校对和审核后,欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第三版的中文翻译版如今按计划在中国炎症性肠病联盟内部正式发布。

值此五一节前夕,谨以此共识作为对所有辛勤从事炎症性肠病工作的同仁的献礼,恭祝各位安康!出于对知识产权的尊重,在此郑重声明:任何人不得以任何理由将欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第三版的中文翻译版的任何内容用于中国炎症性肠病联盟内部个人学习之外的任何其他活动,包括商业活动。

欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第三版的翻译、校对和审核流程如下。

1.中国炎症性肠病联盟发起欧洲溃疡性结肠炎循证共识第3版的中文翻译。

2.华中科技大学同济医学院附属协和医院消化科付妤副教授根据各位参与者的专业领域负责组织和分配任务,并负责翻译稿的回收和汇总。

3.各章节的翻译者自行进行翻译和校对,为彰显责任和荣誉,每一位翻译者均在各自负责翻译的内容末尾署名。

4.翻译稿第1-8章由昆明医科大学第一附属医院消化科缪应雷教授进行第一轮审核。

中医药治疗溃疡性结肠炎的研究进展摘要:溃疡性结肠炎是一种原因不明的慢性非特异性肠道炎症性疾病,在西医治疗上,该病的复发率偏高,疗效时间偏长,价格偏贵等不足。

近期研究表明,中医药在减轻UC患者腹痛、腹泻等临床症状、减少该病的复发等方面取得了显著的疗效。

现将中医治疗UC的辩证分型、经方治疗、中西医结合等方面进行归纳总结。

关键字:溃疡性结肠炎;中医药;研究进展;溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis,UC)是消化系统常见的疑难病,其发病原因至今无法明确的,临床表现为腹痛、腹泻、黏液脓血便、里急后重,病程多在4~6周以上[1]。

现代西医治疗UC,临床上常给予氨基水杨酸制剂、免疫抑制剂、生物制剂、微生态制剂及手术等方法,但仍存在该病的复发率偏高,疗效时间偏长,价格偏贵等不足。

近期的研究表明,中医药在减轻UC患者腹痛、腹泻等临床症状、减少该病的复发等方面取得了显著的疗效。

一、中医的病因病机中国的医学中并没有UC一词,但根据其临床的变现可以反应与UC相应的病名。

2009年中华中医药学会脾胃病分会制定的“溃疡性结肠炎中医诊疗共识意见”[2]将本病归属中医“痢疾”“久痢”和“肠澼”等病范畴。

中医认为UC的病因与外感时邪、饮食不节(洁)、情志不畅、禀赋不足等有关,病机属邪蕴肠腑,气血壅滞,传导失司,脂络受伤。

病位在肠,与肝、脾、肾、肺诸脏密切相关。

二、中医内治法(一)辩证论治李毅等[3]研究表明UC常见中医证型依次为肠道湿热证、脾胃虚弱证、肝郁脾虚证、脾肾阳虚证、寒热错杂证、血瘀肠络证、阴虚肠燥证。

宋晓红[4]将UC分为湿热型、肝郁气滞型、脾阳不振型、脾肾阳虚型;其中治疗湿热型的处方为白术、白头翁、苍术、赤芍各15g,黄芪、木香、白蔻、竹茹、陈皮、黄连、佩兰各10g、桔梗9g、当归12g;治疗肝郁气滞型的处方为白芍、焦三仙、柴胡、香附、桃仁各15g,当归10g,防风、槟榔、大黄、红花、陈皮、炒枳壳各6g;治疗脾阳不振型的处方:土白术、党参、炙黄芪各15g,肉蔻、炙甘草、炮姜、陈皮各10g,柴胡、升麻各9g,当归6g,大枣10枚;治疗脾肾阳虚型的处方:土白术15g,党参、罂粟壳、补骨脂、诃子肉、肉桂、赤芍、吴萸、肉蔻、当归各10g,木香9g;治疗14d后,观察组患者临床治疗总有效率为95.00%(57/60),对照组为 71.67%(43/60)。

溃疡性结肠炎定义溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)又称慢性非特异性结肠炎,是一种以大肠粘膜好粘膜下层炎症为特征的病因不明的慢性炎症性疾病。

病变部位多位于直肠和乙状结肠。

病理改变主要发生在大肠粘膜与粘膜下层,以溃疡为主。

临床特点腹泻、粘液脓血便、腹痛和里急后重等。

病程长,病情轻重不一,常反复发作。

性别与年龄可发生在任何年龄,多见于青壮年。

性别无差异。

【病因与发病机制】多数学者认为UC与克罗恩病实际上是同一疾病的不同亚型,均属肠道免疫炎症性疾病。

组织损伤的基本病理过程相似,但可能病因不同,发病过程的具体环节不同。

UC病因及发病机制至今尚未明确,一般认为与下列因素综合作用有关。

1.免疫因素一般认为本病是因为某些促发因素作用于易感者,激发肠粘膜亢进而引起的免疫炎症反应。

参与的细胞有中性粒细胞、巨嗜细胞、肥大细胞、T淋巴细胞和B淋巴细胞、自然杀伤细胞等,这些效应细胞释放大量抗体、细胞因子及炎症介质可引起组织破坏好炎性病变。

其中,在疾病炎症过程中大量氧自由基的形成在肠粘膜的损害中起着重要作用。

2.遗传因素本病发病率在种族间有明显差异,白种人发病率高,发病有家庭聚集倾向,单卵双胎看同时发病。

3.感染因素因本病的病理变化、临床表现与细菌性痢疾非常相似,在某些患者的粪便中可以培养出细菌,且部分患者使用抗生素有效,因而认为感染是本病的病因,但至今未找到某一种特异微生物病原与本病有恒定的关系,认为病原微生物乃至食物抗原可能是本病的非特异性促发因素。

4.精神因素与精神障碍相关的自主神经功能失调可引发消化道运动功能亢进、平滑肌痉挛、血管收缩、组织缺氧、毛细血管通透性增高等病理改变,最终导致肠壁炎症及溃疡形成。

临床上可见本病因紧张、劳累而诱发或加重,且患者常有精神紧张和焦虑表现。

精神因素可诱使本病发作,也可使本病反复发作的继发表现。

5.过敏反应食物过敏可引起结、直肠炎,约2/3 UC患者病情反复或加重与饮食不当有关。

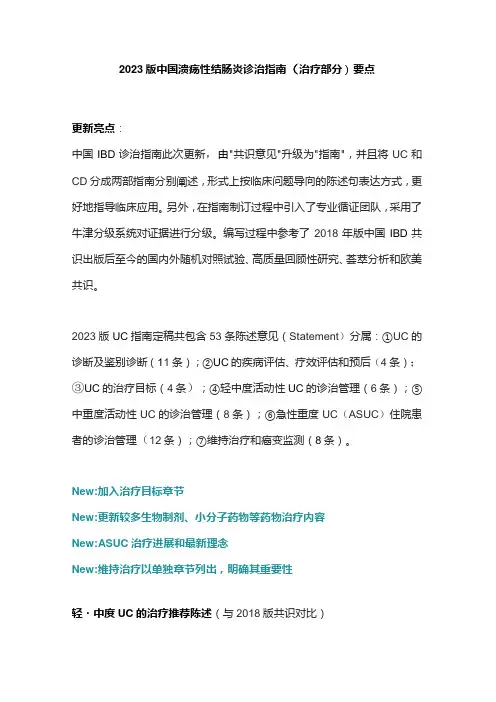

2023版中国溃疡性结肠炎诊治指南(治疗部分)要点更新亮点:中国IBD诊治指南此次更新,由"共识意见"升级为"指南",并且将UC和CD分成两部指南分别阐述,形式上按临床问题导向的陈述句表达方式,更好地指导临床应用。

另外,在指南制订过程中引入了专业循证团队,采用了牛津分级系统对证据进行分级。

编写过程中参考了2018年版中国IBD共识出版后至今的国内外随机对照试验、高质量回顾性研究、荟萃分析和欧美共识。

2023版UC指南定稿共包含53条陈述意见(Statement)分属:①UC的诊断及鉴别诊断(11条);②UC的疾病评估、疗效评估和预后(4条);③UC的治疗目标(4条);④轻中度活动性UC的诊治管理(6条);⑤中重度活动性UC的诊治管理(8条);⑥急性重度UC(ASUC)住院患者的诊治管理(12条);⑦维持治疗和癌变监测(8条)。

New:加入治疗目标章节New:更新较多生物制剂、小分子药物等药物治疗内容New:ASUC治疗进展和最新理念New:维持治疗以单独章节列出,明确其重要性轻・中度UC的治疗推荐陈述(与2018版共识对比)1.对于轻度(初治)活动性UC,建氨基水杨酸(5-ASA)制剂是治疗议口服5-ASA(2-4g/d)诱导缓轻度UC的主要药物,包括传统的解,疗效与剂量成正比关系。

顿服柳氮磺毗嚏(SASP)和其他不同类5-ASA与分次服用疗效相同。

(证型的5-ASA制剂。

SASP疗效与其据等级1,强推荐)他5-ASA制剂相似,但不良反应远较5-ASA制剂多见。

目前尚缺乏证据显示不同类型5-ASA制剂的疗效有差异。

每天1次顿服美沙拉嗪与分次服用等效。

5-ASA推荐剂量为2-4g/d,分次口服或顿服。

解读:5-ASA推荐剂量与剂型与2018版保持不变。

2.轻度活动性溃疡性直肠炎建议应用5-ASA直肠给药诱导缓解。

(证据等级1,强推荐)。

3.对于轻-中度左半结肠型活动性对病变局限在直肠或直肠乙状结肠者,强调局部用药(病变局限在直肠用栓剂,局限在直肠乙状结肠用灌肠剂),口服与局部用药联合应用疗效更佳。

溃疡性结肠炎:一、定义:溃疡性结肠炎是一种非特异性的炎症,炎症累及粘膜层和粘膜下层,对于破坏性很严重,此炎症与感染无关,与免疫有关,但是偶尔也会有感染的出现,典型症状为腹疼腹泻伴粘膜脓血便,此外还会有其他的肠道外症状,关节炎。

二、病理变化:病变的发生就会形成隐窝脓肿,随着病变的进展,隐窝脓肿发生联合或覆盖,逐渐的形成溃疡,相对正常的黏膜会出现水肿,成为自肉样外貌,在相邻的溃疡间变得独立。

而溃疡区则被胶原和肉芽组织等占领,并深入溃疡。

三、病因:1、感染因素:该病患者的免疫异常日益受到重视,多数学者认为,该病是一种自身免疫性疾病,但是该病发病机制中的意义还没有最后定论‘2.氧自由基破坏:该病过程中肠道内压会增高,会导致肠道的血流降低,引起供氧还原的不完全,从而形成大量的氧自由基,损伤肠道黏膜;3、遗传因素:该病的发病有一定的家族差异性,这也反映出该病与遗传因素有关;4、精神因素:患者的精神长期处于紧张焦虑、压力过大等不良的状态下容易引发疾病;四、临床表现:(一)消化系统的症状:1、腹泻:腹泻的程度轻重不一,轻者3-4天火腹泻于便秘交替出现;重者每日排便次数可多至30余次,粪质多糊状及吸水状,混有粘液、脓血。

2、腹疼:腹痛的性质常为痉挛性,有疼痛—便意—便后缓解的规律,常伴有腹胀。

腹痛的特点是:疼痛—便意—便后疼痛缓解。

3、便血:大便带脓血和粘液,不成形,可呈浆糊状软便,严重者可见鲜红色大量的血和血凝块,大量的便血易引发感染和贫血症状。

4、肠道外症状:常有结节性红斑、关节炎、颜色素葡萄膜炎、口腔黏膜溃疡、慢性活动性肝炎、溶血性贫血等免疫状态异常之改变。

(二)全身症状:急性期或爆发型的患者常有低热或中度发热的情况,严重的患者可出现高热和心动过速的现象。

病程中患者有消瘦、水电解质失衡等的表现。

(三)肠道外症状:患者常出现眼部色素、溃疡、慢性活动性肝炎、溶血性贫血等免疫系统异常的表现。

五、临床的分类:1、轻型2、重型3、爆发型六、并发症:1、休克:便血是本病的主要临床表现之一,大量便血会引起贫血和低血容量休克,危急生命。

最新指南中溃疡性结肠炎的定义

溃疡性结肠炎(Ulcerative Colitis, UC)是一种慢性非特异性炎症性肠病,主要累及结肠和直肠的黏膜层。

根据最新的指南,溃疡性结肠炎被定义为:

1. 病理学特征:结肠和直肠黏膜存在持续或反复的炎症,表现为溃疡、糜烂、渗出和结肠黏膜脓肿等。

炎症始终累及直肠,并可延伸至近端结肠或整个结肠。

2. 临床表现:主要症状包括腹痛、腹泻(常伴有痢疾样排便)、黏液脓血便、体重减轻和全身症状(如发热、乏力等)。

症状的严重程度因病情活动期和缓解期而有所不同。

3. 影像学和内镜表现:影像学检查(如CT或MRI)可显示结肠壁增厚、周围脂肪浸润等炎症表现。

内镜检查是确诊的关键,可见连续性的黏膜炎症、溃疡、糜烂等病变。

4. 排除其他原因:需要排除感染性肠炎、缺血性结肠炎、放射性结肠炎等其他可能导致类似症状的疾病。

溃疡性结肠炎是一种复杂的疾病,需要全面评估临床症状、内镜及组织病理学表现,以及影像学检查结果,并结合实验室检查结果进行综合诊断。

及时确诊和适当治疗对于控制病情、改善预后至关重要。

溃疡性结肠炎治疗药物研发的指导原则Development of new medicinal products for the treatmentof ulcerative colitis2008年1月 欧洲EMEA发布2010年3月 药审中心组织翻译博福-益普生(天津)制药有限公司翻译药审中心最终核准目录概述 (3)1. 前言(背景) (3)2. 适用范围 (3)3. 法律依据 (4)4. 指南正文 (5)4.1 患者的特征及选择 (5)4.2 疗效评估的方法 (6)4.3 临床试验的实施策略和试验设计 (7)4.4特殊人群中的研究 (12)4.5 临床安全性评价 (14)定义 (14)溃疡性结肠炎治疗药物研发的指导原则概述这一关于溃疡性结肠炎治疗新药的研发指南(CHMP/EWP/18463/2006),旨在为这类疾病治疗新药的评价提供指导。

本指南阐明了对用于支持药品上市许可的临床资料的要求,其中特别提到了临床研究中的患者选择,推荐的疗效评估方法,临床试验的策略和试验设计,药品研发的安全性和全局考量。

1.前言(背景)溃疡性结肠炎(UC)是一种长期,反复发作,影响结肠部位的炎性肠病。

该病的发病率预计为70-150例/100 000,发病年龄集中在15到25岁之间。

有15%的溃疡性结肠炎患者为儿童,并且可能于学龄前出现。

该疾病通常累及直肠,且可能累及临近的部分乃至整个结肠。

约40-50%患者的病变部位仅限于直肠和直肠乙状结肠,30%-40%的患者蔓延至乙状结肠曲,但未累及全结肠,而有20%患者罹患全结肠炎。

轻度至中度UC的治疗主要依靠柳氮磺胺吡啶和5-氨基水杨酸(5-ASA)。

这类药物制剂对于诱导和维持溃疡性结肠炎的缓解是有效的。

大多数中度至重度的活动性溃疡性结肠炎患者可以从局部、口服或静脉的皮质类固醇激素治疗中获益。

然而,缓解期的疾病不能采用类固醇药物进行维持治疗。

对于无法停用皮质类固醇药物的患者,硫唑嘌呤(AZA)或6-巯基嘌呤(6-MP)已被作为减少皮质类固醇使用的药物制剂使用。

奥沙拉嗪治疗溃疡性结肠炎的疗效观察

魏月兰

【期刊名称】《临床合理用药杂志》

【年(卷),期】2010(3)19

【摘要】目的观察奥沙拉嗪治疗溃疡性结肠炎(UC)的临床疗效。

方法 45例患者随机分为治疗组23例和对照组22例。

治疗组给予奥沙拉嗪1g,口服,每天3次;对照组给予柳氮磺胺吡啶4g,分4次口服。

2组疗程均为8周。

观察2组临床疗效和不良反应发生情况。

结果治疗组总有效率为82.6%,对照组为86.4%,差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。

治疗组发生不良反应2例,对照组发生5例。

结论奥沙拉嗪治疗UC安全有效,值得临床推广应用。

【总页数】1页(P53-53)

【关键词】奥沙拉嗪;结肠炎,溃疡性;疗效

【作者】魏月兰

【作者单位】山东省郓城县医疗保险门诊部

【正文语种】中文

【中图分类】R574.62

【相关文献】

1.奥沙拉嗪和柳氮磺胺吡啶治疗溃疡性结肠炎的疗效和不良反应观察 [J], 李湛

2.奥沙拉嗪联合糖皮质激素及奥曲肽治疗中-重度溃疡性结肠炎疗效观察 [J], 张军华

3.艾迪莎联合奥沙拉嗪治疗溃疡性结肠炎的临床疗效观察 [J], 王新红;于夕玲

4.奥沙拉嗪治疗溃疡性结肠炎189例疗效观察 [J], 刘智慧

5.奥沙拉嗪和柳氮磺胺吡啶治疗溃疡性结肠炎的疗效和不良反应观察 [J], 李湛因版权原因,仅展示原文概要,查看原文内容请购买。

SPECIAL ARTICLEEuropean evidence-based Consensus on the management of ulcerative colitis:Special situationsLivia Biancone,Pierre Michetti,Simon Travis ⁎,1,Johanna C.Escher,Gabriele Moser,Alastair Forbes,Jörg C Hoffmann,Axel Dignass,Paolo Gionchetti,Günter Jantschek,Ralf Kiesslich,Sanja Kolacek,Rod Mitchell,Julian Panes,Johan Soderholm,Boris Vucelic,Eduard Stange ⁎,1for the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO)Received 30December 2007;accepted 30December 2007KEYWORDSUlcerative colitis;Pouchitis;Colorectal cancer surveillance;Adolescence;PsychosomaticContents 8.Pouchitis ............................................................658.1.General.........................................................658.1.1.Symptoms ..................................................658.1.2.Endoscopy (‘pouchoscopy ’)........................................658.1.3.Histopathology of pouchitis ........................................668.1.4.Differential diagnosis ............................................668.1.5.Risk factors for pouchitis and pouch dysfunction............................668.2.Pattern of pouchitis..................................................668.2.1.Acute and chronic pouchitis ........................................668.2.2.Scoring of pouchitis.............................................668.2.3.Recurrent pouchitis and complications ...... (67)⁎Corresponding authors.Travis is to be contacted at John Radcliffe Hospital,Oxford,OX39DU,UK.Tel.:+441865228753;fax:+441865228763.Stange,Department of Internal Medicine 1,Robert Bosch Krankenhaus,PO Box 501120,Auerbachstr ,110,70341Stuttgart,Germany.Tel.:+4971181013404;fax:+4971181013793.E-mail addresses:simon.travis@ (S.Travis),Eduard.Stange@rbk.de (E.Stange).1These authors acted as convenors of the Consensus and contributed equally to thework.1873-9946/$-see front matter ©2008European Crohn T s and Colitis Organisation.Published by Elsevier B.V .All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2007.12.001a v a i l ab l e a t w w w.sc i e n c ed i re c t.c o mJournal of Crohn's and Colitis (2008)2,63–9264L.Biancone et al.8.3.Medical treatment (67)8.3.1.Acute pouchitis:antibiotics (67)8.3.2.Chronic pouchitis:combination antibiotic therapy or budesonide (67)8.3.3.Acute and chronic refractory pouchitis:other agents (67)8.3.4.Maintenance of remission:probiotics (68)8.3.5.Prevention of pouchitis:probiotics (68)8.4.Cuffitis (68)9.Surveillance for colorectal cancer (68)9.1.Risk of cancer (68)9.1.1.Estimation of risk (68)9.1.2.Risk factors for cancer development (69)9.2.Surveillance colonoscopy programmes (69)9.2.1.Screening and surveillance (69)9.2.2.Effectiveness (69)9.2.3.Initial screening colonoscopy (70)9.2.4.Surveillance schedules (70)9.3.Colonoscopic procedures (70)9.3.1.Number and site of biopsies (70)9.3.2.Chromoendoscopy (71)9.4.Dysplasia (71)9.4.1.Risk of progression to cancer (71)9.4.2.Dysplasia and colectomy (71)9.4.3.Dysplasia and raised lesions (71)9.5.Chemoprevention (72)9.6.Prognosis (72)10.Children and adolescents (72)10.1.Introduction (72)10.2.Diagnosis (73)10.2.1.Diagnostic threshold (73)10.2.2.Documentation (73)10.2.3.Diagnostic procedures (73)10.3.Induction therapy in children (73)10.3.1.Distal colitis (73)10.3.2.Extensive colitis (74)10.3.3.Severe colitis (74)10.4.Maintenance therapy in children (75)10.4.1.Aminosalicylates (75)10.4.2.Thiopurines (75)10.5.Surgery in children (75)10.5.1.Indications (75)10.5.2.Procedures (75)10.6.Nutritional support (75)10.7.Psychosocial support (75)10.8.Transition of care to adult services (76)11.Pregnancy (76)12.Psychosomatics (76)12.1.Introduction (76)12.2.Influence of psychological factors on disease (76)12.2.1.Aetiology (76)12.2.2.Pattern of disease (76)12.3.Psychological disturbances in ulcerative colitis (76)12.4.Approach to psychological disorders (77)munication with patients (77)12.4.2.Psychological support (77)12.4.3.Therapeutic intervention (77)12.4.4.Therapeutic choice (78)13.Extraintestinal manifestations (78)13.1.Introduction (78)13.2.Arthropathies (78)13.2.1.Pauciarticular peripheral arthropathy (78)13.2.2.Polyarticular peripheral arthropathy (79)13.2.3.Axial arthropathy (79)13.2.4.Therapy of arthropathies (79)13.3.Cutaneous manifestations (79)13.3.1.Erythema nodosum (79)13.3.2.Pyoderma gangrenosum(PG) (80)13.3.3.Sweet's syndrome (80)13.4.Ocular manifestations (80)13.4.1.Episcleritis (80)13.4.2.Uveitis (80)13.4.3.Cataracts (80)13.5.Hepatobiliary disease (80)13.5.1.Primary sclerosing cholangitis (81)13.6.Metabolic bone disease (81)13.6.1.Diagnosis and fracture risk (81)13.6.2.Management (81)13.7.Other systems (82)anisation of services for EIMs associated with ulcerative colitis (82)plementary and alternative medicines (82)14.1.Introduction (82)14.2.Definitions (82)e of CAM (82)Contributors (83)Acknowledgements (83)References (84)8.Pouchitis8.1.GeneralProctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis(IPAA) is the procedure of choice for most patients with ulcerative colitis(UC)requiring colectomy.1Pouchitis is a non-specific inflammation of the ileal reservoir and the most common complication of IPAA in patients with UC.2–7Its frequency is related to the duration of the follow-up,occurring in up to 50%of patients10years after IPAA in large series from major referral centres.1–9The cumulative incidence of pouchitis in patients with an IPAA for familial adenomatous polyposis is much lower,ranging from0to10%.10–12 Reasons for the higher frequency of pouchitis in UC remain unknown.Whether the pouchitis more commonly develops within the first years after IPAA or whether the risk continues to increase with longer follow-up remains undefined.8.1.1.SymptomsAfter total proctocolectomy with IPAA,median stool frequency is4to8bowel movements1–4,13,14with700mL of semiformed/liquid stool per day2,13,14.Symptoms related to pouchitis include increased stool frequency and liquidity, abdominal cramping,urgency,tenesmus and pelvic dis-comfort(2,15).Rectal bleeding,fever,or extraintestinal manifestations may occur.Rectal bleeding is more often related to inflammation of the rectal cuff(“cuffitis”),16 than to pouchitis.Poor faecal incontinence may occur in the absence of pouchitis after IPAA,but is more common in patients with pouchitis.Symptoms of pouch dysfunction in patients with IPAA may be caused by conditions other than pouchitis,including Crohn's disease of the pouch,17–19 cuffitis,16and an irritable pouch.20This is why the diagnosis depends on endoscopy and biopsy in conjunction with symptoms.8.1.2.Endoscopy(‘pouchoscopy’)Pouchoscopy and pouch mucosal biopsy should be per-formed in patients with symptoms compatible with pouchitis,in order to confirm the diagnosis.15Patients with an ileoanal pouch occasionally have a stricture at the pouch-anal anastomosis,so a gastroscope rather than a colonoscope may better be necessary for pouchoscopy. Endoscopic findings compatible with pouchitis include diffuse erythema caused by inflammation of the ileal pouch,which may be patchy,unlike that observed in UC. Characteristic endoscopic findings include oedema,gran-ularity,friability,spontaneous or contact bleeding,loss of vascular pattern,mucous exudates,haemorrhage,erosions and ulceration.17Erosions and/or ulcers along the staple line do not necessarily indicate pouchitis.Characteristi-cally,these findings are non-specific and lesions may be discontinuous,unlike the colorectal lesions in UC.18,21,22 Biopsies should be taken from the pouch mucosa and from the afferent limb above the pouch,but not along the staple line.ECCO Statement8AThe diagnosis of pouchitis requires the presence of symptoms,together with characteristic endoscopic and histological abnormalities[EL3a,RGB].Extensive colitis, extraintestinal manifestations(eg primary sclerosing cho-langitis),being a non-smoker,p-ANCA positive serology,and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use are possible risk factors for pouchitis[EL3b,RG D]65ECCO Consensus on UC:Special situations8.1.3.Histopathology of pouchitisHistological findings of pouchitis are also non-specific, including acute inflammation with polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration,crypt abscesses and ulceration,in association with a chronic inflammatory infiltrate.21,22 There may be discrepancy between endoscopic and histologic findings in pouchitis,possibly related to sam-pling error.23,24Morphological changes of the epithelium lining the ileal pouch normally develop in the12–18months after ileostomy closure,characterised by flattening and a reduced number,or disappearance of the villi,leading to villous atrophy(“colonic metaplasia”).22–24Although the aetiology of pouchitis remains unknown,it can be inferred from the predeliction for patients with UC and the response to antibiotic therapy that the bacterial flora and whatever predisposes to UC itself are involved in the pathogenesis of tissue damage in the ileoanal pouch.25,26 Pouchitis tends to occur only after colonic metaplasia has developed in the pouch,although a causal association is unproven.8.1.4.Differential diagnosisThe clinical history and biopsies help discriminate between pouchitis,ischaemia,Crohn's disease(CD)and other rare forms of pouch dysfunction such as collagenous pouchitis, Clostridium difficile or cytomegalovirus pouchitis.27–29 Secondary pouchitis,caused by pelvic sepsis,usually causes focal inflammation and should be considered.Biopsies taken from the ileum above the pouch may reveal pre-pouch ileitis as a cause of pouch dysfunction,although this usually causes visible ulceration that may be confused with Crohn's disease.30The possibility of non-specific ileitis caused by NSAIDs should be considered.318.1.5.Risk factors for pouchitis and pouch dysfunction Reported risk factors for pouchitis include extensive UC,1,32 backwash ileitis,32extraintestinal manifestations(especially primary sclerosing cholangitis),5,19,33being a non-smoker34 and regular use of NSAIDs.31,35Interleukin-1receptor antago-nist gene polymorphisms36and the presence of perinuclear neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies37are also associated with pouchitis.Not surprisingly studies are discordant with regard to the role of each risk factor.Some of the best data on risk factors come from the Cleveland Clinic.38240consecutive patients were classified as having healthy pouches(n=49), pouchitis(n=61),Crohn's disease(n=39),cuffitis(n=41),or irritable pouch syndrome(n=50).The risk of developing pouchitis was increased3–5fold when the indication for IP AA was dysplasia(OR3.89;95%CI1.69–8.98),or when the patient had never smoked(OR5.09;95%CI1.01–25.69),or used NSAIDs(OR3.24;95%CI1.71–6.13),or(perhaps surprisingly) had never used anxiolytics(OR5.19;95%CI1.45–18.59).The risk of turning out to have Crohn's disease of the pouch was greatly increased by being a current smoker(OR4.77;95%CI,1.39–16–25),and modestly associated by having a pouch of long duration(OR 1.20;95%CI 1.12.–1.30).Cuffitis was associated with symptoms of arthralgia(OR4.13;95%CI1.91–8.94)and a younger age(OR1.16;95%CI1.01–1.33).Irritable pouch syndrome is probably under-recognised,although is a common cause of pouch dysfunction when other causes (including a small volume pouch,incomplete evacuation and pouch volvulus)have been excluded and investigations are normal.The principal risk factor is the use of antidepressants (OR4.17;95%CI1.95–8.92)or anxiolytics(OR3.21;95%CI 1.34–7.47),which suggests that these people may have had irritable bowel syndrome contributing to symptoms of colitis before pouch surgery.38These risk factors should not preclude proctocolectomy if surgery is appropriate,but should inform pre-operative discussions with the patient and family.In particular the possibility that IBS may be contributing to symptoms of refractory UC should be considered and objective evidence of treatment refractory colitis obtained before surgery.If there is a disparity between preoperative and endoscopic appearance,or if the patient is on antidepressants,then the risk of pouch dysfunction after IPAA needs particularly careful consideration.Similarly,if a patient has primary sclerosing cholangitis,then it is appropriate to discuss the higher risk of pouchitis.This is appropriate management of expectations rather than a contraindication to appropriate surgery.8.2.Pattern of pouchitis8.2.1.Acute and chronic pouchitisOn the basis of symptoms and endoscopy,pouchitis can be divided into remission(normal pouch frequency)or active pouchitis(increased frequency with endoscopic appear-ances and histology consistent with pouchitis).15,39Active pouchitis may then be divided into acute or chronic, depending on the symptom duration.The threshold for chronicity is a symptom duration of N4weeks.Up to10%of patients develop chronic pouchitis requiring long-term treatment,and a small subgroup has pouchitis refractory to medical treatment.38.2.2.Scoring of pouchitisThe Pouchitis Disease Activity Index(PDAI)has been developed to standardize diagnostic criteria and assess the severity of pouchitis.15,39,40The PDAI is a composite score that evaluates symptoms,endoscopy and histology.Each component score has a maximum of6points.Patients with a total PDAI score≥7are classified as having pouchitis,so a patient has to have both symptoms and endoscopic or histological evidence of pouchitis and,ideally,all three. The problem is that about a quarter of patients with a high symptom score suggestive of pouchitis may not fulfil criteria for the diagnosis of pouchitis,as assessed by the PDAI,since endoscopic or histological criteria may be absent.Conse-quently a relatively large number of patients may be unnecessarily treated for puchitis when symptoms are due to other conditions.Other scoring systems have been devised,including that by Moskowitz21and an index from parisons with the PDAI41,42show that they are not interchangeable,but this affects clinical trials rather than clinical practice.ECCO Statement8BThe most frequent symptoms of pouchitis are increasednumber of liquid stools,urgency,abdominal crampingand pelvic discomfort.Fever and bleeding are rare[EL1c,RG B].Routine pouchoscopy after clinical remission is notrequired[EL5,RG D]66L.Biancone et al.8.2.3.Recurrent pouchitis and complicationsPouchitis recurs in more than50%.3,15,39Patients with recurrent pouchitis can broadly be grouped into three categories:infrequent episodes(b1/yr),a relapsing course (1–3episodes/yr)or a continuous course.Pouchitis may further be termed treatment responsive or refractory,based on response to single-antibiotic therapy(see8.3.2).7,9 Although these distinctions are largely arbitrary,they help both patients and their physicians when considering manage-ment options to alter the pattern of plications of pouchitis include abscesses,fistulae,stenosis of the pouch-anal anastomosis and adenocarcinoma of the pouch.7,27,39This latter complication is exceptional and almost only occurs when there is pre-exiting dysplasia or carcinoma in the original colectomy specimen.8.3.Medical treatment8.3.1.Acute pouchitis:antibioticsTreatment of pouchitis is largely empirical and only small placebo-controlled trials have been conducted.Antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment,and metronidazole and ciproflox-acin are the most common initial approaches,often with a rapid response.The odds ratio of inducing a response using oral metronidazole compared with placebo in active chronic pouchitis was26.67(95%CI 2.31–308.01,NNT=2).43The randomised trials of both metronidazole and ciprofloxacin are, however,small.44–46The two have been compared in another small randomised trial.47Seven patients received ciproflox-acin1g/day and nine patients metronidazole20mg/kg/day for a period of2weeks.Ciprofloxacin lowered the PDAI score from10.1±2.3to3.3±1.7(p=0.0001),whereas metronidazole reduced the PDAI score from9.7±2.3to5.8±1.7(p=0.0002). There was a significantly greater reduction in the ciprofloxacin compared to metronidazole in terms of the total PDAI (p=0.002),symptom score(p=0.03)and endoscopic score (p=0.03),as well as fewer adverse events(33%of metronida-zole-treated patients reported side-effects,but none on ciprofloxacin).Combination antibiotic therapy is an option for persistent symptoms(below).8.3.2.Chronic pouchitis:combination antibiotic therapy or budesonideFor patients who have persistent symptoms,alternative diagnoses should be considered,including undiagnosed Crohn's disease,pouch-anal or ileal-pouch stricture,infec-tion with CMV or Cl difficile,collagenous pouchitis,cuffitis, anatomical disorders,or irritable pouch syndrome.Approxi-mately10–15%of patients with acute pouchitis develop chronic pouchitis,which may be“treatment responsive”or “treatment refractory”to single-antibiotic therapy.39 Patients with chronic,refractory pouchitis do not respond to conventional therapy and often continue to suffer symptoms,which is a common cause of pouch failure. Combination antibiotic therapy or oral budesonide may work.16consecutive patients with chronic,refractory pouchitis(disease N4weeks and failure to respond to N4weeks of single-antibiotic therapy)were treated with ciprofloxacin1g/day and tinidazole15mg/kg/day for 4weeks.47A historic cohort of ten consecutive patients with chronic refractory pouchitis treated with5–8g oral and topical mesalazine daily was used as a comparator.These refractory patients had a significant reduction in the total PDAI score and a significant improvement in quality-of-life score(p b0.002) when taking ciprofloxacin and tinidazole,compared to base-line.The rate of clinical remission in the antibiotic group was 87.5%and for the mesalazine group was50%.In another study,18patients non-responders to metroni-dazole,ciprofloxacin or amoxycillin/clavulanic acid for 4weeks were treated orally with rifaximin2g/day(a nonabsorbable,broad spectrum antibiotic)and ciprofloxacin 1g/day for15days.Sixteen out of18patients(88.8%)either improved(n=10)or went into remission(n=6).48Median PDAI scores before and after therapy were11(range9–17) and4(range0–16),respectively(p b0.002).A British group observed similar benefit in just8patients.49In another combination study,44patients with refractory pouchitis received metronidazole800mg–1g/day and ciprofloxacin 1g/day for28days.5036patients(82%)went into remission and median PDAI scores before and after therapy were12and 3respectively(p b0.0001).The alternative is oral budeso-nide CIR9mg daily for8weeks,which achieved remission in 15/20(75%)patients not responding after1month of ciprofloxacin or metronidazole.51The message is simple enough,even if the trials are underpowered:if ciprofloxacin does not work,then try it in combination with an imidazole antibiotic or rifaximin,or try oral budesonide.8.3.3.Acute and chronic refractory pouchitis:other agentsThe variety of approaches illustrates the challenges of trying to find treatment that works for a new disorder.These are largely of historic interest.Budesonide enemas were as effective as metronidazole for acute pouchitis in a rando-mised controlled trial.52Ciclosporin enemas were successful for chronic pouchitis in a pilot study53and oral azathioprine may help if patients relapse become budesonide-dependent. Uncontrolled studies of short-chain fatty acid enemas54,55 showed little value.Glutamine and butyrate suppositories have been compared for chronic pouchitis.56Of more recent interest,infliximab has been tried in patients with chronic, (very)refractory pouchitis not responding either to metro-nidazole or ciprofloxacin1g/day for4weeks or oral budesonide CIR9mg/day for8weeks.10/12(83.3%)such patients treated with infliximab5mg/kg at0,2and6weeks went into remission.57The median PDAI score before therapy was13(range8–18)and2(range0–9)after infliximab (p b0.001)and the IBDQ also significantly improved from96ECCO Statement8CThe majority of patients respond to metronidazole or ciprofloxacin,although the optimum modality of treat-ment is not clearly defined[EL1b,RG B].Side-effects are less frequent using ciprofloxacin[EL1c,RG B].Antidiar-rhoeal drugs may reduce the number of daily liquid stools in patients,independent of pouchitis[EL5,RGD]ECCO Statement8DIn chronic pouchitis,combined antibiotic treatment is effective[EL1b,RG B]67ECCO Consensus on UC:Special situations(range 74–184) to 196 (92–230) ( p b 0.001). 57 Infliximab has been used when the cause of pouch dysfunction is Crohn's disease, or fistulation.58 Benefit been also been reported from alicaforsen enemas(an inhibitor of intercellular adhesion molecule(ICAM)-1)in an open-label trial.598.3.4.Maintenance of remission:probioticsIn chronic pouchitis,once remission has been obtained, treatment with the highly concentrated probiotic mixture VSL#3is able to maintain remission.T wo double-blind, placebo-controlled studies have shown the efficacy of VSL#3(450billion bacteria of8different strains/g)to maintain remission in patients with chronic pouchitis.In the first study,40patients who achieved clinical and endo-scopic remission after one month of combined antibiotic treatment(rifaximin2g/day+ciprofloxacin1g/day),were randomised to receive either VSL#3,6g/day(18×1011 bac t eri a/ d ay), or placebo for 9 mo n ths.60 All 20 patient s who received placebo relapsed,while17of the20patients (85%)treated with VSL#3remained in clinical and endo-scopic remission at the end of the study.Interestingly,all17 patients relapsed within four months after stopping VSL#3.60In the second study,36patients with chronic, refractory pouchitis who achieved remission(PDAI=0) after1month of combined antibiotic treatment(metroni-dazole+ciprofloxacin)received6g/once a day of VSL#3or placebo for1year.Remission rates at one year were85%in the VSL#3group and6%in the placebo group(p b0.001).61 8.3.5.Prevention of pouchitis:probioticsThe same probiotic preparation(VSL#3)has been shown to prevent pouchitis within the first year after surgery,in a randomised,double-blind,placebo-controlled study.Forty consecutive patients undergoing IPAA for UC were rando-mised within a week after ileostomy closure,to VSL#33g (9 × 10 11 ) per day or placebo for 12 months. Patients were assessed clinically, endoscopically and histologically at 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Patients treated with VSL#3 had a si g ni f i c an t ly l o wer i n c i de n c e o f a c u t e pou c hi t i s ( 10 %) compared with those treated with placebo (40%) ( p b 0.05), and experienced a significant improvement of quality of life.62The mechanism by which therapy with probiotics works remains elusive,but has been investigated.63Mucosa-associated pouch microbiota before and after therapy with VSL#3shows that patients who develop pouchitis while treated with placebo have low bacterial and high fungal diversity.Bacterial diversity was increased and fungal diversity was reduced in patients in remission maintained with VSL#3(p=0.001).Real time PCR experiments demon-strated that VSL#3increased the total number of bacterial cells(p=0.002)and modified the spectrum of bacteria towards anaerobic species.Taxa-specific clone libraries showed that the spectrum of Lactobacillus sp.and Bifido-bacter sp.was altered on probiotic therapy.The diversity of the fungal flora was repressed.Restoration of the integrity of a“protective”intestinal mucosa related microbiota could therefore be a potential mechanism of probiotic bacteria in inflammatory barrier diseases of the lower gastrointestinal tract.8.4.CuffitisCuffitis,especially after double-stapled IPAA(see Section 7,preceding paper same issue)can cause pouch dysfunction with symptoms that mimic pouchitis or irritable pouch syndrome(IPS).Unlike IPS(which may coexist)bleeding is a characteristic feature of cuffitis.Endoscopy by an informed endoscopist is diagnostic,but care has to be taken to examine the cuff of columnar epithelium between the dentate line and pouch-anal anastomosis(Section7.2.3, preceding paper same issue).64In an open-label trial,14 consecutive patients with cuffitis were treated with mesa-lamine suppositories500mg twice daily.16Mesalazine suppositories significantly reduced the total Cuffitis Activity Index(derived from the PDAI)from11.9±3.17to6.21±3.19 (p b0.001).Symptom subscore(from 3.24±1.28to 1.79±1.31),endoscopy subscore(from3.14±1.29to1.00±1.52) and histology subscore(4.93±1.77to3.57±1.39)were all significantly reduced.92%of patients with bloody bowel movements and70%with arthralgia(a characteristic clinical feature of cuffitis,Section8.1.5)improved on therapy.No systemic or topical adverse effects were reported.9.Surveillance for colorectal cancer9.1.Risk of cancer9.1.1.Estimation of riskPatients with long standing UC have a higher risk of developing colorectal carcinoma(CRC)than the average population.The magnitude of this risk,however,is still the subject of a debate.Indeed,while older reports included in two meta-analyses65,66confirmed a rapid increase of the risk after ten years of disease,the magnitude of the risk in recent population-based studies appears much smaller.67,68In fact, although Eaden and colleagues computed a cumulative CRC risk of18%in UC patients after30years of disease,risks of only7.5%and2.1%respectively were observed in two studies published since2004.67,68Furthermore,in the largest report of surveillance colonoscopy in at-risk population of patients with extensive UC to date(600patients over a30year period),the cumulative incidence of CRC by colitis durationECCO Statement8EVSL#3 (18 × 10 11 of 8 bacterial strains for 9 or 12 months) has shown efficacy for maintaining antibiotic-induced remission [EL1b, RG B]. VSL#3 (9 ×1011 bacteria) has also shown efficacy for preventing pouchitis [EL2b, RG C]ECCO Statement8ERectal cuff inflammation(cuffitis)may induce symptoms similar to pouchitis or irritable pouch syndrome,although bleeding is more frequent[EL2a,RG B].T opical5-ASA has shown efficacy[EL4,RGD]ECCO Statement9APatients with longstanding ulcerative colitis appear to have an increased risk of colorectal cancer(CRC)as compared to the general population[EL2]68L.Biancone et al.was 2.5%at20years,7.6%at30years,and10.8%at 40years.69In this study from St Mark's,only30/600patients (5%)developed CRC.The reasons for such an improvement in the risk of CRC are still unclear but may include improved control of mucosal inflammation,more extensive use of5-ASA compounds,the implementation of surveillance pro-grammes and timely colectomy.70Taken together these studies suggest that the CRC risk in UC patients should be kept under scrutiny.Nevertheless,the best evidence,as provided by concordant meta-analyses,indicates that the risk of CRC development is increased in UC[EL2].The ECCO Consensus working party,through their answers to ques-tionnaires,supported this evaluation of the data.9.1.2.Risk factors for cancer developmentSeveral independent factors affect the magnitude of the risk of malignant transformation.The duration of disease and extent of mucosal inflammation are the most prominent. There is no uniform definition of the duration of disease, although onset of symptoms has generally been used in the studies that have identified this parameter as a risk factor.In a review of19practice and population-based studies,Eaden confirmed that the CRC risk appears to increase8–10years after the onset of UC related symptoms65and subsequently increases in later decades of the disease[EL2].The extent of mucosal inflammation(including backwash ileitis)has been correlated with the risk of CRC in several studies,as well as in a systematic review[EL2].66,67,71–75 Other factors have also been associated with a high CRC risk in all or part of these studies.These include young age at onset of the disease(less than20years of age at the time of diagnosis)65and an association with primary sclerosing cholangitis(PSC)[EL2].76However,there was no difference in median age at onset of colitis for those with or without CRC in the600-patient study from St Mark's(p=0.8,Mann–Whitney)years.69The persistence of mucosal inflamma-tion72,73or a family history of CRC77may also contribute to an increased risk,but the association has been less consistent across the studies[EL3].In a nested case-control study from two well-defined,population-based IBD cohorts(Copenhagen County,Denmark and Olmsted County,Minnesota)43cases of IBD-associated CRC were matched on six criteria to1–3 controls(n=102).Significant associations were found between PSC(OR6.9,95%CI1.2–40.0),the percentage of time with clinically active disease(OR per5%increase1.2,95%CI1.0–1.4),and≥12months of continuous symptoms(OR 3.295%CI1.2–8.6).78The presence of pseudopolyps,which can be considered a marker of severity of inflammation,have been associated with double the risk of CRC(OR2.5;95%CI: 1.4–4.6),73,79which is a useful practice point for clinicians.9.2.Surveillance colonoscopy programmes9.2.1.Screening and surveillanceSince dysplastic changes in colonic mucosa are associated with an increased risk of CRC in UC,surveillance colonoscopy programmes have been developed with the aim of reducing morbidity and mortality due to CRC,while avoiding unnecessary prophylactic colectomy.Surveillance for CRC in patients with UC amounts to more than just performing repeated colonoscopies,but includes reviewing patient symptoms,medication use and laboratory values as well as updating personal and familial medical history.At the onset of these programmes,an initial screening colonoscopy is performed,with the goal of reassessing disease extent and confirming the absence of dysplastic lesions.Thereafter surveillance colonoscopies are regularly performed at defined intervals(below).9.2.2.EffectivenessThe effectiveness of these programmes has been eval-uated in some prospective studies,systematically reviewed by the Cochrane collaboration.66An American consensus conference,held under the auspices of the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America,also reviewed the usefulness of screening and surveillance colonoscopies in2005.80The Cochrane collaboration used death related to CRC as the primary endpoint for the evaluation of surveillance pro-grammes in UC,limiting their analysis to prospective randomised studies that included a control group.The authors were unable to demonstrate a benefit of surveillance programmes for preventing CRC-related death in UC by these strict parameters,but included only two studies in their final analysis.81,82An earlier meta-analysis included a third study yet to be published in full,but concluded that there was an improved5-year survival in patients undergoing surveillance, compared to UC patients outside surveillance programmes.83 Furthermore,in the largest and most meticulous screening programme reported to date,involving600patients,2627 colonoscopies,5932patient-years of follow-up and a caecal intubation rate of98.7%,with no significant complications, 16/30cancers were interval cancers.69Unequivocal evidence for the benefit of these programmes is therefore lacking and the apparent benefit could still be linked to lead-time bias.Patients in surveillance programmes may have an earlier diagnosis of CRC even if CRC is detected independently of surveillance colonoscopy.Diagnosis of CRC in patients outside such programmes may arise from later,ECCO Statement9BRisk is highest in patients with extensive colitis, intermediate in patients with left-sided colitis,and not increased in proctitis[EL2].ECCO Statement9CPatients with early onset of disease(age b20years at onset of disease)and patients with UC-associated primary sclerosing cholangitis(PSC)may have a particularly increased risk[EL2]. Persistent inflammation and family history of CRC may contribute to the risk of CRC in patients with UC[EL3]ECCO Statement9DSurveillance colonoscopy may permit earlier detection of CRC,with a corresponding improved prognosis[EL3,RG B].Unequivocal evidence that surveillance colonoscopy prolongs survival in patients with UC is lacking[EL3,RG B]69ECCO Consensus on UC:Special situations。